Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Communitas

On-line version ISSN 2415-0525

Print version ISSN 1023-0556

Communitas (Bloemfontein. Online) vol.25 Bloemfontein 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150525/comm.v25.6

ARTICLES

Fictional spokes-characters in brand advertisements and communication: a consumer's perspective

Vuyelwa Constance MashwamaI; Dr Tinashe ChuchuII; Dr Eugine Tafadzwa MaziririIII

ISchool of Business Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa Email: vmashwama@gmail.com ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7554-9693

IIDepartment of Marketing Management, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa Email: tinashe.chuchu@up.ac.za (corresponding author); ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7325-8932

IIIDepartment of Business Management, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa Email: maziririet@ufs.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8047-4702

ABSTRACT

Fictional spokes-characters in promotion and marketing communication are becoming more popular with brands. This study examined the impact spokes-characters have on the brands they endorse. Celebrities have been used as endorsers since the late nineteenth century and marketers have established that they are one of the most effective methods of advertising. The popularity of celebrity endorsements springs from the numerous benefits that companies experience by employing them. The contribution of this study is in addressing an area in marketing that looks at consumer perceptions of spokes-characters, how these consumer views influence their perceptions of advertisements and brands that use spokes-characters, and ultimately the influence on purchase intention. The study surveyed 260 consumers in the Braamfontein business district of Johannesburg, South Africa. The study found that consumers are in favour of spokes-characters and advertisements that use spokes-characters. Moreover, the researchers concluded that only a spokes-character's attractiveness and expertise influence attitudes toward the advertisement and a spokes-character's trust influences attitudes toward the brand. In addition, the study found that individually, both attitude variables have a positive effect on purchase; however, the relationship between the attitude towards the advertisement and the attitude towards the brand tended to be stronger.

Keywords: spokes-character; brand communication; marketing communication; credibility; advertising; consumers

INTRODUCTION

A Actional spokes-character is an animated being or animated object that is used to promote or communicate product benefits, service features, or a concept (Phillips et al. 2019). Spokes-characters have been a frequently used promotional and marketing communication tool over the years (Phillips et al. 2019). The use of spokes-characters grew in media consideration, with hour-long television programmes dedicated to addressing their potential benefits to brands (Garretson & Niedrich 2004). More recent research (Kim et al. 2018) investigated the persuasive effects of fictional brand characters. When an advertisement is effective, the audience notices, recalls and thinks about the message in the advertisement and eventually considers purchasing the product.

Advertising is any paid form of non-personal communication in an attempt to build awareness, inform, persuade and remind the target market about the product/service offering by an identified sponsor (Kotler & Keller 2009). Over the years, marketers have used many persuasive advertising techniques to increase consumer advertising interest in their advertisements; one of the techniques was the concept of brand endorsement through the use of celebrities (Bekk & Spörrle 2010; Ndlela & Chuchu 2016). Endorsement is a channel of brand communication where the endorser, who has already developed benevolence in the market, endorses a product and acts as a connection between the product and the consumer (Manjusha & Segar 2013). Four categories of endorsers have been identified, namely celebrities, employees, spokes-characters and customers (Joghee & Kabiraj 2013). According to Patel (2009), marketers use mostly celebrity endorsement. Advertisers believe that because of their popularity, celebrities do not only create and maintain attention, but also achieve high recall rates for marketing communication messages (Erdogan 1999). However, a company using a celebrity always runs the risk of the brand being influenced by the celebrity's professional and personal life, which cannot be controlled, and sometimes, the effect could be negative.

In recent years there has an increase in the use of created animated spokes-characters as endorsers due to technological developments in animation (Stafford et al. 2013). According to Garretson and Niedrich (2013), spokes-characters have been used by firms since the late 1800s to establish brand identity and favourable brand associations. These characters could be fictitious human spokes-characters or non-human spokes-characters, such as animals, mythical beings (e.g. fairies), or product personifications (Callcott & Lee 1995).

