Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Town and Regional Planning

On-line version ISSN 2415-0495

Print version ISSN 1012-280X

Town reg. plan. (Online) vol.77 Bloemfontein 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp77i1.3

ARTICLES

Reflections on how the implementation of sustainable development goals across the UK and Ireland can influence the mainstreaming of these goals in English planning practice

Refleksies oor hoe die implementering van volhoubare ontwikkelingsdoelwitte in die verenigde koninkryk en Ierland die hoofstroom van hierdie doelwitte in die Engelse beplanningspraktyk kan beïnvloed

Maikutlo a hore na ho kenngoa ts'ebetsong hoa merero ea nts'etsopele ea nako e telele mose ho uk le Ireland e ka ama tsebetso ea thero ea litoropo ea senyesemane joang

P.J. Geraghty

Executive Director, Hertsmere Borough Council, Civic Offices, Borehamwood, Elstree Way, Borehamwood, Hertfordshire, WD6 1WA, UK. Phone: 020 8207 7474 (ext 2200), email: <peter.geraghty@hertsmere.gov.uk>

ABSTRACT

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are an ambitious and voluntary undertaking by governments to implement sustainable development. Many countries have been pursuing a process of localisation, in which local and regional priorities are rooted in the implementation of the SDGs. The UK's implementation of SDGs has been hindered by its governance arrangements and the perspective that they are primarily for developing countries. A review of official UK parliamentary reports from 2016 to 2020 and the government's Voluntary National Review (H.M. Government, 2019) have highlighted a knowledge gap and inconsistency in the implementation of the SDGs. Years of perma-reform in planning, resulting in policy turbulence, have further retarded their adoption in England. Devolution has led to a divergence in planning practice across the UK. The approach outside of England has been much more proactive. This article seeks to bridge this knowledge gap by reflecting on practice in the UK and Ireland and how this might influence the mainstreaming of the SDGs in future planning practice in England.

Keywords: Development, devolution, goals, localisation, planning, reflection, sustainable, Sustainable Development Goals, UK, Ireland

OPSOMMING

Die Doelwitte vir Volhoubare Ontwikkeling (SDG's) is 'n ambisieuse en vrywillige onderneming deur regerings om volhoubare ontwikkeling te implementeer. Baie lande het 'n proses van lokalisering gevolg, waarin plaaslike en streeksprioriteite gewortel is in die implementering van die SDG's. Die implementering van SDG's in die Verenigde Koninkryk (VK) word belemmer deur sy bestuursreëlings en die perspektief dat dit hoofsaaklik vir ontwikkelende lande is. 'n Oorsig van amptelike Britse parlementêre verslae van 2016 tot 2020 en die Regering se Voluntary National Review (H.M. Government, 2019) het 'n kennisgaping en 'n teenstrydigheid in die implementering van die SDG's beklemtoon. Jare van permanente hervorming in beplanning wat beleidsonstuimigheid tot gevolg gehad het, het die aanvaarding daarvan in Engeland verder vertraag. Devolusie het gelei tot 'n verskil in die beplanningspraktyk in die VK. Die benadering buite Engeland was baie meer proaktief. Hierdie artikel poog om hierdie kennisgaping te oorbrug deur na te dink oor praktyk in die VK en Ierland en hoe dit die hoofstroom van die SDG's in toekomstige beplanningspraktyke in Engeland kan beïnvloed.

Sleutelwoorde: Afwenteling, beplan-ning, doelwitte, lokalisering, ontwikkeling, refleksie, volhoubaar, volhoubare ontwik-kel ingsdoelwitte, VK, Ierland

SA BONAHALENG

Merero ea Nts'etsopele ea Nako e Telele (SDGs) ke boikemisetso le boithatelo bo etsoang ke mebuso ho kenya tsebetsong nts'etsopele e tsoarellang. Linaha tse ngata li ntse li latela ho kenya li SDG ts'ebetsong ea lehae, moo lintho tsa mantlha tsa lehae le tsa tikoloho li thehiloeng ts'ebetsong ea li-SDG. Ts'ebetso ea UK ea li-SDG e sitisitsoe ke mokhoa oa eona oa puso le maikutlo a hore li SDG li molemong oa linaha tse futsanehileng. Tlhahlobo ea litlaleho tsa semmuso tsa paramente ea UK ho tloha 2016 ho isa 2020 le Voluntary National Review (HM Government, 2019) li bonts'itse khaello ea tsebo le ho se lumellane ts'ebetsong ea li-SDG. Lilemo tse ngata tsa phetoho-kholo meralong, e bakileng pherekano ea maano, li fokolisitse kamohelo ea li SDG naheng ea Engelane. Tlhahiso-pele e lebisitse ho fapakaneng mekhoeng ea ho rala UK. Mokhoa o kantle ho Engelane oa thero obonts'a maemo a holimo a ho nka likhato mapabi le li SDG. Sengoloa sena se batla ho koala lekhalo lena la tsebo ka ho nahanisisa tsebetso ea ho rala UK le Ireland le hore na sena se ka ama tsusumetso ea li-SDG joang mokhoeng oa ho rala bokamosong ba Engelane.

1. INTRODUCTION

The implementation of the United Nation's (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is fundamental to achieving resilient cities and communities. Clear, strong leadership at international, national and local levels is key to implementing the SDGs. Decisions should be made at the appropriate level.1

Biermann, Kanie and Kim (2017: 26) point out that past global governance efforts have relied largely on top-down regulation or market-based approaches, and that the SDGs promise a novel type of governance that makes use of non-legally binding, global goals set by the UN member states. The approach of governance through goals is marked by a number of key characteristics such as the inclusive goal-setting process, the non-binding nature of the goals, the reliance on weak institutional arrangements, and the broad latitude that states enjoy, none of which is specific to this type of governance. These characteristics together result in a new and distinct means of institutional global governance (Biermann et al., 2017: 26).

