Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Town and Regional Planning

On-line version ISSN 2415-0495

Print version ISSN 1012-280X

Town reg. plan. (Online) vol.79 Bloemfontein 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp79i1.4

ARTICLES

Private-public partnership-produced urban space - An antithesis to 'the right to the city': A case study of Ruwa Town, Zimbabwe, from 1986-2021

Privaat-openbare vennootskap-geproduseerde stedelike ruimte - 'n antítese tot 'die reg op die stad': 'n gevallestudie van Ruwa Town, Zimbabwe, vanaf 1986-2021

Litoropo tse ahiloeng ka kopanelo ke mafapha a sechaba le a ikemetseng - maikutlo a fapaneng le a 'tokelo ea batho litoropong': boithuto ba ho tloha 1986-2021 toropong ea ruwa, Zimbabwe

Terence Muzorewa

Lecturer, Midlands State University, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Department of Development Studies. MSU number 1 Kwame Nkrumah Harare, Zimbabwe. Phone: 00263782123244, email: <terencemuzorewa@gmail.com>, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9103-7882

ABSTRACT

The article illustrates how the private-public-led urban development disenfranchised Ruwa residents' rights to control the planning of their local environments and affordable access to basic public amenities and services in their town. Ruwa was one of the first postcolonial towns in Zimbabwe to emerge and develop using the private-public approach. The study uses Henri Lefebvre's notion of the 'right to the city' as analytical lens. Lefebvre presents a vision for urban areas, in which residents manage urban space for themselves, beyond the control of private capital. In the same vein, this article argues that, although the private-public partnership approach was instrumental in the development of Ruwa Town, residents were left out of decision-making processes, yet they were the major stakeholders in the development process. Residents should take charge of development processes in their areas through grassroots participation. The study used mixed research tools which drew data from primary documents, statistical records, and interviews with various stakeholders of Ruwa Town development.

Keywords: Development, right, private-public partnership, town planning, Ruwa Town, city, urban space, Zimbabwe

OPSOMMING

Die artikel illustreer hoe die privaat-openbaar-geleide stedelike ontwikkeling Ruwa-inwoners se regte ontneem het om die beplanning van hul plaaslike omgewings en bekostigbare toegang tot basiese openbare geriewe en dienste in hul dorp te beheer. Ruwa was een van die eerste postkoloniale dorpe in Zimbabwe wat ontstaan en ontwikkel het deur die privaat-publieke benadering te gebruik. Die studie gebruik Henri Lefebvre se idee van die 'reg op die stad' as analitiese lens. Lefebvre bied 'n visie vir stedelike gebiede waarin inwoners stedelike ruimte vir hulself bestuur, buite die beheer van private kapitaal. In dieselfde trant argumenteer hierdie artikel dat, hoewel die privaat-openbare vennootskapsbenadering instrumenteel was in die ontwikkeling van Ruwa, inwoners uit besluitnemingsprosesse gelaat is, maar tog was hulle die belangrikste belanghebbendes in die ontwikkelingsproses. Inwoners moet beheer neem van ontwikkelingsprosesse in hul gebiede deur middel van voetsoolvlakdeelname. Die studie het gemengde navorsingsinstrumente gebruik wat data uit primêre dokumente, statistiese rekords en onderhoude met verskeie belanghebbendes van Ruwa-ontwikkeling getrek het.

Sleutelwoorde: Ontwikkeling, privaat-openbare vennootskap, Ruwa, stad, stadsbeplanning, stedelike ruimte, Zimbabwe

SA BONAHALENG

Sengoliloeng se bontsa kamoo nts'etsopele ea litoropo e etelletsoeng pele ke mafapha a sechaba le a ikemetseng e hantseng litokelo tsa baahi ba Ruwa ho laola moralo oa tikoloho le phihlello e theko e tlase ea lits'ebeletso tsa sechaba teropong ea bona.

Ruwa ke e 'ngoe ea litoropo tsa pele tse thonngoeng ka mor'a bokolone naheng ea Zimbabwe ka kopanelo ea mafapha a sechaba le a ikemetseng. Boithuto bona bo hlahlojoa ka tshebeliso ea maikutlo a Henri Lefebvre a 'tokelo ea batho litoropong'.

Lefebvre e fana ka ponelopele ea metse es litoropo, moo baahi ba laolang sebaka sa litoropo molemong oa tshebeliso ea bona, moo bohoebi bo senang tshutsumetso taolong ea metse le tsoelopele. Ka mokhoa o ts'oanang, sengoloa sena se tsitlella maikutlo a hore, le hoja mokhoa oa tsebelisano-'moho le sechaba o ile oa thusa haholo ntlafatsong ea toropo ea Ruwa, baahi ba ile ba koalloa ka ntle ha ho estoa liqeto, empa e ne e le bona ba nang le seabo se ka sehloohong mosebetsing oa ntlafatso. Boithuto bo susumetsa hore baahi ba lokela ho nka maemo a pele tshutsumetsong ea ntlafatso metseng le litoropong tsa bona. Kahona, tsoelopele e lokela ho qala tlase metseng e ea holimo pusong. Boithuto bona bo entse lipatlisiso tse neng li fumana lintlha ho tsoa litokomaneng tsa mantlha, lirekoto tsa lipalo-palo le lipuisano le ba amehang mafapheng a fapaneng a nts'etsopele toropong ea Ruwa.

1. INTRODUCTION

This article evaluates the 'right to the city' in private-public partnership (PPP)-led urban development, using the case study of Ruwa Town, located 23km from Harare, the capital city of Zimbabwe. Established in 1986, initially as a growth point, Ruwa was among the first postcolonial developed urban centres in Zimbabwe to adopt the PPP approach as a development strategy (Muzorewa, 2020: 197). To address the broad issues of public amenities development and funding for offsite infrastructure, the emerging town fostered a partnership with private land developer companies (PLDCs) in a bid to lure investment into an area that was originally a commercial farming hinterland (Muzorewa, 2020: 198). The PLDCs played a crucial role in developing urban infrastructure such as roads, sewerage and water systems, electricity facilities, health institution, education institution facilities, shopping malls, and housing facilities in the town such that, in 2008, Ruwa was given urban status by the Central Government in honour of its outstanding development. Although the PPP approach has been hailed as one of the best strategies to ensure urban development in postcolonial Zimbabwe, observations in Ruwa show that PPP-led development disfranchised the ordinary residents' 'right to the city' in various ways, as discussed in this article.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Public-private partnerships

Moszoro and Krzyzanowsk (2011: 3) examined broad PPPs and the theory underpinning them. They defined PPPs as "cooperation agreements between a public authority and the private sector to provide public service". A review of literature on PPPs has unveiled scholars such as Bovaird (2004), Skelcher (2005), Klijn and Teisman (2003), Hodge and Greve (2007), and Wettenhall (2010) who define PPPs as inter-organisational arrangements that combine resources such as skills and knowledge from a public sector organisation with a private sector organisation, in order to deliver societal goods. Although there are varying theoretical perspectives underpinning PPPs, scholars generally refer to PPP as a hybrid organisational arrangement that has characteristics of both private and public sectors.

