Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Communitas

On-line version ISSN 2415-0525

Print version ISSN 1023-0556

Communitas (Bloemfontein. Online) vol.26 Bloemfontein 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150525/comm.v26.7

ARTICLES

Facilitating inclusive citizenry engagement in a provincial government

Tsietsi MmutleI; Estelle de BeerII

ISchool of Communication Studies, North-West University, Mahikeng Campus, Mahikeng, South Africa Email : tsietsi.mmutle@nwu.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6789-4534

IIDepartment of Business Management, Division of Communication Management, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa Email: estelle.debeer@up.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1265-2703

ABSTRACT

The study provides a narrative exploration of the contribution and accentuated value of strategic communication management (SCM) in facilitating and fostering inclusive citizenry engagement through bottom-up constructed governance initiatives and citizenry-oriented sustainability programmes, using the North-West Province of South Africa as the research context. The study ponders on how a provincial sphere of government, as empowered by the national sphere, uses strategic communication to identify and address citizenry needs, interests and expectations from a participatory perspective. The objective was to determine the extent to which SCM enables purposeful and deliberate bottom-up centred public participation opportunities for inclusive citizenry engagement to be realised. Qualitative focus group and semi-structured interviews enabled the study to interrogate and advance how strategic communication can be positioned to attain, promote and encourage ongoing engagement opportunities that are poised as more inclusive and that are premised on the idea of co-governance and citizenry-grounded sustainability programmes. The study found that provincial government communication was simply operational in nature, and more often, performed and facilitated without a strategic purpose nor deliberate intention by hemispheric and less-skilled communicators with little regard for communication management theory. Consequently, little evidence exists on how citizenry interests are identified and addressed to encourage the necessary responsive actions by ordinary citizens.

Keywords: strategic communication; inclusive citizenry engagement; governance; sustainability; participation; government communication

INTRODUCTION

A number of publications expose the accentuated value of strategic communication in various case studies, with specific reference to institutions and the global landscape (Lock et al. 2020; Zerfass et al. 2018; Nothhaft et al. 2018; Ihlen & Frederiksson 2018; Heide et al. 2018; Nothhaft 2016). However, little is known about how contemporary government spheres use strategic communication to advance inclusive citizenry engagement through public participation podia (Sebola 2017; Lues 2014). The use of strategic communication management often pays lip service and emphasises top-down information dissemination processes rather than a clear and precise communication-based strategy aimed at creating an impactful and organised community of engaged citizenry. The notion of inclusive citizenry engagement is about the right of the people to define the public good, determine the policies by which they will seek the good, and to reform or replace institutions that do not serve that particular good.

Inclusivity of citizens can also be summarised as a means of working together to make a difference in the civil life of communities and developing the combination of skills, knowledge, values and motivation in order to make that difference. It means promoting a quality of life in a community, through political and non-political processes. The role of communication that is practised and applied for a strategic purpose is therefore important in advancing inclusive citizenry engagement. It is through the strategic role of communication that debates, discussions and transformative dialogue can be realised as meaningful. Communication creates a platform where actors become actively involved in determining important aspects of engaging with each other -and subsequently formulate rules of engagement. However, such communication needs to be two-way, as Grunig and Grunig (1992) state, for all parties to have equal opportunities of addressing one another and formulating strategies that will benefit all of them. This should take place through a participative process, which allows citizens to identify and prioritise their needs, interests and expectations - which, as a result, should be addressed through community communication as a strategic process.

The purpose of this study is to explore the contribution of strategic communication in facilitating and fostering inclusive citizenry engagement within the provincial sphere of government through adequate and dialogic public participation platforms. The provincial sphere of government, especially in South Africa, has a mandate to establish legitimate and genuine citizenry needs, interests and expectations with the aim of creating favourable conditions through governance initiatives and sustainability programmes for an engaged society (enabled through community communication and two-way participation). Moreover, ordinary citizens often play an essential role in government processes, whether directly or indirectly. In South Africa, this role is particularly important within the provincial government sphere, which is delegated by the national government to foster inclusive and collaborative opportunities with those governed at grassroots level, among others. Conversely, communities will, at most, participate in development programmes if there are perceived benefits for them; however, such benefits should practically address the immediate needs and interests of citizens for inclusivity to be recognised.

Contextual to this study, the concept of inclusive citizenry engagement is thus introduced to emphasise a dynamic, interactional and transformative process of dialogue between people, groups, and institutions, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, an opportunity that enables people, individually and collectively, to realise their full potential and be engaged in their own welfare. The concept further depends on shared governance initiatives and citizenry-based sustainability programmes to enable meaningful participation via the bottom-up approach (community communication and participation). In this regard, Allen (2016) posits that strategic communication orients people's consciousness by inviting them to take a particular perspective, by evoking certain values and not others, and by creating referents for their attention and understanding.

LITERATURE REVIEW

It is widely argued that the developmental discourse underwent a critical review since the 1970s, shifting more towards a participatory approach in communication practice. In this respect, development communication recognises the need for the participation of stakeholders in developmental projects. Scholars such as Waisbord (2014) have observed that few contemporary development projects are operated without a component of a participatory model (c.f. Servaes 2014; Srampickal 2006; Barranquero 2011; Huesca 2002). Fundamentally, participatory communication is seen as an approach that utilises appropriate communication mechanisms and techniques with the objective of increasing the levels of participation by stakeholders in development projects (including information sharing, motivating and training, particularly at the grassroots level) (Oliveira 1993). Therefore, it can be argued that the participatory communication approach in the context of this study embeds the will of citizens and government to seek inclusivity in programmes and projects. Advocates of the participatory approach often argue that no development can exist without communication, and particularly, communication practised as a strategic orientation (Mat Tazin & Yaakop 2018; Waisbord 2014; Servaes & Malikhao 2012; Waisbord 2008). On the other hand, Sebola (2017) maintains that people and access to information about public participation opportunities and process is not as easy as it sounds in a governmental context. This is because terms such as "public", "involvement" and "participation" are often used as buzz words for democracy through participation -it becomes difficult to articulate the extent to which genuine and adequate citizenry participation is fostered in the provincial sphere of government. Slotterback and Crosby (2012) have also argued that although many governments recognise public participation as a cornerstone for participative governance, they do not have a good understanding of designing processes that will achieve desirable outcomes.

