Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Acta Academica

versión On-line ISSN 2415-0479

versión impresa ISSN 0587-2405

Acta acad. (Bloemfontein, Online) vol.55 no.2 Bloemfontein 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.38140/aa.v55i2.7727

ARTICLES

A love note to our future selves': The coaching imperative in platform cultures

Panos Kompatsiaris

HSE University, Moscow; IULM University, Milan. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2452-6109; E-mail: panoskompa@gmaii.com

ABSTRACT

This article looks at the imperative of life coaching on media platforms as a broader social technology and a technology of the self. Life coaching suggests that a better future self can be achieved through the constant training of one's personality, body, taste, preferences, emotions, image, communication skills, and a myriad of other life aspects. I understand the coaching imperative as a wider mandate of self-improvement standing at the crossroads of the wellness and spirituality industries (e.g. mindfulness, yoga, self-help), the body industry (e.g. fitness, health, exercise), guidance and counselling (e.g. 'how to become a millionaire', 'how to become an alpha male') and the affordances of media platforms. Using literature on micro-celebrities and platform studies as well as research on life coach training programmes, books, and instructions, I argue that the 'self' in this narrative is an ongoing project, constantly under supervision and reframing. The imperative to improve assembles a productive process composed of technical infrastructure, e.g. self-tracking devices, tests, and apps, and labour power, e.g. self-labour, the labour of the therapist, the coach, and the analyst.

Keywords: life coaching, platforms, inspirational capital, self-labour, social technologies

Introduction

In an early 2023 episode of the Life Coach School Podcast, the "master of self-discipline", Monica Levi, tells her audience that self-discipline, which is "something that you don't want to do", is indispensable for achieving a superior future self. "Self-discipline," she continues, "is really, I think, in so many ways truly a love note connection to our future selves." (2023) In this imaginary love letter, our 'present self', which poses as the author of the note, declares commitment to the superior future self, which is the self-in-the-making. Commitment, though, as in religious ascesis, demands the denunciation of present-time joys for the sake of a future vision, the vision of an advanced self, who will be actualized and successful. In life coaching cultures, the modality of sacrifice that Levi suggests is one of the modalities through which this vision can be achieved; others include the continuous introspection of our actions, the meticulous analysis of our emotions, the monitoring of our thoughts, the reward for accomplishments that bring us closer to our dreams, and overall, the constant training of ourselves to grow a leader's mindset. The self in this narrative is a project constantly under supervision and reframing that strives to achieve this future vision. This future vision, in turn, can regulate present day thoughts, actions, endeavours, and plans.

Life coaching is part of a broader process of psychologising political, social, and economic affairs that has spread globally in the past few decades (Nehring et al. 2020), which Eva Illouz refers to as the "therapeutic discourse" (2008: 6). This discourse interpellates human beings on the grounds of a future superior self that needs to maintain a vision leading to fulfilment and actualisation. It is a vision that pertains to the "self-enclosed individualism" of neoliberal culture (Wilson 2017: 6), and sidesteps questions of social transformation and inequality. Life coaching is also a thriving business: according to the International Coaching Federation, the main institutional body regulating a rather unregulated industry, coaching is the second fastest growing industry in the world, an average yearly growth of 6.7% (Health Coach Institute 2023). To make a slightly provocative analogy, the self is the new oil, whose unearthing gathers a productive process around it, congealing technical infrastructure (e.g. self-tracking devices, tests, and apps, among others) and labour power (e.g. self-labour, the labour of the therapist, the coach, the analyst, and so on) for creating economic value.

This article looks at the imperative of life coaching on media platforms as a broader social technology and a technology of the self. I argue that life coaching posits the idea of a better future self that can be achieved under constant training and introspection, which constitutes a diffused command in platform capitalism (Srnicek 2017). Canonised via social media platforms and apps, coaching requires the never-ending training of one's personality, body, taste, preferences, emotions, image, communication skills, and a myriad of other life aspects. I understand the coaching imperative not only within the narrower professional field of certified coaches (although this is "very loosely regulated" as well [Aboujaoude 2020: 3]) but as a wider mandate of self-improvement standing at the crossroads of the wellness and spirituality industries (e.g. mindfulness, yoga, self-help), the body industry (e.g. fitness, health, exercise), guidance (e.g. 'how to become a millionaire', 'how to become an alpha male') and new media platforms. Thanks to the proliferation of media platforms, especially Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, and Tik-Tok, which offer unparalleled promotional and networking opportunities to aspiring coaches, the latter can embody motivational personas in a variety of formats, including videos, podcasts, seminars, photos, and self-descriptions. The coaching imperative is then part of neoliberal media culture, which is typically characterised by an intense preoccupation with the self and its turbulences.