Since the adoption of the SDGs, many countries have been pursuing a process of localisation, in which local and regional priorities are rooted in the implementation of the SDGs, as will allow the co-creation of a new framework of governance that is meaningful and practical in the day-to-day lives of citizens. Localisation requires multi-level and multi-stakeholder coordination, financial support, and capacity-building for local and regional governments to effectively participate (GTL & RG, 2020: 9).

The current political environment in England is both turbulent and unreceptive to professional planning. This is typified by the relentless reforms that have occurred in the English planning system over the past ten years (2010-2020). These reforms have resulted in fundamental changes to planning practice (Jones, Hillier & Comfort, 2016). The mood music to this planning reform has been one of scepticism from senior political figures (Geraghty, 2017a: 168). The culmination of this has been the publication of a White Paper on planning reform in August 2020 (MHCLG, 2020). In the forward to the White Paper, the Prime Minister maintains the sceptical view of planning:

"The whole thing [planning system] is beginning to crumble and the time has come to do what too many have for too long lacked the courage to do - tear it down and start again."

In response to the political scepticism and reform agenda, the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI) has sought to demonstrate the value of planning (Adams, O'Sullivan, & Inch, 2016). The RTPI points out that understanding and evaluating the impact of planning in relation to higher level goals such as the UN SDGs, or other national government outcomes tied to these, is ambitious and still in the early stages:

"Our survey evidence suggests that while this is progressively being established in many places, there is still not necessarily a clear knowledge of what is being delivered through the planning system. If there can be more comprehensive data on the outcomes of a planning application for example, looking beyond simply number of units built, then evaluating the wider cumulative impact would represent a considerable leap in understanding performance." (RTPI, 2020: 19-20).

This article considers the occurrence of localisation in the devolved nations of the United Kingdom (UK) and Ireland and reflects on how understanding divergent practice can assist in addressing the knowledge deficiency among planning professionals and policymakers. In particular, how learning from the devolved nations can support the mainstreaming of the SDGs in future planning practice in the UK.

2. THE METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH

The approach adopted involved a literature review of official UK parliamentary reports from when the SDGs came into force to the present (2016-2020), the government's Voluntary National Review (H.M. Government, 2019), and the National Planning Policy Framework. This review highlighted a knowledge gap and inconsistencies in implementing the SDGs. One way of bridging this knowledge gap is through reflective practice. As Willson pointed out, the idea of reflective practice is not new (Schön, 1983) but during turbulent and challenging times it can be a valuable approach. Willson (2020) mentions that reflection particularly helps planners navigate between idealism and realism. Reflecting on the manner in which the SDGs have been implemented in the devolved nations, Ireland and at local authority level provides indicators on how the SDGs could be mainstreamed in future planning practice in England. As a practitioner working in local government in England, it is critical to have commitment from central government to delivering the goals, and importantly, clear guidance as to how they are implemented and applied. This, coupled with a monitoring regime, is essential to ensure that they are achieved at all levels of governance, as envisaged by the UN. Many countries are applying a localisation approach, which requires multi-level and multi-stakeholder support. Without a clear implementation strategy, which the White Paper could have identified, it is difficult to perceive how the necessary resources and capacity are available to successfully achieve their implementation.

3. BACKGROUND TO SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS

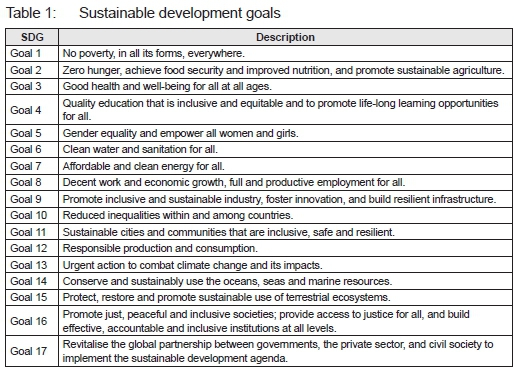

The UN (2015) adopted Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for sustainable development that included 17 SDGs and 169 associated targets. The SDGs came into force on 1 January 2016. Table 1 sets out the seventeen goals, all of which are relevant to creating sustainable places (Geraghty, 2017b: 519). Underpinning the SDGs and targets are a series of 244 indicators, or 232 if the nine indicators that repeat under two or three different targets are taken into account.

The approach to governance embodied in the SDGs (Biermann et al., 2017: 26) requires a whole-of-government and a whole-of-society approach. It is necessary to achieve more accountable and effective governance and more inclusive societies, based on strengthening existing partnerships and building new ones (GTL & RG, 2020: 14). Participation is an essential component of sustainable urban development, promoted by the 2030 Agenda (UN-Habitat, 2020: 8). The role of different levels of government in the implementation of the SDGs depends on the political and institutional framework of each country. Each level of government should have the capacity to set its own priorities in line with its legal areas of responsibility, and to pursue them through local and regional plans and sectoral policies (GTL & RG, 2016: 25). This is increasingly being achieved through a process of localisation. Mainstreaming the SDGs into local plans and policies appears to be a prominent objective in the strategies adopted by an increasing number of countries (GTL & RG, 2020: 48). Many regions are moving from mere commitments to alignment actions through mainstreaming the SDGs (GTL & RG, 2020: 115). Localisation involves an institutionalized dialogue between local and national governments to implement local and national plans aligned with the SDGs. In England, this dialogue is not occurring because of the gap between local authorities and national government (see 4.1).

4. IMPLEMENTATION OF SDGS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM

Whilst planning is a devolved function, given the international nature of the 2030 Agenda, the UK government oversees the introduction of the SDGs. The government department responsible for overseeing the implementation of the SDGs is not the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) but the Department for International Development (DFID) (2017: 1), subsequently replaced by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. A review by the House of Commons (HoC) International Development Committee was unequivocal about the issue:

"Placing the responsibility for implementation of the SDGs - and by extension the Voluntary National Review - in the Department for International Development is simply wrong. The practicalities are that DFID is an internationally-focused department whose Ministers have recognised that they have 'relatively few, if any, domestic levers'. The message in this arrangement is that the SDG initiative is one for developing countries ..." (HoC International Development Committee, 2019: 3).

