Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Town and Regional Planning

On-line version ISSN 2415-0495

Print version ISSN 1012-280X

Town reg. plan. (Online) vol.78 Bloemfontein 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp78i1.5

ARTICLES

Changing urban management doctrines in Cape Town, South Africa

Veranderende leerstellings vir stedelike bestuur in Kaapstad, Suid-Afrika

Phetoho ea boithuto ka tsamaiso ea litoropo Cape Town, Afrika Boroa

Jens Kuhn

Mr Jens Kuhn, formerly Manager: Housing Land and Forward Planning, Cape Town City Council, PO Box 1410, Milnerton, 7441; Phone: 072 810 4650, email: <jenskuhn@kingsley.co.za>

ABSTRACT

This review article reflects on the history and growth of Cape Town from its founding to its present. In doing so, it identifies a sequence of six distinct attitudes towards urban growth and management. Such attitudes often remained unarticulated, for they appeared self-evident, even natural, to the society of their times. These attitudes coincide with the concept of Planning Doctrine, as proposed by Faludi, and lie silently behind actual policymaking and development of the day. Yet the Doctrine changes over time in response to political values, economic restructuring and settlement scale. Six doctrines dominated for a period of roughly 40 years each, termed by the author as corporate management; self-help; public works; town planning; up-scaling, and transformation.

Keywords: Doctrine, spatial growth, urban management, Cape Town

OPSOMMING

Hierdie oorsigartikel reflekteer op die geskiedenis en groei van Kaapstad vanaf stigting tot vandag. Sodoende identifiseer dit 'n reeks van ses verskillende houdings teenoor stedelike groei en bestuur. Sulke gesindhede is dikwels nie uitgespreek nie, want dit was vanselfsprekend, selfs natuurlik, vir die samelewing van hul tyd. Hierdie houdings val saam met die konsep van die beplanningsleer soos voorgestel deur Faludi en lê stil agter die werklike beleidsvorming en -ontwikkeling van die dag. Tog verander die leerstelling oor tyd in reaksie op politieke waardes, ekonomiese herstrukturering en skaal. Ses leerstellings het oorheers vir 'n tydperk van ongeveer 40 jaar elk en word deur die outeur geïdentifiseer en bestempel as korporatiewe bestuur; selfhulp; openbare werke; stadsbeplanning; opskalering, en transformasie.

Sleutelwoorde: Leerstelling, ruimtelike groei, stedelike bestuur, Kaapstad

SA BONAHALENG

Sengoloa sena sa tlhahlobo se bonts'a nalane le kholo ea Cape Town ho tloha ts'imolohong ea eona ho fihlela joale. Ka ho etsa sena, se supa tatellano ea maikutlo a tseletseng a fapaneng mabapi le kholo le taolo ea litoropo. Maikutlo a joalo hangata a ne a lula a sa tsejoe, hobane a ne a shebahala a hlakile, ebile e le a boleng ba sechaba sa mehleng e'o. Maikutlo ana a tsamaellana le mohopolo oa thuto ea ho rala, a hlahisitsoeng ke Faludi, mme o neng o ipatile ka mora ketso ea melao le nts'etsopele ea mehleng e'o. Leha ho le joalo, ha nako e ntse e ea, lithuto li tsa fetoha, ele ho arabela boleng ba lipolotiki, ntlafatso ea moruo le boholo ba metse. Lithuto tse tseletseng li laotse ka nako ea lilemo tse ka bang 40, e 'ngoe le e' ngoe e bitsitsoe ke mongoli molemong oa tsamaiso ea litsi; ho ithusa; mesebetsi ea sechaba; meralo oa litoropo; ntlafatso, le phetoho.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the natural sciences, a 'paradigm' refers to a way of thinking about a distinct set of problems and how they are best viewed and solved (Kuhn, 1970: 10-34). An unconventional approach to such problems would be regarded as outside the prevailing paradigm (Kuhn, 1970: 10-34). Drawing on this insight, Faludi (2004: 231) refers to what he terms the Planning Doctrine. A planning doctrine is a constellation of assumptions and beliefs that strongly influence how policymakers consider specific urban problems and their best solutions (Faludi & Van der Valk, 1994: 18). Should the state be prescriptive or permissive? Should developers be serving their clients' or the public interest more generally? Should communities seize the initiative or demand welfare? Positions on these spectrums are bound to be instinctive more than articulated. Importantly, the doctrine is not limited to the planner, developer, citizen or the public official, but to everyone active in the field of urban matters.

In social settings, the doctrine serves to gather alliances and to create coalitions around specific planning solutions (Faludi, 1999: 333).

It makes doctrines the strongest form of influence planners exercise on the urban agenda - that is, until such time as anomalies begin to appear or "explosive issues" arise that undermine its coherence and logic, or once, by general consent, it no longer applies to the actual urban problems being confronted (Friedmann & Weaver, 1979: 2). It is then that the doctrine lying behind prevailing urban management practices is due for replacement or major reform. However, until such moments of crisis arise, urban development practices remain "normal", that is without self-doubt about their efficacy or consequences. Paradoxically, at moments of "crisis", less conventional views are taken, or original and refreshing policy reformulations are tabled (Kuhn, 1970: 77-79).

2. METHODOLOGY

The conviction prompting this article is that the ideas in society about how human settlements ought to be built and cared for, change with time. In due course, one idea gets to dominate for a while and that idea gets adjusted and replaced periodically in direct response to two fundamental shifts over time - scale and technology. This insight cannot be scientifically proven in the form of hypothesis - refutation, only proposed as an interpretation made from a careful historical reading, thus making a persuasive argument. To identify and characterise the periods, the following method is used: a concept to keep track of the idea is introduced - in this case 'urban management'. The raw material against which to deduce such changes was then lined up, with greater Cape Town offering the case material. In respect of scale, three elements exhibiting urban change were profiled: demographics; the physical footprint of the city, and its economic growth and size.

Books and articles related to Cape Town's history and its engineering endeavours were derived from several public libraries in the city. The primary source of information used to formulate an accurate picture of Cape Town's growth over time was a digital layer of its land parcels, obtained online from the Council's DataPortal, which included old aerial photos and maps. Analysing it with respect to dates, land-use zoning and spatial extent, and using GIS software yielded a set of urban footprints. These were timelined and compared quantitatively, from which could be inferred the pace and nature of change in terms of land development.

Council Minutes held in the Planning Library, in 44 Wale Street, Cape Town, as well as data from the Statistics SA website were reviewed. This allowed a verification of whether the said areas were, in fact, under discussion or dispute at the expected dates. It also confirmed the role of the public sector in the greater picture of urban development. A check with the official censuses was made to verify the observed rises and declines of urban growth by comparing them to demographic trends. Hard copies were used for the period prior to 1960. The Statistics SA website allowed for the mining of data in various ways and years. Another useful publication was that by the Institute of Race Relations, giving information tables on economics and population post-1960.

In the knowledge that the above, specifically the digital land parcel information, relates only to the formal growth, an ever-increasing share of urban growth is informal, i.e. not regulated. To cover this, a digital information layer based on a municipal study, called the Informal Settlements Assessment 2018, was obtained from Council. By good fortune, starting back in 1993, shack counts from aerial photos are available for the city. This information supplemented the spatial and aspatial growth estimates given below.1

A list of technological innovations was also prepared in an attempt to date their introduction and diffusion into the urban system of Cape Town. The way in which the elements interconnect was noted throughout, as was their interplay with regional and global forces. However, a simple bookmarking of periods based on quantitative changes of, say, population or physical growth is inadequate. Problems expressed and actions taken by the people of the times, whether in the press, academia or political realms, would be the more convincing as markers of attitudinal changes, or non-change as the case may be. To generate a sense of the changes in outlook among urban actors, municipal minutes, press clips, historical writings and publications were also reviewed, giving a feel for what was regarded as the major urban problems of the day, and the best remedies. It also gave a sense of when public sentiment believed an urban crisis was at hand. A tie-back between quantitative changes, on the one hand, and perspective changes, on the other, was then undertaken to identify, characterise and date urban management practices for Cape Town over the past 250 years. Figure 1 gives a graphic overview of the six distinct urban management eras identified as a result.

The periods are held together by a 'common sense' or a consensual understanding of what is to be done in urban settlements. Consensus and discord are established through dialogue. Each period is characterised by a 'normal practice'. For purposes of this study, all information was arranged into 20-year intervals or increments. It was found that urban management doctrines endured for roughly 40 years, after which they remained part of the cognitive landscape. They were, however, replaced by a new, more modern outlook on city-making practices.

