Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Town and Regional Planning

versión On-line ISSN 2415-0495

versión impresa ISSN 1012-280X

Town reg. plan. (Online) vol.76 Bloemfontein 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp76i1.1

ARTICLES

Perceptions on corruption and compliance in the administration of town planning laws: The experience from Lagos Metropolitan Area, Nigeria

Persepsies oor korrupsie en nakoming van die administrasie van stadsbeplanningswette: Die ervaring van Lagos Metropolitaanse Gebied, Nigerië

Maikutlo mapabi le bobolu le bolateli tsamaisong ea melao ea thero ea litoropo: Liketsahalo Tsa Toropo ea Lagos, Nigeria

Adewumi I. Badiora

Dr Adewumi I. Badiora, Acting Head, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ibogun Campus, Ogun-State, Nigeria. Phone: 08077046603, Email: <wumibadiora@gmail.com>; <adewumi.badiora@oouagoiwoye.edu.ng> https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8740-3958

ABSTRACT

This article examines corruption in town planning practices and how this affects the reputation of local planning authority and residents' compliance with planning laws. This was examined using a sample of 362 participants from a systematic sampling survey conducted in Lagos metropolitan area, Nigeria. Findings show that the conduct of planning officers significantly influences residents' compliance with planning laws. Results also reveal that the use of procedural justice (fairness) in dealing with the public is extremely significant in building local town planning authority's reputation (legitimacy). The survey found that, if town planning officers act corruptly (in discharging their duties), the public will be disrespectful of planning laws and town planning authority. The structural equation model results show that certain socio-economic characteristics of residents significantly predict compliance with planning laws, independent of planning officials' corrupt behaviour. Specifically, compared to less educated residents, the more educated residents respect planning laws and view local planning authority as more legitimate. The article concludes that people are more satisfied with local planning authority or are more likely to voluntarily defer to planning laws when they view planning institutions as legitimate. A key component of this legitimacy is the use of procedural justice with the residents. The article suggests, inter alia, that local town planning authority and its officials need to become a democratically accountable institution, serving the public in a procedurally fair manner and without graft and bribery. Anti-corruption measures should be built into all planning systems as part of their structure. This article will contribute to urban and regional planning reform in Nigeria, with specific consideration for local planning authority, planning officials' accountability, and improvement of the relationship between town planning authority and the public.

Keywords: Corruption, local town planning authority, planning laws, procedural justice, town planning officials

OPSOMMING

Hierdie artikel ondersoek korrupsie in stadsbeplanningspraktyke en hoe dit die reputasie van die plaaslike beplanningsowerheid en inwoners se nakoming van beplanningswette beïnvloed. Dit is ondersoek aan die hand van 'n steekproef van 362 deelnemers aan 'n stelselmatige steekproefopname in die Lagos metropolitaanse gebied, Nigeria. Bevindinge toon dat die gedrag van beplanningsbeamptes beïnvloed beduidend inwoners se nakoming van beplanningswette. Resultate toon ook dat die gebruik van prosedurele geregtigheid (billikheid) in die omgang met die publiek uiters belangrik is in die opbou van die reputasie van plaaslike owerheidsbeplanning (legitimiteit). Die opname het bevind dat, wanneer die stadsbeplanningsbeamptes korrup optree (in die uitvoering van hul pligte), die publiek disrespekvol is teen beplanningswette en die stadsbeplanningsowerheid. Strukturele vergelyking model resultate toon dat sekere sosio-ekonomiese kenmerke van inwoners voorspel of hulle gaan voldoen aan die beplanningswette, onafhanklik van die korrupte gedrag van beplanningsamptenare. Spesifiek, in vergelyking met die minder opgeleide inwoners, respekteer die meer opgeleide inwoners die beplanningswette en beskou die plaaslike beplanningsowerheid as meer wettig. Die studie kom dus tot die gevolgtrekking dat mense meer tevrede is met die plaaslike beplanningsowerheid of dat hulle meer geneig is om vrywillig die beplanningswette te respekteer indien hulle die beplanningsinstelling as wettig beskou. Die gebruik van prosedurele geregtigheid by die inwoners is 'n belangrike onderdeel van hierdie legitimiteit. Die studie beveel aan dat die plaaslike beplanningsowerheid en sy amptenare 'n demokraties-verantwoordbare instelling moet word wat die publiek op 'n prosedureel billike manier dien, sonder omkopery. Maatreëls teen korrupsie moet in alle beplanningstelsels ingebou word as deel van die struktuur daarvan. Hierdie studie sal bydra tot die hervorming van stedelike en streeksbeplanning in Nigerië, met spesifieke inagneming van die plaaslike beplanningsowerheid, die verantwoordelikheid van beplannings-beamptes en die verbetering van verhoudings tussen die stads-beplanningsowerheid en die publiek.

Sleutelwoorde: Beplanningswette, korrupsie, plaaslike beplanningsowerheid, prosedurele geregtigheid, stadsbeplanningsamptenare

TUMELO

Sengodiloeng sena se lekola kammo bobodu tsamaisong le therong ea litoropo bo amang seriti sa batsamaisi, mmoho le kamoo baahi ba latelang melao ea thero ka teng. Boithuto bona bo entsoe ka ho hlahloba baahi ba 362 motse-moholo Lagos, Nigeria. Sephetho se fumane hore boitswaro ba batsamaisi ba toropo bo ama kamoo baahi ba latelang melao ea thero ea toropo ka teng. Se boetse se fumane hore seriti sa botsamaisi se ntlafatsoa ke ho hloka leeme le ho sebeletsa sechaba soohle ka toka. Boithuto bo fumane hape hore ha batsamaisi ba sebetsa ka bobodu le bomenemene, baahi le bona ha ba ikobele melao ea thero ea teropo mme ha ba hlomphe batsamaisi bao. Sephetho se boetse se fumane hore ka kakaretso baahi ba latela melao ea thero, le hoja batsamaisi bona ba bontsha bobodu. Ka kotloloho, papiso e bontsha ha baahi ba rutehileng ba latela melao ea thero mme ba tshepa botsamaisi ba toropo ho feta baahi ba sa rutehang. Boithuto bo qetella ka hore baahi ba khotsofatsoa ke batsamaisi, 'me ba latele melao ea thero ha mafapha a tsamaiso a sebetsa semolao. Taba e ka sehlohong ke hore mafapha a sebetseletse boohle ka toka. Ka hona, boithuto bo eletsa hore batsamaisi le liofisiri tsa thero ea litoropo ba lokela ho nka boikarabello bo phethahetseng ba demokrasi, mme ba sebeletse sechaba ka toka, ba nene tjotjo. Mekhoa ea ho thibela bobolu e lokela ho ahelloa ka hara meralo eohle ea thero ele karolo ea sebopeho sa eona. Boithuto bona bo kenya letsoho ntlafatsong ea thero ea litoropo naheng ea Nigeria, ka kotloloho khahlanong le bobolu ba liofisiri tse amehang, molemong oa likamano tse ntle le sechaba.

