Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Town and Regional Planning

On-line version ISSN 2415-0495

Print version ISSN 1012-280X

Town reg. plan. (Online) vol.79 Bloemfontein 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp79i1.6

ARTICLES

A critical Lefebvrian perspective on planning in relation to informal settlements in South Africa

'N kritiese lefebvriaanse perspektief op beplanning met betrekking tot infórmele nedersettings in Suid-Afrika

Thlahlobo ea maikutlo a lefebre mabapi le thero ea libaka e ikamahanyang le metse e as reroang (ea baipehi) Afrika Boroa

Marie Huchzermeyer

School of Architecture and Planning, University of the Witwatersrand, Private Bag 3, Wits 2050, Johannesburg, South Africa. Phone: +27-11-7177688, email: <marie.huchzermeyer@wits.ac.za>, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3209-5449

ABSTRACT

Informal settlements intersect with spatial planning when they are placed on a trajectory towards permanent upgrading. In South Africa, the law requires this intersection to be as non-disruptive as possible. However, this is difficult to secure, as the Slovo Park informal settlement case in Johannesburg exemplifies. This article demonstrates the conceptual relevance of Henri Lefebvre's writing on the right to the city and his closely associated theory on differential space for the informal settlement and planning question. The article notes that the planning theory discourse has engaged with what occurs outside of statutory planning. This skirts Lefebvre's radical critique of statutory planning and its direct implication for spontaneous urban spatial practice. Lefebvre's critique of planning is open-ended, providing pointers towards an alternative, namely transduction. The article shows the relevance of this for the transformation of planning and urban space in South Africa.

Keywords: Henri Lefebvre, informal settlements, in situ upgrading, planning, planning theory, right to the city, Slovo Park

OPSOMMING

Informele nedersettings kruis met ruimtelike beplanning wanneer hulle op 'n trajek na permanente opgradering geplaas word. In Suid-Afrika vereis die wet dat hierdie kruising so nie-ontwrigtend moontlik moet wees. Dit is egter moeilik om te verseker, soos die Slovo Park informele nedersettingsaak in Johannesburg wys. Hierdie artikel demonstreer die konseptuele relevansie van Henri Lefebvre se skrywe oor die reg op die stad en sy nou geassosieerde teorie oor differensiële ruimte vir die informele nedersettings- en beplanningsvraagstuk. Daar word opgemerk dat die beplanningsteorie-diskoers betrokke was by dit wat buite statutêre beplanning plaasvind. Dit ontwyk Lefebvre se radikale kritiek op statutêre beplanning en die direkte implikasie daarvan vir spontane stedelike ruimtelike praktyk. Lefebvre se kritiek op beplanning is oop, en verskaf aanwysings na 'n alternatiewe, naamlik transduksie. Die artikel wys die relevansie hiervan vir die transformasie van beplanning en stedelike ruimte in Suid-Afrika.

Sleutelwoorde: Beplanning, beplanningsteorie, Henri Lefebvre, informele nedersettings, in situ opgradering, reg tot die stad, Slovo Park

SA BONAHALENG

Kamano lipakeng tsa metse esa reroang le thero ea libaka e tiisoa ke ntlafatso ea maphomella. Naheng ea Afrika Boroa, molao o tlama hore kamano ena e be a se nang tsitiso ka hohle kamoo ho ka khonehang. Leha ho le joalo, ho thata ho netefatsa sena, joalo ka ha ho ile hoa iponahatsa ntlafatsong ea Slovo Park, Johannesburg. Sengoliloeng sena se bonts'a bohlokoa ba maikutlo a Henri Lefebvre mabapi le litokelo tsa batho litoropong 'moho le phapang ea libaka, ele ho ikamahanya le thero ea libaka le metse e sa reroang. Sengoliloeng se hlokomela hore mehopolo e amanang le thero ea litoropo e ikamahanya le se etsahalang kantle ho melao e amehang. Sena se akaretsa tlhaloso ea Lefebvre ea hore molao o susumetsa ntshetsopele ea litoropo e sa reroang le e seng molaong. Kaha tlhaloso ena ea Lefebvre e bulehile, e fana ka lintlha tse lebisang ho mokhoa o mong oa phetisetsano ea litharollo. Sengoliloeng sena se bontsa bohlokoa ba phetisetsano bakeng sa phetoho ea thero ea litoropo tsa Afrika Boroa.

Urban dwellers carry the urban with them, even if they do not bring the planning with them! (Lefebvre, 1968/1996: 158)

1. INTRODUCTION

South Africa's growing number of informal settlements exist in a complicated relationship with the statutory planning framework. At a national level, this framework has come to terms with the exclusionary nature of apartheid-era planning and the continuation of many aspects of this exclusion well into the second decade of democracy (Van Wyk & Oranje, 2014). Protracted planning reform ushered in the Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act 16 of 2013 (SPLUMA). This 'framework, national legislation' (Van Wyk, 2020: xiv) requires planning to respond to informal settlements through their recognition in city-level spatial plans and through flexibility and appropriateness in spatial land-use management systems that operate at the local level (SPLUMA, section 7(a)). Land use schemes need to introduce 'land use management and regulation' incrementally into informal settlements (SPLUMA, section 24(2)(c)). Almost a decade prior to the enactment of SPLUMA, a shift in housing or human settlement policy introduced the Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme (UISP), requiring minimal disruption to inhabitants' lives and relocation as a last resort (DoH, 2004; DoHS, 2009). SPLUMA's provisions for informal settlements mirror the spirit of the UISP. However, reviews of UISP implementation have found progress to be modest; they have identified lack of institutional support, effective budget allocation, capacity, political will, and unrealistic targets (Cirolia, Görgens, van Donk, Smit & Drimie, 2016; Misselhorn, 2017). In recent informal settlement upgrading deliberations at municipal, provincial and national levels, in which the author has participated as an academic expert, planning has emerged as an additional obstacle, despite the supportive clauses in SPLUMA. This article draws on theory and critical practice to reflect on planning in relation to informal settlements and their upgrading.

