Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Communitas

versão On-line ISSN 2415-0525

versão impressa ISSN 1023-0556

Communitas (Bloemfontein. Online) vol.25 Bloemfontein 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150525/comm.v25.3

ARTICLES

Communicative decisionmaking in the relationship between corporate donors and NGO recipients

Dr Tsitsi MkombeI; Dr Estelle de BeerII

IDepartment of Business Management, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa Email: tsmkombe@yahoo.co.uk; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6952-4916

IIDepartment of Business Management, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa Email: Estelle.debeer@up.ac.za (corresponding author) ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1265-2703

ABSTRACT

As the competition for corporate funds donated to NGOs increases, the need to know corporates' communicative decision-making processes, leading to who they fund and why, as well as how their decisions are communicated to recipients, increases. The main aim of this study was to investigate the communicative decision-making process that takes place in the relationship between corporate donors and non-governmental organisation (NGO) recipients in South Africa. The study used the qualitative strategy of enquiry and identified eight corporate social responsibility managers and eight corporate organisations as participants. Data were analysed by means of both non-automated and automated thematic analysis, for which the software programme Leximancer was used. Concept maps indicated that "reputation", "legal considerations", "relationship" and "stewardship" influence a corporate's decision-making regarding which NGOs to fund. Results also indicate that corporate organisations fund according to a donor strategy, which determines the criteria for funding. The decision-making process is furthermore followed through decision-making structures established specifically for this purpose. Evidence was also found that regular two-way communication with recipients forms an integral part of decision-making processes.

Keywords: communicative decision-making; stakeholder relationship; corporate social responsibility; strategic communication; reputation; sustainability

INTRODUCTION

Although traditionally the relationship between corporates and NGOs is seen as that of donor and passive recipient, new views put forward show that stakeholders like NGOs can be active participants and collaborators in the value creation process. They can be co-creators of solutions with numerous public-private-social enterprises. From this perspective, co-creation is about engaging with stakeholders in an inclusive, creative and meaningful manner; generating mutual expansion of value; embarking on practices that are human-centric; strategically constructing engagement opportunities throughout the business-civic-social ecosystem; and providing transparency, access, and engagement in dialogue and reflexivity (Ramaswamy 2011: 39).

In the corporate social responsibility (CSR) domain, NGOs channel organisational CSR activities to communities in society, for which they raise funds from various sources, including corporates. Through CSR funding, corporates enter into a partnership with NGOs to implement projects that benefit communities on the corporates' behalf. However, the way NGOs rely on the external environment for financial support can also expose them to resource dependence and possibly to external control (Mitchell 2014: 69).

This view of NGOs as partners and co-creators of solutions has seen CSR evolving from an altruistic response to requesting support into a response entrenched in the corporate strategy and which supports organisational identity. From this perspective, corporates now consider CSR funding processes that also provide a competitive advantage (Cantrell et al. 2015) to the company. To achieve this, corporates need to develop good two-way relationships with the NGOs that are their CSR partners.

As the competition for corporate funds donated to NGOs increases, the need to know how corporates' follow communicative decision-making processes, leading to who they fund and why, as well as how their decisions are communicated to recipients, increases. Research into the corporates' giving strategies and decision-making criteria is crucial to NGO fundraising efforts as NGOs need to know how corporates reach their decisions on donations and partnerships. Funds raised are often the lifeblood of NGOs and the latter can save time and resources if they know how corporates arrive at their decision on who to fund, which corporates are most likely to fund which NGOs, and how donors communicate their decisions about the funding to recipients.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In South Africa, government and civil society are looking to corporates to assist with solving social problems like poverty, unemployment and education. For most corporates, CSR is part of their brand management strategy, as the more they communicate about their CSR activities, the more their brand value increases. Some corporates have opened up two-way communication channels with their NGO recipient stakeholders and have embraced collaboration through dialogue. According to Dahan et al. (2010), NGOs and companies can offer missing competences to "complete" each other's business models. They can also co-create novel and innovative business models. The authors postulate that just like companies, NGOs use business models to map out the tools (mostly social, rather than economic) they intend to use to deliver value to their target public. NGOs are independent, campaigning and self-governing organisations that do not make any profit and whose attention is on the welfare of others (Gray et al. 2006). They are categorised as organisations that primarily exist to promote environmental and social goals, instead of protecting economic power or political power through the electoral process (Gray et al. 2006: 322).

Relationship between corporates and NGOs

The integrative strategic communication management theory was used as a metatheory for this multi-disciplinary study, as it emphasises integrative communication in the processes leading from decisions to action and strategy implementation. The study cuts across the three academic disciplines of corporate communication (including the reflective paradigm, systems theory, relational theory and the two-way symmetrical communication model), business management (including stakeholder theory, decision theory and game theory), and business/corporate law and governance (including legitimacy theory).

In the discipline of corporate communication, the terms "reputation" and "credibility" have been used interchangeably in some literature. Senior executives of large corporates and multinational companies see protecting their company's reputation as important and regard it as a strategic objective. Reputation represents stakeholders' perceptions of an organisation's capability to meet their expectations. The former could be interested in the company for various reasons, including buying the company's products, and being an employee or an investor (Cornelissen 2012: 3). For Rensburg and De Beer (2011), communication plays a pivotal role in growing stakeholder identification with the organisation - which is an element of corporate identity and therefore corporate reputation. Corporate reputation also mirrors a stakeholder's overall assessment of an organisation and is based on the stakeholder's first-hand experiences with it. From this perspective, reputation is built inside an organisation's stakeholder network (Rensburg & De Beer 2011: 160).

