Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Communitas

versión On-line ISSN 2415-0525

versión impresa ISSN 1023-0556

Communitas (Bloemfontein. Online) vol.27 Bloemfontein 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150525/Comm.v27.1

ARTICLES

Achieving sustainable corporate social responsibility outcomes: a multiple case study in the South African mining industry

Muriel Serfontein-JordaanI; Sixolile DlungwaneII

IDepartment of Business Management, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. Email: muriel.serfontein@up.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1481-1624

IIDepartment of Business Management, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa Email : sixoliledlungwane@yahoo.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0098-3137

ABSTRACT

Mining companies are responding to increasing pressure to conduct their operations responsibly by implementing corporate social responsibility (CSR) projects in their host communities. However, it has been argued that few of these projects result in sustainable outcomes. Stakeholder engagement should be inclusive to ensure CSR project sustainability. The purpose of this multiple-case study was to explore stakeholder engagement in achieving sustainable CSR outcomes in the South African mining industry. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews with community development specialists from three South African mining companies. It was found that mining companies implement CSR projects intending to achieve economic, social and environmental sustainability within their host communities. Stakeholders are actively engaged in project planning as their involvement in decision-making is critical for sustainable projects through obtaining stakeholder buy-in, collaboration and involvement. The study recommends that management balances diverse stakeholder expectations and educate stakeholders on corporate mining issues. Theoretically the study adds to the understanding of stakeholder engagement for sustainable CSR outcomes in the South African mining industry.

Keywords: strategic communication, corporate communication, corporate social responsibility, stakeholder engagement, sustainability, mining industry, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

South African mining communities are considered unique because they are primarily rural and secluded, have high illiteracy levels, and depend on mines for their source of revenue (Marais et al. 2020: 2). These communities also experience poor socio-economic circumstances (Memela 2020: 4). In addition, the nature of mining is temporary as it relies on the availability of mineral resources (Cronje & Chenga 2009: 413). Therefore, these communities need sustainable economic activities to support them when the mine ceases its operations (Hooge 2009: 32).

The pressure is increasing for mining companies to be more responsible in their conduct towards the host communities where they operate (Frederiksen 2018: 496). This implies that the mine's principal business activities should attempt to equally balance production, profitability and corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Agudelo et al. 2020: 14).

CSR is defined as the set of commitments businesses make to their stakeholders to address environmental, social and economic issues in their communities (Khanifar et al. 2012: 586). There is a call for businesses to take responsibility for the impact their operations have on the environment and societies and include this in the agenda during stakeholder engagements (Selmier & Newenham-Kahindi 2021: 4; Marrewijk & Were 2002: 107). CSR is especially valuable to a country such as South Africa where the government cannot solely address society's diverse needs (Hooge 2009: 30). CSR is gaining momentum in the daily operations of businesses in several sectors, the mining industry being no exception (Jenkins 2005: 537-538).

Jenkins and Obara (2008: 2) emphasise that for businesses to survive, generate revenue and grow, they must be mindful of stakeholder expectations and safeguard the sustainability of the environment. Bearing this in mind, corporations must find a balance between generating a profit and demonstrating accountability for their activities to contribute positively to the survival of society (Marinina 2019: 5).

Frynas (2005: 581-582) investigated the effectiveness of CSR projects within the mining industry. Although mining companies are rebranding themselves as responsible businesses, there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate how the rebranding solves sustainability issues in the community and if community development activities enable a more sustainable community (Jenkins & Obara 2008: 1). The industry has made substantial efforts to emphasise its commitment towards addressing communities' needs and safeguarding the environment. However, insufficient research exists to confirm the sustainability of CSR projects implemented by mining companies (Frynas 2005: 581-584).

Previous studies investigated several focus areas of CSR; for example, the connection between sustainable development and CSR (Moon 2007; Whellams 2007), stakeholder management and CSR (Cheng & Ahmad 2010), integrating CSR into business strategy (Evans & Sawyer 2010), CSR partnerships in the South African mining sector (Hamann 2004), and stakeholder perceptions on CSR in the mining industry (Jenkins & Obara 2008). However, most research investigated CSR in developed countries, where societies are efficient and effective (Arli & Lasmono 2010). Concentration on CSR has gained increasing acceptance in the literature (Friedman & Miles 2001: 538), resolving that companies must assimilate the values of sustainability into their corporate strategies (Ofori 2010). This aspect raises questions regarding the sustainability of CSR initiatives achieved by mining companies.

This study aimed to investigate the types of CSR projects implemented by South African mining companies and the sustainability levels of these projects, together with the role of stakeholder engagement in achieving sustainable CSR outcomes.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Stakeholder theory, legitimacy theory and the TBL model are interconnected, as organisations must balance generating a profit and fulfilling social responsibility by incorporating community development practices into their business activities. This involves fulfilling their philanthropic, ethical, legal and economic responsibilities (legitimacy theory) by pursuing sustainable economic, social and environmental outcomes (TBL model), while considering all stakeholder groups affected by the organisation and its decision-making process (stakeholder theory). All the elements in the theoretical framework, thus, need to be implemented simultaneously to achieve maximum sustainable CSR outcomes (Alhaddi 2015: 6-10).

