Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Acta Structilia

versão On-line ISSN 2415-0487

versão impressa ISSN 1023-0564

Acta structilia (Online) vol.30 no.1 Bloemfontein 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.38140/as.v30i1.7336

REVIEW ARTICLE

Litema artivism: community-engaged scholarship with international online learning

Gerhard BosmanI; Anita VenterII; Phadi MabeIII

IAssoc. Prof. Gerhard Bosman, Department of Architecture, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. Email: <bosmang@ufs.ac.za>, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2146-1482

IICentre for Development Support, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. Email: <ventera@ufs.ac.za>

IIIDepartment of Architecture, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. Email: <MabePME@ufs.ac.za>

ABSTRACT

The misconception that online learning and teaching for the building sciences is ineffective has been proven wrong. A blended learning technique, combining service-learning activities and research (community-engaged scholarship) with Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL), has shown great learning and teaching possibilities on an international digital platform. This article considers how community-engaged scholarship and COIL can support an international learning experience celebrating rural art and architecture in central parts of South Africa. The research used a qualitative participatory action research approach and social learning theory framework. Combining practical outcomes in service-learning activities with collaborative international desk research provided a new perspective of litema wall-decorating art in rural parts of the eastern Free State province. These activities developed into a collaboration opportunity as a COIL exchange. A novel conceptual service-learning approach requires good communication and networking, clear agendas, as well as dedicated staff and students. The study merged service-learning activities by South African architecture students at the University of the Free State with literature from American art history students from Colorado State University through COIL that resulted in a collaborative exhibition of research findings. The study follows the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of quality education and gender equality, as well as the "Art-Lab for Human Rights and Dialogue" that intervenes ethically for human rights as "activist" acts of care for rural domestic art.

Keywords: Architecture, community engagement, Collaborative Online International Learning, COIL, litema art, service learning, sustainable development goals

ABSTRAK

Die wanopvatting dat aanlyn-leer en onderrig vir die bouwetenskappe ondoeltreffend is, is verkeerd bewys. 'n Gemengde leertegniek, wat diensleeraktiwiteite en navorsing (gemeenskapsbetrokke vakkundigheid) kombineer met Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL), het wonderlike leer- en onderrigmoontlikhede op 'n internasionale digitale platform getoon. Hierdie artikel kyk na hoe gemeenskapsbetrokke vakkundigheid en COIL 'n internasionale leerervaring kan ondersteun wat landelike kuns en argitektuur in sentrale dele van Suid-Afrika vier. Die navorsing het 'n kwalitatiewe deelnemende aksie navorsingsbenadering en sosiale leerteorie-raamwerk gebruik. Die kombinasie van praktiese uitkomste in diensleeraktiwiteite met 'n samewerkende internasionale literatuurstudie het 'n nuwe perspektief van Litema-muurversieringkuns in landelike dele van die Oos-Vrystaat-provinsie gebied. Hierdie aktiwiteite het ontwikkel in 'n samewerkingsgeleentheid as 'n COIL-ervaring. 'n Nuwe konseptuele diensleerbenadering vereis goeie kommunikasie en netwerkvorming, duidelike agendas sowel as toegewyde personeel en studente. Die studie het diensleeraktiwiteite deur Suid-Afrikaanse argitektuurstudente aan die Universiteit van die Vrystaat saamgesmelt met literatuur van Amerikaanse kunsgeskiedenis-studente van Colorado State University deur middel van 'n COIL wat gelei het tot 'n samewerkende uitstalling van navorsingsbevindinge. Die studiebenadering volg die Verenigde Nasies se Volhoubare Ontwikkelingsdoelwitte (SDG's) van kwaliteit onderwys en geslagsgelykheid en die "Art-Lab for Human Rights and Dialogue" wat eties ingryp vir menseregte as "kunsaktivistiese" dade van sorg vir plattelandse woonhuiskuns.

1. INTRODUCTION

Community-engaged scholarship combines teaching, research, and community service by a faculty member or group, while service learning is the strategy that integrates meaningful community service with instruction, reflection, evaluation, and reciprocity (Gregory & Heiselt, 2014: 405-406). The challenge in some disciplines is that community-shared activities can often be a one-sided act of goodwill from the students with hardly any interaction, reflection, or reciprocity. Students are made aware of the importance of reciprocity during service-learning activities, in order to enhance the quality of the learning experience for all participants (Petri, 2015: 94-95).

In architectural education, the challenge will be to ensure that students learn from other lived worlds, in order to sensitise their future efforts to design solutions for the built environment, especially in rural areas. Informal urban areas deserve academic attention, but more needs to be written about service-learning experiences in rural areas (Harris, 2004: 41).

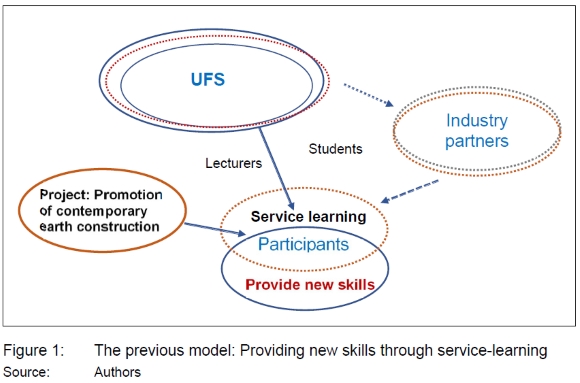

The Department of Architecture at the University of the Free State (UFS) used a model in past community development engagement (see Figure 1). The Department of Architecture has used this model since 1996 to support new skills for participants and students through service-learning.

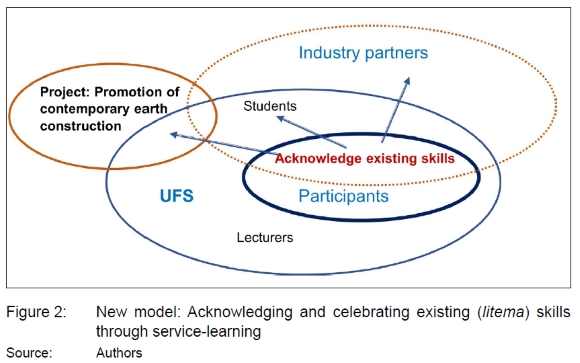

A recent conceptual method transformation in learning and teaching at the UFS' Department of Architecture provides new insight into participants' gerceptions of engagement between students and communities (see Figure 2). It was, however, extended to rural areas where natural earth -building skills are often practised. Through acts of reciprocity, the service-learning experience is not associated with charity; it is a shared experience with transformation (Pompa, 2002: 68).

