Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Communitas

versión On-line ISSN 2415-0525

versión impresa ISSN 1023-0556

Communitas (Bloemfontein. Online) vol.25 Bloemfontein 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150525/comm.v25.11

ARTICLES

Predictors of e-marketing adoption by Zimbabwean churches

Dr Patrick MupambwaI; Prof. Norman ChiliyaII

IMarketing Division, Commerce, Law and Management Faculty, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa Email: Pmupambwa@gmail.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4135-162x

IIDepartment of Business Management, Faculty of Management Sciences, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa Email: Norman.chiliya@univen.ac.za (corresponding author); ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1900-7248

ABSTRACT

Electronic marketing has transformed marketing practices. However, the acceptance of e-marketing applications and principles in churches has been moderate. This study examined the predictors of e-marketing adoption among Zimbabwean churches. The study was quantitative in nature, and a positivist orientation was adopted. Two hundred and fifty self-administered questionnaires were distributed to clergymen from various churches in Zimbabwe. Structural equation modelling using Smart PLS software was employed during the data analysis phase. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were manipulated in this study. The results indicate that marketing orientation, marketing innovation, church youth marketing, competitive intensity, and dynamic marketing capabilities have a significant influence on e-marketing orientation among Zimbabwean churches. Lastly, e-marketing orientation spurs an increase in religiosity and spirituality of church members.

Keywords: e-marketing; advertising; marketing communication; churches; faith-based organisations

INTRODUCTION

E-marketing is an emerging concept to many organisations, more so for charitable organisations such as churches operating in Africa, where internet accessibility is falling behind the Western world (Brodie et al. 2007; Brady et al. 2002). Although the use of e-marketing practices by religious organisations has been accelerating since 2000 (Barna Group 2009), many churches remain hesitant in adopting e-marketing (Anghelutä et al. 2009). A large corpus of academic literature on the adoption and the resultant impact of e-marketing in commercial businesses, both product and service-oriented, exists (Brady et al. 2002; Trainor et al. 2011; Tiago & Tiago 2012; Ivanov 2012). However, little research exists on religious e-marketing in an African context in general (Togarasei 2012). This study therefore sought to examine the predictors of e-marketing adoption amongst Zimbabwean churches.

LITERATURE REVIEW

While the purpose of a commercial organisation is to maximise wealth creation for shareholders, non-profit organisations focus on influencing and encouraging target audiences to give or donate for their cause or their philanthropic work (Sandilands 2014; Surbhi 2016). More than 50 years ago, Kotler and Levy (1969) emancipated the marketing concept from its restriction to the domain of physical goods, contending that marketing principles should not be restricted to offerings such as soap. It could be utilised to promote an assortment of causes, extending from political professions to philanthropies (Wright 2010). This led to the birth of health marketing, social marketing and church marketing, among others (Kotler 2005).

Churches normally depend on member contributions for their survival and do not get any funding from government or the private sector; they can be considered nonprofit organisations (Mulyanegara 2009; Kotler & Keller, 2016), as well as service organisations (Russell-Bennett et al. 2013; Lovelock & Wirtz 2016). Churches are therefore an interesting research context for investigating the determinants of electronic marketing orientation in a non-commercial and services industry.

The governmental, economic and social difficulties, destitution and social ills bedevilling Zimbabwe have been conducive for the bourgeoning of the Zimbabwean religious market (Biri 2013; Dodo et al. 2014). As suggested by Krause (2003), Stroope et al. (2013) and King et al. (2016), religion spurs individuals to seek meaning in life. In Zimbabwe, the multiplicity of churches has been growing in recent years, thereby creating a highly competitive church market. Theological reasons and quests for personal kingdoms are among the reasons that have been provided to explain the surge in the growth of churches. Christianity in Zimbabwe has become a "spiritual supermarket", with adherents now fast-tracking church shopping and switching (Moyo 2016), with e-marketing playing a pivotal role. It is, therefore, imperative to investigate the predictors of e-marketing orientation amongst the churches and the resultant impact.

As the competitive intensity grew in the religious market, religions and churches were turned into "brands" (Einstein 2008); this triggered the marketisation of religion and churches (Usunier & Stolz 2014). Like any commercial business operation, religious and church leaders face overwhelming challenges in their quest to attract and retain religious consumers (Appah & George 2018). Each religious brand is fighting for visibility, and the recognition and acquisition of its religious services (Nardella 2014). Einstein (2008) writes that the explosion of religious options, media fragmentation and immersion, and the omnipresence of marketing techniques has made it vital for religion to market its programmes and services as brands. Consequently, the application of marketing tools and practices has taken centre stage in church markets (Usunier & Stolz 2014).

Marketing tactics from commercial businesses are the building blocks from which an agenda for church marketing is found, subject to the non-desacralisation, de-Christianising and secularisation of religion, and the damage or pollution of the core concepts of spirituality and religiosity (Abreu 2006; Butler 2014). The lackadaisical attitude of some churches towards e-marketing practices is no longer sustainable (Arthur & Rensleigh 2015). Spiritual consumers are using electronic marketing platforms for information searching and sharing, to search for spiritual guidance, for entertainment, as a source of moral support, and for social interaction and relaxation (Fogenay 2013; Arthur & Rensleigh 2015).

As a result of an increasingly digitalised world, information sharing is largely restricted to an online environment; hence, the adoption of new practices by churches to fit this trend has become a necessity (Wielstra 2012; Han 2016). A such, the Vatican views the internet as a "gift from God" designed for evangelism; thus, the church must give the internet a "soul" (Garland 2014) and use it to spread the message of the gospel (Foley 2002).

Not much has been written about church e-marketing orientation in Zimbabwe. Consequently, church leaders and marketing practitioners are ill equipped and possess little, if any, knowledge to help them execute effective e-marketing strategies. Strategic church decisions are made based on individual intuition, or trial and error.

