Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Acta Academica

versión On-line ISSN 2415-0479

versión impresa ISSN 0587-2405

Acta acad. (Bloemfontein, Online) vol.55 no.1 Bloemfontein 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.38140/aa.v55i1.7484

ARTICLES

Does urbanisation change the political order in Africa? Reflections on cities, middle-classes and political processes in Kenya

Florian Stoll

Leipzig Research Centre Global Dynamics, Leipzig University, Leipzig. E-mail: florian.stoll@uni-leipzig.de; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9799-4061

ABSTRACT

Most African countries have seen a significant growth of cities in the last decades. Political systems rely, however, frequently on the networks of societies with a rural majority. This article uses the example of Kenya to illustrate how urbanisation influences political processes. Kenya is particularly suited to discuss this connection because it is a constitutional democracy with formally free elections, a multiparty system and political parties with an ethnic foundation. Parties do not rely on political-ideological programmes but are based, by and large, on mono-or multi-ethnic-regional affiliations. With growing migration into cities, the existing political balance could come under pressure as ethnic-regional affiliations weaken. This article examines if there are indicators for the change of the political order. Are there signs that the urban population stops accepting the distribution of resources and power to the political-economic elite and its rural basis? New urban middle-income groups (often called "middle-classes"), who are no longer embedded into regional ethnic networks, play a crucial role in the ongoing changes.

There is an analytical advantage to consider certain types of protest in the context of urbanisation and not only as outcomes of the political and societal sphere. Instead of studying isolated events and movements, this text suggests examining these in a long-term view and in the light of socio-structural change. Moreover, the argument assumes that there is a tension between the growing significance of cities and socio-political structures that build on rural society. Historical background information on Kenya and empirical examples of middle-income strata, protests, and activism demonstrate the impacts of urbanisation's increased significance for political processes.

Keywords: middle-class, Kenya, urbanisation, social movements, protest, cities

New urbanism and new urban "middle-classes" - what happens to political systems in Africa that rest on rural solidarities?1

Rapid urbanisation is one of the most important trends in contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa (UN Habitat 2022). However, it is an open question how the increasing significance of cities and urban life affects political processes. This text uses the example of Kenya to illustrate how urbanisation as a long-term process influences political processes. Consequently, this is not an article about changing voting patterns or the programmes of political parties. Rather, it takes urbanisation itself as a tendency that shakes existing patterns. The focus is orientations in life and the needs of the growing urban population. A considerable number of urban inhabitants may break with the established system of urban-rural ties that have characterised Kenya since colonial times. In this perspective, new urban "middle-classes" are a faction that is both result and agent of urbanisation. A part of my argument rests on the empirical work on the sociocultural heterogeneity of middle-income strata in urban Kenya, mainly in Nairobi (Neubert and Stoll 2015).

Kenya is a particularly suitable case to discuss the connection between urbanisation, middle-income strata, and changes in the political arena. The country is a constitutional democracy with formally free elections, a multi-party system and political parties with an ethnic foundation. The parties with a relevant share of voters do not rely on political-ideological programmes but are based, by and large, on mono- or multi-ethnic-regional affiliations. Political parties are to a high degree rooted in ethnic-regional divisions (Elischer 2013: 43-99) and correlating distribution systems that channel resources. In addition, Kenya has undergone urbanisation processes with a growing "middle-class" of whom many seem to have fewer ties to the countryside than previous generations. The demands of this urban-based population are out of the focus of long-established rural-ethnic parties and networks. The distribution of public goods is directed towards a society with a vast majority in the countryside (Maihack 2018). There is a structural tension between the distribution channels of public goods and the needs of the emerging number of city dwellers.

These developments make the country a good example to study how a new significance of cities clashes with a political system that was built to support a largely rural society. The population growth from Kenya's 8.6 million inhabitants on the verge of independence in 1963 to about 45 million in 2022 increases this dynamic of urbanisation. A fundamental question is, however, how the turn towards cities changes established societal and socio-political structures. What does the stronger urban rooting mean for individuals' expectations, ways of life and political processes? The following text examines tendencies how everyday life, the consciousness of middle-income strata and eruptions of political activities are today bound to the urban. Additionally, the article discusses some examples of how this friction informs political protest and alliances.

Kenya's party politics in transition from rural to urban constituencies

Sebastian Elischer (2013) reconstructs how ethnicity became the divisive line in Kenya's political arena. Elischer (2013: 43 ff.) wrote a book on political parties in Africa and took Kenya as a paradigmatic example for ethnicity as foundation. He contrasts Kenya to Namibia's mixed model with a "dominance of nonethnic parties" (Elischer 2013: 100) and Ghana's "ubiquity of nonethnic parties" (Elischer 2013: 100). According to Elischer (2013: 43) Kenyan parties are either mono-ethnic or multi-ethnic coalitions. In general, parties start as mono-ethnic entities. They try to get rid of the ethnic focus to become parties eligible on a national level, but they fail. Finally, they turn into multi-ethnic parties. The practical implications of ethnicity became shockingly visible in Kenya's post-election violence in 2007/08. After a close outcome in elections and multiple fraud accusations against the alleged winner Kibaki and opposition leader Odinga, the country was shaken by massive ethnically-based violence.

