Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Town and Regional Planning

On-line version ISSN 2415-0495

Print version ISSN 1012-280X

Town reg. plan. (Online) vol.72 Bloemfontein 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp72i1.6

ARTICLES

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp72i1.6

The generation of competencies and standards for planning in South Africa: Differing views

Die skepping van bevoegdhede en standaarde vir beplanning in Suid-Afrika: Verskillende opinies

Setjhaba se nang le bokgoni le maemo bakeng sa thero/tokisetso Afrika Borwa: Mehopolo e sa tshwaneng

Mfaniseni Fana Sihlongonyane

School of Architecture and Planning, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. Phone: 0117177706, e-mail: <Mfaniseni.sihlongonyane@wits.ac.za>

ABSTRACT

Since the founding of planning in South Africa fifty-two years ago, the statutory bodies governing the profession have not set the competencies and standards in order to create a framework for curriculum development, the accreditation of schools, as well as the registration of planners and their professional practice. In 2010, the South African Council for Planners, a statutory body responsible for the regulation and quality assurance of the planning profession, initiated a process of generating Competencies and Standards to deal with the many challenges that had arisen as a result of the lack of the framework. The generation of a set of Competencies and Standards has stimulated much debate in the corridors of higher learning and between the Council and other related professional bodies in the built environment. This article first traces the motivating factors for the initiation of the Competencies and Standards process; secondly, it examines the history of this process; thirdly, it discusses the debatable issues raised in the various interactive workshops during the process. And lastly, it identifies the achievements of the process. The thrust of argument in the article is that the Competencies and Standards process marks a significant step towards curriculum reform, but more engagement will be required to facilitate transformation in the planning profession.

Keywords: Competencies and standards, professional planning development, planning education and transformation, SACPLAN

ABSTRAKTE

Sedert die ontstaan van beplanning in Suid-Afrika twee en vyftig jaar gelede, het die statutêre liggame wat die professie bestuur, nie die bevoegdhede en standaarde gestel om 'n raamwerk vir kurrikulumontwikkeling, die akkreditering van skole, en die registrasie van beplanners en hul professionele praktyk te skep nie. In 2010 het die Suid-Afrikaanse Raad vir Beplanners, 'n statutêre liggaam wat verantwoordelik is vir die regulering en gehalteversekering van die beplanningsprofessie, 'n proses voorgestel om vaardighede en standaarde te genereer om die vele uitdagings wat ontstaan het as gevolg van die gebrek aan 'n raamwerk, aan te spreek. Die skep van 'n stel vaardighede en standaarde het baie debat in die gange van hoër onderwys en tussen die Raad en ander verwante professionele liggame in die beboude omgewing gestimuleer. Hierdie artikel verduidelik eerstens die motiverende faktore vir die inisiëring van die Bevoegdhede en Standaarde-proses. Tweedens, vertel dit die geskiedenis van hierdie proses. Derdens word die debatbare kwessies wat gedurende die proses tydens die verskillende interaktiewe werkswinkels geopper is, weergegee. Ten slotte identifiseer dit die prestasies van die proses. Die argument in die artikel is dat die Bevoegdhede en Standaarde-proses 'n belangrike stap in die rigting van kurrikulumhervorming is, maar meer betrokkenheid sal nodig wees om transformasie in die beplanningsprofessie te fasiliteer.

Sleutelwoorde: Beplanningsonderwys en transformasie, vaardighede en standaarde, professionele beplanningsontwikkeling, SACPLAN

TUMELO

Ho tloha qalehong ya thero/tokisetso Afrika Borwa dilemong tsa mashome a mahlano a nang le metso e mmedi tse fetileng, mekgahlelo e molaong e etelletseng mosebetsi oo pele ha e soka e beya bokgoni le maemo, bakeng sa ho etsa moralo wa kgolo ya thuto; tumello ya dikolo, boingodiso ba bahlophisi le tshebetso ya profeshenale. Ka 2010, South African Council of Planners, eo e leng mokgatlo o molaong; bakeng sa tsamaiso le netefaletso ya boleng ba profeshene ya thero/tokisetso; e qadile tsamaiso ya ho hlahisa bokgoni le maemo bakeng sa ho tobana le diphepetso tse ngata tse ileng tsa hlaha ka lebaka la tlhokeho ya moralo wa tshebetso. Setjhaba sa sete/se ipopileng ka Bokgoni le Maemo se susumeleditse dipuisano tse ngata diphatjheseng/dibakeng tsa thuto e phahameng le mahareng a lekgotla le mekgatlo e meng ya profeshenale tikolohong e ahilweng. Pele, atikele ena e sheba dintlha tse entseng qaleho ya tsamaiso ya Bokgoni le Maemo. Sa bobedi, e sheba nalane/histori ya tsamaiso. Sa boraro, e bua ka mathata a ka kgonang ho sekasekwa boitjhorisong ba mekgahlelo e fapaneng; nakong ya tsamaiso. Ya ho qetela, e tsebahatsa dikatleho tsa tsamaiso. Tabakgolo ya dipuisano atikeleng ena ke hore tsamaiso ya Bokgoni le Maemo e bontsha kgato ya bohlokwa ho ya phethohong ya thuto, empa kopano e tla hlokahala bakeng sa ho thusa/tlisa diphetoho profesheneng ya thero/tokisetso.

1. INTRODUCTION

Imperialism leaves behind germs of rot which we must clinically detect and remove from our land but from our minds as well (Fanon, 1965: 36).

In every era the attempt must be made to wrest tradition away from a conformist that is about to overpower it (Benjamin, 1969: 255).

There can be no transformation of the curriculum, or indeed of knowledge itself, without an interrogation of the archive (Ndebele, 2000: online).

These three quotations highlight the pressing need to wrestle with our knowledge traditions in order to transform the planning profession from time to time. Between 2010 and 2014, the South African Council for Planners (SACPLAN) embarked on an arduous journey of generating Competencies and Standards (C&S) for the Planning profession.1 A team of facilitators was appointed to undertake the exercise. The facilitators consisted of two academics who had a wide and deep experience in teaching and practice in the planning profession. The facilitators managed to develop a framework for the C&S towards reaffirming the professional status of planning in the built environment. The engagements with the stakeholders in different workshops around the country, however, revealed many challenges militating against transformation in the profession. Some of the challenges have a long and deep history going back to the founding of planning in the country.

This article is based on a collection of materials from various consultative workshops held around the country during the process of developing the C&S (see Table 1). Some of the material is drawn from public reports written by the facilitators for the Council and from comments made by various stakeholders that are in the public domain. Some of the information is drawn from newsletters, newspapers and informal discussions as well as personal observations. The author was a council member and was personally involved in the C&S generation project. Therefore, the narrative is inevitably subjective to a degree. The approach of the article is historical, reflective and analytical; however, it does not identify subjects of opinion makers, unless they spoke in an official capacity.

The article addresses the following questions:

• What are the motivating factors to the initiation of the C&S process in the planning profession?

• What are the issues of concern for planners in the country?

• What is the impact of the C&S project?