1. INTRODUCTION

In 2019, Nigeria was ranked 146th out of 180 countries (180 = most corrupt) surveyed by the corruption perception index (TI, 2019: online). Nigeria's rank from the survey shows that there is a lack of accountability and transparency from public officials, making corruptible acts more attractive and easier to get away with, within the country's public sector (Omonijo, Nnedu & Uche, 2013: 10). Urban and regional planning laws regulate the use and development of land in a particular area. In practice, this is usually overseen by local government planning authorities through planning regulations, development control instruments and the issuance of building permits. The local planning authority also ensures that permits are issued only when applicants comply with applicable laws and regulations. Furthermore, compliance inspections are usually carried out at various stages of a development to ensure that the development meets the conditions on which the approval was granted and any applicable laws and regulations that apply. This process, however, has been accused of corruption practices (Chiodelli, 2018: 1615). Bribery, fraud, favouritism, nepotism and abuse of public office by town planning officials are common forms of corruption allegations in the administration town planning laws (TI, 2008: 2).

According to the United Nations Department on Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA, 2011: online), between 40% (Nigeria) and 60% (Pakistan and India) of people who dealt with land services were asked to pay bribes. Results from an online survey in 2013 show that 88% of respondents indicated that it is impossible to obtain residential development permits without paying bribes. Such concerns about corruption in physical planning are also shared by commercial and business development (Zinnbauer, 2013: online). For instance, access to land and building permits has been rated as the most serious obstacle to business development in Nigeria (Adediran, 2017: 16) and in Russia (Kisunko & Cooldige, 2007: 10). It was reported that the Chinese authorities took action against local officials in as many as 168,000 illegal land and building permits deals in 2004 alone (Phan, 2005: 24). The current anti-corruption campaign in Lagos, Nigeria, uncovered thousands of illegal land and building matters in 2017 (Adediran, 2017: 12). Emerging data from helplines operated by Transparency International (TI) further confirm these findings when the majority of the anti-corruption complaints received were from urban areas. Corruption in tems of land issue was the main issue of complaints (TI, 2008: 6).

Over a quarter of public corruption cases reported by the news media in Italy are related to building development permits (Zinnbauer, 2015: online). Over 20% of corruption complaints received by the Australian Independent Commission Against Corruption in 2004 were related to corruption in terms of building and development, whereas close to a quarter of reported corruption cases in the United States of America (USA) were related to urban planning issues (Dodson & Coiacetto, 2006: 12).

In addition, a study on local level corruption in Spain found that 88% of all cases were related to urban planning (Jerez Darias, Martin & Gonzalez, 2012: 5). Survey data by TI in Nigeria suggests that 45% of all corruption cases dealt with paying bribes for development permit and land services (TI, 2008: 14-16).

Nigeria is ranked in the bottom quartile of all countries globally in terms of bureaucratic hurdles to registering land and buildings (Adediran, 2017: 16). Nigerian town planning authorities are unable to cope with demands and do not make fee information for registering land and buildings available through brochures, notice boards or online platform. Lagos metropolis, for example, received over 180,000 planning applications between 2005 and 2015, and was able to process fewer than 25% (Ministry of Physical Planning, 2015:3) The relationship between town planning officers and the public in Nigeria is at times troublesome (Badiora 2017: 2). Approval of developments and building plans sometimes deviates from the statutory requirements, as these are periodically done with hardly any or no regard for procedural fairness (Badiora, 2017: 2). It has been confirmed that, if the public adjudges an authority to use fair procedures, they would view the authority as being legitimate and would most likely comply with the laws (Hough, Jackson & Bradford, 2013: 348; Tankebe, 2009a: 1275; Bradford, Huq, Jackson & Roberts, 2014: 257; Jackson, Bradford, Hough & Zakar, 2014: 1077). When the public perceives or experiences unfairness, injustice, corrupt practices and abuse of authority and power during the exercise of institutional responsibilities, they are likely to disrespect such authority and become defiant, contemptuous and non-compliant with the laws (Jackson et al., 2014; Murphy, Bradford & Jackson, 2016: 191; Sunshine & Tyler, 2003: 533; Tyler, 2006: 388).

Currently, no existing studies have explored how perceptions of town planners' corruption affect Nigerians' cynicism towards the planning laws and local town planning authority/ institutions' reputation in Nigeria. It is, therefore, important to investigate the experiences and perceptions of town planning officials' corruption, and procedural (in)justice in planning administration, in order to understand whether public experience and/ or perceptions of town planning officials' corruption affect residents' compliance with planning laws and how these unethical behaviours affect the local town planning authority's reputation (legitimacy).

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

In order to understand corruption in town planning laws in Lagos, Nigeria, it is important to introduce the theory on planning corruption included in this article. The existing theory focuses on corruption in land-use planning; planning legislation and administration, as well as issues of compliance and cynicism towards the law in Lagos, Nigeria.

2.1 Corruption in land-use planning

While there is no universally agreed upon definition for corruption, Chiodelli and Moroni (2015: 444), the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) (2004: 2) and Nye (1967: 418) define corruption as the misuse of office and public power for private gain. This may include bribery (abuse of discretion in favour of a third party in exchange of benefits given by the third party); fraud (abuse of discretion for private gain without third parties' involvement); favouritism, nepotism, and clientelism (abuse of discretion not for self-interest, but for the interest of family, clan, political party, and ethnic group, among others (UN-Habitat, 2004: 2).

There are three main types of corruption in the planning industry: legislative and regulatory corruption; bureaucratic corruption, and public works corruption. Legislative and regulatory corruption refers to the ways in which and the extent to which legislators can be influenced. According to Chiodelli and Moroni (2015: 445), individuals or interest groups can bribe rule makers to introduce or revise regulations that can change the economic benefits associated with certain situations. Bureaucratic corruption refers to corrupt acts of the appointed bureaucrats in their dealings with the public, whereas public works corruption is the systemic graft involved in building public infrastructures and services. Individuals bribe bureaucrats either to speed up bureaucratic procedures or to obtain a service that is not supposed to be available (Chiodelli & Moroni, 2015: 445).

A report by TI (2013: online) states that, globally, 27% of the population interviewed admitted to having paid some forms of graft in the preceding twelve months, with a rise on the previous year in the majority of places worldwide. This concerns both the developed and the developing countries. Corruption costs the African continent economies over US$148 billion annually. This leads to a loss of 50% in tax revenue; increases the cost of African goods by as much as 20% and eats away 25% of Africa's GDP (De Maria, 2008: 325). Corruption is, therefore, negative not only because it clashes with the fundamental principles of fairness and respect for the rules, but also because it generates fallout. A prime example is the huge burden on the public purse. In Nigeria, for example, immediately after the President Muhammad Buhari Anti-Corruption Inquiry, the costs of public works plummeted by nearly one half. This gives an idea of the amount of money previously taken from the public coffers to the advantage of corruptors and the corrupted.