The structure of political parties is also significant because it can easily transport an image of a dualistic structure that divides networks into a few powerful individuals on top and a large number of followers on the ground. In this perception there seem to be few intermediary positions with agency. Authors such as Elischer offer a nuanced portrait of political parties but in developmental and other debates about Africa, we often see simplistic explanations.

In spite of its strong rural foundation, there have been towns and cities in Kenya for a long time. Since the early colonial period, it had been common, mostly for men, to work far from home (Spronk 2012: 50 ff.). However, their rural homes remained mostly emotional centres and places for investment. Solidarities to relatives in the home region and to communities continued to exist. For a long time, urban-rural ties in Africa were the subject of academic discussion (for example Gugler and Geschiere 1998). A specific characteristic for most African settings was that the ties to home villages were not severed but rather became more significant in the second half of the 20th century. Unlike modernisation theories had expected, cities did not integrate individuals to a similar extent into their life-worlds as their European or North American counterparts.

Geschiere and Gugler (1998: 310) developed a model for urban-rural relations in Africa, that still leaves space for local variations: the rural part offers a secure base for those in the cities. It is also a place where women and children can live and farm. Notwithstanding if all family members stay permanently in the city, they want to return to the rural area after retirement. The individuals in the urban are considered as bridgebuilders for those remaining in the villages. When villagers arrive in the city, inhabitants from their home regions are obliged to support them in multiple ways. From housing and financial help to contacts and job search to interaction with institutions like authorities or schools, the urbanites perform all kinds of help. In addition to these functional aspects, there are also normative elements such as value systems and cultural elements such as shared vernacular languages that contribute to keeping the relation up. The urban position can also build on their relation to other people from their rural home communities. This system had been established for the last decades of the 20th century in many parts of Africa. Until today, this model describes the realities of life for many Kenyans. However, it is no longer the undisputed way of life for the vast majority of Kenya's urban populations.

In the last decades, maybe with the year 2000 as a turning point, considerable changes redefined the urban-rural relations in Kenya and other African countries. The rapid growth of cities, a steep rise in population, and a new significance of the city as a place to live led to a new dimension of urbanism. In addition to the long-established urban-rural ties, a self-contained city life increased in importance. More and more individuals - from the poor in the slums to new middle-income strata to new groups among the rich - made cities the centres of their lives. Nairobi as the outstanding hub for business and education attracted Kenyan and foreign migrants for a long time. Other cities in the country grew as well but in specific ways with regards to local factors, national development policies, and the integration into global structures. Middle-sized cities such as Nakuru or Ruiru and smaller places benefited from their proximity to Nairobi. Mombasa attracted Kenyans from all parts of the country with opportunities in international tourism and jobs at the port because it is the country's access point to the sea. Kisumu experienced also growth but on a more modest scale as a local centre. Eldoret gained significance through political measures under president Moi's rule, for instance, by creating Kenya's second-largest university in the middle of a rural environment. Eldoret grew from 18 000 inhabitants in 1969 to 428 000 in 2022 mainly as the result of governmental development efforts (Macrotrends 2022). In contrast, the coast never had a significant share of governemental power. Mombasa received therefore during the last decades comparatively little infrastructure funding and until today, for example, does not have a public comprehensive university. The metropolitan area of Nairobi grew from 505 000 inhabitants in 1969 to 5 119 000 in 2022 (Macrotrends 2022).

Statistics about income are not very reliable but international organisations estimate that half of the city's inhabitants live below the poverty line (Oxfam 2009; UN-Habitat 2013). A realistic guess is that about one third of Nairobi's households fall into the middle-income stratum. There are different economic definitions for "middle-class"; for a discussion of some common approaches see Neubert and Stoll 2018. In addition to methodological questions, competing quantitative boundaries by daily expenditure for the middle-income stratum (Neubert and Stoll 2018) show difficulties in defining a middle bracket purely by financial means. Therefore, this text defines the "middle-class" as those individuals between the poor and rich.

What happens when more and more people permanently live in cities? And how do the needs of the frequently economically strong urbanites fit into the established model that originates from decades ago? Hendrick Maihack (2018: 3) sees urbanisation as a driver of change for Kenya's political system. Until today, Kenya's system of ethnic clientelism had prevented discussions about redistribution between rich and poor. Ethnic group identification and the organisation of political power along this line are very common ways to get access to resources such as jobs in the public administration or contracts for enterprises. Maihack concludes there is little motivation for a socially just distribution of public goods and high motivation for corruption in the existing socio-political system.

