Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Town and Regional Planning

On-line version ISSN 2415-0495

Print version ISSN 1012-280X

Town reg. plan. (Online) vol.75 Bloemfontein 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp75i1.4

ARTICLES

Land tenure regularisation for sustainable land use in informal urban settlements: Case study of Lalaouia and Mesguiche, Souk Ahras, Algeria

Regulering van grondbesit vir volhoubare grondgebruik in informele stedelike nedersettings: gevallestudie van lalaouia en mesguiche, Souk Ahras, Algerië

Melaoana ea tulo ea lefatshe e kgothaletsang tshebediso e tsetsitseng mafatsheng a makeishene a baipehi: thuto ea mehlala ea lalaouia and mesguiche, Souk Ahras, Algeria

Fatma Zohra HafsiI; Nadia ChabiII

IAssistant Professor), Department of Architecture, University in Guelma, Algeria, Université 8 mai 1945 - Guelma, BP 401, Guelma, 24000, Algérie. Phone: +213 668372434, e-mail: <hafsi.fatmazohra@univ-guelma.dz>

IISenior Lecturer, Urban and Architectural Heritage, Constantine University, Algeria, Université Constantine 3 Salah Boubnider 'B' 72, Ali Mendjeli Nouvelle Ville, 25000, Constantine, Algérie. Phone: +213 668372434, e-mail: <nadia.chabi@univ-constantine3.dz>

ABSTRACT

Land is a topic of increasing importance in cities in developing countries. In Algeria, the issue of land is also complex and delicate. Furthermore, problems related to land are more acute when it concerns informal (or illegal) settlements. Since 1945, a rural-urban migration movement in Souk Ahras has resulted in the emergence of informal settlements that had developed on the agricultural land situated on the outskirts of the colonial urban centre. In general, under a formal pattern of urban development, access to land titles precedes the act of building and occupation. In the case of informal settlements, the acquisition of landownership ultimately occurs, after the occupation of land, through regularisation procedures. This article focuses on the experience of land tenure regularisation carried out in two informal settlements, namely Lalaouia and Mesguiche, in the city of Souk Ahras, Algeria. The article seeks to identify elements that have contributed to the greater or lesser success of land regularisation. The main finding of this research is that the regularisation of land tenure in Lalaouia and Mesguiche reflects the general tendency of the Algerian government toward informal settlements that is based essentially on the recognition of these informal settlements. Thus, a land tenure regularisation strategy is implemented. It consists of a combination of physical upgrading programmes that have been ongoing since the mid-1970s, on the one hand, and land-titling measures supported by a set of legal texts to handle the issue of informal tenure, on the other. It is found that the regularisation of the informal settlements relies on an accurate land-information system. The approach adopted within the selected informal settlements can be assessed as positive, since it enabled a relative tenure security, the stability of residents, and the improvement of life standards. Nevertheless, these technical and legal tools are applied separately, instead of a unified approach of regularisation. Besides the fact that the regularisation process is often tedious and time consuming, the article also highlights the main challenges and obstacles that impede the regularisation process: historical complexity of land status, and lack of human, technical and financial resources. These issues are exacerbated by social conflicts that are often associated with heritage.

Keywords: informal urban settlements, land information, landownership, land-tenure regularisation, Souk Ahras

ABSTRAKTE

Grond is 'n onderwerp van toenemende belang in stede in ontwikkelende lande. In Algeria is die kwessie van grond ook ingewikkeld en delikaat. Probleme wat met grond verband hou, is skerper wat informele (of onwettige) nedersettings aanbetref. In Souk Ahras, het 'n landelik-stedelike migrasiebeweging sedert 1945 gelei tot informele nedersettings wat ontwikkel is op die landbougrond wat aan die buitewyke van die koloniale stedelike sentrum geleë is. In 'n formele patroon van stedelike ontwikkeling word grondt itels gewoonlik eers verkry, dan word grond beset. In die geval van informele nedersettings, vind die verkryging van grondbesit eers plaas, na die besetting van grond deur middel van reëlingsprosedures. Hierdie artikel fokus op die ervaring van grondregtelike regulering wat uitgevoer is in Lalaouia en Mesguiche, twee informele nedersettings in die stad Souk Ahras, Algerië. Die artikel probeer om elemente te identifiseer wat bygedra het tot die groter of mindere sukses van grondregulering. Die belangrikste bevinding van hierdie navorsing is dat die reëlmatisering van grondbesit in Lalaouia en Mesguiche die algemene neiging van die Algerynse regering na informele nedersettings weerspieël, wat in wese gebaseer is op die erkenning van hierdie informele nedersettings. 'n Reëlingsstrategie vir grondonteiening word dus geïmple-menteer. Dit bestaan uit 'n kombinasie van fisiese opgraderingsprogramme wat sedert middel 1970 aan die gang is, asook maatstawwe vir grondtitels wat ondersteun word deur 'n stel wetlike tekste om die kwessie van informele verblyfreg te hanteer. Daar is ook bevind dat die regulering van die informele nedersettings op 'n akkurate landinligtingstelsel staatmaak. Die benadering wat binne die ge-selekteerde informele nedersettings gebruik word, kan as positief beoordeel word, aangesien dit 'n relatiewe verblyfreg, die stabiliteit van inwoners en die verbetering van lewensstandaard moontlik gemaak het. Hierdie tegniese en wetlike instrumente word afsonderlik toegepas, in plaas daarvan om 'n verenigde benadering tot reëlmatigheid te volg. Die artikel het, benewens die feit dat die reguleringsproses dikwels langdurig en tydrowend is, ook die belangrikste uitdagings en struikelblokke uitgelig wat die reëlingsproses belemmer: historiese kompleksiteit van landstatus, en gebrek aan menslike, tegniese en finansiële hulpbronne. Hierdie probleme word ook vererger deur sosiale konflikte wat dikwels met erfenis verband hou.