Corporate social responsibility

As a point of departure, the study employed the World Business Council for Sustainable Development's definition of CSR as "the continuing commitment by business to behave ethically and contribute to economic development while improving the quality of life of the workforce and their families as well as the local community and society at large" (Watts & Holme 1999). The rationale behind using an older definition is that the researchers are of the opinion that it best depicts CSR in the mining industry, namely to improve local communities' quality of life and promote socio-economic development. Furthermore, this definition acknowledges that businesses contribute significantly to the well-being of stakeholders through CSR initiatives.

Corporate social responsibility in mining

CSR in the mining industry is not a novelty. Around the mid-1990s the mining industry globally came under pressure as to how it interacts with and responds to local host communities; this pressure was exacerbated by several disasters tarnishing the reputation of the industry (Van der Watt & Marais 2021: 2). As a result, mining companies and governments increasingly "started introducing several interwoven approaches to improve relationships between mining companies, local government, and communities". These included CSR and the notion of a social licence to operate (Kemp & Owen 2013; Bice 2014).

Hamann (2003: 237) states that CSR in the mining industry refers to projects and initiatives that the mining company embarks on to attain social, environmental and economic sustainability. Mining companies accept a shared responsibility to fulfil some of the community's economic relief expectations (Bongwe 2017: 15). Local communities are often considered the primary stakeholder for mining companies since mines operate within or near to these communities, and their activities influence the communities or are influenced by the communities (Gibson 2000). Bearing in mind the aforementioned, it is understandable that local communities are increasingly applying pressure on mining companies to act more responsibly. As a result, mining companies have realised the importance of obtaining community agreement and support before implementing any project (Danielson 2006).

In 2002, the Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development Project (MMSD 2002) introduced collaborative planning. It suggested a "relationship of collaboration, trust, and respect between the community, the company, and the government to ensure that adverse effects are avoided or mitigated and the benefits of mineral development shared with communities" (Van der Watt & Marais 2021). Hence, collaboration between the companies in the mining industry, the local governments, and the host communities is essential to achieving these goals.

In the South African mining industry, the vehicle employed to ensure the fair distribution of all benefits associated with mining is the Social and Labour Plan (SLP). The Mineral and Petroleum Resource Development Act of 2002 states that a mining company can only obtain a mining license if the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMR) approves its SLP (Van der Watt & Marais 2021: 2). Aligning of the SLP of a mining company with the Integrated Development Plan (IDP) of the local municipality is a precondition for approval; as a result collaboration between mining companies and local governments has become mandatory (DCGTA 2009; Van der Watt & Marais 2021). The IDP provides a developmental framework to co-ordinate the work of the local government and other industries within the community in a coherent strategy to improve the quality of life for all people living in an area (Arenas et al. 2009; DCGTA 2009).

In addition to the aforementioned mandatory nature of CSR in the mining industry, Walker and Howard (2002) suggest the following reasons for the significance of CSR initiatives to mining organisations, namely 1) the public opinion on mining organisations is often poor, 2) the mining industry experiences constant legal pressure from a global and local level, and 3) mining companies need to maintain a social licence to operate - this specifically has always been a challenge for mining companies, as communities often retaliate against the expansion of mining activities because of the lack of community engagement on pertinent community concerns.

Corporate social responsibility and stakeholder engagement

Greenwood (2007: 315) defines stakeholder engagement as several practices initiated by an organisation to enable the constructive involvement of stakeholders in the organisation's activities. Stakeholder involvement is essential as it promotes robust participation in CSR initiatives and assists stakeholders in expressing their perceptions and expectations (El-Gohary et al. 2006: 596). Ihugba (2012) observed the stakeholder engagement approach to, justification for, and consequences of managing CSR in the Nigerian mining industry. The study established that inconsistent stakeholder engagement reduces the sustainability of CSR initiatives. In order to prevent this, Ihugba (2012) suggested that a framework for stakeholder engagement is required to promote informed involvement of primary stakeholders to facilitate sustainable CSR practices. Ideally, such a framework should facilitate balanced and knowledgeable stakeholder involvement and progressive CSR initiatives. Constructive engagement with communities is required to enhance sustainability aspects as this facilitates mutual understanding, common goals and objectives (Hamann 2003: 240).

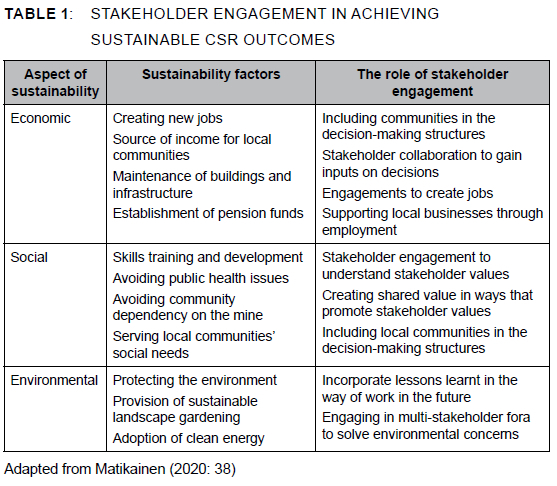

To achieve sustainable CSR outcomes, mining companies should address all aspects of sustainability (economic, social and environmental) in their engagements (Matikainen 2020). Table 1 below summarises the role of stakeholder engagement in achieving sustainable CSR outcomes in the mining industry according to the three sustainability factors. Table 1 guided the researchers in assessing if, and how, the mining companies under investigation use any of the stakeholder engagement tactics, and how these influence the sustainability of CSR outcomes.

