Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Town and Regional Planning

On-line version ISSN 2415-0495

Print version ISSN 1012-280X

Town reg. plan. (Online) vol.72 Bloemfontein 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp72i1.3

ARTICLES

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp72i1.3

Considering spatial planning for the South African poor: An argument for 'planning with'

Kelohloko ya thero/ tokisetso ya sepakapaka bakeng sa bafumanehi Afrika Borwa: Puisano bakeng sa "thero/ tokisetso ka"

Juaneé CilliersI; Hestia VictorII

IUnit for Environmental Sciences and Management, Urban and Regional Planning, North-West University, South Africa. Phone: 018 299 2486, e-mail: <Juanee.Cilliers@nwu.ac.za>

IIDepartment of Social Anthropology, School for Social and Government studies, North-West University, South Africa, e-mail: <victor.hestia@gmail.com>

ABSTRACT

This article considers the notion of 'spatial planning' in South Africa, elaborating on the challenges relating to the wide disparities between formal and informal areas. Town and Regional Planning theory and anthropological approaches are fused together in this article in an attempt to provide a more integrated approach to spatial planning, arguing in favour of 'planning with' poor South Africans, in contrast to 'planning for'. By using qualitative participant observation, an ethnographic fieldwork study conducted in Marikana informal settlement, Potchefstroom, South Africa, helped form reflections that offer valuable insights in support of the 'planning with' approach. Marikana residents' innovative DIY-formalisation plan of installing communal taps is considered a vivid example of pragmatic local solutions to service-delivery issues and it is argued that these solutions should be considered when 'planning with' the poor. The research argues that, despite being different in context, 'planning with' approaches have a prominent role to play in both formal and informal settlements. As such, the research elaborated on the value of 'planning with' approaches in South Africa, relating to environmental, social, economic, political and broader planning considerations. The article does not offer a generalizable solution to all planning challenges in South Africa. It concludes with a reflection of the ethnographic fieldwork conducted in the case study linked to broader themes of the possible planning interventions, considering the delineation of social power, context-based needs, ownership and accountability, and the importance of environmental education for all socio-economic classes, in an attempt to inspire planners, policymakers and anthropologists to And new ways of 'thinking with' and 'planning with' each other.

Keywords: Informal areas, 'planning with', spatial planning

ABSTRAK

Hierdie artikel oorweeg die idee van 'ruimtelike beplanning' in Suid-Afrika en brei uit op die uitdagings wat verband hou met die groot ongelykhede tussen formele en informele areas. Stads- en Streekbeplanningsteorie en antropologiese benaderings word in hierdie artikel saamgevoeg in 'n poging om 'n meer geïntegreerde benadering tot ruimtelike beplanning te bied, wat argumenteer ten gunste van 'beplanning saam met', in teenstelling met 'beplanning vir' arm Suid-Afrikaners. Deur gebruik te maak van kwalitatiewe deelnemende waarneming het 'n etnografiese veldwerkstudie in Marikana informele nedersetting, Potchefstroom, Suid-Afrika, gehelp om refleksies te vorm wat waardevolle insigte bied ter ondersteuning van die 'beplanning met'-benadering. Marikana-inwoners se innoverende DIY-formaliseringsplan van die installering van gemeenskaplike krane word beskou as 'n goeie voorbeeld van pragmatiese plaaslike oplossings vir diensleweringskwessies. Daar word aangevoer dat hierdie oplossings in ag geneem moet word as 'beplanning saam met' armes. Die navorsing beweer dat 'beplanning saam met'-benaderings 'n prominente rol kan speel in beide formele en informele nedersettings, ten spyte van die verskil in konteks. As sodanig het die navorsing uitgebrei oor die waarde van 'beplanning saam met'-benaderings in Suid-Afrika, in terme van omgewings-, sosiale, ekonomiese, politieke en breër beplanning oorwegings. Die artikel poog nie om 'n veralgemeende oplossing te bied vir alle beplanning uitdagings in Suid-Afrika nie. Dit sluit af met 'n weerspieëling van die etnografiese veldwerk wat in die gevallestudie uitgevoer is, gekoppel aan breër temas van die moontlike beplanningsintervensies, met inagneming van die afbakening van sosiale mag, konteksgebaseerde behoeftes, eienaarskap en aanspreeklikheid en die belangrikheid van omgewingsopvoeding vir alle sosio-ekonomiese klasse, in ' poging om Beplanners, Besluitnemers en Antropoloë te inspireer om 'saam te dink' en 'saam te beplan'.

Sleutelwoorde: Informele areas, 'beplan-ning saam', ruimtelike beplanning

TUMELO

Atikele ena e ela hloko tshitshinyo ya Thero/tokisetso ya Sepakapaka Afrika Borwa, e hlalosa diphepetso tse amanang le diphapang tse kgolo pakeng tsa dibaka tse molaong le tse seng molaong. Tsebo/theori ya toropo le setereke, hammoho le mekgwa ya "anthropology" di kopantswe hammoho atikeleng ena ka teko ya ho fana ka mokgwa o kopanetsweng ka ho fetisisa bakeng sa thero/tokisetso ya sepakapaka, ho buella taba ya ho "hlophisa hammoho le" MaAfrika Borwa a fumanehileng; e seng ho "hlophisa bakeng sa" bona. Ho sebedisa mokgwa wa boleng wa ho sheba bankakarolo, le phuputso ka tsela ya ho ya bathong ya "ethnographic", eo e ileng ya etsetswa dibakeng tsa bodulo tse seng molaong Marikana, Potchefstroom, Afrika Borwa, di thusitse ho etsa ditlhahiso tse fanang ka tsebo e nang le boleng bakeng sa ho tshehetsa mekgwa ya ho "hlophisa ka" katamelo. Lewa le letjha la baahi ba Marikana la "DIY formalisation" la ho kenya dipompo tsa setjhaba, le nkilwe jwaloka mohlala o hlakileng wa tharollo e ntle/utlwahalang la selehae, bakeng sa mathata a phano ya ditshebeletso; mme ho ngangisanwa ka ho re tharollo e ne e tlameha o elwa hloko nakong eo ho "hlophiswang le" bafumanehi. Dipatlisiso di re, ntle le phapang moelelong, mekgwa ya "ho hlophisa le" baahi e na le karolo ya bohlokwa dibakeng tsa bodulo ka bobedi: tse seng molaong le tse molaong. Ka hoo, phuputso e qaqisitse boleng ba mekgwa ya "ho hlophisa le" baahi Afrika Borwa, ho tse amanang le tikoloho -, setjhaba -, moruo- dipolotiki le dipehelo tse batsi tsa hlophiso/tokisetso.

Atikele ha e fane ka tharollo e akaretsang bakeng sa diphepetso tsohle tsa hlophiso/tokisetso Afrika Borwa, empa e qeta ka ho fana ka pono ya "ethnographic" ya mosebetsi wa diphuputso tsa ho ya bathong.

E le phuputso e entsweng thutong ya mehlala (case study), e amanang le dihlooho tse batsi tse ka bang teng tsa hlophiso e kenellang. Ho elwa hloko hlaloso ya matla a setjhaba, ditlhoko tse itshetlehileng hodima maemo, tokelo le maikarabelo; le bohlokwa ba thuto ka tikoloho bakeng sa dihlopha tsohle tsa setjhaba le moruo wa sona. Ka teko ya ho kgothalletse bahlophisi, baetsi ba molao, le di "anthropologists" hore ba fumane ditsela tse ntjha tsa ho "nahana" le ho "hlophisa" hammoho.

1. INTRODUCTION

One cannot look on the bright side of planning, its modern achievements (if one were to accept them), without looking at the same time on its dark side of domination. The management of the social has produced modern subjects who are not only dependent on professionals for their needs, but also ordered into realities (cities, health and educational systems, economies etc.) that can be governed by the state through planning. Planning inevitably requires the normalization and standardization of reality, which in turn entails injustice and the erasure of difference and diversity (Escobar, 2010: 147).

