Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Town and Regional Planning

On-line version ISSN 2415-0495

Print version ISSN 1012-280X

Town reg. plan. (Online) vol.73 Bloemfontein 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp73.3

ARTICLES

Conceptual commentary of public spaces in Durban, South Africa

Konseptuele kommentaar oor openbare ruimtes in Durban, Suid-Afrika

Tlhatlhobo ya dibaka tsa batho bohle ka tsela ya theori thekong "Durban", Afrika Borwa

Magdalena CloeteI; Salena YusufII

ILecturer: Architecture, School of Built Environment and Development Studies, Howard College Campus, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban. Phone: 031 2601172, 084 4059602, e-mail: <Cloete@ukzn.ac.za>

IIMaster of Architecture student, School of Built Environment and Development Studies, Howard College Campus, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban. Phone: 072 9238445, email: <salenayusuf12@gmail.com>

ABSTRACT

Within the context of African cities that are considered to have poor economic prospects and are failing its inhabitants, this article explores and assesses the quality of Durban's open public spaces through a phenomenological lens, by applying the concept of the sociality of public space and drawing on different theorists' ideas of what constitutes a good open public space. Various factors have led to the corrosion of open public spaces, including modernism and globalisation and their resultant effects as well as spatial apartheid in South Africa. The following theories are used to understand open public spaces: Jacob's "eyes on the street", which supports safer public spaces; Massey's theory of thrown-togetherness, which advocates for a range of different elements present in public spaces, and Parkinson's democracy of public space, which encompasses the way in which people express themselves in public spaces. The research methodology includes a literature review, phenomenological ethnographic observations, mapping, and drawing with written narrative. The spaces considered in the study include a range of Durban's successful and less successful public spaces, including the beachfront, parks, gardens, and a public square. The article concludes that open public spaces are a necessity for quality civic life and are still considered a luxury in Africa.

Keywords: Durban open public spaces, sociality, thrown-togetherness, democracy of space

ABSTRAK

Binne die konteks van Afrika se stede, wat as swak ekonomiese vooruitsigte beskou word, en hulle inwoners faal, ondersoek en evalueer hierdie artikel die kwaliteit van Durban se openbare publieke ruimtes deur 'n fenomenologiese lens en die konsep van die sosialiteit van openbare ruimte deur verskillende teoretici se idees van wat goeie openbare publieke ruimte is, toe te pas. Verskeie faktore het gelei tot die korrosie van openbare publieke ruimtes, insluitend modernisme en globalisering asook die gevolglike effekte daarvan sowel as ruimtelike apartheid in Suid-Afrika. Die volgende teorieë word gebruik om die openbare publieke ruimtes te verstaan: Jane Jacob se "oë op die straat", wat veiliger openbare ruimte ondersteun; Doreen Massey se samesmeltingsteorie, wat voorstellings bied vir 'n verskeidenheid verskillende elemente in die openbare ruimte, en John R Parkinson se demokrasie van openbare ruimte, wat die manier waarop mense hulself in die openbare ruimte uitdruk, insluit. Die navorsingsmetodologie sluit in literatuuroorsig, fenomenologiese etnografiese waarnemings, kartering en tekening met geskrewe vertelling. Die ruimtes wat in die studie oorweeg is, sluit in 'n verskeidenheid van Durban se suksesvolle en minder suksesvolle openbare ruimtes, insluitend die strand, parke, tuine, en 'n openbare plein. Die gevolgtrekking oorweeg openbare publieke ruimtes as 'n noodsaaklikheid vir kwaliteit burgerlike lewe. Dit erken dat oop ruimtes steeds as 'n luukse in Afrika beskou word.

Sleutelwoorde: Durban openbare publieke ruimtes, demokrasie van ruimte, samehorigheid, sosialiteit

TUMELO

Ka hara moelelo wa qotso ya Kihato, pampiri ena e tla lekola le ho lekanyetsa boleng ba dibaka tse bulehileng tsa batho bohle Thekong "Durban", ka ho sheba kgopolotaba ya monate wa dibaka tsa batho bohle ka mehopolo e fapaneng ya bangodi ya hore ke eng se etsang sebaka se bulehileng sa batho bohle e be se lokileng. Mabaka a itseng a teng a entseng hore tshenyeho e be teng ya dibaka tse bulehileng tsa batho bohle. Ka mabitso ke: Ho kopana ha dinaha "Globalisation" le ditlamorao tsa yona, hammoho le kgethollo ya mmala Afrika Borwa. Ditheori tse tla sebediswa ho hlahloba dibaka tse bulehileg tsa batho bohle ke: "Eyes on the street" ya Jane Jacobs, e tshehetsang dibaka tse bolokehileng, "Theory of the throwntogetherness" ya Doreen Massey, e buellang/lwanelang mefutafuta ya dielemente/dikarolo tse teng dibakeng tsa batho bohle le "Democracy of public space" ya John R Parkinson, e kenyelletsang le tsela eo batho ba itlhalosang ka yona dibakeng tsa batho bohle. Dibaka tse hlahlobilweng di tla kenyelletsa bongata ba dibaka tsa batho bohle tsa Thekong "Durban" tse atlehileng le tse sa atlehang hakaalo, ho tloha ho dipaka, mabopo a mawatle, ditshimo/dirapa, sekwere le setediamo se sa dumelleng kgethollo ya mmala. Le hoja ka nako tse ding sebaka sa batho bohle se bulehileng se nkuwa jwalo ka sebaka sa boiketlo Afrika Borwa, sebaka ke tlhokeho e kgolo bakeng sa bophelo ba toropo bo nang le boleng.