The article starts by reflecting on the motivating factors for the development of C&S. It identifies the general steps taken in the project by different stakeholders and the challenges encountered. It presents the various burning issues that were raised and reflects on different views put forward by various stakeholders during the debates. The article seeks to contribute to the literature dealing with the assessment of postapartheid reconstruction endeavours.

2. HISTORICAL MOTIVATING FACTORS FOR THE GENERATION OF COMPETENCIES AND STANDARDS

Since the advent of planning in Africa, theory and models for urban development were largely transferred from Europe and America and overlaid on African traditional systems that were arguably unprepared for the new systems of housing, standards, public services, and development control procedures that were characterized by top-down approaches (Ndura, 2006; Shalaby, 2003: 15; Smyth, 2004). The approach to planning in general was influenced by early planning in Britain2 and was concerned with public health and safety. It stressed 'efficiency concerns' and was dominated by the scientific approach of architects and engineers, who held the view that all planning problems had technical solutions (McCarthy & Smit, 1984). The project of apartheid, specifically in South Africa, was associated with the suppression of Black races through forced removals from urban locales and were facilitated by state planners. Although some planners opposed apartheid (e.g., Planact, Built Environment Support Group, Development Action Group), planners in general supported the state ideology of separate development. Therefore, they were viewed as the 'handmaidens' and 'soft cops' of the apartheid state (Davies, 1981). To a large degree, planners lost credibility in the public eye, due to their involvement in projects driven by the apartheid government. Invariably, this left the country with an indelible structure of fragmented cities marked by racial and income divisions and inequalities (Lemon, 1991; Mabin, 1992; Parnell, 1993).

2.1 Towards the establishment of a Standards Generating Body

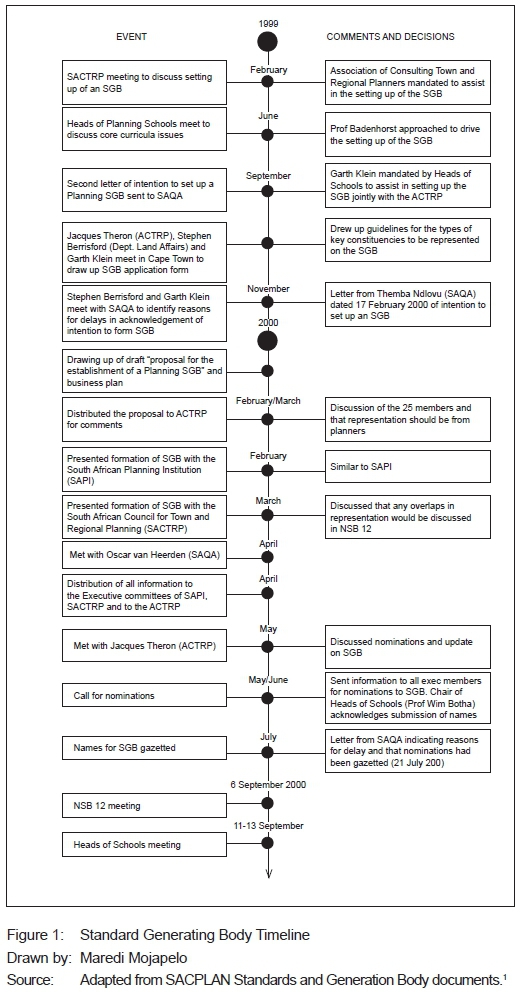

Therefore, the impetus for development of C&S in the planning profession was discernible at the dawn of democracy in 1994. Todes and Harrison (2004: 188) noted that conferences were held to chart the way forward for the profession in 1995 (DPASA, 1995; RDP Office, 1995). The initial attempt to develop competency standards was undertaken by the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA), which was established through the South African Qualifications Standards Act (No. 58 of 1995).3 In terms of this statute, SAQA's responsibility was to develop and implement policy and criteria for recognizing professional bodies and register them for the purposes of generating competency standards that adhere to the National Qualifications Framework (NQF).4 The NQF provides a framework that sets out the boundaries of a standardised qualification system, in order to recognise skills and categorise them according to a unified structure of recognised qualifications. Accordingly, a Standards Generating Body (SGB) for the planning profession was set up in May 2000.

The process of generating C&S for planning began in September 2000 at a Heads of Planning Schools meeting held in Bloemfontein. This meeting identified core competencies, which embraced the breadth of the field, but were open to variations (Harrison, Todes & Watson, 2008). They are now referred to as Bloemfontein competencies and were influenced by the work undertaken by the RTPI Education Commission in the United Kingdom (Todes & Harrison, 2004). Rather than define a set of competencies, the work from 2000 identified areas of preferred planning knowledge. Although a number of exit level outcomes were identified (SACPLAN, 2014a: 36), they did not engage with issues relating to registration of the different categories of planners and identification of planning work (SACPLAN, 2014a: 41). Nevertheless, many schools have applied and referred to this set of competencies in the preparation of their programme outlines and accreditation reports.

In addition, these competencies provided more motivation for the SGB to proceed with their registration application with SAQA to ultimately become a registered Planning Standards Generating Body in South Africa. However, the registration of the Planning Standard Generating Body in 2002 was challenging. There was a low level of participation by key stakeholders, resources were limited and the registering period of the Standards Generating Body ultimately expired and a new set of members were to be nominated (SACPLAN, 2014a: 23). By the early 2000s, the country was experiencing inadequate planning capacity, as reflected in the backlog of applications, due to slow processing of land development applications in municipalities and the lack of transformation of South African cities (Todes & Mngadi, 2007). Subsequently, "City, Urban and Regional Planning and Engineering Skills" were identified as some of the country's seven priority areas for the Joint Initiative for Priority Skills Acquisition (JIPSA) in 2005 (JIPSA, 2008).

The recognition by President Thabo Mbeki of the capacity crisis in the Accelerated and Shared Growth-South Africa (ASGISA) gave much needed momentum for the C&S project to resume in earnest (The Presidency, 2006).

The Local Government SETA (LGSETA) ring-fenced a budget of R5 million to fast-track the development of so-called town planning competencies, the provision of bursaries for Town Planning students, and the development of programmes for on-going professional development for municipal officials. JIPSA's Annual Report (2008) points out that it was agreed that SACPLAN would play a leading role in driving the C&S process following the registration. The intention was to set up a team drawing from the SAQA, and the SGB Task Team made up of town planning experts (JIPSA, 2008) to undertake the process.

The SACPLAN consolidated report (2014a: 23) points out that the first plenary meeting of the Planning SGB was held on 15 August 2006. This was followed by a scoping workshop with the Heads of Planning Schools, held on 7 November 2006 in Durban (SACPLAN, 2014d: 3). The purpose of the workshop was to identify specialised skills and competencies relating to Town and Regional Planning. The SACPLAN consolidated report (2014a: 23) indicates that the workshop participants did not agree on some of the basic tenets of the process, many of which were drawn from the example of experience of the Quantity Surveying profession. Although some knowledge domains, competencies and skills were generated at this meeting, there was no real ability to tackle competencies in relation to level descriptors and critical-cross-field outcomes, nor was any international benchmarking done (SACPLAN, 2014a: 23).

