Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Structilia

On-line version ISSN 2415-0487

Print version ISSN 1023-0564

Acta structilia (Online) vol.28 n.2 Bloemfontein 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150487/as28i27

REVIEW ARTICLE

A comparison of three public projects that included community participation to determine the total value add

Prof. Christo Vosloo

Graduate School of Architecture, Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture, University of Johannesburg, P.O. Box 524, Auckland Park, 2006, Johannesburg, South Africa. Phone: +27 (0) 11 559 1105, e-mail: <cvosloo@uj.ac.za>, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2212-1968

ABSTRACT

Some of the most pressing and challenging problems facing South Africa are unemployment, poverty, urban redress, infrastructural decay, under-education, and the transformation of the landscape left by apartheid. In an effort to address these problems, the successive democratic governments embarked on a number of initiatives that were aimed at providing relief through building and construction projects, which require the participation by, and employment of local community members. To facilitate the desired redress, various programmes were launched and a number of projects undertaken. Some of these projects were flagship projects that were lauded by the architectural profession and attracted wide publicity. The socio-economic benefits to the community and local area, the extent of skills transfer to the community participants, and the long-term benefits they brought to the community participants are less obvious. This article revisits three such projects as case studies, with the aim of determining the extent to which they helped address the aforementioned problems and the extent of the benefits they brought to their physical and social contexts. This is done through a literature review supported by semi-structured interviews of relevant role players and an observational visit to each, in order to make recommendations suggesting how future projects could be configured to maximise the long-term benefit they could bring to their physical and social environments while addressing the national challenges. It is recommended that infrastructural development programmes such as the Extended Public Works Programme must prioritise the socio-economic upliftment and sustainable empowerment of people and configure projects with this as their main aim.

Keywords: Building and construction projects, community participation, empowerment, infrastructure development

ABSTRAK

Van die dringendste en uitdagendste probleme wat Suid-Afrika in die gesig staar, is werkloosheid, armoede, ruimtelike herskikking, infrastrukturele verval, lae algemene geletterdheids- en opvoedkundige vlakke, en die herskikking van die landskap wat apartheid nagelaat het. In 'n poging om hierdie probleme aan te pak, het opeenvolgende demokratiese regerings programme vir infrastruktuurskepping deur middel van arbeidsintensiewe projekte van stapel gestuur. Van hierdie projekte het prominensie verkry, ontwerppryse van verskeie argiteksinstitute ontvang en aansienlike mediadekking gekry. Die sosio-ekonomiese voordele wat die projekte vir hul omgewings ingehou het, die omvang van opleiding wat gemeenskapsbetrokkenes ontvang het, en watter langtermyn voordele dit vir hulle ingehou het, is minder duidelik. Hierdie artikel neem 'n terugblik op drie sulke projekte as gevallestudies met die doel om vas te stel tot welke mate hulle daarin geslaag het om die bogenoemde probleme aan te spreek en die bydrae wat hulle tot die opheffing van hul fisiese en sosiale omgewings gebring het, te ondersoek. Die doelwit is om op grond van 'n literatuurstudie, opgevolg deur semi-gestruktureerde onderhoude met toepaslike rolspelers en visuele observasies tydens besoeke aan die projekte en analise, aanbevelings te maak aangaande die strukturering van toekomstige projekte, ten einde die voordele wat hulle mag inhou te optimaliseer in die stryd teen die genoemde probleme. Daar word aanbeveel dat programme vir infrastrukturele ontwikkeling, soos die 'Extended Public Works Programme', in hul keuse en strukturering van projekte die sosio-ekonomiese opheffing van mense en die skep van volhoubare werksgeleenthede moet prioritiseer.

Sleutelwoorde: Bouen konstruksieprojekte, gemeenskapsbetrokkenheid, bemagtiging, infrastruktuurontwikkeling

1. INTRODUCTION

Twenty-six years beyond the advent of democratic South Africa, the country has made hardly any progress in reversing some of the legacies of apartheid. Some of these persistent problems are unemployment, inequality, and spatial redress (South Africa, 2011: 233). These conditions have the potential to threaten future peaceful socio-economic development. The government and others, for instance community groups such as the so-called 'Construction Mafia' (Venter, 2020), have offered community participation in construction projects - infrastructural and other - as a way of addressing the problems of unemployment and inequality. While the problem of the 'Construction Mafia' probably requires intervention at another level, it is, in light of South Africa's high unemployment rate, imperative that state and private sector projects And ways to address these problems on a sustainable basis, where appropriate, by empowering community members so that they can remain economically active.

At the same time, various public organisations and entities initiated flagship projects to change perceptions and problems associated with apartheid planning and to redress the image of the country in light of its democratic transformation. Some of these are Freedom Park in Pretoria, the Constitutional Court, the Apartheid Museum and Walter Sisulu Square of Dedication in Johannesburg, and the Red Location Museum of Struggle in Gqeberha (Joubert, 2008). Many of these projects saw a form of community participation as a way of creating employment and empowering communities (Fitchett, 2009a: 1-2). Because of the urgency of intervention, and in view of the cost of such projects, the total value add, or overall effectiveness of many of these actions must be considered. Furthermore, it is not clear in which way building projects can best empower community members: by involving them in the conceptualisation and planning of projects, by providing labour for the construction process and/ or the manufacture of components, by functioning as formalised training initiatives, or through a combination of all of the foregoing. In addition, it will be valuable to determine the extent to which the involvement of community members has benefitted the architectural quality of the project. This study revisits three projects (the Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre, the David Klaaste Multipurpose Centre, and Harare Precinct, Square and Library) as case studies, with the aim of determining to what extent the country, the local environment and the intended beneficiaries have benefitted from such projects.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Total value and public works

According to Green (2021: online), community upliftment or development is "about people and communities being able to play a full part in decisionmaking, for example local decision-making, and so influence the decisions which affect their lives. It is also about community empowerment, for example through access to appropriate information and advice". This article takes a broader view of this concept and includes what the Community Tourism Network South Africa describes as "a strategy for Community Development and poverty alleviation through job creation and [the creation of] own business opportunities" (Community Tourism Network South Africa, 2013: 1).

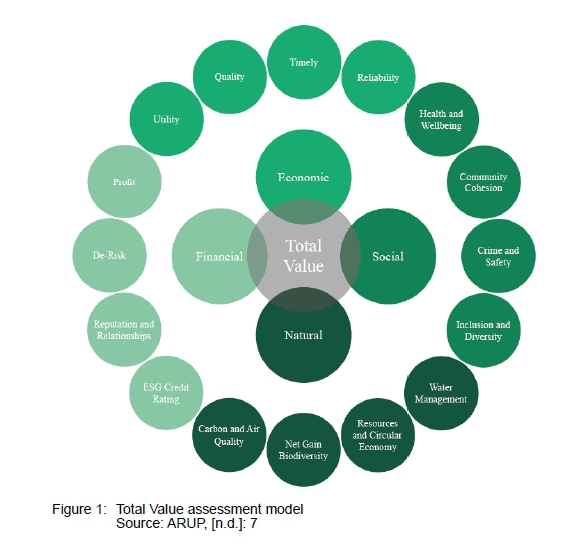

The construct of total value needs unpacking. ARUP, the global design and engineering group, argues that "[w]ithout understanding total value across the life cycle of an asset, the most valuable, socially and environmentally viable decisions cannot be made" (ARUP, [n.d.]: 8). They continue by stating that such an approach is needed for investment in infrastructure and the built environment. They explain this construct by way of the model illustrated in Figure 1, and the following formula:

Total Value = Financial Value + Economic Value +Social Value + Natural Value

• Financial Value is the value to investors (profit, essentially the Net Present Value of future cash flows arising)

• Economic Value is the value to the public purse (value for money, essentially the benefit-cost ratio)

• Social Value is the value to society (the benefits accruing to stakeholders, local communities, and end users)

• Natural Value is the value to the environment (the benefits accruing to environmental assets and their stocks and flows).

In this context, total value is understood as "the perception of worth, or benefit, that accrues to stakeholders, communities and other beneficiaries over time" (ARUP, [n.d.]: 3).1 Accordingly, this article will consider the perception of worth that accrued to the country, the local environment, and the intended beneficiaries. This is in line with ARUP's call for a more holistic approach that sets out a wider range of benefits in pursuit of a 'Total Value' approach for infrastructure investment and design decisions (ARUP, [n.d.]: 3). However, in light of this article's emphasis on community upliftment, the themes that will be explored must accentuate the value derived by those members of the community who form part of any such project (see 4 below).