I employ a "compositional methodology", according to which the "activity of composing is not given in advance of a problem but is rather ever forming and transforming across a problem space" (Lury 2020: 5). This then involves an iterative-inductive approach to the study of the coaching imperative (O'Reilly 2008), letting the theory and material inform each other during the research process. I present an initial selection of coaching narratives and personas functioning as preliminary case studies based on some of the most popular coaching courses offered on the educational platform Udemy ('Transformation Services' by Joeel & Natalie Rivera and 'Achology' by Kain Ramsay) and the most popular English-speaking coaching schools (such as the Life Coach School), which led me to other coaches and coaching communities as well as authoritative figures of the field (such as Tony Robbins). The material I draw from involves fragments from the two coaching courses I took so that I became a 'certified' coach myself, the posts of the instructors in social media, their books and messages in groups and mailing lists, as well as from listening to other coaching podcasts (especially the Life Coach School Podcast) and bookmarking relevant fragments of the coaching discourse that I encountered in my daily social media activity. In that way, I familiarised myself with the coaching imperative, which, although diverse and often contradictory, incorporates more or less stable goals that are expressed by generic signifiers such as 'become a leader', 'self-actualise', 'self-improve' and 'become happy', which in turn inform the personality traits one needs to cultivate, e.g. confidence, resilience and adaptability. The discussion in the last section derives from manually coding the available material and the dispersed coaching imperative in social media (e.g. Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube) that I selected via theoretical sampling and in constant dialogue with the theory I employ, which grapples with the production of the self in "neoliberal culture" (e.g. Wilson 2017; McGuigan 2016; Skeggs 2004). To discuss the platformisation of the coaching persona, I further draw from micro-celebrity studies (Abidin 2018; Marwick 2015, 2018; Lewis & Christin 2020; Lewis 2020; Raun 2018) and platform studies (Nieborg and Poell 2018; Poell, Nieborg and Duffy 2021).

In the first part of this article, I explore the idea of the 'self' from a critical theory perspective, emphasising its different constructions in the context of neoliberal power and governmentality (Foucault 1978; Rose 1999; Skeggs 2004). In the following section, I look at the platformisation of the coaching figure and the coaching imperative. Platforms are socio-technical devices that not only spread a dazzling number of expert discourses about any matter possible, from wines to perfumes and films to socks, but also interpellate everyday users to develop micro-celebrity practices. The figure of the 'coach' and the coaching imperative are some of the archetypical figures that social media platforms disseminate. In the last section, I turn attention to this imperative, especially through the 'rags-to-riches' frame that I regard as a main talking point in the coaching industry. The coaching imperative represents a diffused technology in platform capitalism that often goes unnoticed as a result of its seemingly empowering tropes and injunctions (e.g., 'rags-to-riches', 'be confident', 'excellence' and 'self-understanding', among others).

The self, technologies, and techniques

The 'self' is a key terrain upon which power is exercised in capitalist modernity as well as a terrain of struggle where different discursive, legal, economic, and political strategies unfurl and often contradict one another. The concepts, usages, and expectations of the self are contingent on the structures, predispositions, and values of a social order as well as on the ways that different personality traits, gender, and class backgrounds, professional abilities, and other variables are enacted and evaluated in the framework of this order. The self is thus subject to interpellation by forces that happen 'outside of it', so to speak, which are often forces that, one way or another, attempt to shape and spin it in specific ways. In the context of capitalist modernity, one of the main institutions attempting to shape the self is liberal power, which, according to the classic Foucauldian critique, is positive in the sense that it wishes to model governable subjects instead of disciplining or crushing them (Rose 1999). The self is here shaped by different technologies, which are not only enforced by the state but endorsed by market forces, such as advertising and marketing.

