Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Acta Academica

versão On-line ISSN 2415-0479

versão impressa ISSN 0587-2405

Acta acad. (Bloemfontein, Online) vol.54 no.2 Bloemfontein 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150479/aa54i2/7

ARTICLES

"A river with many branches": song as a response to Afrophobic sentiments and violence in South Africa

Martina Viljoen

Odeion School of Music, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. E-mail: viljoenm@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this article is to examine the symbolic role of song regarding Afrophobia in South Africa -a topic which has received limited attention within local music scholarship. To this aim, a textual reading, drawing on thematic analysis serves to identify patterns of cultural meaning represented in "Umshini wami", as opposed to anti-Afrophobic songs, including Boom Shaka's "Kwere Kwere" (1993); "Xenophobia" by Maskandi musician Mthandeni (2015), "United we Stand, Divided, we Fall" by Ladysmith Black Mambazo with Malian singer Salif Keita (2015), and "Sinjengomfula" on the CD Tjoon in (2008), a collective production by musicians from Mozambique, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. The question considered is how healing metaphors featured in these songs oppose a politics of fear and the idea of the other as enemy in "Umshini wami", described in the media as the 'soundtrack' of the deadly Afrophobic upsurge of 2008. It is found that, within the context of Afrophobia, the symbolic reach of "Umshini wami" extends beyond inter-racial conflict and in-group black factionalism to convey a politics of 'war' on African foreign nationals. Contrastingly, as symbolic exemplifications, healing metaphors in the selection of anti-xenophobic songs discussed speak to a perceived unified identity that, while representing ethnically diverse peoples, may bind Africans together through the fundamental human rights of morality, justice, and dignity.

Keywords: xenophobia, Afrophobia, South Africa, anti-Afrophobic songs, reconciliation

Introduction

With the exception of the work of Ballantine (2015), Bethke (2017) and Phakati (2019), who have approached the phenomenon of xenophobia from diverse angles, the topic has not yet received wider attention within South African music scholarship. Offering a self-reflexive reading of his Chamber Eucharist, written in October 2015 as a musical response to the xenophobic violence that flared up in the preceding months of that year, Bethke (2017: 27) advocates different musical cultures from Africa co-existing and complementing one another. Accordingly, his liturgical composition embodies numerous African musical styles, represented through multilingualism and multiculturalism. Contrastingly, Phakati's (2019) reading of Maskandi musician Mthandeni's popular song "Xenophobia", while considering the relation of religion, governance, and universal humanity to xenophobic violence, culminates in a plea to the South African government to consciously educate South African citizens about Pan-Africanism. Ballantine (2015: 501ff.), on the other hand, establishes a theoretical basis for the argument that, within the South African context, music can play a social role of immense importance to counter inequality, violent xenophobia, racism, ethnic prejudice, fundamentalism, religious hatred, and other deeply engrained habits of othering.

With the aim of contributing to the broader discourse on music as diplomacy, the purpose here is to examine the symbolic role of music regarding Afrophobia in South Africa. To this aim, a textual reading of a selection of songs is offered, drawing on thematic analysis. This approach first serves to identify themes represented in "Umshini wami" and then to reflect on three anti-Afrophobic songs, Boom Shaka's "Kwere Kwere" (1993); "Xenophobia" by Maskandi musician Mthandeni (2015), and "United we Stand, Divided, we Fall" by Ladysmith Black Mambazo with Malian singer Salif Keita (2015). Finally, the song "Sinjengomfula" on the CD Tjoon in (2008), a collective production by musicians from Mozambique, South Africa, and Zimbabwe, is briefly discussed.

The question considered in this article is how healing metaphors featured in these anti-Afrophobic songs oppose a politics of fear and the idea of the other as enemy in "Umshini wami" and other local ethno- and xenophobic songs alluded to as part of the argument. The songs reflected on in this article were chosen on the grounds of having featured in the media due to political controversy, or for actively opposing local manifestations of ethno- and xenophobia.

Concerning the method used, Mills, Durepos and Wiebe (2010: 926) define thematic analysis as a systematic approach to the analysis of qualitative data that involve the identification of themes or patterns of cultural meaning; the coding of such data according to the themes identified; and interpreting the resulting thematic structures by seeking out overarching patterns of meaning, theoretical constructs, or explanatory principles. As a first step of the process, coding involves the assignment of labels to important concepts within the set of data considered, which allows the researcher to derive the themes and patterns. Historically, researchers have applied thematic analysis mainly to textual data -as is the case here.

The identification of themes relevant to my analysis is concept driven (see Gibbs 2007: 44-45). As such, they are derived inductively from the lyrics of the songs to be discussed, scholarly literature on the topic of Afrophobia, and media reportage. However, themes considered are not merely descriptive, but instead lend themselves towards theoretical and analytical contextualisation (see Gibbs 2007: 54). Thus, they are identified deductively as well, relying on concepts that emerge as part of the theoretical/philosophical framing of my study. The combination of an inductive and deductive approach has an enriching function, as the inclusion of inductive thematic analysis eludes the premature closure that may characterise a deductive approach (Mills et al. 2010:926ff.). It does so exactly by being open to different sets of data, which all contribute towards a comprehensive explication of the phenomenon, and thus the question to be studied.

