Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Town and Regional Planning

On-line version ISSN 2415-0495

Print version ISSN 1012-280X

Town reg. plan. (Online) vol.75 Bloemfontein 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp75i1.7

ARTICLES

Reflections on expropriation-based land reform in Southern Africa

Oorwegings vir onteieningsgebaseerde grondhervorming in Suider-Afrika

Menahano holima khutliso ea lefatshe ele mokhoa oa ntlafatso le kgatelopele Afrika e ka borwa

Anele Mthembu

Howard College, University of KwaZulu-Natal, 238 Mazisi Kunene Road, Glenwood, 4041, Durban, South Africa. Phone: 0837756749, e-mail: <anelemthembu@gmail.com>

ABSTRACT

The South African media mainly reports on the division that the land debate is creating in the country, with some fearing that South Africa could be the next Zimbabwe and others anticipating a long-awaited new dawn. The land debate in South Africa is thus ongoing. However, the implications that may affect the country have not been pursued in great detail. South Africa may learn lessons from other Southern African countries, namely Zimbabwe and Namibia, that had similar land processes. Making use of a semi-systematic literature review, the article considers land redistribution in South Africa, Zimbabwe and Namibia through content analysis, by analysing land in terms of transition to democracy/transition to independence; land reform, and expropriation land reform, in order to reflect on the implications that expropriation-based land reform has had in these countries. The article considers the lessons learnt from Zimbabwe that have raised concerns by those who are against land expropriation without compensation, and those who believe that it will not result in a new dawn for the country. However, the 2019 Draft Expropriation Bill contextualises land expropriation and compensation in South Africa that is aligned with the Property Clause of the Constitution. Hence, the evaluation of South African legislation that accommodates expropriation-based land reform and planning legislation that could be utilised to address the land issue and spatial inequality. This highlights that proper legislation and effective spatial planning can be considered, in order to address land reform in South Africa.

Keywords: Land reform, expropriation, compensation, planning

ABSTRAKTE

Die Suid-Afrikaanse media berig hoofsaaklik oor die verdeling wat die gronddebat in die land geskep het, met sommige wat vrees dat Suid-Afrika die volgende Zimbabwe sou wees, en ander wat hoop op 'n lang verwagte nuwe aanbreek. Die gronddebat in Suid-Afrika duur dus voort. Die implikasies wat die land kan beïnvloed, is egter nie breedvoerig ondersoek nie. Suid-Afrika kan lesse leer uit ander lande in Suider-Afrika, naamlik Zimbabwe en Namibia, wat soortgelyke grondprosesse gehad het. Deur gebruik te maak van 'n semi-sistematiese literatuuroorsig, word die herverdeling van grond in Suid-Afrika, Zimbabwe en Namibia deur middel van inhoudsanalise ondersoek deur grond te ontleed in terme van oorgang na demokrasie/oorgang na onafhanklikheid; grondhervorming, en onteiening van grondhervorming ten einde te besin oor die implikasies wat onteieningsgebaseerde grondhervorming in hierdie lande gehad het. In die artikel word die lesse wat uit Zimbabwe geleer is, gestel deur diegene wat besorg is oor grondonteiening sonder vergoeding, teenoor diegene wat glo dat dit tot 'n nuwe aanbreek vir die land sal lei. Die 2019 Wetsontwerp op Onteiening kontekstualiseer egter onteiening en vergoeding van grond in Suid-Afrika wat in lyn is met die eiendomsklousule van die Grondwet. Van daar die evaluering van Suid-Afrikaanse wetgewing wat voorsiening maak vir onteieningsgebaseerde grondhervorming en beplanningswetgewing wat gebruik kan word om die grondkwessie en ruimtelike ongelykheid aan te spreek. Dit beklemtoon dat behoorlike wetgewing en effektiewe ruimtelike beplanning moontlike oor-wegings is om grondhervorming in Suid-Afrika aan te spreek.

Sleutelwoorde: Beplanning, grondhervorming, onteiening, vergoeding

TUMELO

Naheng ea Afrika Borwa, batlalehi ba litaba babontshitse karohano lipakeng tsa batho e bakiloeng ke lipuisano mabapi le lefatshe. Ba bang ba batho ba tshohile hore Afrika Borwa e tlo tshoana le Zimbabwe, ha ba bang bona ba lebelletse liphetoho tse thabisang tse tla tlisoa ke lipuisano tsena. Lipuisano mabapi le lefatshe li sa tsoelapele le joale naheng ea Afrika Borwa, empa litla-morao tse tla tlisoa ke lipuisano tsena hali seka-sekoe ka botlalo. Ka mohlomong, naha ea Afrika Borwa e ka ithuta ho tsoa linaheng tse ling tsa Afrika e Borwa tse tssamaileng tsela ena; mohlala ke linaha tsa Zimbabwe le Namibia. Ka ho lekola lingoliloeng tse teng ka botlalo, boithuto bona bo shebisisa phetoho e teng ho lefatshe linaheng tsa Afrika Borwa, Zimbabwe le Namibia, mmoho le democrasi le ho nkuoa hoa lefatshe, ele ho hlahloba kamoo li ammeng linaha tsena ka teng. Sengoliloeng sena se boetse se etsa boithuto bo nkuoeng naheng ea Zimbabwe, bo bontshang litletlebo tse hlahisoang ke ba khahlanong le khutliso ea lefatshe ntle le matsheliso a letho, le ba sa lumeleng hore hotla ba le liphetoho ka lebaka la lipuisano tsa lefatshe. Le ha hole joalo, molao oa 2019 Expropriation Bill o fana ka thlaloso ea khutliso ea lefatshe, le matshediso a ka fanoang naheng ea Afrika Borwa, haholo o ipapisitse le Molao Theho. Ka hona, sengoliloeng sena se lekola molao oa naha ea Afrika Borwa mabapi le khutliso ea lefatshe le meralo e ka sebelisoang ho seka-sekana le taba tsa lefatshe le ho hlokahala hoa tekatekano holima lona. Ka hona, molao o nepahetseng mmoho le thero e nepahetseng ea lefatshe li ka thusa ho lokisa taba ea phetoho ea lefatshe naheng ea Afrika Borwa.

1. INTRODUCTION

The land debate in South Africa is one of the current big news stories; however, the implications that may affect the country have not been pursued in great detail. The media has, however, demonstrated the division that the land debate has created in the country, with some fearing that South Africa would be the next Zimbabwe and others anticipating a long-awaited new dawn. One would argue that the land debate is fuelled by the history of land dispossessions as well as the progress of the land reform programme in South Africa. This has resulted in some political parties anticipating the long-awaited new dawn through expropriation-based land reform, namely land expropriation without compensation, which they believe could rectify the injustices of the past (Economic Transformation Resolution, 2017: 31)

To suggest considerations that may be useful to assist in landreform matters and address spatial inequality, the land debate should be assessed as structurally embedded in the historical processes of colonial rule and apartheid in South Africa. Therefore, the future of South Africa will be intimately paralleled by events that took place in Southern African countries such as Zimbabwe and Namibia that had similar processes unfolding to South Africa, and further reflect on their expropriation-based land reform. This article unpacks the history of land for the mentioned Southern African countries and reflects on the outcomes of Zimbabwe and Namibia in terms of implications that they experienced, in order to note the type of implications that South Africa would endure. This article aims to provide clarity on land expropriation and its evolution in all three countries, focusing on the implications it had, in order to predict the potential outcomes if South Africa enacts the 2019 Draft Expropriation Bill as a statute.