The phenomenon of corruption affects various areas of public activity, including the regulation and planning of land use. The majority of land services in sub-Saharan Africa is believed to take place off-budget, or is based on suspicious valuations (Fox, 2013: 11). At the heart of the problem is what is often referred to as a "development regulation crisis: as few as 30% of plots in developing countries are estimated to be formally registered" (Sioufi, 2011: 4). Insufficiently coordinated and recorded physical planning practices have, over decades or even centuries, created a patchwork of overlapping customary and statutory systems and conflicting claims, creating profound tenure insecurity, a dearth of reliable information on landownership, and a legal twilight zone that invites arbitrary administrative decisions and corruption (Magel & Wehrmann, 2002: 1-15). Arial, Fagan and Zimmermann (2011: 1-12) assert that corruption in the land sector can be generally characterised as pervasive. Government bodies that oversee the land sector are one of the public entities most plagued by service-level bribery. Cullingworth (1993: 23-27) stresses the same point in that the problem (of corruption) is particularly acute in land-use planning, where the opportunities are far greater than in other areas of public policy. According to the TI (2013: online) inquiry, 21% of the respondents who admitted to having engaged in corrupt transactions reported that the bribe was linked to 'land services', and 21% to 'registry and permit services' (this category includes, for example, building authorisation). Hence, it appears that a significant proportion of cases of corruption involve aspects of the planning domain.

So far, corruption has assumed a particularly salient role in the practice of urban planning administration in Nigeria. Recently, there have been widespread reports of town planning officials' corruption in Nigeria's news (Punch News February, 2016: online).

The chairman of the Senate fact-finding committee, Senator Dino Melaye, described the present situation as dangerous, and stressed the propensity of primitive mindsets of the people in Nigeria's corridors of power (politicians alike) who have disregarded the rule of law governing land development, the environment, and other metrics of modern cosmopolitanism (Punch News February, 2016: online). Against the backdrop of the realities of urban land development practices, Dodson and Coiacetto (2006: 1-25) note that, despite the scholarly attempts to comprehend the land development process in cities, planning scholars have deliberately or inadvertently ignored issues of corruption. This situation is peculiar, given the potential for corruption to occur either grossly or subtly in planning processes, which significantly affects all aspirations for urban development (Zinnbauer, 2013: online). Improper urban planning practices will aggravate inequalities, marginalise and undermine the livelihoods of the urban poor, increase the vulnerability to natural disasters, and undermine economic development and social relations (Zinnbauer, 2015: online).

2.2 Planning legislation and administration

Prior to the colonial period, physical planning was under the control of traditional rulers in Lagos (Oduwaye, 2009: 7). During the colonial period (1854-1960), the first physical plan for Lagos started with the 1863 revolutionary comment of Sir Richard Burton in his book on West Africa, in which he suggested steps to be taken to clear the "Lagos Stables", stating that "the site of Lagos is detestable". Shortly after making these comments (in 1873), the acting Colonial Surveyors gazetted that "[h]ouseholders and owners of unoccupied lands throughout the town are requested to keep the streets clean and around their premises as part of measures to ensure a clean environment in Lagos".

Between 1899 and 1904, MacGregor established a Sanitary Board of Health to advise the governor on many township-improvement schemes. The 1902 Planning Ordinance empowered the governor to declare some areas as European Reservations with a Local Board of Health of their own. In 1917, Township Ordinance No. 29 was enacted. This promulgation made Lagos the only city in Nigeria with a Town Council. The 1917 Township Ordinance did not allow for appreciable improvements of the traditional towns. This caused the disasters that led to the introduction of a planning ordinance to cover the native area of Lagos Island. The 1928 ordinance covers only the colony of Lagos, having established the Lagos Executive Development Board (LEDB), whose major task was to vet and approve building plans. In 1972, the LEDB merged with the Epe Area Planning Authority to form the physical planning authority of the Lagos State Development and Property Corporation (LSDPC). The LSDPC had the power to acquire, develop, hold, sell, lease and let any movable and immovable properties in the state.

The creation of Lagos state in 1972 brought about remarkable town planning efforts in the state. In 1973, the Lagos State Town and Country Planning Law, Cap. 133 was enacted, with the specific aim to assemble existing planning laws under the new Act. These were the Western Regional Law No. 41 of 1969; the Town and Country Planning Amendment Law; the Lagos Local Government Act of 1959-1964, Cap. 77; the Lagos Town Planning (Compensation) Act of 1964; the Lagos Executive Development Board (Power) Act of 1964; the Lagos Town Planning (Miscellaneous Provision) Decree of 1967; the Lagos State Town Planning (Miscellaneous Provision) Decree of 1967, and the Town Planning Authorities (Supervisory Power) Edict of 1971. Other town planning laws have been promulgated in Lagos State since 1973. These include the Town and Country Planning (Building Plans) Regulations, LSLN No. 15 of 1982; the Guidelines for Approval of Layout, LSLN No. 6 of 1983; the Town and Country Planning Edict of 1985, and the Town and Country Planning (Building Plan) Regulations of 1986.

All these laws have had various degrees of success and failure. The success is associated with the systematic development of some state-of-the-art accommodation for people, while the failure is associated with exploitation among development control agencies in their decision to process and approve development proposals. This act has spread to the officials who collect bribe in the name of processing fees (Vivan, Kyom & Balasom, 2013: 46). Among the problems mostly cited are unfair treatment and the unethical composition of the Lagos Executive Development Board (LEDB) membership; no proper monitoring of planning schemes, leading, in some instances, to allotees abandoning plots, and inadequate number of professional town planners in government service (Adediran, 2017:15). For instance, as provided by some of the Acts, particularly, the Town and Country Planning Edict of 1985, a town planning authority must have a minimum of four professionally registered town planners, in order to effectively provide the required leadership.

The 1998 Lagos State Urban and Regional Planning Edict No. 2 was formulated with the aim of improving these past planning legislations. It is also significant that this Edict was derived from the Nigerian Urban and Regional Planning Law Decree No. 88 of 1992. The most significant feature of the 1992 law is that it provides for a federal planning framework, by recognising the three tiers of government (local, state, and federal) as the basis of physical planning. The 1992 law empowers each level of government (federal, state, and local) with some specific planning responsibilities. In fact, this move brought planning closer to the people. Despite the commendable efforts of the Lagos State 1998 planning law, there are many emerging shortcomings. Some of these inadequacies are associated with the systematic development of innovative ideas, while others are associated with the unethical behaviour of the administrators and implementers of the laws (Oduwaye, 2009: 399). Among the problems mostly cited are unfair treatment of implementers of the provisions of the law and the unethical composition of the Lagos Planning Authority (LPA) board membership.

In order to address some of these shortcomings, the Lagos State Official Law No. 9 of 2005 was enacted for the 'Administration of Physical Planning, Urban and Regional Development, Establishment and Functions of Physical Planning and Development Agencies in Lagos State'. The promoters of the law based its emergence on the improvement of previous planning laws in Lagos State, especially the 1998 Lagos State Urban and Regional Planning Edict. Major highlights of the 2005 Lagos State Planning Law are the provision for the creation of an authority made up of the Lagos State Physical Planning and Development Authority; the Lagos Urban Renewal Authority, and any other agency, as may be established. The Lagos State Physical Planning and Urban Development Authority was responsible for all physical planning and urban development in Lagos State; the Lagos State Ministry of Physical Planning and Urban Development, when required, delegates specific responsibilities and functions related to implementation to the Authority. Among other provisions, the Ministry shall provide technical assistance to all government ministries and agencies on physical planning matters.