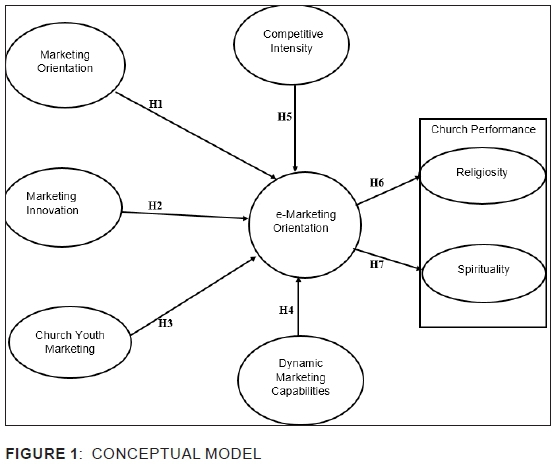

This study addresses this gap in literature and contributes to the understanding of the predictors of e-marketing usage and adoption, and how religions organisations can leverage e-marketing investments to achieve better results. The conceptual model and hypothesis in Figure 1 were developed.

The hypotheses are:

H1: There is a positive relationship between marketing orientation and e-marketing orientation.

H2: There is a positive relationship between marketing innovation orientation and e-marketing orientation.

H3: There is a positive relationship between a church's emphasis on attracting the youth to the church and e-marketing orientation.

H4: There is a positive relationship between competitive intensity and e-marketing orientation.

H5: There is a positive relationship between dynamic marketing capabilities and e-marketing orientation.

H6 There is a positive relationship between e-marketing orientation and religiosity. H7: There is a positive relationship between e-marketing orientation and spirituality.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

A descriptive research design was adopted for this study, observing and describing the characteristics of a phenomenon, which can include situations, objects, people, groups, organisations or environments (Malhotra 2018; Zikmund et al. 2012). The premise of the study was to reveal "what" influences religious e-marketing orientation in religious organisations, and the "what" question can be fully and successfully addressed by descriptive research (Wisker 2008). Surveys were conducted in order to collect primary data and self-administered questionnaires were administered in Zimbabwe, targeting Christian churches.

Research population and sample

The target population was made up of clergymen (pastors, priests, bishops, evangelists and church ministers) from Christian churches in Zimbabwe. The research was conducted countrywide, focusing on all eight provinces: Bulawayo, Harare, Manicaland Province, Mashonaland Central Province, Mashonaland East Province, Mashonaland West Province, Masvingo Province and Matabeleland North Province. The focus was mainly on major towns and cities as "technology use is significantly higher in urban areas than in rural areas" (Magezi 2015: 82).

The sample size for this study was 250 clergymen drawn from different Christian churches in Zimbabwe's major cities and towns. The study employed a proportional stratified sampling technique (Aaker et al. 2015). In this study, the different church organisations were used as strata. Using a simple random sampling technique, sample elements were selected from each stratum.

Data collection

To collect the primary data, a questionnaire was designed. The questionnaire focused on addressing the research objectives. To this end, the questionnaire was structured based on the research variables. The research instrument was operationalised by adapting previous questionnaires measuring the same variables, namely e-marketing orientation (Prasad et al. 2001; Asikhia 2009), dynamic marketing capabilities (Weerawardena 2003), youth marketing (Van der Merwe et al. 2013), marketing innovation (Naidoo 2010), competitive intensity (Asikhia 2009), marketing orientation (Naidoo 2010; Narver & Slater 1990), spirituality (Proeschold-Bell et al. 2014) and religiosity (Leondari & Gialamas 2009).

Most of the previous work was conducted in the commercial sector, so the measurements were adjusted and modified to suit the current church context and purpose. A five-item Likert scale measured all the variables, with anchors ranging from "strongly agree" to "strongly disagree". The previous instruments from which these scales were adapted were based on the five-item Likert scale. The questionnaire consisted of nine sections. The first section dealt with the demographic information of the respondents, whereas the rest of the sections contained questions specific to each research variable. The questionnaire contained mainly multiple-choice and scale questions. All questions in Section A contained multiple-choice questions, where research participants were required to answer by choosing from a specific set of possible responses provided. The rest of the questionnaire contained scaling questions.

Data analysis

Data analysis was a two-stage process. In the first stage, the measurement instrument was assessed for accuracy with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Thus, the accuracy of the construct measures was established. In the second stage, the research model fit to data assessment and testing of the proposed hypothesis was conducted. To achieve the above, structural equation modelling (SEM) was employed to test the measurement properties of the research model and the linear effects hypothesised in this study. Smart PLS was employed as the computation SEM software. Model fitness was assessed and established through global goodness-of-fit statistic, and Chi-square (x2/df) and the normed fit index (NFI).

Hypothesis testing was executed through path analysis, a multivariate analytical methodology for empirically examining sets of relationships in the form of linear causal models (El-Gohary 2012). Path analysis allowed the examination of direct and indirect effects of the seven linear hypotheses based on knowledge and theoretical constructs as reflected in the conceptual model. The reliability of the findings was guaranteed by Cronbach's Alpha (a) and composite reliability index (CR), whereas validity was measured by examining convergent and discriminant validity.

RESEARCH FINDINGS

In this study, a 100% response rate was not achieved. The actual sample size that was achieved was 250 respondents, which represents a 62.5% response rate. The findings from this study depict a 74/26 split ratio between female and male pastors. Thus, 26% of the respondents were female, with 74% male. The research participants were distributed across various churches in Zimbabwe. Most of the respondents (12.1%) indicated that they were from the Apostolic Faith Mission, while 10.5% were from the Roman Catholic Church. A further 10.5% of the respondents were from Zaoga, while 9.3% were from the United Methodist Church, and a further 8.9% from the Anglican Church. Churches such as the Seventh Day Adventist, Methodist in Zimbabwe, Church of Christ and Celebration Church had the least representation, with a representation of 6.5%, 4.8%, 4.8% and 3.2%, respectively. Other churches contributed 28.6%, and consisted of individual churches that had fewer than three respondents each.

Regarding the age of the respondents, the results indicate that most of the respondents were between 31 and 60 years. Specifically, 30.0% of the respondents were between 31 and 40 years, while 33.6% were between 41 and 50 years, while another 24.3% were between 51 and 60 years. Only a small fraction (4.0%) of the respondents was between 18 and 30 years, and another fraction of 8.1% was older than 60 years. Even though the participants were distributed across all five age groups, the views were dominated by participants aged between 41 and 50, followed by participants aged between 31 and 40 years.