Stakeholder relationships

Stakeholders are individuals or groups who are affected by, or can affect, the organisation or its outcomes (Bourne & Walker 2008; Bourne 2011: 1004). NGOs also fall in this category of stakeholders when they deal with corporates. The theories of legitimacy, urgency and power are furthermore important for the identification of key stakeholders. Also of importance is centrality and density for recognising and showing the power and communication ties within the stakeholder community (Bourne 2011: 1004).

Methodologies established to comprehend and manage key relationships with stakeholders need to offer support for the all-inclusive view of stakeholders (Savage et al. in Bourne 2011). Mainardes et al. (2012) argue that the stakeholder management approach takes place across three levels: identifying stakeholders; developing processes that take into consideration their relevant needs and interests; and establishing and developing relationships with them and with the overall process, taking cognisance of organisational objectives. As a result, stakeholders develop expectations, experience the impact of their relationship with the organisation, evaluate the obtained results, and act appropriately as determined by their evaluations; thus, strengthening their links (Mainardes et al. 2012).

NGOs have increasingly become key stakeholders for corporations who partner with them to address social or environmental community needs. Together with corporates, they play vital roles in big institutions moulding our society, yet they often have very different agendas. Their relationship is both conflictual and collaborative. It is conflictual as NGOs and corporations can be antagonistic and filled with conflict (McIntosh & Thomas 2002). On the other hand, NGOs, through campaigns aimed at corporations, can exert pressure on companies to meet social expectations and legal requirements, and to change expectations about corporate responsibility and government regulations.

Partnerships and collaborations

To highlight NGOs' relationship with corporates, Reichel and Rudnicka (2009) argue that business organisations regard NGOs as valued partners who can play a significant role in bringing society and business together. As a result, corporates try to establish long-term relations with non-profit organisations. To show that NGOs are valued, Beaudoin (2004) argues that, for management decisions to be effective, it is necessary to include NGOs as players in the market place. Corporates also need to consider other opinions, apart from their own, when shaping decisions. In general, NGOs have been integrated into the business agenda through the stakeholder theory, while at the same time the pragmatic managerial business perspective has mainly focused on the identification of key stakeholders (Laasonen 2010: 528). With the ongoing escalation in NGO-corporate relations, engagement is widespread. Molina-Gallart (2014: 44) posits that engagements can be categorised as funding/philanthropy, partnerships, and NGO-corporate campaigning. From this perspective, corporates regard NGOs as partners.

Corporate-NGO collaboration for cross-sector relationships differ and can take the form of social partnerships, social alliances, inter-sectoral partnerships, issue-oriented alliances, as well as strategic partnerships (Dahan et al. 2010: 330). Reichel and Rudnicka (2009) furthermore argue that collaboration is not in itself without risk as one partner's good image can be damaged by another partner's unforeseen and irresponsible behaviour. As a result, taking time to build trust and reaching agreement between partners is paramount. It is also important to be aware of the power dynamics between the partnerships.

Stakeholder governance

Ackers and Eccles (2015: 524) argue that as much as compulsory legislation and regulations can force companies to up their disclosure levels, some companies will only give minimum (tick-box) disclosures in order to comply, without granting stakeholders significant value. Effective CSR, however, should extend beyond merely showing compliance to legislation and regulations (as in the case of governance), to include behaviour that is both moral and ethical, and to be considerate of the expectations society has of business (Ackers & Eccles 2015: 524).

Rensburg and Botha (2014: 144) furthermore assert that globally, corporate reporting is going through drastic changes as stakeholders increase their demands on companies and as resources have increasingly become restricted. Companies are being compelled to analytically evaluate how they can communicate financially, and transparently, with all their stakeholders. An integrated report can be regarded as communication that shows how, over the short, medium and long-term, an organisation's strategy, governance, performance and prospects can create value (IIRC 2013: 2). For Eccles and Saltzman (2011: 57), an integrated report presents and explains how a company has performed, financially, non-financially, environmentally, socially, and according to its governance (ESG) performance.

Strategic and communicative decision-making

The term "strategy" flourishes in discussions of business. The key issue uniting all discussions of strategy is a clear sense of an organisation's objectives and an understanding of how it will achieve those objectives. A strategy is viewed as a pattern in the organisation's major decisions and actions, and contains some key areas, which distinguish one firm from another (Digman in Nooraie 2012: 406).

Strategic management can be viewed as decisions and actions resulting in the formation and implementation of strategies developed to attain the objectives of an organisation (Pearce II & Robinson in Nooraie 2012: 12). It is further characterised by its emphasis on strategic decision-making. As an organisation expands and becomes more multifaceted with higher degrees of uncertainty, decision-making also becomes more complicated and difficult. Decision-making is one of the most crucial processes that managers take part in; strategic decision-making is a complicated process that needs to be understood entirely before it can be practiced it effectively (Nooraie 2012: 405). Corporates also apply strategic decision-making in the way they decide which NGOs to fund. Most decision-makers, be they individual or organisational, are concerned with discovering and selecting satisfactory options. As a result, strategy must deal with choosing the alternative that appears to satisfy a basic set of criteria (Vasilescu 2011: 105).

