Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Town and Regional Planning

On-line version ISSN 2415-0495

Print version ISSN 1012-280X

Town reg. plan. (Online) vol.75 Bloemfontein 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp75i1.3

ARTICLES

Exploring some of the complexities of planning on 'communal land' in the former Transkei

'n ondersoek na sommige beplanningskompleksiteite van 'gemeenskaplike grond' in die voormalige transkei

Hlahlobo ea a mang a mathata a tlisoang ke meralo ea lefatshe sebakeng sa transkei ea mehleng

Tanja Winkler

Associate Prof, School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics, Deputy Dean: Transformation and Social Responsiveness, Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment, University of Cape Town, Private Bag X3, Rondebosch, South Africa, 7701. Phone: +27 (0)21 650 2360, e-mail: <Tanja.Winkler@uct.ac.za>

ABSTRACT

'The land question' in South African national politics continues to dominate party-political battles. However, most of these battles refrain from engaging with 'communal' landholdings that are under the custodianship of traditional leaders. Of further concern, the legislation not only remains ambiguous about traditional leaders' land administration functions and powers, but it is also conceptualised within Western frameworks. Ambiguity and Western centricity, in turn, hinder planning efforts and municipal service delivery in South Africa's rural regions, while residents continue to live without tenure security and enhanced socio-economic prospects. By focusing on 'communal land', this article revisits African indigenous land laws, in order to gain a deeper understanding of contemporary tenure practices on 'communal' landholdings. The article identifies some of the planning complexities found in former Transkei. Possible recommendations include following an area-based approach to planning where community property associations (or similar structures) are explored with residents of some 'communal' landholdings, while traditional leadership structures are explored in other contexts. All role players should thus have equal decision-making powers over local land administration and development.

Keywords: 'Communal land', traditional leaders, rural planning, tenure insecurity

ABSTRAKTE

In die Suid-Afrikaanse nasionale politiek oorheers 'die grondvraag' steeds party-politieke gevegte. Die meeste van hierdie gevegte skram egter weg van die 'gemeenskaplike' grondbesittings wat onder toesig van tradisionele leiers is. Verdere kommer is dat wetgewing nie net dubbelsinnig is oor die funksies en bevoegdhede van tradisionele leiers se grondadministrasie nie, maar dit word ook binne Westerse raamwerke gekonseptualiseer. Dubbelsinnigheid en Westerse sentraliteit belemmer op hul beurt die beplanningspogings en munisipale dienslewering in Suid-Afrika se landelike streke, terwyl inwoners voortgaan om sonder verblyfreg en beter sosio-ekonomiese vooruitsigte te leef. Deur op 'kommunale grond' te konsentreer, word hierdie inheemse grondwette in Afrika heroorweeg om 'n dieper begrip te kry van hedendaagse verblyfreg op 'gemeenskaplike' grondbesittings. Die artikel identifiseer sommige van die beplanningskompleksiteite wat in die voormalige Transkei gevind is. Moontlike aanbevelings sluit in dat 'n gebiedgebaseerde benadering tot beplanning gevolg word waar gemeenskaps-eiendomsverenigings (of soortgelyke strukture) ondersoek word met inwoners van sommige 'gemeenskaplike' grondbesittings, terwyl tradisionele leierskapstrukture in ander kontekste ondersoek word. Alle rolspelers moet dus gelyke besluitnemingsbevoegdhede oor plaaslike grondadministrasie en ontwikkeling hê.

Sleutelwoorde: 'Gemeenskaplike grond', landelike beplanning, onveiligheid in verblyfreg, tradisionele leiers

TUMELO

Taba ea lefatshe naheng ea Afrika Borwa e tsoela pele ho nka maemo a pele likhohlanong tse teng lipakeng tsa mekha ea lipolotiki. Le ha hole joalo, likhohlano tsena hali na tabatabelo ea ho fumana maikutlo a baahi ba lulang metseng e busoang ke marena. Se tshoenyang ke hore molao oa naha ha o hlakise ka botlalo maikarabelo le matla a marena mabapi le tsamaiso ea lefatshe. Ka nqa e nngoe, molao o ikamahanya le mekhoa ea linaha tsa mose, 'me hona ho sitisa tsoelopele e ka tlisoang ke limmasepala tsa metse ea mahaeng a Afrika e Borwa. Molemong oa kutloisiso e batsi, sengoliloeng sena se lekola mekhoa e neng e sebelisoa nakong e fetileng tsamaisong ea lefatshe metseng e mahaeng. Se boetse se shebisisa mathata a tobaneng le thero ea lefatshe Transkei ea mehleng. Likeletsong tse fanoeng, sengoli se bontsha molemo oa thero ea lefatshe e ikamahanyang le semelo sa sebaka seo, e kenyeletsang maikutlo a bohle ba amehang, 'me bohle ba nka karolo liqetong tse nkuoang mabapi le lefatshe la mahaeng.

1. INTRODUCTION

The Economic Freedom Fighters' (EFF) successful political campaign to mobilise land as a symbol of colonial and apartheid theft has placed 'the land question' at the centre of South Africa's party-political battles (Kepe & Hall, 2018). For the EFF, the ruling African National Congress (ANC) has failed to address this theft, thereby fuelling their calls for "the land to be nationalised and returned to the black African majority [via] expropriation without compensation" (EFF, 2019: 9). Expropriation without compensation, in turn, necessitates amendments to Section 25 of the Constitution of South Africa (RSA, 1996). Yet, during these strident political confrontations over land ownership, the topic of 'communal land' - which is officially state-controlled trust land - hardly ever surfaces as a matter of urgent concern. Said differently, and in the words of a research participant:

The many debates in parliament are all about commercial farms and private landholdings. But we are failing to deal with 'communal land'. We must first address this issue before we can talk about land expropriation without compensation. We can run away from this issue, but this will only exacerbate existing problems in South Africa's rural regions (Shasha, 2019: personal interview).