Coaching relates to both ways that the concept of 'technology' was discussed by Michel Foucault at different stages of his career, that is, as a technology of power and as a technology of the self (Behrent 2013: 82). Coaching is a technology of power insofar as it refers to an institution with its own logic and predispositions that proposes shaping subjects of continuous self-improvement. It is also a technology of the self, a style of living that proposes ways and techniques for self-making, including constant introspection, analysis, and discipline to fulfil a vision. The technology of power denotes applications of power that are based on the "subtle manipulation of human behaviour", where "bodies are prodded in certain directions, moulded according to particular norms", while the technology of the self implies the "arts of existence" involved in the process of self-fashioning (Behrent 2013: 84). The coaching discourse is generative, in the sense that it makes it possible for human beings to evaluate themselves and speak about themselves in novel ways. As a technology of power, it exposes the population to questioning by a certain authority, such as the diet expert, the food expert, the self-image expert, the career expert, and so on. As a technology of the self, coaching primarily promotes a style of living that corresponds to resilient, confident, and adaptable leaders and promotes techniques to achieve these qualities. If religious ascesis expresses "a particular kind of self-fashioning or way of living" (Behrent 2013: 90), which implies renouncing the present for the sake of individual and collective salvation, then coaching discipline proposes a style of living that denounces present joy for the sake of a future advanced self. Via recourse to their own constructed expertise, the coaching authorities suggest the proper ways of conduct that regulate the conflicting and always negotiable borders between the normal and pathological. 'It is normal not to feel OK!', for instance asserts Castillo (2022), the owner of the Life Coach School, portraying negativity as normality (rather than pathology) in the larger struggle to achieve a better self. Castillo tells us to never quit, to never abandon the effort despite all obstacles, as quitting will jeopardise the coaching cause.

In terms of institutional heirs, life-coaching is a carryover of the legacy of self-help, which is a staple reference on matters pertaining to the self. Self-help is a spinoff of liberal political thought, emphasising individual excellence and the personal struggle each person should undertake in order to develop. The Scottish author Samuel Smiles, who published his book Self-Help in 1859 in England and is usually credited as the founder of the genre, comes from this political tradition, which he was evoking in the social and political affairs of this time. While Smiles can be seen as a populariser of the values of aristocracy among the working classes, at the same time, Smiles was against the aristocracy and more in favour of the bourgeois ethos of self-making (Morris 1981). The elevation of self-excellence to the main individual and social purpose privileges notions of success bound to paragons of self-development. In the context of the failed workers' revolutions of 1848 around Europe, Smiles's writings, according to RJ Morris, offered a moral compass to disenfranchised members of the working class who could focus on becoming better people and grow (Morris 1981). In this strivin g for self-excellence, the working class cannot help but lag behind the bourgeoisie, as the latter has more access to economic and cultural resources. In this sense, it is fairer to say that at least the foundations of self-help partake not of nobility but of the bourgeoisie, which results in pushing the working class to adopt a petite bourgeois mentality, that is, a life moulded after the mirror image of the bourgeoisie. This suggests an endless quest for self-improvement, which creates class anxieties for the lower strata.

In other words, the therapeutic entails a larger pedagogical-bourgeois mission, a self-education, so to speak, aiming to cultivate and emancipate the self from primitive impulsiveness. The idea of a 'superior self' that should oversee our barbaric instincts, emotional reactions, and harmful habits, which the coaching imperative suggests, draws from different techniques of the self in late capitalism. The construction of this superior self operationalises key subjective affordances of late modernity, which for Beverly Skeggs (2004) can be summarised in aesthetic self-fashioning, reflexiveness, and prosthesis. First, the 'aesthetic self', related to the thought of Michel Foucault (1984) and, later, of consumption theorists (e.g. Featherstone 2007), foregrounds an understanding of the self as an aesthetic project, a work of art that corresponds to the vision of its creator. The coaching imperative likewise often prompts people to imagine their lives in terms of stories and narratives embodying their unique visions. For instance, the instructors of the coaching course I attended, Joeel and Natalie Rivera, argue that "you are helping people to take control of their story...to have clarity of what they want and how they want it".1 Seeing life as an ongoing story implies constructing the self as an artwork in progress that can inhabit various styles and emotional tonalities, like the archetypical roaming modern figures of the bohemian or the dandy. Second, the coaching imperative rationalises the aesthetic self by summoning a 'reflexive self' (Adams 2003), which is a perspective developed by the so-called reflexivity theorists in the 1980s and 1990s (e.g. Anthony Giddens), to account for the emergence of a constantly updatable self in late modernity that is continuously forced to reflect upon its existence as a result of social insecurity, consumerism, and information overload. 'Monitor your thoughts' is a classic coaching imperative that amounts to the never-ending self-tracking that one needs to practise to grasp and potentially transform one's manners and behavioural patterns. In the context of life coaching, the trait of reflexivity points to a rational entrepreneur of the self and re-creates the aesthetic self as a semi-rational figure, a bohemian-bourgeois. And finally, the coaching imperative makes use of what Celia Lury calls the "prosthetic self" (1998), which is a self that is open to experimentation and adaptation of diverse prosthetic materials that can magnify its bodily and psychic capacities. For instance, it is common for men's coaches to advocate the use of dating apps that offer men the opportunity to choose from a larger pool of potential partners and therefore enlarge their potential. This technological self complements the two previous figures by harbouring adaptability to the new social environments and therefore resilience, which is a key concept of the therapeutic discourse (Illouz 2020).