A footprint of the urban extent for several years starting in 1900 was generated. For footprints of the year 1900 and 1920, the author relied on various historic maps and written village profiles. The footprints for 1940, 1960, 1980 and 2000 relied on precise material, that being the Surveyor General's cadastral layer. A digital clip from the layer for each year was made: "the cadastral system has proved to be robust, even through a period of major change. The technical and institutional characteristics of the cadastral survey and land registration system (in South Africa) have survived radical social, political and economic transformation. Even though the legitimacy of the surveying and registration system was challenged during the transition from apartheid to democracy, the fundamental technical characteristics of the system remain unchanged" (Barry, 2004: 202). As a verification exercise, each footprint was corroborated against the 1:50 000 map sheets (Surveys & Mapping, 2019) and any historic aerial photographs (City of Cape Town Imagery, 2019) available close to the year.

Using the footprints, 'counts' of the number of erven added per 20-year increment were made, which also gave the number of hectares consumed by each increment. Using the land-use zoning map for Cape Town (City of Cape Town - Zoning, 2019), properties were divided into residential, commercial/retail, and industrial properties. Again, this gave a count, but also the hectares consumed per land use, for each growth increment. The tables and numbers given in the text below are drawn from this effort.

Included in 'residential' are neighbourhood amenities such as parks, schools, libraries and clinics. However, 'residential' excludes higher order uses such as bulk infrastructure installations, being treatment plants, solid waste precincts, airports, and the like. This implies that the quantities presented are 'lean'. Yet they remain significant, i.e. representative of the city as a whole. Major space-extensive land uses such as the peninsula mountain reserve and vast tracks of rural land have been excluded from the analysis, since they would distort the figures. Moreover, they are not part of the General Plans (or urban subdivisional) information set. An error margin of +/- 2% on all space estimates must be allowed for.

Since 1993, the municipality has kept a dataset of informal areas, tracking their growing circumference and recording shack numbers (City of Cape Town, 2017). These served as input data for estimates on this theme. Information for earlier periods relied on ad hoc research studies and municipal surveys over the years, as given in the references.

Deeds Office information shows when a parcel of land (an erf) was registered in an owner's name for the very first time, hence becoming 'real' in Cape Town's geography. General Plans (G-Ps), being the layout and subdivision plan, contain in their title the year in which they were approved by the Surveyor General, and these date back to the 1840s. A lag is present between the two dates, but their sequence is always similar: G-P dates must be earlier and, in a small percentage of cases, registration dates may never materialise. Combining the two sources and sequencing them allowed for a picture of physical growth phases to emerge. Since physical expansion is typically associated with significant moments of population or economic growth and change, the author turns to urban history to And a suitable starting point. 1900 was such a year, when the city's population surged. It also happened to be a year with good quantitative information. To prepare a long range growth profile, 20-year intervals were adopted. This gave a uniform time line and allows for increment comparison. Intriguingly, years 1920, 1940, 1960, and 1980 also coincided with change events, whether technological or political, as narrated below.

3. CAPE TOWN URBAN MANAGEMENT DOCTRINES

3.1 Urban management as self-help

Urban management is frequently associated purely with municipal (and state) administration (Baclija, 2011: 137). Used more broadly in this instance, it is taken to refer to the process of producing and operating urban regions, encompassing all those activities playing a role in building and maintaining urban environments. That would include acts performed or omitted by government departments, the private construction and finance sectors, as well as popular movements. Importantly, it would also extend to beliefs held by civil society, regulators and policymakers in respect of how and who ought to run urban areas. Producing urban environments takes place under rather specific conditions, with technology being one of the most powerful forces setting the tone for what is possible and what the spatial outcome will be. Factors such as the nature of the economy, that is, issuing the requisite finance and savings, must And a match in the market for, say, suburbanisation or high-density living, before they shall materialise.

Perhaps the earliest type of urban management practised at the Cape can be described as a form of corporate management, whereby the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) oversaw settlement growth, much like a company would 'own' and control its territory for purposes of resource protection and extraction.2People and livestock would be owned or employed, land allocated, and any construction commissioned or authorised. A prime instance of this attitude would be when the VOC allocated plots along the Liesbeek River in Rondebosch to several burgers and set them 'free' from company employ. As demand for fresh vegetables, fuel and especially meat increased, so the frontiers would be pushed out ever further (Sleigh, 2004: 129-245). The VOC accordingly directed the creation of Buiteposte as agricultural supply centres, which, in time, served to determine regional movement routes and nodes, from Swellendam to Gaanzekraal (Sleigh, 2004: 129-245). The majority view was that public well-being is closely associated with spending on military defences.

At the close of VOC-rule 150 years later, this attitude had changed completely (Laidler, 1952: 207). By 1800, an outlook that may be described as "policed self-help" prevailed. The Kaapse Vleck had grown into a settlement - Table Valley. It was fairly independent of the VOC by then and considerably bigger. A ward master census of 1801 placed the population of the peninsula at 16 531 (Laidler, 1952: 207).

Families would collect their water from the publicly supplied fountains; solid waste and night soil had to be dealt with privately; clearing paths in front of one's house or shop must be undertaken daily; fire-protection measures in houses were regulated, and so on. All this was enforced by the precinct "warders" (Picard, 1968: 31-38). Municipal functions centred on regulation and enforcement rather than on delivery.

Warders would fine and punish offenders (Picard, 1968: 31-38).

Policed self-help, which to date seemed the only obvious way to manage a settlement, continued. It started running into trouble in the early 1840s, a decade in which Table Valley experienced a spurt of population growth, fuelled, on the one hand, by the final emancipation of slaves in 1838 (Bank, 1991), many of whom gravitated to employment in the major centre of trade activity -the harbour. On the other hand, with the increased volume of agricultural produce from the wider district channelling through the port, a more permanent class of resident sought to settle in Table Valley (Bank, 1991).

The population increase triggered the first round of Cape Town's expansion. The sudden demand for new homes was seized by a section of the newly emerging commercial class. They were unwittingly aided by the 'normalising' economy. Under the VOC, which was de facto government, bank and an enterprise in its own right, the domestic economy was always going to be stunted.3 At the start of its second occupation, the British introduced a raft of favourable economic reforms, including currency reform, banking, and a shares/stock-trading facility, that being the Commercial Exchange in Adderley Street (Immelman, 1955). Making matters even more conducive, the colonial authorities injected considerable sums of cash into the fledgling but money-starved Cape economy by compensating slave owners in cash (Bank, 1991: 194-195).

For the first time, the preconditions were in place for urban growth to be driven by enterprise rather than by government. The settlement spread swiftly towards Signal Hill and Green Point, and thereafter in the direction of Tamboerskloof (Davies, 1965: 6-7). The fastest and poorest growth precinct was that of District 6 (then known as District 12, and Kanala Dorp) (Day & Son Lithographers, 1854). It accommodated some 4 000 individuals by 1850. It doubled in size in ten years but was built mostly without sewers, a direct water supply, or any measures regarding storm water. This laid the foundations for a first 'urban crisis'. In poorer areas such as District 6, solid waste would accumulate mid-block behind the rows of rental tenements lining the streets (Day & Son Lithographers, 1854). The problem was not confined to District 6. Not since the early 1800s, under architect Louis Thibault, was much appetite for civic improvement shown (De Puyfontaine, 1972: 27-32). Indeed, until 1840, there was no meaningful municipality. Once one was founded, it was taken up with arguments over who should enforce street-cleaning regulations -the police or the municipal warders.

Urban management, as policed self-help, dragged on through the decades, but it was increasingly out of step with the changed circumstances. By the mid-1870s, the problem of filth and untidiness at Table Valley had become the dominant topic in municipal politics. Waste from Ashing operations remained on the beaches; sewerage poured down into the sea along mostly open channels; manufacturing waste from tanning, slaughtering or cooking were all taken, or washed, down to the tides to clear up (Bradlow, 1976: 1). Artisans would practise their skills and production at home, including from their small, crowded tenements, in which candle-making, fish-cleaning, sewing, baking and much else took place.

Visitors to the colony would all pass through the port that was thus exposed to the unsavoury condition of town. Comments such as "a somewhat ragged place", "city of slums" and "city of stinks" were frequently noted in the press (Bickford-Smith, 1983: 194-196).

The first salvo for a major reform was launched by a group of wealthy merchants. They generally lived out of town in the salubrious peninsula, yet were confronted by their customers' reaction. They pressed for reforms in favour of civic improvements. Their solution was to afford the municipality much greater lending powers, to tax property owners (imposing in other ways on landlords, too) and to encourage it to undertake huge new public works (Bickford-Smith, 1983: 198-199).