At least 17 million South Africans live on 'communal' landholdings that are under the jurisdiction and custodianship of approximately 800 traditional leaders (Oomen, 2005; Branson, 2016).1 Most of this land, however, continues to be held in trust by the state, which is a remnant of the 1936 Native Trust and Land Act. While this Act was repealed in 1991, residents of 'communal' landholdings continue to live without tenure security (Du Plessis, 2011). Neither they nor traditional leaders officially own the land. As residents of 'communal' landholdings occupy and use land under a system of rights that is conveyed through oral traditions, this land is neither documented nor registered under the formal cadastre (Hull, Sehume, Sibiya, Sothafile & Whittal, 2016). Residents are, therefore, not formally recognised as legal land-rights holders; hence, their tenure insecurity. Furthermore, while 'communal' landholdings are under the custodianship of traditional leaders, their functions and powers regarding rural land administration2 remain undefined, despite the fact that institutions of traditional authorities are recognised in the Constitution (RSA, 1996), the Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act (RSA, 2003), and the Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (SPLUMA) (RSA, 2013). To worsen matters, "land administration [in South Africa's rural regions] was officially haltered by the state in 1996 without repealing the legislation governing land allocations" (Coleman, 2019: personal interview; cf. also Hull et al., 2016). Legal ambiguity over who controls 'communal' landholdings and land-allocation functions is hampering planning efforts and municipal service delivery in South Africa's rural regions. Here too we encounter rapid rural densification (Wotshela, 2018). However, this type of densification is different from processes emerging in Asia, where rural regions are becoming high-density zones of industrial ventures in place of small-scale agrarian activities (Mughal, 2018; Tan & Ding, 2008). By contrast, over 50% of South Africans living on 'communal' landholdings depend on state-issued social grants as their main source of income, while supplementing this income with subsistence farming practices (Budlender, Mgwebe, Motsepe & Williams, 2011; Ntingi, 2016). Of further concern, the idea of 'rural planning' seems to be counterproductive to the state's post-agrarian vision (as explained later). Instead, the state seems to be influenced by global trends and the policies of multilateral organisations that have turned their focus to urbanisation and the unprecedented growth of cities in the global South via programmes including the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals and the New Urban Agenda. While an urban focus is important, it should not result in diminished rural attentions. Nor should planners establish unhelpful urban-rural binaries, for urbanisation in the South African context tends to be cyclical and not linear in nature (as discussed later).

By focusing on 'communal land' in the former Transkei (of the present-day Eastern Cape province of South Africa), this article aims to explore some of the complexities concerning 'the land question' that are seemingly bypassed by the state and its political opponents. Here, institutional uncertainties and municipal service backlogs are most acute (Gobeni, 2019: personal interview). As a result of dysfunctional state structures, traditional leaders continue to perform land-administration functions, even if they are not legally mandated or supported to do so.

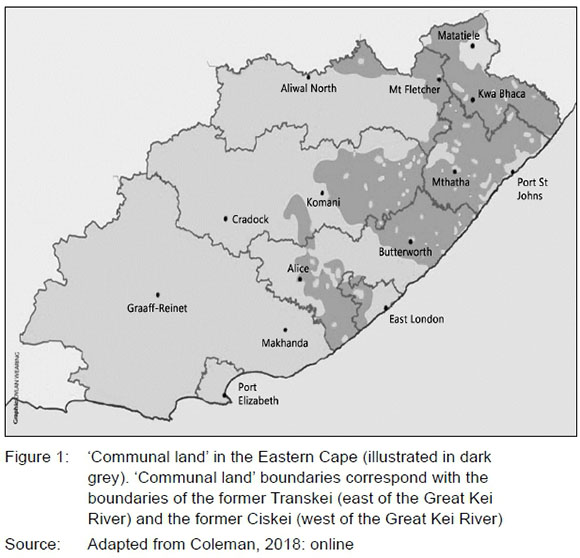

A study conducted by Hawkins & Associates in 1980 estimated that 80% of the total land mass of the Transkei comprised 'communal' landholdings, while urban land occupied only 1.3% (Hawkins & Associates, 1980). Within these 'communal' landholdings, conditional tenure permits were issued to residents via Permission to Occupy (PTO) certificates (Hawkins & Associates, 1980). PTO certificates entailed, and continue to entail, only a use right, thereby making PTOs a less secure form of tenure than freehold or quitrent tenure rights (Hull et al., 2016).3Furthermore, 80% of the total land mass of the former Transkei remains designated as 'communal land', despite a quarter of a century of post-apartheid governance (Coleman, 2018; cf. Figure 1).

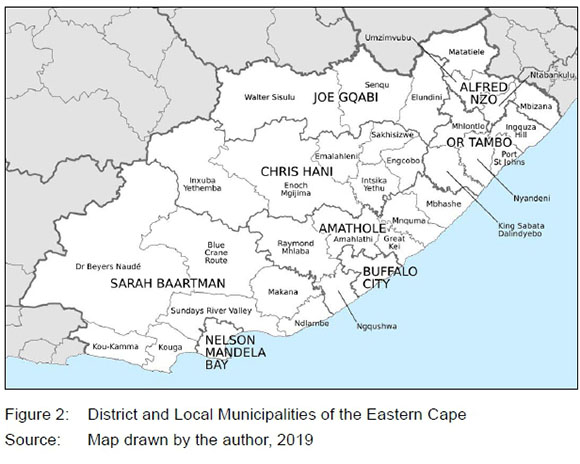

The former Transkei comprises portions of Ave District Municipalities (DMs) that represent some of the worst-resourced councils in the country (Coleman, 2018: online). DMs are further divided into Local Municipalities (LMs) that bear responsibility for municipal services and local development (cf. Figure 2).

But these responsibilities are curtailed by an insignificant tax base, since residents of 'communal land' are precluded from paying municipal rates and taxes (Tobia, 2019: personal interview). As a consequence, LMs rely almost exclusively on national and provincial government disbursements to implement planning projects and engineering infrastructure (Bennett, Ainslie & Davis, 2013).

Research findings presented in this article are based on case study research methods that include participant observations and ten in-depth interviews with directors and senior officials of planning and engineering departments at DMs and LMs, a retired official, a traditional leader, two planning consultants, a professor of history based at the University of Fort Hare, and a focus group interview with community and economic development officials. Archival research methods are also used to access historical records. The overarching aim of this research is not only to explore some of the complexities of planning on 'communal land' in the former Transkei, but also to demonstrate the predominantly Western focus of South African land laws that continue to inhibit more creative responses to everyday rural realities. This Western-centric concern is relevant to planning, for it has an impact on the lives of a significant number of rural residents who continue to engage in aspects of precolonial tenure practices, regardless of the insidious land laws passed under colonialism and apartheid.

This article is structured in three parts. It begins by revisiting African indigenous land laws, in order to gain a deeper understanding of contemporary tenure practices on 'communal' landholdings. The focus then shifts to current planning complexities in the former Transkei, before turning to possible recommendations.

2. LAND TENURE REVISITED

Land tenure reform was, and remains, a key policy concern in South Africa. Accordingly, the 1997 White Paper on South African Land Policy explicitly sought to address tenure reform by recommending a unified system of land rights, while recognising residents' de facto rights on 'communal land'. It also recommended the transfer of state-controlled trust land to individuals or communities via a Western land titling approach. The idea of extending private landownership rights to rural residents on either an individual or a group-held basis found further expression in the promulgation of the Communal Land Rights Act of 2004 (RSA, 2004). If group-held ownership rights were sought for 'communal' landholdings, these landholdings would be administered and managed by traditional leaders (RSA, 2004). However, in 2010, the Communal Land Rights Act was deemed to be unconstitutional, due to a procedural technicality. Nevertheless, its uncritical subscription to Western land titling approaches is reiterated in SPLUMA (RSA, 2013) and its accompanying regulations (RSA, 2015). "Most of the legislation [thus remains] very European in its approach, and it fails to incorporate existing tenure systems on 'communal land' [that predate the colonial era]" (Koetze, 2019: personal interview). This claim is corroborated by a planning consultant (Jonas, 2019: personal interview).

