Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Town and Regional Planning

versión On-line ISSN 2415-0495

versión impresa ISSN 1012-280X

Town reg. plan. (Online) vol.83 Bloemfontein 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.38140/trp.v83i.7469

REVIEW ARTICLE

Capturing landscape identity in the context of urban renewal: The case of Kisumu City, Kenya

Vaslegging van landskapidentiteit in die konteks van stedelike vernuwing: die geval van die stad Kisumu, Kenia

Ho nka boitsebahatso ba naha molemong oa nchafatso ea litoropo, boithuto ba Kisumu city, Kenya

Edwin K'oyooI; Christina BreedII

IPhD student in Landscape Architecture, Department of Architecture, University of Pretoria, South Africa. PO Box 438940103, Kondele, Kisumu, Kenya. Phone: +254-727-477-746, email: edwinkoyoo@gmail.com, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7049-1034

IISenior lecturer, Department of Architecture, University of Pretoria, Private Bag X20, Hatfield, 0028. Phone: +27 (0)12 420 4536, email: ida.breed@up.ac.za, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2185-8367

ABSTRACT

Urban renewal is undertaken to respond to the physical deterioration of built forms in postcolonial Africa, with renewal works affecting current cities' identities. Globalisation trends have cities striving to be unique, with a growing awareness of the importance of identity. Landscape identity is adopted in this study as the overall term that includes other identities and is interpreted as residents' perception of the special features that help them differentiate between places. This study postulates that a city's uniqueness lies in its landscape identity and that this should not be neglected. The article investigates the concept of landscape identity in the context of a case study of the city of Kisumu, Kenya, which has recently undergone urban renewal. The aim of the study was to identify the main aspects that constitute the formation of landscape identity in Kisumu. A mixed-methods approach was used, which included field investigations, a survey with 384 participants, and four key informant interviews. The survey results revealed that the city's location along Lake Victoria, which represented an element of the natural environment, gave it the highest rating. The proximity to Lake Victoria and views of the hills were regarded as the most outstanding features of the city, while the lake was the highest ranked element with symbolic meaning that evoked individual and collective memories. These findings suggest that the urban landscape identity in Kisumu is strongly connected to features of the natural environment.

Keywords: Global South, Kisumu, Kenya, landscape identity, postcolonial Africa, urban landscape identity, urban renewal

OPSOMMING

Stedelike vernuwing word onderneem om te reageer op die fisiese agteruitgang van geboude vorms in postkoloniale Afrika, met vernuwingswerke wat huidige stede se identiteite beïnvloed. Globaliseringstendense toon stede wat daarna streef om uniek te wees, met 'n groeiende bewustheid van die belangrikheid van identiteit.

Landskapidentiteit word in hierdie studie aanvaar as die algehele term wat ander identiteite insluit en word geïnterpreteer as inwoners se persepsie van die spesiale kenmerke wat hulle help om tussen plekke te onderskei. Hierdie studie postuleer dat 'n stad se uniekheid in sy landskapidentiteit lê en dat dit nie afgeskeep moet word nie. Die artikel ondersoek die konsep van landskapidentiteit in die konteks van 'n gevallestudie van die stad Kisumu, Kenia, wat onlangs stedelike vernuwing ondergaan het. Die doel van die studie was om die hoofaspekte wat die vorming van landskapidentiteit in Kisumu uitmaak, te identifiseer. 'n Gemengde-metode-benadering is gebruik wat veldondersoeke, 'n opname met 384 deelnemers, en vier sleutel-informant-onderhoude ingesluit het. Die opnameresultate het aan die lig gebring dat die stad se ligging langs die Victoria-meer, wat 'n element van die natuurlike omgewing verteenwoordig het, dit die hoogste gradering gegee het. Die nabyheid aan die Victoria-meer en uitsigte oor die heuwels is as die mees uitstaande kenmerke van die stad beskou, terwyl dit die hoogste element met simboliese betekenis was wat individuele en kollektiewe herinneringe opgeroep het. Hierdie bevindinge dui daarop dat die stedelike landskapidentiteit in Kisumu sterk verbind is met kenmerke van die natuurlike omgewing.

KAKARETSO

Ho nchafatsoa ha litoropo ho etsoa ho lokisa meaho e senyehileng Afrika ka mor'a bokolone, 'me mesebetsi ea nchafatso e ama semelo sa litoropo tsa hajoale. Mekhoa ea ho ikopanya ha lichaba tsa lefatse e susumetsa hore libaka li leke ho ba le semelo se khethehileng, ka tlhokomeliso e ntseng e eketseha ea bohlokoa ba boitsebiso. Boitsebahatso ba naha bo amohetswe phuputsong ena e le poleloana e ananelang ebile e kenyeletsa boitsebahatso ka kakaretso, ka hona e tolokoa e le maikutlo a baahi mabapi le dikarolo tse ikgethang tse ba thusang ho kgetholla dibaka. Phuputso ena e fana ka maikutlo a hore ho ikhetha ha toropo ho itsetlehile ka sebopeho sa eona le hore sena ha sea lokela ho hlokomolohuoa. Sengoliloeng se batlisisa mohopolo oa boitsebahatso ba naha molemong oa thuto ea toropo ea Kisumu, Kenya, e sa tsoa nchafatsoa. Sepheo sa thuto e ne e le ho tseba likarolo tsa mantlha tse etsang sebopeho sa boleng ba naha ea Kisumu. Ho ile ha sebelisoa mekhoa e fapaneng ea boithuto, e kenyelelitseng lipatlisiso, phuputso e nang le barupeluoa ba 384, le lipuisano tse 'nè tsa bohlokoa le litsebi. Liphetho tsa phuputso li ile tsa senola hore sebaka se toropong e haufi le Letsa la Victoria, se neng se emela karolo ea tikoloho, se fane ka boemo bo phahameng ka ho fetisisa. Bohaufi ba Letsa la Victoria le maralla a potapotileng li nkuoe e le tsona tse hlahelletseng ka ho fetesisa semelong sa toropo. Letsa lena le hlahelletse ele sebaka sa boemo bo holimo se nang le moelelo oa tSoantsetso, 'me se ile sa tsosa mehopolo ea motho ka mong le lihlopha tse nkileng karolo boithutong bona. Liphuputso tsena li fana ka maikutlo a hore toropo ea Kisumu e hokahane ka matla le likarolo tsa tikoloho.

1. INTRODUCTION

Fast-developing and expanding cities face challenges such as urban decay, deterioration of the environment, lack of infrastructure, social challenges, and economic decline (Ploegmakers, 2015: 2151; Zheng et al., 2017: 361). Although urban decay is historically associated with North America and parts of Europe, especially the United Kingdom and France (Andersen, 2003), cities in the Global South have also been experiencing urban deterioration, both historically and presently (Amado & Rodrigues, 2019; Dimuna & Omatsone, 2010; Leon, Babere & Swai, 2020; Njoku & Okoro, 2014). According to recent studies (Saglik & Kelkit, 2017; Shao et al., 2020) contemporary globalisation, industrialisation, and technological developments have caused radical changes in cities and have, to a certain degree, homogenised cities. These changes, often introduced through urban renewal, are functional but also have implications in form and aesthetics that affect the local urban identity. Shao et al. (2020: 1) posit that neglect of urban landscape identity is a common global problem many cities face. Baris, Uckac and Uslu (2009: 733) as well as Antrop (2005) posit that, due to these processes of globalisation, rapid changes have occurred in urban areas that result in challenges in social, economic, and cultural lives and environments. Due to the abovementioned challenges, the concept of identity has been brought to the agenda of urban studies and design professionals. Several decades ago, Beauregard and Holcomb (1981) raised concern among built environment professionals to discover and preserve the inherent image and identity when reshaping the existing environment. Currently, the major concern has become the sustainability of place identity, due to the constantly occurring changes (Kaymaz, 2013: 739).