Sleutelwoorde: Grondbesit, grondbesit-reëlmatigheid, grondinligting, informele stedelike nedersettings, Souk Ahras

TUMELO

Lipuisano ka lefatshe li tsoela pele ho nka maemo linaheng tseo eleng hona li tsoelangpele. Ka mokhoa o tsoanang, lefatshe ke taba ea bohlokoa, e bileng e leng thata naheng ea Algeria. Mathata a lefatshe a tshoenya ka ho fetisisa metseng e sa reroang eleng ea baipehi. Toropong ea Souk Ahras, metse ea baipehi e bakiloe ke ho falla hoa batho ho tloha mahaeng ho ea litoropong. Phallo ena e qalile selemong sa 1945 'me e ntse e tsoela pele le joale. Metse ena e ahiloe masimong a potapotileng litoropo tse thehiloeng mehleng ea bokolone. Ka tloaelo ea thero ea lefatshe, baahi ba fumana mangolo a litsha pele ba ka aha le ho lula lefatsheng; empa nthleng ea metse ea baipehi, methati ena ha e lateloe. Sengoliloeng sena se lekola methati e latetsoeng moralong oa ho tlisa ntlafatso e molaong metseng ea baipehi ea "Lalaouia" le "Mesguiche" toropong ea Souk Ahras, naheng ea Algeria. Linthla tse lekoloang li kenyeletsa mabaka a susumelitseng katleho ea moralo ona. Nthla kemo ke hore mekhoa le methati e latetsoeng moralong oa Lalaouia le Mesguiche, ke setshoantsho sa methati e lateloang naheng ea Algeria ka kakaretso. Moralo ona o kenyelelitse ntlafatso ea metse ea baipehi e qalileng ka 1970, mmoho le ho etsa mangolo a molaong a litsha. Ho feta moo, sengoliloeng se bontsha hore katleho ea meralo e tjena e holima puisano e bulehileng ea bohle ba amehang, mme bohle ba lokela ho fumana lintha tsohle ka nako tsohle. Ka kakaretso, ntlafatso ea metse ena e mmeli e atlehile, kaha baahi ba fumane mangolo a litsha, mme maphelo a bona a ntlafetse. Le ha hole joalo, mekhoa le methati ea ntlafatso ha e sebelisoe ka nako ele nngoe, mme sena se baka mathata a kenyelelitseng ka hara sengoliloeng sena; mohlala ke maemo a hlobaetsang a lefatshe a tlisitsoeng ke liketsahalo tsa histori, thlokahalo ea litsebo le chelete ho tlisa ntlafatso, 'moho le likhang tse tlisoang ke bojalefa ba lefatshe.

1. INTRODUCTION

Informal settlements are common phenomena in cities in developing countries. In Algerian cities, several factors such as the massive migration of rural residents to urban centres, rapid demographic growth, and the incapacity of public authorities to propose affordable and decent housing have led to the emergence and growth of informal urban settlements. In 1976, the public supply of housing was 29%, which seems relatively low. The Algerian government was not able to provide urban dwellers with sufficient housing or land on which to build. Hence, to cope with the insufficient supply of public housing, urban residents had to rely on their own resources and competences to build their houses. Nonetheless, roughly 80% of self-built housing was illegal (Lalonde, 2010: 115). Illegality of urban settlements covers multiple aspects. It refers to either the non-compliance with building standards or the lack of land titles. It presents a number of challenges to the urban land management process for authorities, on the one hand, and does not provide sufficient tenure security to residents of informal settlements, on the other.

In fact, one of the main challenges in informal settlements is land ownership. Research on topics related to land in informal urban settlements has preoccupied scholars and international organisations for over four decades. They draw attention to the importance of land tenure regularisation in informal settlements. De Soto (1989) notes that property rights are important in promoting development and prosperity, and highlights the idea of the need for the regulation of informality. The author emphasises the socio-economic benefits that could be derived from increasing security of tenure. In addition, land tenure security can lead to greater investment in individual property and neighbourhoods, as well as increase revenue from property taxation (Woodruff, 2001: 1218).

In this sense, recent recommendations by international organisations focus on the idea of regularising the situation of precarious neighbourhoods. Thus, a preparatory policy document for the New Urban Agenda of Habitat III claiming a "resilient, prosperous and inclusive city" advocates moving towards "recognition, equal treatment and specific consideration for vulnerable groups" (UN-Habitat, 2016: online). Instead of demolition, rehabilitation and land tenure security would promote the integration of informal settlements within the city.

However, access to landownership in informal areas is complex and faces several tensions and conflicts. Many approaches to regularisation in developing countries have been developed with varying degrees of success. Experiences show that the large diversity of tenure systems and the large patterns of informal urban settlements have initiated variable responses from policymakers. In this context, a review of international experiences shows that there is a general tendency for positive policies that support regularisation in informal settlements, instead of tough approaches such as eviction or involuntary resettlement (UN-Habitat, 2003a: 128-132). On the other hand, these experiences reveal that successful examples of managing urban informal settlements are those that combine regularisation and improvement of the urban environment in these urban areas. Authorities must And solutions for both the regularisation of land tenure and the upgrading of urban environments in informal settlements.

Using a case study approach, this article is concerned with the issue of land tenure regularisation in informal settlements that have undergone the regularisation process. It examines the specific conditions of urban informality of Lalouia and Mesguiche, and identifies the process, tools and legal measures that have been implemented in these informal settlements of Souk Ahras city, in order to address the problems of informal land tenure.

2. LAND TENURE REGULARISATION IN INFORMAL URBAN SETTLEMENTS

In order to understand informality in urban settlements, it is important to introduce the current theory on informality concepts included in this article. A literature review explores the existing theory and approaches of land tenure regularisation in informal urban settlements.

