Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Communitas

On-line version ISSN 2415-0525

Print version ISSN 1023-0556

Communitas (Bloemfontein. Online) vol.27 Bloemfontein 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150525/comm.v27.8

ARTICLES

https://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150525/comm.v27.8

Queer marginality and planning for brand resonance: a qualitative critique of the South African advertising industry

Khangelani DzibaI; Carla EnslinII; Nceba NdzwayibaIII

IThe Independent Institute of Education: Vega School, Johannesburg, South Africa. Email : Khangelani.dziba@gmail.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6589-8104

IIThe Independent Institute of Education: Vega School, Johannesburg, South Africa Email : censlin@vegaschool.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6874-2690

IIIThe Independent Institute of Education: Vega School, Johannesburg, South Africa Email : nceba.ndzwayiba@gmail.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5688-9035

ABSTRACT

Meaning and purpose in brand advertising has gained prominence in society (Deloitte 2019. Millennial and Generation Z consumers in particular demand brands to have a clear position on social causes they care about. Consequently, the advertising industry is progressively recognising the importance of investing time and resources to gain an in-depth understanding of the prevailing political and sociocultural dynamics that affect targeted consumers in the social environments in which their brands exist. This enables brands to craft strategies that foster a strong cognitive and emotional connection within a diverse consumer base (Keller 2009; Badrinarayanan et al. 2016); and leverage these to craft meaningful advertisements that enhance brand resonance, brand equity, and social change (Enslin 2019; Minar 2016). The aim of this study was to examine the social constructions of gender and queer identity in advertising through the lens of brand communication planners; and to understand how the voices of the queer community are included in the planning and production of advertisements that resonate. Methodologically, a critical qualitative research approach was applied to investigate the experiences of the participants. Data were collected using semi-structured interviews. Queer theory and brand resonance theory were used to analyse and discuss the emerging themes.

Keywords: advertising; brand leadership; brand resonance; marketing communication; brand communication; queer marginality; queer identity; social change

INTRODUCTION

Despite progressive developments and notable progress in the advertising industry, the advertising strategies developed by brand communication planners and creative directors in advertising agencies often fail to address the prevalent problem of marginalisation of queer people (Rocha-Rodrigues 2016; Roderick 2017). When the industry attempts to address gender in advertising, it often misrepresents the full spectrum of the LGBTQQIAP+ community, centring a particular narrative that is often informed by cis-gender and cis-heteropatriarchal understanding of the community (King 2016; Timke & O'Barr 2017). This shortcoming mirrors a broader societal challenge that is well articulated by McEwen (2021). McEwen (2021) posits that despite the work that has been done by liberation and decolonisation movements to transform and dismantle the stronghold of coloniality, there is still more to be done to dismantle the colonial legacy relating to the construction of gender and the normalised cis-hetero-patriarchal gender roles; a view that is shared by other feminists and scholars of gender who seek to dismantle this system (Butler 1998).

Research focused on understanding the social constructions of gender by creative directors and brand communication planners in South Africa's leading advertising agencies indicate that they view such constructions as critical to understanding their influence on the production of gendered advertisements, and whether they help to challenge queer marginality to create a strong resonance with this marginalised social group.

PROBLEM STATEMENT

The approach of South Africa's brand advertising industry towards being more inclusive of queer people is improving. Some of the most contemporary examples that can be referenced from 2021 and 2022 include, but are not limited to, the work done by brands such as LUX, Chicken Licken, Stimorol, and Nando's where members of the community have been represented and, in many ways, have had their stories told. Notwithstanding this progress, South Africa's advertising industry, as a microcosm of society, is involved in the reproduction of cis-heteronormative standards through the non-recognition of queer identity as a continuum in the planning and production of advertisements. Additionally, when the industry produces queer-inclusive advertisements, the advertisements often misappropriate queer liberation activism for the sole purpose of achieving the objectives of the pink economy or pink capitalism.

Pink capitalism is based on the belief that queer people have more disposable income and buying power compared to heterosexual families (D'Emilio 2016). The pink economy is attractive to brands as it contributes an estimated $23 trillion (USD) to the world economy (LGBT Capital 2020). In the scramble for queer consumers, brand communication planners and creative directors tend to produce advertisements that portray queer bodies within the extremes of ultra-femininity and hypermasculinity to consumers (Timke & O'Barr 2017), a perspective that reifies and reinforces the existence of queer bodies through the prism of heteronormative male-female cis-gender binary (King 2016). This misappropriation, misrepresentation, and non-representation of queer people triggered the research interest to study and better understand the processes followed by the advertising industry, as well as the values of practitioners that are involved in the process of planning and producing advertisements that resonate with all. It can be reasoned that such values influence both the process of producing the advertisement, and the outcome.

RESEARCH AIM

The lacuna exists in contextualising the genesis of the advertiser's thinking (social constructions) within their lived professional experiences. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to understand the social construction of gender by South African advertising brand communication planners and creative directors, and how they included queer people in the planning for brand resonance in advertising.