Reflection is considered to be part of the decision-making process and is identified as being vital, although it is regarded as subjective. Schön (in Walger et al. 2016: 657) defines reflective thinking as the type of thinking that entails going over a subject in one's mind and considering it seriously and consecutively. Two forms of reflection are suggested: reflection-on-action and reflection-in-action. The former happens subsequent to the action occurring or during a careful consideration. Reflection-inaction takes place during the action, without interrupting it.

Another perspective to communicative decision-making is the concept of participatory decision-making, which has been defined as the involvement and influence of a group of individuals in decision-making processes, which are customarily the prerogative or responsibility of a different group of individuals (Pollock & Colwill 1987: 7). For Carmeli et al. (2009), participatory decision-making refers to a management style that includes a high level of employee and supervisor participation in decisions that affect their work. This is done in teams and is often seen as a power sharing practice among team members, which empowers them to partake in strategic decision-making.

Strategic decision-making

Papadakis et al. (1998) describe the strategic decision-making process as a system of steps, phases or routes towards a decision. For Vasilescu (2011), there are four factors that affect decision-making processes: the definition of the problem; the existing rules; the order in which alternative options are presented and considered; and everything that affects aspirations and attention. It is important to note that the dynamics of decision-making mainly occur because stakeholders make efforts to come up with decisions that are as close as possible to their own position. Finally, decision-makers will shift their positions to choose a decision that is as close as possible to their own position (Stokman et al. 2000:137).

In management of meaning processes, convincing information plays a dominant role. The position and importance of a stakeholder are connected to their particular incentive structure. They postulate that the more directly an issue is connected to the central higher order objectives of a stakeholder, and the more an issue is seen as an important condition for its realisation, the more important it is to the manager. The manager's position on the issue then corresponds to the outcome of the decision that they see as best for meeting their objectives.

Information for strategic decision-making

Brunsson (in Huebner et al. 2008) defines strategic decision-making as embedded in organisational discourse and communication, and argues that the company is continuously built in communication. From this perspective, the only decisions that matter are those that are communicated (Huebner et al. 2008).

The availability of relevant information internally and externally is essential in the strategic decision-making process. Information of interest to decision-makers, such as on markets, and environments impacting on the company, like the society, competition, markets and technologies, shows the effects of the possible alternatives for decisions to be made. This information plays an important role in establishing the structures of these alternatives (Citroen 2009: 11). For this information to be useful, it needs to be strategic.

Rensburg and De Beer (2011) posit that, compelled by information technology and social media in particular, organisations are starting partnerships and joining social networks - even networks of networks. They postulate that stakeholder engagement and communicating enables the identification of stakeholder concerns and allows the organisation to set objectives and crucial performance for each stakeholder group. They further argue that the adoption of corporate dialogue would enable multidirectional flows between the stakeholders, engaging them in communication through the contribution of content, comments, and tagging.

Decision communication

Decision communication is about implementing decisions, following up, and getting feedback on how the decisions are accepted and the kind of impact they have (Mykkänen 2014: 134). Mykkänen (2014: 132) argues that decision communication's role in organisations can be considered as being much more important and significant than just communicating the outcomes of every decision. He cites Luhmann's (2003) organisation theory that states that decision communication can be seen as the force around which organisations are formed. Decisions are confirmed through decision communication and transformed for new premises for organisational decisions. Organisations as systems have a need for communicative action and organisations live in communicative rationality. From this perspective, decision-making can be regarded as a social action and needs communication to be meaningful.

The two-way symmetrical communication model endeavours to reach this balance by improving the relationship between organisations and stakeholders, and by focusing on, amongst others, conflict resolution to negotiate mutually beneficial outcomes. Two-way communication gives-and-takes information through dialogue (Grunig 1992). Corporates' use of two-way communication between themselves and their stakeholders opens up dialogue and feedback so that they can negotiate mutually beneficial outcomes, such as a stakeholder involvement strategy towards CSR communication, which assumes a dialogue with its stakeholders (Morsing & Schultz 2006: 328).

From this perspective, the relationship between a corporate and the NGOs that it funds is also vital, and trust is an important component of that relationship. Trust is paramount for successful decision-making in collaborative networks - it is characterised by transparency, fairness, and openness. NGO recipients should be free to participate in dialogue without fear of disrespect for their ideas. Reducing the risk of vulnerability is part of the decision-making process that corporates go through in deciding which NGOs to fund. Also of interest are the strategic decision-making processes that a corporate follows before a decision to fund or not to fund an NGO is finalised.

Research has shown that decision-making processes take place in contexts that usually include task forces, councils, executive boards, or boards of directors. Parts of these processes include formulating a strategy at a higher level, as well as implementing the strategy at managerial level. Thus, the efficient implementation of any strategy ensures that the structure and processes internally match the strategy envisaged (Gebczynska 2016: 1081). Part of decision-making also includes self-governing structures, in which decision-making happens through the meetings held by members or through frequent interactions that are not formal. Decision-making processes can be seen as a reflection of organisational policy or strategies and in turn are influenced by the same.

From the above discussion, communicative decision-making can be defined as the two-way strategic communication flow of the strategic decisions made by management that affect all stakeholders. This starts when deciding what to communicate to the stakeholders and how to communicate effectively in such a way that the reputation of the company is not affected and relationships with the stakeholders are maintained both internally and externally.