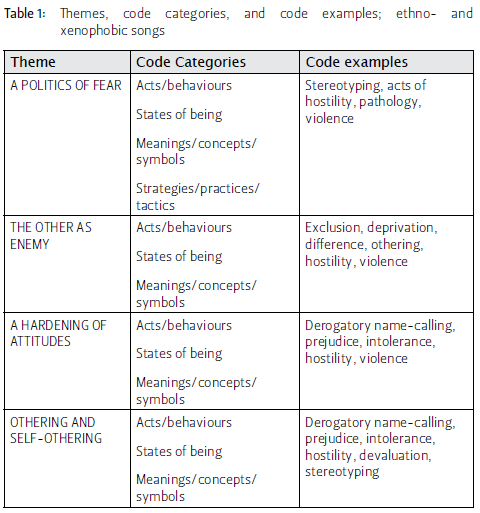

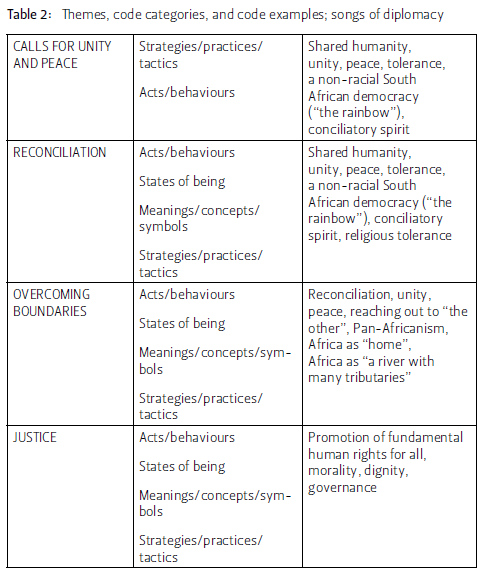

Concerning a theoretical framing for examining the songs to be discussed, and for establishing a framework of thematic ideas (see Gibbs 2007: 38), themes introduced include the idea of a politics of fear (Verryn 2008: viii-ix; Solomon and Kosaka 2013: 6); the notion of the other as enemy (Singh and Francis 2010: 304305); a hardening of culturally biased dispositions (contradicting former utopian notions of the so-called 'rainbow nation'; see Adam and Moodley 2015: 1; Van der Waal and Robins 2011: 763), and related ideas of othering and self-othering (Vanderhaegen 2014: 31). Terms such as exclusion, deprivation, difference, otherness, stereotyping, hostility, pathology, and violence will consequently be juxtaposed with healing metaphors featured in the songs analysed. These highlight terms such as universal humanity, unity, peace, tolerance, a non-racial South African democracy ('the rainbow'); a conciliatory spirit, reaching out to 'the other'; the promotion of fundamental human rights for all; morality; dignity, and governance. As an overarching theme, the idea of Pan-Africanism is also highlighted.

Below, themes, code categories, and code examples relevant to my analyses are tabled. Gibbs (2007: 47-48) explains that code categories situate codes within specific social situations - as is evident in Tables 1 and 2. As already indicated, code examples are derived from the song texts considered in this article - and from their broader context as established through literature study and a study of media reportage.

Political songs endorsing ethno- and Afrophobia

As representations of a collective psyche, media coverage confirms that political songs endorsing ethno- and xenophobia have become an notorious part of South African society's complex socio-political fabric. Within the context of black resistance, a notable example is the struggle song "Dubul'ibhunu" (Shoot the boer), initially sung by Peter Mokaba in 1993 at the memorial service of Chris Hani (Brkic 2010). Economic Freedom Front leader Julius Malema later lent the song iconic status as actioned hate speech, its words repeating the phrases "Ayesab' amagwala" (Cowards are frightened)/"Dubula Dubula" (Shoot shoot)/"Dubula ngesibamu" (Shoot with the gun)/"Dubul' ibhunu" (Shoot the boer) (Gunner 2015: 333). During 2010, the South African High Court ruled that "Shoot the boer" was likely to incite violence against South Africa's white minority, and Malema was banned from singing the song. As a mythical representation of the postapartheid state, it is accepted that the song forms part of struggle memory, and thus of the history of this country (Gunner 2015: 333).1 Yet, during a recent court case between Malema and Afri-Forum, heard in the Equality Court of the Southern Gauteng High Court in Johannesburg, Malema refused under cross-examination to condemn the idea of white genocide and not to commit it. This clearly indicated that, from this perspective, his singing of "Shoot the Boer" could reasonably be construed to be harmful, or even could incite ethnic violence (Hayward 2022).

An equally controversial song, "Umshini wami", also known as "Awuleth' Umshini Wami", sung by members of Umkhonto we Sizwe during the apartheid struggle in South Africa, is of particular significance regarding the topic of this article. According to the media reportage (Mbanjwa 2008), the song, which has come to be associated with the persona of former President Jacob Zuma, was sung repeatedly during the 2008 xenophobic attacks in South Africa. With 'machine' allegedly referring to a machine gun, in the politically volatile context it was (and is) sung, the lyrics of the song are experienced as being direct and confrontational (Gunner 2009: 27ff.).

Within our country's complex social composition, examples of ethnophobic songs emerged also on the 'white' side of the ethnic spectrum. In 1998, the industrial rock band Battery9 released the controversial song "Blaas hom" (Shoot him) on their album Wrok (Grudge). In this case, the lyrics suggest the graphic narration of the vengeful shooting of a (presumably) black robber by an infuriated white homeowner (Ballantine 2004: 119). In terms of the thematic focus of this article, such content points to murder on grounds of ideological warfare. In that sense, the lyrics of "Blaas hom" (Shoot him) represented a grim reality of South African society at the time. Indeed, in reaction to black militancy and a general sense of fear and insecurity, extremist right-wing vigilante groups such as the Afrikaanse Weerstandsbeweging (Afrikaner Resistance Movement) and the Boerestaat Party (Boer State Party) had started to take the law into their own hands already towards the end of apartheid (Ottaway 1990). As Baker (2016) observes, reminiscent of the legacy of brutal white minority law, generally, the actions of such groups blatantly disregard the law or human rights.

In post-apartheid South Africa, the presence of a white reactionary alternative structure also reverberates in songs such as "Die land behoort aan jou" (This country belongs to you) and "Ons sal dit oorleef" (We shall survive this).2 While not directly traceable to ethnic violence, these songs symbolise religious and racial sentiments that fuel ethnic distrust and intolerance. Afrikaans singer Bok van Blerk's "De la Rey" (2007), for instance, was venerated among right-wing Afrikaners as a kind of anthem, the song's lyrics being understood as a war cry against oppression and the loss of power the Afrikaner experiences in the new South Africa (Nell 2014: 8). Such responses point to a hardening of Afrikaner dispositions, linked with regressive, victimised versions of Calvinistic and Nationalist ideology (Vanderhaegen 2014: 242). It is notable that visuals incorporated in the video version of "De la Rey" depict images of war, including a nostalgic picturing of Boer warriors carrying guns.

Historical and political causes of resentment towards African foreign nationals

From the perspective of ethnic intolerance, the 'rainbow' has faded and, with it, the vision of an inclusive, non-racial South African democracy. More disturbingly, in the post-apartheid era, increasingly ethnophobic sentiments directed against foreign nationals turned into radical forms of xenophobia - or, as will be argued later on in this section, Afrophobia (see McConnell 2009: 34).3 Ever since the demise of apartheid, South Africa has witnessed an influx of African non-nationals waiting for the birth of a truly democratic South Africa (Morenje 2020: 95; Ndlovu 2019). However, over time it became clear that the state has abandoned the local poor in their quest for survival in an uncertain informal economy (Tarisayi and Manik 2020; Hassim, Kupe and Worby 2008: 6; Hickel 2014: 121). Gelb (2008: 79) identifies economic hardship as a primary driver of resentment towards African foreign nationals. Contributing factors were competition for scarce employment, demands for entitlement, scapegoating, poor living conditions, and the legacy of apartheid (Adam and Moodley 2015: 2; Morenje 2020).