The article uses the term 'planning' for legally or statutorily defined rules and processes. Whereas 'planning theory' has largely tackled the intersection between planning and informality, by seeking to explain what happens outside and alongside statutory planning, this article attempts to respond to a call Harrison (2014) makes in a reflection on his own experience as a professional planner, for more pragmatic 'theory in planning'. This article acknowledges recent contributions in the South African planning discourse, in this journal in particular, developing 'theory in planning' in relation to South African informal settlements. Cilliers and Victor's (2018) study of basic service improvement in an informal settlement in North-West province recommends 'planning with' as opposed to 'planning for', suggesting that this could be incorporated into the mainstream of spatial planning. De Beer and Oranje (2019) build a critique of planning thought through the lens of progressive theorists and argue for recognition of communities making the city from below.

The enquiry in this article sets out to contribute to 'theory in planning', by exploring 20th-century French sociologist and philosopher Henri Lefebvre's urban writing as a conceptual basis from which to confront obstacles that planning presents in the implementation of statutory policy that requires sensitive in situ upgrading of informal settlements. To speak to the South African planning and urban policy discourse, the article uses the term 'informal settlement' rather than the more political term 'shack settlement', as employed by Pithouse (2009), or the term 'shantytown' chosen by the translators of Henri Lefebvre's writing. This article uses the official definition of informal settlements articulated by the National Upgrading Support Programme (NUSP [s.a.], cited in Huchzermeyer, Karam & Maina, 2014: 158) on its erstwhile website.1This definition forefronts the absence of 'official approval' and adds various dimensions of inadequacy in the standard of living, therefore excluding from its definition unauthorised developments of the well-to-do.

The research for this article forms part of a larger study that reflects on the author's engagement in deliberations that aim to unlock informal settlement upgrading. These deliberations are primarily with the City of Johannesburg and the National Upgrading Support Programme in the Department of Human Settlements. The author's participation in a task team for the upgrading of the Slovo Park informal settlement, south of Eldorado Park in Soweto, Johannesburg, has provided insights into obstacles for informal settlement upgrading in the City. These insights informed the pragmatic framing for the analysis of literature for this article. This has allowed the inductive research approach to incorporate an element of 'praxis of collaboration' (Rankin, 2012: 113), which Rankin (2012) defines as a reflexive relationship between theory and practice, where the practice involves transdisciplinary engagement. From this reflexive position, the author reviewed and analysed four interconnected bodies of published scholarship, basing this on a selection of key readings that stood out as moving the debate forward. These bodies of literature were, first, urban writings by Henri Lefebvre and published commentaries on this; secondly, South African planning literature that intersects with the informal settlement challenge; thirdly, South African informal settlement policy literature and, lastly, international planning theory literature that has sought to bring informality to the attention of planning scholarship.

This article starts by situating the disjuncture between the UISP and statutory planning within the context of the deliberations between the City of Johannesburg and the Slovo Park Community Development Forum (SPCDF) over the in situ upgrading of the Slovo Park informal settlement. It then steps back to review Henri Lefebvre's right to the city and the concepts he weaves into his arguments for this aspiration and right. From there, it examines how Lefebvre engaged with informal settlements in his thinking on the right to the city and in his theory of differential space, which resonates in the right to the city. The article compares this with rationales for in situ upgrading of informal settlements in the policy discourse, noting the absence of a radically critical position. The article then reviews the legal meaning of planning as it applies in South Africa, and reviews this in relation to informal settlements. The article contrasts this with the meaning that 'planning' and its near-synonym 'urbanism' have taken on in the Anglo-American planning theory discourse, as it began to grapple with urban space production outside of statutory regulations, for instance, through informal means. It then turns to Henri Lefebvre's radical critique of statutorily practised planning, showing its relevance for the question of informal settlements and how he uses this critique as an open-ended route to a more suitable planning approach, namely transduction. The article closes by discussing the relevance of a transductive approach to planning for informal settlements such as Slovo Park and, beyond this, to overcome spatial inequality and segregation. It suggests that a radical critique of planning, leading out of current interest in South Africa in literature on the right to the city, could steer towards the review and reform of local level spatial land-use planning.

2. SITUATING THE CONFLICT BETWEEN INFORMAL SETTLEMENT UPGRADING AND STATUTORY PLANNING IN THE CASE OF SLOVO PARK, JOHANNESBURG

Informal settlement upgrading places particular demands on both the process and the outcome of planning. In South Africa, these demands are articulated at national level and, to some extent, resolved in the way SPLUMA accommodates the requirements of the UISP. However, tension between the UISP and planning remains a challenge at the level of implementation by municipalities. This section demonstrates the paralysing, if not destructive, effects of this tension through the case of Slovo Park in the City of Johannesburg.

As a programme in the National Housing Code, the UISP forms part of human settlements law. It requires an in situ approach, wherever possible, building on existing layouts to minimise relocation and disruption (DoHS, 2009). To facilitate this, it exempts the layout design from conventional norms and standards and advises against uniform stand sizes, instead expecting individual plot sizes to 'emerge through a dialogue between local authorities and residents'; in other words, it calls for incremental, participatory layout planning (DoHS, 2009: 14). The UISP envisages '[n]ormal township establishment processes [to] be followed even though township layout could differ substantially from the norm' (DoHS, 2009: 34). Implementation of this approach requires support from municipal planning departments that handle the planning approval processes.

The City of Johannesburg's Urban Management and Development Planning directorate developed a 'Regularisation Programme' in 2007, without reference to the UISP at the time, and predating SPLUMA. The programme allowed for informal settlements to be incorporated into the City's zoning system and fast-track investment (Huchzermeyer, 2011; Urban LandMark & Cities Alliance, 2013; Maina, 2016). However, in its operationalisation, housing officials understood regularisation to only deal with informal settlements in the interim; the planning framework still appeared to them to require full compliance with planning norms and standards before permitting permanent infrastructure investments (Huchzermeyer, 2011). Unlike, for instance, the zoning scheme that the City of Cape Town adopted in 2015, which contains the category 'Single Residential Zoning 2: Incremental Housing (SR2)' (CoCT, 2015: 106), the land use scheme that City of Johannesburg adopted in 2018 does not include a special zone for informal settlements (CoJ, 2018). This omission occurred despite submissions at drafting stage pointing to provisions in SPLUMA that set out this approach (Huchzermeyer, 2017; SERI, 2017).

