Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Communitas

On-line version ISSN 2415-0525

Print version ISSN 1023-0556

Communitas (Bloemfontein. Online) vol.26 Bloemfontein 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150525/comm.v26.12

ARTICLES

Legitimisation of banking transparency in the institutional field discourse in South Africa

Anna OksiutyczI; George AngelopuloII

IDepartment of Communication Science, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa Email: aoksiutycz@uj.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7236-0924

IIDepartment of Communication Science, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa Email : georgeangelopulo@unisacommscience.co.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0244-3003

ABSTRACT

This article examines organisational transparency discourse in South African banking from 2008 to 2018. The financial crisis of 2008-2009 upset the global economy and resulted in general mistrust of banks and the global financial system. In addition to poor governance standards, inadequate transparency was identified as a key issue to be addressed in order to prevent future crises. The nature and consequences of banking transparency became a matter of worldwide debate and brought changes in banking regulation. While the extant literature focuses mainly on banking transparency in the context of accounting, this study examines transparency as a dynamic social and organisational phenomenon that is constituted through and reflected in organisational discourse, with both symbolic and practical implications. The study entails the analysis of 76 documents generated by the key actors in the institutional field of banking during the period from 2008 to 2018 in South Africa. The data analysis identifies two main discursive strands: one focused on market conduct transparency, and the other, which addresses the importance of banks' transparency in maintaining stability in the financial system.

Keywords: organisational transparency; corporate transparency; organisational discourse; organisational field; institutional fields; corporate governance; South African banking; discourse analysis

INTRODUCTION

Organisational transparency and openness have become ubiquitous terms expressing the expected standard of organisational behaviour. As the global economic crisis of 2008-2009 revealed, inadequate transparency in banking had a particularly far-reaching effect on society and its various systems. The calls for corporate transparency in banking can be observed in academic, professional and political quarters, in particular after the role of excessive lending by the banks worldwide has been identified as one of the main causes of the global economic recession of which the effects were felt in many parts of the world for many years thereafter. Although the South African banking system was not severely affected by the financial crisis, South African banks have been accused of collusion, discrimination and unfair practices. South African banks are also under scrutiny due to their importance to the local economy, their historical legacy, and the expectations of social contribution to the country's developing economy and transformation of society. In this context of global and national pressure, there are increased calls for improved standards of corporate transparency in banking in South Africa.

Research on transparency mainly focuses on financial transparency (Andries et al. 2017; Barth & Schipper 2008; Bushman et al. 2004; Saad & Jarboui 2015), and the legal dimension of corporate transparency in banking (Bartlett 2012; Brescia & Steinway 2013; Staikouras 2011). Studies on non-financial transparency are less common and relate organisational transparency to ethical dimensions of corporate governance and corporate social responsibility (Atkins et al. 2015; Dingwerth & Eichinger 2010; Wehmeier & Raaz 2012). This study refers to both financial and non-financial transparency.

This article views transparency as a social practice, which requires a "collective effort of reconfiguration through a continual process" (Lawrence et al. 2009). The primary arena for reconfiguration is an institutional field discourse, where the normative standards and regulatory processes that influence the meaning of transparency in any particular field are formed. The study demonstrates how the transparency discourse within the institutional field of banking in South Africa has shaped the understanding of what is normal and expected in terms of banking transparency during the time of unprecedented regulatory changes in banking during the decade after the financial crisis of 2008-2009.

The primary objective of this study is to establish how discourse in the institutional field of banking after the financial crisis of 2008-2009 represents the meaning of organisational transparency in South African banking. The study addresses two research questions:

RQ1: How has transparency been discursively constructed in the organisational field discourse in South Africa since the financial crisis of 2008-2009?

RQ2: How has transparency in banking been legitimised in the organisational field discourse in South Africa?

INSTITUTIONAL CONTEXT OF BANKING IN SOUTH AFRICA

South Africa has an internationally recognised banking system that is based on the British banking tradition. The industry is dominated by the so-called "big five" banks, ABSA, Capitec, First National, the Nedbank Group and Standard Bank, which hold 90% of banking assets (BusinessTech 2020). While South African banks managed to avoid the worst effects of the 2008-2009 financial crisis, like elsewhere, the crisis highlighted systemic problems and failures of governance in the banking system. In addition to the problems caused by the interconnectedness of the global system, the South African banking system has had its unique challenges, including high industry concentration and the legacy of apartheid, which for decades resulted in the exclusion of a large part of the population from participation in the financial system. In 2006, the Competition Commission of South Africa launched an enquiry into banking conduct, which resulted in the publication of a report that highlighted the shortcomings in consumer transparency (Competition Commission 2008).

Following the financial crisis of 2008-2009, discourse in the field of banking pointed to the need for sector-wide change. The issue of banking transparency was framed as one of the leading causes of the crisis. Subsequent policy changes, as outlined by the National Treasury and in the adoption of the Basel III rules in South Africa as of 2013, led to changes in rules, laws and regulations, including those related to transparency. The codes of corporate governance in King III (IoDSA 2012) and King IV (IoDSA 2016) also influenced banking related regulations and transparency discourse during the period after the financial crisis. At the same time, broader debates on the role of banks in the transformation of the South African economy, with issues of social justice, suitability and corporate citizenship, also shaped the meaning of banking transparency.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Institutional theory

The institutional theory serves as the theoretical foundation of this study. The theory is concerned with institutions and institutionalisation processes. According to Lawrence and Suddaby (2006: 216), institutions are "patterns of interactions supported by specific mechanisms of control". In term of this definition, organisational transparency can be considered a social institution; institutions can be formal and informal. Formal institutions are supported by rules, laws and contracts, while informal institutions are socially enforced. Formal institutions and informal institutions influence and change each other. Moreover, institutions are historically contingent and change over time (Thornton et al. 2012).