2.1 African indigenous land laws

For scholars of African indigenous land laws, the idea of absolute ownership is an inappropriate resolution to the complex tenure practices found on 'communal land' (Bennett, 2004; Claassens, 2014; Du Plessis, 2011; Lavigne Delville, 2007; Meinzen-Dick & Mwangi, 2009; Mnisi Weeks, 2018; Okoth-Ogendo, 2008). Absolute ownership, they argue, ignores residents' multiple land interests, and the embedded and overlapping nature of indigenous tenure systems that partially survived the insidious land laws passed under colonialism and apartheid.

Over three decades ago, Okoth-Ogendo (1989: 7) argued that it is futile to explain African indigenous land laws from a Western epistemic that directs enquiry into "whether or not African social systems recognise institutions of ownership; and if they do, who in society - the chief, the family, the clan, or the lineage - is the repository of that ownership". Instead, Okoth-Ogendo (1989; 2008) as well as Winkler and Duminy (2016) suggest that planners explore the meaning and nature of property in African onto-epistemologies, by asking meta ethical questions such as, for example: What is the meaning and nature of property in land in African socio-political orders? For Okoth-Ogendo (2008), the meaning and nature of property in African onto-epistemologies is derived not only from how individuals or groups relate to a physical place, but also from how individuals relate to all members of a community and vice versa. What this sociopolitical order then establishes is not a property right over a specific parcel of land, but rather a set of reciprocal rights and obligations that bind together and confer power over land in community members (Winkler & Duminy, 2016). Reciprocal and obligatory rights are understood as a continuous performance and not as a finite action, as found in Western landownership laws (Bennett, 2004; Hull et al., 2016). This continuous performance of reciprocal and obligatory rights determines who may have access to land and its associated resources. This alternative conceptualisation of property in land also determines who controls and manages associated resources on behalf of those who have access to the land. A conceptual distinction is, therefore, drawn between the manner in which access to land is obtained, and the manner in which land resources are controlled and managed (Cousins, 2007; Claassens, 2014).

2.2 Access and control under indigenous land laws

"Access to land is essentially a function of membership in the family, clan, lineage or wider community, and it is available to any individual on account of that membership" (Okoth-Ogendo, 2008: 100).

This membership-based access is maintained through active participation in the production and reproduction of the sociopolitical, economic and spatial organisation of a community. Since individuals engage in a range of production and reproduction activities within a community, rights of access encompass multiple phenomena. Put differently, "individuals, families or lineages could each simultaneously hold a bundle of access rights" that are embedded and overlapping in nature (Okoth-Ogendo, 2008: 100, my emphasis).

Control, on the other hand, occurs primarily for the purpose of securing access rights to land (Cousins, 2007). This control is typically vested in, and exercised by the political authority of the wider community (Okoth-Ogendo, 2008). However, this authority is not monolithic in nature, but rather segmented both vertically and horizontally. To illustrate the segmented nature of land administration in indigenous land laws, Okoth-Ogendo (2008) suggests imagining an inverted pyramid, where the tip of the inverted pyramid represents a household's control over cultivation and residential land use. The centre of the pyramid represents the clan's or lineage's control over land designated for grazing, hunting or other socio-economic activities, while the base of the inverted pyramid represents the wider authority that is responsible for territorial expansion, defence mechanisms, socio-economic sustainability, and settlement dispute resolutions. Controlling and managing land resources are then not the purview of a singular authority, as is the case in Western models of land administration (Claassens, 2014; Mnisi Weeks, 2018). Rather, these functions are shared and distributed across all three layers of the inverted pyramid, since households, clans, and the wider authority all respond to issues of land allocation, distribution, and sustainable resource management. Furthermore, this mode of land administration is purposefully designed to secure individuals' tenure rights by virtue of their membership in a community. These principles encompass useful frameworks for understanding how land-tenure systems functioned, and continue to function, to some degree, thereby prompting scholars to argue for the inclusion of aspects of these principles in contemporary land-tenure policies (Bennett, 2004; Cousins, 2007; Okoth-Ogendo, 2008; Du Plessis, 2011; Claassens, 2014).

2.3 Precolonial land tenure in the former Transkei

Okoth-Ogendo's (1989; 2008) precolonial land-tenure thesis is supported by anthropological and historical evidence found in the former Transkei (Hunter, 1936; Hammond-Tooke, 1968; Peires, 1982; Soga, 2013). In this instance, membership in a community was essential to tenure security, while control over land administration was layered in nature. The principle that bound members of a community together was the recognition of a chief who was either a member of, or a descendant from a royal family (Delius, 2008). The base of Okoth-Ogendo's inverted pyramid was thus occupied by chiefs and their council of elders who often conferred with all members of a community (Hunter, 1936). Larger chiefdoms were divided into wards (iziphaluka) consisting mainly, but not exclusively of kin who lived together in localised areas, and whose land resources were administered by subordinate headmen (Hammond-Tooke, 1968). Wards, therefore, resembled Okoth-Ogendo's intermediary layer of political authority. Still, it is important to re-emphasise that control over cultivated lands and homesteads (umzi) remained vested in individual households (Hunter, 1936; Mager & Velelo, 2018). Grazing land was accessible to all livestock owners. In addition to wider administrative functions, chiefs were also responsible for initial land allocations (Hammond-Tooke, 1968). If a household necessitated additional land for residential use, they approached the headman of the ward to allot this land (Delius, 2008). Among the amaPondo of the present-day Eastern Cape, married women selected their own fields for cultivation. Once they had turned over the soil, they had an exclusive access right over these fields (Hunter, 1936). The only restriction to this right was ensuring non-encroachment on someone else's cultivated fields. It was thus unusual for chiefs to reclaim land or to deny members of a community access to land (Mager & Velelo, 2018). Those who did so for unjustifiable reasons, lost support and followers, since "the right to depose unjust rulers was an integral part of indigenous Xhosa political culture" (Peires, 2014: 17).