This study examines non-celebrity spokes-characters solely created to promote a brand or product rather than those who were originally created for animated movies, cartoons and/or comic strips, and then licensed by brands to appear in promotions. Fictional spokes-characters are an appealing and safe alternative to human endorsers because marketers have greater control over characteristics that are both effective with the target audience and congruent with the desirable characteristics of the endorsed product (Stafford et al. 2013). Animated spokes-characters do not fall prey to the many challenges inherent in human celebrities; they are not likely to humiliate sponsors with their off-stage behaviour; thus, negatively affecting endorsed brands (Stafford et al. 2013). Although much research has been done on celebrity endorsement, some studies indicate that there is still doubt whether endorsements are effective - either via created or celebrity endorsers (McEwen 2003). There is limited literature on created spokes-characters, who are not celebrities, which are used to endorse brands (Van der Waldt et al. 2009), especially in the South African context, that has mainly focused on how perceived spokes-character credibility (trustworthiness, attractiveness and expertise) influences attitudes toward the advertisement and attitudes towards the brand. In addition, studies conducted in the past have mainly focused on these characters as endorsers for products targeted at children (Boyland et al. 2012; Mizerski 1995; Kelly et al. 2008). This study focuses mainly on the use of created non-celebrity spokes-characters as brand endorsers for products targeted at consumers over the age of 18.

When a celebrity has a good image and fit for the product and company, this will lead to greater believability, and thus effectiveness. By uniting these aspects, you create two advantages, working together for the product and the endorser. This is the kind of fit the company wants to achieve; hence, the endorsement (Kim 2012). Conversely, if the image of the celebrity changes and no longer matches the product and company, this could lead to financial loss and a major dilemma if the endorsement was a long-term contract (Raluca 2012). Also, celebrities come and go, and their fame fluctuates (Prasad 2013). Additionally, when a celebrity endorses multiple products, the endorsement effect loses its strength (Kim 2012). Moreover, celebrity endorsement can be costly. Prasad (2013) states that in 2001, IEG Endorsement Insider, an advertising trade publication, estimated that celebrities directly received more than $800 million in endorsements in 2001. According to Kotler and Keller (2009), a celebrity might hold out for a large fee at contract renewal time, or withdraw, and celebrity campaigns can sometimes be expensive failures.

On the other hand, created spokespersons can be controlled to a greater degree, and they are less costly than celebrities (Van der Waldt et al. 2009). In addition, consumers notice and watch advertisements featuring created spokes-characters more than other advertisements (Jayswal & Panchal 2012). If created spokes-characters' endorsements have longevity, they will be effective as long as the method is successful for the organisation. However, human celebrity endorsers have limited longevity. For an endorsement to be successful, there must a celebrity-product fit supported by the match-up hypothesis model (Amos et al. 2008). In reference to spokes-characters, marketers are able to create a better fit between the endorser and product because these characters are self-created by companies and customised to fit the brand (Jayswal & Panchal 2012). In a nutshell, the risk inherent in utilising celebrity endorsements could be addressed by making use of created spokes-characters.

Celebrity endorsements have proven to be effective and organisations have used celebrities to pursue their target market to create positive purchase aspirations or change their behaviour (Van der Waldt et al. 2009). One of the concerns stated above is that sometimes consumers will focus on the celebrity and fail to notice the brand being promoted, called overshadowing, resulting in lack of clarity for the consumer and additionally diminishing the image and associations between the celebrity and the brand (Temperley & Tangen 2006). According to Kim (2012), overshadowing is caused mainly by the heightened attention drawn to celebrities in many types of commercials; hence, a general lack of interest in assessing the merits of the product, which could result in reduction of brand recognition. This is likely to occur when an advertisement featuring celebrity endorsers focuses on the celebrity rather than on the products. Amos et al. (2008) argue that there needs to be a strong association between the brand and the celebrity before negative information about the celebrity could have a major effect on the perceptions of the brand.

RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

The purpose of this study is to establish the extent to which the spokes-character's expertise, trustworthiness and attractiveness will influence consumers' attitudes towards the brand, as well as consumers' attitudes towards the spokes-character. The specific research objectives are as follows:

♦ to examine the plausible use of spokes-characters instead of celebrities as endorsers;

♦ to determine the influence of the spokes-character's credibility on the consumer's attitude towards the advertisement;

♦ to assess the influence of the spokes-character's credibility on the consumer's attitude towards the brand/product;

♦ to determine the relationship of the consumer's attitude towards the advertisement and purchase intention;

♦ to examine the relationship of the consumer's attitude towards the brand and purchase intention; and

♦ to assess the relationship between the consumer's attitude towards the advertisement and the attitude towards the brand and purchase intention.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Consumer intention to purchase