The results of the study indicated that most of the respondents had served as church ministers for more than five years. Only 1.2% of the respondents said they had been in church ministry for less than one year, while 19.2% said between one and five years, and another 29.4% said between six and ten years. A further 23.7% had been in the service between 11 and 15 years, while 16.7% had served between 16 and 20 years, and 9.8% were in the pastorate for more than 20 years.

The educational qualifications of the respondents were diverse. The majority of the respondents (60.2%) indicated that they held at least a bachelor's degree as their highest qualification. Most of the respondents (34.0%) held a bachelor's degree, followed by 29.9% who held diplomas, and another 14.3% with Master's degrees. Of the remaining 39.8%, 29.9% held diplomas, while 9.8% of the respondents held ordinary and/or advanced level certificates from secondary and high schools, respectively.

Measurement model assessment

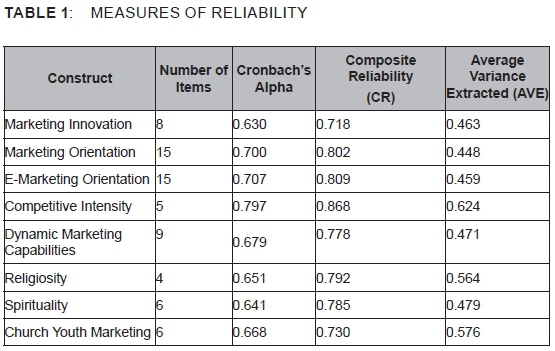

The reliability of the research instrument was checked using the composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and Cronbach's Alpha (a) values, as suggested by Hair et al. (2012). Reliability tests are performed to gauge the consistence, precision, repeatability and trustworthiness of measurement in a study (Chakrabartty 2013).

The internal consistency based on the Cronbach Alpha was acceptable. The majority of the items showed levels of internal consistency above 0.6, as reflected by Cronbach Alpha values in Table 1, and closer to 0.70; hence, the scores were marginally acceptable. The results presented in Table 1 reveal that all the composite reliabilities for each construct were above the recommended value of 0.70, thus being indicative of satisfactory and acceptable internal consistency and reliability of the measures. A cross examination of the results presented in Table 1 shows that the lowest AVE computed for this study was on the marketing orientation construct, which had a value of 0.448, while the highest AVE was on competitive intensity construct, with a value of 0.624. Chinomona and Cheng (2013) advise that an AVE that is above 0.4 should be considered marginally acceptable.

Validity

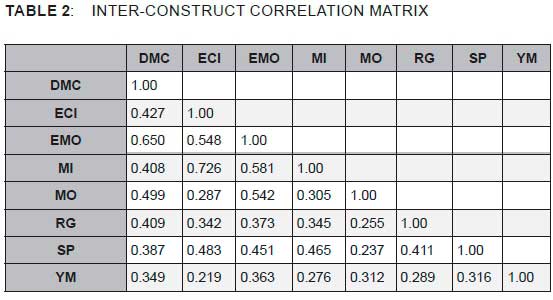

Chinomona (2011) states that discriminant validity is assessed by using correlation matrix.

Table 2 shows the inter-correction values for all the constructs. These are all less than 1.0, hence confirming discriminant validity. Additionally, the discriminant validity was further evaluated by comparing the AVE value to their highest shared variance (HSV), as suggested by Hox et al. (2017). Table 2 assesses discriminant validity by comparing AVE and HSV. The results indicate that all the AVEs are greater than the HSVs of the research constructs, thereby confirming the existence of discriminant validity.

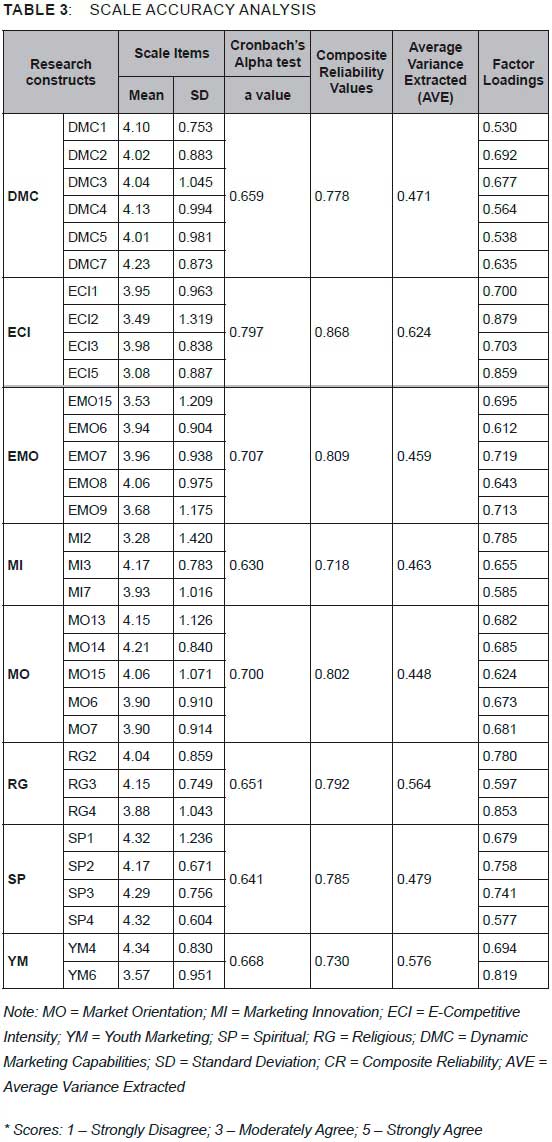

Table 3 provides a summary of the descriptive statistics that were generated using SPSS statistical software, as well as reliability and validity indicators generated by Smart PLS software.