Reviewed studies on urban renewal in postcolonial Africa are concerned with creating viable communities, due to the upgrading of decayed neighbourhoods and spaces (Amado & Rodrigues, 2019; Dimuna & Omatsone, 2010; Njoku & Okoro, 2014). These studies tend to emphasise the social and physical aspects, with less attention paid to the need to preserve urban landscape identity. This study aims to address this gap in the literature by focusing on the preservation of urban landscape identity during urban renewal as it manifests in postcolonial Africa. There is a need for greater consideration of these natural and anthropogenic dimensions of the landscape in urban renewal projects, as they are generally neglected.

Through a case study of the city of Kisumu in Kenya, this study inquires into the main aspects that constitute the formation of urban landscape identity in Kisumu as it is undergoing urban renewal. Based on the literature, the article specifically inquires into four aspects: the influential elements, the best and worst features, the symbolic meaning, and the memories that generate Kisumu's urban landscape identity. Through this inquiry, the researchers hope to provide a perspective on the place-specific nuances of landscape identity within a postcolonial African context.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

To understand the main aspects that constitute the formation of landscape identity in the city of Kisumu, the article defines urban landscape identity and reviews its components. It proposes a definition and conceptual framework for the term and reviews the importance of memory and urban landscape identity.

2.1 Defining urban landscape identity

Many studies have aimed to consolidate aspects of identity. In this instance, the focus is on bringing those aspects together to document and define urban landscape identity. The concept of landscape identity builds on both place identity literature and landscape studies, although most of the literature lacks a clear definition. Egoz (2013) described landscape identity as the relationship between the landscape and the identity of the people who interact with it. Stobbelaar and Pedroli (2011: 322) defined landscape identity as the "perceived uniqueness of a place". This represents the role of landscape in the formation of identity of place, but both the above definitions fall short of encapsulating certain complexities. According to Enache and Craciun (2013: 310), besides the people, landscape also comprises the spatial structure of a place, as well as the activities and the processes within the place (Enache & Craciun, 2013: 310). Relph (1976: 122) emphasises how landscape character derives from a particular association of the physical and built characteristics with meanings for those who are experiencing them, "character and meaning are impacted to landscapes by intentionality of experience".

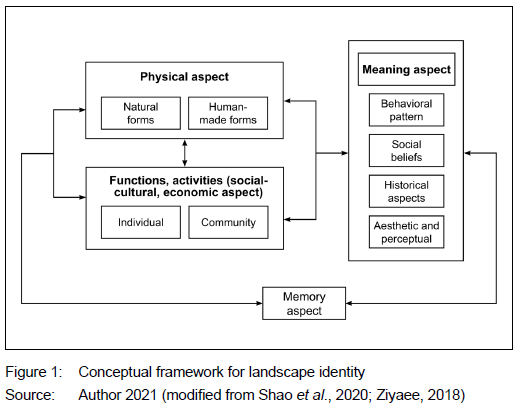

From the literature reviewed, there seem to be common aspects that shape place, urban and landscape identity with respect to physical aspects, social and cultural functional aspects, and the meaning attributes of the given place. These combined aspects end up shaping experiences and the related memories associated with a given place. The definition of urban landscape identity for this study (modified from Shao et al., 2020) is the residents' perception of the special features that help them differentiate between places - encompassing the forms or physical aspects, sociocultural aspects (functions and activities) and meaning aspects. All three aspects combine to create recognisable images that relate to residents' experiences and memories. This study adopted aspects from Eren (2014), Okesli and Gurcinar (2012), Shao et al. (2020), and Ziyaee (2018) in formulating the elements that constitute the formation of landscape identity as summarised in the definition above and the conceptual framework in Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework for landscape identity and the three aspects that form identity, i.e. the physical aspects, functions and activities, and meaning, together with the resultant memory associated with the landscape.

2.2 Aspects or components of landscape identity

2.2.1 Physical aspects (forms)

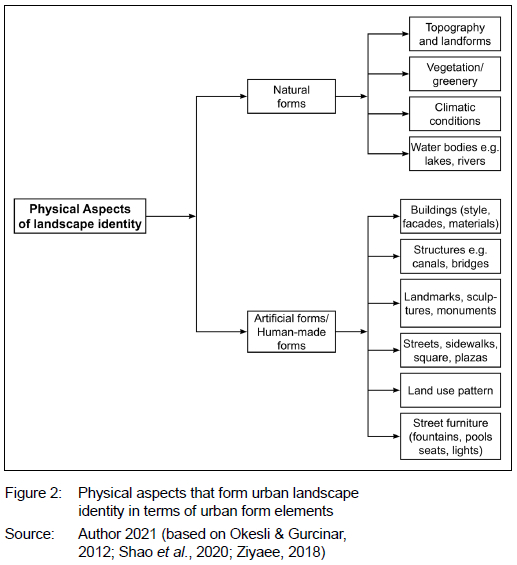

According to Shao et al. (2020: 6), the phrase 'physical aspects' is used to describe the surrounding geographical features, as well as other visible features such as the styles of architecture and the natural environment. These forms act as the medium for interaction between people and their surrounding environment. Stobbelaar and Hendriks (2004: 2) state that the physical aspect acts as the primary means that reflects the relationship between personal identity and the identity related to the space. The physicality of all identities is the most basic and easily explored aspect. Ziyaee (2018: 24) divides the physical aspect of landscape identity into natural forms and human-made forms, while Okesli and Gurcinar (2012: 38) refer to "natural" and "artificial" attributes. The natural attributes can be summarised as topographical and hydrographical characteristics, and climatic and flora characteristics, while the artificial attributes consist of settlement components such as buildings, streets, and city squares. These human-made forms include the shape of spaces, access, buildings, and objects such as street furniture (Ziyaee, 2018: 25). Although all physical components could contribute meaning, the human-made components are considered to be more symbolic.

An expression of urban landscape identity is complex and may be realised from a combined understanding of the different urban elements of the place and natural aspects. Urban elements include public spaces such as parks with artistic sculptures or fountains (Ziyaee, 2018: 25) that are, to some degree, natural, but human-made. Norberg-Schulz (1979: 179) emphasised how some places get their identity from a particularly interesting location with hardly any contribution of human-made components, while other places are situated in a dull landscape, but the human-made environment possesses a "well-defined configuration and a distinct character". Norberg-Schulz (1979) points out that what determines the identity of places also includes location inside the city (or country), while the configuration of the spaces and characteristics that articulate the places include spatial proportions. Urban image theory, developed by Lynch (1960), acknowledges the elements that define city spaces as paths, nodes, landmarks, edges, and districts. Lynch (1960) argues that the strong physical form and spatial relationships and associated meanings of these five elements collectively make a place a highly memorable environment. This study summarised the physical aspects of the landscape as the components indicated in Figure 2.