Tella (2016: 144) highlights South Africa's political isolation as one consequence of apartheid that fuelled post-apartheid xenophobia; Morenje (2020) recognises the apartheid regime's gratuitous display of brutality and trampling on human rights as another cause. He views the massive inflow of African migrants into the country after the dawn of democracy as the origin of the pervasive postapartheid hostility towards foreigners. However, while the country's apartheid past is one source of the hatred of African foreigners, the failure of the postapartheid state to address inequality is another (Gelb 2008: 80). As this aversion seems to be focused on African foreign nationals more than any other ethnic group, for the purposes of this article, the term 'Afrophobia' is more relevant than 'ethno- or xenophobia' (Tarisayi and Manik 2019: 7; Tarisayi and Manik 2020).4

The politically explosive state of affairs sketched above first erupted on a national scale when in May 2008, xenophobic violence broke out in Alexandra, Johannesburg, and subsequently spread to seven of South Africa's nine provinces (Hickel 2014: 103ff.). Though attacks did not occur to a similar degree during the following years, they continued in 2011, 2012, and 2013 (Misago, Freemantle and Landau 2015: 13). Again, in 2015, xenophobic attacks against foreign nationals in South Africa escalated, damaging the country's global standing, resulting in strong reactions from other African countries. Importantly, Misago (2019: 1) points out that political mobilisation is the fundamental link between discontent and xenophobic violence (see also Tarisayi and Manik 2020). It is therefore not surprising that, over the past few years, incidents against non-nationals have consistently occurred, despite the government's launch of the National Action Plan to Combat Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance (NAP) in 2019. In fact, Ogunnoiki (2019:1) observes that a wave of attacks erupted in KwaZulu-Natal a day after the NAP was released in 2019.

Pillay's (2008: 12) remark that since 1994 there has been a continual increase in the expression of xenophobic sentiments at both an official and popular level in the country is disconcerting (see also Mpofu 2019: 153). It is therefore inevitable that discourse on the topic would also surface within popular song; either in songs supporting hateful sentiments, or in those that oppose it.

Song as political discourse: the case of "Umshini wami"

In traditional African culture, song forms part of the long-established oral practice of imparting knowledge (Phakati 2019: 127; Osiebe 2017: 439ff.). Within this context, various authors underline the role of music in negotiating politics,5 a phenomenon far more distinct in the music of African people than in the music of so-called First World countries, where resistance is more often voiced through the press and media (Allen 2004: 1). Allen (2004: 4) explains that, historically, African people were seen as functioning predominantly in communal contexts, where music could be deployed by post-colonial politicians to control and activate crowds. However, as will be underlined in my discussion of "Umshini wami", music could simultaneously serve as a communal symbolic expression of dissent.

The introduction to this article stated that political songs endorsing ethno- or Afrophobia have become a disreputable part of South African society's discursive socio-political framework. Within the context of black resistance, "Umshini wami" is a well-known example that denotes interracial conflict and (implicit) violence. Though the song does not explicitly refer to a machine gun or the shooting of Afrikaners or white South Africans, during the apartheid struggle it was sung by members of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the military wing of the African National Congress. Thus, by way of political insinuation, the song has entered the realm of ideological controversy (Mangena 2007):

Umshini wami, umshini wami

My machine (gun), my machine (gun)

We Baba

Oh Father

Awuleth' umshini wami

Please bring me my machine (gun) (Gunner 2009: 27).

"Umshini wami" was first sung publicly by Zuma, Deputy-President of South Africa at the time, during the trial of Shabir Shaik in Durban early in 2005 (Gunner 2009: 28). However, since 2008, the song has become widely associated with xenophobic attacks in South Africa (Mbajwa 2008), and thus entered a different realm of political allusion. Still, during Zuma's period as President of the Republic of South Africa (2009-2018), he continued to wield it as his 'trademark tune'. He denied that his singing of "Umshini wami" was an incitement to racial violence, arguing that, as a freedom-struggle song, it "forms part of South Africa's history and cultural heritage" (news24.com 2007).

At this point, as part of the conceptual framing of this article, Vanderhaeghen's (2014: 31) idea of "othering" and "self-othering" may be considered. Vanderhaegen maintains that othering may concern the relation of an individual to an external group; that is, the "othering" of the self in relation to the "other other"; or that it may involve the "othering" of the self in relation to the self. Regarding the post-apartheid context, Vanderhaegen (2014: 1) says that self-othering is situated within discourses of guilt, loss, fear, belonging, transformation, and reconciliation. This becomes pertinent, especially at a time when an idealised identity such as the so-called 'rainbow nation' is being contested by ideologised discourses of Africanism, nativism, and minority rights. From this perspective, Zuma's initial singing of 'Umshini wami' in 2005 could be interpreted as an instance of both interracial othering and self-othering, distancing himself and his supporters from President Thabo Mbeki's rule.

While Zuma condemned the singing of the song concerning xenophobic attacks (Mbajwa 2008), during the deadly xenophobic upsurge of 2008, the song crossed the boundary between ethno- and xenophobia (Rossouw 2008). As such, its symbolic reach extended beyond the inter-racial conflict entrenched in apartheid-era classifications (Robertson 2011: 456), and those of the in-group factionalism that Zuma sought to fuel. Since 2008, it represented a politics of fear and hatred (see Solomon and Kosaka 2013: 5ff.). As part of the thematic argument of this article, within a context of Afrophobia, the song even came to represent murderous intent and 'war'.

While Zuma's initial use of the song in 2005 pointed to political dissent and political mobilisation that did not necessarily relate to accounts of racism associated with apartheid era stereotyping, by way of a personal statement, Zuma did not hesitate to situate his manipulative use of the song (also) within the realm of black/white racial conflict. In justifying his 'ownership' of "Umshini wami" by likening it with "De la Rey" (Njwabane 2007), from the perspective of Nell (2014: 8) he equated the song with an ethnically inspired war cry.6 Thus, both in the case of "De la Rey" and "Umshini wami", a hardening of racist and racially exclusivist stances were at stake where, from within different sides of the ethnic spectrum, South African were 'fighting for their lives'.