This has created a weakness that pervaded the whole approach to delivering the SDGs in England. Government departments are required to embed the goals in their single departmental plans (SDPs) (House of Lords Library, 2018). The Cabinet Office has been given a role in coordinating domestic delivery of the goals through the SDP process.

4.1 Parliamentary scrutiny of the implementation of sustainable development goals

The 2030 Agenda specifies that the monitoring and review of the SDG process be "voluntary, state-led, undertaken by both developed and developing countries, and shall provide a platform for partnerships, including through the participation of major groups and other relevant stakeholders" (UN, 2015: 39). As part of the UN's review and monitoring process, member states are encouraged to conduct "regular and inclusive [national] reviews" called voluntary national reviews (VNRs). The UK Government published its VNR on 26 June 2019 (H.M. Government, 2019: 8-12).

There is a strong sense of disengagement in the "domestic" implementation of SDGs elsewhere in government, particularly MHCLG, which is responsible for planning and local government. For example, as recently as January 2019, the HoC Environmental Audit Committee (2019: 3) reported:

"In their present format, Single Departmental Plans (SDPs) are insufficient to deliver the SDGs in the UK. Government's failure to ensure that all SDG targets are covered in the SDPs has left significant gaps in plans and accountability".

The UK's approach to implementing the SDGs has been the subject of scrutiny by several committees.

This has highlighted considerable inconsistencies. Concern has been expressed about the lack of awareness of the existence and relevance of SDGs. In 2016, the HoC International Development Committee (2016: 34) reported:

"The Government's response to domestic implementation of the SDGs has so far been insufficient for a country which led on their development as being universal and applicable to all ... Engagement of government departments will be central to the success of domestic implementation, which itself has an impact on making progress on the goals globally."

The Committee went so far as to say that:

"We are deeply concerned at the lack of a strategic and comprehensive approach to implementation of the Goals. Without this, it is likely that areas of deep incoherence across government policy could develop and progress made by certain departments could be easily undermined by the policies and actions of others. It also reflects a worrying absence of commitment to ensure proper implementation of the SDGs across government." (HoC International Development Committee, 2016: 59).

The Committee (2016: 54) recommended that "all HoC departmental select committees engage with the SDGs, particularly those goals and targets most relevant to their departments."

The HoC Environmental Audit Committee is responsible for considering the extent to which the policies and programmes of government departments contribute to sustainable development. In April 2017, it published a report that scrutinised how the Government was implementing the SDGs and the framework for national monitoring and reporting (HoC Environmental Audit Committee, 2017).

The Committee found that there was an "accountability gap" across government, with no central coordination or "voice at the top of government speaking for the long-term aspirations embodied in the goals" (HoC Environmental Audit Committee, 2017: 26). It recommended that the Government should appoint a cabinet-level minister with strategic responsibility for implementing sustainable development, including the SDGs (Table 1), across government.

According to the Audit Committee, the Government seemed "more concerned with promoting the goals abroad" and had "undertaken no substantive work to promote the goals domestically or encourage businesses, the public sector and civil society to engage with the goals" (HoC Environmental Audit Committee, 2017: 4). It stated that raising awareness and encouraging engagement would increase the number of people and organisations able to contribute towards meeting the SDGs. In this regard, it is interesting to note that it is left to the Local Government Association (LGA) to produce guidance for local authorities on SDGs (LGA & UKSSD, 2020).

The Audit Committee bemoaned the slow progress on developing measurement frameworks for the SDGs and that the Government has shown little interest in, or enthusiasm, for implementing the SDGs in the UK (HoC Environmental Audit Committee, 2017: 7).

The disjointed nature of implementing the SDGs across government is highlighted in the report on the UK's progress with SDGs and preparation of the VNR by HoC International Development Committee. It concluded:

"For future VNRs, it is essential that an appropriate mechanism is created - at the heart of Government ... to lead on communication and implementation of the SDGs. If such a mechanism had been in place, bringing together the VNR would have been much more straightforward. Instead, the process was incredibly fragmented, with chapters of the VNR drafted, ... in isolation, by different departments. The process to bring all of the sections of the report together was then very complex" (HoC International Development Committee, 2019: 23).

This is reflected in a 2018 report by UK Stakeholders for Sustainable Development (UKSSD). Out of 143 targets relating to the SDGs, the UK is performing well on only 24% of them. There are gaps in policy or inadequate performance for 57% of the targets, and 15% where there is little to no policy in place to address the target, or where performance is poor (UKSSD, 2018).

5. IMPLEMENTATION OF SDGS IN ENGLAND

The constituent parts of the UK (England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland) have, until relatively recently, been governed centrally from London. Between 1998 and 1999, the Scottish Parliament, the National Assembly for Wales, the Northern Ireland Assembly and the London Assembly were established by law. The devolved nations have powers to legislate for planning and environmental matters, including the implementation of the SDGs.

5.1 The demise of English regional planning and a decade of perma-reform

In England, there has been a long-standing antipathy from the Conservative Party towards regional planning and governance. This is demonstrated in a Green Paper entitled "Open Source Planning" (2010), which espoused unequivocally that "[w]e believe that the introduction of a regional planning layer has been an expensive failure and have no qualms about dismantling it" (Conservative Party, 2010: 10). On entering into a coalition government in May 2010, they dissolved Regional Assemblies and abolished Regional Spatial Strategies in favour of neighbourhood planning enacted in the 2011 Localism Act. In the absence of a clear localisation agenda, these actions have had a detrimental effect on the implementation of the SDGs in England, as evidenced by the findings of many parliamentary committees (see section 4.1).