2.2 Public building projects with community upliftment objectives

Since 1994, the democratic government has introduced a variety of policies, acts and initiatives such as the Public Works Programmes (PWPs) aimed at addressing both unemployment and the backlog of infrastructure needs in many of the areas disadvantaged by apartheid legislation (Splaingard, 2016: 1).

McCord (2012: 8) describes public projects or PWPs undertaken with the above views as "the provision of state-sponsored employment for the working-age poor who are unable to support themselves due to the inadequacy of market-based employment opportunities". She continues that such programmes and projects are inherently temporary in nature and that they entail the remuneration of people who provide their labour (by way of money or another commodity), by the government or by an entity on their behalf. Such projects normally have two objectives, namely to reduce poverty and to create an asset or provide a service.

McCord (2012: 9) identifies four types of PWPs:

1. Programmes offering a single, short-term episode of employment to enable consumption-smoothing (Type A).

2. Programmes offering repeated or ongoing employment as a form of income insurance (Type B).

3. Programmes promoting the labour intensification of infrastructure provision to increase aggregate employment (Type C).

4. Programmes promoting improvement in the quality of labour supply to improve future employability (Type D).

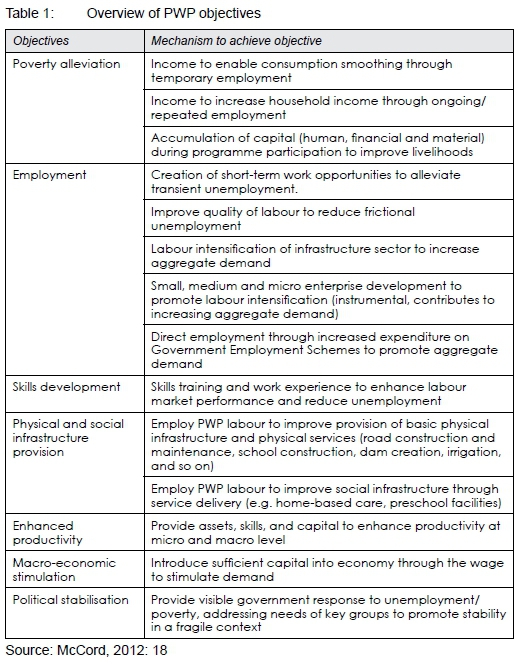

McCord (2012: 13-14) holds that, during this century, 90% of all programmes in sub-Saharan Africa fell in either the A (47%) or C (43%) typologies. According to her, PWP conception, design, objectives (see Table 1), and implementation must align with the country's unique circumstances if it is to be successful. She cites the inappropriateness of short-term relief projects in South Africa, Malawi, and Bangladesh, where chronic poverty and unemployment persist (McCord, 2012: 19). In addition, she warns that the nature of the problem that the programme seeks to address must be correctly understood. A supply side intervention will not help if there is no demand (McCord, 2005: 563). This is particularly relevant for the many South African projects that seek to provide some building skills to participants when there is already an oversupply of lowly skilled workers in the building industry.

Fitchett (2009a: 1) holds that, since 1994, the South African government has been of the view that longer term employment objectives have to be coupled to training endeavours that have as their primary aim the development of marketable skills while addressing the existing backlogs, experienced countrywide, of all forms of infrastructure. She continues by pointing out that, "for employment to be sustainable, evidence points to the importance of technical and organisational training at all levels. Moreover, for employment intensive methods to have credibility and meet the requirements of public accountability, they must be quantifiable, measurable and replicable" (Fitchett, 2009a: 3). She also points out that, in the case of outlying areas suffering from high unemployment, it should also be a priority to maximise the benefit to the local community by retaining as much of the project spend as possible within the target community, by specifying the maximum possible use of locally sourced or manufactured materials and energy, bought from local suppliers and transported by means of local transport (Fitchett, 2009a: 11). She cites Clark (1992) who pointed out that an approach to employment construction that aims to simply replace machines with manual labour will miss out on the benefits that can be acquired by specifying and creating products, materials and components, the manufacture of which require large labour inputs, thereby creating substantial local value (Fitchett, 2009a: 11). According to her, if labour is going to be the primary means of delivering the asset, training will be critical in terms of ensuring quality and productivity, in addition to skills transfer (Fitchett, 2009a: 15). She holds that a more sustainable solution, insofar as employment creation is concerned, would be to concentrate on the development of higher level technical and managerial skills. Splaingard (2016: 4) summarises this, by pointing out that, in the context of abject poverty, the challenge to the designers is to design economically empowering processes for the construction of buildings and not to simply focus on the design of beautiful buildings.

According to Mashiloane (2011: 94-95), communities and individuals must be involved in decision-making regarding aspects that affect their lives and should not be considered as mere objects of development. He further points out that the poorest members of society are also the most disempowered and that, while they might be those who are in most need of empowerment, this should not play an overtly important role in selecting community members who can form part of the project.

Policies and programmes launched by the South African government include, among others, the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) (South Africa, 1994); the Multi-Purpose Community Centre (MPCC) programme (Loebenberg, 2006: 35); the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) (Phillips, 2004), and the National Development Plan (NDP) (South Africa, 2011). More recently, the South African Economic Reconstruction and Recovery Plan (South Africa, [n.d.]: 11) was introduced.

2.2.1 Expanded Public Works Programme

While the new South African Economic Reconstruction and Recovery Plan confirms that these aims remain high on the South African government's priorities, the EPWP is the most specific and focused policy in the push to create jobs, albeit temporary, through infrastructure projects. The EPWP can be categorised as a public works programme as found in many countries. Policymakers and funders And these types of programmes attractive, because they propose a 'win-win' option by creating tangible assets, while creating employment opportunities (Baijnath, 2019: 29). As such, the EPWP aims to use public sector funds to alleviate unemployment through the creation of "temporary productive employment opportunities" with the associated training (Phillips, 2004: [s.p.]). According to McCord (2012: 57), the programme explicitly anticipated that participation would lead to sustained livelihood benefits (based on the training received). This aspect is the subject of criticism from McCord (cited by Baijnath, 2019: 31), who points to the South African government's fundamentally flawed assumption that unemployment in South Africa is a transient problem, while it is, in fact, chronic in nature.

The programme, unlike its predecessors, requires that funding comes from the normal funding sources of municipal or provincial authorities, emphasises the need for efficiency and competitiveness, stipulates that certain types of infrastructure be developed using labour-intensive methods, and insists on compliance with published guidelines and conditions. It has three goals: income relief, skills development, and asset creation. Consequently, training must be provided for all participants - even casual labour (McCutcheon & Fitchett, cited in Fitchett, 2009a: 150). The programme has a wide-ranging focus that is wider than simple infrastructure development, since it includes social services, environmental management, and public procurement. In all cases, provision is made for vocational and entrepreneurship training (Fitchett, 2009a: 150). However, Splaingard (2016: 37), citing Phillips, points out that EPWPs should be structured to equip participants with "a modicum of training and work experience which should enhance their ability to earn a living in future". Providing adequate training for sustainable employment was not the intention. According to Fitchett, the policy documents indicate that the initial focus was on those types of construction for which financially competitive employment-intensive methods exist and that the range of projects can later expand to include the construction and maintenance of public buildings. Some argue that 'building' projects, unlike certain 'construction' projects such as road building and maintenance, are inherently labour intensive (Fitchett, 2009a: 29-31) and do not require that 'labour-intensive' construction methods be used. The project that was the first case study of this research, namely the Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre (MIC), was constructed with assistance from the EPWP.

