Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Communitas

On-line version ISSN 2415-0525

Print version ISSN 1023-0556

Communitas (Bloemfontein. Online) vol.25 Bloemfontein 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150525/comm.v25.9

ARTICLES

Gendered myths, risks and the social amplification of male rape: online discourses

Dr Karabo SittoI; Prof. Elizabeth LubingaII

IDepartment of Strategic Communication, Faculty of the Humanities, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. Email: ksitto@uj.ac.za (corresponding author); ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5146-9189

IIDepartment of Strategic Communication, Faculty of the Humanities, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. Email: elizabethl@uj.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1811-7421

ABSTRACT

Male rape remains largely obscure in communication discourses; on rare occasions it suffers juxtaposition against its much-publicised counterpart, female rape. Yet victims of male rape too suffer various physical, sexual, emotional and mental health risks, as well as lack of much-needed support systems. In general, social networking sites (SNSs) have provided a democratic space to facilitate discourses about risky problems, enabling polarised discussions and perspectives towards matters, such as male rape, where few such platforms previously existed. This article explores online discourses about male rape. A netnography approach was used to analyse over 122 tweets. The results indicate that male rape is trivialised through the oversimplification of its definition and the downplaying of victims' experiences. In discourses, prevailing gendered online conversations centred on and amplified female rape, barely acknowledging the trauma and suffering of male rape victims. Of note were some voices calling for more awareness about male rape and calls to stop gendered norms from deterring survivors from sharing experiences. The findings underscore the argument that although conversations highlighting male rape continue to be suppressed in societies, SNSs have the potential to be used as instruments of awareness and support for victims.

Keywords: male rape; gendered myths; online discourses; social amplification; male rape awareness; Twitter; online communication; health communication

INTRODUCTION

Failure to acknowledge the reality of occurrences of male rape results in numerous risks to the individual, family, community and society. For instance, victims' failure to disclose experiences timeously reduces the possibility of receiving the support and assistance they require. Many societies still fuel the male rape myth and related nondisclosure by failing to treat victims with dignity, acknowledge and put necessary systems in place to assist male victims of sexual assault (Javaid 2015; Vaglanos 2017).

Online spaces have opened up platforms for the amplification of health issues previously considered too risky for discussion in the public sphere. For instance, individuals have disclosed their HIV status online, while organisations have conducted HIV stigma reduction campaigns on social media (Young et al. 2019). From online disclosure, individuals have enjoyed benefits such as receiving information and sharing experiences, where they were previously unable to inform partners about their seropositivity through face-to-face conversations (Taggart et al. 2015). Specifically, an app popular for gay dating, Grindr, encourages users to disclose their HIV status and has introduced opt-ins to provide testing reminders for the user (The Lancet HIV 2018). Risky health issues have gained traction, from SNSs filtering into traditional media, enabling the necessary debates and reducing stigma. Conversely, the anonymous nature of SNSs also allows polarised views about risky issues, such as male rape, to run rampant, which could promote and sustain the dominance of hegemonic perspectives leading to stigmatisation.

This article examines how Twitter has enabled diverse societal conversations about male rape. It contextualises the risks that male rape victims face through examining the gendered norms, myths and perceptions prevalent in society. The purpose was to explore the content of online discourses about male rape, which is hardly discussed by victims and at different levels in society, with most of the focus placed on female rape.

Multi-layered risks of male rape

The risks of male rape occur at multiple levels. At an individual level, male rape victims who disclose victimisation face the risk of reprisal manifesting through stigma and stereotypes in society; thus, they have trouble in reporting their experiences (Young et al. 2016). Both child and adult male victims are less likely to report their victimisation because of shame and guilt, the anticipation of rejection, as well as having their sexuality questioned (Cummings et al. 2018; SAMSOSA 2019a; Tewksbury 2007). At family level, victims run the risk of ridicule and rejection. The perceived social risk of disclosure can be a deterrent (to disclosure) where the social risk is a lack of support from the personal networks of the victim (Hodges et al. 1997).

Health experts have reported on the multitudinous consequences of untreated male rape victims and the risks they face. Victims bear psychological, emotional, sexual and physical health risks if they are not helped. In many countries, male rape victims are ridiculed by officials from state departments, such as when reporting the crime, while others are stigmatised by health officials meant to treat them (BBC 2018; Davies 2002). Male victims could face more specific health risks, such as sexual anxieties (De Visser et al. 2003), sexual dysfunction and possibly impotence, and systemic barriers because most health services are geared toward females (Cummings et al. 2018).

Tewksbury (2007) argues that few societal discussions occur about the physical, mental and sexual health consequences of sexual assault against men. When such discussions occur, they often package male rape as an ill that is exclusive to men in correctional centres. Such ill-conceived perceptions serve to undermine other (also) legitimate experiences of men who experience rape in other contexts, outside of the prison environment, including war zones (Ferrales et al. 2016). While the rape experience is real and traumatic for male and female victims, societies often question whether a man can be raped. Reactions by communities and service providers to male sexual assault victims often depend on the (perceived) sexual orientation of the victim, as well as the perpetrator's gender (Davies 2002). Societies appear to be more sympathetic to female and child rape victims, with both groups designated as vulnerable in most countries. The negative effects, which arise from the rape of men, differ slightly from those of women. In South Africa, the sexual abuse of men remains underreported and largely undisclosed by victims when it does occur (SAMSOSA 2019a). There are no official statistics about male sexual abuse in South Africa, mainly due to denial about its occurrence (ibid.).

Given that male victims rarely report male rape, the possibility is that the actual number of victims is higher. In the UK, 96% of male rapes go unreported (BBC 2018), even though reports of sexual offences against men and boys have more than tripled in the past decade. Statistics show that there were 12 130 offences reported in England and Wales in 2016/17, compared to 3 819 in 2006/07. These statistics might show an increase because many of the male rape victims reported historical experiences (BBC 2018; Cummings et al. 2018).