In opposition to merchants, an organised and influential class of landlords had also formed. They tended to be from and allied to the local commercial business establishment (Bickford-Smith, 1983: 196; Dommisse, 2011: 3442). They predictably rebuffed the merchant Reformers. Reading the press of the day explains that the debate crystallised into two broad factions: those in favour of "reform" and those labelled by Reformers as the "Dirty Party" (Dommisse, 2011: 34-42). Ultimately, the latter did take control of council in early 1880, but by then landlords were also versed in the challenges facing town. The "Dirty Party" would henceforth regard itself as the "Clean Party" (Dommisse, 2011: 34-42).

3.2. Urban management as public works

For the next four decades and well into the 1910s, considerable improvements to Cape Town would be made, particularly with reference to utility amenities. Several water-supply reservoirs were built; pipes laid; streets and rail stations lit; open sewers covered (water-borne in 1895); main thoroughfares hardened the harbour extended several times, and water reticulation introduced (Palser, 1998: 11-15). In fact, in the 1890s, the municipal corporation even generated its first electricity from the Molteno Reservoir (Palser, 1998: 11-15). Benefits from these enhancements were far from evenly spread across town, of course, with poorer housing areas receiving less of the spend. Yet the era wherein the municipality took on functions such as central water management, solid-waste collections, controlled abattoirs, traffic management, and public transport, among other things, had begun. A new 'normal practice' in urban management had set in. As the new century opened, the civic-spirited side of the municipal system had improved conditions significantly, so much so that it had become the norm to think of it as being a local authority's raison d'etre. With that, the new view of urban management as large-scale public works, empowered local authorities, and service provision had been firmly embedded in public consciousness.4

Yet no sooner had the new method of urban management found its feet and the ground beneath would shift. Another spike in population growth occurred in roughly 1900 (Van Heyningen, 1984: 64). Over and above any natural increases, growth at this time was supplemented by an influx of non-returning British soldiers active during the Boer War (Van Heyningen, 1984: 64). Moreover, uitlander refugees from the Transvaal moved south, immigrants from eastern Europe's pogroms arrived, and farm labourers from a depressed agricultural sector at the time all added to the increase (Van Heyningen, 1984: 64). In a matter of ten years, the Peninsula's population doubled, which would have had the knock-on effect of creating a huge demand for accommodation and employment again.

The earliest signs of overcrowding were felt most acutely on lower priced houses and lodgings. Demand pushed rentals up significantly; landlordism as a business had exhausted itself (Warren, 1988: 44). The formation of slums and dreadful living conditions drew the authorities' ire. Instinctively, they pressed proprietors into making costly improvements, while tenants were increasingly reluctant or unable to pay. Unlike with civic improvements, however, urban management was now being drawn into the private realm - a field in which they remained inexperienced and insecure.

The private sector was more responsive to the new demand. A new commercial undertaking emerged, one based on home ownership and on loan finance, 'land subdivision'. Starting in the mid-1890s, a large-scale subdivision of open terrain began.5

The South Africa Review routinely carried advertisements offering "building-lots" for sale (erf/plot) or auction, often with maps (South Africa Review, 1901: 8; 1902: 9, 22). These were usually outside the jurisdiction of existing municipalities,6but not out of reach either. Prominent, but not limited to, were locations such as Milnerton, Goodwood, Parow, Diep River and even Sea Point. Land subdivision opened the said areas up for future development, by simply imposing a grid on the landscape and demarcating plots of land. Hardly any attention was paid to layout planning or internal servicing (Rosenthal, 1980b: 28). Land was commodified and this new 'business' was still distinct from the home-building process. Viewed jointly, the two processes amounted to a significant spatial expansion of urban Cape Town (Young, 1998: 18). The subdivision of land constituted the first wave of suburbanisation into the Peninsula. By 1925, it had tripled the urban footprint of the city with knock-on effects for water supply and sewerage services.

The subdivision of land was capital intensive. Much of it came from the Witwatersrand via the Randlords (Yudelman, 1984: 52). Mining, it was thought, was coming to a close, since, by 1900, mines were getting deeper, requiring specialist skills and yet yielding less ore (Yudelman, 1984: 52). 'Gentlemen estates' on the southern Peninsula and farms on 'the downs' were thus bought up as investments. Gradually, the process of carving them up for settlement gained traction.

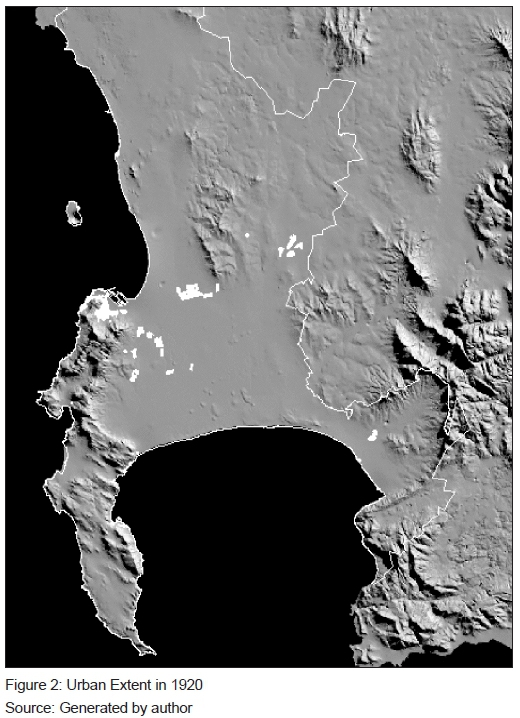

The subdivision of land did follow a spatial logic. Greater Cape Town's trunk routes, rails and roads had by and large been inscribed on its geography. Since the private motor car had not become a domestic convenience yet, access to public transport lines was essential for the sale of new residential plots. Advertisements of the time (in the South Africa Review) all proclaim: "within easy walking distance to the station", "generously sized lots", and "suitable for vegetable gardening". This phase of urban expansion in Cape Town remained unguided by any spatial framework, nor was it centrally controlled. Territories being opened up took their cue firmly from pre-existing networks: stations, roads and water mains (see Figure 2).

From the outset, administrative deficiencies in this process were recorded. The Cape Colony's "Mayors Congresses" repeatedly raised the problem of what it termed "town lands", being the complications caused by "estate developments" or "vendors of townships". Land was being surveyed without notifying the municipality, even when falling inside its own jurisdiction. This made it difficult to connect to existing service networks, to collect property taxes, as there were no prior valuations, or to anticipate the volumes and range of municipal servicing being generated. Furthermore, connecting two new "estates" properly, even when adjoining each other, proved tricky. A new mechanism to ensure co-ordination and regulation of urban development was urgently needed. The term "proper town planning" kept surfacing (Rosenthal, 1957: 75).

Stemming largely from the United Kingdom, Cape Town's councillors and mayors drew heavily on exposure to solutions discussed abroad. Urban management would henceforth require a leading lamp. It was hoped that things would get better if directed by longrange master plans. Meanwhile, it was doctrine-as-usual, while living conditions in town steadily worsened. The Housing Survey of 1932 by the Medical Officer of Health served before council. It looked into the "central portions of Cape Town", being wards 2 and 6, and recommended the "eradication of slums on a systematic basis" and that a development "scheme should be adopted" (Cape Town Municipality, 1933: 105).

Designating the precincts around Van de Leur and Caledon streets as "slum", "overcrowded" or "unsanitary" lead logically to the idea that municipalities should do more than co-ordinate developments. They had to get directly involved in forestalling urban decline. In this instance, councillors adopted slogans, solutions and attitudes derived from the United Kingdom, which generally favoured turning their backs on squalid inner parts of town, preferring to have them cleared and relocated to properly planned areas, where "layouts allowed for light, air and space, and with overcrowding being overcome" (Rosenthal, 1957: 75).

After reading the dates from the General Plan approval dates, the number-of-units from the erven created on them, and the mention of these areas in Council debates, the author found that the earliest housing scheme was by the Mowbray Board, which built a few houses along Raapenberg Road in 1903. This was followed by Cape Town's Mill Street project in 1904. Like larger companies were doing at the time, these were built for their own lower salaried staff. But it did signal Council's entry into real-estate development.

In 1916, Council approved an internal 10-year fund to allow for the erection of "wood and iron" dwellings, to be removed on 6 months' notice7. Emergency shelter works such as the "Assisted Housing Program" (1919) and the "Houses in Brick" (1925) were in response to very local crises. Retreat, Kensington Estate, Brooklyn, Crawford and Claremont saw the building of such structures. In the coming years, this would be expanded so much so that the impression was cemented in popular thinking that municipalities are responsible welfare housing (Cape Town Municipality, 1923: 7).