To investigate communicative decision-making in the relationship between corporate donors and their NGO recipients, it is imperative to show how corporates and NGOs communicate. It has been pointed out that communication remains the missing link in the practice of corporate responsibility and that, although many companies commit to fulfilling their social responsibilities, they fail in communicating their efforts sufficiently to convince anyone of it (Dawkins in Moreno & Capriotti 2009). For initiatives undertaken by corporations to gain legitimacy and the confidence of the public, responsible corporate behaviour ought to be in tandem with a capacity to communicate with and respond to the demands of stakeholders. Responsible corporations ought to engage with their stakeholders on CSR issues, and should regularly communicate about their CSR programmes, products, and impacts with concerned stakeholders (Crane & Glozer 2016).

METHODOLOGY

This study used the qualitative strategy of enquiry to explore the phenomenon of communicative decision-making and how it manifests in the relationship between corporate donors and their NGO participants. The research is phenomenological, as it sets out to understand the participants' standpoints and views of social realities (Leedy & Ormrod 2010: 108). Phenomenology is viewed as a philosophy, a research method, and a perspective for qualitative research (VanScoy & Evenstad 2015: 339). The participants consisted of both corporate practitioners and NGO practitioners.

An initial literature review and consideration of theories showed certain concepts as being important in the communicative decision-making process that corporates go through before they fund NGOs. The concepts that came up included legal considerations, decision-making, processes, structures, relationship, stewardship, trust, communication management, stakeholders and reputation.

From the concepts above, secondary research questions and items for the interview schedule were formulated for both corporates and NGOs, as the interest was in the nature of the relationship between the two parties and how corporates arrive at the decision to fund or not to fund NGOs. The researcher wanted to dig deeper through empirical research to determine how this plays out in the corporates' communicative decision-making processes, and then to compare it to the literature.

Sampling

The purposive sampling method was adopted for this study. Saunders et al. (2009: 237) argue that purposive sampling assists a researcher to use his/her judgement to choose cases that will best allow him/her to answer research questions and to meet objectives. The goal of purposive sampling is to include those participants who will produce the most relevant and ample data given the topic of study as well as those who will give the widest range of information and perspectives on the subject of study.

The sampling decisions for this study were not made in isolation from the rest of the design. It took into account the researcher's relationship with the study participants; the feasibility of data collection and analysis; validity concerns; as well as the goals of the study.

The target population was corporate funders who fund NGO projects and NGOs who have received funding from the same corporate organisations. As the research problem sought to investigate the relationship between corporate donors and their NGO beneficiaries, both parties were interviewed. The representatives from corporate donors who were interviewed were CSR managers, while the representatives from NGOs who were interviewed were programme managers responsible for raising funds and reporting to the relevant corporate donors.

The sample comprised of 16 field studies. Field studies 1 to 8 represented corporate organisations, while field studies 9 to 16 represented NGOs. Eight CSR managers who have been involved in the decision-making processes to fund NGOs were interviewed individually, after which eight representatives from (eight) NGOs who have received funding from the (eight) corporates were also interviewed. The sample size was therefore made up of 16 individuals in total. The corporates were from various sectors, including the financial, construction, scientific and manufacturing sectors. The NGOs were established organisations, have been operating for more than three years, and were in a relationship with one of the corporates interviewed at the time of the study.

Data collection

The first phase of the research involved the design of an administered semi-structured interview schedule, which was used to guide the collection of data in interviews. Eight essential items were developed from the literature review. The items focused on asking about the participant's experience of the communicative decision-making process in the relationship between corporate donors and NGO recipients. Eight main questions were posed, while sub-questions were used as probing and follow-up questions. The extra probing questions were used in the event that the initial questions did not reveal all that is required. Flexibility in questions was also used to explore other issues. The time length of the interviews varied between one and two hours.

Data analysis

The thematic analysis model, using the Leximancer data analysis tool, was used to analyse the data. Before obtaining the final Leximancer results, the data were also analysed manually. Braun and Clarke (2006: 79) postulate that thematic analysis is a technique for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data that minimally organises and describes the data set in detail.

The data that were analysed for this study were analysed by means of both non-automated (manually) and automated content analysis, for which the Leximancer software was used. Following the qualitative data analysis model provided by Braun and Clarke (2006), the data were analysed using the following six phases of thematic analysis: familiarisation of the data; generating initial codes; searching for themes; reviewing themes; defining and naming themes; and producing the report.

ANALYSIS OF CORPORATES AND NGO RESULTS

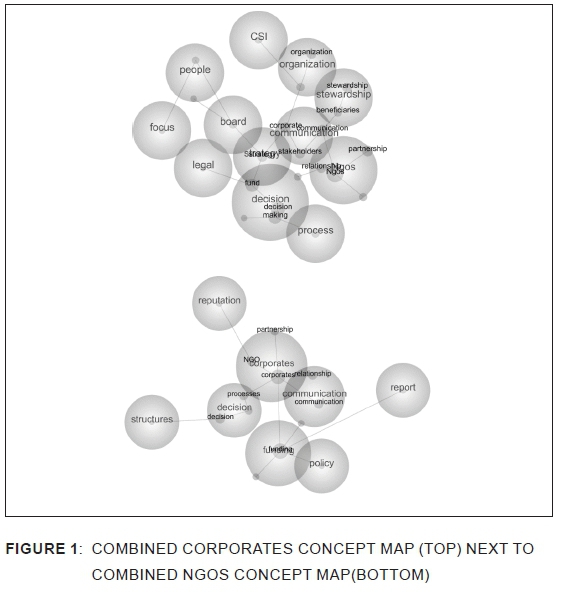

The Leximancer 4.5 concept maps show the theme depicted by a circle - within each theme, concepts appear that make up that theme. The concepts assisted in refining the themes during the data analysis phase.