Overall model fit assessment

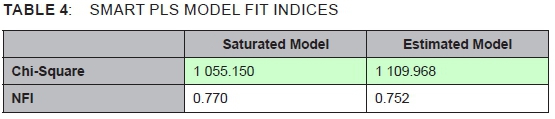

The data fit to the conceptual model was mainly assessed using two indicators, which are the global goodness-of-fit (GFI) and the normed fit index (NFI). The calculated GoF was 0.369, which exceeds the threshold of GoF > 0.36, as suggested by Khojasteh and Lo (2015). Thus, this study concludes that the research model had a good overall fit. The model fit was further assessed using the Chi-square (x2/df) and the NFI. While the Chi-square (x2/df) and NFI did not meet the acceptable threshold, the results in Table 4 can be regarded as marginally acceptable. For instance, NFI should be above 0.8, while 0.9 is regarded as excellent.

By and large, the GoF of 0.369 and the NFI of 0.770 indicate a marginal fit of the data to the proposed conceptual model. On this basis of marginal fit, the authors proceeded to test the proposed hypotheses.

Hypotheses testing

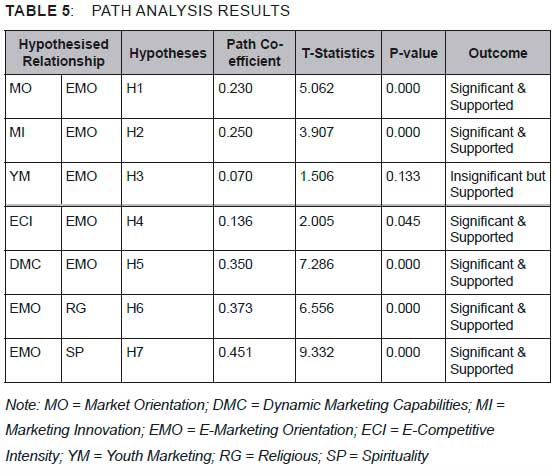

The seven hypotheses were tested, and the path coefficients provided. The significant levels were assessed using p-values and t-statistics. Hypotheses are viewed as significant at a 95% or higher level of significance (> 95%); that is to say, that p-value is < 0.05 (Hair et al. 2012). The path coefficients demonstrate the strength of the relationships between the dependent and the independent variables (Hsu 2008). Upon assessing the probability value, also referred to as the p-value, it was demonstrated that six out of the seven hypotheses postulated were significant at p<0.05, except H3 (p=1.33), which is insignificant. Although positive, H3 was found to be insignificant, as the p-value is greater than 0.05 (0.133).

The results in Table 5 show that all seven the hypotheses were significant. The weak relationship was between church youth marketing and e-marketing orientation (p=0.133; ß=0.070). This was followed by the relationship between competitive intensity and e-marketing orientation (p=0.045; ß=0.136). The strongest was between e-marketing orientation and spirituality (p=0.00; ß=0.451); the second strongest was between e-marketing orientation and religiosity (p=0.000; ß=0.373).

DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

The results indicate that marketing orientation and e-marketing orientation are positively related in a significant way (t=5.907). It was therefore concluded that churches that are marketing-oriented easily adopt electronic marketing practices to advance their mission. These findings were consistent with prior studies. Appah and George (2018) argue that modern marketing-oriented churches place the "unchurched", de-churched and current congregants at the centre stage, and identify new technological innovations that facilitate the spreading of their message. Thus, the implementation of the marketing concept by churches positions them to respond effectively to these challenges through relevant programmes, ministries, services and doctrines (White & Simas 2008).

The findings further reveal that marketing innovation has a strong effect on e-marketing orientation. Furthermore, the results indicate that the relationship between marketing innovation and e-marketing orientation is positive and significant (t=3.907). It can therefore be concluded that the higher the degree of church marketing innovativeness, the higher the levels of adoption of e-marketing practices within the church's programmes and activities. The findings on the relationship between the marketing innovation orientation and e-marketing orientation are supported by available empirical evidence. Organisations such as churches that regularly embark on organisational transformation and organisational development after sensing changes in the market are most likely to adopt new technologies to enhance their competitive position (Golgeci & Ponomarov 2013).

Marketing innovation orientation ignites the churches' capabilities, which are necessary for the adoption of technological innovations (Aksoy 2017). There is therefore a direct relationship between marketing innovation orientation and e-marketing orientation. Flory (2014) suggests that highly innovative religious organisations react to increasing competition and changing market conditions through adopting or appropriating new worshipping styles, methods and techniques, including technological advances, in order to survive, to fulfil their mandate and the mission of the church, and to act as a basis for religious differentiation.

The findings further indicated that church youth marketing is not a (or is a weak) salient determinant of a church's adoption of e-marketing practices and programmes. In fact, the church's focus on youth ministry does not influence it to be e-marketing oriented. This finding raises concern, as it is inconsistent with prior studies. Paul (2001) and Peterson (2004) argue that worldwide organisations, churches included, are struggling and jockeying to better understand, and effectively target the youth. Young people are more sceptical and often mistrust traditional media (Cone Inc 2006; Paul 2001), and are resistant and less likely to be influenced by it (Ciminillo 2005). Instead, they have a preference for reality television, cellular phones, video games and social networks (Valentine & Powers 2013). Bolu (2012) observes that increasingly the majority of youths are turning to the internet in search of personal, social and religious information, thereby compelling religious organisations to jump on the digital bandwagon.

Evidence from this primary research supported and established a positive and significant relationship between competitive intensity and e-marketing orientation. This finding concurs with prior research on technological innovation adoption that suggests that new ideas, processes, practices and concepts are easily and quickly adopted in highly competitive markets, based on the assumption that the innovation might drive the organisation, including churches, to be more agile and in a better position to react to emerging competitive threats (Gu et al. 2012; Gangwar et al. 2014). Competitive intensity is therefore an effective motivator for technology adoption, and positively influences the adoption of technological innovation, especially when the technology is seen as an important catalyst to alter the competitive dynamics in the industry (Lynn et al. 2018; Agrawal 2015). Faced with increasing competitive pressures, churches find the appropriation of digital technologies a prudent strategic move to minimise church membership losses.