2.1 Informal settlements

The phenomenon of informal settlements is a common feature of many cities in the world, especially in developing countries. There are various labels for these settlements, namely irregular, spontaneous, unplanned, unauthorised, and so on, but all overlap. Several terms are used to describe the diversity of local situations. The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) (2009: 25) characterises informal settlements as "illegal residential formations, either urban or peri-urban, which lack basic infrastructure, security of tenure, adequate housing and basic services". On the other hand, Chaline (1990: 128-129) uses this term to designate spontaneous peripheral districts. However, informal settlements are not exclusively peripheral. Typically, informality is related to a set of characteristics such as illegal occupation of private or public land, followed by self-construction (Srinivas, 2005); illegal condition of land subdivision into individual plots, or construction of houses without building permit (UNECE, 2009: 14). In short, one key attribute of informality is the violation of the prevailing legal rules. Historically, the concept of "informal" appeared in 1972 to characterise the marginality, insalubrity and precariousness of urban settlements. For purposes of this article, the concept 'informal settlement' refers, more specifically, to a form of housing where land status is precarious, while the constructions are hard and in good condition, breaking with any form of insalubrity. Therefore, informality is related to the initial occupation of land, which occurs without the permission of the legal owner or by means of illegal transactions. In many countries, tenure informality is a key characteristic in informal settlements (Durand-Lasserve & Selod, 2007: 3).

2.2 Land tenure

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO, 2002: 7), land tenure can be defined as "the relationship, whether legally or customarily defined, among people, as individuals or groups, with respect to land". Land tenure refers to the rights individuals and communities have regarding land (Durand-Lasserve & Selod, 2007: 4). Furthermore, Moser (1998) states that land tenure is not only the support of housing, but also the guarantee for a location that determine the access to economic opportunities. In addition, land tenure is introduced as the complex set of rules that governs land use and landownership (Payne & Durand-Lasserve, 2012: 2). These rules may have their origin in state, customary or religious law, or more often in a combination of these. Land tenure systems can be classified according to whether they are based on formal or informal rights. Formal property rights may be regarded as those that are explicitly acknowledged by the state and that may be protected using legal means, whereas rights are those that lack official recognition and protection (FAO, 2002: 11). These rights comprise the rights to occupy, use, develop, inherit, and transfer land.

Access to secure land and shelter is a precondition for gaining access to other urban opportunities. In this context, The United Nations Human Settlements Programme defines security of tenure as protection against eviction, the possibility of selling and transferring rights through inheritance, the possibility of having a mortgage, and access to credit under certain conditions (UN-Habitat, 2003b: 7). In fact, for their well-being, people in urban areas require a secure place to live, a healthy environment, and to be within reach of work opportunities and essential services. Therefore, a person or a household can be said to have secure tenure when they are protected from eviction by means of known and agreed legal means (UN-Habitat, 2011: 5). It is widely accepted that access to a secure tenure is a key factor for securing basic living conditions. Informal tenure has many negative consequences on urban development, because it worsens access to shelter and security of tenure (Lopez-Moreno, 2003). Thus, ensuring security of land tenure through regularisation procedures can have obvious benefits in terms of enhanced investment incentives, improvement of equity, and reduction of conflicts related to land, especially in urban areas in developing countries (Durand-Lasserve & Selod, 2007: 3).

Lack of secure tenure has a negative impact on the built environment and has often been introduced as the source of inadequate investment in housing and urban development. The argument behind this is that property owners are more likely to invest in their own homes and neighbourhoods once tenure is secure (UN-Habitat, 2001: 85).

There is a consensus that the absence of legal documents (land titles, permits or authorisations to occupy or develop), systems for the registration of deeds or rights, and land information systems (for example, a cadaster or land register) contribute to increased land insecurity for urban dwellers. Subsequently, land tenure regularisation can be regarded as a means of securing tenure, since it permits the legal recognition of "informal" tenure. Therefore, the State plays a major role in facilitating the regulation of the responsibility of rights holders. The land tenure regularisation process requires legal, administrative and technical tools. The regularisation of informal settlements combines the process of legalisation of tenure through titling and the upgrading of public services and job opportunities (Fernandes, 2011: 26). This may be concretised by means of policies, laws and programmes.

Many studies are aimed at understanding the links between land tenure and sustainable use of land (UN-Habitat, 2008; Olale, 2013; Jones, 2017). They survey the global experience in the implementation of land-use policies that move towards sustainable development. In this context, these studies note that private property right regimes are likely to create incentives for the management of resources. On the other hand, the guarantee of rights of different property owners and different forms of landownership is a critical component of sustainable environmental management, since the informal urban settlements are a kind of human activity that contributes to environmental consequences and the erosion of land (meant, in this instance, as a non-renewable resource). Informal urban settlements are also regarded as a type of land use that must correspond to the purposes of sustainable urban development. Hence, the holder of any rights in land has a role to play in the management of environmental resources. According to these studies, controlling and securing land tenure in informal settlements enables residents to invest considerable amounts of savings and improve their living environment.

3. STUDY AREA

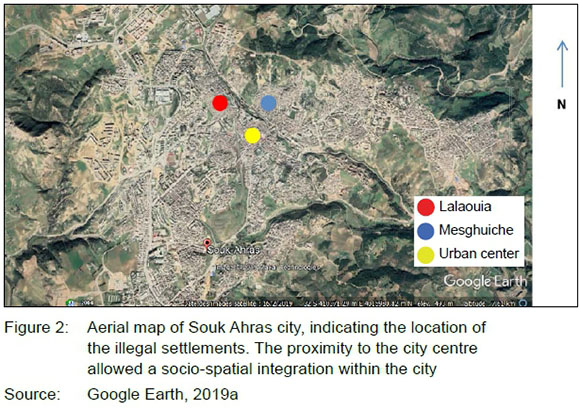

Like all Algerian cities, Souk Ahras, a middle-sized city in north-western Algeria, faces the problems of informal tenure in illegal settlements. Three informal settlements marked the urban development of the city: Lalaoui, Mesguishe and the kilometric point 108 (P.K. 108). The most important settlements in terms of size and population are Lalaouia and Mesguiche, which have undergone the regularisation process started since the 1970s. These informal settlements are home to a large proportion of urban population. Indeed, according to the last population census of 2015, these two urban settlements are hosting a population of 23 010 people (14 504 people in Lalouia and 8 506 people in Mesguiche), or approximately 13% of the population of Souk Ahras. Therefore, relocation of the residents is impossible in terms of the insufficient financial resources of the city. These factors make land tenure regularisation important and inevitable.

