Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Town and Regional Planning

On-line version ISSN 2415-0495

Print version ISSN 1012-280X

Town reg. plan. (Online) vol.75 Bloemfontein 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp75i1.5

ARTICLES

Examining women's access to rural land in UMnini Trust traditional area of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

'n ondersoek na vroue se toelating tot landelike gebiede in die tradisionele umnini trust in Kwazulu-Natal, Suid-Afrika

Hlahlobo ea methati e lateloang ke basali hofumana lefatshe mahaenga umnini trust, Kwa-Zulu Natala, Afrika Borwa

Nontobeko KhuzwayoI; Lovemore ChipunguII; Hangwelani MagidimishaIII; Martin LewisIV

IMaster of Town and Regional Planning Graduate, UKZN Barry Hertzog Park, no. 7, Cresswell Avenue, Newcastle, 2940. Phone: +27 797119234, e-mail: <valeriekhuzwayo@gmail.com>

IISenior Lecturer, School of the Built Environment and Development Studies, UKZN, Durban, 4042. Phone: +27 31 2603801, e-mail: <chipungu@ukzn.ac.za>

IIIAcademic Leader for Planning and Housing, School of the Built Environment and Development Studies, UKZN, Durban, 4042. Phone: +27 31 2601353, e-mail: <MagidimishaH@ukzn.ac.za>

IVChief Executive Officer, The South African Council for Planners (SACPLAN), PO Box 1084, Halfway House, Midrand, 1685. Phone: +27 829540925, e-mail: <mlewis@sacplan.co.za>

ABSTRACT

This article examines land tenure reform in South Africa with a focus on women in the rural areas of KwaZulu-Natal. Using the case study of UMnini Trust Traditional Area, it critically analyses the extent to which current land reform programmes address gender disparities - especially equal access to land and secure land rights by women. In order to provide an insight into this issue, this study used both secondary and primary data sources. The major findings emanating from this study suggest that land remains an emotive issue in rural South Africa, especially among women who are side-lined by government intervention measures. Previous policies and legislations that purposefully neglected and isolated women as beneficiaries of any developmental initiatives are still very much entrenched in contemporary society. The article concludes by recommending for redesigning as well as implementing policies and legislations that are accommodative of women's plight as far as access to land and security of tenure is concerned.

Keywords: Rural women, land, access, exclusion, customary laws, legislations and policies, traditional leaders

ABSTRAKTE

In hierdie artikel word grondhervorming in Suid-Afrika ondersoek met die klem op vroue in die landelike gebiede van KwaZulu-Natal. Die gevallestudie van die tradisionele gebied UMnini Trust word krities ontleed in die mate waarin die huidige grondhervormingsprogramme geslagsverskille aanspreek - veral gelyke toegang tot grond en veilige grondregte vir vroue. Primêre en sekondêre databronne is in die studie gebruik om insig in hierdie kwessie te verkry. Die belangrikste bevindings uit hierdie studie dui daarop dat grond 'n emosionele saak in landelike Suid-Afrika is, veral onder vroue wat deur die regering se ingryping geraak word. Vorige beleid en wetgewing wat vroue doelbewus verwaarloos en geïsoleer het as begunstigdes van enige ontwikkelingsinisiatiewe, is steeds baie verskans in die hedendaagse samelewing. Die artikel bepleit vir die herontwerp, sowel as die implementering van beleide en wetgewing wat vroue akkommodeer ten opsigte van toegang tot grond en veiligheid van verblyfreg.

Sleutelwoorde: Gewoontereg, grond, landelike vroue, toegang, tradisionele leiers, uitsluiting, wetgewing en beleid

TUMELO

Sengoliloeng sena se hlahloba taba ea ho fetoha hoa land tenure naheng ea Afrika Borwa, haholo-holo mapabi le basali ba lulang mahaeng a Kwa-zulu-Natala. Ka tshebeliso ea boithuto ba mohlala sebakeng sa UMnini Trust Traditonal Area, sengoliloeng sena se lekola kamoo meralo ea kajeno ea thuo ea lefatshe e ananelang liphapang pakeng tsa banna le basali kateng - haholo-holo tekatekano thuong ea lefatshe mmoho le litokelo tsa basali tabeng ena. Ele ho fumana linthla kemo tse pharaletseng, boithuto bona bo entsoe ka tshebeliso ea mehloli ea manthla le e meng thlahisoleseling. Se fumanoeng boithutong bona ke hore mahaeng a Afrika Borwa, taba ea lefatshe le basali e hlokoa ho eloa hloko, haholo hobane meralo ea lefatshe e etsoang ke 'muso ha e ananele basali. Le kajeno, litloaelo tsa melao e fetileng, e sa ananeleleng le hona ho kenyeletsa basali li ntse li iponahatsa ka botebo metseng ea rona. Sengoliloeng sena se phethela ka ho eletsa hore melao e etsoang mabapi le lefatshe e kenyeletse le hona ho ananela lithloko tsa basali.

1. INTRODUCTION

Land is one of the key resources that determine women's living standards, their economic empowerment and, to a certain extent, their struggle for equity and equality (Weideman, 2004: 428).

Using the case of the Global South1and Northern Tanzania women's experience, Goldman, Davis and Little (2016: 781) observed that women continually remain disfranchised in access to land. Similarly, women in most of the rural areas of South Africa have long been grappling with land issues such as lack of land and tenure security. They are continuously viewed and perceived as inferior, with minor roles in both society and land-related matters (Doss, Kovarik, Peterman, Quisumbing & Van den Bold, 2013: 31). These limitations and discriminations have influenced the prevalent nature of limited women's ownership and control of land, poverty, marital violence, and weak domestic economic power for women in most of the rural areas of South Africa (Daniels, 2016). Najjar (2017: 1) further argues that women continue to battle with issue of traditional-political illegal land acquisition by the opposite gender that limit their rights for household empowerment and access to land.

Abdulkadir and Abdullahi (2018: 5396) noted that trado-historical culture landownership preference that promotes male landownership limits female access. Despite these challenges, women are actively involved in food production, usually make a significant contribution towards the economic survival of their families, and invest valuable resources towards the livelihood of their families (Doss et al., 2013: 31-32). As such, they are major contributors to agricultural production on land that they do not own or manage.

The 1997 White Paper on South African Land Policy concedes that a key contributing factor to women's inability to overcome poverty is lack of access to, and rights in land (DLA, 1997). Legislations and policies in South Africa put great emphasis on the issue of gender equality and landownership. For example, the Green Paper on Land Reform (DRDLR, 2011) expresses a clear commitment to end discrimination and to ensure gender equity in landownership. The Bill of Rights in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa also places an obligation on the government to take reasonable legislative and other measures to ensure that equality includes the full and equal enjoyment of all rights (including the right to land) and freedom (RSA, 1996). Furthermore, the Department of Land Affairs' gender policy framework (DLA, 1999) alludes that much more attention should be directed to meeting women's needs and concerns, because women have much less power and authority than men. Failure to do such could aggravate existing gender inequities in the allocation of land and its productive use. There is thus a clear commitment to gender equity as established laws and policies, governing women's land rights and access to land, appear to be largely adequate. However, lack of political will in terms of such laws and policies hampers their implementation (Weideman, 2004: 428).