2.4 Colonial and apartheid land tenure

However, the initial assimilationist policies of the British Cape Colony sought to promote individual tenure throughout the annexed chiefdoms of the Ciskeian and Transkeian territories (Mager & Velelo, 2018). Former chiefdoms west of the Great Kei River were, accordingly, subdivided, surveyed, and sold by the Crown as freehold farms to anyone who could afford the asking price, including wealthier refugees from vanquished chiefdoms (Wotshela, 2018). In addition to selling conquered lands to White settlers and a few Black elites, the colonial government also sought - via the Natives Locations and Commonage Act of 1879 - to transform rural settlement patterns into 'organised' and spatially 'acceptable' villages, where nuclear families would live on subdivided residential plots with annually renewable quitrent titles (Wotshela, 2014; 2018).

This Western planning logic, however, failed to respond to existing tenure practices and livelihood strategies. Regardless, and with the promulgation of the Glen Grey Act in 1894, quitrent tenure was extended east of the Great Kei River to nine of the twenty-six magisterial districts of the Transkeian territories (Coleman, Wotshela, 2019: personal interviews). In this instance, 26 594 quitrent titles were registered with the Surveyor General's Office, but many more applications were never processed, because quitrent title deeds were only issued after surveying costs were paid (Cousins, 2007; Wotshela, 2014).

The bulk of the remaining land within the Transkeian territories was classified as 'communal tenure' under the 1879 Act. A considerable portion of this land was never surveyed, and it remains unsurveyed to this day (Hull et al., 2016). Instead, it was designated as a 'native reserve' under the Union government's Native Trust and Land Act of 1936, which resolved to turn the 'native reserves' into state-controlled trust land under the control of the South African Native Trust (SANT) (Du Plessis, 2011). Residents thus became trust tenants on 'communal land', while freehold and quitrent tenure rights were no longer available to them in accordance with the 1936 Act (Claassens, 2014).

Under the apartheid government, the SANT was renamed the South African Development Trust (SADT). Control over this land remained vested in the state. As such, the Bantu Authorities Act of 1951, which governed SADT land, did not confer landownership rights to traditional leaders (Mager & Velelo, 2018). Rather, it delineated a 'tribal' authority's area of political jurisdiction and granted this authority some land-administration duties (Delius, 2008). Many traditional leaders, however, interpreted these duties as their right to allocate land (De Wet, 1989). Instead of following the convoluted land-allocation process set out in the 1951 Act, the vast majority of the traditional leaders allocated land directly to residents (Ntsebeza, 2008). As a result, many residents never received formal PTO certificates (Cousins, 2007; Wotshela, 2018).

Regardless of informal land-allocation practices, further entrenchments of institutionalised segregation came via the implementation of Proclamations 31 and 264 of 1939, 116 of 1949, and R188 of 1969, which collectively imposed strenuous regulations on 'communal land', including the segregation of residential activities from agricultural and grazing activities, the fencing off of agricultural land, a 'one-man-one-plot' condition, and restricted plot sizes (Wotshela, 2018). These Proclamations were also engineered to systematically eliminate all quitrent rights by replacing these tenure rights with PTOs (Cousins, 2007). According to one research participant, many of these Proclamations are "vicious pieces of legislation that remain in use in the former Transkei, since they were never repealed" (Coleman, 2019: personal interview).4 It should also be noted that, with the promulgation of the Bantu Self-Government Act in 1959, the 'native reserves' were converted into four 'homelands' (Transkei, Ciskei, Bophuthatswana, and Venda), and six 'self-governing territories' (KwaNdebele, QwaQwa, Gazankulu, Lebowa, KwaZulu-Natal, and KaNgwane). 'Homelands' and 'self-governing territories' remained state-controlled trust landholdings under SADT (Du Plessis, 2011: 45).

3. UNDERSTANDING THECURRENT COMPLEXITIES OF 'COMMUNAL LAND' IN THE FORMER TRANSKEI

A history of colonial conquest, violent land expropriation and segregationist laws has left indelible marks on South Africa's rural landscape (Mager & Velelo, 2018). Land administration has, for the most part, collapsed in South Africa's rural regions: PTOs may or may not be issued; registers of rights holders are seldom updated, and land allocation takes place on an ad hoc basis without legal security (Cousins, 2007). Despite, or perhaps because of defunct government systems, "indigenous norms and structures in relation to property have demonstrated great resilience in the face of colonial and post-colonial policies" (Cousins, 2007: 292). While there are dangers in abstracting institutional concepts from specific moments in history - for such abstractions might become prone to essentialist understandings that are inconsistent with contemporary and ever-fluid practices in rural settings - Cousins (2007), nevertheless, posits that conceptual understandings of indigenous land laws remain relevant, because such understandings might allow planners to critically interrogate Western-legal forms of private property.

3.1 Inadequate planning legislation

Yet, as mentioned earlier, SPLUMA (RSA, 2013) assumes a taken-for-granted norm that land is owned in accordance with Western conceptualisations of property, and bounded.

The first two questions of any planning application are: Who owns the land? And, where are the boundaries? Well, on 'communal land' there aren't any answers to these questions. So, you can't make a planning application if you're on 'communal land'. SPLUMA simply excludes 'communal' land rights holders, and Schedule 2 of SPLUMA [which refers to land use categories] completely ignores what is happening on 'communal land' (Coleman, 2019: personal interview).

Key assumptions about absolute ownership remain unchallenged, while "communal land administration - from a development control perspective - is still a taboo subject, because of the contradictions found between 'communal' tenure practices and the SPLUMA expectations" (Tobia, 2019: personal interview). Moreover, taken-for-granted norms preclude any acknowledgement of, or means to address ongoing tenure insecurity. This preclusion surfaces most acutely when it comes to municipal service delivery, planning, and agrarian development (Coleman, Gobeni, Sako, 2019: personal interviews). SPLUMA also uncritically accepts the spatial demarcation of traditional councils as established by the 1951 Bantu Authorities Act and reinforced via the Traditional Leadership Framework Act (RSA, 2003). However, areas under the jurisdiction of contemporary traditional councils hardly ever align with established municipal boundaries (Koetze, 2019: personal interview). Traditional leaders are, therefore, obliged to navigate the planning and budgetary priorities of multiple local municipalities (Moshoeshoe, 2019: personal interview), while ward councillors need to deliberate with different traditional leaders over service delivery and development proposals (Bennett et al., 2013). Of equal concern, contentious landownership issues remain unresolved (Oomen, 2005), thus creating in the minds of municipal officials, traditional leaders and residents alike an incorrect presumption that "communal land is owned by the chiefs" (Gobeni, 2019: personal interview). This misunderstanding of landownership persists, despite Deputy President Mabuza's statement to the National Assembly in May 2018 that "insecure land tenure emanates from the false view that land under traditional leadership is owned by traditional leaders" (Mabuza, cited in Mnisi Weeks, 2018: 3).