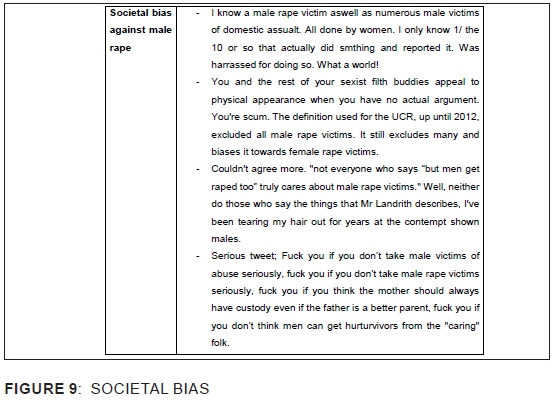

Societal bias

The largely obscure male rape problem, if not ignored by society, is constantly juxtaposed against female rape and arguments of feminist agendas, which further minimises it to the point of trivialising the experiences of self-reported victims. Societies constantly monitor female and child rape statistics. In South Africa, for instance, 2018 statistics indicated that over 40% of rape cases in the country were committed against children (Andersen 2018). Services that societies avail to victims of rape, such as the Teddy Bear Foundation in South Africa, are often tailored towards serving women and children, who are afforded privacy, leading to the marginalisation of men. Young et al. (2016) found that many of the female rape victims studied were provided with family and other support, in addition to referrals to secondary services, when compared to the males.

In patriarchal societies, where male victims of sexual abuse are often ridiculed, discreet support services could better provide much-needed privacy, which would encourage disclosure by male victims. Discreet support would enable male victims to find services for their mental, emotional and physical health. Male rape is often shrouded in myths, including beliefs that boys and men cannot fall victim to sexual abuse, or that the perpetrators of male sexual abuse are always male (SAMSOSA 2019b). Such myths result in the stereotyping and labelling of male rape victims as homosexual. More importantly, the inability to counter these myths results in self-ostracism by victims who feel disempowered to dispute the information. If male victims feel that they will lose social capital due to cultural influences or processes, the social risks are higher, and the pressure not to disclose is greater.

Masculinity norms and representations

Masculinity norms driving the male sexual rape myth prevailing in many societies. The BBC (2018) reported that the Chief Executive of a UK male rape and sexual abuse charity organisation said men who disclosed their victimisation received comments like "men can't get raped, they can't be sexually abused", and were treated with disbelief.

Many patriarchal societies perpetuate hegemonic masculinity and sexism, cultivating expectations of a gender order in society in which the male is represented as an alpha - the dominant and more superior sex. Javaid (2017) notes that male rape victims symbolise subordinate masculinities, perceived to be vulnerable, they are "othered", marginalised and considered to be abnormal. Social representations of men are often based on expressions of power, wealth, leadership and control. All these social representations centre on the male being a dominant member of society, on whom expectations of taking charge in society and the state are placed. In societal representations, few spaces can be found for men of different physiques, sexual orientations, or atypical gender roles. The notion of male rape challenges social representations of hegemonic masculinity prevailing in many societies, making society uncomfortable with the idea of males being in a position of perceived weakness. Reitz-Krueger et al. (2017) state that societies' relative neglect of male rape victims may partly be a result of "faulty" rape myths suggesting that men cannot be sexually assaulted, especially by women.

Male rape is a social violation of the common representation of males as the guardians of society. Rather than being seen as a social risk, due to the potential reaction of members of society to reports of male rape, non-disclosure is considered by individuals to assume an absence of the issue (SAMSOSA 2019b). Non-disclosure is rife in clashes for social dominance, such as during times of war when rape is used as a tool of submission and to dominate societies by bringing their 'strongest' members to breaking point (Storr 2011).

Male rape is historic too. History shows the prevalence of using male rape for social dominance (Johnson 2018). Reports of such occurrences are documented during the colonial rule of natives being subordinated, using male rape of the strongest and most dominant males of native societies. The rape of enslaved men was common in the southern United States of America and Cuba, where it was a part of the slave system by the Spanish. Even then, though the rape of enslaved men was as prevalent as the rape of enslaved women, the phenomenon of enslaved men being raped remained unknown because men were "generally shy to voice that they had been raped by male merchants or their owners" (ibid.). In addition, stories of enslaved men being raped were not believed, given that many of the perpetrators were married or had several girlfriends.

Another social risk of male rape is the clandestine manner in which victims are lured by their violators and taken advantage of. As with other sexual violations, more often than not, the perpetrator of male rape is intimately known to the victim, is part of their social network, and is a trusted, well-respected member of society. In the USA, 7 out of 10 rapes are committed by someone that the victim knows (Vaglanos 2017).

Examples of perpetrators include teachers, child minders, relatives, or church clergy. There are multiple reports of the systematic and repeated abuse of male children, who are shunned for making such accusations against their perpetrators because of the social power the perpetrators hold. This served as a deterrent for other victims to come forward, perceiving the social risk of disclosing to be too costly, and risking their social capital, however, small it might be.

Obscurity of male rape narratives

Many societies misconstrue male-on-male rape to be a homosexual act. Male victims of rape are labelled as homosexual, with perceptions about them being willing participants of those experiences. South African gender activist, Mbuyiselo Botha, states that reported male rape cases are few because men are viewed to be willing partners in the experience (Shange 2019). "More often than not, you would hear that society says men cannot be raped or violated. It is assumed that the men are always ready for sex so when you are asking about how many of them report such cases, it is next to zero" (ibid.).

Societal stigma against male rape, buoyed by cultures, exhorts men (including victims) to show their masculinity through a display of strength and silence, with speaking out about it perceived to be a sign of weakness. Male rape is not only a risk to the survivor, but to family and friends who may not know how to relate to their relative's traumatic experience or to assist them to cope with the effects, which could include psychological, emotional or physical - medically related among others - effects. As Mann (2015) argues, "There needs to be a dialogue and a safe space for men to confront these experiences and come to terms with the fact that they are not to blame".