By introducing the methodology of this article first, the semi-systematic literature review critically analyses the evolution of land in all three countries and reflects on expropriation-based land reform.

2. METHODOLOGY

A semi-systematic review approach is used, as it overviews how research within a selected field has progressed over time (Harden & Thomas, 2010: 749; Snyder, 2019: 333). This approach is significant because of its potential contribution to creating an agenda for further research that can provide an historical overview on a distinct topic such as land. This approach is also useful for common issues within a specific research discipline (Snyder, 2019: 333). A number of methods can be used to analyse findings from a semi-systematic review. For this study, content analysis is used, as it provides an orderly and objective means of evaluating the history of land, especially the process of land expropriation in the mentioned Southern African countries (Braun & Clark, 2006: 77; Bengtsson, 2016: 8).

The methodology of this study aims to thoroughly transform the diverse contexts on the history of land in Southern Africa into a concise summary of key findings, which is categorised under the following themes: transition to democracy/ transition to independence; land reform, and expropriation land reform, in order to reflect on the implications that expropriation-based land reform has had in those countries (Erlingsson & Brysiewicz, 2017: 94; Snyder, 2019: 334).

3. SEMI-SYSTEMATIC LITERATURE REVIEW

This semi-systematic literature review critically discusses the historical context of land in South Africa, Zimbabwe and Namibia, and proceeds to outline why the land issue was on the agenda when South Africa became democratic and Zimbabwe and Namibia became independent states. It is fundamental to consider the ethical implications in the context of the distribution of land when South Africa became democratic.

3.1 South Africa

3.1.1 Historical context

Development that occurred pre-1948, as a result of the pursuit of territorial domination, reveals that society was strongly divided along racial lines (Feinstein, 2005: 22). The discovery of minerals particularly diamonds and gold in Kimberley and the Witwatersrand in 1867 and 1886, respectively, advanced territorial domination and transformed the economic anatomy of South Africa (Feinstein, 2005: 13). This led to the transformation of the peripheral agricultural economy into the industrial economy with a strong mining sector. This transformation strongly influenced the physical separation and spatial inequality in reserves. The latter refers to places designated for the Black population throughout South Africa (Murray, 2008: 16).

The Natives Land Act (No. 27 of 1913) defined certain areas as African reserves and this statute laid down that the Black population could not purchase or occupy land outside the reserves; this statute was to ensure the territorial segregation of the races (RSA, 1913: 438; Wolpe, 1972: 426). According to Van Wyk (2013: 91), this statute

signalled the commencement of legalised discriminatory land legislation in the country. Coupled with the Development Trust and Land Act (No. 18 of 1936), the land allocated for the Black population was 13%, while the White population (one-fifth of the population of South Africa) was allocated 87% of land. The Natives Land Act of 1913 was a fundamental legal instrument that further drove Africans out of the agrarian economy to work mainly in the mining sector. Khuzwayo (1998: 38) argued that this signalled the consolidation of the gold-based capital accumulation process in South Africa, and indicated the initiation of legalising the racial character of the spatial framework.

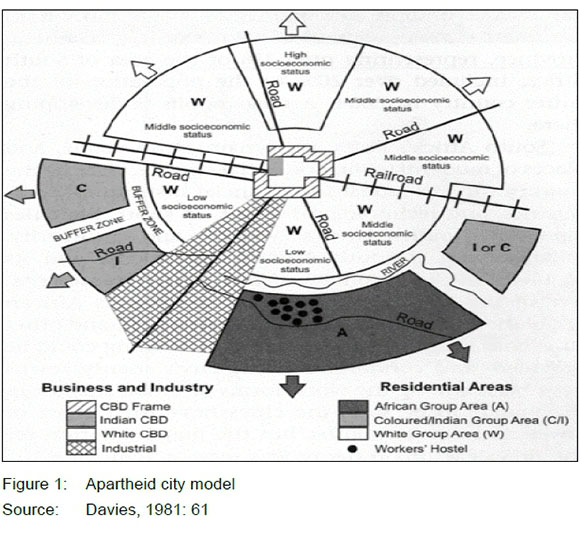

This was the case since different provincial ordinances, consistent with the supreme legislation at the time, namely the Constitution of 1909, made provision for the preparation of town planning schemes in White-, Indian- and Coloured-owned areas, whereas town planning schemes in Black-owned areas were prepared later by the apartheid state central government (Phuhlisani, 2017: 10). The Natives (Urban Areas) Act (No. 21 of 1923) regulated the presence of Africans in urban areas, by establishing African locations on the outskirts of White urban and industrial areas. It also determined access to, as well as the funding of such areas, since they were initially characterised by weak or no economic bases. One of the outcomes of segregating areas was a dual economy characterised by economic activity mainly in mines or on commercial farms. Land expropriation was used to establish the racially segregated spatial framework, since land was acquired from one group for another group, in order to accommodate segregated development and planning. This was maintained by means of buffers such as open space systems, topographical features, freeways, cemeteries as well as railway lines (Houston, Mati, Seabe et al., 2014: 19). This spatial configuration model resulted in cities being fragmented in terms of race, land uses and institutions.

The hegemony of power among Whites deepened segregated development and planning with its apparent racial, institutional, and land-use fragmentation. The Group Areas Act (No. 41 of 1950) was among the various statutes enacted by the ruling National Party government to maintain the racial character of South African society (RSA, 1950: 407; Mabin & Smit, 1992: 314). This Act was considered the dominant spatial planning Act that was used as a significant tool to achieve racially influenced spatial planning that strove to ensure racial segregation.

According to Van Wyk (2012: 18), the Group Areas Act (No. 41 of 1950) was employed to consolidate the principles that had implications on land, including the division of rural and urban land on the basis of race; the placing of the supply of Black labour under state control, and the application of state power to maintain order and to regulate all aspects of the Black majority. This Act saw the division of society at large, and created different regions, that would develop in unequal and uneven ways, due to spatial disparities and spatial inequalities.

The development and implementation of the Group Areas Act had two requirements for planning during apartheid. Its mandate was, first, to allocate racially zoned land for the occupation of specific races and, secondly, to re-arrange existing racially mixed areas into areas where only one race group was permitted to live (Mabin, 1992: 407). The enforcement of this Act was aimed at creating a spatial pattern around different racial neighbourhoods, thus leading neighbourhoods to grow in accordance with the apartheid city model. The growth of different racial neighbourhoods was maintained by the existence of buffers that promoted distinct spatial boundaries between racial pockets in the city.

As mentioned, the apartheid state central government-initiated land-use planning for African residential development happened because of an increase of the Black population in urban areas. Hence, the government identified tracts of land and funded the development (Phuhlisani, 2017: 10). By the late 1970s, the State had developed social amenities and approximately half a million houses for urban Africans in White South Africa and built 160 748 units in Bantustan urban areas (Phuhlisani, 2017: 10). However, public investment in housing in segregated townships in White areas was reduced. The conditions, in which townships could be developed, were in accordance with the dictates of the apartheid government, such as "it should be separated from the White area by a buffer where industries exist or are being planned; it should have land to expand away from White areas; it should be within easy distance of the town or city for transport purposes, by rail rather than road; and it should have one road that connects it to the town, preferably running through the industrial area" (Phuhlisani, 2017: 10).