Institutions can be observed at the level of individual organisations, institutional (organisational) fields, and society. This study focuses on the institutional field level discourses. The concept of institutional field partially overlaps with concepts such as sector or industry. An institutional field comprises organisations that interact with each other, engage in a similar activity, and face similar constraints (Fredriksson et al. 2013). An institutional field may also include other actors such as suppliers, regulators and industry associations. Institutional fields are dynamic and can be affected by critical events in the environment (Marinova et al. 2012), such as crises, which can challenge the traditional way of doing things. Institutional fields influence organisational structures and values, and provide shared cognitive frameworks, meaning and guiding principles for action (Fredriksson et al. 2013; Ocasio et al. 2015). Every field has a set of vocabularies, narratives and theories, which are produced by the field actors. They are products of interactions, discourse and sense making by the actors within the field.

The regulatory dimension plays an important role in organisational fields. Regulations define conformity through the establishment of rules, instruments and sanctions that enforce adherence to the regulatory framework (Wicks 2001). Once established, such regulatory frameworks are difficult to ignore or reverse. Mohr and Neely (2009) argue that at the level of the institutional field, actors (such as the state) use their power strategically in order to establish organisational rules and structures with the aim of constituting and controlling the field.

The regulative elements of institutions cannot, however, be separated from other dimensions. Regulations reflect the broader societal context and sense-making schemas, interlinked with the normative pillar of institutionalisation. The normative dimension of institutions rests on social values and norms. The norms "introduce a prescriptive, evaluative and obligatory dimension into social life" (Scott 2014: 64), which define social roles and activities. Norms are the basis of a stable social order (Scott 2014). Normative and regulatory elements can constrain and regulate organisational behaviour by imposing legal, moral and social restrictions in terms of what is acceptable and what is not. The degree of conformity with these boundaries is used as an assessment of the social legitimacy of the actions of an organisation (Suddaby & Greenwood 2005).

Institutional theorists have been interested in the processes behind institutional change, including how some ideas take hold in organisations and become acceptable or desirable practices. El Driftar (2016) states that the ideas that are considered legitimate, thus, they adhere to the norms and standards accepted in society, are likely to be implemented. The use of specific arguments, words or rhetorical arguments facilitates the acceptance of new concepts and leads to the emergence of new practices (Munir 2005). The new practices are adopted through the process of collective interpretations and collective sense-making (Suddaby et al. 2013). Legitimacy assumptions in an organisational setting are shaped by communication and the use of language (Harmon et al. 2015; Hossfeld 2018). Various rhetorical strategies, such as rational, emotional and authority-based arguments, are used to legitimise changing ideas, processes and practices (Erkama & Vaara 2010).

Organisational transparency

Organisational transparency is a construct applicable to various societal institutions, and the subject of debate in numerous disciplines, including organisational studies, law, economics, politics, environmental protection, social reporting and sociology (Gawley 2008; Glenn 2014). Each of these fields considers transparency from a different perspective, and yet there are many similarities in the interpretation of the concept.

Although definitions of transparency are numerous and varied in the extent to which they are specific or general, most revolve around the provision of information. Rawlins (2009: 75) defines transparency as "the deliberate attempt to make available all legally reasonable information - whether positive or negative in nature - in a manner that is accurate, timely, balanced, and unequivocal, to enhance the reasoning ability of publics and hold organisations accountable for their actions, policies and practices". Bushman et al. (2004: 207) see transparency as the "availability of firms' specific information to those outside [...] firms". The framing of the provision of information as transparency dominates finance and governance literature (Bidabad et al. 2017; Manganaris et al. 2017). Forsbeack and Oxelheim (2015) state that the pervasive existence of information asymmetry makes the case for greater transparency. With organisational decisions based on public and private information, the absence or presence of information leads to a reduction or increase in uncertainly, with an impact on decisions and consequently their outcomes.

The view of transparency as information disclosure reveals taken-for-granted assumptions about the nature of information and a superficial approach to message construction, transmission and exchange (Lammers 2011). Conceptually, transparency as the purposeful sharing of impartial information by rational senders is solely linked to the sender's intent (Rawlins 2009; Schnackenberg & Tomlinson 2016), where outcomes are expected to correspond with the presumed intentions of the senders of the messages (Cornelissen et al. 2015). In contrast, some researchers argue that organisational transparency is a process of managing the choices of what and how to present information about an organisation. These choices may be discretionary or guided by regulations.

Transparency is a social process of managing what is visible and invisible, which produces multiple and "extensive kinds of control" (Flyverbom et al. 2015: 392). Albu (2014) labels the deliberate effort of selecting and presenting information by organisations a performative dimension of transparency. The organisational choices are influenced by interpretations of what constitutes right and wrong organisational actions. These perceptions are the results of the sense-making and sense-giving processes where various actors within the institutional field mobilise symbolic resources and shape the meaning of corporate transparency through methods, such as theorising, advocacy, defining, routinising, and even mythologising (Heath et al. 2010; Lawrence & Suddaby 2006; Mumby 2013).

METHODOLOGY

Discourse analysis is the research strategy of this study. Alvesson and Karreman (2000), while acknowledging the interrelatedness of discourses, distinguish between levels of organisational discourse. From local, micro-level discourse centred on specific texts and without paying much attention to the context, discourse may extend to generic, universal "epochal", mega-discourse - a historically developed system of ideas with a capital "D". In between, they identify meso-level discourse, which is relatively attuned to language and its context, and attentive to broader patterns, as opposed to grand organisational discourse that refers to "more or less standardised ways of referring to/constituting a certain type of phenomenon" (Alvesson & Karreman 2000). This study concentrates on the analysis of discourse at meso-level.