In 1999, two South African spatial planners (Vanessa Watson and Peter Wilkinson) and an anthropologist (Andrew Spiegel) opened their chapter on the politics of planning1 with the above quote by Columbian-American anthropologist, Arturo Escobar.2 Spiegel, Watson & Wilkinson (1999) used Escobar's quote to stir up the politics (unequal power relations) of spatial planning and to introduce an argument for a more integrated, and less politically problematic approach to spatial planning in South Africa. It is with this in mind that we deliberately use the same quote to inquire why so little has changed since Spiegel et al. delivered their argument in 1999.

In this article, Town and Regional Planning theory and anthropological approaches are fused together in an attempt to consider a more integrated approach to spatial planning, not "for", but "with" poor South Africans. The research draws on a case study based on Ave weeks of participant observation (the anthropological method of 'hanging out' (Spiegel et al., 1999: 180) and participating in people's everyday lives) in Marikana informal settlement, Potchefstroom, South Africa, in which people resorted to what was locally referred to as "DIY (Do It Yourself) formalisation" in a response to the denial of service delivery from the state. The case study considered water provision to poor citizens and provided an emic (insider) understanding of the current water reality of South Africa's urban poor. It also created a framework for considering broader spatial planning questions relating to planning approaches, community involvement, delineation of social power, and context-based needs. The case study illustrated that people living on the margins of South African cities are often creative and innovative in designing liveable space for themselves. It also illustrates that poor residents are well equipped to plan their living spaces and have sustainable and practical solutions to problems. However, lack of adequate resources often limit the full realisation of these ideas.

This research thus argues that, when considering spatial planning for the poor, both top-down and bottom-up planning approaches are problematic, since both reinforce unequal power relations between planners and poor citizens. The research furthermore argues in favour of context-sensitive spatial planning for the poor and that planners need to become more attentive to, and supportive of local solutions to planning and infrastructural concerns - this is where anthropology proves to be of valuable assistance. The article proposes the preposition 'with' in conjunction with 'planning' to argue that a 'planning with' approach to spatial planning for the poor in South Africa can contribute towards addressing the concerns mentioned above and provide a more integrative and sustainable approach to spatial planning for the poor. This article does, however, not provide a generalizable approach, as arguments are based on a singular case study. The research aims to provoke thought about the possibility of a different, more inclusive approach to planning for the poor. Accordingly, a conceptualisation of the notions of 'spatial planning' and 'planning with' is provided.

2. THE NOTION OF SPATIAL PLANNING

The profession of planning evolved from a designing art to a management and social science (Zhang, 2006: 12) that is now confronted with ever balancing the "protection of the green city", "the promotion of the economically growing city" and "advocating social justice" (Campbell, 1996: 296). The multidisciplinary nature of the profession led to the creation of different planning approaches, responding to social changes within a particular period of time (Zhang, 2006: 9). Spatial planning thus evolved as a context-specific applied science.

As such, spatial planning is considered the management of change, a political process whereby a balance is sought between all interests involved. Spatial planning is tasked with land-use decision-making, and resolving conflicting political and social demands on space, while protecting the earth's generative capacity.

Spatial planning in South Africa has a complicated and problematic colonial history in which land was used politically to disempower and suppress people classified as 'non-white' (the homeland system and the 1913 Land Act specifically come to mind in this instance; Magubane, 1979). Land - and the spatial planning thereof - is not less political or problematic in postcolonial (or post-apartheid) South Africa. Land-use decision-making and the conflicting demands for space imply politics and therefore unequal power relations (Njoh, 2009; Parnell & Mabin, 1995; Spiegel et al., 1999).

Njoh (2009) and Spiegel et al. (1999) similarly argue that urban planning is a political tool of power and social control, especially when it is practised 'top-down'. A 'bottom-up' approach has been offered to counteract unequal power relations; yet this article argues that a bottom-up approach is equally problematic, as it implies unequal social positions (those 'at the bottom' and those 'at the top').

This article argues rather for a 'planning with' approach that is grounded in anthropological understandings of space and cities as 'meshworks' (Ingold, 2017: 10), whilst simultaneously drawing on literature and concepts in spatial planning in an attempt to make the argument for a 'planning with' approach 'policy relevant' (Spiegel et al., 1999: 182-186).

2.1 Conceptualising 'planning with'

Over the past Ave years especially, anthropologists have become increasingly excited about the preposition 'with' and its possibilities for opening up conversations about power relations and how we might deal with unequal power relations (Haraway, 2016; Ingold, 2017; Puig de la Bellacasa, 2011; Puig de la Bellacasa, 2012; Tsing, 2016). Ideas of 'doing with' have been especially prominent in environmental anthropology and in thinking about how we might possibly counteract global warming and mass extinctions by becoming attentive to our entanglements and interdependence with both living and non-living others (Haraway, 2016; Van Doorn, 2014; Van Doorn, 2015). As a scholar in feminist studies, science history, developmental biology, and philosophy Haraway has long argued that nothing can exist without 'existing with' and, more importantly, that nothing can become without 'becoming with' something else (Haraway, 2003; Haraway, 2008; Haraway, 2010; Haraway, 2016).

Applying Ingold's (2017: 10) notion of a 'meshwork', in which "everything tangles with everything else", to South African cities, we vividly perceive that the suburban South African city is contingent upon the maintenance of its margins and the exploitation of the labour contained within these margins. Suburban houses, gardens, municipal service delivery, factories and businesses are maintained by labour sourced from the margins of the cities - historically, the homelands; contemporarily, the townships and informal settlements (Cock, 1980; Parnell & Mabin, 1995; Magubane, 1979; Murray, 2009; Njoh, 2009).

South African cities and informal settlements have 'become with', making the South African city a 'meshwork' (Ingold, 2017: 10) of problematic relationships in which the poor (those not able to contribute meaningfully to the market economy) have become disposable (Murray, 2009) and are left to either 'make do' or die in the margins of our cities where they are left without service delivery or formal, government housing (Gandy, 2004: 368). The South African Constitution of 1996 dictates that all citizens have the right to 'proper' living conditions, including safe housing, clean water, safe energy supply, sanitation and garbage removal services (RSA, 1996). Yet, many of South Africa's poor such as those living in Marikana informal settlement, on which the case study of this paper is based, are denied their rights to basic service provision and to access South African cities. It is evident that we cannot continue doing 'business as usual'.

As a scholar in science and technology studies, Puig de la Bellacasa draws on Haraway's ideas of 'becoming with' and expands these to illustrate that it is important to not only 'do with' others but also 'think with' them (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2012). In this article, the authors employ Haraway and Puig de la Bellacasa's ideas of both 'doing with' and 'thinking with' and expand them to argue that urban spatial planning for the poor in South Africa should be a practice of 'planning with', in which both the thinking and the doing (or implementation) processes of spatial planning should happen 'with' the people and places spatial planners are planning 'with'. This article argues that such approaches enable 'co-respondence', the ability to respond to one another (Ingold, 2017) between planners and poor citizens in the spatial planning process.

2.2 'Planning with' challenges and opportunities in South Africa

In 1999, two South African planning academics (Vanessa Watson and Peter Wilkinson) joined forces with an anthropologist (Andrew Spiegel) to run a project called, 'African population movement in metropolitan Cape Town and its implications for housing policy' (Spiegel et al., 1999: 177). The purpose of the project was to make use of interdisciplinary approaches to gain an in-depth understanding of the housing experiences and expectations among low-income Black South Africans in metropolitan Cape Town, in order to better inform, and make more sustainable housing policy in the area (Spiegel et al., 1999: 177).

Spiegel et al. (1999: 180) argued that anthropological methods could assist in gaining an emic understanding of people's experiences with, and expectations of housing and housing policy, since anthropological methodology involves 'hanging out' with people. The authors, however, recognised that this interdisciplinary approach would not be unproblematic, mostly since it might be difficult to translate anthropological findings into policy-relevant solutions. Yet, they argued that anthropology does have something to bring to the table, as anthropology not only enables emic understanding, but also advocates the acknowledgement of local knowledge (Spiegel et al., 1999: 188) - an acknowledgement central to the argument for 'planning with'.