Sundstrom and Haekwon Kim (2014: 22) argue that "nationalised narratives of racism make nations colour-blind to racist incidents that fall beyond the scope of their public conception of racism". Therefore, they maintain that bias directed towards foreign nationals may be lost in nationally recognised narratives of racism (Sundstrom and Haekwon Kim 2014: 21). Perhaps South Africa's complex socio-political composition, irrevocably shaped by the country's apartheid past, indeed obscures the hatred for other African indigenes so predominant among some black South African factions. Though fear may not have been at the operational centre of xenophobic attacks during which "Umshini wami" were initially sung, the words We Baba (Oh Father) / Awuleth' umshini wami (Please bring me my machine) (gun) (Gunner 2009: 27), calling on the higher authority of an ancestral father, or God, culminated in the kind of violent intent that resulted in the macabre killing of a pleading, burning Mozambican while onlookers laughed (Verryn 2008: viii). Within such a setting, song and the toyi-toyiing body became deadly, uncontainable political weapons. Clearly, in this context, the kwerekwere stereotype, with all its dehumanising connotations, took on the image of the enemy.

Songs of diplomacy as a counter for Afrophobic sentiments and violence

While song may incite violent uprising, it may simultaneously play a central role in peace-making processes. Barz's (2012: 6ff.) account of the role of indigenous song and inanga instrumental playing as mediators of unity and reconciliation in post-genocide Rwanda, for instance, documents how, in this context, music first served as a political tool for inciting the hate campaigns that led to large-scale killings, while eventually it aided a resolution of the deadly conflict between ethnic groupings.

Earlier it was noted that South Africa's political isolation during apartheid was one particular cause of post-apartheid Afrophobia. This concerned black foreign immigration, in particular. As was stated, the massive inflow of African migrants into the country after the demise of apartheid resulted in widespread hostility and hatred towards foreigners. An early musical reaction was the erstwhile KwaZulu-Natal based kwaito group Boom Shaka's "Kwere Kwere".

Boom Shaka's "Kwere Kwere" (1994)

The kwaito group Boom Shaka was pioneering later musical responses to xenophobic attacks in South Africa when they released " Kwere Kwere" in 1994 as part of the similarly titled LP, produced by Kalawa Records (discogs. n.d.):

Zimbabwe, Zaire, Zambia, Mozambique7

Bangibiza kwere kwere

they call me kwere kwere

Angithi ngiyasebenza [kahle]

don't I work honestly?

Angibulali muntu

I do not kill anybody

Angidayisi kavhivhi

I do not sell drugs or weapons

I'm a gentleman

Striking a decidedly socially conscious chord, long before Afrophobic violence became a public crisis in the country, Boom Shaka in "Kwere Kwere" spoke on behalf of the despised and hated foreigner. Set over a slow beat, and what Ndlovu (2019) calls "a ragga protest chant", the song's lyrics feature the names of Southern African countries from which foreign non-nationals poured into South Africa post-apartheid. Apart from the derogatory term kwerekwere, the lyrics touch on central aspects of what were to become core topics within the scholarly literature on xenophobia.

First, the pejorative expression kwerekwere points to language barriers between locals and unwanted foreigners, possibly referring to the unintelligible sounds of a foreign language, or a corruption of the word korekore, the Korekore being a sub-group of the Zimbabwean Shona people (WordSense Dictionary, n.d.). As Uzoatu (2017) notes, the term translates to "insults such as white South Africans calling the blacks 'Kaffir' [...]". Furthermore, kwerekwere denotes bio-cultural alienness such as darker skin, a particular style of dress, hairstyle, and even inoculation scars - attributes also used by the South African police to identify African foreigners (see Tella 2016: 145-146). Thus, the term is the epitome of othering and portraying African non-nationals as the "other", and as the enemy.

Akhtar (2007: 7) maintains that the roots of prejudice are traceable to evolutionary, ontogenic, historical, socio-political, and economic bases. While, in his words, discrimination relies on "simplification, certainty and shallowness", its root causes are profound and complex. Moreover, he finds that prejudice, by its very nature, is upheld by a distortion of perspective (Akhtar 2007: 7).

Interconnected with the bio-cultural, socio-political, and economic implications of Boom Shaka's depiction of the unwelcome foreigner, including, however, also those related to the trying socio-economic realities of the majority of South Africans, misrepresentation is a central aspect unveiled by the song. In fact, the non-national's 'testimony' suggests a series of preconceived views and judgements on the part of local citizens. These relate to the kinds of devaluating stereotypes pinned on African foreigners that, indeed, were documented empirically by Singh and Francis (2010: 302ff.). These include the views that foreign nationals are "an enemy"; "a threat to job security"; "a drain on the state", "preferentially treated", and thieves ("they steal our women"). However, from the perspective of the African foreigner, Boom Shaka's "Kwere Kwere" also thematically depicts the fight of 'the other' - which, basically, is a fight for livelihood.

Mthandeni's "Xenophobia" (2015)

In contrast to Boom Shaka's "Kwere Kwere", "Xenophobia " by Maskandi musician Mthandeni, released by Ukhozi Media on the album Xenophobia in 2015, highlights concepts central to the dream of an inclusive non-racial South African democracy ('the rainbow') from an anti-Afrophobic standpoint. Anchored in strong religious values, the lyrics, of which core phrases are reproduced in the discussion below,8emphasise shared humanity, unity, and peace:

Singahlukana impela ngokwebala

We may be different in terms of colour

Sihlukane impela ngokubuzwe

We may be different in terms of nationality

UNkulunkulu uyasithanda sonke

God loves all of us

Thina kumele sihlale ngokuzwana

We must live in peace

True to the tradition of maskandi, Mthandeni's soulful singing in this song is underscored by backing vocalists ("Abavumayo"), and an accompaniment consisting of an acoustic guitar, synthesiser, and drums. While the mood of the song is gentle and peaceful, the opening scenes of the accompanying video repeatedly feature the inscription "Not for sensitive viewers". This is followed by disturbing visuals, including those of the Mozambican Ernesto Alfabeto Nhamuavhe who, during the 2008 xenophobic attacks, was burned alive during the 2008 while bystanders laughed.