The latest planning legislation is the Lagos State Urban and Regional Planning Law 2010. In accordance with its provisions, the Ministry of Physical Planning has three parastatals: Lagos State Physical Planning Permit Authority (LASPPPA); Lagos State Building Control Agency (LABSCA), and Lagos State Urban Renewal Agency (LASURA). The ministry and its agencies ensure regeneration and exercise control over development, with a view to entrenching a liveable environment. One unique reform entrenched in the law is the establishment of the Building Control Agency (BCA) to ensure quality construction and safety in buildings. The effective implementation of this law is aimed at reducing the incessant collapse of buildings in the State (Adediran, 2017:17). Unfortunately, one year after the enactment of the law, BCA is yet to be properly established, and there are no regulations to drive the implementation of the building control activities. Consequently, in the absence of effective structure and regulations, one can hardly blame the untrained field officers' practices of extorting members of the public in the name of building control enforcement. A major obstacle to the implementation of the building control system in Lagos State is the unwarranted subjugation to planning control (Adediran, 2017: 17). The policy of making building control an enforcement arm of the planning office is unconventional and inconsistent with global best practices. Various formalisation efforts have proven rather ineffective and, in many instances, it has encouraged land grabbing, due to weak urban planning legislative structures and privileged access to the knowledge, means and mechanism of law (Benjaminsen, Meinzen-Dick & Mwangi, 2009: 46).

2.3 Issues of compliance and cynicism

Most of the empirical studies suggest that between 20% and 40% of public funds are lost to forms of corruption (TI, 2008: 9; Zinnbauer, 2015: online). Successive planning laws administrations have not been able to fully implement legitimately, accountably and publicly supported land-use planning for its citizens. The planning authorities' officials have used this loophole to act corruptly (Jeong, 2016). This unbound power allows unscrupulous elites to flout laws or manufacture them to their advantage in the first place. Bribery helps them defend and expand their privileges and avoid justice and collective responsibilities - all at the cost of the wider community (Zinnbauer, 2013: online). Nigerians have been informally encouraged not to trust the state and its laws, and by extension, the planning authority as one of the visible representatives of the government and executor of laws. This has led to a situation where people do not comply with planning laws and thereby become disrespectful to the local planning authority enforcing it (Badiora, 2017).

Just as a corrupt police force similarly fuels and does not curb violence and insecurity, which fatally undermine trust in the legitimacy of political institutions and the rule of law in Nigeria (Akinlabi, 2015: 422; 2016: 166), town planning officials' bias, favouritism and extent of unfair treatment of people continue to play crucial roles in explaining public distrust towards the planning law that has dragged the image of Nigeria's town planning authority in the mud (Badiora, 2017: 10; Adediran, 2017: 11). In addition, the local planning authority officials have historical records of corruption and the use of excessive unfair procedures in discharging their duties (Chiodelli & Moroni, 2015: 449). Consequently, they are regarded as corrupt officers. On many occasions, these officials have been accused of unfairness in dealing with citizens. Regrettably, from senior officers to the junior ones, there is an overwhelming evidence of bribery, cunning behaviour, and extortion (Chiodelli & Moroni 2015:452). There is a gross disparity between how these planning authority officials treat family, friends and influential members of society as well as those who are ready to bribe their way and how they respond to the general public (Badiora, 2017: 15).

Researchers have shown that, where there are strong indications of corruption, unfairness, procedural injustice and negative perceptions of authority's activities, people tend to be distrustful of the law (Jackson et al., 2014:1077; Tankebe, 2009b: 268). This is often referred to as legitimacy. Legitimacy is defined as "a property of an authority or institution that leads people to feel that that authority or institution is entitled to be obeyed" (Sunshine & Tyler, 2003: 522; Jackson & Bradford, 2010: 255). Legitimacy is linked to properties of the authority that lead people to feel it is entitled to be obeyed and it reflects a social value orientation toward institutions (Murphy & Cherney, 2012:199; Murphy & Tyler, 2008: 677; Tyler, 2011b: 26°). That is, people defer to, and obey an official directive by institutions (such as town planning authority), because they trust the institution's authority to make decisions and not because of the threat of sanction for disobedience.

The legitimacy of an institution comprises both instrumental and normative aspects. According to the instrumental perspective, such legitimacy is linked to instrumental evaluations of three elements: performance, risk, and judgements about distributive justice (Sunshine & Tyler, 2003: 532). This instrumental view suggests that a planning authority can increase support from the public when they effectively control development (performance), create a credible means of sanctioning those who do not comply with planning laws (deterrence), and fairly execute planning services across people and communities (distributive justice). The normative perspective of legitimacy comprises a number of aspects, the most important of which being procedural justice. Thibaut and Walker (1975: 2) coined the term 'procedural justice' to refer to people's perceptions of the treatment they receive during the processes involved in decision-making. Procedural justice is mostly concerned with making decisions based on fair procedures. It engenders support for authority when the public perceives that the procedures adopted by the officials of authority treat them with dignity and respect. In addition, people's satisfaction with the procedures and treatment used during the processes of decision-making were reported not to be solely dependent on the outcome of decision-making, as further studies have found that an authority's legitimacy is linked to people's satisfaction with the procedural justice aspects of their encounter with that authority (Lyn & Kristina 2007: 33; Tankebe, 2009b: 1287).

According to Tyler (2011a: 12-13), important factors that people consider when deciding if they have received procedural justice are whether they are treated fairly, whether they are treated with respect and dignity, and whether concerns are shown for their views. Therefore, an active participation (public participation) in discussions prior to town planning authority decision-making (i.e., people being given the opportunity to explain their views before planning officials decide on a course of action), planning authority decision-making that is neutral and objective (i.e., evidence that planning officials treat everyone in a like manner), and being treated with dignity and respect are key aspects of procedural justice in decision-making.

3. STUDY AREA

The city of Lagos, Nigeria, is located in the southwestern part of Nigeria, approximately between longitude 2°42'E and 3°42'E, and latitude 6°22'N and 6°52'. Lagos metropolis lies generally on lowlands, with roughly 18,782 ha of built-up area (see Figure 1). The Lagos metropolis is the business and industrial capital of Nigeria and is administratively divided into different local authorities. The population density is 13,405 individuals/km2. Lagos' population grew from the estimated 250,000 in 1854 to 600,000 in 1960 and from 5.3 million in 1995 to 9.3 million in 2006. In 2016, the population of the city of Lagos was 22.5 million (NBS, 2016: 14). Current demographic trends show that Lagos' population growth rate of 8% has resulted in its harbouring 36.8% (an estimated 60.8 million) of Nigeria's estimated 190 million urban populations (NBS, 2016: 14). The implication is that, whereas Nigeria's population growth is globally 2%, Lagos' population figure is growing ten times faster than that of New York (16.9%) and Los Angeles (13.3%). This has serious consequences for land-use planning in the State, especially in urban areas. The considerable geographical size and population density of the study area underscores the responsibility and the volume of work involved in the effective development control and physical planning and land services. Ironically, except for Abuja, Lagos is known as the best served urban area in terms of physical planning laws; yet the administration of physical planning law is most ineffective, due to high population and corruption (Adediran, 2017: 2).