This new model was used for the first time in 2021 for the Architecture of Care and Engagement (ACE) project, which consists of service-learning activities modelled on a novel approach that acknowledges and celebrates existing (litema) skills through service-learning. This approach provides reversed roles between community participants and students, offering unique learning opportunities about art, architecture, and culture in a less intimidating and formal teaching environment. This new model forms a new conceptual framework for service learning to explore the challenges relating to service-learning at the UFS.

The new model method mainly relies on increased financial assistance and addresses organisational constraints and challenges. Despite these challenges, it is vital in a de-colonised service-learning curriculum and it supports four concerns of UNESCO's Art-Lab for Human Rights and Dialogue. The first is the effect of art-based practices on human rights and peace-building, and the second is to provide a platform for underrepresented voices within dominant cultural narratives. The third concern is facilitating conversation among experienced trainers in artistic interventions in delicate situations, culture experts and practitioners, journalists, and researchers referred to as 'artivists'. The last concern is encouraging Ethical Artistic Practice in the Assistance of Human Rights and Dignity (WSF, 2022). UNESCO Art Lab (WSF, 2022) asks lecturers, practitioners, and researchers: "What is the actual space left for artistic research in the scientific world"?

The challenges led to the research question of how service-learning and international student collaboration can celebrate litema wall decoration to support art and activism, while keeping the sustainable development goals in mind. Using this new model, this article reacts to global acts of care that reflect changes in curriculum-based service-learning to include three approaches. First, to adapt teaching so that students learn from the community as a bottom-up learning approach. Secondly, to combine service-learning and international student collaboration. Thirdly, to provide a new perspective on litema literature on earth-constructed homesteads and wall decoration in the Free State province.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

To understand the new model of architecture learning and teaching and international online collaboration as acts of care for marginalised communities, it is important to introduce traditional South African art and architecture, research challenges, and the literature gap on litema perceptions.

2.1 Litema and rural art

Various studies extensively recorded the contribution of South Sotho women in designing and preserving domestic areas in rural regions of the eastern Free State and Lesotho (Casalis, 1861; Tyrrel, 1971; Knuffel, 1973; Motsepe, 1999). The earliest evidence of this tradition was recorded in 1812 (Campbell, 1815). These records illustrate that decorative art was and still is central to the role and significance of women in the rural built environment. The importance, meaning, and methods used in the creation of litema (pronounced: di-te-ma) have been explored in a few studies by scholars (Gay, 1980; Van Wyk, 1998) and reflections from a photographer (Changuion, 1989) in the late 20th century. South African architect and academic Franco Frescura (1985) made substantial contributions to the practices of decorative wall art of South African cultural groups such as the South Ndebele and the Vendas linked to a socio-cultural order and representation.

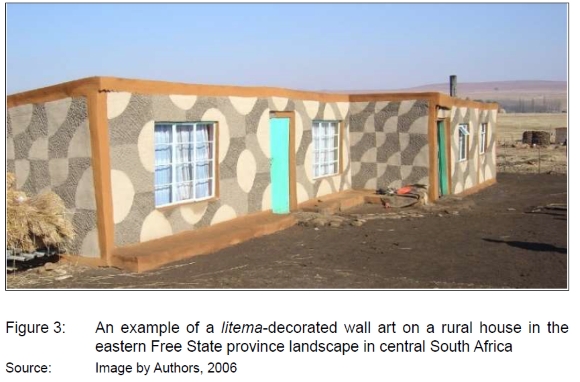

The acknowledgement that Ndebele artist Esther NN Mahlangu received for her mural work in their vernacular dwellings highlights the importance of Ndebele art and architecture as South African heritage on an international stage. Van Vuuren (2015: 141-143) cautions against artistic image stereotyping. He emphasised the Ndebele artistic image and stereotype in the mid-1950s that affected Ndebele groups by forced removals, causing a 'disjunctive alienation' of Ndebele images and artifacts from advertising and marketing experienced from 2000 till 2005. This led to the current manifestations of an appropriation of traditional architectural expressions found in tourism-industry products. Most of the Ndebele women remained anonymous and forgotten. One of the most significant differences from Ndebele patterns is that the South Sotho litema practice is a seasonal, temporary expression of identity and culture, often repeated twice a year prior to and after a rainy season (see Figure 3). The litema artists utilise four primary techniques of engraving, creating relief mouldings, mosaics, and painting murals. The geometric patterns appeared inside dwellings, and only in the 19th century did they appear on the exteriors of dwellings (Frescura, 1985). Creating litema is rooted in the frameworks of lineage and tradition in a multifaceted way (Riep, 2014: 28). The methods and designs used are often passed down from generation to generation. Many women will learn the art of creating litema murals from their mothers at a young age. It is argued that the decorative art of the Ndebele relates to the compositional and geometric litema tradition, while attempting to construct a different order and pattern of wall decoration (Van Vuuren, 2015: 140).

The design patterns used by artists have developed into their interpretations beyond traditional South Sotho litema designs, as documented by Benedict Lira Mothibe, an art lecturer from the National Teachers' Training College of Lesotho, in a 1976 publication (Beyer, 2008: 2-25). This was remastered in 29 litema designs at the time, all named in patterned diagrams in Litema - Mural masterpiece: A design manual by Carina Mylene Beyer (2008). In 2003, Mothibe further contributed with a booklet donation of documented litema designs to the Central University of Technology (CUT).

The temporal and seasonal wall decoration holds memory, identity, and culturally significant architecture (Figure 3).

South African architect and academic Heinrich Kammeyer (2010) collected fieldwork data on litema existing skills in 1999. The unpublished thesis on South Sotho women and their vernacular architecture investigated the making of homes as artifacts. Kammeyer visited a small selection of homesteahs in the eastern Free State province's Ficksburg district. The fieldwork did not include interactive workshops or an outcome to celebrate litema skills. Furthermore, the doctoral study by Riep (2011) from 2004 to 2010 investigated the stylistic characteristics in the presentation of southern Sotho identity, and only a small section of litema was covered during his investigation. This low occurrence of contemporary litema research points to the relevancy of the Architecture of Care and Engagement (ACE) project conducted by the Earth Unit in the UFS' Department of Architecture.