Strategic communication from a participatory perspective

The link between strategic communication and participatory communication is captured conceptually by Lie and Servaes (2015). These authors argue that strategic communication in the field of development communication is often applied in the thematic sub-discipline of health communication, but is not restricted to this sub-discipline. Waisbord (2014) attempts to herald the significant contribution of strategic communication for social change by suggesting that the field supports collective actions - collective communication actions require strategic choices in a participatory environment. These perspectives link the strategic component of communication to communication for development and social change (CDSC). Moreover, communication, whether participatory or strategic, should deal with coordinated organisational planning and should manifest a dialogic nature with a strategic and intentional goal. For this reason, participatory communication is considered strategic and intentional because participatory projects and programmes require some form of planning, objectives, coordination and implementation. Accordingly, such participatory projects and programmes in the main must be communicated effectively with the people, and they are often constituted for social change (c.f. Lewis 2011; Mahoney 2012; Paul 2011).

If communication is not coordinated nor articulated as a sustainable and strategic means, the public apathy that could result from this could be attributed to a lack of knowledge and understanding on the part of citizens about how their needs, interests and expectations are being addressed, particularly in government. Rensburg and De Beer (2011: 152) postulate that sustainability involves the organisation's assessment and improvement of its economic, environmental and social impact to align it with stakeholder requirements using, among others, integrated reporting. This is further witnessed through participatory communication as linked to the strategic management of communication (Waisbord 2014) - where participatory communication also advocates for a stakeholder perspective in development initiatives upon which the needs and interests of stakeholders depend.

Conversely, a better appreciation and acknowledgement of citizens' involvement could help the government develop strategies to improve communication and to access target groups (Singh 2014). It could be assumed from a participatory communication perspective that governance mechanisms and sustainability programmes are often not interpreted and practically translated to inform citizens about how their needs, interests and expectations are being addressed. Consequently, little positive change takes place in the attitudes and behaviour of citizens to improve their lives. It is based on the foregoing that this study measures the strategic role of communication in, among others, influencing participatory endeavours to attain social change through shared initiatives with a view to enable high levels of inclusive citizenry engagement opportunities.

Another link between strategic communication and participatory communication can be observed from top-down diffusion versus bottom-up participation approaches. In this regard, strategic communication efforts will not succeed if bottom-up participation approaches are neglected and the focus is only on top-down diffusion. Arguably, it is believed that citizens intensify their role and contribute wherever there are perceived benefits. It is thus imperative for sustainability programmes to be responsive to the expectations of citizens for continuous public participation, and for communication to be organised systematically to bring about the desired positive outcomes. As a context to strategic communication, it is, therefore, suggested by some scholars that what sounds easy and straightforward is one of the key problems of strategic communication and management. In this regard, more scholars specialising in the strategic management of communication question the ability of actors to act rationally in a contingent environment (Frost & Michelsen 2017; Okigbo & Onoja 2017; Lock et al. 2020; Singh 2014; Haywood & Besley 2014; Balogun 2006; Holtzhausen 2002).

Mitigating citizenry interests and expectations

Rensburg and De Beer (2011: 152-153) indicate that the role of communication in information dissemination and conversation in organisations is changing in a triple-context (people, planet and profit) environment. In essence, engaging stakeholders in decision-making processes, according to the "stakeholder-inclusive approach to governance", has become important globally, but particularly in South Africa with the publication of the King IV Report. In the main, following the traditional approach to integrated communication will not be sufficient in a new organisational context where governance and sustainability issues have become important in organisational decision-making. As a consequence, inclusive citizenry engagement should be considered as a people-oriented approach in the facilitation of dialogue, debates and mutual discussions with the actors and citizens concerned.

The notion of inclusive citizenry engagement can further be advanced through self-regulation mechanisms, whereby citizens advance regulatory measures of interactions, engagements and mutual relationships through a particular social cognitive framework (Morris 2003). The regulatory framework in this regard should allow citizens to govern their ability to become active and responsive stakeholders within a given society. This assertion of self-regulation is further supported through the theory of self-regulation. The theory presupposes that a self-regulating person controls and manages their reactions and behaviour to achieve goals despite changing conditions and priorities. Consequently, when implementing sustainability programmes it can be considered that participatory radio, imbizos and community-based centres form part of government activities with the view to engage community members actively in the planning, implementation and assessment of strategic programmes. Accordingly, a key distinguishing aspect of participatory approaches is a stronger focus on the process rather than on a specific communication product, as elaborated by Morris (2003), Waisbord (2014), and Lie and Servaes (2015). From these perspectives, governance initiatives and sustainability programmes must be goal-orientated and conform to the expectations of citizens, while addressing their identified needs and interests through projects designed to encourage public participation and inclusivity.

For inclusivity to be realised, one of the fundamental tools of the strategic management of communication is the ability to utilise resources significantly in positioning the needs and interests of stakeholders (in this case, citizens) at the forefront. In doing so, organisations are able to manage strategic relationships together with citizens' expectations for social change and cohesion (Waisbord 2014). Likewise, this can further be achieved when complete, timely, relevant, accurate, honest and accessible information is provided by the organisation to its stakeholders, whilst having regard for legal and strategic considerations.