Discourse analysis does not privilege any specific method of analysis. In fact, Chouliaraki and Fairclough (2010: 1217) argue, "Protocols for analysis should be left deliberately contingent and porous". In this study, the researchers have utilised the discourse-historical approach (DHA) (Reisigl & Wodak 2016; Rheindorf & Wodak 2018). In the DHA, discourse is regarded as a cluster of context-dependent semiotic practices that are situated within specific fields of social action and linked to the argumentation on the validity claims of key social actors. The focus of this study is on the sub-themes of the discourse or topical threads within discourse called discursive strands (Rheindorf & Wodak 2018). Discursive strands have the following characteristics: topic continuity, strong intertextual links between different texts, relative temporal proximity, and initiating event or events that are topically or temporally bound (Rheindorf & Wodak 2018). In line with the DHA approach, the study paid attention to the connection of transparency discourse to other discourses (interdiscursivity), and the links and overlaps between the studied texts (intertextuality), as they provide the evidence of changes in the discourse over time (Wodak & Fairclough 2010). Within the discursive strands, the analysis of argumentative devices used in the legitimisation of issues has been also conducted, due to their importance to institutional processes (Furnari 2018).

Data sources were purposefully based on their relevance to the study. A source was considered relevant to this study if it contributed to the discourse on bank transparency in South Africa at the organisational field level. In this research, the following key organisational field players were considered: the South African Reserve Bank, the Bank Registrar, the National Credit Regulator, the National Treasury, the Financial Sector Conduct Authority (FSCA) and the Ombudsman for Banking Services. The banks' perspective was represented in documents and publications of the Banking Association of South Africa. The final sample comprised 76 documents that included regulatory acts, codes of corporate conduct, King III (loDSA 2012) and King IV (loDSA 2016), the Code of Banking Practice (BASA 2012), Basel III (BCBS 2011), nine industry reports and policy documents, and 54 articles published in the Banking Association journal Banker SA between 2012 and 2018.

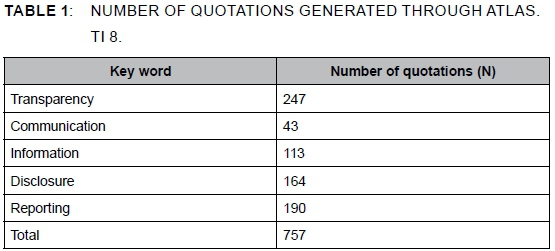

The analysis of texts in this study consisted of several streams of data condensation (coding), data restructuring (grouping codes into categories and themes), data display (quoted text, tables), and conclusion drawing (Miles et al. 2014; Collis & Hussey 2009). The analysis was performed with the aid of ATLAS.Ti 8 software. In the first stage of analysis, the auto-coding function of ATLAS.Ti 8 was used to identify the passages (quotations), which included the word transparency, as well as the related terms identified from the literature: information, disclosure and communication. After the initial reading of the documents, reporting was added as a relevant term (Table 1). A quotation in ATLAS.Ti 8 refers to a segment of text selected by the analyst with the aim of coding. The initial selection of quotations was reread and the irrelevant quotations, such as those generated from content lists, headings and references within the documents, were removed. During the process of coding, constitutive elements of frames, such as catchphrases, problem definitions, statements of cause and effect, solutions, appeals and rhetorical devices (Litrico & David 2017), were sought. The identified codes were grouped into larger categories and themes.

RESULTS

In this section, two overlapping but distinctive discursive strands in banking transparency discourse in South Africa are discussed first, namely transparency as a factor in achieving financial stability (transparency for financial system stability) and consumer transparency (transparency in market conduct). Then the researchers discuss how transparency in South African banking is legitimised using market-related and ethical arguments.

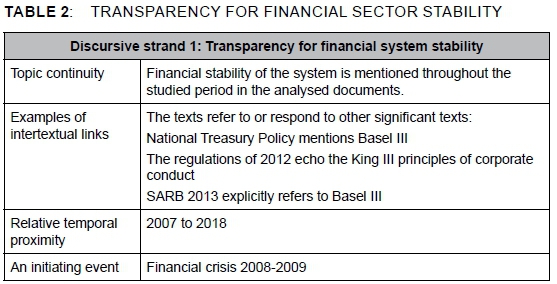

Discursive strand 1: Transparency for financial system stability

The characteristics concerning discursive strand 1 are summarised in Table 2.

The studied policy documents (in particular those from the first few years after the crisis) explicitly mention the financial crisis as the main reason for the need to introduce changes related to transparency in banking globally and in South Africa. For instance, A safer financial sector to serve South Africa better (National Treasury 2011), which outlined policy direction after the financial crisis, explicitly refers to "lessons" from the financial crisis: "One of the key lessons from the financial crisis is the need to assess risks to the system as a whole" (National Treasury 2011: 26).

Several documents (BCBS 2011; National Treasury 2011; National Treasury 2013; SARB 2017) state that the main objective of these new policies and subsequent regulations is to achieve financial stability. The SARB definition provides the following explanation of financial stability, namely, "a financial system that is resilient to systemic shocks, facilitates efficient financial intermediation and mitigates the macroeconomic costs of disruptions in such a way that confidence in the system is maintained" (SARB 2017). The issue of preserving financial stability is a recurring theme, not only in the immediate period after the crisis, but also in later documents. In the foreword to Implementing the Twin Peaks model of financial regulation, the National Treasury (2013) motivates increased regulation by highlighting the weaknesses of "light touch" regulations prior to the crisis. Financial stability was to be achieved by introducing new laws, regulations, and the creation of new regulatory bodies. Basel III regulations, which were adopted by South Africa in 2013, emphasise three areas for improvement - governance, risk management and transparency - in order to prevent the next global financial meltdown.