The results of the data analysis are illustrated in Figure 1 in the form of combined corporates and NGO concept maps.

This section addresses how the various patterns in the responses from corporates and the responses from the NGOs link with each other across field studies. It places corporate results next to NGO results to see how they overlap/differ and highlights any other observations that were found.

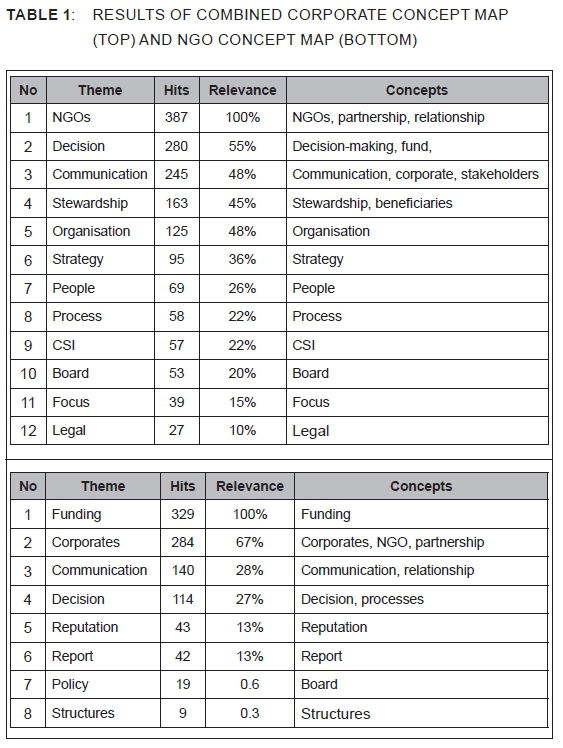

Themes

With regards to similarities, the results indicate that the decision theme and the communication theme are important to both corporates and NGOs. Differences show up in the following themes: the stewardship theme shows up in the corporates' results but not in the NGOs results; the top theme for corporates is NGOs, whereas the top theme for NGOs shows up as funding; for corporates, decision-making processes are so important that a separate process theme could be identified from the data, whereas for NGOs processes is a concept within the decision theme; corporates identified strategy as an important theme, which is linked directly to the board theme, the decision theme and the communication theme, while a policy theme, which is directly related to funding, was identified from the NGO data.

Reputation: The reputation theme was ranked fifth in importance to NGOs, with 43 hits and 13% relevance, whereas this does not feature at all in the combined corporate map. As much as reputation is important to corporates, NGOs see their reputation as crucial. For them it is important to determine (in the decision-making process) which corporates to partner with, because if they partner with the wrong one, it will not only cost them their reputation, but can impact their ability to obtain funding from other potential funders in the future.

Co-creation: NGOs showed the highest relevance to corporates with a 100% relevance, while funding showed the highest relevance to NGOs with 100% relevance. This illustrates that corporates need NGOs to meet their goal of working with communities, while NGOs need corporates for funding in order to meet their goals of working with communities and making a positive difference in communities. In this way a co-creative relationship is established.

Partnership: Partnership came up strongly in both the corporates' and the NGOs' results. From the data on corporates, NGOs was identified as a theme, within which the following concepts were identified: NGOs, partnership and relationship. From this it can be deducted that corporates view NGOs as partners with whom they have a relationship. On the other hand, the NGOs have corporates as a theme, which has corporates, NGOs and partnerships as concepts, showing that the NGOs also regard the corporates as partners.

Communicative stakeholder relationship: The communication theme was identified as the third highest in relevance for both corporates and NGOs. For corporates, the communication theme has communication, corporates and stakeholders as concepts; while for NGOs, the communication theme has communication and relationship as concepts. This shows the communicative nature of the relationship between corporate donors and their NGO recipients. Dialogue is also important in the relationship.

FINDINGS

The six research questions are addressed below.

RQ1: What is the nature of the relationship between corporate donors and their NGO recipients?

From the findings of this study, it is clear that the nature of the relationship between corporate donors and their NGO recipients has many different layers and takes different forms. The co-orientation model offered a framework for identifying relationships among various groups involved in the communication process, including corporate donors and their NGO recipients. Co-orientation provides a uniting structure for determining the nature of the relationships between the stakeholders in a communication process (Br0nn & Br0nn 2003: 292).

From the empirical findings of the study, it appears that funding is the main reason for the corporates interviewed being in a relationship with their NGO recipients and that the two parties' relationship is a contractual one, from a stakeholder theory perspective. Hult et al. (2011: 44) highlight that a contemporary stakeholder theory in management can be found in the development of an all-inclusive and integrated comprehension of the stakeholder concept.

The systems theory supports the funding principle that corporates are giving to NGOs for the benefit of society in a social context. From this perspective, organisations forge linkages with other organisations because they depend on these components within the system to enable them to survive and to reach goals (Baldwin et al. 2004: 295).

The findings show that corporates value their NGO recipients and attempt to establish long-term relations with them. Because they see them as partners, they take time to do research on the potential partner and to conduct due diligence before they enter into a partnership with the NGO. The active management of relationships from a relational theory perspective, and the promotion of shared interests, further shows an intentional understanding and valuing of the relationship between corporates and their NGO recipients.