Tewdwr-Jones (2012: 212) pointed out:

"The emerging function of governance across different parts of the UK appears to be reliant on both formal and informal structure of policy making. In the absence of strict codes and institutional, statutory and political parameters provided by central government for the establishment of the more ad hoc, informal partnership bodies, governance in different parts of the UK appears to be a diverse picture of fragmentation and responsibility."

Since the dissolution of regional governance in the UK, there has been an increasing trend towards regional inequality. It has arrested decision-making at a regional or sub-regional level. The UK 2070 Commission, which undertook an inquiry into regional inequalities in the UK, highlighted these issues in its final report, which states that there is "a lack of institutions to take strategic decisions locally". This, in turn, leads to:

"a growing inequality ... New devolved, decentralised and inclusive administrative structures, powers and resources are required, which are sensitive to national and regional differences and local circumstances, and which will create the institutional capacity to bring about change" (UK 2070 Commission, 2020: 34).

The dissolution of regional governance has been accompanied by a decade of perma-reform in English planning (Geraghty, 2019b), leading to what Tewdwr-Jones (2012: 221) describes as "policy turbulence". Such turbulence causes difficulty for spatial planning because of the rapidity of change and the extended time it takes for spatial strategies to be developed.

5.2 Deficiencies in the approach to the implementation of SDGs in England

This "policy turbulence", as described by Tewdwr-Jones, is exemplified by the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). First published on 27 March 2012, the NPPF consolidated 1,300 pages of government policy. It is the backbone of the English planning system (Geraghty 2019a: 354). It underwent a major revision in July 2018 (MCLG, 2018) and was further revised in February 2019 (MCLG, 2019).

Paragraph 7 of the NPPF states: "The purpose of the planning system is to contribute to the achievement of sustainable development." The NPPF would have been the natural document in which to set out a framework for achieving SDGs. However, the updated NPPF makes no reference to the SDGs or how they might be achieved (Geraghty, 2019a: 361). Similarly, the DFID (2017) report on SDGS makes no reference to urban planning or the NPPF.

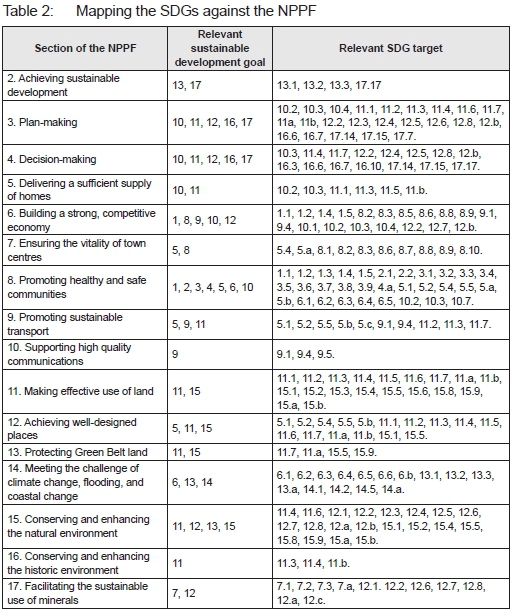

It would have been possible to map the NPPF against the SDGs and use it to show how compliance with them might be achieved. This is consistent with the approach recommended by the guidance produced by the LGA (LGA & UKSSD, 2020: 13). In contrast, the Northern Ireland Assembly carried out such a mapping exercise for the SDGs (DAERA, 2018). Geraghty (2019a: 364) demonstrated how, even with a basic approach, the NPPF can be mapped against the SDGs. This mapping would be the first step to the formalization of SDG commitments, as discussed in Biermann et al. (2017: 27). It could then have provided the framework for local authorities to carry out VLRs and to inform development plans. Table 2 shows this mapping exercise (Geraghty, 2019a: 363).

Moreover, planning authorities produce Annual Monitoring Reports, which typically include themes concerning the quality of development, planning performance, user and neighbourhood experience, and infrastructure delivery (RTPI, 2020).

The NPPF could have set out guidance as to how these reports could be used to demonstrate how authorities are achieving the SDGs. They could also be linked to VLRs (see Bristol City in section 5.3 below).

The Environmental Audit Committee of the House of Commons stated:

"the Government has not yet done enough to drive awareness and embed the SDGs across the UK -including within Government itself. We reiterate the recommendation made in our predecessor Committee's 2017 report that the Government should do everything it can to support partners (government agencies, local government, civil society, business and the public) to contribute towards delivering the Goals. The Government should show leadership." (HoC Environmental Audit Committee, 2019: 3-4).

This lack of awareness is reflected in the VNR, which hardly makes any reference to the NPPF. As will be noted later, the Republic of Ireland has identified a strategic priority under the SDG National Implementation Plan to mainstream "the SDGs across national policies, so that when relevant sectoral policies are developed or reviewed, Ireland's commitments under the SDGs will be taken into account" (Government of Ireland, 2018: 9).

The absence of leadership in government in implementing the SDGs and the diffidence towards regional governance has led some cities and local authorities to become catalysts of change to bridge the gap. A point made by United Cities and Local Government (UC & LG):

"All of the SDGs have targets that are directly or indirectly related to the daily work of local and regional governments. Local governments should not be seen as mere implementers of the agenda. Local governments are policy makers, catalysts of change and the level of government best-placed to link the global goals with local communities" (UC & LG, 2015: 2).