2.2.2 Multi-purpose Community Centre programme

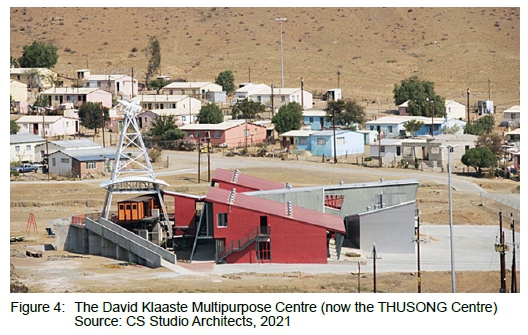

The project of the second case study, the David Klaaste Multipurpose Centre (now the THUSONG Centre), was constructed under the lesser known erstwhile Multi-purpose Community Centre (MPCC) programme (Loebenberg, 2006: 35). The programme fell under the Community-based Public Works Programme (CBPWP), itself part of the National Public Works programme which fell under the then RDP. The government, having identified the imperative to provide development communication and information to the public in order that the people actively start reshaping their lives for the better, identified multi-purpose community centres as the best means of bringing a wide range of services and products to disadvantaged communities (Rabali, 2005: 51). Target communities were, as a result of apartheid, concentrated in townships and rural areas. Two-way communication was at the core of the approach. As a rule, community members were hired to perform much of the work, albeit at a low remuneration (Adato & Haddat, 2001: i).

The programme was rolled out in 1999 with the vision of providing every South African access to information in their local area by 2010 (Rabali, 2005: 52). A minimum of six government departments would offer their services to the local community through each of these multi-purpose centres. To this end, MPCCs should encourage community participation and offer services relevant to the people's needs. However, according to Loebenberg (2006: 35), regardless of the official emphasis on community participation, should no cohesive community group with professional consultants come forward, the government would forge ahead by appointing consultants in the way they do for all other projects.

2.2.3 Urban Upgrading programme

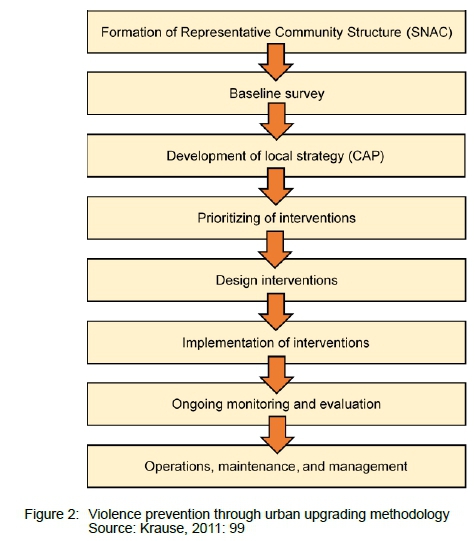

The third case study is situated in a programme that does not include the national or provincial governments. The Violence Prevention through Urban Upgrading (VPUU) programme was started at the end of 2005 and brought together the City of Cape Town, the German Development Bank, and the Khayelitsha Development Forum. The programme has a systemic area-based approach that considers developments during their entire life cycle, from inception to operations and management, with the aim of creating sustainable neighbourhoods that will improve the quality of life of the people who reside in the targeted area or neighbourhood. In this instance, economic opportunities are created in several ways, but most importantly, by the community focus, providing facilities for economic activity, education and learning, and by the communalisation of services (Krause, 2011: 98). In doing so, voluntarism has been accepted as a key developmental principle: residents provide services in exchange for access to skills development courses (Krause, 2011: 100) and benefits such as being considered for jobs involving the running of the facilities (Cooke, 2011a: 22). This longer term approach makes this programme different from the previously mentioned national attempts. Long-term sustainability is key to the project, because it is regarded as critical for the longer term socio-economic development of communities. Thus, the aim is to create "facilities and systems that are affordable and will pay for themselves beyond years of tight municipal budgets [and] decision makers who can divert funds away" (Krause, 2011: 99) from well-run feasible projects because of changes in political alliances or patronage. The requirement, enshrined in the South African Constitution, that all planning processes must promote the social and economic development of the recipient community lies at the heart of the programme (Krause, 2011: 99).

Unlike the programmes described earlier, this programme does not aim to create temporary employment; it has adopted voluntarism as a key development principle for community participation. Accordingly, residents voluntarily provide services in exchange for access to skills development courses (Krause, 2011: 100). The methodology adopted is illustrated in Figure 2.

The programme comprises Ave components:

• Infrastructure development: Construction of safe public spaces.

• Social development: Support for victims of violence and preventing more people from becoming victims.

• Institutional development: Community involvement in the delivery of services, training, and mentoring.

• Community participation: Partnerships in development.

• Knowledge management: Mentoring, learning, and evaluation.

Unlike the previously discussed programmes, the VPUU is also very specific regarding the need for community members and their role during all stages, while adopting a much longer term and holistic involvement strategy. Cooke (2011a: 19) believes that three aspects are instrumental in creating the project's success: the process and project are of equal importance; the focus is on an entire area as spatial, social, economic and managerial teams are integrated, and measures to ensure the sustained lifespan of the project are put in place.

The first two programmes reside within McCord's Type A category, while the third contains strong elements of Type B and D PWPs. South Africa's problem of chronic and ongoing unemployment requires more of the latter types of PWP instead of the emphasis on Types A and C.

3. CASE STUDIES CONTEXT

The following three projects were selected for use as case studies. The criteria used form part of the research methodology section below.

3.1 Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre - Limpopo

The Mapungubwe National Park is situated in the northernmost part of South Africa at the point where the borders of South Africa, Zimbabwe and Botswana meet. The area, characterised by dramatic geographical features, was the site of the centre of the Mapungubwe civilisation that existed between 1075 and the 1500s (Tall, 2013: 1) and comprised areas spread over parts of the above three countries. While the local population knew about the site, it was only discovered by local White farmers on the farm Greefswald in 1933. This discovery led to archaeological studies by the University of Pretoria. During these studies, the famed Golden Rhino and a variety of glass beads, skeletons, and gold artefacts, among other things, were discovered (South African History Online a [n.d.]). After initially suppressing information about the discovery, the apartheid government declared the site a national monument in the 1980s (Wikipedia, 2021).

The Greefswald farm became the property of the government and control was transferred to South African National Parks (SANPARKS) in 1999. Mapungubwe was declared a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) in July 2003 (South African History Online a [n.d.]).

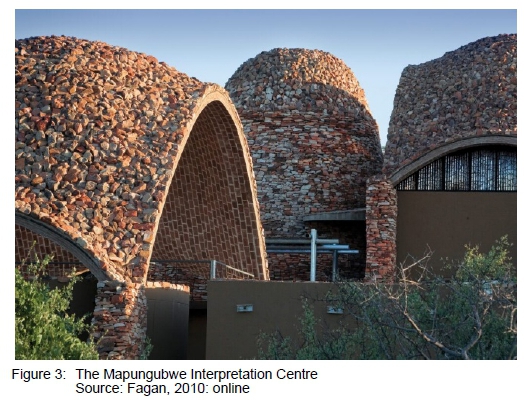

The construction of the Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre (MIC) (Figure 3) was initiated when local communities requested the return of the remains and artefacts removed from Mapungubwe Hill in the 1930s. The human remains were reburied, and it was decided that the artefacts needed to be displayed in a museum, on site, to educate and inform visitors of the area's rich heritage (South African History Online b [n.d.]).

In 2005, SANPARKS launched a competition for the design of the MIC (Fagan, 2010: online). Johannesburg-based architect Peter Rich won the competition. The MIC was constructed with support funding from the EPWP.

3.1.1 Design and construction process

Four architectural practices were invited to present designs as part of the abovementioned design competition (Splaingard, 2016: 60). The competition brief called for, among other things, that the design should be for a building that must be constructed using methods that will maximise the use of manual labour and allow for job creation and skills development (South African National Parks, 2005: 8).

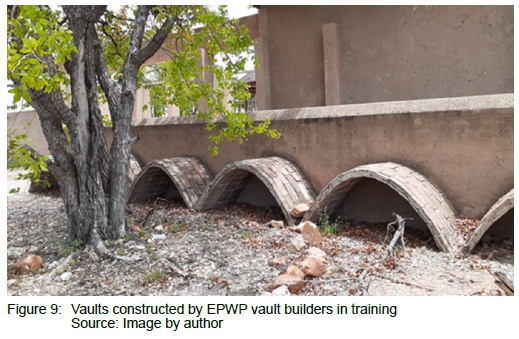

Rich (2020: personal communication) recalls that, in order to protect Mapungubwe Hill, the site of the ancient city and royal household, SANPARKS decided to locate the MIC on a mesa near the entrance gate. From here, visitors would be able to see Mapungubwe Hill when looking down the valley towards the Limpopo River. He explains that his initial concept was for a cave-like structure as an appropriately robust envelope, in which the artefacts could be securely displayed. Since different ethnic groups were contesting ownership of the area, SANPARKS explicitly asked that designs should not include any ethnic references. A chance visit by Isaac Benjamin, a British architect, well known for his Brazilian-inspired apartment buildings in Durban (City Architecture Department eThekwini Municipality [n.d.]), brought the work of a group of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) engineers, led by John Ochsendorf, to Rich's attention. The MIT group investigated the Valencian method of design and construction of thin shell domes and vaults (Ramage, Oschendorf & Rich, 2010: 255). The decision to use this method of construction using site-manufactured soil-cement tiles was not only influential in Rich's winning the competition, but it also created the opportunity to employ previously unskilled labour in the manufacture of the locally made stabilised earth tiles and the construction of the vaults and domes. The production of the tiles was separated from the main construction contract, for which an established building contractor was appointed (Splaingard, 2016: 70).