The first phase of Maitland Garden Village (138 units) was begun in 1918, after having been a refuge for the ill during the influenza of that year. Relocating out of town was but an echo of what private developers had been doing for some time. A second scheme was begun in Roeland Street, Vredehoek, in 1921 (48 units). Both came with elaborate urban designs.

The prevailing doctrine of public works was no longer up to the task of dealing with such challenges. In the early 1920s, the majority of commentators viewed the ideal of 'town planning' favourably (Rosenthal, 1957), associating it with technological revolutions such as railroads or electricity, both of which came a generation earlier and had a massive impact on Cape Town's form. Town planning instilled optimism, confidence and enthusiasm. With it too came strains of utopia and ambition.

3.3 Urban management as town planning

By the early 1920s, the subdivision process had largely run its course. It had flooded the market with plots, which was compounded by the post-war depression. Inspecting the historical cadastra of Cape Town illustrates that the large tracts of land subdivided in the 1900s, especially in locations such as Kraaifontein, Milnerton or Elsies River, had not been taken up. When economic recovery did come later in the decade, emphasis fell on home-building. Underpinning the renewed momentum was town planning and a growing population.

The private sector revisited its grid layouts with more imagination and offered direct consumer support.

Milnerton Estates appointed a qualified town planner, A.J.L. Thompson, to make the 20-year-old plans more appealing. He offered model building plans, reoriented vistas towards the seaside and proposed the planting of trees along all roads (Rosenthal, 1980a: 56). Pinelands Estate, which laid its foundation stone in 1919, was modelled on the British "Garden City" movement. The Citizens Housing League produced elaborate layouts in their Good Hope Model Village schemes in Brooklyn and Ruiterwacht. Furthermore, landholding companies such as the Elsies River Land & Estate Syndicate (Pty) or the Plattekloof Estate & Investment Company (Pty) took advantage of a now well-capitalised building society system (Boleat, 1985: 130) to provide not only "lots in the field", but also serviced erven and building finance. This appealed to both homeowners and property investors. Consequently, Goodwood grew phenomenally in the early 1940s. Its population rose from 6 800 people in 1939 to 28 800 in 1945, doubling again to 60 000 by 1950, with the majority of growth being Coloured families. "Estate development" had become the vehicle of choice for township establishment and building (Rosenthal, 1980b: 17).

A section of the architectural fraternity also took a keen interest in the 'new field' of town planning. In 1938, the Architectural Society convened a Congress on the Science of Town Planning, using Cape Town's Foreshore reclamation scheme as a case study, convened at Eskom House in Johannesburg. Psychologists and sociologists also weighed in on this exciting subject (Architectural Students Society, 1938). Such debates influenced public sector housing schemes such as Alicedale (1940), which sought to "create community" through spatial designs, or Q-Town (1944), with its high-rise flats in wide open landscape.

The impact of the 'town planning ideal' on the role of the state was fundamentally legislative. As early as the 1910s, Dr Charles Porter of Johannesburg, a medical doctor, was called upon to impose some order on the unruly and fast-growing town. His zeal for town planning was rooted in his desire for hygiene, order and de-densification. His preferred means of municipal legislation was the attitude of control.

The Union Government deemed it more appropriate for provincial governments to manage township establishment. Transvaal introduced its Townships & Town Planning Ordinance in 1931, while the Cape followed with its Ordinance in 1933. Both called on municipalities to draft 'town planning schemes', being frameworks to mitigate slum formation and urban ill-health. Thus began a long tradition of classifying and categorising building activity. Administrative procedure, land-use rights and building control became fields in their own right. It became ever more elaborate and costly until 1960. Floyd (1960: 104-135) gives a detailed account of how this all functioned without explicitly venturing to suggest whether initial urban problems calling for the adoption of town planning had been ameliorated by planning legislation or not.

While ideas from Britain of higher density rental tenements in town such as at Wells Square (1933) and Bloemhof Flats (1938) in the City Bowl were introduced, they remained marginal to the greater challenge brought on by a renewed burst of growth starting in roughly 1940 (Nattrass, 1990). As a useful milestone, this was when, for the first time, manufacturing contributed more to the national gross domestic product than the agricultural or mining sectors (Wilkinson, 1993: 241). Making that more impressive is that mining output had grown from £45 million in 1930 to £118 million in 1940 (Samuels, 1960: 241). The restructuring economy found spatial expression in the building of industrial estates such as Epping 1 (1943) in the Cape, thus attracting unskilled labourers (Nattrass, 1990: 107). The Peninsula's African population rose dramatically in the five-year period from 16 500 to 60 000. That swelled squatter settlements of Windemere, Vrygrond, Hardevlei, Retreat and Philippi. Squatting would, in turn, redirect policy attention to emergency relief, that is away from higher density housing.

The 'native township' of Langa was started in 1925 - the first of several to come. Funded from the new revenue account of the Native Urban Areas Act (1923), it stands as possibly the earliest pure race-based scheme in the Cape. Other schemes such as Boundary Road in Rugby (1942) or CAFDA Village in Retreat (1952) were begun with poverty in mind, that is, until national funding was made conditional upon them being classified in terms of the Group Areas Act (South Africa, 1950) for Whites and Coloureds, respectively. Reluctantly, the City Council acceded and so starts the notion of developing for specified race groups. By the late 1960s, it was received as 'normal', making it an integral aspect of an urban management doctrine. Working back, older areas were to be proclaimed and "cleaned" (Western, 2000) as part of this attitude, which added artificially to a housing shortage among, especially, the Coloured community. Making matters worse, local government itself was being racialised, with councillors of colour being pushed out and their voices going unheard. Private sector development was self-consciously building for Whites only. It was a significant departure in attitude from the days when the Diep River or Goodwood plots were first put out to sale in the 1920s.

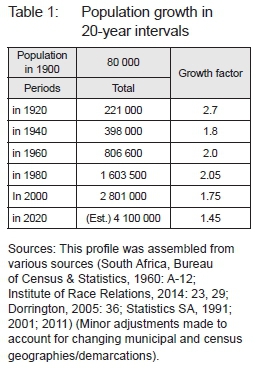

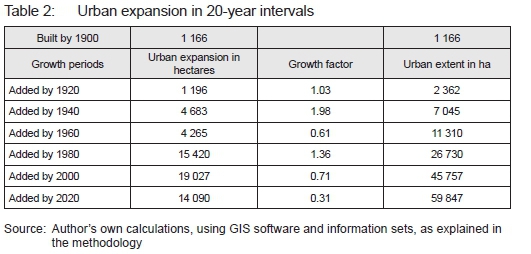

Public sector housing projects grew in size, seeking economies of scale and speed by delivering not 100 or 200 units at a time, but several hundred such as in Hazendal (1956) and Bridgetown (1952). Taken together with other schemes such as Heideveld, Athlone and Lotus River, not to mention schemes on the Peninsula by the Divisional Council in Gassy Park and Lavender Hill, some 6 000 ha of urban landscape was added to Cape Town between 1920 and 1960 via public sector initiative (see Table 2). Town planning had, of course, been commandeered to "group-area" cities from its beginnings (Parnell, 1993: 97). By the 1960s, its involvement had deeply eroded its reputation, notwithstanding the many critics of the system within the fraternity.

Perhaps because the adoption of planning was to deal with uncoordinated development and urban health challenges of the time, it completely missed the other technological innovation of the early 1920s - the automobile. Often referred to as the 'revolution in transport', it would leave a lasting and massive impression on physical Cape Town. Once cars made themselves felt as problems, urban management sought to accommodate them. In 1929, the Council, through the office of the City Engineer, Mr D E Lloyd-Davies, and drawing on his experience in public works, would lobby for a national road system, proposing to start with the building of freeways in metropolitan areas (Floor, 1984: 2). The deep-seated belief was that "roads build wealth; wealth does not build roads". Until the mid-1930s, government still viewed the rail system as the future of transport. It ultimately accepted a financing obligation in respect of roads, especially of the intercity kind.

Cape Town of the 1950s was gripped by freeway planning - their civil engineering and routing aspects, in particular. The negligeable attention paid to their relationship with communities or aesthetic impact on the landscape was taken as positive. Freeway construction characterised Cape Town of the 1960s and 1970s (Floor, 1984). Ever more capacious roads were assumed to be a best response to our high levels of car ownership - even by American standards. But the dissenting voices grew louder. In 1961, the British town planner, Sir William Holford (1961: 36), would suggest that the devastation wrought on American and European cities by the motor car could still be prevented in Cape Town, where its physical heritage was already under threat. He noted that it would require thinking as radical as the transport revolution itself was.