To better understand the nature of informal housing development in contemporary urbanisation, it is necessary to examine the history of these settlements. In Souk Ahras, the phenomenon of informal urban growth began in 1945 and continued until 1972 (Figure 1), as a result of population growth and the flow of migrants from the countryside. Post-independence, after the departure of European settlers, a large number of housing units became vacant and were then occupied by local residents. However, the colonial urban centre with its three suburbs (Faubourg Saint-Charles, Faubourg de la Gare, and Faubourg Constanville) was totally saturated and could no longer meet the need for housing. Consequently, the inability to grapple with the complexity of urbanisation was visibly reflected in the growth of informal settlements. The informal sector of housing was thus a response to insufficient social housing, giving rise to many informal urban districts: Lalaouia, Mesguiche, PK 108, and so on. Typically, informal settlements are regarded as worlds apart, as they represent the negative pole of the city (Valery, 2013: 14). This point of view matches the reality of the two informal urban settlements. Lalaouia, for instance, faces urban and social problems, and experiences a high average of crimes and drug traffic (Elkhabar, 2019: online).

4. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This study analyses land tenure regularisation in Lalouia and Mesguiche, two informal urban settlements of Souk Ahras. The analysis is based on the assumption that regularisation of land tenure contributes to tenure security and grants a sustainable use in informal settlements. A mixed methods research approach, including qualitative and quantitative research methods, was used to obtain data from secondary and primary data sources. Primary data were collected by field-specific on-site observation, which helped observe problems related to land tenure regularisation and describe the study area. Making use of case study research (Yin, 2014), the main objectives of the study are to understand the reasons for the informality in the two urban settlements; to review the technical and legal responses of public authorities at both national and local level, and to assess the progress and efficiency of land tenure regularisation in the selected informal settlements.

4.1 Data collection

Interviews were used as the main method of data collection for the case study. During June 2019, the authors visited the informal settlements for on-site observation, in order to obtain information about the spatial and morphological characteristics of the informal settlements, the quality of the urban environment (liveability), and the investments by residents to improve the built environment.

To understand the challenges of land tenure regularisation, interviews were conducted within institutional bodies, including communal popular assembly Department of Urbanism and Construction (urban development engineer); land registry (interviews with land registry officials); cadaster department (interviews with the director, topographer), and a specialised land expert. The interview schedule included six open-ended questions on the procedure of land tenure regularisation: how the physical upgrading works; the obstacles that impede the land tenure regularisation process; the legal support of the land tenure regularisation process; specific question to the cadaster's director about the procedure of land surveying and its legal support, and specific question to the land expert about the original land use, tenure systems, and circumstances for the emergence of informality.

Over two weeks (from 2 to 17 June), interviews were conducted with 30 residents. The interviewees were mainly selected according to their attitude towards land tenure regularisation. The interviewees were divided between those who had regularised their landownership (10 residents); those who had submitted a regularisation request (10 residents), and those who did not want to regularise their landownership (10 residents). The interview schedule included Ave open-ended questions on the year of construction and occupation of houses and the nature of relationships that link occupants; the seller (from whom they bought the land); the first time they benefited from public services (for example, electricity, water, and so on); motivation/ demotivation for land tenure regularisation, and information about the problems they face with land tenure regularisation procedures.

Secondary data consisted of books, journals, newspaper articles, maps/plans and Internet searches, including documents of land transactions, reports of land registry on informal settlements explaining the dynamics of informal/ formal land transactions, and documents related to urban planning (masterplan of Souk Ahras).

5. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

5.1 Urban form of the informality

The informal settlements of Lalouia and Mesguiche are close to the city centre and are, to a large extent, well integrated into the urban fabric of the city. Figure 2 illustrates the proximity of the informal settlements to the urban centre. In terms of urban morphology, these urban fabrics can easily be distinguished within the layout of the city. The urban form of these districts contrasts largely with that of the colonial centre. Obviously, the layout of the city displays two types of urban fabric: the colonial orthogonal grid and the irregular urban fabric of the informal districts (Figure 3).

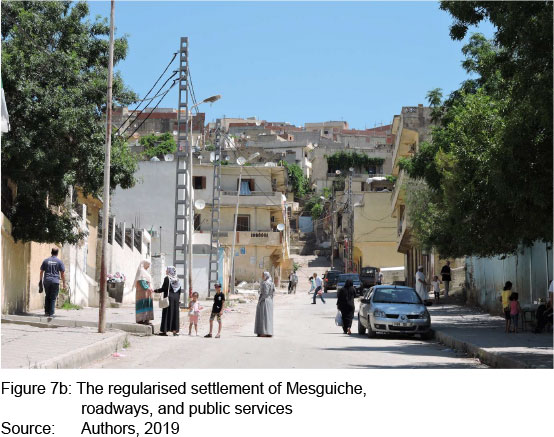

The informal settlements are relatively large and occupy an area of approximately 70 hectares. The area is predominantly residential with a mix of some local shops located in the basement of houses. There are a few community and public facilities such as primary schools, mosques, post offices, and so on. The urban form of the two informal settlements is the result of a generative process of self-organisation and incremental adaptations. They are formed by low-rise adjacent houses. The building height ranges from one to two levels (Figure 4), and narrows streets (Figures 5a and 5b).

5.2 Origin, land tenure and reasons for informality

Before analysing land tenure regularisation in informal settlements, it is important, first, to understand the original land use, land tenure systems and the reasons for informality. In this context, Clerc (2010: 64-65) states that the development of urban informal settlements is largely related to land history.

