Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Town and Regional Planning

On-line version ISSN 2415-0495

Print version ISSN 1012-280X

Town reg. plan. (Online) vol.80 Bloemfontein 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp80i1.6

REVIEW ARTICLE

The South African IDP and SDF contextualised in relation to global conceptions of forward planning – A review

Die Suid-Afrikaanse GOP en ROR gekontekstualiseer teenoor globale konsepte van vooruitbeplanning

Thlophiso ea IDP le SDF Tsa Aforika borwa ka papiso le litloaelo tsa lefatshe ka bophara tsa therelo pele - tlhahlobo

Francois Wüst

Chief Town and Regional Planner, Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning, Western Cape Government (writing in personal capacity), Private Bag X9086, Cape Town, 8000. Email: francois.wust@westerncape.gov.za

ABSTRACT

Municipalities across the globe require good planning instruments to address the need for medium- to long-term planning. In South Africa, the Integrated Development Plan (IDP) and the Spatial Development Framework (SDF) could be regarded as the two main instruments in the system of forward planning, as mandated by the national government. The system, however, is over two decades old and is not without its detractors and, as such, fresh reviews are warranted. In investigating the instruments, it is the purpose of this review article, as a first step, to identify, compare and analyse several terms or phrases used in global literature in connection with forward planning, in particular blueprint or master planning, comprehensive planning, integrated planning, strategic planning, strategic spatial planning, and community planning. Finally, the article explores the IDP and SDF against the insights gained from this process.

Keywords: Integrated Development Plan, IDP, Spatial Development Framework, SDF, forward planning, municipal planning, comprehensive planning, master planning, blueprint planning, strategic planning, integrated planning

OPSOMMING

Munisipalitiete regoor die wêreld benodig goeie beplanningsinstrumente ten einde die behoefte aan medium- en langtermynbeplanning aan te spreek. In Suid-Afrika kan die Geïntegreerde Ontwikkelingsplan (GOP) en die Ruimtelike ontwikkelingsraamwerk (ROR) as die twee primêre instrumente beskou word wat in die sisteem van vooruitbeplanning deur die nasionale regering voorgeskryf is. Die sisteem is egter meer as twee dekades oud en nie sonder kritici nie. Gevolglik is 'n vars oorsig geregverdig. As 'n eerste stap in die ondersoek van die instrumente is dit die doel van die oorsigartikel om 'n aantal terme uit die internasionale literatuur wat verwant is aan vooruitbeplanning te identifiseer, te vergelyk en te analiseer. Die terme is bloudruk of meesterbeplanning, komprehensiewe beplanning, geïntegreerde beplanning, strategiese beplanning en ruimtelike strategiese beplanning. Laastens word die GOP en ROR vergelyk met die insigte wat uit die proses na vore getree het.

Sleutelwoorde: Geïntegreerde Ontwikkelingsplan, GOP, Ruimtelike Ontwikkelingsraamwerk, ROR, vooruitbeplanning, bloudrukbeplanning, meesterbeplanning, komprehensiewe beplanning, geïntegreerde beplanning, strategiese beplanning, ruimtelike strategiese beplanning

Bomasepala ka bophara ba lefatshe, ba hloka lisebelisoa tsa maphomella tsa thero ea libaka ele ho rarolla tlhokeho ea meralo ea nakoana ho isa ho ea nako e telele. Ka hara Afrika Boroa, Moralo wa Ntsetsopele e Kopanetsoeng (IDP) le Moralo wa Ntsetsopele ea Libaka (SDF), di ka nkoa e le lisebelisoa tse peli tse ka sehloohong tsamaisong ea moralo oa tsoelopele, joaloka ha ho laetsoe ke 'muso oa naha. Leha ho le joalo, tsamaiso ea naha e na le lilemo tse fetang mashome a mabeli 'me ha e na bahanyetsi, ka hona, litlhahlobo tse ncha lia hlokahala. Ke morero oa sengoliloeng sena sa tlhahlobo ho batlisisa lisebelisoa, e le ho khetholla, ho bapisa le ho sekaseka mantsoe kapa lipoleloana tse 'maloa, tse sebelisoang lingoliloeng tsa lefats'e mabapi le therelo pele, haholo-holo ho ipapisitsoe le meralo ea libaka tse kholo, meralo e pharaletseng, meralo e kopanetsoeng, meralo ea maano, meralo ea libaka le meralo ea Sechaba. Qetellong, sengoloa se hlahloba IDP le SDF khahlanong le lintlha tse fumanoeng phuputsong ena.

1. INTRODUCTION AND RATIONALE

1.1 Background

Globally, municipalities are responsible for bringing essential services to households and businesses on a sustainable basis, as well as being tasked with a diverse range of other responsibilities. While the specific mandates may vary across the world, it is clear that municipalities need to continuously deal with complex challenges while being able to anticipate and plan for the future.

To ensure that this need for planning is addressed, many national or regional governments devised specific instruments to be used by municipalities. The design and underlying philosophy of these instruments appear to vary significantly across the globe. In Europe alone, over 250 instruments have been identified (Nadin et al., 2018: viii).

In South Africa, the Integrated Development Plan (IDP) and the Spatial Development Framework (SDF) are the two main forward planning instruments created and prescribed for the whole country. The IDP is the 'integrated' and 'strategic' plan prepared for the term of office of a newly elected council. By contrast, the SDF is generally regarded as the longer term plan focusing more on spatial planning. Both the IDP and SDF became embedded as permanent features of the South African local government and planning landscape.

Based on the legislation, many would argue that there is, in fact, only one instrument, namely the IDP, and that the SDF is merely a component of the IDP. It is not the intention of the author to address the question regarding the hierarchical relation between the IDP and SDF in detail. The point of departure of the paper is rather the 'practical' reality that the two instruments are mostly utilised as two separate instruments. The IDP and SDF are prepared through separate processes and at different times or cycles.

As such, an interesting, but not often explored, perspective is to consider the two instruments holistically, and whether the situation constitutes an integrated and optimal system.

1.2 Objectives

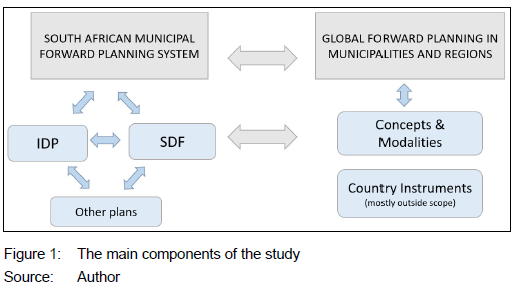

The overarching objective of this article is to open up a discussion regarding the IDP and SDF as components of a coherent and optimal forward planning system for the municipal sector in South Africa. However, the article will approach this broader project starting from one specific perspective, namely an investigation into the global terminology and modalities of forward planning in municipalities or regions. Figure 1 illustrates this approach, including the main components.