To adequately address the main aim, the following objectives were formulated:

♦ to explore brand communication planners' and creative directors' social construction of gender and queer identity which may also reinforce forms of queer exclusion;

♦ to establish how South African brand communication planners and creative directors include/or exclude queer identities in the planning of brand advertisements to achieve brand resonance; and

♦ to understand the role the advertising industry could play in the emancipation and liberation of queer people through advertisements that resonate with consumers, or identify the challenges that might lead the industry to be resistant to playing an emancipatory role.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND INSIGHTS

According to Asmall (2010), the influence of the apartheid regime was the foundation upon which the South African advertising industry was based when television advertising came into effect in 1978. Television was introduced in South Africa in 1976 and was targeted at white people (Asmall 2010). The main contestation by the then ruling government centred race pollination through advertising, which would give power and rise to the voices of black people who at the time were viewed as inferior to their white counterparts (Asmall 2010). The apartheid regime did not only enforce racial segregation but also normalised heteropatriarchy through criminalisation of same-sex relations; thus making South Africa a white heterosexual state (Judge 2021). According to Judge (ibid.), the shift in how marginalised groups were treated during this era came to an end when the first vote in 1994 for all South Africans (inclusive of those previously maligned) came into effect. The vote would inaugurate a new constitution and dispensation that would not only realise equal racial rights; but further recognise the freedom of the queer community which comprised of anti-discrimination laws on the basis of gender and sexual orientation and the decriminalisation of same-sex relationships and same-sex unions (Judge 2021). An understanding of this historical background illustrates how transformation of any kind requires political will which ultimately has an impact on everything society is able to do. Thus, it can be inferred that this recognition further had an influence on how the advertising industry was designed. Planning towards being more inclusive of marginalised groups was and continues to be a necessity. The alienation of marginalised consumer schemas is essentially what this article sought to examine with respect to the queer community.

This is precisely because of the influence and power the advertising industry has on different segments of consumers; and by extension, society in terms of social roles and images that are acceptable and desirable (Pollay & Mittal 1993; Burns 2003). The opposite of alienation is resonance and is a theoretical lens that this research adopts.

The core of advertising is to market to consumers by appealing to a particular narrative that has relevance to their lived experience, thus influencing their buying behaviour (Mailki 2020). This process in brand advertising is called brand resonance. Brand resonance is a theoretical construct that was founded by leading marketing scholar Kevin Keller (2009) as part of his Customer-Based Brand Equity Model. The model prioritises the customer and ensures that brands follow key steps in advertising to build relationships with their consumers. This relationship allows consumers to be able to connect with brands and their purpose through advertising as a vehicle of their brand communication. This insight highlights how advertising plays a crucial role in society insofar as having meaning and purpose in the minds of consumers, thereby resonating with all consumers (Spence 2009) by educating, challenging, and shifting perceptions on issues like queer marginality in advertising. Brand resonance enables an understanding of how critical it is for brands to establish themselves within the consumer's psyche to establish solid meaning and purpose (Aaker 1996; Keller 2019). Brand resonance also allows consumers to see themselves adequately reflected in the brands they choose to support, allowing brands to achieve brand equity in terms of financial gain and having a relationship with consumers (Keller 2019).

From a queer theory perspective, the literature confirms that the dominant constructions of gender and sexuality are predicated on the teachings of society in terms of the entrenched and accepted sociocultural roles assumed by male and female bodies (Butler 1993). The literature also confirmed that the social framework of gender in society is socially constructed and thus, not a fact of nature or biology (Butler 1990; 1993; 1998). People who do not adhere to the discursive frameworks or societal reference of what is considered legitimate according to the societal standards are, as a result, marginalised (Raja 2019). The queer community, because of this normality of cis gender identity, has been marginalised and illegitimated. The queer theory literature reviewed further illuminated the complexity of gender, and cautioned against the conflation of sex and gender, as these denote different meanings (Ndzwayiba & Steyn 2019). Queer theory adopts a process of debunking the dominant knowledge paradigms of sex, gender, and sexuality and demonstrates that these are products of power that are strategically deployed to maintain a status quo of inequality and compulsory heteronormativity (Rich 1980; Raja 2019).

Although mostly found in the global north, there are empirical studies that had examined queer marginality in advertising by leading scholars as a way of challenging the representation and misrepresentation of the LGBTQQIAP+ community. The reviewed theoretical and empirical literature showed that some in the advertising industry were progressively engaged in the critical work of deconstructing the gender binary using one, or a combination of theory and models. Thus far, scholars in this domain tend largely to focus on deconstructing the representation of gender through the heteronormative binary lens in advertisements. Some authors lament the continued exclusion of minority groups, including the broader spectrum of LGBTQQIAP+ people. Others argue that the evident limited growth in the inclusion of gay men, particularly gay male couples, in advertisements is largely driven by capitalist interest within the confines of the pink pound rather than a genuine intent to engender real social change.