Khan et al. (2012) define purchase intention as an individual's aim to buy a specific brand, which they have chosen after a certain evaluation process. Tariq et al. (2013) states that purchase intention relates to four behaviours of consumers, namely the definite plan to buy the product, thinking explicitly of purchasing the product, when someone contemplates to buy the product in the future, and to buy the specific product. Chinomona and Sandada (2013) explain that the intention by consumers to purchase reflects their interest in the product and hence their willingness to buy the product or service. Khan et al. (2012) depict brand knowledge, brand relationship, behavioural intention, brand advertisement and past experience about the brand as factors in the purchase intention of consumers. Chinomona and Sandada (2013) provide the elements that can be used to measure purchase intent, namely the probability of a consumer considering buying the product, the consumer's willingness to, and the likelihood of a consumer's purchase behaviour. According to Schiffman et al. (2010), purchase intention can be measured using factors such as, 1) the consumer will definitely buy the product/brand; 2) the probability that the consumer will purchase the product/brand; 3) the consumer's uncertainty over whether they will buy the product/ brand; 4) the probability the consumer will not buy the product/brand; and 5) the consumer will definitely not buy the product/brand.

Attitude towards the brand

Attitude towards the brand refers to audiences' emotional reaction to the advertised brand. That is, to what extent audiences feel purchasing the brand is good/bad, favorable/unfavourable, or wise/foolish. Ghorban (2012) describes attitude as an achievable, relatively permanent, and at the same time purposeful, gradual, and motivated intention to react to a particular object; for example, a brand or advertisement. Attitude can be positive or negative and can be changed if people gain new experiences. Schiffman et al. (2010) state that according to the attitude-toward-object model, consumers will have a positive attitude towards a brand that they believe has an adequate level of attributes they view as positive, and have unfavourable attitudes toward a brand that they perceive as having too many undesired attributes. In measuring attitude, Ghorban (2012) used two items: favourable to unfavourable, and like to dislike. In measuring attitude towards brands amongst children, Schiffman et al. (2010) used two items, namely definitely agreeing to definitely disagreeing to describe the brand as fun, great, useful, practical or useless.

Attitude towards advertisement

This can be defined as the set of thoughts and feelings consumers have about an advertisement. Attitude towards advertising can also be seen as the way a targeted consumer responds in either a favourable or unfavourable manner towards a specific advertisement during the exposure. Consumers will be involved with an advertisement based on the degree of attention and the processing strategy. It is widely accepted that ad cognitions or antecedents, also called ad perceptions, have a direct positive effect on attitude towards the advertisement (Lutz et al. 1983; MacKenzie et al. 1986). Ad cognitions can be defined as the consumer's belief in the advertising stimulus. The determining factors of ad cognitions are 1) the ad characteristics; 2) the consumer's attitude toward the advertiser; and 3) conscious processing of executional elements (Najmi et al. 2012).

CONCEPTUAL MODEL AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

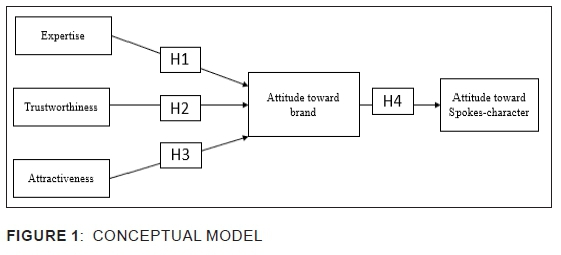

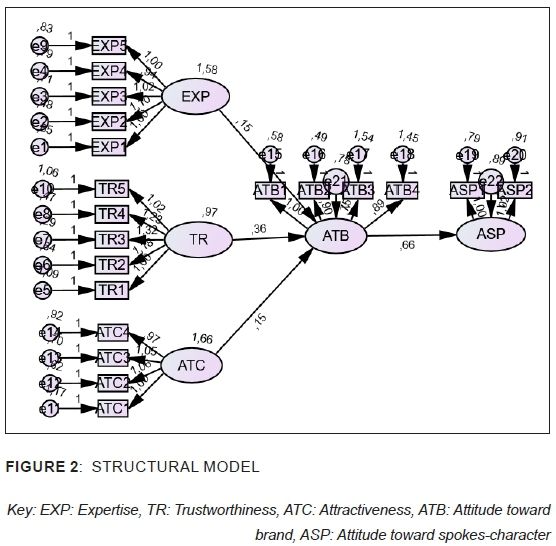

In order to test empirically the relationships between the study variables, the conceptual model in Figure 1 was developed premised on the reviewed literature. In this conceptual model the spokes-character's expertise, trustworthiness and attractiveness are the predictor variables, while the consumer's attitude towards the brand is the mediator. The consumer's attitude towards the spokes-character is the outcome variable. Detailed accounts of the links between these variables are provided in the next section on hypotheses developed from the model.