2.2 Service-learning in architecture

Hollander (2010: ix) describes service-learning participants as the bearers committed to "a revolutionary redefinition of the nature of scholarship and institutional transformation". Service-learning develops citizenship (Deely, 2015: 4-5). It is also a "complex and dynamic pedagogy, which may have a profound impact on the learning of those involved" (Venter, Erasmus & Seale, 2015: 148). Architecture learning and teaching are also complex.

Architecture is fortunate, since physical outcomes can result in built forms useful as shelters and improved physical structures to make the built environment better. The bigger challenge for architectural academics is to stand back and first acknowledge a community's existing building skills. To do this will practically imply spending more time in a community to establish trust and then to build a short-term relationship before a sustained relationship can develop over time. This long-term relationship can only develop with commitment from the faculty and staff. Furthermore, if students are fully immersed in the community, service-learning can make a tangible contribution to the quality of rural life (Harris, 2004: 41).

This transformation with service-learning in architecture curricula at the UFS is well-established (Bosman, 2009, 2012, 2022; Nel & Bosman, 2014). The experimental research of the ACE project on architectural place-making (phenomenology) supports and celebrates the role of women in the rural Free State province. The ACE project addresses the ownership of artistic expressions, while highlighting local traditional place-making and art-conservation efforts. The ACE project hypothesis is that conserving earth-constructed homesteads and conventional wall decorations of litema art will empower rural women artists from the Free State province.

The ACE project aims to build sustainable relationships and a mode of interaction to voice the artists responsible for existing and current practices of litema in central South Africa. The ACE falls under a larger long-term research project titled, The social-ecological significance of earth construction in Southern Africa, which was ethically cleared (UFS-HSD2021/1745/21), in 2021, by the UFS.

2.3 Collaborative Online International Learning

Online learning has evolved pre-COVID (Bhagat, Wu & Chang, 2016: 350-351) and especially rapidly post-COVID as a worldwide platform. During the first part of 2021, while doing an independent COIL exchange with a different UFS student group, Bosman explored the possibilities of COIL to support the ACE project. COIL falls under the social-constructivist educational approach, is a relatively new method, and literature is still emerging (Guth & Rubin, 2015). Higher education institutions can provide opportunities to students for intercultural collaboration experiences designed to solve problems in architecture. These experiences afford participants the opportunity to boost their confidence and communication skills (Gutiérrez-González et al., 2022: 20). Furthermore, COIL provides learning social interaction and is the keystone of developing intercultural competence (Guth & Rubin 2015; Hackett et al., 2023: 1). COIL exchanges illustrate the potential to achieve individual course objectives, while evaluating international student groups (De Santi et al., 2022: 3).

Criticism against the traditional and physical international exchange opportunities for mainly postgraduate students is valid for its elitist, expensive, and complex nature (Leal, Finardi & Abba, 2022: 241-242). COIL for both under- and postgraduate students hopes to achieve more cross-cultural student engagements and foster intercultural awareness, teamwork skills, and problem-solving abilities related to diversity, equity, and inclusion (De Santi et al., 2022: 3). The COIL activity, strategised as an instructional technique, facilitates an intercontinental conversation in a virtual environment between students and educators in remote positions. The method enables them to connect, despite geographical, time, cultural, and linguistic barriers (De Santi et al., 2022: 4). Higher education institutions not only identify the most vulnerable in society, but also endeavour to build resilience with the related pillars of teaching and learning, research, and community service (Olawale et al., 2022: 14-15). The global community is furthermore committed to using the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with the three university pillars.

In this study, ACE provided the conceptual framework and COIL provided the theoretical framework for the exchange. COIL allowed for the theoretical framework that investigates perceptions and relationships between the existing literature on litema practices to be compared to the ACE findings. A lack of recent literature led the researchers to contact and collaborate with David Riep, an American art historian from Colorado State University, who investigated litema symbolism during the fieldwork for his PhD in South Africa (Riep, 2011). The link with Riep was crucial. His work on South Sotho's traditional artefacts was a good fit with the involvement of his art and art history students, which started with a semester on Art and environment in the arts of the African continent. The COIL exchange began in February 2022.

3. METHODS

3.1 Research design

This article reflects on how service-learning and international collaboration can celebrate litema wall decoration artists to support the architecture of care as an act for global change. Using a qualitative research design, participatory action research (PAC) was used to gain insight into the perceptions of artists and students on the architecture of care as an act for global change. PAC combines research and action, using surveys and fieldwork to collect data (Katoppoa & Sudradjatb, 2015: 121). In this study, three stages in the research process were used. Service-learning fieldwork and research combined with a COIL exchange, with the outcome of a public exhibition on two continents, promoting and celebrating the skill of rural litema artists, involved researchers, and participants, collaborating to understand litema wall decoration artists to support the architecture of care as an act for global change.

3.2 Stages

3.2.1 Stage one: Service-learning fieldwork and research

The ACE project was based on a PAC design (IDS, 2023) and utilised critical theoretical constructs based on the Social Learning Theory (the concept of modelling or learning by observing behaviour) (Badura, 1977). The process is modelled on past experiences of the Earth Unit, where artisans and artists were purposely sampled and surveyed with semi-structured interviews. The ACE project purposefully identified litema artists and their homesteads and mapped for future follow-up visits to sustain relationships with the artists. The semi-structured interviews were conducted in Se-Sotho, Isi-Zulu, or Setswana. The voices of the women artists were transcribed into English. The artists are proud of their practice and cultural heritage and prefer to be acknowledged and identified.

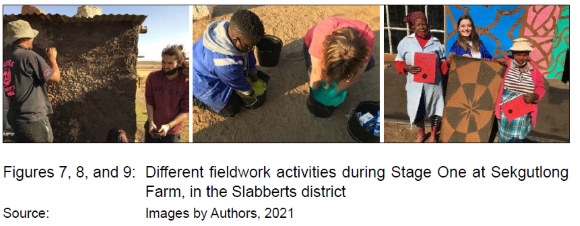

The fieldwork for the ACE project began in early 2021 to document the mural arts and architecture of rural South Sotho artists and record the experiences of both students and artists. Potential homestead workshop locations for the ACE project were identified in February 2021. By May 2021, the transportation, accommodation, and workshop logistics were completed. In June 2021, Bosman, David Van der Merwe, Mabe of the EU, and Venter from the UFS' Centre for Development Support conducted three tours to farms in the eastern Free State. The three sites included homesteads at Duikerfontein Farm (near Paul Roux), Clear Water Farm (near Warden), and Sekgutlong Farm in the Slabberts district south of Bethlehem.