2.2.2 Sociocultural aspects (functions and activities)

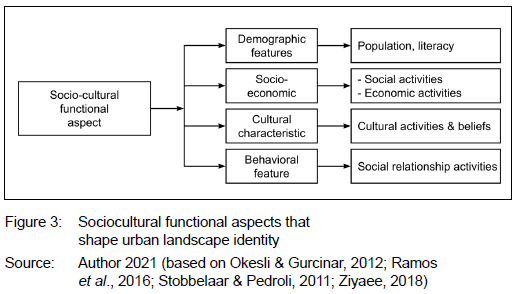

Shao et al. (2020: 6) state that social activities play a critical role in the formation of existential identity within urban landscape identity. Social activities help build the bond between residents and the local area where they dwell through experience and memories. Activities integrate people's needs into spatial functions that make places unique (Shao et al., 2020: 6). According to Stobbelaar and Pedroli (2011: 328), places used by the local population for celebratory, commemorative, or recreational activities and events may become part of the cultural-existential landscape identity. Ziyaee (2018: 24) considers the sociocultural as an immaterial component of landscape identity that includes social beliefs in terms of events and festivals, behavioral patterns and rules such as the separation of activities and forbidden activities. Figure 3 summarises these sociocultural aspects.

2.2.3 Meaning aspect

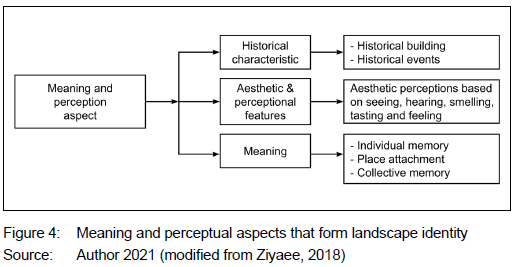

Proshansky, Fabian and Kaminoff (1983) state that the development of a sense of 'self' is a matter of distinguishing oneself from others by means of what one views, hears and other sensory modes of perception. People associate places cognitively and objectively. People have different life experiences and hence, have different opinions due to feelings about places. Stobbelaar and Pedroli (2011: 326) state that the significance of a landscape that is considered personal lies in the associations and memories attached by those interacting with it. Stobbelaar and Hendriks (2004: 3) consider the meaning aspect in individual and collective forms. First, in terms of associations, memories and meanings are attached to symbolic features associated with places in the landscape, where the 'I-feeling' of an individual is confirmed within a given place (Stobbelaar & Henriks, 2004). Secondly, as the meanings that are associated and attached to the different places, environmental features or societal events in the landscape have a role to play in achieving the collective living world and confirmation of the 'we-feeling' of a group of people (Stobbelaar & Henriks, 2004).

Ziyaee (2018: 24) considers the meaning aspect as semantics, consisting of meaning and symbols among people. This aspect is part of the immaterial component of landscape identity, which constitutes the social beliefs and rules of the people. Meanings can be attached to natural and artificial forms. These comprise vernacular views of plants, symbolic plants, and the symbolic use of water, including historic symbolic names of places (Ziyaee, 2018: 25). Human-made forms can also have meanings and be considered symbols in terms of their forms. The meaning could be shaped by the hierarchy of access, symbolic buildings for cultural and religious functions, and symbolic street furniture such as sculptures, fountains, etc. (Ziyaee, 2018: 25). Social beliefs can affect rules on the form variations of buildings and other structures. Time and process influence the heritage value, architectural eras and related building techniques and methods, as well as the vernacular materials, aesthetics and sense of beauty (Ziyaee, 2018: 25) that all impact on the significance from the perspective of a particular viewer. Figure 4 summarises the meaning and perception aspects of landscape identity.

2.3 The importance of memory and urban landscape identity

A study by Ramos et al. (2016: 39) draws attention to the fact that the 'past', in general, is of outstanding relevance to urban landscape identity in a given place. How people and landscapes interact should be considered in several dimensions, along with the various aspects that constitute the formation of landscape identity. The authors refer to 'memories' as a symbolic aspect of landscape identity associated with a given place and experience. This is formed by the interaction of all the aspects that constitute landscape identity, and depends on people's perceptions about the particular landscape. A place with a notable and unusual meaning develops by accumulating the individual and collective memories associated with events, persons, or physical elements of the place. Place identity evolves as a result of the interconnection of the activities carried out in a place and the memories associated with the place through people's perceptions of time (Ramos et al., 2016: 40).

Rossi (1982) argues how collective memories associated with a given place shape the identity of a city. The "city itself is the collective memory of its people and, like memory, is associated with objects and places" (Rossi, 1982: 130). This relationship between the locus and the citizenry then becomes the city's 'predominant image' (Rossi, 1982: 130). Rossi (1982) asserts that both architecture and the landscape become part of the memory of a city, even when new memories emerge.

3. STUDY AREA

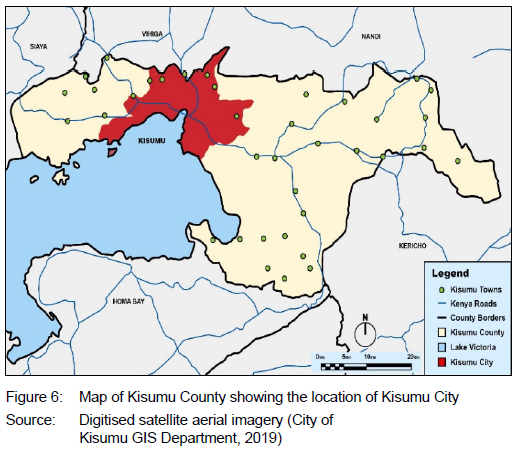

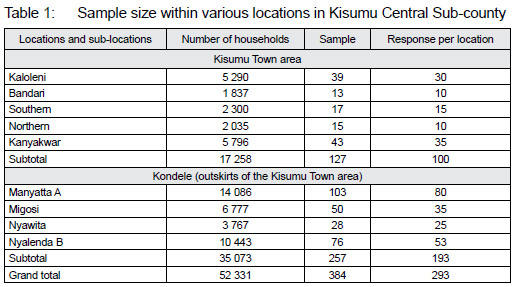

The study was conducted in Kisumu City, the third-largest urban area in Kenya. According to the Kisumu Integrated Sustainable Urban Development (ISUD) Plan Part 1 (AFD, 2013),1 Kisumu is the main administrative centre and headquarters of Kisumu County, and is 265km north-west of Nairobi. It lies on the eastern shores of Lake Victoria, the continent's largest freshwater lake. It is 1 146 m above sea level and is located 0o6' south of the equator and 34o45' east (AFD, 2013: 18). In 2022, the city covered an area of 417km2 (157km2of water and 260km2 of land) with a population estimated at over 500 000 people (Wamukaya & Mbathi, 2019: 81). According to Kenya's National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS, 2019: 20), Kenya's population and housing census of 2019 determined the study area (the Kisumu town area and its outskirts) to fall within the Kisumu Central Sub-County, which has a total population of 174 145, consisting of 84 155 males (48.3%), 89 985 females (51.7%), and 52 331 households. The Kisumu town area has a total population of 56 498 people and 17 258 households within a land area of 25.4km2. Sub-locations within the Kisumu town area include Kaloleni, Bandari, Southern, Northern, and Kanyakwar.