On the whole, SPLUMA is vehemently criticised by agrarian, land and legal scholars for devolving too many powers to traditional councils (Claassens, 2014; Hall & Kepe, 2017). Yet, and somewhat ironically,

[t]raditional leaders are [also] very resistant to accept SPLUMA, because they believe that it will take away their land. As planning officials, we want to work with traditional leaders. But they don't trust us, because of SPLUMA (Gobeni, 2019: personal interview).

Unlike the acclaim SPLUMA receives in urban contexts, its relevance in rural settings remains doubtful. "SPLUMA seems to be geared only [towards] urban planning, and it bypasses rural development needs" (Koetze, 2019: personal interview). Regardless of a perceived urban bias, Regulation 19 of SPLUMA (RSA, 2015) recommends that traditional councils enter into "service level agreements with local municipalities" for the purpose of "outsourcing some planning functions to traditional councils". But SPLUMA's regulations refrain from explicitly stating which planning functions may be outsourced. Of further concern, traditional councils are excluded from planning and land-use management decisions in accordance with the Constitution (RSA, 1996) and the SPLUMA regulations (RSA, 2015). It is this decision-making exclusion that traditional leaders And most unpalatable (Moshoeshoe, 2019: personal interview). To engender further confusion, the regulations go on to suggest that, if traditional councils choose not to engage in service level agreements, they are then responsible for land allocation, thereby nullifying any need to engage in a service level agreement in the first place (Nogcinisa, 2019: personal interview).

3.2 Duplicated functions and ineffective ward councillors

A general lack of clarity and guidance found in the planning legislation serves only to create untenable situations, in which municipal officials, elected ward councillors, and traditional leaders are constantly embroiled in 'conflicting rationalities', to use Watson's (2003) argument, while residents continue to live with inadequate services, without tenure security, and without prospects for enhanced socio-economic opportunities. At least two officials from different municipalities cite cases where traditional leaders have deliberately hindered the implementation of infrastructure projects (Gobeni, Nogcinisa, 2019: personal interviews), while a different rationality reveals that municipal budgeting priorities are often ignorant of residents' livelihood strategies and everyday hardships (Moshoeshoe, 2019: personal interview). "We just have to endure the pain of living without infrastructure and services, because things are done via budgets and without consultation. But we are here to assist the municipality as much as we [can]" (Moshoeshoe, 2019: personal interview). Furthermore, a lack of clarity regarding traditional leaders' precise duties vis-â-vis ward councillors' duties is creating factionalised insurrections at the expense of collective action.

Ward councillors are constantly fighting with traditional leaders, because of a duplication of duties. But there is no need for many different meetings, or for fighting that ends up in doing nothing for the community. We all need to discuss the same issues under one roof and take these issues forward to the municipality, so that they are in the municipality's Integrated Development Plan (IDP). But fighting is dividing the community, because some members support the traditional leadership, while others support the ward councillor (Moshoeshoe, 2019: personal interview).

"Duplicated - in fact, quadruplicated - functions are not only inefficient; they are also a waste of money" (Coleman, 2019: personal interview). A duplication of duties and functions is equally found between DMs and LMs, and between municipalities, provincial and national tiers of government, thereby adding layers of bureaucracy to an already ineffective planning system.

The biggest problem is that you've got Local and District Municipalities, provincial and national departments of government all doing the same thing. These different departments and municipal structures are supposed to communicate with each other and align their ideas in municipal Integrated Development Plans (IDPs) and Spatial Development Frameworks (SDFs). But, they don't (Koetze, 2019: personal interview).

To engender further inefficiencies, many ward councillors are failing to fulfil their 'developmental' and 'participatory' mandates - as envisaged in the Municipal Systems Act (RSA, 2000) - and this failure culminates in a loss of confidence in their abilities, since residents tend to "trust traditional leaders more than the ward councillors" (Nogcinisa, 2019: personal interview).

Ward councillors don't report to communities on municipal projects, and they don't come back to the municipality and report on what is happening on 'communal land'. Also, if chiefs call a community meeting, people come. There's respect for the chief. When ward councillors call a meeting, people don't attend (Nonkula & Skhosana, 2019: personal interview).

3.3 Self-serving political directives

Officials are also often encumbered by irrational and self-serving political directives that obviate and override established plans. To be clear: "The political leadership [of the municipality] wants immediate action, and because of this they ignore our spatial plans" (Nogcinisa, 2019: personal interview). "Our elected municipal councillors simply go ahead and make decisions without consulting our IDPs and SDFs" (Gobeni, 2019: personal interview). Since it appears that "elected councillors are blinded by political ambition" (Koetze, 2019: personal interview), when officials provide technical reasons for why certain interventions might not be feasible, they are perceived as "frustrating the political administration of the municipality" (Sako, 2019: personal interview). By contrast, "traditional leaders are not swayed by party politics. They are there for the people all the time" (Sako, 2019: personal interview).

Elected municipal councillors' poor performance may further be attributed to their inability, or unwillingness, to engage in debates concerning agricultural development, since, as argued by Ainslie and Kepe (2016), their post-agrarian standpoints conform to the state's 'modernisation via urbanisation' rhetoric at the expense of investing in small-scale agricultural developments. This rhetoric is confirmed by the planning director at a DM who is critical of "the National Development Plan (NDP) [which assumes] that South Africa will be 80 percent urbanised by 2030" (Shasha, 2019: personal interview). Scant results from interventions such as the Rural Agro Industrialisation and Finance Initiative (RAFI) - which was launched in the Eastern Cape in 2017 for the purpose of supporting smallholder farmers - serve only to galvanize the state's myopic standpoint that investments in urban economies are more fruitful than rural planning (Nonkula & Skhosana, 2019: personal interview). Traditional leaders, on the other hand, recognise the fact that processes of urbanisation in South Africa are not linear in nature, namely that rural residents migrate to urban centres and never return to their ancestral homes (Moshoeshoe, 2019: personal interview). Many residents do return. If they choose not to return for economic or other reasons, they still tend to maintain some social or spiritual connection to their rural homes (Moshoeshoe, 2019: personal interview). Accordingly, traditional leaders see value in prolonged state support for small-scale agricultural activities, even if results from RAFI-type investments take longer than originally anticipated (Moshoeshoe, 2019: personal interview).

3.4 Land administration vacuum

In 2009, the National House of Traditional Leaders was endorsed by the state to establish Provincial Houses of Traditional Leaders in all six of the nine provinces where traditional authorities are formally recognised. The Eastern Cape House of Traditional Leaders (ECHTL) is assigned an annual budget of approximately R9 million, in order to facilitate and implement the findings from six committees, including the indispensable Rural Development and Agrarian Reform Committee (Ainslie & Kepe, 2016), which is tasked with "providing support to government departments in the delivery of food security and livestock improvement programmes; protecting the environment and supporting eco-cultural tourism; participating in land use management programmes; and accelerating the involvement of traditional leaders in rural development initiatives" (Ainslie & Kepe, 2016: 27). However, as argued by Ainslie and Kepe (2016), it remains unclear how, when, and by whom these tasks will be operationalised. And since traditional leaders are excluded from municipal planning tribunals, it also remains unclear how they are supposed to participate in land-use management programmes for the purpose of accelerating rural development initiatives.

