Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Town and Regional Planning

On-line version ISSN 2415-0495

Print version ISSN 1012-280X

Town reg. plan. (Online) vol.75 Bloemfontein 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp75i1.8

ARTICLES

Adaptive resistance amidst planning and administrative failure: The story of an informal settlement in the city of Kitwe, Zambia

Aanpasbare weerstand te midde van beplanning en administratiewe mislukking: die verhaal van 'n informele nedersetting in die stad Kitwe, Zambië

Khanyetso ea phetoho nakong ea ho hloleha hoa thero le tsamaiso: pale ea motse oa baipehi toropong ea Kitwe, Zambia

Ephraim Kabunda Munshifwa

Dean of the School of the Built Environment, Copperbelt University, Department of Real Estate Studies, P.O Box 21692, Kitwe, Zambia. Phone: +260 966626916, e-mail: <kabunda.munshifwa@hotmail.com>; <ephraim.munshifwa@cbu.ac.zm>

ABSTRACT

Informal settlements often emerge, due to rapid urbanisation or failure of urban systems, with negative resultant effects. Such settlements are viewed as a blight to the beauty and order of modern cities, attracting demolition threats from local authorities. Despite the use of force through demolitions and evictions, a number of these settlements have grown to a point where many have attracted upgrading initiatives rather than demolition. Hence, they have become permanent features of the vast majority of cities in the Global South. This study poses the question: How do these settlements transcend serious threats to their existence and still consolidate and grow? The study found that the answer lies in their adaptive resistance capacity. As settlements resist eviction, they also adapt rules from formal systems, in order to minimise their negative image. As a result, with time, conditions improve within the settlements. The study used Mindolo North informal settlement in the city of Kitwe as a case study to examine mechanisms through which informal settlements emerge, consolidate and grow.

Keywords: Adaptive, resistance, informal settlements, planning, Zambia

ABSTRAKTE

Informele nedersettings kom dikwels voor as gevolg van vinnige verstedeliking of die mislukking van stedelike stelsels, met negatiewe gevolge. Sulke nedersettings word gesien as 'n problem vir die skoonheid en orde van moderne stede, en lok slopingsdreigemente vanaf plaaslike owerhede. Ten spyte van die gebruik van geweld deur sloping en uitsettings, het 'n aantal van hierdie nedersettings gegroei tot 'n punt waar baie opgraderingsinisiatiewe eerder as sloop gelok het. Hulle word dus permanente kenmerke van die meeste stede in die Globale Suide. Hierdie studie vra: Hoe oortref hierdie nedersettings ernstige bedreigings vir hul bestaan, en konsolideer en groei hulle nog steeds? Die studie het bevind dat die antwoord in hul aanpasbare weerstandskapasiteit lê. Aangesien nedersettings die uitsetting weerstaan, pas hulle ook reels van formele stelsels aan om hul negatiewe beeld te verminder. As gevolg hiervan verbeter toestande binne die nedersettings mettertyd. Die studie gebruik Mindolo Noord informele nedersetting in die stad Kitwe as gevallestudie om meganismes te ondersoek waardeur informele nedersettings ontstaan, konsolideer en groei.

Sleutelwoorde: Aanpasbaar, weerstand, informele nedersettings, beplanning, Zambië

TUMELO

Metse ea baipehi e tlisoa ke kho'lo ea libaka tse mabalane kapa ho se atlehe hoa tsamaiso ea ntlafatso ea litotopo. Metse ena e nkoa e senya bokhabane le botle ba litoropo tsa kajeno, 'me hona ho susumetsa baetapele ho lohotha ho senya metse ena ea baipehi, kapa hona ho leleka baahi ba eona. E meng ea metse ena e holile haholo hoo ho bang thata ho e senya kapa ho leleka baahi ba eona, mme qetelong baetapele ba e ntlafatsa, 'me kahona eba metse e tsepameng litoropong tse ngata selikalikoeng se ka Borwa. Potso ea manthla ea boithuto bona e bile hore na ke eng e susumetsang metse ea baipehi ho hola le ha hona le litshoso tsa ho e senya? Karabo e fumanoeng ke hore baahi ba metse ena ba na le bokgoni ba ho fetola khanyetso. Ke hore, ha baahi ba loanela ho se lelekoe, ba sebelisa melao e teng ea lefatshe, mme sena se thusa hore metse ea bona ebe le seriti. Ka lebaka lena, ha nako e ntse e ea, maemo a metse ea baipehi a fetoha. Boithuto bona bo entsoe motseng oa baipehi oa Mindolo, toropong ea Kitwe, molemong oa ho lekola lisusumetso tse tlisang motheo, kopa-kopano le kgolo ea metse ea baipehi.