Despite the vision and various measures to ensure integrated planning, the trajectories of unbalanced development, inequity and unsustainable space are still evident in South Africa as a result of the apartheid legacy. Various informal and traditional land-use development processes are still poorly integrated into formal systems of spatial planning and land-use management (SPLUMA, 2016: 2). This inhibits the sustainability of urban planning solutions, service delivery and land use. Why has so little changed since Spiegel et al. made their convincing argument for interdisciplinary and integrative planning approaches in 1999?

Part of the problem is the silo approach to spatial planning, where cooperative governance structures often struggle to work horizontally across the various national-level silos (PDG, 2012: 19), despite the objectives provided by the Integrated Development Plans (IDPs) and the Spatial Development Frameworks (SDFs). The typical fragmented silo-management approach leads to unsynchronised planning approaches where planning at a city-wide level (such as strategic or spatial planning) is often not coordinated with infrastructure planning that is being carried out at a line-function level (as with water service departments).

Delays in finalising planning and regulatory instruments with legal force further inhibit the potential for cross-departmental coordination and integration (Fisher-Jeffes, Carden, Armitage, Spiegel, Winter & Ashley, 2012: 902).

2013 saw the enactment of the new Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (SPLUMA), which established a new focus for planning in South Africa (SACN, 2015: 4), especially with sections 7(b) and 7(d) of SPLUMA referring to "the principle of spatial sustainability" and "spatial resilience" and enhancing the relationship between spatial planning and other categories of planning. SPLUMA now enabled possibilities for integrative, transdisciplinary planning approaches (Wilhelm-Rechmann & Cowling, 2013: 2). The question remains as to how to realise such integrative planning approaches within the South African context and diverse South African cities. In an attempt to introduce the "how" of "planning with", a case study of Marikana informal settlement was used. The data was gathered by means of qualitative participant observation in an ethnographic fieldwork study which offers valuable insights in support of the 'planning with' approach.

3. PLANNING WITH POOR CITIZENS: THE MARIKANA CASE

3.1 Study area

Marikana is an informal settlement located on formally undeveloped land, in the North West province of South Africa. With no infrastructure or municipal service provision, no storm-water drainage and frequent ground erosion due to heavy rainfall, the settlement has grown to an estimated size of approximately 1km in length and 300m in width.3

Marikana settlement falls within municipal ward 17 for formal governance by the Tlokwe/ NW 405 (now called 'JB Marks') municipality. It does not, however, receive any service provision from the municipality, since the area is not recognised as a formal neighbourhood. It is for this reason that residents decided to form their own residential committee which took care of all correspondence between ward councillors and residents. The residential committee, consisting in 2016 of six men, also took care of internal governance and administration of the settlement. It also initiated and administrated the Do It Yourself (DIY) formalisation plan - a plan that entailed the DIY measurement and layout of stands and streets throughout the settlement and the auto-construction of twenty communal taps.

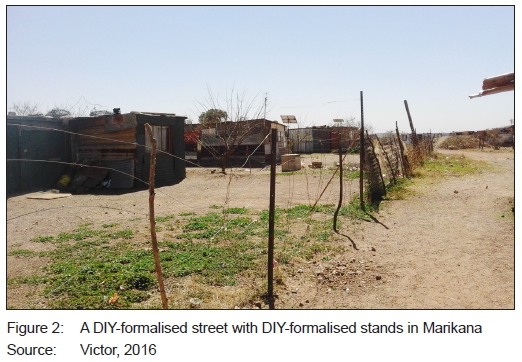

In Marikana, roughly 1600 corrugated iron 'shacks' (as the only viable housing option) have been erected (Leshage, 2017: 4). The Marikana area can be easily identified by the 'scattered' layout, in contradiction to the Government's formalised Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) neighbourhoods on the western and southern sides. DIY formalisation is visibly evident in Figure 1, in which streets and rectangular stands are visible in the DIY-formalised area on the right of Figure 1. By September 2016, roughly 60% of the settlement was DIY formalised.

In South Africa, when settlement occurs on unauthorised land or in the case that the settlement may not be formalised and developed in situ, due to environmental risks or private ownership of the land, the state, in conjunction with the local government, needs to provide suitable, formally developed land for the relocation of settlers (Huchzermeyer, 2006: 46, 51). However, relocation or in situ development may take up to 15 or 20 years, leaving people to live in 'shacks' without adequate infrastructures, including, water, sanitation and housing, for a considerable period of time.

Unwilling to wait 15 to 20 years for either relocation or state formalisation of the settlement, residents implemented what was locally referred to as "DIY formalisation", a strategy aimed at "meeting the government halfway" with service delivery and formal 'development' of the settlement. During DIY formalisation, residents, under leadership of the residential committee, expanded their settlement to the east, in order to accommodate the layout and measurement of double-lane streets and 18m by 20m stands to resemble the gridiron layout of formal, suburban or RDP neighbourhoods. This was the first stage of DIY formalisation (see Figure 2 for an illustration of a DIY-formalised area).

To accommodate their right to water and to illustrate water's ability to delineate social power (Gandy, 2004), Marikana residents used an innovative DIY formalisation plan: they installed communal taps as a pragmatic local solution to service delivery for their settlement. Residents' DIY formalisation process, which they undertook to make their settlement more liveable, is a good example of insurgent city planning. It was used as a case study to propose a 'planning with'-the-poor approach.

3.2 Research process

Utilising a qualitative research approach, participant observation was used as a tool for producing data. Participant observation is a method of 'doing research with', as it involves the researcher in a variety of activities over an extended period of time that enables him/ her to observe people in their daily lives as well as participating in everyday practices. The process of conducting this type of fieldwork involves gaining entry into everyday life in the settlement, participating in different activities, sometimes conducting formal interviews, and, more often, casual conversations, and keeping organised, structured field notes (Kawulich, 2005: Art. 43; Clifford, 1990: 51-53).

As this study aimed to provide a fair representation of an informal settlement, a case study with participant observation as method has proven to be beneficial, as it provides opportunities for viewing and participating in everyday events (Marshall & Rossman, 1995; DeMunck & Sobo, 1998: 43; DeWalt & DeWalt, 2010: 259-260). Participant observation, as a method of "hanging out" (Dewalt & DeWalt, 2010: 261) and 'doing with' not only enables a researcher to enjoy intimate relationships with his/her research companions, but it also allows an emic (insider) perspective on people's daily lives and, therefore, enables a fair representation of research participants in writing (Clifford, 1990: 51).

The case study captured in this article is based on a reflection of Ave weeks' participant observation conducted in Marikana informal settlement, approximately 15km outside the city centre of Potchefstroom, South Africa, from August 2016 to September 2016. During these Ave weeks, the researcher walked from house to house through the streets of Marikana with Skhokhorito, her main informant and solicitor between her and the residents. In walking through Marikana's streets, the researcher also often 'hung out' (Spiegel et al., 1999: 180) at the 20 auto-installed communal taps and inside residents' houses where she conversed with dozens of residents about their experiences of life and specifically about water provision to their settlement.

Apart from this research method being the primary anthropological research method, 'hanging out' at the 20 communal taps and having casual conversations with residents about daily life enabled the researcher to gain an empathetic and realistic understanding of everyday life in Marikana, as the method ensures vast sensory experience. It was only from daily observing and participating in everyday water practices in the settlement that the researcher was able to understand both the lack of 'proper' infrastructure and the creativity of DIY-installed infrastructure, ensuring a fair written representation of Marikana's infrastructural realities. This method also enabled the researcher to gain residents' trust and ensured a sustained and, therefore, ethical relationship between the researcher and the residents. This research was conducted for the purposes of an honours dissertation in Social Anthropology at the North-West University (Victor, 2016).

Data was collected through a field study considering the water provision to Marikana from both a spatial planning and an anthropological perspective. As such, the current water reality of South Africa's urban poor was central to the point in case of considering broader spatial planning questions relating to planning approaches, community involvement, delineation of social power, and context-based needs. Upon reflection of the ethnographic fieldwork conducted in Marikana, and considering the theoretical background in terms of 'planning with' approaches, broad themes of the possibilities of 'planning with' were identified through a coding process considering environment, social, economic, political, and planning issues.