As such, it is fully acknowledged that, in order to do justice to the 'bigger project', several other approaches should eventually be followed. Examples of such approaches are a review of instruments as employed across the globe; gauging the perspectives from practitioners across the country, and case studies of specific municipalities assessing and comparing the IDP and SDF. While each of these approaches could form the basis of a study on its own, this article only deals with the global terminology and modalities and what can be learned when applied to the South African instruments. It is, therefore, also acknowledged that the deductions from the research will be of an explorative nature.

In exploring the main question and using the method as specified, the article is structured around the following:

• providing a brief background to the IDP and SDF as instruments for forward planning in South African municipalities;

• arguing that a holistic and comprehensive assessment of the IDP and SDF is required (including a brief overview of the critique by South African scholars);

• providing an overview of international terminology related to forward planning;

• analysing how the South African IDP and SDF (and approach

as a whole) relate to the international terminology and modalities, and lastly,

• exploring some deductions from the analysis and proposing lines for further enquiry.

From a scholarly perspective, the research objective presents some further challenges: first, it straddles different academic fields, namely planning, management and public administration; secondly, various terms and modes of planning need to be investigated; thirdly, two instruments are being explored simultaneously, and lastly, prior critical attempts to analyse the IDP and SDF in relation to each other and jointly as part of a municipal planning system, appear to be limited.

However, in support of the topic, it can be argued that these challenges contribute to underline the need and value of such an investigation. The topic certainly is relevant, as effective planning in South Africa's approximately 280 municipalities affects the future well-being of most, if not all, citizens, as well as the local economy and the environment. In other words, the future of South Africa's municipalities is, partially at least, being determined by the quality of these processes.

The methodology of the research primarily entails a focused literature study. However, underpinning the article is an evaluative and argumentative approach, as an effort is made to identify relevant literature describing the terms, and then to compare the South African instruments with the observations. A historic contextualisation is also inherent to the work, to both the terminology and the historic evolution of the IDP and SDF.

In terms of a national government being in a position to design and dictate instruments, a very relevant article from Acheampong and Ibrahim (2016) should be noted. They investigated the Ghanaian planning system, which, according to their analysis, featured two systems, one for strategic planning and one for spatial planning. Their article is significantly titled "One nation, two planning systems?" and they observed the following:

"Under the established notion of the 'spatial' being distinctively separate from the 'socio-economic' in planning, these two systems deploy separate institutional and legal arrangements as well as policy instruments to accomplish the task of planning. Within this context, mechanisms to ensure effective policy integration were found to be weak and ineffective." (Acheampong & Ibrahim, 2016: 1).

2. FORWARD PLANNING INSTRUMENTS (AND SYSTEM) IN SOUTH AFRICA

This section provides an overview of the IDP and SDF as the two main South African forward planning instruments and concludes with an overview of the critique levelled by local authors and scholars in respect of the instruments.

2.1 The IDP

In the 1998 White Paper on Local Government (RSA, 1998: 19), which preceded the Municipal System Act, the need for integrated development planning was motivated as follows:

"Municipalities face immense challenges in developing sustainable settlements which meet the needs and improve the quality of life of local communities. To meet these challenges, municipalities will need to understand the various dynamics operating within their area, develop a concrete vision for the area, and strategies for realising and financing that vision in partnership with other stakeholders. Integrated development planning is a process through which a municipality can establish a development plan for the short-, medium- and long-term."

The South African Integrated Development Plan (IDP) was born out of the local government transformation process and was first introduced in 19961 as a fresh and innovative instrument to deal with integrated planning and transformation in the newly established municipalities. It was part of an optimism following the 1994 transition regarding the potential of local government in South Africa, as is evident from the following observation from Parnell and Pieterse (2002: 82):

"In an obvious break with the past, the post-apartheid state has radically transformed and extended the role of local government. Now the municipality becomes the primary development champion, the major conduit for poverty alleviation, the guarantor of social and economic rights, the enabler of economic growth, the principal agent of spatial or physical planning and the watchdog of environmental justice."

The IDP in its final form has been mandated in Chapter 5 of the Municipal System Act, Act No. 32 of 2000, which should be read in conjunction with its regulations,2published in 2001 in terms of section 120(4) of the Act. Chapter 5 remains very relevant in describing the intentions and principles of the IDP.

As such, the IDP was designed to offer a comprehensive solution for dealing with the challenges faced by municipalities. Furthermore, it was believed that municipalities would be able to fulfil a truly developmental role. Over the past 20 years, the IDP has been fully mainstreamed, and it would be fair to observe that all the municipalities in the country should have an IDP. The IDP forms part of the annual financial audit and the basis of the performance management of senior managers.

2.2 The SDF

According to the IDP legislation (the Municipal System Act, as described above), the spatial implications were to be covered by the Spatial Development Framework (SDF),3which is prescribed as a core component of the IDP and which has to be reflected in the IDP (Section 26). The Municipal System Act regulations (the Local Government: Municipal Planning and Performance Management Regulations, 2001) further unpacked the requirements for an SDF (Section 2(4)).

The general understanding of the SDF4 is that it guides where and what type of development can or should take place over a 10 to 20 years' planning horizon.5 To the custodians of urban, social, and physical infrastructure (including transport, water, electricity, housing, and education, to mention a few), the SDF provides a scenario for future development that forms a basis for this more specialised planning.

While the concept of an SDF was firmly established in the Municipal System Act and its regulations, the requirements for an SDF were amplified in 2013 through the adoption of the Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act, Act 16 of 2013 (SPLUMA). SPLUMA maintained the basic status quo as determined in the Municipal System Act, namely that the SDF is a component of the IDP. For instance, Section 20(2) of SPLUMA states: "The municipal spatial development framework must be prepared as part of a municipality's integrated development plan6 in accordance with the provisions of the Municipal Systems Act".

2.3 Other plans related and complementary to the IDP and SDF

It should be noted from the Municipal System Act (and SPLUMA) that several other plans or products must form part of or be reflected in the IDP and SDF. The following plans, sometimes referred to as sector plans, are examples of additional plans required: Disaster Risk Management Plan, Integrated Transport Plan, Water Services Development Plan, Housing Sector Plan (or chapter), an Economic Development Strategy, and various environmental plans including an Environmental Management Framework, an Air Quality Management Plan, and an Integrated Waste Management Plan.