In the colonial era, the land on which the two settlements have been developed was irrigated agricultural land, divided into large parcels with different activities (Figure 6). Land was the private property of European settlers. It was sold to the Souk Ahrassian people. The private property was thus transferred legally from the European to the indigenous people. The original land use changed from agricultural to urban. For example, in 1924, agricultural land of over 40 hectares was sold to "Rehamna abdelmadjid", an original resident of the city, making him the most important landowner. This land would later serve as a base for the development of the informal settlement Mesguiche. An investigation into the various kinds of landownership in Lalouia and Mesguiche revealed that there are lands strictly held by collective ownership, a kind of private ownership. Nonetheless, the private property in the informal settlements is not a unique kind of land tenure (Figure 7). In fact, parts of the land are public property. As a consequence of the application of the sovereignty enshrined by the Algerian Constitution, the municipalit took possession of vacant or unregistered land. In other words, land that is undocumented property will systematically be integrated into the communal land reserves. Nevertheless, this strategy gave rise to disputes, because the landowners might justify their legal possession of the land (Figure 6).

After the legal acquisition of land, landowners started to sell parts of the land under legal tenure. From 1945 to 1971, access to land was legal and the transaction was legally registered. Thus, residents held legal title deeds. The suspension of all land transactions was introduced in 1971: a turning point in the process of development of the two districts. The promulgation in 1971 of Ordinance no. 70-91 of 15/12/1970 on the nationalisation of the notarial profession integrated the notary to the Ministry of Justice, after being a liberal activity (Algerian Republic, 1970: 1238). In doing so, the Algerian State intended to have close and continuous state control over land and could benefit from fiscal revenues from private property. This new trend matches the general policy of the State, which converged towards socialism, and which was characterised by the adoption of the principles of economy based on the ownership by the State of the means of production, which promotes and privileges collective and public ownership over private ownership. Practically, the Algerian State was, in a way, the instigator of an informal land market. Land seekers minimised dealings with the government, relying on personal relations and guarantees, which are both less expensive and more convenient. Landowners proceeded with the illegal subdivision of land, then sold it without any approval from the authorities. Land was resold, informally and illegally, often two, three, or four times, before the start of any construction. Landowners held land with informal arrangements. Land rights are not recognised in the public land registry; they are made in the form of a private deed (act sous seing privé).1The modification of the notary profession had indirect consequences on illegal access to private property. In this specific condition of land acquisition, it is possible to point out some kind of formality within informality, since landowners have documents justifying their transactions. It has been common for many years to discuss land tenure and property rights in terms of some form of legal/illegal duality. However, land tenure in Lalaouia and Mesguiche shows gradations of legality.

5.3 Land tenure regularisation in Lalaouia and Mesguiche

Policies to manage urban informal settlements are a response to social, political and land-related challenges. The manner in which governments deal with informal urbanisation is related to the history of relationships between state and society (Semmoud, 2015). In the case of illegal urban settlements, two solutions are considered, namely cancellation or recognition of illegal housing. In general, interventions by public authorities in the informal settlements of Lalaouia and Mesguiche reflect a tolerant attitude towards these informal settlements. This attitude could be explained by the fact that local authorities were not in a position to envisage their removal. Therefore, an implicit recognition of the phenomenon. In fact, local authorities in the informal settlements of Lalouia and Mesguiche adopted an approach that combines physical upgrading and land titling.

5.3.1 Upgrading the existing informal settlements

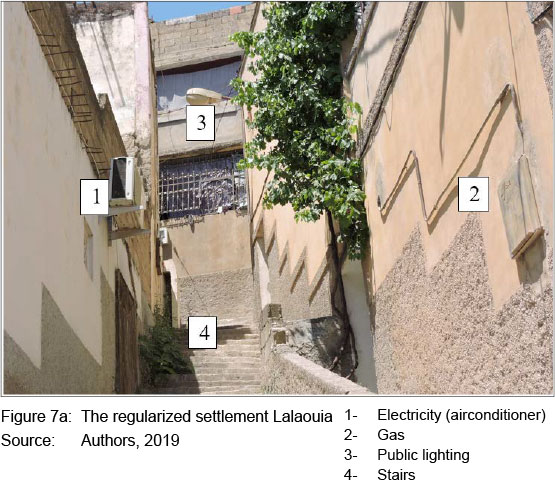

Physical upgrading represents a step towards enhancing land tenure security to informal settlement dwellers. Local authorities of Souk Ahras city preferred to upgrade the existing settlement rather than going through the costly process of destroying and rebuilding them elsewhere. The informal settlements benefited from incremental upgrading through micro-scale designed interventions. Since the mid-1970s, Lalaouia and Meguiche districts have been recognised and integrated into the communal management. In order to improve the living conditions of these informal settlements, the commune of Souk Ahras proceeded with the physical upgrading by extending the necessary infrastructure such as water, pipelines, electricity, gas, telephone, and street widening, and by setting up public facilities such as schools, medical centres, post offices, and police stations (Figures 7a and 7b). The improvement of the physical environment involved, in many cases, partial destruction of houses. Consequently, this upgrading programme granted a certain de facto recognition of these settlements and enabled security of tenure. This recognition was the first path to land regularisation.

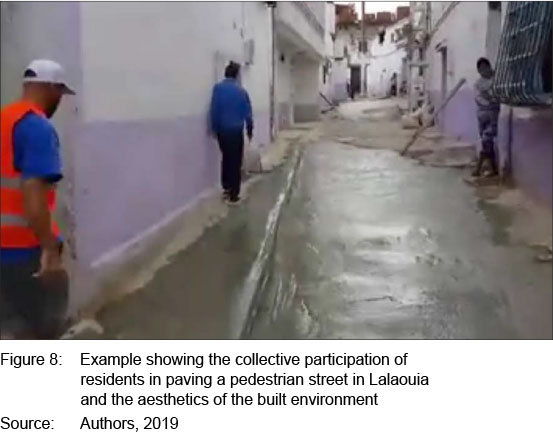

Furthermore, upgrading the informal settlement is an ongoing process that is not restricted only to local public institutions and may be initiated by residents. Indeed, the residents of informal settlements assume, on their own in some cases, the improvement of living conditions (Figure 8). In fact, the example of Lalaouia shows how residents are collectively and voluntarily involved in the process of transforming and improving their immediate surroundings and living conditions in situ.