1. INTRODUCTION

This article is related to the global concern with the quality of public open space as echoed by UN habitat in their statement that public space is a determinant of the overall quality of cities. "Everything in a city is related to the availability of public space: communication, traffic circulation, space for laying out infrastructure, common services ... Most African cities, for example, are at around 10%, which is clearly not an efficient provision of public space" (Clos, 2016: online).

In contemporary 21st-century cities, as populations experience rapid growth, spaces for the enjoyment of the inhabitants of the city are diminishing and the need for quality open public spaces is becoming more apparent. Modernism has placed a great emphasis on creating the type of city that serves production. This has led to a disconnection between people and their environment. In South Africa, apartheid has exacerbated this disconnection by way of planned spatial segregation. Recent theories of urbanism such as new urbanism indicate that people socialise when living in close proximity to each other. The junction of modernist urban design and apartheid spatial policies had a particularly deleterious impact on interracial socialisation in South African cities.

The degradation of public space in Durban can be ascribed to modernism planning principles, globalisation, and apartheid (Sangmoo, 2015: online). This lack of good public space can stunt a city's economic growth, pollute the environment as well as reduce social stability and security. In fact, quality public spaces should rather be viewed as a basic service such as transport and sanitation. Porada (2013) further suggests that open public spaces can become safe zones of the city where inhabitants can find common ground and economic stresses can go unnoticed. In South Africa, public life has been reduced by the social exclusion of townships and suburbia. However, quality open public spaces can reinforce social inclusion, which, in turn, adds to the growth of public life.

Kihato (2016: online) argues that cities are the lifeblood of economic growth in Africa. She suggests that cities provide the social infrastructure necessary for the inhabitants' living, regardless of the fact that basic services are often lacking. This refers to the unfortunate paradox in which the vast majority of African cities have found themselves, with the city of Durban as a prime example. In a country where 80% of urban areas are informal settlements, public spaces in cities have the unique ability to improve the lives of most of its inhabitants. In Durban, not all open public spaces are well designed; yet they are essential elements of the city. In some ways, the creation of public spaces has been successful in Durban: the Golden Mile is widely regarded as South Africa's most iconic public space. However, there is still room to improve these spaces in order to serve all of society (Open Streets, 2017).

The main aim of this study is to consider open public spaces as providing urban places in the city of Durban, with a specific focus on the sociality of place as a mechanism of place-making and measure of its quality. The study employs a phenomenological ethnographic approach towards understanding the experience of public open spaces in Durban, by means of a literature review of place and the sociality of place as applied to public open spaces. A multiple case study includes recreational and civic public open spaces. These are considered from the authors' perspective, as they are familiar with the spaces as inhabitants of Durban.

The method of observation explores the sociality of public space, as proposed by Jagannath (2018), by applying three urbanism concepts, namely democratic use of public space proposed by Parkinson (2012) and Kahne (2016); thrown-togetherness proposed by Massey (2005), and "eyes on the street" proposed by Jacobs (1961). Drawings and maps are used to illustrate the observations in conjunction with a written narrative considering the concepts mentioned earlier. A young woman and representative of a minority group in South Africa conducted the fieldwork for the study and provided a specific lens to the views.

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK OF PLACE

The architectural theorist Kate Nesbit (1996) argues that the postmodern theoretical theme of place addresses four concepts: man, architecture and nature, place and genius loci, confrontation and dwelling, as well as place and regionalism. Heidegger's statement (as cited in Nesbit, 1995: 48) pre-empts this postmodernist approach as a reaction to modernism: "During the last decades it has become increasingly clear that this pragmatic approach [functionalism] leads to schematic and characterless environments with insufficient possibilities for human dwelling. The problem of meaning in architecture has therefore come to the fore." The theories relating to place in architecture, urban studies as well as in cultural geography and sociology have a common thread in their understanding of the physical environment and how individuals and communities of people relate therewith.

This argument is developed further by incorporating the concepts of both place and dwelling, as presented in the work of Norberg-Schulz (1980; 1985) in his analysis of Heidegger's (1965) Being and time. In this phenomenological approach, architecture serves to develop a sense of place by allowing people to establish an existential foothold or sense of being-in-the-world. This acknowledges that physical environment and people interrelate so as to create identity and meaning, where a sense of place can lead to dwelling or confrontation, and a loss of identity could lead to placelessness. Some of the causes attributed to placelessness are modernism, globalisation, colonialism and, in the context of South Africa, apartheid planning principles.

2.1 Place and placelessness

The rise of globalisation has proceeded hand in hand with the development of modernism. Modernist urban environment can be recognised in the dominance of vehicle-over-pedestrian movement, the separateness of living from working, and the gradual disappearance of natural and human spaces. In short, the occurrence of placelessness rather than a sense of place. Urban theorists such as Lynch (1960), Jacobs (1961), as well as Alexander, Ishikawa and Silverstein (1977) campaigned for urbanism that considers the way in which people experience place both individually and collectively in an attempt to counteract the impact of modernism on the urban environment.

The urban theory of contextualism proposed by Rowe and Koetter (1975) (cited in Nesbit, 2005) refers to more than fitting in, with the notion of collage as a method allowing for a layering of meanings and coexistence of inherently opposite concepts: "order/disorder, simple/ complex, private/public, innovation/ tradition". The architectural and urban design approaches of contextualism are inherently aimed at creating place and meaning within the urban environment.

2.2 Perception

Further theories relating to meaning in the urban environment are based strongly on perception and gestalt theory. Lynch (1960: 47-48) argues that "meaning is located in the distinctiveness of path, edge, node, district, and landmark". This argument is directed at creating place within the city. The concept of place-making in urban design, as originated by Lynch, has more recently been developed into specific strategies to respond to the issues of urbanisation and placelessness that can be associated with contemporary cities.