At the time of the study, Kisumu had several ongoing and already completed urban renewal projects in different sectors that resulted in great improvements. The projects include non-motorised transport (NMT) within the central business district (CBD) that comprises the improvement of pedestrian walkways, parking spaces, the construction of new markets, bus parks, the rehabilitation of public parks, the beautification of roundabouts, road islands, and proposed new affordable high-rise housing. The lakefront has also been earmarked for improvement, in addition to the port, which has been revamped. Previously stalled activities have commenced again. The projects were supervised by the Planning and Environment departments of Kisumu City, in addition to the Kisumu Urban Project (KUP) office, which was developed from the onset of the various projects.

4. METHODOLOGY

4.1 Research design

The study investigated the main aspects that constitute the formation of the landscape identity of the city of Kisumu, Kenya, by following a mixed-methods research approach, where quantitative and qualitative data were collected in parallel, analysed separately, and merged (Creswell, 2014: 45). In this study, a quantitative questionnaire survey was used to gather data on various natural, human-made, and sociocultural aspects that contribute to the formation of landscape identity. The qualitative interviews explored the various factors that contribute to the formation of landscape identity through photographic documentation of the various features of interest. The reason for collecting both quantitative and qualitative data is to elaborate on specific findings from the breakdown of the photographic documents and what constitutes the formation of landscape identity of Kisumu City as suggested by the respondents (Creswell & Plano-Clark, 2011).

4.2 Population, sampling method, and size

The Kisumu town area and the immediate neighborhoods surrounding the town area have undergone urban renewal and the households located within these two areas formed the population for this study. The KNBS' housing population census of 2019 showed 17 258 households located in Kisumu's central town area, and 35 073 households in the Kondele location on the outskirts of the Kisumu town area (see Table 1). Using simple random sampling, 384 household heads were selected to participate in the questionnaire survey because they were permanent residents within these neighborhoods, users of the renewed spaces, and aged 18 years and older. This ensured that the respondents had a heterogeneous socio-economic character. Similar studies that have used simple random sampling in the collection of data through field surveys include Baris et al. (2009: 725), Layson and Nankai (2015: 70-71), as well as Oktay and Bala (2015: 208).

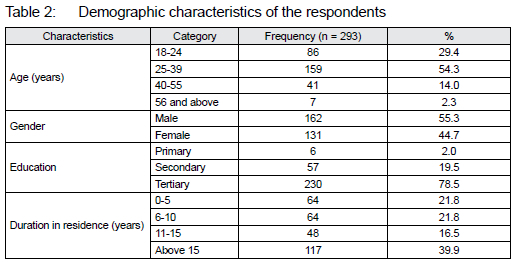

Using purposive sampling, based on their willingness, expertise, and professional roles in urban renewal, four (4) interviewees were selected as key informants (CGK 1 to CGK 4) from the Kisumu County government. The total sample size for the study was 388. The sample size is valid and within the recommended sample size of 381 for a population equal to or over 50 000 (Krejcie & Morgan, 1970: 608). Out of the 384 questionnaires issued, 293 were valid responses, showing a 76.3% response rate.

4.3 Data collection

From July to August 2021, through personal house visits, 384 questionnaires were distributed among the prospective respondents. A structured questionnaire is considered an effective data-collection method for measuring respondents' beliefs, attitudes, and opinions (Taherdoost, 2021: 14). The survey questionnaire was designed as a close-ended questionnaire. According to Harlacher (2016: 9-10), a close-ended questionnaire is easy to handle, simple to answer, and relatively quick to analyse because it reduces respondent bias.

The first section obtained the respondents' demographic information such as age, gender, educational background, and duration of residence in Kisumu City. Section 2 set two tick-box questions. The respondents were asked to mark 'yes' or 'no' on whether they were aware of the ongoing or completed urban renewal project in Kisumu City, and to what extent they agreed or disagreed with the statement that "Kisumu City had what made it unique and special before the onset of the renewal project". Section 3 set five Likert-scale statements on the aspects forming the identity of Kisumu City. Section 4 set 16 Likert-scale statements on the significance of various aspects of the natural, built, and socio-economic environments on the city's identity or image. Section 5 set two tick-box questions, where the respondents were asked to select which features, in their opinion, represented the best and worst aspects of Kisumu City's identity. Section 6 had 14 Likert-scale statements on features that have a strong symbolic meaning and contribute to the image and identity of Kisumu. Section 7 set 11 aspects that evoke individual/ collective memories and contributed to the image of Kisumu. For the Likert-scale questions, the respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement/significance or disagreement/non-significance with the statements from the measurements scale options.

During July and August 2022, semi-structured interviews were carried out with four officials of the County Government of Kisumu (CGK). This included questions on their opinion on which aspects (physical, sociocultural, economic, and meanings) constituted the image or character of Kisumu, and thus form its urban landscape identity.

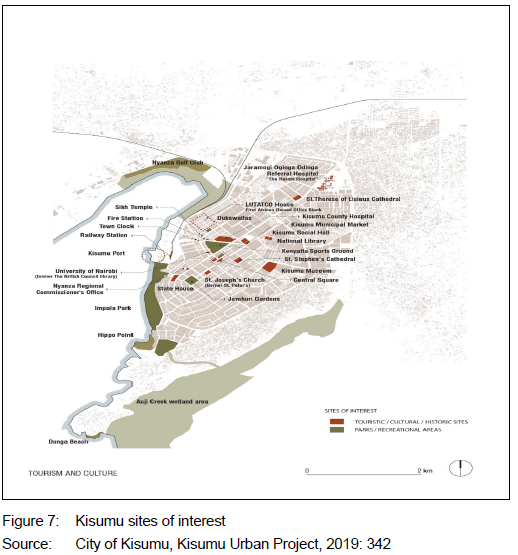

Figure 7 shows a map based on a report of the City of Kisumu's Urban Project (KUP, 2019: 342),2which featured sites of interest in Kisumu City. Most of the features mapped are considered to be forming the landscape identity of Kisumu City and were used in the survey questionnaire to investigate what constitutes the landscape identity of Kisumu City.

Figure 8 shows the photographs taken by the researcher based on a report of the KUP (2019: 342), which featured sites of interest in Kisumu City. These photos consist of the features that are considered to be forming the urban landscape identity of Kisumu City and were used in the survey questionnaire.

4.4 Data analysis and interpretation of the findings

The results from the structured questionnaires were analysed, using descriptive statistics. The Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 26 was used to generate frequencies and percentages of responses to analyse and report the respondents' profile. Percentages, mean scores, and standard deviation were generated to analyse the Likert-scale data, and report on the main aspects that constitute the formation of urban landscape identity in Kisumu City. Likert-type or frequency scales use fixed-choice response formats and are effective where numbers can be used to quantify the results of measuring behaviour, attitudes, preferences, and even perceptions (Wegner, 2012: 11). For the five-point statement options, the following scale measurement was used regarding mean scores, where 1 = strongly disagree (>1.00 and <1.80); 2 = disagree (>1.81 and <2.60); 3 = neutral (>2.61 and <3.40); 4 = agree (>3.41 and <4.20), and 5 = strongly agree (>4.21 and <5.00). For the three-point statement options, the scale ranged from 1 = low (25%-49%, not influential); 2 = moderate (50%-69%, somewhat influential), and 3 = high (70%-100 %, very influential).