Trust emerged as a vital part of the relationship between corporates and their NGO recipients. All the participants interviewed mentioned trust as an important part of the relationship. The concept of power relations also came up and the findings show that corporates are aware of these power relations, and that they have the upper hand because they provide the funds. One corporate, however, highlighted that "when a corporate selects an NGO partner they would also have to look at the extent to which the NGO brings expertise to the relationship".

The findings also indicate that the relationship between corporates and their NGO recipients is collaborative, as they partner to achieve common goals.

RQ2: What factors contribute towards a good relationship between corporate donors and their NGO recipients?

The main outcome and basis of the relationship between corporates and their NGO recipients is funding. All the corporates and NGOs interviewed for the study were in a relationship because of funding received from the corporates. Some of the corporates interviewed for the study see their relationship with NGOs as a partnership. Empirical results also show that corporates use engagement, collaboration, and partnership as ways of engaging with NGOs.

The findings further express that NGO acknowledgement of/to the corporate donor for the funds or gifts received, and thanking the donor in writing for the funds, is an important part of the relationship between the corporates and their NGO recipients.

Relevant here is relational theory as it speaks to the relationships between corporate donors and their NGO recipients. This theory posits that the stakeholder approach involves enunciating, expressing, analysing and comprehending corporate relationships (Lozano 2005: 63).

The agreement/contract between the corporates and NGOs includes stewardship of donor funds by NGOs. All the corporates and NGOs who were interviewed expressed that corporates expected NGOs to demonstrate stewardship through reporting regularly via a narrative and financial report to the corporate donor. The findings also express that some corporates prefer to hear, not only from the NGO recipients, but also from the beneficiaries. Therefore, the reports can include success stories from beneficiaries with before and after photographs showing the difference the interventions are making. Monitoring and evaluation reports are also used as stewardship measures.

According to Lanis and Richardson (2012), legitimacy theory is an explanation for increased levels of environmental CSR, which provides a lens to understand CSR reporting. This theory is pertinent to the study, as it is part of the communicative process that corporates go through in their relationships with NGOs and other stakeholders, as they share information that communicate their CSR efforts.

RQ3: How important is corporate reputation and NGO reputation in the relationship between the corporate donor and their NGO recipients?

The corporates interviewed indicated that reputation was important because it is at the base of the business's support and if a business loses its reputation, they lose everything. Reputation is also important because the organisations interviewed would not want to partner with an organisation that would tarnish their corporate's image.

The results for RQ3 were interpreted using the reflective paradigm. Rensburg and De Beer (2011) argue that it analytically defines phenomena like the triple bottom-line (people, planet, profit), multi-stakeholder dialogue, symmetrical communication and ethical accounts, which ultimately contribute to the corporate reputation.

All the NGOs interviewed in the study stressed the importance of reputation when an NGO is looking to partner with a corporate. From the findings, the NGOs indicated that they want to be associated with reputable businesses as partnering with the wrong corporates could jeopardise future funding. The NGOs interviewed prefer to receive funding from corporates with a good corporate business conscience in everything they do. These include responsible, ethical corporates that do good in an area where they are seen, but that also do not exploit the environment in their daily business operations.

When the corporates were asked how they reduce/mitigate risk when deciding on which NGOs to partner with, they indicated that they go through a strict process to root out the NGOs that may expose them to reputational risk - this would influence their decision-making whether to fund the NGO or not. How the corporates reduce/mitigate risk when deciding which NGOs to partner with, will inform their decision-making.

The corporate participants indicated that they had someone monitoring corporate reputation (even if for some it was an external party).

RQ4: What are the criteria for communicative decision-making when corporate donors fund NGOs?

The findings of this study indicate that most corporates communicate with their NGO recipients through their CSI/CSR representative. They choose how often to communicate and which channels of communication to use - emails were the most used channel. From the findings, it is clear that NGOs communicate what is stipulated in the contractual agreement between them and their corporate funders. The communication takes place through the programme managers who are responsible for the relationship with the corporate donors.

Data from the study shows that corporates manage the communication with their NGO stakeholders by setting expectations upfront and regularly communicating their expectations. They also regularly state what the NGOs can expect, so that they "are all on the same page", indicating a two-way symmetrical communication process. The two-way symmetrical communication model strives to attain balance by altering the relationship between organisations and publics, and by concentrating on dispute resolution to negotiate mutually beneficial outcomes. Two-way communication exchanges information through dialogue (Grunig & Grunig 1992.) In the study, the use of two-way communication between the corporates and their NGO recipients opens up dialogue and feedback so that they can negotiate mutually beneficial outcomes.

The findings further show that corporates set an annual funding strategy, which aligns with the larger organisational strategy, from where they will determine the focus areas for their giving. Corporates also need to assign a budget to the focus areas and allocate funds per focus area. After decisions have been made on these allocations, they communicate this to potential NGO beneficiaries.

RQ5: What are the communicative decision-making processes/ procedures that corporates follow when funding NGOs?

The findings from the research show that corporates follow communicative strategic decision-making processes when funding NGOs. These processes assist them to arrive at the decision about which NGOs to fund and how to communicate the decisions made. These decisions, therefore, set a precedence on which NGOs receive funding from the corporates. Decision theory guided the interpretation of the empirical data relevant to this research question, and it is about how decisions are made. According to De Almeida and Bohoris (1995), the theory offers a logical framework for resolving real-life problems.