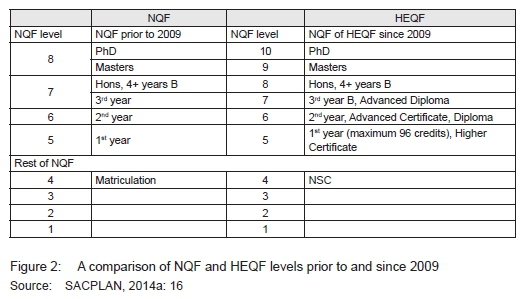

On 5 October 2007, the Government gazetted a new Higher Education Qualifications Framework (HEQF), which outlined the new requirements for the setting up of academic qualifications and courses.

The Gazette (Government Notice No. 928) noted that "[s]eparate and parallel qualifications structures for universities and technicians have hindered the articulation of programmes and transfer of student between programmes and higher education institutions..." and so required the "need for a single qualifications framework applicable to all higher education institutions" (RSA, 2007). The new framework amended the old framework in terms of NQF levels and credits per qualification, and required the Masters to be offered as a one-year qualification.5

These changes sparked a flame of discussions among planning schools about compliance. A meetin was held at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, regarding the new HEQF alignment on defining the core competencies for planning. This meeting sought to explore a common mechanism for responding to the new national requirements. However, the effort was eclipsed by the call for nominations of new members for SACPLAN who had a mandate to take this responsibility (JIPSA, 2008). In the same year, Wendy Ovens and Associates (consultants) drew up a set of competencies as part of a JIPSA study (Wendy Ovens & Associates, 2007). The report provided an array of competencies categorised for planning as well as those that are shared with other disciplines.

The report has been a major point of reference and comparison in the subsequent development of competency standards.

2.2 Challenges of the profession in the 1990s and 2000s

No tangible policy changes were introduced by the Council in the 1990s and 2000s. The understanding and perception of planning still left much to be desired. Parnell and Robinson (2006) point out that Eurocentric values remained central vectors in the framing of planning to reproduce practices that are patterned in accordance with the international discourses informing local policy development. Watson (2011: 206) observed that many of the "apartheid planning laws remained in place". It has also been argued that markets were dictating, in unprecedented ways, what presumably a democratic South African state could do or not do for its citizens (Mbembe, 2012). Harrison and Oranje (2002: 28), for example, observed "a growing disjuncture between the spatial patterns of planners as captured in their planning frameworks and patterns of investment in the urban environment". Todes (2011: 121) also remarked that "traditional forms of land-use management are integral to property values and are fiercely defended, and they exist in the context of remaining fragmented and differentiated systems inherited from apartheid".

Invariably, planners have been found to be working on behalf of the market and are often complicit or behind the large swathes of displacement of people that are poor in the major cities of the country in the postapartheid era (Watson, 2009: 163). This has signified that the group of planners that saw themselves as inheritors of the advocacy tradition of planning in the 1970s and 1980s has disappeared or is disappearing. Instead, activism has been replaced by 'profits' and so some planners have become the 'handmaidens of global capitalism'. The dominance of the market has also drawn planners into other disciplines such that the "planning profession has increasingly become part of a larger multidisciplinary profession in the built environment and has lost its voice and autonomy" (Harrison et al., 2004: 197). Apparently, areas of focus such as housing, project management, community development, local economic development, and public management have become part of planning and planning has become part of them (Harrison et al., 2004: 197).

This blurring of professional boundaries between planning and other related professional disciplines had become a source of huge confusion in the regulation of the profession. Berrisford (2006) observed that people who did not hold a planning qualification were doing a great deal of planning work. Notably, various government departments responsible for dealing with different aspects of planning in the country were hiring graduates from other disciplines into planning positions. Ironically, it is common to hear qualified planners claiming that they do not know 'what planning is anymore', while non-planners claim to be planners. Even more unsettling is that some of the non-planners who had years of practice in the field were demanding professional registration (Lewis, 2012: personal communication). Unfortunately, this demand could not be met (where permissible), because the council did not have an appropriately designed planning-specific policy or mechanism to administer the Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) (Lewis, 2012: personal communication).

The final reports were presented in workshops with the SACPLAN Reference Committee on 3 December 2013; a workshop with CHoPS on 23 and 24 January 2014, and three workshops with other key stakeholders at OR Tambo Airport on 20 February; at Elangeni Hotel in Durban on 27 February, and at Taj Hotel in Cape Town on 6 March 2014.

During the Gauteng workshop, it was observed that lawyers, geographers, surveyors, social workers and teachers are doing the jobs of planners (Gauteng workshop, Protea Hotel, Kempton Park, 20 February 2014). Therefore, there are many instances where non-planners are supervising planners in the work environment (Todes & Mngadi, 2007: 5). In some municipalities, an individual can assume multiple roles including that of a planner without the correct qualification. While the reasons for doing this vary from pragmatic to absurd, the scenario is compounded by the fact that some of the professional planners earn far less than the non-planners. They stated that this financial variance signified that the role of planners is poorly appreciated or understood in the public sector. Conversely, planners themselves were being employed in jobs that were traditionally nonplanning. It became common to hear planners claiming, "I am hired as a planner but what I am doing is not planning work" (personal communication with workshop participant at Gauteng Workshop).6

In the Gauteng Workshop, there was also a concern about the variable/inconsistent quality of qualified planning graduates. The main concern about quality was expressed mainly by employers (public and private) demanding universities to improve skills and upgrade the curriculum with regard to spatial techniques and critical thinking. The role of the Council in ensuring quality education was put under question. Unfortunately, the Council could not address this

challenge adequately, because there was no planning-specific accreditation criterion for assessing planning schools. The Council relied on the Council of Higher Education criterion, which was generalised. At the combined CHoPS-SACPLAN meeting of 2009 held in Pretoria, SACPLAN was questioned on being technical and bureaucratic in its accreditation assessment and witch-hunting in its demeanour. These developments were fomented by the fact that there was no quality assurance for practising registered planners through a Continuous Professional Development (CPD) process to ensure professional development of registered members. This could not be met, because the Council had no implementable CPD policy framework.

Ultimately, it was clear that the regulatory system to ensure high quality of planning skills and to regulate the profession were in a state of flux (Todes & Mngadi, 2007: 7). This lacuna generated a huge wave of despondency among planners in the late 1990s and 2000s. Many planners did not perceive the value of professional registration, due to the weak system of accountability in the profession. Harrison and Kahn (2002) observed that membership of the South African Planning Institution (SAPI), the professional planning organisation, dropped from 1,100 in 1996 to 300 in 2001. By the early 2000s, the effective 'de-professionalization' of planning became a concern for both SACPLAN and SAPI (Todes & Mngadi, 2007: 7).