It is thus important to analyse the extent to which current South African land reform programmes, laws and policies address gender disparities, with a focus on providing women with equal access to land and security of tenure.

2. A CONCEPTUAL OVERVIEW OF LAND TENURE

A related theory that emphasises property rights and that has dominated most of the discussions on land tenure reforms in Africa is the evolutionary theory of land rights (ETLR), extensively discussed by Platteau (1996: 29). According to this theory, owing to population pressures together with the commercialisation of agriculture, land becomes increasingly scarce, resulting in land rights being individualised until private property rights emerge. For proponents of ETLR, the progression towards private tenure is inevitable, since institutions evolving maximise benefits and minimise costs.

The move towards private or individual land tenure rights is beneficial to development, as it improves the security of tenure, accelerates investments in land, creates a market for land, and reallocates resources to more efficient producers. Brasselle, Gaspar and Platteau (2002: 400) identify three channels through which more secure property rights can act as an incentive for investments in agriculture. The first is 'the assurance effect', which posits that, when farmers are secure in their rights to land, either through ownership or long-term lease, they have an incentive to undertake investments in the land, because the returns from a long-term investment are likely to be higher. The second channel, the 'realisability effect' postulates that, as a result of security of tenure, a market for land may develop, making it possible for land to be easily converted to liquid assets through sales. In such situations, farmers have an incentive to invest in land improvements, in order to increase the value of their land in the exchange. The third channel is the 'collateralisation effect', whereby secure title gives the land collateral value and increases access to credit. The policy implication of the ETLR is that governments should take steps to put in place formal systems of individualised land tenure systems. For a long time, this was the staple policy advice and policy support given to developing countries by the international development community, including the World Bank and the UK's Department for International Development (DFID).2

Although the ETLR has been subjected to withering criticism from a number of scholars, there is considerable evidence to support this proposition in Africa. According to Platteau (1996: 32), in Africa, the ETLR is "grounded in the well-ascertained fact of considerable flexibility of indigenous land tenure arrangements in the region". For example, Kenya provided much of the fodder for experimentation with the ETLR following the Swynnerton Plan of 1954 which was aimed at creating a class of Black commercial farmers through registration of rights for Africans to land in individual freehold title. The policy, which has continued in recent land reform programmes in Kenya, followed market-based principles and seeks to formally register all land rights with the aim of securing and clarifying all land rights under statutory laws to encourage greater investments in land and agriculture.

However, the practical application of the ETLR has been fraught with shortcomings. One shortcoming pointed out by Platteau (1996: 37) is that registration of title, far from increasing security, may increase uncertainty and conflict or litigation over land rights. The reason for this is that land registration may create security and reduce transactions costs for one group, with others relying on customary land tenure systems, which, in essence, may create uncertainty. This was especially true of women, who, under customary tenure, may not have ownership rights, since their rights are considered secondary, but have usufructuary access or rights to land.

Owing to weak financial power and male preference, women are unlikely to enjoy the benefits of land registration and acquire land in the marketplace. The other criticism of the ETLR is that it ignores the complex and pluralistic land tenure systems found in most of the regions of Africa (Whitehead & Tsikata, 2003: 74). Demarcations between communal and individual tenure rarely fit most of the African systems where farmers practise mixed farming (cropping and herding), sometimes leading to overlapping land rights. On this note, Ehwi, Tyler and Morrison (2018: 1-3) argue against the efficacy of the ETLR in mainly organic and rudimentary rural Africa. The argument is that the vulnerable (rural women in this regard) remain increasingly exposed to land capture and 'politicisation' in favour of a particular class and gender by the ruling group (which includes the formal titling institutions and customary power holders). This often results into multiple land sales and ownership (Zakaria, 2019: 4) and 'heterogeneity' in private landownership and use (Perz, Hoelle, Rocha, Passos, Leita, Cortes, Carvalho & Barnes, 2017: 231).

Furthermore, the static view of customary tenure ignores the fact that it does adapt over time to meet the needs of the community (Bassett, 2007: 3-4). As noted by Stamm (2009: 33-34), customary or communal tenure systems at the local level are complex and dynamic, and rights may be held by individual persons or a group of persons. Another criticism of the ETLR revolves around policy implications. There are practical administrative challenges with regard to recording titles and changes in landownership (UN 1996:8), as many African countries lack the personnel or resources required to carry out the bureaucratic demands of registering titles. As a result of this, Byamugisha (2013: 2) estimates that only roughly 10% of rural land in sub-Saharan Africa is registered.

In the context of this article and in terms of the evolutional theory of land rights, there is a direct relationship between land reform and economic development. The theory states that agricultural development (particularly in undeveloped countries) has a vital role to play in economic development (Zarin & Bujang, 1994: 9). Wahab, Popoola and Magidimisha (2018: 173) also identified the livelihood stressors that characterise limited access of farmers to land for farming. Aligned to this is the reduction in the poverty dynamics of sub-Saharan Africa, which is dependent on improving the productivity of small farm holders, many of whom are women and have limited access (Larson, Muraoka & Otsuka, 2016: 39).

2.1 Marital property regimes

In many rural areas, marriage is the primary means whereby women obtain access to land (Namubiru-Mwaura, 2014: 11). Although rights to access land accrue to women in their spouse's community, they do not extend to full ownership of land in the event of divorce or death of the husband. Marital regimes define the ownership of property/ land within a household system or structure (Deere, Alvarado & Twyman, 2010: 4). In this regard, where a woman did not own any property or land individually (Bunelli, Doss & Kieran, 2015: 11), she is often left a destitute, due to lack of land.

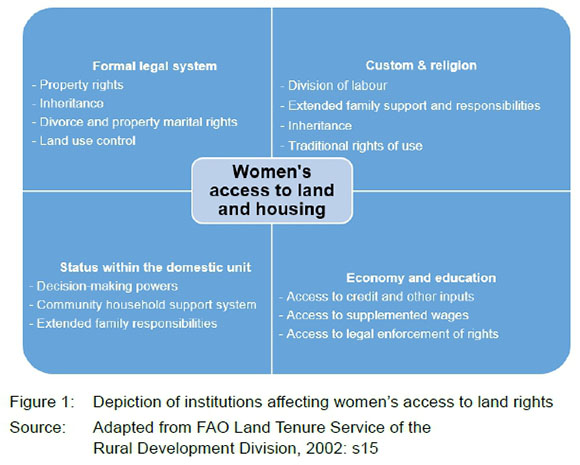

Studies by Deere et al. (2010: 4) and Wily (2011: 4) state that, in a patrilineal rural marriage, a woman's access to land is through her husband, and land inheritance is strictly through the male lineage. Divorced women lose the right to cultivate their fields and thus have to return to their own families. Upon the death of a woman's husband, she can use the land owned by her husband as long as she remains unmarried. According to Bunelli et al. (2015: 3), as the sons come of age, she shares her land with them, thus diluting her ownership rights. Evidence from Zambia (Dillon & Voena, 2018: 455) and Rwanda (Bayisenge, Hojer & Espling, 2015: 84) further show that there are instances where land rights are revoked in the advent of the husband's death. This evidence posits that there exists a swift decline and often total loss of investments on land in the advent of the spouse's death. Furthermore, in regions where polygamy is practised, the registry at the household level worsens the tenure security of numerous households, as the land registration records simply reflect only one of the several households (Bunelli et al., 2015: 15-18). Households of subsequent wives are not included in the registration process, thus depriving them of the corresponding rights to land. In addition, the limited registration of marriages and divorces often intensified the tenure insecurity of women in polygamous situations (Bunelli et al., 2015: 15-18) (Figure 1).