The results reveal and confirm that there is an association between dynamic marketing capabilities and e-marketing orientation. Hence, dynamic marketing capabilities directly influence adoption of an e-marketing orientation in churches. Previous research focusing on the association between dynamic marketing capabilities and e-marketing orientation yielded similar findings. According to Morgan et al. (2009), Ramaswami et al. (2008) and Vorhies and Morgan (2005), dynamic marketing capabilities steer superior church performance, and superior dynamic marketing capabilities inspire organisational agility to cope with the volatile religious marketing environment. Uncertainty and dynamism from the religious environment dictate the mastery of dynamic marketing capabilities (Barrales-Molina et al. 2014) in order to create and sustain the competitive advantage for churches (Al-Zyadaat et al. 2012). In the marketing of faith, e-marketing is renowned for accelerating and enabling the development of innovative e-marketing capabilities, including marketing research capacity, church member relationship management ability, religious market intelligence gathering and customisation and personalisation of marketing offerings, and marketing communication (Bauer et al. 2002; Morgan 2012).

The results indicate that the relationship of e-marketing orientation and religiosity is positively related in a significant way, thus implying that as the churches increase their adoption of e-marketing practices, levels of religiosity among congregants increase. This finding is in line with previous research findings, which indicate that e-marketing ultimately influences the growth in church membership and attendance, and its ability to generate adequate resources from the congregants (White & Simas 2008). Thus, e-marketing positively influences both the subjective and objective measures of church performance (Shoham et al. 2006). Scholars, such as Ho et al. (2008), argue that interactions online and religious information search online strengthen an individual's religious beliefs, thereby reinforcing religiosity.

The findings from the study indicate that the influence of e-marketing orientation on spirituality is positive and statistically significant. McKenna and West (2007: 943) assert, the "Internet has become a staple of spiritual life" with many individuals turning to the internet for spiritual comfort. Campbell (2003) argues that other than information search, Christians visit the web for fellowship purposes and seek "to realise the body of Christ" and enrich their spiritual life. Larsen (2001) suggests that most congregants who engage with digital technologies regard the internet as an ecclesiastical library, and therefore search and consume spiritual information online. Bedell (2000) states that e-marketing enhances and reinforces the spiritual life of congregants - an outcome of the accessibility of information and counsel from the internet. The internet has made the availability, variability and accessibility of prayer resources easy, compared to offline resources (Larsen 2001; Narasimhan 2012), thereby enhancing and boosting congregants' commitment to their faith (Dean 2017).

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The study established that one major consequence of an e-marketing orientation is an increase in church member religiosity and spirituality. Churches have traditionally relied on radio and television broadcasts, and newsletters and emails as the key channels for communicating with church members (Fogenay 2013; Dhliwayo 2013). Based on the study findings, it is recommended that churches include digital marketing channels as part of their marketing communication mix. It is important to note that the use of electronic marketing channels will not replace the traditional channels that the churches currently use, but rather complement the existing channels, thereby facilitating a 360-degree approach to church communication efforts.

As is the case with for-profit-making organisations, for churches to be successful in implementing e-marketing practices that are valuable to church members, the adoption and implementation of the marketing concept is a prerequisite. The claim by Slater and Narver (2000), that marketing orientation "is relevant in every market environment" holds true, even in religious markets. The study established that there is a positive and significant relationship between marketing orientation and e-marketing orientation. It is recommended that churches become marketing-oriented, and the mantra that should guide each church is that its existence is hinged on serving the needs and interest of the congregants at large.

The study established that there are significant relationships between marketing innovation orientation, marketing orientation, dynamic marketing capabilities, competitive intensity, and e-marketing orientation. These variables, therefore, influence the adoption of technological innovations by churches. It is thus recommended that technology vendors, manufacturers and innovators targeting the church market effectively segment the churches based on church behaviour towards e-marketing practices. The identified predictors highlight the churches that are more likely to respond positively to the acquisition of technological innovations, and thus, that would enhance value for the vendors or manufacturers.

Linked to the above, it is further recommended that technology vendors and manufacturers should develop a knowledge management system, which would provide them with insights and an understanding of the current technology stacks/infrastructure of different churches. The current technology stack of the churches is valuable to technology vendors or manufacturers; that will assist them in promoting technologies that are compatible with churches' current technologies, or such knowledge will enable the technology vendors to identify opportunities for promoting those technologies with the functionalities that will provide solutions to the challenges faced by churches.

The study established that dynamic marketing capabilities are a salient determinant of e-marketing orientation. The dynamism in the religious market is prompting churches to evolve and keep pace with the current environmental changes. The survival of churches hinges on their ability and capability to adjust, to match or keep up with regular environmental changes (Kachouie et al. 2018). Consequently, it is recommended that churches develop, extend or renew their dynamic marketing capabilities and processes. Such a strategic move would act as a catalyst for the attainment and sustainability of competitive advantage for the churches in these highly competitive and ambiguous environments. Churches with sound dynamic marketing capabilities would generate knowledge about church members' needs and wants, and become effective in crafting programmes and services aligned to the taste and preferences of their congregants. Furthermore, building dynamic marketing capabilities by churches will make them stand out and facilitate the assimilation of marketing practices in their programmes and activities as they seek to improve their performance. Dynamic marketing capabilities are instrumental in matching or creating market change.

It is concluded that competitive intensity and marketing innovation orientation significantly influence the adoption of e-marketing practices by churches. In line with this, it is recommended that technology vendors and manufacturers segment the church market into innovators, early adopters, early majority and late majority, and laggards. Promotional efforts should be based on adopter categories. Moreover, when targeting the innovative and early adopter churches, the technology vendors should focus more on the utility of the innovation, and how it would differentiate the church from other churches. On the other hand, when targeting the early majority, late majority and laggards, the marketing efforts should challenge the churches and exhibit how the innovators and early adopter churches have been successful because of harnessing the technological innovations in their programmes and activities.

It is further recommended that churches offer e-marketing training or short courses to clergy. As shown in the study, clergy have a minimum of secondary education, and the majority with further education focused on church dogma and theological education, which is not business-related (Payne 2014). Pastors with only theological education are ill equipped to effectively deal with marketing related challenges, let alone to implement new concepts such as e-marketing, which integrate marketing and technologies. The e-marketing field is dynamic and expanding. Hence, basic training for clergy will provide them with the prerequisite skills, and internal expertise and understanding, which will help them to design their digital marketing plans and drive e-marketing practices adoption within the church to advance church growth. Extant literature also argues that top management support is critical for the effective adoption of technological innovation (Lai et al. 2014).