Marxist and anti-neoliberal scholars have criticised PPPs for promoting for profit-oriented development. Miraftab (2004: 89) criticises PPPs and views them as the "Trojan horse of neo-liberal development". Other anti-neoliberal scholars such as Brenner and Theodore (2002), Mirowski (2013), Peck and Tickell (2002), as well as Jessop (2002) argue that neo-liberalism has imposed a pervasive market mentality in urban development. For them, the private sector in PPPs serves their own profit-seeking interest at the expense of residents whom they are supposed to serve. Although anti-liberal scholars have criticised PPPs, some liberal scholars such as Klein (2015) and Leigland (2018) argue that in PPPs, the private sector can outperform public sector-led development and service delivery. Similarly, Pinson and Journel (2016) argue that one of the merits of neo-liberalism is its ability to incorporate the private sector and the state in development. In Ruwa, the PPP consisted of a tripartite, comprising the Central Government, the Local Authority, and private land developers. PPPs were not adopted in Ruwa only, but have also been a development model for many urban areas in the region. Didier and Peyroux (2013) describe how neo-liberal urban development was adopted successfully in Cape Town and Johannesburg (South Africa) through the Business Improvement District strategy. This article, however, does not dwell on debating whether PPPs are the best model or not, but analyses the characteristics of urban space they produce.

Not only has the private sector in PPPs been criticised for alienating residents from shaping the urban space, but the public sector has also been viewed as an accomplice in undermining the rights of the residents. Simone (2010) discusses contestation in terms of fundamental rights embedded in relationships among families, between men and women, patrons and clients, and citizens and government in African cities. He argues that the public sector often finds it difficult to act for the benefit of its citizens and thus takes measures to avoid being accountable to them. For him, there is no guarantee that both the private and the public stakeholders in PPPs such as municipalities, property developers, foreign and domestic investors, multilateral institutions, and popular movements can forge complementary interest. Simone's work shows that, in the absence of external help, only residents can help themselves attain their autonomy in the urban space.

2.2 Henri Lefebvre and 'the right to the city'

'The right to the city' is a concept adopted by some policymakers, academics, and activists to champion the right of ordinary individuals to take control of the process of planning and decision-making in the processes of urbanisation (Purcell, 2013: 141). The progenitor of 'the right to the city' is Henri Lefebvre, a French scholar, whose work on cities and politics spanned throughout the twentieth century, culminating in the idea of 'the right to the city'.

Lefebvre presented a radical vision for a city, in which ordinary residents have the power to manage urban space for themselves beyond the control of the government and private capital (Purcell, 2013: 141). 'The right to the city' can generally be understood as a struggle for the rights of urban residents against property rights of owners who alienate ordinary residents from accessing space and amenities in the city (Purcell, 2013: 142). The right to the city became popular when owners' property rights started to outweigh the rights of ordinary citizens to access the city. The property rights-based development led to inequality in urban areas and the rise of slums for the poor in megacities worldwide. In a bid to bring equality in cities, activists in different regions of the world started to advocate for the 'right to the city'. Brazil was one of the first countries to initiate the 'right to the city' campaign, where activists among the poor started to advocate for the 'right to the city' for slum dwellers (Purcell, 2013: 142-143).

The concept has since been adopted by international organisations such as the United Nations-Habitat and UNESCO as part of the broader agenda for human rights (UN-HABITAT 2010; UNESCO, 2006).

In order to fully understand Lefebvre's 'right to the city', there is a need to peruse his broader work on politics and cities. While Lefebvre can be viewed as a neo-Marxist, however, unlike many radical scholars during the 1960s and 1970s who supported state totalitarianism, he was critical of state socialism that came to exist in Eastern Europe and China (Purcell, 2013). For Lefebvre, not only the capitalist disenfranchised the resident's 'rights to the city', but the state was also involved in the sinister process. Hence, according to Purcell (2013: 141), "what emerges in Lefebvre's work is a Marxist that rejects the state", but instead advocates for a struggle by the ordinary people to control their destiny. Lefebvre believed that legal rights are not natural and God-given, but an outcome of political struggle (Purcell, 2013: 142). Thus, the ordinary residents of urban areas should become radically active, in order to reclaim their rights and political power from the state and private capital. Harvey (2012) agrees with Lefebvre that residents have the collective obligation to radically fight for their rights in urban spaces. Lefebvre adopts the idea of autogestion to imagine a city that is governed by its inhabitants without control of the state and capitalism. Autogestion is translated from Spanish to mean 'self-management', people managing their own affairs and making collective decisions rather than granting the decision-making process to state officials (Yap, 2019). Considering this, Lefebvre draws 'the right of the city' from the concept of autogestion.

Lefebvre's view of the genesis of urban area differs slightly from other neo-Marxist economic scholars such as Harvey who believe that urban areas are a mere special product of industrialisation. In explaining the emergence and growth of cities, Harvey argues that cities have arisen because of the concentration of surplus production of capitalism (Harvey, 2008). The mobilisation of surplus products from capitalism resulted in investments on urban infrastructure and cities emerged from the process of continuous investment on infrastructure. For Lefebvre, the 'city' is more specifically the process of industrialisation and constitutes an autonomous force of its own (Lefebvre, 2003). Urban areas are more of a human phenomenon that pre-existed capitalism and industrialisation, hence, it should be controlled by the people rather than by capital.

To avoid ambiguity when using 'the right to the city' as an analytical tool, Lefebvre gave his own definition of the city which he distinguishes from the urban. According to him, the 'city' is merely an impoverished manifestation of urban areas and an urban word reduced to economic exchange to a marketable commodity (Lefebvre, 1991: 35). Hence, although the Ruwa case study is considered a town under the Urban Councils Act (UCA) [Chapter 29:15] of 1997,1 it falls under Lefebvre's definition of a city (GOZ, 2002). In Lefebvre's city, property rights dominate all other claims to space, and the production of space is thus driven by the needs of property owners. For Lefebvre, property rights prevent ordinary people from controlling urban space. He, therefore, views 'the right to the city' as a struggle to de-alienate urban space and re-integrate it into the web of social connections (Purcell, 2013: 149-151). Drawing from the concept of autogestion and Lefebvre's 'the right to the city', this article analyses the (re) production of space in PPPs-led urban development in Ruwa Town.