The successful implementation of these techniques of the self, i.e. aestheticisation, reflexivity, and prosthesis, depends on access to cultural and economic resources (Skeggs 2004). The more opportunities for access one has, the more possibilities there are to progress in the race for self-realisation. To be able to go to a 10-day yoga retreat in India in order to 'find yourself', for instance, for a person living in Europe, demands time and resources that not everyone is able to afford. In other words, the successful implementation of the 'improved self' is conditioned upon power and class hierarchies; this perpetually hanging and unattainable improved self generates, in turn, social confusions and anxieties typical of neoliberal culture (Fisher 2009).

Inspirational Capital and Platforms

As mentioned above, the self-help and coaching narratives often rely on the authority of the coaches, who have to appear as paragons of successful individuals in their niche areas and set themselves as examples for others to follow. Thus, the actual life of the self-help and coaching guru should bear witness to what Eric Hendriks calls a "charismatic authority" (2017: 9). For Hendricks, apart from self-helpers and coaches, the principal role of charisma relates to other wannabe leaders including "prophets, saints, Buddhas, Indian gurus, magicians, political 'saviors', heroic military commanders, and certain intellectual or artistic geniuses, all of which are bearers of charisma" (2017: 4). The coach can make a "claim to charisma" (2017: 5), hoping that the followers will believe this claim and trust that the coach is indeed capable of resolving their problems.

The charismatic authority, in short, should inspire others. In this setting of make-believe, what we can call 'inspirational capital' is of vital significance for assembling the image of a thriving coach. Inspirational capital can be defined as the power and influence acquired over groups of followers, which can be traded as an economic asset. Inspiration, as a tool to raise publicity, is, of course, not only an asset among coaches but among various wannabe celebrities or micro-influencers, including politicians. From the 'Yes, We Can' of Obama to Trump's 'Make America Great Again', political leaders of all persuasions strive to inspire their audiences via empowering slogans and visions about the future. Yet, the drive to acquire inspirational capital reaches its apotheosis in the life coach, as it can be traded as a professional asset (see also the next section). By doing what they teach and preach, the coaches become aspiring 'truth-tellers' who set their lives as examples to inspire others. To gain legitimacy as a fitness coach, for instance, you need to have a fit body, or to be convincing as a 'self-image' coach, like Tonya Leigh from the School of Self-Image that we will see later, you need to radiate success, networks, and money. Among the coaches I followed, the performance of the self as a sort of truthteller that unites discourse and life was abundantly evident.

It is not only the coaching imperative but also the coaching persona that undergoes a process of platformisation (Nieborg and Poell 2018). Platforms can be defined "as data infrastructures that facilitate, aggregate, monetize, and govern interactions between end-users and content and service providers" and the platformisation of cultural production as the "penetration of digital platforms' economic, infrastructural, and governmental extensions into the cultural industries, as well as the organization of cultural practices of labor, creativity, and democracy around these platforms" (Poell, Nieborg and Duffy 2021: 5). In this sense, the coach should practise an inspirational authority on social media platforms in the form of posts, quotations, photos, videos, reels, and so on. With the enormous spread of visual-based social media, such as Instagram and Tik-Tok, the coach then has to curate an inspirational persona and engage in their own self-making as a micro-celebrity.