5. RESULTS

5.1 Respondents' profile

Results on the demographic characteristics in Table 2 indicate that the vast majority of the respondents were male (55.3%), aged between 25 and 39 years (54.3%) and had a tertiary education (78.5%). Of the respondents, 98% were educated beyond primary school, as supported by the situational analysis report of the City of Kisumu (2019: 64), which indicated that over 70% of the residents in Kisumu City had at least a high school education. They were, therefore, expected to respond adequately to the study questions about the effect of urban renewal projects on the elements that form the city's image in Kisumu at the time of the study. Just over half (56.4%) of the respondents had resided in Kisumu for 11 years or longer, indicating that the respondents had lived in Kisumu long enough to respond to the image or character of the city, and possible changes to the city, due to urban renewal and its effects.

The four key informants (interviewees) from the County Government of Kisumu are officials involved in the Planning, Environment, and Kisumu Urban Project departments. These departments were directly charged with overseeing the planning and implementation of the various urban renewal projects.

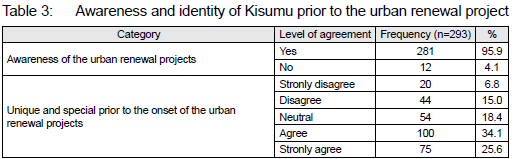

5.2 Identity of Kisumu prior to urban renewal

Table 3 shows that, in response to the question on awareness of the urban renewal projects in Kisumu, 95.9% were aware, while 4.1% of the respondents were unaware of the ongoing or completed urban renewal projects in Kisumu. Over half (59.7%) of the respondents agreed (34.1) and strongly agreed (25.6%) that Kisumu had what made it unique and special prior to the onset of the urban renewal project. The implication of this finding to the study is that the vast majority of the respondents agreed that Kisumu had a unique identity prior to the onset of the renewal project.

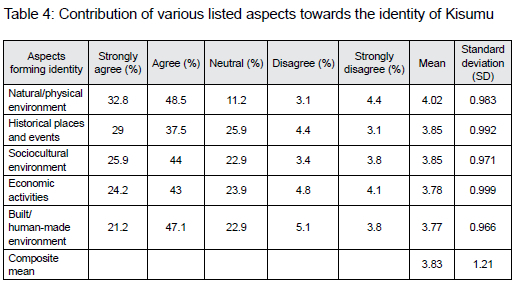

5.3 Contribution of the various listed aspects forming the urban landscape identity

The results in Table 4 show that, with an average mean score rating of 3.83, the respondents agreed that all five aspects formed the identity of Kisumu City. The vast majority of the respondents (81.3%) agreed that the natural/physical environment contributed the most (mean=4.02). Nearly a third of the respondents (68%) agreed that both historical places and events and the sociocultural environment equally contribute (mean=3.85) to the formation of the urban landscape identity of Kisumu.

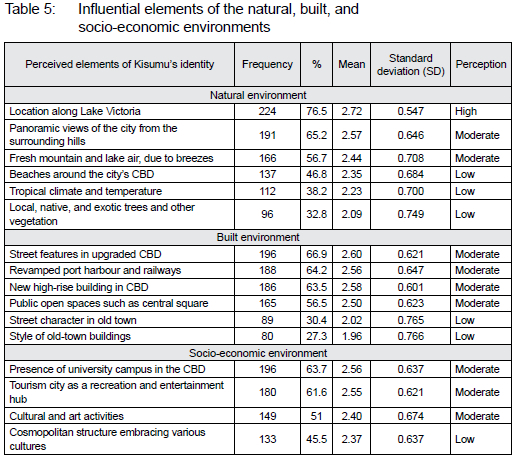

5.4 Influential elements of the natural, built, and socioeconomic environments

The findings in Table 5 show that 76.5% of the respondents perceived the location of the city along Lake Victoria as the most influential element of the natural environment in Kisumu City identity. Of the respondents, 65.2% perceived panoramic views of the city from the surrounding hills to have a moderate influence on Kisumu's identity. In the built environment, respondents almost equally perceived street features in upgraded CBD (66.9%); revamped port harbour and railways (64.2), and the new high-rise building in the CBD (63.5) to have a moderate influence on the city's identity. Kisumu City tourism sites, as a recreational and entertainment hub, and the presence of universities in the CBD, as elements of the socio-economic environment, are perceived to have a moderate (61.6% and 63.7%, respectively) influence in the city's identity.

The tropical climate and temperature, style of the old-town buildings and the character of the streets in the old town, and the cosmopolitan structure, which embraced various cultures, have a low influence on the urban landscape identity of city.

According to County official CGK 1, the image and character of Kisumu City is determined by the buildings along Oginga Odinga Street, the old provincial headquarters building, Jubilee Market building, University of Nairobi CBD building, especially the British Old Library building, parks such as the Uhuru Park, and the Clock Tower. Lake Victoria and its front, in terms of the beaches, is an important natural feature in contributing to the image and identity of Kisumu as a lakeside city.

According to County official CGK 3, important physical aspects that contributed to the image and identity of Kisumu are Lake Victoria and the old railway station.

"Lake Victoria is very important in giving Kisumu its lakeside status and has been important for local and foreign tourism besides economic benefits in terms of fishing for trade and transportation. The railway has been important in the historical development of Kisumu Town from colonial days. The important socio-cultural aspects in Kisumu are the fish-eating habits, especially by the local residents, the politics that is liked by the Luo-dominant local residents. Tourism within Kisumu is also an important aspect, although it has not fully picked up yet. Trade in Kisumu is mostly dominated by Asians, and the locals are mostly trading in small scale, but all the same, trade is an important economic aspect that contributes to the image and identity of Kisumu City" (CGK 3)

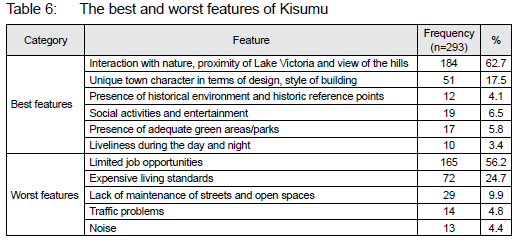

5.5 Perceived best and worst features of Kisumu

Table 6 shows that 62.7% of the respondents perceived interaction with nature, the proximity of Lake Victoria, and the view of the hills as the best feature of Kisumu. Of the respondents, 56.2% perceived limited job opportunities as the worst and expensive living (24.7%) as the second worst features of Kisumu City. This is in contrast with the earlier result in Table 4 that economic activities contributed to Kisumu's identity.