For the purpose of land-use planning and administration, the Lagos built-up area is structured into 20 local town planning and land services authorities. Because of the volume of development and works and for the effective development control in the built-up area, the State government created an additional 37 local council development authorities (LCDAs) with all the characteristics and functions of the local town planning authorities.

4. METHODOLOGY

This study examines whether residents of the Lagos metropolitan area will comply or not with planning laws and regard local planning authority as a reputable institution if they perceive town planning administrators as corrupt public officials and/or have had actual or indirect experiences of planning officers' corruption and procedural (in) justice. Using a qualitative research design, a structured questionnaire survey set six constructs with 20 measures on the variables of corruption in planning law and administration extracted from literature. Bivariate correlation tests were used to assess relationships among these corruption variables (Carpenter, 2018: 1599). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to reduce these measured variables to smaller factors on corruption (Rossoni, Engelbert & Bellegard, 2016: 201). Structural equation model (SEM) was used to examine the influence of procedural justice, experience and perception of planning officers' corruption on cynicism towards planning laws and authority in Nigeria (Westland, 2015: 1).

4.1 Sampling size and methods

A multi-stage sampling technique was used in the selection of research participants (Ojewale, 2015: 7). In the first stage, the 16 local government areas (LGAs) within Lagos metropolis were stratified into low-, medium- and high-density areas. In this study, an LGA with a population of 20-10,000 individuals/ km2 is regarded as low density, while the medium and high densities have 10,001-20,000 individuals/ km2 and above 20,000 individuals/ km2, respectively. The simple random sampling technique was used to select Eti-osa, Ikeja and Mushin areas from the low-, medium- and high-density areas, respectively (Sharma, 2017: 750). In the second stage, the three selected LGAs were stratified into existing electoral wards as recognised by the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC). Information obtained from INEC showed that there were fourteen electoral wards in Mushin LGA, while Ikeja and Eti-osa LGAs have ten (10) wards each. One out of every four (4) wards in each LGA was selected through a simple random sampling without replacement. Thus, ten (10) political wards were surveyed. There were 15,275 residential buildings in the selected political wards, with 8,996, 3,780 and 2,499 in the high-, medium- and low-density areas, respectively. Systematic random sampling technique was adopted in selecting one out of every twenty buildings (5%). Using this method, a total of 768 buildings was sampled (Sharma, 2017: 750).

4.2 Data collection

The author and third-year students from the Joseph Ayo Babalola University, Ikeji-Arakeji, Nigeria, administered a face-to-face structured questionnaire survey to 768 residents in the study area from January to April 2016. Residents who had direct or indirect contact with planning officers were targeted. Where none of the members in the selected building had contact with planning officers, the next available building was sampled. Based on the literature review, constructs on corruption in the questionnaire included procedural justice that measured respondents' general views about the way in which town planning officials and vigilante corps generally make decisions and treat citizens; legitimacy that measured the reputation of town planning authority and the extent to which local town planning authority are seen to have legitimate authority; planners' corruption that assessed vicarious experiences of town planning officials' corruption and not the actual experiences of corruption; perception of planners' corruption that obtained data about residents' awareness or understanding of sensory information about land-use corruption; experience of planners' corruption that assessed actual experiences of corruption, and compliance/cynicism with planning laws that assessed distrust towards the planning laws and authority. A section on the respondent's profile obtained socio-demographic information on gender, education qualification, income level and ethnicity. The respondents were required to indicate their level of agreement, in practice, with the 20 measures defining corruption practices. The data from these measurements forms the variables used in the EFA and SEM, which tested the interrelationships among these factors. To reduce the respondents' bias, closed-ended questions were preferred (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2003: 232). This study upholds avoidance of harm, confidentiality and informed consent during data collection.

4.3 Response rate

From the 768 original questionnaires, 362 completed questionnaires were returned, resulting in a response rate of 47%. According to Baruch & Holtom (2008: 1153), average response rates for studies at organisational level are 37.2% and 52.7% at individual level.

4.4 Data analysis and interpretation of the findings

Data on the respondents' socioeconomic characteristics were analysed using descriptive statistics. The 20 corruption items were rated on a five-point Likert scale to measure the respondents' opinions (Leedy & Ormrod, 2014: 185).

The following scale measurement was used regarding mean scores, where 1 = Strongly disagree (>1.00 and <1.80); 2 = Disagree (>1.81 and <2.60); 3 = Neutral (>2.61 and <3.40); 4 = Agree (>3.41 and <4.20), and 5 = Strongly agree (>4.21 and <5.00). For analysis of the internal reliability of the items in the questionnaire, Cronbach's alpha values were tested with a cut-off value of 0.70 (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011: 54-55).

Bivariate correlation tests were applied to the data to show the comparative relationship between all six of the non-controlling independent variables (constructs) with test values between -1 (negative relationship), 0 (no relationship) and +1 (positive relationship) (Carpenter, 2018: 1600). EFA using principal-axis factoring with oblique rotation was conducted to test for the assumed conceptual differentiation between all six of the non-controlling independent variables (Osborne, 2015: 1).

The measured variables (control, non-controlling independent variables, and dependent variable) were subjected to a SEM. By using the structural equation model, the study was able to take an account of the interrelationships among all variables at once and ascertain the relative strength of predictor variables on the outcome variables of interest (i.e., 'legitimacy of planning authority' and 'non-compliance with planning laws'). In a structural equation model, all variables are simultaneously considered (Westland, 2015: 1).

4.5 Limitations

The study was not conducted across Nigeria; therefore, the findings cannot be generalised.

5. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

5.1 Respondents' profile

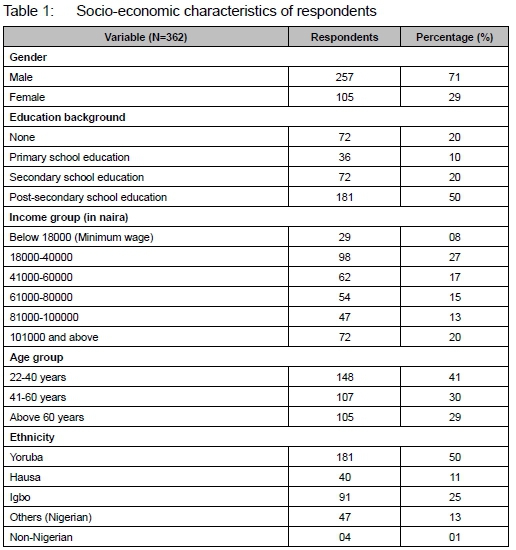

Table 1 displays the demographic profile of participants. The majority (71%) of the respondents were male, and Nigerian (99%). The majority (80%) of the respondents had formal education and 50% obtained a post-secondary school education. Only 8% of the respondents earned an average monthly income below the national minimum wage of N18000.00k (equivalent to US$50, as at April 2017), while 20% earned a monthly income above N100000.00k (US$278). Of the respondents, 41% were aged between 22 and 40 years, while 29% were above 60 years old. Of the residents of Lagos metropolis, 1% were non-Nigerians, while 99% were Nigerians distributed across major national ethnic groups (Hausa [11%], Igbo [25%] and Yoruba [50%]). Hence, the study area is cosmopolitan in nature, even though the Yoruba tribe still has the majority of residents.