The three different field trips had the same programme. Forty-two students were divided into three groups to spend three days participating in various activities of the fieldwork assignment. Activities included supervised tasks, gathering raw materials, surveying existing homes, and preparing surfaces for movable plaster panels, forming part of the exhibition. On arrival, a short introductory meeting presented the aim of the fieldwork activities to artists and participants. The introduction highlighted how the fieldwork is an active effort to build sustainable relationonships between the UFS and artists. During the fieldwork when participants could not understand each other's languages, they communicated through body language and facial expressions. The applied model of fieldwork method is well-developed in anthropology, but seldom used in architecture for teaching and learning. Social interactions between participants spontaneously developed over the three days. The focus was on a shared expehence, in which 36 women and six men were asked to teach the art of tradicional South Sotho litema wall decoration to 42 second-year architecture students (Figure 7-9).

Formal discussion and interviews were arranged in varbus languages, including Sesotho, isiZulu and English, although language barriers proved challenging. Qualitative data was gathered from purposefully selected and identified artists (n=11) and anonymous reflections from the second-year students (n=31) who participated in the engagement activities over three days, in three groups, on three farms. The semi-structured interview schedule contained 30 questions on the backgrownd of the litema practice, the future expectations of the artist on her practice, and symbolism and emotions associated with the practice. The interviews captured artists' perceptions of current litema practices, cultural significance, origin, and socio-ecological position in contemporary rural homesteads in central South Africa. Upon completion of the interviews with the artists, the recordings were transcribed into English for analysis. The interview data of the artists were coded holistically around the physical aspects of their practice, the symbolism and meaning of the practice, and the artist's experience working with staff and students.

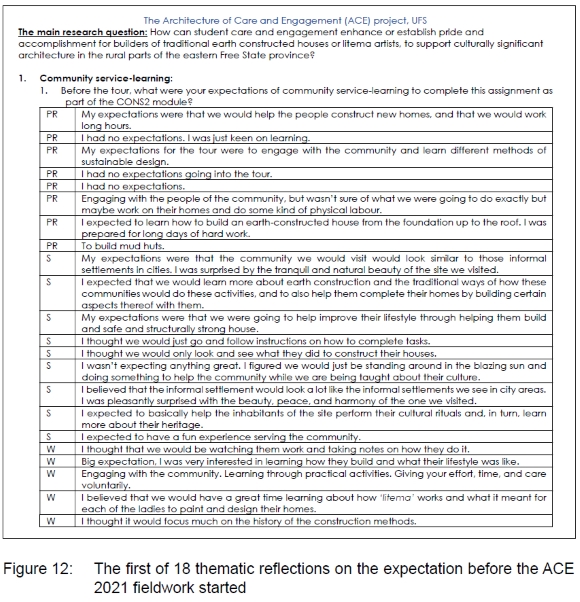

Student fieldworkers provided valuable service-learning reflections from the three groups visiting the farms. Students had to reflect on 18 questions structured around their expectations and the integrations of the ACE activities within their course, but most of the questions were on rural housing conditions, social and cultural exchange, engagement, and activities they enjoyed the most or the least. The students' reflections were coded holistically around themes that identified their expectations, experience, and emotions during the fieldwork. The holistic coding of themes from transcriptions and reflections provided analysed categories, using the constant comparative approach (Petri, 2015: 98).

The first stage of the research served as a preliminary exploration, upon which an international student online collaboration could be added.

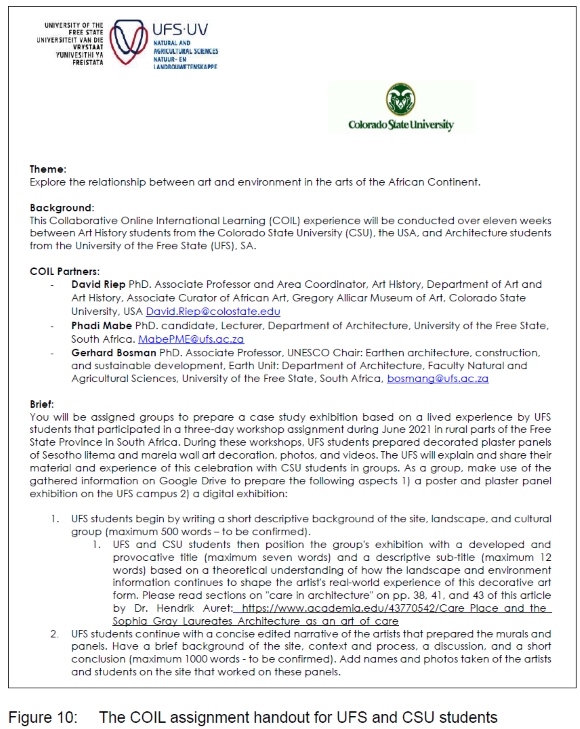

3.2.2 Stagetwo:COIL exchange

Stage Two combined the service-learning of the ACE with COIL. During the time when the service-learning fieldwork of the ACE project started, Bosman (De Santi et al., 2022) explored a different COIL exchange, supported as the ikudu Project, funded by the European Union's Erasmus Plus, in partnership with four other South African and five European partner universities. Upon completing the service-learning fieldwork experiences by UFS students, Bosman, Riep, Mabe, and Roberto Muntoreanu developed a 12-week COIL programme. The same architecture students who did the ACE research project fieldwork and service-learning in 2021, now ten months later, participated in the COIL exchange from February 2022 to May 2022.

The research team joined their outcomes with David Riep from the Colorado State University (SCU) through a COIL exchange to contribute to the gap in more recent literature on litema perceptions. Riep's (2011, 2014) experience and knowledge of litema symbolism, cultural connections to heritage, ancestral connections, and South Sotho rites of passage make him an appropriate partner for this COIL experience. The COIL activity aimed to foster a sense of international solidarity among students from different parts of the world through an integrated educational experience. The students were allowed to develop their intercultural awareness and collaborative skills. Students had to complete an assignment (Figure 10) that resulted in a poster series for an exhibition.