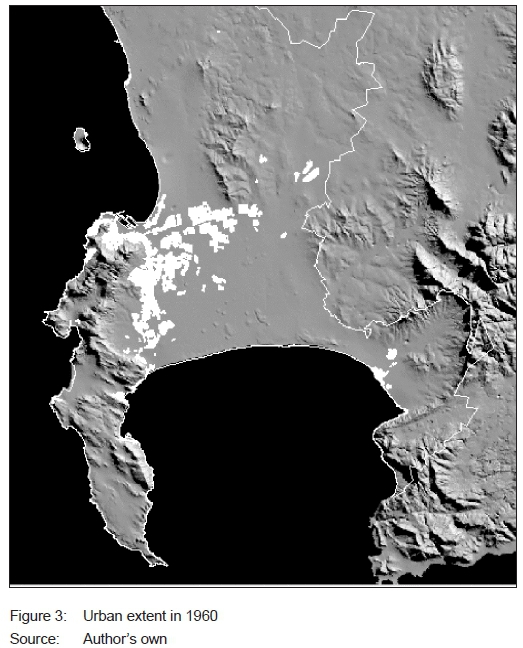

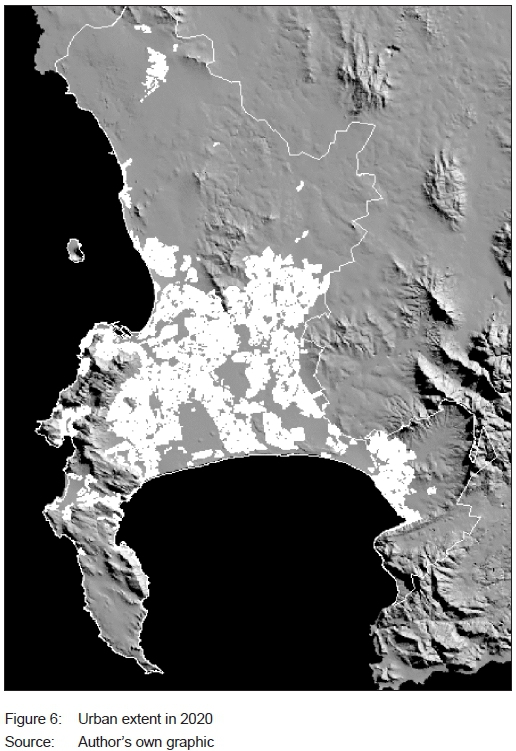

As planning became publicly contested, despondency about its virtue set in. At a theoretical level, some academics (Architectural Students Society, 1938) proposed paying attention to public sector decision processes rather than to "master plans" as an effective route to improving cities (Faludi, 1973). At a practical level, urban growth can be characterised as having become explosive as of the early 1960s (compare Figures 3 and 6). Construction technologies changed significantly, allowing for much higher buildings and off-site assembly methods (Hartdegen, 1981: 267). Spatially, the country's metropolitan areas were already on the verge of being too spread out to operate without transport subsidies, since 1957 saw the introduction of a commuter bus subsidy.

Infrastructure schemes by the public sector took on regional dimensions such as the Voëlvlei and Wemmershoek (with its hydroelectric component) dams. Within the metropolitan area, four major freeways would be built over the next 30 years, as well as a new 180mW power station at Athlone (Palser, 1998). In fact, regional planning was widely punted as more appropriate to the impending 'population explosion' as then anticipated worldwide. Planning should concentrate on the region rather than on the town. By the 1960s, the region as object of planning had penetrated every department of the state - national censuses were premised on both planning regions and planning units.

3.4 Urban management as upscaling

The year 1960 again triggered profound political and economic changes in the country. No aspect of society remained untouched by the protests in Sharpeville and Langa in March 1960 (Lodge, 2011). They capped a decade of rising urban protest and repression. It would not leave urban management unaltered. Coloured voters were removed from the voters' roll in the Cape. Multiracial liberal parties were outlawed, and their leaders went into exile or "underground" (Lodge, 2011). Economic ties with the Commonwealth were severed and the Rand was introduced as currency (Lodge, 2011). Electricity was of the cheapest in the world; the Industrial Development Corporation's initiatives to foster manufacturing in the 1940s had reached maturity; an abundant variety of natural resources was available. In combination, these factors set the scene for what would become a decade of unequalled annual growth, at a rate of 6%. The situation caused deep pessimism and optimism in equal measure. Urban management adopted grander and altogether more expensive undertakings. Without doubt, between 1960 and 2000, Cape Town would experience its biggest physical expansion ever. The city grew from 11 300 ha to 45 700 ha of urban space, a stellar enlargement! (see Table 2).

Inferred in the context of the Retreat master plan, the public sector contributed significantly to this expansion. By moving away from undertaking single projects in favour of rolling out multiyear housing programmes, what began as a welfare endeavour can, in hindsight, be viewed more properly as an urban building event. This new generation of programmes would consume land and public funds at an increasingly voracious pace. It was taken for granted that urban problems of public health and housing could be conclusively "solved" only if done with the right ambition and more comprehensively. Still, the traits of population and development control remained firmly in place throughout. They would only let up in the 1990s. As was the case with water, sewerage, road or electricity schemes, homelessness would henceforth be addressed on a massive scale and with a positivist attitude.

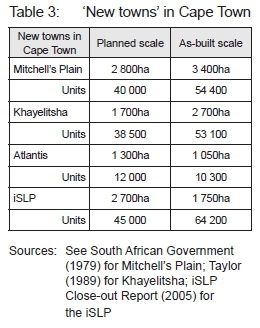

This 'reset' may best be traced to a moment when the various local initiatives in Retreat were combined and reframed as a long-range scheme. Drawing on the Municipal Minutes of 1954: "The [Retreat] Master Plan ... should serve as a ... housing programme for the coloured population for the next 10 years in a systematic and scientific attempt to solve this acute problem" (Cape Town Municipality, 1954: 104). The shortage was estimated to be 20 000 houses and a delivery rate would be 1 500 per year. As noted from the cadastras and municipal minutes of the time, a few more programmes were subsequently started, notably Bonteheuwel and Kalksteenfontein, but this did not solve homelessness, but left a lasting imprint on city structure. They also generated the self-confidence required to move matters up a notch, to even grander initiatives in future - completely new towns (see Table 3).

In 1972, Cape Town Municipality (1972) contemplated building a 'new town' on the Cape Flats. The idea was to shed the stigma of 'low cost' associated with prevailing public sector building efforts. Mitchell's Plain (1975-19878), or 'Good Hope' as was first mooted, was a proposal to build 40 000 houses along with all ancillary social facilities, mortgage houses and enough streetscape for everyone's motor car (Huchzermeyer, 1995). Shortly thereafter, the Divisional Council began its 'new town' on a farm up the West Coast. Atlantis (1978-1991) came with its own industrial estate, visible on maps and old photos. This was followed by an announcement of yet another one on the Cape Flats, this time for Africans. Khayelitsha (1984-1996) was announced by government in 1983 just as the National Party was facing its crisis over separate development (Dewar & Watson, 1984: 1). Violent flare-ups would characterise the flats between pro- and anti-government factions, and most acutely in squatter settlements such as Crossroads. Government-driven projects became highly politicised.

Despite all the spending, squatter settlements on the Peninsula continued to swell. Maintaining such levels of spend on these ventures became highly politicised and financially onerous. Economically, the 1980s were the antithesis of the 1960s, with low growth rates and a record national debt being reached by 1989 (Abedian & Standish, 1992: 13). As it was risky to withdraw from housing delivery at that time, a new product had to be considered. In the early 1990s, the old Cape Province announced its integrated Serviced Land Project (iSLP, 2005). The purpose was essentially to "improve the land" with municipal services before being squatted upon. The notion of supplying serviced sites at scale was endorsed and the new town idea began to fade. The one aspect of the idea, which never succeeded, was the town centre. In each case, land set aside for a 'CBD' remained vacant the longest. The iSLP (1992-2005) serviced land around Nyanga and Crossroads, eventually also incorporating Delft, relocating some 65 000 shack families to plots over a 15-year span. A significant number of plots, although not all, were supplied with a rudimentary house on it after the Housing Act (107 of 1997) came into effect - colloquially, these became known as RDP houses.

Collectively, 'new town' programmes city opened its rural areas up widely. They contributed significantly to its spread (see Table 3). The Cape Flats, which in the 1840s could not be traversed by wagons for the sandy and shifting ground conditions, had now been covered with concrete and bitumen. Natural water courses, which fed erstwhile market gardens, were disappearing from obvious view, much like the Platteklip stream. Much of the Platteklip Stream that watered the Company Gardens and Castle of the 17th century had disappeared. Strandveld Fynbos, a unique dune-flora landscape, had been consumed by building (City of Cape Town, 2012a).