Hypotheses development

Expertise

Pornpitakpan (2004a) defines expertise as the extent to which a speaker is perceived to be capable of making a correct assertion of the brand. Garretson and Niedrich (2004) define it as the perception that a source is able to make valid claims or has knowledge of the product. These authors (ibid.) state that spokes-characters have made numerous product claims and have done so repeatedly from campaign to campaign and as result consumers can perceive spokes-characters as experts. Kim (2012) proposes that expert endorsers are more effective in increasing brand evaluations than celebrities in terms of technology gadgets and among consumers with more product knowledge. Additionally, a source high in expertise appears to lead to positive attitudes toward the endorser and the advertisement; also, expert endorsers induce more positive product/ brand quality ratings than celebrities (Pornpitakpan 2004b). A source/celebrity who is more of an expert has been found to be more persuasive and to generate more intentions to buy the brand (Ohanian 1991). Thus, it can be hypothesised that:

H1: There is a relationship between expertise of the spokes-character and consumer attitude toward the brand.

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness is the degree of confidence that the respondent has in the communicator's intentions and ability to make valid assertion. Garretson and Niedrich (2004) refer to spokes-character trustworthiness as the expectation that the character will be honest, sincere and reliable in their communication and promotion of products. In a comparison study between celebrity endorsers and created endorsers, Van der Waldt et al. (2009) concluded that neither celebrities nor created endorsers were perceived to be more trustworthy or to possess more expertise than the other. According to Amos et al. (2008), a highly opinionated message from a highly trustworthy communicator produces an effective attitude change, while non-trusted communicators' impact proved immaterial. Kim (2012) concludes that perceived endorser trustworthiness appears to produce a greater attitude change than perceived expertise. Amos et al. (2008) suggest that trustworthiness is an important predictor of endorsement effectiveness. Thus, it can be hypothesised that:

H2: There is a relationship between the trustworthiness of the spokes-character and consumer attitude toward the brand.

Attractiveness

Physically appealing endorsers influence the effectiveness of the advertising message and intent to purchase (Keel & Nataraajan 2012). The inclusion of attractiveness was prompted by research, suggesting that a physically attractive communicator is liked more and has a positive impact on opinion change and product evaluations (Goldsmith et al. 2000). According to Till and Busler (2000), attractive celebrities are more effective endorsers for products, which are used to enhance one's attractiveness; thus, leading to higher brand attitude and purchase intentions. Advertisers have associated attractive endorsers with their brands because they are imbued with not only physically attractiveness but also positive traits such as social competence, intellectual competence, concern for others, and integrity (Till & Busler 2000). Thus, it can be hypothesised that:

H3: There is a relationship between the trustworthiness of the spokes-character and consumer attitude toward the brand.

Attitude towards brand

Attitude towards brand is the recipients' affective reactions toward the advertised brand or where there is a desirable attitude towards purchasing the brand (Lutz et al. 1983). Brand beliefs and feelings are formed through advertising and these beliefs affect attitudes towards advertisements and consequently attitudes towards the brands being advertised. Previous research has shown that attitudes toward advertisements have direct effects on brand attitudes and subsequently on purchase intentions (Suh & Yi 2006; Mackenzie et al. 1986). Frequent exposure of a trade character would cause high recognition of the trade character and the product; it also leads to favourable attitudes towards the product/brand, and influences the consumer to use the product/ brand in future. Additionally, animated spokes-characters reduce the distance between companies and consumers; that is, they encourage consumers' liking for the spokes-character, which is extended to the brand and its products (Huang et al. 2013). What is more, commercials featuring animated characters were watched more often than other types of commercials and the attitude towards the brand is affected by a spokes-character's likability. Jayswal and Panchal (2012) propose that cartoon spokes-characters are more creative and consumers display more positive responses for attitude towards advertisements, attitude towards brand, and purchase intention when compared to a human spokesperson. Lutz et al. (1983) posit that the recipients of an advertising message develop an attitude towards the advertisement, which in turn exerts an influence on subsequent measures of advertising effectiveness, such as brand attitude and purchase intentions. Ghorban (2012) asserts that after attitude towards advertisements is formed, it would affect different behaviour, such as brand attitude and purchasing intention. Drawing from the preceding theoretical discussion and in line with the empirical evidence on consumer attitude towards an advertisement and consumer intention to purchase, this study hypothesises that:

H4: There is a relationship between consumer attitude towards the brand and attitude towards the spokes-character.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Research design

The research was quantitative in nature. It adopted the positivist philosophy, as it was imperative to obtain objective findings. Due to the inability to obtain a sampling frame, the research therefore utilised convenience sampling, a form of non-probability sampling, to select suitable participants. Data collection was conducted in Braamfontein, a business district in Johannesburg, South Africa over a two-month period. A total of 260 responses were received from willing participants regarding the impact of spokes-characters in brand advertisements and communication. After the data was collected, it was processed for descriptive statistics through the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS) 26, while structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted through the analysis of moment structures software (AMOS) 26. Descriptive statistics provided the sample's profile, while SEM was done in order to test the proposed hypothesised relationships.

Ethical considerations

Prior to the data collection, the researchers applied for ethical clearance at the University of the Witwatersrand (CBUSE/1026). Participation in the research was voluntary and anonymous, and the participants were permitted to withdraw from the study at any time.

RESULTS

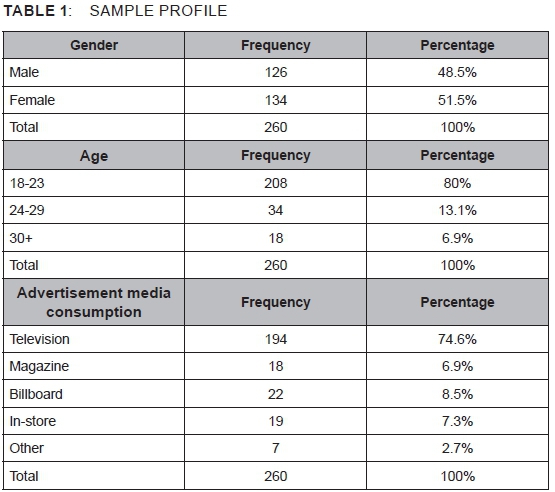

Table 1 presents the sample profile. It can be observed that male and female participants were fairly distributed, while most of the participants were in the 18 to 23 age category. The participants, 30 or older, were the least represented. As for the participants' advertisement media consumption, it is indicated that most of them were exposed to spokes-characters through television, as indicated by over 74%, while magazines, billboards, in-store advertisements and other media forms accounted for 6.9%, 8.5%, 7.3% and 2.7% respectively.

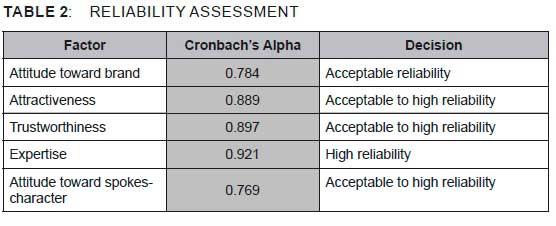

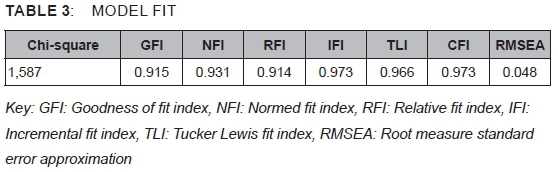

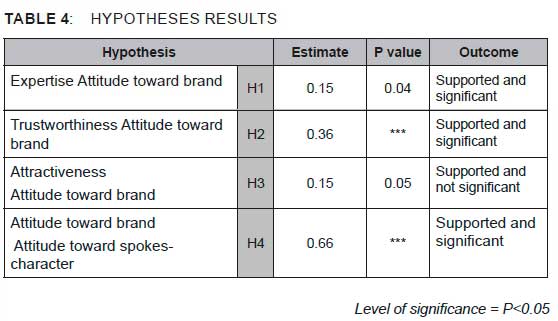

Prior to any analysis concerning the conceptual model, all constructs were checked for reliability through the Cronbach's alpha. As indicated in Table 2, all constructs were above the recommended 0.60 threshold necessary for reliability. Thereafter, model fit was checked, as indicated in Table 3, followed by the structural model in Figure 2. In order to test the proposed hypotheses, structural equation modeling was conducted in a two-part procedure, which involved assessing for model fit through confirmatory factor analysis (see Table 3 for results) and then the actual testing of hypotheses (see Figure 2 and Table 4 for results).