5.2 Bivariate analysis

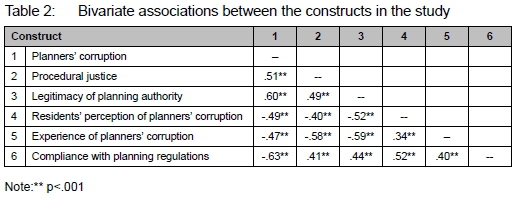

Table 2 shows the correlation coefficients results for relationships among the variables in the six corruption constructs. A negative correlation (r = -0.63) was found between compliance with planning regulations and planning officers' corruption. This suggests that residents' compliance with planning laws and regulations decreases with an increase in corruption practices among the planning officers. A significant negative correlation exists between compliance with planning laws and perceptions of planning officers' corruption (r = -.49) and experiences of planning officers' corruption (r = -.47). These findings show that residents who had experienced planners' abuse of office and those who perceived urban planners as being corrupt are more likely to disobey planning laws. Similarly, negative correlations were found between residents' perception of planning officers' corruption (r = -.52); experience of planning officers' corruption (r = -.59), and local town planning authority legitimacy. These results show that those who had experienced town planners' corruption and those who perceived town planning officers as being corrupt are more likely not to view physical planning authority as a legitimate institution.

Procedural justice had a positive correlation (r = .51) with residents' compliance with planning laws. To corroborate this, findings established negative correlations between residents' perception of planning officers' corruption (r = -.40), experience of planning officers' corruption (r = -.58), and procedural justice. These findings further show that those who perceived planning officers as corrupt and those who had experienced the town planners' bias will be more likely to take in that the planning officers do not use fair procedures. If the officials follow due procedure and treat people equally in their dealings with members of the public, people will comply with planning laws. Furthermore, residents who do not view the local planning authority as a reputable or legitimate institution are not likely to comply with planning. This was confirmed as a positive correlation (r = .44) established between compliance with planning regulations and legitimacy of planning authority.

5.3 Mean score and exploratory factor analysis

An overview of the MS of constructs on corruption in Table 3 shows that all the constructs have Cronbach's alpha greater than 0.70, indicating acceptable internal reliability, as recommended by Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson (2014). With mean score ratings above 3.5, respondents "agree" with all the corruption variables in the constructs: 'town planners' corruption'; 'experience of planning officers' corruption', and 'residents' non-compliance with planning laws'.

The 20 corruption non-controlling independent variables were subjected to EFA to study the trend of inter-correlations between variables and to group these variables with similar characteristics into a set of reduced factors. The results report the factor extraction, Eigenvalues, explained variance and correlation. In Table 3, using a cut-off value of initial Eigenvalues greater than one (>1.0), 5 factors explain a cumulative variance of 72%, where factor one explains 20% of the total variance; factor two (16%); factor three (12%); factor four (11%), and factor five (13%). Using principal-axis factoring with oblique rotation and significant factor of >0.30, Table 3 shows the correlation between constructs and variables after rotation. The only construct that did not appear to form its own separate factor was the perception of planning officers' corruption that loaded onto the experience of planning officers' corruption factor.

5.4 Structural equation model

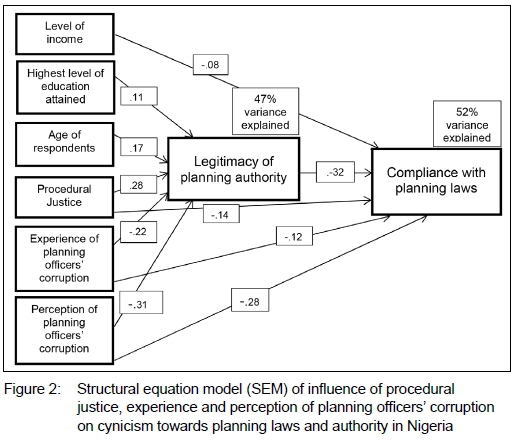

Figure 2 is a diagrammatic representation of the results of the SEM showing the influence of procedural justice, experience and perception of planning officers' corruption on cynicism towards planning laws and authority in Nigeria.

Using all variables and constructs included in this study, 47% of the variation in the reputation (legitimacy) of physical planning authority can be explained by five of the predictor variables, namely 'procedural justice', 'experience of planning officers' corruption', 'perception of planning officers' corruption', 'education level', and 'age of respondent' were significant predictors of local planning authority reputation (legitimacy). More specifically, respondents who were older and those who were more educated viewed physical planning authority as more legitimate (ß = 0.17, p <.001 and ß = 0.11, p <.001, respectively). People who believe the physical planning authority use procedural justice in their dealings with the public (ß = 0.28, p <.001) were more likely to regard physical planning authority as legitimate. Those who have experienced planning officers' corruption (ß = -0.22, p <.001), and those who perceived that planning officers are corrupt (ß = -0.31, p <.001) were more likely not to regard local planning authority as a reputable institution (legitimate). Of particular importance in this instance is that procedural justice (when planning officers treat people fairly) had a greater effect on physical planning authority reputation (legitimacy) than either of the two corruption variables (experienced planning officers' corruption and perception of planning officers' corruption), but only marginally so. This can be noted in the relative sizes of the ß values computed.

Of interest were the variables that predicted compliance with planning laws. A total of 52% of the variation in compliance with planning laws could be explained by five variables, namely 'legitimacy', 'procedural justice', 'experience of planning officers' corruption', 'perception of planning officers' corruption' and 'income level' significantly predicted 'compliance with planning laws'. Income level had a negative effect on compliance with planning laws (ß = -0.8, p <.03), suggesting that those with higher incomes were very likely not to comply with planning laws. Furthermore, experience of planning officers' corruption (ß = -0.12, p <.01) and perception that planning officers are corrupt (ß = -0.28, p <.001) had a negative effect on compliance with planning laws. However, people who were more likely to comply with planning laws believe that planning officers use procedural justice (fairness) when dealing with people (ß = 0.14, p <.001) and that local planning authority are a reputable (legitimate) institution (ß = 0.32, p <.001).

6. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

As the first research to apply procedural justice in the study of town planning practice in Nigeria, this study examined the pervasive problem of corruption in local town planning authority and how these unethical behaviours affect residents' compliance with planning laws and reputation of town planning authority in Nigeria.

The study analysed six constructs on the level of agreement with 20 factors influencing corruption in local town planning authority based on extant literature via a questionnaire requiring respondents to rate the factors as they were perceived. With mean score ratings above 3.5, respondents "agree" with all the corruption factors in the constructs: 'town planners' corruption'; 'experience of planning officers' corruption', and 'residents' non-compliance with planning laws'.