5.3.2 Land tenure regularisation in informal districts through land titling: A legal approach

As Kironde (2006) points out, the most recent challenge facing the management of land in urban areas is land tenure. A key aspect of informality in Lalouia and Mesguiche is the lack of formal titles. This section investigates the legal texts that have been used to regulate the land-tenure system in the two selected informal settlements of the city of Souk Ahras. The regularisation of land rights in informal urban settlements complements the provision of infrastructure. It contributes to residential stability and encourages residents to securely invest in their properties.

In Algeria, only public authorities are responsible for enabling access to land, managing transactions, and handling development control, information management and land-dispute resolution. With the aim of legalising the existing informal housing stock, the Algerian government implemented different policies and laws, targeting both private and communal lands, in order to mediate land conflicts related to landownership. Within the legal framework, the most relevant laws and regulations for this study are those that define the conditions and general procedures that impact on informal housing regularisation.

i. Law no. 81-01 of 7 February 1981 on transfer of state property

This legal text introduced new measures of land acquisition and could benefit the regularisation of informal urban settlements. In 1981, due to the decline in revenues from hydrocarbon exports, the Algerian State, for lack of financial resources, could not cope with the housing needs of the population. As a result, it withdrew from the sector of real estate, freeing up both the land market and real-estate development. In the commune of Souk Ahras, the land was sold to residents whose houses are built on communal land. The price per square meter is defined by set parameters that include the location of the land within the urban perimeter and the age of occupation (Algerian Republic, 1981: 82).

ii. Ordinance no. 85-01 of 13 August 1985

Ordinance no. 85-01 defines the rules of land regularisation in the case of the absence of landowners. Art. 14 of this Ordinance stipulates that the commune replace the absentee landowner. In the same vein as this Ordinance, Decree No. 85-212 of 13 August 1985 determines the conditions under which the effective occupants of public or private land, which is the subject of acts and/or construction not in accordance with the current rules, may be regularised in their rights of disposal and habitation. In the informal urban settlements of Lalaouia and Mesguhiche, this regularisation caused conflicts between the commune and the heirs of the landowners. Available information indicates the titling of 908 properties in illegal settlements (Department of Land Registry of Souk Ahras, 2019: 1-2) (not specifically situated in the case study area) (Algerian Republic, 1985: 768).

iii. Land Inquiry Act, No. 0702 of 27 February 2007

An alternative measure for obtaining authentic instruments for owners without land titles is possible. In fact, known as the Land Inquiry Act, No. 0702 of 27 February 2007, it deals with the inadequacy in managing and administering land tenure such as lack of cadastral mapping, inexact titles, and inaccurate land information. This legal text revises an earlier text from 1983. It aims to provide access to land property through the acquisitive prescription. It constitutes a faster access route to property registration than the general land registry. The investigation is conducted after the request of the interested parties who must justify continuous possession for at least fifteen years (which makes them eligible for ownership). This procedure can provide a licence of possession. This form of investigation is, therefore, distinct from the general cadaster and registration in the land register. Nevertheless, it must be noted that this procedure for establishing the right of landownership needs the mobilisation of human, material and financial resources (Algerian Republic, 2007: 1027).

iv. Law 08-15 of 20 July 2008 art. 40

Law 08/15 deals with land tenure regularisation in the informal settlements. It has two aspects, namely technical and legal and it is applicable to four categories of completed or unfinished constructions. Only the constructions started and/ or completed under construction before the date of the promulgation of the 08/15 law are concerned n with the dispositions of this law. It introduces new parameters and tools to advance the regularisation of urban informal settlements (Algerian Republic, 2008: 16).

As shown in Figure 9, the important number of regularisation requests indicates that residents are interested in regularising their properties. Nonetheless, only 33.5% of these properties were formalised. This situation is related to the impact of institutional problems that face the regularisation procedure in informal settlements. In order to ensure a successful implementation of land tenure regularisation in informal settlements, the Algerian State established the necessary institutions. These institutions experience a huge lack of human, technical and financial resources. As a consequence, the regularisation procedure takes a long time to be accomplished.

By formulating several text laws over time, the Algerian Government attempted to solve problems related to the complexity of situations: unknown landowners, lack of legal documents proving landownership but effective occupation, conflicting property ownership, and so on. It is noted that the degree of complexity of land tenure regularisation in the case of the two informal settlements of Lalaouia and Mesguiche depends largely on whether the informal buildings are built on private or communal land. Traditionally, regularisation procedures of properties situated on private land appear to be more complex, as they cause disputes among different stockholders (Amamaria, 2019b: personal interview).

Land tenure regularisation in Lalaoui and Mesguiche has allowed relative tenure security. Indeed, owners of legalised properties securely make considerable investments in upgrading their housing (some houses are 3 or 4 stories high). Thus, a series of alterations affects the built environment by generating a process of urban densification.

5.4 The importance of the cadaster in the regularisation process

The control of landownership problems cannot be efficient without a committed and determined cadastral policy that advances the regularisation process (CNES, 2004). Lessons learnt from global experiences show that the process of regularisation relies on the availability of reliable land information.

The cadaster in Algeria was instituted by Ordinance 75-74 of 1975 on the establishment of the General Cadaster and the institution of the Land Register. In practice, the mission of the cadaster is to elaborate cadastral layouts (art. 8) and provide accurate physical data about land properties in informal settlements (Algerian Republic, 1975: 994). It constitutes a way of land regularisation, as it delivers land registers to landowners. These land registers have the value of property deeds and allow their holders to dispose of, and freely enjoy their properties. Through this process, 49% of urban land and 100% of rural land of Souk Ahras have been cadastered (Cadaster Department of Souk Ahras, 2019a: online). The cadastral maps of the two informal districts of Lalaouia and Mesguiche show the plot boundaries and the land properties. These cadastral maps are the support of the registration of parcels (Figures 10 and 11).