4. OBSERVATIONS

4.1 Environmental considerations

Even after installing more accessible water in the form of twenty communal taps during DIY formalisation, sanitation posed a limit to DIY infrastructure, since residents did not have the resources to auto-install proper sanitation infrastructure. Residents in Marikana made use of the bucket system (this is an embarrassing system, since one needs to walk down the street with a full slop bucket to empty it in the bush), auto-installed pit latrines (these pose risks such as that children can fall in them and die of injury, suffocation or drowning), or defecated in the bush (this is also dangerous, since women were frequently assaulted or raped).

In 2016, shortly before the municipal elections, local government donated twenty-five chemical toilets, for approximately 3.000 to 4.000 residents, to Marikana. The toilets have not been consistently cleaned by the consulted cleaning company and many have since become faulty and maggot-breeding nests (Leshage, 2017: 4). Residents argued that running-water connections to every household would simplify proper sanitation installation; they volunteered to auto-install this infrastructure if local government provided funds or materials. Since no municipal budget is available for Marikana, this has not yet realised (Victor, 2016: 15).

Some residents, who could afford it, did auto-construct neat pit latrines. The walls of these latrines were constructed with galvanised iron plates and the interiors often assembled from old ceramic toilet bowls or tin cans with wooden lids. Residents often tiled the floors of their latrines with salvaged tiles and made a toilet brush and some bleach to stand in the corner. During a visit to Marikana, Thembisile, a member of the residential committee, proudly showed the researcher inside such a latrine, and rhetorically asked, 'Is this not much better' than the dirty chemical toilets provided by the local municipality?

Residents were creative in the sense that they shared these pit latrines with neighbours. The latrines were usually locked and the keys were given to neighbours and family members who received permission from the constructor of the toilet to make use of it. All users of the latrines were, therefore, also responsible for the maintenance and cleaning of the latrines. Even though these shared, auto-constructed pit latrines might have partly solved the problem of open defecation, it did not solve the problems of airand underground water pollution. Neither did the donated chemical toilets. Residents often complained about the foul smell and argued that they would insert and maintain the infrastructure themselves, if local government gave them permission to insert flushing toilets and supported them in acquiring construction materials.

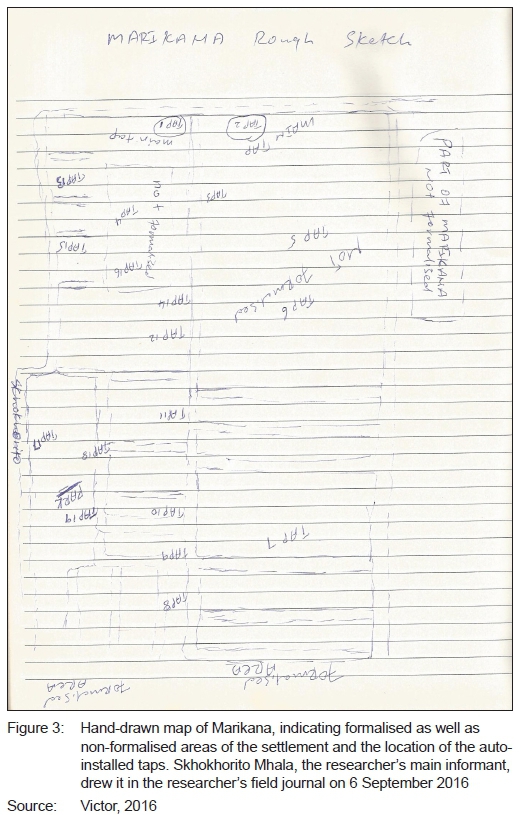

To further make everyday life in the settlement more liveable, residents planted vegetable and flower gardens as well as shade trees at measured stands throughout the settlement, creating green spaces to give "life" to the ground, to provide shade and to minimise ground erosion linked to rainfall, since no storm-water drainage is installed in the area. Some residents made use of large garbage bins to collect rainwater for watering vegetable gardens. Residents also aspired to create a 'community park' by watering it from a JoJo tank donated by local government in 2014 (on the map in Figure 3, Skhokhorito marked the space for the aspired park).

The JoJo tank was at first received with some discontent, since the water contained in such a tank is not suitable for drinking, and residents argued that the tank did not address their most pressing water issues (safe running water for all residents). One female resident decided to creatively utilise the provided tank to benefit local residents, and used it to water a large vegetable garden at her house, from which food is provided to residents.

The residents' reaction to both the donation of the JoJo tank and the chemical toilets shows that needs and context (the layout and geography of the area, economic circumstances of residents) and residents' attitudes towards local governments and infrastructures should be understood and not forestalled. The top-down provided infrastructure (JoJo tanks and chemical toilets) did not serve the residents' needs; rather, it resulted in feelings of discontent among residents. Planning and thinking 'with' residents would have provided much more sustainable and practical solutions such as closer, piped, running water and, by implication, 'proper' sanitation services that could be maintained by residents.

The Marikana case did, however, illustrate the creative initiatives of water harvesting and basic "green approaches" implemented by the residents themselves (e.g., planting trees and gardens). These creative urban greening initiatives suggest the intrinsic human need to survive and sustain resources for future survival. Education regarding sustainable planning approaches could benefit South Africans in every economic class. Such approaches are especially important for poor residences where service provision is considered a scarce commodity reserved for the financially privileged.

These examples show that Marikana residents experience green spaces as important and considered environmental issues while DIY planning their settlement. Ground erosion, food shortages and foul smells, due to 'improper' sanitation, were some of the largest environmental concerns which residents counteracted by means of constructing and maintaining auto-constructed pit latrines, planting white stinkwood trees, fruit trees, where possible, and vegetable gardens. Residents also understood the importance of a green space for children to play and have planned the community park in order to create such a space. At present, Marikana is still experiencing drought, erosion and food shortages, but residents continue to create green spaces and plant trees; an area for a park has been identified and cleared.

It was evident that apart from environmental concerns, urban planning should also address social issues. In the next section, the social considerations of 'planning with', as it pertains to the case study will be discussed.

4.2 Social considerations

In July 2013, residents received permission from the local DA government to gratuitously connect water pipes to, and draw water from the water pump which also serviced the nearby RDP neighbourhood of Bram Fischer.4 Local government and the South African National Civic Organisation together supplied 500m of 50mm pipes (eNCA, 2013; Victor, 2016: 13), which residents then auto-installed along the main street, namely Hoofstraat, and another broad street that residents had already laid out.

The layout of plots and streets simplified the installation of DIY water infrastructure and, in the course of time, neighbouring Marikana residents resourcefully donated money to a collective pool that was used for the purchase of pipes, T-junctions and other tap mechanisms, in order to expand the DIY water infrastructure network and to provide closer running water to more households. In total, 20 communal taps were auto-installed by the end of 2016. Even with the 20 communal taps, many residents still walked further than 200m (the minimum accepted distance from a water source), in order to access running water for basic household tasks such as cooking, cleaning and doing laundry. Figure 3 is a rough hand-drawn map provided by Skhokhorito (the author's main informant), illustrating the location of the auto-installed taps (no official map is currently available).

As mentioned earlier, water has the ability to delineate social power (Gandy, 2004). Therefore, the issue of water provision is not only an environmental or survival issue, but also a social one. Residents' abandonment by the state, which is so evident in the state's denial of service delivery or housing provision, sends a clear message that the state does not care for citizens who cannot contribute to the market economy. The denial of water provision, in particular, is socially damaging, as water is the most essential resource for life. In Marikana, residents thus decided to auto-install communal taps in an insurgent attempt to negate the state's enforcement of unequal social power and to claim their "right to have a daily life" (Holston, 2009: 246).

Skhokhorito further mentioned that DIY formalisation was a way to "meet the government halfway" with service and housing delivery to Marikana. In this statement, Skhokhorito draws on a fundamental construct of social life: reciprocity, and, more specifically, balanced reciprocity. Nanda (1994: 210) argues that balanced reciprocity enables social relationships to be maintained and regarded as equally worthy. Residents' claim that DIY formalisation is a strategy aimed at "meeting the government halfway" is an indication of the residents' conceptualisation of a good social relationship with local government. The statement is not only a claim that residents have brought something to the table, but also a claim that they expect something in return, in order to maintain good relations with local government.