2.2 A global overview of land and tenure systems

One of the contentious issues that worsen women's position with regards to accessing land mainly in many developing countries, especially African countries, is dual to tenure systems and multiple legal frameworks, which make legal coherence challenging, as there are often discrepancies between statutory and customary law. Land tenure is affected by many and often contradictory sets of rules, laws, customs, traditions, and perceptions, as land rights belong to not one legal arena, but are rather fixed through various and sometimes contradictory bodies of law ranging from land titling law to constitutional law to marriage and divorce law as well as a mix of customary and religious laws (Namubiru-Mwaura, 2014: 2-3).

These multiple legal frameworks can create contradictions and confusion in what women's rights are and which ones should be recognised. Hence, many of these rules continue to reinforce gender inequities.

Razavi (2005: 1) observes that the new generation of land reforms introduced to address gender inequality do not necessarily create more gender equitable environments than earlier efforts, even though women's ability to gain independent access to land is increasingly on the statutes, as land reform policies remain gender blind. For the vast majority of rural women, land tenure is complicated, with access and ownership of land often layered with barriers present in their daily realities discriminatory social dynamics and strata, unresponsive legal systems, lack of economic opportunities, and lack of voice in decision-making.

Governments and civil society have attempted to implement land regulations that seek to improve women's land rights (Lastarría-Cornhiel & García-Frías, 2005: 2). Nevertheless, most of the initiatives developed to promote land-reform programmes continue to underestimate the implications that gender-asymmetric land policies entail for women (Jacobs, 2002: 889), which still leave them marginalised (Stiftung, 2009: 5). It is important to note that laws alone do not suffice to secure women's access to land. The effectiveness of laws depends on awareness about them, the abilities to invoke them, and to what extent cultural norms and traditions are practised and followed (Ravnborg & Spichiger, 2014: 421).

3. WOMEN AND LAND IN SOUTH AFRICA -A GENERAL OVERVIEW

Women in South Africa remain the worst affected when it comes to cases of land dispossession (Waldron, 2018: 251) and insecure land tenure (Claassens, 2014: 5). During the apartheid era in South Africa, Murugani (2013: 2) reported that land was allocated to male farmers in the homelands, disregarding women's prior claims thereto. According to Weideman (2004: 363-365), it was only through legislations introduced in 1985 and again in 1988 in South Africa that rural women were no longer legally considered as minors in land-related matters. However, this new presumed legal status was not necessarily reflected in customary law and practices. Customary law excludes Black women and relegates them to minority status as far as land rights and land ownership are concerned (Weideman, 2004: 365-568).

South Africa consists of a dual land rights system, including statutory land law and communal land law (Murugani, 2013: 4). Statutory land law, as stated in section 25 of the South African Constitution, accords equal rights to women and men (RSA, 1996). Women can, in the case of statutory land law, buy, sell, register, inherit or manage land. In communal land law, which is most relevant in the case of rural areas, women's landownership, in this case, is governed by patriarchal, tribal, or community customs enforced by a local chief or a traditional leader of that rural settlement. Most of the land in rural areas is vested in traditional communities (Cousins & Hornby, 2009: 3), or chief's trust, who, in turn, allocates to citizens and adopted citizens on the basis of need and other social customs (Branson, 2016: 3-5). Popoola and Magidimisha (2019:29) equally argue that traditional chiefs are the main custodians of the rural assets and law executioners.

The majority of customary law is patrilineal; it gives men primary rights to productive resources, and relegates women to secondary beneficiaries (Mutangadura, 2007: 180). In these instances, the land is allocated to the male household head on behalf of his household and women's access to land as secondary beneficiaries whose rights are to cultivate and control what they themselves produce (Yngstrom, 2002: 31-34). Tschirhart, Kabanga and Nichols (2018: 1) noted that rural women usually have a disadvantage in asset (including land) inheritance. Although women are productive in labour and livelihood support for the household, they still exact hardly any or no control over land, on which they work and from which they produce (Bryceson, 2019: 60). Based on patriarchal attitudes of men that are enhancing the effect of customary laws and the assumed "weak capacity of the women in resource control", the only means for women to limited and supervised land access remains a conscious or unconscious negotiation through the patriarchy system, which is supported by customary law (Umaru Baba & Van der Horst, 2018: 8).

An issue that is evident in the case of conflicting rights between statutory and customary law is that rural laws have maintained the status of women as secondary citizens and still regard them as social and legal minors who cannot contract or own land individually. Existing literature on gender and land rights further highlights the challenge of translating legal reforms into real change at the local level, where state reform efforts frequently conflict with customary institutions and local interests (Lavers, 2017: 2). Thus, while legislation can be an important starting point for transforming local practices, implementation is where the real struggle begins (Daley & Englert 2010, cited by Lavers 2017: 3).

4. STUDY AREA

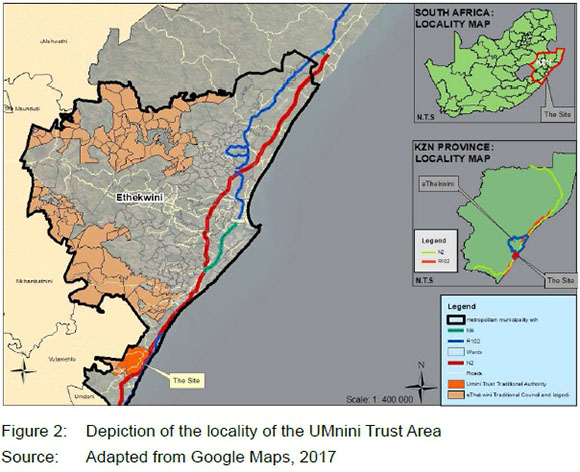

The UMnini Traditional Council is administered by the Ingonyama Trust Board within eThekwini Municipality in Durban. UMnini is located some 40 kilometres south-west of the Durban CBD within Ward 98 and Ward 99 (Figure 2). The area, which is 400 ha in size, is bordered by the Indian Ocean in the east, Mfume Mission and privately owned land in the west, the Umsimbazi River in the north, and the Umkomasi River in the south (UMnini LADP, 2006). Historical evidence shows that the land in UMnini area was granted to the traditional leadership by the British Empire on 27 May 1858 in exchange for confiscated ancestral land next to the Durban port (UMnini LADP, 2006).

The 2011 census further shows that the area is home to an overall population of 84 083 people, with a density of 210 persons/ ha - many of whom are women accounting for approximately 52% of the total population. Literacy rates in the UMnini area are approximately 60%, with individuals having completed grades ranging from 5 to 7 and above. The employment status is very low, with approximately 57% of the population in the case study area being unemployed economically active, while only 17% being unemployed and 26% employed (StatsSA, 2011).This, in turn, impacts significantly on their income levels, with an estimated 17% of the employed cohort receiving an income ranging between R9 601 and R19 600 per annum, while 15% earn under R1 600.