Altogether 72 people were hired for the tile-making process, while another 80 people were hired for the vault-building. The latter group was separate from the others and only people with some masonry skills were hired, due to the challenging aspects associated with vault-building. Spare EPWP workers were also used from time to time as general labour for the building process.

Because the Mapungubwe area has been farmed by White farmers as a result of apartheid land policies, the only Black Africans on the South African side of the Limpopo were labourers working on White-owned farms, the park itself and the nearby Venetia Diamond mine. According to Rich (2020: personal communication), this presented a problem that was solved by transporting local people daily to Mapungubwe from Alldays and Musina, respectively 70 and 90 km away. Not only did this add cost, but it also detracted from the environmental focus of the design proposal. Moreover, it caused friction between the EPWP workers and the main contractor's workers who could not go home every day (Splaingard, 2016: 71). It also meant that the few inhabitants from the immediate area did not gain any benefit from the project. Splaingard further reported that there was a regular turnover of EPWP workers but that, uniquely, those who performed better were allowed to remain on for the 18-month construction period. SANPARKS subsidised the wages of higher skilled workers who had been hired for the construction of the domes and vaults (Splaingard, 2016: 72). These workers were from the Elim area near Louis Trichardt, more than 100 km away, and their selection and appointment were facilitated by the main contractor who had been operating in the area for over 14 years at the time. They were not transported back and forth like the tile makers; they stayed on site in tents.

The project was completed in December 2007, but some minor structural and moisture-related problems with the domes and vaults delayed the opening to September 2012 (Splaingard, 2016: 81). The MIC project was named the winner in the category of culture at the 2009 World Architecture Festival in Barcelona and also won other accolades and prizes. It received wide publication in local and international professional and general press, thereby generating much interest in, and publicity for the Mapungubwe National Park (Fitchett, 2009b: 88).

3.2 The David Klaaste Multipurpose Centre - Laingsburg (now the THUSONG Centre)

The Centre (Figure 4), commissioned by the local town council, is located amidst the "small grey houses in a landscape of dust and stone" (Cooke, 2009: 246) of the typical Karoo township located outside the 'main' town of Laingsburg, separated in the apartheid city style by the railway line. It is located on a typically undefined open space, close to the geographical centre of the township (see Figure 5). The choice of the site was influenced by a decision to re-use two existing sheds (Cooke, 2009: 246) and was taken after a consultation process (Low, 2006: 64). Smuts (2021) points out that the choice was also influenced by the site's proximity to the N1 main route and the community's desire to use the Centre as a support centre for survivors of traffic accidents on this notorious section of the N1 route.

The project was managed by a project management committee comprising members of the community, as well as municipal and provincial officials. The building was constructed by a commercial contractor using mostly local labour (Smuts, 2021).

The purpose of the community centres built under the MPCC was to bring officially provided social and communication services to previously disadvantaged communities. In this instance, the town council also wished to give artistic expression to the role of the Black and Coloured communities in rebuilding the town, following the devastating floods that destroyed much of the town in 1981. The aim was to commemorate those who perished during the flood and to heal the emotional scarring left by the event. The red colour chosen was a result of the community describing the floodwaters as a bull rushing through town. Smuts (2021) notes that the building has since been painted white by the municipality "because white paint is cheaper than red paint". The aims also included stimulating economic activity (Low, 2006: 64).

3.2.1 Design and construction process

Smuts was approached by poet Diana Ferrus who started the process through a series of in-depth conversations with the community (Loebenberg, 2006: 36). The aim of the conversations was to And an appropriate artistic expression for the project, one that would assist in healing the scars left by the event and the apartheid government's response thereto. In this, they were joined by artist Willie Bester (Loebenberg, 2006: 36; Low, 2006: 64) who created metal concept models that were used to encourage community participation in the process of giving form to the project. After a series of design meetings, it was decided that the building should give expression to the following: the rich environment that exists in the town's environment, the flood of 1981, wind pumps as symbols of the Karoo, the nearby train lines, and prehistoric eurypterid whose remains were found in the area (Low, 2006: 64). The way in which these elements found expression in the design of the building is evident in Figure 6.

3.3 Harare Precinct, Square and Library - Khayelitsha

3.3.1 Precinct

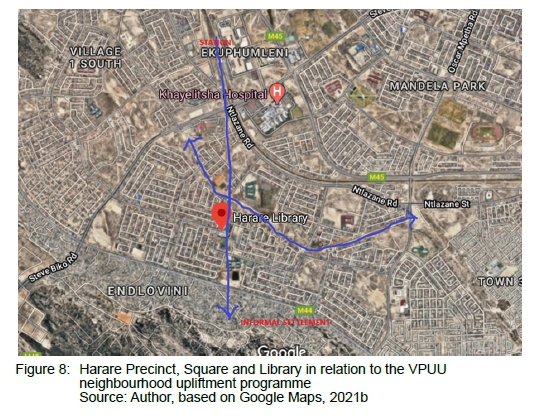

The Harare Precinct, Square and Library (Figure 7) are in the Harare neighbourhood in Khayelitsha, Cape Town. The Harare neighbourhood intervention, part of the VPUU initiative in the city, was a response aimed at reducing the violence that prevailed in the area (Krause, 2011: 100). Roughly, its intervention is situated along two pedestrian routes (see Figure 8). The first route runs due south from Khayelitsha railway station towards the Monwabisi Park informal settlement that stretches east and west on the southern side of Mew Way (Cooke, 2011a: 22-23). The second route runs along a northwest-southeast running servitude somewhat to the north of Harare Square.

The routes were made safe and accessible through a variety of interventions, developed as nodes under the VPUU. The most notable of these are, first, the construction of 'Active Boxes' at roughly 500 m intervals. Active Boxes provide not only surveillance, but also other facilities such as space for informal traders and an early childhood development (ECD) resource centre, all under the full-time surveillance of a live-in caretaker and a facility guardian system.

The second intervention was the construction of 'live-work' units at appropriate points along the pedestrian routes. These double-storey units comprise retail space at ground-floor level and housing for the storekeepers and their families at first-floor level. Krause (2011: 101) points out that together, these two typologies

serve as the glue to reinforce pedestrian desire lines, integrate facilities from a community building perspective, provide appropriate scale for economic opportunities and increase safety. These small steps of building mutual trust illustrate that healthy community participation processes are key to a process of transformation that works with individuals on a neighbourhood scale.

These routes link a series of larger public spaces, used for well-grounded larger scale facilities aimed at overcoming social, cultural, and economic exclusion and under-resourcing.

The urban design principles that guided the process are surveillance (public spaces must be well lit and watched over by occupied buildings), territoriality (well-defined boundaries between public and private spaces), and ownership (occupiers must take responsibility for the public spaces they use). Other principles include defined access and safe spaces, image, and aesthetics. People should feel good in the public spaces and take care of them. In addition, physical barriers were inserted to prevent people from slipping into spaces between buildings. A last principle is that all spaces should be well maintained and managed.

The project was recognised at the 5th UN Habitat World Urban Forum in 2010.

3.3.2 Square and Library

Harare Square is one of these nodes. It is located along the route that links the informal settlement with the station (see Figure 8). Cooke (2011a: 22) notes that the space was previously occupied by a few buildings scattered around a car parking area. It was poorly lit and provided several hiding places and no overlooking buildings, resulting in high levels of crime.