1. INTRODUCTION

Stories of the emergence, consolidation and growth of informal settlements take many forms in the Global South. Despite each of these settlements having its own unique history, literature ascribes their existence either to rapid urbanisation or to failure of urban systems, particularly planning failure (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe [UNECE], 2009; Sori, 2012; UN Habitat, 2015; Masimba, 2016; Sakala, 2016; Marutlulle, 2017). Viewed mostly as a blight on the beauty and order of modern cities, informal settlements are often regarded as a disease to be eradicated. As a result, a number of studies are titled 'causes of informal settlements' (see, for instance, Ali & Sulaiman, 2006; UNECE, 2009; UN Habitat, 2015; Masimba, 2016; Sakala, 2016; Marutlulle, 2017). The major causes cited in these studies include population growth, rapid urbanisation, poverty, rural-urban migration, lack of access to land and ownership, and weak urban governance (in terms of policy, planning and land/urban management). Growth of informal settlements is then said to cause a number of socio-economic problems such as pollution, deforestation, flooding, and wastage of agricultural land (Ali & Sulaiman, 2006: 1).

However, besides failure by local authorities to cope with rapid urbanisation, a number of other studies point to informal settlers' resistance and ability to adapt as reasons for the existence of the vast majority of informal settlements. For instance, Skuse and Cousins (2007: 979) framed 'resistance' as the 'struggle' for urban permanency. The study used the settlement of Nkanini in Cape Town to examine the "bitter struggle between residents and local City of Cape Town authorities over claims to occupy the land" (Skuse & Cousins, 2007: 979). Fitchett (2014: 355) used a similar concept called 'adaptive co-management' to argue for the appreciation of local knowledge systems and social structures when confronting challenges of informal settlements. The study used Diepsloot, an informal settlement in the City of Johannesburg, as a case study. Adaptation can, therefore, be regarded as the ability to change internal organisational structures within informal settlements, in order to conform to what the authorities demand. This ability or characteristic is displayed in an environment of constant threats of demolition from authorities, hence the use of 'adaptive resistance', for this study.

It is, therefore, clear that informal settlements can also be viewed from other perspectives. What can we learn about the internal mechanisms of these settlements in terms of mobilisation and organisation? How do they manage to keep growing amidst serious threats from authorities? This article argues that, although resistance is a key tool in ensuring that settlements grow, residents are aware that the state of any such settlement is often one of its major weaknesses. As a result, residents of informal settlements tend to copy ideas from planned areas, in order to improve layout and development outcomes in some form of 'adaptive resistance'. This article examines the case of an informal settlement north of Mindolo North Municipal Township in the city of Kitwe, Zambia, simply referred to as Mindolo North informal settlement, which has gone through a number of waves of threats of demolition, despite its continued growth. Coupled with resistance, the settlement seems to be improving, by trying to increasingly resemble part of existing areas in its immediate vicinity and be accepted as such. The question then is: Why and how is it that the settlement is still growing amidst intense threats from authorities? What are the internal mechanisms that enable the settlement to adapt?

This article is pitched from an institutional economics perspective, which argues that each community has a way of organising itself through both formal and informal rules. 'Rules' from this perspective are defined as "rules of the game" (North, 1990: 3), the role of which is to constrain or enable human action in a particular environment. In the context of this article, informal settlements will emerge and organise around informal rules in an environment of weak formal rules. Thus, a vacuum in formal rules does not necessarily mean chaos and disorder; it also creates a space for informal rules to emerge and consolidate. In this sense, institutions provide the incentive structure within which human beings operate. The case of Mindolo North informal settlement becomes an ideal environment for exploring this theoretical perspective.

2. RESISTANCE AND ADAPTATION AS A TOOL FOR GROWTH

A number of studies (Akhmat & Khan, 2011; Msimang, 2017) have focused on the negative side of informal settlements and the need for their upgrading. However, this article argues that these settlements have grown through a process of resisting evictions and adapting to new information, in order to better organise internal activities and achieve better outcomes. It is noteworthy that similar terms have been used to refer to growth of informal settlements, such as "adaptive processes" (Jones, 2017: 6), "self-perpetuating" or "self-planned" (Akhmat & Khan, 2011: 56), and "self-organisation" (Eizenberg, 2018: 40), to describe processes where various actors and organisations undertake development independent of the State. A similar view is discussed in De Beer and Oranje (2019: 12), where it is argued that resistance and reconstruction from 'small communities' should be understood as an alternative to the 'top-down' approach in planning. In other words, De Beer and Oranje (2019: 12) advocate for making cities 'from below', similar to the 'bottom-up' approach discussed in Jones (2017: 6).

Resistance to eviction by the State can also be understood within an older concept of 'right to the city' by Henri Lefebvre (1996: 7) in 1968. This concept is both an idea and a slogan and is defined as "a demand ... for a transformed and renewed access to urban life". It thus falls within urban theory that describes the phenomenon of city formation. The reality, especially in the Global South, is that not all land within the jurisdiction of a municipality is clearly assigned a use and user, such that portions of land remain as public land or simply 'free'. In the advent of rapid population increase and urbanisation, coupled with weak planning and administrative structures, this land becomes the battle ground for the less privileged and neglected of society who also lay claim to the city (Lefebvre, 1996; Attoh, 2011; Fieuw, 2011; Purcell, 2014).