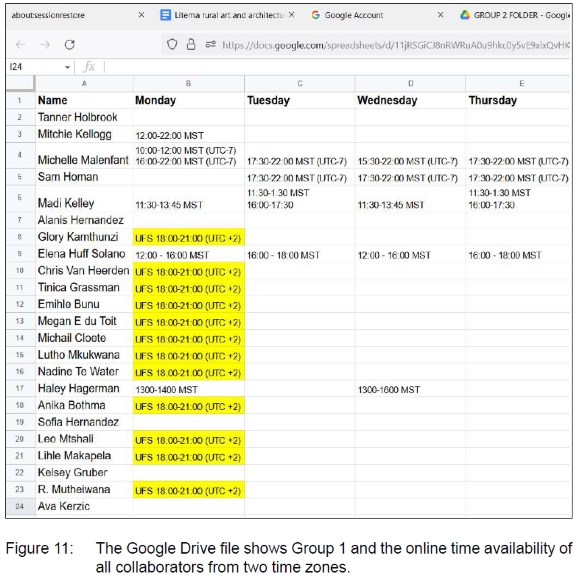

The COIL exchange consists of three parts: an icebreaker introduction, the assignment of comparing preliminary findings for a poster exhibition, and the reflection and assessment of the task. Students from both institutions were assigned to three working groups that completed a literature review of selected articles, ethnographic case studies, and selections from socio-religious sources. This short analysis and in-depth reflection of all participants in the fieldwork were presented as themed posters. The third-year architecture students from UFS shared their field notes, videos, photos, and drawings from the previous years, while the art history students of CSU compiled the text narrative. Under the guidance of Muntoreanu, 10 CSU graphic design students designed three compilations of poster templates based on the provided images of the UFS students. One template was selected with an overall theme.

3.2.3 Stage three: Public exhibition

Stage three was preparing the panels for the public exhibition. The UFS under- and postgraduate students from CSU wrote the text and visual narrative on the litema walls and plaster panels that reflected homestead walls during the fieldwork (see Figures 5 and 9). The reflection was creatively captured through a collaborative production of graphically informative posters on two continents to promote new research through knowledge exchange of cross-cultural perspectives. Padlet, Google Drive, and Blackboard as collaboration platforms allowed for real-time student engagement across two time zones (Figure 11) and allowed students to set the classroom culture for the exchange collectively. The exchange drew upon the strengths of both institutions, by combining architectural fieldwork experiences with art historical research and analysis to create a body of artistic research from rural indigenous knowledge systems.

4. FINDINGS

4.1 Stage one

Quantitative reflections were holistically coded to establish current perceptions of the engagement activities. Figure 12 shows the reflective feedback of the students from the three farms (PR, S, W).

The reflective feedback of the students (Figure 12) shows very positive experiences with temporal relationship experiences over the three days spent with the women artists. (Of the (n=31) anonymous reflection feedback that was received - in terms of their expectations - a student wrote:

"I expected to basically help the inhabitants of the site perform their cultural rituals and, in turn, learn more about their heritage."

On a question of whether the assignment as a learning experience has been meaningful or successful, one student commented:

"Yes. It was a very effective way of learning. We got to mix the materials used on the houses ourselves and felt the textures with our own hands. We also experienced the more difficult aspects and learned from our own mistakes."

Most of the students were negative about the dates of the three tours at the end of the first-semester programme. Students did not like the cold conditions, and most of them did not like to work with cow dung for the plaster and paint mixes.

In terms of whether they had a positive or negative social or cultural engagement with the participants, one student commented:

"Yes, I think ... important is the fact that I have a better picture of what it means to have culture. South African people have a unique and unprecedented way [of] living and working together. Even though we as students did not speak or understand the Sotho language, we found ways of laughing and spending quality time with the homeowners."

The interview data of the artists were coded holistically around the physical aspects of their practice, the symbolism and meaning of the practice, and the artists' experience working with staff and students.

Preliminary findings of transcribed semi-structured interviews of the artists (n=11) showed that the practice of creating litema wall decoration is rooted in the frameworks of lineage and tradition in a multifaceted way.

Artists shared many practical aspects of their practice, such as: where they collect the raw material; how they prepare the material; the quantities and proportions of manure with soil; the application process and method; the design of the patterns, and the frequency of the application were discussed in detail.

In terms of symbolism and meaning, some of the artists' comments revealed that identity and culture are expressed through the hands and eyes of individual women's perspectives:

"According to our culture! It's us ... it's our spirit, like, showing people how proud we are of our houses and our culture. That is how we prefer to build our house and how to make our house beautiful. That is why we do it ... every year! Because it's our pride."

"So, everything about this house is basically the pride of being Sesotho."

"Sometimes we do the patterns. Sometimes we do . something we feel. Like now we have done the stars there, you see. The stars you see."

"The message about these patterns is that nobody does them anymore. This is a message to say that our heritage is beautiful. Also, cleanliness is supposed to be sustained. Yes. It leaves a message that since it is clean and beautiful, anyone may be interested in having a house like this, even if they don't normally ever do it. Beauty is acceptable and cherished and wanted by everyone."

In terms of a connection with ancestors and a personal lineage, the women's views were more nuanced than the limited literature suggest:

"... when I do litema, I would have an honouring celebration and go to the graveyard where they [ancestors] lay, and talk to them."

"Usually, the grandmothers and grandfathers are fond of these houses, because they are the same houses they normally lived in, in the past. Now, they draw close to you if you've got these houses. Because they need teem."

"It has to do with our ancestors because it is part of the Basotho culture that we grew up with."

"I'm going to teach her [my daughter]; this is my life's knowledge".

For all the artists, the experience of the shared practice with students was described as joyful and sharing that reflected the positive engagement and care of the fieldwork approach.On all three farm sites, the activities created a mood for celebration. At Duikersfontein near Paul Roux, one artist described the workshop and fieldwork as follows:

"the thing that happened just now, is more like letsema, ... you call upon the people and prepare meals. After that, the people begin working when they did all the work, then they feasts

During the workshop activities of the ACE project, the artists were comfortable and eager to teach their art to other young women of different cultural groups. The learning occurred through the design and replication and the creative-making process. Figures 13 and 14 show the final walls and panels during the handing out of certificates.

The findings show that the symbolism and meaning of litema as a practice are more complex and nuanced than the literature suggests.