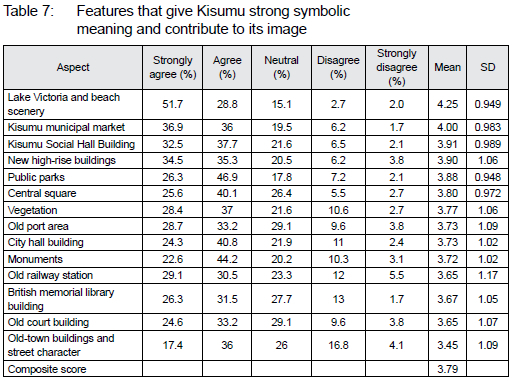

5.6 Features that gave strong symbolic meaning and contributed to the city's image

Table 7 indicates that Lake Victoria and its beach scenery (MS = 4.25) was the top first feature in its contribution of symbolic meaning to the residents and their contribution to the image of Kisumu. This implies the great value that the residents attach to the lake as a feature of the natural environment and hence, its great contribution to the formation of the urban landscape identity of Kisumu. Respondents agreed that several human-made structures such as the municipal market (MS = 4.00), the Social Hall (MS = 3.91), and new high-rise buildings (MS = 3.90), were ranked the top four features. The implication of these findings to the study were that there was a strong symbolic meaning attached to the natural and human-made features of the urban landscape which contributed to the image and identity of Kisumu.

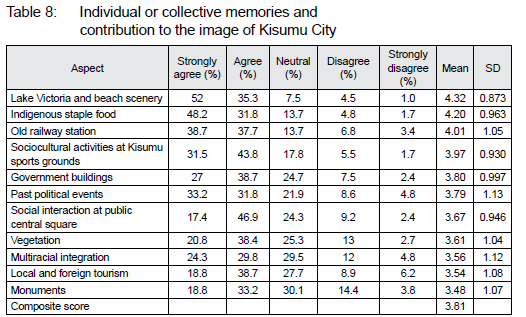

5.7 Individual or collective memories

The results in Table 8 show that various aspects of the natural, built/ human-made, and sociocultural environments within the urban landscape of Kisumu evoked individual or collective memories and contributed to the image of Kisumu in terms of its urban landscape identity. With a mean score rating above 4.20, the respondents strongly agreed that Lake Victoria and its beach scenery contributes the most. This confirms the great value that people attach to it in terms of symbolic meaning, as revealed in Table 7. Respondents agreed that indigenous staple food (MS = 4.20), which mostly consists of fish from Lake Victoria, the old railway station (MS = 4.01), and sociocultural activities at the Kisumu sports grounds (MS = 3.97) were the top four contributors to individual or collective memories and their contribution to the image of Kisumu.

The study aimed to identify the main aspects that constitute the formation of the urban landscape identity of Kisumu City in Kenya.

The findings of this study are biased towards respondents with a tertiary education. In previous studies, the level of education was shown to have a high impact on the perception of landscape identity (Kulozu-Uzunboy, 2021: 47). The researchers do, however, concur with Layson and Nankai (2015: 80) that the level of education increased awareness and participation in the survey. Baris et al. (2009: 732) as well as Gur and Heidari (2019: 138) found that people who have inhabited a particular place for a long time had more knowledge about various specific aspects of that place. This study supports this conclusion. In this study, 40% of the people had resided in Kisumu for more than 15 years, and were well versed in the various aspects that they revealed contributed to urban landscape identity.

6. DISCUSSION

Considering the urban renewal projects underway, the study started off by inquiring into the acknowledgment of the identity of Kisumu by its residents. The majority of the respondents agreed that Kisumu had what made it unique and special prior to the onset of the urban renewal projects. Shao et al. (2020: 3) assert that it is demanding and important to protect, improve, and even create landscape identity in the contemporary context of rapid urban development in cities, as it expresses the uniqueness of a city. This ensures that the cities are distinguished from other cities. Urban renewal in Kisumu should ensure that its unique image and identity are maintained, distinguishing it from other cities, and thus ensuring that it remains unique. The finding that Kisumu had what made it unique prior to the urban renewal is perhaps not surprising, considering that Saglik and Kelkit (2017: 37) posit that each city has an identity that is shaped over time and that, arguably, nowadays, ensures that it is remembered and lives with identities of the past. Baris et al. (2009: 731) state that cities also exhibit identities, depending on the functions and characteristics of the various sectors that they possess. A unique identity is not necessarily only shaped by physical characteristics, yet the field survey casts light on what the physical, symbolic, and memory aspects entail for residents of Kisumu. The field survey method could, however, not reveal all the reasons for the preferences recorded.

6.1 Which aspects contributed to the identity of Kisumu?

The main focus of the study was to inquire about the various aspects that contributed to the identity of Kisumu. The results show that the natural/ physical environment contributed the most to Kisumu's urban landscape identity. The sociocultural environment, the historical places and events, the built/human-made environment, and economic activities contributed moderately towards the urban landscape identity of the city.

Kisumu's location along Lake Victoria, as an element of the natural environment, had a high rating from the majority of the respondents. In addition, the panoramic view of the city from the surrounding hills also achieved a relatively moderate rating. In the historic city of Erzurum, Turkey, Kulozu-Uzunboy (2021: 46) similarly found that environmental identity elements were more significant to residents than sociocultural elements. In their study, elements of the natural environment such as mountains and the local cold climate ranked the highest among all the urban landscape identity elements. Interestingly, contrary to the study by Kulozu-Uzunboy (2021), in the present study, aspects of climate such as the tropical climate and temperature and fresh mountain and lake air due to breezes, received low ratings. This could be due to the fact that the survey was conducted during the winter months of July and August. Although it likely reflected the dominant sentiments of the residents towards Kisumu, a follow-up study in summer months could be useful in future research.

Regarding the elements of the built environment, when individually prompted, the new high-rise buildings in the CBD, street features in the upgraded CBD, the revamped port harbour and railways, and public open spaces such as the central

square, each achieved a moderate rating. Kisumu City tourism sites as a recreational and entertainment hub, and the presence of universities in the CBD as elements of the socio-economic environment achieved a moderate rating from the respondents. The findings in this study concur with Baris et al. (2009)and Kulozu-Uzunboy (2021: 59), who revealed that natural and human-made environment elements are more impactful, both individually and combined, than socio-economic elements on identity. However, this does not correspond with the fact that respondents cited limited job opportunities as the worst feature of Kisumu, and expensive living as the second worst feature. These ratings revealed that economic activities are important local considerations and are generally negatively perceived in Kisumu.

The results revealed that the most outstanding feature of Kisumu identified by the majority of the respondents was interaction with nature, proximity to Lake Victoria, and the view of the hills. This supports findings by Anastasiou

et al. (2021), Oktay (1998), as well as Oktay and Bala (2015), which indicated that the natural environment and geographical characteristics of the city had a high impact on the resulting image and urban landscape identity. Although this could be indicative of a city that has less interest in humanmade features (Norberg-Schulz, 1979), it is not the case in Kisumu, since many of the human-made features received a moderate rating. However, the interesting location and the character of the landscape (Norberg-Schulz, 1979; Ramos et al., 2016) are what distinguish Kisumu even more. The conclusion, according to the responses to various questions, is that the vast majority of the respondents mentioned Lake Victoria to be the most influential aspect in the formation of landscape identity, the highest ranked element with symbolic meaning, the highest ranked element that evoked individual or collective memories, and the best feature of Kisumu. This means that the

residents highly value the presence of Lake Victoria and the geographic location of the city of Kisumu as the major physical feature of the natural environment contributing to its urban landscape identity.