In all, by 2000, just shy of 10 000 ha of urban development had been added to Cape Town's footprint through state initiative - almost exclusively south of the N2 freeway. In that time, the private real-estate sector turned its attention to rolling out suburban residential townships, ever bigger shopping centres, and industrial estates. These would all be built with the private automobile firmly in mind, and perforce, for the White section of society. Both private and public developments as of 1960 could and did disregard historic movement routes. Rail extensions were added as part of all new towns, and the freeways opened up most of the historic farms on the Peninsula. Organic urban growth from before the motor car had given way to the programmatic growth of the modern era. By the mid-1980s, the combination of spread and mobility gave the city a new commercial sector - the taxi business (Khosa, 1991: 310).

The private sector's contribution to building the city was massive. From 1960 to 2000, it added close to 12 000 ha of new urban fabric.9 Most of it was targeted at the White middle class, although significant portions went to Coloured buyers in Eersteriver, Brackenfell and Kuilsriver. Visible on photos, the major axis of expansion was north-east from Bellville and north-west from Somerset West.

Private sector ambition and scale is best observed in the building of shopping centres. Their number and size rose rapidly in the early 1970s and, as late as 1985, Cape Town's CBD (or the City Bowl) could still claim retail primacy. Thereafter, matters would change, as 'malls' of competitive size sprang up in locations such as Bellville and Claremont. For the first time, the question of where the core of Cape Town lay was foggy. Starting in 1989, the redevelopment of the V&A Waterfront did much to rescue the CBD commercially, but in its own way also demonstrated the appeal to size and grandiosity. The race to secure market share propelled the shopping centre process. If one could no longer draw customers from the suburbs, then move out! By the early 2000s, a distinct and reasonable smooth hierarchy of shopping complexes had crystallised, topped perhaps by Century City in ostentation. Centres were distributed across the metropolitan economy, yet areas built by the public sector remained largely outside this process, although not absolutely so. They remained strongly attached to informal trade. Main-road shopping strips were in decline everywhere to be replaced by neighbourhood shopping centres.

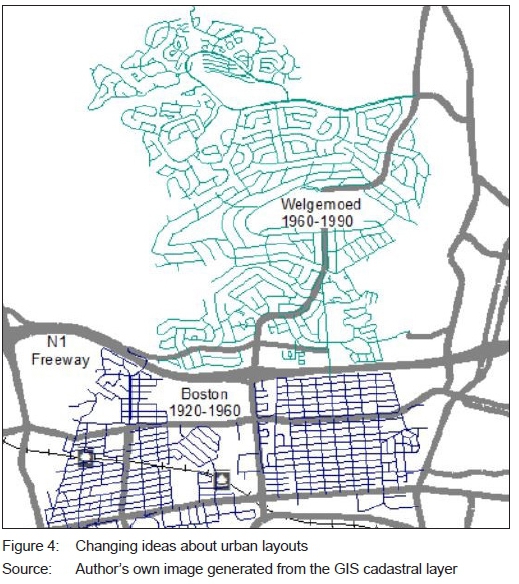

Inferred from layouts and old photos, the residential 'estate development' had also taken on an adjusted form -the erstwhile gridiron had fallen out of favour to be replaced by experimental layouts. Curvilinear roads and cul-de-sacs as key features were introduced, while elevated landscapes with views were made desirable. Motives included slowing traffic, engendering community, and making movement visually more appealing (see Figure 3).

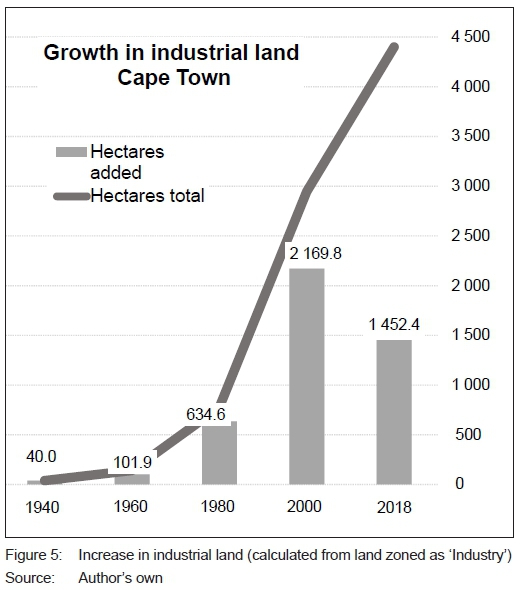

Industrial estates entered urban management consciousness in the early 1950s (see Figure 4). As the spatial manifestation of the burgeoning manufacturing sector, they were viewed as an engine for urban prosperity. With 'Epping 1', the public sector got involved in making land available for manufacturing, twinning it with rail as mover of goods (Cape Town Municipality, 1947: 10). A decade later, it will have drawn workers and placed municipalities on a policy collision course with the state, which desired industrial decentralisation, hence Atlantis. This new phenomenon began the debate about cities competing. Local government was now looking beyond its jurisdiction.

Smaller manufacturing centres had always existed on the outskirts of towns, from Paarden Eiland, which was linked to the City Bowl, to Parow Industria. Their location of choice was always on the very edge of town on account of their nuisance and risk factor. Once embedded in urban management as an essential component of any city, their establishment grew in scale and tempo (see Figure 5). Industrial estates would become not only a tangible force for urban expansion, but also magnets for investment and urban development in their direction.

3.5. Urban management as transformation

By the late 1990s, scale had given way to a new dominant ideal -transformation. Subsumed in that idea are questions of, among others, reconstruction, redress, reform, and restructuring.10 The decade is remembered as the period of democratisation, but it should also be viewed as a period of great fluidity and uncertainty, especially at municipal level. In the realms of urban management, attitudes were to change fundamentally once again. Urban critics of an earlier generation moved into positions of influence - the city system was to be integrated rather than segregated, densified rather than spread, and governance was to be participative rather than technicist (McLagan & Nel, 1997). The results of these shifts in attitude have yielded a mixed bag thus far, as picked up below.

Centralisation, standardisation and informalisation are key aspects of the new transformation era, and are germane to urban management.

The democratic Constitution of the Republic of South Africa came into effect in 1996. Only Ave years later, the municipal system would settle into final form. Initial attempts to create six autonomous municipalities for the metropolitan area failed when, in 2001, all 3 million residents fell under a single council of 210 representatives (Unicity Commission, 2000). Once in place, the ex-administrations, very diverse in terms of skill and sophistication, would be merged into one Unicity. Uniform practices and procedures across the diverse range of historic areas - big and small; Black and White; rich and poor - would follow. Emblematic of said standardisation is the introduction of an overriding Land Use Management System, giving an Integrated Zoning Scheme and single set of Scheme Regulations (South Africa, 2012: 8-14). Design of the system coincided with maturing of digital technology and has, accordingly, been built on the premise that processing of development applications will in future be done on-line. This holds the prospect of creating the new cleavage in the city, the one between formal and informal procedures.

Informal settlement is not new to Cape Town. It was a complaint as early as the 1920s when, in Fish Hoek, ex-rail construction workers built shelters in the dunes. In the 1940s, a renewed influx of particularly African migrants was instrumental in starting the Nyanga-Gugulethu scheme (Cape Town Municipality, 1955: 9). Informal shelters, variously referred to as 'hutments', 'pondocks' or, nowadays, 'shacks' increased in number year-on-year and provided much of the impetus for new state housing efforts. A second influx to Cape Town took place in the 1990s, often ascribed to a decline of Eastern Cape homelands. The number of shacks increased from 28 400 in 1993 to 72 300 in 1998 and from 50 recognised settlements to 64 (Kuhn, 1999). In 2017, the number stood at approximately 152 000 across 280 locations (City of Cape Town, 2017). The variation in type and size of settlement has since broadened significantly, while the level of utility service received by each also differs markedly.

However, a new attitude towards such settlements became apparent post-2000. Their value to those who lived in and built them was admitted. Prevailing wisdom was tha spontaneous settlements were not to be demolished or relocated, except in cases of danger to occupants. The permissive attitude led to their proliferation. They thus became a factor in urban management itself - no longer as a problem of urban welfare, but as a force in directly shaping the evolving structure and nature of physical Cape Town. Informality had become a city-building process in its own right, alongside the traditional state development schemes and private real-estate investment. Under this new doctrine, the public sector was forced into a position whereby it is always on the back-foot, trying to service and formalise new settlements as and where they arose This weakened the role of official city planning significantly. A return to organic growth was in progress.