In terms of maintaining good social relations, it is further important to note that the pressure of providing basic service delivery (such as water) to poor citizens should be understood from the perspective of survival. Citizens in need of water services do not have the luxury of time and cannot wait for government to respond. The drive to survive often leads to 'unauthorized' service usage, but also to innovative and resourceful, often very sustainable solutions to everyday problems that should not be criminalised (Robins, 2014: 497). In addition, citizens in need of basic services often do not have the luxury of sufficient funds to meet all their infrastructural needs; yet residents in Marikana made savvy solutions to partly address this issue.

'Planning with', as an approach with the aim of negating unequal power relations (as opposed to 'planning for' or even 'planning against' poor citizens), has vast potential to ensure good social relations between poor citizens, planners and government officials. 'Planning with' further has the potential to address economic issues, as will be discussed accordingly.

4.3 Economic considerations

Since the residents themselves installed the water infrastructures, they also took the responsibility, or perhaps to use Haraway's (2016: 68) notion "response-ability", for maintaining these infrastructures. Leakages caused by overuse of the taps, as over one hundred people depend on one communal tap, and the consequent breakage of the tap mechanisms were quickly fixed by residents in innovative ways, such as using forked sticks and wire (see Figure 4).

There are two main economic considerations as well as two arguments for 'planning with' that become apparent in this instance. First, in areas such as Marikana, where poverty and unemployment are rife, 'planning with' provides opportunities for cost-effective infrastructure construction. Residents in Marikana made use of the most economically friendly strategy to make their settlement liveable in their collection of shared funds. Residents from neighbouring households would donate money to a collective pool from which funds were drawn in order to 'pull taps closer' to more households. The installation of these collective taps was often accompanied by organised events, during which men did the hard labour of installing the taps, while women prepared a celebratory meal.,

After the taps were installed, residents then shared in a meal, usually of pap, marog (a vegetable similar to spinach) and some meat, when possible. Skhokhorito once noted that some residents were annoyed by 'freeloaders' (people who did not participate in the construction of the infrastructure) who often joined in the meals, but that, due to shared poverty, he could not show them away from the meals. The collectively planned auto-construction of taps, therefore, not only enabled residents to install taps in cost-effective ways, but also ensured an affordable meal and wide distribution of food (an often scarce resource) because they planned and did 'with' one another.

A second argument for the economic advantages of 'planning with' is that, if local governments could plan and do 'with' residents, residents would take ownership of the infrastructure (as presented above) and maintain it, thus ensuring cost-effectiveness, since leakages and breaks were fixed quickly and creatively with limited resources. The auto-construction of taps, however, addressed not only environmental or social concerns, but also political ones.

4.4 Political considerations

DIY formalisation and the auto-construction of taps were not only technologies of survival, but also political strategies. Skhokhorito explained that residents of Marikana refused to wait 15 to 20 years for government formalisation and decided to take matters into their own hands, in order to match local government politically. In a casual conversation, Skhokhorito explained that the agenda of communal tap installation was to install a tap at every formalised stand. Skhokhorito explained that, if every person had a tap at his/her stand, water usage might increase and the municipality would suffer a financial loss. In order to avoid financial loss, Skhokhorito argued that the municipality would have to bill residents for water and, therefore, have to install water metres. Water metres can only be installed at stands with addresses and, in this manner, residents hoped to acquire title deeds to stands along with some security - a politically savvy plan indeed (Victor, 2016: 19-20).

In this sense, DIY formalisation was an insurgent claim to citizenship, the city and its infrastructures (Holston, 2009: 246-250). DIY formalisation was also a fervent protest to government's abandonment of residents and its reduction of informal settlement life to 'bare life' - politically unqualified life (Agamben, 1998: 1-3). DIY formalisation was a claim not only to physical life, but also to political life. As Skhokhorito explained, it was an act of 'active citizenship' - an act of actively questioning power relations between residents and city officials.

In terms of political considerations for a 'planning with' approach, it is important for planners and government officials to be attentive to power differentials and to the inequalities embedded in planner-poor citizen relationships. It is important for planners to be attentive to how poor residents experience top-down approaches to urban planning and to how they experience urban planners. Planners should ther also be attentive to, and supportive of politically savvy local solutions, such as the auto-construction of taps as part of larger plans to acquire housing certainty. Such solutions are creative planning strategies which planners might And valuable in buying into.

4.5 Planning considerations

The case study of DIY formalisation in Marikana informal settlement shows that there are many planning considerations that are valuable and useful to contemplate. Many of them have been mentioned earlier: laying vegetable gardens and planting trees at DIY-measured stands to address environmental concerns; the use of water and water infrastructure to structure a previousl formally unstructured space and to bring into question social issues of power delineation, and the use of infrastructure and space measurement to make political claim to the city and its infrastructures (Holston, 2009: 246-250).

Residents in Marikana took specific care to plan their settlement according to existing, standardised government housing plans. These plans included the measurement of streets sufficiently broad to accommodate two vehicles and emergency vehicles and to simplify water and electricity connection; the measurement of stands according to standard government housing stand size (residents did, however, compromise on stand size, in order to illustrate their willingness to "meet the government halfway"), and the allocation of specified areas for garbage (Huchzermeyer, 2006: 57).

Residents also drew on ideas of the "clean city" (Gandy, 2004: 367) in both their allocation of dumping areas far from residential areas and their organisation of pit latrines as far away from houses as possible. Further, residents organised their settlement in a gridiron layout, similar to suburban South African neighbourhoods. This illustrated both an aspiration for "modern city life" (Ross, 2010: 18-44) and a claim that life in Marikana was in fact "respectable" (Ross, 2010: 35), "modern city life" (Njoh, 2009: 307) - once again a politically savvy planning move.

Residents in Marikana utilised politically savvy DIY approaches of spatial planning to make their settlement more liveable, to claim their right to access to the city, and to transform the margin of Potchefstroom into "their place in the city" (Holston, 2009: 247; Victor, 2016: 20). The authors of this article thus argue that spatial planning in Marikana was strategic and clever, and that these planning strategies could have amazing and long-lasting effects if implemented with planners and government officials.

Based on these findings, the value of 'planning with' could be realised, as it relates to the notions that delineation of social power does not follow a logical order where survival is concerned, that needs cannot be forestalled, but should be context based, that DIY solutions enhance ownership and accountability, and an understanding that environmental education could benefit all classes.

5. THE VALUE OF 'PLANNING WITH' FOR THE SOUTH AFRICAN CONTEXT

The Marikana case study identified valuable lessons that should be considered when planning in the South African context and especially when planning with poor South Africans. Residents in Marikana offered an especially valuable lesson in planning and providing water provision to poor settlements, as much of DIY formalisation centred on the auto-construction of communal taps and ensuring closer, more accessible running water to residents. Residents in Marikana came up with a pragmatic and sustainable solution to water issues in the settlement by communally collecting money for tap appliances, providing labour for the auto-construction as well as the maintenance of taps, and laying out roughly 60% of their settlement in a gridiron nature, in order to simplify pipe connection.

This article thus argues that such local solutions must be taken seriously and that planners should buy into such solutions and 'plan with' poor citizens, in order to And practical and sustainable solutions to service and housing provision to the South African poor. The 'planning with' approach, in this sense, can contribute to environmental, social, economic, political, and broader planning considerations, especially as it pertains to solutions to water provision for the poor in a water-scarce South Africa, as explained accordingly.

5.1 Environmental considerations

Rapid urbanization, significant resource shortages and fragmented institutional structures are some of the issues that contribute to the complexities of water management in South Africa (Carden, Fisher-Jeffes, Coulson & Armitage, 2012: 10). South Africa is a water-scarce country, with an annum rainfall of 464mm (WESSA, 2012), which is half the global average (WWF South Africa, 2013: 55). The distribution of water compounds matters, with 43% of South Africa's total rainfall occurring on only 13% of the land (Writer, 2015), while 8% of South Africa's land area produces 50% of the surface water. With 98% (Turton, 2008: 2) of surface water resources fully accounted for (Fisher-Jeffes et al., 2012: 907), South Africa relies highly on significant water transfers from neighbouring countries (Water Resources Group, 2009: 20).