Similarly, Rasmussen's (1959) views that design of the built environment needs to be rooted in the experiences of the user and not merely viewed as a functional or sculptural object. He describes "architecture as a visual, auditory, tactile, and above all psychological art", manifested in light, colour, rhythm, texture, and material (Mallgrave & Constandriopoulos, 2008). His view is in line with more recent studies that consider architecture as a complete body experience that includes all the senses (Menin, 2003; Pallasmaa, 2005). These concepts relating to architecture are also appropriate when considering meaning in the urban environment and public open spaces. Hertzberger (1991) concluded that every act of making architecture has an impact on people, in this instance, referring to the interrelation between people and the built environment.

2.3 Meaning

Rapoport (1982) distinguishes between perception and meaning associated with the built environment. He concludes that place is space plus something, but disregards the notion of place, due to the difficulty in defining the 'something'. Menin (2003) constructs a strong counterargument in defining that meaning is established through the construction of place and that environment without meaning is definable as placelessness. Menin (2003) also draws a parallel between place and aesthetics, which allows for a deeper understanding of its meaning. This phenomenological approach is supported by what Heidegger (1965) termed 'dwelling' and describes how people find meaning in the world: "Man dwells when he can orientate himself within and identify himself with an environment, in other words, when he experiences the environment as meaningful. Dwelling therefore implies something more than "shelter". It implies that the spaces where life occurs are places ... A place is a space which has a distinct character." (Norberg-Schulz, 1980: 5).

2.4 Dwelling

Norberg-Schulz's (1980) argument about meaning, genius loci, place and dwelling, rooted in the work of Heidegger (1965), developed a theory that supports the notion of architecture, with a purpose to help people dwell. The notion of dwelling can thus be translated as the process of defining our 'being-in-the-world', by providing a built environment that is responsive to people and its context.

The four modes of dwelling defined by Norberg-Schulz (1985) are relevant, as they relate to different levels of human habitation and indicate the full spectrum of architecture. First, settlement or natural dwelling takes place; secondly, urban spaces are a place of encounter, a connector, collective dwelling of gathering and assembly; thirdly, institutions or public buildings or dwellings where patterns of agreements, commonality of interests or values are developed as the basis of fellowship and society, and, lastly, the private dwelling, house or home, with one common denominator: language.

2.5 Place-making

Hertzberger (1991) argues that the role of the architect is to provide a spatial framework which then allows the user to complete it. This notion relates to Menin (2003) and Unwin (2009) who suggest that the process of making place includes the everyday. The processes of making place in informal settlements, as developed by the user, are often in line with the natural progression of life (birth, childhood, household formation, death, separation). The emphasis of process connects memory with meaning (Menin, 2003: 92). "Such informal place-making processes are powerful testimony to the extraordinary power and creative talent of those usually considered ordinary" (Menin, 2003: 97).

2.6 Urban place-making

Soja (2000) identified the issues of context that were internationalised by globalisation and capitalism, in terms of which global values prevail over local spatial characteristics. Modernist planning principles and urban sprawl lead to cities that shut down and empty after working hours, as they have become a place of high production and not for socialising and relaxing. This decline in urban vitality is also partially attributed to the lack of a sense of place in open public spaces.

Throughout history, a public space has served as this collector and connector within communities. Amin (2006: online) argues that public spaces support and build a sense of community, civic identity and culture as well as promote relaxation and wellbeing.

2.7 The sociality of public space

The concept of sociality of space can be defined as a measure of the sense of place in an urban environment. Sociality refers to how people feel about a particular space. In other words, their experience of the sense of place collectively. Jagannath (2018) argues that, when people feel a sense of inclusion towards a space, they tend to use the space for a longer period of time and frequent it more often. Three theories that seem appropriate to the globalised, modernist, postapartheid context of Durban are used to explore the concept of sociality for public spaces. These theories include the democratic use of public space; the use for a 'thrown-togetherness' of different elements; eyes on the street, which includes security and vibrancy of public space, as well as the importance of sensory experience of public spaces (Jagannath, 2018).

2.7.1 Democratic use of public space

Democracy of public space includes the different ways in which people express themselves in public spaces. In Democracy and public space, Parkinson (2012) argues that, even in our digital world ruled by social media, democracy depends, to a large extent, on the availability of physical public space. Change can take place when the public space is used for strong protests (Kahne, 2016). Public special arrangements can either build a sense of 'we' in society, or they can undermine it.

The following aspects need to be considered when evaluating the democracy of space: accessibility of the space - can citizens get to the space quickly, easily and cheaply; size of the space - larger spaces are better for the gathering of people; character of the space - public spaces should be fluid and adaptable with a range of ongoing activities, and security -do people feel safe in the space (Kahne, 2016). The layout of Beijing universities had the ability to facilitate the Tiananmen student protests facilitated communication among the activists and built a collective identity. Conversely, in Minneapolis, the elevated, covered walkways between the buildings reinforced the divisions between the haves (office dwelling) and the have nots (street level) (Parkinson, 2012: 5). In the South African context, where public protests are considered an important means of voice to marginalised inhabitants, this democratic theoretical lens is important to urban place-making.

2.7.2 Thrown-togetherness

The thrown-togetherness of space constitutes the character of the public space, the people surrounding it, and the physical structures present in the space such as art or fountains, including traffic noise. All these factors can impact on the way in which the space is used and understood. Massey (2005) explains that thrown-togetherness suggests that the various elements and structures present in the public space, including the way in which the space is built, have an impact on how people use it (Jagganath, 2018).