Though Mthandeni's "Xenophobia" is a sincere and devout plea for unity among all peoples in South Africa, its generality of approach obscures critical particularities underlying Afrophobic attacks in South Africa and their root causes. The phrase "The government loves all of us", for instance, disregards the failure of the post-apartheid state to address extreme levels of poverty and unemployment in the country and, as Hassim et al. (2008:7) find, to ensure even "basic entitlements of safety, health and the right to secure the means of life". (Ironically, in the video a relaxed Mthandeni is shown cleaning a pool; presumably his own). The phrases "Njengoba nibulalawonke ama foreigner" (Since you are killing these foreigners) / " Nibulalakonke nezingane zawo" (Killing even their children) / "Bangabantu nabo banegazi" (They also have blood just like you); and, further on, "Bangabantu nabo bayakhala" (They also have tears just like you) directly speak to evils of ethnic exclusion and related models of oppression forming part of South Africa's racist history.

Towards the end of the song, the singer directs a sincere plea to the (late) AmaZulu King Goodwill Zwelithini: "Ngenela Hlanga Lomhlabathi" (King of AmaZulu, please intervene) / Ngeneka Silo Samabandla (King of AmaZulu, please intervene) / Abantu bakho badidekile (Your people are lost).

This is an irony since some sectors of the South African society held King Zwelithini responsible for the outbreak of xenophobic attacks in KwaZulu-Natal on account of official statements he made on 20 March 2015 (Phakati 2019: 139140), for which he was harshly criticised by the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC 2016). The royal denied any responsibility for the bloodshed, and his words were eventually found not to have amounted to hate speech or instigating violence against African foreigners. Yet his comments were hurtful and harmful examples of othering, denoting foreign nationals as "criminals" and "lice that needed to be removed" (SAHRC 2016; Spokane Public Radio 2015). From this perspective, Mthandine's appeal comes over as revealing a naïve trust in traditional leadership, overlooking the fact that hostility to foreigners as voiced by high-ranking South African office bearers has steadily increased since 1994 - and so have deadly attacks on foreign nationals (Pillay 2008: 12) - the 'enemy', and 'the other'. Yet in its simplicity, thematically the song emphasises core concepts of tolerance, peace, and unity.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo and Salif Keita, "United we stand, divided we shall fall"

In cooperation with Malian singer and activist Salif Keita, the celebrated male group Ladysmith Black Mambazo released the music video "United we stand, divided we shall fall" in May 2015.9 The song is a plea for peace and unity in South Africa and an end to Afrophobia, produced in the wake of deadly violence against African foreign nationals experienced in KwaZulu-Natal during that year. The group's distinctive Isicathamiya singing style, which has earned them four Grammy awards, here combines with the soaring vocals of Salif Keita, widely known as "Mali's golden voice" (Spokane Public Radio 2015). As a symbolic gesture, the song is sung in isiZulu, English, and Bambara, the most widely spoken indigenous language in Mali. However, by its conciliatory spirit, accompanying visuals also feature slogans in Afrikaans and French: the "oppressors' languages" (Verenig staan ons / Union fait la force).10

One of the most influential musicians on the African continent, as an albino Salif Keita has personal experience of prejudice and difference, devoting much of his talent and time campaigning for tolerance (Brand South Africa 2015). Concerning the project "United we stand", the musicians had hoped that their music could help eradicate the cultural barriers between Africans. As Sibongiseni Shabalala, son of the late Joseph Shabalala, founder of Black Mambazo noted, "Music is a good way to reach millions of people. This will send out a strong message for peace. The song talks about love and respect. We hope it will encourage this."

(Spokane Public Radio 2015)

Ladysmith Black Mambazo and Salif Keita are respected and renowned world music artists. Black Mambazo rose to international fame in the mid-1980s after appearing on Paul Simon's controversial album Graceland (1986). Several of the tracks on which the South Africans cooperated were recorded in South Africa. At the time, this broke the United Nations-approved cultural boycott that had been in effect since 1980, for which Simon was widely criticised. Moreover, some internationally renowned artists thought that Simon's introduction of Ladysmith Black Mambazo to the global popular music stage fell nothing short of opportunistic cultural imperialism (Denselow 2012).

Since collaborating with Simon, the group has found global success, but may be critiqued for commercially propagating fantasised notions of an 'authentic' Africa. This can be seen, for instance, in the visuals of the official music video Homeless, where the musicians are depicted in traditional Zulu warrior attire, filmed against mythical African scenes.11 Byrne (1999) views such a strategy as catering to a rather perverse need of world music fans to see foreign performers in their native dress. This tendency, he believes, feeds the appetite for exotica that, in reality, merely entrenches boundaries between "us" (Westerners) and "them" (the exotic other) (Byrne 1999). In this sense, from a conceptual standpoint as argued in this article, what is perhaps merely a commercial strategy in the video may also be interpreted as a subtle form of cultural self-othering.

Reflecting critically on the phenomenon of world music, Stokes (2012: 112) observes that the celebratory view of global patterns of migrancy since the 1990s is difficult to sustain. He bases this view on the fact that, while migrancy is celebrated as a sign of globalised, postmodern cultural vitality, all too often it leads to political tensions that spill over into protest, rioting, and violence (Stokes 2012: 112). Migrant music drawing on the genres of rap and hip-hop critically highlight issues of race, gender, and sexuality. However, Stokes objects to the fact that such creative expression should be elevated to the level of authentic ethno-fusion, as he believes this not only obscures the darker dimensions of the politics from which such music originates, but also provokes racially exclusivist stances (Stokes 2012: 112).

Hickel (2014: 114) maintains that, rather than inaugurating a new era of cosmopolitan liberalism, globalisation seems to inspire a return to violent forms of parochialism. Indeed, this may be true of the post-apartheid cultural influx where social flows have induced a moral anomie that, among some social groups, has triggered the urge to violently set up social boundaries (Hickel 2014: 104). These developments conjure not only the idea of a hardening of culturally biased dispositions, a central theme in this article but also another: the other as enemy.

Against such hard-line attitudes, "United we stand, divided, we shall fall" takes a stand. Consequently, core phrases of the song, sung in isiZulu, focus on healing metaphors of peace, unity, and love, of which one of the most striking is the notion of Africa as 'home':

United we stand, divided we shall fall,

Asihlanganeni bo, sonke ma Afrika

(Africans, let's all unite)12

Africa is our home

Yeebo

(Indeed, it is)

Make it a better place,

Asihlanganeni bo! sonke ma Africa

(Africans, let's all unite).