SUSTAINABILITY

Sustainability in corporate social responsibility

Sustainability is defined as securing intergenerational equity by focusing on environmental, economic and social issues and balancing these over the short-and long-term (Bansal & DesJardine 2014: 70). Economic sustainability is the level of progression of the standard of living in a community. In contrast, environmental sustainability addresses the preservation of the environment. Social sustainability addresses equal access to resources and opportunities in society (Bansal 2005: 200). An organisation as well as its initiative cannot be sustainable on its own; therefore, it is crucial that stakeholders be included and engaged accordingly (Schaltegger & Burritt 2018: 241).

Mining companies are no exception and cannot achieve elevated levels of sustainable CSR outcomes alone. Partnering and engaging with primary stakeholders, such as government and local communities, help achieve progressive socio-economic and environmental improvements. In addition, they provide valuable inputs to guide decision-making (Hilson & Murck 2000: 230). Forming partnerships with local government and communities is therefore crucial for stakeholder collaboration (Rodrigues & Mendes 2018: 89). Mining companies must acknowledge and address their CSR challenges truthfully because of the growing global expectations placed on the industry. Co-creating CSR approaches and solutions with local communities and continuously engaging them helps sustain trusting relationships (Hamann 2004: 280).

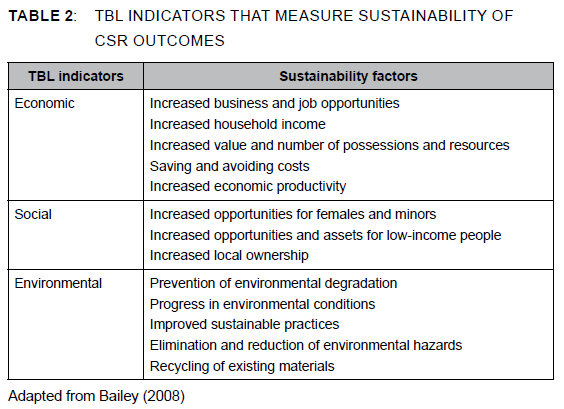

It is necessary to measure progress towards sustainable CSR initiatives. The TBL model, which forms part of the theoretical framework of this study, provides a possible framework for mining companies to measure the levels of sustainability of their CSR projects (Alhaddi 2015: 9). Table 2 below shows the TBL indicators measuring the levels of sustainable CSR project outcomes. The study employed these to assess the levels of sustainability of the CSR outcomes in the observed mining companies.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

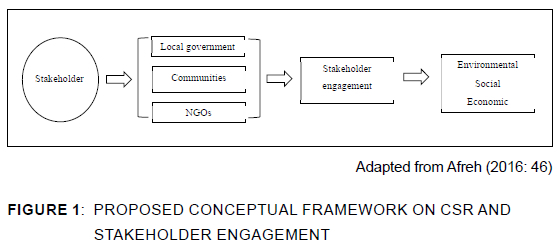

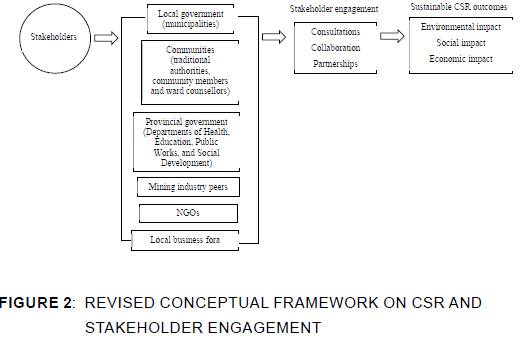

Figure 1 is the initial conceptual framework of the study, as proposed by the researchers, based on the theoretical framework and the literature reviewed. Mining companies must implement effective stakeholder engagement to achieve sustainable CSR projects. Stakeholder engagement builds trusting relationships and tailors CSR projects according to the stakeholders' needs (Afreh 2016: 45). Sustainable CSR outcomes are therefore achieved by addressing the community's needs through primary stakeholder consultations.

METHODOLOGY

The study was conducted according to a multiple-case study research design, considering that the purpose of the research design is to develop a realistic multiple-bounded system by collecting comprehensive data using various information sources (Creswell 2013). The cases were selected to predict comparable or conflicting findings based on the theory, in order to investigate how stakeholder engagement affects sustainable CSR outcomes in the South African mining industry. The study used primary data collected through semi-structured interviews with various participants. The integrated reports for each of the cases were thoroughly analysed, which informed the development of the discussion guide. The research design enabled the researcher to replicate the findings across subjects.

The unit of analysis for this study was mining companies operating in South Africa and implementing CSR initiatives in their host communities. Homogenous sampling was employed by selecting companies with similar characteristics (Creswell 2012: 518). Similarly, homogenous sampling was employed to select the study participants. The participants had to have the following mutual characteristics: 1) participants had to be a community development specialist, or in a similar role, in a South African mining company; 2) participants had to have at least one year's professional experience in this role; and 3) participants' areas of responsibility had to encompass stakeholder engagement for the implementation of CSR projects.

The data was collected through semi-structured interviews as this allowed the researcher to obtain detailed descriptions of the participants' perspectives. The literature review and a thorough review of integrated reports of the unit of analysis organisation - which detailed CSR activities - guided the formulation of the discussion guide. The data collected was analysed using thematic analysis to identify and organise patterns, and thereafter develop themes and sub-themes.