In addition, two very important but interlinked components to be addressed through more detailed planning are infrastructure planning and budgeting for investment. Both the Municipal System Act and SPLUMA emphasise the need for these to be addressed, and it should occur via the capital investment framework (CIF),7 or capital expenditure framework (CEF)8being the prescribed instrument.9Furthermore, a 'long term financial plan' (LTFP), which appears to overlap with the objectives of an expenditure or investment framework, has always been required as a key component of an IDP.

While Todes (2011: 12) noted that "a number of cities in South Africa are exploring links between spatial planning, infrastructure and budgets", it appears that only a few municipalities had formal CEFs, CIFs or LTFPs prepared. Many municipalities, however, had master plans for specific engineering services produced (e.g., water, waste water, or electrical reticulation).

It is, therefore, clear that the IDP and SDF do not stand alone in the arena of municipal forward planning and that there will always be a need to summarise, integrate, align, and update a diverse set of plans. It is also not only a matter of these plans being summarised in the IDP, but rather that findings from the sector plans should truly impact on the proposals and priorities as set out in the IDP and SDF.

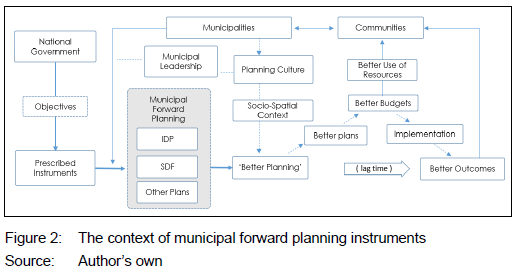

The concept of municipal forward planning, and specifically the IDP and SDF and related plans, can be presented diagrammatically (see Figure 2).

2.4 Critique of the IDP, SDF and the South African planning 'system'

To further frame this article, it is important to explore some of the questions and/or criticism levelled in relation to the IDP, the SDF, and the forward planning system in general.

Mabin (2002: 49) stated the following regarding the IDP: "[the IDP is]... an idea with powerful antecedents popped into law at the last minute" and "...perhaps what has been missing is a wider scrutiny of the IDP trajectory, which has resulted in the pursuit of some poorly tested ideas." Harrison (2006: 204) put the question regarding the success of the IDP as follows: "For planning the key question is whether the requirement to produce an IDP was one of the burdens on municipalities that detracted from their ability to deliver basic services, or whether the situation would have been worse without IDPs." In this regard, for Harrison, the "jury was still out". He also referred to governments often having over-confidence in reform measures and the common failure to anticipate unintended consequences.

De Visser (2009: 15) emphasised the institutional 'fault lines' such as the large municipal areas representing regions. He also highlighted the unrealistically high expectations from the IDP, as the IDP has to be prepared within very tight time frames after the election of a new council, creating a 'pressure cooker' situation (De Visser, 2009: 23).

Coetzee (2010: 25) referred to the IDP as

"an octopus with too many tentacles - a system that not only created confusion and frustration in local governments, but an impoverished system that is not well-understood, supported and respected by the leaders and participants."

More in general, Coetzee (2012: 14) described various gaps in South African transformation, among others a 'policy-implementation' gap and a 'planning system' gap:

"After almost two decades of learning, practising, and trial-and-error, planners and government leaders still And it difficult to effectively implement the new planning system and to bring about the change that is needed."

When it comes to SDFs, Coetzee (2012: 15) argued:

"SDFs are isolated and divorced from the overarching City Development Strategies, IDPs and the related sector plans and strategies."

From a detailed study of eight South African cities, Du Plessis (2019: iii) observed that SDFs had only limited impact relative to its intended objectives. He also listed several deficiencies in SDFs, among others the absence of proper linkages to the capital investment framework and the IDP (Du Plessis 2019: 215-216).

Of course, not only planning scholars commented on some of the shortcomings and flaws of the South African forward planning approach and outcomes. Space does not allow for a detailed discussion, but, briefly, the Back-to-Basics programme recognised that basic service delivery in South African municipalities has regressed and is under enormous strain. The programme tried to refocus municipalities on getting the basics right. The NDP 2030 (RSA 2012) recognised both the importance and the failings of planning in addressing the legacies of apartheid planning. Several other initiatives also addressed the challenges, such as the Integrated Urban Development Framework (2016) and the recently adopted National Spatial Development Framework (2020). However, to the author's knowledge, none of these initiatives fundamentally revisited or challenged the IDP or SDF as instruments. That said, the recent introduction of the 'One Plan' concept, which is linked to the District Delivery Model, should be noted. The One Plan, however, is directed at the district level and is, therefore, regarded as outside the scope of this article.

3. GLOBAL CONCEPTS: INVESTIGATION AND APPLICATION

At this point, the article shifts focus to the global terminology concerning municipal forward planning, which is then applied to the South African situation. The approach requires three stages: first, identify the most relevant concepts or modalities and put it in historical context; secondly, explore each concept in greater detail in trying to understand its meaning and significance, and thirdly, comparing the South African scenario with the global concepts as discussed. The first two stages required an extensive literature study, while the third stage represents a combination of additional literature, interpretation of the legislation, and reflection on personal experience.

The six terms being investigated are all potentially (or historically) used in association with 'planning' and, as such, they are types or modes of planning. It would, therefore, be worthwhile to first briefly explore the general meaning and other aspects of planning.

One definition that, for its simplicity, stands out for the current author, is that of Wildavsky (1973: 128) who described planning as "an aspiration to control the future". He went on to argue: "Virtually everyone would agree that planning requires: (1) A specification of future objectives and (2) a series of related actions over time designed to achieve them" (Wildavsky, 1973: 131). This definition only serves as a point of departure and will be augmented during the ensuing investigation.

The question 'What is planning?' is often closely linked to the question 'Who plans?'. First, forward planning in the municipal domain can and should also be contextualised in its relation to 'management'. In this regard, the work of Henri Fayol, who was regarded as the "father of modern management" (Wren & Bedeian, 2009: 226) is worthwhile noting. He regarded planning as the first pillar of management. Every manager should, therefore, have a good understanding of planning and any organisation should regard planning as an integral part of management. It can similarly be argued that, for forward planning in municipalities to be truly strategic and integrated, it should be driven by top management,10 irrespective of their background and qualifications.11

Planning in municipalities should also be recognised as a political process. Altshuler's excellent book was aptly titled: The city planning process: A political analysis (1965). In terms of the role of planning and planners, he observed, among others, that municipal councillors choose who they listen to and it might not always be the planners (Altshuler 1965: 330). The question is thus not only 'Who plans?' but 'Who, with the power to implement, listens...".