This was in an effort to keep the Black population separate from the Whites, far away and buffered in housing that was only available to them on a rental basis. This resulted in cities structured along the lines that are depicted in the apartheid city model (Figure 1). The apartheid city model remained, even after the Soweto uprising of 1976, and this heightened the urgency to revise the constitutional framework. There were cases of international investors withdrawing from South Africa, thus precipitating an economic crisis.

The Expropriation Act (No. 63 of 1975) was enacted, meaning that land expropriation was legalised, allowing compensation to be paid according to the market value of the land (RSA, 1975: 8).

According to Clark & Worger (2016: 91), there were preliminary steps to the alterations in the Constitution of 1983, with the proposal of a cabinet committee to investigate the possibility of amending the Westminster Parliamentary System applicable in South Africa, primarily with a view to accommodate other population groups in the process of government. The tricameral parliament was established, in order for the Indians and the Coloureds to distinguish between their 'own' affairs. This resulted in improving the quality of life of, and progressive outcomes for Indians and Coloureds in terms of housing and education (Clark & Worger, 2016: 91). This was an attempt to justify the fragmented system in terms of race, land uses and institutions as well as an attempt to get out of South Africa's political deadlock. The then President exercised administrative responsibility for Black affairs. Hence, government planners had their sights set on making political amendments to reconstruct segregated development instead of reconstructing the social and spatial framework.

The political and socio-economic aspirations of the marginalised Black people could not be overlooked. The varying institutional strategies to prop up the racially separate political system proved unsuccessful, since they were inadequate. South Africa's economic position after the 1970s and the continuous political pressure compelled political parties to come to the negotiating table.

3.1.2 Transition to democracy

The enactment of the Local Government Transition Act (No. 209 of 1993) was the transformational point of the 1990s and the result of the negotiations between the various stakeholders during the CODESA engagements in Kempton Park (Bardhan & Mookherjee, 2006: 1). This Act laid the foundation to create a framework for the orderly transition of local governments in South Africa to democracy. It further indicated three phases of transition that should occur or had to take place, in order for democracy to exist, namely:

• Pre-interim phase, establishing the local institution of municipal elections;

• Interim phase, the commencement with municipal elections to last up with a different local government system has been drafted and legislated;

• Final phase, the establishment of a new local government system (White Paper on Local Government, 1998: 14).

The grouping that collaborated from 1990 to 1993 reconvened, in order to support the new legislation, and functioned during the interim phase, while the long-term vision for urban and planning regulatory reform was finalised (Berrisford, 2011: 248). The initial element of the proposed new legislation was that it would provide a different perspective for the approval of land development initiatives that were anticipated by the new democratic government as part of its Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP).

As the 1994 elections were approaching, there was an indisputable need for the development of legislation that would enable the transition to democracy.

In order to achieve this, several engagements took place in 1993, in which Inglogov and the Urban Foundation sponsored processes of sharing knowledge and technical rationale. Inglogov was the lead organisation that supported the democratic movement in negotiating local government restructuring (Van Ameringen, 1995: 81). The Urban Foundation was established in mid-December 1976 with Anglo-American's Harry Oppenheimer as chairperson, with an initial emphasis on improving the socio-economic circumstances of the Black population (Smit, 1992: 36). They sponsored the processes, in order to develop new approaches for planning legislation that would also inspire ideas for new legislation and the new Interim Constitution under a broad framework of the National Housing Forum (Berrisford, 2011: 249).

3.1.3 Land reform

During the engagements that took place in the 1990s to alter segregated development and planning, a White paper on land reform was enacted. Land was viewed as a vital component for the reform agenda; it proposed to enhance access to land rights for all, to upgrade the quality and use of land, and to provide security of tenure. The first democratic government directed the progress of the transformation strategy when it was implemented. Land reform attempted to rectify the socio-economic ills of apartheid by implementing its three pillars, namely land restitution, land redistribution, and security of tenure (Gibson, 2009: 12). The main purpose of land reform was to implement change on land-related issues by applying these three pillars, since land is a central component of planning, and land-related legislation has an impact on planning legislation (Van Wyk, 2012: 15).

Land reform refers to a systematic process that is characterised by a series of inventions to transform patterns of land ownership, utilisation and tenure systems in a manner that empowers those who experienced land dispossession after the enactment of the Natives Land Act (No. 27 of 1913). The reason why it is for people who were dispossessed of their land post-1913 is that 1913 was deemed appropriate as a pragmatic compromise between colonialism and apartheid, which occurred in 1652 and 1948, respectively. This was done to minimise potential conflict from competing claims that would date far back and difficult to prove, especially among different groups of Black South Africans (Kepe & Hall, 2016: 7). It is worth noting that there have been contestations about the compromise, especially since those who represent the Khoi San argue that this compromise is unjustifiable; there has been no alteration; however, government has made references to consider altering the dispossession periods.

According to Sihlobo & Kapuya (2018: 1), a total of 17 439 million hectares have been transferred from White ownership since 1994. This is equivalent to 21% of the 82 759 million hectares of farmland in freehold. This is significant in context with the 30% committed by the government to redistribute land; however, the allocated time frame is beyond the initial set target (White Paper on South African Land Policy, 1997: 10).

Kepe and Hall (2016: 16) detail the progress of the pillars of land reform, and argue that the restitution programme began in 1994, but it has had slow progress. Out of the 12 000 cases that were submitted, less than Ave had been finalised by 1997, triggering several people, especially since 3.5 million people were forcibly removed under the Land Act of 1913 (Kepe & Cousins, 2002: 2). In 1998, the programme was reviewed and adjustments were made to fast-track the administrative process that was slowed down by legal aspects. By the end of 1998, a total of 68 878 restitution claims had been registered, but only 49 claims had been resolved. This programme, however, was fast-tracked significantly and, by the end of March 2002, the Commission on Restitution of Land Rights had settled 29 877 claims out of the overall 68 878 claims that had been submitted (Kepe & Hall, 2016: 11). According to the Department of Land Affairs (2005: 18), by the end of March 2005, the number of claims settled by the Commission on Restitution of Land Rights increased to 59 395, which benefited 900 000 individuals on land measuring 887 093 hectares.

The land redistribution programme required agrarian land equivalent to 23.6 million hectares for an estimated 1.76 million rural households across South Africa. However, by 1998, only 161 317 hectares (0.7%) of land had been transferred (Department of Land Affairs, 2005: 18). The 0.7% of land redistributed was significantly low compared to the 30% of land that was meant to be redistributed by 1999. Sihlobo and Kapuya (2018: 1) highlighted the most recent figure of land that has been redistributed. The 21% of land that has been redistributed is less than the initial target and beyond the initial time frame. However, Kepe & Hall (2016: 11) argue that one of the reasons for this was that the initial and revised target was unrealistic, due to the State's limited resources.

According to Kepe, Wynberg and Ellis (2005: 7), the third component of land reform is land tenure reform that aims to address issues such as insecurity of tenure as well as concurrent and disputed land rights that are an outcome of apartheid legislation. This component is reinforced by the restitution and redistribution programme; hence, its main objective is to protect people from evictions and provide them with long-term security on their land or land on which they were labour tenants, in order to encourage people to invest in the development of their land (Department of Land Affairs, 2005: 10).