The inclusive citizenry engagement concept highlights the importance of opportunity creation and challenges the existing ones through consensus building, which becomes imperative to societal objectives. The basic assumption would be that inclusive citizenry engagement can promote equal opportunities between the government and the governed and can use strategic relationship management to bring legitimacy to democratic values. Arguably, the concept of inclusive citizenry engagement can be attained through strategic thinking that is aligned with strategic planning and co-governance among the provincial government and its citizens. Notably, Heide et al. (2018) further allude to the fact that the fundamental idea of strategic communication is thus inclusive.

Moreover, legitimacy theory is identified as essential and complementary in advancing the strategic intent of a participatory endeavour. Legitimacy theory, in this respect, purposely connects well with strategic communication and the participatory communication perspective, to understand the legitimacy of the provincial government's communication goals in addressing citizenry needs, interests and expectations. Citizens are viewed as an integral part of the government's environmental component to exercise legitimacy. Arguably, societal values and legitimacy are intrinsically dependent on how governance initiatives and sustainability programmes are practically translated to respond to the communication challenges of citizens.

For legitimacy to materialise practically, the North-West Province, as the research context, has to consider social norms and bounds. As such, citizens remain an integral societal authority who refute or affirm government's legitimacy to operate. These theoretical presuppositions are the guiding lens to better understand and comprehensively assess how strategic communication, among others, can support governance initiatives and sustainability programmes in the process of striving for inclusive citizenry engagement opportunities. This is done with the sole aim of positioning strategic communication as a beacon of hope or deliberate tool to obtain inclusive citizenry engagement while adopting a participatory perspective. Therefore, this study poses the following questions to understand the role of strategic communication in facilitating and fostering inclusive citizenry engagement within the provincial sphere of government:

RQ1: How can strategic communication management for governance initiatives support inclusive citizenry engagement?

RQ2: How can strategic communication management for sustainability programmes support inclusive citizenry engagement?

METHODOLOGICAL ORIENTATION

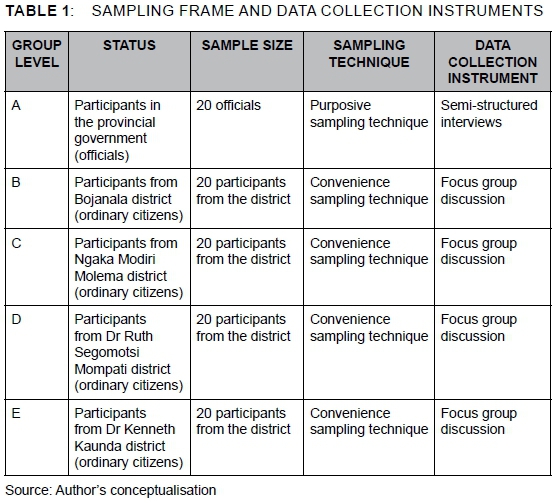

This study is exploratory in nature, which is the best way to understand participants' experiences and knowledge of the phenomenon under investigation and to develop the necessary background for future investigations on this topic. For this reason, a qualitative approach is deemed necessary. The research population comprised citizens from the North-West Province across four districts, namely Bojanala, Ngaka Modiri Molema, Dr Kenneth Kaunda and Dr Ruth Segomotsi Mompati.

Purposive and non-probability sampling techniques were adopted - purposive sampling was used to draw a sample from the provincial government officials, while non-probability sampling was used to extract a sample from ordinary citizens across the four districts. The reason for using purposive sampling was that there was a need for deeper insights obtained from qualitative data collected through semi-structured interviews from a portion of the population. These participants were purposively selected on the basis that they could provide key information for the study and they are in positions of power or authority to initiate, conduct and evaluate engagement opportunities with citizens. To this end, convenience non-probability sampling was done on a spontaneous basis to take advantage of available participants without the statistical complexity of a probability sample - this approach was ideal for diverse ordinary citizens of the North-West Province across the four regions.

Data management and analysis

To yield data for the qualitative investigation, different measuring instruments were employed. Data analysis was viewed as the process of making sense of the data by consolidating, reducing and interpreting what the participants said and what the researchers observed and read. Both the traditional analysis method (manual process) and computer software (NVivo 11 plus) were adopted and synchronized to provide a complementary approach to data management, interpretation and presentation. The raw data collected through the semi-structured interviews and focus group interviews were transcribed; and the topics were coded and classified, the categories developed, and the patterns sought in accordance with Braun and Clarke's (2006) perspective of thematic analysis.

RESULTS AND INTERPRETATION

The study was undertaken with the intention of presenting the experiences, perceptions and knowledge of the participants on the topic of strategic communication management suitable to deliver inclusive citizenry engagement at the provincial government level. To achieve this intention and strategic focus, various methods and techniques were adopted in order to collect the necessary data from the research participants. After gathering the raw data, complementary techniques were adopted to engage with and understand the collected data.

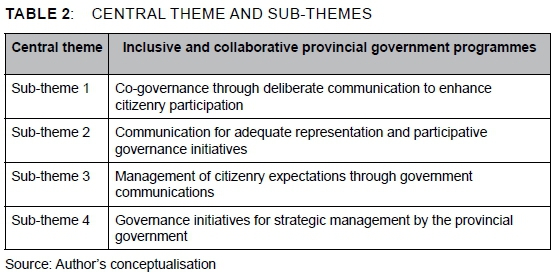

Central theme: Inclusive and collaborative provincial government programmes

Inclusive and collaborative provincial government programmes is the overarching central theme that encapsulates government responsiveness to the challenges and opportunities concerning the welfare of citizens. Under this central theme, the participants advanced numerous perspectives and connotations to explain their experiences and knowledge of the phenomena of interest to the current study. The majority of the participants were of the view that some of provincial government programmes had an impact on their living conditions and, as such, propelled a particular desire and expectation to be fulfilled. However, the participants also indicated that most of their expectations in relation to the significance and flexibility of the programmes left much to be desired. It became clear that not all identified programmes and activities encouraged inclusivity because the role and involvement of citizens in the planning and implementation of government programmes was deemed unsatisfactory and often minimal. The participants further opined that the majority of the provincial government programmes were imposed on citizens, rather than negotiated and discussed for consensus and mutual collaboration. The participants also alluded that communication about the programmes benefited selected individuals and communities closer to the provincial government headquarters, and consequently, isolated those in secluded areas of the province.