Local authorities are often cited in many cases of planning failure (Mabogunje, 1990; Massey, 2013; UN Habitat, 2013). A key reason for this accusation is that planning authorities have the mandate to prepare the development plan of a city or region and coordinate its implementation. One of the main activities in the implementation is monitoring development to ensure that the plan is executed as desired. However, by their nature, informal settlements are unplanned, meaning that they emerge and grow outside planning regulations. Literature often attributes the causes of informal settlements in most of the cities in the Global South to failure of planning rules. It should, however, be noted that planning rules are themselves institutions - formal institutions (Lai, Lorne, Chau & Ching, 2016: 230). Their role is to "enable or constrain" human action in the growth of cities. Because of failure of planning theory based on assumptions in a western environment, some scholars have started advocating for a different perspective in planning, one that takes into consideration specific characteristics of the Global South (Watson, 2014: 23). A case in point was the upgrading of Makhaza and New Rest informal settlements in Cape Town, which Massey (2013: 609) argued did not meet the needs of settlers with regard to their livelihood strategies. Similar thoughts were expressed earlier by Huchzermeyer (2004: 334) who argued for an approach that first looked at protecting residents' constitutional rights before acting on the contravention of property and land-use laws.

Despite the absence of planning rules that accommodate them, marginalised communities will often And a way to 'mobilise' and organise, using a mixture of social norms and borrowed planning rules. Notwithstanding their seemingly chaotic appearance, the internal arrangements of these informal settlements are often organised and orderly through some form of "social ordering" (Nkurunziza, 2007: 509) defined as a "distinct pattern of organising society" (North, Wallis, Webb & Weingast, 2009: 2). Informal acquisition of land has thus been listed among various ways of land delivery in the vast majority of cities; others being allocation of public land, purchase through the land market, delivery of customary land through state-sanctioned means, delivery of customary land to members of a group, allocation by officials (usually political official), and purchase of customary land (Rakodi & Leduka, 2004: 1).

A number of studies show that self-organising systems rely on structural principles, which help coordinate activities in the absence of the State (Giddens, 1984; Fuch, 2003). These are similar to principles used for the initial organisation of development activities in informal settlements. For instance, Munshifwa and Mooya (2016a: 480) argued for 'facilitative interaction', defined as the constant engagement between formal and informal structure, as an important element in the consolidation of growth in informal settlements. The constant adaptation of these structural principles contributes to improved coordination and outcomes in these settlements. To understand the various developmental stages through which informal settlements grow, studies have identified at least three main stages, namely infancy, consolidation, and maturity (Sliuzas, Mboup & de Sherbinin, 2008; Sori, 2012). These stages are then linked, at a point in time, to specific outcomes such as building construction (size, materials, shape), nature of other objects

(roads, health and other social facilities, open space), site conditions (location in the urban areas, slope, vegetation, natural hazards), and the slum development process. 'Infancy' is defined as the initial occupancy stage, during which public amenities and services are non-existent (Sori, 2012: 5). The consolidation stage is the intermediate stage, which sees fast expansion of the settlement, while intensifying on construction (Sori, 2012: 5). 'Maturity' or 'saturation' is the point at which the land expansion stops, while intensification on the settlement increases (Sori, 2012: 6). Although Sliuzas et al. (2008) and Sori (2012) concentrated the definitions on land coverage and intensity, these stages can equally be linked to changes over time in other development outcomes.

This article hypothesises that the key ingredient in moving from one stage to the next is the settlers' amount of resistance and adaptive ability. This is then reflected in changes over time in development outcomes such as building construction, accessibility, and provision of health and other social facilities. The informal development process is then underpinned by a local institutional structure of rules and organisations (Figure 1), similar to the one perceived by Fitchett (2014).

3. STUDY AREA

Mindolo North informal settlement (Figure 2), first established in 1979, is situated on the northern end of Kitwe as an extension to Mindolo North Municipal Township. At the time of the 2014 study, the settlement was still in its formative state or infancy, with raging public debates on whether it should be allowed to exist or not. It covered an approximate area of 62 hectares with an estimated population of 3 000 and 550 households, giving it a population density of 48 people per hectare and household density of 5.5 persons per household. During the survey, it was found that Mindolo North consisted of two distinct spatial areas, namely Mindolo North Municipal Township and Mindolo North informal settlement. The latter also had two sections. The first section was the area closest to the formal township, where land was allocated by Mindolo Ward Residents Development Committee (RDC), and the latter section was either allocated by political officials during the 2010/2011 election campaigns or self-allocated (invaded) by residents on public and private land. Property rights in the area are thus informal. Where necessary, this distinction will be used during data presentation and analysis, in order to provide more insight into the differences in perception between those allocated by RDC and the rest of the residents.

From 2008 to 2018, residents of the settlement experienced numerous clashes with the law. Threats of eviction are omnipresent, as the Kitwe City Council (KCC) makes several incursions into the area to demolish structures. During the time of the household survey (April 2014), the local authority issued threats via radio, television and print media to demolish the settlement. The local authority contended that 3 000 plots were sold illegally in Mindolo North and that 8 people had been arrested as a result of such illegal sales (The Zambian, 2014). By 5 June 2014, 32 residents had been arrested (Lusaka Times, 2014),1over 600 housing structures were demolished by the local authorities, and residents relocated. The current status is that these houses have been rebuilt and the settlement has grown beyond the 2014 boundaries. Many new houses have been erected, including the use of more permanent building materials, thus showing evidence not only of resistance, but also of adaptation.