3.1.4 Ethical implications

The moral arguments in media and political circles for and against land expropriation without compensation in South Africa often fail to distinguish between a number of separate issues. The initial moral argument for land reform is that, regardless of how it came about, land ownership is highly unequal, and redistribution via land expropriation could fast-track land redistribution, which could promote equality and result in social justice (Ntsebeza & Hall, 2007: 3). This would apply to any population, irrespective of the origins of existing land tenure.

The second justification for land redistribution that emerges from the national political background of South Africa's history is the imperative to rectify past wrongs. It is uncontested that, for centuries prior to democracy, Black South Africans were dispossessed of their land to ensure racial separation that was reinforced by the racially segregated spatial framework (Houston et al., 2014: 19). Land reform has attempted to reverse this process and return land to the dispossessed; however, it has experienced slow progress. Land expropriation without compensation seeks to fast-track land reform (Economic Transformation Resolution, 2017: 31). A common counterargument is that the historical interplay of forces occurred a long time ago, and the history of land expropriation does not acknowledge the dispossession of land; however, they simply found the European settlers in South Africa (Feinstein, 2005: 13). Hence, without this historical contextualisation, some people maintain that there is no moral relevance for land expropriation without compensation. However, one would argue that it does not matter what people who ignore history think.

Lastly, the racial basis of land inequality needs to be specifically acknowledged (Land Audit Report, 2017: 1). The land-related issues in South Africa stem from the historical governance of the country that resulted in the uneven ownership of land. This dates back to land dispossession and acquisition during colonialism and was exacerbated by apartheid legislation (Wolpe, 1972: 427). This resulted in spatial inequality and unequal land ownership that still prevails, since the population of South Africa consists of 79% Blacks, with only 1.2% directly owning the country's rural land and 7% of formally registered property in towns and cities (Nhlabathi & Van Rensburg, 2018: 1). The White population that constitutes 9% of the entire population of South Africa directly owns 23.6% of the country's rural land and 11.4% of land in towns and cities (Land Audit Report, 2017: 2).

3.2 Zimbabwean perspective

3.2.1 Historical context

As mentioned earlier, Zimbabwe has distinct similarities with South Africa when it comes to the history of land. Unlike South Africa, Zimbabwe remained under the governance of African leaders until the 19th century whereby the country experienced a "hasty and haphazard process of enclosure" by European powers that were driven by suspicion of the ambitions of rivals (Davidson, 1984: 290, cited in Thomas, 2003: 693). One may argue that the discovery of minerals in South Africa increased the pursuit for more minerals. Unfortunately, the British South African Company (BSA) did not yield profits, since extracting minerals proved to be a challenge in Zimbabwe, and generated no profit over three decades (Rosset, Patel & Courville, 2006: 41). There was a shift towards the agrarian economy; however, there were challenges with this, since White settler farmers struggled to generate good production yields.

According to Thomas (2003: 693), the settlers acquired land in the best agro-ecological zones that would generate good production yields, due to its soil quality and access to water. In some instances, the natives were pushed out into less fertile areas and had to pay rent and tax for the land and property that was reserved for them to the BSA. In 1922, the settlers voted to run the country themselves with limited supervision by the British government. In 1923, they opted for self-governance as an autonomous British colony (Roset et al., 2006: 42). The Morris-Carter Commission of 1925 was established, and they were required to develop a planning framework that would ensure the emergence of Zimbabwe; this framework was to be a self-sustaining British colony (Thomas, 2003: 693). The Commission proposed a framework that had landholding patterns in order to set the White settler economy on a stable platform. Hence, segregated legislation, namely the Land Apportionment Act of 1930, was adopted in order to impose racially segregated spatial planning on the country. The segregated spatial planning model was maintained into the post-independence phase (Moyo, 2001: 7).

The Land Apportionment Act of 1930 allocated the natives in generally poor, remote and inadequate fixed reserves. The Europeans were allocated alienated lands of the natives (Thomas, 2003: 694). Over the next 30 years, the colonial government concentrated all its policies on the promotion of expanding European settlement and building up its power and economic predominance (Thomas, 2003: 694).

Until the 1950s, there were forced removals of natives to accommodate White farming, and they continued to experience this right until the 1970s. Although the labour force was based in the fixed reserves, now re-labelled 'communal areas' (CAs), they were prohibited from engaging in the agrarian markets (Thomas, 2003: 693; Moyo, 2001: 16). In 1930, special designated areas were first established for emergent Black farmers; in this instance, successful 'master' farmers were granted portions of land up to 100 hectares with the intent of developing a Black yeoman class (Moyo, 2001: 17). These are now referred to as 'small-scale commercial farmers' (SSCFs). Enormous land pressure was mounting in the CAs between 1961 and 1977, since the area under cultivation increased at the expense of grazing, although cattle numbers still increased (Thomas, 2003: 694). The farmers did not receive any support until 1978, when a small farm credit scheme was established.

3.2.2 Transition to independence

During the transition to independence in Zimbabwe, the racially segregated spatial framework that enabled the racial differentiation in land ownership or land accessibility was altered as the percentage of land available for the natives was increased (Rosett et al., 2006: 44). The natives initially occupied 30% of the land and this was increased to approximately 40%. Spatial planning post-1980 changed in Zimbabwe, since the initial plan was to transfer agrarian land back to the natives and not leave it in the hands of White settlers. In order to achieve this, land reform was to be implemented; however, it did not include mass expropriation of land, although the state did maintain the right to expropriate land for public and resettlement reasons.

3.2.3 Land reform

Land reform in Zimbabwe took place in four distinct phases or paradigms. The initial paradigm (The Lancaster House phase of 1980-1990) was an outcome of the 1979 signing of the Lancaster Housing Agreement that officially mandated the commencement of the land-reform programme in Zimbabwe (Chilunjika & Uwizeyimana, 2015: 131). This paradigm was characterised by the willing buyer-willing seller policy and accepted the British demands of protecting White farmers, because the United States of America and the British governments promised fiscal resources to compensate for land (Chilunjika & Uwizeyimana, 2015: 131). However, the Agreement required the Zimbabwean government to wait a decade prior to implementing any land-reform programme, although it did permit government to purchase unoccupied land for resettlement purposes.

According to Masiiwa & Chipungu (2004: 1), although the initial paradigm for land reform was relatively well-planned and supported, it failed to achieve its objectives. This was due to the fact that government failed to vigorously pursue the land-redistribution plan in order to resolve the existing land imbalance, although donors were generous with financial assistance specifically for land redistribution (Masiiwa & Chipungu, 2004: 2). In an effort to achieve the objectives that were initially set, and to speed up land acquisition, the Land Acquisition Act of 1992 was enacted. This statute stipulated that land that was for sale should be initially offered to the government; underutilised and derelict land would be identified for possible involuntary appropriation (Masiiwa & Chipungu, 2004: 3). Although this Act was enacted, it did not have much impact on land redistribution, even with the Lancaster Agreement no longer binding the country.