Unlike the pre-modern guru, who could perform a persona in physical proximity with their followers by making a speech at a gathering in a specific location, the modern coach has the ability to have a worldwide appeal owing to the internet. Media technologies are thus extensions that alter the authority's interaction with followers. An earlier device, such as the microphone, could magnify the authority's voice within a certain geographical area, while printing technologies offered the possibility to bypass proximity by carving this speech into a transferable object. Inventions such as audio recording, radio, television, and videotape further lifted spatiotemporal constraints. The social media platform offers the coach a potentially global audience for harvesting a persona that can grab the audience's attention in a potentially infinite market.

In other words, the coach should organise a business model in a theoretically global marketplace of supply and demand; modern life coaches can own multiple virtual spaces through which they can reach audiences, manage the production, distribution, and returns of the coaching business, as well as the overall aesthetics and design of these channels. Previously, in more gatekept conventional media, a coaching guru could have a short television slot in a morning programme or a one-page interview in a popular newspaper, and in both cases, the guru's performance would be subject to the editorial aims of the medium. On platforms, on the contrary, the guru possesses unlimited airtime in terms of temporal and spatial capacity for writing, speaking, and curating their identity. This occurs with a shift from representational to presentational media, as David Marshall describes it, that allows for a "widening dimension of the public self" (2010: 40), a self that is scattered across the digital environment, and who can be unceasingly interacting with audiences and followers. Conventional media's editorial role is to filter what is in the interest of the medium. Under the presentational regime, however, filtering is done by the (aspiring) public personas themselves (or with the help of separately hired social media managers), which means that they can share whatever content they want and fashion themselves the way they like. In other words, to raise publicity, the coaching personas can organise their own micro-celebrity practices.

The concept of micro-celebrity implies an online performance according to which the cultural producer cultivates themselves as a brand and interacts with followers and audiences through relational and emotional labour (Abidin 2018: 11). Micro-celebrity is a technique for constructing audiences as fans and crafting an inspiring persona for niche or broader social milieus. For AE Marwick, micro-celebrity is not an identity but "self-presentation strategy, a subject position [and] a labor practice altogether" (2018: 162). The micro-celebrity labour differs from the labour of the traditional celebrity as it is expected to practice bonds with the followers through performances of intimacy, authenticity, and accountability (Lewis 2020; Raun 2018). While the traditional celebrity is typically distant and unreachable, the micro-celebrity must be confessional, reciprocal, and engaged, i.e. "curate a persona that feels continuously authentic, interactive and celebrity-like regardless of the size or state of one's audience" (Abidin 2018: 12). Additionally, curation strategies are needed to combat the fear of legitimacy crises or cancellations that the social media landscape harvests and to instill trust in the followers (Lewis & Christin 2020; Lewis 2020; Raun 2018). As Hendricks comments:

Consequently, and despite all its rhetorical strengths, charismatic legitimacy is relatively unstable, since it is vulnerable to de-legitimizing crises. If information surfaces in public that contradicts the guru's self-presentation as a bearer of charisma, then many of the followers could quickly lose their faith and interest, throwing the guru's position as guru into crisis (2017: 8).

We should here add that any user with access to a computer and the internet may use similar micro-celebrity curation tactics on a platform in order to accrue symbolic and/or monetary capital. The promise is a flexible income stream and exciting opportunities instead of nine-to-five repetitiveness. In other words, platforms provide the means for encouraging individuals to develop and capitalise on their own curatorial-entrepreneurial skills, thereby expanding the scope of economic rationality to the entire population.

The Coaching Imperative

In turn, the coaching imperative is about the need to train oneself according to the vision of a future, superior self. As mentioned above, I regard the coaching imperative as a diffused articulation of platform capitalism that interpellates everyday users. The interpellation can occur when a user scrolls through their phones and stumbles upon posts, such as, for example, 'what you should do if sex in your relationship does not work', 'how to become confident in your career', 'how to understand good wine', 'how to make the perfect abs' and so on. This interpellation tells the user that they need training in order to accomplish these goals. The goals, in turn, are usually targeted at a particular 'problem' (career, love, sex, food, and so on), but are simultaneously as generic as possible so that they can grab the attention of anyone. The content of these goals can more or less cross everybody's mind living in consumer societies ('Why not have perfect abs?', someone can ask to themselves when seeing a similar post, 'People with perfect abs are healthy and enjoy social recognition'). This discourse targets the individual as a consumer, promising a superior self or simply a more developed well-being. I thus regard it as an exemplary form of vernacular neoliberalism, or what Jim McGuigan calls "demotic neoliberalism" (2016). Demotic neoliberalism is the quotidian and banal forms of neoliberal discourse that are, in our case, propagated by celebrities, influencers, or everyday users (Wilson 2018; McGuigan 2016). The coaching imperative is diffused across adjacent industries and articulations, involving mindfulness (Nehring, Frawley 2020), yoga retreats (Aydiner Juchat 2019) and healthy food diets (Otetero 2015), among countless others, that recommend training the soul and body in order to achieve certain ends. I should note that this is not a moral argument against these particular industries and activities that may otherwise be enjoyable and useful, but a systemic one, accounting for the intensification of self-centred ideological regimes in the context of platform capitalism.