Thrown-togetherness occurs when a range of different elements in the public space contribute to how people feel in the space, in particular if they feel included and have a sense of belonging in the space. Surrounding places such as cafes, art galleries, museums, and theatres can also contribute to making the space more inclusive and welcoming to the public. Obtaining a sense of urban multiplicity is also important. The interpretation refers to the sense of place in the urban environment that could allow for collective dwelling. This theory can be recognised as an important aspect of place-making in the urban environment.

2.7.3 Eyes on the street

Jacobs' (1961) theory of eyes on the street is crucial to Durban, because it speaks to the fear of crime of the vast majority of South Africans. Jacobs advocates that good design can enhance or corrode a person's sense of safety. Designers consider green spaces such as parks to be a necessity for built-up city areas. However, if not designed correctly, parks can be dangerous and volatile places. Open public spaces are successful when they encourage a range of activities and land uses as well as a diversity of users. Eyes on the street are established by places such as stores, restaurants, street vendors and pedestrians. Instead of using technology such as surveillance cameras to protect people, the presence of people should be encouraged (Gerda, 2000: 45-48).

Jacobs' (1961) theory was a direct response to the impact of modernist planning principles in America. Over the past decades, the relevance of the observations and considerations has been found applicable in an attempt to counter the placelessness resulting from globalisation. The more recent arguments by Gehl in the walkable city echo this concern about creating a sense of place in the urban environment.

3. PLACE IN THE CONTEXT OF GREATER DURBAN

Urban expansion, increase in population as well as the extension of the built environment from the city centre often lead to "the destruction of the environment and the inner [Durban] city deterioration" (Allopi & Yusuf, 2010: 520).

Like the rest of the world, Durban's built environment has slowly developed, adapted and changed to suit the needs of the population. The growth of Durban's built environment was influenced by population growth and the development in technology driven by social/economic growth.

Durban was founded in the 1800s as a port, due to the ideal location of a protected bay. The trading port was established on the northern shore of the bay as a settlement in 1824 (Mkhize, 2015). The growth and urbanisation of Durban city centre was the result of industrialisation, when the city centre became the node for employment, activity, and wealth (Yusuf & Allopi, 2004).

The legacy of apartheid planning in South Africa, combined with urbanisation, resulted in unique problems regarding open public spaces. Apartheid denied large groups of citizens their right to quality public spaces. This affected the majority of non-White South Africans in the country. Spatial segregation further ensured discriminatory access to the city centres and certain areas of the city such as beaches. As a result, townships began to spring up all over the country, but quality public space was assigned a minimal role in these areas, or were all but neglected (Safer Spaces, 2018: online).

The effects of spatial apartheid are still widely evident in South Africa's cities. As a result, the "public space deficit" mainly affects the lower income neighbourhoods, many of which are still segregated along class and racial lines (Safer Spaces, 2018: online). Nowadays, the city of Durban needs quality open public spaces that accommodate all its inhabitants. These spaces should allow for people and communities of different backgrounds to interact. However, there has generally been a lack of these public spaces.

If one considers the past 20 years of democracy, many parks and other open public spaces have been neglected over time. This is mainly due to the general South African perspective that open public spaces are not safe. Instead of being able to relax and enjoy Durban's beautiful outdoor spaces, malls have now become the main public spaces where people gather and meet (Safer Spaces, 2018: online). The privatisation of public space has magnified the lack of quality public open spaces.

4. CASE STUDY: GREATER DURBAN OPEN PUBLIC SPACES

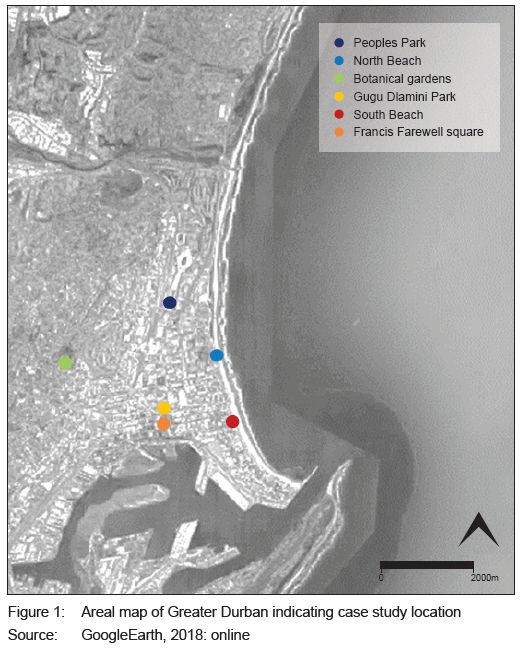

The open public spaces in the city of Durban include recreational, civic and sporting spaces. Figure 1 shows the spaces considered in the study. These include a range of Durban's successful and less successful public spaces.