However, Maihack stresses the need for long-term change and new opportunities. The system of ethnic-clientelism collides with the need for public services in urban areas. The current distribution results in insufficient public goods for the economically strong "middle-classes" in Kenya's cities and the increasingly discontented slum dwellers. With the prognosis that half of the country's population will live in cities by 2050, Maihack sees alliances of democratic actors for redistribution of public goods as crucial for the future of the country. For Maihack (2018: 8 ff.), the rising number of protests since 2010 is an indicator that a more urban and socially diverse Kenya puts pressure on the existing clientelistic system.

Growing cities - towards a new urban consciousness?

Hendrick Maihack's (2018) analysis of a changing population is striking and the logic of his argument is consistent. However, his description of "the middle-class" remains vague as he does not offer a comprehensive picture of different factions in the middle-income stratum. And he stresses mainly possible outcomes of urban growth on political processes that might happen in the next decades. For example, his hopes for a more even distribution of public goods leave out other dynamics that may shape change. Among the uncertain factors are new sociopolitical coalitions and the influential reforms around "devolution", a revision of the constitution that had aimed at giving more power to local communities and counties. Moreover, the hope for reforms is a prognosis that is susceptible to new developments. Unexpected political alliances, economic crises, or technological innovations could interfere with the proposed rise of the urban as a political force. The next sections examine, therefore, some indicators of how urbanisation is changing or could change socio-political processes and structures. The first dimension examines expectations and distinctive types of socio-political consciousness of urbanites. This is the micro-level of everyday life. The second dimension looks at initiatives, types of participation, and protests. Expectations and types of socio-political consciousness in the first dimension reflect how individuals organise their lives and how they include their extended families and other networks of solidarity. This level does not study directly political commitment, but it examines orientations and structures that are the foundation for support of social protest or electoral preferences.

The population growth in cities and the rising significance of the urban has led to new ways of life. Many young Kenyans with educational degrees found well-paid positions as employees or entrepreneurs. These men and women are financially stable enough to live independently from their families in the city. Yet, in previous generations, most of them maintained close ties to their relatives and communities in the rural home regions. It is still a widespread way of life to stay connected and share one's income with the extended family and with the local and ethnic community. However, it is not the only possibility for city dwellers anymore. There are different degrees of how individuals stay connected to their home region. This is one of the developments in the background of the debate on "middle-classes" in Kenya and other African countries. The so-called middle-class is rather a middle-income stratum with similar financial possibilities. A "middle-class narrative" (Neubert and Stoll 2018) throws together social milieus with distinct basic orientations and ways of life. Dieter Neubert and the author (see also his article in this special issue) developed, in a collaborative project using the example of Nairobi, a model of six heterogenous milieus in the middle-income stratum (Neubert and Stoll 2015).2

• Members of the "Neo-Traditional" Milieu maintain close connections to their extended family, and rural and ethnic communities including financial contributions.

• "Social Climbers" focus strongly on their individual advancement and on the rise of their nuclear family by high saving rates and long working hours.

• Members of the "Stability-Oriented Pragmatic" milieu try to maintain their socioeconomic position and have a strong domestic focus with moderate consumption.

• For "Cosmopolitan-Liberals", pro-democratic values and opposition to clientelism are as important as their careers, which they often pursue in NGOs or international companies.

• Individuals in the "Christian Milieu" participate several times a week in activities of their church and focus on ambitious economic activities that are in line with their faith.

• "Young Professionals" are between 20 and 35 years old and work in well-paid jobs or study. They combine strong career ambitions with a hedonistic way of life.

While it is difficult to quantify the size of each milieu, their existence demonstrates that many inhabitants of Kenya's biggest city consider ties to communities in the countryside merely as one of several options and not as the main orientation of their lives. We found only one milieu in the middle-income stratum, the "Neo-Traditionals",3 who categorically and consistently maintained close ties to relatives and communities in the home area of their parents. In other milieus, the degree of the ties varied considerably. For instance, individuals in the milieu of the "Young Professionals" in Nairobi, well-educated and career-oriented women and men between 20 and 35 years, displayed regular strategies to distance themselves from the social and financial demands of their relatives. In this milieu are also many young people who were raised in Nairobi and other cities.

It is evident that we find on the micro-level of basic orientations a strong turn towards urban ways of life. The general orientations of the middle-income stratum vary but they demonstrate that ties to clientelistic networks remain optional or collide with their aims in life. This is a considerable difference to the model that Gugler and Geschiere (1998) considered as the standard of ongoing urban-rural ties. However, it remains unclear to which degree an everyday orientation on urban life is being translated into political action.