4. RESEARCH

Literature (Rakodi & Leduka, 2004; Nkurunziza, 2007; Nassar & Elsayed, 2017) points to a shift not only in accepting informal settlements as part of the reality in most of the developing countries, but also that their way of organising may be useful. It is, therefore, important that, in the process of helping these settlements improve, authorities do not 'throw out the baby with the bath water'. This study focused on understanding the operations of internal mechanisms within these settlements with regard to the initial

set-up of the settlement, rules of plot arrangements, sizes and allocation, and the implementation and control structure used. The case study of Mindolo North informal settlement was selected for investigating these mechanisms, including specific measurable parameters of land coverage, house completion, and promises of property rights and documentation. It combines quantitative data (survey questionnaires) and life story experiences of settlers (interviews) to examine tangible development outcomes.

4.1 Data collection

Data for this article was collected as part of a bigger research project. The project was a comparative study of three settlements in Kitwe (Figure 2), namely Mindolo North informal settlement (illegal settlement), Chipata (semi-legal settlement), and Ipusukilo (a legalised settlement) (Munshifwa & Mooya, 2016a; 2016b).

First, household surveys were undertaken over a period of seven months (from January 2014 to August 2014). Households were selected based on random sampling whereby the interviewers skipped two houses in between; that is, every third house was selected. The surveys were targeted at heads of households, although in the absence of husbands in male-headed households, wives were interviewed instead. The collection of data involved the administration of 704 questionnaires, comprising 152 for Mindolo North, 271 for Chipata, and 281 for Ipusukilo. The survey questionnaire consisted of Ave sections. Section one obtained biographical data; sections three to Ave set pre-set tickbox questions on physical and infrastructure developments; property rights and acquisition; property market information, as well as property contracts and enforcement.

In order to understand the deep-seated beliefs, norms and customs, with specific focus on property rights, mechanisms and processes, as well as the interaction between formal and informal systems, in-depth semi-structured interviews were held in the three settlements in November 2014 (Bryman, 2004). These interviews were conducted with 10 officers from KCC and 24 residents in the three settlements (8 per settlement who had lived in the settlement for at least 5 years). Thus, a total of 34 individuals were interviewed. In-depth interviews targeted senior residents and local officials such as chairmen, RDC officials and Block secretaries, who were able to recount the genesis and growth of these settlements. The interview schedule consisted of 15 open-ended questions with the aim to understand the KCC's role in the physical development of these low-income settlements and to obtain the life histories of residents from the point of settling in the settlement to the present day.

Secondary data was also collected from published and unpublished documents.

4.2 Sample size

In Mindolo North informal settlement, with an estimated population of 3 000 people, a sample size of 704 people completed questionnaires. The Krejcie and Morgan (1970: 608) table for sample size formulas indicates that, for a population equal to or over 3 000, a sample size of 704 is valid.

4.3 Data analysis and interpretation of findings

The SPSS computer program was used for analysis of the 2014 socioeconomic characteristics of Mindolo North informal settlement, where the percentages of responses were reported. The Somers' d test was used to measure the existence of (P-value) and how strong (R-value) the relationships were between the socio-economic characteristics and development outcomes (Newson, 2002: 46). Somers' d uses a scale from -1 to 1, where 1 signifies a perfect positive relationship, -1 signifies a perfect negative relationship, and 0 signifies no overall ordinal relationship.

Content analysis (selective coding) was used to analyse and group components that support development outcomes mentioned in the in-depth interviews (Table 2). To understand the changes in development outcomes, the 2014 survey results, as a basis for understanding socio-economic characteristics of Mindolo North informal settlement, were compared to the 2018 survey results of the KCC.

5. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

5.1 Socio-economic characteristics of the respondents

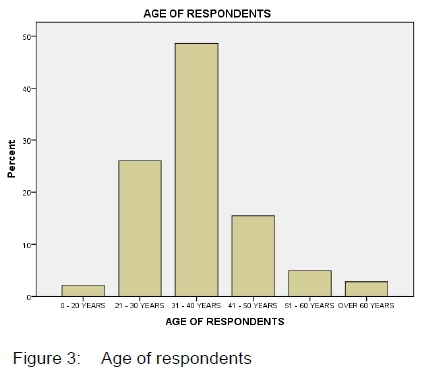

The study was perceived with the understanding that socio-economic factors partly impact on the ability of residents to compete in the formal market, thus resorting to settling in informal settlements. The survey revealed (Figures 3 to 6) that 35% of the respondents were male and 65% were female. Out of these, 89% were "owners" and 11% tenants. In terms of age, the study revealed that 47% of the respondents were aged between 31 and 40 years.

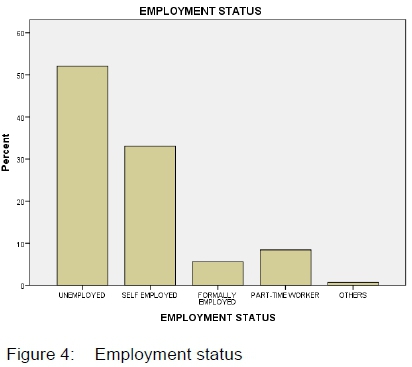

Cumulatively, 77% were aged 40 years or below. This implies that most of the residents are young, and possibly also unemployed. Further investigations confirmed that 52% were unemployed and 33% were self-employed; a cumulative total of 85%. The study found that only 6% were formally employed.