4.2 Stages two and three

To promote active engagement during online learning exchanges, students' perceptions towards this mode of learning and teaching should be determined (Bhagat et al., 2016: 350). The student self-reflection of the COIL exchange was compiled from the three groups on Google Drive. Various discoveries were made when reflecting on the COIS exchange (Stage two). The COIL exchange shows that practical challenges can be overcome over a 10-week online educational experience. Findings from the COIL illustrate that digitisation of the educational experience is transforming the typical classroom. The COIL emulation of a global classroom illustrates that students are prompted to become more aware of intercultural diversity, inclusion, and problem-solving abilities related to diversity and equity.

The graphic design students at CSU provided the final poster templates for the exhibition (Stage three). A student-led selection process by all collaborators resulted in one template to be used to prepare 19 posters. CSU's UFS and art history students develop the narrative and images with photos for the posters. Academic writing with the practical aspects of service-learning develops critical thinking (Deely, 2015: 4).

The title of the poster exhibition is Daughters of Litema: Revering temporal rural earth art, Free State province, South Africa. The student groups had to prepare subtitles to capture the site qualities of the environmental and social landscapes of the farm sites. This formed the organising structure of the narrative, which was arranged into three parts: The rural litema house: The families through the eyes of engaged students; Women in art: The passage of time in South Sotho culture, and Voices beneath the mountain: Curators of the process as ritual.

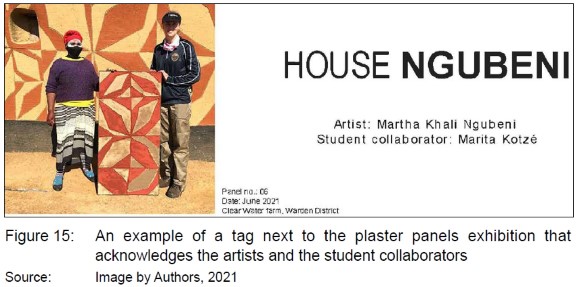

Figure 15 shows one of the 20 plaster panes with the student and the artist who inspired its design. These postere were combined with 20 plaster panels produced the previous year during fleldwork in 600x600mm and 1200x600mm formats. These posters and plaster panels celebrate the role and skills of the female artists and their student collaborators.

5. DISCUSSION

This article focused on artistic research that can bring about change through real-life rural engagement and celebration, by challenging the staff's traditional academic approach to fieldwork and service-learning. The approach is rooted in rigorous, creative research, driven by imagination, and aimed at changing attitudes for staff, students, and communities. This effort was focused on addressing dignity and care through art and engagement, rather than simply science, in order to bring about change.

5.1 Stage one: Service-learning fieldwork and research

The service-learning approach can provide a new place of interaction in a less intimidating environment, while providing contextual learning experiences for students.

A new model of doing service-learning presented the opportunity of taking students on field trips to do service-learning activities. Following this new model, the roles of students and instructors were swapped. The students travelled to the artists who were at ease in their well-known environment. The students were out of their comfort zones instead of the participating community.

Students used PAC and social learning approaches, not commonly used in architectural training, to celebrate the skills of rural women artists and document their litema practices, which are slowly disappearing from the Free State landscape. Documenting litema art is a deliberate intention of creating a slow resistance to the inevitable dissolution of cultural practices. These experiences have strengthened and confirmed the cultural importance of litema and have shown the possibility of intergenerational knowledge and skills transfer. The art is kept alive and provides more resistance to the evolutionary disappearance from the Free State landscape.

The research paradigm of the ACE project reflects the ethos of teaching architecture and engagement as acts of care in the theoretical framework at the UFS' Department of Architecture. Second-year students are introduced to issues such as care and community. According to Heidegger (1927), the ecstasies of care are explained as understanding, attunement, and being-with. These notions are supported by Norwegian architect and critic, Norberg-Schulz's (1980) language of architecture in terms of orientation as topology, identification as morphology, and memory as typology.

The study promotes indigenous building practices elsewhere in South Africa, since it addresses the loss of local heritage, while reflecting on the use of local materials, the cultural significance, symbolism, and the identity of the rural South Sotho communities. Students' engagement in a reallife situation outside the classroom provides an informative environment, where students can build relationships as acts of care towards people- and nature-centred relationships. Van Vuuren (2015) argues that the different Ndebele homestead earth buildings and murals reflect rational decisions made in different situations. The ACE preliminary findings reflected on culture but especially the identity of the artists in reaction to personal taste, own interpretation, and a close link to the availability of either natural coloured clays or to buy industrial pigments. One artist commented on this:

"Sometimes we look at these Masolanka blankets, or maybe the books we view. Sometimes we just depend upon our creativity, on our creative minds. But most times we look at books or the patterns on the blankets." (Moloi, 2021: personal communication).

5.2 Stage two: COIL exchange

The research explored the synergetic potentials of art, architecture, service-learning, and sustained relationships with communities.

Colorado State art students collaborated with South African architecture students' qualitative reflections and qualitative data collected during fieldwork from rural women who installed litema wall decoration art as a temporal home decoration. Through a COIL experience, the South African students learned more from recently recorded notions on the symbolism and cultural significance of this art form that is slowly disappearing from central South Africa's rural parts. This transformed use of service-learning and COIL method supports the United Nations' (2023) SDGs such as quality education (4), gender equality (5), and partnerships for the goals (17), while also presenting the participants' perceptions and research findings.

The COIL exchange necessitated that all students understand their responsibilities, which required consistent reminders. To facilitate this, lecturers had to create clear guidelines and outline specific objectives and deadlines according to the time zone of each institution. In addition, the information and instructions for the joint task or assignment needed to be made available to the students before starting the ice-breaking activities. Lecturers also required access to student work-in-progress on Google Drive to check student progress and intervene with guidance if any groups fell behind with assigned tasks.

Clear and consistent communication was crucial during the COIL exchange. It was essential for outlining project expectations and deadlines and was accomplished through reminder e-mails. Communication helped prevent confusion if a deadline needed to be adjusted. WhatsApp was a useful tool for both the lecturers and the student groups. The seven-hour difference between Colorado and the Free State became a challenge, slowing decision-making if messages were replied to many hours later. However, this was a worthwhile challenge, as the main aim of a COIL is for the students to engage interculturally and cross-culturally, where students must get out of their comfort zones and engage with their peers.