3. SACPLAN IS 'REINVENTING PLANNING' AND 'CHANGING LIVES'

Following the inauguration of the second Council (SACPLAN 2) in 2008, the Council members developed a vision statement -"Reinventing Planning, Changing Lives". In working towards reinventing planning, SACPLAN re-initiated the process of generating C&S as the benchmark against which the challenges of the profession highlighted earlier could be addressed. SACPLAN's (2011: 3) Bulletin states that the purpose of the process was to ensure that practices, skills, knowledge and related policies in the country respond effectively to the planning needs of the profession.

3.1 Institutional arrangements for the project

Four main institutions were involved in the C&S project. First, the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform (DRDLR) acted as the parent Government department to which SACPLAN reports in terms of statutory mandate, budget and audits. Secondly, the Education and Training Committee (ETC), a subcommittee of SACPLAN, acted as the project manager. The ETC is constituted in terms of the Planning Professions Act, Chapter 2, section 6(3). It has three representatives from planning schools. The Committee worked closely with the CEO of Council. Thirdly, the Local Government Sector Education and Training Authority (LGSETA) provided funds in terms of an MOU drawn up between SACPLAN and LGSETA in the JIPSA arrangement (see page 5). Fourthly, the facilitators were commissioned to be the main producers of the reports and conductors of workshops in accordance with the Council-approved terms of reference. The main stakeholders were representatives from the Committee of Heads of Planning Schools (CHoPS),7 the voluntary associations, e.g., South African Planning Institute (SAPI),8 the South African Association of Consulting Professional Planners (SAACPP),9 and the South African Local Government Association (SALGA)10. Representatives from provincial and local governments' planning departments and other built environment councils, e.g., the Council of the Built Environment, were also included. Provision was made for private and parastatal bodies to make input into the process.

3.2 Three phases of the project

The procurement of the project was divided into three phases. Phase 1 involved the production of a report based on a status quo analysis in January 2010. This involved the review of different research initiatives for extracting core issues as well as the identification of international experience in the identification of competencies.

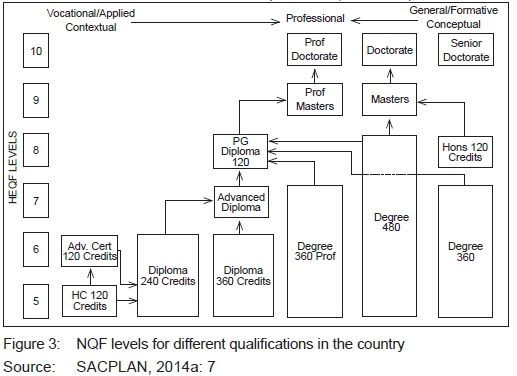

Phase 2 entailed the generation of the C&S at different National Qualifications Framework (NQF) levels in the different hierarchy of the qualifications prescribed in terms of the new Higher Education Qualifications Framework (HEQF). This means that the competencies are generated commensurate to the different levels (e.g., diploma, graduate, and masters) of qualifications. Figure 3 reflects the NQF levels from Ave to ten and the equivalent years of study for each qualification required in terms of credits as well as the possible articulation between levels in the hierarchy of qualifications. When the second phase report was produced, a consultative workshop was held with the SACPLAN Reference Committee.11

Phase 3 involved 'the identification of credits and standards in line with each qualification' available in planning education of the country. This alignment shows the progression routes for career development from the bottom to the top and across different qualifications. The presentation of clarity on C&S for each qualification, together with the identification of credits and progression routes, set the basis for the development of new curricula and realignment; new categories of registration; the development of a hierarchy of employment; the process for the Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL), and Continuing Professional Development (CPD).

The task of the facilitators included the production of the following compendium of policies: Curriculum development guidelines; accreditation criteria; new registration criteria; a new job-profiling policy; RPL policy, and CPD policy.

3.3 The identification of competencies

A group of three sets of related competencies were identified, namely generic, core, and functional competencies. Generic competencies are the essential skills, attributes and behaviours that are considered important for all planners, regardless of their function or level (SACPLAN, 2014b: 12). These are the basic competencies that are common to all disciplines. They are also called mandatory competencies based on the requirements and expectations on personal, interpersonal, professional practice, and business aptitude (Trinder, 2008: 166). They include critical thinking; interpersonal competencies; communications; leadership, as well as professionalism and ethical behaviour.

Core competencies are the set of specific knowledge, skills, abilities, or experience that a planner must possess in order to successfully perform work and activities that are central to professional planning practice (SACPLAN, 2014b: 12). They are the primary competencies of the chosen pathway of the planner as a professional (Trinder, 2008: 166). This set of competencies distinguishes planning from the other built and natural environment and community development professions with which planning interfaces. They can be considered the 'what' and the 'how' of the planning profession. The 'core' part of the term indicates that an individual has a knowledge and skills base from which to add value when undertaking a specific planning task. These include settlement history and theory; planning theory and public policy; planning sustainable cities; making places; regional development and planning; institutional and legal frameworks; environmental planning and management; transportation planning; infrastructure planning; integrated development planning; urban land economics; urban sociology, as well as research and dissertation (SACPLAN, 2014b: 20).

Functional competencies are the "basic skills and behaviours that are needed to do a job successfully" (Cambridge Business English Dictionary, 2011: 376). These competencies relate to 'how to do' aspects of planning. They describe the knowledge, skills and/or abilities required to fulfil required job tasks, duties or responsibilities. They respond to the 'technical' needs that are specific to that job or profession (SACPLAN, 2014b: 32).

For this reason, the functional competencies focus strongly on techniques and methodologies, but not all are unique to the planning profession. The ones identified in this instance are based on a common set of functional competencies used both internationally and locally. These include survey and analysis; strategic assessment; local area planning; layout planning; plan making, and plan implementation (SACPLAN, 2014b: 32).

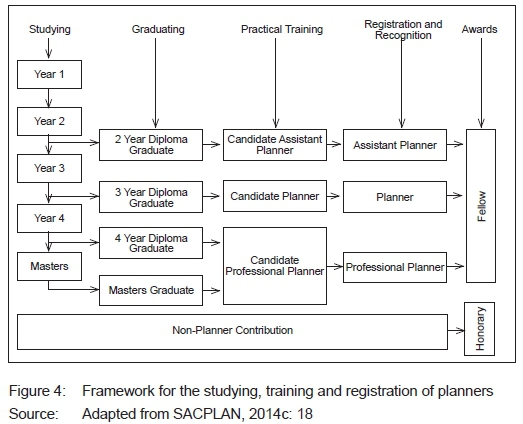

The report further presents new categories of registration replacing the old ones (SACPLAN, 2014c: 11-12). The old system consisted of three categories: a Candidate Planner for all graduates prior to registration; a Technical Planner for registered planners with a National Diploma, and a Professional Planner for graduates with an Honour's, Bachelor of Technology (BTech), or Master's qualification. The new categories are as follows: an Assistant Planner for graduates with a National Diploma;12 a Planner for graduates with a three-year degree, and a requirement for Professional Planner status remains unchanged. The Council has also adopted two new awards for its membership, namely a Fellow and an Honorary status. A Fellow membership is awarded to registered planners who have rendered outstanding services to the profession. The Honorary status will be awarded to an individual who is not a registered planner, but who has made a significant contribution to the planning profession. Both awards will be based on a nomination and an appraisal process (SACPLAN, 2014c: 13). The new system introduces a new sequence through which planners grow an entire lifetime career. It removes the stigmatised label of a Technical Planner, which was condemned as stereotypical, and demeaning (SACPLAN-CHoPS meeting at DUT).13 This robust set of categories is also more distinct and clear without combining levels of qualifications. The report also stipulates the minimum competency standards for planning educators and their programmes in terms of the minimum of 60% of staff that should be professionally registered professionals as well as the minimum qualifications requirements for teaching (SACPLAN, 2014b: 37).