5. METHODOLOGY

This study focused on understanding access and land tenure in the rural areas, and the extent to which current land reform programmes address gender disparities - especially equal access to land and secure land rights for women. The case study (the women of the UMnini Trust Traditional Area of KwaZulu-Natal) was selected, in order to gain insight into women's demographic profile; their perceptions on landownership and land rights, challenges of landownership, gender inequalities, and their understanding of land policies. The study combined the gathering of quantitative data (survey questionnaires) and qualitative data obtained through interrogating the experiences of women and community members (interviews), in order to examine land tenure reform for women in South Africa.

5.1 Data collection

Data for this article was collected from various sources, among which are interviews with key informants, and a structured questionnaire for focus-group interviews in the study area.

First, during 2017, the study area was visited to observe and interview community members. During this time, questionnaires were administered to 14 UMnini female resident households, and nine UMnini residents who attended a Women and Land Rights Discrimination Conference. The questionnaire consisted of three sections. The first section collected the individual and family details of the interviewees; the second section was designed to recognise the general patterns of landownership, food security and livelihood options. The third section was specially designed to gain information on women's status within the context of landownership, their knowledge of different legal provisions, their rights to land, and the existing challenges. The questionnaire used both closed-ended and open-ended questions.

Secondly, eight key informants (including rights activists, traditional authorities, legal experts, and various government officials) were also interviewed, in order to gain in-depth information on existing legal provisions and weaknesses in the legal system concerning opportunities for women to claim land rights, comparing them with past legal practices. The government official interview schedule included 16 questions and the traditional authority interview schedule included 20 questions - both were meant to establish societal perceptions of women's landownership.

Existing literature and documents in the form of law and policy documents, monographs, and planning information across government institutions were also sourced.

5.2 Sampling and size

The study adopted a non-probability purposive sampling method using the criteria of ethnicity, class, age and gender (specifically Black, middle-aged to elderly, poor, rural females). These women were from both female-headed and male-headed households. Selection perimeters resulted in a sample size of 43, including 30 UMnini female residents, five UMnini male residents, and eight key informants within relevant government departments. Taking into account that women represent 43 723 of the total UMnini population, a sample size of 43 is very low, but it covers a variety of rural households and individuals (women) in a small cluster of the ward. It was mainly chosen because of the strong patriarchal structures that prevail in the area. Although the sample size is not valid and not within the recommended sample size of 340 for a population equal to or over 40 000 (Krejcie & Morgan, 1970: 608), the cluster chosen coupled with the critical patriarchic issues substantiates its size.

5.3 Data analysis and interpretation of findings

Content analysis (selective coding) was used to examine and group components on land tenure reform for women outcomes mentioned in the in-depth interviews as well as from the literature review on land policies and land laws. The scissor-and-sort technique (Stewart, Shamdasani & Rook, 2007: 116-117) was used to select segments from the transcripts of the interviews which were then categorised, showing the components: demographic profile; their perceptions on landownership and land rights; challenges of landownership; gender inequalities; their understanding of land policies, and lessons learned.

5.4 Limitations

It is important to note that the study was conducted only in the UMnini Trust Traditional Area of KwaZulu-Natal; hence, the findings cannot be generalised for eThekwini Municipality in the Durban region. The selected sample is very small, due to strong patriarchal structures that restricted rural women from participating in the interviews.

6. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

6.1 Demographic profile of participants

In terms of marital status, the interview results revealed that 50% of the female respondents in the study area are not married, while 37% are widowed and 13% are married. Most of the women have children as dependants, especially elderly women, who claimed to be guardians of their grandchildren, owing to the children's parents often migrating from the rural area in search of a better life in the city. Approximately 87% of the female respondents surveyed are household heads. This includes both single and widowed females. The remaining 13%, who are married, are titular household heads. As such, married women taking up the role of being household heads does not necessarily mean that they have decision-making powers.

6.2 Perceptions of women's landownership

During the study area visit, it was revealed during the interviews that very few women were willing to speak up about the land-related discussions in the setting based on the effect of the patriarch arrangement on the freedom expression by the women. The patriarch society limits freedom of expression (Mannat, 2018: 85), capacity, productivity, and development of women as a result of a negative monopoly of power by men (Chigbu, 2019: 45).

The interviews revealed that a few women did not seem to care much about landownership, irrespective of whether they were rightful landowners or not. Those with spouses opined that, if their counterparts' names were registered or were under their names, then it meant that they somewhat had equal rights to the same land as their men.

Furthermore, they believed, that having land did not make much of a difference, as most of the decisions regarding land were made by the local chief and males. The inactivity of women in decision-making, according to Dyer (2018: 24) is due to the spatial arrangement that limits a free mode of communication across gender. Dyer (2018: 24) iterates that women And it difficult to communicate in rural meetings in Solomon Islands, due to the communally and culturally gendered communication pattern and arrangement adopted.

Through the interviews, it was revealed that the majority of the women (87%) who were confident to voice their opinions were single or widows. From this result, it can be deduced that divorced women and widows have experienced pre-marriage land rights denial or post-death of spouse land right retrieval. Thus, the ability to speak up is a result of their life experiences. Evans, Mariwah and Antwi (2015: 31) reported that there are usually changes and threats to land rights, mostly among women without sons or children to support them after the death of their husbands. It was also observed that there are instances where women who relocate to other rural areas in the event of their spouse's death And it even more difficult to gain complete free access and rights to land. In addition, land rights are also lost when widows consider remarrying. Chiweshe, Chakona and Helliker (2015: 719-721) mentioned that the worst experience of widows with regards to land is when they are implicated in the death of their husbands. In such instances, even if the land rights belong to the husband or joint ownership, the in-laws or the community might chase the widow away from the land. She thus loses resources, properties and assets she previously enjoyed. Evans (2016: 1372) mentioned that the same experience might happen to single women in some religious local settings. The summary of the argument shows that a single female might not have access to the land of the family or the late father and, in some cases, might simply have access to only half of the land estate, despite its relevance to livelihood sustainability.

Results from the interviews showed that women felt that land rights (access, control, and ownership) are very important in improving their livelihoods. These women indicated that land is an economic tool that builds self-reliance and that, if they own it, they would be in a position to make decisions on their own without depending on any male counterparts. The few male respondents believed that giving women full ownership of land is a threat to their status as men. Some male interviewees claimed that ownership of land is a birthright and that the long-term presence of a woman in a family was not guaranteed as she can marry into a different family, thus not being able to protect the family land. To them, land on which crops are grown is considered to have long-term economic potential, and it can only be owned and protected by men.