3. METHODOLOGY

In assessing the characteristics of urban space under PPPs-led development in Ruwa, the article used a mixed research approach and both primary and secondary sources to derive research data. Primary data was derived from interviews based on purposive sampling targeting Ruwa residents and officials in member institutions of the PPP such as the Local Authority. The Ruwa Town Repository (Archive) was a main source of primary data. The study also employed field observations as a source of primary data, where the researcher moved around observing physical space produced by PPPs. A questionnaire was used to capture residents' opinions of the town they want. In all, 70 questionnaires were administered in various suburbs of Ruwa. Secondary sources (journals, books, articles, and newspapers) were useful in situating the Ruwa case in broader theoretical perspectives on 'the right to the city' and urban studies in Zimbabwe and the world at large. Using thematic data analysis, field observations, interviews and questionnaire results as well as information from secondary sources were tabulated and grouped under four themes, namely nature of the private-public partnership, residents' conception of an ideal town, impact of PPP-led town planning, and residents' right to access housing and amenities.

4. FINDINGS AND DISCUSION

4.1 Nature of the private-public partnership in Ruwa Town

It is imperative to first understand the partnership and administration in Ruwa, in order to comprehend the characteristics of development in the town. Ruwa was established as a growth point in commercial farming hinterland in 1986; it operated as a growth point until 1990 (Muzorewa, 2017: 3). In 1990, Ruwa started operating as an urban area2 under the administration of the Ruwa Local Board (RLB) that was set up in September the same year (Muzorewa, 2017). In 2008, Ruwa was granted town status. As early as 1987, the Local Authority in Ruwa had already engaged PLDCs by inviting them to create a partnership in service provision and town development. In the partnership, the PLDCs provided the land and constructed on- and offsite infrastructure on a build-and-transfer agreement.3 The main reason for the partnership between the RLB and PLDCs was to tap into each other's advantages. Most of the land in Ruwa was privately owned and the Local Authority had limited land for town expansion. The companies had access to land which they bought from commercial farmers and other plot holders. In addition to land scarcity, the Local Authority did not have sufficient funding to initiate development projects in the area; hence, it needed external financial investment from the PLDCs. Bedevilled by challenges related to land and finance, the RLB sought a partnership for development with the private sector.

The partnership that flourished between Ruwa local authorities and PLDCs was based on a legal document, the Regional, Town and Country Planning Act (RTCPA) [Chapter 29:12] of 1996, which provided regulations on the development permit (GOZ, 1996). The RTCPA, which provided for the introduction of the land development permit in Ruwa, was a step taken by the Government to create regulations for development. The Act created the basis for the partnership between local council authorities and developer companies. Its provisions, which included the land development permit, guided and regulated the relationship between the companies and the local authorities.4 As stipulated under the RTCPA, no development involving the change of land use and intensity of infrastructure building was allowed without a development permit (NAZ, 1995). Before any construction or development commenced, PLDCs were thus obliged to apply for a development permit to the Department of Physical Planning of the Ministry of Local Government. Development was only allowed to commence upon the approval of the application. This meant that both the PLDCs and local authorities had no absolute powers to develop land without seeking the consent of the Central Government. The Department of Physical Planning worked with local planning authorities to draft the permit and to make decisions on the permit application. Residents were not involved in the process.

The permit process gave the Ruwa local authorities control over PLDCs' development activities. Since the developers needed a certificate of compliance from the Local Authority upon finishing their projects, they were forced to comply with the Council's set standards as stated in the development permit and expectations on infrastructural development. The permit was based on the Land Development Plan (LDP) draft developed by the RLB in the 1990s. Considering this, all the infrastructure developments by PLDCs were supposed to satisfy the RLB's set standards and LDP. In this manner, the land development permit established the partnership between the Local Authority and the developer companies.

Although land was owned by PLDCs, the Council had administrative power over the land, since it was the lawful responsible authority in the area. The PLDCs' contribution in the land development permit was to provide the planning diagram showing their envisaged land subdivisions (Muzorewa, 2017). The permit was a legally binding document, and if the PLDCs failed to comply with the conditions set, the permit would either be revoked or the company would be sued (Muzorewa, 2017). By receiving the permits, the PLDCs had agreed with the terms of the permits and were aware of the implications of the permit. Between 1987 and 2020, nine major active developers operated in Ruwa, namely Mashonaland Holdings Private Limited, Chipukutu Properties, Zimbabwe Reinsurance Corporation (Zimre), Wentspring Investments Private Limited, Damofalls Investments Land Developers, Fairview Land Developers, Zimbabwe Housing Company, Barochit Property Developers, and Tawona Gardens Private Limited.

Clearly, there was no room for ordinary residents in the partnership, since it was a tripartite relationship composed of the Central Government, PLDCs and the Local Authority. The town's administration is run by the Local Authority, namely the Ruwa Town Council (RTC). A local authority is a term used in Zimbabwe to denote an administrative body mandated to offer all public services in geographical areas such as towns, cities, and rural centres. Hence, the RTC is tasked by an act of law (Urban Councils Act) with providing and maintaining public services to residents of Ruwa, by utilising funds generated from property rates fees, grants from the Central Government, and other financial sources. In Zimbabwe, every local authority consists of two parallel structures, the technical and the political. The political organ elects council members who are meant to represent the residents, while the technical organ includes professional administrators who are responsible for the running of the town's daily business. Although the elected organ of the Local Authority represents the interests of the residents, it is not involved in the day-to-day running of the town; it does take part in town planning. The absence of residents in the tripartite partnership does not mean that the residents are not conscious of the town they desire. Hence, in order to understand how residents were disenfranchised of their 'right to the city', it is imperative to capture their idea of the city they want.

4.2 Residents' conception of an ideal Ruwa Town

In principle, the Central Government and the local authorities have set standards that are meant to guarantee the needs of ordinary residents in urban areas in Zimbabwe. However, despite the set standards in the RTCPA and the development permit, the private sector partner has captured the local authorities and produced a system that does not guarantee the residents' 'rights to the city'. Merging the residents' conception of a well-developed town and the Government or Local Authority's set standards for a town reveals the major tenets of an ideal Ruwa Town. In general, an ideal town is one that provides residents with adequate urban facilities and services. Amin (2006) came up with a concept of 'the good city'. He argues that a good city values difference, publicises the commons, and crowds out the violence of urbanism of exclusionary and privatise interest. He defines a good city as an expanding habit of solidarity with social justice, equality, and mutuality (Amin, 2006: 1010). Friedmann (2000) added four pillars of a good city to Amin's description of a good city. He identified pillars that include provision of decent housing, affordable healthcare, reasonably remunerated work, and adequate social provisions as basic tenets of the good city. Amin and Friedmann's good city closely resembles the ideal Ruwa Town.