Generally, the notion that banking transparency needs to be enhanced has been consistently emphasised by different actors in the banking field, including the industry body, the Banking Association of South Africa. The purpose of increased transparency is to improve the effectiveness of monitoring the performance and behaviour of banks as a way of preventing financial crises. Basel III states that the goal of new disclosure requirements is "to improve the usefulness and relevance of financial reporting for stakeholders, including prudential regulators" (BCBS 2011: 6). To achieve the aim of monitoring the banking system better, the financial disclosure dimensions that are uniquely applicable to banks were introduced. Specific information that banks are required to disclose to the regulators and the public include regulatory capital, a countercyclical capital buffer, leverage ratio, and the liquidity coverage ratio (Brits 2012). Discussion on these financial disclosure dimensions exceeds the scope of the study. The most important point is that these new requirements significantly increased the scope and details of financial information provided to the stakeholders by the banks.

New regulations affecting the disclosure by banks in South Africa, in line with Basel III standards, were implemented in 2013. The National Treasury shifted from micro-prudential supervision of banks (focusing on the financial condition of the individual financial organisations) to macro-prudential supervision, which aimed to maintain the stability of the whole system (National Treasury 2011). According to Ernst and Young (2017: 12), with the shift towards macro-prudential supervision, "additional reporting and emphasis on macro-prudential indicators is likely to result in additional metrics, focused on maintaining financial stability".

One specific area in the discourse on banking transparency is risk transparency. This dimension of banking transparency is identifiable in the discourse on identifying and managing specific risks faced by banks. Basel III (BCBS 2011) and the Banking Regulations (2012), for example, highlight the necessity of managing risks through processes of risk monitoring, awareness and disclosure.

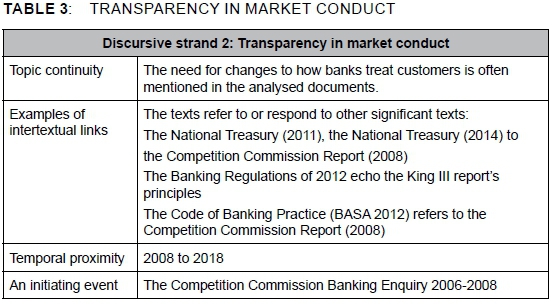

Discursive strand 2: Transparency in market conduct

The second discursive strand focuses on the transparency of banks towards consumers. In the organisational field of banking, transparency in market conduct denotes issues related to consumer transparency. As with the transparency for banking system stability discursive strand, both the implications of inadequate transparency and the effects of improved transparency are present in the texts. Although overlapping with the transparency for financial system stability discursive strand, the transparency in market conduct discursive strand has some distinctive characteristics that define it as a separate discursive strand (Table 3).

The Competition Commission Banking Enquiry 2006-2008 became a discursive event that initiated this discursive strand. An outcome of a two-year-long enquiry into banking practices in South Africa was a report published in 2008, which highlighted the negative bank practices affecting South African consumers. Referring to the findings of the Competition Commission, as expressed in the Banking Enquiry report (2008), A safer financial sector to serve South Africa better (National Treasury 2011) policy document outlined the new direction in terms of bank consumer practices, including consumer transparency. Consumer treatment issues were discussed in Treating customers fairly in the financial sector (National Treasury 2014) in a framework modelled on a similar document in the UK. One of the outcomes of the new government policy, influenced by international trends, was the introduction of the Twin Peaks model of banking supervision. The Financial Sector Conduct Authority was established as a separate body overseeing market conduct, in addition to a prudential supervisory body located within the SARB, the Prudential Authority.

The twin peaks approach is regarded as the optimal means of ensuring that transparency, market integrity, and consumer protection receive sufficient priority, and given South Africa's historical neglect of market conduct regulation, a dedicated regulator responsible for consumer protection, and not automatically presumed to be subservient to prudential concerns, is probably the most appropriate way to address this issue (National Treasury 2011: 29).

Consequently, in Treating customers fairly in the financial sector (National Treasury 2014), transparency is highlighted as an important measure in consumer protection:

The new regulatory powers proposed in the FSR Bill are an important development towards enabling the FSCA to achieve the comprehensive consumer protection framework described in this document. To complement these strengthened regulatory powers, the various accountability measures proposed for the FSCA in the FSR Bill - including measures relating to Parliamentary and National Treasury reporting, transparency and consultation, and appeals and reviews - provide important checks and balances (National Treasury 2014: 37).

The Banking Enquiry report (Competition Commission 2008) specifically identified the lack of transparency towards consumers as a factor that perpetuates the imbalance of power between consumers and banks as an issue requiring intervention. Among the issues identified as requiring resolution through increased transparency in the market conduct of banks are various aspects of product and service transparency, opacity of fees and charges, interest rate calculations and credit-related information, and the complexity of language used in terms and conditions.

The complexity of products and prices (combined with inadequate transparency and disclosure), the cost and difficulty for consumers in switching banks, and the reluctance of the major banks to engage in vigorous price competition with each other that could 'spoil' the market for them in the long term - all contribute to producing a situation where the prices charged to consumers for transactional accounts and payment services are probably (although with some exceptions) well above the level that effective competition would allow (Competition Commission 2008: 18).