FINDINGS

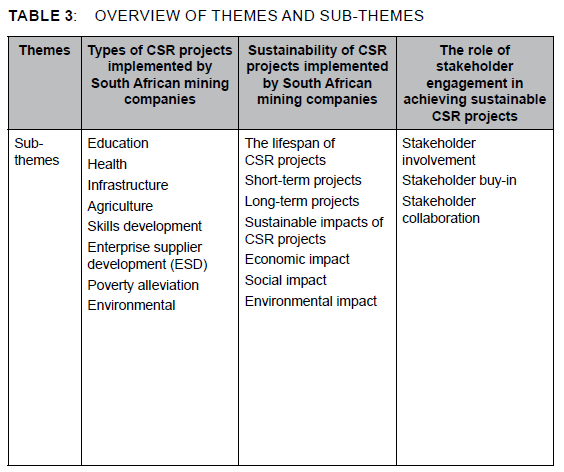

The findings are reported per the three main themes, as indicated in Table 3 below, each with several sub-themes.

Theme 1: Types of CSR projects implemented by South African mining companies

Education

Mining companies prioritise improving education infrastructure and services in their host communities. Education projects can be either short- or long-term. The rationale for short-term projects is to satisfy needs arising at a particular time. These initiatives take the form of donations of items, such as school uniforms, spectacles, laptops, textbooks, and stationery. Long-term initiatives attempt to address education infrastructure challenges and support the teaching and learning process to ensure an environment conducive to learning. Education infrastructure projects include building new classrooms, libraries, ablution facilities and science laboratories, as well as refurbishing old or damaged classrooms.

Additionally, mining companies aim to address the poor pass rate in mathematics, physical science and technical subjects. They develop programmes to aid learners with extra classes to improve their marks.

Lastly, to improve employment potential in the community, mining companies offer the topperforming students bursaries, scholarships and learnerships to further their tertiary education in mining disciplines with the opportunity of being employed at the mine upon the successful completion of their studies.

Health

Health support is an important CSR focus area for mining companies as they intend to improve the poor standard of health services in the community. These projects include building and refurbishing clinics and hospitals, training health personnel, donating ambulances, and hosting awareness programmes for HIV/Aids and cancer. Since the outbreak of Covid-19, mining companies have partnered with the Department of Health and NGOs to assist local clinics and hospitals with essential items such as PPE and testing equipment to help alleviate the pressure on the health system. Mining companies erected Covid-19 testing centres and vaccination sites for their employees and local communities.

In this area, they didn't have a clinic. So, they had to travel 40 km to get to a clinic, and because it's a rural area, there [are] no taxis, so they have to hike three times to get there. So, we then built a clinic bringing the health services to the community. (Participant 12)

Infrastructure

Community infrastructure projects are a significant focus for mining companies. Local municipalities have limited resources and cannot provide essential services to communities. Lack of proper road infrastructure, housing, water, electricity and recreation facilities are among the challenges encountered by communities. Moreover, the excessively high cost of data and lack of internet connectivity in rural areas cause societies to be excluded from the global village. Mining companies understand their role in responding to community infrastructure challenges and therefore implement six main infrastructure projects: road, water and sanitation, electricity, housing, recreational facilities and telecommunications infrastructure.

Road infrastructure projects aim to repair poor road conditions, and mining companies construct tar roads within communities to allow easy and safe access in and out of the community.

Most communities lack access to electricity, clean water, and sanitation. As a result, mining companies partner with local municipalities to implement infrastructure projects to remedy this challenge. These projects include installing electricity in households, building and refurbishing water reservoirs and boreholes for underground water extraction, and upgrading landfill sites for waste removal.

We implemented the electricity project [where] we assisted more than 600 households with electricity. We also have a problem [with] water installation in our local community ... because at this moment, they are drinking water from streams ... [So], we are implementing water infrastructure projects, and as a result, they will have access to clean water. (Participant 5)

Housing conditions in some communities are deteriorating, and as a result, mining companies construct houses for these communities.

Furthermore, the lack of recreational facilities in the communities is a significant driver of crime, alcoholism and drug abuse among the youth. As a result, mining companies have built and renovated various recreational community centres.

Another emerging issue in mining communities is the lack of telecommunications infrastructure for internet connectivity. As a result, mining companies install Wi-Fi hotspots in communities to enable internet access to allow the community to submit job applications, do schoolwork, and have general internet access.

Agriculture

Mining companies have identified agricultural development as an opportunity for local communities to improve food security, alleviate poverty, and help create employment opportunities. As a result, they assist farmers within the community with skills training and funding to sustain and grow their livestock and crop farming businesses.

Some of the participants expressed their challenges of implementing sustainable agriculture projects attributable to the poor soil quality due to mining activities.

We do have agricultural programmes, but I'll be honest [in] saying that they haven't been successful... [The] mining activity directly impacts on the environment, so it makes it difficult for your crops to grow... [In] areas where we see that agriculture is a viable option, then we do try to assist with that, but in a lot of areas we have seen it's difficult to, you know, create agricultural programmes on a more massive scale. (Participant 9)

Skills development

Mining companies implement various portable skills training programmes to address the challenge of unemployment in communities. For example, unemployed community members are invited to attend training in computer literacy, hospitality, and construction. Upon completing the training, some members are employed by the mine, whereas others use their acquired skills in other industries to become financially stable. Additionally, mining companies aim to diversify their skills training to ensure that the community does not solely rely on the mine for employment.