Let us look, for instance, how the ideology of rags-to-riches plays out in the coaching industry, an ideology that, as is well known, is a classic discursive device in capitalist narratives of success. It is a rhetorical construction that legitimises the idea that 'anyone can make it to the top' regardless of class, gender, citizenship, ability, or ethnic background if they are determined enough. This ideology is part of a success story that works to spread similar talking points in the public discourse and, additionally, is a vehicle to legitimatise or even further professionalise the coaches themselves. For instance, while, say, a politician or actor may use a 'rags-to-riches' tale to boost their public image and intentionally or inadvertently create public discourse around it, for the life coach, the rags-to-riches stories can certify their professional identity and credibility. That is, the overcoming of a troubling experience in some area of life and the eventual inspiring transformation, can endow an aura of inspiration around the coaching persona. The rags-to-riches narratives in coaching are expanded, that is, they are not simply about the path from a lower to a higher class, but about any aspect possible; anything can count as 'rags', from being an alcoholic, depressed, jobless, and bully victim to living in a village, not having good grades at school, not knowing about perfumes, or being in a state of confusion.

The examples of likewise narratives in life coaching are countless, having to do with either specific traumatic events or general experiences of discomfort. Indicatively, in a podcast with Castillo titled 'Thriving After Break Up', Dorothy AB Johnson, a "Break-up Coach", explains that she decided to pursue the "break-up" specialisation after overcoming a traumatic break-up with a man she regarded as her future husband. Immediately after this event, as she puts it,

I was super upset, devastated, all of the things. I had pictured my whole life with him....So I was beside myself. I travelled, I meditated, I got in the best shape of my life. I did all the things, yet a year later, I was still feeling super angry and resentful (2022).

Attending the Life Coach School not only helped but gave Johnson the boost to become a break-up coach: "I wanted to show the world how to use the tools that I had learned through you and The Life Coach School into break-ups. And as I've done that, I've done this for three years now." (2022) Coaching was key to going through this dramatic event and even resulted in a metamorphosis that defined her pr ofessional identity: from devastation to regaining control. Or, in another episode of the same podcast, Tonya Leigh, who is a self-image coach, tells us that: "For so many years, I had spent my energy and my time trying to fix myself, fix my weight, fix my relationships, fix my bank account. And all that did was perpetuate the story that I was broken" (2022). Yet, after visiting Paris, Leigh "got a glimpse of the woman" she wanted to be (2022). This transformative event was key to training others to change their self-image as she overcame brokenness and headed towards self-actualisation.

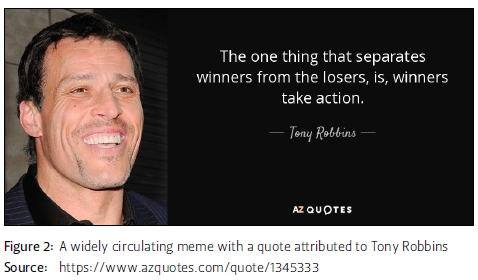

In the coaching narrative, the transformation from rags to riches happens if one strongly believes in it and if one is confident enough to pursue it: "You are the one in control; you are the one that you are going to make these changes" and "transformation is an inside job" say Joeel and Natalie Rivera from the Transformation Academy course I took.2 Simplicity, determination, and confidence are key. "Look at the simplest answers," proclaims Kain Ramsay.3"Have clarity of intentions, clarity of desire!", Joeel and Natalie Rivera continue. Fear, in turn, is a feeling for the weak: "Powerful people understand they have no choice but to try to succeed in life, because succumbing to fear only feeds disempowerment, stagnancy, and unfulfillment", says Ramsay (2020: 48). Likewise, inaction is for the losers: "The one thing that separates winners from the losers, is, winners take action", as the coaching superstar Tony Robbins is reportedly quoted in saying in a widely circulated internet meme (Picture 2). In all the above indicative narratives, the coaching imperative constructs a field of possibilities that exists independent of social inequalities and class divisions. The latter are beyond contestation or, more often, do not really have an impact on people's lives. The coaching imperative is thus an instance of market populism that distorts actual social conditions in favour of constructing an illusory image of a world full of opportunities and potentials.