A rise of urban-based protest?

Most city dwellers have different needs than residents of rural areas. There are many reasons why the inhabitants of cities express their dissatisfaction, from rising costs of living to a lack of infrastructure and to corruption. However, it is a long way from dissatisfaction in everyday life to political mobilisation. The next section examines, accordingly, which drivers of urban discontent, types of self-organisations, and protests exist. There is a wide range of activities in Kenya that we can define as "urban"-based in contrast to those that are part of the established urban-rural ties. This is an analytical binary opposition that focuses on the effect and not on conscious intentions. For example, companies and business opportunities, universities, mega-churches and dance clubs are not by definition opposed to rural regions. Yet, these and other attractive venues are located in the city, in Kenya to a high degree in Nairobi. Strikes and protests by such different groups as university lecturers and taxi drivers concentrate in urban areas. For instance, protests by Uber drivers about low pay and bad working conditions in 2019 shook many cities. Mobilisation has changed in the last decade with the internet, social media, and permanent communication through smartphones. Posts on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram can reach some groups with more than a million individuals in Kenya's capital. Nairobi is also one of the main spots for non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in Africa. Even if the NGOs' objectives would not fall on any extreme of the urban-rural opposition, their mere stay in Nairobi strengthens the status of the city. The National Board of NGOs (2020: 3) enlists for the period of 2019/2020 11 624 registered organisations in Kenya of which 9 255 were active. For the same period, 1 143 NGOs reported conducting projects in Nairobi county, 397 in Kisumu, 343 in Nakuru and 342 in Kiambu (National board of NGOs 2020: 11 f.).

Many organisations do not seem to be connected to urban spaces, but they break with existing patterns and norms. Churches in cities, frequently Evangelical and Pentecostal communities, establish ties to other churches in North America, Nigeria, and other countries. Membership in such a congregation makes it possible to follow a more individual way of life than in the longer-existing churches that are frequently stratified by age, rank, and gender. A considerable number of the large and established Kenyan parishes are also tied to certain regions and ethnic groups. Being an active member of an urban church can be one of the few legitimate ways - in particular, for women - to distance oneself from family-related and clientelistic networks. Many of the new congregations are more focused on the individual spiritual and biographical needs of urbanites and offer programmes for personal development.

We encounter in cities a wide range of activism that happens outside of clientelistic networks. From the long-term perspective of human rights groups and neighbourhood initiatives to spontaneous expressions of anger, there are activities of varying intensity. Some groups have specific objectives such as the struggle for women's rights or the fight against corruption. In addition, there are events that lead to indignation in online campaigns or Twitter hashtags that become big. For instance, in 2014, three years before the worldwide MeToo-movement took off, there was a public outcry about an attack by several men in Nairobi on a woman in a mini-skirt. These men forced the woman to get undressed because they considered her dress to be inappropriate. This event was one of the frequent examples of the abuse of women in public and it was also filmed by bystanders. The reaction to the video of the attack was protests on the streets and discussions in the public sphere. Debates on social media like Facebook and on Twitter skyrocketed under hashtags such as #MyDressMyChoice. More than an arbitrary event, the incident stood for many situations where morally conservative positions collided with the individual freedom of women in the metropole. The uprising against the violence of men who try to enact control over women illustrates a clash of different worldviews. It was an attack on the possible freedom of women to lead an independent life in the city.

Another example of a recent protest is the massive public embarrassment over the political decision to build a railway track from Nairobi to Mombasa in 2018. The Kenyan government planned to finance this huge project with credit from Chinese debtors. The Kenyan public did not see any reason to build the railway track for an estimated cost of US$ 4.7 billion (Mureithi 2022). The indignation about the plan was particularly strong because the cabinet refused to publish the contract with the Chinese construction company. Likewise, it was evident that the whole enterprise relied on a loss-producing business model. Especially the urban population felt threatened by the thought of dependence on China and the high costs of the credit. By spending so much on a railway track, there was a widespread concern that there could be even less investment into urgently needed infrastructure and public goods in the growing cities.

Examples for protest in Kenya

Example 1: Protest against MPs housing allowance and remunerations in 2019

An outstanding case of how urbanites in Nairobi and other cities protested against the established order is the struggle against the increase in the Members of Parliaments' (MPs) remunerations and the introduction of a housing allowance in 2019. Members of Parliament in Kenya have one the highest incomes in absolute numbers worldwide. They received in 2019 at least 1 378 000 Kenyan Shillings (then about 11 000 euros) per month plus additional benefits (Awich 2019).