Female key informants (one from Non-Governmental Organisations, one from Rural Women's Movement and one from Nonkasa Senior Citizens and Disabled Community Project in UMnini) argued that issues of land are still a major concern, with rural women only having use rights and not control rights. They are thus vulnerable to cases of domestic violence and poverty when men pass away and leave them destitute. Interviewed women in rural UMnini revealed that women faced issues of gender-based violence (physical, social and emotional) from the chief, other male counterparts and parties loyal to the traditional leader. Allen (2018: 2-3) and Lince-Deroche, Shochet, Sibeko, Mdlopane, Pato, Makhubele and Bessenaar (2018: 682) attributed this culture of oppression and harassment on women by men to the South African patriarchal system and the trans-generational economic power configuration of the rural space that men dictate and define events. One representative from the Rural Women's Movement opined

that focus should primarily be on rural women who need land for building and crop and animal farming, in order to achieve food security and tackle poverty, as opposed to urban women whose demand for land is mainly for residential usage.

This case highlights the need for rural women to collaborate towards moving from subsistence farming to commercialisation, in order to escape poverty. A female representative from the DRDLR alluded that subsistence farming should not be perpetuated among women and that, at some point, women need to be allowed to apply for a transitional strategy towards commercial farming. She further noted that there was money in land and that women who own land generate more than rural non-farming women engaged in other activities. As such, women's discrimination with regards to land rights is a constraint when women are engaged in empowering themselves economically.

6.3 Sources of landownership and land rights for women

Findings from the study area show that the acquisition of land, the determination of plot sizes and the types of ownership rights in UMnini are governed by iNkosi Luthuli, who administers and allocates plots of land transferred by the Ingonyama Trust Board (ITB) to most of the residents, with Permission to Occupation Certificates primarily for males. However, these certificates are less formal tenure rights, since they provide recipients with user rights. This basically means that rights to land are derived from the state. Other forms of acquisition are derived from a wide range of customary and religious laws, such as through inheritance. In customary practices, it is recognised that single women can also inherit land through maternal or paternal kinships, and widows also inherit from their late husbands. However, such rights of inheritance are most often conditional on women maintaining their single/ widowhood status. Women in UMnini find that marriage is a primary means to obtain access to land via their husbands' families or lineages. Such access may, however, be lost upon divorce or death of the husband.

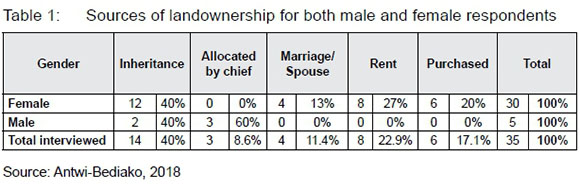

The questionnaire results revealed that, in UMnini, customary norms are more important in determining women's rights than statutory laws. Some 13% of the women stated that they acquired land (use rights) through their spouses or male relatives who acquired their land through the allocation of the chief or inheritance. Thus, in terms of the bundle of rights, women only have privileges to access (that is use rights for farming), but not to control and own land. However, approximately 40% reported having inherited land from their deceased spouse or male relatives - this was normally the case where there were no males in the household. They stated that this way of land acquisition is a never-ending battle, as they are bullied at all times to hand over land to extended family relatives who are males. In the absence of a male figure within female households, the community leader/chief is empowered to allocate the land to men as heads of a household.

Of the surveyed females, approximately 20% claimed to have tried escaping cultural hindrances by purchasing land from the community leader/chief with cash as a way of acquiring land (Table 1). However, this type of allocation by the chief to women was only allowed if they paid for the land as opposed to being allocated land freely in their own rights. Moreover, this form of acquisition seemed to be difficult as chiefs were generally reluctant to sell land to women, especially married women, without their husband's approval. In this case, it is evident, according to Ribot and Peluso (2003: 153-154), that the ability to derive benefits from resources is contingent on social relationships enabling or constraining women's realisation. This also makes it clear that men determine women's rights to access land. Po and Hickey (2018: 252) also mentioned that, in semi-arid Kenya, the relational access is one of the easiest ways for women to bypass the culturally set land resource constraints. Approximately 27% of the women reported that they only have access to land by paying rentals to males who own large plot sizes and were able to accommodate them.

It is clear from Table 1 that nine of the women who purchased land reported that land retrieval by chiefs is inevitable. Antwi-Bediako (2018: 13) observes that, when there is no formal third-party legal agreement between buyers and sellers (Chiefs) and a legal guide inland negotiation and deals, retrieval, grabbing and disputes are inevitable. It was noted that such ownership was capricious, since it depended on the indulgence of the chief who could change his mind at any time, as illustrated by noe respondent: "I purchased the land, but the chief harasses me every time, telling me he has sold it to a higher bidder and I must vacate".

In the case of men, 40% inherited the land and have full ownership rights and access, use, control and making all the major decisions pertaining to land-related matters. They also have relatively larger plot sizes. Most of the men in UMnini have been allocated land by chiefs and have full ownership rights. Although this is the case for men, some of them still suffer from land-grabbing by chiefs who sell their land to developers or the ITB, forcing them to swap 'Permission to Occupy' (PTO) certificates to 40-year lease agreements.

6.4 Challenges women face with regard to landownership in UMnini

Despite the various ways (property inheritance, transfers, and purchase) in which land can be acquired, women in UMnini are still hindered by other factors. First, it was observed that cultural and traditional factors prevail, since customary laws are highly predominant in the area. Secondly, residents are pressurised into converting their PTOs to leases, thus meaning that they would be stripped of their land rights by effectively making them tenants and the chief selling the land of the UMnini people to prospective developers.

Based on this study's results, it can be deduced that challenges faced by women residents of UMnini are complex and interlinked:

• They are forced by the ITB to sign 40-year leases for their ancestral land, over which they have held rights for several years;

• They are dependent on men's assistance to acquire land;

• They lose family land in the advent of death of the male and absence of male family members;

• Their houses are forcefully demolished (by the family in the advent of the death of the husband), and their land is sold by traditional chiefs for higher prices;

• Traditional chiefs and male relatives grab women's land;

• Women lack customary power or authority to voice their concerns;

• Women lack money to approach the court to protect them against such violations of their rights.

The study results further revealed that every UMnini community member is negatively affected by land-grabbing, with women being at greater risk. Women use the land sold by the chief to grow crops mainly in summer. Men use the same land to grow perennial cash crops that are considered to have long-term economic potential. Hence, they tend to be excluded from land-grabbing deals, irrespective of whether they have certificates of occupation or not. This, in essence, suggests that such illegal transactions are not only prompted by gender perspectives derived from customary beliefs, but also by the nature of land usage. The intensity of use can lower chances of eviction or harassment, while seasonal use can warrant harassment.

Key differentiating factors between women and men in UMnini are evident, in that men are at a greater advantage, as they have greater tenure security than women, although the community as a whole is vulnerable to the negligent behaviour of the chiefs' actions and any land loss has a net effect on household food security.

6.5 Gender inequality in land-related policies

Results from the study revealed that there is a lack of platforms in the community that allow women to voice their concerns on land independently. In traditional councils and courts, women always have to be represented by males, as the area maintains patriarchal practices that restrict women from representing themselves. One interviewee mentioned the following: "I asked these chiefs why we have to be represented. Because according to the constitution, we are human beings and we have the full potential of speaking for ourselves. Why do we have to be represented?"

The traditional leader, however, stated that platforms are given but that women do not speak up. Hence, they end up settling with the status quo. In the case of provisions made by traditional leadership towards addressing gender inequalities, the leadership recounted that such provisions do not exist, due to uninformed state of traditional leaders about new democratic frameworks and legislations within the constitution. The state of ignorance of their rights under state and customary systems is also peculiar to women in UMnini.