One way of formalising the settlements remained the continued building of new housing stock (City of Cape Town, 2012b). Of the 43 000 state-funded houses built in Cape Town between 1999 and 2004, 39 000 went to families living in shacks in informal areas, only to be re-occupied by others. A second way of formalising settlement was to relax building control regulations over deemed 'illegal' building. There have been attempts to accommodate informality in the town planning schemes, ironic though it may sound. In existing suburbs, building second and third dwellings has been allowed as a matter of primary right as another way of minimising the pressures for new informal area formation.

Informal settlements contributed hardly anything to urban spread. As far as absolute expansion goes, and in proportional terms, urban growth has slowed considerably since 2000. Only 14 000 ha had been added by 2020 to the base of 45 700 ha (see Table 2). But the contribution made by new informal areas was minimal on account of being positioned in and around existing urban fabric rather than behind dunes in far-flung locations. Currently, 2 100 ha of Cape Town's urban space is informal (City of Cape Town, 2017).

Public-sector programmes of earlier decades had also changed. Projects were back on the agenda, and most of these were mop-up operations within legacy programmes, thereby not contributing a great deal to urban spread either. Without new town ideals as part of their conception, however, state development schemes had lost some crucial aspects. Sociological debates about what house is fit for what kind of family had been neglected in favour of output score-keeping - much in keeping with the information age. More importantly, they remained tethered to the notion of delivering only to the poorest families, who tended to be African. Since project size was championed, large areas of socio-economic disadvantage have been produced. State policy since 1996, primarily through its funding of housing, has dramatically intensified segregation in Cape Town (Tomlinson, 1997). On the other hand, market processes of the property sector have had palpable desegregative effects on many older suburbs and on central shopping areas.

The private sector directed its attention to the market, which expanded gradually, in that buyers from all population groups were permitted to purchase and own property. But the product delivered, in general, had also changed. By 2020, virtually all new residential and business parks were enclosed as security estates.11 A premium of as much as 100% could be charged inside a gated estate compared to one outside. The trend is down to the withdrawal of effective urban policing, so buyers are pricing safety and security into their purchase of fixed property.

As the city spread, now covering most of the greater downs/flats territory, land has become more scarce and valuable. This led to a further change in the private sector product - higher densities. Unit densities (du/ha) being delivered have gone up from a metro average 7.7du/ha in the 1980s to 9.7du/ha at present in the residential sector. The combination of scale, security and density are best exemplified in the Sitari development, west of Strand, where the largest enclosed estate is taking shape - over 4 000 homes. Included are shopping, schooling and medical facilities (Sitari, 2020). Whereas higher density residential developments have historically coincided with high amenity and property values, the new format is an attempt to include these in the precinct itself. Traditional location cues are being abandoned, making "reading" Cape Town's urban morphology less intuitive.

3.6. Urban management in the future

Two other factors that have reshaped the urban management doctrine in this century so far and that are bound to do so much more penetratingly in years to come are globalisation and Information and Communications Technology (ICT). While much debated over the past 50 years, globalisation will take on a much more intensive form with the arrival of cyber currency and as peer-to-peer payment modes sink in (Pejic, 2019: 12-20). Funding of fixed investment (or its withdrawal) shall be instant and independent of macro-economies. Public sector schemes shall remain linked to state funding though, just when national governments and their economies are diluted. The informal sector is bound to proceed unresourced. Urban management shall assume a split personality. Early attempts at predicting ICT's likely effect on urban form and management have been made, specifically working out the logical result of the "death of distance" (Hall, 1998: 943-989). Sadly, this debate has subdued since, possibly because attention has moved to a preoccupation with data, "smart cities" and "applications". As yet, none of them are tied back to morphology. Currently, in 2020, we have another moment of crisis. It pivots around three aspects, namely safety and security; a failing state, which implicates urban planning, and a Peninsula hemmed in by mountains, which shall impose considerable limits on its further spread.

4. CONCLUSION

In the case of Cape Town, the relative weight of informal to formal development is bound to change. Considering present mainstream attitudes in urban management, the informal sector shall become more pronounced. Whether it will deliver a more liveable or sustainable city is an open discussion. Looking at the figures, it is clear that tension is bound to rise significantly over the next two decades. Since 2000, the population has increased by a factor of 1.46, while urban expansion has only been 1.3 (compare growth factors in Tables 1 and 2). It may be read as a victory for urban compaction, but that does not account for the life and livelihood it produces. Viewed differently, Cape Town's population has increased by nearly as much since 2000 as it had people in 1980. Urban management shall no doubt adapt and accommodate the new reality.

Having reviewed the shifting doctrine of urban management in Cape Town over the years, it can be said to be compounding. New outlooks, practices and functions are taken on board as circumstances in respect of population, technology and economics demand it. Earlier outlooks are not wholly discarded, but they become adjusted and enriched. At times, they take on a life of their own (e.g. town planning). Earlier practices are normally continued, not as a headline item (e.g. public works or housing delivery). These sink imperceptibly into the background as new lead ideas arise to confront and communicate what society understands to be the most pressing challenge of the moment.

While the urban management doctrine has an effect on the type and form of city produced, it is reciprocally possible to read the prevailing attitudes from the historic form of that city. In the case of Cape Town, the six doctrines identified, namely corporate management, self-help, public works, town planning, upscaling, and transformation dominated for a period of roughly 40 years each. In the middle of each term, a crisis would arise, changing the cognitive rules whereby urban management proceeds.

REFERENCES

ABEDIAN, I. & STANDISH, B. 1992. The South African economy: An historical overview. In: Abedian, I. & Standish, B. (Eds). Economic growth in South Africa: Selected Policy Issues. Cape Town: Oxford University Press, pp. 1-24. [ Links ]

ARCHITECTURAL STUDENTS SOCIETY. 1938. Town Planning 1938. South African Architectural Record. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

BACLIJA, I. 2011. Urban management in a European context. Urbani Izziv, 22(2), pp. 137-146. https://doi.org/10.5379/urbani-izziv-en-2011-22-02-006 [ Links ]

BANK, A. 1991. Decline of urban slavery at the Cape: 1806 to 1843. Cape Town: Centre for African Studies, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

BARRY, M. 2004. Official coordinates, lawfully established monuments and South African cadastral surveys. Geomatica, 58(4), pp. 202-205. [ Links ]

BICKFORD-SMITH, V. 1983. Keeping your own council: The struggle between homeowners and merchants for control of the municipal council. In: Saunders, C., Phillips, H. & Van Heyningen, E. (eds). Studies in the history of Cape Town, vol. 5. Cape Town: Centre for African Studies, University of Cape Town, pp.188-208. [ Links ]

BOLEAT, M. 1985. National housing finance systems - A comparative study. London: Croom Helm, pp. 130-144. [ Links ]

BRADLOW, E. 1976. Cape Town 100 years ago. A supplement to the Cape Times Newspaper. [ Links ]

CAPE TOWN MUNICIPALITY. 1923. Municipal Minutes, March, p. 7. [ Links ]

CAPE TOWN MUNICIPALITY 1933. Municipal Minutes, April, p. 105. [ Links ]

CAPE TOWN MUNICIPALITY 1947. Municipal Minutes, October, p. 10. [ Links ]

CAPE TOWN MUNICIPALITY 1954. Master plan for Coloured housing. Municipal Minutes, 25 February, p. 10. [ Links ]

CAPE TOWN MUNICIPALITY. 1955. Municipal Minutes, June, p. 9. [ Links ]

CAPE TOWN MUNICIPALITY 1972. First Report on the Development of Mitchell's Plain. February. [ Links ]

CITY OF CAPE TOWN. 2012a. Conservation implementation plan for Strandveld in the Metro South-East. Final Report from the Environmental Resource Department. [ Links ]

CITY OF CAPE TOWN. 2012b. Integrated Human Settlements Five Year Strategic Plan: July 2012-June 2017. [ Links ]

CITY OF CAPE TOWN. 2017. An assessment of all informal settlements. Human Settlements Directorate. [ Links ]

CITY OF CAPE TOWN - IMAGERY 2019. Historic aerial imagery used comes from the Geospatial Services Server at: <https://gisimg.capetown.gov.za/erdas-iws/ogc/wms/Geospatial>. Links are available only from within an open GIS session. Historic photos used were for 1926, 1948 and 1958. Google Earth imagery for 2020 was used. [ Links ]

CITY OF CAPE TOWN - ZONING. 2019. City of Cape Town - Open Date Portal. [Online]. Available at: <https://odp-cctegis.opendata.arcgis.com/datasets/zoning> [Accessed: 30 January 2020]. [ Links ]

DAVIES, D. 1965. Land use in central Cape Town. Cape Town: Longmans. [ Links ]

DAY & SON LITHOGRAPHERS. 1854. Street map of Cape Town in the year 1854. [ Links ]