Table 3 presents the model fit assessment for the study. It is observed that the model met the required threshold of 0.900 or higher. The results are as follows: goodness of fit (0.915), normed fit (0.931), relative fit (0.914), incremental fit (0.973), Tucker Lewis (0.966), and confirmatory fit (0.973). This means that the data and model were both suitable for hypotheses testing in order to establish whether proposed assumptions in relation to consumers' perceptions of spokes-characters in advertising were either confirmed or rejected.

Figure 2 presents the structural model for the study. It illustrates the influence that the three predictors (expertise, trustworthiness and attractiveness) have on attitude towards brand. In turn, attitude towards brand is depicted as both an antecedent of attitude toward spokes-character (outcome) and a mediator between the predictors and the outcome. It is observed that the strongest predictor was trustworthiness and the strongest of all relationships was that of attitude toward brand and attitude toward spokes-character.

The results of the hypotheses are presented in Table 4. It is evident that all of the hypotheses were both supported and significant at P<0.05, apart from H3.

The first hypothesis (expertise and attitude toward brand): this relationship was found to be both supported and significant at P<0.05, as it had a p value of 0.04 and an estimate of 0.15. This suggests that the more consumers perceive the brand's spokes-person to be an expert, the more their attitude towards that spokes-person become positive.

The second hypothesis (trustworthiness and attitude toward brand): this relationship is both supported and significant at P<0.05, as it had a p value of below 0.01, as indicated by the asterisks (***) and an estimate of 0.36. This means that if consumers trust the brand's spokes-character they are more likely to develop a positive attitude toward the brand.

The third hypothesis (attractiveness and attitude toward brand): this relationship is also supported by the proposed hypothesis; however, it was found not to be significant. This could therefore mean that the consumers could consider the attractiveness of brand's spokes-person to be relevant but not necessarily significant to influence their attitude toward the brand.

The fourth hypothesis (attitude toward brand and attitude toward spokes-person): it is observed that these two factors are related. They are both supported and significant at P<0.05 with an estimate of 0.66 making this hypothesis the strongest of all four relationships. This finding suggests that consumers closely associate a spokes-character with the brand represented by that spokes-character. In other words, if the spokes-character is perceived negatively, the consumers will in turn also perceive that brand in a negative light and, conversely, if consumers perceive the spokes-character positively, they will also perceive the brand positively.

IMPLICATIONS

A number of managerial and research implications emerged from the findings of the study. First, on the managerial front, it was established that trustworthiness had the most influence on attitude towards a brand. This implies that marketers and managers should prioritise making a fictional spokes-character credible, as this is the most important factor that impacts attitude towards a brand. This suggests that the other factors, expertise and attractiveness, have a weaker influence on consumers' attitude towards a brand. In other words, marketers can invest less on attractiveness and making the spoke-character appear to be an expert. This is because if consumers cannot trust a spokes-person, none of the other factors matter to them. In fact, with an estimate of 0.36, the relationship between trustworthiness and attitude towards brand was twice as important as that of expertise and attitude towards brand, and expertise and attitude towards brand, as they both had an estimate of 0.15.

In terms of research implications, it is noteworthy that the relationship between attitude towards brand and attitude towards spokes-person was considered more important than all the other relationships, with an estimate of 0.66. This means that researchers should attempt to determine why consumers associated attitude towards a brand so much with attitude towards its spokes-character. This could also help explain the extent of the importance of a spokes-character in the eyes of a consumer. In addition, expertise and attractiveness having such a weak impact on attitude towards a brand calls for researchers to investigate why that is the case. Overall, it is imperative for researchers and managers to investigate the best ways of making consumers believe a fictional spokes-character in the same way they would a natural one.

CONCLUSION

It can be concluded that though profitable, the effectiveness of a celebrity endorser is moderated by several factors such as the fit between the celebrity and the endorsed product/brand, the perceived attractiveness of the celebrity, the number of endorsements the celebrity is involved with, the characteristics of the target audience and the type of message, and the level of involvement that consumers have with regards to the message. Above and beyond these factors, the economic costs and potential risk inherent in using a celebrity should all be considered when companies decide to use celebrities as endorsers. As a solution to these challenges, this article investigated the plausibility of using a spokes-character. It can be concluded from the literature review that they are an effective tool because they are a safer and cheaper alternative, which marketers can self-develop and imbue with qualities that will be in line with the brand personality; thus, increasing the endorser product fit. From the analysis of the proposed conceptual model, the source credibility model provides an understanding of the factors that can influence the perceived credibility of a message source and thus the effectiveness of the source. Furthermore, it gives an indication as to which traits of the source have an influence on attitude towards advertisement and attitude towards brand, which will ultimately have an effect on purchase behaviour.