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Social amplification of risk framework (SARF)

The social amplification of risk framework (SARF) provides a structural description of how various hazardous events interact with psychological, social, institutional and cultural processes, leading to the intensification or attenuation of risk perceptions and related risk behaviours (Sarathchandra & McCright 2017: 2). These authors argue that news media amplify risk signals and events, and in the absence of personal experience, individuals learn about the risks through traditional and electronic media. The media thus play an important role in creating awareness and building knowledge about risks in society. In the case of male rape, such knowledge could contribute to demystification of the longstanding male sexual rape myth and influence prevailing masculinity norms that negate the experiences and reporting of victimisation by victims.

As SNSs have grown in popularity, they have become a significant part of the media mix that amplified risks (Best et al. 2014). However, social media might not always be used as spaces for self-expression; they might reinforce a spiral of silence between users who know one another in offline settings (Boyd & Ellison 2007; Gearhart & Zhang 2015).

Depending on the type of risk, how it is reported, and the public's reaction to it, these factors determine how much social attention it can generate; that is, risk amplification (Kasperson 1992; Kasperson & Kasperson 1996). Risk attenuation (Sarathchandra & McCright 2017), such as that of male rape, is fuelled by cultural discourses and boundaries with respect to the societal representation of males as being the dominant gender. Male rape bears high risk and yet receives little social attention with respect to its prevalence, the narratives of the victims, the perpetrators within society, and how survivors can be helped. Victims of male rape might risk not having any support as notions of culture demand the protection of families or the communities' image, with the individual needing to be altruistic in his experience. The disclosure of male rape, or even the voicing of victimisation might be considered cultural dissent, and victims could be shunned or ostracised.

Male victims of rape could be emasculated and mocked, and have their masculinity brought into question through their disclosure. They bear the social risk of there being no support for their story, should they disclose, and possibly to the point of them having no personal network due to rejection, particularly if they do not retract their public disclosure (Young et al. 2016). This amplifies the social risk to male rape victims, making them even more vulnerable to social scrutiny of their lifestyle. Male rape victims "...are also at social risk for victimization, that is, if they lack friends who can protect them or if they are widely devalued by peers" (Hodges et al. 1997: 1037).

Social media has provided a space for activism for previously incommunicable issues, giving a space to voices previously not heard in media spaces (Pal & Dutta 2008). Male rape victims might find online communities of support; thus, reducing their social risks. The victims could use SNSs to increase their social capital (Best et al. 2014), and in turn gain friends and personal networks online that could protect them as a group and at an individual level (Hodges et al. 1997). This support is critical for victims of male rape. The social and technical risks for victims of male rape could be amplified online by the survivors and their allies using SNSs as democratised spaces to amplify the experiences of silenced male rape victims and to prevent a spiral of silence.

Spiral of silence theory

The spiral of silence theory explains why some opinions become publicly explained, while others are not discussed. The theory assumes that the media in general limit the range of opinions that are available to the public (Noelle-Neumann 1973). Moreover, issues that are value-laden or morally controversial tend to evoke public discussions (Noelle-Neumann 1993; Scheufele 2007). In relation to social media, the spiral of silence theory reinforces relationships between users who know one another in offline settings (Boyd & Ellison 2007; Gearhart & Zhang 2015). However, the online opinion environment can differ greatly from an individual's offline world in such a way that the opinions he/she comes across online are likely to be more diverse (Schulz & Rössler 2012). For an emerging issue such as male rape, online spaces could offer a necessary platform for diverse, though possibly polarised, narratives about an issue that is seldom talked about. Conversely, online settings could enable patterns of selective exposure, with the same issues being discussed; ultimately restricting the diversity of viewpoints that users might encounter (Garrett 2009). The theory was developed during the age of traditional mass media, yet is applicable to online media. Some authors (Matthes et al. 2013; Schulz & Rössler 2012) argue that the pressure to suppress minority opinions might be minimised by the proliferation of online and social media, and challenge the theory's key assumption of the muting of dissenting voices by dominant ones. In online settings, the spiral of silence is still possible regarding certain social issues where hegemonic voices reign, for such domination to occur. In online settings, individuals who are certain about their opinions are not reluctant to express them (Leonhard et al. 2018; Zerback & Fawzi 2017).

METHODOLOGY

The study used Twitter conversations harvested in April 2019 (Sexual Awareness Month) with the hashtag #SexualAssaultAwarenessMonth to evaluate the types of discussions and the volume in comparison to other sexual violations.

The term "male rape" was used as a filter to understand the discourses that took place during the month. The tweets were combined in a single document and the text was formatted to prepare the content for netnographic analysis. The study employed netnography, a rigorous methodology suited for studying the uniqueness of online communities (Kozinets 2002: 62).

Kozinets (2015: 98) developed 12 methodological steps, which are "non-exclusive and often-interacting process levels" of netnography. The 12 steps were used in a non-linear fashion for purposes of engaging in netnography on the topic of male rape in the following manner:

1. Introspection - reflection of the role of research in approaching how the data would help achieve the research aims and objectives of the study. This included reflection on the limited social discourses with respect to the risks of male rape in the purposive selection of online conversations on the topic.

2. Investigation - the search for conversations on sexual assault online on Twitter during an awareness month, namely April 2019, centred on collecting data for the purpose of analysing public conversations about male rape.

3. Information - ethical considerations involved accessing only publicly available conversations on Twitter, including building anonymity in the interpretation of the data collected by excluding the handles of users.

4. Interview - the sites to be inspected were Twitter and Facebook, although there was more volume on Twitter, and only these high volume conversations were included for analysis.

5. Inspection - this linked to the conversations on #SexualAssault-AwarenessMonth and specifically those mentioning the term "male rape" over the month of April, with thorough analysis and data collection of each thread of the conversation.

6. Interaction - the entrée strategy was through a public search on Twitter, which allowed for these conversations to be identified.

7. Immersion - the authors had to immerse themselves in the conversations, including reading article links, analysing each picture and video, as well as collecting the original tweets and replies on male rape.

8. Indexing - this phase was about weighting the data collected with respect to the social and technical risks of male rape, selecting more high quality and meaningful data from each conversation.

9. Interpretation - interpretive analysis, which is termed interpenetration; that is, an analysis-seeking depth of understanding. The interpretation was done using the social risk theory to code the tweets in an attempt to understand them without distorting them through interpretation.