The study results showed that women with better educational levels are more aware of their rights and are able to interpret policies, compared to those who were less educated.

A women's land rights activist from Rural Women's Movement stated that she has been working for decades to inform women, living in primarily poor, agrarian communities, hours away from major cities, of their rights under the 1996 South African Constitution. She recounted that many rarely question their traditional chiefs, as they are uninformed of their legal rights. One key informant registered her concern when she noted:

"One of my biggest concerns in men representing women in court is that they may not look after women's best interests, because they are looking at things through their patriarchal lenses. I fear that when men go to court it is something completely different from what a woman says is her own needs and aspirations."

The study further investigated the gender sensitivity of the current land tenure reforms. In the case of current government provisions in addressing gender-based inequalities, officials from Land Accountability and Research Centre and the DRDLR highlighted that the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) was ratified by South Africa in December 1995 to empower rural women as a group with special problems (Weideman, 2004: 366).

The women of the Rural Women's Movement (RWM) representing UMnini noted that, because traditional leaders are appointed and not elected, they are undermining democracy. They further attested that the powers given to traditional leaders to impose harsh punishments at their whim are detrimental to the community, especially women.

An official from the Department of Co-Operative Governance and Traditional Affairs (COGTA) also recounted that patriarchy and customary laws still prevail in UMnini. The difficulty in addressing patriarchy and customary law is exacerbated by the fractious relationship between traditional leadership and government. Traditional authorities view the post-1995 democratic government as having eroded their power base. As such, the government has found any interventions or attempts to meet with traditional leaders to resolve issues of land tenure a challenge. To strengthen the position of women, a senior gender specialist from the DRDLR noted that customary laws have tried to move away from the past, in the sense that customary marriages can now be registered and recognised, and inheritance is possible, whereas in the past they were not. However, there are very silent laws, while some policies, when reading through them, do not disaggregate according to sex.

In terms of the extent to which on-going land tenure and government provisions are addressing gender-based inequalities in KwaZulu-Natal, a respondent stated that the challenge lies in factors such as culture (customary laws and traditional practices that are, in most instances, so inhumane and victimise women) when they try and implement such in rural communities. The respondent further noted that, in most cases, this depends on an individual's upbringing as well as his/ her social beliefs when it comes to gender roles and who is believed to be more or less superior in those roles. The respondent indicated the complexity of the matter, especially from the government perspective, by arguing that:

"If you come as a government official it's as if you want people to turn away from their social beliefs and culture, customs and traditions. They don't want to be associated with you or your views of 50/50 rights and also feel like you are imposing your own beliefs upon them by force and want to change their general way of living. They don't understand what context is this 50/50 you are talking about."

Officials from RWM argued that, under former President Zuma's administration, traditional leaders appeared to be on top of the agenda, in the sense that there were numerous legislations and laws concerning traditional authorities, such as the Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act, which was a framework put in place to address inequalities of the Black Administrative Act of 1951. However, this Act supports inequalities, as such structures of traditional authorities are made up of mostly men.

One of the key informants from RWM reported that government tends to give traditional leaders positions of presiding officers in traditional courts, and even powers to appoint 60% of the traditional council, with the community only given the power to elect 40% who are women. Emanating evidence tends to point to the fact that women's inequality and marginalisation is perpetuated by various structures that go beyond mere access to land. Unfortunately, these are the very structures that impact directly and indirectly on land issues that infringe on the rights of women.

6.6 Lessons learned based on best practices as well as failures of on-going and past policies and their implementation

Despite the significant improvement in land tenure reform implementation, a key informant from COGTA opined that Land Reform Programmes have made a difference in people's lives, but further work is necessary in terms of ensuring cooperation, coordination and strategies that indicate the extent to which government can support women.

The informant further recounted that for women to gain effective rights on land, it would require not only removing existing gender inequalities in law, but also ensuring that the laws are implemented. This should involve contestation and struggle at every level, the community, the household and the state on both economic and non-economic fronts. In addition, policy reforms and any other interventions must be tailored to the physical, social, and economic contexts. A gender specialist from DRDLR stated that human capacity-building should be prioritised to focus on women and gender.

A key informant from the Legal Resource Centre stated that there was nothing wrong with South Africar policies that need to be reviewed and implemented. He attributed the failure of land reform programmes and their minimal benefit on women by alluding to a host of factors summarised in Table 2.

7. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The study identified that customary land tenure systems should be revised and enforced, in order for rural women to access land. Likewise, at research level, there is a need to communicate and research various complexities that surround women's land rights. This could lead to improved rights protection and gender policy formulation specifically for women.

The study recommends that women should have equal tenure rights as well as access to land, irrespective of their marital status. Supportive legislative reforms that build on local tenure systems and practices should be put in place to protect the land rights of women. As such, there is a need to undertake awareness campaigns among rural women, in order to educate them about their rights within legal and customary systems on land.

Therefore, the need for a close working relationship between the government and the traditional leadership to eliminate land-grabbing is essential and should be strengthened. The study emphasises the notion that solving land-grabbing among vulnerable rural women calls for the following:

• There is a need for women to mobilise themselves and learn more about all pieces of legislation and make sure that their voices are heard. They need to educate themselves, and relate their personal experiences in terms of customary law and formal statutory laws. This can only happen if women mobilise themselves. Such advocacy could be done through civil society and other women's groups.

• Poor implementation of gender policies and plans, coupled with weak political will and capacity, remains a limitation to women's inclusiveness in land issues. The study argues that the government must try to implement policies that are already in existence before making any new proposals.

• There is a need to address capacity constraints, given the low number of gender specialists and the few of them that

focus on gender programmes and women empowerment as a priority area. If capacity is strengthened, gender frameworks designed to support women would be developed and implemented.

• There is a need for proper monitoring, evaluation and implementation of existing frameworks that strengthen women's rights. The study noted that working with traditional leaders in maintaining women safety, respecting women's voices and controlling land-grabbing by men and local power gatekeepers remain the only way to unlock opportunities for women.

• The study argues that, while customary laws are the main hindrance to women's control, their behaviour and response to limited access to land is also fuelled by men who are determined to control and undermine women. This is aggravated by women's "self-hurt syndrome" which, in essence, reflects their weakened capacity in their quest for rural land. Even in some instances where women are involved in decision-making, the self-hurt idea of being subjects to males kicks in and often robs them of their rights.

• To further improve respect for female human lives, there is a need for a reporting system against abuse of power and influence to be put in place for rural women. Such a reporting system should be embedded in the formal legal system to serve as a conscious check for rural chiefs and males. Similarly, there is a need for increased investment in the eroding moral values to equality in the rural space.