3.3.2.i Design and construction process

The Community Action Plan designated the Square for youth development and employment enrichment (Krause, 2011: 101). According to Cooke (2011a: 23), the space has been transformed to become a significant urban space. The natural slope has been turned into terraces, allowing for a variety of activities on the Square. The edges have been defined, creating a sense of enclosure through the live-work units, the new community library, a new business centre, and the previously existing facilities. Additional facilities created include a children's play area, a pension pay-out point, a multi-functional house of learning study and homework space, space for socialising and events, a community hall, and an early learning facility in the library. The business centre includes a bulk buying-and-selling cooperative and business advice centre. Together these facilities have turned the Square into a popular attraction for residents. It has also been turned into a safe area, because it is under the constant observation of the various functions surrounding it (Cooke, 2011a: 23).

The library is substantial in size and not a 'conventional' library, because it incorporates functions such as an internet café, a lounge where one can visit with friends, a children's minding place, a training centre for ECD programmes, meeting spaces, homework spaces, and a lookout area from where the Square can be observed (Cooke, 2011b: 26). Some of these facilities can be rented, thereby becoming a source of income generation. In this way, it supports the functions provided by the Square. The facilities offered also ensure that this is a popular place that attracts many to the Square, while the 'lookout' function provides additional surveillance of the area.

4. RESEARCH

4.1 Research design

The study used a qualitative stance and adopted a case study approach (Eisenhardt, 1989). It set out to determine the extent to which community participation projects address the problems of unemployment and the extent of the benefits they bring to their physical and social contexts. The qualitative approach is appropriate, because the study sets out to capture the multiple meanings, opinions and experiences of the participants involved (Cresswell 2014: 4). In this study, a literature review (Onwuegbuzie, Collins, Leech, Dellinger & Jiao, 2010) provided essential background and contextualisation for the semi-structured interviews. A semi-structured interview template was used to determine and compare community participation in the three projects, and an observation template was used to evaluate the functioning of the three projects. The reason for using both semi-structured interviews and observation was to confirm or disprove the answers obtained during the interviews and, if relevant, to have informal impromptu conversations with users and/or bystanders.

4.2 Projects and interviewees

The criteria used for the selection of the three case studies were projects that

• were constructed under a range of official programmes;

• were conceived and constructed by different government entities and different professional teams;

• are well publicised, and

• are from a variety of geographic regions.

Interviews and discussions were held with eight persons.

Mapungubwe Interpretive Centre (4) - The architect, main contractor, and the current Park Manager. The Senior Game Warden (who had been in the park during the construction process) joined the interview. Impromptu discussions were held with the restaurant attendant. The main contractor declined to be interviewed, but the researcher managed to have two telephonic conversations with him.

The David Klaaste Multipurpose Centre (3) - The architect and the Centre Manageress. Impromptu discussions were held with the security guard who has been working at the centre for over five years.

Harare Precinct, Square and Library (1) - The VPUU Manager, the library architects, and the Head Librarian. Unfortunately, the VPUU Manager and library architects declined to be interviewed and the Head Librarian's line manager would not permit her to be interviewed. Impromptu discussions then took place with the Ward Councillor who, noticing that the researcher was making notes and taking photographs, presented himself for a discussion.

4.3 Data collection

The first part of the study comprised a literature review to compile essential background and contextualisation for the semi-structured interviews that comprised the second phase of the study. Boote and Beile (2005: 5) hold that "[a] thorough, sophisticated literature review is the foundation and inspiration for substantial, useful research". The literature reviews were also used for the descriptions of the individual projects and general background descriptions (see 3: Case Study contexts).

The second part of the study comprised semi-structured interviews. A semi-structured interview template was used to guide the discussion with relevant role players. The discussion was structured along the following three themes:

• The socio-economic benefits to the community and local area (essentially the four aspects of 'total value' rolled into one).

• Skills transfer to the community participants.

• Long-term benefits to the community participants.

The themes were derived from a combination of ARUP's definition of 'total value add' (ARUP, [n.d]: 10)2 and the objectives of the EPWP (refer to 2.1.1). The purpose of the semi-structured interview was to obtain information not revealed in the literature review. The interview template, which included an Informed Consent Form, comprised 12 basic questions formulated around the three chosen themes. The questions related to the training offered to community participants prior to and during the project, the role of community participants during the design phase, the role of the community participants during the construction phase, the extent to which the community participants managed to capitalise on the training and experience gained from the project, the extent to which the project brought socio-economic advantage to the local area and community, the functioning of the facility, and the degree to which the facility created fulfilled its intended mandate.

Due to lockdown regulations in force during the early part of the research, interviews were conducted using two software applications, namely WhatsApp and Microsoft Teams. The Microsoft Teams interviews were recorded and the WhatsApp interview was recorded by Dictaphone. The WhatsApp interview was transcribed for further thematic analysis. Where this was not possible, questions were asked by telephone. With the easing of restrictions, some interviews were conducted face-to-face and recorded by Dictaphone and by notes taken during the conversation. Where possible, interviewees were sent the questions with an 'informed consent' form and background to the study in advance. Background was also provided during telephone conversations or in electronic mail messages used to arrange the interviews.

The third part of the research comprised a visit to the case study buildings and surrounding areas. In some instances, the visits coincided with the semi-structured interviews. Visits included impromptu discussions with individuals active on the site or in its immediate vicinity. An observation template was developed for use during the visit. It required the researcher to examine and record the current state of the facility, the extent to which it was used, any new additions to the building, compare current function with the intended function, and any socio-economic opportunities unlocked by the project in its immediate surroundings. Observations were recorded by way of notes taken and photographs.

4.4 Data analysis and interpretation of findings

Due to the limited number of interviews and the relatively short interviews, analysis could be done manually. As a first step, the transcripts, notes and recordings containing data were organised and prepared for analysis. The next step was a thorough reading of all notes and transcripts and a listening to all recordings on a case study by case study basis, while taking notes of statements made, impressions, questions and listing all points that warrant reflection and/or comparison while viewing all photographs taken. Once a thorough understanding of all the data for each case study was arrived at, the data was reviewed again and organised per theme (see 4.3). The data were reviewed once more before a summary for each theme and for each case study was compiled.

4.5 Limitations

As indicated earlier, not all those identified for interviews agreed to formal interviews. While reasons were not always provided, the architects responsible for the Harare Library and the VPUU staff indicated that this was due to time pressure. This could unfortunately impact on the reliability of the data regarding the last case study.

5. FINDINGS

5.1. Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre

5.1.1 Long-term outcomes and total value add

Revisiting the benefits created nine years since it was opened and 14 years after its completion, the project reveals the following regarding longer term benefits of the project.

5.1.1.i Socio-economic benefits to the community and local area

The MIC represents a major physical asset for the Mapungubwe National Park and the country. It is appropriate for its function and SANPARKS must be applauded for the vision they displayed in siting the project and the whole process from the design competition to the emphasis on poverty relief and creating as much benefit as possible for the area. Some jobs were created for the various staff members directly associated with the operation of the Centre. However, notwithstanding the publicity generated by the MIC, and despite the assertions by the park manager (Strauss, 2020: personal communication) that the MIC has resulted in an increase in visitors to the park, there is no evidence to support these claims. Splaingard (2016: 130) published visitors' numbers prior to and after the opening of the MIC, which show that there was no immediate change, something that could have stimulated informal opportunities for sellers of various commodities such as curios, artefacts, and firewood. It could, in addition, have created permanent employment opportunities if privately owned lodges or guest houses could be established in the area or in the park itself. Therefore, as far as the local communities are concerned, it has not brought any longer term benefit.

5.1.1.ii Skills transfer to the community participants

Tile makers received two weeks' training from MIT graduate Mathew Hodge. In addition, SANPARKS set out to develop the tile makers to form small enterprises who could take over and manage the tile making (Splaingard, 2016: 73). Three EPWP workers, who had Grade-12 certificates, attended a National Qualifications Framework Level 2 business training course (Splaingard, 2016: 74). Upon completion of the course, the three small, medium, and macro enterprises (SMMEs) that had been formed were registered with the Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB). Each SMME then hired a team of 11 workers and were tasked with ensuring that their workers attend regularly and that they (the SMMEs) meet production targets and administer payment. SANPARKS managed quality. The three SMMEs were given permission to tender for future SANPARKS projects (Splaingard, 2016: 74). At times, the main contractor was asked to employ excess tile-making EPWP workers he did not need, simply in order to create employment. However, after an ongoing selection process, the best workers were trained by his team to perform a variety of construction-related tasks.