With the dominant perception that statutory planning cannot accommodate informal settlements other than on a temporary basis, the City's planning consultants presented the Slovo Park community with layouts that either replaced the entire settlement, taking no account of existing spatial arrangements, or involved wholesale relocation (SERI, 2020). Both types of lay-out would lead to destruction of the settlement. This has been a widespread approach across South Africa, with standardised plot sizes based on the assumption that development would be funded through the standardised housing subsidy rather than the alternative provided through the UISP (Cirolia et al., 2016). Cirolia et al. (2016) observe the path-dependency of the state's standardised housing delivery. The SPCDF, however, took its reading from the UISP and litigated against the City. Ruling in favour of the SPCDF, the Gauteng High Court in 2016 found that the City of Johannesburg acted unlawfully in not applying for funding under the UISP for the Slovo Park informal settlement (SERI, 2020). The judgment underlines the UISP's provisions, including the need to plan in a participatory manner that minimises disruption to people's lives (Melani and others versus City of Johannesburg and others (02752/2014) [2016] ZAGPJHC 55 (22 March 2016)).

In response to an order in the Melani judgment, the City prepared its first UISP funding application to the Gauteng Provincial Government in 2016. Without consulting the SPCDF or the Slovo Park community, the City compiled its UISP application consisting of existing plans to move Slovo Park to relocation sites with conventional standardised layouts (CoJ, 2016). Through oversight from the Court, the Gauteng Provincial Government rejected this application (SERI, 2020). In January 2017, in its efforts to develop a compliant UISP application in a participatory manner, the City convened a Task Team that included officials from the City's Housing Department and Group Legal and Contracts Department, the City's appointed planning consultants, and the SPCDF with its legal and technical/academic support team (SERI, 2020). Despite extensive deliberations on the UISP's requirements, by the end of 2017, the planning consultant submitted a conventional layout for planning approval that, once more, took no account of the existing informal layout and would require destruction of the entire settlement.

In 2018, the SPCDF and its support team succeeded in arguing for the withdrawal of the consultant's plan, which the planning bureaucracy had already approved (Huchzermeyer, 2018a). The withdrawal secured the City's undertaking to pursue an in situ layout. On this basis, the City, in collaboration with the Task Team, prepared a new UISP funding application for Slovo Park (CoJ, 2019) and submitted this to the Gauteng Provincial Government. However, changes in the UISP funding regime within Treasury and the national Department of Human Settlements cast uncertainty over the status of the application, which, at the time this article went to print in November 2021, had been approved only verbally. The lockdown measures necessitated by three waves of the COVID-19 pandemic brought the momentum of the Task Team deliberations to a standstill for several months in 2020 and 2021. However, at the recommendation of the SPCDF and its support team, the City's Housing Department began engaging the Development Planning Department about the position of informal settlements within the City's Land Use Scheme (Slovo Park Task Team, 2021). In March 2021, the Gauteng Provincial Government joined the Task Team. To fasttrack procurement, the Province undertook to handle the selection and appointment of a professional resource team, including planners, for the upgrading of several informal settlements in the City. By September 2021, the new consultants were about to be appointed, with an undertaking, at least for Slovo Park, that this team would adhere closely to the prescripts of the UISP and work closely with the Task Team (Slovo Park Task Team, 2021).

Throughout the Task Team meetings from 2016 to 2021, the Deputy Chairperson of the SPCDF expressed frustration at the efforts needed to move a monolithic edifice that seemed to block implementation in the spirit of the UISP and as underlined by the Melani judgment. The judgment represented a victory in the SPCDF's undertaking to prevent the destruction of a settlement that residents had created for themselves and managed through a sophisticated system of committees, but which needed permanent municipal infrastructure. Henri Lefebvre's right to the city, to which this article turns next, speaks to the collective aspirations of the Slovo Park community, as expressed through their representatives that make up the SPCDF.

3. CONCEPTUALISING THE RIGHT TO THE CITY

Divergent positions characterise an extended academic debate on Henri Lefebvre's right to the city. The title to a review article by Kipfer, Saberi and Wieditz (2012) refers to this literature as 'debates and controversies'. However, there is consensus in the wide-ranging right-to-the-city literature that this 'right' entails more than accessing a home in the city or urban areas (Fernandes, 2007; Marcuse, 2012; Purcell, 2014; Biagi, 2020). The involvement of inhabitants in the making and managing of neighbourhoods and cities as collective spaces is a key component of this aspiration, which is referred to as a 'right' (Harvey, 2008). As most of the above-cited commentators on Lefebvre's work argue, the word 'right' is used loosely in the phrase 'right to the city'. Nevertheless, the Global Platform for the Right to the City (GPR2C) along with a European movement for human rights in the city, which increasingly uses the phrase 'right to the city' (Zárate, 2018), have sought recognition by the United Nations of the need to acknowledge a spatial or territorial dimension of existing human rights (Zárate, 2018). The GPR2C (s.a.), which is strongly informed by the Latin American trajectory of this aspiration, has refined its definition over the past five years. Its website in 2021 refers to the right to the city as

the right of all inhabitants, present and future, permanent and temporary, to inhabit, use, occupy, produce, govern and enjoy just, inclusive, safe and sustainable cities, villages and human settlements, defined as commons essential to a full and decent life (GPR2C, s.a.: par. 1).

In its concern for future generations, this definition aligns with the Brazilian Statute of the City, Law no. 10 of July 10, 2001, which requires urban policy to 'guarantee the right to sustainable cities' (PÓLIS, 2002: 39, reproducing a translation of the complete City Statute). The GPR2C brings the Right to the City in conversation with human rights, noting that this is a collective right that brings a spatial or 'territorial dimension' to recognised human rights. It further builds its definition on three pillars: a 'symbolic dimension' that forefronts a diversity of socio-cultural values; a 'material' (and territorial) dimension, which forefronts 'spatially just resource distribution', and a 'political dimension', which forefronts ideas (for a different future, for example) (GPR2C, s.a.: par. 3).

Henri Lefebvre has inspired the Latin American thinking through his writing on the right to the city since the late 1960s. Lefebvre's political philosophy incorporated base democracy and self-management (as a strand of Marxism), which also informed Brazilian opposition politics of the Left during the dictatorship and during democratisation from the mid-1970s (Fernandes, 1995; 2007). However, not all of the dimensions of his right to the city have found their way into the position of the GPR2C, and indeed this would be difficult to do. At a conceptual level, Henri Lefebvre (1970/2003) understood the right to the city as open-ended, and Anglo-American scholars have, therefore, noted and argued for a plurality of interpretations (Kipfer et al., 2012; Purcell, 2014, cited in Huchzermeyer, 2018b). However, Lefebvre (1970/2003: 150) also made three concrete proposals, first, that the 'urban problematic' should move to the foreground of political life; secondly, that self-management in industry and urban life be expanded, connected and activate one another, and, thirdly, he proposed 'an enlarged, transformed [and] concretized contractual system of a "right to the city"'. Whether Lefebvre intended a legal right when terming this aspiration 'the right to the city' has been debated. Drawing inspiration from Fernandes (2007) and Purcell (2014), Huchzermeyer (2018b) reviews this debate and provides a reading of Lefebvre's work that forefronts his engagement with codified rights and argues that he did intend a legal right as a pathway to a future, in which the state would dwindle and rights would ultimately take a different form.