The processes of ascribing urban status to rural areas in Zimbabwe sheds light on the Central Government's concept of an ideal town. The Government of Zimbabwe, through the Urban Councils Act [Chapter 29:15] of 1997, ascribes local authority, town, and municipal or city status to an area after its local authority applies for such status to the Ministry of Local Government (GOZ, 2002). Upon receiving the application, the Minister sets up a commission with a mandate to make recommendations for a change in status and the commission bases its assessment on issues that relate to urban administration, population, service provision, and infrastructure development, among others. Another document that helps define an ideal town is the Local Development Plan (LDP). Local authorities are required by law, through the RTCPA [Chapter 29:12], to prepare a LDP that gives major directions to development and planning in a town (GOZ, 2002). The LDP sets aims and objectives and the main trajectory for the future development of a town. The development aims of Ruwa Town, as presented in the LDP, provide insights into the ideal town desired by the Local Authority.

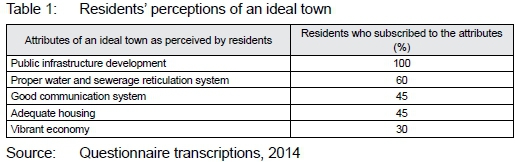

Residents also had their own idea of a town (see Table 1) which is slightly different from that of the Central Government or Local Authority.

The Urban Councils Act requires the Ministry of Local Government to consider service infrastructure development when establishing urban councils. The Act requires an area to be assessed in terms of the local authority's ability to provide services such as water and sewerage, public parking, firefighting and ambulance services. As illustrated in Table 1, 60% of the interview respondents are residents who pointed out that an ideal town should have proper water, sewerage, and refuse collection services. When the LDP was designed, it envisaged the provision of basic services for the residents. This blueprint for Ruwa aimed to develop a sewerage and water reticulation system which, in future, would cater for 90 000 people accommodated and employed in the town (RTC, 1996). An ideal town, therefore, should provide basic services for its residents.

Table 1 is part of data deduced from the questionnaire that was used as one of the data-gathering tools. It shows residents' perceptions of an ideal functional town. All respondents to the residents' questionnaire felt that an ideal town should have adequate public infrastructure that provides for the society's needs.

The LDP emphasised setting aside land for health and education infrastructure. Ministry of Health standards required a clinic for every 10 000 people in an area. Based on the Ministry's standards, the LDP envisaged the establishment of seven district hospitals in the town by the end of the planning period of 2015 (RTC, 1996: 12). The development plan also emphasised the development of a range of social amenities that accommodated cultural and recreational needs.

The other important aspect of an ideal town is commerce and industry. The UCA requires an area to be assessed based on the extent of its influence as a national centre for commercial and industrial purposes before it can be upgraded to a town (GOZ, 2002). Thirty per cent of the interview respondents argued that an ideal town should have a vibrant local economy characterised by industrial growth. To support this, one of the major objectives of the LDP was to safeguard Ruwa against turning into a residential settlement without economic activities (RTC, 1996: 2). In simple terms, the Local Authority feared that, if Ruwa did not develop a strong industrial centre, it would become a dormitory town, providing a residential area for Harare. The LDP, therefore, had to ensure the growth of a commercial self-reliant town with a central business district (CBD) for the promotion of commerce and centralised business.

Communication services were regarded as essential for development. Forty five per cent of residents who responded to the questionnaire believed that an ideal town is made up of a good communication system. Therefore, the UCA considered the state of an area's roads, rail, postal and telecommunication services before upgrading the status of its urban council (GOZ, 2002). The LDP envisaged the construction of an inter- and intra-linkage road system in Ruwa by the end of the planning period in 2015 (RTC, 1996: 28). Residents also advocated for quality and well-maintained roads without potholes.

For a growing town, the availability of housing schemes designed for low-income earners is essential. The availability of decent housing is among Friedmann's pillars of the good city. It follows that most of the residents believed that an ideal town should have adequate housing to accommodate poor residents. The LDP proved that the planners were also aware of the possible dangers of alienating the low-income earners in a private sector-developed town. Since most of the land was privately developed, there was a risk of selling plots or land to wealthy persons who may not be employed in Ruwa (RTC, 1996: 8). This, however, could not be avoided, as the RLDP did not make provisions for plots to be affordable to the poor seeking to be allocated land in the high-density suburbs.

Security is one tenet of the ideal town. The UCA requires an area to offer state services such as police stations, courts, and prisons before it can be given urban status. According to the LDP, there should be police services in a town to guarantee security and positive development (RTC, 1996: 33). The police stations should be accessible and close to the community. Law-enforcement agents bring social order and control crime, thereby promoting growth in society. This argument is supported by the two legal documents (the Urban Councils Act and the RLDP) responsible for the establishment of Ruwa Town.

Electricity supply services have been widely linked to an ideal town. The LDP considers the supply of electricity and related infrastructure in the town to be the responsibility of the national power utility company (RTC, 1996: 12). Residents believe that the availability of electricity supply distinguishes an urban from a rural area. Electricity supplied by the power authority is vital for industrial growth. Industrial growth, in turn, promotes urbanisation.

Last, but not least, an ideal town is characterised by good environmental management, tourism, and tourist facilities such as hotels and motels. Pollution and deforestation should be minimised for development to take place (RTC, 1996: 16). These characteristics of an ideal town, therefore, provide the basis for an evaluation of the characteristics of the PPPs produced urban space and the 'right to the city' in Ruwa Town. It is, however, important to note that issues related to residents' participation in town governance were never raised in legislation meant to provide tenets of the ideal town. Most of the residents were not aware of their ability to attain utogestion and 'the right to the city'.

4.3 The impact of PPP-led town planning on 'the right to the city'

This section uses the concept of the ideal Ruwa Town to measure the PPP-produced urban space as it relates to the 'right to the city'. The subdivision permit system provided for in the PPPs agreement in Ruwa resulted in piecemeal and uncoordinated planning which met the needs of the developers without considering the ordinary residents. This planning process left Ruwa without a proper nucleus for commercial and business activities that serve the ordinary residents. Yet a CBD is one of the central tenets of the resident's ideal town. The lack of a CBD was a result of piecemeal planning which characterised the early stages of Ruwa's development. Chigara et al., (2013: 27-32) describes piecemeal planning as a methodology for planning that is realised through the use of a number of independent different micro-layout plans. This type of planning has been associated with a myriad of weaknesses, including lack of harmony in land use, uncoordinated developments, sprawling environments, and disorderliness. In Ruwa, piecemeal planning was a result of the use of many different micro-layouts from different PLDCs. Every PLDC prepared its own plan showing a subdivision diagram. It was not possible for PLDCs to harmonise their micro-layout plans, since their developments occurred in different periods and they had different interests while they competed for space on the land market in Ruwa.