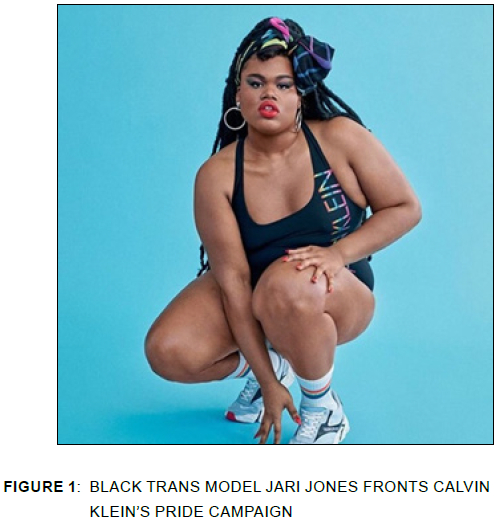

Brand resonance (Keller 2009) is concerned with the extent to which brands can build relationships and connections with consumers, which can ultimately be leveraged to achieve brand equity. This is achieved by ensuring that the four dimensions of Keller's (2009) Brand Equity Model are achieved in terms of loyalty, attachment, community, and engagement. Keller's model (2009) illuminates how the psychology and emotions of consumers matter through representation and that they can see themselves authentically portrayed by brands. Brands like Calvin Klein (Figure 1) and Ralph Lauren (Figure 2) have set the tone globally on how not to exploit the pink economy. Rather, they are examples of what it means to plan for brand resonance with the purpose of engendering meaningful change and what it means to be allies of the LGBTQQIAP+ community at every touchpoint of their brands. This is particularly important in terms of how brands position their relationship with the community.

The brand resonance theory was adopted as a suitable lens to merge with queer theory in this interdisciplinary research to understand the relationship between the advertising industry and the queer community. Not only that, but it was adopted as a lens through which to critically study how gender is understood and interpreted in brand advertisements to achieve brand resonance with a broader spectrum of society, particularly in emerging markets such as the global South and South Africa.

Some of the guiding principles include authenticity and understanding of consumers in terms of what is of value to them with respect to the brands they choose to support (Deloitte 2019). This would then lead to brands being able to communicate effectively with consumers by leveraging secondary associations to land their core reasons of being, also referred to as meaning and purpose by Keller (2009) and Neumeier (2005; 2020). Once this stage has been activated, the four dimensions of brand resonance can be achieved, thereby creating a greater sense of community and engagement that would allow for greater conversations that, in turn, yield not only equity but to also influence how consumers view society (Aaker 1996). Furthermore, having a greater sense of community with consumers also allows brands to be able to tap into contemporary trends as a way of co-creating brand solutions that resonate.

Central to this research, therefore, are these principles and how they can be used to create an environment in advertising that is more inclusive of queer people. The implementation of these key insights would achieve what Minar (2016) advocates in terms of advertising; ceasing merely reflecting society on itself and instead, engendering much needed change for marginalised members of the LGBTQQIAP+ community.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The study adopted a critical qualitative research (CQR) approach to investigate the possible entrenched normative ideas of gender and sexuality in the advertising industry. Critical qualitative research connects social phenomena to broader social and historical events to uncover the ubiquitous structures of power, concealed assumptions, taken-for-granted dogmas, and related tyrannical discourses with the aim of calling for real social change.

Participants in this study comprised of industry brand communication planners and creative directors from leading South African agencies that shape and influence brand advertising approaches. These two groups are central in the planning and production of an advertisement. Shukla (2020) further asserts that the success, reliability, and trustworthiness of a study are all dependent on the right sample selection. For this study, the researchers reviewed the agency winners of the industry awards in the South African advertising industry and targeted the brand planners and creative directors working in these agencies for participation in the research. The researchers systematically reviewed AdFocus industry awards listings. AdFocus is an award platform that is recognised within the industry for honouring the best agencies and practitioners who have produced notable results in terms of strategic thinking and execution, business performance and growth, management, and empowerment (AdFocus 2019). These AdFocus awards also recognise campaigns that affect and improve the bottom line, contribute towards social change, and strengthen the moral fibre of society. From the 2019 AdFocus winners, the 15 top agencies were selected as part of the first round. The researchers then resolved to select the top five within the 15 winning agencies and invited the brand communication planners and senior creative directors working in these agencies to participate in the study.

From a sampling perspective, the study relied on guiding principles of Shukla (2020) and Adams et al. (2014) to select the most suitable population group for the purpose of gaining rich insights from their views and experiences of the phenomenon of inquiry. Thus, a purposive sampling technique was applied (Maxwell 2008). These comprised senior brand communication planners and senior creative directors from five award-winning agencies, from the initial list of 15 who agreed to participate in this inquiry.

The number of participants was guided by data saturation. Thus, the researchers stopped recruiting new participants once the data collected fairly represented the social realities of the studied population group and no new themes emerged (Maxwell 2008).

RESEARCH FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Five themes were constructed from the analysis of data collected. These themes and their subthemes are discussed in the context of each research objective outline in the preceding sections of this article.

RO1: To explore brand communication planners' and creative directors' social construction of gender and queer identity

The social construction of gender and queer identity by brand communication planners and creative directors was, in fact, multi-layered as they understood, in their retort of gender and sexuality, that these were two different constructs. This explanation was in line with the research objective and the insights arising from the reviewed literature. However, a more nuanced finding and theme was constructed in this part of the discussion with the participants, in which it was established that there were positive and negative connotations to gender and queer identity. These sentiments during the researcher's discussion with all participants in all specialties were echoed in terms of the Christian values with which the majority of the participants were raised. These values supported a particular education on the roles and functions to be performed by the male and female bodies (Butler 1993; McEwen 2021); values that ultimately influenced how they approached the planning and production of advertisements and, furthermore, the reactions they had experienced in their profession relating to other forms of expression of gender identity.