Lastly, before delving into the specific terminology, the author's use of 'forward planning' as an umbrella term in this article might require some clarification. A single term had to be employed whilst keeping it distinct from the other terms being investigated. 'Forward planning' was selected as it is regarded as a fairly neutral term and is not often used (perhaps because it represents a form of tautology). As such, for the purpose of this article, the term 'forward planning' is used in broad terms and refers to multi-sector integrated and strategic medium- and long-term planning in municipalities. The term 'forward planning' also preserves a distinction with land-use management.

In terms of the terminology that will be investigated, an extensive overview of papers and other publications was conducted. It was concluded that the most relevant terms or phrases related to municipal forward and crosssector planning instruments, are:

• blueprint or master planning;

• comprehensive planning;

• strategic planning;

• integrated planning;

• strategic spatial planning, and

• community planning.

These could also be viewed as modes of forward planning. However, the terms can be broad and vague and when one starts to unpack them, things rapidly become confusing and challenging. Several authors echo this sense of ambiguity, even frustration, for instance:

• "There are no single universal definitions for strategy and strategic planning. Various authors and practitioners use the term differently" (Albrechts, 2004: 746).

• "Strategic spatial planning (SSP) is not a well-defined end product or process but rather a loose framework of approaches to planning" (Persson, 2020: 1183).

• "Integrated planning is an elusive ideal: it is difficult to define and even harder to implement" (Henderson & Lowe, 2015: 1).

As such, many respected scholars appear to agree that the definitions are challenging. Against this background, the article, and specifically the endeavour to disentangle some of the terminology, can be linked to the field of 'analytical philosophy' as described by Lord (2014: 35). In addressing the challenges in defining the theory of planning, he invoked 'analytical philosophy' in highlighting the need to analyse language. According to this perspective, language and meaning should be 'demystified' by distinguishing it from local or theoretical interpretations, or as Lord (2014: 35) put it: "Our task is simply to bring words back from their metaphysical to their everyday use." The interpretation of terminology is thus extremely important and part of philosophy is to analyse the meanings that have been attached to the terms and then to narrow down what is the true and consistent meaning of each term. Without such a process, debates are merely fuelled by people having different conceptions of key words.

The next section deals with the six concepts, as identified. The sequencing is broadly historical.

3.1 Blueprint or master planning

3.1.1 Global conception

'Blueprint' and 'master' planning are terms that are almost identical in meaning. Alexander (1994: 373) described blueprint plans (which would probably equally apply to 'master' plans) succinctly as "presenting end-state images of desired outcomes". Towards the end of the 20th century, 'blueprint' and 'master' planning became associated with a modernist and positivist perspective of planning. There was a strong view among some scholars that these approaches were outdated, dysfunctional and had to be replaced. For instance, Friedman (1993: 484) argued:

"The old planning model, rooted in nineteenth-century concepts of science and engineering, is either dead or severely impaired. Though still practiced, it has become largely irrelevant to public life."

Todes et al.12 (2010: 415) described a major criticism in respect of master planning, namely that "master plans were too rigid and static [and] took years to produce and were soon out of date". Todes (2011: 4) also stated that the 'master planning' approach "did not address the real conditions and dynamics of rapidly growing cities in developing countries, and the extent of poverty, inequality and informality."

Despite all the criticism levelled against master and blueprint planning, it can be argued that this type of planning, in some form or another, will always be necessary. Many large-scale, ambitious, and celebrated planning projects across the world, such as the replanning of Paris, New York's Central Park, and, more locally, Gauteng's Gautrain, and the Cape Town Waterfront, would never have materialised if there was no large-scale blueprint or master planning.

3.1.2 Applied to the South African scenario

While the IDP can certainly not be regarded as a blueprint plan, SDFs appear to be at least partly 'blueprint' as SDFs, to the extent that they address a sufficient level of detail, guide where development could or should take place. Unfortunately, the value of SDFs as blueprint plans in the positive sense is sometimes limited, due to the issue of scale, as mentioned by De Visser (Section 2.4).

Based on extensive interviews with municipal planners, Van der Berg (2019: 318) noted:

"...SPLUMA requires municipalities to develop 'one main SDF which must cover too vast an area to provide any detailed planning direction.' Such detailed information is only included in precinct plans, but precinct plans are not compulsory. SPLUMA merely requires municipal SDFs to identify the areas where precinct plans must be developed."

Similarly, Todes et al. (2010: 416) observed in the South African context: "In practice, many of the spatial frameworks which were produced in the late 1990s and early 2000s were very broad plans that were too loose to achieve their intentions." In the same article, the authors explored the need for local SDFs. It should be noted that, to counter this issue, many SDFs, where funds were available, include additional plans per town or settlement. However, sufficient funds are seldom available to engage deeply and extensively with each town or settlement. 13

3.2 Comprehensive planning

3.2.1 Global conception

Perhaps the most elusive concept, the second term to explore, is 'comprehensive planning'. From at least the 1950s, comprehensive plans were, and still appear to be, the most prevalent forward planning instrument in the USA. Comprehensive planning is also a term often referred to in scholarly articles, although the use can be ambiguous and inconsistent.

Comprehensive planning as a concept can be understood, first, as an approach covering multiple sectors, dimensions, and objectives. In line with this understanding, Altshuler (1965: 299) described comprehensive planning by contrasting it with specialist planning and specialist professionals. However, when referred to by critical scholars, comprehensive planning also appears to refer to blueprint or master planning, when things are planned too detailed and rigidly. Lastly, it appears to imply that large areas are covered (as opposed to spatially targeted areas).

Comprehensive planning somehow became associated with a modernist, technocratic and top-down doctrine and has, in this context, been deeply criticised by postmodern inclined scholars, as noted by several scholars (e.g., Baer, 1997: 340; Albrechts, 2004: 745). However, it remains challenging to accurately pinpoint the negative connotation linked to comprehensive planning.

As mentioned, the concept of comprehensive planning has not been abandoned; in fact, it seems to be 'alive and well', as illustrated by the following observation by Stead and Meijers (2009: 317):

"The 'comprehensive integrated approach' to spatial planning, in which the coordination of public sector activity across different departments is a central feature, has been recognised as one of the main 'traditions' of spatial planning in Europe and can be found in planning systems in Austria, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and the Nordic countries."

While the context-specific and shifting understanding of comprehensive planning remains intriguing, the term itself has an appealing simplicity to it.

3.2.2 Applied to the South African scenario

As discussed, the definition of 'comprehensive planning' is elusive, and two or three divergent meanings could be distinguished. In the sense of comprehensive meaning to include a wide range of fields, the South African IDP is more 'comprehensive' than the SDF. SDFs generally do not appear to deal with the full range of services and issues of municipalities and, as such, cannot be described as comprehensive. However, as discussed in section 3.4.2, the SDF, slightly confusingly, is also supposed to align all sector policies and plans.