Lefebvre argues for the right to the city or town, alongside the right to difference. In this instance, it is worth noting Biagi's (2020: 210) explanation that, in French, a 'political-administrative' meaning is attached to cité (city), whereas ville (town) implies 'urban space in its material assertion', a point hitherto largely lost in translation in the Anglo-American literature on Lefebvre's work. This includes Huchzermeyer (2018b), which is prefaced by a quote in which Lefebvre argues for the right to 'town' in opposition to extreme exclusionary and segregatory measures such as those of the apartheid state, although he does not mention South Africa as such (Lefebvre, 1973/1976: 35). Lefebvre mainly invokes right to the 'city' as a right to appropriation, autonomous production of space and self-management in opposition to modern town planning and the monotonous, mono-functional, segregated urban environments it enabled the French state to roll out in overarching submission to the dictates of the modernising economy and industry (Lefebvre, 1968/1996; 1970/2003).

In this sense, the right to the city pushes back against what Lefebvre refers to as 'spatial domination', which is the over-determination of the urban spatial order, not only in its material sense, by the state and the market. Planning, at the service of the state, is implicated in this spatial domination.

In Lefebvre's understanding, human beings in their core yearn for a more meaningful urban habitat than was produced by modern town planning. He articulates this yearning as 'a cry and a demand' (Lefebvre, 1968/1969: 158), which Marcuse (2012: 30) explains as 'a cry out of necessity and a demand for something more'. This yearning is for an environment, which contains divergence and surprises, one in which use value overrides concerns for exchange value, one that inhabitants can co-determine creatively, and one that allows for benign forms of appropriation and that inhabitants collectively manage from below (Huchzermeyer, 2014; 2018b). In this sense, urban habitat would form a collective work of art, and the right to the city includes the right to this ever-changing oeuvre (Huchzermeyer, 2014). Lefebvre does not wish away the economy, but his right to the city involves a process of gradually elevating humanist dimensions above the economy and above the state that serves the economy. As mentioned earlier, Lefebvre aligns to the political aspiration of a gradually receding state, which gives way to management from below (Huchzermeyer, 2018b).

4. INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS WITHIN LEFEBVRE'S RIGHT TO THE CITY AND THEORY OF SPATIAL DIFFERENCE

In many ways, informal settlements articulate with Lefebvre's attributes of the right to the city. Lefebvre (1974/1991) expressed this after his visit to informal settlements, or, in his translator's words, 'shantytowns', in Latin America in the early 1970s. He understood shantytowns as displaying high levels of self-organisation, self-expression or creativity and appropriation, and he understood them as attempting to counter spatial domination (Lefebvre, 1974/1991). As reviewed and discussed in Huchzermeyer (2020), it was evident to Lefebvre that inhabitants of informal settlements lived out these spatial practices against all odds, including the political repression meted out by Latin American dictatorships at the time. The force behind this repression was such that it precluded any romanticisation of informal settlements (Huchzermeyer, 2020). Lefebvre understood the spatial practice in informal settlements as incorporating political conscientisation about a different future being possible, the 'impossible-possible' (Huchzermeyer, 2020, citing Lefebvre 1970/2003: 105). Though not citing Lefebvre directly, De Beer and Oranje (2019) similarly invoke the concept of 'hope'. It is this conscientisation that threatens the establishment and motivates efforts at erasure through spatial domination. The shantytowns themselves represent what Lefebvre (1974/1991: 372) terms 'produced difference', a space collectively produced from below and starkly different from the dominant urban spatial norm in which urban planning is implicated.

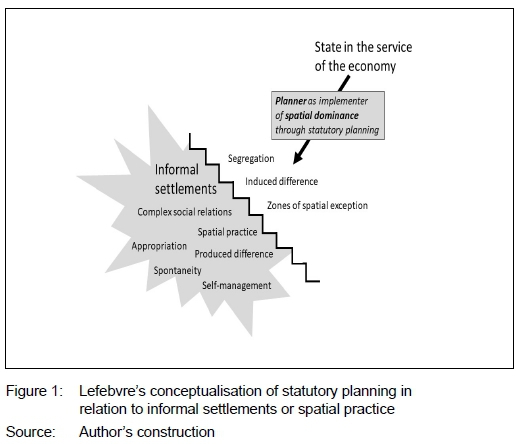

However, spatial domination, that is, the state and the economy's dominance through spatial (planning) norms, also entails spatial difference, namely intended difference, often created for the separation of different groups of people. Lefebvre (1974/1991: 372) termed this 'induced difference'. In urban space, induced difference strongly connects with segregation and 'totalitarian order', in contrast to the complexity of relations that criss-cross produced difference (Lefebvre, 1970/2003: 113, cited in Huchzermeyer, 2020: 472). Induced difference includes the imposed difference of minimised standards as they apply to the state's own zones of spatial exception. In the case of the state's response to informal settlements in South Africa, this induced difference may be created in response to an obligation to cater to the basic needs of the impoverished, in temporary responses to emergencies (temporary relocation areas), or wherever else the state deems a reduction of conventional standards justified. Informal settlements, created through the appropriation of urban space and governed from below, do not align with induced spatial difference. As captured in the diagram in Figure 1, attempts to have them upgraded stand the danger of losing their 'produced' difference with its complexity of social relations and being folded into 'induced' difference and thus spatial domination.

5. BRINGING UPGRADING OF INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS INTO THE CONVERSATION ABOUT THE RIGHT TO THE CITY

Advocates for in situ upgrading of informal settlements implicitly argue that produced spatial difference should be made permanent. They promote exceptions to, or new provisions within, planning and building regulations that would permit, on a temporary and longer term basis, the non-adherence to dominant, standardised urban spatial norms (Urban LandMark & Cities Alliance, 2013). However, in the policy discourse, justifications or motivations for informal settlement upgrading have not as yet invoked the dimensions that Lefebvre observed - produced difference, use value, practices of appropriation, self-organisation and self-management, and the collective work of art that has defied spatial dominance.