Correlation of the various factors influencing corruption shows that the association between compliance with planning laws, experience and perception of planning officers' corruption was entirely in the negative direction. This means that higher levels of planning officers' corruption predicted lower levels of compliance with planning laws in Nigeria. By contrast, the association between compliance with planning laws and procedural justice was positive. This connotes that a higher level of compliance with planning laws was associated with a higher level of procedural justice. In other words, the use of procedural justice or fairness by planning officers in dealing with the public is relevant in building positive perceptions of planning officers and the physical planning authority in Nigeria.

The structural equation model found that compliance with planning laws appears to be influenced more by the behaviour of planning officers. In this study, planning officers' corrupt behaviour had a negative effect on compliance. The model also suggests that procedural justice (fairness) is marginally more important in building physical planning authority's reputation (legitimacy). Hence, in Nigeria, people's perceptions of physical planning authority (legitimacy) are enhanced by procedural justice. Findings showed that physical planning authority's reputation or legitimacy influences the public's compliance with the planning laws. Legitimacy was found to be the single strongest predictor of compliance with planning laws. Corruption variables (experience and perception when combined) were the strongest predictors of compliance with planning laws in the model. It could, therefore, be inferred from the findings that most of the problems confronting physical planning practice in the study area could be due to corruption. Findings revealed that this societal anomaly, as a consequence, has negatively affected physical planning authority's reputation. This outcome calls for a serious examination of the current physical development control practices in Nigeria. Negative

perceptions of planning officers' activities, involvement in corrupt practices often engender scorn towards the planning laws and the physical planning authority enforcing it. In other words, corruption undermines public confidence in the physical planning authority and the reputation of the institution.

Policymakers in reforming the physical planning administration in Nigeria should motivate people to comply with laws or to cooperate with planning authority by developing better public participation. It is recommended that, in the long term, effective regulation by planning authority depends on their ability to gain consent and cooperation from the public. This study has shown that people are more satisfied with physical planning authority or are more likely to voluntarily defer to planning laws when they view planning authority as legitimate. A key component of this legitimacy is the use of procedural justice with the public. Physical planning authority have the opportunity to proactively enhance their reputation (legitimacy) and public participation by identifying in encounters with the public where existing practices and procedures could be enhanced, revised or implemented using procedural justice principles as basis.

For planning authority to control development and to gain public support, they need to become a democratically accountable institution, where their objective will be to serve the public in a procedurally fair manner and without bias. The Nigerian government should provide the enabling legislations for urban planning practice and enforcement of the laws to stop the current urban planning and development practices based on a weak legislative framework.

7. FUTURE RESEARCH

The present study did not address the influence of the physical planning system itself (the law and administrative procedures) on compliance and/or cynicism towards planning laws. Future studies should explore some of the principles and techniques (development rights, land rent, and formal equality in a quantitative version) that can be implemented to contain corruption at the outset of planning laws.

The influence of specific social characteristics such as, for example, gender and ethnicity, among others, on cynicism towards planning laws was not addressed in this study and could be explored in future analysis.

Using only a statistical analysis approach, this study presented a good sense of how end-users (residents) viewed the land-use planning practices and perceived systemic problems of planning practice in Nigeria. As there is no qualitative information available, the perspectives on the nature and extent of corruption (explanations and excuses, among others) from those working as planners or town planning officials in the Nigerian system should be considered in future research.

REFERENCES

ADEDIRAN, A. 2017. Dialectics of urban planning in Nigeria. 5th Urban Dialogue of the Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Lagos, 8 June. [ Links ]

AKINLABI, O. 2015. Young people, procedural justice and police legitimacy in Nigeria. Policing and Society, 27(4), pp. 419-438. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2015.1077836. [ Links ]

AKINLABI, O. 2016. Do the police really protect and serve the public? Police deviance and public cynicism towards the law in Nigeria. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 17(2), pp. 158-174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895816659906. [ Links ]

ARIAL, A., FAGAN, C. & ZIMMERMANN, W. 2011. Corruption in the land sector. Transparency International Working Paper, 4, pp. 1-12. [ Links ]

BADIORA, A.I. 2017. Issues in planning practice in Nigeria. First Urban and Regional Planning Students Association of Nigeria (URPSAN) Symposium (Ondo Chapter), 8-10 March, Wesley University Ondo. [ Links ]

BARUCH, Y. & HOLTOM, B.C. 2008. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Human Relations, 61(8), pp. 1139-1160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726708094863. [ Links ]

BENJAMINSEN, T, MEINZEN-DICK, R. & MWANGI, E. 2009. Formalization of land rights. Some empirical evidence from Mali, Nigeria and South Africa. Land Use Policy, 26(1), pp. 33-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.07.003. [ Links ]

BRADFORD, B., HUQ, A., JACKSON, J. & ROBERTS, B. 2014. What price fairness when security is at stake? Police legitimacy in South Africa. Regulation & Governance, 8(2), pp. 246-268. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12012. [ Links ]

CARPENTER, G.W. 2018. Simple bivariate correlation. In: Allen, M. (Ed.). The SAGE Encyclopedia of communication research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, pp. 1599-1601. [ Links ]

CHIODELLI, F. 2018.The illicit side of urban development: Corruption and organised crime in the field of urban planning. Urban Studies, 56(8), pp. 1611-1627. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018768498. [ Links ]

CHIODELLI, F. & MORONI, S. 2015. Corruption in land-use issues: A crucial challenge for planning theory and practice. Town Planning Research, 86(4), pp. 437-455. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2015.27. [ Links ]

COPINE (COOPERATIVE INFORMATION NETWORK). 2016. Images of some selected towns, cities and metropolises in Nigeria. COPINE Imagery Series, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. [ Links ]

CULLINGWORTH, J.B. 1993. The political culture of planning. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

DE MARIA, W. 2008. Cross-cultural trespass: Assessing African anti-corruption capacity. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 8(3), pp. 317-341. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595808096672. [ Links ]

DODSON, D. & COIACETTO, E. 2006. Corruption in the Australian land development process. Identifying a research agenda. In: Proceedings of the 2nd Bi-Annual National Conference on the State of Australian Cities, Brisbane 30 November-2 December. Brisbane: The Australian Sustainable Cities and Regions Network, pp. 1-25. [ Links ]

FOX, S. 2013.The political economy of slums: Theory and evidence from sub-Saharan Africa, Working Paper No. 13-146, Department for International Development, London School of Economics. [ Links ]

HAIR, J.F., BLACK, W.C., BABIN, B.J. & ANDERSON, R.L. 2014. Multivariate data analysis. 5th edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

HOUGH, M., JACKSON, J. & BRADFORD, B. 2013. Legitimacy, trust and compliance: An empirical test of procedural justice theory using the European Social Survey. In: Tankebe, J. & Liebling, A. (Eds). Legitimacy and criminal justice: An international exploration. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 326352. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198701996.003.0017. [ Links ]

JACKSON, J. & BRADFORD, B. 2010. What is trust and confidence in the police? Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 4(3), pp. 241-248. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paq020. [ Links ]

JACKSON, J., BRADFORD, B., HOUGH, M. & ZAKAR, M.Z. 2014. Corruption and police legitimacy in Lahore, Pakistan. British Journal of Criminology, 54, pp. 1067-1088. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azu069. [ Links ]