All I can say is that, rona (we) in secluded areas of the province are isolated primarily because of inadequate information shared as a provision to influence our attitude towards the offerings of government.

Another challenge associated with deficiency of inclusivity was the fact that collaborative participation among the provincial government and ordinary citizens remained restricted. Five of the participants contended that the relationship was also unhealthy, as the viewpoints and suggestions often offered by citizens were not incorporated into the broader strategic plan of the provincial government. Moreover, political patronage appeared to be extended to politicians and other affiliated parties to gain and maintain political mileage instead of inclusive representation. This practice was cited as an element of maintaining political power, whilst entrenching selective hegemony in government activities. Likewise, two other participants stated that the development agenda and future direction of the province was influenced and decided without the consent and input of the majority of the citizens. Hence, participants postulated that community unrests and dissatisfaction were at times premised on the inability of the provincial government to prioritise the legitimate demands of citizens, as well as to address their expectations adequately. The participants referred to several other challenges that contributed enormously to the ineffectiveness of government to inculcate a responsive and an inclusive culture:

Communication campaigns and efforts dedicated to encourage citizenry inclusivity remained less effective as some citizens resembled high levels of apathy towards initiated government activities.

Identified provincial government programmes for citizens were viewed as abstract and less practical to effect a degree of change either in attitude or behaviour.

Messaging and planning had no durable effect and essentially are not tailored to resemble communicative action on the part of citizens.

Governance initiatives and sustainability (developmental) programmes were not citizenry-oriented; thus, citizens often struggled to recognise inclusivity and co-governance in most government operations.

From the aforementioned, it is evident that participants held wide-ranging perceptions of what their relationship with the provincial government suggests. The majority of the views expressed indicated a negative impact on the provincial government's activities to engage with citizens. Inadequate information and ineffective communication processes were often referred to as part of the challenges embedded in understanding the provision of various programmes. This hindered a healthier and dialogic relationship among citizens and their provincial government.

In terms of Research Question 1, namely How can strategic communication management for governance initiatives support inclusive citizenry engagement?, the North-West provincial government is involved in various governance initiatives aimed at promoting various mechanisms to provide services, information, education and favourable opportunities to its constituencies. In providing these opportunities, the provincial government needs to communicate more consistently and regularly through the media. This assertion emphasises the fact that the communication of information has to be strategically managed for each audience to receive such communication in as efficient, effective and acceptable manner as possible - there is no "one-size fits all" situational expectation.

Furthermore, a commitment to strategic communication champions collective engagement - through constructively transparent discourse all parties form shared values in society. Scherer and Palazzo (2011) assert that democratic deliberation requires open discourse, transparency, participation and accountability by all actors, as stated in Habermassian political theory. These demands challenge management (in this case, senior provincial government officials) to use communication as a vehicle for promoting good in society (Heath et al. 2013). In support of this view, the first and most basic purpose of provincial government officials and community/public representatives is to improve citizens' knowledge of government activities and operations. Arguably, a knowledgeable citizenry is a consciously informed and active participant - this participation often leads to high levels of dialogue and public engagements in respect of an inclusive and thriving society.

Sub-theme 1: Co-governance through deliberate communication to enhance citizenry participation

It is widely argued that increased community consultation and public participation in government decision-making produce many important benefits. Through this process, deliberate communication is shared and interpreted among parties to produce favourable outcomes. In this regard, consensus is maintained on a consistent basis, and public participation becomes a prerequisite for co-governance initiatives and the overarching strategic plan of the provincial government. Co-governance through deliberate communication as a priority to enhance citizenry participation was an indirect theme in the comments of several participants, focusing on how purposeful communication can stimulate legitimate interests in advocating for people-centred governance initiatives. Some of the participants believed that the espoused communication programmes inadequately pursued sufficient citizenry participation. It came to the fore that the channels and techniques adopted to enhance citizenry participation were not optimal in embracing a highly engaged and active citizenry -public apathy remained the primary challenge in leveraging citizenry participation to produce co-governance and an informed citizenry, as the participants articulated.

A number of the participants mentioned that sufficient time and effort were not invested in understanding the main concerns advocated by communities. They further held that bureaucratic constraints on the part of the provincial government impaired every opportunity to communicate effectively. In addition, four of the participants were of the view that restrained communicative programmes are often a manifestation of poorly planned and managed communication objectives, and, as such, failed to incorporate the "choices and inputs" of ordinary citizens into the dominant coalition of governance initiatives:

They don't listen to our views; in meetings or any other platform, it is about what they propose not what we want.

As the participants further postulated, the realisation of inclusive citizenry participation in shaping and contributing to the development of policies, influencing governance decisions, and mutually reaching solutions to problems associated with communication was observed as an implausible objective. Consequently, communication messages and campaigns were viewed as a mere formality, elements of a publicity stunt at times, and most importantly, a process of informing communities about different imposed government initiatives, as the participants confirmed.

Eight of the participants stated that sufficient opportunities were provided to encourage public dialogue and balanced participation as a vehicle to achieve common goals. In essence, communication channels were selected, sensibly and purposefully, to address the intentions of the provincial government, as the participants suggested. Furthermore, it was argued that government programmes, to some degree, empowered citizens to seek more information and productively engage in achieving social, economic and environmental benefits for a sustainable future.