Rather than invoking Lefebvrian concepts, arguments by South African scholars and practitioners for in situ upgrading of informal settlements have focused on more palatable and equally important dimensions. These include livelihoods, capabilities, and forms of capital that the inhabitants of informal settlements hold, the urgent need for improvements, the economic logic of building on spatial investments already made or the disruption that relocation causes to fragile lives (Smit, 2006; Huchzermeyer, 2011; Cirolia et al., 2016). To some extent, the informal settlement upgrading policy in South Africa has incorporated these justifications. But, in avoiding questions of spatial domination, the informal settlement upgrading discourse in South Africa has, as yet, not critically interrogated the role of planning. Neither has it, as yet, asked, through the lens of informal settlements, what a Lefebvrian right to the city means for planning. In an exploratory way, this article seeks to begin this discussion through the ensuing sections.

6. PLANNING IN SOUTH AFRICA AS DEFINED BY LAW AND IN RELATION TO INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS

In South Africa, the meaning of 'planning' is set out in law and focuses on land, the control and regulation of its use and development, and, therefore, in broad terms, the management of land and land development (Van Wyk, 2020).

More specifically, planning 'is concerned with the determination, allocation and alteration of land uses' and, for this purpose also its subdivision (Van Wyk, 2020: 19). Cilliers and Victor (2018: 30) add that, in doing so, planning must resolve 'conflicting political and social demands on space, while protecting the earth's generative capacity'. The rationale for planning stems from the urbanisation process, which results in pressure on land; therefore, '[w]here there are people, there must be planning and there must be law' (or planning law) (Van Wyk, 2020: 19). In Van Wyk's (2020: 19) words, the Constitutional Court 'reached closure on the terminology debate' when pronouncing on this in relation to the affairs of local government in 2010, in its judgment in Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality vs Gauteng Development Tribunal and Others 2010 (6) SA 182 (CC). This important moment created pressure for the conclusion of post-apartheid planning reform and led to the enactment of SPLUMA in 2013. Prior to this, Harrison, Todes and Watson (2008) noted that, in the post-apartheid period, the role that planners had taken on had widened significantly, including, for instance, sustainable development of people, with various understandings of what this means. However, 'land-use planning and the design of human settlements ... remains a central and important part of what many planners do' (Harrison et al., 2008: 14). The judgment in 2010 and SPLUMA as of 2013 locate the final decision-making related to these primary activities of planners exclusively within local government.

Legally, the purpose of planning is defined as ensuring 'the health, safety and welfare of society [and] improving the quality of life and welfare of the community concerned' (Van Wyk, 2020: 12). In this sense, planning responds to fundamental human rights, namely those to 'an adequate standard of living' (which includes the right to housing) and to 'continuous improvement of living conditions' (UN,1976: Article 11). Realising these human rights is particularly important for those having to resort to life in an informal settlement, and planning has a role to play in this realisation. Implying somewhat of a grey area for planning in relation to informal settlements, Van Wyk (2020: 9) distinguishes between 'formal planning', namely that regulated by national planning legislation, and 'informal planning', this being 'regulated to some extent by housing legislation', which includes law contained in jurisprudence in South Africa.

The creation of informal settlements may be deemed 'informal' but is not entirely outside of the law, as certain legislative provisions secure rights to occupation and to improvement within this mode of existence. Roux (2004) points in particular to the legal status of 'unlawful occupier', which the Prevention of Illegal Eviction from and Unlawful Occupation of Land Act bestows on those living in an informal settlement, and which entails protections (in law) against eviction. The UISP reinforces this occupational right, as does the legal interpretation of the Gauteng High Court in 2016, which found it unlawful for a municipality not to apply this programme to its informal settlements (Huchzermeyer, 2016). Given the poor understanding of the exact implications of the rights that apply to those living in informal settlements, Huchzermeyer (2016: 196) locates informal settlements at an 'often unresolved nexus between planning and rights'.

7. HOW PLANNING THEORY DEFINES PLANNING IN RELATION TO THE EXISTENCE OF INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS

An international academic discourse has, over the past decade and a half, primarily in the Anglo-American journal Planning Theory, debated the meaning of planning in broad and non-legal terms in the context of inequality and informality. By identifying practices, including informality, that exist in parallel to statutory planning, and by referring to these as alternative forms of planning (Roy, 2011; Shatkin, 2011), the focus of this discourse turns away from statutory planning. Thus, the interaction between statutory planning and informal settlements remains a blind spot to planning theory. Roy (2011: 7) includes 'social struggle and mobilization for justice and opportunity' in her definition of planning. Miraftab (2009: 32) framed this as 'insurgent planning'. This recognises that space is made or shaped intentionally outside the statutory planning process (Watson, 2012). In conversation with Roy (2011), Shatkin (2011: 79-80) writes of 'alternative' or 'actually existing urbanisms' (informality being among them) when referring to these 'planning' activities outside of, or in parallel to statutory planning.

There is an overlap between the terms 'urbanism' and 'planning' in the planning theory discourse. Roy (2011: 8) refers to 'four interrelated processes' invoked in the theoretical use of the term 'urbanism'. One 'refers to the territorial circuit of capital', drawing on Lefebvre's spatial theory; the second 'indicates a set of social struggles over urban space', i.e., insurgency; the third is 'produced through the public apparatus that we may designate as planning' (Roy, 2011: 8). The fourth takes the territorial dimension in the first process to the global level (Roy, 2011). Putting this in simple terms, Allen, Lampis and Swilling (2016: 296) state that 'there are many urbanisms that produce the city', some of them 'untamed'. Informal settlements, or 'slum urbanism' as Allen et al. (2016: 300) label it, would be a relatively benign form of untamed urbanism when compared to the seemingly untameable space production resulting from the flows of global capital. However, Roy (2011: 13) also notes that she and others in the planning theory discourse understand planning as 'synonymous with the production of space' and not bounded by the state. This implies an overlap between their use of the term 'planning' and all four 'processes' she connects with urbanism.