Suggestions for further research

This research contributed to understanding consumer perceptions of the influence of fictional spokes-characters in advertising communication. This was empirically tested through a conceptual model that made use of three antecedents of attitude towards brand (expertise, trustworthiness and attractiveness). Furthermore, the conceptual model tested the impact that consumer attitudes towards a brand had on the brand's spokes-character.

In terms of limitations, the study did not take into consideration the participants' socioeconomic status. It also did not consider the ethnic and cultural backgrounds of the participants. Analysing such issues could possibly have provided much richer results, as this could have revealed underlying stereotypes that people might hold toward the use of spokes-characters in advertisement messages. Hence, this would be recommended for further research. In addition, further research could make conceptual contributions to this study. This could take the form of empirically potential hypotheses left out in this study - for example, the relationship between expertise and trustworthiness, or a direct relationship between attractiveness and attitudes toward Actional spokes-characters. This could help explain the extent to which advertising messages depend on the attractiveness and perceived expertise of the spokes-character.

REFERENCES

Amos, C., Holmes, G. & Strutton, D. 2008. Exploring the relationship between celebrity endorser effects and advertising effectiveness: A quantitative synthesis of effect size. International Journal of Advertising 27(2): 209-234. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2008.11073052 [ Links ]

Bekk, M. & Spörrle, M. 2010. The influence of perceived personality characteristics on positive attitude towards and suitability of a celebrity as a marketing campaign endorser. The Open Psychology Journal 3(1): 54-66. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874350101003010054 [ Links ]

Boyland, E.J., Harrold, J.A., Kirkham, T.C. & Halford, J.C. 2012. Persuasive techniques used in television advertisements to market foods to UK children. Appetite 58(2): 658-664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.11.017 [ Links ]

Callcott, M.F. & Lee, W.N. 1995. Establishing the spokes-character in academic inquiry: historical overview and framework for definition. Advances in consumer research 22: 144-144. [ Links ]

Chinomona, R. & Sandada, M. 2013. Customer satisfaction, trust and loyalty as predictors of customer intention to re-purchase South African retailing industry. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 4(14): 437. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n14p437 [ Links ]

Erdogan, B.Z. 1999. Celebrity endorsement: A literature review. Journal of Marketing Management 15(4): 291-314. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725799784870379 [ Links ]

Garretson, J.A. & Niedrich, R.W. 2004. Spokes-characters: Creating character trust and positive brand attitudes. Journal of advertising 33(2): 25-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2004.10639159 [ Links ]

Ghorban, Z.S. 2012. Brand attitude, its antecedents and consequences. Investigation into smartphone brands in Malaysia. Journal of Business and Management 2(3): 31-35. https://doi.org/10.9790/487X-0233135 [ Links ]

Goldsmith, R.E., Lafferty, B.A. & Newell, S.J. 2000. The impact of corporate credibility and celebrity credibility on consumer reaction to advertisements and brands. Journal of advertising 29(3): 43-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2000.10673616 [ Links ]

Huang, T.Y., Hu, J.S. & Wu, W.R. 2013. The strategy of spokescharacters in consumption experience and brand awareness. Storage Management Solutions (2): 36-64. [ Links ]

Jayswal, R.M. & Panchal, P.K. 2012. An empirical examination of celebrity versus created animated spokes-characters endorsements in print advertisement among youth. Asian Journal of Research in Business Economics and Management 2(2): 71-85. [ Links ]

Joghee, S. & Kabiraj, S. 2013. Innovation in product promotions: A case of intended use of characters in the Chinese market. Innovation 5(1): 120-130. [ Links ]

Keel, A. & Nataraajan, R. 2012. Celebrity endorsements and beyond: New avenues for celebrity branding. Psychology & Marketing 29(9): 690-703. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20555 [ Links ]

Kelly, B., Hattersley, L., King, L. & Flood, V. 2008. Persuasive food marketing to children: use of cartoons and competitions in Australian commercial television advertisements. Health Promotion International 23(4): 337-344. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dan023 [ Links ]

Khan, I., Ghauri, T.A. & Majeed, S. 2012. Impact of brand related attributes on purchase intention of customers. A study about the customers of Punjab, Pakistan. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business 4(3): 194-200. [ Links ]

Kim, T. 2012. Consumers' correspondence inference on celebrity endorsers: The role of correspondence bias and suspicion. Unpublished doctoral thesis. The University of Tennessee, Knoxville. [ Links ]