In terms of Research Question 2, namely How can strategic communication management for sustainability programmes support inclusive citizenry engagement?, strategic communication efforts and programmes have the potential to yield positive and continuous benefits for citizens as the governed and for the provincial government as the governor. Through strategic communication, the two-way communicative relationship between citizens and the government is the manifestation of a dialogic communication approach. In this context, strategic communication programmes should be leveraged by the aspirations of ordinary citizens via the horizontal approach to communication between the provincial government management and their external stakeholders to ensure that the vertical approach to communication between the same management and their officials adequately influence and reflect the views of the majority of the citizens. Moreover, direct community engagement is to be used as an umbrella idiom by the North-West Province to include information, consultation, engagement and empowering activities. To this end, the provincial government must recognise that citizens seek more direct ways to become involved in public life and decision-making, particularly on issues in which they have a direct interest. Strategic communication is, therefore, a core element of the provincial government - an effective tool to facilitate decision-making, and a way to reach decisions with which the communities feel satisfied. This process ensures that adequate opportunities are established to involve communities in the governance process.

Strategic communication is advanced and facilitated at provincial government level to communicate effectively 'with' citizens the benefits of and their responsibility towards government sustainability programmes. According to Thompson et al. (2013), the use of the word 'strategic' is a game changer. Its appearance in 'strategic communication' shifts the focus from context and the recipient to purpose and the sender. Strategy does not privilege any one quality of the communication exchange; rather, it focuses on achieving the sender's predetermined aim (Lock et al. 2016).

Sub-theme 2: Communication for adequate representation and participative governance initiatives

Communication is often negatively cited as a barrier in crisis circumstances that institutions, such as government departments and other private organisations, have to contend with. However, the same communication is never credited with producing economic benefits, whilst also influencing strategic decisions and shared goals. The positive contributions of certain communication programmes and campaigns to the success of organisational objectives are often overlooked and mostly neglected. The participants advanced that communication efforts aimed at constructing an inclusive and integrative society were not successful in adequately representing the immediate needs and interests of ordinary citizens. Moreover, targeted communication campaigns were also not successful in advocating for citizenry-oriented developmental programmes and governance initiatives to influence policies, advance ethical leadership, and contribute to the provincial government's overall rebranding, repositioning and renewal strategy. Consequently, a number of participants asserted:

With us the development of communication messages to influence and encourage a wider societal representation in governance reforms lacked a participative component; thus, participation is only limited to a few 'politically sponsored' individuals and groupings - not everyone.

In this sense, a participative component implied the incapacity of communication programmes to resemble collaborative measures for the parties involved to work towards accomplishing negotiated goals through consensus. The participants further expounded:

Mutual collaborations based on legitimate agreements as a participative component did not guarantee a smooth flow of meaningful two-way discussions among us.

In this regard, the consensual participative process would ensure that information was not restricted or limited to benefit individual interests; and the participants were more concerned with ensuring that the process was successful and that it contributed to capacitating community members at large. Fundamental to the realisation of adequate representation in governance initiatives and other extended government activities is the competence and the strategic focus of communicators to disseminate tailored messages comprehensively to the targeted audience. The participants thus argued:

Some government officials, as the carriers of information, lack basic skills to effectively educate us (citizens) on the advantages and benefits of several programmes.

That is why we don't generally participate - it's not meant for us.

They (officials) don't know what to say to us - they only talk to us when it suits them; to me this is wrong.

It remained unclear how citizens were expected to contribute and influence governance initiatives, especially because communicators were viewed as incompetent in transmitting strategic messages for the benefit of ordinary citizens. Some participants remarked that in many instances government communicators inspired no confidence when communicating the vision and future prospects of the government. A sense of professionalism in articulating and addressing citizenry expectations was a missing ingredient in achieving participative governance in the province. It is thus crucial that communicators be sensitised to the importance of empowering citizens with information on the services to which they are entitled and that they be guided on how to reap the potential benefits associated with such.

Sub-theme 3: Management of citizenry expectations through government communication

The organisation of citizenry expectations cannot be over-emphasised in government communication. The result of the successful management of expectations can lead to consensus, a shared vision, representation, and efficient service delivery efforts. Hence, citizenry expectations should be elevated into the dominant coalition and be integrated in the strategic framework through strategic communication programmes. A number of the participants held that provincial government communication had the capacity to facilitate social change, convert abstract programmes into pragmatic ones, and to act as a capacity-building instrument aimed at balanced relationships to the benefit of all actors involved, particularly citizens. Subsequently, some of the participants asserted that government communication, at times, advanced an inclusive agenda, seemingly aimed at coaching and promoting independence and strategic thinking from citizens across the province.

Nna (me), I see the government doing well - it's us citizens who don't do our part, especially in clearly identifying what we want.

In this light, the majority of the participants stated that it is at the provincial level that a people-centred approach to sustainable government communication could become truly evident. At this level, decisions are taken daily by individuals and groups of people that affect their livelihoods, health, and often their form of survival. From this perspective, strategic communication should be both a 'centre of government' concern (i.e. an organic and critical part of the policy-making and strategic process at the highest levels) and a tool to unite the whole of government (i.e. a common feature of all activity at all levels of government). The participants further articulated that only refined and purposeful communication could attempt to consolidate citizenry expectations and the perceptions of government activities. They maintained that such communication had to be results-oriented and research-based in order to reconcile conflictual expectations and interests. Provincial government communication and the media have to be regarded as primary instruments to achieve, maintain and strengthen public participation. However, it also emerged that provincial government communication has been conceived as a one-way process passing messages from one point to many others, usually in a vertical, top-down fashion.

We never say anything, or I can simply say that we don't get feedback - there are no follow-ups and opportunities to hear how far are we.