REFERENCES

ABDULKADIR, H. & ABDULLAHI, A. 2018. Factors influencing women access to land in Bichi local. International Journal of Information Research and Review, 5(4), pp. 5395-5398. [ Links ]

ALLEN, S. 2018. The importance of an intersectional approach to gender-based violence in South Africa. Unpublished Honours thesis. Portland, Oregon: Portland State University. DOI 10.15760/honors.531. [ Links ]

ANTWI-BEDIAKO, R. 2018. Chiefs and nexus of challenges in land deals: An insight into blame perspectives, exonerating chiefs during and after Jatropha investment in Ghana. Cogent Social Sciences, 4(1), Article 1456795. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1456795 [ Links ]

BASSETT, E.M. 2007. The persistence of the commons: Economic theory and community decision-making on land tenure in Voi, Kenya. African Studies Quarterly, 9(3), pp. 2152-2448. [ Links ]

BAYISENGE, J., HÖJER, S. & ESPLING, M. 2015. Women's land rights in the context of the land tenure reform in Rwanda - The experiences of policy implementers. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 9(1), pp. 74-90. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2014.985496 [ Links ]

BRANSON, N. 2016. Land, law and traditional leadership in South Africa. Africa Research Institute: London. (Online). Available at: <https://www.africaresearchinstitute.org/newsite/ publications/briefing-notes/land-law-and-traditional-leadership-in-south-africa/> [Accessed: 30 October 2019]. [ Links ]

BRASSELLE, A.S., GASPART, F. & PLATTEAU, J.P. 2002. Land tenure security and investment incentives: Puzzling evidence from Burkina Faso. Journal of Development Economics, 67(2), pp. 373-418. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(01)00190-0 [ Links ]

BRYCESON, D.F. 2019. Gender and generational patterns of African de-agrarianization: Evolving labour and land allocation in smallholder peasant household farming, 19802015. World Development, vol. 113, pp. 60-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.08.021 [ Links ]

BUNELLI, C., DOSS, C. & KIERAN, C. 2015. Gender and land statistics: Recent developments in FAO's Gender and Land Rights Database. FAO & IFPRI Technical Note. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization. [ Links ]

BYAMUGISHA, F.F.K. 2013. Securing Africa's land for shared prosperity: A program to scale up reforms and investments. Africa Development Forum Series. Washington, DC: Agence Française de Développement and the World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-9810-4 [ Links ]

CHIGBU, U.E. 2019. Masculinity, men and patriarchal issues aside: How do women's actions impede women's access to land? Matters arising from a peri-rural community in Nigeria. Land Use Policy, vol. 81, pp. 39-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.10.033 [ Links ]

CHIWESHE, M.K., CHAKONA, L. & HELLIKER, K. 2015. Patriarchy, women, land and livelihoods on A1 farms in Zimbabwe. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 50(6), pp. 716-731. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909614541083 [ Links ]

CLAASSENS, A. 2014. 'Communal land', property rights and traditional leadership. (Online). Available at: <https://wiser.wits.ac.za/system/flles/documents/Claassens2014.pdf> [Accessed: 30 September 2016]. [ Links ]

COUSINS, B. & HORNBY, D. 2009. Imithetho yomhlaba yaseMsinga: The land laws of Msinga and potential impacts of the Communal Land Rights Act. Church Agricultural Projects (CAP) and the Learning and Action Project (LEAP). (online). Available at: <http://www.mdukatshani.com/resources/MRDP%20LEAP%20research%20on%20gender%20and%20land.pdf> [Accessed: 1 November 2017]. [ Links ]

DALEY, E. & ENGLERT, B. 2010. Securing land rights for women. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 4(1), pp. 91-113. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531050903556675 [ Links ]

DANIELS, A. 2016. Women: A focus on land. [Online]. Available at: <http://www.bbqonline.co.za/articles/women-16735.html> [Accessed: 2 March 2017]. [ Links ]

DEERE, C.D., ALVARADO, G.E. & TWYMAN, J. 2010. Poverty, headship, and gender inequality in asset ownership in Latin America. Gender, Development and Globalization Program, Center for Gender in Global Context, Michigan State University. [ Links ]

DILLON, B. & VOENA, A. 2018. Widows' land rights and agricultural investment. Journal of Development Economics, vol. 135, pp. 449460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.08.006 [ Links ]

DLA (DEPARTMENT OF LAND AFFAIRS). 1997. White Paper on South African Land Policy. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

DLA (DEPARTMENT OF LAND AFFAIRS). 1999. Land Reform Gender Policy: A framework. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

DOSS, C., KOVARIK, C., PETERMAN, A., QUISUMBING, A.R. & VAN DEN BOLD, M. 2013. Gender inequalities in ownership and control of land in Africa: Myths versus reality. IFPRI Discussion Paper 1308. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. (Online). Available at: <http://ebrary.ifpri.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15738coll2/id/127957> [Accessed: 30 October 2019]. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2373241 [ Links ]

DRDLR (DEPARTMENT OF RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND LAND REFORM). 2011. Green Paper on Land Reform. GN 639 in GG 346-7 of 16 September 2011. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

DYER, M. 2018. Transforming communicative spaces: The rhythm of gender in meetings in rural Solomon Islands. Ecology and Society, 23(1), pp. 17-27. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09866-230117 [ Links ]

EHWI, R.J., TYLER, P. & MORRISON, N. 2018. Market-led initiatives to land tenure security in Ghana: Contribution of gated communities. Paper prepared for presentation at the 2018 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, The World Bank, Washington DC, 19-23 March. [ Links ]

EVANS, R. 2016. Gendered struggles over land: Shifting inheritance practices among the Serer in rural Senegal. Gender, Place and Culture, 23(9), pp. 1360-1375. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2016.1160872 [ Links ]

EVANS, R., MARIWAH, S. & ANTWI, K.B. 2015. Struggles over family land? Tree crops, land and labour in Ghana's Brong-Ahafo region. Geoforum, vol. 67, pp. 24-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.10.006 [ Links ]

FAO LAND TENURE SERVICE OF THE RURAL DEVELOPMENT DIVISION. 2002. Gender and access to land. FAO Land Tenure Studies 4. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization. [ Links ]

GOLDMAN, M.J., DAVIS, A. & LITTLE, J. 2016. Controlling land, they call their own: Access and women's empowerment in Northern Tanzania. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 43(4), pp. 777-797. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2015.1130701 [ Links ]

JACOBS, S. 2002. Land reform: Still a goal worth pursuing for rural women? Journal of International Development, 14(6), pp. 887-898. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.934 [ Links ]

KREJCIE, R. & MORGAN, D. 1970. Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), pp. 607-610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308 [ Links ]

LARSON, D.F., MURAOKA, R. & OTSUKA, K. 2016. Why African rural development strategies must depend on small farms. Global Food Security, vol. 10, pp. 39-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2016.07.006 [ Links ]

LASTARRÍA-CORNHIEL, S. & GARCÍA-FRÍAS, Z. 2005. Gender and land rights: Findings and lessons from country studies. In: United Nations (Ed.). Gender and natural resources management. Rome: United Nations, Food and Agriculture Organization [Online]. Available at: <http://www.fao.org/3/a0297e/a0297e08.htm#bm8> [Accessed: 30 October 2019]. [ Links ]

LAVERS, T. 2017. Land registration and gender equality in Ethiopia: How state-society relations influence the enforcement of institutional change. Journal of Agrarian Change, 17(1), pp. 188-207. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12138 [ Links ]