Enterprise supplier development

Mining companies' ESD programmes aim to generate an income for host communities. These programmes encourage entrepreneurship and provide training, mentoring and funding for small businesses. Community members are encouraged to register businesses that supply goods and services to the mine and other institutions. Beneficiaries also learn how to operate and market their businesses. Through entrepreneurial development, mining companies implement preferential local procurement of goods and services, which benefit local communities' businesses, according to one participant.

We look at implementing initiatives that can assist our local [small, medium and micro enterprises] and see how we can develop a project that can allow them to grow from where they currently are ... so that they can supply at a larger scale, whether it be to the mine or other industries not only limited to mining. (Participant 4)

Poverty alleviation

Mining companies implement ad hoc initiatives to help alleviate poverty in communities. These include donating food, blankets, clothes and sanitary towels. This was useful during the Covid-19 pandemic, as several households had lost their income and were in distress.

Environmental

Mining companies implement environmental CSR projects aimed at reducing any adverse effects on the environment from mining operations, as well as to create employment. These initiatives include waste management, recycling and awareness programmes to educate communities on responsible ways to take care of the environment, which will benefit future generations.

We did a one-year project which was labour intensive, because we created employment for 30 people to pick up rubble from all over the area to get it to a dumping site where it was then disposed ... [We] also linked it to the local schools where they were also collecting rubble, and they were sorting and recycling it as well. (Participant 7)

These findings confirm the findings of Afreh (2016) and Bongwe (2017) regarding the CSR projects that mining companies implement. Additionally, this study found that mining companies implement telecommunications infrastructure projects to build more sustainable communities.

Theme 2: Sustainability levels of CSR projects in South African mining companies

Lifecycle of CSR projects

This study established that mining companies implement short- and long-term CSR projects. Although mining companies strive to implement long-term projects, a challenge remains in developing sustainable projects that will decrease the communities' dependence on the mine.

Short-term CSR projects

Short-term CSR projects take the form of donations. The rationale for implementing such projects is to address one need at a particular time, such as the lack of food. Although these donations provide temporary relief, they are not sustainable. They address the symptoms and not the root cause because they only benefit a small group of beneficiaries instead of the broader community. As a result, such projects are unsustainable and cannot benefit future generations.

Short-term projects provide temporary relief; I don't think they necessarily put communities in a place to sustain themselves ... I definitely think that's something that the mining industry still struggles to do, in terms of finding projects to invest in that are sustainable and that can allow communities to function without needing the mine. (Participant 9)

To mitigate this challenge and improve the sustainability of CSR outcomes, some mining companies have developed policies outlining that they will only implement long-term sustainable projects instead of short-term ones.

Long-term CSR projects

Long-term CSR projects have a longer life cycle and subsequently benefit more communities and beneficiaries. The study established that long-term projects, such as infrastructure, education, health and skills development, are sustainable because they benefit future generations, and their impact advances the community from an economic, social and environmental perspective.

Sustainable impact of corporate social responsibility projects

The TBL approach provides a framework to measure the sustainability of an organisation's CSR projects according to economic, social and environmental factors (Goel 2010). The study established that mining CSR projects advance sustainability in line with these factors.

Economic impact

Mining companies make a significant economic impact through their CSR projects, such as vocational skills training programmes for the unemployed and entrepreneurial training for small businesses. These initiatives have increased employment and, subsequently, household income, which are functional economic benefits to the communities and mines. The issuing of bursaries increases the employment potential for the beneficiaries upon successful completion of their studies, as the mines offer them employment.

Mining companies also prioritise local procurement and, therefore, source goods and services from within the community, which benefits the community economically. Road infrastructure projects have also unlocked the economic potential within the communities by allowing easy access in and between villages. As a result, people have opened businesses and become financially independent. Lastly, communities have realised a cost saving on data because of the installation of free Wi-Fi, car repairs because the new tar roads reduce the wear and tear effect compared to gravel roads, and travel costs to access health care services because clinics have now been built in the communities.

Social impact

Mining companies address the social needs of different classes of people living in mining communities, especially vulnerable groups such as females and minors, through health, education, skills training and infrastructure projects. Health-related projects, such as donating ambulances and building clinics, provide pregnant women with easy access to healthcare and safe childbirth. Road infrastructure projects have also assisted with this because pregnant women sometimes cannot get to a hospital in time to give birth because of the poor state of the roads, as emphasised by one participant:

Sometimes, we'll have a pregnant woman in that village. And when they are in labour, they don't arrive at the hospital; they must give birth on the road because of the poor road conditions. (Participant 1)

Crime, alcoholism and drug concerns within the communities are addressed by building community recreational centres. Moreover, gender-based violence initiatives are a priority for mining companies to create awareness and effect change in the fight against it.

Environmental impact

The study established that mining companies implement projects to promote environmentally sustainable practices. These include awareness and education programmes and initiatives to improve environmental conditions by planting trees, recycling, upgrading landfill sites and community clean-ups. Mining companies also ensure sustainable practices in the community by ensuring that waste is timeously collected and disposed of at mechanised landfills. Similarly, community members are encouraged to practise organic gardening methods and farming.