Developing a detailed assessment rubric was also important and was provided to all students prior to the start of the COIL exchange. The rubric made students aware of the outcome and assessment. The lecturers explained the rubric criteria carefully and reminded students of the content, proof of the process followed, and the suggested completion time frame. It was a challenge to finalise the text for the poster exhibition, as insufficient time was allocated for editing the three groups' text narratives into a coherent storyline.

For teaching staff and COIL instructors, this kind of community engagement and cultural exchange asks us to be prepared to explain to students that one learns from diversity in which identity, culture, and language present a multitude of reactions and behaviours when addressing issues or solving problems. The reflective feedback and self-assessment provided by students at the end of the collaboration offered great insight into the student's experiences. The students' assessments will help faculty guide relationships among future student groups, academic institutions, and communities, with which sustainable relationships can be nurtured.

5.3 Stage three: Public exhibition

The dissemination COIL (Stage two) made provision for the exhibition (Stage three) consisting of posters with text narrative and photos of activities and plaster panels prepared after litema practices were completed on the earth walls. In some cases, the plaster panels reflect the same litema designs on the dwellings where the female students worked with the litema artists (homeowners). Figure 15 shows a tag accompanying the plaster panel with the student, the artist, and her work that inspired the panel design. This is a visual dialogue between the artists and the memory of the student's experience during the workshops of June 2021. A maximum of 20 panels can be exhibited with the posters to celebrate the role and skill of the female artist who worked together with female students.

The past model used to address problems in architectural service-learning can be viewed as a top-down approach (see Figure 1) that does not support the United Nations' SDGs. The use of COIL, as combined in the case of the ACE project, opened new partnerships and sustained relationships between UFS' architecture students and litema artists for follow-up workshops and engagement.

Recently, international collaborations have rapidly changed. COIL should focus on how students manage time with deadlines, challenges with digital platforms, and interactions with different time-zone challenges. The study shows that a COIL assignment can result in high-standard posters to the extent that they can be exhibited in a gallery or exposition.

The poster and plaster panel exhibition, produced in collaboration, was exhibited during a high-profile event attended by international research and science organisations, heads of state, and South African members of parliament. From 6 to 9 December 2022, the exhibition was presented at the World Science Forum (WSF, 2022), Science for Social Justice exhibition in Cape Town at the Cape Town International Conventions Centre. In May 2023, a duplicate exhibition opened at the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art of Colorado State University. David Riep curated the exhibition. This exhibition, with colour photos of the plaster panels, shows accompanying tags of artist names and student collaborators. The COIL experience and the celebratory exhibition present the intergenerational transfer of knowledge to help keep this art form alive and provide a slow resistance to its eventual disappearance from the Free State landscape.

6. CONCLUSION

The ACE research project aimed to celebrate the existing skills of litema artists. The problem of combining the research with service-learning provided a new conceptual model for future service-learning and community-engaged scholarship architecture activities conducted by the UFS. This focused on a new method where students had to travel to rural areas to learn from their litema practice rather than the artists trained in upgraded earth-building techniques, as was the case from 1996 till 2018 at the UFS. Within these challenges, a new conceptual model for architecture service-learning was tested. Research with service-learning fieldwork activities created a flipped classroom, where the students and artists became the instructors. With continued financial support, this study opens the way to a more authentic relationship centred on connection, involvement, and participation, while exploring new architectural learning and teaching methods. The literature gap on current litema perceptions furthermore developed into the COIL exchange to partner with David Riep on his experience and acquired knowledge on litema symbolism. The ACE data and the literature by Riep (2011) gave new insight into the perceptions around rural litema practices and their significance. As a long-term effort, COIL sessions with international partners can promote the advantages of contemporary earth construction. Furthermore, the COIL approach asks of students and lecturers to rethink traditional approaches to learning and teaching that support sustainable development goals (SDGs) such as quality education (4), sustainable cities and communities (11), gender equality (5), and partnerships for the goals (17). Research focusing on SDGs supports quality transformed education to accelerate curricula transformation with new learning and teaching methods.

Exploring all possible ways and opportunities to get students out of classrooms to participate in service-learning has many challenges. Still, it can create unexpected quality learning opportunities in real-life situations. Marginalised communities to reach out to can easily be found in urban and rural areas. The research shows that multidisciplinary partnerships make a difference regionally while thinking at an international collaboration level. To establish new partnerships, all possible network opportunities should be explored and pursued for international collaboration. Students, lecturers, as well as art and earth-building practitioners can contribute as 'artivists' to encourage ethical artistic practice in the assistance of human rights and dignity. These acts show care and dignity in celebrating litema art and architecture in the rural part of central South Africa.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We sincerely thank:

• The many litema artists and their families who opened their hearts and homes for use during the memorable experience of learning from their indigenous knowledge of traditional home decoration.

• Prof David Riep, for guiding the Department of Art and Art History at Colorado State University students for the COIL exchange and sharing his extensive knowledge of South Sotho litema symbolism and meaning.

• The Department of Architecture, for allowing this experimental service-learning and COIL experience for students during 2021 and 2022.

• The Central Research Fund of the UFS, for funding the ACE project during 2020-2022.

REFERENCES

Badura, A. 1977. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Beyer, C.M. 2008. Litema - Mural masterpiece. Bloemfontein: Central University of Technology. [ Links ]

Bhagat, K., Wu, L. & Chang, C. 2016. Development and validation of the perception of students towards online Learning (POSTOL). Educational Technology & Society, 19(1), pp. 350-359. https://doi.org/10.1037/t64255-000 [ Links ]

Bosman, G. 2009. Teaching earth construction in the Free State: 1995-2007. Journal of the South African Institute of Architects, Special Issue: July/August, pp. 34-39. [ Links ]

Bosman, G. 2012. Local building cultures and perceptions of wall building materials: Influences on vernacular architecture in rural areas of central South Africa. In: Cardoso, A., Leal, J.C. & Maia, M.H. (Eds). Surveys on vernacular architecture - Their significance in 20th-century architectural culture. Centro de Estudo Arnaldo Araújo, Escola Superior Artistica do Porto, pp. 139-153. [ Links ]

Bosman, G. 2015. The acceptability of earth-constructed houses in central areas of South Africa. Unpublished PhD. thesis, University of the Free State. [ Links ]

Bosman, G. 2022. Relevant service-learning for transformation in architecture learning and teaching. Unpublished paper delivered at the Conference on Sustainable Built Environments (SBE2022), 28-30 March, Grabouw, South Africa. [ Links ]