A lack of transparency in banking products is presented as an economic factor that limits competition, while the confusing product information prevents consumers from making informed financial decisions. In addition, inadequate and confounding information provided to consumers limits consumer choices by, for example, discouraging customers from switching accounts or banks. In response to the Competition Commission report (2008), the Banking Association introduced the new Code of Banking Practice (BASA 2012), which pledged the provision of better information to consumers.

The Code of Banking Practice (BASA 2012) states that banking transparency needs to be enhanced to improve the relationship between banks and their consumers and to build trust in the banking system as a whole. Trust or confidence in the system is the desired outcome of transparency as stipulated in several documents.

This Code has been developed to: [...] 2.2 increase transparency so that you can have a better understanding of what you can reasonably expect of the products and services; 2.3 promote a fair and open relationship between you and your bank; and 2.4 foster confidence in the banking system (BASA 2012: 4).

However, given the regulators' overarching transparency principle, non-disclosure should be the exception rather than the rule, so that the deterrent factor of enforcement is not blunted. The reputational consequences of public disclosure should be an effective deterrent to unfair customer treatment (National Treasury 2013: 71).

The nature and effectiveness of bank transparency towards consumers remain ongoing themes in the transparency discourse. While in the initial period following the release of the Competition Commission Report (2008), transparency was presented as the panacea for the unjust treatment of bank customers, in later years it was suggested that transparency towards consumers, as currently practised, is insufficient to ensure fair consumer treatment. The South African Reserve Bank, in Vision 2025 (SARB 2018) suggests that transparency alone, without deeper changes in banking, is not a sufficient condition to change the market conduct of banks.

Legitimisation of banking transparency

Previous studies have shown that discourses are used to frame issues and phenomena in certain ways within organisational fields (Furnari 2018). Developing connections between cause and effect within an organisational field, after high-impact events, legitimises new ideas, according to Munir (2005). As discussed above, the connection between financial stability and transparency is indicated frequently in the analysed documents, where it is argued that inadequate transparency in banking was one of the causes of the financial crisis.

Market-related arguments for more transparency

Transparency, according to the analysed texts, leads to more efficient financial markets, more competition, market discipline, and better integrity in the industry. Stability, efficiency, resilience and strength in the financial system are presented frequently in the discourse as dominant outcomes of transparency. The ensuing stability of the system is also portrayed as a means to achieve other outcomes, for example, the economic growth of the country, as illustrated in the quote from the SARB report: "Information transparency is aimed at eliminating inefficiencies and decreasing risks across the industry" (SARB 2018: 9).

Furthermore, the appeal to a greater social good such as the effect on the economy and public finances is given as a reason for further regulation, alongside the argument of improving the financial system as a whole. The new ethical standards for bank conduct emerged from the discourse, highlighting their role in maintaining the sound financial system and thus "protecting" the country's economy: "A financial crisis can impose considerable economic costs in lost output and through a substantial deterioration in public finances" (National Treasury 2013: 27).

Similar views aligned with market logic are expressed in the SARB's document Vision 2025 (SARB 2018). Naturally, arguments used in discourses are not removed from the ideological stance represented by those who participate in the discourse (Bennett 2015). Hence, arguments associated with market logic such as industry innovation, efficiency, risk reduction, increased competition and market efficiency appear in the texts along with the concept of transparency. "The goals that guide the vision tend to focus on high-level issues such as competition, innovation, transparency, preparing for future changes in the economy, and system stability" (SARB 2018: 5).

Ethics and social justice-related arguments

Transparency in the organisational field of banking discourse is often framed in terms of broader socio-economic outcomes, such as social development, growth of social and economic capital, and improved social wellbeing for everyone. This is perhaps a sign of a shift from a pure market perspective on the role of banks towards an ethical perspective, which focuses on banks as socially responsible contributors to society as a whole. Specific issues related to the dominant social discourse in South Africa, such as poverty and inequality, are highlighted in the transparency discourse. For instance, a Banker SA (Zwane 2013) article states the following about the effects of banking transparency: "It is expected that South Africans will be better equipped to improve their lives, through investing and creating wealth, and avoiding poverty traps" (Zwane 2013: 12).

Transparency, especially in the transparency in market conduct discursive strand, has also been positioned in a social justice frame, and particularly with a reference to the consumer-bank relationship. Transparency is framed as an antidote to information asymmetry. "Asymmetry of information between financial services consumers and financial institutions makes consumers vulnerable to exploitation" (National Treasury 2013: 47). Information asymmetry is a phenomenon that implies power inequality, and as such is defined as undesirable. Consequently, transparency is seen as an instrument for the enforcement of corporate governance and the ethical conduct of banks.

Although emotional appeals are rare in the organisational field of banking discourse, occasionally direct language is evident in the documents. References to exploitation and market abuses link the absence of transparency to unethical business behaviour and highlight the negative connotations of inequality and injustice. "[T]here is a need to develop rigorous market conduct regulations for the financial sector in order to deal with possible market abuses and ensure adequate consumer/investor protection" (National Treasury 2013: 15).