The findings show that corporates set criteria for funding before they fund an NGO. To ensure that NGOs qualify under the set criteria, the corporates have to do research to find information on the NGO. This information is used by the different structures to make the decision to fund or not to fund certain NGOs.

The empirical findings of the study show that potential NGOs are also given documents to complete in order to obtain certain information about their status. This includes information about their funders, and how much money they have received, to determine whether they have experience in managing large funds. Information required from NGOs includes audited financial statements, registration documents, and the CVs of the board and the management team.

The empirical findings further show that face-to-face meetings and site visits by the corporates to see where the NGOs are operating from are part of the communicative decision-making process.

RQ6: What communicative decision-making structures do corporates use in deciding which NGOs to fund?

The empirical findings indicate that strategic decision-making takes place through different structures in the organisation, as well as individually; to some extent using the information at their disposal. Decision-making includes self-governing structures, in which the former occurs through meetings of members or through informal, frequent interactions. Game theory was, amongst others, deemed suitable for the interpretation of these results, as it includes the formal study of conflict and cooperation, which provides a language to analyse, understand, formulate and structure strategic settings (Turocy & Von Stengel 2001).

The empirical findings highlight that both NGOs and corporates have decisionmaking structures where decisions are ultimately made. The most influential decisionmaking structure for corporates and NGOs is the board of directors. The board sets the policies and strategies which guide committees, management teams and individuals in their decision-making. Other decision-making structures include board subcommittees, executive committees, advisory committees, management committees and CSI/CSR committees.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The main purpose of this research was to investigate the communicative decision-making that takes place in the relationship between corporate donors and NGOs as the recipients of funding. The results indicate that factors such as reputation, legal considerations, relationship and stewardship influence a corporate organisation's decision-making regarding which NGOs to fund. The findings also indicate that corporates fund according to their strategy, which determines the criteria for funding; moreover, the decision-making process is conducted through decision-making structures.

The traditional view of the relationship between corporates and NGOs is that of donor and passive recipient, but findings from this study indicate that stakeholders like NGOs can be active participants and collaborators in the mutual relationship between them, and as such can be co-creators of development solutions.

The research also highlights the importance of a two-way symmetrical communication relationship between these strategic partners. With this in mind, the findings recognise NGOs who are recipients of corporate funding as strategic stakeholders and also highlight the strategic and communicative decision-making processes and structures in the relationship between corporate donors and their NGO recipients.

Lastly, the research indicates that the communicative aspect of the decision-making process is important and can be regarded as a catalyst for the relationship between corporates and NGO recipients. From this perspective, it is vital that the decision-making criteria regarding funding should be communicated to NGOs at every level of the decision-making process.

REFERENCES

Ackers, B. & Eccles, N.S. 2015. Mandatory corporate social responsibility assurance practices: The case of King III in South Africa. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 28(4): 515-550. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-12-2013-1554 [ Links ]

Baldwin, J.R., Perry, S.D. & Moffitt, M.A. 2004. Communication theories for everyday life. New York: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Beaudoin, J.P. 2004. Non-governmental organisations, ethics and corporate public relations. Journal of Communication Management 8(4): 366-371. https://doi.org/10.1108/13632540410807754 [ Links ]

Bourne, L. 2011. Advising upwards: managing the perceptions and expectations of senior management stakeholders. Management Decision 49(6): 100-1023. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741111143658 [ Links ]

Bourne, L. & Walker, D.H.T. 2008. Project relationship management and the stakeholder circle. International Journal of Managing Project in Business 1(1): 125-30. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538370810846450 [ Links ]

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Br0nn, P.S. & Br0nn, C. 2003. A reflective stakeholder approach: Co-orientation as a basis for communication and learning. Journal of Communication Management 7(4): 291-303. https://doi.org/101108/13632540310807430 [ Links ]

Cantrell, J.E., Kyriazis, E. & Noble, G. 2015. Developing CSR giving as a dynamic capability for salient stakeholder management. Journal of Business Ethics 130(2): 403-421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2229-1 [ Links ]

Carmeli, A., Sheaffer, Z. & Halevi, M.Y. 2009. Does participatory decision-making in top management teams enhance decision effectiveness and Arm performance? Personnel Review 38(6): 696-714. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480910992283 [ Links ]

Citroen, C. 2009. Strategic decision-making processes: The role of information. Unpublished doctoral thesis. University of Twente, The Netherlands. [ Links ]

Cornelissen, J.P. 2012. Corporate communication. A guide to theory and practice. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Crane, A. & Glozer, S. 2016. Researching corporate social responsibility communication: Themes, opportunities and challenges. Journal of Management Studies 53(7): 1223-1252. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12196 [ Links ]

Dahan, N.M., Doh, J.P., Oetzel, J. & Yaziji, M. 2010. Co-creating new business models for developing markets. Long Range Planning 43: 326-342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.11.003 [ Links ]

De Almeida, A.T. & Bohoris, G.A. 1995. Decision theory in maintenance decisionmaking. Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering 1(1): 39-45. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552519510083138 [ Links ]

Eccles, R.G. & Saltzman, D. 2011. Achieving sustainability through integrated reporting. Stanford Social Innovation Review (Summer): 57-61. [ Links ]