5.5 Results of land tenure regularisation in Lalouia and Mesguiche: Success and failure

It is widely admitted that land tenure regularisation is associated with a number of socio-economic, financial, and urban-environmental sustainability factors through physical upgrading and the issue of legal land titles. However, while analysing the experience of two informal settlements, a number of obstacles slowing down the regularisation process can be identified. First, the special urban form of these informal settlements makes the physical upgrading hardly possible: narrow streets, steep slopes, culs-de-sac, and so on. Despite the realisation of some basic urban services, their capacities do not befit the local population. Furthermore, upgrading in the informal settlements entails a series of incremental micro-scale designed works, instead of a global well-designed project.

Secondly, legal titling is a subject of legal and judicial disputes. The case study reveals a diversity of existing situations that depend on a particular social context. On the one hand, the procedure of regularisation can be found to be expensive, especially for low-income residents. In fact, according to the 08/15 law, the building works and the external aspect of the house must be finished and are preconditions for the completion of the land tenure regularisation procedure. In addition, the procedure of regularisation involves the payment of several fees and charges to public and private institutions. Thus, the residents are not motivated and do not perceive the urgency of the application of a request for regularisation. Residents of informal districts may not proceed with the regularisation because of the complexity of the registration procedures. Indeed, the bureaucratic requirements of the property registration system are cumbersome and complex. The low titling rate is due to the fact that occupants have to work through a complex bureaucracy on their own, in order to complete the regularisation process.

Furthermore, it has been found that many residents may not seek landownership in order to still be eligible for public programmes of social housing. They expressly refuse to regularise their properties, in their attempt for a better life in new districts. Interfamilial conflicts have, in particular cases, hindered the regularisation procedures. The issue of joint possession of private land is often a source of tension within the family. Effectively, a house in Lalalouia or Mesguiche is often shared by numerous heirs. While regularisation procedures cannot be done without procuration to one of the heirs, they may not aim to regularise their property because of mistrust among heirs who fear losing their ownerships. For these reasons, the land is still in a process of instability.

6. CONCLUSION

This study aimed to discuss the issue of land tenure regularisation in informal urban settlements within an Algerian city. Informal urbanisation has always marked the Algerian cities. According to the nature of land tenure, the life of the two urban settlements of Lalaouia and Mesguiche can be divided into two main periods: legal land tenure from 1945 to 1971, and informal since then. The modification of the notary profession resulted in an informal land market and a large amount of illegal land transaction.

Findings show that the Algerian government adopted a positive attitude towards consolidated informal settlements. The recognition of informal urban settlements developed an approach that reflects a constant search for improving the living conditions and the stabilisation of residents in these areas, as well as a better integration of these settlements in the urban management of the city. The case study found that public intervention undertaken to regularise informal land tenure in the informal settlements is a mix of technical and legal measures. Consequently, the experience of land tenure regularisation in the case of Lalaouia and Mesguiche allowed effective land tenure security. The most visible manifestation of its relative success is the residents' involvement in upgrading the urban environment. Nevertheless, several factors inhibit land tenure regularisation. Many problems arise when a regularisation procedure is engaged: historical complexity of land status, social conflicts associated with inheritance, as well as lack of human, technical and financial resources. In order to be more efficient, approaches for regularising land tenure informality must be based on social participation, local empowerment and organisation of voluntary works. These elements are found to be important in sustaining the regularisation of informal settlements. Finally, urban informality needs to be prevented and treated from its origin, by the provision of sufficient number of public housing supply, especially for poor people.

REFERENCES

ALGERIAN REPUBLIC. 1970. Ordinance no. 70-91 on the nationalization of the notarial profession. Official journal No. 107. [ Links ]

ALGERIAN REPUBLIC. 1975. Ordinance 75-74 on establishment of the General Cadaster and institution of the Land Register. Official journal No. 92. [ Links ]

ALGERIAN REPUBLIC. 1981. Law no. 81-01 on transfer of state property. Official journal No. 6. [ Links ]

ALGERIAN REPUBLIC. 1985. Ordinance no. 85-01. Official journal No. 34. [ Links ]

ALGERIAN REPUBLIC. 2007. Land Inquiry Act, No. 07-02. Official journal No. 15. [ Links ]

ALGERIAN REPUBLIC. 2008. Law 08-15, art 40. Official journal No. 44. [ Links ]

AMAMARIA, L. 2019a. Land expert. Map of Mesguiche: Agricultural land. Map derived from French archives (1879). [ Links ]

AMAMARIA L. 2019b. Land expert. Personal interview at personal office. Souk Ahras, 20 June 2019. [ Links ]

CADASTER DEPARTMENT OF SOUK AHRAS. 2019a. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.an-cadastre.dz/DCW%20SOUK%20AHRAS/SoukAhras.htm> [Accessed: 20 June 2019]. [ Links ]

CADASTER DEPARTMENT OF SOUK AHRAS. 2019b. Cadastral map of Souk Ahras urban area (graphic document). [ Links ]

CHALINE, C. 1990. Les villes du monde arabe. In: Marre A. (Ed.). Travaux de i'institut Géographique de Reims, no. 79-80, 1990. 20 ans de TIGR, 20 ans de géographie. Paris: Masson, pp. 128129. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.persee.fr/doc/tigr_0048-7163_1990_ num_79_1_1271_t1_0128_0000_3> [Accessed: 13 October 2019]. [ Links ]

CLERC, V. 2010. Du formel â l'informel dans la fabrique de la ville. Politiques foncières et marches immobiliers â Phnom Penh. Espaces et Sociétés, 143(3), pp. 63-79. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3917/esp.143.0063 [ Links ]

CNES (NATIONAL ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL). 2004. Report on the configuration of land in Algeria. A constraint for economic development. [Online]. Available at: <http://www.cnes.dz/cnes/wp-content/uploads/Rapport-sur-la-configuration-du-foncier-en.pdf> [Accessed: 13 October 2019]. [ Links ]