Conclusions

This article looked at the figure of the life coach and the coaching imperative in the context of platformisation. As argued, the coaching imperative interpellates people in terms of their personal choices - that is, what food, clothes, career, and romantic partner they choose. The trainer of the Life Coach certificate course I undertook categorically argued in the first classes that life coaching is not about advice,4 in the sense that it is a tailored, feedback-driven and thus responsive practice that (at least in theory) avoids off-the-shelf counselling. It requires training the self, and this training cannot be the same for everyone. Following the general trend of customising consumption in contemporary societies, coaching here elevates the therapeutic from a general advice to an ongoing personalised quest.

Choice, then, in the coaching imperative, needs to have a vision that is unique and personal for each individual. This vision can be transformed in the course of one's life, entailing a process of constant revision and self-monitoring. Finding this vision requires labour and preoccupation with the self and its matters. The self here is a creative project, and the individual is its own meta artist-creator, who has, as if in a constant interview with themselves, to justify choices, life paths and relationships with others. Negativity in this context should be eliminated, packaged, or even better optimised so that it becomes presentable in social media, interviews, relations, and other platforms of self-presentation. "The neoliberal subject", as Byung-Chul Han puts it more dramatically, "is running around on the imperative of self-optimization, that is, on the compulsion always to achieve more and more" (2017: 36). As such, feelings and emotions are scrutinised and put on public display as never before in the public spheres of emotional capitalism, a sphere that, according to Illouz, is expanding instead of retreating in the age of social media (2007). Thoughts, affects, feelings, and emotions are a (post-industrial) material for an unprecedented labour and industry that aims to successfully orient the self towards paths of realisation, fulfillment, and happiness.

Disclaimer

This article is part of the EUMEPLAT project that has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No. 101004488. The information and views in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein.

References

Abidin C. 2018. Internet celebrity: understanding fame online. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1108/9781787560765 [ Links ]

Aboujaoude E. 2020. Where life coaching ends and therapy begins: toward a less confusing treatment landscape. Perspectives on Psychological Science 15(4): 973-977. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620904962 [ Links ]

Adams M. 2003. The reflexive self and culture: a critique. The British Journal of Sociology 54(2): 221-238. https://doi.org/10.1080/0007131032000080212 [ Links ]

Aydiner JP. 2019. Saluting the sun under the shadow of neoliberalism: an ethnographic study of yoga teacher training course attendees and yoga teachers. Master's thesis. Ankara: Middle East Technical University. [ Links ]

Behrent MC. 2013. Foucault and technology. History and Technology 29(1): 54-104. https://doi.org/10.1080/07341512.2013.780351 [ Links ]

Castillo B. 2022. When you just can't. Life School Podcast. Ep #405. Available at: https://thelifecoachschool.com/podcast/405/ [accessed June 11 2023. [ Links ]].

Featherstone M. 2007. Consumer culture and postmodernism. London: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446212424 [ Links ]

Fisher M. 2009. Capitalist realism: is there no alternative? Winchester: John Hunt Publishing. [ Links ]

Foucault M. 1984. What is enlightenment? In: Rabinow P (ed). The Foucault reader. New York: Pantheon Books. [ Links ]

Foucault M. 2008. The birth of biopolitics: lectures at the Collège de France, 1978-1979. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Foucault M. 2011. The courage of truth. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Han BC. 2017. Psychopolitics: neoliberalism and new technologies of power. London: Verso Books. [ Links ]

Health Coach Institute. 2023. Life Coaching Industry Trends of 2023. Available at: https://www.healthcoachinstitute.com/articles/life-coaching-industry-trends/ [accessed on 7 November 2023]. [ Links ]

Hendriks EC. 2017. Life advice from below: the public role of self-help coaches in Germany and China. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004319585 [ Links ]

Illouz E. 2007. Cold intimacies: the making of emotional capitalism. Cambridge: Polity. [ Links ]

Illouz E. 2008. Saving the modern soul: therapy, emotions, and the culture of self-help. Oakland: University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520941311 [ Links ]

Illouz E. 2020. Resilience: the failure of success. In: Nehring D, Madsen OJ, Cabanas E, Mills C, Kerrigan D (eds). The Routledge international handbook of global therapeutic cultures. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Johnson AB. 2022. Thriving after a breakup with Dorothy AB Johnson. Life School Podcast. Ep #404. Available at: https://thelifecoachschool.com/podcast/404/ [accessed June 11 2023. [ Links ]].