The implications of financial inclusion go beyond the impact on individual consumers. Financial inclusion is presented as consequential to society as a whole. The National Treasury (2011: 7) states, for example, "Sustainable and inclusive economic growth and development will be aided by improving access to financial services for the poor, vulnerable and those in rural communities". A further element identifiable in the texts is the responsibility of banks to consumer education, and ultimately as an essential element in the transformation of the South African financial sector. The Financial Sector Code makes it incumbent on banks to engage in consumer education with the aim of "empowering consumers with the knowledge to enable them to make more informed decisions about their finances and lifestyles" (DTI 2012: 122).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Researchers have previously highlighted the important role of organisational field-level discourse in shaping organisational practice (Furnari 2018; Hardy & Marguire 2010). Most significantly, organisational field-level discourse facilitates a broad intersubjective agreement on concepts and phenomena, as in the case of organisational transparency in banking. While arguments change as social and historical contexts change, even if the meaning ensuing from the discourse is subject to further contestation, generally field-level discourses lead to the emergence of institutional practices, especially if they are enforced by legislation.

The two discursive strands identified in this study had different structuring events or structuring moments, during which the "social construction of shared meanings was accelerated" (Bartlett et al. 2007: 286). Previously, financial transparency focused on short-term organisational performance and a limited stakeholder audience of mostly shareholders and investors, but the financial crisis highlighted the severe limitation of such an approach. Furthermore, financial transparency discourse predominantly reflected and served the interests of banks as individual business organisations (Gawley 2008), while after the crisis the interest shifted towards transparency that benefits the industry as a whole. Furthermore, the discourse suggests causal relationships between inadequate transparency and the risks to the financial system.

The Competition Commission enquiry into banking concluded at the same time as the onset of the crisis, in 2008, and was the initiating event for changes with respect to transparency in market conduct. Furthermore, the transparency in market conduct discursive strand in South Africa has its roots in the country's unique historical and economic circumstances. This strand of the banking transparency discourse represents a significant change in the normative perceptions of what bank disclosure to consumers ought to be in the South African context, where many consumers are poor and vulnerable. The studied texts portray transparency as one of the factors contributing to the widening of financial inclusion - a concept with positive ethical connotations of fairness and social justice.

Successful changes in an organisational field require that the messages within the field be linked to other relevant societal discourses (Erkama & Vaara 2010). The goals of financial system stability and financial inclusion are present in the discursive spaces where corporate transparency discourse overlaps with the discourses of corporate governance and transformation in South Africa's economy and society. Broadly speaking, there is social consensus in the discourse that banking transparency adds positive value to society at various levels. This social agreement has resulted in the introduction of supporting legislation, rules, regulations and laws that require that banks provide specific information, in particular ways, to stipulated stakeholders such as consumers.

The current study analysed the discourse in the official texts produced by key players in the institutional field of banking, in particular the regulators and the Banking Association of South Africa. Future research should include the texts produced by the individual banks. Further research should also investigate the impact of the changes in the regulations and normative perceptions about transparency that occurred after 2008 on the transparency practices of banks.

REFERENCES

Albu, O.B. 2014. Transparency in organizing: A performative approach. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School. [ Links ]

Alvesson, M. & Karreman, D. 2000. Varieties of discourse: On the study of organizations through discourse analysis. Human Relations 53(9): 1125-1149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700539002 [ Links ]

Andries, K., Gallemore, J. & Jacob, M. 2017. The effect of corporate taxation on bank transparency: Evidence from loan loss provisions. Journal of Accounting and Economics 63:307-328. https://doi.org/10.1016/jJacceco.2017.03.004 [ Links ]

Atkins, J.F., Solomon, A., Norton, S. & Joseph, N.L. 2015. The emergence of integrated private reporting. Meditari Accountancy Research 23(1):28-61. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-01-2014-0002 [ Links ]

Banking Regulations. 2012. Republic of South Africa. Government Gazette 35950. Available at: http://www.treasury.gov.za/legislation/35950_12-12_ReserveBankCV01.pdf [Accessed on 18 May 2018]. [ Links ]

Barth, M.E. & Schipper, K. 2008. Financial reporting transparency. The Journal of Accounting, Auditing, and Finance 23(2): 173-190. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X0802300203 [ Links ]

Bartlett, R.P. 2012. Making banks transparent. Vanderbilt Law Review 65(2): 293-386. [ Links ]

BASA (The Banking Association South Africa). 2012. Code of Banking Practice. Available at: https://www.banking.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Code-of-Banking-Practice-2012.pdf [Accessed on 18 May 2018]. [ Links ]

BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision). 2011. Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems. Bank for International Settlements. Available at: https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs189.pdf [Accessed on 18 May 2018]. [ Links ]

Bennett, S.T. 2015. Construction of migrant integration in British public discourse. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Poznan: Adam Mickiewicz University. [ Links ]

Bidabad, B., Amirostovar, A. & Sherafati, M. 2017. Financial transparency, corporate governance and information disclosure of the entrepreneur's corporation in Rastin banking. International Journal of Law and Management 59(5): 636-651. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLMA-01-2016-0003 [ Links ]

Brescia, R.H. & Steinway, S. 2013. Scoring the banks: Building behaviourally informed community impact report card for financial institutions. Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law 18(2): 339-378. [ Links ]

Brits, M. 2012. Resilience. Banker SA. 1: 9-13. [ Links ]

Bushman, R.M., Piotroski, J.D. & Smith,A.J. 2004. What determines corporate transparency? Journal of Accounting Research 42(2): 207-252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2004.00136.x [ Links ]

BusinessTech. 2020. South African banking sector is dominated by 5 names - who control almost 90% of assets. 19 July. Available at: https://businesstech.co.za/news/banking/416057/south-africas-banking-sector-is-dominated-by-5-names-who-control-almost-90-of-all-assets/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20SARB%2C%20South,(March%202019%3A%2090.5%25).&text=Total%20banking%20sector%20assets%20grew,2020%20(March%202019%3A%20R5. [Accessed on 5 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Chouliaraki, L. & Fairclough, N. 2010. Critical discourse analysis in organizational studies: Towards an integrationist methodology. Journal of Management Studies 47(6): 1213-1218. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00883.x [ Links ]