10. Iteration - there were phases within these phases for this netnographic analysis, including thematic analysis from coding to the development of themes and arrangement on tweets across different themes.

11. Instantiation - for this article, the analysis approach that was most appropriate was humanist, given the sensitivity of the topic of male rape and the gendered nature of the conversations.

12. Integration - the authors then integrated the data with the research objectives to develop insights from the netnography, forming part of the overall findings and interpretation discussion of this article.

One of the benefits of netnography is the near-automatic transcription of the contents downloaded, and the ease with which the data was obtained (Kozinets 2002). Netnography helps provide insights into individuals' experiences (Xun & Reynolds 2010) with respect to male rape, and how they communicate these experiences. Netnography as a method therefore "provides a window into the cultural realities" (Kozinets 2006: 282), such as those of male rape in South Africa, the social discourses and arising themes.

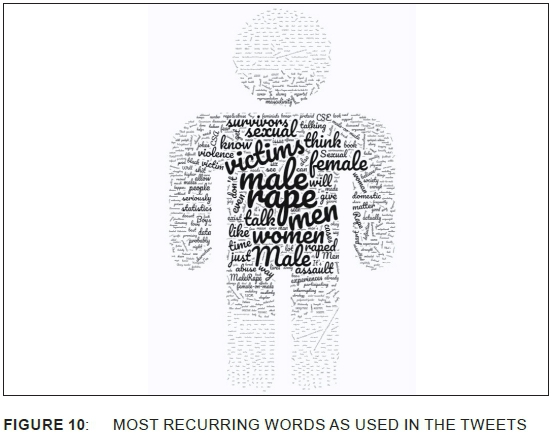

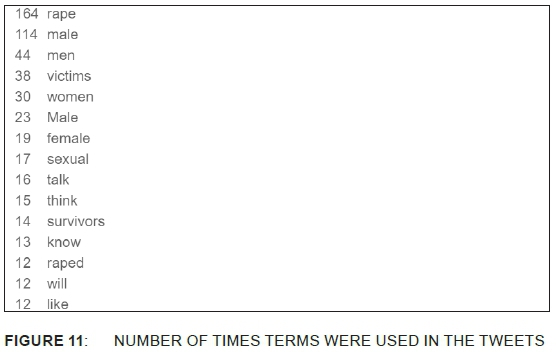

People frequently take part in important discussions in their online communities, such as Twitter, to inform and influence each other using "relevant symbol systems" (Kozinets 2002: 61) that are culturally informed. Only publicly accessible tweets were used, and none were selected from any private conversations or direct messages, to which the authors had no access. The tweets analysed included multimodal media, such as memes, emojis, images, gifs and videos, as this article was not only interested in conversations, but other representations of social risks in discussions of male rape online. To add texture to the data, the tweets were also analysed using a Word cloud to observe the frequency of terms on male rape.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A total of 122 tweets were coded and analysed. The authors took cognisance of the fact that Twitter as an online tool, by limitation, allows a privileged few with access to online facilities to engage in conversations. Emergent themes were considered significant if two or more tweets carried similar sentiments with respect to an aspect of male rape, and these ranged from discussions to views. The most notable themes involved constant juxtaposition of male rape and female rape, as well as gendered stereotypes about males, including sexual orientation. Tweets referring to the sexual behaviour of men, as being responsible for them being raped, or the perceived lower risk of male rape compare to female rape, contributed to the risk attenuation of victims of male rape.

PERCEPTIONS AND MISCONCEPTIONS TOWARDS MALE RAPE

The most prevalent observation from the tweets is the lack of consistency with respect to definitions of male rape. Even in an online "democratised" space, where voices should be equal, male rape discussions were dominated by challenges of definitions, based on how female rape is defined. The primary challenge within this theme was the idea that only men are able to rape, a cultural stereotype of masculinity, and that by definition rape only involves a male penetrating a female forcefully without consent.

'Willing' male rape victim?

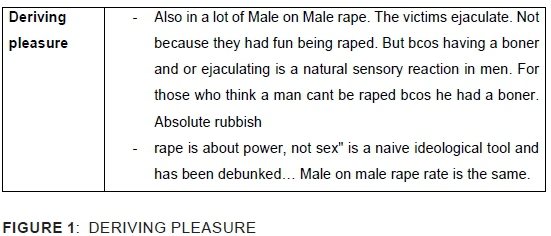

Discussions arose regarding male rape victims' pleasure manifesting through ejaculation. Debates concerned views to whether male ejaculation is a consequence of pleasure or a physiological function (or both), and whether such victims are willing participants.

Male rape perpetuated by men?

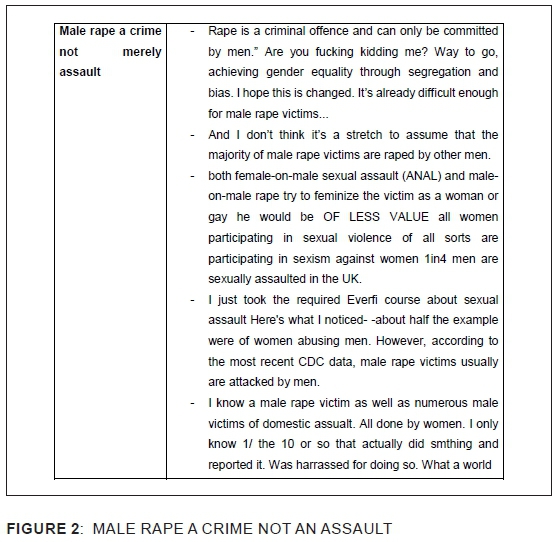

An oversimplified and narrow definition of male rape perceives male rape to be a weapon used by men against other men, and in instances of female-on-male rape, it was labelled assault and not rape. The fact that male rape lacks a standardised definition as a crime makes it difficult for focused online conversations about it to take place in isolation from discussions about other assault crimes. The risks that male rape victims face are attenuated through the muddling of discourses about crime.