The study established that mining companies' CSR initiatives meet the call for mines to address the issue of economic, social and environmental sustainability that arise through mining activities. Furthermore, this indicates that mining CSR activities are aligned with the TBL model, focusing on the economic, social and environmental impact (Elkington 1997: 2).

Theme 3: Stakeholder engagement in achieving sustainable CSR outcomes

Stakeholder involvement

Stakeholder engagement is crucial for project success as it leads to stakeholder involvement and gratification (Shenhar 2001). This study established that mining companies ensure stakeholder engagement and participation in CSR project planning.

Local municipalities

The study determined that initial engagements with local municipalities ensure that the mine implements projects are aligned to the IDP. This provides an understanding of the communities' needs and municipalities' earmarked and approved projects. Mines partner with municipalities to execute infrastructure projects and will hand over these projects to the municipality involved upon completion. Both parties enter into a memorandum of understanding before the project commences. This agreement clarifies the roles and responsibilities of the mine and the municipality and states that, upon handover, the municipality will be responsible for the project's maintenance. This is important to ensure sustainability, as mines cannot maintain projects as it promotes high dependency on the mines. Therefore, the mine must engage with the municipality and align with the IDP to ensure sustainability, as emphasised by one participant.

We measure [sustainability] through the [IDP]... [We] know that if it's in the IDP, the community has identified it as a critical need. So, we know that it's something that the community will actually use. (Participant 12)

This finding partially contrasts Siyobi's (2015: 3) finding, who found that mining companies fail to implement projects due to the challenge of poor alignment with the national and local development plan. The study found that mining companies heavily rely on the local development plan to ensure the projects are aligned with the municipality's local development plan.

Communities

The study confirmed that communities are essential stakeholders to engage with in order to understand their needs from the initial project planning phase onwards. For a project to be sustainable, it must address the communities' needs, as they are the project beneficiaries. Mining companies engage with the communities in the preliminary stages of project planning by hosting regular stakeholder engagement fora, well represented by traditional authorities, NGOs, ward councillors, local business fora, community leaders and the local municipality.

During these engagements, stakeholders contribute to the decision-making, planning and implementation of projects. Stakeholders may express their views as such representation promotes a balance of perceptions during engagements. The study's participants also stated that when the mine cannot meet stakeholder expectations, transparent communication - instead of empty promises - is critical to build and maintain stakeholder trust. Ultimately, the mine uses the information obtained to co-create impactful projects that the communities need.

You use [stakeholder] engagement to understand what the community wants... [The] problem sometimes is that ideas are brought by [the] head office without [the] participation of the community. You cannot use a top-down approach, you must use a bottom-up approach, and the only way you will understand the need is by engaging with that community and ask[ing] them what is it that they need. (Participant 11)

These findings confirm those of El-Gohary et al. (2006: 599) that stakeholder involvement is essential to promote robust participation in CSR initiatives and for stakeholders to express their perceptions and expectations for project success, as it results in stakeholder involvement and gratification. On the other hand, these findings contradict the existing literature that the stakeholder engagement process is too controlled in the mining industry (Ihugba 2012). The participants stated that engagements were two-way communication, where stakeholders expressed their views and the mine listened and responded accordingly.

Stakeholder buy-in

The participants emphasised the role of stakeholder engagement in obtaining stakeholder buy-in for CSR projects, particularly from the communities involved. Buy-in from the project beneficiaries is essential as this provides them with a sense of ownership of the project. They observe it as their own instead of it belonging to the mine. When communities take ownership of a project, they will protect and defend the project infrastructure and ensure that it becomes a success. Conversely, when they feel as though a project is being forced on them - when they lack a sense of ownership - they will be inclined to damage the infrastructure and sabotage the project.

When you involve these communities, they get a sense of ownership to a particular project, and if they have sense of ownership, they're also able to defend and also protect those projects. (Participant 1)

This finding confirms that of Evans and Sawyer (2010) that a local community stakeholder group is critical for project development and that their buy-in and commitment are of utmost significance for project success.

Collaboration

The participants indicated that mining companies do not work in isolation to implement CSR projects. Collaboration in the form of partnerships is necessary for projects to succeed and be sustainable, and this can only be done through engagements. For instance, mines must collaborate with various government departments, the municipality, and other industry peers to execute CSR projects. For example, when the mine builds a clinic there has to be a collaboration with the Department of Health to ensure that the new facility has the required equipment and staff. Similarly, co-operation with the Department of Education is necessary for school infrastructure projects.

Although collaboration with mining industry peers is beneficial, some of the participants mentioned that this is currently not happening at the rate it should because each company wants credit for the work done. Instead of collaborating and realising more significant influence, mining companies often develop smaller projects in isolation.

With the mining peers, it is always a paper exercise... [You] find instances where we are literally sharing a community, and instead of collaborating, I don't know if it's the egos or what, but we'd rather all go to a school and do three different things when we could have come together and do one big thing. (Participant 7)

The study also established that mining companies collaborate with municipalities to address the issues of poor service delivery and lack of capacity through a programme called Municipality Capacity Building. The programme aims to address the technical skills gaps and empower local municipalities by building capacity for the efficient delivery of essential services and local economic development. The ultimate goal is to attract investment and stimulate growth and sustainable communities.