Collis, J. & Hussey, R. 2009. Business research: A practical guide for undergraduate and postgraduate students. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Competition Commission (South Africa). 2008. Banking enquiry: Report to the Competition Commissioner by the enquiry panel. Executive overview. Available at: https://www.southafrica.to/Banks/news/2008/competition-commission-banking-enquiry.pdf [Accessed on 18 May 2019]. [ Links ]

Cornelissen, J.P., Durand, R., Fiss, P.C., Lammers, J.C. & Vaara, E. 2015. Putting communication front and center in institutional theory and analysis. Academy of Management Review40(1): 10-27. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0381 [ Links ]

Dingwerth, K. & Eichinger, M. 2010. Tamed transparency: How information disclosure under the global reporting initiative fails to empower. Global Environmental Politics 10(3): 74-96. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00015 [ Links ]

DTI (Department of Trade and Industry). 2012. The Financial Sector Code, notice 997 of 2012, 26 November 2012. Available at: https://www.thedti.gov.za/economic_empowerment/docs/beecharters/Financial_sector_code.pdf [Accessed on 7 February 2020]. [ Links ]

El-Diftar, D. 2016. Institutional investors and voluntary disclosure and transparency in Egypt. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Cardiff: Cardiff Metropolitan University. [ Links ]

Erkama, N. & Vaara, E. 2010. Struggles over legitimacy in global organisational restructuring: A rhetorical perspective on legitimation strategies and dynamics in shutdown case. Organizational Studies 31(7): 813-839. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840609346924 [ Links ]

Ernst & Young. 2017. Financial Sector Regulation Act, implementing twin peaks and the impact on the industry. Available at: https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-financial-sector-regulation-act-twin-peaks/$FILE/ey-financial-sector-regulation-act-implementing-twin-peaks-and-the-impact-on-the-industry.pdf [Accessed on 12 May 2019]. [ Links ]

Flyverbom, M., Christensen, L.T. & Hansen, K. 2015. The transparency-power nexus: Observation and regularising control. Management Communication Quarterly 29(3): 385-410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318915593116 [ Links ]

Forsbeack, J. & Oxelheim, L. 2015. The multifaceted concept of transparency. In: Forsbeack, J. & Oxelheim, l. (eds). The Oxford handbook of economic and institutional transparency. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199917693.001.0001 [ Links ]

Fredriksson, M., Pallas, J. & Wehmeier, S. 2013. Public relations and neo-institutional theory. Public Relations Inquiry 2(2): 183-203. https://doi.org/10.1177/2046147X13485956 [ Links ]

Furnari, S. 2018. When does an issue trigger change in the field? A comparative approach to issue frames, field structures and types of field change. Human Relations 71(3): 321-348. https://doi.org/101177/0018726717726861 [ Links ]

Gawley, T. 2008. University administrators as information tacticians: Understanding transparency as selective concealment and instrumental disclosure. Symbolic Interaction 31(2): 183-204. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.2008.3L2.183 [ Links ]

Glenn, H.P. 2014. Transparency and closure. In: Ala'I, P. & Vaughn, R.G. (eds). The research handbook on transparency. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

Hardy, C. & Maguire, S. 2010. Discourse, field-configuring events, and change in organizations and institutional fields: Narratives of DDT and the Stockholm Convention. Academy of Management Review 53(6): 1365-1392. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.57318384 [ Links ]

Harmon, D.J., Green, S.E. & Goodnight, G.T. 2015. A model of rhetorical legitimation: The structure of communication and cognition underlying institutional maintenance and change. Academy of Management Review 40(1): 76-95. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2013.0310 [ Links ]

Heath, R., Motion, J. & Leitch, S. 2010. Power and public relations: Paradoxes and programmatic thoughts. In: Heath, R.L. (ed.). The Sage handbook of public relations. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Hossfeld, H. 2018. Legitimation and institutionalization of managerial practices: The role of organizational rhetoric. Scandinavian Journal of Management 34: 9-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2017.11.001 [ Links ]

IoDSA (Institute of Directors South Africa). 2012. King Report on Corporate Governance in SA. Available at: https://www.iodsa.co.za/page/kingIII [Accessed on 10 February 2017]. [ Links ]

IoDSA (Institute of Directors South Africa). 2016. King IV Report and Code of Corporate Governance. Available at: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iodsa.co.za/resource/resmgr/king_iii/King_Report_on_Governance_fo.pdf [Accessed on 13 May 2019]. [ Links ]

Lammers, J.C. 2011. How institutions communicate: Institutional messages, institutional logics, and organizational communication. Management Communication Quarterly 25(1): 154-182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318910389280 [ Links ]

Lawrence, T.B. & Suddaby, R. 2006. Institutions and institutional work. In: Clegg, S.R., Hardy, C.S.R., Lawrence, T.B. & Nord, W.R. (eds). The Sage handbook of organization studies. (Second edition). London: Sage. [ Links ]

Lawrence, T.B., Suddaby, R. & Leca, B. 2009. Introduction: Theorizing and studying institutional work. In: Lawrence, T.B., Suddaby, R. & Leca, B. (eds). Institutional work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511596605 [ Links ]

Litrico, J.B. & David, R.J. 2017. The evolution of issue interpretation within organisational fields: Actor positions, framing trajectory and field settlement. Academy of Management Journal 60(3): 986-1015. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0156 [ Links ]