Effective engagement with citizens depends largely on their understanding of the goal and acceptance that involvement in the communication strategy process demands changes in attitudes, behaviour and institutions. Therefore, developing a comprehensive strategy demands two-way communication between policy-makers and the public. This requires much more than government relations initiatives through information campaigns and the media. It needs commitment to long-term social interaction to achieve a shared understanding of sustainable objectives and its implications, and promoting capacity building to find solutions to the challenges. In this sense, the participants strongly believed that being strategic was about setting goals and identifying the means of achieving them - this remained the outstanding ingredient in government operations because of the isolation of citizens, to some degree.

Sub-theme 4: Governance initiatives for strategic management by the provincial government

It is important to consider the fact that the existence of the provincial government is largely based on the dictates of the South African Constitution and subsequently, the number of votes earned from the political party system (the electorate). It is thus through various political parties that a particular government is arranged, meaning that the victorious political organisation constitutes a governance structure to serve the people. Hence, people are governed by the government, irrespective of their initial choice.

Against this backdrop, the provincial government assumes the responsibility and mandate from both their political organisation and society as a whole - the latter, more often than not, becomes more dominant in its operations. Consequently, governance initiatives are often derived and established based on political organisations' adopted policies, mandate and, most importantly, their standing resolutions (from congresses/conferences). From this perspective, it was evident from the participants that governance initiatives were influenced and developed in accordance with the policies and resolutions of political organisation(s). Interestingly, these policies were often implemented together with citizens, as they were meant for them. This narrative implies that the influence and involvement of citizens in general is minimal, unless in circumstances were civil society, NGOs and other activists embark on policy amendments, new policy propositions, and so forth. However, a couple of the participants commented that ordinary citizens were consulted via political organisations and that the mandate carried was a manifestation of community engagement. In addition, one of the participants strongly registered:

At the provincial government level, sufficient opportunities are created to integrate the views of citizens into policy formulation, programmes and decision-making processes - according to me, we are at least consulted.

Another participant advanced that the policies and all other governance-related issues emanated from community meetings, public consultations and special forums aimed at gathering the views of prominent figures in society.

I believe that all of these opportunities included ordinary people at the helm of strategic governance processes.

Arguably, this view seemingly contradicted the latter assertion, whereby standing organisational (political) resolutions formed the basis of the provincial government mandate. Accordingly, the majority of the participants articulated that ordinary citizens in their capacity remained a strategic unit for advancing government programmes through agreed strategies. In this case, the provincial government in collaboration with the people and various community representatives had a responsibility of ensuring that governance initiatives are successfully implemented. The collaboration process with all active participants is therefore viewed as a component of strategic management. Furthermore, several participants asserted that the ability of the provincial government to facilitate dialogue, produce people-centred programmes, promote and address legitimate citizenry expectations, and advance partnerships was a key indicator of effective leadership and strategic management in action.

DISCUSSION

The presentation of the research results sought to ascertain how the phenomenon of strategic communication management was understood as a strategic process with the capacity to elevate participatory projects/programmes in the North-West Province. The research also aimed to determine how the realisation of strategic communication management efforts often encouraged and promoted inclusive citizenry engagement through collaborative governance initiatives and people-centred programmes. In short, the research results demonstrate how the research participants related to the phenomena of strategic communication management and ultimately the process of communication management at the provincial government level.

The findings reveal that a significant majority of citizens remain disengaged from government operations. A number of reasons were advanced by the participants -they postulated that communication had no durable effect because the government was unable to fulfil their expectations. In most instances, provincial government programmes were not aimed at increasing inclusivity because public representatives extended patronage to their political principals. In light of these assertions, the planning and execution of governance initiatives and the exercise of strategic management often excluded the aspirations of the majority. Similarly, those in secluded areas of the province were cited as being more disadvantaged and extremely passive on government operations. In this case, communication with citizens was only concerned with information transfer and remained one-sided, one-way communication at best. As a result, both citizenry passivity and public apathy continued to characterise the failure of government initiatives in reaching and positively influencing collaborative governance measures, particularly in rural communities.

Liu and Horsley (2010) advocate that a democratic government is best served by a free two-way flow of ideas and accurate information so that citizens and their government can make informed choices. A democratic government must report and be accountable to the citizenry it serves. Citizens, as taxpayers, must have the right to access government information.

However, in this study it was recorded that in many instances government activities were unresponsive and offered less opportunities for citizens to contribute actively to the development of the province. Essentially, it was advanced that political patronage and the inability of some public representatives as hemispheric communicators to initiate unrestricted two-way communication with citizens were among the main factors leading to high levels of disengagement and continued apathy. Public representatives were also referenced as being incompetent in articulating the aspirations of citizens to senior officials and vice versa. In this context, public representatives were viewed as not strategic in advancing government programmes and communication campaigns, and coordinating citizenry engagements at the community level.

Similarly, some public representatives had no significant bearing on the living conditions of citizens. It was further argued that public representatives were not equipped and skilled to manage community communication programmes. At this level, communication had no durable impact because citizens were unable to influence government activities and thus opted to remain passive and apathetic towards even genuine projects. In a sense, participatory communication as a two-way process was also neglected simply because citizens failed to realise the participative nature of various projects/programmes. The participants further mentioned that media invitations were often extended as 'a publicity stunt' and not as an authentic media relations process. Community events and programmes were publicised to gain political mileage and relevance within communities because, under normal circumstances, media houses/outlets were often excluded amid the fear that community members would advance their challenges/grievances, which would be published.

It is for these reasons that a number of citizens recorded that government communication programmes and governance initiatives were not integrative; failed to respond to genuine concerns at the community level; and were often characterised by political patronage and gate keeping. Pertinently, Chaka (2014) argued that government communication could be more symmetrical than was generally accepted. Arguably, clear and precise communication leads to accountability and transparency. In dialogue between the government, local authorities and stakeholders (all citizens), the more information that is shared, the more participation and dialogue are encouraged, the more accountable those in power become, and the more transparent their actions must be. As a context, citizens must receive, through various channels of communication, not only the messages of the provincial government and the invitation to engage in dialogue, but also the underlying message that their participation is essential to the process. The outcome of any community activity should be perceived by the population as the result of a provincial effort in promoting a responsive government and inclusive environment for ordinary citizens to be empowered through strategic communication as an enabler for good governance.