Kim, W.H., Kim, H.J. & Choi, H.L. 2018. The persuasive effects of Actional brand character: Consumers' brand attitudes to fictionality. Indian Journal of Public Health Research & Development 9(8): 1041-1046. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-5506.2018.00868.9 [ Links ]

Kotler, P. & Keller, K.L. 2009. Marketing Management. (Thirteenth edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. [ Links ]

Lutz, R.J., MacKenzie, S.B. & Belch, G.E. 1983. Attitude toward the ad as a mediator of advertising effectiveness: Determinants and consequences. Advances in Consumer Research 10(1): 532-539. [ Links ]

MacKenzie, S.B., Lutz R.J. & Belch, G.E. 1986. The role of attitude toward the ad as advertising effectiveness: a test of competing explanation. Journal of Marketing Research 23(2): 30-143. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378602300205 [ Links ]

Manjusha, T.V. & Segar, D. 2013. A study on impact of celebrity endorsements and overall brand which influence consumers' purchase intention with a special reference to Chennai City. International Journal of Marketing, Financial Services & Management Research 2(9): 78-85. [ Links ]

McEwen, W.J. 2003. When the stars don't shine. GALLUP Management Journal. [Online]. Available at: http://gmj.gallup.com [Accessed on 29 March 2019]. [ Links ]

Mizerski, R. 1995. The relationship between cartoon trade character recognition and attitude toward product category in young children. The Journal of Marketing 59(4): 58-70. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299505900405 [ Links ]

Najmi, M., Atefi, Y. & Mirbagheri, S. 2012. Attitude toward brand: An integrative look at mediators and moderators. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal 16(1): 111-133. [ Links ]

Ndlela, T. & Chuchu, T. 2016. Celebrity endorsement advertising: Brand awareness, brand recall, brand loyalty as antecedence of South African young consumers' purchase behaviour. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies 8(2): 79-90. https://doi.org/10.22610/jebs.v8i2(J).1256 [ Links ]

Ohanian, R. 1991. The impact of celebrity endorsement spokespersons' perceived image on consumers' intention to purchase. Journal of Advertising Research 31(1): 46-54. [ Links ]

Patel, P. 2009. Impact of celebrity endorsement on brand acceptance. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 4(1): 36-45. [ Links ]

Phillips, B.J., Sedgewick, J.R. & Slobodzian, A.D. 2019. Spokes-characters in print advertising: An update and extension. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 40(2): 214-228. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2018.1503110 [ Links ]

Pornpitakpan, C. 2004a. The effect of celebrity endorsers' perceived credibility on product purchase intention: The case of Singaporeans. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 16(2): 55-74. https://doi.org/10.1300/J046v16n02_04 [ Links ]

Pornpitakpan, C. 2004b. The persuasiveness of source credibility: A critical review of five decades' evidence. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 34(2): 243-281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02547.x [ Links ]

Prasad, C.J. 2013. Brand endorsement by celebrities impacts towards customer satisfaction. African Journal of Business Management 7(36): 3630-3635. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM11.2571 [ Links ]

Schiffman, L.G., Kanuk, L.L. & Wisenblit, J. 2010. Consumer Behaviour. (Tenth edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. [ Links ]

Stafford, M.R., Stafford, T.F. & Day, E. 2002. A contingency approach: The effects of spokesperson type and service type on service advertising perceptions. Journal of Advertising 31(2): 17-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2002.10673664 [ Links ]

Suh, J. & Yi, Y. 2006. When brand attitudes affect the customer satisfaction-loyalty relation: The moderating role of product involvement. Journal of Consumer Psychology 16(2): 145-155. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1602_5 [ Links ]

Temperley, J. & Tangen, D. 2006. The Pinocchio factor in consumer attitudes towards celebrity endorsement: Celebrity endorsement, the Reebok brand, and an examination of a recent campaign. Innovative Marketing 2(3): 97-111. [ Links ]

Till, B.D. & Busler, M. 2000. The match-up hypothesis: Physical attractiveness, expertise, and the role of fit on brand attitude, purchase intent and brand beliefs. Journal of advertising 29(3): 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2000.10673613 [ Links ]

Van der Waldt, D.L.R., Van Loggerenberg, M. & Wehmeyer, L. 2009. Celebrity endorsements versus created spokespersons in advertising: A survey among students. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 12(1): 100-114. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v12i1.263 [ Links ]

Date submitted: 03 July 2020

Date accepted: 04 September 2020

Date published: 29 December 2020