In online spaces, it seems that the prevalence of male rape is comparatively discussed in relation to female rape cases and assault, perpetuating gendered discourses about related crimes suffered by women. There were also questions raised about the differences in legal sentences between male rape, murder, and female rape. The discussion of the classification of male rape in different societal laws presented it not as rape, but as an assault, even though the risks to the victims of the crime are those of rape, as are the legal consequences. The framing of rape in the law is seemingly informed by cultural influences on masculinity and the role of patriarchy in forming notions of what a male should be.

GENDERED ONLINE DISCOURSES

Gendered myths, 'societal indifference' and risk attenuation

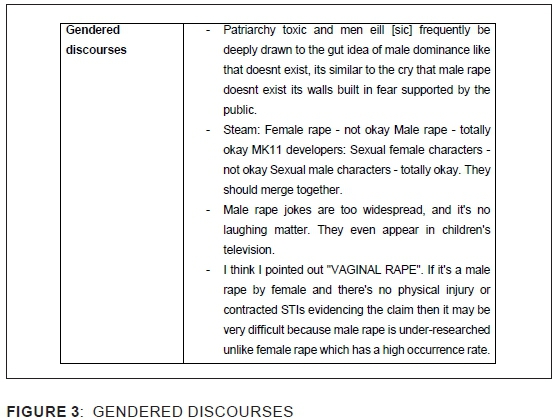

Societal values and norms are blamed in these Twitter conversations as being responsible for upholding gendered myths in discourses and perpetuating fears around male rape being discussed as a reality.

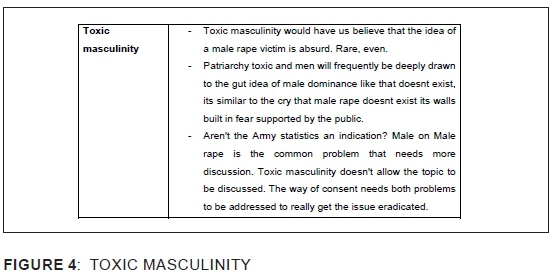

Toxic masculinity

Culture is embedded in online discourses on male rape and masculinity, and how it prevents male rape survivors from seeking help. The online discussions about male rape point towards toxic masculinity as being responsible for the attenuation of male rape by denying its existence and trivialising the risks associated with it. Toxic masculinity is considered responsible for the erasure of discourses about male rape and victimhood. Discomfort appeared to rise during discussions about representations of male rape displayed through traditional media, such as in movie scenes. However, discussions about toxic masculinity still appear to compound male rape with male dominance and male-on-male rape, shifting the focus away from victims of male rape.

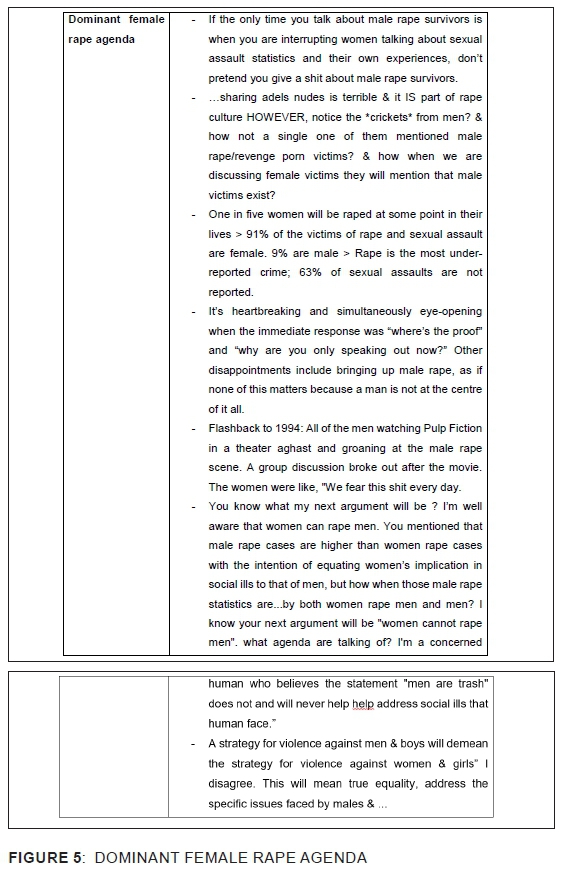

Dominance of the female rape agenda

Alongside toxic masculinity lies the notion of feminism with related perceptions of females as victims of rape in society, while males are considered the perpetrators. The tweets demonstrate that discussions could have been silenced on the basis of the de-legitimation of male rape and the assertion that the perpetrators of female rape are always male. A comparison of rape statistics is used to delegitimise male rape, as "proof" of who the "real" victims of rape are - female victims with a much higher rate of reported cases. Online discussions on the observed shock of audiences to a male rape scene in a movie were mocked and trivialised in relation to the "everyday" experiences and fears of women of being raped. There was further risk attenuation of male rape, questioning why male-to-male rape was being discussed more than female-to-male rape in the results of the Twitter search. Conversants, some vicious in their discussions, noted that conversations about male rape only arise when female rape is mentioned.

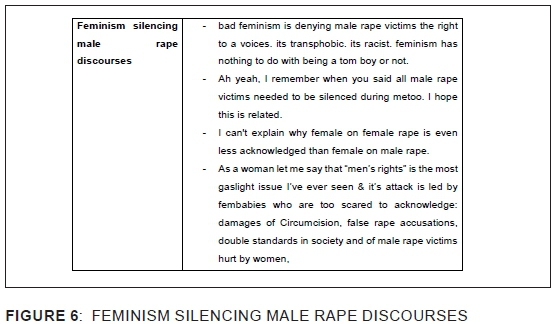

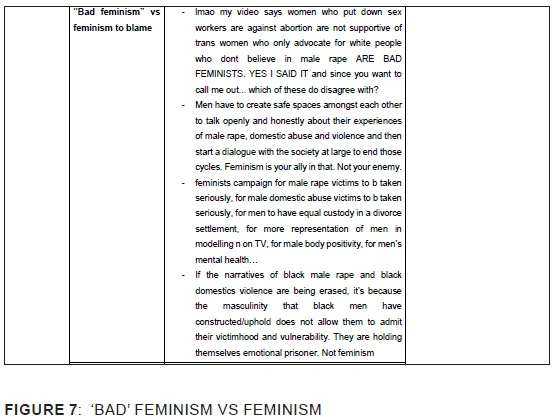

Others blamed feminism for silencing discussions about male rape.