It is implicit that, for communication to be construed as strategic, it has to be the result of a planned process, and in this context, citizenry engagement will be a product of public collaboration and an inclusive process (Macnamara 2016). The concept of communication is often viewed simplistically as a process of information dissemination, rather than a strategic process. Accordingly, efforts to engage with citizens are often decided and agreed to without involving the supposed recipients - ordinary citizens. Van der Waldt et al. (in Singh 2014) maintain that if the community is not informed in relation to government actions, it cannot evaluate them in terms of ethics and morality. Such access to information by citizens is enshrined in the Constitution of South Africa. More often than not, communication policies and guidelines exist to ensure that the highest standards of fairness, equity, probity and public responsibility are front of mind when planning any type of government communication. Provincial government communication needs to be effective, co-ordinated, well managed, and responsive to the aspirations of the North-West communities. Grunig and Grunig's (1992) two-way symmetrical model suggests that communication fosters the relationship between an organisation, and in this instance the government, and its publics, based on negotiation, trust and mutual respect - a collaborative strategic relationship must therefore be forged for it to function effectively and efficiently. Provincial government programmes would be more effective if a strategic communication approach is to be adopted and focused on establishing and managing relationships, increasing participation, and encouraging co-operation between the government and its people - thus, enabling the co-creation of shared norms and an inclusive people-orientated communicative environment.

The study moves that inclusive citizenry engagement could only be achieved through collaborative participation mechanisms among the provincial government officials and citizens at the helm. Importantly, a participatory philosophy should be adopted in order to elevate the role and value of citizens in society, as they facilitate ways for the provincial government to be more responsive to public needs. The bottom-up (as an outflow of the horizontal) approach should be more active in consolidating the identified citizenry needs, interests and expectations to ensure effective co-ordination, particularly at community communication level. Haywood and Besley (2014) contend that the most deliberative engagement processes do not guarantee that participation will increase the relevancy and responsiveness of government for individual participants, or the efficacy of subsequent policy implications that may emerge from such efforts. The ability to constitute sustainable citizenry engagement platforms depends largely on the provincial government to increase and expose citizens to relevant opportunities in a responsive manner. As a result, the narrative should move from identifying stakeholders as mere "publics" to them acting as active citizens in the participatory process. Holmes (2011) articulates that over the past decade, this view has been reframed to regard the public as citizens whose agency matters and whose right to participate directly or indirectly in decisions that affect them should be actively facilitated. Such an approach honours the fundamental principles of an inclusive and democratic process, which power is to be exercised through, and which resides in its citizens.

CONCLUSION

This study was preoccupied with reporting the significant benefits of practising strategic communication at provincial government level in order to attain and maintain inclusive citizenry engagement. From this resolve, the study indicated that strategic communication management needs to be reprioritised as a deliberate effort towards participative governance and shared goals. To this end, a revolutionary approach to government communication has to be reconfigured adequately to resemble inclusive citizenry engagement through organised public participation opportunities. Moreover, efforts should be directed at the realisation of strategic communication management in order to leverage mutual governance initiatives and people-centred sustainability programmes. This process has the potential to engage citizens intentionally, purposefully, and towards a desire for an impactful society. Such a society will be empowered, through strategic communication management, to strive for co-governance and inclusivity in government activities. Fundamentally, skilled public representative professionals must develop communication strategies that will improve and build trust, encourage public participation, and contribute to mutual decision-making and accountability in an efficient manner - this arguably is why participation matters, as it encourages mutual understanding and ownership of shared perspectives through co-creation by dismembering unrealistic and often illegitimate participatory endeavours. It is for these reasons that a new approach to communication needs to be adopted to facilitate engagements with ordinary citizens on an inclusive, dialogic and more comfortable level. In striving for inclusive citizenry engagement, strategic communication management in the provincial government should become an epitomised process, which is interactive by nature and participatory at all levels in this sphere of government.

REFERENCES

Allen, M.W. 2016. Strategic communication for sustainable organisation. Switzerland: Springer, Cham. [ Links ]

Balogun, J. 2006. Managing change: Steering a course between intended strategies and unanticipated outcomes. Long Range Planning 39(1): 29-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2005.02.010 [ Links ]

Barranquero, A. 2011. Rediscovering the Latin American roots of participatory communication for social change. London: University of Westminster. https://doi.org/10.16997/wpcc.179 [ Links ]

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Chaka, M. 2014. Public relations (PR) in nation-building: An exploration of the South African presidential discourse. Public Relations Review 40: 351-362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2013.11.013 [ Links ]

Frost, M. & Michelsen, N. 2017. Strategic communications in international relations: practical traps and ethical puzzles. The official journal of the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence 2: 9-34. https://doi.org/10.30966/2018.riga.2.1 [ Links ]

Grunig, J.E. & Grunig, L.A. 1992. Models of public relations and communication. In: Grunig, J.E. (ed.) Excellence in public relations and communication management. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Haywood, B.K. & Besley, J. 2014. Education, outreach, and inclusive engagement: Towards integrated indicators of successful program outcomes in participatory science. Public Understanding of Science 23(1): 92-106. https://doi.org/1C1177/0963662513494560 [ Links ]

Heath, R., Waymer, D. & Palenchar, M. 2013. Is the universe of democracy, rhetoric and public relations whole cloth or three separate galaxies? Public Relations Review 39: 271-279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2013.07.017 [ Links ]