Adopting a more recent understanding of comprehensive planning, for example, the USA comprehensive plans, these generally include a spatial plan; see, for example, City of Jackson: Comprehensive Plan 2018-2038 (City of Jackson, 2018, online). These comprehensive plans, therefore, illustrate the concept of integrated planning in the sense of spatial planning and integrated planning being combined.

3.3 Strategic planning

3.3.1 Global conception

The third concept worth discussing is 'strategic planning', which is different from 'strategic spatial planning' (see section 3.5). Strategic planning developed and gained popularity in the corporate world in the USA in the 1960s (Minzberg, 1994: 1) and was soon applied to the public sector; see, for instance, Bryson's (1988) aptly titled article "A strategic planning process for public and non-profit organizations'.

Although the sequence and exact content might vary, the classic strategic planning process typically comprises several steps such as scanning the internal and external environment for strengths and weaknesses, opportunities and threats (a so-called SWOT analysis); setting a vision; formulating goals and objectives; defining strategies; defining implementation projects, as well as monitoring and evaluation.

Although supporting strategic planning in general, Mintzberg, referring to the corporate environment, argued that it became too formulaic, and the emphasis shifted to strategic 'programming' rather than strategic thinking. The latter requires intuition and creativity, which is dependent on individual leadership rather than work produced by technical teams (Mintzberg, 1994: 2). Mintzberg (1994: 3) also questioned the role and relevance of projections and predictions:

"According to the premises of strategic planning, the world is supposed to hold still while a plan is being developed and then stay on the predicted course while that plan is being implemented."

Albrechts (2004: 746)14 similarly emphasised the responsiveness required from planning: "[S]trategic planning anticipates new tendencies, discontinuities, and surprises; it concentrates on openings and ways of taking advantage of new opportunities." Albrechts (2004: 750) also noted: "...over time the strategic planning process must stay abreast of changes in order to make the best decisions it can at any given point." Faludi (2000: 303) similarly emphasised the 'in-the-moment' nature of strategic planning, stating that it is a continuous process, and its progress is reflected in the minutes of the last meeting. For him, the purpose of strategic planning is decisions rather than documents. Insights gained from the planning process are, therefore, generally more important than the plan itself.

3.3.2 Applied to the South African scenario

According to the Municipal System Act, the IDP is "a single, inclusive and strategic plan" (section 25(1)) and "is the principal strategic planning instrument that guides and informs all planning and development" (section 35(1)(a)).15 Furthermore, the standard steps of strategic planning, as it emanated from the corporate world, are affirmed in the South African IDP guidelines, for instance the GIZ-assisted IDP Guide Packs (2001). Strategic planning in the IDP is thus both an objective and a methodology.

The first interpretive question might be how 'strategic' recent versions of IDPs really are? Are the IDP documents generally underpinned by credible strategic planning processes undertaken by the municipal leadership or do the documents rather represent the desktop collations of inputs from different departments? These are open questions for further reflection and/or research.

A related question underlying many statements regarding strategic planning (and planning, in general) is whether a plan that remains fairly static for approximately five years (even if small changes are made annually) can be conducive to the intrinsic idea of strategic planning. Is the municipal environment not too volatile to have plans that are as fixed as the IDP and SDF?

3.4 Integrated planning

3.4.1 Global conception

The fourth concept to be investigated is 'integrated planning'. In his seminal work on integrated policy,16 Underdal (1980: 159) provided a fairly simple understanding of integration: "to integrate means to unify, to put parts together in a whole. Integrated policy, then, means a policy where the constituent elements are brought together and made subjects to a single unified conception."

Stead and Meijers (2009: 6) offered the following understanding of (policy) integration:

"...policy integration refers to the management of cross-cutting issues that transcend the boundaries of established policy fields and that do not correspond to the institutional responsibilities of individual government departments."

Furthermore, integration is normally understood as addressing horizontal integration (across departments within a single organisation) and vertical integration (between scales or spheres of government and across organisations) (Holden, 2012: 2; Henderson & Lowe, 2015: 5; Stead & Meijers, 2009: 318). Henderson and Lowe (2015: 1) also emphasised the 'collaborative' component of integrated planning, stating: "From Perth to San Francisco, 'integrated planning' is used to describe spatial planning efforts that emphasise collaboration to achieve policy ends."

Holden (2012: 2) recognised the limitations of integration: "It is one thing to admit the failures of 'solitudes, silos and stovepipes' in local government planning, quite another to chart a pragmatic path forward for integration."

It should be noted that integrated or joined-up government internationally focused, among others, on the realisation that local government is constrained in its abilities and requires more active engagement with, and mobilisation of the private sector. The concept of private public partnerships (PPPs) also gained prominence during this period.

3.4.2 Applied to the South African scenario

Within the South African context, the Intergovernmental Forum for Effective Planning and Development (FEPD) formulated an often-cited definition of 'integrated development planning' (note the addition of 'development'), dating from 1995, while assisting in conceptualising the IDP:

"A participatory planning process aimed at integrating sectoral strategies, in order to support the optimal allocation of scarce resources between sectors and geographical areas and across the population, in a manner that promotes sustainable growth, equity and the empowerment of the poor and marginalised." (RSA, 2001: 12)

Harrison (2006: 188) observed that, in the late 1990s in South Africa, policies from a "huge, interlinked global policy network" influenced integrated planning initiatives. The idea of 'joined-up government', central to the New Public Management (NPM) movement, featured prominently in these ideas. In terms of public private partnerships, it could be observed that there is much room for improvement in South African municipalities, and clearly the level of delivery in many instances points to the need for private sector involvement (Alford & Hughes, 2008: 130).

As mentioned, according to SPLUMA, the SDF also has strong objectives in terms of 'integration' and highlights the need for SDFs to integrate and align sector policies and plans.17 Similarly to the IDP, integration, alignment, and coordination should be core objectives of all SDFs. It perhaps begs the question: If the SDF's role is to integrate, what is the role of the IDP? However, a clarification might be that SPLUMA focuses on these objectives from a spatial perspective.

3.5 Strategic spatial planning

3.5.1 Global conception

Not to be confused with 'strategic planning', 'strategic spatial planning' (SSP) is a fifth concept to be explored, partly due to the abundance of fairly recent literature on the subject. An important point to note from the referenced literature is that 'strategic spatial planning' is used interchangeably with 'spatial planning'.18

SSP has gained increasing popularity in Europe over the past two decades. Hersperger et al. (2019: 96), for instance, noted: "Strategic spatial planning is increasingly practised throughout the world to develop a coordinated vision for guiding the medium- to long-term development of urban regions."