5.3 Implementation of SDGs at a local level in England

In contrast to the dilatory approach at a national level in England, some English local authorities and cities are demonstrating local leadership in implementing SDGs. The currently small number of examples of practice in England probably arise from the low level of awareness and the failure of the NPPF to promote the goals. The LGA has stepped in to fill the gap by producing a guide for local authorities. To implement the SDGs, the LGA advises local authorities to identify which of their own existing goals, targets, plans and policies contribute to each of the SDGs, broadly supporting either the entire goal or one or more of the targets within it (LGA & UKSSD, 2020:13). One of the challenges for local authorities is finding a balance between a comprehensive set of indicators (which can include the locally adapted SDG indicators) and using their existing monitoring frameworks such as annual monitoring reports (Klopp & Petretta, 2017: 92-97). The introduction of national guidance through the NPPF or other guidance would assist in achieving this:

"Achievement of the SDGs depends heavily on the active involvement of regional and local authorities, in particular through specific approaches to translate the SDGs into their own context." (EU, 2019: 12)

In the absence of national or regional guidance, cities are taking an increasing role in promoting the SDGs. The latest draft Greater London Authority's (GLA) London Plan sets out the aspiration that "the concept of Good Growth - growth that is socially and economically inclusive and environmentally sustainable - underpins the London Plan and ensures that it is focused on sustainable development" (Mayor of London, 2019: paragraph 0.0.18); it does not however, identify the SDGs specifically. This is somewhat surprising but may, in some part, be due to their absence from the NPPF.

The City of London Corporation established the London Sustainable Development Commission (LSDC) in 2002 to promote sustainable development in London and raise awareness of the SDGs. The LSDC provides independent advice on the sustainable nature of London-wide strategies, including those produced by the GLA. The LSDC comprises key representatives from London's economic, social, environmental, and governance sectors. It aims to publish a report on London's progress on the SDGs.

In Bristol City, the Bristol SDG Alliance has been established as a network of stakeholders who are interested in discussing and advocating the practical use of the SDGs and leading the way in the implementation of SDGs in the UK and internationally. The Alliance includes a range of Bristol City Council officials. This initiative was further supported by the creation of a new Cabinet-level SDG Ambassador role, to be undertaken by the Cabinet member for Education and Skills. The new Ambassador will raise awareness and the profile of Bristol's SDGs work. S/he will also champion the SDGs in local development plans, and act as the political lead for the goals. This is the first role of its kind in the UK (Townsend & Macleod, 2018: 13-14). Bristol City Council launched Bristol One City Plan in January 2019. This Plan was developed through extensive consultation and citizen engagement and articulates a vision for making Bristol a fair, healthy and sustainable city for all by 2050. A commitment to the SDGs is integral to the plan. The SDGs' vision for sustainable and inclusive prosperity that "leaves no-one behind" is strongly aligned with the city's collective priorities and ambitions (Fox & Macleod, 2019: 8).

In 2019, Bristol became the first UK local authority to publish a VLR setting out its progress on all 17 of the SDGs. The VLR was presented to the UN in New York in 2019 at the same time as the UK Government's VNR. The VLR was prepared by Bristol University's Cabot Institute for the Environment in partnership with the Council's City Office and the Bristol SDG Alliance (LGA & UKSSD, 2020: 17). Bristol's pioneering VLR has influenced updating of the One City Plan and established the city's UK leadership position in local level application of the SDGs (LGA & UKSSD, 2020: 17).

York City in north Yorkshire, England, is placing sustainability at the heart of its future actions. On 17 March 2016, the authority's Executive approved the implementation of One Planet York, so that sustainability is put "at the heart of everything we do" and drives wider progress towards creating a sustainable, resilient, and collaborative "One Planet" city. The Council developed a One Planet Council Action Plan, with specific plans, targets and indicators. One Planet York is a growing network of organisations working to make York a more sustainable, resilient, and collaborative "One Planet" city. This includes creating a city that has a thriving local economy, strong communities, and a sustainable way of life; a city where residents are healthy, happy and prosperous (York City Council).

The City Council commissioned a development agency to examine 20 of the Council's high-level corporate strategies. These included the Draft Local Plan, the York Economic Plan, the overarching Council Plan 2015-2019, the York Economic Strategy, and the Health and Well-being Strategy. The assessment judged that all but two of the 17 SDGs were relevant to York - the exceptions were SDG 14 (Life below water) and SDG 17 (Partnership for the Goals). It found that roughly a fifth of the 169 SDG targets were relevant to the Council and its work with partners. The Council's corporate strategies were well aligned with 70% of those relevant targets (LGA & UKSSD, 2020: 15).

In 2019, Newcastle City Council made a commitment to mainstream the SDGs in its policies, activities, and programmes. A team from Newcastle University is collaborating with the Council and other partners to better understand the city from an SDG perspective, with the potential to frame future collaboration and inform the city's Future Needs Assessment. In February 2020, the Council also committed to embed the SDGs in the new workplan of the city's Well-being for Life Board. This Board consists of organisations including the Newcastle City Council, the National Health Service in Newcastle, the voluntary and community sector, local universities and Healthwatch Newcastle, an independent statutory body that champions people using health and social care services (LGA & UKSSD, 2020: 22).

There are some examples of the application of SDGs in plan-making, including neighbourhood planning (Geraghty, 2019a: 364). For example, in London, the Knightsbridge Neighbourhood Forum has prepared the Knightsbridge Neighbourhood Plan 2017-2037, which refers specifically to the SDGs and how they contribute to development in the neighbourhood area, specifically "the principles which underpin the Plan reflect the 17 Sustainable Development Goals" (Knightsbridge Neighbourhood Forum, 2017: 19, 85).

Salford City Council in Greater Manchester, England, is using its Local Plan to drive equality issues. Chapter 5 of the Revised Draft Local Plan for Salford, a fairer city (January 2019) identifies the importance of the SDGs in achieving a fairer Salford. The plan states that "delivering a fairer Salford is central to everything that the Local Plan is seeking to accomplish" (Salford City Council, 2019: 30).

Southend-on-Sea Borough Council in Essex, England, is currently preparing a new Local Plan. The new Plan will provide the planning framework for Southend to 2036, beyond the current plan period of 2021. It is currently at the Issues and Options stage of the formal plan-making process (Southend-on-Sea Borough Council, 2019). As part of that stage, the draft plan includes sections on how different policies or issues contribute to the SDGs. The draft plan seeks to achieve the delivery of these goals through the plan-making process and to engage the local community and stakeholders on how that might be achieved (Geraghty, 2019a: 364). As the draft plan is advanced, the SDGs will inform the development of plan policies.