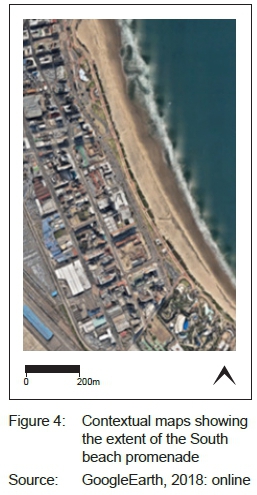

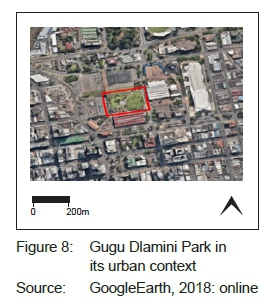

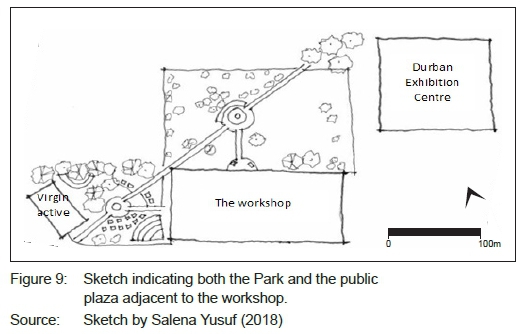

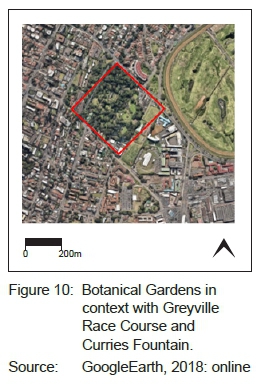

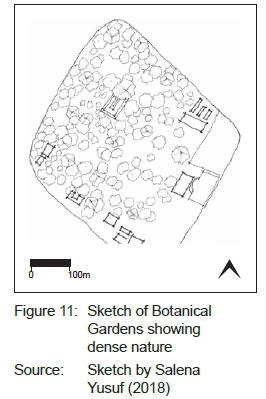

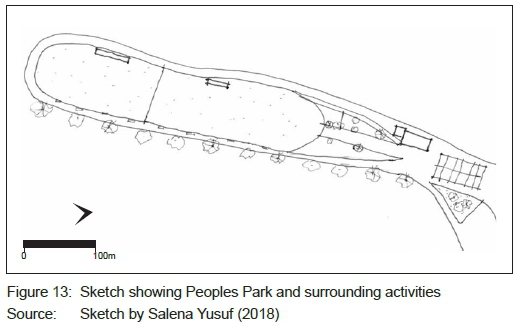

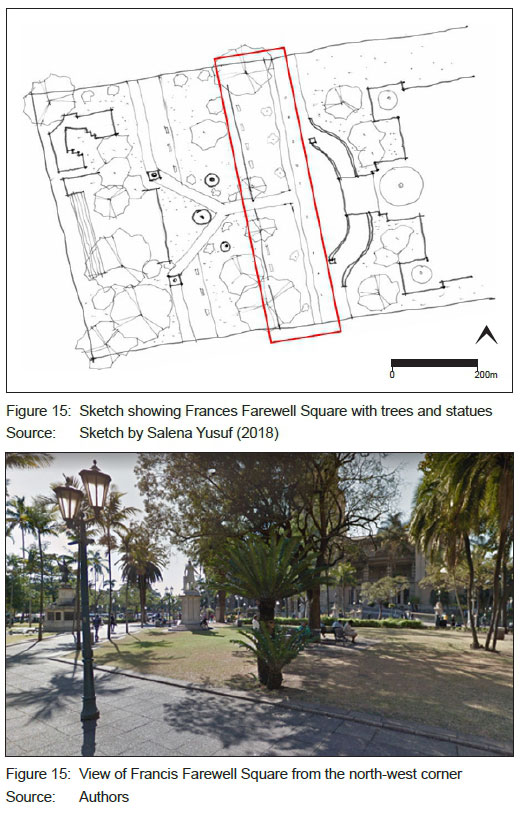

Each of the open public spaces is shown on a contextual map taken from GoogleEarth to provide the urban surrounding context. A hand sketch is then introduced to provide a more detailed understanding of the space. A consistency in the scale of the contextual map and the hand sketch provide the case study with some comparison in terms of size and form.

The case study would have benefited from the addition of sections through each of the spaces as well as more sketches to illustrate the experience of a sense of place.

4.1 Beaches

"The beachfront is not just the most important asset in our tourism industry. It is also one of the only spaces in our country where South Africans of all colours and classes can come together to enjoy our country together. The social value of this is invaluable" (Buccus, 2017: online).

Many view Durban's Golden Mile as the most successful open public space in the city (Open Streets, 2017).

There is an improved sense of safety along the North beach stretch of the Golden Mile. The mix of cafés, restaurants, joggers and beachgoers all add to the sense of safety. This is especially so at sunrise and sunset as well as during the weekend when the beachfront is the busiest. This area is the most successful example of Jacob's eyes on the street.

Despite the success of the 2010 revamp of the Golden Mile, some people are still concerned about crime and security (Comins & Van Dyk, 2011). Certain stretches of the beach are still considered more unsafe than others, due to the lack of activities in these areas. Some individuals mention that the beach activities that were active during the Fifa World Cup should have been retained so as to enliven the quieter spaces. This is specifically evident between Ushaka Marine World and the Wimpy restaurant at North beach; this stretch particularly lacks activities. The area known as South beach provides a strong juxtaposition to the lively atmosphere of the North beach area. In this area, the derelict buildings and proximity to Durban's notorious Point area create a drastically more unsafe atmosphere.

The Golden Mile and the North beach area, in particular, are an impressive example of Massey's (2005) theory of thrown-togetherness. In this space, many people from different countries, cultural backgrounds, races and classes integrate well. This is in contrast to the restrictive nature of Umhlanga beachfront. Sociality of space advocates for social inclusion, but Umhlanga beachfront is perceived as an exclusive space (Comins & Van Dyk, 2001), catering primarily to the haves in society. The Golden Mile is a welcoming public space and is well supported by a wide range of activities, including swimming pools, amusement park rides at fun world, cycling, jogging, a skate park, and various dining options, catering to all budgets and cultures. This gamut of activities attracts a diverse range of people. This effect was amplified during the 2010 Fifa World Cup, when the beachfront became a social hub of activity. At that time, the shared sense of place and social inclusivity was most tangible.