Another crucial consideration is the considerable service backlogs relating specifically to water management. The 2011 South African Census (Statistics South Africa, 2012) revealed that 46.3% of households in South Africa have access to piped water, but that 14.1% had below the national standard for basic water supply (RDP-acceptable level). The majority of these households, related to 27 District Municipalities, were mainly rural, generally in remote areas and thus difficult to service and with high associated costs (Rodda, Stenström, Schmidt, Dent, Bux, Hanke, Buckley & Fennemore, 2016: 457). Similar trends were visible for the sanitation supply backlog, where 31.3% of households had below the national standard for basic sanitation in 2011 (Statistics South Africa, 2012). On the one hand, political pressure to provide full waterborne sanitation as 'basic level' sanitation is further impacting on the cost and timeously delivery of these basic services and has an impact on overall municipal viability. On the other hand, waste-water treatment poses a further threat to the water-services sector as Waste Water Treatment Works (WWTW) are generally poorly capacitated (Mema, 2010: 4). According to the 2011 Green Drop Assessment (Department of Water Affairs, 2011: 14), 317 (38.6%) of all WWTW was in a critical state.

A 'planning with' approach could ensure that the scarce resources are being protected and used optimally, especially when public buy-in is aligned with infrastructure and service provision. Drawing from the Marikana case study, 'planning with' could be the catalyst that enables creative planning approaches where local solutions could be provided for increasing planning challenges. Marikana residents' DIY formalisation plan is one such local solution that could prove both economically sustainable and environmentally friendly, especially if local government were to provide support for the DIY construction and maintenance of infrastructure.

If local government were to plan for running water and 'proper' sanitation with residents, the issues of sewage-polluted air and water could be addressed. Similarly, if local government were to plan gardens with residents, the issue of water erosion could be addressed, whilst facilitating other benefits such as food provision and enhancing the objectives of broader green infrastructure planning.

5.2 Social considerations

South Africa has an idiosyncratic social 'meshwork' (Ingold, 2017: 10), with various sensitivities resulting from the apartheid era. Due to widespread poverty and inequality in the country, many poor, previously disadvantaged citizens are left without any service delivery and essential resources necessary for survival and 'proper' living (Ross, 2010) such as housing, water and sanitation, even though delivery of these services and resources are compulsory according to the South African Constitution of 1996. In an attempt to rectify previous social injustices, the national government promised to provide free basic services to the poor (Fisher-Jeffes et al., 2012: 905), resulting in, for example, water services now being considered more of a social rather than an environmental or economic concern. In addition, the lack of technical capacity and low staff skills levels, in the majority of planning-related departments, are further complicating the matter.

As such, various municipalities are unable to provide sustainable services or run a successful and sustainable service business because of lack of capacity and skills. In their distrust of local government to provide them with 'proper' services and infrastructure, residents in Marikana established the 'residential committee' to act as an authoritative form of governance within the settlement. If local governments were to recognise the value of such DIY approaches to governance, and plan with local committees, 'planning with' would enhance social cohesion and social capital. This would, in turn, reinforce the importance of social sustainability as core objective of planning initiatives, as poor citizens would become encouraged to take ownership of the planning, implementation and maintenance of the services and infrastructures provided (as was the case with auto-installed taps in Marikana).

5.3 Economic considerations

According to the South African non-financial census of 2013 (Statistics South Africa, 2013), 5.27 million households received free basic water, and 3.10 million households received free basic sanitation. Currently, no municipality in South Africa charges for storm-water services (Fisher-Jeffes et al., 2012: 903), thus placing more pressure on other sources of income to finance these departments. As such, the provision of storm-water management is largely funded from property rates, implying that storm-water departments have to compete with many other departments (housing, transport, and so on) with often more pressing needs, when advocating for funding. As a result, most of the storm-water departments in South Africa are chronically underfunded, with some estimated to be receiving as little as 10% of what is ideally required for maintenance (Carden, Fisher-Jeffes & Armitage, 2013: 9). A 'planning with' approach might be the link to support the inclusion of more green infrastructure approaches in South Africa, where the natural environment is optimised to support and, in some instances, fulfil the function of grey infrastructure. Marikana is a good example. Residents collectively accumulated money for infrastructure to provide in the needs of the broader community. Such initiatives prove to be positive in terms of the notion of green infrastructure which relies on the buy-in of local residents, especially considering maintenance, and could be well suited within the 'planning with' approach.

5.4 Political considerations

Misperceptions regarding needs and values are probably the greatest reason for not achieving sustainability. Governments often focus primarily on providing basic services to all people, some of whom live in inhumane conditions, while neglecting to place equal emphasis on the environment and the social value that environmental sensitivity might have on both the short and the long term. In addition, governments perceive the unknown to be risky and would prefer traditional approaches, services or infrastructure (Cilliers & Cilliers, 2016). 'Planning with' approaches could sensitize political agendas to include actual local needs and values and seek ways in which to realise such as part of broader spatial planning.

In Marikana, residents decided not to passively wait for local or national government to provide them with 'proper' infrastructures and housing, since they were aware that this might take 15 to 20 years to realise. Instead, residents enacted DIY formalisation in an insurgent claim to citizenship (Holston, 2009) and political life. Residents called DIY formalisation, 'active citizenship'. With DIY formalisation, residents vehemently conveyed the message that they refuse to die a political death and that they refuse to be rendered disposable by local authorities.

'Planning with' has the potential to address unequal power relations between the state, planners and poor residents, as it is neither a bottom-up nor a top-down approach to planning. Instead of waiting 15 to 20 years for service provision, residents in Marikana managed to DIY formalise their settlement within months. If planners and government officials buy into DIY solutions to service and housing provision, these issues might be rapidly and simply solved.

Residents of poor settlements should be actively involved when considering the provision of water and other infrastructure services, since they have, in many instances, realistic and sustainable solutions. The DIY installation of water infrastructure resulted in enhanced social cohesion, whereby residents provided funding and implementation to benefit a greater area, and enhanced accountability, whereby residents provided the necessary maintenance.

5.5 Planning considerations

Realising integrative planning approaches that are applicable to South Africa's diverse public is probably still the main planning challenge of post-apartheid South Africa, even though Spiegel et al. (1999) addressed this 18 years ago. Integrative planning considers different actors and sectors working together under a jointly designed agenda and re-aligning individual supply chains to produce a jointly defined objective (Van Huyssteen, Liebenberg & Gueli, 2007: 1). Integrative planning ('planning with') relates to cross-sectoral, but also inter-sectoral planning and management. As mentioned earlier, cooperative governance structures often struggle to work horizontally across the various national-level silos (PDG, 2012: 19), complicating the implementation of cross-sectoral and inter-sectoral planning.

Inter-sectoral planning is, however, posing further planning challenges. A case study of four major metropolitan municipalities (Cape Town, eThekwini, Johannesburg and Tshwane) in South Africa revealed that, in all four of these municipalities, the management of storm water was separated from that of water and sanitation (Fisher-Jeffes et al., 2012: 907). As water and sanitation departments generate more income than storm-water departments, the former had effectively more power in the city structure and decision-making process (Fisher-Jeffes et al., 2012: 908), worsening the integrative ambitions. The lack of integrated planning considerations is evident in the physical environment, where, according to the WWF South Africa (2013: 50), 37% of water is lost once it enters the engineered distribution systems (non-revenue water) of South Africa. Water management and related issues are encapsulated under a broad national planning umbrella, but not prioritized as part of spatial planning policy formulation. As such, the newly enacted SPLUMA refers to "water" only three times, and zero times within the SPLUMA regulations. The misplaced focus of spatial planning is questioned in this regard, where infrastructure-focused targets have neglected longer term sustainability requirements.