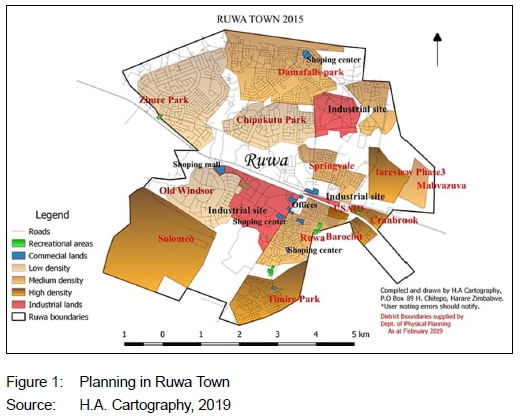

Piecemeal planning resulted in different zones in Ruwa that are located further apart, as illustrated in Figure 1. Lefebvre (1991: 317) notes that, under capitalism, the space in the city is carved up into isolated segments by the system of private property. The planning system segregates land uses into discrete zones by producing detailed plans for land use. This separation of land uses divides users from each other, storing them in sterilised spaces, which Lefebvre calls habitats, thereby preventing them from coming together in spaces of encounter, play and interaction (Purcell, 2013: 149). In Ruwa, the PLDCs created different suburbs, some categorised as high density and others as low density. This zoning created classes, making it impossible for residents to unite and claim their 'right to the city'.

The pro-profit planning process, illustrated in Figure 1, made Ruwa a dormitory town of Harare. PLDCs developed more residential areas than industrial and commercial areas, because residential plots were easy to sell as a result of a huge housing market caused by the failure of urban authorities to provide the required accommodation. The number of residential areas outgrew the industrial parks in Ruwa, thereby causing a degree of dependency for jobs and services on Harare. Generally, between 2000 and 2008, Zimbabwe was facing an economic crisis that led to the collapse of the manufacturing industry. However, despite the collapse of industries, housing continued to be a basic necessity among people in the country, causing high demand for residential plots and low demand for industrial plots. Most of the PLDCs, in their quest to make profit, were influenced by market forces to demand residential over industrial plots. Some PLDCs went an extra mile to the extent of altering the LDP which had zoned areas for industrial development, in order to pursue their interest in developing residential parks. For example, the Zimbabwe Housing Company changed an area zoned by the LDP for industrial development into a high-density residential suburb in 1997. According to the LDP, Lot One of Cranbrook Farm was zoned for industrial and institutional purposes (Palmer Associates, 1996). The company, in its own way, influenced the Local Authority into changing the planned purpose of the land. By creating very large residential parks with smaller industrial areas, the PLDCs killed the local economy and made Ruwa vulnerable to the metropolis (Harare), only 23km away. This scenario took Ruwa further from the residents' 'ideal town'.

Besides killing the local manufacturing industry, the PPPs' poor planning for water sources aggravated the water crisis in the town. The non-availability of funds to build offsite infrastructure, which included water reticulation systems, was one of the major reasons why the RLB decided to partner with the PLDCs, who, it was presumed, would contribute towards the construction of the required facilities. Although there were over three decades of a partnership between the Local Authority and the PLDCs, water challenges still bedevil Ruwa Town by 2021. The PLDCs were responsible for the population boom in Ruwa. They developed houses, residential plots, industrial plots, and other commercial properties which then attracted a huge population. Davison (2001: 150) attributed the challenges in water supplies in urban areas to rapid population growth. The demand for water in Ruwa outstripped supply. The Local Authority was unable to cope with the growing population's demand for water, due to financial constraints.

Both the Local Authority and PLDCs were aware of the repercussions of continuing with residential development without improving water sources for the town, but they deliberately ignored them. In 1996, in a letter to the Northern PLDCs, the RLB notified them that the City of Harare had advised that it was no longer able to increase water allocation for Ruwa (RTC file CPP, 1996). The situation was to remain so until Kunzvi and Musami dams were constructed (RTC file CPP, 1996). The RLB then advised the PLDCs to consider their applications for land subdivision and development considering the water predicament (RTC file CPP, 1996). However, despite the warning, over three quarters of the development permits were issued after 1996 when Kunzvi and Musami dams were not completed. This meant that the PLDCs and the Local Authority continued increasing development projects that required more water, without creating a plan for the development of water sources. This aggravated the water crisis, yet water supply is among the major tenets of the residents' ideal Ruwa Town.

Besides water issues, the residents of the low-density Zimre Park in Ruwa complained numerously about being left out in the planning process of their surrounding area. In 2010, for instance, they complained about a neighbouring plot which had its status changed from residential to commercial property. These residents were concerned that the construction of a liquor store on the neighbouring plot would result in noise and a high crime rate (The Herald, 2010: 3). In response, the RLB boldly declared that the Zimre Park development permit had ascribed commercial status to the plot and the Local Authority could not change that (The Herald, 2010: 3), thus proving that the residents had no 'right to the city'. The Board then advised the residents to verify what the development permits stipulated and check the developments that were planned around their properties before they purchased land from the PLDCs (The Herald, 2010: 4).

This meant that residents had no say in the planning of their area.

Residents of Ward Seven of the Ruwa high-density suburb complained about poor planning in their suburb, citing the location of beer outlets near residential houses. Just adjacent to four church buildings, there are bottle stores and a night club surrounding residents' houses. In an interview on 18 March 2015, residents complained about the noise from both the beer outlets and the churches, especially when musicians visit for some gigs. Some residents felt that churches and beer outlets should have been placed at the town centre, away from their homes. If residents had shaping power of their town, they could have rectified such problems, but they could not. That right belonged to the PLDCs who drew up site plans before selling the residential and commercial plots to the people.

As postulated in Lefebvre's work, town development should have a bearing and impact on the lives of the residents and the nation as a whole. The private sector has often been criticised for maximising profits at the expense of its customers. There is a general belief among stakeholders that PLDCs bring "cosmetic" urban development, characterised by infrastructure and amenities that are not accessible to ordinary residents. Clearly, there was minimum participation of the residents and ordinary people in the shaping and planning of the town. Residents merely became passive objects of a town designed following the desires of PLDCs, the Council and the Central Government. In some instances, the desires of the PLDCs overwhelmed those of the Local Authority and the Central Government. The disenfranchisement of the residents to shape their town was tantamount to taking away their 'right to the city'.