6.2 What contributes to meaning and memory in Kisumu?

Regarding the features that give Kisumu a strong symbolic meaning and contribute to its image, several elements received a moderate to high rating. At the time of the study, the vast majority of the respondents agreed with the contribution of the following elements: the central square, clock tower, old-town buildings and street character, public parks, vegetation (trees, grass, shrubs, and planters), new high-rise buildings, Lake Victoria and its beach scenery, the City Hall Building, the British Memorial Library Building, the old railway station, the old port area, the old court building, the Kisumu Social Hall, and the Kisumu municipal market. Oktay and Bala (2015: 201) revealed that natural and built/ human-made features have symbolic meaning in the image of a city. Their findings show that the city's unique location along the coast and on the slopes of the Besparmak range achieved a high rating by the vast majority (82%) of the respondents. The local characteristic vegetation, which includes olive trees, bougainvilleas, and carob trees, also made some contribution to the urban identity. They further state that urban identity is not only formed through identifiable attributes that are formal and memorable, but also through the symbolic meanings attached by the residents of the city. All the elements of the natural, human-made, and social environment of the city are also involved. These results support the city's local planning document (KUP, 2019: 342), which identifies the main sites of interest in Kisumu, and agrees with the strong symbolic meaning attached to them in this study. Other features that were not listed by the KUP (2019) such as the Maseno University Building, the new University of Nairobi Building, and the Kenya Commercial Bank Building were also mentioned and discussed as important and symbolic within Kisumu. However, less mention was made of specific vegetation characteristics, compared to the study by Oktay and Bala (2015).

Many aspects evoked individual or collective memories, and thereby contributed to the image of Kisumu. Lake Victoria and its beach scenery were ranked highest, due to its contribution to individual or collective memories and the resulting contribution to the image of Kisumu. This again shows the great value that the residents attach to this prominent geographic feature of the natural environment. It further confirms the symbolic meaning people attach to it, as revealed in the previous section. Indigenous staple food, which consists mostly of fish from Lake Victoria, was ranked second highest. This is indicative of the value that the local people place on this staple food and on activities and memories created around it. According to RoseRedwood, Alderman and Azaryahu (2008: 163), many studies of collective memory and urban space focus primarily on the monumental landscape, and less on the natural or geographical environment. In their study of collective memory within Hassan-Abad Square, Mianroudi et al. (2018: 17-18) concluded that forming memories requires a spatial reference. Urban spaces and places and their physical structures and spatial relationships are considered the spatial reference of urban memories. These authors concluded that collective memories occur in the context in which social interactions take place. A sociocultural context is, therefore, needed, in addition to the physical context of the city. The findings of this research are therefore revealing in the case of Kisumu, since the social interactions along the lake, including the consumption of fish from the lake, combined with the geographical prominence of the lake and possibly other spatial relationships and references, appear to shape collective memories at a landscape scale.

7. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study reiterated the importance of maintaining the perceived uniqueness associated with various cities in terms of landscape identity within the urban realms. The study will contribute greatly to the development of the urban landscape identity in the future through knowledge development. The lack of studies on landscape identity, especially in postcolonial Africa, can be remedied by findings from this study done in Kenya, which can form an important guide for future research.

The study concluded that, similar to other cities in the world, the urban landscape identity of Kisumu, as a postcolonial African city, is constituted by both natural and human-made elements. The natural environment and main geographic feature and its position on Lake Victoria came out strongly as very decisive aspects of the city's image. The connection of people to the natural environment and its importance in terms of their own identity is perhaps understated in the Global South, where socioeconomic challenges such as unemployment prevail and influence perceptions of cities. It would be important to conduct more studies within an African context to note whether these results are indicative of a continental cultural geographic preference or whether it is place-specific, especially considering the level of education bias in the respondents included in this study. Furthermore, more in-depth and longer term studies are required that could also investigate the motivations embedded through experiences, activities, and memories, and how this reveals symbolic meaning attributed to characteristics of place by the residents.

The study indicated the importance of analysing the aspects that constitute the formation of urban landscapes from time to time prior to major urban developments are undertaken, in order to get the residents' perspective of the environment. At the time of this study, there was no existing documented literature on the urban landscape identity of Kisumu. The study thus provided great potential and significantly contributed to identifying aspects that constitute the formation of Kisumu's urban landscape identity in the wake of ongoing and completed urban renewal projects. The study found that Lake Victoria is not only considered the most influential and best feature of Kisumu in terms of its scenery and view of the hills, a symbolic element evoking individual or collective memory among most residents, but also provides the staple food and fish that residents highly associate with it. Therefore the study recommends that the lake and its surroundings should be preserved, carefully managed, and maintained as a strong contributor to Kisumu's image and identity formation as a lakeside city. Built/human-made features that were mentioned as symbolic and that contributed to the individual or collective memories of residents within Kisumu over the years, such as the old railway station, and sociocultural activities at Kisumu sports grounds, should be further investigated in the wake of any redevelopments or urban renewal projects that are likely to affect their form, function, and related activities.

The study identified a connection between the urban landscape identity and the perceptions and relationships of the urbanites with their contextual environment. The article's stance is that urban renewal must consider this and respond to citizens' memory in designing the built environment. The study has an important contribution especially to the urbanising African cities, which are coupled with redevelopment, affecting their originality, especially the natural and human-made elements. Identifying natural landmarks is crucial for colonial African cities. The case study described how the Kisumu town is known not only because of other factors but also because of the Lake Victoria landscape that gives the urbanites identity and a sense of belonging. This insight may be applied to educate people about the importance and roles of natural landscapes as part of their identity, which may lead to people protecting the natural habitat in urban settings.

REFERENCES

AFD (Agence Frangaise de Développement). 2013. Kisumu: ISUD-Plan: Part 1. Integrated Strategic Urban Development Plan: Understanding Kisumu. Kisumu: AFD. [ Links ]

AMADO, M. & RODRIGUES, E. 2019. A heritage-based method to urban regeneration in developing countries: The case study of Luanda. Sustainability, 11, Article 4105. DOI: 10.3390/su11154105 [ Links ]

ANASTASIOU, D., TASOPOULOU, A., GEMENETZI, G., GAREIOU, Z. & ZERVAS, E. 2021. Public's perception of urban identity of Thessaloniki, Greece. Urban Design International, 27, pp. 18-42. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-021-00172-8 [ Links ]

ANDERSEN, H.S. 2003. Urban sores: On the interaction between segregation, urban decay and deprived neighborhoods. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing. [ Links ]

ANTROP, M. 2005. Why landscapes of the past are important for the future. Landscape and Urban Planning, 70, pp. 21-34. DOI:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2003.10.002 [ Links ]

BARIS, M.E., UCKAC, L. & USLU, A. 2009. Exploring public perception of urban identity: The case of Ankara, Turkey. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 4(8), pp. 724-735. [ Links ]

BEAUREGARD, R.A. & HOLCOMB, H.B. 1981. Revitalizing cities. Washington, DC: Association of American Geographers. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. 2014. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 4th edition. London, United Kingdom: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. & PLANO-CLARK, V.L. 2011. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd edition. London, United Kingdom: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

DIMUNA, K.O. & OMATSONE, M.E.O. 2010. Regeneration in the Nigerian urban built environment. Journal of Human Ecology, 29(2), pp. 141-149. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2010.11906256 [ Links ]