Manganaris, P., Becalli, E. & Dimitropolous, S. 2017. Bank transparency and the crisis. The British Accounting Review 49: 121-137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2016.07.002 [ Links ]

Marinova, S., Child, J. & Marinov, M. 2012. Institutional field of outward foreign direct investment: A theoretical extension? Advances in Institutional Management 25: 233-261. https://doi.org/101108/S1571-5027(2012)0000025017 [ Links ]

Miles, M.B., Huberman, A.M. & Saldana, J. 2014. Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Mohr, J. & Neely, B. 2009. Modelling Foucault: Dualities of power in institutional fields. In: Meyer, R., Sahlin, K., Ventresca, M. & Walgenbach, P. (eds). Institutions and ideology. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, Book 27. Bingley: Emerald. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0733-558X(2009)0000027009 [ Links ]

Mumby, D. 2013. Organizational communication: A critical approach. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Munir, K.A. 2005. The social construction of events: A study of institutional change in the photographic field. Organizational Studies 26(1): 93-112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605049463 [ Links ]

National Treasury. 2011. A safer financial sector to serve South Africa better. Available at: http://www.treasury.gov.za/twinpeaks/20131211%20-%20Item%202%20A%20safer%20financial%20sector%20to%20serve%20South%20Africa%20better.pdf [Accessed on 18 May 2019]. [ Links ]

National Treasury. 2013. Implementing a twin peaks model of financial regulation in South Africa. The Financial Regulatory Reform Steering Committee. Available at: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/twin-peaks-01-feb-2013-final.pdf [Accessed on 18 May 2019]. [ Links ]

National Treasury. 2014. Treating customers fairly in the financial sector: A market conduct policy framework for South Africa. Available at: http://www.treasury.gov.za/public%20comments/FSR2014/Treating%20Customers%20Fairly%20in%20the%20Financial%20Sector%20Draft%20MCP%20Framework%20Amended%20Jan2015%20WithAp6.pdf [Accessed on 18 May 2019]. [ Links ]

Ocasio, W., Lowenstein, J. & Nigam, A. 2015. How streams of communication reproduce and change institutional logics: The role of categories. Academy of Management Review 40(1): 28-48. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2013.0274 [ Links ]

Rawlins, B. 2009. Give the emperor a mirror: Towards developing a stakeholder measurement of organizational transparency. Journal of Public Relations Research 21(1): 71-99. https://doi.org/10.1080/10627260802153421 [ Links ]

Reisigl, M. & Wodak, R. 2016. The discourse-historical approach (DHA). In Wodak, R. & Meyer, M. (eds). Methods of critical discourse studies. London: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739342-4 [ Links ]

Rheindorf, M. & Wodak, R. 2018. Borders, fences, and limits - protecting Austria from refugees: Metadiscursive negotiation of meaning in the current refugee crisis. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16(1/2): 5-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2017.1302032 [ Links ]

Saad, K.B. & Jarboui, A. 2015. Does corporate governance affect financial communication transparency? Empirical evidence in the Tunisian context cogent. Economics & Finance 3: 1090944. DOI: 10.1080/23322039.2015.1090944 [ Links ]

SARB (South African Reserve Bank). 2017. Financial stability review. Available at: https://www.resbank.co.za/Lists/News%20and%20Publications/Attachments/7786/First%20edition%20FSR%20April%202017.pdf [Accessed on 7 February 2020]. [ Links ]

SARB (South African Reserve Bank). 2018. Vision 2025. The national payment system framework and strategy. Available at: https://www.resbank.co.za/RegulationAndSupervision/NationalPaymentSystem(NPS)/Documents/Overview/Vision%202025.pdf [Accessed on 18 May 2020]. [ Links ]

Schnackenberg, A.K. & Tomlinson, E.C. 2016. Organizational transparency: A new perspective on managing trust in organisation-stakeholder relationship. Journal of Management 42(7): 1784-1810. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314525202 [ Links ]

Scott, W.R. 2014. Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, identities. (Fourth edition). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.3917/mana.172.0136 [ Links ]

Staikouras, P.K. 2011. Universal banks, universal crises? Disentangling myths from realities in quest of new regulatory and supervisory landscape. Journal of Corporate Law Studies 11(1): 139-175. https://doi.org/10.5235/147359711795344172 [ Links ]

Suddaby, R. & Greenwood, R. 2005. Rhetorical strategies of legitimacy. Administrative Science Quarterly 50: 35-67. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2005.50.L35 [ Links ]

Suddaby, R., Seidl, D. & Lê, J.K. 2013. Strategy-as-practice meets neo-institutional theory. Strategic Organization 11(3): 329-344. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127013497618 [ Links ]

Thornton, P.H., Ocasio, W. & Lounsbury, M. 2012. The institutional logic perspective: A new approach to culture, structure and process. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199601936.001.0001 [ Links ]

Wehmeier, S. & Raaz, O. 2012. Transparency matters: The concept of organizational transparency in the academic discourse. Public Relations Inquiry 1(3): 337-366. https://doi.org/10.1177/2046147X12448580 [ Links ]

Wicks, D. 2001. Institutionalized mindsets of invulnerability: Differentiated institutional fields and the antecedents of organizational crisis. Organizational Studies 22(4): 659-692. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840601224005 [ Links ]

Wodak, R. & Fairclough, N. 2010. Recontextualisng European higher education policies: The cases of Austria and Romania. Critical Discourse Studies 7(1): 19-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405900903453922 [ Links ]

Zwane, M. 2013. Consumer education - the key to financial inclusion. Banker SA. 8: 12-15. [ Links ]

Date submitted: 30 July 2021

Date accepted: 03 November 2021

Date published: 31 December 2021