4.4 The residents' right to access housing and amenities in Ruwa Town

Besides alienating the residents from the planning process, PPP-led development alienated the poor and the low-income earning class from accessing housing and services in the town. When the local planners drafted the LDP, the low-income earners were not catered for, since they could not afford the prices charged for housing by private developers. Through land development permits, the Department of Physical Planning and the RLB tried to address the issue by making it compulsory for some PLDCs to set aside land (housing schemes) for low-income earners. However, low-income earners interested in buying the plots were supposed to apply to the Local Authority and have their names listed on the Ruwa Housing List. Interviews conducted in 2014 and in 2021 suggest that those on the list were supposed to get preference whenever a low-income housing project was available, but the prices of the plots were too high for low-income earners.

The number of people on the Ruwa Housing Waiting List, thus, continued to grow despite the provisions given by the land development permit to reserve land for low-income earners. In 1995, the list had over 3 000 home seekers and, by 2007, the list had 5 000 home seekers (Chirisa, 2012). An interview with the Town Planner reveals that, after 2008, the Local Authority stopped publishing the number of people on the housing waiting list, because the rising numbers were attracting criticism from various development stakeholders in the town. When the Zimbabwean economy slightly revived in 2009, most of the plots were selling for around US$ 10 per m2 and, by 2020, the price had risen to an average of US$ 35per m2 (RTC file CAA, 2020). This amount was too high for low-income earners and civil servants in Ruwa who were earning roughly US$ 50 per month by 2020. Civil servants in normal economies should be part of the middle class. However, the economic crisis in the country has eradicated this middle class. Most of the low-income earners could not afford the PLDC-developed houses, yet access to affordable housing was a top tenet of the residents' ideal Ruwa Town.

The Ruwa scenario is similar to that in London, as described by Harvey (2008). When Margaret Thatcher (the then British Prime Minister) privatised the development of social housing, rents and housing prices rose and, ultimately, low-income earning and middle-class people were precluded from accessing housing in areas near the urban areas. Similarly, PPP-led development alienated the low-income earning class from housing in Ruwa and most of the poor people were relegated to neighbouring poor settlements such as Epworth.

The Ruwa Shopping Centre infrastructure remained in the hands of private companies and became more relevant to the affluent than to low-income earners. The Ruwa case is similar to the one in Los Angeles (LA) described by Friedmann (2000), where the poor were excluded from shopping mall services. In LA, shopping malls charge retailers and service providers high rentals to the extent that the shops became exclusive in nature (Friedmann, 2000). These shopping malls allowed only those who could afford to buy expensive merchandise to use its services and enjoy glamorous waterfalls and glittering mirrors. In Ruwa, the land development permits given to developers created provisions for the establishment of exclusive shopping malls.

The Ruwa Shopping Centre constructed and owned by a private company is located in Windsor Park, a leafy suburb adjacent to Zimre Park. Interviews with proprietors at the shopping mall suggest that rentals were exorbitantly high on these and other private premises and commercial buildings in Chitungwiza, High Glen, Westgate, and Eastgate in Harare. In order to make up for the high rental costs, tenant shop owners at the shopping mall raised the prices of their goods and services. This made the centre exclusive, as it alienated most of the ordinary Ruwa residents. Interviews with Ruwa residents revealed that ordinary residents preferred to go to Harare to access services, because they could not afford those at the Ruwa Shopping Centre. Only a few affluent people mainly from the Ruwa's leafy and affluent suburbs of Old Windsor Park and Zimre Park benefited from the Ruwa Shopping Centre. This led to what can be termed 'cosmetic' development, a situation where infrastructure and services are available, but the larger population in the area cannot access them.

PPP-led development in Ruwa resulted in inadequate and expensive public infrastructure. Eighty per cent of the interviewed respondents complained about inadequate public infrastructure such as education facilities (schools), public health facilities, and recreational amenities. Areas designated for the development of public amenities were controlled by the private sector, and when the Local Authority failed to buy land designated for public use, the land was sold to private property developers (RTC file CCP, 1998). This was the case of school sites in Zimre Park, for example. Land designated for developing schools was taken over by the private sector after the Local Authority failed to build public schools (RTC file CCP, 1998). A Zimre Park land developer argued that, if the responsibility of providing schools was left solely to the RLB, it would take long for Zimre Park to establish schools (RTC file CCP, 1998). Their justification was that the RLB had taken almost eight years to construct the one and only public primary school in the area. In light of this, most of the land that was designated for the development of public infrastructure reverted to land developers after the Local Authority had failed to develop it. Prices charged by private entrepreneurs were high. All private schools and hospitals were beyond the reach of many Ruwa residents. In 2014, a field survey showed that private schools such as Arial School charged USD800 in school fees and Windsor Primary School was charging USD500 while public schools in the area, Thornicroft and Chiremba, charged less than USD60 per term. In the health sector, private medical centres did not accept public service medical aid schemes. Most of the low-income earners were on public medical aid schemes and this alienated them from local health facilities, resulting in 'cosmetic' development.

Land set aside for public infrastructure development such as schools, clinics, recreational parks, crèches, halls, and sporting arenas, however, remained practically undeveloped, because it was more profitable for PLDCs to develop residential plots than public and other supporting infrastructure. The development of residential plots was in response to the high demand for houses in Ruwa, in particular, and Zimbabwe, in general (Tama Consulting Surveyors, 1999). For example, in Zimre Park, five sites were set aside for schools, but a field survey showed that only two schools were developed by 2020. Despite land being designated for the construction of polyclinics in Fairview and Damofalls, and sites being reserved for primary schools in Damofalls Park, none of the infrastructure was constructed, thus resulting in inadequate public infrastructure in Ruwa. The availability of public infrastructure is among the tenets of the residents' ideal town.

Field observation shows that in some areas developed by PLDCs such as Damofalls Park, Fairview and Chipukutu Park, there was evidence of sub-standard offsite infrastructure. This was a result of some PLDCs' methods of cutting construction costs by using cheap and substandard material when developing infrastructure. This impacted negatively on some off-and onsite infrastructure in Ruwa, especially roads. Field observation showed that the road system in Ruwa was in a bad state, characterised by potholes and gravel roads, in some cases with gullies developing because of soil erosion. The poor road system was a result of PLDC-led substandard construction.