Various types of planning domains, through which planners should gain practical experience before they register two years after graduation, were identified. These guidelines assist planners to gain the requisite experience for registration purposes. They are divided into four categories, namely A-Survey and research; B-Plan formulation; C-Plan implementation and administration, and D-Other types of planning work in related fields. The minimum requirements for each category of registration are stipulated in the document (SACPLAN, 2014c: 14). The proportion of experience required for each NQF level varies across the levels.

The final reports were presented in workshops with the SACPLAN Reference Committee on 3 December 2013; a workshop with CHoPS on 23 and 24 January 2014 at Durban University of Technology, and three workshops with other key stakeholders at Protea Hotel Kempton Park on 20 February; at Elangeni Hotel in Durban on 27 February, and at Taj Hotel in Cape Town on 6 March 2014. The 2015 workshops were held to share the outcomes of the process.

4. REFLECTIONS ON CONTENDING VIEWS

4.1 Meaning of planning

In the workshops, the generic competencies were easily received; however, different parties contested the core and functional competencies. Much of the contestation was fuelled by different views on the understanding of planning. They were planners who viewed planning in terms of traditional town planning. The use of the term 'traditional town planning' is associated with a physical site, region, territory and boundary, which imply, at least on first thought, a static account of geography (Capello, 2011). To this group, town planning subscribes to the Kantian claims of an objective criterion where space is a container. Thus, for these planners, C&S implies an exercise that is meant to preserve the historically inherited traditions of planning - implicitly "a revitalization of old British modernist planning which viewed town planning essentially as an exercise of physical design" (Taylor, 1999: 330). Invariably, planning was viewed as a technical process concerned with land use in terms of the standards, codes and instruments prescribed in legislative and policy documents. The group wanted to develop core and functional competencies with a strong physical planning focus and an organisational logic that emphasised legal and structural order to ensure compliance. Hence, the group was also calling for quantitative specifications for the competency requirements, in order to enforce compliance of curriculum designs to the C&S framework of planning schools. They wanted them marked by clear quantities of scope, coverage and measures.

As such, the initial proposals of the accreditation guidelines were based on a quantitative matrix that specified quantitative specifications for minimum requirements to define compliance. This was met with a huge rejection from CHoPS and other planners. These objectors wanted the competencies to be set in a flexible manner, using qualitative statements. This group generally espoused the concept of planning in terms of 'urban planning'. Unlike the view of fixating planning in a territory, the inference from the concept of 'urban planning' was the sense of territoriality - the idea that "there is no such thing as a boundary . Every space is in constant motion." (Thrift, 2006: 140, 141). This view recognises that places are porous to a greater or lesser degree. Therefore, space is not only physical, but is also made up of complex cultural constructions of space constituted by networks, multiplicity and diversity. This group reckoned with the notion of the spatial turn - "the move away from a 'container' image of space towards an acknowledgment of its mutability and social production" (Kümin & Usborne, 2013: 317). It is "the idea that space appears as both matter and meaning, as simultaneously tangible and intangible, and constitutive of social circumstances and physical landscapes" (Arias, 2010: 29).

4.2 Reservation of planning work

These opposing views precipitated much of their influence on the highly debated issue of the 'reservation of planning work'. Subsection 16(3) of the Planning Professions Act (No. 36 of 2002) provides that the reservation of work prescribed under section 16(2) restrains any persons not registered in terms of the Act from undertaking reserved work. Hence, in all the workshops, people were calling for identification of planning work to be exclusively delineated for planners. The delineation of planning work hinged on what had been identified as core and functional competencies. Those who advocated for 'town planning' emphasized functional competencies. They argued that "[a] medical doctor does not do the work of lawyers. So planners must set aside what they do" (Workshops in Gauteng KwaZulu-Natal and Western Cape).14

However, there was a strong opposition to reservation of work that came from practitioners from other disciplines such as, e.g., law and quantity surveying. Following a workshop on the proposals held at the Manhattan Hotel on 4 June 2012, the Law Society of South Africa (LSSA) objected in toto to the content of draft Regulation 5 regarding reservation of planning work:

It is unacceptable to the Law Society that rezoning, special consent and other "standard" planning applications are reserved only for registered planners. Lawyers routinely prepare and lodge land development applications for projects entailing the amendment of approved plans and policies. Rezoning, special consent and DFA applications fall into this category, and it would be absurd to suggest that lawyers should henceforth be excluded from such work (LSSA 2012: online).

They pointed out that engineers, surveyors and others do township applications, and these frequently involve some aspect of scheme and plan amendments. They claimed that many of them have been doing so for years. They argued that the Draft Rules and section 4 of the Regulations constitute a massive attempt by the planning profession to annex areas of work, for which planners may not claim an exclusive right, and which planners do not perform exclusively at present. Similar objections from quantity surveyors had come up at an initial consultative workshop in December 2008. This objection was met with a huge tide of rejection from the planning fraternity.

As KENA Consult (2015: 25) asserted in a position paper for planning:

Overall, the cornerstone of professionalization entails work reservation to protect the public at large and the members within the profession. All professions identify with a specific field of work and its related functions based on a system of work reservation.

The alternative view of the urban planners was not an objection to reservation of work, but rather a support for broadening the agenda of planning in recognition of the fact that planning is "an activity that involves other professionals (architects, engineers, lawyers)" (Neuman, 2005: 124). This view accepts reservation of work, but argues that it is through the stipulation of professional standards rather than the identification of strict and narrow categories of planning work. This is in view of the fact that "[u]rban planning is hard to define and harder to practice because it is the unsteady, always renegotiated resolution of a number of contradictions, paradoxes, and tensions" (Fischler, 2011: 108). The Wits and Cape Town universities' comments, for example, state:

We would argue that narrowing the agenda for planning is contrary to the interests of promoting sustainable and inclusive places, and it is contrary to the recommendations for a more developmental approach to planning made by international organizations such as UN-Habitat, the Commonwealth Association of Planners, and the resolutions of several of the South African Planning Institute's Planning Africa Conferences since 2002 .... we are concerned that planners might be pushed out of these more developmental areas of work, and 'planning' might be seen again as a narrow technical activity for which it has been so widely criticized internationally.15

4.3 Master's qualification

While this controversy between the different professions was motivated by the intractable interdisciplinary nature of the planning profession, there was also tension among planners. Some of the planners with undergraduate and technical university degrees strongly questioned the proficiency of graduates with a Master qualification. This group of planners was arguing that a Master's qualification takes two years to obtain, whereas they take three or four years, but both register as professional planners. One participant burst out at the Durban workshop and said: "She supervises some of the people with masters, and some of them know nekx" (meaning nothing) (sic). Reiterating the point, a senior official planner raised questions about the purpose of a Master's degree, if the qualified students register as professional planners just like those with honours. The concern arose because many of the Master's programmes admit people who come with non-planning degrees, but who, upon graduation, often land in senior positions in the public sector. Apparently, the dominant perception among the aggrieved planners was that they possess more knowledge and technical skills, in particular, than those with Master's degrees.