Social constructivism, which is the epistemological assumption and paradigm adopted by this study, provides a context on how the very assumption of gender identity being fixed and an innate inheritance of the bodies we are born with, is problematic (Butler 1993) and further results in social constructs of society that seek to maintain a particular social order (Butler 1990).

Although participants were able to learn and unlearning certain societal perceptions defended about gender and sexuality, it was not something that they could influence on their own as brand agency partners, especially if they wanted to include such insights on sex and gender in the brand strategies and creative productions planned for brand resonance. The reason for this is due to the sentiments shared by Butler (1990; 1993) on the maintenance of a particular social order and power dynamics. The initial objective was therefore critical in establishing the context from which brand communication planners and creative directors derived, which influenced their approach to sex and gender in advertising. Understanding this lens would align, or misalign, with the findings presented by contemporary gender scholars. Therefore, it must be noted that there was a clear understanding from the participants of what the sex and gender constructs denoted and how they should be applied.

Theme one refers to the negative and positive connotations of gender and queer identity and, more specifically, subtheme 1.3 regarding some of the participants' self-examination of how they approach gender and sexuality, which is an example of how heightened their awareness is of the fluidity involved with gender and sexuality in contemporary society and the desired need to engender change. However, the negative connotations were not necessarily associated with the participants' own conceptions of gender and queer identity, which were more reflective of current times where gender has been expressed in different forms and facets. In fact, they attempted to bring these constructs and concepts into some of the productions they were tasked with. However, in the instance where they could potentially incorporate gender fluidity and queer inclusive ideas into brand solutions and brand advertisements, it was often rejected by their clients. The rejection of queer inclusivity is because of social constructions that aim to maintain a particular social order around heteronormativity (Raja 2019; McEwen 2021). This insight is linked to theme two, which is discussed in objective two.

RO2: To establish how South African brand communication planners and creative directors include or exclude queer identities in the planning of brand advertisements to achieve brand resonance

What arose in the discussion with the participants revealed that clients determine the topics that can be explored through their briefs to agencies and that they are key role players in influencing the outcome of the process, followed by brand communication planners and creative directors in their production of advertisements. This revelation was not necessarily referring to the team structures of the agencies and the consultants they worked with that were queer identifying. Rather, it was pertaining to whether queer featuring advertisements would ultimately get to be seen in the public domain and in their brands. It is the critical theory realm that exposes the positionality of certain stakeholders and how, in both said and unsaid ways, they perpetuate the maintenance of a particular social order. This cements Butler's (1993) argument on how power and dominance thrive unabated in certain spaces. Understanding the general attitudes in relation to the second objective elicited the key reasons why the participants held the views they did.

Most of the participants indicated that gender and queer identity, in the process of planning and producing advertisements, was largely predicated on the value their clients viewed in terms of being inclusive and diverse in their brands. This was largely pinned to the kind of briefs being issued to agencies that often do nothing to debunk demographics and socio-psychographics. It can therefore be argued that indeed, the meaning of these constructs is often taken for granted. They are in fact approached from a cis-gendered and heteropatriarchal approach, which is alienating of the varying spectrum of marginalised groups such as LGBTQQIAP+ people. As was evidenced and discussed in the literature, sex, gender, and sexuality should not be conflated (Ndzwayiba & Steyn 2019) and, if it is accepted that this argument is true, it becomes evident that how brands currently categorise demographics and socio-psychographics and how brand advertising agencies respond to briefs issued by their clients is problematic and requires re-evaluation. This relates particularly to how, when the industry refers to gender in briefs, it refers to the biological nature of bodies. However, within this classification of sex, there is a disparity, complexity, and exclusion of people who do not necessarily identify with the prescribed binary constructs. Contemporary literature further showed that this essentialist way of approaching segmentation and consumer profiling is alienating, oppressive, and reinforcing of cis-gendered heteropatriarchal binaries.

While the participants agreed that their role should be to educate clients on the environment in which their brands exist, and in terms of the varying identity prisms that need to be represented through the various brand touchpoints to achieve resonance, their influence could only go as far as their clients allowed. The power dynamics between clients and their agencies is evident, which if not used progressively could yield further oppressive reproductions of marginality and exclusion.

Subthemes 2.1 (some participants acknowledge the importance of diversity in internal teams and brands they represent as a way of driving diversity in thinking and approach) and 3.2 (no inclusion of (external) queer identifying parties to examine the resonance of strategies except for team members within agencies who identify as queer) demonstrate how some of the agencies realised the importance of diversity in internal teams and brands they represent as a way of driving diversity in thinking and approach. This realisation answered, in many ways, objective two of this study on how agencies realised an opportunity to be more inclusive of queer identities in their planning process.

Alcoff's (1996) text, The Problem of Speaking for Others, contends a priori of points around how, when others speak for or on behalf of "them", it distorts the meaning and truth of the people being spoken for. These include centring a particular narrative from a particular position that may not necessarily resonate with others or may affect those who are listening and how they interpret what is said, or how the one who is speaking is influenced by their set of experiences that may not be the same as those they are speaking for. She further contends that it does not mean that others should or cannot use their position to advocate for those who may not be able to speak for themselves. Rather, she suggests the need to be more aware of how complex this task is and how it needs to be an assumed collaborative role. This could not be truer for the brand advertising industry, which is positioned in an influential role in society and thus needs to be aware of its responsibility.