There is no link between the local authority and the traditional authority, because the law doesn't allow us to recognise traditional authorities as decision-makers. Traditional authorities feel that our SDFs, IDPs, et cetera are imposed on them because they are excluded from the planning tribunals. They should be part of these tribunals, because the minute you are part of the tribunal you are part of the decision-making structure. Traditional authorities are actually regulating and facilitating development on 'communal land' (Nonkula & Skhosana, 2019: personal interview).

Dysfunctional state structures, measly state budgets for rural development programmes, ineffective councillors, a relatively high turnover of officials, and a "complete vacuum of land administration in the Eastern Cape" all serve to strengthen traditional leaders' positions, despite their deliberate exclusion from formal decision-making processes (Coleman, 2019: personal interview). In fact, traditional leaders are "filling the state-created vacuum by taking on greater land administration roles" (Coleman, 2019: personal interview). However,

[t]raditional leaders allocate land on an ad hoc basis and without consulting the municipality. But there are no plans for water reticulation, sanitation, electricity, roads, schools or clinics. And once residents move onto the land, they start protesting for services. But we have not budgeted for services on that land in terms of our IDPs. That piece of land might also be allocated for future development in terms of our SDF. But this doesn't matter. The political leadership of the municipality wants us to provide services regardless of the IDPs or SDFs, so that the protests stop (Shasha, 2019: personal interview).

Rural landholdings are subdivided on an ad hoc basis without any recognition of established plans. Such ad hoc practices result not only in a loss of economically viable land, but also in unsustainable rural densifications, since 'communal' landholdings remain attractive to residents for economic reasons.

Rapid development on erstwhile productive agricultural land is resulting in a loss of economically viable land. 'Communal land' continues to be subdivided without formal approval, and these subdivisions are unregistered. This informal approach is very attractive to residents, because 'communal land' is free of municipal rates and taxes. But this isn't viable from a municipal planning and an income-generating perspective (Tobia, 2019: personal interview).

4. DISCUSSIONS, RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

It would appear that planning in the former Transkei has become a futile exercise. The pressing issue, as argued by Bennett et al. (2013: 37), is knowing "how to combine the twin goals of land administration and local development in institutions that are both streamlined and have widespread social legitimacy". In response, Bennett et al. (2013: 37) suggest that the responsibility for both local land administration and development be vested in decentralised democratic structures such as community property associations (CPAs), because institutions of traditional authorities are "incompatible with modernity". Members of a state-endorsed and -funded CPA are residents who are elected by other residents to manage 'communal' landholdings and negotiate development opportunities with a municipality.5Yet, Bennett et al. (2013: 37) also acknowledge that previous "attempts at decentralised control through CPAs have largely failed". Reasons for this failure are attributed to a lack of ongoing state support for CPAs after their initial formulation (Kingwill, 2008; Bennett et al., 2013).

4.1 The problem with universal solutions

Herein lies a problem that goes beyond state support. Scholars and policymakers are continually searching for universal solutions, as epitomized by SPLUMA's (RSA, 2013: Section 3) overarching goal, which is to establish "a uniform and comprehensive system of planning across South Africa".6Universal grammars, however, ignore complex historical forces - and ever-shifting political alliances - that continue to shape South Africa's different geopolitical regions (Mbembe, 2001). In other words, "there simply cannot be a uniform approach for all of South Africa, because everywhere is different" (Coleman, 2019: personal interview). "There is no one-size-fits-all solution" (Shasha, 2019: personal interview). The problem concerning universal solutions applies equally to traditional leaders as it does to CPAs.

A system of traditional leadership cannot be uniformly applied across the country as the state is trying to do. There are regions where traditional authorities won't work. In the [former] Ciskei, for example, it will not work. Once the Xhosa Ciskei chieftaincies got conquered by the British in 1879, there was a complete absence of chiefly authority until the 1950s when the apartheid state reintroduced a 'tribal' authority system. So, you can't treat the Ciskei as being the same as the Transkei, where many chieftaincies survived colonization and apartheid. And in certain areas of the [former] Transkei, we simply cannot dismiss chieftaincies (Wotshela, 2019: personal interview).

4.2 Area-based approach

Since universal solutions will continue to produce ineffective planning outcomes, alternative and situated options need to be explored. One such option might include an area-based approach to planning, where CPAs (or similar structures) are explored with residents of some 'communal' landholdings, while traditional leadership structures are explored in other contexts. Regardless of residents' preferred option, an area-based approach needs to be inclusive of all role players during the conceptualisation, iteration and implementation phases of a local area plan (Winkler, 2017). All role players should thus have equal decision-making powers. If one of the role players includes traditional leadership structures, planners may need to become more respectful of established and negotiated processes of local land administration and development:

What is often overlooked in municipal planning is that 'communal land' systems are functional. We assume that they are not functional, because we don't participate in them. But traditional leaders hold public meetings and have public participation. They have traditional council meetings that sit regularly. They have agendas, minutes, attendance registers, and meticulous record-keeping. Traditional leaders also report on their meetings to communities and the municipality. Their system is one of negotiated planning. They negotiate everything with communities before any decisions are made (Nonkula & Skhosana, 2019: personal interview).

An area-based approach will also allow planners to focus on local-scale priorities, while integrating these into DMs' and LMs' regional-scale frameworks that are currently conceptual in nature and devoid of details. "Our SDFs are very generic. We need detailed plans for local areas" (Shasha, 2019: personal interview). Such an approach to planning may also allow for independently generated funds to be earmarked for local development needs.

We generate our own funds for the community. In our area, we have a quarry that is used for building roads. We entered into a five-year contract with a construction company that is [excavating] that quarry. That money, which is R10 000 every month, enters into the traditional council's bank account which is controlled by the PFMA [the Public Finance Management Act of 2010]. We also rent land to CellC who has erected a cell phone mast on that land. We have generated close to R300 000 from that rent. We plough back all of this money into the community for development. For example, we recently renovated a preschool which was so dilapidated [that the Provincial] Department [of Education] wanted to demolish it. But we need that pre-school. So, we renovated it ourselves (Moshoeshoe, 2019: personal interview).