The thrust of this argument was obviously uninformed by the significance of NQF levels in education. While the facilitators addressed this standpoint, some of the planners could not accept the explanation. In the informal conversations, a senior official planner asserted that he prefers employing undergraduate and technical university degree holders than master holders, because "[t] hey have the technical skills to do the job, period!" He argued that master graduates normally enter the job environment at a senior level and "tend to bring instability in public organisations because they move from job to job much quicker" (personal conversations with participant during lunch time).16While much of these arguments found resonance among some private employers, they were mainly fuelled by perceptions often arising from workplace job dynamics. This perception was supported by the fact that the Occupation Specific Dispensation (OSD) 17 for planners did not recognise the category of technical planners at the time (Department of Public Services and Administration, 2007: online).

4.4 Bachelor of Technology qualification

The wave of this debate on the proficiency of the Master's qualification came to a head when another senior planner questioned the academic strength of the Bachelor of Technology (B.Tech) degree (offered at three Universities of Technology) as an equivalent to the Honour's degree. Irrespective of the degree's strength in "technical training and spatial dimensions of planning" (Tapela, 2012: 13), the standing of the B.Tech was a subject of conjecture on the amount of time spent in class. The cause of disagreement arose from the fact that the B.Tech degree includes Work Integrated Learning (WIL) as part of the four years of training. Some views suggested that the degree did not have the same intellectual rigour as a four-year academic degree. While some people view the degree as part of vocational training with learning outcomes geared towards more technical skilling (as opposed to more academic training), others have questioned the intellectual rigour of WIL to provide an equivalent strength to academic forms of learning. The debate brought into question the amount of time spent in class versus in offices/work place. The national Department of Education has since issued a circular to phase out the B.Tech in 2019. The matter pertaining to length of time spent studying also led to a decision by CHoPS to disallow graduates with a one-year Honours or a postgraduate diploma in planning from registering, due to the short time of training (CHOPS-SACPLAN meeting at Stellenbosch University, 2014).18

4.5 Experiential learning

The issue of time spent in class versus out of class was also discussed in terms of distance education. Some argue that distance learning in planning will be instrumental in the empowerment of disadvantaged communities and facilitate more access to planning education, especially to those who are employed. They proposed that it would save resources, e.g., space for facilities and open opportunities to those who want to study at their own pace. While others were not opposing the idea, they raised concerns that self-instructional material is not enough to teach planning. They argued that modules are not pedagogically adequate to teach planning, since it is a practical subject that necessitates experiential learning. They recognised that many people on the African continent do not have the appropriate technological facilities for distance education. Even those who do encounter difficulties. Supporting services (e.g., electricity) are often unreliable and/or unavailable. One senior planner was concerned that "distance education is likely to benefit the privileged sections in society and maintain planning to be an elitist discipline and in the hands of people who are not fully connected with the practical needs of the continent". For this planner, "the motif (of distance learning) might as well be that we are producing graduates that can only plan for the first world" (Singh, 2009: personal communication).

4.6 International accreditation

Invariably, similar sentiments have been central to the emphasis on 'local content', 'local systems', and 'local perspectives' often laced on arguments for Africanisation of education (Makgoba & Seepe, 2004). These have been associated with cultural politics concerned with enabling ways of representing the Black Africans and promoting their capacities and social forms in the field of education. They have also opposed suggestions that degree programmes should embrace international accreditation from associations such as the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI). Some planners have argued against international accreditation as neo-colonial practice. Therefore, it appears that re-enacting processes of accreditation by former colonial masters are self-destructive. This scepticism has become more intense, following the recent "fees must fall" protests in the country in 2015/2016, which demands transformation and decolonisation of the curriculum. Other planners view international accreditation as mutually beneficial to both the RTPI and the Planning Schools. They view it as something that will extend local networks, influence the Commonwealth Countries, and facilitate movement of South African planners who wish to operate in a globalised environment (SACPLAN- CHOPS Meeting in Pretoria 2009).19 It is also asserted that some of our graduates already work overseas and accreditation will lead to strengthening the links and enhance international interactions.

4.7 Significance of the debates

These debates have implications for curriculum development, accreditation of schools, registration of planners, and professional practice.

• All planning schools will recalibrate their curricula, ensuring that the intricate connections between technical and theoretical knowledge contended in these debates move away from theoretically totalizing and pedagogically oppressive curricula. Planning schools will ensure that curriculum development becomes a vital force in shaping transformation of the planning mind, space, practice, and society.

• The Council will now utilise a planning discipline-specific set of criteria in the accreditation of schools, one that is intelligible to the planning profession in terms of its C&S for every planning qualification. Every school will meet a set of minimum C&S in their different fields of specialisation to facilitate meeting the needs of society and the industry.

• As a result, the registration of planners through a new examination system will develop a professional body of planners with skills and knowledge to transform society towards a democratic society. The approval of the legislation will prevent non-planners from taking planning jobs.

• The Planning professional practice should then be the ambit of registered planners only who can undertake work that is reserved for planners in terms of the legislation.

5. CONCLUSION

Unfortunately, the implementation of some of the policies adopted will not happen immediately. Some of the policies such as examination guidelines for registration, RPL and CPD require the setting up of structures (e.g., a coordinating board) before they can be implemented. Others will require the amendment of the legislation in parliament before they are implemented (e.g., new categories of registration). Most importantly, it is crucial to note that there are larger issues of decoloniality and transformation that still need attention in South Africa and in the planning profession, in particular. Sewpaul (2007: 17) has pertinently observed that,

[g]iven the impact of over 300 years of colonialism and almost 50 years of apartheid, there can be no denial that a Western hegemony has become inscribed into South African society and our academic institutions. There is, unarguably, a need for an emancipatory pedagogy to develop an ethos of scholarship that overcomes colonial mental slavery, and one that addresses local and national context-specific realities while being cognisant of, and responsive to, international issues and the multifaceted consequences of globalisation.

Heleta (2016) notes that South African universities have not considerably changed; they remain rooted in colonial, apartheid and Western worldviews and epistemological traditions. The high-status of Eurocentric knowledge has become the dominant kind of knowledge deemed immutable enough in the planning curricula of universities in South Africa. The subjugated knowledges of economically disadvantaged groups, women, and minorities are insistently marginalised. For Lyotard (2003), grand narratives do not problematize their own legitimacy; instead, they deny the historical and social construction of their own first principles and, in doing so, negate the importance of difference, contingency and particularity. It goes without saying that SACPLAN has been consciously and unconsciously influenced by, and in turn influences, and becomes constitutive of these dominant paradigms and ideologies.