Most of the participants narrated that it was rare that they had the opportunity to action what has been documented in contemporary literature, primarily because of the nature of the agencies, which is fast-paced and often lacks the budgets to conduct focus groups to test the resonance of brand advertisements centring queer people. According to the participants, this task was not spoken of, and the responsibility was often left to team members who openly identified as queer, particularly from a strategic planning point of view. Some of the creative director participants did, however, try to seek queer identifying consultants to help them bring queer-centred narratives to life in ways that would resonate. If Alcoff (1996) is understood correctly, being non-inclusive both in agencies and brands is problematic, and perhaps it is something that agencies and brands should start looking into and having clear interventions towards addressing it.

To further respond to objective two, the research needed to explore what processes were followed by agencies in the creation of brand advertisements that resonate. The answer to this question would further elicit to what extent queer people were included in the planning and production of brand advertisements that resonate. The roles described by the participants were in line with those established by the founding fathers of advertising - Bruce Barton in 1923, Roose Reeves in 1950, David Ogilvy in 1955, Theodore Levitt in 1960, and Phillip Rotter in 1967. They understood that the role of advertising was highly functional with clear sales objectives and therefore had to ensure the uptake of the brand product. While this still forms part of the core of advertising and a measure of success for brand communication planners and creative directors, the approach has evolved to include more sociocultural trends around inclusivity and diversity.

Although the focus of the research was on participants whose backgrounds were agencies, the importance of diversity in thinking, organisational culture, and representation in brands was not and should not be understood as a priority that only applies to the advertising agency industry. An equal part of successfully achieving diversity and inclusion of all in society needs to be a matter that corporate brands prioritise as part of their mandate as well. This would ensure that the voices of those who are often marginalised are heard and efforts are made to redress the inequalities. This thinking addresses the second research objective and supports the argument made by Alcoff (1996) that exposes the problem of speaking for others, and Ormsher's (2021) text that investigates how advertisers can work responsibly with trans talent. In other words, how can brands, and by extension agencies, be more inclusive of those that they aim to represent in the planning and production of brand advertisements that resonate?

The last and final section of answering objective two considered whether the matter of gender and queer identity inclusivity was product category specific. This was informed by the literature that revealed that advertising had both functional and emotive approaches that could be applied in the production of advertisements (WARC from Home 2020). The responses of the participants indicated that they needed to understand the brand briefs in the context of these approaches before applying them.

Some of the participants agreed that, while there should not be certain brand categories that would be viewed as being able to opt in or out of being inclusive of queer people in their brands, this was tougher for brands that were more traditionally entrenched and well established. The reason for their inflexibility was rooted in capitalistic priorities that aimed to achieve the business bottom line rather than build a relationship with their consumers and become involved with them. The participants stated that this was influenced by several factors, including those identified in themes one and two, on the perceived unreadiness of consumers to engage with advertisements that do not necessarily reflect a cis-gendered schema. It was also because, from a brand perspective, it was sometimes harder to try something new when something has been perceived as always working for the brand in the past. This hesitance can result in brands being less relevant, appearing to be less innovative, and as a result losing resonance with its involved consumers. However, the participants did reflect that younger brands, some referred to as challenger brands, are more fluid and, as a result, more agile and capable of exploring new territories that are inclusive of queer identities. Furthermore, most of the participants concede that there is an opportunity within established brands to take advantage of what brand leadership is about, and change perspectives that will encourage them to be more inclusive and reflective of society. The ability to do this would place them in a position to influence other larger brands in all categories to do the same.

While the participants reflected on the issue of queer representation that is better suited to certain categories such as the alcohol and beverage, banking, beauty, fashion, fast foods, lifestyle, and technology sectors, it was because the approach to the planning and production of advertisements for these categories was more likely to allow for self-expression as mentioned in subtheme 4.2 (brands that allow for self-expression are more prone to be inclusive than others). This encourages the use of diverse identities who use these products and services. However, participants experienced resistance from some clients who did not always allow these approaches to come to life, as evidenced in theme two (clients determine the topic and brief). Further arising was the authentic use of queer bodies and not merely being performative or ticking boxes, as argued by Ormsher (2021) and Houston (2021). Rather, it should be part of who and what brands are about, thus achieving brand resonance through various touchpoints where queer consumers are able to see themselves reflected in brands equally, have brand experiences, and ultimately build connections with brands (Keller 2009; Enslin 2019; Neumeier 2020).

RO3: To understand the role that the advertising industry could play in the emancipation and liberation of queer people through advertisements that resonate with consumers

It was important to establish this understanding, considering the trajectory international counterparts have taken in brand advertising, to ensure that inclusivity and representation are at the centre of what they do (see Calvin Klein and Ralph Lauren examples in the literature and insight discussion) and in line with what their millennial and Generation Z consumers are calling for from the brands that they choose to support.

South Africa is influenced by global trends and therefore, if the advancement of marginalised groups is a project that has taken place globally, it should be championed in the same manner as all other social causes around race and class are championed through brands. This is in line with what Deloitte (2019) demonstrates in a market study that shows that meaningful brands are those with the intention of resonating with their target market. These brands bring meaning and matter to today's purpose-driven consumer who wants to derive value from brands that influence social change in society.