This finding confirms what Hamann (2003: 280) indicated - that co-creating CSR approaches and solutions with local communities and continuously engaging them help sustain trusting relationships. Tri-sector partnerships with civil society, the government, and the private sector contribute to sustainable CSR outcomes.

CONCLUSION

The analysis of the findings in terms of 1) the nature of CSR projects implemented, 2) the sustainability levels of CSR projects, and 3) stakeholder engagement in achieving sustainable CSR outcomes indicates only similarities between the cases, and no significant differences were noted.

The study established that collaboration is key to achieving greater sustainable CSR projects in the host communities; however, mining companies operating in shared communities are not collaborating at the rate they should in order to realise significant impact. Therefore, mining companies are encouraged to form partnerships with other mining houses to develop CSR projects that will have a more significant effect instead of implementing their own smaller projects in isolation.

The study further established that mining companies rely on the IDP document to guide their infrastructure projects. Thus, it is recommended that mining companies participate in the IDP document preparation process to provide input based on their engagements with the community so that the final document can be inclusive of and have balanced community needs.

In addition, because of the consultative and collaboration process, the study established that mining companies face the challenge of demands from diverse stakeholders. It is, therefore, recommended for mining companies to manage the expectations and demands of various stakeholders effectively. Prioritising stakeholder issues, risks and concerns in the stakeholder mapping and engagement planning process will be critical to achieving this. Management can address diverse stakeholder expectations by selecting stakeholder representatives based on their impact and influence on the business. Likewise, management should be transparent, effectively communicate to stakeholders, educate them on actual corporate mining policies and concerns, and inform them about realistic demands.

Revised conceptual framework

Figure 2 below indicates the revised conceptual framework proposed by the researchers. The study established that through consultation and collaboration there was a formation of stakeholder engagement fora and partnerships for project implementation. As a result, this contributed to the sustainability of CSR projects. This is because stakeholders' observations are considered, and CSR projects are co-created to approach the communities' need to resolve economic, social and environmental problems.

LIST OF REFERENCES

Afreh, M. 2016. Sustainability of corporate social responsibility outcomes: Perspectives from the Ghanaian mining sector. Unpublished doctoral thesis. University of Ghana. Accra, Ghana. [ Links ]

Agudelo, M., Johannsdottir, L. & David. B. 2020. Drivers that motivate energy companies to be responsible: A systematic literature review of corporate social responsibility in the energy sector. Journal of Cleaner Production 247: 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119094 [ Links ]

Alhaddi, H. 2015. Triple bottom line and sustainability: A literature review. Business and Management Studies 1: 6-10. https://doi.org/10.11114/bms.v1i2.752 [ Links ]

Arenas, D., Lozano, J.M. & Albareda, L. 2009. The role of NGOs in CSR: Mutual perceptions among stakeholders. Journal of Business Ethics 88: 175-197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0109-x [ Links ]

Arli, D.I. & Lasmono, H.K. 2010. Consumers' perception of corporate social responsibility in a developing country. International Journal of Consumer Studies 34: 46-51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2009.00824.x [ Links ]

Bailey, J. 2008. Assessment of triple bottom line financing interventions. [Online]. Available at: https://www.yellowwood.org/resource-library/ [Accessed on 22 January 2021]. [ Links ]

Bansal, P. 2005. Evolving sustainability: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strategic Management Journal 26: 197-218. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.441 [ Links ]

Bansal, P. & DesJardine, M.R. 2014. Business sustainability: It is about time. Strategic Organization 12: 70-78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127013520265 [ Links ]

Bice, S. 2014. What gives you a social licence? An exploration of the social licence to operate in the Australian mining industry. Resources 3: 62-80. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources3010062 [ Links ]

Bongwe, A. 2017. Benefits accruing to rural communities from the mining industry's corporate social responsibility projects in Moses Kotane municipality of the North West province. Unpublished Master's dissertation. University of Venda. Thohoyandou, South Africa. [ Links ]

Cheng, W.L. & Ahmad, J. 2010. Incorporating stakeholder approach in corporate social responsibility (CSR): A case study at multinational corporations (MNCs) in Penang. Social Responsibility Journal 6: 593-610. https://doi.org/10.1108/17471111011083464 [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. 2013. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Cronjé, F. & Chenga, C. 2009. Sustainable social development in the South African mining sector. Development Southern Africa 26: 413-427. https://doi.org/10.1080/03768350903086788 [ Links ]

Danielson, L. 2006. Architecture for change: An account of the mining, mineral and sustainable development project history. Berlin: Global Public Policy Institute. [ Links ]

DCGTA. 2009. Department of Co-operative Governance and Traditional Affairs: Report on the state of local government in South Africa. Pretoria: South African Government. [ Links ]

El-Gohary, N.M., Osman, H. & El-Diraby, T.E. 2006. Stakeholder management for public-private partnerships. International Journal of Project Management 24: 595-604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2006.07.009 [ Links ]

Evans, N. & Sawyer, J. 2010. CSR and stakeholders of small businesses in regional south Australia. Social Responsibility Journal 6: 433-451. https://doi.org/10.1108/17471111011064799 [ Links ]

Frederiksen, T. 2018. Corporate social responsibility, risk and development in the mining industry. Resources Policy 59: 495-505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2018.09.004 [ Links ]