6. THE IMPLEMENTATION OF SDGS IN DEVOLVED NATIONS

6.1 The implementation of SDGs in Scotland

The National Performance Framework (NPF) is the mechanism delivering the SDGs in Scotland. The NPF was recently reviewed and sets out the vision for Scotland. This vision is expressed through 11 national outcomes, a set of values that establish a collective purpose for Scotland focusing on well-being, sustainability and inclusive economic growth. The NPF is identified in statute through the Community Empowerment (Scotland Act) 2015, which places a duty on Scottish ministers to review the National Outcomes every five years. The next review is due in 2023.

There are 81 national indicators underpinning the 11 outcomes that will help track progress in achieving these long-term outcomes. The SDGs have been embedded into the NPF by mapping the goals to the outcomes and aligning the indicators, where appropriate and possible. This integration means that working towards delivering the national outcomes will also enable progress against the SDGs.

The Scottish National Outcome "Communities" corresponds closely with SDG11. It aims to create inclusive, safe, and resilient places for all, and it is monitored by eight of the NPF national indicators. One of these, the accessibility to green public space, is a close match with SDG target 11.7.

In future, policy and plans that sit below the National Performance Framework may give an opportunity to address the other nine SDG11 targets. For example, housing affordability is expected to be addressed in the fourth Scottish National Planning Framework (NPF4).

In contrast, the English equivalent, the NPPF, which was only revised in 2019, does not even mention the SDGs (see section 5.3).

The commitment to sustainable development is further strengthened in the Planning (Scotland) Act 2019, which identifies that the purpose of planning is to manage the development and use of land in the long-term public interest, which ties planning to sustainable development and the delivery of the Scottish national outcomes. Performance of local planning authorities in Scotland is measured by an annual Planning Performance Framework.

6.2 The implementation of SDGs in Wales

The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 requires public bodies to think more about the long-term, work better with people and communities and each other, and take a more joined-up approach to improve the social, economic, environmental and cultural well-being of Wales. This Act includes ambitious, long-term goals for Wales. It sets 44 public bodies, including the Welsh Government, a legally-binding aim to work towards the seven goals set out in the Act. The Act also supports the principle of sustainable development and aligns with the Agenda 2030. It sets out the five ways of working which, when adopted, will contribute to maximising the benefits achieved across the seven goals.

There is a clear focus on improving social, economic, environmental, and cultural well-being in Wales. Progress towards the seven "well-being goals" will be measured through a set of 46 national indicators. These indicators align to, but are not an exact match with the SDGs. They reflect a localised approach to sustainable development (GTL & RG, 2016: 28).

The Act does not set milestones or a time frame to achieve the "well-being goals", leaving it to the action of the successive Welsh Governments to guarantee their implementation. It places a legal requirement on Welsh Ministers to set national indicators for the purpose of measuring progress towards the achievement of the "well-being goals".

Eight of the 46 Welsh indicators are closely aligned with the SDG11 targets. The current approach to implementing the Well-being of Future Generations Act focuses on planning, housing, and transport. For example, the Welsh National Development Framework (NDF) - a spatial strategy due to be published in 2020 - will directly link to their achievement.

Each year a Well-being of Wales Report (Welsh Government, 2019) is published that provides an update of the progress, with a more detailed report issued every four to five years to review long-term performance.

Policy and monitoring in Wales is also being aligned. Planning Policy Wales (PPW10) integrates the Well-being Act into national planning policy, and the Welsh Government's Planning Directorate has established the Planning Performance Framework to assess the contribution of Welsh planning to their achievement. Local planning authorities in Wales produce an Annual Performance Report.

The Planning Performance Framework metrics relevant to the SDG11 cover the quality and efficiency of local plans, the degree of participation in local plan-making, and the supply of land and housing. However, they do not currently address housing affordability or sustainable transport.

The commitment to sustainability is further recognised in the Environment Wales Act of 2016, which sets out a commitment to the promotion of the sustainable management of natural resources.

6.3 The implementation of SDGs in Northern Ireland

Planning was decentralised only in April 2015. Consequently, the approach to SDGs in Northern Ireland is less evolved than in Scotland or Wales. The three elements of sustainable development, namely economic, social, and environmental, are incorporated into the Northern Ireland Civil Service Strategic Plans, rather than through separate sustainability strategies. This has resulted in the principles of sustainable development being embedded in the Northern Ireland Executive's highest level strategy, the draft Programme for Government (H.M. Government, 2019: 12). The Strategic Planning Policy Statement for Northern Ireland: Planning for Sustainable Development (SPPS) and the Living Places Urban Stewardship and Design Guide for Northern Ireland (2014), which are designed to ensure the planning system, provide for places that encourage healthier living and promote accessibility and inclusivity. Under section 25 of the Northern Ireland (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2006, government departments and local authorities have a statutory duty to promote the achievement of sustainable development in the exercise of their functions. In government departments, mapping exercises have been carried out to show how delivery plans align with these goals (DAERA, 2018).

6.4 The implementation of SDGs in the Republic of Ireland

Ireland has adopted a "whole-of-Government" approach to the SDGs. In March 2018, Ireland adopted its first Sustainable Development Goals National Implementation Plan 2018-2020 (DCCAE, 2018), setting out ambitious high-level commitments that address the 17 SDGs, and taking account of the social, economic, and environmental dimensions of the 2030 Agenda. The Implementation Plan includes an ambitious "2030 Vision" for Ireland to fully achieve the SDGs at home and to support their implementation worldwide. The Implementation Plan builds on Ireland's national sustainable development strategy (DCCAE, 2012) and Ireland's policy for international development (Government of Ireland, 2013) and commits Ireland to mainstreaming the SDGs across national policy (Government of Ireland, 2018: 6). Our Sustainable Future sets out Ireland's eight national themes and principles for achieving sustainable development. These themes reflect the traditional economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainability, and are closely aligned with the SDGs.