The Meaningful Brands Index for 2021 also revealed two significant statistics that informed the third objective and should perhaps require advertisers and brand managers to strongly consider moving forward. It relates to brand resonance. These found that 73% of the respondents wanted brands that will make a difference for the betterment of society and the planet. These respondents would not care if 75% of the brands disappeared overnight. This revelation further entrenched the importance of brand communication building that would ultimately ensure meaningful and harmonious strategies with operational analytics and design to ensure the success and survival of brands.

The relevance of this insight is that it ignites brand resonance thinking, which essentially centres the relationships brands build with consumers and ultimately society through causes that they care about as a way of creating meaning in their lives. The meaning created achieves the objective of being purposeful in society and influencing the shift of perceptions that could ultimately lead to social change. As evidenced by the studies reviewed, today's value for brands will come from Goodvertising; brand advertising that is change-driven in nature (Minar 2016). When executed well, it has the potential for leading brands to gain support from a wider spectrum of consumers while making a positive impact on society.

Significantly, most of the participants interviewed affirmed that advertising plays an influential role in society because it can shape culture and subculture trends in the lives of consumers. It does this, according to the participants, by reinforcing what is seen in society as acceptable, and this forms part of brand narratives and ultimately, brand resonance. It is because of this potential influence that advertising should intentionally advance issues related to the rise of social consciousness, which is what millennials and Generation X are increasingly requiring from brands. It aligns with theme three and subthemes 5.1 (promote tolerance and patience in society), 5.2 (educate society on trends and acceptable behaviours), and 5.3 (shaping and changing narratives in society (creating acceptable cultures)). This was specifically stated by one participant as follows:

We need to remember that advertising creates culture. So, at the end of the day, we have a massive responsibility, I think, as advertisers...because what we say becomes popular culture.

According to BizTrends (2021), consumers are now at the forefront of setting the agenda for brands in terms of the kind of content they want to see coming from them. Therefore, within its position of influence, advertising can shift the narrative on issues relating to marginalised groups and ensure representation across all levels of society, including those relating to gender and queer identity. Additionally, some of the participants indicated that the advocation for representation of cis-gender identifying consumers, i.e., representation of women and black lives, has reached a stage where it happens organically.

Here's the crazy thing. We've done that with the heteronormative society. We understand them in all their complexities because that's all we've ever known. But the minute you start to talk about someone who's different, then it's like, oh, my God, when will it ever stop? Will I ever get it? No. I say for as long as we are willing to share information, let's be open.

It is for this reason that the participants affirm that there could be no better time to start considering the subject matter of queer representation and further action championing issues relating to queer communities in a more profound way. To ensure that this level of inclusion and representation is authentically achieved, the participants acknowledged that it needs to be a collaborative effort with those they aim to speak to through their brands. This would achieve what Alcoff (1996), Houston (2021), and Ormsher (2021) call for: working together with marginalised voices and telling their stories in an authentic and meaningful way. This approach would also have resonance with the broader community and educate them about a community that has often been underrepresented in its entirety. It would further position brands as working together with those who have not always been given the opportunity to influence and shape advertising.

Subtheme 5.4 (being representative and diverse in thinking and hiring teams) demonstrated how internally, the participants further suggested that they could improve the agency culture to allow for more diversity and inclusion in the types of human resources employed, and work environments that encourage different ways of approaching brand challenges. This, they stated, would need to be an assignment for those in leadership positions and who can influence decisions made. Ultimately, participants agreed that brand advertising could play a more meaningful role in society and exploit its assets to empower those who may not have the platform. This sentiment is further echoed in global research: 73% of consumers believe brands must act now). However, to achieve success, both agencies and the clients they lead, would need to take on this task with the intent of changing, shaping, and influencing society as a way of achieving brand resonance. This would allow consumers to see themselves and the things that matter to them reflected in the brands they are loyal to (Aaker 1996; Keller 2009).

To this end, the final theme (the societal responsibility of advertising) aligns with the third objective of this study, which was to determine to what extent the advertising industry could play an emancipatory and liberating role for queer people through brand advertisements that resonate with consumers. It was highlighted by the narrated experiences of the participants; that to achieve emancipation, this needed to be an endeavour undertaken internally and externally by the organisations. This was precisely because the advertising industry is influential and shapes subcultures in both spoken and unspoken ways. It was also made clear that, if the agenda of emancipation is made a priority across the different touchpoints of advertising, the desired change and transformation could be achieved, and there could be a greater level of brand resonance. Furthermore, the change and transformation project for the betterment of the queer community needs to be a priority for all decision makers in the value chain, and not just for some of them.

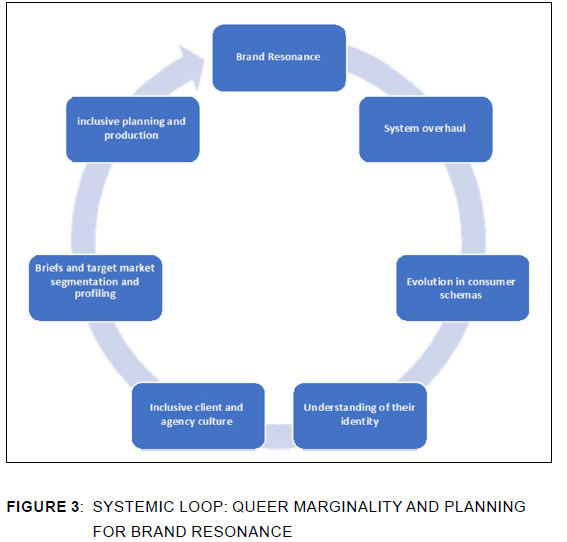

THE SYSTEMIC LOOP TO QUEER MARGINALITY AND PLANNING FOR BRAND RESONANCE

After engaging in a discussion with participants and select brand managers on some of the themes emerging from the inquiry, the systemic loop below aims to highlight the structural challenges within the industry that could be explored as a tool to begin peeling the layers involved in achieving brand resonance.