In 'planning with', planners and local residents might be able to create practical and sustainable solutions to the types of infrastructures or services needed in a specific place and how these infrastructures or services might be environmentally, politically and policy sensitive. At the end of 2016, residents in Marikana appealed to local government for trees that residents could plant in order to provide both shade and a solution to ground erosion, due to rainfall, in the settlement. Between December 2016 and September 2017, 60 Celtis Africana (white stinkwood) trees have been granted to Marikana and planted at DIY-formalised stands where residents can easily water them regularly. Although the trees may grow to provide shade, residents wondered why local government had not provided them with fruit trees such as apricot and quince that also grow large and can provide shade, a solution to ground erosion and food to the people living in Marikana who are mostly unemployed and hungry. 'Planning with' would have enabled local authorities to become attentive to the residents' needs such as shade, solutions to ground erosion, and food. In return, such an approach would have resulted in an even more practical solution, probably more politically and environmentally sensitive.

6. THE WAY FORWARD FOR INTEGRATIVE PLANNING

The way forward for integrative planning ('planning with') in South Africa should, among others, contemplate the following issues:

• The received planning 'wisdom' (Watson, 2004: 252) and international best practices should be translated to the local context and take local needs and solutions into consideration. A local planning approach should be strongly linked to the socio-economic growth possibilities. Approaches in favour of integrative planning should support context-driven planning.

• Planning in South Africa should strongly focus on the social component, and less on the environmental component, justified in terms of equity, which entails being fair and specific, and providing people with what is contextually needed in order to grant equal opportunities, and provision of services to

all people (Fisher-Jeffes et al., 2012: 907). Such an approach calls for a social dimension to environmentally educate communities and address misperceptions of authorities regarding planning and service provision in general.

• 'Planning with' approaches should be included as part of mainstream spatial planning, integrated within different planning scales ranging from community-level planning to city-level planning. 'Planning with' equips both local residents and planners with "response-ability" (Haraway, 2016: 68). If residents and planners are enabled to "co-respond" (Ingold, 2017) to one another in as far as solutions to housing, environmental and service delivery issues are concerned, poor citizens and planners might become 'empowered' with one another, addressing, if still only partially, the legacy of unequal power relations left behind by colonial urban planning (Njoh, 2009; Spiegel et al., 1999). The planning vision should be refocused in favour of long-term, sustainable practices. 'Planning with' can be an instrument to develop social and intergenerational equity, as it has the potential to 'connect' spatially divided communities and settlements. Such an approach and regional strategy should facilitate cross-sectoral and transdisciplinary integration, highlighting the links between policymaking and service delivery at national, regional and local levels. The local context and challenges should be understood, and actual public needs should be identified with great caution, as this will result in enhanced ownership and accountability of the infrastructures and services provided. Environmental education should underlie all such approaches. 'Planning with' approaches will enable and motivate people to sustain not only the infrastructures, but also the co-created relationships formed with planners and vice versa, enabling possibilities for further planning, thinking and doing with.

7. CONCLUSION

There is a need to rethink spatial planning in South Africa, especially as it pertains to the South African poor. This article argues that both top-down and bottom-up approaches to spatial planning are problematic, since both imply unequal power relations and reinforce the problematic colonial legacy of spatial planning in South Africa (Njoh, 2009; Parnell & Mabin, 1995). This article thus proposes a 'planning with' approach to spatial planning in South Africa, by making use of anthropological views and theory 'with' spatial planning theory and approaches in an interdisciplinary, complementary and integrative approach, drawing on the approach proposed by Spiegel et al. (1999) of an anthropological understanding of cities as "meshworks" (Ingold, 2017: 10) - spaces in which people (of different economic classes), environments (resources, plants, animals, and so on), infrastructures (both grey and green), and policies (spatial planning policy, laws and rights) are entangled and co-exist. This article proposes 'planning with' as an approach that may take these entanglements into account and provide a less politically unequal approach to spatial planning for the poor. This article does not offer a generalizable solution to all planning challenges in South Africa, but aims to inspire planners, policymakers and anthropologists to And new ways of 'thinking with' (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2012) one another, as well as 'with' space in South Africa and 'with' the people who live in these spaces.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF.

REFERENCES

AGAMBEN, G. 1998. Homo sacer: Sovereign power and bare life. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

CAMPBELL, S. 1996. Green cities, growing cities, just cities? Urban planning and the contradictions of sustainable development. Journal of the American Planning Association, 62(3), pp. 296-312. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369608975696 [ Links ]

CARDEN, K., FISHER-JEFFES, L. & ARMITAGE, N.P. 2013. Integrating design, planning and management: Water-sensitive urban settlements: Water and wastewater. IMESA August 2013, Urban Water Management Group, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

CARDEN, K., FISHER-JEFFES, L., COULSON, D. & ARMITAGE, N.P. 2012. Towards water sensitive urban settlements - integrating design, planning and management of South Africa's towns and cities. In: Proceedings of the 76th IMESA Conference, 24-26 October 2012, George, South Africa. Rivonia: s3 Media, pp. 64-69. [ Links ]

CILLIERS, E.J. & CILLIERS, S.S. 2016. Planning for green infrastructure Options for South African cities. Johannesburg: South African Cities Network. [ Links ]

CLIFFORD, J. 1990. Notes on (field) notes. In: Sanjek, R. (Ed.). Fieldnotes: The makings of anthropology. New York: Cornell University Press, pp. 48-70. [ Links ]

COCK, J. 1980. Maids and madams: A study in the politics of exploitation. Johannesburg: Ravan Press. [ Links ]

DEMUNCK, V.C. & SOBO, E.J. (Eds). 1998. Using methods in the field: A practical introduction and casebook. Walnut Creek, California: AltaMira Press. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF WATER AFFAIRS. 2011. Green Drop Report 2011. 20p. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.dwa.gov.za/Documents/GD/GDIntro.pdf> [Accessed: 27 December 2016]. [ Links ]

DEWALT, K.M. & DEWALT, B.R. 2010. Participant observation. In: Bernard, H.R. (ed.). Handbook of methods in cultural anthropology. Walnut Creek, California: AltaMira Press, pp. 259-300. [ Links ]

eNCA. 2013. Residents dig trenches to get water. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2LOphl5_yLk> [Accessed: 11 November 2016]. [ Links ]

ESCOBAR, A. 2010. Planning. In: Sachs, W. (Ed.). The development dictionary: A guide to knowledge as power. 2nd edition. London: Zed Books Ltd., pp. 145-160. [ Links ]

FISHER-JEFFES, L.N., CARDEN, K., ARMITAGE, N.P., SPIEGEL, A., WINTER, K. & ASHLEY, R. 2012. Challenges facing implementation of water sensitive urban design in South Africa. In: WSUD 2012: Water sensitive urban design; Building the water sensitive community. 7thInternational Conference on Water Sensitive Urban Design, 21-23 February 2012, Barton, A.C.T.: Engineers Australia, pp. 902-909. [ Links ]

GANDY, M. 2004. Rethinking urban metabolisms: Water, space and the modern city. City, 8(3), pp. 363-379. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360481042000313509 [ Links ]

GOOGLE EARTH. 2017. <https://www.google.com/earth/download/ge/> [Accessed: 8 October 2017]. [ Links ]

HARAWAY, D.J. 2003. The companion species manifesto: Dogs, people and significant otherness. Chicago, Illinois: Prickly Paradigm Press. [ Links ]

HARAWAY, D.J. 2008. When species meet. Posthumanities, 3. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

HARAWAY, D.J. 2010. When species meet: Staying with the trouble. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28, pp. 53-55. https://doi.org/10.1068/d2706wsh [ Links ]

HARAWAY, D.J. 2016. Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822373780 [ Links ]

HOLSTON, J. 2009. Insurgent citizenship in an era of global urban peripheries. City & Society, 21(2), pp. 245-267. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-744X.2009.01024.x [ Links ]

HUCHZERMEYER, M. 2006. The new instrument for upgrading informal settlements in South Africa: Ccontributions and constraints. In: Huchzermeyer, M. & Karam, A. (Eds). Informal settlements: A perpetual challenge? Cape Town: UCT Press, pp. 41-61. [ Links ]