DE PUYFONTAINE, H.R. 1972. Louis Michel Thibault 1750-1815: His official life at the Cape of Good Hope. Cape Town: Tafelberg Publishers. [ Links ]

DEWAR, D. & WATSON, V. 1984. The concept of Khayelitsha: A planning perspective. University of Cape Town: UPRU. [ Links ]

DOMMISSE, E. 2011. Sir David de Villiers Graaff- First Baronet of De Grendel. Cape Town: Tafelberg Publishers. [ Links ]

DORRINGTON, R. 2005. Projection of the population of the City of Cape Town, 2001-2021. Report prepared for the City of Cape Town. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, May, p. 36. [ Links ]

FALUDI, A. 1973. A reader in planning theory. Oxford: Pergamon Press. [ Links ]

FALUDI, A. 1999. Patterns of doctrinal development. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 18(4), pp. 333-344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X9901800405 [ Links ]

FALUDI, A. 2004. The impact of planning philosophy. Planning Theory, 3(3), pp. 225-236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095204048816 [ Links ]

FALUDI, A. & VAN DER VALK, A. 1994. Rule and order: Dutch planning doctrine in the twentieth century. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-2927-7 [ Links ]

FLOOR, B.C. 1984. Die geskiedenis van nasionale paaie in Suid-Afrika. Kaapstad: CTP Boekdrukkers. [ Links ]

FLOYD, T.B. 1960. Town planning in South Africa. Pietermartizburg: Schuter & Shooter. [ Links ]

FRIEDMANN, J. & WEAVER, C. 1979. Territory and function: The evolution of regional planning. London: Edward Arnold. [ Links ]

HALL, P. 1998. The city of the coming golden age. In: Hall, P. Cities in civilization. New York: Pantheon Books, pp. 943-987. [ Links ]

HARTDEGEN, P. 1981. Our building heritage: An illustrated history. Halfway House: Ryll's Publishing Company. [ Links ]

HOLFORD, W. (Sir). 1961. The city and the farm - The transport revolution. Lecture 2 - Talks given in a broadcast by "English Radio Service". Later printed as an SABC publication. [ Links ]

HUCHZERMEYER, M. 1995. The history of the development of townships in Cape Town 1920-1992. CARDO Working Paper No. 2. [ Links ]

IMMELMAN, R.F. 1955. Men of Good Hope 1804-1954. Cape Town: Chamber of Commerce. [ Links ]

INSTITUTE OF RACE RELATIONS. 2014. South Africa Survey 2014/15. December, pp. 23 & 29. [ Links ]

ISLP CLOSE-OUT REPORT. 2005. Integrated Serviced Land Project: 1991-2000; The product, an iSLP publication. [ Links ]

KHOSA, M. 1991. Capital accumulation in the black taxi industry. In: Preston-Whyte, E. & Rogerson, C. (Eds). South Africa's informal economy. Cape Town: Oxford University Press, pp. 310-325. [ Links ]

KUHN, J. 1999. Informal settlement growth: An aerial photo survey: Report to the Cape Metropolitan Council. [ Links ]

KUHN, T.S. 1970. The structure of scientific revolutions. 2nd edition. Chicago, ILL: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

LAIDLER, P. 1952. A tavern of the ocean. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Limited. [ Links ]

LODGE, T. 2011. Sharpeville. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

MCLAGAN, P. & NEL, P. 1997. The age of participation: New governance for the workplace and the world. San Fransisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. [ Links ]

NATTRASS, N. 1990. Economic power and profit in post-war manufacturing. In: Nattrass, N. & Ardington, E. (Eds). The political economy of South Africa. Cape Town: Oxford University Press, pp. 107-128. [ Links ]

PALSER, D. 1998. Lighting up the Fairest Cape: 1895-1995. Publication by the City of Cape Town's Electricity Department. [ Links ]

PARNELL, S. 1993. Creating racial privilege: Public health and town planning - 1910-1920. Planning History Working Group. [ Links ]

PEJIC, I. 2019. Blockchain Babel: Crypto craze and the challenge to business. New York: Kogen Page. [ Links ]

PICARD, H. 1968. Gentleman's walk. Cape Town: Struik Publishers. [ Links ]

ROSENTHAL, E. 1957. The changing years: A history of the Cape Municipal Association. Published by the Association. [ Links ]

ROSENTHAL, E. 1980a. Milnerton Municipality. A Local Council publication. [ Links ]

ROSENTHAL, E. 1980b Goodwood and its story. Goodwood Council publication. [ Links ]

SAMUELS, L.H. 1960. The economic growth and prospects of South Africa. In: Spottiswoode, H. (Ed.). South Africa: The road ahead. Cape Town: Howard Timmins Publication, pp. 220-241. [ Links ]

SITARI. 2020. SITARI Development. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.sitari.co.za/> [Accessed: 31 January 2020]. [ Links ]

SLEIGH, D. 2004. Die buiteposte: VOC-buiteposte onder die Kaapse bestuur 1652-1795. Pretoria: Protea Boekhuis. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICA. 1950. Group Areas Act, Act 41 of 1950. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICA. 2012. North West Government Gazette vol. 255 no. 7058, December 4. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICA. BUREAU OF CENSUS AND STATISTICS. 1960. Union statistics for 50 years: 1910-60. Jubilee Issue. Pretoria: Government Printer, pp. A-12. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICA REVIEW. 1901. Land advert. SA Review, January, p. 8. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICA REVIEW. 1902. 975 Building lots advert. SA Review, November, p. 9. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN GOVERNMENT. 1979. Mitchells Plain: An investment in people. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA. 1991, 2001, 2011. Census. [Online]. Available at: <http://www.statssa.gov.za/7page_id=3836> [Accessed: 17 June 2020]. [ Links ]

SURVEYS & MAPPING. 2019. 1:50 000 map sheets showing detailed snapshots of the urban extent for the Cape for the years 1940; 1960; 1980, 1990, and 2000. [Online]. Available at: <https://htonl.dev.openstreetmap.org/50k-ct/#14/-33.9812/18.5296/c1960> [Accessed: 15 January 2021]. [ Links ]

TAYLOR, W.L. 1989. Cost of servicing Khayelitsha. Proceedings of a Symposium on Khayelitsha in Lingelethu West, Cape Town. [ Links ]

TOMLINSON, R. 1997. Ten obstacles block way to achieve targets. Business Day, 26 October, p. 8. [ Links ]

UNICITY COMMISSION. 2000. Discussion document: Developing the future City of Cape Town. A primer for the public participation process, August. [ Links ]

VAN HEYNINGEN, E. 1984. Refugees and relief in Cape Town - 1899 to 1902. Studies in the History of Cape Town, vol. 1, pp. 64-113. [ Links ]

YOUNG, J. 1998. Observatory: A town in the suburbs 1881-1913. Cape Town: Josephine Mill Press. [ Links ]

YUDELMAN, D. 1984. The emergence of modern South Africa - 1902 to 1939. Cape Town: David Philip Publishers. [ Links ]

WARREN, D. 1988. Property, profit and power: Rise of the landlord class in Cape Town in the 1840s. Studies in the History of Cape Town, vol. 6, pp. 46-55. [ Links ]

WESTERN, J. 2000. Outcast Cape Town. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [ Links ]

WILKINSON, P. 1993. A discourse on modernity: Social and Economic Planning Council's 5th Report on T&R Planning, PHSG. [ Links ]

WORDEN, N., VAN HEYNINGEN, E. & BICKFORD-SMITH, V. 1999. Cape Town in the twentieth century. Kenilworth: David Philip. [ Links ]

Received: August 2020

Peer reviewed and revised: October 2020

Published: June 2021

* The authors declared no conflict of interest for the article or title

1 An effort was made to identify such growth from much older photos.

2 Author's own view.

3 Author's own view that being both a government and a profit-seeking company is problematic.

4 Author's own reading/interpretation of the changed attitude to managing urban settlements.

5 Author's own conclusion after inspecting the maps and the cadastras and confirmation in the newspaper advertisements.

6 In 1910, roughly 13 municipalities existed within the Cape Town area. By 1994, 37 municipal authorities were in place, covering what is currently the Metro jurisdiction.

7 In 1913, eight municipalities on the Peninsula amalgamated into one Council (Worden, Van Heyningen & Bickford-Smith, 1999: 46).

8 Technically, there is no "end date", but the official programme closed during 1975-1987. This is when Mitchells Plain, or iSLP, for instance, was no longer financed as a programme. But infill development continues to this day, as these are part of the geography of Cape Town.

9 Author's own calculations.

10 Author's own interpretation.

11 Author's own observation.