The vault builders received training from James Bellamy, a New Zealand engineer appointed to supervise the vault construction (Splaingard, 2016: 77). Vaults constructed during this process are shown in Figure 9.

Splaingard states that he could not verify SANPARKS' claims that they also attended a variety of life-skills courses. He refers to Bellamy's reports that there was significant tension and friction between the vault builders and the main contractor's site managers, apparently caused by the lower wages earned by the vault builders (as per the EPWP rules). Furthermore, there was a high turnover of members in the EPWP vault-building team. He cites Bellamy's statement that people dynamics became the most difficult part of the project (Splaingard, 2016: 78). Bellamy further reported that the vault-building team took a great deal of pride in their work and that vault building here required a strict differentiation of roles and discipline.

Glaringly, the problem is that the tile-making SMMEs were experienced only at tile making, which gave rise to pertinent questions. Given the design imperatives that led to the adoption of the domed structure, what were the chances of future construction projects where these skills would be required? Why were some not rather trained and employed to undertake the maintenance of the MIC and other SANPARKS facilities at Mapungubwe? As pointed out by Fitchett (2009a: 197), this poverty relief project did not focus on productivity and efficiency of production. This could partly be because encouraging higher production would mean that the EPWP teams might start competing with established contractors in terms of incomes earned - something not allowed by EPWP rules. Nonetheless, one must ask how SMMEs, with this background, would ever be able to compete on the open market.

As far as empowerment and employment creation are concerned, the situation is somewhat disappointing. The author could not establish any long-term benefits derived by the EPWP workers. Telephonic conversations with the main contractor, who facilitated the employment of all the workers from the Musina and Elim areas still involved in building projects in the northern parts of the Limpopo province, revealed that the SMMEs formed have apparently disappeared, while attempts to contact any of the workers through him were unsuccessful (Van Staden, 2020). He could not establish contact with any of the persons involved. However, these workers may simply have moved to another area.

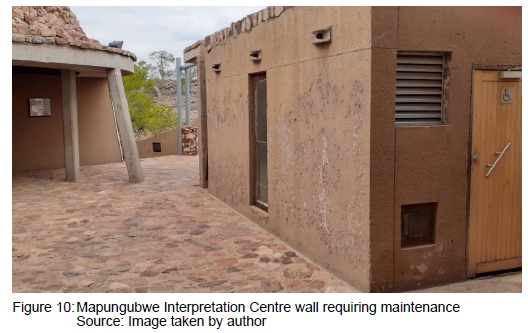

According to Splaingard (2016: 83), the project site manager indicated that "a few" temporary employees had been hired for longer term work and that one of the tile-making SMMEs was employed by SANPARKS on a two- to three-year contract. However, the current (2020) park manager and senior game warden indicated in interviews that they were unaware of any MIC EPWP beneficiaries who are currently employed or contracted by the park, although the MIC is in urgent need of maintenance (see Figure 10).

While SANPARKS are clear about the fact that they had no long-term relationship in mind (Splaingard, 2016: 82), the situation implies that one of the objectives of the EPWP, namely the provision of job opportunities that includes a training component in order to improve long-term employability (Phillips, cited by Fitchett, 2009a: 129), was not realised. While the project provided a measure of poverty relief and some training, it apparently failed to offer any longer term economic benefit to the EPWP workers and hence, the local communities, because of the unique nature of the skills taught to them. These skills cannot be transferred to other projects.

In summary, it can be mentioned that the project was successful in providing short-term poverty relief and in creating an asset, because it has enhanced the cultural and educational value of the park. It has not increased visitor numbers to the park, something that could have stimulated informal opportunities for sellers of various commodities such as curios, artefacts, and firewood. It is also worth noting that the South African building arena has many low-trained persons seeking employment. Sending more people into this area equates to setting them up for failure and will not provide sustainable benefits to the individuals or the country. On the other hand, it is a project where the community-participation aspect shaped and brought about the design. The MIC can be viewed as a good example of community-enabled architecture.

5.2 The David Klaaste Multipurpose Centre (now the THUSONG Centre)

5.2.1 Long-term outcomes and total value add

5.2.1.i Socio-economic benefits to the community and local area

The Centre represents an important physical asset for the town of Laingsburg and more importantly for the Goldnerville township, where it is located. This township is a typical apartheid-type township that offers very little by way of public, social, or commercial facilities. While the siting of the Centre provided an opportunity to establish a link between the township and the 'town', the community elected that it be placed in its current location.

It thus provides a focus point for the otherwise featureless area without any public spaces or meaningful public facilities beyond the school. It does provide a possible starting point for concerted efforts to improve the spatial and urban qualities of the area.

Because of the process followed and the extended focus (including dealing with the trauma associated with the floods and the way in which the community contributed to the rebuilding process), it is accepted that the Centre contributed to the social and sociological well-being of the community. Although the value of this aspect cannot be quantified, this aspect alone contributed significantly to its long-term value add. In addition, training was offered to several community members who were employed in the construction of the project. Permanent jobs were created, such as the Centre's manageress, security guards, gardener, and cleaners (Smuts, 2021). In fact, all persons employed in the Centre, aside from professionals such as social workers and paramedics, are from the local community (Gouws, 2021).

On visiting the Centre in 2021, the author noted that the Centre is used extensively and still provides offices for a range of government departments (see Figure 11). The Centre is well maintained and has been extended to include a gymnasium. A children's play area has been added, with trees (see Figure 12) and a piece of lawn.

What used to be the restaurant now functions as a workshop that is used as part of a community craft-training initiative, and a small library with internet access has been squeezed into an open space underneath the staircase. The Centre's manageress indicated that the community values the Centre. This is evidenced by the absence of any acts of vandalism. Unfortunately, according to the local security guard, the Centre does not appear to attract any visitors or tourists to this part of the town. The author observed that a feeding scheme is offered, whereby cooked meals are provided to community members. This facility is used as a grant payment point.

5.2.1.ii Skills transfer to the community participants

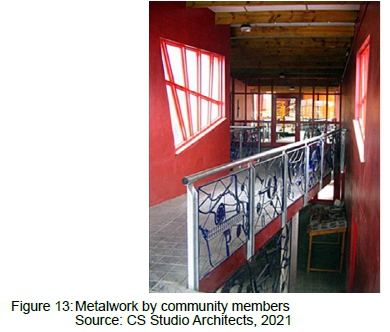

Artist Willie Bester trained local community members in the welding of various of the metalwork items such as the handrails made from farmyard scrap metal (see Figure 13). Community members were also trained and used for the electrical installation (Low, 2006: 36; Smuts, 2021).

Those who received training in welding and electrical work could not capitalise on the training received and were soon unemployed again (Gouws, 2021).

It is clear that the Centre has added considerably to the empowerment of the local community. It created both temporary and permanent jobs and continues to provide training to the community. It has turned into the central point of the township, where the community can access most of the government departments, a library, gymnasium, community hall, and relief centre. Smuts (2021)3 attributes the success of the Centre to the extended consultation that took place before design and construction started.

5.3 Harare Precinct, Square and Library - Khayelitsha

5.3.1 Long-term outcomes and total value add

5.3.1.i Socio-economic benefits to the community and local area

From the literature it appears that this programme and the Harare Precinct, Square and Library, with its long-term enablement focus, brought restricted immediate and short-term poverty relief. Few short-term or temporary jobs were created.