INGOLD, T. 2017. On human correspondence. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, (N.S.) 23(1), pp. 9-27. [ Links ]

KAWULICH, B.B. 2005. Participant observation as a data collection method. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(2), pp. Art. 43, May. [ Links ]

LESHAGE, S. 2017. A month of maggots for Marikana community. Potchefstroom Herald: 4, 9 February. [ Links ]

MAGUBANE, B.M. 1979. The political economy of race and class in South Africa. London: Monthly Review Press. [ Links ]

MAIMANE, M. 2012. How Annette Combrinck was elected mayor of Tlokwe. Politics web, 22 November. [Online]. Availble at: <http://www.politicsweb.co.za/about/how-annette-combrinck-was-elected-mayor-of-tlokwe-> [Accessed: 8 November 2016]. [ Links ]

MARSHALL, C. & ROSSMAN, G.B. 1995. Designing qualitative research. Newbury Park, California: Sage. [ Links ]

MEMA, V. 2010. Impact of poorly maintained waste water and sewage treatment plants: Lessons from South Africa. Pretoria: Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. 16p. [Online]. Available at: <http://www.ewisa.co.za/literature/files/335_269%20Mema.pdf> [Accessed: 27 December 2016]. [ Links ]

MURRAY, M.J. 2009. Fire and ice: Unnatural disasters and the disposable urban poor in post-apartheid Johannesburg. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33(1), pp. 165-192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00835.x [ Links ]

NANDA, S. 1994. Cultural anthropology. Belmont, California: Wadsworth. [ Links ]

NJOH, A.J. 2009. Urban planning as a tool of power and social control in colonial Africa. Planning Perspectives, 24(3), pp. 301-317. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665430902933960 [ Links ]

PARNELL, S. & MABIN, A. 1995. Rethinking urban South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 21(1), pp. 39-61. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057079508708432 [ Links ]

PDG. 2012. Environmental management and local government. 31p. [Online]. Available at: <http://pdg.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Environmental-management-and-local-government.pdf> [Accessed: 7 January 2017]. [ Links ]

PUIG DE LA BELLACASA, M. 2011. Matters of care in technoscience: Assembling neglected things. Social Studies of Science, 41(1), pp. 85-106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312710380301 [ Links ]

PUIG DE LA BELLACASA, M. 2012. 'Nothing comes without its world': Thinking with care. The Sociological Review, 60(2), pp. 197-216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2012.02070.x [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 1996. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Act 108 of 1996. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

ROBINS, S. 2014. The 2011 toilet wars in South Africa: Justice and transition between the exceptional and the everyday after apartheid. Development and Change, 45(3), pp. 479-501. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12091 [ Links ]

RODDA, N., STENSTRÖM, T.A., SCHMIDT, S., DENT, M., BUX, F., HANKE, N., BUCKLEY, C.A. & FENNEMORE, C. 2016. Water security in South Africa: Perceptions on public expectations and municipal obligations, governance and water re-use. Water SA, 42(3), pp. 456-465. https://doi.org/10.4314/wsa.v42i3.11 [ Links ]

ROSS, F. 2010. Raw life, new hope: Decency, housing and everyday life in a post-apartheid community. Claremont: UCT Press. [ Links ]

SACN (SOUTH AFRICAN CITIES NETWORK). 2015. Sustainable Cities Report: A summary of cities' vulnerabilities as they transition towards sustainability. [Online]. Available at: <http://sacitiesnetwork.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/SACN-Sustainable-Cities-Report-WEB.pdf> [Accessed: 20 March 2016]. [ Links ]

SPIEGEL, A.D., WATSON, V. & WILKINSON, P. 1999. Speaking truth to power? Some problems using ethnographic methods to influence the formulation of housing policy in South Africa. In: Cheater, A. (Ed.). The anthropology of power: Empowerment and disempowerment in changing structures. London: Routledge, pp. 175-190. [ Links ]

SPLUMA (SPATIAL PLANNING AND LAND USE MANAGEMENT ACT). 2016. Government Notice 559 in Government Gazette 36730, dated 5 August 2013. Commencement date: 1 July 2015 [Proc. No. 26, Gazette No. 38828, dated 27 May 2015]. [ Links ]

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA. 2012. Census 2011. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. [ Links ]

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA. 2013. Non-financial census of municipalities 2013. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. [ Links ]

TSING, A. 2016. Earth stalked by man. The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology, 34(1), pp. 2-16. https://doi.org/10.3167/ca.2016.340102 [ Links ]

TURTON, A. 2008. Three strategic water quality challenges that decision-makers need to know about and how the CSIR should respond. In: Proceedings of "Science Real and Relevant", 2ndCSIR Biennial Conference, 17-18 November 2008, Pretoria, Centre for Scientific and Industrial Research, 28p. [ Links ]

VAN DOORN, T. 2014. Care. Environmental Humanities, 5(1), pp. 291-294. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3615541 [ Links ]

VAN DOORN, T. 2015. A day with crows - rarity, nativity and the violent-care of conservation. Animal Studies Journal, 4(2), pp. 1-28. [ Links ]

VAN HUYSSTEEN, E., LIEBENBERG, S. & GUELI, R. 2007. Integrated development planning in South Africa. Lessons for international peacebuilding? African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes. [Online]. Available at: <http://www.accord.org.za/ajcr-issues/integrated-development-planning-in-south-africa/> [Accessed: 14 March 2017]. [ Links ]

VICTOR, H. 2016. 'There is life in this place': Water infrastructure, 'DIY-formalization' and citizenship in Marikana informal settlement. Mini dissertation - HonsBA Potchefstroom: North-West Univeristy. [ Links ]

WATER RESOURCES GROUP. 2009. Charting our water future: Economic frameworks to inform decision-making. The Barilla Group, The Coca-Cola Company, The International Finance Corporation, McKinsey & Company, Nestlé S.A., New Holland Agriculture, SABMiller Plc, Standard Chartered Bank, and Syngenta AG. 198pp. [ Links ]

WATSON, V. 2004. Teaching planning in a context of diversity. Planning Theory and Practice, 5(2), pp. 252-253. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464935042000225599 [ Links ]

WESSA (WILDLIFE AND ENVIRONMENT SOCIETY OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2012. South Africa's water resources: WESSA position statement. [Online]. Available at: <http://wessa.org.za/uploads/images/position-statements/Water%20Resources%20-%20WESSA%20Position%20Statement%20-%20Approved%202013%20.pdf> [Accessed: 27 December 2016]. [ Links ]

WILHELM-RECHMANN, A. & COWLING, R.M. 2013. Local land-use planning and the role of conservation: An example analysing opportunities. South African Journal of Science, 109(3/4), March/April, pp. 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1590/sajs.2013/20120026 [ Links ]

WRITER, S. 2015. Who is using all the water in South Africa? Business Tech. [Online]. Available at <https://businesstech.co.za/news/general/104441/who-is-using-all-the-water-in-south-africa/> [Accessed: 27 December 2016]. [ Links ]

WWF SOUTH AFRICA. 2013. An introduction to South Africa's water source areas. 2013 Report. 55p. [Online]. Available at: <http://awsassets.wwf.org.za/downloads/wwf_sa_watersource_area10_lo.pdf> [Accessed: 3 January 2017]. [ Links ]

ZHANG, T. 2006. Planning theory as an institutional innovation: Diverse approaches and nonlinear trajectory of the evolution of planning theory. City Planning Review, 30(8), pp. 9-18. [ Links ]

Reviewed January 2018

Revised January 2018

The authors declared no conflict of interest for this title or article.

1 This chapter is published in an edited book entitled The anthropology of power: Empowerment and disempowerment in changing structures.

2 The above quote is cited from the second edition of The development dictionary, published in 2010; hence, the date discrepancies.

3 These findings are from an independent internal census of the settlement, conducted by the 'residential committee' in 2015.

4 Governance of the Tlokwe municipality (now JB Marks municipality) was temporarily transferred from the ANC (African National Congress) to the DA (Democratic Alliance), due to internal fights among ANC Council members (Maimane, 2012).