DE SOTO, H. 1989. The other path: The invisibie revoiution in the third world. New York: Harper & Row Publishers. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF LAND REGISTRY OF SOUK AHRAS. 2019. Report on the advancement of land tenure regularisation processes. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF URBANISM AND CONSTRUCTION. 2008. Graphicdocuments related to the Director Plan of Development and Urban Planning (PDAU). Souk Ahras. [ Links ]

DURAND-LASSERVE, A. & SELOD, H. 2007. "The formalisation of urban land tenure in developing countries". Contribution presented to the World Bank Urban Research Symposium, 14-16 May, Washington, DC. [Online]. Available at: <http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTURBANDEVELOPMENT/Resourc-es/336387-1269364687916/6892589-1269394475210/durand_lasserve.pdf> [Accessed: 13 October 2019]. [ Links ]

ELKHABAR. 2019. The neighborhoods are drowning in crime and drugs in Souk Ahras. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.elkhabar.com/press/article/112524/> [Accessed: 24 June 2019]. [ Links ]

FAO (FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION). 2002. Land tenure and rural development. FAO land tenure studies. Rome: FAO. [Online]. Available at: <http://www.fao.org/3/a-y4307e.pdf> [Accessed: 13 October 2019]. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, E. 2011. Regularisation of informal settlements in Latin America. Policy Focus Report. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. [ Links ]

GOOGLE EARTH, 2019a. Aerial map of Souk Ahras city indicating the location of the illegal settlements. [Online]. Available at: <https://satellites.pro/Souk_Ahras_map> [Accessed: 13 October 2019]. [ Links ]

GOOGLE EARTH, 2019b. Aerial map of Souk Ahras city indicating the urban form of the informal settlements and the urban center. [Online]. Available at: <https://satellites.pro/Souk_Ahras_map#36.288118,7.953904,14> [Accessed: 13 October 2019]. [ Links ]

JONES, P. 2017. Formalizing the informal: Understanding the position of informal settlements and slums in sustainable urbanisation policies and strategies in Bandung, Indonesia. Sustainability, 9(8), paper 1436, pp. 1-27. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081436 [ Links ]

KIRONDE, L.J.M. 2006. Issuing of residential licenses in unplanned settlements in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Draft report prepared for UN-Habitat, Shelter Branch, Land and Tenure Section. Dar-es-Salaam: University College of Lands and Architectural Studies. [ Links ]

LALONDE, M. 2010. La crise du logement en Algérie: Des politiques d'urbanisme mésadaptées. Mémoire présenté â la Faculté des Etudes Supérieures en vue de l'obtention du grade de MaTtre ès science en Anthropologie, Département d'Anthropologie, Faculté des Arts et Sciences. Université de Montréal. [ Links ]

LOPEZ-MORENO, E. 2003. Slums in the world: The face of urban poverty in the new millennium, monitoring the millennium development goals, target 11 worldwide slum dwellers estimations. Nairobi, Kenya: UN-Habitat, the Global Urban Observatory. [ Links ]

MOSER, C. 1998. The asset vulnerability framework: Reassessing urban poverty reduction strategies. World Development, 26(1),pp. 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(97)10015-8 [ Links ]

OLALE, P. 2013. Implications of land tenure security on sustainable land use in informal settlements in Nairobi. Unpublished thesis (MA) Environmental Law. Nairobi: University of Nairobi. [ Links ]

PAYNE, G. & DURAND-LASSERVE, A. 2012. "Holding on: Security of tenure types, policies, practices and challenges". Research paper prepared for the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing. [Online]. Available at: <http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Housing/SecurityTenure/Payne-Durand-Lasserve-BackgroundPaper-JAN2013.pdf> [Accessed: 24 October 2019]. [ Links ]

SEMMOUD, N. 2015 Governing informal urbanisation or "governance" in question. The case of the Maghreb cities. In: Bennafla, K. (Ed.). Acteurs et pouvoirs dans les villes du Maghreb et du Moyen-Orient. Paris, France: KARTHALA, e-book. [ Links ]

SRINIVAS, H. 2005. Urban squatters and slums: Defining Squatter Settlements. GDRC Reseaarch Output E-036. Kobe, Japan: Global Development Research Center. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.gdrc.org/uem/squatters/deflne-squatter.html> [Accessed: 2 December 2009]. [ Links ]

UNECE (UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE). 2009. Self-made cities: In search of sustainable solutions for informal settlements in the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe region. New York - Geneva. UN-HABITAT. [ Links ]

UN-HABITAT. 2001. Cities in a globalising world: Global report on human settlements. London, Sterling: Earthscan Publications Ltd. [ Links ]

UN-HABITAT. 2003a. The challenge of slums: Global report on human settlements. London, Sterling: Earthscan Publications Ltd. [ Links ]

UN-HABITAT. 2003b. Handbook on best practices. Security of tenure and access to Land. Implementation of the Habitat Agenda. Nairobi. Kenya. [ Links ]

UN-HABITAT. 2008. Secure land rights for all: Global land tools network. Nairobi, Kenya. [Online]. Available at: <https://gltn.net/2008/11/08/secure-land-rights-for-all/> [Accessed: 13 October 2019]. [ Links ]

UN-HABITAT. 2011. Monitoring security of tenure in cities: People, land, and policies. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Human Settlements Programme. [ Links ]

UN-HABITAT. 2016. Habitat III Issues Papers 22-Informal Settlement. United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development, New York, 31 May 2015. [Online]. Available at: <https://unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Habitat-III-Issue-Paper-22_Informal-Settlements.pdf> [Accessed: 13 October 2019]. [ Links ]

VALERY, A. 2013. Postcolonialising informality. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 31, pp. 4-22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1068/d14410 [ Links ]

WOODRUFF, C. 2001. Review of De Soto's "The mystery of capital: Why capitalism triumphs in the West and fails everywhere else". Journal of Economic Literature, 39(4), pp. 1215-1223. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.39.4.1215 [ Links ]

YIN, R. 2014.Case study research: Design and methods. 5th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Peer reviewed and revised October 2019

Published December 2019

* The authors declared no conflict of interest for this title or article

1 These deeds will serve as a legal document to prove the ownership of land and permit land regularisation in the future.