A few dissenting voices noted that the blame placed on feminism is uncalled for and that feminism is an ally, not the enemy. Others pointed out that "bad feminism" should take the blame, rather than feminism.

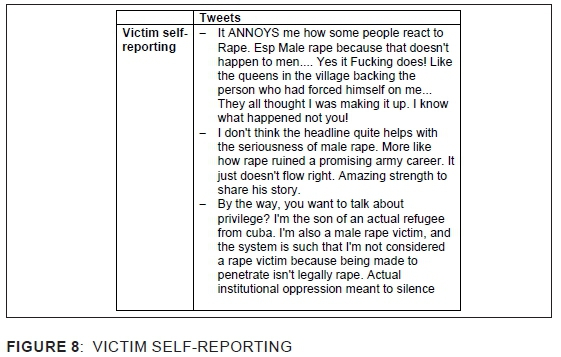

There were a few male voices discussing the victim's plight.

Other male voices were vicious in their observations about societal attitudes and perceptions towards male rape:

Female dominance was evident in the most prevalent words (Figure 10) from Twitter discussions on male rape, which were the terms "women", "female" and "woman".

OTHER FACTORS DRIVING SILENCE ABOUT MALE RAPE

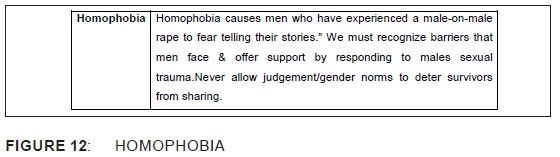

Apart from (bad) feminism, another factor identified as responsible for the silence about male rape was homophobia:

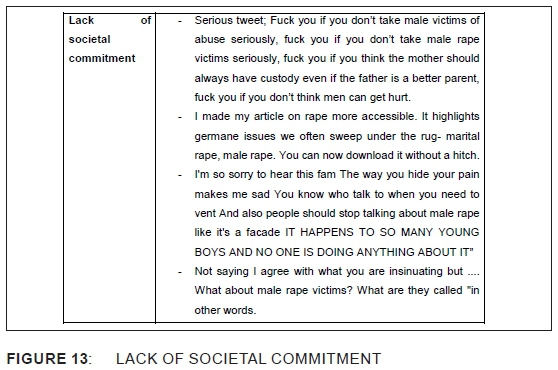

Others pointed out a lack of commitment by society to take male rape seriously.

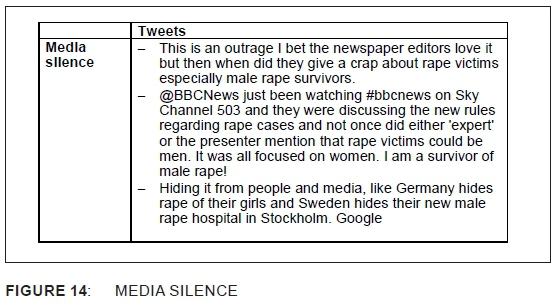

The media was blamed for focusing on female rape in their coverage, while disregarding stories about male rape. The tweets included accusations of the silence by the media about rape and an apparent agenda to keep conversations on rape focused only on women, to the exclusion of male rape. The media was also accused of deliberately hiding information from the public, and perpetuating a spiral of silence on issues of male rape, even when positive healthcare interventions for male rape victims, such as a dedicated hospital in Sweden, were introduced, which would be fodder for media coverage. The erasure of male rape from public discourses is blamed on the seeming lack of physical evidence of injury if female-to-male and the lack of research on the prevalence of male rape. This silence on male rape contributed to the risk attenuation of the issue in online discourses, where society is made immune to the risks through normalisation of certain risky behaviours in television programming. Most of the tweets centred on the passivity of society in acknowledging the risks of male rape, to the point of including it in children's programming, and the unemotional reports of its prevalence in films. The supporting evidence of the passivity was conversations on how the one male rape survivor, out of a number of female-to-male rape victims, was on the receiving end of harassment for reporting his experience.

The expectation about SNSs is that these are democratised spaces for discourse to take place on virtually any topic. It is a space that facilitated amplification of issues on male rape. Users have the advantage of online anonymity to gain access to communities and take advantage of the support available online. Twitter discourses on male rape, however, silence the victims and minimise the risks by comparing the prevalence of male rape to that of female rape, including negative social externalities, such as online bullying of male rape victims. Male rape is portrayed as enjoyable to victims, particularly female-to-male rape, which is considered as an opportunity to be sexually active. It appears through the tweets, that male rape victims are thought to "enjoy" male-on-male rape because of their physical reaction and are urged to consider female-on-male rape as a "privilege". This trivialises a traumatic experience, diminishes the risks to male rape victims, and attenuates the health risk consequences of the victims of this type of sexual assault. From these online discussion, male rape is not considered a serious form of sexual assault, and jokes about it are generally acceptable.