Gebczyñska, A. 2016. Strategy implementation efficiency on the process level. Business Process Management Journal 22(6): 1079-1098. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-01-2016-0004 [ Links ]

Gray, R., Bebbington, J. & Collison, D. 2006. NGOs, civil society and accountability: making the people accountable to capital. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 19(3): 319-348. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570610670325 [ Links ]

Grunig, J.E. 1992. Excellence in public relations and communication management. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Grunig, J.E. & Grunig, L.A. 1992. Models of public relations and communication. In: Grunig, J.E. (ed.) Excellence in public relations and communication management. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Huebner, H., Varey, R. & Laurie Wood, L. 2008. The significance of communicating in enacting decisions. Journal of Communication Management 12(3): 204-223. https://doi.org/10.1108/13632540810899407 [ Links ]

Hult, G.T.M., Mena, J.A., Ferrell, O.C. & Ferrell, L. 2011. Stakeholder marketing: a definition and conceptual framework. Academy of Marketing Science Review 1(1): 44-65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-011-0002-5 [ Links ]

IIRC (International Integrated Reporting Committee). 2013. The international framework. Integrated reporting. London: IIRC. [ Links ]

Laasonen, S. 2010. The role of stakeholder dialogue: NGOs and foreign direct investments. Corporate Governance: The international journal of business in society 10(4): 527537. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720701011069731 [ Links ]

Lanis, R. & Richardson, G. 2012. Corporate social responsibility and tax aggressiveness: a test of legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 26(1): 75100. https://doi.org/101108/09513571311285621 [ Links ]

Leedy, P.D. & Ormrod, J.E. 2010. Practical Research: Planning and Design. New Jersey: Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Lozano, J.M. 2005. Towards the relational corporation: from managing stakeholder relationships to building stakeholder relationships (waiting for Copernicus). Corporate Governance: The international journal of business in society 5(2): 60-77. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720700510562668 [ Links ]

Luth, M.T. & Schepker, D.J. 2017. Antecedents of corporate social performance: the effects of task environment managerial discretion. Social Responsibility Journal 13(2): 339354. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-03-2016-0038 [ Links ]

Mainardes, E.W., Alves, H. & Raposo, M. 2012. A model for stakeholder classification and stakeholder relationships. Management Decision 50(10): 1861-1879. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741211279648 [ Links ]

Mcintosh, M. & Thomas, R. 2002. Corporate Citizenship and the evolving relationship between non-governmental organisations and corporations. London: Copyprint. [ Links ]

Mitchell, G.E. 2014. Strategic responses to resource dependence among transnational NGOs registered in the United States. Voluntas 25: 67-91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9329-2 [ Links ]

Molina-Gallart, N. 2014. Strange bedfellows? NGO-corporate relations in international development: an NGO perspective. Development Studies Research 1(1): 42-53. https://doi.org/10.1080/21665095.2014.915617 [ Links ]

Moreno, A. & Capriotti, P. 2009. Communicating CSR, citizenship and sustainability on the web. Journal of Communication Management 13(2): 157-175. https://doi.org/10.1108/13632540910951768 [ Links ]

Morsing, M. & Schultz, M. 2006. Corporate social responsibility communication: Stakeholder information, response and involvement strategies. Business Ethics: A European Review 15(4): 323-338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2006.00460.x [ Links ]

Mykkänen, M. 2014. Organizational decision-making: The Luhmannian decision communication perspective. Journal of Business Studies Quarterly 5(4): 131-146. [ Links ]

Nooraie, M. 2012. Factors influencing strategic decision-making processes. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2(7): 405-429. [ Links ]

Papadakis, V.M., Lioukas, S. & Chambers, D. 1998. Strategic decision processes: The role of management and context. Strategic Management Journal 19: 115-147. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199802)19:2<115::AID-SMJ941>3.0.CO;2-5 [ Links ]

Pollock, M. & Colwill, N.L. 1987. Participatory decision-making in review. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 8(2): 7-10. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb053611 [ Links ]

Ramaswamy, V. 2011. Co-creating development. Development Outreach (September): 39-34. [ Links ]

Reichel, J. & Rudnicka, A. 2009. Collaboration of NGOs and business in Poland. Social Enterprise Journal 5(2): 126-140. https://doi.org/10.1108/17508610910981716 [ Links ]

Rensburg, R. & Botha, E. 2014. Is integrated reporting the silver bullet of financial communication? A stakeholder perspective from South Africa. Public Relations Review 40: 144-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2013.11.016 [ Links ]

Rensburg, R. & De Beer, E. 2011. Stakeholder engagement: a crucial element in the governance of corporate reputation. Communitas 16: 151-169. [ Links ]

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. 2009. Research methods for business students. England: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Turocy, T.L. & Von Stengel, B. 2001. Game theory. CDAM Research Report. Texas: A&M University. [ Links ]

VanScoy, A. & Evenstad, S.B. 2015. Interpretative phenomenological analysis for LIS research. Journal of Documentation 71(2): 338-357. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-09-2013-0118 [ Links ]

Vasilescu, C. 2011. Effective strategic decision-making. Journal of Defence Resources Management 1(2): 101-106. [ Links ]

Walger, C., Roglio, K.D.D. & Abib, G. 2016. HR managers' decision-making processes: a 'reflective practice' analysis. Management Research Review 39(6): 655-671. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-11-2014-0250 [ Links ]

Date submitted: 27 February 2020

Date accepted: 04 September 2020

Date published: 29 December 2020