The Somers' d measure was used for ordinal-level data to further explore this relationship. The results showed a weak positive relationship with a value of 0.042, using age as a dependent variable. For Mindolo North informal settlement, this result implies that the vast majority of the unemployed people in the settlement are young; most of them are aged below 40 years and unemployed/ self-employed (Figures 3 and 4). This further means that providing gainful employment for young people will empower them in such a way that they would be able to pay for plots through a legitimate process of land acquisition.

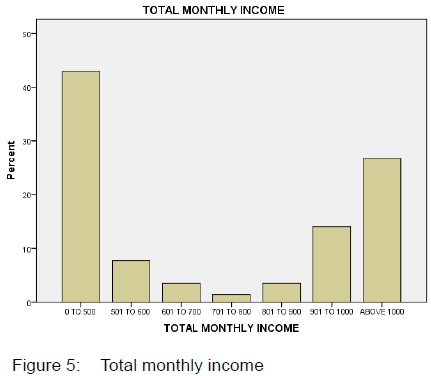

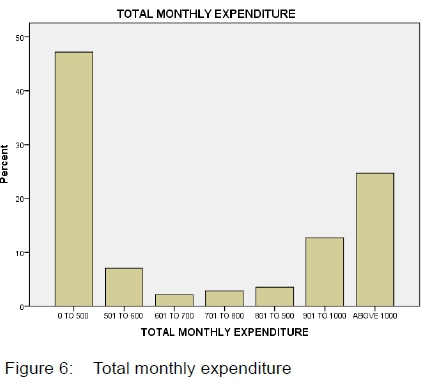

The analysis of income and expenditure strengthens the above findings. Statistics showed that 47% of the respondents earned K5002 or less per month, thus confirming the low-income status of residents in the informal settlement (Figures 5 and 6). Similarly, 46% of the respondents earned K500 or less. The level of income is also reflected in expenditure statistics, showing that the majority of the respondents spent K500 or less.

5.2 Changes in development outcomes

The emergence and growth of Mindolo North informal settlement can be analysed within three phases: prior to 2011 (mostly allocated by the Resident Development Committee [RDC]); from 2011 to 2013 (allocated by Movement for Multi-party Democracy [MMD] officials), and post-2013, mostly through self-allocation.

As argued by Nkurunziza (2007), Munshifwa and Mooya (2016a), informal mechanisms developed within informal settlements to provide the structural principles upon which they emerge and grow. This article focuses on developments as outcomes of these structural principles (Giddens, 1984; Fuch, 2003). Despite their origin, informal settlements are argued to provide services, including self-planning or organisation, in the absence of the State. Other tangible outcomes are also noticeable in these settlements which have a relationship with strengthening possession/ rights on land. For instance, this is noted in the change of building materials from temporary to more permanent, as one moves from the newly settled (infancy stage) to the old (maturity stage); emergence of a land and property market and some form of order in plot sizes and layout. With this in mind, the remainder of this article compares findings of the 2018 survey by KCC, against development outcome noted during the 2014 survey. Three main parameters, namely land coverage, house completions, and promises of property rights or documentation, are isolated for this comparison. Besides these three main parameters, findings from in-depth interviews of 2014 highlighted the local institutional and organisational structures as the underpinning support for current development outcomes.

5.2.1 Land coverage

Occupation and development of land in Mindolo North informal settlement can be categorised into three main parts (see Figures 7 and 8), namely Block A (allocated by the RDC and can rightly be called "matured"); B (allocated by ruling party officials and in the consolidation stage), and C (self-allocated and still in its infancy). Block A is the initial occupation and covers an approximate area of 47 hectares. Some settlers have been in this area for over 26 years. However, in the advent of the 2011 presidential and parliamentary elections, Mindolo North experienced a second wave of occupation spearheaded by ruling party officials. This area covers approximately 86 hectares. These two parts were separated by a large graded road. Much of the demolitions of June 2014 affected Block B and a small part of Block C. The 2014 survey reviewed that 4% of the settlers were allocated by RDC officials, 21% by ruling party officials, and 75% simply squatted on vacant land.

The September 2018 survey by KCC revealed a growing Mindolo North informal settlement. After the 2014 demolitions, the settlement experienced a third wave of occupation (mainly comprising Block C), such that, by 2018, much of the remaining private land of approximately 114 hectares had been covered (Figure 8).This has brought the total occupied land to 260 hectares. This area was initially planned for the development of a USD200 million Copperbelt City Mall by TGP Properties Limited, a joint venture between HBW Group of South Africa and Phoenix Materials of Zambia.3 While it can be argued that this increase in land coverage can be attributed to laxity by monitoring and enforcement agencies responsible for settlement administration and planning, the resistance of settlers has also played a big part.