However, an area-based approach will not resolve contentious landownership issues. Nor will it resolve residents' tenure insecurities, dysfunctional state structures, inadequate state budgets for agrarian development, and self-serving political interests. Extensive and radical structural and legislative transformation is needed if policymakers hope to address these problems. Nevertheless, an area-based approach may facilitate alternative outcomes to ad hoc subdivisions on 'communal land', while planning for much needed engineering services and economic development opportunities. Via SPUMA's 'service level agreements' - that are devoid of clarity, and, as a result, allow for situated interpretations - all collaborators of an area-based plan could negotiate traditional leaders' precise functions and powers regarding local land administration and development vis-â-vis other role players' functions and powers.

4.3 Rethinking absolute ownership

Planners might also need to become more sensitive to the fact that absolute ownership circumscribes existing tenure practices on 'communal land'. Instead of asking: Who owns the land?, it might be more useful to ask: Who owns what interest in the land? But this question is still framed in terms of ownership. Du Plessis (2011), therefore, suggests that planners ask: In whom, for what purpose, and for how long should an allocation of power in respect of particular aspects of land be made? Current planning systems and practices, however, undermine possibilities of recognising long-established tenure practices on 'communal' landholdings that include embedded and overlapping rights based on interests, belonging, participation, flexibility, and a continuous performance of reciprocity and obligations. Current land-use management systems and practices are also ignorant of conceptual distinctions between access to land and control over land administration. Furthermore, planning laws, theories and practices default too quickly to a "rigid divide between urban and rural, modern and traditional" (Claassens, 2014: 9). As a consequence, we have not yet disentangled ourselves from Western onto-epistemologies (Winkler, 2018), while the complexities of planning on 'communal land' remain unresolved.

5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank the editors, the three anonymous reviewers and all research participants for their constructive and insightful comments.

REFERENCES

AINSLIE, A. & KEPE, T. 2016. Understanding the resurgence of traditional authorities in post-apartheid South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 42(1), pp. 19-33. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2016.1121714 [ Links ]

BENNETT, J., AINSLIE, A. & DAVIS, J. 2013. Contested institutions? Traditional leaders and land access and control on communal areas of Eastern Cape province, South Africa. Land Use Policy, 32, pp. 27-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.10.011 [ Links ]

BENNETT, T. 2004. Customary law in South Africa. Cape Town: Juta. [ Links ]

BRANSON, N. 2016. Land, law and traditional leadership in South Africa. Africa Research Institute. Briefing note 1604. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.africaresearchinstitute.org/newsite/publications/briefing-notes/land-law-and-traditional-leadership-in-south-africa/>. [Accessed: 14 June 2019]. [ Links ]

BUDLENDER, D., MGWEBE, S., MOTSEPE, K. & WILLIAMS, K. 2011. Women, land and customary law. Community Agency for Social Enquiry (CASE). Johannesburg: CASE Publishing. [ Links ]

CLAASSENS, A. 2014. 'Communal land', property rights and traditional leadership. Keynote address. Wits Institute of Social and Economic Research (WISER). University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

CLS (CENTRE FOR LAW AND SOCIETY). 2015. Communal Property Associations Brief. Rural Women's Action Research Programme. University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

COLEMAN, M. 2018. Crucial pieces of landownership knowledge still missing. Daily Dispatch. 26 July. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.dispatchlive.co.za/news/opinion/2018-07-26-crucial-pieces-of-knowledge-still-missing/>. [Accessed: 13 October 2019]. [ Links ]

COLEMAN, M. 2019. (Planning consultant). Personal interview, East London, 15 March. [ Links ]

COUSINS, B. 2007. More than socially embedded: The distinctive character of 'communal tenure' regimes in South Africa and its implications for land policy. Journal of Agrarian Change, 7(3), pp. 281-315. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2007.00147.x [ Links ]

DELIUS, P. 2008. Contested terrain: Land rights and chiefly power in historical perspective. In: Claassens, A. & Cousins, B. (Eds). Land, power and custom: Controversies generated by South Africa's Communal Land Rights Act. Cape Town: UCT Press, pp. 211-237. [ Links ]

DE WET, C. 1989. Betterment in a rural village in Keiskammahoek, Ciskei. Journal of Southern African Studies, 15(2), pp. 326-345. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057078908708203 [ Links ]

DU PLESSIS, W. 2011. African indigenous land rights in a private ownership paradigm. Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal/ Potchefstroomse Elektroniese Regsblad, 14(7), pp. 45-69. https://doi.org/10.4314/pelj.v14i7.3 [ Links ]

EFF (ECONOMIC FREEDOM FIGHTERS). 2019. Our land and jobs now! 2019 Election Manifesto. Johannesburg: EFF Publications. [ Links ]

GOBENI, N. 2019. (Senior Manager: Planning & Development, Chris Hani District Municipality). Personal interview, Komani, 7 March. [ Links ]

HALL, R. & KEPE, T. 2017. Elite capture and state neglect: New evidence on South Africa's land reform. Review of African Political Economy, 44(151), pp. 1-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2017.1288615 [ Links ]

HAMMOND-TOOKE, W. 1968. The morphology of Mpondomise descent groups. Journal of the International African Institute, 38(1), pp. 26-6. https://doi.org/10.2307/1157337 [ Links ]

HAWKINS & ASSOCIATES. 1980. The physical and spatial basis for Transkei's first five-year development plan. Planning and Development Planning Consultants. Salisbury: Zimbabwe. [ Links ]

HULL, S., SEHUME, T., SIBIYA, S., SOTHAFILE, L. & WHITTAL, J. 2016. Land allocation, boundary demarcation and tenure security in tribal areas of South Africa. South African Journal of Geomatics, 5(1), pp. 68-81. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajg.v5i1.5 [ Links ]

HUNTER, M. 1936. Relation to conquest: Effects of the contact with Europeans on the Pondo of South Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

JONAS, J. 2019. (Director: Umhlaba Consulting Group). Telephonic interview, Cape Town, 17 September. [ Links ]

KEPE, T. & HALL, R. 2018. Land redistribution in South Africa: Towards decolonization or recolonization? Politikon, 45(1), pp. 128-137. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589346.2018.1418218 [ Links ]

KINGWILL, R. 2008. Custom-building freehold title: The impact of family values on historical ownership in the Eastern Cape. In: Claassens, A. & Cousins, B. (Eds). Land, power and custom: Controversies generated by South Africa's Communal Land Rights Act. Cape Town: UCT Press, pp. 185-207. [ Links ]

KOETZE, C. 2019. (Retired Senior Planning Official, Elundini Local Municipality). Personal interview, Maclear, 8 March. [ Links ]

LAVIGNE DELVILLE, P. 2007. Changes in 'customary' land management institutions: Evidence from West Africa. In: Cotula, L. (Ed.). Changes in 'customary' land tenure systems in Africa. London: IIED, pp. 35-50. [ Links ]