Campbell, J. 1815. Travels in South Africa. London: Black and Parry. [ Links ]

Casalis, E. 1861. The Basuto. London: James Nisbet and Co. https://doi.org/10.5479/sil.262374.39088000167106 [ Links ]

Changuion, P. 1989. The African mural. Cape Town: Struik. [ Links ]

Deely, S.J. 2015. Critical perspectives on service-learning in higher education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137383259 [ Links ]

De Santi, C., de Boer, M., Bosman, G. & Citter, C. 2022. International multidisciplinary collaboration on four continents: An experiment in fostering diverse cultural perspectives. The Journal of Language Teaching and Technology, IV (Dec), pp.1-18. [ Links ]

Frescura, F. 1985. Major developments in the rural indigenous architecture of Southern Africa of the post-difaqane period. Unpublished PhD. thesis, University of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Gay, J.S. 1980. Basotho women options. Unpublished PhD. thesis, Cambridge University. [ Links ]

Gregory, A. & Heiselt, A. 2014. Reflecting on service-learning in architecture: Increasing the academic relevance of public interest design projects. In: Proceedings of the 102nd ACSA Annual Meeting, 11 April, Miami, Florida: ACSA Press, pp. 404-410. [ Links ]

Guth, S. & Rubin, J. 2015. How to get started with COIL. In: Moore, A. & Simon, S. (Eds). Globally networked teaching in the humanities: Theories and practices. Milton Park, UK: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 15-27. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez-González, S., Coello-Torres, C.E., Cuenca-Romero, L., Carpintero, V. & Bravo, A. 2022. Incorporating Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) into common practices for architects and building engineers. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 22(2), pp. 20-36. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.22.2.2 [ Links ]

Hackett, S., Janssen, J., Beach, P., Perreault, M., Beelen, J. & Van Tartwijk. J. 2023. The effectiveness of Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) on intercultural competence development in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20, pp. 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-022-00373-3 [ Links ]

Harris, G. 2004. Lessons for service learning in rural areas. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 24, pp. 41-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X04267711 [ Links ]

Heidegger, M. 1927. Being and time. Translated by J. Stambaugh, 2010. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Hollander, E. 2010. Foreword. In: Butin, S. (Ed.). Service-learning in theory and practice: The future of community engagement in higher education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. vii-xii. [ Links ]

IDS (Institute of Development Studies). 2023. Participatory methods. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.participatorymethods.org/glossary/participatory-action-research> [Accessed: 10 May 2023]. [ Links ]

Kammeyer, H. 2010. Reciprocity in the evolution of self though the making of homes-as-artefacts: A phenomenological study of the Basotho female in her vernacular architecture. Unpublished PhD. thesis, University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Katoppoa, M. & Sudradjatb, I. 2015. Combining Participatory Action Research (PAR) and Design Thinking (DT) as an alternative research method in architecture. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 184, pp. 118-125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.05.069 [ Links ]

Knuffel, W.E. 1973. The construction of the Bantu grass hut. Graz: Akademische Druck. Verlag. [ Links ]

Leal, F., Finardi, K. & Abba, J. 2022. Challenges for an internationalization of higher education from and for the Global South. Perspectives in Education, 40(3), pp. 241-250. https://doi.org/10.18820/2519593X/pie.v40.i3.2 [ Links ]

Moloi, M.A. 2021. (Litema artist: Duikerfontein Farm, Paul Roux district, Free State province). Personal communication on the significance of Litema art. [ Links ]

Motsepe, F. 1999. Associations of Botho to lifestyle patterns and spatial expressions. Unpublished master's dissertation, Leuven University. [ Links ]

Nel, J.H. & Bosman, G. 2014. Exposing architecture students to vernacular concepts. In: Correia, M.R., Carlos, G. & Rocha, S. (Eds). Vernacular heritage and earthen architecture - Contributions for sustainable development. CRC Press: London, pp. 767-772. https://doi.org/10.1201/b15685-132 [ Links ]

Norberg-Schulz, C. 1980. Genius loci: Towards a phenomenology of architecture. London: Academy Editions. [ Links ]

Olawale, E., Mncube, V.S., Ndondo, S. & Mutongoza, B.H. 2022. Building a sustainable and democratic future in rural South African higher education institutions. Perspectives in Education, 40(3), pp. 14-28. https://doi.org/10.18820/2519593X/pie.v40.i3.2 [ Links ]

Petri, A. 2015. Service-learning from the perspective of community organizations. Journal of Public Scholarship in Higher Education, 5, pp. 93-110. [ Links ]

Pompa, L. 2002. Service-learning as crucible: Reflections on immersion, context, power, and transformation. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 9(1), pp. 67-76. [ Links ]

Riep, D.M.M. 2011. House of the crocodile: South Sotho art and history in southern Africa. Unpublished PhD. thesis, The University of Iowa. [ Links ]

Riep, D.M.M. 2014. Hot women! South Sotho female arts in context. African Arts, 47(4), pp. 24-38. https://doi.org/10.1162/AFAR_a_00162 [ Links ]

Tyrrel, B. 1971. Tribal peoples of Southern Africa. Cape Town: Books of Africa. [ Links ]

United Nations. 2023. Department of Economic and Social Affairs -Sustainable Development. [Online]. Available at: <https://sdgs.un.org/goals> [Accessed: 15 January 2023]. [ Links ]

Van Vuuren, C.J. 2015. In memory of the Ndebele homestead: Women as earthen builders and mural artists. South African Journal of Art History -Women in the visual arts 30(1), pp. 141-157. [ Links ]

Van Wyk, G.N. 1998. African painted houses: Basotho dwellings of Southern Africa. New York: Harry N. Abrams. [ Links ]

Venter, K., Erasmus, M. & Seale, I. 2015. Knowledge sharing for the development of champions. Journal for New Generation Sciences, 13(2), pp. 147-163. [ Links ]

WSF (World Science Forum). 2022. UNESCO Art Lab Programme 06 Dec/ Day 1 Side Events. [Online]. Available at: <https://worldscienceforum.org/programme/2022-12-06-artistic-research-and-humanities-for-conflict-transformation-and-social-justice-a-case-study-unescos-art-lab-for-human-rights-and-dialogue-253> [Accessed: 10 January 2023]. [ Links ]

Received: May 2023

Peer reviewed and revised: May 2023

Published: June 2023

DECLARATION: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.