5.2.2 House completions

The 2014 survey reported that 550 plots were at various stages of development, with 440 fully developed. However, the 2018 survey by KCC revealed that 581 houses are complete (an increase of 32%), 597 are incomplete and built to window level, while another 673 are at foundation level. KCC further revealed that 1 477 plots remain undeveloped, bringing the total number of plots in the area to 3 328, an indication of a rapid construction rate between 2014 and 2018 (Table 1). Although population figures were not yet available at the time of the 2018 survey, this article argues that extrapolating the population using the household density of 5.5 per household (Table 1) would show that Mindolo North informal settlement will have a total population of approximately 17 500 when fully settled, making it one of the largest informal settlements in Kitwe.4 This increase in the number of completed houses confirms the increase in land coverage discussed in 5.2.1.

5.2.3 Property rights and documentation

The rapid rate of occupation in Mindolo North can also be attributed to promises of official offer letters by the Council to the vast majority of settlers in the area. In September 2018, government, through the Provincial Minister's office, assured settlers that 2 000 letters would be issued to legalise their occupation.5 By contrast, in 2014, only 44 residents claimed to have had some document issued by RDC as proof of occupation, while 506 had no single document. Such pronouncements signal to settlers that their occupation is slowly being recognised as legitimate, with potential to spur physical development.

5.2.4 Interaction between institutions and organisations

Content analysis (selective coding) from the in-depth interview results shows the components that support development outcomes through the interaction between institutions and organisations. Table 2 provides further information on modes of acquisition, expenditure towards improvements, building materials, spatial arrangements, leadership, and interaction with local authorities.

A number of conclusions can be drawn from these narratives, which, in turn, support survey findings. First, there is a difference in the length of stay between the three blocks, with residents in Block A (RDC allocated) having been in the area longer than the other two. This has implications for the confidence of settlers, the materials used, and the perceptions on land rights. The 2014 survey revealed that 90% of the settlers had been in the settlement for 5 years or less (mostly from Blocks B and C), while the other 10% had been there for longer than 5 years. A further scrutiny of these results revealed that there was a relationship between construction materials and the length of stay in the settlement, with the Somers' d scale showing 0.118 (a weak positive relationship). The implication is that the older area will have more durable houses than the newly settled parts. Furthermore, the level of threats of the local authority also influences the materials used by residents. For instance, because RDC allotees felt less threatened by the local authorities, they were able to invest more in their buildings. Hence, the predominant use of mud bricks and corrugated iron roofing is also a result of threats from the local authority and age of the settlement.

Secondly, uncoordinated land use is one of the key characteristics of informal settlements. While not using the formal system of planning, settlers are able to agree on the apportionment of the land, even in the absence of State machinery. From the narratives, it was clear that they had an idea of "planning", as they apportioned plots. As argued by Hayek (1945: 521), any form of planning is based on knowledge, regardless of who is doing the planning. Thus, despite their low educational status, residents had an idea of measurement of plots and layouts. Statistics revealed that plot sizes averaged 395 square metres (with the category of 300m2 being considered as falling into the low-cost category of plots in local planning jargon).

Thirdly, it was clear that secondary transfers of plots were also occurring as evidence of an emerging land market. For instance, although 48% of the respondents agreed to have recently invaded the land, 41% claimed that they had bought from someone. In addition, the local social network of friends and relatives was found to be important for both communication and acquisition of land. It can thus be concluded that market forces are always omnipresent in these settlements, and that any indication of stability will result in secondary transfers, whether rights on land are confirmed or not.

Fourthly, occupation of land is organised via a form of institutional structure comprising a committee headed by a chairman, based on agreed local rules on assigning land uses (plots and passages) and apportionment of land parcels. The indication is that settlers are working from some knowledge base that enables them to "plan" uses and allocations around some measurement.

Finally, resistance and adaptation are important tools for the growth of informal settlements. As alluded to earlier, in June 2014, a combined team of local council representatives and Zambian Police moved into the area and demolished houses built on illegally acquired land. The majority of these houses were on Block B, while Block C was still in the formative stage. The 2018 survey by the KCC not only revealed re-occupation of Block B, but also consolidation of development of, and extension to Block C, increasing the coverage from 62 hectares (Block A and partly B) to 260 hectares (Blocks A, B and C). The number of completed houses, from 440 (2014) to 581 (2018), is another indication of growth. The process in-between has been one of contestation and struggles between settlers and local authorities, culminating in the recent promises of normalising the occupation. This shows the settlers' clear will and purpose to be part of the city.

6. CONCLUSION

The entry point for this study was that, due to rapid urbanisation, planning systems in most of the developing countries are failing, resulting in the rapid growth of informal settlements. In addition, even in cases where local authorities make efforts to prevent this growth, the shear resistance of settlers in these areas makes it difficult. The study noted that marginalised groups of society, mostly young and unemployed, make claims to the city for the various conveniences it provides. Where urban systems fail to accommodate them, they will fight for space in whichever way they can. One of the key means used is forceful occupation of any land deemed vacant, private or public. Based on some knowledge and a mix of social norms and borrowed statutory rules, they "plan" and build "their own city". After a long period of struggles, many of these settlements ultimately received the approval of the State, resulting in their permanent establishment, as is the case for Mindolo North informal settlement. The study noted three important stages in this development process, namely infancy (initial occupation), consolidation (characterised by rapid expansion of land coverage and construction), and maturity (intensification of construction within the occupied space). This whole process is underpinned by a local institutional and governance structure of informal rules, norms and interaction with formal structures.