The Implementation Plan is the first in a series of implementation plans, each of which will endeavour to integrate the SDGs into national policy. The Plan identifies four strategic priorities to guide implementation:

• Awareness: Raise public awareness of the SDGs.

• Participation: Afford stakeholders the opportunity to engage and contribute to follow-up and review processes, and further develop national implementation of the Goals.

• Support: Encourage and support efforts of communities and organisations to contribute towards meeting the SDGs, and foster public participation.

• Policy alignment: Develop alignment of national policy with the SDGs and identify opportunities for policy coherence.

These priorities represent a process of localisation. While some of the SDGs are more closely aligned with individual national themes than others, Ireland's implementation of every goal will be informed by these themes and principles as a whole, in recognition of the fact that the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainable development cannot be advanced in isolation from each other. It sets out how the SDGs align with Ireland's national themes for sustainable development. However, in order to further integrate the SDGs into national policy, Ireland will prepare and adopt a new sustainable development strategy by the end of 2020, which will directly incorporate the SDGs (Government of Ireland, 2018: 10).

Mapping the SDGs against government policy is achieved by an SDG matrix that identifies the responsible government departments for each of the 169 targets. It also includes an SDG policy map, indicating the relevant national policies for each of the targets. The Plan also sets out 19 specific actions to be implemented over the plan period. This mapping methodology contrasts with the fragmented approach of the UK Government using SDPs, which the HoC Audit Committee concluded are "insufficient" to deliver the SDGs. The publication of an implementation plan for England would provide much needed clarity and leadership.

7. CONCLUSION

The success of implementing the SDGs depends on government at all levels and civil society working together. Following the adoption of the 2030 Agenda, many countries have been pursuing a process of localisation, in which local and regional priorities are rooted in the implementation of the SDGs, creating a new meaningful and practical framework of governance relevant to the lives of citizens.

The UK Government's approach to implementing the goals has been hampered by its governance arrangements and its perspective that the SDGs are for developing countries (HoC International Development Committee, 2019: 3). This has led to a lack of awareness of the existence and relevance of SDGs (HoC Environmental Audit Committee, 2019: 3-4), which has inhibited their adoption. Moreover, a lack of regional governance, coupled with years of perma-reform (Geraghty, 2019b), resulting in significant policy turbulence, has retarded their adoption in England, in particular.

Whilst there are some examples of where local government in England is beginning to take up the challenge of achieving the SDGs, reflecting on the lessons drawn from practice in Wales, Scotland and Ireland, strong leadership across all levels of government is fundamental to implementing the SDGs. A voice at the top of government speaking for the long-term aspirations embodied in the SDGs is vitally necessary (HoC Environmental Audit Committee, 2017: 3, 31). For example, including them in a national implementation plan as in Ireland, or in primary legislation, as is the case with Wales. This is critical where regional governance is weak or non-existent, as is the case in England. Government needs to empower local authorities to fulfil the important role in meeting the challenge of implementing the SDGs. This could have been done by means of the revisions to the NPPF, or new guidance on LVRs or AMRs. Reflecting on practice elsewhere in the UK and Ireland, the recent White Paper could have been the first step in introducing such measures and mainstreaming the SDGs in England.

REFERENCES

ADAMS, D., O'SULLIVAN, M. & INCH, A. 2016. Delivering the value of planning. RTPI Research Report No.15, August. London: RTPI. [ Links ]

BIERMANN, F., KANIE, N. & KIM, R.E. 2017. Global governance by goal-setting: The novel approach of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, vol. 26-27, pp. 26-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.01.010 [ Links ]

CONSERVATIVE PARTY 2010. Open source planning. London: Central Office. [ Links ]

DCCAE(DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATIONS, CLIMATE ACTION AND ENVIRONMENT). 2012. Our sustainable future, a framework for sustainable development in Ireland. Dublin: Department of Environment, Community and Local Government. [ Links ]

DCCAE (DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATIONS, CLIMATE ACTION AND ENVIRONMENT). 2018. Sustainable development goals national implementation plan 2018-2020. Dublin: Department of Environment, Community and Local Government. [ Links ]

DAERA (DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, ENVIRONMENT AND RURAL AFFAIRS). 2018. United Nations sustainable development goals mapped to programme for government outcomes and indicators. [Online]. Available at: <daera-ni.gov.uk> [Accessed: 22 November 2020]. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT 2017. Agenda 2030. The UK Government's approach to delivering the Global Goals for Sustainable Development - at home and around the world. London: Department of international development. [ Links ]

EU (EUROPEAN COMMISSION). 2019. Supporting the sustainable development goals across the world: The 2019 joint synthesis report of the European Union and its member states, COM(2019) 232 final. Brussels: EU. [ Links ]

FOX, S. & MACLEOD, A. 2019. Bristol and the SDGs: A voluntary local review of progress. Bristol: Cabot Institute for the Environment at the University of Bristol. [ Links ]

GERAGHTY, P. J. 2017a. Why are planning awards important? Planning Theory and Practice, 18(1), pp. 168-172. [ Links ]

GERAGHTY, P. J. 2017b. The new urban agenda and sustainable development goals - Do they have relevance for the UK? Journal of the Town and Country Planning Association, 86(12), pp. 519-526. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2016.1271510 [ Links ]

GERAGHTY, P. J. 2019a. The NPPF 2019 - A new urban agenda or a disappointing own goal? Journal of the Town and Country Planning Association, 88(9), pp. 354-366. [ Links ]

GERAGHTY, P. J. 2019b. Blog for the American Planning Association, English Planning: The fruits of 10 years of austerity and reform, posted 8 November 2019. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.planning.org/blog/9189021/english-planning-fruits-of-10-years-of-austerity-and-reform/> [Accessed: 30 June 2020]. [ Links ]