On 7 April 2017, the Durban beachfront up to the amphitheatre was turned into an area of mass protest. The agenda was the people's march, demanding former President Zuma to step down (Kubheka, 2017). The Durban beachfront serves as a democratic space, due to its central location accessibility. Accessibility is supported by bus and taxi routes. It has a range of ongoing activities contributing to it being regarded as a safe space. The beachfront is a large non-obtrusive open space that can cater to many people. While it might not be the first choice for demonstrators, all these factors support the notion that North beach is a competent democratic space for the people of the city.

Over time, the Golden Mile has undergone a positive transformation, mostly due to the effects of the 2010 Fifa World Cup, which has made the area a much more inviting public space. Although it remains an imperfect representation of sociality of public space, it is far better than some of Durban's other beaches. Glen Ashley beach, for instance, close to Virginia airport, is an isolated beach. The lack of supporting activities contributes to the lack of eyes on the street, which can create an uneasy feeling for many. Its desolate nature makes it an unpopular choice with beachgoers.

4.2 Parks

4.2.1 Gugu Dlamini Park

One of the best public spaces in the CBD is Gugu Dlamini Park, which acts as a kind of welcoming oasis juxtaposed with the busyness of the CBD. It is a celebrated example of thrown-togetherness, as it showcases traditional dancing, caters to karate lessons as well as ordinary Durbanites reading or simply relaxing on the grass.

The Park was named after Gugu Dlamini, a woman who was brutally murdered for revealing her HIVpositive status at a time when HIV and AIDS was shrouded in ignorance. Nowadays, a large red ribbon installation pays tribute to her bravery (DUT, 2013). In terms of thrown-togetherness, the presence of this ribbon acts as a source of engagement and causes people to reflect about its meaning, especially given the epidemic proportions of HIV and AIDS prevalence in South Africa. It adds a great deal of meaning to the space and can instil a sense of tolerance. As a result, it can assist in breaking down social stigmas.

Gugu Dlamini Park was not always such a safe space. Recently, lights have been installed in the Park and an ongoing police presence adds a sense of security (DUT, 2013). Its close proximity to the workshop and the informal stalls that surround it also add to the vibrancy of the Park, making it a capable example of Jacob's eyes on the street. Walking through Gugu Dlamini Park during the day, one feels a combination of respite as well as a sense of liveliness that is often associated with CBDs. However, a consequence of being in the CBD means that the character of the space changes at night as the city empties.

4.2.2 Botanical Gardens

The Durban Botanic Gardens, located in Greyville, was established in 1849, in close proximity to Greyville race course and the Curries Fountain Sports Development Centre. It is Durban's oldest public institution and Africa's oldest surviving botanical gardens. The members of the Natal Agriculture and Horticultural Society decided to found a botanical garden as part of the newly re-established Kew Gardens in England (Khan, 2017). Kew Gardens aimed to establish a series of botanical gardens across the globe that would assist in the introduction of plants of possible value. The site originally selected for Durban's Botanic Gardens was the flat land at the end of Berea Ridge beside the Umgeni River. However, in 1851, the Gardens were moved closer to town and the 35 acres were increased to 50 (Khan, 2017).

One of the flaws of Durban's Botanical Gardens is its lack of diverse activities; the Park has only one small café. Large trees and dense brush are what makes the Park beautiful, but it also isolates parts of the Park and creates an unsafe feeling. This is not helped by the fact that the Park is sloping. These isolated pockets of space and lack of activities do not tie up well with eyes on the street. However, the Park hosts many concerts, making the area livelier. Stalls selling food and drinks as well as musicians and performers make the space more vibrant. This, in turn, enhances the sense of safety in the space. The Gardens truly come alive whenever these concerts take place. However, if one visits during a weekday, the space has a reflective stillness about it.

The Botanical Gardens has some of the elements of thrown-togetherness such as sculptures, flower gardens and descriptions of the vegetation that make people stop and linger at certain areas. However, it is perhaps not as successful in terms of security. The Gardens attract a multitude of people to relax or explore the Park and to learn about different species of plants, but some areas of the Gardens can feel fairly isolated and unsafe.

4.2.3 People's Park

People's Park, established in 2009, is located in the Durban beachfront area, adjacent to the iconic Moses Mabhiba Stadium. It is a relatively new, but important contribution to Durban's open public spaces.

People's Park is another example of thrown-togetherness. The Park has a host of different activities that cater to all age groups; it contains a track and field area, an ultra-modern kids' playground, and a café overlooking these areas. On one side of the track is a grassy area that is shaded by pergolas and trees where parents tend to congregate. It also acts as a picnic area. There are also benches alongside the running track for people to relax. Peoples Park also benefits from all the activities from Moses Mabhiba Stadium and is well connected by walkways as well as visual access. These activities include bike and Segway hire, the skywalk, fountains as well as more restaurants. At night, the Park takes on a different character, as it often hosts music festivals and shows of Moses Mabhida. The Stadium is an iconic building in Durban and is frequented by many Durbanites as well as tourists. As the stadium was constructed specifically for the 2010 Fifa World Cup, it was feared that it would become desolate once the event was over. However, People's Park provides a space that is accessible to anyone in the city and caters to diversity, thus making it so successful.

In terms of Jacobs' (1961) theory of eyes on the street, People's Park succeeds well. It can contain children in a way that feels safe for parents. The vibrant surrounding activities all act as eyes on the street. This is also helped by the fact that the Park does not have many tall, visually obstructive trees, but this can be viewed as positive or negative, depending on whom you ask. The flat undulating surface also ensures good visual connection between people. The café, running track and adjacent Moses Mabhiba Stadium all make the Park a vibrant place that is well used by the public, especially at weekends, and acts as more pairs of eyes on the street.