As observed in the case of Mindolo North informal settlement, three key parameters such as land coverage, house completions, and property rights and documentation revealed the rapid growth of the settlement. The study revealed that between 2014 and 2018, the settlement had experienced an increase in land coverage from 62 ha to 260 ha, completed (including rebuilding) houses from 440 to 581, and received promises of offer letters for 2 000 settlers. Over the same period, the settlement had seen the construction of more permanent houses of concrete blocks, all these being clear indications of a maturing settlement. However, this has come after many struggles with local authorities, which saw demolition of about 600 houses in June 2014.

This study is limited in that it is based on one case study. Nonetheless, it points to a number of relationships that need to be investigated in a larger comparative study. For instance: What is the relationship between level of threats and durability of building materials? What is the relationship between age of a settlement and durability of building materials? What is the role of tacit knowledge in the building of informal settlements? These issues need further investigation.

REFERENCES

AKHMAT, G. & KHAN, M.M. 2011. Key interventions to solve the problems of informal abodes of the third world, due to poor infrastructure. Procedia Social and Behavioural Sciences, 19, pp. 56-60. https://doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.05.107 [ Links ]

ALI, M.H. & SULAIMAN, M.S. 2006. The causes and consequences of the informal settlements in Zanzibar. In: International Federation of Surveyors. Proceedings of the XXIII FIG Congress, Shaping the Change, 8-13 October, Munich, Germany: FIG, pp. 1-17. [ Links ]

ATTOH, K. 2011. What kind of right is the right to the city? Progress in Human Geography, 35(5), pp. 669-685. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510394706 [ Links ]

BRYMAN, A. 2004. Social research methods. 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

DAILY NATION. 2018. Over 2,000 Mindolo squatters to receive offer letters. Wednesday, 26 September. [Online]. Available at: <www.dailynation.info/over-2000-mindolo-squatters-to-receive-offer-letters/> [Accessed: 8 October 2019]. [ Links ]

DE BEER, S. & ORANJE, M. 2019. City-making from below: A call for communities of resistance and reconstruction. Town and Regional Planning, 74, pp. 12-22. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp74i1.2 [ Links ]

EIZENBERG, E. 2018. Patterns of self-organisation in the context of urban planning: Reconsidering venues of participation. Planning Theory, 18(1), pp. 40-57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095218764225 [ Links ]

FIEUW, W.V.P. 2011. Informal settlement upgrading in Cape Town's Hangberg: Local government, urban governance and the "right to the city". Unpublished Masters thesis. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

FITCHETT, A. 2014. Adaptive co-management in the context of informal settlements. Urban Forum, 25(3), pp. 355-374. DOI: 10.1007/s12132-013-9215-z [ Links ]

FUCH, C. 2003. Structuration theory and self-organization. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 16(2), pp. 133-167. [ Links ]

GIDDENS, A. 1984. The constitution of society - Outline of the theory of structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

HAYEK, F.A. 1945. The use of knowledge in society. The American Economic Review, 35(4), pp. 519-530. [ Links ]

HUCHZERMEYER, M. 2004. From "contravention of laws" to "lack of rights": Redefining the problem of informal settlements in South Africa. Habitat International, 28, pp. 333-347. DOI:10.1016/S0197-3975(03)00058-4 [ Links ]

JONES, P. 2017. Formalizing the informal: Understanding the position of informal settlements and slums in sustainable urbanisation policies and strategies in Banbung, Indonesia. Sustainability, 9, pp 1-27. https://doi:10.3390/su9081436 [ Links ]

KCC (KITWE CITY COUNCIL). 2018. Mindolo North informal settlement survey. Unpublished. Kitwe: KCC. [ Links ]

KREJCIE, R.V. & MORGAN, D.W. 1970. Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), pp. 607-610. [ Links ]

LAI, L.W.C., LORNE, F.T., CHAU, K.W. & CHING, K.S.T. 2016. Informal land registration under unclear property rights: Witnessing contracts, redevelopment, and conferring property rights. Land Use Policy, 50, pp. 229-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.09.016 [ Links ]

LEFEBVRE, H. 1996. The right to the city. In: Kofman, E. & Lebas, E (eds). Writings on cities. Cambridge, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 147-159. [ Links ]

LUSAKA TIMES, 2014. Kitwe City Council continues demolishing houses built on illegally acquired plots. Sunday, 7 June. [Online]. Available at: <www.lusakatimes.com/2014/06/07/kitwe-city-council-continues-demolishing-houses-built-illegally-acquired-plots/> [Accessed: 10 June 2014]. [ Links ]

LUSAKA VOICE. 2013. Construction of Zambia's largest mall to start soon. Monday, 1 April. [Online]. Available at: <www.lusakavoice.com/2013/04/01/construction-of-zambias-largest-mall-to-start-soon/> [Accessed: 9 October 2019]. [ Links ]