In 2019, the MPs decided to introduce for themselves a monthly housing allowance for Nairobi of 250 000 Kenyan Shillings (about 2 000 euros) per month. This support for an apartment or other accommodation was several times the average earning of a Kenyan citizen. The allowance alone would have put MPs in the highest decile of income earners in Nairobi. Generations of Kenyan parliamentarians lived well through decades of Nairobi-based parliamentarism. Therefore, the wider public showed little understanding for an additional payment.

There was an outcry in print papers, social media, and other sources that lead to public debates and demonstrations on the streets. Luke Awich, in the weekly newspaper The Star, said that Kenya's MPs were even before the introduction of the housing allowance only second to Nigeria's MPs in absolute size of payment and ahead of Europe's and North America's representatives (Awich 2019). Headlines such as "Outrage over MPs insatiable appetite for cash" (The Standard, 6 May 2019) and "MPs wrong in bid to get taxpayer foot bill for their lavish lifestyles" (The Standard, 19 May 2019) in Kenya's big daily The Standard left no doubts about the journalists' opinions. Kenya's other big current newspaper, Daily Nation, on its front page said that MPs are now entitled to 17 different allowances (Daily Nation, 9 July 2019).

Growing pressure resulted in an official statement from the parliament about the compensation and allowances of MPs to "REMUNERATIONS OF MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT - DEMYSTIFYING THE FACTS" (Parliamentary Service Commission, 11 July 2019; emphasis i. O.). There were protests online and on the streets of Nairobi. Social media activism and an organised initiative demanded that the increased remunerations and the housing allowance be revoked. In December 2020 the Kenyan High Court decided that the MPs were not entitled to this financial benefit and in December 2021 the judges confirmed their verdict: "MPs to lose Sh2.7b over illegal house allowance" (Muthoni 2021). The MPs have to pay back the allowances they had already collected.

The 2019 protests stood in a long tradition of MPs trying to increase their remunerations and allowances followed by pushbacks by legal institutions and civil society. For instance, there was a similar debate on the increase in MPs remunerations in 2012 (BBC News 2012). This shows a trend in which the urban gains new significance. Many individuals from the middle-income stratum were involved in these protests. However, Kenyans in high and low socioeconomic positions participated as well. The shift towards the urban is gradual rather than happening in clearly separated steps. A look at an activist's profile may shed some light on the rise of activism in Nairobi and other urban centres.

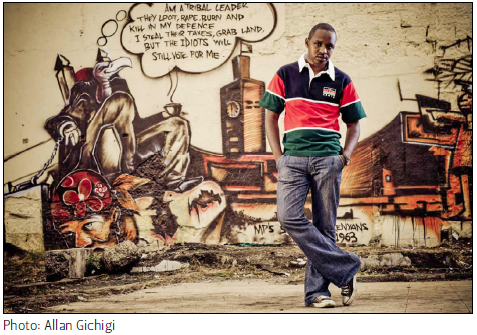

Example 2: Stations of activist Boniface Mwangi's political biography

Boniface Mwangi is a prominent figure in the Kenyan public arena whose example illustrates typical characteristics of contemporary urban activists. Mwangi's biography carries traces of political events that had a strong impact on his whole generation. Also, his case shows opportunities and obstacles for programmatic politics in Kenya that differ from the established clientelistic patterns. Mwangi began his career as a photographer and documented the unique extent of postelection violence in 2007/08.4 Kenya's elections in December 2007 were chaotic and characterised by suspicions of fraud by both the officially declared winner Kibaki and his opponent Raila Odinga. Even the head of the election committee admitted later he did not know who the winner was although he had formally called Kibaki the new president previously (Berger 2008). The uncertain situation led in late December 2007 and January 2008 to ethnically targeted violence and forced evictions on an unprecedented scale. As a consequence, several hundred thousand Kenyans were displaced and more than 1 000 were killed.

Boniface Mwangi documented the violence on the streets in photos and became in the following years more of an activist than a journalist. He organised a travelling exhibition with pictures of the atrocities and spoke at public events. In an interview, Mwangi explained stages of his political biography as reactions to his experiences (all quotes Eng, 27 February 2015). At the time of the elections in December 2007, he worked as a photographer for The Standard. When the violence after the chaotic voting and counting episode broke out, Mwangi was there and took pictures. He sees "a lot of terrible tribal rhetoric" in the mobilisation for the election. The uncompromising stances of alleged winner Kibaki and loser Odinga were another factor in his politicisation. Mwangi also mentions the consequences for the 500 000 displaced individuals who often ended up in a new ethnic community with a different language and ways of life: "How can you go back to a community where your neighbours tried to kill or rape you or your family?" Mwangi says he ended his job as a photographer after he had to take pictures of Kibaki and Odinga with then UN secretary Kofi Annan as mediator:

What disturbed me is that I had just come from the midst of the violence and watching the atrocities. It wasn't just stories I'd heard - I was a witness to the killings. And then I was assigned to go and cover the same politicians doing this. [...] They moved on and forgot the victims. They forgot that the country went to war because of them.