The first step refers to a system overhaul, which was informed by the first theme and its subthemes (positive and negative connotations to gender and queer identity) and the first two additional insights (new ways of doing and institutional fears). It appears that the challenges faced by the industry as it relates to the aim and objectives of this research wereinterlinked and complex. From a Urand perspective, the transformation project would involve brand marketing executives and decision makers in leadership positions that clearly define their purpose and who they represent. This would need to be led by insights into who their target profile is and understanding the things they care about as o way of inteorating them icto their brand communication strategies to achieve brand resonance (Kantar 2019). From an agency perspective, it would also involvn ensuring that the teams working on the briefs of their clients are diverse, inclusive and reflective of the society in which they exist. In addition, they would need to challenge the fears of their clients related to exploring new ways of approaching brand communication to achieve brand resonance with their current and new consumers. They would be able to achieve this by keeping abreast of the latest contemporary research studies produced by contemporary scholars and practitioners. These scholars are armed with insights that they could use to lead their clients to new and unexplored terrains.

The second and third steps relate to consumer schema and understanding of their nuanced identities and are linked to theme two (clients determine the topic and brief) and insight three (debunking key constructs in briefs). These two insights reveal that appreciation for the developments occurs not only in industry, but in the consumer schema in terms of their more nuanced identities. Evidenced by research conducted by various institutions (Deloitte 2019; Kantar 2019), such would allow brands and industry to evolve and create brand communication strategies and advertisements that are more diverse and inclusive of marginalised groups and identities. The rewards of doing this would ensure brands achieve resonance and build meaningful relationships with their consumers that would ultimately breed loyalty and affinity to brands.

Fourthly, inclusive client and agency culture, which is linked to theme five of the primary research, would allow both stakeholders to achieve a lot more in terms of working closely together with more diverse people in terms of background and identity. It would lead to the fifth step where practitioners would be able to interrogate briefs with more vigour, thus allowing industry to see segmentation in a less egalitarian manner and create relevant strategies and brand advertisement productions that resonate. These two steps are interrelated with themes three (the development of advertisements and participants' role assignments) and four (functional versus emotive briefs) and additional insight five (the need for authenticity) from the discussion with marketing managers.

The sixth step relates to inclusive planning and production, which highlights the need to further collaborate with queer people to ensure relevant strategies and advertisement production, which would lead to the seventh and final stage of brand resonance where a relationship and emotional connection are finally established and built with consumers (Keller 2009). These link back to theme five (the societal responsibility of advertising) and additionally, insight five (capitalism vs consumer responsibility and purpose).

CONCLUSIONS

This study engaged a particular segment of the advertising industry with the intention of initiating dialogue on the issue of marginality, queer identity, and resonance. The findings are limited to the group of participants engaged with and are by no means generalisable. What was deducted is that queer people are marginalised because their lived experiences and the narratives of external queer voices are not utilised in the production of advertisements. When needed, this task is usually fulfilled -to a limited extent - by internally employed queer-identifying staff. As architects of culture, brand advertisers and their clients have a responsibility to be inclusive and representative of marginalised segments of society, such as the queer community. The systemic loop to queer marginality and planning for brand resonance contributes strategic steps to achieve broader brand resonance and equity with agencies and their brand partners. It would create and action authentic queer community reflection in their brand productions and more resonant and meaningful brands. This could help raise awareness and contribute towards building a more just and equitable society.

REFERENCES

Aaker, D.A. 1996. Building strong brands. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

Adams, J., Khan, H. & Raeside, R. 2014. Research methods for graduate business and social science students. New Delhi: Sage. [ Links ]

AdFocus. 2019. Shortlisted finalists for the 2019 Financial Mail AdFocus Awards announced. [Online]. Available at: https://www.businesslive.co.za/redzone/news-insights/2019-10-01-shortlisted-flnalists-for-the-2019-flnancial-mail-adfocus-awards-announced/ [Accessed on 12 November 2019]. [ Links ]

Alcoff, L. 1996. The problem of speaking for others. Cultural Critique 20(Winter 1991-1992): 5-32. [Online]. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1354221 [Accessed on 3 February 2021]. [ Links ]

Asmall, S. 2010. Television advertising as a means of promoting an intercultural and interracial South Africa and nation building. A case study of the International Marketing Council's 'alive with possibility' campaign. [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/3ijx1ZV [Accessed on 27 June 2021]. [ Links ]

Badrinarayanan, V., Suh, T. & Kim, K. 2016. Brand resonance in the franchising relationships: A franchisee-based perspective. [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/3XBoamm [Accessed on 11 October 2021]. [ Links ]

Burns, K.S. 2003. Attitude toward the online advertising format: A re-examination of the attitude toward the ad model in an online advertising context. Unpublished doctoral thesis. University of Florida. Gainesville, Florida, United States of America. [ Links ]