MABOGUNJE, A.L. 1990. Urban planning and the post-colonial state in Africa: A research overview. African Studies Review, 33 (2), pp. 121-203. https://doi:10.2307/524471 [ Links ]

MARUTLULLE, N.K. 2017. Causes of informal settlements in Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality: An exploration. Africa's Public Service Delivery and Performance Review, 5(1), pp. 141-163. https://doi.org/10.4102/apsdpr.v5i1.131 [ Links ]

MASIMBA, 2016. An assessment of the impacts of climate change on the hydrology of upper Manyame sub-catchment, Zimbabwe. Unpublished Masters thesis. Harare: University of Zimbabwe, Faculty of Engineering. [ Links ]

MASSEY. R.T. 2013. Competing rationalities and informal upgrading in Cape Town, South Africa: A recipe for failure. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 28(4), pp. 606-613.https://doi:10.1007/s10901-013-9346-5 [ Links ]

MSIMANG, Z. 2017. The study of the negative impacts of informal settlements on the environment. Unpublished Masters thesis. A case study of Jika Joe, Pietermaritzburg. Durban: University of Kwa-Zulu Natal, School of Built Environment and Development Studies. [ Links ]

MUNSHIFWA, E.K. & MOOYA, M.M. 2016a. Institutions, organisations and the urban built environment: Facilitative interaction as a developmental mechanism in extra-legal settlements in Zambia. Land Use Policy, 57, pp. 479-488. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.06.012 [ Links ]

MUNSHIFWA, E.K. & MOOYA, M.M. 2016b. Property rights and the production of the urban built environment: Evidence from a Zambian city. Habitat International, 51, pp. 133-140. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.10.005 [ Links ]

NASSAR, D.M. & ELSAYED, H.G. 2017. From informal settlements to sustainable communities. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 57, pp. 23672376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2017.09.004 [ Links ]

NEWSON, R. 2002. Parameters behind "nonparametric" statistics: Kendall's tau, Somers' D and median differences. Stata Journal, 2(1), pp. 45-64. [ Links ]

NKURUNZIZA, E. 2007. Informal mechanisms for accessing and securing urban land rights: The case of Kampala, Uganda. Environment and Urbanisation, 19(2), pp. 509-526. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247807082833 [ Links ]

NORTH, D.C. 1990. Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

NORTH, D.C., WALLIS, J.J., WEBB, S.B. & WEINGAST, B.R. 2009. Limited access orders: Rethinking the problems of development and violence. Washington, DC: World Bank. [ Links ]

PURCELL, M. 2014. Possible worlds: Henri Lefebvre and the rights to the city. Journal of Urban Affairs, 36(1), pp. 141-145. https://DOI:10.1111/ juaf.12034 [ Links ]

RAKODI, C. & LEDUKA, R.C. 2004. Informal land delivery processes and access to land for the poor: A comparative study of six African cities. Policy brief No. 6. [Online]. Available at: <www.idd.bham.ac.uk/research/researchprojs.htm> [Accessed: 18 August 2012]. [ Links ]

SAKALA, S. 2016. Causes and consequences of informal settlement planning in Lusaka District: A case study of Garden House. Proceedings of ISER International Conference, Nairobi, Kenya, 22-23 September, pp. 7-14. ISBN: 978-93-86083-34-0. [ Links ]

SKUSE, A & COUSINS, T. 2007. Spaces of resistance: Informal settlement, communication and community organisation in a Cape Town township. Urban Studies, 44(5-6), pp. 979-995. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980701256021 [ Links ]

SLIUZAS, R.V., MBOUP, G. & DE SHERBININ, A. 2008. Report of expert group meeting on slum identification and mapping. UN Habitat/ITC/CIESIN-Columbia University. [ Links ]

SORI, N.D. 2012. Identifying and classifying slum development stages from spatial data. Unpublished Masters thesis. University of Twente, The Netherlands. [ Links ]

THE ZAMBIAN. 2014. 150 houses razed in Mufulira's Kalukanya. 11 August. [Online]. Available at: https://thezambian.com/news/2014/08/11/150-houses-razed-in-mufuliras-kalukanya/ [Accessed: 11 August 2014]. [ Links ]

UNECE (UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE). 2009. Self-made cities in search of sustainable solutions for informal settlements in the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Region. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS HABITAT. 2013. The state of planning in Africa: An overview. HS Number: HS/010/14E. Nairobi: UN Habitat/Africa Planning Association. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS HABITAT. 2015. Informal settlements, Report 31. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

WATSON, V. 2014. The case for a Southern perspective in planning theory. International Journal of E-Planning Research, 3(1), pp. 23-37. https://doi:10.4018/ijepr.2014010103 [ Links ]

Peer reviewed and revised October 2019

Published December 2019

* The author declared no conflict of interest for this title or article

1 A visual inspection by the author on 22 July 2014 revealed that all the houses, except for those allocated by RDC, were razed down.

2 Approximately USD38.00 per month at the current exchange rate of K13.00 to USD1.

3 Lusaka Voice, 2013. Construction of Zambia's largest mall to start soon.

4 After Ipusukilo (now legalised) and Mulenga, the two largest informal settlements in the city of Kitwe.

5 A recent check at KCC revealed that no offer letters have yet been issued.