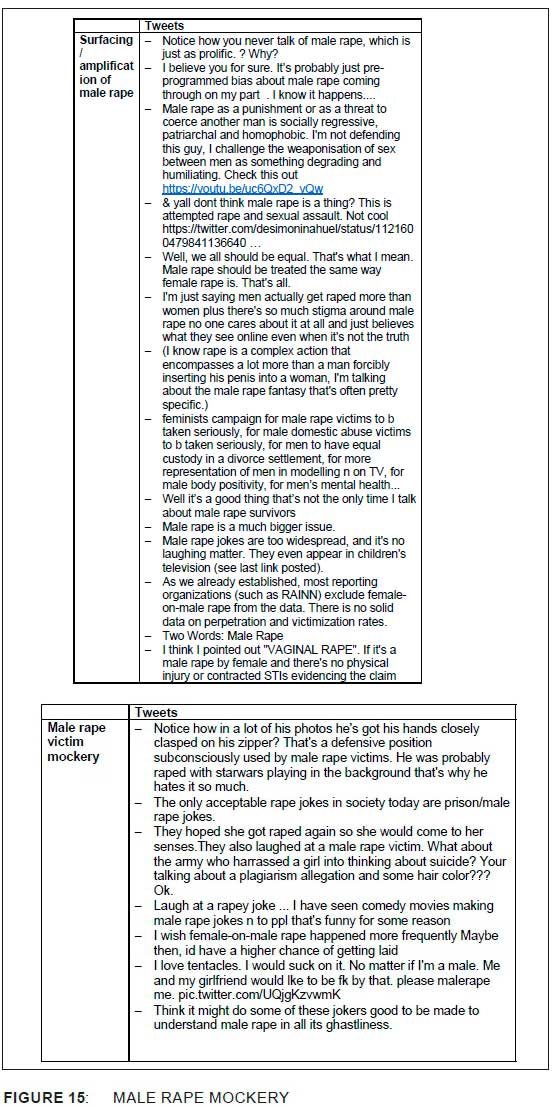

Male rape risk and mockery

Despite the significant volume of tweets making light of male rape and the risks involved for survivors, a section of the discussions was dedicated to highlighting the risks. The discourses revealed that male rape could be used as a tool of threat or coercion, pointing out the risks of male rape happening to a victim. The arguments are that male rape should be treated the same as female rape, in respect of the risks involved for victims.

CONCLUSION

While online spaces could, and have, effectively acted as platforms for the amplification of health issues, their success appears to be dependent on the type of issue involved. For example, while SNSs have enabled discussions and support for seropositive people, and facilitated disclosure and attenuated negative public perceptions about the disclosure, the same has not happened for male rape. Online discussions about male rape appear to be as rare, as those in offline spaces are often limited to NGOs that specifically deal with those issues or during awareness months dedicated to sexual assault. When these discussions do take place, they are volatile because of divided views about male rape; a matter that is accentuated by societal attitudes and perceptions towards the victims. Disclosure of an individual's HIV status has been a stigmatised and has been a controversial issue in society for decades, yet male rape, which has existed for centuries, has the potential to, but does not yet enjoy positive online developments. The reality of the full risks faced by male rape victims does not attract significant public attention, perhaps with the exception of public days of significance. Even then, the discussions are gendered, and sexual assault victims are reported with a female bias or a bias towards children.

Male rape is hardly supported both in online and in offline settings, which are simultaneous hotbeds of hegemonic representations of feminism and masculinity. Therein, male victims are considered subordinate and emasculated by men, but also undeserving by women, yet they too suffer a myriad of health problems including mental, emotional and physical. Male rape is a risk to society with opportunities for SNSs to play an important role in risk amplification, but at present, they are mainly tools reinforcing existing misconceptions. SNSs have also facilitated the silence of marginalised rape experiences. Male rape is suppressed by culture in some societies, which promote masculinity norms, and it is hardly acknowledged as a problem. Victims lack support systems, which has led to some of them committing suicide. Society should first acknowledge the problem in order to offer the necessary support.

Future studies could conduct online experiments exploring possible bystander effects on discourses of risky health issues, such as male rape. This study contributes to the few available studies on online discourses of male rape, in line with sexual assault awareness. Furthermore, it highlights the risks faced by male rape victims and survivors through the silencing of their experiences through media cultural resistance and feminism.

REFERENCES

Andersen, N. 2018. Shocking stats reveal 41% of rapes in SA are against children. [Online]. Available at: https://www.thesouthafrican.com/rape-statistics-41-children/ [Accessed on 22 January 2020]. [ Links ]

Best, P., Manktelow, R. & Taylor, B. 2014. Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Children and Youth Services Review 41: 27-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.001 [ Links ]

Boyd, D.M. & Ellison, N.B. 2007. Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of computer-mediated Communication 13(1): 210-230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x [ Links ]

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). 2018. Reported sex offences against males in England and Wales tripled in 10 years. BBC 2 February. [Online] Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-42906980 [Accessed on 22 January 2020]. [ Links ]

Cummings, C., Kubiak, S., Hawkins, J. & Buchanan, N. 2018. Providers' perceptions on barriers to help-seeking for male victims of sexual assault. Society for Social Work Research. [Online] Available at: https://sswr.confex.com/sswr/2018/webprogram/Paper33049.html. [Accessed on 22 January 2020]. [ Links ]

Davies, M. 2002. Male sexual assault victims: A selective review of the literature and implications for support services. Aggression and Violent Behavior 7: 203-214. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-1789(00)00043-4 [ Links ]

De Visser, R.O., Smith, A.M., Rissel, C.E., Richters, J. & Grulich, A.E. 2003. Sex in Australia: Experiences of sexual coercion among a representative sample of adults. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 27: 198-203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.2003.tb00808.x [ Links ]

Ferrales, G., Mcelrath, S. & Brehm, H.M. 2016. Gender-based violence against men and boys in Darfur: The gender-genocide nexus. Gender and Society 30(4): 565-589. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243216636331 [ Links ]

Garrett, R.K. 2009. Echo chambers online? Politically motivated selective exposure among Internet news users. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14(2): 265285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01440.x [ Links ]

Gearhart, S. & Zhang, W. 2015. 'Was it something I said?' 'No, it was something you posted!' A study of the spiral of silence theory in social media contexts. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 18(4): 208-213. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0443 [ Links ]

Hodges, E.V., Malone, M.J. & Perry, D.G. 1997. Individual risk and social risk as interacting determinants of victimization in the peer group. Developmental Psychology 33(6): 1032-1039. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.1032 [ Links ]

Javaid, A. 2015. Male rape myths: Understanding and explaining social attitudes surrounding male rape. Masculinities and Social Change 4(3): 270-294. https://doi.org/10.17583/mcs.2015.1579 [ Links ]

Javaid, A. 2017. The unknown victims: Hegemonic masculinity, masculinities, and male sexual victimisation. Sociological Research Online 22(1): 1-20. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.4155 [ Links ]