The confusion between planning and urbanism is not aided by the fact that the French term for town planning is 'urbanisme', and Henri Lefebvre's translators for The urban revolution (1970/2003) and The production of space (1974/1991) use 'urbanism' to refer to town planning (in the 1968/1996 Right to the city, which is included in Writings on cities, the translator chose the term 'planning').

When Lefebvre's (1970/2003: 151) translators have him argue that there are three 'urbanisms', Lefebvre means three forms of planning, namely that carried out by humanists; that carried out by developers, with a market interest, and that of the state through its institutions and ideologies. In all three instances, the 'urbanists' would be professionally trained planners or planning experts. In this case, the contemporary planning theory discourse, therefore, does not align with Lefebvre's urbanisms in that particular text. However, a Lefebvrian term that overlaps with planning theorists' use of 'urbanism' is 'spatial practice'. Lefebvre (1974/1991: 38) understands this as something a society 'secretes', i.e., a society cannot help itself from 'slowly but surely' producing its space.

Lefebvre (1974/1991: 38) further clarifies that '[a] spatial practice must have a certain cohesiveness, but this does not imply that it is coherent' in the way that statutory planning attempts to be. Informal settlements, in Lefebvre's conceptualisation, are the result of spatial practice, or urban practice, as he terms it elsewhere (Lefebvre 1970/2003).

8. TOWARDS TRANSDUCTION -LEFEBVRE'S CRITIQUE OF PLANNING AND PRAGMATIC RECOMMENDATION

Lefebvre builds his critique of planning on how planning treats spatial or urban practice. His arguments, therefore, relate well to the situation in which planners are tasked with bringing informal settlements into the realm of the statutory planning framework and, for this purpose, develop spatial plans. Lefebvre (1970/2003: 153) observes that planning 'fails to examine [urban/ spatial] practice', and ignorant of it, planners 'replace or supplant' it. In doing so, they serve a larger 'logic and strategy' that they usually do not grasp (Lefebvre, 1970/2003: 153). Lefebvre (1970/2003: 154) explains this by arguing that they perform the role of 'organisers and administrators' or implementers in larger 'relationships of production', which, in turn, are controlled 'by an active group'. In this instance, Lefebvre implies planners' role in larger capitalist relations, in particular, their role in the transformation of land into commodities through its subdivision (Lefebvre, 1970/2003: 155). Already in the 1970s, a spatial turn was being identified in capitalism's expansive pursuit. Lefebvre (1970/2003: 157) ruthlessly points out that planners serve this purpose while under the illusion that they are 'caring for and healing a sick society, a pathological space'. Lefebvre (1970/2003: 159) further refers to planners' 'fetishism' with the satisfaction of needs and, linked to this, their assumption that these can be studied and classified by experts and then catered to. Thus planners, 'profoundly misjudging what is going on (and what is not) in their blind field, end up minutely organizing a repressive space' (Lefebvre, 1970/2003: 159). In this sense, planning 'accompanies the decline of the spontaneous city' (Lefebvre, 1970/2003: 160). This closes down inhabitants' consciousness of the impossible-possible discussed earlier. Thus, in its rigid and naïve approach, planning 'prevents thought from becoming a consideration of the possible, a reflection of the future' (Lefebvre, 1970/2003: 161).

Lefebvre does not leave us with only this scathing and incisive criticism of spatial planning. Lefebvre (1970/2003: 163) understands the 'radical critique of urban illusion' as necessary, as it 'opens the way to urban practice'. Lefebvre is optimistic that collective development (or improvement of living standards), not premised on growth, can result from urban practice. The necessary radical critique of planning is a critique of the state and its spatial politics. The 'urban illusion', an unnamed utopia of the state, blocks the road, making a possible future impossible (Lefebvre, 1970/2003: 163).

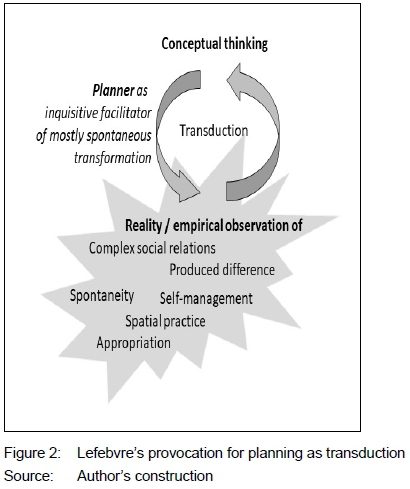

The direction Lefebvre charts for planning, which has direct relevance for in situ upgrading of informal settlements, is one in which reality and conceptual thought are in constant conversation, and boundaries are stretched so that 'we explore the possible-impossible, and that we do so through transduction' (Lefebvre, 1970/2003: 1962).

Transduction is a method of enquiry alongside induction and deduction. It is distinct from a design method of building models or carrying out simulations (Lefebvre, 1968/1996). It involves 'an incessant feedback between conceptual framework used and empirical observations' (Lefebvre, 1968/1996: 151).

Transduction 'gives shape to certain spontaneous mental operations of the planner ... It introduces rigour in invention and knowledge in utopia' (Lefebvre, 1968/1996: 151). This recommendation is directed at the process of planning. As with Lefebvre's ideas on the right to the city, and noting that the explanation of transduction, which this article reviews above, is in his Right to the city text, the recommendation on planning remains open-ended. With his critique of planning, Lefebvre seeks to chart a route towards a reform of what is at the core of planning, namely the governance of space. Connecting to the broader philosophies, which he links into his arguments for a right to the city, this shift in governance would be from spatial domination to self-management. As depicted in the diagram in Figure 2, the planner's role, therefore, needs to transform from implementer of a framework to enquirer and facilitator of spontaneity.

9. CONCLUSION

Informal settlements emerge out of necessity. In forming outside of statutory spatial regulation, they represent a process of collective place-making or spatial practice, which is not fully understood and valued. Henri Lefebvre's radical critique of statutory planning, which connects to the concepts he brings together under the right to the city, can be read to contain the recommendation that planners develop an inquisitiveness about settlement informality and spontaneity. This inquisitiveness needs to be ongoing, engaging both with the process of space creation and with the urban life it enables. In an open-ended way, it needs to reflect on, and at the same time, allow itself to be shaped, by spatial practice.