In order to untangle the link between this dominant knowledge and power, there is a need to interrogate and demystify the interests that informed these knowledge forms so that knowledge is not inexorably given and self-justified. Therefore, the Council needs to undertake research, in order to explore how the total body of the profession situates itself in the intersection of language, culture, power, and history, the nexus in which subjectivities of planners are created during their training and professional practice. A programme of continuous research needs to be undertaken to ensure that the dialectical processes of understanding, criticising and transforming are germane to the democratic transformation of the profession. It should lead to the construction of new forms of subjectivities, social relations, and institutional formations that are more hospitable to human rights, equality and social justice. Such a research requires a critical perspective that demands that the processes of curriculum development, accreditation, registration, and so on be interrogated together with the ideological location of the Council itself. Ultimately, SACPLAN's realisation of transformation will always rely on its ability to mobilise different stakeholders in the planning profession to come together and debate constructively, because C&S' generation is an ongoing process.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I acknowledge that attendance of the workshops was possible through SACPLAN support. Special thanks to Martin Lewis, CEO of SACPLAN, and his staff for providing information on C&S' workshops and the SACPLAN Bulletin. Many thanks to Mr Garth Klein for providing the files of the old Standard and Generating Body. The author also thanks the editors of the Journal and the reviewers of the manuscript for their help in improving this article. Any errors and omissions are clearly mine.

I declare no potential conflict of interests with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

REFERENCES

ARIAS, S. 2010. Rethinking space: An outsider's view of the spatial turn. Geo-Journal, 75(3), pp. 29-41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-010-9339-9 [ Links ]

BENJAMIN, W. 1969. Theses on the philosophy of history. In: Benjamin, W., Wieseltier, L. & Arendt, H. (Eds). Illuminations: Essays and reflections. New York: Schocken, pp. 253-264. [ Links ]

Berrisford, S. 2006. Towards a JIPSA business plan for strengthening urban planning skills in South Africa. A draft report prepared for the JIPSA Planning Working Group. [ Links ]

CAMBRIDGE BUSINESS ENGLISH DICTIONARY. 2011. What is functional competency? [Online]. Available at: <http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/business-english/functional-competence> [Accessed: 21 September 2017]. [ Links ]

Capello, R. 2011. Location, regional growth and local development theories. AESTIMUM, 58, pp. 1-25. [ Links ]

DAVIES, R.J. 1981. The spatial formation of the South African city. Geo-Journal, 75(2), pp. 59-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00196325 [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SERVICES AND ADMINISTRATION. 2007. Occupation Specific Dispensation (OSD) in the public service. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.gov.za/public-services-and-administration-occupation-specific-dispensation> [Accessed: 21 September 2017]. [ Links ]

DPASA (DEVELOPMENT PLANNING ASSOCIATION OF SOUTH AFRICA). 1995. Towards and beyond 2000: The future of planning and planning education (Conference Abstract). Johannesburg: Development Planning Association of South Africa. [ Links ]

FANON, F. 1965. The wretched of the earth. New York: Grove Press. [ Links ]

FISCHLER, R. 2011. Commentary: Fifty theses on urban planning and urban planners. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 20(10), pp. 1-8. [ Links ]

HARRISON, P. & KAHN, M. 2002. The ambiguities of change: The planning profession in South Africa. In: Thornely, A. (Ed.). Planning at a global era. London: Ashgate, pp. 255-278. [ Links ]

HARRISON, P. & ORANJE, M. 2002. Between and beyond laissez faire expansion and planned compaction: The pragmatic 'poly-city' approach. South African Property Review, pp. 25-30. [ Links ]

HARRISON, P., TODES, A. & WATSON, V. 2008. Planning and transformation: Learning from the post-apartheid experience. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

HELETA, S. 2016. Decolonisation of higher education: Dismantling epistemic violence and Eurocentrism in South Africa. Transformation in Higher Education, 1(1), pp. 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/the.v1i1.9 [ Links ]

JIPSA (JOINT INITIATIVE ON PRIORITY SKILLS ACQUISITIONS). 2008. Annual Report 2008. The Presidency. [ Links ]

KENA Consult. 2015. Review and Amendment of the PPA (Act 36 of 2002): Position paper/Issues report prepared and presented to Department of Rural Development and Land Reform. [ Links ]

KÜMIN, B. & USBORNE, C. 2013. At the home and in the workplace: A historical introduction to the spatial turn. History and Theory, 52(3) pp. 305-318. https://doi.org/10.1111/hith.10671 [ Links ]

LEMON, A. 1991. Homes apart: South Africa's segregated cities. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

LEWIS, M. 2002. Personal communication. Midrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

LYOTARD, J.F. 2003. From the postmodern condition: A report on knowledge. In: Cahoone, L. (Ed.). From modernism to postmodernism: An anthology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp. 481-513. [ Links ]

MABIN, A. 1992. Comprehensive segregation: The origins of the Group Areas Act and its planning apparatuses. Journal of Southern African Studies, 18(2), pp. 405-429. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057079208708320 [ Links ]

MAKGOBA, M. & SEEPE, S. 2004. Knowledge and identity: An African vision of higher education transformation. In: Seepe, S. (ed.). Towards an African identity in higher education. Pretoria: Vista University and Scottaville Media, pp. 13-57. [ Links ]

MBEMBE, A. 2012. Theory from the Antipodes. Notes on Jean & John Comaroffs' TFS. Johannesburg Workshop in Theory and Criticism, Vol. 5. [Online]. Available at:<http://jwtc.org.za/salon_volume_5/achille_mbembe.htm> [Accessed: 15 April 2018]. [ Links ]

MCCARTHY, J. & SMIT, D. 1984. South African city: Theory in analysis and planning. Cape Town: Juta. [ Links ]

NDEBELE, N.S. 2000. Archive and public culture (bottom of page). Cape Town. [Online]. Available at: <http://www.apc.uct.ac.za/researchers/professor-njabulo-ndebele/> [Accessed: 8 January 2018]. [ Links ]

NDURA, E. 2006. Western education and African cultural identity in the Great Lakes region of Africa: A case of failed globalization. Peace & Change, 31(1), pp. 90-101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0130.2006.00345.x [ Links ]

NEUMAN, M. 2005. Notes on the uses and scope of city planning theory. Planning Theory, 4(2), pp. 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095205054601 [ Links ]

LSSA (THE LAW SOCIETY OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2012. New memoranda. Comments on Planning Professional Rules, 11 June, p. 3. [Online]. Available at: <http://www.lssa.org.za/upload/documents/LSSA%20Comments%20on%20Planning%20Profession%20Rules%20JUne2012.pdf> [Accessed: 20 September 2017]. [ Links ]

PARNELL, S. 1993. Creating racial privilege: The origins of South African public health and town planning legislation. Journal of Southern African Studies, 19(3), pp. 471-488. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057079308708370 [ Links ]