One of the most ardent proponents of SSP has probably been Louis Albrechts, although the work from John Friedman, Patsy Healey, and many others should also be recognised. Healey (2004: 46) defined SSP as:

"'strategic spatial planning' refers to self-conscious collective efforts to re-imagine a city, urban region or wider territory and to translate the result into priorities for area investment, conservation measures, strategic infrastructure investments and principles of land use regulation."

In terms of the 'spatial' in SSP, Albrechts (2004: 748) explained the concept as follows:

"The term 'spatial' brings into focus the 'where of things', whether static or dynamic; the creation and management of special 'places' and sites; the interrelations between different activities in an area, and significant intersections and nodes within an area which are physically collocated."

3.5.2 Applied to the South African scenario

As mentioned, the definition of strategic spatial planning (SSP) is very broad but generally appears to be fairly close to what is reflected, or at least intended, in South African SDFs (rather than IDPs). SSP appears to be a strategic process with a spatial focus. As such, SSP, as described, does not refer to a separate strategic planning process; the strategic process is part and parcel of the SSP process.

In her definition, Watson (2009:168) was aligned to the global definition of SSP in the South African context: "Strategic spatial plans are 'directive' long range plans, which consist of frameworks and principles and broad spatial ideas rather than detailed spatial plans". The issue of detail, as presented in section 3.1.2, appears to be relevant to South Africa, as SDFs sometimes appear to lack the level of detail (and 'blueprint' qualities?) required by, for example, transport and infrastructure planners.

3.6 Community planning and other postmodern planning concepts

3.6.1 Global conception

As part of the postmodern movement in planning theory, a range of alternative terms, approaches or paradigms gained traction. Advocacy planning, associated with Davidoff (1965: 285) was an early example. One of the shifts was the increased focus on process and creating

ways of ensuring that the voices of all sectors of the community are properly heard. Many of the postmodern scholars also highlighted the role of uneven power relations.

The adoption of new instruments such as community plans (or community development plans, community strategic plans, or neighbourhood development plans) illustrates the acceptance of the importance of social issues and community ownership.19

3.6.2 Applied to the South African scenario

The IDP has an element of a community plan in both its conception and practice; the latter as capturing community 'wish-lists' through a ward-based round of engagements that appears to be an enduring component of the IDP process in South African municipalities. The IDP process also covers, to some extent, the ideal of communicating with the community.

In terms of the SDF, it could be argued that the process typically includes public participation; but it is generally less community based and more stakeholder based. Again, the SDF (and IDP) is beset by the difficulties posed by large and expansive municipalities, rendering deep and ongoing engagement with all communities extremely challenging.

4. SYNTHESIS

Analysing global conceptions of forward planning and applying these to the South African IDP and SDF resulted in several observations, albeit explorative. In terms of the broader research topic, it is hoped that these could assist in clarifying an agenda and contributing to building a suitable platform.

4.1 Basic definition and objectives of planning

Based on the literature studied, the following can be presented as a list of the main components of forward planning, as it pertains to the municipal environment, which could be helpful for unpacking, in simple language, the essential characteristics of municipal forward planning.20 These features may, of course, vary between planning endeavours according to the priority attached to each of the objectives.

• planning as a vision:

ο an aspirational vision

ο a blueprint

• planning as integration, alignment, and allocating resources:

ο horizontal (within the organisation);

ο vertical (between sectors and spheres of government);

ο prioritisation in terms of resource allocation;

• planning as collaboration between stakeholders from different professions, institutions, and interest groups;

• planning as being responsive; constantly identifying risks and opportunities, and

• planning as community oriented and addressing societal issues.

4.2 Global terminology related to municipal forward planning

First, it can be noted that the terminology and meanings reflect how theory has evolved over time. In the process, meanings became entangled with theoretical debates, requiring a process of 'demystification', as argued in section 1.3. As expected, there was a great deal of overlap between the terms, but simultaneously several deeper meanings, insights, and nuances that potentially enrich the endeavour of planning, were observed. Furthermore, several seemingly unresolved tensions appear to be evident in these definitions; for example,, modernist/positivist as opposed to postmodern community-focused planning approaches.

Globally, forward planning in municipalities could perhaps benefit from a common 'dictionary'. However, it is argued that it is important that the lexicon should be straightforward and accessible to non-planners, among others, because, in many municipalities, much of the municipal planning (including the IDP and SDF) is driven by non-planners.21

4.3 Applied to the South African system and instruments

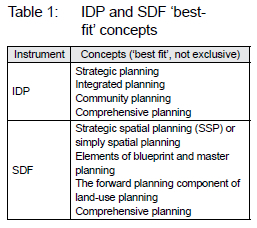

Based on the study of the terminology, the 'best-fit' associations of the IDP and SDF in relation to these terms could be summarised as in Table 1. It is, of course, not a simple categorisation and there will be a great deal of overlap; but for the purpose of advancing the discussion, the table may be helpful. It should be noted that 'comprehensive planning' fits in under both, depending on the interpretation employed.

4.4 Is it essential to have two instruments?

While the IDP and SDF, when viewed together, are to a large degree related to all the global terms investigated, the question remains as to whether having two separate instruments is beneficial or detrimental to the system as a whole.

It should be noted again (see also sections 1.1 and 2.2) that many would argue that, strictly speaking, South Africa only has one instrument, namely the IDP and that the SDF is merely a subcomponent or chapter of the IDP. Others, however, would question this interpretation, and argue that the SDF is an instrument in its own right. As mentioned earlieer, for the purpose of this article, the author assumes that, irrespective of what the exact correct legal position might be, IDPs and SDFs are mostly 'practised' as separate instruments.

The ongoing 'dualistic' implementation of the IDP and SDF could be viewed either as a positive phenomenon, or as a contradiction causing a degree of fragmentation. If the motivation for the dualism is to ensure that the 'spatial aspects' are addressed specifically, the question remains as to whether it is healthy and desirable to separate the 'spatial' from 'other' mainstream strategic and integration concerns.

4.5 Scale and time horizon

Two other themes have transpired: one relating to 'scale' and the other to 'time'. In terms of scale, it has been noted (see section 3.1.2) that the huge municipal areas demarcated in 2000 led to municipalities comprising large areas, including several towns and communities. This leads to plans lacking detail, unless being addressed in a type of 'package-of-plans' approach. Municipalities have been struggling with this ever since. In many IDPs, a ward-based approach is followed, but wards do not always coincide with geographic entities.