The second paradigm (Land-Reform and Resettlement Programme -Phase II) was implemented in 1998, with the aim of acquiring more land for the landless poor, overcrowded families, youth, and agricultural graduates. In order to achieve this, the government hosted an International Conference with the aim of securing more financial assistance (Masiiwa & Chipungu, 2004: 4). The Economic Structural Adjustment Programme (ESAP) was adopted, with the aim of integrating Zimbabwe into global markets through trade and production with conditions such as, among others, reduced trade tariffs. Unfortunately, the adoption of ESAP in 1990 had negative implications on the economy. This resulted in donor countries being wary of offering more financial assistance, which meant that Zimbabwe had to rely on loans to support the landreform initiative. This resulted in the World Bank controlling various aspects of the programme and economy (Thomas, 2003: 698).

According to Moyo (2013: 6), this led to the slowing down of land redistribution. Due to the conditionalities of international financial institutes, this resulted in the expansion of land markets to foreigners and aspiring Black commercial farmers, which led to increased private land subdivisions and consolidations. Although there was a shift in terms of policies and economic programmes, the amended Constitution and the Land Acquisition Act permitted compulsory acquisition of land without compensation.

3.2.4 Expropriation-based land reform

The third paradigm (Fast-Track Resettlement Programme (FTRP) was implemented, due to the failure of a substantive follow-up to the Donor Conference and limited progress than what government had anticipated. This resulted in government implementing land reform at an accelerated rate (Thomas, 2003: 700). One of the reasons why this third paradigm was implemented was because of the pressure from the land hungry and landless put on government, which resulted in violent farm invasions. The objectives of the third phase were the same as those of Phase II, except the targets of the programme that required more land to cover the A1 land-reform model. The latter was used to target the rural landless and farmers, in order to resettle villages or self-contained small farms (Masiiwa & Chipungu, 2004: 12). The beneficiaries ranged from the poor to small- to medium-scale indigenous commercial farmers (Moyo, 2013: 31).

The expropriation-based land reform had a specific time frame for completion, which was prior to the rainy season of 2000 until December 2001 (Masiiwa & Chipungu, 2004: 11). However, Chilunjika & Uwizeyimana (2015: 131) argue that this programme was extended beyond the stated time frame. This phase aimed to ensure the rapid completion of land redistribution, while spreading infrastructure development over a decade.

According to Moyo (2001: 24), one of the reasons why land was expropriated from White commercial farmers was to encourage and increase funding from Britain and other donor nations. Unfortunately, land invasions did not redress the colonial legacy of inequitable landownership and the racially based spatial framework. One could argue that the reason for this was lack of a plan that would alter the racially based spatial framework to a spatial framework that addressed spatial inequality. Hence, when Zimbabwe became radical in its implementation of land-reform initiatives and failed to comply with conditions of the international financial institutes and other donor countries, funding was terminated or reduced to a point that made it difficult for Zimbabwe to engage in globalised markets.

The process of land reform in Zimbabwe, as highlighted by Hellum and Derman (2004: 1785), of mass expropriation of White-owned land or farms, in order to give indigenous African people the opportunity to collectively own and farm the land, proved to be unsuccessful. The markets were mainly affected because of the ESAP that was adopted; this included the reduced trade tariffs that resulted in the sharp decline in food and export crop production, massive inflation, unemployment, food shortages, and a collapsing health and educational system (Moyo, 2001: 19).

The fourth paradigm (partnerships between White commercial farmers and the indigenous African people) is the latest land-reform phase, whereby government abandoned the mass expropriation of land for reform purposes (Moyo, 2013: 37). This phase adopted an incremental approach that entails native landholders to venture into mutually beneficial partnerships and agricultural contracts with the once evicted White commercial farmers.

3.2.5 Lessons learnt

Zimbabwe adopted land reform in order to address the land issue; however, the Lancaster Housing Agreement required the country to wait for a decade prior to implementing land reform in the country. One could argue that this decade could have been used to strategise and plan for the implementation of land reform, and save fiscal resources that were acquired during this period for redistributive purposes.

The different phases of the land-reform programme had different outcomes. The third phase based on expropriation had detrimental outcomes, including disinvestment in the country and decline in markets which impacted on the socio-economic well-being of the country (Thomas, 2003: 703). These outcomes are what some people fear for South Africa, especially if a similar approach is adopted. Hence, one could argue that the experience for Zimbabwe is an eye-opener to plan accordingly, prior to implementing land reform in the same manner as Zimbabwe.

3.3 Namibian perspective

3.3.1 Historical context

Namibia was colonised by Germany in the late 19th century and remained under its governance until the early 20th century, when it was conquered by South African troops and later became a South African protectorate under the League of Nations (De Villiers, 2003: 29).

Land was expropriated from the indigenous people who were confined to a meagre 25% of agricultural land, in order to consolidate White commercial farming. The indigenous people were allocated infertile and dry land with little or no infrastructure, compromising their survival, especially since they depended on land for their overall well-being (Dlamini, 2014: 11).

3.3.2 Transition to independence

Prior to Namibia becoming an independent state, the land issue was on the agenda during the negotiations, especially because it represented the political symbolism in the liberation struggles and brought back painful memories of its loss during colonialism (Dlamini, 2014: 24). Hence, when the country became independent on 21 March 1990, it was inevitable that land inequality needed to be addressed.

The government focused on the inequitable access to commercial land ownership, especially since 90% of the population derived their livelihood from commercial or subsistence farming (Dlamini, 2014: 38). The government realised the significance that land would play in the development of the country and eradication of poverty; hence, it was necessary to have a national consultation on land. This resulted in the 1991 National Conference on Land Reform and the Land Question, which was an important milestone for land reform, since it defined the manner in which government would implement reform in both commercial and communal agricultural areas (De Villiers, 2003: 33). These constituted parallel agricultural systems that were almost divided equally in relation to land utilisation, but also reflected the racial division in the country at the time of independence (Dlamini, 2014: 39).

The Conference resulted in the new government adopting a policy aimed at redressing Namibia's history of uneven land ownership through a process of national reconciliation and in accordance with the provisions of Article 16 of the Namibian Constitution, which stipulated that compensation must be issued for any private land expropriated. According to Dlamini (2014: 39), realising that there was public demand for land redistribution, the government adopted the willing seller-willing buyer approach as the primary means of land acquisition. Land reform was mainly for resettling small-scale farmers and establishing a scheme for emergent Black farmers to acquire large-scale farms.

3.3.3 Land reform

The 1991 Land Conference established a platform for the landreform programme, policies and legislation to be developed. The landreform process was based on two main statutes, namely the Agricultural (Commercial) Land Reform Act and the (Communal) Land Reform Act. This article discusses the initial Act that endorsed the willing seller-willing buyer principle.

The Agricultural (Commercial) Land Reform Act 6 of 1995 was the initial piece of legislation on land reform in Namibia. The Act established a legal framework for land acquisition by the state for resettlement purposes, following the willing buyer-willing seller principle. Commercial farmers who were willing to sell their land freely offered it to the government. An official commission would inspect the land as to whether or not to purchase it, depending on the suitability of the land and quality for resettlement purposes (Republic of Namibia, 1995: 6). It provided for the creation of a Land Reform Advisory Commission to advise on the suitability of land that government wanted to purchase and resolve conflicts arising from other sections of the Act.