REFERENCES

Aaker, D.A., Kumar, V. & Day, G.S. 2015. Marketing research. (Twelfth edition). New York: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Abreu, M. 2006. The brand positioning and image of a religious organisation: an empirical analysis. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 11(2): 139-146. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.49 [ Links ]

Agrawal, K. 2015. Investigating the determinants of Big Data Analytics (BDA) adoption in Asian emerging economies. Chandragupt Institute of Management Patna 1-8. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2015.11290abstract [ Links ]

Aksoy, H. 2017. How do innovation culture, marketing innovation and product innovation affect the market performance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)? Technology in Society 51: 133-141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2017.08.005 [ Links ]

Al-Zyadaat, M.A., Saudi, M.A. & Al-Awamreh, M.A. 2012. The relationship between innovation and marketing performance in business organizations: An empirical study on industrial organizations in the industrial city of King Abdullah II. International Business and Management 5(2): 76-84. [ Links ]

Anghelutä, A.V., Strâmbu-Dima, A. & Zaharia, R. 2009. Church marketing - concept and utility. Journal for the Study of Religions & Ideologies 8(22): 171-197. [ Links ]

Appah, G.O. & George, B.P. 2018. Understanding church growth through church marketing: An analysis on the Roman Catholic Church's marketing efforts in Ghana. Journal of Economics and Business Research 23(1): 103-122. [ Links ]

Arthur, J. & Rensleigh, C. 2015. The use of online technologies in the small church. SA Journal of Information Management 17(1): 1-6. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajim.v17i1.630 [ Links ]

Asikhia, O.U. 2009. The mediating role of e-marketing on the consequences of market orientation in Nigerian Arms. International Journal of Business and Information 4(2): 243-270. [ Links ]

Barna Group. 2009. New research describes use of technology in churches. [Online]. Available at: https://www.barna.org/barna-update/media-watch/40-new-research-describes-use-of-technology-in-churches#.VX5EiUagXS3 [Accessed on 15 June 2015]. [ Links ]

Barrales-Molina, V., Martínez-López, F.J. & Gázquez-Abad, J.C. 2014. Dynamic marketing capabilities: Toward an integrative framework. International Journal of Management Reviews 16(4): 397-416. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12026 [ Links ]

Bauer, H.H., Grether, M. & Leach, M. 2002. Building customer relations over the Internet. Industrial Marketing Management, Internet-Based Business-to-Business Marketing 31(2): 155-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0019-8501(01)00186-9 [ Links ]

Bedell, K. 2000. Dispatches from the electronic frontier: Explorations of mainline Protestant use of the Internet. In: Hadden, J.K. & Cowan, D.E. (eds). Religion on the Internet: Research prospects and promises. Amsterdam: JAI. [ Links ]

Biri, K. 2013. Religion and emerging technologies in Zimbabwe: Contesting for space? Religion 1(1): 19-27. [ Links ]

Bolu, C.A. 2012. The church in the contemporary world: Information and communication technology in church communication for growth: A case study. Journal of Media and Communication Studies 4(4): 80-94. https://doi.org/10.5897/JMCS11.087 [ Links ]

Booth, M.E. & Philip, G. 1998. Technology, competencies, and competitiveness: The case for reconfigurable and flexible strategies. Journal of Business Research, Dynamics of Strategy 41(1): 29-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(97)00009-X [ Links ]

Brady, M., Saren, M. & Tzokas, N. 2002. Integrating information technology into marketing practice - the IT reality of contemporary marketing practice. Journal of Marketing Management 18(5-6): 55-577. https://doi.org/10.1362/0267257022683703 [ Links ]

Brodie, R.J., Winklhofer, H., Coviello, N.E. & Johnston, W.J. 2007. Is e-marketing coming of age? An examination of the penetration of e-marketing and Arm performance. Journal of Interactive Marketing 21(1): 2-21. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20071 [ Links ]

Butler, S. 2014. Presents of God: The marketing of the American prosperity gospel. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Pittsburgh. [ Links ]

Campbell, H. 2003. Approaches to religious research in computer-mediated communication. In: Mitchell, J. & Marriage, S. (eds.) Mediating religion: Studies of media, religion and culture. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. [ Links ]

Chakrabartty, S.N. 2013. Best split-half and maximum reliability. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education (IOSRJRME) 3(1): 1-8. https://doi.org/10.9790/7388-0310108 [ Links ]

Chinomona, R. 2011. Non-mediated channel powers and relationship quality: A case of SMES in Zimbabwe channels of distribution. Unpublished doctoral thesis. National Central University, Taiwan. [ Links ]

Chinomona, R. & Cheng, J.M-S. 2013. Distribution channel relational cohesion exchange model: A small-to-medium enterprise manufacturer's perspective. Journal of Small Business Management 51(2): 256-275. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12011 [ Links ]

Cone Inc. 2006. The Millenial Generation: Pro-social and empowered to change the world. Boston, MA: Cone, Inc. [ Links ]

Considine, J.J. 1995. Broadening the marketing concept to churches. Journal of Ministry Marketing & Management 1(1): 25-35. https://doi.org/10.1300/J093v01n01_03 [ Links ]

Dean, N. 2017. Many ways of connecting: Where spirituality and technology meet. Brain World. [Online]. Available at: https://brainworldmagazine.com/many-ways-connecting-spirituality-technology-meet/ [Accessed on 19 June 2018]. [ Links ]

Dhliwayo, K. 2013. People's perception of promotional strategies for church growth in Zimbabwe: A case of Pentecostal churches in Masvingo. The International Journal of Business & Management 1(6): 74-81. [ Links ]

Dodo, O., Banda, R.G. & Dodo, G. 2014. African Initiated Churches, pivotal in peace-building: a case of the Johane Masowe Chishanu. [Online]. Available at: https://dspace.creighton.edu/xmlui/handle/10504/64343 [Accessed on 7 June 2015]. [ Links ]