Johnson, E.O. 2018. 5 horrifying ways enslaved African men were sexually exploited and abused by their white masters. Face to Face Africa. 11 October. [Online] Available at: https://face2faceafrica.com/article/5-horrifying-ways-enslaved-african-men-were-sexually-exploited-and-abused-by-their-white-masters/2 [Accessed on 22 January 2020]. [ Links ]

Kasperson, R.E. 1992. The social amplification of risk: Progress in developing an integrative framework in social theories of risk. In: Krimsky, S. & Golding, D. (eds). Social theories of risk. New York: Praeger. [ Links ]

Kasperson, R.E. & Kasperson, J.X. 1996. The social amplification and attenuation of risk. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 545(1): 95-105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716296545001010 [ Links ]

Kozinets, R.V. 2002. The field behind the screen: Using netnography for marketing research in online communities. Journal of Marketing Research 39(1): 61-72. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.39.1.61.18935 [ Links ]

Kozinets, R.V. 2006. Click to connect: Netnography and tribal advertising. Journal of Advertising Research 46(3): 279-288. https://doi.org/10.2501/S0021849906060338 [ Links ]

Kozinets, R.V. 2015. Netnography: Redefined. London: Sage. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118767771.wbiedcs067 [ Links ]

Leonhard, L., Obermaier, M., Rueß, C., & Reinemann, C. 2018. Perceiving threat and feeling responsible. How severity of hate speech, number of bystanders, and prior reactions of others affect bystanders' intention to counter argue against hate speech on Facebook. Studies in Communication and Media 7(4): 555-579. https://doi.org/10.5771/2192-4007-2018-4-555 [ Links ]

Mann, R. 2015. Male rape still considered a joke in South Africa. Health24, 29 July. [Online] Available at: https://www.health24.com/Lifestyle/Man/Your-body/Male-rape-still-considered-a-joke-in-South-Africa-20150729 [Accessed on 22 January 2020]. [ Links ]

Matthes, J., Knoll, J. & Von Sikorski, C. 2013. The 'spiral of silence' revisited: A meta-analysis on the relationship between perceptions of opinion support and political opinion expression. Communication Research 45(1): 3-33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650217745429 [ Links ]

Noelle-Neumann, E. 1973. Return to the concept of the powerful mass media. Studies in Broadcasting 9: 67-112. [ Links ]

Noelle-Neumann, E. 1993. The spiral of silence: Public opinion - Our social skin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Pal, M. & Dutta, M.J. 2008. Public relations in a global context: The relevance of critical modernism as a theoretical lens. Journal of Public Relations Research 20(2): 159179. https://doi.org/10.1080/10627260801894280 [ Links ]

Reitz-Krueger, C.L., Mummert, S.J. & Troupe, S.M. 2017. Real men can't get raped: an examination of gendered rape myths and sexual assault among undergraduates. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research 9(4): 314-323. https://doi.org/10.1108/JACPR-06-2017-0303 [ Links ]

Sarathchandra, D. & McCright, A.M. 2017. The effects of media coverage of scientific retractions on risk perceptions. SAGE Open 7(2): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017709324 [ Links ]

South African Male Survivors of Sexual Abuse (SAMSOSA). 2019a. The sad reality. [Online]. Available at: http://www.samsosa.org/wp/the-sad-reality/ [Accessed on 22 January 2020]. [ Links ]

South African Male Survivors of Sexual Abuse (SAMSOSA). 2019b. The top 10 myths of male sexual abuse and rape. [Online]. Available at: http://www.samsosa.org/wp/the-top-10-myths-of-male-sexual-abuse-and-rape/ [Accessed on 22 January 2020]. [ Links ]

Scheufele, D.A. 2007. Spiral of silence theory. In: Donsbach, W. & Traugott, M.W. (eds). The SAGE Handbook of Public Opinion Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Schulz, A. & Rössler, P. 2012. The spiral of silence and the internet: selection of online content and the perception of the public opinion climate in computer-mediated communication environments. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 24(3): 346-367. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/eds022 [ Links ]

Storr, W. 2011. The rape of men: The darkest secret of war. The Guardian, 17 July. [Online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2011/jul/17/the-rape-of-men [Accessed on 12 January 2020]. [ Links ]

Taggart, T., Grewe, M.E., Conserve, D.F., Gliwa, C. & Isler, M.R. 2015. Social media and HIV: A systematic review of uses of social media in HIV communication. Journal of Medical Internet Research 17(11): e248. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4387 [ Links ]

Tewksbury, R. 2007. Effects of sexual assaults on men: Physical, mental and sexual consequences. International Journal of Men's Health 6(1): 22-35. https://doi.org/10.3149/jmh.0601.22 [ Links ]

The Lancet HIV. 2018. HIV status disclosure in a digital age. 5(6). [Online] Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanhiv/article/PIIS2352-3018(18)30109-7/fulltext. [Accessed on 20 January 2020]. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30109-7 [ Links ]

Vaglanos, A. 2017. Men try to guess if these situations are porn or #MeToo stories. Huffington Post. [ Links ]

Xun, J. & Reynolds, J. 2010. Applying netnography to market research: The case of the online forum. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing 18(1): 17-31. https://doi.org/10.1057/jt.2009.29 [ Links ]

Young, I., Davis, M., Flowers, P. & McDaid, L.M. 2019. Navigating HIV citizenship: identities, risks and biological citizenship in the treatment as prevention era. Health, Risk and Society 21(1-2): 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2019.1572869 [ Links ]

Young, S.M., Pruett, J.A. & Colvin, M.L. 2016. Comparing help-seeking behavior of male and female survivors of sexual assault: A content analysis of a hotline. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063216677785 [ Links ]

Zerback, T. & Fawzi. N. 2017. Can online exemplars trigger a spiral of silence? Examining the effects of exemplar opinions on perceptions of public opinion and speaking out. NewMedia & Society 19(7): 1034-1051. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815625942 [ Links ]

Date submitted: 12 February 2020

Date accepted: 04 September 2020

Date published: 29 December 2020