Although the Park has the potential for public protest, due to its location and open space, it might not make a very good democratic space, due to its relatively small size for mass gatherings.

By contrast, many parks in Glenwood are overgrown, unsafe spaces that are lacking in activities.

4.2.4 Francis Farewell Square

Durban's City Hall provides an important public space for the arts and education. It houses the Durban Art gallery, the City Library and the Natural Science Museum which cater to both Durbanites and visitors. However, people gather in Francis Farewell Square, outside City Hall, to make their point heard (Ethekwini Municipality, 2001). It provides arguably the most important and commonly used democratic public space in Durban. The Square was named after Lieutenant Francis Farewell who was fundamental in the decision to establish a trading post in the Port of Natal and was able to convince other White settlers to join him (Ethekwini Municipality, 2001).

The City Hall is centrally located, making it quick, easy and cost effective to access using public transport. The paved space directly in front of the City Hall is open and transparent, allowing easy access for protestors to communicate. However, the statues on the Square, although not too obtrusive, may provide a visual barrier and divide the protestors. One of the major downfalls of the Square is that it is comparatively small in size and cannot support large masses of voters like other more successful public squares internationally.

Francis Farewell Square is a relaxing and quiet space, but it does not support Massey's theory of thrown-togetherness. In support of this theory, the statues provide a source of contemplation for visitors and there are benches and areas for seating. The Square lacks a sense of vibrancy. There are not many supporting activities leading onto the Square besides the activities of the City Hall. This is contrary to Trafalgar Square in London, which hosts public artworks that give the space a purpose. Amin (2006: online) mentions a "situated multiplicity" that constitutes the "mingling of bodies, human and non-human, in close physical proximity". In Trafalgar Square, the fourth plinth is the centre of attraction for public art displays. This space provides a human sculpture platform where approximately 2000 people are chosen to enact their moment of fame in any way they wish for one hour.

There may be a lack of supporting activities in Francis Farewell Square, but this is improved by the fact that it is located in a busy part of the CBD. The people walking around and through the square add to the eyes on the street. The Square is fairly open and visible from the adjacent streets. Like Gugu Dlamini Park, this space might not be as safe in the evening, as people start leaving the CBD for their homes. The lack of surrounding social activities makes the Square an unsafe place. Trafalgar Square is safe and vibrant; people can sit and walk in the Square. It has regular events or activities for people to interact with strangers on a regular basis. Trafalgar Square's mix of uses and pedestrian activity create vibrancy. There is a sense of security as well as comfort and attraction to sit in a public space surrounded by other people, even strangers (Gehl, 2010; Jacobs, 1961). Gehl (2010: 148) calls this "attractions on a pedestrianised street", even though the entire Square is not pedestrianised.

5. CONCLUSION

Open public spaces in Durban range from successful, well-used spaces to areas that have become dangerous, lost and wasted space. Even though some might not consider well-designed public spaces essential, especially in the context of African cities, the creation of these spaces is paramount to the well-being of society. They contribute toward civic pride and identity, and they enhance the overall 'liveability' of a city. Some of the best examples of sociality of public spaces are Durban's Golden Mile and People's Park. However, other spaces such as the overgrown parks of Glenwood are a hazard to public safety, due to the overgrown vegetation and lack of eyes on the street, whereas some spaces such as Umhlanga beachfront have an exclusive nature. This study also highlighted Durban's lack of open public spaces that can be used at night, apart from Florida Road and Umhlanga beachfront; even the Golden Mile is not so safe during the night, unless a specific activity is planned. One can learn much from the positive elements of the Golden Mile and these elements can be interpreted when uplifting Durban's open public spaces. The city of Durban can then truly live up to its title of being South Africa's most liveable city, by providing safe and effective spaces that contribute positively to civic life.

REFERENCES

ALEXANDER, C., ISHIKAWA, S. & SILVERSTEIN, M. 1977. A pattern language: Towns, buildings, construction. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

ALLOPI, D. & YUSUF, M.P. 2010. The impact of urban sprawl on the inhabitants of the Ethekwini Municipality and the provision of infrastructure. In: Proceedings of the 29thSouthern African Transport Conference, 16-19 August 2010, "Walk Together", CSIR International Convention Centre, Pretoria, South Africa. Pretoria: Document Transformation Technologies cc, pp. 415-424. [ Links ]

AMIN, A. 2006. Collective culture and urban public spaces. [online]. Available at: <http://www.publicspace.org/en/text-library/eng/b003-collectiveculture-and-urban-public-space> [Accessed: 17 April 2015]. [ Links ]

BUCCUS, I. 2017. Beachfront - a triumph of urban development. [online]. Available at: <https://www.iol.co.za/news/opinion/beachfront-a-triumph-of-urban-development-7409895> [Accessed: 20 March 2018]. [ Links ]

CLOS, J. 2016. We have lost the science of building cities. Interview in The Guardian, 18 April 2016. [online]. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/apr/18/lost-science-building-cities-joan-clos-un-habitat> [Accessed: 2 November 2018]. [ Links ]

COMINS, L. & VAN DYK, J. 2011. Golden smiles ... and frowns. [online]. Available at: <https://www.iol.co.za/travel/south-africa/kwazulu-natal/golden-smiles-and-frowns-1111979> [Accessed: 27 March 2018]. [ Links ]

DURBAN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY (DUT). 2013. Exploring Durban: Gugu Dlamini Park. [online]. Available at: <http://journalismiziko.dut.ac.za/feature-review/exploring-durban-gugu-dlamini-park/> [Accessed: 29 March 2018]. [ Links ]