Leigh T. 2022. Your self image and money with Tonya Leigh. Life School Podcast. Ep #401. Available at: https://thelifecoachschool.com/podcast/401/ [Accessed June 11 2023. [ Links ]].

Levi M. 2023. Self-discipline with Monica Levi. Life School Podcast. Ep #458. Available at: https://thelifecoachschool.com/podcast/458/ [accessed June 11 2023. [ Links ]].

Lewis R and Christin A. 2022. Platform drama: "cancel culture", celebrity, and the struggle for accountability on YouTube. New Media & Society 24(7): 1632-1656. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221099235 [ Links ]

Lewis R. 2020. "This is what the news won't show you": YouTube creators and the reactionary politics of micro-celebrity. Television & New Media 21(2): 201-217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419879919 [ Links ]

LuRY C. 1998. Prosthetic culture: photography, memory and identity. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Marwick AE. 2018. The algorithmic celebrity. In: Abidin C, Brown ML (eds). Microcelebrity around the globe. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited. [ Links ]

McGuigan J. 2016. Neoliberal culture. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137466464 [ Links ]

Morris RJ. 1981. Samuel Smiles and the genesis of self-help; the retreat to a petit bourgeois utopia. The Historical Journal24(1): 89-109. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X00008049 [ Links ]

Nehring D and Frawley A. 2020. Mindfulness and the 'psychological imagination'. Sociology of Health & Illness 42(5): 1184-1201. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13093 [ Links ]

Nehring D, Madsen OJ, Cabanas E and Kerrigan D. 2020. Introduction: therapeutic global cultures from a multidisciplinary perspective: present and future challenges. In: Nehring D, Madsen OJ, Cabanas E, Mills C, Kerrigan D (eds). The Routledge international handbook of global therapeutic cultures. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429024764 [ Links ]

Nieborg DB and Poell T. 2018. The platformization of cultural production: theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New media & society 20(11): 4275-4292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818769694 [ Links ]

O'Reilly, K. 2008. Key concepts in ethnography. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Otero G, Pechlaner G, Liberman G.and Gürcan E. 2015. The neoliberal diet and inequality in the United States. Social Science & Medicine 142: 47-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.005 [ Links ]

Poell T, Nieborg DB and Duffy BE. 2021. Platforms and cultural production. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Ramsay K. 2020. Responsibility rebellion: an unconventional approach to personal empowerment. Houndstooth: Houndstooth Press. [ Links ]

Raun T. 2018. Capitalizing intimacy: new subcultural forms of micro-celebrity strategies and affective labour on YouTube. Convergence 24(1): 99-113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517736983 [ Links ]

Rose N. 1999. Powers of freedom: reframing political thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511488856 [ Links ]

Skeggs B. 2004. Exchange, value and affect: Bourdieu and 'the self'. The sociological review 52: 75-95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00525.x [ Links ]

Srnicek N. 2017. Platform capitalism. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Wilson J. 2017. Neoliberalism. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315623085 [ Links ]

First submission: 14 April 2023

Acceptance: 14 June 2023

Published: 6 December 2023

1 This is stated in the accredited course 'Transformation Life Coach Certification (Accredited) Life coach your clients to breakthrough, create lasting change, master transitions & be the hero of their life story'. Available at: https://www.udemy.com/course/transformation-life-coach-certification/

2 This is stated in the accredited course 'Transformation Life Coach Certification (Accredited) Life coach your clients to breakthrough, create lasting change, master transitions & be the hero of their life story' https://www.udemy.com/course/transformation-life-coach-certification/

3 This is stated in the first class of the course Life Coaching Certificate Course (Beginner to Intermediate): https://www.udemy.com/course/life-coaching-online-certification-course-life-coach-training/

4 This is stated in the first class of the course Life Coaching Certificate Course (Beginner to Intermediate): https://www.udemy.com/course/life-coaching-online-certification-course-life-coach-training/