Frustrated and angry, Mwangi turned towards activism. He organised various activities that received much attention from the Kenyan public. On June 1, 2009, Mwangi interrupted a public live broadcast of President Kibaki in a full stadium. Over the next years, he and a growing group of other activists performed actions with a wide range of media attention. He was one of the founders of the Ukweli party that started as media guerrilla initiative and was transformed over time to a serious programmatic party as the website confirms: "Ukweli Party is a social-democratic national political organisation" (Ukweli Party 2022). In May 2019 Mwangi was arrested for planning a revolution. There were other events such as the bizarre arrest of Mwangi in a barbershop that he owned. Uniformed policemen entered the store but they could not present an ID card or a badge to prove their identity (Police defend officers in video drama with Boniface Mwangi 2021).

Mwangi is one of the most present individuals in Kenya's media opposing the clientelistic system. He became active in public debates due to a personal shock about the post-election violence and indignation about the injustice of the existing order. The critique of "tribalism" and greedy politicians implies a massive disappointment in the deficient public service for the majority of the population, especially in urban areas. The poor in Nairobi's slums live under harsh conditions. There is no reliable public transport and basic services from health to education to sanitation lack funding. Even middle-income Nairobians struggle to fulfill the expectations of their families with private schooling for kids, costly housing, and demands from needy relatives in the countryside.

Mwangi stands for many Kenyans who live in cities and are tired of the repercussions of ethnic clientelism and corruption. From tribalistic violence to access to public goods to political freedom, there are many reasons for their dissatisfaction. Mwangi is a public figure but he is also typical of many young and middle-aged Nairobians. Admittedly, few other individuals in Kenya's capital are as consequent in their decisions and have as many possibilities as the well-connected photographer and journalist. Yet, many share his discontent about public mismanagement, corruption, and ethnic divisions.

Many young Kenyans have been moving to Nairobi in the last decades and face a variety of options about how to live their lives. There is also an increasing number of Nairobi-born and -raised individuals who have only weak ties to rural communities. This younger generation in Nairobi and other cities benefits to a lesser degree from the patron-client relations that support mainly specific rural areas and their well-paid representatives in parliament. While it is difficult to quantify, these urban-based individuals could become the foundation for a programmatic outlook such as Mwangi's Ukweli Party. The demands of young city dwellers clash with the existing legal, social and political structures. It is uncertain how the upcoming conflicts will play out. Many individuals in Nairobi and other cities still feel obliged to show solidarity with their extended family and rural communities.

Conclusion

The ongoing trend towards urbanisation creates populations with a strong outlook on the city as the centre of their lives. A new generation of city dwellers differs by its focus on urban contexts from the previous generations. This development is a rupture with previous urban-rural ties in Kenya in which the relations to home regions remained very significant for almost all migrants to cities. Kenya had looked in the late 20th century like a textbook example of Geschiere's and Gugler's (1998: 310) model of urban-rural relations in Africa. Migrants from rural areas keep contact with their extended family and other networks in the countryside. Temporary work migrants in cities often rely on the assistance of these networks. They invest their income from urban jobs in farms and companies in their home areas, support relatives in distant regions financially, and participate in clientelistic networks.

This classical model of urban-rural-ties did not vanish, but other ways of life have gained significance in the last two decades. A closer look at the middle-income stratum offers crucial insights. Through the example of Nairobi, we have seen that heterogeneous "middle-class" milieus have different outlooks on life (Neubert and Stoll 2015). Connections to ethnic-regional networks remain in most middle-income milieus optional or stand in conflict with the milieus' orientations in life. The question remains how this shift in everyday urbanism is going to be translated into political action.

In addition to changing ways of life, there is also a considerable number of protests, social movements, and initiatives with a specific urban background. They are not part of established networks and follow their own interests. These groups are at least structurally opposed to the system of representation and distribution that took shape in the middle of the 20th century and that favoured regional development and the power of politicians. Analytically, it is not only political initiatives and social movements that strengthen the urban position but also the growing socioeconomic importance and the changing orientation towards the city in everyday lives. From business opportunities to education to churches to urban ways of life, a lot of factors contributed to the rise of the urban. The connection of different phenomena is changing the needs of city dwellers. Mismanagement of public goods, lack of basic infrastructure, and rage against widespread corruption are drivers of potential political change. The argument of this contribution is that a study of certain protests, including some "middle-class"-activism, brings analytical advantages if we consider these in the light of ongoing urbanisation and not just as discontents of certain individuals or groups. Initiatives such as the outcry against the raise of the MPs remunerations, gender-related protest like #MyDressMyChoice, and the anger about Chinese credit for the railway from Nairobi to Mombasa, demonstrate a high sensitivity to political processes. Does this increasing number indicate a new quality of protests, a change in political processes, and even a crisis in the existing political system?