Friedman, A.L. & Miles, S. 2001. Socially responsible investment and corporate social and environmental reporting in the UK: An exploratory study. The British Accounting Review 33: 523-548. https://doi.org/10.1006/bare.2001.0172 [ Links ]

Frynas, J.G. 2005. The false developmental promise of corporate social responsibility: Evidence from multinational oil companies. International Affairs 81: 581-598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2005.00470.x [ Links ]

Gibson, R. 2000. Favouring the higher test: Contribution to sustainability as the central criterion for reviews and decision under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act. Journal of Environmental Law and Practice 10: 39-54. [ Links ]

Goel, P. 2010. Triple bottom line reporting: An analytical approach for corporate sustainability. Journal of Finance, Accounting, and Management 1: 27-42. [ Links ]

Greenwood, M. 2007. Stakeholder engagement: Beyond the myth of corporate responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics 74: 315-327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9509-y [ Links ]

Hamann, R. 2003. Mining companies' role in sustainable development: The 'why' and 'how' of corporate social responsibility from a business perspective. Development Southern Africa 20: 237-254. https://doi.org/10.1080/03768350302957 [ Links ]

Hamann, R. 2004. Corporate social responsibility, partnerships, and institutional change: The case of mining companies in South Africa. Natural Resources Forum 28: 278-290. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-8947.2004.00101.x [ Links ]

Hilson, G. & Murck, B. 2000. Sustainable development in the mining industry: Clarifying the corporate perspective. Resources Policy 26: 227-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4207(00)00041-6 [ Links ]

Hooge, L. 2009. CSR in African mining. Inside Mining 2: 30-33. [ Links ]

Ihugba, B.U. 2012. CSR stakeholder engagement and Nigerian tobacco manufacturing subsector. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies 3: 42-63. https://doi.org/10.1108/20400701211197276 [ Links ]

Jenkins, H. & Obara, L. 2008. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the mining industry: The risk of community dependency. Corporate Responsibility Research Conference. Queens University, Belfast. [ Links ]

Jenkins, R. 2005. Globalization, corporate social responsibility and poverty. International Affairs 81: 525-540. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2005.00467.x [ Links ]

Kemp, D. & Owen, J.R. 2013. Community relations and mining: Core to business but not 'core business'. Resource Policy 38: 523-531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2013.08.003 [ Links ]

Khanifar, H., Nazari, K., Emami, M. & Soltani, H.A. 2012. Impact of corporate social responsibility activities on company financial performance. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business 3: 583-592. [ Links ]

Marais, L., Denoon-Stevens, S. & Cloete, J. 2020. Mining towns and urban sprawl in South Africa. Land Use Policy 93: 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.04.014 [ Links ]

Marinina, O. 2019. Analysis of trends and performance of CSR mining companies. Earth and Environmental Science 302: 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/302/1/012120 [ Links ]

Marrewijk, M.V. & Were, M. 2002. Multiple levels of corporate sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics 44: 107-119. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023383229086 [ Links ]

Matikainen, L. M. 2020. Enhancing sustainability in the mining industry through stakeholder engagement. Unpublished Master's dissertation. Tampere University. [ Links ]

Memela, N.M. 2020. The sustainability reporting practice of the South African mining industry: Community perspectives. Unpublished doctoral thesis. University of the Witwatersrand. Johannesburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

MMSD. 2002. Mining, minerals and sustainable development project: Breaking new ground. London: Earthscan London. [ Links ]

Moon, J. 2007. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to sustainable development. Sustainable Development 15: 296-306. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.346 [ Links ]

Ofori, D. 2010. Executive and management attitudes on social responsibility and ethics in Ghana: Some initial exploratory insights. Global Partnership Management Journal 1: 14-24. https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2010.12.14297 [ Links ]

Rodrigues, M. & Mendes, L. 2018. Mapping of the literature on social responsibility in the mining industry: A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production 181: 88-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/jJclepro.2018.01.163 [ Links ]

Schaltegger, S. & Burritt, R. 2018. Business cases and corporate engagement with sustainability: Differentiating ethical motivations. Journal of Business Ethics 147: 241-259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2938-0 [ Links ]

Selmier, W.T. & Newenham-Kahindi, A. 2021. A communities of place, mining multinationals and sustainable development in Africa. Journal of Cleaner Production 292: 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/jJclepro.2020.125709 [ Links ]

Shenhar, A.J. 2001. Contingent management in temporary, dynamic organizations: The comparative analysis of projects. Journal of High Technology Management Research 12: 239-271. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1047-8310(01)00039-6 [ Links ]

Siyobi, B. 2015. Corporate social responsibility in South Africa's mining industry: An assessment. The Governance of Africa's Resources Programme. South African Institute of International Affairs. [ Links ]

Van der Watt, P. & Marais, L. 2021. Implementing social and labour plans in South Africa: Reflections on collaborative planning in the mining industry. Resources Policy 71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.101984 [ Links ]

Walker, J. & Howard, S. 2002. Voluntary codes of conduct in mining industry. London: Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development Project. [ Links ]

Watts, P. & Holme, R. 1999. Corporate social responsibility. Geneva, Switzerland, World Business Council for Sustainable Development. [ Links ]

Whellams, M. 2007. The role of CSR in development: A case study involving the mining industry in South America. Unpublished Master's dissertation. St Mary's University. [ Links ]

Date submitted: 23 February 2022

Date accepted: 13 April 2022