ENCA.COM. Marches at North Beach Amphitheatre. [online]. Available at: <http://www.enca.com/south-africa/hordes-of-protestors-occupy-durban-beachfront.html.> [Accessed: 2 November 2018]. [ Links ]

ETHEKWINI MUNICIPALITY 2001. City Hall/Francis Farewell Square. [online]. Available at: <http://www.durban.gov.za/Resource_Centre/new2/Pages/City-Hall-Centenary.aspx> [Accessed: 26 March 2018]. [ Links ]

GEHL, J. 2010. Cities for people. Washington, DC: Island Press. [ Links ]

GERDA, W. 2000. From eyes on the street to safe cities [Speaking of places]. Places, 13(1), pp. 44-48. [ Links ]

GOOGLE-EARTH. 2018. [online]. Available at: <http://www.southafrica-maps.com/3DEarth> [Accessed: 2 November 2018]. [ Links ]

HEIDEGGER, M. 1965. Being and time. USA, NY: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

HERTZBERGER, H. 1991. Lessons for students in Architecture. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers. [ Links ]

JACOBS, J. 1961. The death and life of great American cities. New York: Vintage Books. [ Links ]

JAGANNATH, T. 2018. Theories on public spaces: A case study of Trafalgar Square. [online]. Available at: <https://medium.com/@thejas009/theories-on-public-spaces-a-case-study-of-trafalgar-square-de868550ad71> [Accessed: 6 March 2018]. [ Links ]

KHAN, S. 2017. A brief history of Durban's Botanic Gardens. [online]. Available at: <https://theculturetrip.com/africa/south-africa/articles/a-brief-history-of-durbans-botanic-gardens/> [Accessed: 2 June 2018]. [ Links ]

KAHNE, J. 2016. "Whose streets, our streets": Democracy still lives in public spaces. [online]. Available at: <https://www.pps.org/article/democracy-still-lives-in-public-spaces> [Accessed: 29 March 2018]. [ Links ]

KIHATO, C. 2016. Africa's urban paradox: Mobilities, economies and aspirations. Southern African City Studies Conference 2016 Abstract Guide. [online]. Available at: <http://www.dut.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Abstract-Guide-Final.pdf> [Accessed: 5 March 2018]. [ Links ]

KUBHEKA, A. 2017. DA-led people's march in Durban. [online]. Available at: <https://www.ecr.co.za/news/news/watch-supporters-gather-in-durban-ahead-of-peoplesmarch/> [Accessed: 28 March 2018]. [ Links ]

LYNCH, K. 1960. The image of the city. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [ Links ]

MALLGRAVE, H.F. & CONSTANDRIOPOULOS, C. 2008. Architectural theory: Volume II An anthology from 1871 to 2005. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

MASSEY, D. 2005. For space. London: Sage. [ Links ]

MENIN, S. 2003. Constructing place: Mind and matter. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

MKHIZE, O. 2015. Urban wellness public facilities: On the Durban beachfront. Unpublished Master's) thesis, Department of Architecture, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

NESBIT, K. 1996. Theorizing a new agenda for architecture: An anthology of architectural theory 1965-1995. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. [ Links ]

NORBERG-SCHULZ, C. 1980. Genius loci: Towards a phenomenology of architecture. London: Studio Vista. [ Links ]

NORBERG-SCHULZ, C. 1985. Concept of dwelling: On the way to figurative architecture. New York: Electa/Rizzoli. [ Links ]

OPEN STREETS, 2017. Successful public spaces in South Africa. [online]. Available at: <From https://openstreets.org.za/news/successful-public-spaces-south-africa> [ Accessed 16 March 2018]. [ Links ]

PALLASMAA, J. 2005. The eyes of the skin: Architecture and the senses. Chichester: Wiley-Academy. [ Links ]

PARKINSON, J.R. 2012. Democracy and public space, the psychical sites of democratic performance. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199214563.001.0001 [ Links ]

PORADA, B. 2013. Ten ways to transform cities through placemaking and public spaces. ArchDaily [online]. Available at: <http://www.archdaily.com/362988/ten-ways-to-transform-cities-through-placemaking-and-public-spaces> [Accessed: 8 September 2015]. [ Links ]

RAPOPORT, A. 1982. The meaning of the built environment: A nonverbal communication approach. London: Sage. [ Links ]

RASMUSSEN, S.E. 1959. Experiencing architecture. London: Chapman & Hall Ltd. [ Links ]

ROWE, C. & KOETTER, F. 1975. Collage city. The Architectural Review, 158(941), pp. 66-94. [ Links ]

SAFER SPACES. 2018. Public spaces: More than 'just space'. [online]. Available at: <http://www.saferspaces.org.za/understand/entry/public-spaces> [Accessed: 15 March 2018]. [ Links ]

SANGMOO, K. 2015. Public spaces - not a "nice to have" but a basic need for cities. [online]. Available at: <http://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/public-spaces-not-nice-have-basic-need-cities> [Accessed: 20 March 2018]. [ Links ]

SOJA, E. 2000. Postmetropolis: Critical studies of cities and regions. New York: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

TRIPADVISOR.COM. Durban's Golden Mile. [online]. Available at: <http://www.tripadvisor.ie/LocationPhotoDirectLink-g312595-d305786-i65650043-Gooderson_Beach_Hotel-Durban_KwaZulu_Natal.html> [Accessed: 2 November 2018]. [ Links ]

UNWIN, S. 2009. Analysing architecture. 3rd edition. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203880906 [ Links ]

Reviewed November 2018

Revised November 2018

The authors declared no conflict of interest for this title or article