The first draft of this article was written before the presidential vote in 2022. Yet, the campaigning strategies of the winner Ruto and the electoral behaviour offer insights into relevant changes. While in most areas of the country the established ethnic voting patterns prevailed, there were divergences in some regions. Ruto's main promise did not address certain ethnic groups but the whole population, mainly "hustlers" in low and middle positions (Mueller 2022). He built on the harsh conditions of childhood and created the narrative of a hardworking social climber who wants to support now other hardworking individuals. This pro-poor and anti-establishment position was directed against his competitor Raila Odinga. It was easy for Ruto to present himself as "hustler" against "dynasties" because Odinga had the support of then-president Uhuru Kenyatta. Odinga and Kenyatta are from two of Kenya's most powerful and richest political families. Moreover, Ruto promised relief programmes for the low-income population, the reduction of public debt and a review of the formula for sharing resources between the central government and regional constituencies. These measures are directed toward larger proportions of the population and not just limited groups. A considerable number of Kikuyu, Kenya's largest ethnic community, voted against the recommendation of president Kenyatta and preferred Ruto over Odinga. There was considerable mistrust among Kikuyu voters against Odinga due to old ethnic rivalries, doubt over his economic competence and an earlier promise by president Kenyatta in 2013. Kenyatta had pleaded to his then-deputy Ruto to support him in a later election. These and other reasons made a good number of Kikuyu voters act against the recommendation of Kikuyu president Kenyatta. This voting behaviour does not mark the end of ethnic solidarities, but it shows the gradual rise of programmatic interests. The home regions of the Kikuyu in central Kenya are close to Nairobi and members of this ethnic group are on average economically better off than most Kenyans. Similarly, a tendency towards urbanisation and individualisation made especially young and middle-income voters torn between programmatic, partly liberal interests and ethnic solidarity. Dominic Burbidge documented the different motives in a study about middle-income Kikuyu and their probable voting decisions in the weeks before the 2013 election (Burbidge 2014). In a tight presidential race, minor shifts can decide on victory or defeat. It is uncertain how the demands of urban dwellers in general and of "middle-classes" / middle-income milieus, in particular, will play out in the short and long run. There is a high probability that the increasing significance of the urban groups will lead to protests, new solidarities and changes in the programmes and campaigning strategies of political parties. Apart from the heterogeneous ways of life, it remains unclear which factions and individuals in the middle-income stratum depend to which degree on clientelistic rural networks. For some urbanites, there are other institutions such as religious communities that can offer alternative occupational and private networks. But it remains unclear who of the new "middle-class" acts with a high level of independence from political and ethnic communities. The 2022 elections offer a glimpse that the impact of urbanisation on Kenyan politics is already showing its first effects.

References

AwiCH L. 2019. New house allowance puts MPs' salary way above world super powers. The Star. 11 May. Available at: https://www.the-star.co.ke/siasa/2019-05-11-new-house-allowance-puts-mps-salary-way-above-world-super-powers/ [accessed on 4 February 2022]. [ Links ]

Baumann B and Bültmann D (eds). 2020. Social ontology, sociocultures and inequality in the global south. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, New York, NY: Routledge (Routledge studies in emerging societies). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367816810 [ Links ]

BBC News. 2012. Kenyan MPs' bonus: protesters march to parliament. BBC News. 9 October. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-19885962 [accessed on 4 February 2022]. [ Links ]

Bekker S and Fourchard L (eds). 2013. Governing cities in Africa. Politics and policies. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

Berger S. 2008. Kenya's poll chief does not know if Kibaki won. The Telegraph. 3 January. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/1574462/Kenyas-poll-chief-does-not-know-if-Kibaki-won.html [accessed on 4 February 2022]. [ Links ]

BuRBiDGE D. 2014. 'Can someone get me outta this middle class zone?!' Pressures on middle class Kikuyu in Kenya's 2013 election. Journal of Modern African Studies 52: 205-225. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X14000056 [ Links ]

EuscHER S. 2013. Political parties in Africa. Ethnicity and party formation. New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139519755 [ Links ]

Eng KF. 2015. TED Fellow Boniface Mwangi: risking my life for justice in Kenya. TED Blog. 27 February. Available at: https://blog.ted.com/ted-fellow-boniface-mwangi-on-risking-his-life-for-justice-in-kenya/ [accessed on 4 February 2022]. [ Links ]