Asihlanganeni, asibambaneni, asihlalisaneni ngokuthula

(Let's unite, let's work together, let's unite in peace)

However, the artists also directly refer to violent intent by naming weapons used in the xenophobic attacks:

Thatha lowo mkhonto uwubutha uwuposa ilwandli

(Take that spear and throw it into the ocean)

Thatha leso sbhami sako usilahla ulwandli

(Take that gun and throw it into the ocean)

These phrases clearly relate to bloodshed as documented in the media during 2015; a distressing account of hostility, othering, violence, and even social pathology (see Harris 2002: 169ff.). It may also be seen as relating to the idea of the 'machine' (gun) as propagated in "Umshini wami". Although, within the context of the latter song, the shooting of the enemy is implied rather than stated, as Mann (2018) perceives, when notions of killing enter the vocabulary of political rhetoric, "it becomes murderous speech".

Sinjemgomfula

Similar to the collaborative project "United we shall stand", the song " Sinjengomfula" on the CD Tjoon in (2008), is a collective production by musicians from Mozambique, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. With its evocative subtitle "the great river with many tributaries", the CD features the following inscription: "... regardless of where we were born or what language we speak, we are all one people". As a metaphor for life, and the power of nature, the image of the river, as a prominent feature of this CD, also speaks of moving forward and being a symbolic passageway into the heart of humanity. However, rivers may also mark boundaries, "in-between spaces", or crossroads. In Oliver Kgadime Matsepe's Lesitaphiri (1963), in the brutal face of apartheid, the river is a spiritually rich space - but also a place for grieving. In contrast, Ngugi wa Thiong'o's The river between (1965), portrays the river as a space of division, symbolising the disruptive and dividing influence of colonialism and Christianity on indigenous Kenyan culture (Grobler 2012: 65). In this sense, "Sinjengomfula" may symbolically suggest the profoundly complex nature of uniting different ethnic groups on the African continent, and of attaining the Pan-African dream. Undoubtedly, during the period 1900 up to the 1960s, Pan-African ideology aided the continent to achieve political independence and, in many cases, national sovereignty following the period of colonialism. However, since then, realisation of the Pan-African ideal has become stagnant. In South Africa, specifically, as described in this article, extreme hatred towards foreign African nationals has radically undermined this dream.

In conclusion

My contextualiation and thematic reading of local anti-Afrophobic songs, preceded by a discussion of "Umshini wami" has brought to the fore that addressing Afrophobia in South Africa suggests politically aware and diversified remedial approaches. It was brought to the fore by literature on the topic and media reportage that, in the South African context, Afrophobia is at stake more than xenophobia.

It was found that Afrophobic violence in South Africa may be traced back to the legacy of apartheid and its closed-door policy regarding African immigrants (Asakitikpi and Gadzikha 2015: 221; Phakati 2019: 137ff.). It was also seen that globally, the revival of anti-immigrant politics, instead of inaugurating an era of peaceful liberalism, have resulted in a return to rigid forms of nationalism and parochialism (Hickel 2014: 114). In post-apartheid South Africa, a combination of a previous era of isolation, extreme levels of post-apartheid poverty and unemployment among the majority of local citizens, scapegoating, and bio-cultural prejudice were found to be root causes of Afrophobic attacks (Tella 2016: 142; Harris 2002:169ff).

While in "Umshini wami" two main underlying themes are those of (ideological) 'war' and 'the enemy', the anti-Afrophobic songs discussed in this article protest against concepts of othering, devaluation, stereotyping, prejudice, and misrepresentation, notably in Boom Shaka's "Kwere Kwere". As an antidote to the implied hatred towards foreigners, Mthandeni's "Xenophobia" and Ladysmith Black Mambazo's/Salif Keita's "United we stand" advocate unity, peace, and harmony despite the differences and hatred they acknowledge. Both songs refer to violence against the foreign other; "United we stand", specifically, names the traditional Zulu weapon of the spear, and the gun. In an overarching sense, these songs may all be seen as a symbolic plea for unity among African peoples, countering themes of 'warfare' in ethno- and Afrophobic songs discussed.

While there are various causes and manifestations of Afrophobia in the country, one way of understanding the phenomenon is through representations of otherness and difference as portrayed in the songs discussed, including those emanating from far right, white minority perspectives - but also through themes of reconciliation, unity, and peace advocated by anti-Afrophobic songs. As symbolic exemplifications of people's subjective actions and reactions, the latter group of songs speak to a perceived unified identity that, while figuratively representing a great river with many branches, may bind African people together through the fundamental human rights of morality, justice, and dignity. Yet, as has come to the fore in my discussion of "Sinjengomfula", this is a complex process that would imply overcoming boundaries, cultural 'in-between spaces', and spaces and places of profound and disruptive historical division.

References

Adam H and Moodley K. 2015. Imagined liberation: xenophobia, citizenship, and identity in South Africa, Germany, and Canada. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvrdf322 [ Links ]

Akhtar S. 2007. From unmentallized xenophobia to Messianic sadism: some reflections on the phenomenology of prejudice. In: Mahfouz A, Twernlow S and Scharff DE (eds). The future of prejudice: psychoanalysis and the preventing of prejudice. Lanham: Jason Aronson. [ Links ]

Allen L. 2004. Music and politics in Africa. Social Dynamics 30(2): 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02533950408628682 [ Links ]

Asakitikpi AO and Gadzikvva J. 2015. Reactions and actions to xenophobia in South Africa: an analysis of The Herald and The Guardian online newspapers. Global Media Journal African Edition 9(2): 217-247. [ Links ]

Ballantine C. 2004. Re-thinking 'whiteness'? Identity, change and 'white' popular music in post-apartheid South Africa. Popular Music 23(2): 105-131. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143004000157 [ Links ]

Ballantine C. 2015. On being undone by music: thoughts towards a South African future worth having. South African Music Studies 34(1): 501-520. [ Links ]

Baker B. 2016. Taking the law into their own hands: lawless law enforcers in Africa. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315241883 [ Links ]

Barz G. 2012. Music and (re-)translating unity and reconciliation in post-genocide Rwanda. Acta Academica Supplementum 1: 1-19. [ Links ]

Bethke AJ. 2017. Responding to xenophobia through sacred music: a self-reflexive discussion and analysis of a chamber eucharist. Vir die Musiekleier 37(3): 27-50. [ Links ]

Brand South Africa. 2015. Salif Keita and Black Mambazo call for harmony in Africa. 6 May 2015. Available at: https://www.brandsouthafrica.com/investments-immigration/africanews/salif-keita-and-black-mambazo-call-for-harmony-in-africa [accessed on 10 June 2021]. [ Links ]