Heide, M., Von Platen, S., Simonsson, C. & Falkheimer, J. 2018. Expanding the scope of strategic communication towards a holistic understanding of organisational complexity. International Journal of Strategic Communication 12(4): 452-468. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1456434 [ Links ]

Holmes, B. 2011. Citizens' engagement in policymaking and the design of public services. Research paper No. 1, 2011-2012. [ Links ]

Holtzhausen, D. 2002. Towards a postmodern research agenda for public relations. Public Relations Review 28(3): 251-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0363-8111(02)00131-5 [ Links ]

Huesca, R. 2002. Tracing the history of participatory communication approaches to development: A critical appraisal. In: Servaes, J. (ed.). Approaches to development communication. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Ihlen, 0., Verhoeven, P. & Frederiksson, M. 2018. Conclusions on the compass, context, concepts, concerns and empirical avenues of public relations. In: Ihlen, 0. & Frederiksson, M. (eds). Public relations and social theory: Key figures, concepts and developments. (Second edition). New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315271231-22 [ Links ]

Lewis, L.K. 2011. Organisational change: Creating change through strategic communication. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444340372 [ Links ]

Lie, R. & Servaes, J. 2015. Disciplines in the field of communication for development and social change. Communication Theory 25: 244-258. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12065 [ Links ]

Liu, B.F. & Horsley, J.S. 2010. Government and corporate communication practices. Do the difference matter? Journal of Applied Communication Research 38(3): 189-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909881003639528 [ Links ]

Lock, I., Seele, P. & Heath, R.L. 2016. Where grass has no roots: The concept of 'shared strategic communication' as an answer to unethical AstroTurf lobbying. International Journal of Strategic Communication 10(2): 87-100. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2015.1116002 [ Links ]

Lock, I., Wonneberger, A., Verhoeven, P. & Hellsten, L. 2020. Back to the roots? The applications of communication science theories in strategic communication research. International Journal of Strategic Communication 14(1): 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2019.1666398 [ Links ]

Lues, L. 2014. Citizen participation as a contributor to sustainable democracy in South Africa. International Review of Administrative Sciences 80(4): 689-807. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852314533450 [ Links ]

Macnamara, J. 2016. Illuminating and addressing two 'black holes' in public communication. Prism 13(1): 1-14. [ Links ]

Mahoney, J. 2012. Strategic communication: Principles and practice. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Mat Tazin, S.N. & Yaakop, S.H. 2018. Strategic communication in public participation. Journal of ASIAN Behavioural Studies 3(10): 162-169. https://doi.org/10.21834/jabs.v3i10.315 [ Links ]

Morris, N. 2003. A comparative analysis of the diffusion and participatory models in development communication. Communication Theory 13: 225-248. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/13.2.225 [ Links ]

Nothhaft, H. 2016. A framework for strategic communication research: A call for synthesis and consilience. International Journal of Strategic Communication 10(2): 69-86. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2015.1124277 [ Links ]

Nothhaft, H., Werder, K.P., Vercic, D. & Zerfass, A. 2018. Strategic communication: Reflections on an elusive concept. International Journal of Strategic Communication 12(4): 352-366. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1492412 [ Links ]

Okigbo, C. & Onoja, B. 2017. Strategic political communication in Africa. In: Olukotun, A. & Omotoso, S.A. (eds). Political communication in Africa. Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48631-4_5 [ Links ]

Oliveira, O. 1993. Brazilian soaps outshine Hollywood: Is cultural imperialism fading out? In: Nordenstreng, K. & Schiller, H. (eds). Beyond national sovereignty: International communication in the 1990s. Ablex. [ Links ]

Paul, C. 2011. Strategic communication: Origins, concepts and current debates. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. [ Links ]

Rensburg R. & De Beer, E. 2011. Stakeholder engagement: A crucial element in the governance of corporate reputation. Communitas 16: 151-169. [ Links ]

Scherer, A.G. & Palazzo, G. 2011. The new political role of business in a globalized world: A review of a new perspective on CSR and its implications for the firm, governance, and democracy. Journal of Management Studies 48: 899-931. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00950.x [ Links ]

Sebola, M. 2017. Communication in the South African public participation process: The effectiveness of communication tools. African Journal of Public Affairs 9(6): 25-35. [ Links ]

Servaes, J. (ed.). 2014. Technological determinism and social change: Communication in a tech-mad world. Lanham, MD: Lexington. [ Links ]

Servaes, J. & Malikhao, P. 2012. Advocacy communication for peace building. Development in practice 22(2): 229-243. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2012.640980 [ Links ]

Singh, B.P. 2014. Impact of strategic communication policy on service delivery and good governance within KwaZulu-Natal department of sport and recreation. Unpublished doctoral thesis: University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Slotterback, C.S. & Crosby, B.C. 2012. Designing public participation processes: Theory to practice. Public Administration Review 73(1): 23-34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02678.x [ Links ]

Srampickal, S.J. 2006. Development and participatory communication. Communication Research Trends 25(2): 3-32. [ Links ]

Thompson, A., Peteraf, M., Gamble, J. & Strickland, A. 2013. Crafting and executing strategy: The quest for competitive advantage (Nineteenth edition). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. [ Links ]

Waisbord, S. 2008. The institutional challenges of participatory communication in international aid. Social identities 14(4): 505-522. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630802212009 [ Links ]

Waisbord, S. 2014. The strategic politics of participatory communication. In: Wilkins, K.G., Tufte, T. & Obregon, R. (eds). The handbook of development communication and social change. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Zerfass, A., Vercic, D., Nothhaft, H. & Werder, K. 2018. Strategic communication: Defining the field and its contribution to research and practice. International Journal of Strategic Communication 12(4): 487-505. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1493485 [ Links ]

Date submitted: 01 May 2021

Date accepted: 03 November 2021

Date published: 31 December 2021