Geschiere P and Gugler J. 1998. Introduction: the urban-rural connection: changing issues of belonging and identification. Africa 68(3): 309-319. https://doi.org/10.2307/1161251 [ Links ]

Kirk-Greene A and Bach D (eds). 1995. State and society in francophone Africa since independence. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-23826-2 [ Links ]

Kroeker L, O'Kane D and Scharrer T (eds). 2018. Middle classes in Africa. Changing lives and conceptual challenges. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan (Frontiers of globalization). Available at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/kxp/detail.action?docID=5303140. [ Links ]

Macrotrends. 2022. Available at: https://www.macrotrends.net/cities/21711/nairobi/population) [accessed on 31 January 2022]. [ Links ]

Maihack H. 2018. Corruption is a symptom. How urbanisation and social differentiation are changing Kenya. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Berlin. [ Links ]

Melber H (ed). 2016. The rise of Africa's middle class. Myths, realities and critical engagements. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. London: Zed Books (Africa now). https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350251168 [ Links ]

Mueller SD. 24 August 2022. Why did Kenyans elect Ruto as President? What looks superficially like a normal election was filled with contradictions, intrigue, double-crossing and surprise shifts in ethnic loyalties. Washington Post. 11 May. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/08/24/kenya-elections-kenyatta-ruto-odinga/ [accessed on 12 January 2023]. [ Links ]

MuREiTHi C. 2022. A state secret. Kenya is refusing to release the loan contracts for its Chinese-built railway. Available at: https://qz.com/africa/2115070/kenya-refuses-to-release-contracts-for-china-debt/ [accessed on 30 January 2022]. [ Links ]

Muthoni K. 2021. MPs to lose Sh2.7b over illegal house allowance. The Standard Group PLC. 12 June. Available online at https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/national/article/ [accessed on 4 February 2022]. [ Links ]

Neubert D and Stoll F. 2015. Socio-cultural diversity of the African middle class. The case of urban Kenya. Bayreuth African Studies Working Papers 14. Bayreuth: University of Bayreuth. [ Links ]

Neubert D and Stoll F. 2018. The narrative of 'the African middle class' and its conceptual limitations. In: Kroeker L, O'Kane D and Sharrer T (eds). Middle classes in Africa: changing lives and conceptual challenges. Palgrave MacMillan Cham: Camden. Non-Governmental Organisations Co-ordination Board. 2020. Annual. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62148-7_3 [ Links ]

NGO Sector Report. Year 2019/2020. Available at: bit.ly/43Myavf [accessed on 18 January 2022]. [ Links ]

Parliamentary Service Commission: 12th Parliament Press Statement. 11 July 2019. Available at: bit.ly/43x7vCf [accessed on 30 January 2022]. [ Links ]

Spronk R. 2012. Ambiguous pleasures. Sexuality and middle class self-perceptions in Nairobi. New York, NY: Berghahn Books. [ Links ]

Police defend officers in video drama with Boniface Mwangi. 2021. The Star. 9 October. Available at: https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2021-10-09-police-defend-officers-in-video-drama-with-boniface-mwangi/ [accessed on 4 February 2022]. [ Links ]

Statista. 2022. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1223543/urbanization-rate-in-africa-by-country/ [accessed on 31 January 2022]. [ Links ]

Ukweli Party. 2022. Ukweli Party - Nguvu Kwa Mwananchi. Available at: https://ukweliparty.org/about.html, updated on 11.10.2021 [accessed on 4 February 2022]. [ Links ]

UN Habitat. 2022. Africa Urban Agenda Programme. UN-Habitat. Available at: https://unhabitat.org/africa-urban-agenda-programme, updated on 1.6.2022 [accessed on 6 January 2022]. [ Links ]

First submission: 10 April 2022

Acceptance: 3 April 2023

Published: 31 July 2023

1 This article was written during a senior Fellowship at the Merian Institute for Advanced African Studies (MIASA) in Accra from April to August 2021. I'm very thankful for the opportunity to develop the idea of this article and discuss some of the arguments there. I also want to thank the photographer Allan Gichigi for the permission to print the picture of Boniface Mwangi.

2 These six milieus are just the main factions in the middle-income stratum. For example, there are smaller subgroups such as Muslim or Hindu factions with specific ways of life that can be subject for future research. Certain milieus overlap to some degree because there are individuals who show characteristics of two or more milieus. Transition ranges are the case with most social models that conceptualise social reality.

3 We called members of this community Neo-Traditionalbecause they refer to traditions but these traditions are frequently not very old.

4 The elections in December 2007 resulted in a narrow and disputed win of Mwai Kibaki's KANU over Raila Odinga's ODM. The contested results lead to violent protests and ethnically motivated killings. The unprecedented dimension was a shock to the Kenyan and international public. There were, however, little legal consequences for the instigators of this violence.