Brkic B. 2010. "Kill the Boer": a brief history. Daily Maverick. 29 March. Available at: https://www.google.co.za/amp/s/www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2010-03-29-kill-the-boer-a-brief-history/amp/ [accessed on 18 July 2021]. [ Links ]

Byrne D. 1999. I hate World Music. The New York Times. 3 October. Available at: http://www.davidbyrne.com/news/press/articles/I_hate_world_music_1999.php [accessed on 14 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Chothia F. 2021. Analysis: What's behind the riots? BBC News. 14 July. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-57818215 [accessed on 2 May 2022]. [ Links ]

Coplan D. 1985. In township tonight! South Africa's black city music and theatre. Johannesburg: Ravan Press. [ Links ]

Denselow R. 2012. Paul Simon's Graceland: the acclaim and the outrage. The Guardian. 19 April. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2012/apr/19/paul-simon-graceland-acclaim-outrage [accessed on 28 April 2022]. [ Links ]

Discogs N.d. https://www.discogs.com/Boom-Shaka-Kwere-Kwere/release/15054974 [accessed on 8 June 2021]. [ Links ]

Feketha S. 2022. Professor guns down claim of racial intent in 'Shoot the Boer'. Sowetan Live. 18 February. https://www.sowetanlive.co.za/news/south-africa/2022-02-18-professor-guns-down-claim-of-racial-intent-in-shoot-the-boer/ [accessed on 26 May 2022]. [ Links ]

Gelb S. 2008. Behind xenophobia in South Africa: poverty or inequality? In: Hassim S, Kupe T and Worby R (eds). Go home or die here. Violence, xenophobia and the reinvention of difference in South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. https://doi.org/10.18772/22008114877.9 [ Links ]

Gibbs GR. 2007. Analyzing qualitative data. London: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849208574 [ Links ]

Grobler GMM. 1998. And the river runs on ...: symbolism in two African novels. South African Journal of African Languages 18(3): 65-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/02572117.1998.10587190 [ Links ]

Gunner L. 2009. Jacob Zuma, the social body, and the unruly power of song. African Affairs 108(430): 27-48. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adn064 [ Links ]

Gunner L. 2015. Song, identity and the state: Julius Malema's "Dubul 'ibhunu" song as catalyst. Journal of African Studies 27(3): 326-341. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696815.2015.1035701 [ Links ]

Harris B. 2002. Xenophobia: a new pathology for a new South Africa? In: Hook D and Eagle G (eds). Psychopathology and Social Prejudice. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press. [ Links ]

Hassim S, Kupe T and Worby E. 2008. Go home or die here. Violence, xenophobia and the reinvention of difference in South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. https://doi.org/10.18772/22008114877 [ Links ]

Hayward S. 2022. Julius Malema will live to regret his failure to condemn the slaughter of white people. BusinessDay. 28 February. [ Links ]

HiCKEL J. 2014. "Xenophobia" in South Africa: order, chaos, and the moral economy of witchcraft. Cultural Anthropology 29(1): 103-127. https://doi.org/10.14506/ca29.1.07 [ Links ]

Mangena I. 2007. Umshini Wami echoes through SA. Mail & Guardian. Available at: https://mg.co.za/article/2007-12-23-umshini-wami-echoes-through-sa [accessed on 21 July 2021]. [ Links ]

Mann C. 2018. Counter rise of violent rhetoric in South Africa. Mail & Guardian. 31 May. Available at: https://mg.co.za/article/2018-05-31-counter-rise-of-violent-rhetoric-in-sa/ [accessed on 12 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Matsepe OK. 1963. Lesitaphiri. Pretoria: J.L. van Schaik. [ Links ]

Mbanjwa X. 2008. Umshini isn't a song to kill, says Zuma. Independent Online (IOL). 19 May. Available at: https://www.iol.co.za/news/politics/umshini-isnt-a-song-to-kill-says-zuma-400935 [accessed on 9 June 2021]. [ Links ]

McConnell C. 2009. Migration and xenophobia in South Africa. Conflict Trends 1: 34-40. [ Links ]

Mills AJ, Durepos G and Wiebe E. 2010. Encyclopedia of case study research. Thousand Oaks: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412957397 [ Links ]

Misago JP. 2019. Political mobilisation as the trigger of xenophobic violence in Post-Apartheid South Africa. International Journal of Conflict and Violence 13: 1-10. [ Links ]

Misago JP, Freemantle I and Landau LB. 2015. Protection from xenophobia. An evaluation of UNHCR's Regional Office for Southern Africa's xenophobia related programmes. Johannesburg: The African Centre for Migration and Society, University of Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Morenje M. 2020. Ubuntu and xenophobia in South Africa's international migration. African Journal of Social Work 10(1): 95-98. [ Links ]

Mpofu B. 2019. Migration, xenophobia and resistance to xenophobia and socioeconomic exclusion in the aftermath of South African Rainbowism. Alternation 26(1): 153-173. https://doi.org/10.29086/2519-5476/2019/v26n1a7 [ Links ]

Ndlovu B. 2019. Lyrics of blood ... Popular musicians' battle with xenophobia. The Sunday News. 8 September. Available at: https://www.sundaynews.co.zw/lyrics-of-blood-popular-musicians-battle-with-xenophobia/ [accessed on 10 July 2021]. [ Links ]

NELL W. 2014. Afrikaanse liedtekse in konteks: die liedtekste van Bok van Blerk, Fokofpolisiekar, The Buckfever Underground en Karen Zoid. Unpublished Master's thesis. Pretoria. University of South Africa. [ Links ]

News24. 2007. No end to Umshini wami. News24. 23 December. https://www.news24.com/news24/no-end-to-umshini-wami-20071223 [accessed on 2 May 2022]. [ Links ]

NjWABANE M. 2007. Zuma a 'Bok' for De La Rey. News24. Available at: https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/Politics/Zuma-a-Bok-for-De-La-Rey-20070909 [accessed on 21 Jul. 2021]. [ Links ]

Ogüde J and Nyairo J. 2003. Popular music and the negotiation of contemporary Kenyan identity: the example of Nairobi City Ensemble. Social Identities 9(3): 383-400. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350463032000129993 [ Links ]

Oggünoiki AO. 2019. The impact of xenophobic attacks on Nigeria-South Africa relations. African Journal of Social Relations and Humanities Research 2(2):1-18. [ Links ]

Osiebe G. 2017. Electoral music reception: a meta-analysis of electorate surveys in the Nigerian States of Lagos and Bayelsa. Matatu 49(2): 439-466. https://doi.org/10.1163/18757421-04902011 [ Links ]