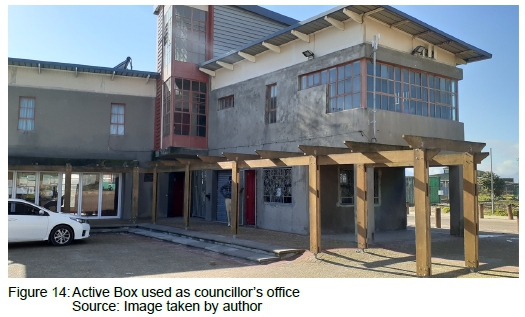

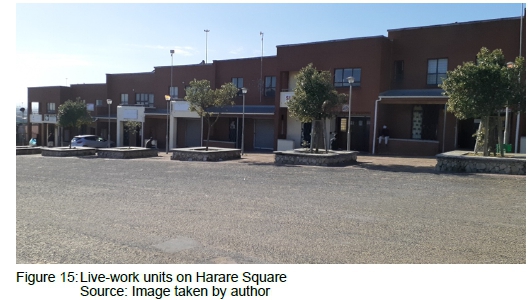

From a visit to the area in June 2021, the purpose of the project was and remains to improve people's quality of life (Krause, 2011: 98). This aim has been achieved. Opportunities for trade have been created. A safer environment that also offers opportunities for people to improve their economic and financial situations and to make a long-term improvement to their quality of life is in place. As in the other projects studied, assets were created and the physical environment - the public spatial environment - was uplifted. Importantly, and uniquely, measures were introduced to ensure the long-term sustainability of the project. Regrettably, it seems that not everything turned out as intended. The three Active Boxes are now used as offices; the one on Harare Square by the VPUU, the next one by the area's city councillor for offices (see Figure 14) and the one closest to the railway station seems to be leased out. This was confirmed by the city councillor, Councillor Gabuza, in informal conversation outside his office (Gabuza, 2021). Some of the live/work units are in use (see Figure 15) but not all. The library is doing well and was a hub of activity. Furthermore, some long-term job opportunities were created for the supervisors and caretakers of the facilities.

5.3.1.ii Skills transfer to the community participants

Skills transfer through the voucher system meant that, apart from the leadership, organisational, surveying, participatory and communication skills learnt through volunteering to become part of the initiative, participants could choose in which fields they would prefer to receive training or education - linked to their own interests, talents and skills shortages. In addition, they learnt about the need for civic mindedness.

Unfortunately, no VPUU staff, the architects of the library or the librarian could be interviewed to confirm visual observations or to establish if any long-term job opportunities had been created, or what the problems were that have appeared since completion.4 Furthermore, the author could not learn more about the 'voucher system' used to compensate volunteers. Councillor Gabuza was not aware of any long-term employment created for the community-based participants.

5.4 Comparison

When the three cases are compared to one another, the three projects can be and were viewed as going from the least 'community'-focused to the most 'community'-focused. It must be said that the objectives of the three projects differed markedly: from (i) creating a Atting home for historical artefacts, artefacts that reveal apartheid's false premises and lies, providing pride while delivering a measure of poverty relief and a smidgen of skills training to (ii) establishing a project that aims to provide a facility to a traumatised and neglected community, one that will help them come to terms with a past event in order to help restore their dignity and self-worth, to (iii) producing a project aimed entirely at providing a safer and enabling environment to a disadvantaged community, as a result offering stepping stones towards long-term employment. In fact, the aims of the three projects differ to the extent that one might say that, in terms of the aims of this study, it is not a fair comparison, and that might well be true.

However, the comparison does reveal some valuable pointers. The MIC was constructed under the EPWP, a project that attempts to combine infrastructure provision with poverty reduction and limited skills development. The biggest problem with this approach is that the skills learnt by the participants are not needed in the open labour market, because there is already an abundance of semi-skilled construction and building workers, as can be noted on any visit to a building-material supplier. It also highlights that those skills taught must be transferable: the vault-construction skills taught are not sufficient, as the design and construction of the vaults, in practice and by law, require the services of a specialist structural engineer. This means that, in practical terms, the workers have only acquired team-working and organisational skills.

Besides creating a handful of jobs, the MIC itself also falls short of providing any long-term benefits to the people of the area: tour groups that arrive by bus leave without staying over or spending any money, because there is no accommodation for visitor groups - even the day visitor area is deserted and unkempt.

The David Klaaste Multi-Purpose Community Centre, like the MIC, did not go beyond creating a single facility, one that did at least reach out to create a more enabling or positive environment. It has done nothing to unite the town divided by apartheid planning or to improve the urban qualities of the apartheid-style township - the only exception is that a children's playground has been built. Due to space restrictions, it does not provide the type of facilities such as a proper library, study or work space with internet connectivity, trading stalls, and a long-distance bus terminus that can address the socio-economic situation of the inhabitants in the long term.

Because of these shortcomings, both projects created by the national government have added limited value to their environments and the people who reside in them. However, it can be said that, in both cases, the architects and the designers of the facilities did as much as they could to provide facilities and designs that add value to their environments. To have achieved more, the programmes under which they were built and the briefs for the projects should have been more holistic and inclusive in their aims. Their prioritisation of infrastructural facility and not socio-economic development has brought limited benefit to the areas involved; a measure of temporary poverty relief being the most prominent.

The Harare Precinct project, driven by the Cape Town local government, focused primarily on addressing environmental and socio-economic problems through infrastructural development. This project has resulted in the introduction of infrastructure that primarily provides safer and appropriate mobility and access, while also offering facilities and access to education that will allow residents to improve their education over the long term and thereby their income-earning potential. In addition, it has enhanced the urban quality of the area and has acknowledged that most of the inhabitants travel by foot and should be able to do so in well-made public spaces.

6. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

It cannot be denied that physical infrastructure can provide assets that can and do offer economic benefit and opportunity. However, in a country such as South Africa, with immense socio-economic challenges, the question should not simply be: How can the provision of physical infrastructure projects be used to provide some temporary employment opportunities (or poverty relief) and as a bonus, training and skills development? As highlighted by McCord (see 2 above), unemployment in South Africa is chronic and not a temporary occurrence following some catastrophe. As far as could be established, not one of the three studied projects created any sustainable or long-term employment opportunities to those who were employed to be part of the design and construction process. However, they have created some opportunities for others. Thus, from a long-term empowerment point of view, they had limited success. From an employment creation point of view, all three can be said to have largely provided no more than temporary poverty relief.

Therefore, based on the study, it is suggested that the aim of projects such as the EPWP should rather be the following: 'How best can we provide sustainable socio-economic upliftment and opportunities while providing infrastructure or physical assets?' and not 'How can we provide some temporary poverty relief while providing physical assets?'

This suggestion resonates with the latest views expressed by the National Planning Commission who, in a recently published paper, suggests certain course corrections required by government, should it wish to achieve the NDP's aim of eradicating poverty by 2030 (Paton, 2021: 2). According to Paton, the "single most important" correction required is investment in favour of people and the institutions that develop people. In terms of this study, it would be to develop infrastructure that will empower people, while facilitating economic growth. In other words, PWP projects that cover the full range of objectives listed in Table 1 should form part of the strategy to improve the long-term situation of citizens.

Consequently, Fitchett's (2009a: 277) parameters that can significantly increase employment generated through the design and construction of small public buildings should be revised to include the following:

• A programme that focuses primarily on the socio-economic upliftment and sustainable empowerment of people.

• A programme approach that capitalises on initial overheads.

• An integrated training programme or access to appropriate education or training programmes.

• Choice of materials.

• Location and method of sourcing and manufacturing materials and components.

• Design and detailing that minimise material waste.

• Exemplary management that devolves tasks to the lowest responsible level.

• An ethos of continual improvement and commitment to quality management.

Furthermore, it is suggested that a voucher system be introduced, whereby participants in EPWP or similar public or private schemes can earn access to officially sanctioned and registered education or training courses and programmes that will allow them to qualify themselves (incrementally if needs be) for careers that suit their individual aptitudes and/or the needs of the labour market. Note should be taken of Smut's view that extensive community consultation before the start of the project is of utmost importance. Thus, it is recommended that the EPWP be revised to incorporate the abovementioned parameters to eradicate the chronic poverty and unemployment.