The Agricultural (Commercial) Land Reform Second Amendment Act 2 of 2001 passed a land tax for land-reform purposes. It provided for the payment, by every owner of commercial agricultural land, of a land tax based on the value (Unimproved Site Value) of the land (Republic of Namibia, 2001: 3). This was to penalise unproductive farmers by obligating them to sell their land to the state for resettlement. This tax, however, has not been collected, even though the necessary procedures were introduced in April 2002 (Dlamini, 2014: 41). One may argue that the aim of the land tax to create revenue to purchase more commercial agricultural land for the resettlement programme was not fulfilled.

3.3.4 Expropriation-based land reform

The Amended Agricultural (Commercial) Land Reform Act of 2003 empowered government to expropriate land "in the public interest", subject to compensation in terms of Section 20 of the Act (Republic of Namibia, 2003 2; Dlamini, 2014: 42). According to Treeger (2004: 2), Article 14(2) of the Act categorises expropriation under four categories for the purpose of speeding up the land-reform process. One of the main reasons for using expropriation in Namibia was due to government abandoning the willing buyer-willing seller approach, since it inflated market-related land prices and subsequently led to the unavailability of productive agrarian land (Dlamini, 2014: 42). Namibia initially saw redistributive reform as essential for successful rural development and economic stability; however, due to the lack of prioritisation and other issues, it resulted in slow progress and, hence, the reliance on expropriation (Treeger, 2004: 6).

According to Atuahene (2010: 768), Zimbabwe set the blueprint for Southern Africa's political transition when it expropriated land subject to compensation; this resulted in land reform being negotiated in Namibia and South Africa. One may argue, however, that the FTRP inspired the land debate in South Africa.

3.3.5 Lessons learnt

Prior to colonialisation, Namibia practised subsistence farming, in order to provide for themselves and their families. During colonialism, the colonial government expropriated land which they occupied and on which they practised subsistence farming. This compromised their well-being especially because they depended on land for survival. During the transition to independence, the government adopted land reform and the land issue was on the agenda. Land was redistributed, thus stimulating subsistence and commercial farming, since more natives had land to practise farming. This worked for Namibia, since natives engaged in commercial production that would also contribute to the economy. This has had significant outcomes for the country, as agriculture in Namibia contributes approximately 5% to the national Gross Domestic Product, and 80% of the rural population still engages in subsistence farming, which also contributes to food security in the country (Simasiku & Sheefeni, 2017: 41).

Redistributive reform did not work for Namibia, due to the lack of prioritisation as well as other issues that resulted in the slow progress in Namibia. One could argue that, if Namibia prioritised redistributive reform and had capital to fund the initiative, it would have had better success in the country.

4. CONSIDERATIONS FOR LAND REFORM IN SOUTH AFRICA

4.1 Significance of legislation

The significance of South African legislation is that it can be used to redress spatial inequality and land-related issues, without altering it or enacting land expropriation without compensation.

4.1.1 Constitution

Section 25 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (No. 108 of 1996) is the section whereby land expropriation is accommodated. Land expropriation without compensation is often regarded as not accommodated in the Constitution; hence, the argument to amend it (RSA, 1996: 11).

However, it is worth noting that certain subsections may be used in synergy to argue that land expropriation without compensation is accommodated by the Constitution. Section 25(2)(b) may be cancelled by Section 25(2)(a), whereby land may be expropriated for a public purpose, and compensation may be regarded as for a public interest on the basis that it is approved by a court.

Section 25(3) read with Section 25(4) can be interpreted as property or land being expropriated for land reform or redistributive purposes, and the amount of compensation will reflect the history of dispossession and the current use of the land as well as the purpose of the expropriation. The purpose of expropriation could be regarded as sufficient for compensation.

Section 25(8) is the most accommodating of land expropriation without compensation, especially since it stipulates that the provisions of the Property Clause may be overruled on the basis that the state acquires land and other resources for redressing past injustices, on the basis of Section 36(1), which outlines the limitations of rights in the constitution. This means that the state may acquire land and other resources for redressing past injustices on the basis that the state has such resources.

Land expropriation without compensation is reinforced by the protection provided by Section 25(2) (a) read with Sections 25(3), 25(4) (a) and 25(8) when it is viewed as progressing societal interests of the broad public as well as progressing the Constitution's commitment to land reform as a manner of redressing the injustices that marginalised people experienced with equitable access to land. It can be argued that land redistribution is in the public interest.

Section 25(3) is also in accord with Sections 25(2)(b), 25(4)(a) and 25(8) that suggest that the purpose of compensation must be flexible with respect to an equitable balance between the public interest and the interests of those affected, and considering the historical context of the oppressive systems and the constitutional principles of social justice and transformation. Therefore, one could argue that the Constitution does not need to be amended, especially if it is read and interpreted in synergy for redistributive purposes (Jankielsohn & Duvenhage, 2018: 1).

4.1.2 Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (SPLUMA) (No. 16 of 2013)

SPLUMA (No. 16 of 2013) can be used to achieve spatial justice of land instead of expropriating land without compensation. Chapter 2, Section 7 (a) of SPLUMA (No. 16 of 2013) outlines the principle of spatial justice, which relates to the promotion of access to land parcels located near key nodal or corridor areas in terms of a municipality's suite of plans such as the spatial development framework (RSA, 2013: 2). One of the premises of this statute is to address past spatial and regulatory imbalances, since several people in South Africa continue to reside and work in places defined and influenced by past spatial planning and land-use laws and practices based on racial inequality, segregation, and unsustainable settlement patterns.

Therefore, in order to do that, those people who are outlined in the preambles of SPLUMA (No. 16 of 2013) should be given access to land that has resources. Such areas are often located near nodal or corridor areas. Hence, this chapter in the statute may be used to define conditions for developers to address spatial justice. A practical example of this would be a development application, whereby developers stipulate how they would address spatial justice within their overall development plans. This would ensure that SPLUMA (No. 16 of 2013) is utilised intensively.

4.1.3 Draft Expropriation Bill (2019)

The 2019 Draft Expropriation Bill is aligned with Section 25 of the Constitution, since it asserts expropriation with compensation (RSA, 2019: 118). Once enacted, this Draft Bill will repeal the Expropriation Act of 1975 and the amendments. One could argue that the reason why the draft bill maintains the preambles of the Constitution and is aligned with Section 25 of the Constitution is that it does not want to cause any political confusion that will implicate the socioeconomic aspects of the country.

This could be contributed by the reflections from other Southern African countries. In order to prevent a political rhetoric, this Bill takes into consideration the property clause and further details the process of land expropriation and compensation. One could also argue that the reason why the Draft Expropriation Bill is consistent is to mitigate the concerns raised by the land-reform panel. One of the concerns was that land expropriation without compensation could cause food insecurity, due to shortfalls in production.

Agricultural production is vital for food security purposes, as it is a source of income for the majority of rural households, especially because of the highly variable nature of domestic production, restricted tradability of food staples, and foreign exchange constraints related to the ability to purchase imports (Baiphethi & Jacobs, 2009: 460). The panel of advisors on land reform have argued that land expropriation without compensation would have negative outcomes if it affects agricultural production and markets, especially since agricultural production is the main source of livelihood for approximately 86% of rural people in Southern Africa (Worth & Abdu-Raheem, 2011: 93).