Applied to the Slovo Park case, the appointed planning consultant, alongside officials, would need to actively practise an inquisitiveness about Slovo Park, its inhabitants and their spatial activities, and from the understanding that this generates, help facilitate a transformation in the settlement that respects the spatial practice of the inhabitants. The UISP and SPLUMA would support this approach to planning. SPLUMA envisages informal settlements gradually or incrementally incorporated into land-use schemes, suggesting a facilitating rather than imposing role for planners. The UISP emphasises the participatory dimension of such facilitation. Implicitly, both statutes challenge planners to adopt transduction, a challenge that would similarly be directed at planning education and the bodies regulating the planning profession. However, Lefebvre can also be read to suggest that the spontaneous place-making process or spatial practice in informal settlements can gradually or incrementally and autonomously produce development or improvement of living standards. This would involve a more handsoff approach by planners than suggested in SPLUMA and the UISP. It challenges planning professionals to use their inquisitiveness to enrich, resource and gently steer spatial practice in a collectively determined process of improvement. However, not only planning regulations, but also financing mechanisms, procurement processes and dominant political leadership seem stacked against the validation of spatial practice and the produced difference that this would support.

A radical critique of current formal planning, foregrounding the spatial domination that planners enact, arises out of the spatial practice of informal settlements that stand to be destroyed by conventional planning. This critique is necessary for, and relevant to the larger challenge of overcoming the spatial domination that has held a grip on South Africa's segregated urban form. In this sense, this article provokes the questions: Can informal settlements' resistance to spatial domination trigger the much-needed search for more suitable approaches? Could such approaches speak back to the spatial planning and land-use management as applied to the formal city and human habitat at large, thereby breaking down persistent legacies of exclusion and charting a route to a different urban future? It is these provocations that a Lefebvrian right to the city lens offers at the intersection between planning and informal settlements.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to acknowledge the Slovo Park Task Team members, in particular Neil Klug's contributions as a reflexive planner.

REFERENCES

ALLEN, A., LAMPIS, A. & SWILLING, M. 2016. Untamed urbanisms: Enacting productive disruptions. In: Allen, A., Lampis, A. & Swilling, M. (Eds). Untamed urbanisms. London: Routledge, pp. 296-306. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315746692 [ Links ]

BIAGI, F. 2020. Henri Lefebvre's critical theory of space. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52367-1 [ Links ]

CILLIERS, J. & VICTOR, H. 2018. Considering spatial planning for the South African poor: An argument for 'planning with'. Town and Regional Planning, 72, pp. 29-42. https://doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp72i1.3 [ Links ]

CIROLIA, L, GÖRGENS, T., VAN DONK, M., SMIT, W. & DRIMIE, S. 2016. Upgrading informal settlements in South Africa: An introduction. In: Cirolia, L., Görgens, T., van Donk, M., Smit, W. & Drimie, S. (Eds). Upgrading informal settlements in South Africa: A partnership approach. Cape Town: UCT Press, pp. 3-25. [ Links ]

COCT (CITY OF CAPE TOWN). 2015. Municipal planning by-law, 2015. Cape Town: City of Cape Town. [ Links ]

COJ (CITY OF JOHANNESBURG). 2016. Application for funding under the Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme for the Slovo Park Informal Settlement located in Region G, City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality. Johannesburg: City of Johannesburg. [ Links ]

COJ (CITY OF JOHANNESBURG). 2018. City of Johannesburg Land Use Scheme, 2018. Johannesburg: City of Johannesburg. [ Links ]

COJ (CITY OF JOHANNESBURG). 2019. Interim application for funding under the Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme for the Slovo Park Informal Settlement located in Region G, City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality. Johannesburg: City of Johannesburg. [ Links ]

DE BEER, S. & ORANJE, M. 2019. City-making from below: A call for communities of resistance and reconstruction. Town and Regional Planning, 74, pp. 12-22. https://doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp74i1.2 [ Links ]

DOH (DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING). 2004. National Housing Programmes: Upgrading of Informal Settlements. Chapter 13. National housing code. Pretoria: Department of Housing. [ Links ]

DOHS (DEPARTMENT OF HUMAN SETTLEMENTS). 2009. Incremental interventions: Upgrading informal settlements. Volume 3, Part 3. National housing code. Pretoria: Department of Human Settlements. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, E. 1995. Law and urban change in Brazil. Aldershot: Avebury. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, E. 2007. Constructing the 'Right to the City' in Brazil. Social and Legal Studies, 16, pp. 201-218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663907076529 [ Links ]

GPR2C (GLOBAL PLATFORM FOR THE RIGHT TO THE CITY). s.a. What is the Right to the City? [Online]. Available at: https://www.right2city.org/the-right-to-the-city/ [Accessed: 24 June 2021]. [ Links ]

HARRISON, P. 2014. Making planning theory real. Planning Theory, 13(1), pp. 65-81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095213484144 [ Links ]

HARRISON, P., TODES, A. & WATSON, V. 2008. Planning and transformation: Learning from the post-apartheid experience. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203007983 [ Links ]

HARVEY, D. 2008. The right to the city. New Left Review, 53, pp. 34-40. [ Links ]

HUCHZERMEYER, M. 2011. Cities with 'slums': From informal settlement eradication to a right to the city in Africa. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

HUCHZERMEYER, M. 2014. Humanism, creativity and rights: Invoking Henri Lefebvre's right to the city in the tension presented by informal settlements in South Africa today. Transformation, 85, pp. 64-89. https://doi.org/10.1353/trn.2014.0026 [ Links ]

HUCHZERMEYER, M. 2016. Informal settlements at the intersection between urban planning and rights: Advances through judicialisation in the South African case. In: Deboulet, A. (Ed.), Rethinking precarious neighborhoods. Paris: Les editions de l'AFD, pp. 195-210. [Online]. Available at: https://www.afd.fr/en/ressources/rethinking-precarious-neighborhoods [Accessed: 24 June 2021]. [ Links ]

HUCHZERMEYER, M. 2017. City of Johannesburg Land Use Scheme comments. Submitted to the Executive Director, Development Planning, City of Johannesburg, 13 October. [ Links ]

HUCHZERMEYER, M. 2018a. Submission to Housing Department, City of Johannesburg, on behalf of Slovo Park Community Development Forum, based on main points made at a meeting dated 27 February 2018 and expanded in parts for greater clarity. Johannesburg: Centre for Urbanism and Built Environment Studies. [ Links ]

HUCHZERMEYER, M. 2018b. The legal meaning of Lefebvre's the right to the city: addressing the gap between global campaign and scholarly debate. Geojournal, 83(3), pp. 631-644. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-017-9790-y [ Links ]