Although roads easily caught the observer's eye, they were not the only substandard offsite infrastructure in some PLDC-developed areas. Most of the residents complained about the poor water and sewerage reticulation system in Ruwa suburbs. The Town Planner also blamed PLDCs for taking advantage of the poor expertise of the Council's inspectors and using substandard building materials to minimise the cost of putting up water and sewerage facilities. Some Council or Local Authority inspectors, who approved and gave PLDCs certificates of compliance, were not experts in engineering. In one of the interviews conducted, it was indicated that, in some instances, the Council officers approved substandard infrastructure because they lacked proficiency, or some Council officials were corrupt. When the water infrastructure in Springvale Park was constructed in 2009, it is alleged that the developer took advantage of corruption at the Zimbabwe National Water Authority (ZINWA) to bribe the inspectors, and used water piping with a smaller diameter than the one recommended (Muzorewa, 2017). The use of substandard material resulted in long-term high maintenance costs of the infrastructure. The Local Authority bore the cost of maintenance, as it had inherited the infrastructure from private developers.

There are many cases of PLDCs failing to deliver the infrastructure they were required to develop by the planning authorities through the land development permits. Residents in the low-density suburb of Chipukutu Park, for example, were asked to buy electricity poles and transformers for their suburb when it was the responsibility of the developer to contract the national power utility company for the electrification of the area. A similar situation happened in Barochit Park high-density suburb, where residents were asked to buy poles for electricity installation in their area. The eighth condition of the permits made it clear that the developers should meet all the costs of installing electricity in the areas they developed (RTC, 1993). Clearly, some PLDCs ignored this clause of the permit, taking advantage of a futile Town Council and giving residents the responsibility of installing electricity. This led to uneven electricity supply to areas in the same suburb because, while some residents could afford the poles and transformers, others could not. The low- and high-density divide made residents of Chipukutu Park and Barochit Park fail to unite and fight for their rights to electricity.

One of the characteristics of an ideal town is well-developed offsite and public infrastructure with a good road and communication network. Some of the PLDCs compromised the quality of infrastructural development in the town, due to their desire to minimise construction costs and the need to retain as much profit as they could. However, not all PLDCs used unethical ways to minimise cost at the expense of town development. There is evidence of quality offsite and supporting infrastructure in areas such as Mashonaland Holdings-developed Ruwa and Zimre Park. However, cases of PLDCs that were not performing to standard were a major concern and took away ordinary residents 'rights to the city'.

5. CONCLUSION

This article analysed the characteristics of PPP-led produced space in Ruwa Town. Lessons from Ruwa Town can offer insights into PPP-led development in other emerging towns in Zimbabwe. The Ruwa case is a micro example of the macro terrain of PPP-led development in Zimbabwe, since after Ruwa, PPPs have been adopted as an urban development model in other towns such as Norton, Harare, Kwekwe, Gweru and Bulawayo, among many others. The analysis is based on the attributes of an 'ideal town' which is a set of ideas formed out of residents' and Local Authority's dream of a developed and well-planned Ruwa. Although the local authorities started with a good intention of putting public interest first, they were negatively influenced by the private developers in the PPP and ended up leveraging the interests of the developers. The PPP took away the ability of residents to shape their environment as they pleased. Residents simply bought land in areas designed by PLDCs and had no say in the shaping and development of the areas. The vast majority of low-income earners could not afford plots and facilities developed by the companies, because the private sector charged prices that were way beyond the reach of low-income earners. In some areas developed by PLDCs, the quality of infrastructure was poor. Roads were the most vivid example of poor infrastructure in areas such as Damofalls and Chipukutu.

Developer companies brought a disjointed type of planning in Ruwa and took away the drive to create a major CBD for the town. The developers implemented their own micro plans which tended to duplicate some infrastructure within a small area. Since this planning provided for isolated public infrastructure and service facilities in different residential suburbs of Ruwa, the urgency for the development of a robust local economy which benefits the locals was overlooked. The companies contributed to relatively low local economic activities by concentrating on providing residential plots that were profitable to them. These were prioritised over the development of industrial parks. Ruwa was also bedevilled by water challenges which the PLDCs could not rectify on their own. Ruwa's water predicament was exacerbated by the fact that the companies increased the demand for water, developing more residential areas while there were no water sources to supply the people. PLDCs faced a number of challenges in providing water infrastructure and other services. Hence, at times, much negativity was associated with PLDC-led development. Overall, the article illustrated how ordinary residents of Ruwa have been alienated regarding issues of planning and administration of their town. The Ruwa case fits well in Lefebvre's discussion of 'the right to the city'. The lack of resident participation gave the power of decision-making to the private sector and the Local Authority. This article recommends that residents should be engaged in affairs that affect their daily urban lives. This engagement should not be only through political representation in the Town Council but also through residents' committees and various other platforms of interaction. Only active participation in town affairs will restore autogestion and 'the right to the city' to the residents of Ruwa Town.

REFERENCES

AMIN, A. 2006. The good city. Urban Studies, 43(5/6), pp. 1009-1023. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600676717 [ Links ]

BOVAIRD, T. 2004. Public-private partnerships: From contested concepts to prevalent practice. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 70, pp. 199-215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852304044250 [ Links ]

BRENNER, N. & THEODORE, N. 2002. Cities and geographies of actually existing neoliberalism. Antiphode, 33, pp. 349-379. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00246 [ Links ]

CHIGARA, B., MAGWARO-NDIWENI, L., MUDZENGERERE, F. & NCUBE, A. 2013. An analysis of the effects of piecemeal planning on development of small urban centres in Zimbabwe: Case study of Plumtree. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 15(2), pp. 27-40. [ Links ]

CHIRISA, I. 2012. Housing and townscape: Examining, inter alia, international remittances' contribution to Ruwa's growth. Global Journal of Applied, Management and Social Sciences, 3, pp. 125-133. [ Links ]

DAVISON, C.A. 2001. Urban governance and the effective delivery and management of infrastructure services in urban areas in Zimbabwe: An appraisal of water and sewerage services delivered in Ruwa. Urban Forum, 12(2), pp. 139-170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-001-0014-6 [ Links ]

DIDIER, S. & PEYROUX, M.M. 2013. The adaptive nature of neoliberalism at the local scale: Fifteen years of city improvement districts in Cape Town and Johannesburg. Antipode, 45(1), pp. 121-139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.00987.x [ Links ]

FRIEDMANN, J. 2000. The good city: In defense of utopian thinking. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 24(2), pp. 460-472. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00258 [ Links ]

GOZ(GOVERNMENT OF ZIMBABWE). 2002. Section 14 of the Urban Councils Act, distributed by Veritas Trust, as amended to November 2002. [ Links ]