Ottaway DB. 1990. Armed vigilante groups forming among some South African whites. The Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1990/04/22/armed-vigilante-groups-forming-among-some-south-african-whites/7aab07e2-1452-4d5f-ad39-921b44418a62/ [accessed on 10 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Phakati M. 2019. The role of music in combating xenophobia in South Africa. African Renaissance 16(3): 125-147. https://doi.org/10.31920/2516-5305/2019/V16n3a7 [ Links ]

Pillay S. 2008. Xenophobia, violence and citizenship. In: A Hadland (ed). Violence and xenophobia in South Africa: developing consensus, moving to action. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

Robertson M. 2011. The constraints of colour: popular music listening and the interrogation of 'race' in post-apartheid South Africa. Popular Music 30(3): 455-470. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143011000262 [ Links ]

Rossoüw M. 2008. The Zuma factor. Mail & Guardian. 24 May. https://mg.co.za/article/2008-05-24-the-zuma-factor/ [accessed on 2 May 2022]. [ Links ]

SAHRC. 2016. Zulu king's comment on foreigners 'hurtful and harmful, but not hate speech': SAHRC. 30 September. Available at: sahrc.org.za/index.php/sahrc-media/news/item/464-zulu-king-s-comment-on-foreigners-hurtful-and-harmful-but-not-hate-speech-sahrc [accessed on 8 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Singh L and Francis D. 2010. Exploring responses to xenophobia: using workshopping as critical pedagogy. South African Journal of Higher Education 24(3): 302-316. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajhe.v24i3.63440 [ Links ]

Solomon H and Kosaka H. 2013. Xenophobia in South Africa: reflections, narratives and recommendations. Southern African Peace and Security Studies 2(2): 5-30. [ Links ]

Spokane Public Radio. Ladysmith Black Mambazo to South Africans: stop Attacking Immigrants. 11 May. Available at: https://www.spokanepublicradio.org/post/african-musicians-team-song-against-xenophobia#stream/0 [accessed on 3 May 2021]. [ Links ]

Stokes M. 2012. The cultural study of music: a critical introduction. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Sundstrom RR and Haekwon Kim D. 2014. Xenophobia and racism. Critical Philosophy of Race 2(1): 20-45. https://doi.org/10.5325/critphilrace.2.1.0020 [ Links ]

Tarisayi K and Manik S. 2019. Affirmation and defamation: Zimbabwean migrant teachers' survival strategies in South Africa. Journal of International Migration and Integration. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-019-00725-5 [accessed on 28 April 2022]. [ Links ]

Tarisayi and Manik. 2020. An unabating challenge: media portrayal of xenophobia in South Africa. Cogent Arts & Humanities 7(1). Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23311983.2020.1859074 [accessed on 28 April 2022]. [ Links ]

Tella O. 2016. Understanding xenophobia in South Africa: the individual, the state, and the international system. Insight on Africa 8(2): 142-158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0975087816655014 [ Links ]

Thiong'o N. 1965. The river between. Johannesburg: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Turino T. 2000. Nationalists, cosmopolitans and popular music in Zimbabwe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226816968.001.0001 [ Links ]

Uzoatu UM. 2017. Xenophobia and the Nigerian Kwerekwere in post-apartheid South Africa. The Guardian. 24 September. Available at: https://guardian.ng/art/xenophobia-and-the-nigerian-kwerekwere-in-post-apartheid-south-africa/ [accessed on 12 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Vanderhaeghen YN. 2014. Other than ourselves: an exploration of "self-othering" in Afrikaner identity construction in Beeld newspaper. Unpublished PhD thesis. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Van der Waal CS and Robins S. 2011. 'De la Rey' and the revival of 'Boer Heritage': nostalgia in the Post-apartheid Afrikaner culture industry. Journal of Southern African Studies 37(4): 763-779. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2011.617219 [ Links ]

Verryn P. 2008. Foreword. In: Hassim S, Kupe T and Worby R (eds). Go home or die here. Violence, xenophobia and the reinvention of difference in South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press: pp. viii-ix. https://doi.org/10.18772/22008114877.3 [ Links ]

WordSense Dictionary. n.d. Kwerekwere. Available at: https://www.wordsense.eu/kwerekwere/ [accessed on 10 August 2021]. [ Links ]

First submission: 15 Augustus 2021

Acceptance: 29 August 2022

Published: 28 November 2022

1 This view was again defended by Gunner during the recent Malema/Afri-Forum court case (Feketha 2022).

2 "Die land behoort aan jou" was released by Afrikaans singers Steve Hofmeyr, Jay du Plessis, Bobby van Jaarsveld, Bok van Blerk and Ruhan du Toit in 2018 on the album Hoor ons! Steve Hofmeyr's "Ons sal dit oorleef" was released on the album Haloda in 2011.

3 A South African Migration Project (SAMP) study (2006) shows that South African nationals are "particularly intolerant of non-nationals, and especially African non-nationals" (McConnell 2009:34).

4 Ogunnoiki (2019: 1) notes that, during violent attacks, anger has been taken out mainly on nationals of neighbouring countries of South Africa. This does not mean that Chinese, Indians, Pakistanis, and other nationals who also inhabit the country, and contribute to its economy, do not live in constant fear.

5 Apart from Allen (2004), see Osiebe (2017); Ogude and Nyairo (2003); Askew (2002), Turino (2000), and Coplan (1985).

6 Thereby constructing a particular manifestation of black South African identity that does not serve racial unity and harmony is a less sinister outcome than the recent frenzy of riots, looting, and arson in South Africa of which the catalyst was Zuma's arrest on 7 July 2021 (Chothia 2021). Whether this violent outburst could be categorized as ethnic mobilization or an attempted insurrection, it represented a massive blow to the country's psychological and economic wellbeing, apart from the immense reputational damage.

7 Cited from Ndlovu (2019).

8 The lyrics of "Xenophobia" and their translation are derived from Phakati (2019: 132-134) and from the video production of the song available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nNQ4LrFIgTM [accessed on 12 May 2022].

9 The video is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4ZqUelM8jPk [accessed on 12 May 2022]. It was released by Quintin Lee White Productions on 1 May 2015.

10 "United we stand": "Strength in unity".

11 The video is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xH6iowG0JNo [accessed on 12 May 2022].

12 My sincere thanks to Eric Sunu Doe, José Albert Chemane and Thulile Zama for their translation of the Zulu lyrics of "United we stand", derived from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xH6iowG0JNo [accessed on 12 May 2022].