REFERENCES

Adato, M. & Haddad, L. 2001. Targeting poverty through community-based public works programmes: Experience from South Africa. Journal of Development Studies, 38(3), pp. 1-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380412331322321 [ Links ]

ARUP. [n.d.]. Making the total value case for investment in infrastructure and the built environment. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.arup.com/-/media/arup/files/publications/t/total-value-paper.pdf> [Accessed: 19 October 2021]. [ Links ]

Baijnath, R. 2019. Writing her in: An African feminist exploration into the life herstory narrative of Dimakatso, a woman participant in the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) at Leratong Hospital in Gauteng, South Africa. South African Review of Sociology 50(2), pp. 27-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/21528586.2019.1666735 [ Links ]

Boote, D.N. & Beile, P. 2005. Scholars before researchers: On the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation. Educational Researcher, 34(6), pp. 3-15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X034006003 [ Links ]

CCNI Architects. 2021. Harare Library - Khayelitsha. [Online]. Available at: <http://www.ccnia.co.za/projects/public/harare-library-khayelitsha/> [Accessed: 8 June 2021]. [ Links ]

City Architecture Department eThekwini Municipality. [n.d.]. Durban City Architects Guide: Crofton and Benjamin. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.kznia.org.za/sites/default/flles/building-brochures/Crofton-Benjamin.pdf> [Accessed: 9 February 2021]. [ Links ]

Community Tourism Network South Africa. 2013. Community beneficiation. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.tourism.gov.za/CurrentProjects/Documents/CCTNSA%20Tourism %20Development%20Presentation%20-%20Victor%20Sibeko.pdf> [Accessed: 19 October 2021]. [ Links ]

Cooke, J. 2009. David Klaaste Multipurpose Centre (2005). In: Joubert, O. (Ed.). 10+ years, 100 Buildings, Architecture in a democratic South Africa, Cape Town: Bell-Roberts Publishing, pp. 246-249. [ Links ]

Cooke, J. 2011a. The violence prevention through Urban Upgrading (VPUU) Programme - Khayelitsha. Architecture South Africa May/June, pp. 19-23. [ Links ]

Cooke, J. 2011b. Harare Library. Architecture South Africa May/June, pp. 26-29. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. 2014. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

CS Studio Architects. 2021. Projects - Community Development - Dawid Klaaste Purpose Centre. [Online]. Available at: <https://csstudio.co.za/laingsburg.html> [Accessed: 8 June 2021]. [ Links ]

Eisenhardt, K.M. 1989. Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review 14(4), pp. 532-550. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308385 [ Links ]

Fagan, G. 2010. Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre by Peter Rich Architects, Mapungubwe National Park, South Africa. The Architectural Review. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.architectural-review.com/today/mapungubwe-interpretation-centre-by-peter-rich-architects-mapungubwe-national-park-south-africa> [Accessed: 5 February 2021]. [ Links ]

Fitchett, A.S. 2009a. Skills development and employment creation through small public buildings in South Africa. Unpublished PhD thesis. Johannesburg, South Africa: University of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Fitchett, A.S. 2009b. Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre, Mapungubwe National Park. Digest of South African Architecture 2009: A review of work completed in 2009, pp. 88-90. [ Links ]

Gabuza, A. Cape Town City Councillor. 2021. Personal communication [Author's notes], 1 June. [ Links ]

Google Maps. 2021a. Laingsburg Municipality [Online]. Available at: <www.google.co.za/maps/place/Laingsburg,+6900/@-33.1953829,20.8647108,527m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m5!3m4!1s0x1dd36e55a734b90b:0x5 7b5b6c13e0b8bce!8m2!3d-33.1972101!4d20.8612525?hl=en> [Accessed: 4 March 2021]. [ Links ]

Google Maps. 2021b. Harare Library, Ncumo Road, Harare, Cape Town. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.google.co.za/maps/place/Harare+Library/@-34.0579068,18.6686849,441m/data=!3m2!1e3!4b1!4m5!3m4!1s0x1dcc495361c8959d:0x305 52716d8dbb2e2!8m2!3d-34.0578802!4d18.6707614?hl=en> [Accessed: 8 June 2021]. [ Links ]

Gouws, S, Laingsburg Thusong Centre Manageress. 2021. Personal communication. [Author's notes], 2 June. [ Links ]

Green, P. 2021. Community involvement. Appropedia [Online]. Available at: <https://www.appropedia.org/Community_involvement> [Accessed: 19 October 2021]. [ Links ]

Krause, M. 2011.Violence prevention through urban upgrading. Digest of South African Architecture: A review of work done in 2011: 98-103. [ Links ]

Loebenberg, A. 2006. Government-driven community centres: Architectural results of the Multi-purpose Community Centre Programme. Architecture South Africa November/December, pp. 34-37. [ Links ]

Low, I. 2006. Laingsburg Multi-purpose Centre, Western Cape. Digest of South African Architecture 2005-2006, pp. 64-65. [ Links ]

Mashiloane, L.S. 2011. Role of community participation in the delivery of low-cost housing in South Africa. Minor dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

McCord, A. 2005. A critical evaluation of training within the South African National Public Works Programme. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 57(4), pp. 563-586. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820500200302 [ Links ]

McCord, A. 2012. Public works and social protection in sub-Saharan Africa: Do public works work for the poor? New York: United Nations University Press. [ Links ]

Onwuegbuzie, A.J., Collins, K.M.T., Leech, N.L., Dellinger, A.B. & Jiao, Q.G. 2010. A meta-framework for conducting mixed research syntheses for stress and coping researchers and beyond. In: Gates, G.S., Gmelch, W.H. & Wolverton, M. (Eds). Toward a broader understanding of stress and coping: Mixed methods approaches. The Research on Stress and Coping in Education Series (5). Charlotte, NC: Information Age, pp. 169-211. [ Links ]

Paton, C. 2021. People and institutions will steer SA towards growth, say planners: NPC reports into what country needs to correct course. Business Day, 22 January, p. 2. [ Links ]

Phillips S. 2004. The Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP): Overcoming underdevelopment in South Africa's second economy. Pretoria: Department of Public Works. [ Links ]

Rabali, H. 2005. The role of Multi-purpose Community Centre (MPCC) service and information providers towards improving quality of community life - A case of Sebokeng. Unpublished MA mini-dissertation. Vanderbijlpark, South Africa: North-West University. [ Links ]

Ramage, M., Ochsendorf, J. & Rich, P. 2010. Sustainable shells: New African vaults built with soil-cement tiles. Journal of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures, 51(166), pp. 255-261. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.39877 [ Links ]

Rich, P. 2020. Architect, Peter Rich Architects. Interview by author. [Transcript]. 2 April. Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Smuts, C. 2021. Architect, CS Studio Architects. Interview by author. [Recording]. 10 May. [ Links ]

South Africa. 1994. Reconstruction and Development White Paper. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

South Africa. [n.d.]. The South African Economic Reconstruction and Recovery Plan. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202010/south-african-economic-reconstruction-and-recovery-plan.pdf> [Accessed: 25 January 2021]. [ Links ]

South Africa. 2011. National Planning Commission. National Development Plan: Vision for 2030. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/devplan2.pdf > [Accessed: 25 January 2021]. [ Links ]

South African History Online a. [n.d.]. Mapungubwe. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/mapungubwe> [Accessed: 5 February 2021]. [ Links ]

South African History online b. [n.d.] Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.sahistory.org.za/place/mapungubwe-interpretation-centre> [Accessed: 5 February 2021]. [ Links ]

South African National Parks. 2005. New interpretation centre and amenities at Mapungubwe National Park and World Heritage Site. Unpublished competition brief. Pretoria: South African National Parks. [ Links ]

Splaingard, D. 2016. DesignWork: A study of public works programmes in South African architectural projects. Unpublished MPhil in Architecture thesis. Cape Town, South Africa: University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Strauss, C. Park Manager, Mapungubwe National Park. 2020. Interview by author [Recorded]. 12 November, Mapungubwe. [ Links ]

Tall, J. 2013. Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre, Limpopo, South Africa. 2013 On-site report prepared for the 2011-2013 cycle of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. [Online]. Available at: <https://s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/media.archnet.org/system/publications/contents/9642/original/DTP02124. pdf?1398414734> [Accessed: 5 February 2021]. [ Links ]

Venter, I. 2020. SAPS, industry form partnership to combat construction mafia. Engineering News, 2 April. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/saps-industry-form-partnership-to-combat-construction-mafia-2020-04-02/rep_id:4136> [Accessed: 28 June 2021]. [ Links ]

Wikipedia. 2021 (last update). Kingdom of Mapungubwe. [Online]. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Mapungubwe [Accessed: 5 February 2021]. [ Links ]

Received: June 2021

Peer reviewed and revised: July 2021

Published: December 2021

DECLARATION: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

1 Aspects such as project costs and profitability or income are beyond the aim of this article, as the case studies are community facilities. Income or profitability are not important issues.

2 Total Value = Financial Value + Economic Value +Social Value + Natural Value

3 Smuts through her practice has designed a large number of noted community centres and facilities in both the Western Cape and the Eastern Cape provinces.

4 Various attempts were made to interview staff at the VPUU offices. Like the architects of the Harare library, they were all 'too busy'; calls were not returned and e-mails were ignored.