GOZ (GOVERNMENT OF ZIMBABWE). 1996. Regional, Town and Country Planning Act. Harare: Government Printers. [ Links ]

H.A. CARTOGRAPHY. 2019. Planning in Ruwa Town. Unpublished map. [ Links ]

HARVEY, D. 2008. The right to the city. New Left Review, 53(September-October), pp. 23-40. [ Links ]

HARVEY, D. 2012. Rebel cities: From the right to the city to the urban revolution. London: Verso. [ Links ]

HODGE, G.A. & GREVE, C. 2007. Public-private partnerships: An international performance review. Public Administration Review, 67, pp. 545-558. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00736.x [ Links ]

JESSOP, B. 2002. Liberalism, neoliberalism and urban governance: A state theoretical perspective. Antipode, 34, pp. 452-472. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444397499.ch5 [ Links ]

KLEIN, M. 2015. Public-private partnerships: Promise and hype. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-7340 [ Links ]

KLIJN, E.H. & TEISMAN, G.R. 2003. Institutional and strategic barriers to public-private partnership: An analysis of Dutch cases. Public Money & Management, 23, pp. 137-146. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9302.00361 [ Links ]

LEFEBVRE, H. 1991. The production of space. (D. Nicholson-Smith, Transl.). Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

LEFEBVRE, H. 2003. The urban revolution. (R. Bononno, Trans.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

LEIGLAND, J. 2018. Public-private partnership in developing countries: The emerging evidence base critique. The World Bank Research Observer, 33, pp. 103-134. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkx008 [ Links ]

MIRAFTAB, F. 2004. Private-public partnerships: The Trojan horse of neo-liberal development. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 24(1), pp. 89-101. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X04267173 [ Links ]

MIROWSKI, P. 2013. Never let a serious crisis go to waste: How neoliberalism survived the financial meltdown. London: Verso. [ Links ]

MOSZORO, M. & KRZYZANOWSKA, M. 2011. Implementing public-private partnership in municipalities. Spain: IESE Business School, University of Navarra. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1679995 [ Links ]

MUZOREWA, T.T. 2017. The role of private land developers in urban development in Zimbabwe: The case of Ruwa Town, 1980-2015. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis. Zimbabwe: Midlands State University. [ Links ]

MUZOREWA, T.T. 2020. Public and private-led urban development in post-colonial Zimbabwe: A comparative study in Ruwa Town. Urban Forum Journal, 31(2), pp. 197-213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-020-09386-5 [ Links ]

NAZ (NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF ZIMBABWE). 1995. Ministry of Local Government, Rural and Urban Development, Department of Physical Planning pamphlet no. 38971. [ Links ]

PALMER ASSOCIATES PRIVATE LIMITED. 1996. Proposed developments of Lot 1 of Cranbrook of Ruwa. [ Links ]

PECK, J. & TICKELL, A. 2002. Neoliberal space. In: Brenner, N. & Theodore, N. (Eds). Spaces of neoliberalism: Urban restructuring in Western Europe and North America. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 33-57. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444397499.ch2 [ Links ]

PINSON, G. & JOURNEL, M.C. 2016. The neo-liberal city: Theory, evidence, debates. Politics, Governance, Territory, 4(2), pp. 137-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2016.1166982 [ Links ]

PURCELL, M. 2013. Possible worlds: Henri Lefebvre and the right to the city. Journal of Urban Affairs, 36(1), pp. 141-145. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12034 [ Links ]

RTC (RUWA TOWN COUNCIL). 1993. Permit for the subdivision of land: Chipukutu Properties. [ Links ]

RTC (RUWA TOWN COUNCIL). 1996. Ruwa Local Development Plan. [ Links ]

RTC (RUWA TOWN COUNCIL). File CAA. 2020. Receipt for permit from Damofalls, 23 October 2020. [ Links ]

RTC (RUWA TOWN COUNCIL). File CPP. 1996. Letter from Ruwa Local Board to the northern properties, 2 October 1996. [ Links ]

RTC (RUWA TOWN COUNCIL). File CPP. 1998. Correspondence between RLB and Zimre, 14 October 1998. [ Links ]

SIMONE, A. 2010. The social infrastructures of city life in contemporary Africa. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. [ Links ]

SKELCHER, C. 2005. Public-private partnerships and hybridity. In: Ferlie, E. (Eds). The Oxford handbook of public management. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 347-370. [ Links ]

TAMA CONSULTING SURVEYORS. 1999. Proposed subdivision of the remaining extent of York of Galway Estate. Paper for Wentspring Private Limited. [ Links ]

THE HERALD. 2010. Local Board must explain development. 26 February 2010. [ Links ]

UNESCO (UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION). 2006. International public debates: Urban policies and the right to the city. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

UN-HABITAT. 2010. The right to the city: Bridging the urban divide. Rio de Janeiro: World Urban Forum, United Nations. [ Links ]

WETTENHALL, R. 2010. Mixes and partnerships through time. In: Hodge, G.A. (Ed.). International handbook on public-private partnerships. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, pp. 17-42. [ Links ]

YAP, C. 2019. Self-organisation in urban community gardens: Autogestion, motivation and the role of communication. Sustainability 11(2659), pp. 1-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092659 [ Links ]

Received: May 2021

Peer reviewed and revised: October 2021

Published: December 2021

* The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

1 The Urban Council Act [Chapter 29:15] of 1997 is the legislation that governs urban development in Zimbabwe and is responsible for creating hierarchies of urban areas and administration.

2 Zimbabwe's local government comprises 28 urban councils and 58 rural district councils. The two types of councils derive their authority from the Urban Councils Act and the Rural District Councils Act. There is a hierarchy in the urban councils in Zimbabwe. The urban council's hierarchy which starts from consolidated villages, followed by business centres, rural service centres, district service centres, growth points, towns and then cities. The 1987 Amendments of the Urban Councils Act have included a local board between a growth point and a town and a municipal between a town and a city. Ruwa Town Council (RTC) is the local authority in Ruwa. In this study, whenever the word local authority is used in reference to Ruwa, it will be synonymous to Ruwa Local Board, Ruwa Town Council, and the Council.

3 Under the Build and Transfer agreement, the PLDCs constructed on- and offsite infrastructure that included roads, water and sewerage reticulation systems and other supporting public amenities. The developers then handed over the infrastructure to the local authority once construction was completed. PLDCs benefited from the opportunity from the Council to subdivide their land and sell it for profit and the Build and Transfer concept was part of endowments they paid to the Local Authority.

4 A development permit or planning permission is a document issued to a land developer by the Department of Physical Planning before any development is carried out. The document contains conditions to be adhered to by the developer and some guidelines during the development process.