4.1.4 Effective spatial planning

The land debate has been centred on constitutional and economic issues. However, the impacts that other disciplines may experience have not been interrogated. It is for that reason that the historical context of South Africa was outlined, as it revealed how the spatial framework was utilised as a tool to ensure racial separation. It is significant, as Van Wyk (2012: 16) outlines, that land is crucial for planning. Hence, if the land debate is to be implemented, it is important to plan accordingly for it in a manner that the spatial framework would be used as a tool to address spatial inequality and the issue of land.

The evaluation of Zimbabwe and Namibia that had similar processes taking place as in South Africa, revealed that planning is significant not only for redistributive purposes but also to create spatial plans that would address spatial inequality. The lessons learnt from Zimbabwe revealed that the expropriation-based land reform had negative outcomes, due to the manner in which it was implemented. Hence, the proposal for using SPLUMA (No. 16 of 2013) to address spatial inequality and redistribute land by using all the principles to propose development.

One could argue that using SPLUMA aligned to strategic planning would be a systematic consideration for implementing expropriation-based land reform in South Africa.

5. CONCLUSION

Land expropriation without compensation has been rallied in parliament as the next phase for land reform in South Africa. However, it has not been outlined from a built-environment context. It was important to use the semi-systematic literature review, since content analysis provided an orderly and objective means of evaluating the history of land, especially the process of land expropriation in Southern African countries that were utilised in this study. This method categorised the evolution of land into distinct themes such as the transition to democracy/ transition to independence; land reform, and expropriation-based land reform, in order to reflect on the implications that Zimbabwe and Namibia experienced.

The use of Zimbabwe and Namibia demonstrated the similarities that these countries experienced. The approaches they adopted are among some of the reasons why they function the way they do nowadays. The radical implementation of land reform in Zimbabwe had negative outcomes, and this resulted in the country not receiving much support from donor countries or international financial institutes. Namibia abandoned the willing buyer-willing seller principle for retributive purposes, and like Section 25, it implemented expropriation-based land reform with compensation. One may argue that it is significant for South Africa to draw from both these countries and to develop a systematic consideration for implementing expropriation-based land reform that is distinct to South Africa. This would mean that South Africa would prioritise the land initiative and secure funding in order for it to succeed. It will also require effective planning and strategising from the built environment as a proactive umbrella for various disciplines. As demonstrated, the Property Clause does not require amendment if it is interpreted in synergy.

REFERENCES

ATUAHENE, B. 2010. Property and transitional Justice. UCLA Law Review Discourse, 58, pp. 65-93. [ Links ]

BAIPHETHI, M.N. & JACOBS, P.T. 2009. The contribution of subsistence farming to food security in South Africa. Agrekon, 48(4), pp. 459-482. [ Links ]

BARDHAN, P. & MOOKHERJEE, D. 2006. Decentralization and local governance in developing countries: A comparative perspective. Volume 1. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [ Links ]

BENGTSSON, M. 2016. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. Nursing Plus Open, 2, pp. 8-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001 [ Links ]

BERRISFORD, S. 2011. Unravelling apartheid spatial planning legislation in South Africa. Urban Forum, 22(3), pp. 247-263. [ Links ]

BRAUN, V. & CLARKE, V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2006), pp. 77-101. DOI 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

CHILUNJIKA, A. & UWIZEYIMANA, D.E. 2015. Shifts in the Zimbabwean land reform discourse from 1980 to the present. African Journal of Public Affairs, 8(3), pp.130-144. [ Links ]

CLARK, N.L. & WORGER, W.H. 2016. South Africa: The rise and fall of apartheid. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

DAVIES, R.J. 1981. The spatial formation of the South African city. GeoJournal, 2(2), pp. 59-72. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF LAND AFFAIRS. 2005. Land Affairs Annual Report 1 April 2004-31 March 2005. (Online). Available at: <http://www.ruraldevelopment.gov.za/pubNcations/annual-report/file/49-department-of-land-affairs-annual-report-1-april-2004-31-march-2005> [Accessed: 7 July 2019]. [ Links ]

DE VILLIERS, B. 2003. Land reform: Issues and challenges. A comparative overview of experiences in Zimbabwe, Namibia, South Africa and Australia. Johannesburg: Konrad Adenauer Foundation. [ Links ]

DLAMINI, S. 2014. Taking land reform seriously: From willing seller-willing buyer to expropriation. Unpublished PhD thesis. Cape Town: University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION RESOLUTION. 2017. Report of the 54th National Conference Resolution on Land Redistribution. (Online). Available at: <https://joeslovo.anc.org.za/sites/default/files/docs/ANC%20 54th_National_Conference_Report%20 and%Resolutions.pdf> [Accessed:30 October 2019]. [ Links ]

ERLINGSSON, C. & BRYSIEWICZ, P. 2017. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. African Journal of Emergency Medicine, 7(3), pp. 93-99. [ Links ]

FEINSTEIN, C.H. 2005. An economic history of South Africa: Conquest, discrimination, and development. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

GIBSON, J.L. 2009. Overcoming historical injustices: Land reconciliation in South Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

HARDEN, A. & THOMAS, J. 2010. Mixed methods and systematic reviews: Examples and emerging issues. In: Tashakkori, A. & Teddlie, C. (Eds). SAGE handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 749-774. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781506335193.n29 [ Links ]

HELLUM, A. & DERMAN, B. 2004. Land reform and human rights in contemporary Zimbabwe: Balancing individual and social justice through an integrated human rights framework. World Development, 32(10), pp. 1785-1805. [ Links ]

HOUSTON, G., MATI, S., SEABE, D., PEIRES, J., WEBB, D., DUMISA, S., SAUSI, K., MBENGA, B., MANSON, A. & POPHIWA, N. 2014. The liberation struggle and liberation heritage sites in South Africa. Report prepared for the National Heritage Council, HSRC. [ Links ]

JANKIELSOHN, R. & DUVENHAGE, A. 2018. Radical land reform in South Africa - A comparative perspective? Journal for Contemporary History, 42(2), pp.1-23. [ Links ]

KEPE, T. & COUSINS, B. 2002. Radical land reform is key to sustainable rural development in South Africa. Policy Brief 3. Bellville: Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, University of the Western Cape, pp. 1-4. [ Links ]

KEPE, T. & HALL, R. 2016. Land redistribution in South Africa. (Online). Available at: <https://www.parliament.gov.za/storage/app/media/ Pages/2017/october/High_Level_Panel/ Commissioned_Report_land/ Commissioned_Report_on_Land_ Redistribution_Kepe_and_Hall.pdf> [Accessed: 25 October 2019]. [ Links ]

KEPE, T., WYNBERG, R. & ELLIS, W. 2005. Land reform and biodiversity conservation in South Africa: Complementary or in conflict? The International Journal of Biodiversity Science and Management, 1(1), pp. 3-16. [ Links ]

KHUZWAYO, T.S. 1998. The logic of integrated development planning and institutional relationships: The case of KwaDukuza. Unpublished PhD thesis. Durban: University of Natal. [ Links ]

LAND AUDIT REPORT. 2017. (Online). Available at: <http://www.ruraldevelopment.gov.za/publications/ land-audit-report/flle/6126> [Accessed: 30 October 2019]. [ Links ]