HUCHZERMEYER, M. 2020. Informal settlements and shantytowns as differential space. In: Leary-Owhin, M. & McCarthy, J. (Eds). The Routledge handbook of Henri Lefebvre, the city and urban society. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 467-476. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315266589-49 [ Links ]

HUCHZERMEYER, M., KARAM, A. & MAINA, M. 2014. Informal settlements. In: Harrison, P., Gotz, G., Todes, A. & Wray, C. (Eds). Changing space changing city: Johannesburg after apartheid. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, pp. 154-175. https://doi.org/10.18772/22014107656.12 [ Links ]

KIPFER, S., SABERI, P. & WIEDITZ, T. 2012. Henri Lefebvre: Debates and controversies. Progress in Human Geography, 37(1), pp. 115-134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512446718 [ Links ]

LEFEBVRE, H. 1968/1996. Writings on cities. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

LEFEBVRE, H. 1970/2003. The urban revolution. London: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

LEFEBVRE, H. 1973/1976. The survival of capitalism: Reproduction of the relations of production. New York: St Martin's Press. [ Links ]

LEFEBVRE, H. 1974/1991. The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

MAINA, M. 2016. Adopting an incremental approach to informal settlement upgrading: The Johannesburg experience. In: Cirolia, L., Görgens, T., van Donk, M., Smit, W. & Drimie, S. (Eds). Upgrading informal settlements in South Africa: A partnership approach. Cape Town: UCT Press, pp. 115-129. [ Links ]

MARCUSE, P. 2012. Whose right(s) to what city? In: Brenner, N., Marcuse, P. & Mayer, M. (Eds). Cities for people, not for profit: Critical urban theory and the right to the city. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 24-41. [ Links ]

MIRAFTAB, F. 2009. Insurgent planning: Situating radical planning in the global south. Planning Theory, 8(1), pp. 32-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095208099297 [ Links ]

MISSELHORN, M. 2017. A programme management toolkit for metros: Preparing to scale up informal settlement upgrading in South African cities, a city-wide approach. Pretoria: Cities Support Programme, National Treasury. [ Links ]

NUSP (NATIONAL UPGRADING SUPPORT PROGRAMME). s.a. NUSP resource kit. [Online]. Available at: http://www.upgradingsupport.org/learn.html [Accessed: 1 September 2011]. [ Links ]

PITHOUSE, R. 2009. A progressive policy without progressive politics: Lessons from the failure to implement 'Breaking New Ground'. Town and Regional Planning, 54, pp. 1-14. [ Links ]

PÓLIS, 2002. The statute of the city: New tools for assuring the right to the city in Brazil. São Paulo: PÓLIS. [ Links ]

PURCELL, M. 2014. Possible worlds: Henri Lefebvre and the Right to the City. Journal of Urban Affairs, 36, pp. 141-154. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12034 [ Links ]

RANKIN, K. 2012. The praxis of planning and the contributions of critical development studies. In: Brenner, N., Marcuse, P. & Mayer, M. (Eds). Cities for people, not for profit: Critical urban theory and the right to the city. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 102-116. [ Links ]

ROUX, T. 2004. Background Report 2: Review of national legislation relevant to informal settlement upgrading. Study into supporting informal settlements. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand Research Team, for Department of Housing. [ Links ]

ROY, A. 2011. Urbanisms, worlding practices and the theory of planning. Planning Theory, 10(1), pp. 6-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095210386065 [ Links ]

SERI (SOCIO-ECONOMIC RIGHTS INSTITUTE OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2017. Submission on the City of Johannesburg Draft Land Use Scheme, 2017, October. [ Links ]

SERI (SOCIO-ECONOMIC RIGHTS INSTITUTE OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2020. Slovo Park: Some gains at last. 2nd edition. Community Practice Notes, Informal Settlement Series. Johannesburg: Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa. [Online]. Available at: https://www.serisa.org/images/SERI_Slovo_Park_practice_notes_2020_FINAL_WEB.pdf [Accessed: 24 June 2021]. [ Links ]

SHATKIN, G. 2011. Coping with actually existing urbanisms: The real politics of planning in the global era. Planning Theory, 10(1), pp. 79-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095210386068 [ Links ]

SLOVO PARK TASK TEAM. 2021. Item 1, page 6, draft minutes of the blended Slovo Park Task Team meeting 7 September, prepared by SocioEconomic Rights Institute of South Africa, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

SMIT, W. 2006. Understanding the complexities of informal settlements: Insights from Cape Town. In: Huchzermeyer, M. & Karam, A. (Eds). Confronting fragmentation: A perpetual challenge? Cape Town: UCT Press, pp. 103-125. [ Links ]

SPLUMA (SPATIAL PLANNING AND LAND USE MANAGEMENT ACT). 2013. Government Notice 559 in Government Gazette 36730, dated 5 August 2013. Commencement date: 1 July 2015 [Proc. No. 26, Gazette No. 38828, dated 27 May 2015]. [ Links ]

UN (UNITED NATIONS). 1976. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. New York: United Nations. [ Links ]

URBAN LANDMARK & CITIES ALLIANCE. 2013. Incrementally securing tenure: Promising practices in informal settlement upgrading in southern Africa. Pretoria: Urban LandMark. [ Links ]

VAN WYK, J. 2020. Planning law. 3rd edition. Cape Town: Juta & Co. [ Links ]

VAN WYK, J. & ORANJE, M. 2014. The post-1994 South African spatial planning system and Bill of Rights: A meaningful and mutually beneficial fit? Planning Theory, 13(4), pp. 349-369. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095213511966 [ Links ]

WATSON, V. 2012. Planning and the 'stubborn realities' of global south-east cities: Some merging ideas. Planning Theory, 12(1), pp. 81-100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095212446301 [ Links ]

ZARATE, L. 2018/2016. Forty years, isn't that nothing? The struggle for the inclusion of the right to the city in the global agenda. In: Pascual, I., Puertas, A. & Ramríez, G. (Eds). Habitat International Coalition and the Habitat Conferences 1976/2016. Barcelona: Habitat International Coalition, pp. 208-222. [Online]. Available at: http://hic-gs.org/news.php?pid=7420 [Accessed: 11 June 2019]. [ Links ]

Received: July 2021

Peer reviewed and revised: October 2021

Published: December 2021

* The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

1 The NUSP website was suspended in the course of 2020.