In terms of time, it appears22 that the current instruments need an improved and clearer approach to time horizons. The SDF is generally regarded as the longer term instrument, while the IDP is regarded as the medium-term instrument. However, newly elected councils have the authority to develop a new IDP that would potentially trump the longer term SDF.23 Furthermore, in an apparent effort to align the SDF with the IDP, SPLUMA stresses the 5-year horizon of an SDF (see section 2.2), but one could then argue that, except for a few general statements, the longer term planning ideal is now underemphasised.

4.6 The role of planning and planners

As indicated in section 3, forward planning is inherently a political process, as it revolves around the allocation of resources. In general, it is hypothesised that, for planners to increase their relevance in municipalities, they need to have more empathy24 for understanding the sentiments and requirements of planning from the perspective of non-planners, especially councillors and senior managers.

While the importance of planning is uncontested, the role of planners in South Africa is somewhat less obvious and more complex. Planners align themselves with a key role in preparing SDFs but are far less active in the IDP space. This, in itself, is a topic that warrants in-depth research, and certain questions emerge. For example, Can good planning in municipalities be done without the involvement of planners? Can planners be involved in the municipal space without involving themselves with the development of IDPs?

5. CONCLUSION

The original motivation leading to this article was the desire to better understand the developmental and planning role of the IDP. It was soon realised that it cannot be done without simultaneously considering the SDF. This led to the overarching objective of this article: to investigate the two instruments as two components or 'contributors' in respect of a single system, i.e. the system of forward planning in South African municipalities.

The interesting question that then presented itself was whether employing two instruments is really required and/or optimal. Acheampong and Ibrahim, in studying the Ghanaian experience, noted (as mentioned in section 1.2) that it represents two systems with the spatial being split from the rest, and thus impeding policy alignment. Perhaps the way in which municipal forward planning in South Africa is practised displays a similar issue. The question alluded to by Harrison in 2006 (see section 2.4), whether the IDP contributed to the burden of municipalities, and his remark that the 'jury is still out' (Harrison, 2006: 204) are still perhaps relevant at present. However, it is the author's opinion that, under the current circumstances, it is not about either the IDP or the SDF or defending any instrument, but rather about a fresh exploration of a strategic, comprehensive, integrated, and practicable approach. The study of global terminology and modes of planning, as undertaken in this article, can be regarded as a logical and, it is hoped, valuable first step in the context of such a venture.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author wishes to thank the peer reviewers as well as the colleagues who assisted generously with suggestions and editing, particularly Richard Jordan.

DISCLAIMER

All views expressed, unless referenced, are those of the author in his personal capacity.

REFERENCES

ACHEAMPONG, R.A. & IBRAHIM, A. 2016. One nation, two planning systems? Spatial planning and multilevel policy integration in Ghana: Mechanisms, challenges and the way forward. Urban Forum, 27, pp. 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-015-9269-1 [ Links ]

ALBRECHTS, L. 2004. Strategic (spatial) planning re-examined. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 31(5), pp. 743-758. https://doi.org/10.1068/b3065 [ Links ]

ALEXANDER, E.R. 1994. The non-Euclidean mode of planning: What is it to be? Journal of the American Planning Association, 60(3), pp. 372-376. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369408975594 [ Links ]

ALFORD, J. & HUGHES, O. 2008. Public value pragmatism as the next phase of public management. The American Review of Public Sdministration, 38(2), pp.130-148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074008314203 [ Links ]

ALTSHULER, A. 1965. The city planning process: A political analysis. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

BAER, W.C. 1997. General plan evaluation criteria: An approach to making better plans. Journal of the American Planning Association, 63(3), pp. 329-344. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369708975926 [ Links ]

BRYSON, J.M. 1988. A strategic planning process for public and non-profit organizations. Long Range Planning, 21(1), pp. 73-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-6301(88)90061-1 [ Links ]

CITY OF JACKSON. 2018. City of Jackson (Georgia) Comprehensive Plan 2018-2038. [Online]. Available at: <https://dca.ga.gov/sites/default/flles/jackson_comprehensive_plan_2018-2038.pdf> [Accessed: 30 November 2021]. [ Links ]

COETZEE, J. 2010. Not another 'night at the museum': 'Moving on' - from 'developmental' local government to 'developmental local state.' Town and Regional Planning, 56, pp. 18-27. [ Links ]

COETZEE, J. 2012. The transformation of municipal development planning in South Africa (post-1994): Impressions and impasse. Town and Regional Planning, 61, pp. 10-20. [ Links ]

DAVIDOFF, P. 1965. Advocacy and pluralism in planning. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 31(4), pp. 277-296. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366508978187 [ Links ]

DE VISSER, J. 2009. Developmental local government in South Africa: Institutional fault lines. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance (CJLG), Issue 2, January 2009, pp. 7-25. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i2.1005 [ Links ]

DU PLESSIS, D.J. 2019. The impact of spatial planning on the structure of South African cities since 1994. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

FALUDI, A. 2000. The performance of spatial planning. Planning Practice and Research, 15(4), pp. 299-318. https://doi.org/10.1080/713691907 [ Links ]

FRIEDMANN, J. 1993. Toward a non-Euclidean mode of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 59(4), pp. 482-485. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369308975902 [ Links ]

HARRISON, P. 2006. Integrated development plans and third way politics. In: Pillay, U. (Ed.). Democracy and delivery: Urban policy in South Africa, Pretoria: HSRC press, pp. 186-207. [ Links ]

HEALEY, P. 2004. The treatment of space and place in the new strategic spatial planning in Europe. In: Müller, B. (Ed.). Steuerung und Planung im Wandel. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer Science+Business Media, pp. 297-329. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-80583-6_17 [ Links ]

HENDERSON, H. & LOWE, M. 2015. Conceptualising 'integration' in policy and practice: A case study of integrated planning in Melbourne. In: Burton, P. (Ed.). Proceedings of the State of Australian Cities Conference, 1-9 December, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia: Urban Research Program at Griffith University, pp. 1-13. [ Links ]

HERSPERGER, A.M., GRÄDINARU, S., OLIVEIRA, E., PAGLIARIN, S. & PALKA, G. 2019. Understanding strategic spatial planning to effectively guide development of urban regions. Cities, 94, pp. 96-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.05.032 [ Links ]

HOLDEN, M. 2012. Is integrated planning any more than the sum of its parts? Considerations for planning sustainable cities. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 32(3), pp. 305-318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X12449483 [ Links ]

LORD, A. 2014. Towards a non-theoretical understanding of planning. Planning Theory, 13(1), pp.26-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095213477642 [ Links ]

MABIN, A. 2002. Local government in the emerging national planning context. In: Parnell, S., Pieterse, E., Swilling, M. & Wooldridge, D. (Eds). Democratising local government - The South African experience. Cape Town: UCT Press, pp. 40-56. [ Links ]