MABIN, A. 1992. Comprehensive segregation: The origins of the Group Areas Act and its planning apparatuses. Journal of Southern African Studies, 18(2), pp. 405-429. [ Links ]

MABIN, A. & SMIT, D. 1992. Reconstructing South Africa's cities 1900-2000: A prospectus (or, a cautionary tale). Paper presented at African Studies Seminar, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 18 May. [ Links ]

MASIIWA, M. & CHIPUNGU, L. 2004. Land reform programme in Zimbabwe: Disparity between policy design and implementation. In: Masiiwa, M. (Ed.). Post-independence land reform in Zimbabwe: Controversies and impact on the economy. Harare, Zimbabwe: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung and Institute of Development Studies, University of Zimbabwe, pp.1-24. [ Links ]

MOYO, S. 2001. The land occupation movement and democratisation in Zimbabwe: Contradictions of neoliberalism. Millennium, 30(2), pp. 311-330. [ Links ]

MOYO, S. 2013. Land reform and redistribution in Zimbabwe since 1980. In: Moyo, S. & Chambati, W. (Eds). Land and agrarian reform in Zimbabwe: Beyond White settler capitalism. Dakar: CODESRIA, pp. 29-78. [ Links ]

MURRAY, M.J. 2008. Taming the disorderly city: The spatial landscape of Johannesburg after apartheid. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

NATIONAL CONFERENCE ON LAND REFORM AND THE LAND QUESTION. 1991. Windhoek, 25 June-1 July. (Online). Available at: <http://www.mlr.gov.na/documents/20541/290353/ Land+Conference+Part+1+%28Cover_ Pg+i_iv°/o29+.pdf/f75634e4-cdba-4698-9b1f-5aa976344d05> [Accessed: 30 October 2019]. [ Links ]

NHLABATHI, H. & VAN RENSBURG, D. 2018. SA's land audit makes case for land tax. (Online). Available at: <https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/sas-land-audit-makes-case-for-land-tax-20180204-2> [Accessed: 25 October 2019]. [ Links ]

NTSEBEZA, L. & HALL, R. (Eds). 2007. The land question in South Africa: The challenge of transformation and redistribution. Cape Town: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

PHUHLISANI, N.P.C. 2017. The role of land tenure and governance in reproducing and transforming spatial inequality. (Online). Available at: <https://www.parliament.gov.za/storage/app/media/Pages/2017/october/ High_Level_Panel/Commissioned_ Report_land/Commissioned_Report_ on_Spatial_Inequality.pdf.> [Accessed: 25 October 2019]. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA. 1995. Agricultural (Commercial) Land Reform Act 6 of 1995. (Online). Available at: <https://www.lac.org.na/laws/annoSTAT/Agricultural%20 (Commercial)%20Land%20Reform%20Act%206%20of%201995.pdf> [Accessed: 30 October 2019]. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA. 2001. Agricultural (Commercial) Land Reform Second Amendment Act 2 of 2001. (Online). Available at: <https://www.npc.gov.na/downloads/Laws%20of%20 Namibia%20(By%20year)/Year%202001/No.%202%20of%202001%20 Agricultural%20(Commercial)%20 Land%20Reform%20Second%20 Amendment%20Act.pdf> [Accessed: 29 October 2019]. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA. 2003. Amended Agricultural (Commercial) Land Reform Act of 2003. (Online). Available at: <http://www.the-eis.com/data/literature/ACT_2003_12_19%20 Agricultural%20Commercial%20 Land%20Reform%202nd%20 Amendment.pdf> [Accessed: 29 October 2019]. [ Links ]

ROSSET, P., PATEL, R. & COURVILLE, M. (Eds). 2006. Promised land: Competing visions of agrarian reform. New York: Food First Books. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 1913. Natives Land Act, No. 27 of 1913. (Online). Available at: <http://www.ruraldevelopment.gov.za/phoca download/1913/nativelandact27of1913.pdf> [Accessed: 30 October 2019]. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 1950. Group Areas Act, No. 41 of 1950. (Online). Available at: <https://blogs.loc.gov/law/flles/2014/01/ Group-Areas-Act-1950.pdf> [Accessed:25 October 2019]. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 1975. Expropriation Act, No. 63 of 1975. (Online). Available at: <http://sagc.org.za/pdf/legislation/Expropriation%20Act%2063%20 of%201975.pdf> [Accessed:30 October 2019]. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 1996. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. (Online). Available at: <https://www.gov.za/documents/constitution-republic-south-africa-1996> [Accessed: 30 October 2019]. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2013. Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act, No. 16 of 2013. (Online). Available at: https://www.sacplan.org.za/documents/SpatialPl anningandLandUseManagementAct2013Act16of2013.pdf> [Accessed: 30 October 2019]. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2019. Draft Expropriation Bill. (Online). Available at: <https://www.gov.za/sites/default/flles/gcis_document/201812/42127gon1409s.pdf> [Accessed: 30 October 2019]. [ Links ]

SIHLOBO, W. & KAPUYA, T. 2018. Special report: The truth about land ownership in South Africa. (Online). Available at: <https://www.businesslive.co.za/rdm/politics/2018-07-23-special-report-the-truth-about-land-ownership-in-south-africa/> [Accessed: 27 October 2019). [ Links ]

SIMASIKU, C. & SHEEFENI, J.P. 2017. Agricultural exports and economic growth in Namibia. European Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 4(1), pp. 41-50. [ Links ]

SMIT, D. 1992. The urban foundation: Transformation possibilities. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, (18-19), pp. 35-42. [ Links ]

SNYDER, H. 2019. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, pp. 333-339. [ Links ]

THOMAS, N.H. 2003. Land reform in Zimbabwe. Third World Quarterly, 24(4), pp. 691-712. [ Links ]

TREEGER, C. 2004. Legal analysis of farmland expropriation in Namibia. Constitution, 1, p. 16. [ Links ]

VAN AMERINGEN, M. 1995. Urban policy: A report from the Mission on Urban Policy for a Democratic South Africa. International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, ON, Canada. [ Links ]

VAN WYK, J. 2012. Planning law. Cape Town: Juta. [ Links ]

VAN WYK, J. 2013. The legacy of the 1913 Black Land Act for spatial planning. Southern African Public Law, 28(1), pp.91-105. [ Links ]

WHITE PAPER ON SOUTH AFRICAN LAND POLICY 1997. Department of Land Affairs. (Online). Available at: <http://www.ruraldevelopment.gov.za/phocadownload/WhitePapers/whitepaperlandreform.pdf> [Accessed: 28 October 2019]. [ Links ]

WHITE PAPER ON LOCAL GOVERNMENT. 1998. Ministry of Provincial Affairs and Constitutional Development. (Online). Available at: http://www.cogta.gov.za/cgta_2016/wpcontent/uploads/2016/06/whitepaper_on_Local-Gov_1998.pdf> [Accessed: 28 October 2019]. [ Links ]

WOLPE, H. 1972. Capitalism and cheap labour-power in South Africa: From segregation to apartheid. Economy and Society, 1(4), pp. 425-456. [ Links ]

WORTH, S.H. & ABDU-RAHEEM, K.A. 2011. Household food security in South Africa: Evaluating extension's paradigms relative to the current food security and development goals. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension, 39(2), pp. 91-103. [ Links ]

Peer reviewed and revised October 2019

Published December 2019

* The author declared no conflict of interest for this title or article