GOVERNMENT OF IRELAND. 2013. One world, one future: Ireland's policy for international development. Dublin: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. [ Links ]

GOVERNMENT OF IRELAND. 2018. Ireland: Voluntary national review. Dublin. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.dccae.gov.ie/documents/Ireland%20Voluntary%20National%20Review%202018.pdf> [Accessed: 30 June 2020]. [ Links ]

GTL & RG (GLOBAL TASKFORCE OF LOCAL & REGIONAL GOVERNMENTS). 2016. Roadmap for localising the SDGs: Implementation and monitoring at subnational level. Barcelona: UNHABITAT. [ Links ]

GTL & RG (GLOBAL TASKFORCE OF LOCAL & REGIONAL GOVERNMENTS). 2020. Towards the localisation of the SDGs. Local and regional governments' report to the 2020 HLPF, 4thReport. Barcelona: UNHABITAT [ Links ]

HoC ENVIRONMENTAL AUDIT COMMITTEE. 2017. Sustainable Development Goals in the UK, 26 HC 596 of session 2016-2017. London: House of Commons. [ Links ]

HoC ENVIRONMENTAL AUDIT COMMITTEE. 2019. Sustainable development goals in the UK follow-up: Hunger, malnutrition and food insecurity in the UK. 73thReport of session 2017-2019, HC 1491. London: House of Commons. [ Links ]

HoC INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE. 2016. UK implementation of the sustainable development goals. 1 st Report of session 2016-2017, HC 103. London: House of Commons. [ Links ]

HoC INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE. 2019. UK progress on the sustainable development goals: The Voluntary National Review. 12thReport of Session 2017-2019, HC 1732. London: House of Commons. [ Links ]

H.M. GOVERNMENT. 2019. Voluntary National Review of progress towards the sustainable development goals, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. London: Crown. [ Links ]

HOUSE OF LORDS LIBRARY 2018. UN sustainable development goals: Integration into UK policy debate on 22 November 2018. London: Crown. [ Links ]

JONES, P., HILLIER, D. & COMFORT, D. 2016. Assessing planning reform. Journal of the Town and Country Planning Association, 85(5), pp. 201-204. [ Links ]

KLOPP, M. & PETRETTA, D.L. 2017. The urban sustainable development goal: Indicators, complexity and the politics of measuring cities. Cities, vol. 63, pp. 92-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.12.019 [ Links ]

KNIGHTSBRIDGE NEIGHBOURHOOD FORUM. 2017. Knightsbridge Neighbourhood Plan 2017-2037. London. [Online]. Available at:<https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/london-neighbourhood-plan-global-ambitions> [Accessed: 30 June 2020]. [ Links ]

LGA & UKSSD (LOCAL GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION) & (UK STAKEHOLDERS FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT). 2020. UN Sustainable development goals: A guide for councils. London: Local Government Association. [ Links ]

MAYOR OF LONDON. 2019. Draft London plan - Consolidated changes version. London: Greater London Authority. [ Links ]

MHCLG (MINISTRY OF HOUSING, COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT). 2018. National Planning Policy Framework, CM 9680. London: HMSO. [ Links ]

MHCLG (MINISTRY OF HOUSING, COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT). 2019. National Planning Policy Framework, CP 48. London: HMSO. [ Links ]

MHCLG (MINISTRY OF HOUSING, COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT). 2020. Planning for the future, White Paper. London: House of Commons Library. [ Links ]

RTPI (ROYAL TOWN PLANNING INSTITUTE). 2020. Measuring what matters, planning outcomes. Research report. London: RTPI. [ Links ]

SALFORD CITY COUNCIL. 2019. A fairer city. Revised draft local plan. Salford: Salford City Council. [ Links ]

SCHÖN, D. 1983. The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. London: Temple Smith. [ Links ]

SOUTHEND ON SEA BOROUGH COUNCIL. 2019. Southend issues and options document. [Online]. Available at: <https://localplan.southend.gov.uk/sites/localplan.southend/files/2019-02/Southend%20New%20Local%20Plan.pdf> [Accessed: 30 June 2020]. [ Links ]

TEWDWR-JONES, M. 2012. Spatial planning and governance: Understanding UK planning. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-01663-8 [ Links ]

TOWNSEND, I. & MACLEOD, A. 2018. Driving the Sustainable Development Goals agenda at the city level in Bristol. Bristol: Bristol Green Capital Partnership. [ Links ]

UC & LG (UNITED CITIES & LOCAL GOVERNMENT). 2015. The Sustainable Development Goals -What local governments need to know. Barcelona: UCLG. [ Links ]

UN (UNITED NATIONS). 2015. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: UN. [ Links ]

UK (UNITED KINGDOM) 2070 COMMISSION. 2020. Make no little plans, acting at scale for a fairer and stronger future. Sheffield: UK 2070 Commission. [ Links ]

UN-HABITAT (UNITED NATIONS HUMAN SETTLEMENTS PROGRAMME). 2020. Participatory incremental urban planning. Nairobi: UN-Habitat. [ Links ]

UKSSD(UK STAKEHOLDERS FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT). 2018. Measuring up: How the UK is performing on the UN sustainable development goals. London: UKSSD. [ Links ]

WELSH GOVERNMENT. 2019. Well-being of Wales 2018-2019. [Online]. Available at: <gov.wales> [Accessed: 22 November 2020]. [ Links ]

WILLSON, R. 2020. Reflective planning practice: Theory, cases, and methods. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429290275 [ Links ]

YORK CITY COUNCIL. Homepage. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.york.gov.uk/sustainability-1/one-planet-york-1> [Accessed: 30 June 2020]. [ Links ]

Peer reviewed and revised October 2020

Published December 2020

* The authors declared no conflict of interest for this title or article

1 Goal 16 identifies the importance of building effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.