LINCE-DEROCHE, N., SHOCHET, T., SIBEKO, J., MDLOPANE, L., PATO, S., MAKHUBELE, Q. & BESSENAAR, T. 2018. 'You can talk about condoms [with younger men] while older men ... beat you for that': Young women's perceptions of gender-based violence within intergenerational relationships in South Africa. South African Medical Journal, 108(8), pp. 682-686. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2018.v108i8.12794 [ Links ]

MANNAT, D. 2018. Women and freedom of speech: Considering gender equality in freedom of speech. International Journal of Peace, Education and Development, 6(2), pp. 85-89. https://doi.org/10.30954/2454-9525.02.2018.6 [ Links ]

MURUGANI, V.G. 2013. Land use security within the current land property rights in rural South Africa: How women's land-based food security efforts are affected. Unpublished PhD thesis. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

MUTANGADURA, G. 2007. The incidence of land tenure insecurity in Southern Africa: Policy implications for sustainable development. Natural Resources Forum, 31(3), pp. 176-187. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-8947.2007.00148.x [ Links ]

NAJJAR, D. 2017. Women, land, and empowerment dynamics in Egypt's Mubarak resettlement scheme. [Online]. Available at: <https://repo.mel.cgiar.org/handle/20.500.11766/6143> [Accessed: 30 October 2019]. [ Links ]

NAMUBIRU-MWAURA, E. 2014. Land tenure and gender: Approaches and challenges for strengthening rural women's land rights. Washington, DC. Background paper for the World Bank Gender and Development Team. [ Links ]

PERZ, S., HOELLE, J., ROCHA, K., PASSOS, V., LEITE, F., CORTES, J., CARVALHO, L. & BARNES, G. 2017. Tenure diversity and dependent causation in the effects of regional integration on land use: Evaluating the evolutionary theory of land rights in Acre, Brazil. Journal of Land Use Science, 12(4), pp. 231-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2017.1331273 [ Links ]

PLATTEAU, J.P. 1996. The evolutionary theory of land rights as applied to sub- Saharan Africa: A critical assessment. Development and Change, 27(1), p. 29-86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.1996.tb00578.x [ Links ]

PO, J. & HICKEY, G. 2018. Local institutions and smallholder women's access to land resources in semi-arid Kenya. Land Use Policy, vol. 76, pp. 252-263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.03.055 [ Links ]

POPOOLA, A. & MAGIDIMISHA, H. 2019. Will rural areas disappear? Participatory governance and infrastructure provision in Oyo State, Nigeria. In: Tembo-Silungwe, C., Musonda, I. & Okoro, C. Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of Development and Investment -Strategies for Africa. DII-2019, 24-26 July, Livingstone, Zambia, pp.12-26. [ Links ]

RAVNBORG, H.M. & SPICHIGER, R. 2014. Pursuing gender equality in land administration. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies. [ Links ]

RAZAVI, S. 2005. Land tenure reform and gender equality. UNRISD Policy Brief, UNRISD Geneva, Switzerland. [Online]. Available at: <http://www.unrisd.org/80256B3C005BCCF9/httpNetITFramePDF?> [Accessed: 12 May 2017]. [ Links ]

RIBOT, J.C. & PELUSO, N.L. 2003. A theory of access. Rural Sociology, 68(2), pp. 153-181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.2003.tb00133.x [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 1996. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Act 108 of 1996. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

STAMM, V. 2009. Social research and development policy: Two approaches to West African land-tenure problems. Africa Spectrum, 44(2), pp. 29-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/000203970904400202 [ Links ]

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA. 2011. Quarterly Labour Force Survey: Quarter 2. (Online). Available at: <http://www.statssa.gov.za> [Accessed: 30 October 2019]. [ Links ]

STEWART, D.W., SHAMDASANI, P.N. & ROOK, D.W. 2007.Focus groups: Theory and practice. 2nd edition. London: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412991841 [ Links ]

STIFTUNG, H.B. 2009. Perspectives: Political analysis and commentary from Africa. Washington, DC: Heinrich Boll Stiftung. [ Links ]

TSCHIRHART, N., KABANGA, L. & NICHOLS, S. 2018. Equal Inheritance is not always advantageous for women: A discussion on gender, customary law, and access to land for women in rural Malawi. Gendered Perspectives on International Development: Working Paper no 310, pp. 1-16. [ Links ]

UMARU BABA, S. & VAN DER HORST, D. 2018. Intrahousehold relations and environmental entitlements of land and livestock for women in rural Kano, northern Nigeria. Environments, 5(2), paper 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments5020026. [ Links ]

UMNINI LADP (THE UMNINI LOCAL AREA DEVELOPMENT PLAN). 2006. eThekwini Municipality Area, Durban, South Africa. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS. 1996. Land administration guidelines with special reference to countries in transition. New York and Geneva: United Nations. [ Links ]

WAHAB, B., POPOOLA, A.A. & MAGIDIMISHA, H.H. 2018. Access to urban agricultural land in Ibadan, Nigeria. Planning Malaysian: Journal of the Malaysian Institute of Planners, 16(4), pp. 161-175. https://doi.org/10.21837/pmjournal.v16.i8.547 [ Links ]

WALDRON, I.R. 2018. Women on the frontlines: Grassroots movements against environmental violence in indigenous and Black communities in Canada. Kalfou, 5(2), pp. 251-268. https://doi.org/10.15367/kf.v5i2.211 [ Links ]

WEIDEMAN, M. 2004. Land reform, equity and growth in South Africa: A comparative analysis. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of the Witwatersrand: Department of Political Studies. [ Links ]

WHITEHEAD, A. & TSIKATA, D. 2003. Policy discourses on women's land rights in sub-Saharan Africa: The implications of the return to the customary. Journal of Agrarian Change, 3(1-2), pp. 67-112. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0366.00051 [ Links ]

WILY, L.A. 2011. Customary land tenure in the modern world. In: Rights and Resources (Ed.). Rights to resources in crisis: Reviewing the fate of customary tenure in Africa - Brief #1 of 5, pp. 1-14. [ Links ]

YNGSTROM, I. 2002. Women, wives and land rights in Africa: Situating gender beyond the household in the debate over land policy and changing tenure systems. Oxford Development Studies, 30(1), pp. 21-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/136008101200114886 [ Links ]

ZAKARIA, Y. 2019. Emerging trends in land market and their implications for physical planning in the WA municipality. Unpublished PhD thesis. Tamale, Ghana: University for Development Studies, Department of Governance and Development Management. [ Links ]

ZARIN, A. & BUJANG, A.A. 1994. Theory on land reform: An overview. Bulletin Ukur, 5(1), pp. 9-14. [ Links ]

Peer reviewed and revised October 2019

Published December 2019

1 Global South generally refers to countries classified by the World Bank as low or middle income that are located in Africa, Asia, Oceania, Latin America, and the Caribbean.

2 For example, at the World Bank-organised Land and Poverty Conference 2017, under the theme "Why Secure Land Rights Matter", the Bank's Senior Director for Social, Urban-Rural and Resilience Global Practice noted that "[a] ddressing land tenure issues is at the centre of building sustainable communities - countries, regions, cities, and rural communities need secure rights, clear boundaries, and accessible land services for economic growth." http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2017/03/24/why-secure-land-rights-matter.print (Accessed: 23 August 2017).

*The authors declared no conflict of interest for this title or article