Einstein, M. 2008. Brands of faith: marketing religion in a commercial age. Religion, media and culture series. London; New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203938874 [ Links ]

El-Gohary, H. 2012. Factors affecting e-marketing adoption and implementation in tourism Arms: An empirical investigation of Egyptian small tourism organisations. Tourism Management 33(5): 1256-1269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.10.013 [ Links ]

Flory, R. 2014. Competition, innovation and the future of religion. Center for Religion and Civic Culture. [Online]. Available at: https://crcc.usc.edu/competition-innovation-and-the-future-of-religion/ [Accessed on 16 June 2018]. [ Links ]

Fogenay, K.A-L.J. 2013. A Christian mega church strives for relevance: Examining social media and religiosity. Las Vegas, University of Nevada. [Online]. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2988&context=thesesdissertations [Accessed on 29 April 2018]. [ Links ]

Foley, J.C. 2002. What John Paul II said about the Internet. [Online]. Available at: http://www.michaeljournal.org/articles/other-topics/item/what-john-paul-ii-said-about-the-internet [Accessed on 30 April 2018]. [ Links ]

Gangwar, H., Date, H. & Raoot, A.D. 2014. Review on IT adoption: insights from recent technologies. Journal of Enterprise Information Management 27(4): 488-502. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-08-2012-0047 [ Links ]

Garland, C. 2014. Vatican social media guru: Catholics should give Internet 'a soul'. Los Angeles Times, 13 August. [Online]. Available at: http://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-tn-vatican-social-media-expert-20140813-story.html [Accessed on 30 April 2018]. [ Links ]

Golgeci, I. & Ponomarov, S. 2013. Does Arm innovativeness enable effective responses to supply chain disruptions? An empirical study. Supply Chain Management 18: 604617. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-10-2012-0331 [ Links ]

Gu, V.C., Cao, Q. & Duan, W. 2012. Unified Modeling Language (UML) IT adoption - A holistic model of organizational capabilities perspective. Decision Support Systems 54(1): 257-269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2012.05.034 [ Links ]

Hackett, R.I.J. 1998. Charismatic/Pentecostal appropriation of media technologies in Nigeria and Ghana. Journal of Religion in Africa 28(3): 258-277. https://doi.org/10.1163/157006698X00026 [ Links ]

Hair, J.F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C.M. & Mena, J.A. 2012. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40(3): 414-433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6 [ Links ]

Han, S. 2016. Technologies of religion: Spheres of the sacred in a post-secular modernity. London; New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315720081 [ Links ]

Ho, S.S., Lee, W. & Hameed, S. S. 2008. Muslim surfers on the internet: using the theory of planned behaviour to examine the factors influencing engagement in online religious activities. New Media & Society 10(1): 93-113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444807085323 [ Links ]

Hsu, S-H. 2008. Developing an index for online customer satisfaction: Adaptation of American Customer Satisfaction Index. Expert Systems with Applications 34(4): 3033-3042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2007.06.036 [ Links ]

Ivanov, A.E. 2012. The Internet's impact on integrated marketing communication. Procedia Economics and Finance, International Conference Emerging Markets Queries in Finance and Business. Petru Maior University of TTrgu-Mures, Romania. [ Links ]

Kachouie, R., Mavondo, F. & Sands, S. 2018. Dynamic marketing capabilities view on creating market change. European Journal of Marketing 52(5/6): 1007-1036. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2016-0588 [ Links ]

King, L.A., Heintzelman, S.J. & Ward, S.J. 2016. Beyond the search for meaning. A contemporary science of the experience of meaning in life. Current Directions in Psychological Science 25(4): 211-216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721416656354 [ Links ]

Kotler, P. 2005. The role played by the broadening of marketing movement in the history of marketing thought. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 24(1): 114-116. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.24.1.114.63903 [ Links ]

Kotler, P. & Keller, K.L. 2016. Marketing management. (Fifteenth edition). Harlow: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Kotler, P. & Levy, S.J. 1969. Broadening the concept of marketing. Journal of Marketing 33(1): 10-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224296903300103 [ Links ]

Krause, N. 2003. Religious meaning and subjective well-being in late life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 58(3): S160-S170. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.3.S160 [ Links ]

Larsen, E. 2001. CyberFaith: How Americans pursue religion online. Pew Research Center. [Online]. Available at: http://www.pewinternetorg/fNes/old-media//FNes/Reports/2001/PIP_CyberFaith_Report.pdf.pdf [Accessed on 18 June 2018]. [ Links ]

Leondari, A. & Gialamas, V. 2009. Religiosity and psychological well-being. International Journal of Psychology 44(4): 241-248. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590701700529 [ Links ]

Lovelock, C. & Wirtz, J. 2016. Services marketing: People, technology, strategy. (Eight edition). New Jersey: World Scientific Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Lynn, T., Liang, X., Gourinovitch, A., Morrison, J.P., Fox, G. & Rosati, P. 2018. Understanding the determinants of cloud computing adoption for high performance computing. In: 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS-51). University of Hawai'i at Manoa. https://doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2018.489 [ Links ]

Magezi, V. 2015. Technologically changing African context and usage of information communication and technology in churches: towards discerning emerging identities in church practice (a case study of two Zimbabwean cities). HTS: Theological Studies: Practical Theology 71(2): 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v71i2.2625 [ Links ]

Malhotra, N.K. 2018. Marketing research: an applied orientation. (Seventh edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. [ Links ]

McKenna, K.Y.A. & West, K.J. 2007. Give me that online-time religion: The role of the internet in spiritual life. Computers in Human Behavior, Special Issue: Internet and Well-Being in Honor of the Memory of Michael Argyle 23(2): 942-954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2005.08.007 [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, M.C., Grobler, A.F., Strasheim, A. & Orton, L. 2013. Getting young adults back to church: A marketing approach. Hervormde Teologiese Studies 69(2): 1-12. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v69i2.1326 [ Links ]

Morgan, N.A. 2012. Marketing and business performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40(1): 102-119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0279-9 [ Links ]