MAGER, A. & VELELO, P. 2018. The house of Tshatshu: Power, politics and chiefs north-west of the Great Kei River. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

MBEMBE, A. 2001. On the postcolony. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [ Links ]

MEINZEN-DICK, R. & MWANGI, E. 2009. Cutting the web of interests: Pitfalls of formalizing property rights. Land Use Policy, 26(1), pp. 36-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2007.06.003 [ Links ]

MNISI WEEKS, S. 2018. The politics of reforming traditional land in South Africa. Africa is a country. 18 December. [Online]. Available at: <https://africasacountry.com>. [Accessed 15 October 2019]. [ Links ]

MOSHOESHOE, M. 2019. (Nkosi). Personal interview, Maclear, 8 March. [ Links ]

MUGHAL, M. 2018. Rural urbanization, land, and agriculture in Pakistan. Asian Geographer, 36(1), pp. 81-91. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10225706.2018.1476255 [ Links ]

NOGCINISA, B. 2019. (Planning Official, Ingquza Hill Local Municipality). Personal interview, Flagstaff, 11 March. [ Links ]

NONKULA, Z. & SKHOSANA, M. 2019. (Community and Economic Development Officials, Elundini Local Municipality). Focus group interview, Maclear, 8 March. [ Links ]

NTINGI, A. 2016. Turning the Eastern Cape around. FinWeek. [Online]. Available at: <https://rn.fin24.com/Finweek/Business-and-economy/turning-the-eastern-cape-around-20161214>. [Accessed: 30 May 2019]. [ Links ]

NTSEBEZA, L. 2008. Chiefs and the ANC in South Africa: The reconstruction of tradition. In: Claassens, A. & Cousins, B. (Eds). Land, power and custom: Controversies generated by South Africa's Communal Land Rights Act. Cape Town: UCT Press, pp. 238-261. [ Links ]

OKOTH-OGENDO, H.W.O. 1989. Some issues of theory in the study of tenure relations in African agriculture. Africa, 59(1), pp. 6-17. https://doi.org/10.2307/1160760 [ Links ]

OKOTH-OGENDO, H.W.O. 2008. The nature of land rights under indigenous law in Africa. In: Claassens, A. & Cousins, B. (Eds). Land, power and custom: Controversies generated by South Africa's Communal Land Rights Act. Cape Town: UCT Press, pp. 95-109. [ Links ]

OOMEN, B. 2005. Chiefs in South Africa: Law, power and culture in the post-apartheid era. New York: Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-06460-8 [ Links ]

PEIRES, J. 1982. The house of Phalo. A history of Xhosa people in the days of their independence. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. [ Links ]

PEIRES, J. 2014. History versus customary law. SA Crime Quarterly, 49, pp. 7-20. https://doi.org/10.4314/sacq.v49i1.1 [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 1996. The Constitution of the Republic of South African. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 1997. White Paper on South African Land Policy. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2000. Municipal Systems Act, Act 32 of 2000. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2003. The Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act, Act 23 of 2009. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2004. The Communal Land Rights Act, Act 11 of 2004. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2013. The Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act, Act 16 of 2013. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2015. The Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act, Act 16 of 2013: Regulations. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

SAKO, S. 2019. (Director: Infrastructure Planning & Development, Elundini Local Municipality) Personal interview, Maclear, 7 March. [ Links ]

SHASHA, Z. 2019. (Director: IPD, Chris Hani District Municipality). Personal interview, Komani, 7 March. [ Links ]

SOGA, J. 2013. The Ama-Xosa: Life and customs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

TAN, C. & DING, Y. 2008. Rural urbanization and urban transformation in Quazhou, Fujian. Anthropologica, 50(2), pp. 215-227. [ Links ]

TOBIA, T. 2019. (Director: Planning & Development, Ingquza Hill Local Municipality). Email correspondence, Cape Town, 18 February. [ Links ]

WATSON, V. 2003. Conflicting rationalities: Implications for planning theory and ethics. Planning Theory & Practice, 4(4), pp. 395-407. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464935032000146318 [ Links ]

WINKLER, T. 2017. The 'radical' practice of teaching, learning, and doing in the informal settlement of Langrug, South Africa. In: Rangan, H., Kam Ng, M., Chase, J. & Porter, L. (Eds). Insurgencies and revolutions: Reflections on John Friedmann's contributions to planning theory and practice. New York: Routledge, pp. 219-228. [ Links ]

WINKLER, T. 2018. Black texts on white paper. Learning to see resistant texts as an approach towards decolonising planning. Planning Theory, 17(4), pp. 588-604. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095217739335 [ Links ]

WINKLER, T. & DUMINY, J. 2016. Planning to change the world? Questioning the normative ethics of planning theories. Planning Theory, 15(2), pp. 111-129. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095214551113 [ Links ]

WOTSHELA, L. 2014. Quitrent tenure and the village system in the former Ciskei region of the Eastern Cape: Implications for contemporary land reform of a century of social change. Journal of Southern African Studies, 40(4), pp. 727-744. [ Links ]

WOTSHELA, L. 2018. Capricious patronage and captive land: A sociopolitical history of resettlement and change in South Africa's Eastern Cape, 1960-2005. Pretoria: Unisa Press. [ Links ]

WOTSHELA, L. 2019. (Professor of History, University of Fort Hare). Personal interview, Alice, 13 March. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2014.931063 [ Links ]

Peer reviewed and revised October 2019

Published December 2019

* The author declared no conflict of interest for this title or article

1 Bennett (2004) is highly critical of the ongoing use of terms such as 'communal land' and 'communal tenure' in contemporary land reform and planning legislation, since such terms are derived from colonial common-law practices that negate existing realities. While I support Bennett's criticism, as it fails to unshackle us from Western conceptualisations of land ownership, for analytical purposes alone, I will continue to use these terms as they refer to a specific type of landholding that is held in trust by the state under the custodianship of traditional leaders. But I will do so by placing these terms in inverted commas to signify their problematic nature.

2 As explained by Hull et al. (2016), rural land administration encompasses four main components, namely the allocation of land parcels to potential rights-holders; demarcating land boundaries; the legal mechanisms used to solve land boundary and land-use conflicts, and establishing land tenure security as a result of the outcomes of the first three components.

3 The system of issuing PTOs is still active in some of South Africa's rural regions, despite being abolished by the state in 1994 (Hull et al., 2016).

4 The Constitution states that existing laws will remain in force until they are replaced by appropriate legislation.

5 CPAs are landholding institutions established under the Communal Property Associations Act of 1996. Beneficiaries of the state's land reform, restitution and redistribution programmes who want to acquire, hold and manage land as a group can establish legal entities, via CPAs, to do so (CLS, 2015).

6 Establishing a uniform system of land rights was also recommended in the 1997 White Paper on Land Policy (RSA, 1997).