MINTZBERG, H. 1994. The fall and rise of strategic planning. Harvard Business Review, 72(1), pp.107-114. [ Links ]

NADIN, V., FERNANDEZ MALDONADO, A.M., ZONNEVELD, W., STEAD, D., DAJBROWSKI, M., PISKOREK, K., SARKAR, A., SCHMITT, P., SMAS, L., COTELLA, G. & JANIN RIVOLIN, U. 2018. COMPASS - Comparative Analysis of Territorial Governance and Spatial Planning Systems in Europe: Applied research 2016-2018. [ Links ]

NSW [NEW SOUTH WALES] GOVERNMENT, 2012. Integrated planning and reporting guidelines for local government in NSW. Sydney: Division of Local Government. [ Links ]

PARNELL, S. & PIETERSE, E. 2002. Developmental local government. In: Parnell, S., Pieterse, E., Swilling, M. & Wooldridge, D. (Eds). Democratising local government: The South African experiment. Landsdowne: UCT Press, pp. 79-91. [ Links ]

PERSSON, C. 2020. Perform or conform? Looking for the strategic in municipal spatial planning in Sweden. European Planning Studies, 28(6), pp. 183-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1614150 [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 1996. Local Government Transitional Arrangements Act (LGTA) Second Amendment Act, Act No. 97 of 1996. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 1998. The White Paper on Local Government. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2000. The Local Government Municipal Systems Act, Act No. 32 of 2000. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2001. IDP Guide Packs I-VII. Department of Provincial and Local Government, produced with the assistance of GIZ, Publisher: DPLG. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2012. National Development Plan 2030. Pretoria: The Presidency. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2013. Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act, Act No. 16 of 2013. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2016. Integrated Urban Development Framework. Pretoria: Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2020. National Spatial Development Framework. Pretoria: Department of Rural Development and Land Reform. [ Links ]

STEAD, D. & MEIJERS, E. 2009. Spatial planning and policy integration: Concepts, facilitators and inhibitors. Planning Theory & Practice, 10(3), pp. 317-332. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350903229752 [ Links ]

TODES, A. 2011. Reinventing planning: Critical reflections. Urban Forum, 22(2), pp. 115-133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-011-9109-x [ Links ]

TODES, A., KARAM, A., KLUG, N. & MALAZA, N. 2010. Beyond master planning? New approaches to spatial planning in Ekurhuleni, South Africa. Habitat International 34(4), pp. 414-420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.11.012 [ Links ]

UNDERDAL, A. 1980. Integrated marine policy: What? Why? How? Marine Policy, 4(3), pp.159-169. https://doi.org/10.1016/0308-597X(80)90051-2 [ Links ]

VAN DER BERG, A. 2019. Municipal planning law and policy for sustainable cities in South Africa. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Tilburg University, Tilburg. [ Links ]

WALES NATIONAL ASSEMBLY. 2016. Research paper: Comparison of the planning systems in the four UK countries. Cardiff Bay: Research Service for the National Assembly for Wales. [ Links ]

WATSON, V. 2009. 'The planned city sweeps the poor away...': Urban planning and 21st century urbanisation. Progress in Planning, 72(3), pp. 151-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2009.06.002 [ Links ]

WILDAVSKY, A.B. 1973. If planning is everything, maybe it's nothing. Policy Sciences, 4(2), pp. 127-153. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405729 [ Links ]

WREN, D.A. & BEDEIAN, A.G. 2009. The evolution of management thought. London: John Wiley and Sons. [ Links ]

Received: January 2022

Peer reviewed and revised: March 2022

Published: June 2022

* The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

1 In the Local Government Transition Second Amendment Act (Act No. 97 of 1996).

2 The Local Government: Municipal Planning and Performance Management Regulations, 2001, Notice 1429, 2001.

3 In the original conceptions of the IDP, this task was appropriated to land development objectives (LDOs) (Mabin, 2002: 50), which were to be part and parcel of an IDP. LDOs were embedded in the Development Facilitation Act (the DFA), which was retracted when SPLUMA was adopted.

4 The acronym 'MSDF' (Municipal Spatial Development Framework) came into use after the adoption of SPLUMA, as SPLUMA also included national and provincial SDFs.

5 Although the 10-20-year term is a general perspective, some important clauses of SPLUMA appear to prioritise the 5-year term, for example section 21(b) "[A municipal SDF should]...include a written and spatial representation of a five-year spatial development plan. and 21(e): .. , include population growth estimates for the next five years."

6 As mentioned elsewhere, the preparation of the SDF is in practice seldom part of, or even synchronised with the preparation of the IDP.

7 As per clause 2(4)(e) of the 2001 MSA regulations (The Local Government: Municipal Planning and Performance Management Regulations, 2001).

8 As per section 21(n) of SPLUMA.

9 There is probably a debate whether these two frameworks are intended to be exactly the same; some would argue that they are not.

10 Many South African municipalities do not employ town planners, and, if they do, their work is often focused on land-use management as opposed to integrated and strategic planning or management.

11 'Planners' could refer to any type of planner, for instance when Mintzberg (1994) referred to planners, he referred to management and financial planners who are active in the corporate business world.

12 The team cited is South African but captured the international literature in a very clear and useful manner and is, therefore, referenced in this context.

13 Author's observation. This is especially evident when a municipality comprises many towns and the budget is limited.

14 In this statement, Albrechts cited Granados Cabezas (1995).

15 Italics added by the current author.

16 Underdal's work actually focused on integrated 'marine' policy, but his concepts found universal resonance.

17 SPLUMA: Section 12(5), section 12(1)(c) and section 21(m).

18 For instance, the title of Faludi's paper refers to 'spatial planning' but the paper starts by pronouncing that it is about 'strategic spatial planning'. As such, it appears to be synonymous. Furthermore, the word 'strategic' is often omitted, especially in the United Kingdom.

19 Examples are from the United Kingdom as well as from Australia (Wales National Assembly, 2016; NSW Government, 2012)

20 It is recognised that it can be regarded as ambitious to try to highlight features of planning in this way, but, it is hoped, valuable in this context, nonetheless.

21 This observation is linked to an earlier one, namely that many municipalities in South Africa do not have qualified planners on their staff, and often where they do, the planners are predominantly engaged with land-use management. It can be assumed that this observation also holds true for many municipalities across Africa and the global South.

22 Author's view.

23 The principle as expounded and mandated in the Municipal Systems Act is that a newly elected council has vast scope to determine its own priorities for its term of office, which should, as soon as possible after the election, be reflected in a new 5-year IDP. The new council then has, of course, the power to amend its SDF to reflect any new position.

24 Empathy is a key component within the concept of 'design thinking'.