Morgan, N.A., Slotegraaf, R.J. & Vorhies, D.W. 2009. Linking marketing capabilities with profit growth. International Journal of Research in Marketing 26(4): 284-293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2009.06.005 [ Links ]

Moyo, Fr. A. 2016. Christianity now a spiritual supermarket. Sunday Mail, 18 December. [Online]. Available at: http://www.sundaymail.co.zw/christianity-now-a-spiritual-supermarket/ [Accessed on 19 December 2016]. [ Links ]

Mulyanegara, R.C. 2009. Church marketing: the role of market orientation and brand image in church participation. Australia, Monash University. [ Links ]

Naidoo, V. 2010. Firm survival through a crisis: The influence of market orientation, marketing innovation and business strategy. Industrial Marketing Management, Building, Implementing, and Managing Brand Equity in Business Markets 39(8): 1311-1320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2010.02.005 [ Links ]

Narasimhan, B. 2012. Spirituality and technology: Finding the balance. Huffington Post. [Online]. Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/bhanu-narasimhan/spirituality-and-technology_b_1149312.html. [ Links ]

Nardella, C. 2014. Studying religion and marketing. An introduction. Sociologica 8(3): 1-15. [ Links ]

Paul, P. 2001. Getting inside Gen Y. [Online]. Available at: http://adage.com/article/american-demographics/inside-gen-y/43704/ [Accessed on 31 July 2015]. [ Links ]

Payne, J.S. 2014. The influence of secular and theological education on pastors' depression intervention decisions. Journal of Religion and Health 53(5): 1398-1413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9756-4 [ Links ]

Peterson, K.2004. Savvy GenYisn'tbuying traditional sales pitches. Seattletimes.com[Online]. Available at: http://old.seattletimes.com/html/businesstechnology/2001930771_genygames17.html [Accessed on 3 August 2015]. [ Links ]

Prasad, V.K., Ramamurthy, K. & Naidu, G.M. 2001. The influence of internet-marketing integration on marketing competencies and export performance. Journal of International Marketing 9(4): 82-110. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.9.4.82.19944 [ Links ]

Proeschold-Bell, R.J., Yang, C., Toth, M., Rivers, M.C. & Carder, K. 2014. Closeness to God among those doing God's work: A spiritual well-being measure for clergy. Journal of Religion and Health 53(3): 878-894. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9682-5 [ Links ]

Ramaswami, S.N., Srivastava, R.K. & Bhargava, M. 2008. Market-based capabilities and financial performance of firms: insights into marketing's contribution to firm value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 37(2): 97-116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-008-0120-2 [ Links ]

Russell-Bennett, R., Wood, M. & Previte, J. 2013. Fresh ideas: services thinking for social marketing. Journal of Social Marketing 3(3): 223-238. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSOCM-02-2013-0017 [ Links ]

Sandilands, T. 2014. Difference between for profit & not for profit marketing. [Online]. Available at: http://smallbusiness.chron.com/difference-between-profit-not-profit-marketing-20804.html [Accessed on 20 April 2018]. [ Links ]

Shoham, A., Ruvio, A., Vigoda-Gadot, E. & Schwabsky, N. 2006. Market orientations in the nonprofit and voluntary sector: A meta-analysis of their relationships with organizational performance. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 35(3): 453476. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764006287671 [ Links ]

Slater, S.F. & Narver, J.C. 2000. The positive effect of a market orientation on business profitability: A balanced replication. Journal of Business Research 48(1): 69-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(98)00077-0 [ Links ]

Stroope, S., Draper, S. & Whitehead, A.L. 2013. Images of a loving God and sense of meaning in life. Social Indicators Research 111(1): 25-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9982-7 [ Links ]

Surbhi, S. 2016. Difference between profit and non-profit organisation. Key Differences. [Online]. Available at: https://keydifferences.com/difference-between-profit-and-non-profit-organisation.html [Accessed on 20 April 2018]. [ Links ]

Tiago, M.T. & Tiago, F. 2012. Revisiting the impact of integrated internet marketing on firms' online performance: European evidences. Procedia Technology, 4th Conference of ENTERprise Information Systems - aligning technology, organizations and people (CENTERIS 2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2012.09.046 [ Links ]

Togarasei, L. 2012. Mediating the gospel: Pentecostal Christianity and media technology in Botswana and Zimbabwe. Journal of Contemporary Religion 27(2): 257-274. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537903.2012.675740 [ Links ]

Trainor, K.J., Rapp, A., Beitelspacher, L.S. & Schillewaert, N. 2011. Integrating information technology and marketing: An examination of the drivers and outcomes of e-marketing capability. Industrial Marketing Management, Business-to-Business Marketing in the BRIC Countries 40(1): 162-174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2010.05.001 [ Links ]

Usunier, J-C. & Stolz, J. 2014. Religions as brands: New perspectives on the marketization of religion and spirituality. England: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Valentine, D.B. & Powers, T.L. 2013. Generation Y values and lifestyle segments. Journal of Consumer Marketing 30(7): 597-606. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-07-2013-0650 [ Links ]

Vorhies, D.W. & Morgan, N.A. 2005. Benchmarking marketing capabilities for sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Marketing 69(1): 80-94. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.69.1.80.55505 [ Links ]

Weerawardena, J. 2003. The role of marketing capability in innovation-based competitive strategy. Journal of Strategic Marketing 11(1): 15-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254032000096766 [ Links ]

White, D.W. & Simas, C.F. 2008. An empirical investigation of the link between market orientation and church performance. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 13(2): 153-165. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.314 [ Links ]

Wielstra, S. 2012. Social media and the church: A systematic literature review. [ Links ]

Wisker, G. 2008. The postgraduate research handbook: succeed with your MA, MPhil, EdD and PhD. Palgrave study skills. (Second edition). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Wright, S.A. 2010. Selling salvation like soap: Christian evangelism as social marketing. United Kingdom, University of Manchester. [ Links ]

Zikmund, W.G., Carr, J.C., Griffin, M. & Barry, J.B. (eds). 2012. Business research methods. (Ninth edition). Australia: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

Date submitted: 08 January 2020

Date accepted: 04 September 2020

Date published: 29 December 2020