EGOZ, S. 2013. Landscape and identity: Beyond a geography of one place. In: Howard, P., Thompson, I. & Waterton, E. (Eds). The Routledge companion to landscape studies. New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 272-285. [ Links ]

ENACHE, C. & CRACIUN, C. 2013. The role of landscape in the identity generation process. Journal of Social and Behavioural Sciences, 92, pp. 309-313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.677 [ Links ]

EREN, I.O. 2014. What is the threshold in urban regeneration projects in the context of urban identity? The case of Turkey. Spatium International Review, no 31, pp. 14-21. https://doi.org/10.2298/SPAT1431014E [ Links ]

GUR, E.A. & HEIDARI, N. 2019. Challenge of identity in the urban transformation process: The case of Celiktepe, Istanbul, Turkey. ITU A/Z, 16(1), pp. 127-144. DOI: 10.5505/itujfa.2019.47123 [ Links ]

HARLACHER, J. 2016. An educator's guide to questionnaire development (REL 2016-108). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. [Online]. Available at: <http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs> [Accessed: 21 October 2021]. [ Links ]

KAYMAZ, I. 2013. Urban landscapes and identity. In: Özyavuz, M. (Ed.). Advances in landscape architecture. Rijeka: InTechOpen, pp. 739-760. DOI: 10.5772/55754 [ Links ]

KNBS (KENYA NATIONAL BUREAU OF STATISTICS). 2019. Kenya Population and Housing Census, Volume II. Distribution of population by administrative units. [ Links ]

KREJCIE, R.V. & MORGAN, D.W. 1970. Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), pp. 607-610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308 [ Links ]

KULOZU-UZUNBOY, N. 2021. Determining urban identity of historical city from inhabitants' perspective: Erzurum, a case from Asia Minor. Asian Research Journal of Arts and Social Sciences, 13(2), pp. 46-63. https://doi.org/10.9734/arjass/2021/v13i230213 [ Links ]

KUP (CITY OF KISUMU, KISUMU URBAN PROJECT). 2019. Situational Analysis Report. Preparation of Local Physical Development Plans for Kisumu City. [ Links ]

KUP (CITY OF KISUMU, KISUMU URBAN PROJECT). 2020. Building the Vibrant Lake Metropolis, Kisumu City Local Physical and Land Use Development Plans, Public Report. [ Links ]

LAYSON, J.P. & NANKAI, X. 2015. Public participation and satisfaction in urban regeneration projects in Tanzania. The case of Kariakoo, Dar es Salaam. Urban Planning and Transport Research, 3(1), pp. 68-87. DOI: 10.1080/21650020.2015.1045623 [ Links ]

LEON, R.M., BABERE, J. & SWAI, O. 2020. Implications of cultural heritage in urban regeneration: The CBD of Dar es Salaam. Papers of Political Economy, 63, Article 9171, pp. 1-18. DOI: 10.4000/interventionseconomiques.9171 [ Links ]

LYNCH, K. 1960. The image of the city. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [ Links ]

MIANROUDI, N.H., MAJEDI, H., ZARABADI, Z.S. & ZIARI, Y. 2018. Exploring the concept of collective memory and its retrieval in urban areas with semiotics approach (Case study: Hassan-Abad Square). The Scientific Journal of NAZAR Research Center for Art, Architecture and Urbanism, 14(56), pp. 15-30. [ Links ]

NJOKU, C. & OKORO, G.C. 2014. Urban renewal in Nigeria: Case study of Lagos state. Journal of Environmental Science and Water Resources, 3(7), pp. 145-148. [ Links ]

NORBERG-SCHULZ, C. 1979. Genius loci: Towards phenomenology of architecture. New York, NY: Rizzoli. [ Links ]

OKESLI, D.S. & GURCINAR, Y. 2012. An investigation of urban image and identity. Findings from Adana, 21(1), pp. 37-52. [ Links ]

OKTAY, D. 1998. Urban spatial patterns and local identity: Evaluations in a Cypriot town. Open House International, 23(3), pp. 17-23. [ Links ]

OKTAY, D. & BALA, H.A. 2015. A holistic research to measuring urban identity findings from Girne (Kyrenia) area study. International Journal of Architectural Research, 9(2), pp. 201-215. https://doi.org/10.26687/archnet-ijar.v9i2.687 [ Links ]

PLOEGMAKERS, H. 2015. Evaluating urban regeneration: An assessment of the effectiveness of physical regeneration initiatives on run-down industrial sites in the Netherlands. Urban Studies Journal, 52(12), pp. 2151-2169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014542134 [ Links ]

PROSHANSKY, H.M., FABIAN, A.K. & KAMINOFF, R. 1983. Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 3, pp. 57-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(83)80021-8 [ Links ]

RAMOS I.L., BERNARDO, F., RIBEIRO, S.C. & E, V.V. 2016. Landscape identity: Implications for policy making. Land Use Journal, 53(2016), pp. 3-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.01.030 [ Links ]

RELPH, E. 1976. Place and placelessness. London: Pion. [ Links ]

ROSE-REDWOOD, R., ALDERMAN, D. & AZARYAHU, M. 2008. Collective memory and the politics of urban space: An introduction. GeoJournal, 73, pp. 161-164. DOI: 10.1007/s10708-008-9200-6 [ Links ]

ROSSI, A. 1982. The architecture of the city. New York, NY: Opposition Books. [ Links ]

SAGLIK, E. & KELKIT, A. 2017. Evaluation of urban identity and its components in landscape architecture. International Journal of Landscape Architecture Research, 1(1), pp. 36-39. [ Links ]

SHAO, Y., LANGE, E., THWAITES, K., XUE, Z. & XU, X. 2020. Understanding landscape identity in the context of rapid urban change in China. Land, 9(9), p. 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9090298 [ Links ]

STOBBELAAR, D.J. & HENDRIKS, K. 2004. Reading the identity of place. Multiple Landscape Conference, Wageningen, 7-9 June 2004. [ Links ]

STOBBELAAR, D.J. & PEDROLI, B. 2011. Perspectives on landscape identity: A conceptual challenge. Landscape Research, 36(3), pp. 321-339. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2011.564860 [ Links ]

TAHERDOOST, H. 2021. Data collection methods and tools for research. International Journal of Academic Research in Management, 10(1), pp.10-38. [ Links ]

WAMUKAYA, E. & MBATHI, M. 2019. Customary system as 'constraint' or 'enabler' to peri-urban land development: Case of Kisumu City, Kenya. Town and Regional Planning, 75, pp. 77-90. https://doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp75i1.9 [ Links ]

WEGNER, T. 2012. Applied business statistics methods and Excel-based applications solutions manual. 4th edition. Cape Town, South Africa: Juta. [ Links ]

ZHENG, W., SHEN, G.Q., WANG, H., HONG, H. & LI, Z. 2017. Decision support for sustainable urban renewal: A multi-scale model. Land Use Policy, 69, pp. 361-371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.09.019 [ Links ]

ZIYAEE, M. 2018. Assessment of urban identity through a matrix of cultural landscape. Cities, 74, pp. 21-31. DOI: 10.1016/j.cities.2017.10.021 [ Links ]

Received: July 2023

Peer reviewed and revised: September 2023

Published: December 2023

* The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

1 This source is not available online but can be requested from the author.

2 This source is not available online, but can be requested from the author.