PARNELL, S. & ROBINSON, J. 2006. Development and urban policy: Johannesburg's City Development Strategy. Urban Studies, 43(2), pp. 337-355. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500406710 [ Links ]

RDP (RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME) OFFICE. 1995. Report on the workshop on the future of the town and regional planning profession. (Internal Report). Johannesburg: Reconstruction and Development Programme Office. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2002. Planning Profession Act, Act 36 of 2002. Government Gazette No. 24049. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2007. Country's Report (5 October). The Higher Education Qualifications Framework: Higher Education Act, 1997 (Act No. 101 of 1997). Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

SEWPAUL, V. 2007. Power, discourse and ideology: Challenging essentialist notion of race and identity in institutions of higher learning in South Africa. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 43(1), pp. 17-30. [ Links ]

SHALABY, A. 2003. Unsustainable desert settlements in Egypt: The product, the process and avenues for future research, IHDP Newsletter, 3(2002), p. 15. [ Links ]

SINGH, M. 2009. Personal communication. SACPLAN Office, Midrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

SMYTH, R. 2004. The roots of community development in colonial office policy and practice in Africa. Social Policy & Administration, 38(4), pp. 418-436. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2004.00399.x [ Links ]

SACPLAN (SOUTH AFRICAN COUNCIL OF PLANNERS). 2011. Standards and competency generating for the planning profession. SACPLAN Bulletin, 1(4), p. 3, November. [ Links ]

SACPLAN (SOUTH AFRICAN COUNCIL OF PLANNERS). 2014a. Consolidated report on competencies and standards status quo, December. Midrand: South African Council of Planners. [Online]. Available at: <http://www.sacplan.org.za/documents/Consolidated%20Report%20on%20Competencies%20and%20Standards.pdf> [Accessed: 21 September 2017]. [ Links ]

SACPLAN (SOUTH AFRICAN COUNCIL OF PLANNERS). 2014b. Guidelines for competencies and standards for curricula development report, December. Midrand: South African Council of Planners. [ Links ]

SACPLAN (SOUTH AFRICAN COUNCIL OF PLANNERS). 2014c. Guidelines for the registration of planners report, December. Midrand: South African Council of Planners. [ Links ]

SACPLAN (SOUTH AFRICAN COUNCIL OF PLANNERS). 2014d. Competencies guidelines report final draft, compiled by Prof. C.B. Schoeman & Prof. P. Robinson from the Research Unit for Environmental Sciences and Management, North-West University. Midrand: South African Council of Planners. [ Links ]

SAQA (SOUTH AFRICAN QUALIFICATIONS AUTHORITY). 2014. The South African National Qualifications Framework. [Online]. Available at: <http://www.saqa.org.za/list.php?e=NQF> [Accessed: 21 September 2017]. [ Links ]

TAPELA, N. 2012. Mainstreaming informality and access to land through collaborative design and teaching of aspects of a responsive planning curriculum at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology. Town and Regional Planning, 60, pp. 10-18. [ Links ]

TAYLOR, N. 1999. Anglo-American town planning theory since 1945: Three significant developments but no paradigm shifts. Planning Perspectives, 14(4), pp. 327-345. https://doi.org/10.1080/026654399364166 [ Links ]

THE PRESIDENCY. 2006. Report (March-December 2006). Joint Initiative on Priority Skills Acquisition (JIPSA). [ Links ]

THRIFT, N. 2006. Space. Theory, Culture & Society, 23(2-3), pp. 139-155. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276406063780 [ Links ]

TODES, A. 2011. Reinventing planning: Critical reflections. Urban Forum, 22(2), pp. 155-133. [ Links ]

TODES, A. & HARRISON, P. 2004. Education after apartheid: Planning and planning students in transition. International Development Planning Review, 26(2), pp. 187-207. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.26.2.4 [ Links ]

TODES, A. & MNGADI, N. 2007. City planners: Report for the HSRC study on scarce skills for the Department of Labour. [ Links ]

TRINDER, J.C. 2008. Competency standards: A measure of the quality of a workforce. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 37(B6a). Beijing. [ Links ]

WATSON, V. 2009. The planned city sweeps the poor away...: Urban planning and 21st century urbanisation. Progress in Planning, 72(3), pp. 151-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2009.06.002 [ Links ]

WATSON, V. 2011. Changing planning law in Africa. Urban Forum, 22(3), pp. 203-208. [ Links ]

WENDY OVENS & ASSOCIATES. 2007. Towards a JIPSA business plan for strengthening urban planning skills in South Africa: Assessment of planning skills in South Africa. [Online]. Available at: <www.btrust.org.za/downloads/23_jipsa_assessmemt_planning_skills_sa_oct2007.pdf> [Accessed: 12 September 2017]. [ Links ]

Reviewed March 2018

Revised March 2018

The author declared no conflict of interest for this title or article.

1 The South African Council for Planners (SACPLAN) is the statutory Council of nominated members appointed in terms of the Planning Profession Act, 2002 (Act No. 36 of 2002) by the Minister of the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform (DRDLR) to regulate and ensure quality assurance of the profession (RSA, 2002).

2 Planning was introduced in South Africa from Britain and later America to address the issues of urban townships as well as of health and safety related thereto.

3 South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) was formed to oversee the development and implementation of the NQF in all areas of education and training. In order for SAQA to monitor such management systems, it accredited (provisional/full) institutions/ statutory bodies called Education and Training Quality Assurers (ETQAs). SACPLAN is one of them.

4 In 1995, the National Qualification Framework (NQF) was established in order to align the South African education and training systems with those of international standards of best practice. The NQF is a set of principles and guidelines providing a vision, a philosophical base and an organisational structure for a qualifications system (SAQA, 2014: online).

5 Diversion from this should be accompanied by explanation.

6 This person wants to remain anonymous.

7 A committee of heads of eleven planning schools in the country.

8 A representative body of planners promoting the profession of planning in South Africa.

9 A representative body of chartered planners promoting the profession of planning.

10 An autonomous association of all 257 South African local governments, comprising a national association, with one national office and nine provincial offices.

11 The consultative workshop was held at the SACPLAN Midrand offices, 3 December 2013.

12 During the Planning Professional Acts' consultative workshops conducted by the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform in 2015, the category of 'assistant planner' was debated to go back to technical planner (Personal communication with SACPLAN CEO, Mr Martin Lewis, O.R. Tambo, 10 May 2018).

13 Durban University of Technology, Town and Regional Planning Boardroom, 24 January 2014.

14 At Elangeni Hotel, Durban, 27 February 2014, and at Taj Hotel, Cape Town, 6 March 2014, respectively.

15 Joint Comments on SACPLAN Competencies Documents sent by members of staff from the Planning Programme of the University of Cape Town and Wits University, February 2014.

16 Professional Planner, eLangeni Hotel, Durban, 27 February 2014; this person wants to remain anonymous.

17 An OSD Occupation Specific Dispensation means revised salary structures that are unique to each identified occupation in the public service.

18 Stellenbosch Boardroom, 2013.

19 Town and Regional Planning Boardroom, University of Pretoria, 2009.