JEONG, J. 2016. Building booms and bribes: The corruption risks of urban development. Global Anti-Corruption Blog. Retrieved: 14 September 2017. [ Links ]

JEREZ DARIAS, L.M., MARTIN, V.O. & GONZALEZ, R.P. 2012. Aproximación a una geografia de la corrupción urbanística en Espana. Ería: Revista cuatrimestral de geografia, vol. 87, pp. 5-18. [ Links ]

KISUNKO, G. & COOLDIGE, J. 2007. Survey of land and real estate transactions in the Russian federation: Statistical analysis of selected hypotheses. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4115. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-4115. [ Links ]

LEEDY, P.D. & ORMROD, J.E. 2014. Practical research: Planning and design. 10th edition. Boston, MA: Pearson. [ Links ]

LYN, H. & KRISTINA, M. 2007. Public satisfaction with police: Using procedural justice to improve police legitimacy. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 40(1), pp. 27-42. https://doi.org/10.1375/acri.40.L27. [ Links ]

MAGEL, H. & WEHRMANN, B. 2002. Applying good governance to urban land management: Why and how? Zeitschrift fuer Vermessungswesen, 12(6), pp. 1-15. [ Links ]

MINISTRY OF PHYSICAL PLANNING. 2015. Lagos urbanization and physical development facts, No. 2015/3. Ikeja, Lagos, Nigeria. [ Links ]

MURPHY, K. & CHERNEY, A. 2012. Understanding cooperation with the police in a diverse society. British Journal of Criminology, 52(1), pp. 181-201. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azr065. [ Links ]

MURPHY, K. & TYLER, T.R. 2008. Procedural justice and compliance behaviour: The mediating role of emotions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38(4), pp. 652-668. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.502. [ Links ]

MURPHY, K., BRADFORD, B. & JACKSON, J. 2016. Motivating compliance behavior among offenders: Procedural justice or deterrence? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(1), pp. 102-118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854815611166. [ Links ]

NIGERIAN BUREAU OF STATISTICS. 2016. Estimated population growth rate of Nigeria. Abuja, Nigeria. [ Links ]

NYE, J.S. 1967. Corruption and political development. The American Political Science Review, 61(2), pp. 417-427. https://doi.org/10.2307/1953254. [ Links ]

ODUWAYE, L. 2009. Spatial variations of values of residential land use in Lagos Metropolis. African Research Review, 2(3), pp. 381-403. https://doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v3i2.43638. [ Links ]

OJEWALE, O.O. 2015. Socio-economic correlates of household solid waste generation: Evidence from Lagos Metropolis, Nigeria. Management Research and Practice, 7(1), pp. 44-54. [ Links ]

OMONIJO, D., NNEDUM, O. & UCHE, O. 2013. Social perspectives in the pervasiveness of endemic corruption in Nigeria. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, 1(2), pp. 1-26. [ Links ]

OSBORNE, J.W. 2015. What is rotating in exploratory factor analysis? Assessment, 20(2), pp. 1-8. [ Links ]

PHAN, P. 2005. Enriching the land or the political elite? Lessons from China on democratization of the urban renewal process. Pacific Rim Law and Policy Journal, 14(3), pp. 12-32. [ Links ]

PUNCH NEWS. 2016. 15 February. Distortion of Abuja mater plan. [Online]. Available at: <https://punchng.com/distortion-of-abuja-master-plan/> [Accessed: 3 February 2020]. [ Links ]

ROSSONI, L., ENGELBERT, R. & BELLEGARD, N.L. 2016. Normal science and its tools: Reviewing the effects of exploratory factor analysis in management. Revista de Administração, 51(2), pp. 198-211. https://doi.org/10.5700/rausp1234. [ Links ]

SHARMA, G. 2017. Pros and cons of different sampling techniques. International Journal of Applied Research, 3(7), pp. 749-752. [ Links ]

SIOUFi, M. 2011. Land and climate change in a new urban world. Urban World, 3(1), pp. 23-49. [ Links ]

SUNSHINE, J. & TYLER, T.R. 2003. The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law and Society Review, 37(3), pp. 513-547. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5893.3703002. [ Links ]

TANKEBE, J. 2009a. Public cooperation with the police in Ghana: Does procedural justice matter? Criminology, 47(4), pp. 1265-1293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00175.x. [ Links ]

TANKEBE, J. 2009b. Self-help, policing, and procedural justice: Ghanaian vigilantism and the rule of law. Law & Society Review, 43(2), pp. 245-270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5893.2009.00372.x. [ Links ]

TAVAKOL, M. & DENNICK, R. 2011. Making sense of Cronbach's alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, pp. 53-55. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd. [ Links ]

TEDDLIE, C. & TASHAKKORI, A. 2003. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioural research. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

THIBAUT, J. & WALKER, L. 1975. Procedural justice: A psychological analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

TI (TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL). 2008. Global Corruption Report. Water and corruption. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

TI (TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL). 2013. Global Corruption Barometer. [Online]. Available at: <http://www.transparency.org>. [Accessed: 12 April 2019]. [ Links ]

TI (TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL). 2019. Corruption Perceptions Index. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.transparency.org/cpi2019>. [Accessed: 12 April 2019]. [ Links ]

TYLER, T.R. 2006. Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimating. Annual Review of Psychology, 57(1), pp. 375-400. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190038. [ Links ]

TYLER, T.R. 2011a. Why people cooperate. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

TYLER, T.R. 2011b. Trust and legitimacy: Policing in the USA and Europe. European Journal of Criminology, 8(4), pp. 254-266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370811411462. [ Links ]

UN-HABITAT (UNITED NATIONS HUMAN SETTLEMENTS PROGRAMME). 2004. Tools to support transparency in local governance. Urban Governance Toolkit Series. Nairobi, Kenya: UN-Habitat. [ Links ]

UNDESA (UNITED NATIONS DEPARTMENT ON ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS). 2011. World urbanization prospects. New York, USA: UNDESA Population Division. [ Links ]

VIVAN, E., KYOM, B. & BALASOM, M. 2013. The nature, scope and dimensions of development control, tools and machineries in urban planning in Nigeria. International Journal of Innovative Environmental Studies Research, 1(1), pp. 48-54. [ Links ]

WESTLAND, J.C. 2015. An introduction to structural equation models. In: Structural Equation Models: From Paths to Networks. Studies in systems, decision and control series, vol. 22. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, pp.1-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16507-3_1. [ Links ]

ZINNBAUER, D. 2013. Cities of integrity: An overlooked challenge for both urbanites and anti- corruption practitioners and a great opportunity for fresh ideas and alliances. SSRN Journal. [Online]. Available at: <http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2288558>. [Accessed: 30 May 2018]. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2288558. [ Links ]

ZINNBAUER, D. 2015. Towards an urban land resource curse? A fresh perspective on a long- standing issue. SSRN Journal. [Online]. Available at: <http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2689236>. [Accessed: 30 May 2018]. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2689236. [ Links ]

Peer reviewed and revised November 2019

The authors declared no conflict of interest for this title or article