Butler, J. 1990. Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Butler, J. 1993. Bodies that matter. On the discursive limits of sex. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Butler, J. 1998. Performative acts and gender constitution: An essay in phenomenology and feminist theory. Theatre Journal 40(4): 519-531. https://doi.org/10.2307/3207893 [ Links ]

Deloitte. 2019. Purpose is everything: How brands that authentically lead with purpose are changing the nature of business today. [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/2MkVTy7 [Accessed on 03 August 2021]. [ Links ]

D'Emilio, J. 2016. Capitalism and gay identity. [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/3XPlwKb [Accessed on 17 April 2019]. [ Links ]

Enslin, C. 2019. Brands & branding: Transformations & emergence of brand ecosystems. [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/3OHSlob [Accessed on 11 October 2021]. [ Links ]

Houston, A. 2021. Going beyond the rainbow: Can brands be true allies to the LGBT+ community online? [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/3gAzWwV [Accessed on 23 May 2021]. [ Links ]

Judge, M. 2021. Queer at 25: A critical perspective on queerness, politics and futures. Journal of Asian and African Studies 56(1): 120-134. DOI:10.1177/0021909620946855 [ Links ]

Kantar Consulting. 2019. Purpose 2020. Igniting purpose-led growth. [Online]. Available at: https://consulting.kantar.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Purpose-2020-PDF-Presentation.pdf [Accessed on 03 August 2020]. [ Links ]

Keller, K.L. 2009. Building strong brands in a modern marketing communications environment. Journal of Marketing Communications 15(2/3): 139-155. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527260902757530 [ Links ]

King, J. 2016. The violence of heteronormative language towards the queer community. [Online]. Available at: https://pubs.lib.umn.edu/index.php/aisthesis/article/download/781/788 [Accessed on 12 October 2021]. [ Links ]

LGBT Capital. 2016. Quantifying LGBT-GDP, LGBT-Wealth and LGBT Travel. [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/3ih0Udg [Accessed on 12 June 2019]. [ Links ]

Mailki, S. 2020. What is brand advertising, how it is unique & why should you use it? [Online]. Available at: https://instapage.com/blog/brand-advertising-examples [Accessed on 24 May 2020]. [ Links ]

Marketing the Rainbow. 2020. Case study: Ralph Lauren. [Online]. Available at: https://marketingtherainbow.info/case%20studies/fashion/ralph-lauren [Accessed on 01 July 2021]. [ Links ]

Maxwell, J.A. 2008. Chapter 7: Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/3VxSLQc [Accessed on 13 June 2019]. [ Links ]

McEwen, H. 2021. Africa today. Politics and Decolonization in Africa 67(4): 30-49. https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.67.4.03 [ Links ]

Minar, P. 2016. Goodvertising as a paradigmatic change in contemporary advertising and corporate strategy. Communication Today 7(2): 4-17. [ Links ]

Ndzwayiba, N. & Steyn, M. 2019. The deadly elasticity of heteronormative assumptions in South African organisations. International Journal of Social Economics 46 (3): 393-409. https://doi.org/101108/IJSE-11-2017-0552 [ Links ]

Neumeier, M. 2005. The brand gap. United States of America. AIGA. [ Links ]

Neumeier, M. 2020. Behind the brand - Minding the brand gap and beyond. [Online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ApRrkjpReQU [Accessed on 14 July 2020]. [ Links ]

Ormsher, E. 2021. You can't capitalize on us: why advertisers must work responsibly with trans talent. [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/3GNWogH [Accessed on 26 June 2021]. [ Links ]

Pollay, R.W. & Mittal, B. 1993. Here's the beef: Factors, determinants and segments in consumer criticism of advertising. Journal of Marketing 57(3): 99-114. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299305700307 [ Links ]

Raja, M. 2019. Post-colonial concepts: Marginalization and marginality. [Online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EB0SuccHcY0 [Accessed on 27 June 2022]. [ Links ]

Rich, A. 1980. Compulsory heterosexuality and lesbian existence. Signs 5(4): 631-660. https://doi.org/10.1086/493756 [ Links ]

Rocha-Rodrigues, F. 2016. Deconstruction of the gender binary in advertising: an interpretive analysis and discussion. Unpublished Master's dissertation. Durham University. United Kingdom. [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/3XEdJ1C [Accessed on 23 June 2022]. [ Links ]

Roderick, L. 2017. Why are advertisers still failing to represent gay women? [Online]. Available at: https://www.marketingweek.com/lesbians-advertising/ [Accessed on 13 June 2019]. [ Links ]

Shukla, S. 2020. Concept of population and sample. [Online]. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346426707_CONCEPT_OF_POPULATION_AND_SAMPLE [Accessed on 27 June 2022]. [ Links ]

Spence, R. 2009. Last brands left standing. Brandweek 50(6): 2. [ Links ]

Timke, E. & O'Barr, W.M. 2017. Representations of masculinity and femininity in advertising. [Online]. Available at: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/648423 [Accessed on 19 June 2019]. [ Links ]

WARC from Home. 2020. Advertisers should use both functional and emotional appeals. [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/3u6prnY [Accessed on 27 June 2022]. [ Links ]

Date submitted: 6 August 2022

Date accepted: 28 September 2022

Date published: 8 December 2022