Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Academica

On-line version ISSN 2415-0479

Print version ISSN 0587-2405

Acta acad. (Bloemfontein, Online) vol.54 n.2 Bloemfontein 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150479/aa54i2/3

ARTICLES

Reconceptualising Afrophobia in postapartheid South Africa: a conflict transformational perspective

Casper LötterI; Gavin BradshawII

ISchool of Philosophy, North-West University, Potchefstroom. E-mail: casperlttr@gmail.com

IIHistory and Political Studies, Nelson Mandela University, Gqeberha. E-mail: gjbrad54@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Xenophobic violence has assumed a regular appearance in the body politic of South Africa. Such xenophobia/racism is mainly targeted at migrants from elsewhere in Africa. The phenomenon flies in the face of expectations, given the history of the struggle against apartheid, and the role of the frontline states in support of that struggle. It runs counter to the inclusive ethos of the ANC government, the Rainbow Nation and South Africa's progressive constitution. This contribution, in the spirit of conflict transformation, focuses on the occurrence of xenophobia in South Africa. Given the complexity of the context, it seeks to explain the phenomenon, using a selection of commonly used theoretical approaches, mediated through the lenses of the Just World theory, and the notion of state crimes. It challenges any notion of South Africa as a post-conflict society, finds significant government culpability for the episodes, and attempts to provide corrective policy advice, using a dynamical systems theoretical approach.

Keywords: complexity, just world-hypothesis, state crimes, xenophobia/racism, conflict management

The road to genocide in Rwanda was paved with hate speech.

(Schabas 2000: 144).

intellectuals who keep silent about what they know, who ignore the crimes that matter by moral standards, are even more morally culpable when their society is free and open. They can speak freely, but choose not to.

(Cohen 2000: 286).

[F]oreign black Africans, especially those originating from countries north of South Africa's neighbours, are being portrayed as a major threat to the success of the post-apartheid project.

(Morris 1998: 1117).

Introduction

South Africa has experienced regular episodes of xenophobic violence since the early 2000s. In most cases, these attacks have been directed against fellow (black) Africans who have often been political refugees or economic migrants from countries such as Somalia, Nigeria, Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) or Zimbabwe.

Although there have been frequent denials from the authorities of the xenophobic nature of these violent incidents (because it gives the lie to the pro-African stance within the governing ANC's ideology), the explanations given by perpetrators have revolved around typically xenophobic justifications such as foreigners 'taking our jobs', 'raping our women', 'feeding our children drugs, and stealing their futures'.

Most recently, there have been xenophobic outbreaks (Lötter 2021) in the South African cities of Durban (April 2021) and Soweto (16 June 2021). Unfortunately, much of society's anger and mistrust of foreigners is driven by leadership (in both government and community), whether inadvertently or with malicious intent. A community-based organisation, Operation Dudula, which literally means 'to force out', has as its primary goal the removal of foreigners from employment in South Africa (Myeni 2022). Similarly, an insidious practice by South African political leaders, of branding those who they disagree with as 'enemies' or 'enemies within', without even necessarily naming the individuals or groups that they seek to thus implicate, has also developed. A recent example of such demonisation was twice uttered by Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, first in 2017 (Matshiqi 2017), and then later again in 2021, in a speech significantly titled "This phase of our revolution is perhaps most testing, as the enemy is now unseen and operates amongst us".

It demands emphasis that Dr Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, even while being both an ANC National Executive Council (NEC) member and a Cabinet Minister, delivered the above speech at the Chris Hani Memorial Lecture, to the Young Communist League of the University of Witwatersrand. The late Zulu King Goodwill Zwelithini also incited hatred against foreigners in similar fashion, while the term White Monopoly Capital (WMC), having been coined by Bell Pottinger (a UK firm specialising in reputation management), was regularly bandied about in public discourse, including in the South African Parliament, for the benefit of (especially Gupta-aligned) political parties engaging in state capture. Likewise, the Economic Freedom Fighters' (EFF) leadership has also made a habit of demonising 'others' within South Africa.

According to Timmel Du Champ (cited in El-Affendi 2016; l), "The right narrative in politics can win an election, gather a mob, destroy an enemy, start a war." Frequently the same narrative accomplishes all three. This practice has sometimes been termed the 'killer narrative' (Snodgrass 2016), as it portrays certain groups as undeserving of compassion and dignity, and is thus often the prelude to genocidal events or some other form of ethnic cleansing. For instance, before the 1994 genocide in Rwanda local radio stations starting referring to the Tutsis as 'cockroaches', with the implication that they should be 'exterminated' (Tirrell 2012; 176).

Research (Field 2017; Lederach 1997; Masikane, Hewitt and Toendepi 2020; Miall 2004) also shows that xenophobic episodes occur when (largely economic) pressures build in a society, 'demanding' release and resulting in the manifestation of a scapegoat, who is then blamed as the source of all societal misery - such as the case of Jewish people in Nazi Germany. As for the currently intense form of xenophobia in South Africa, it only appeared long after the democratic transition; in 2008, the fear began to justifiably take hold among marginalised South Africans that their abject conditions were showing no signs of improvement. Inequality in South Africa, as measured by the Gini coefficient, has increased significantly since 1994, so that South Africa's rates of income and ownership inequality are now literally the worst in the world (Bax 2019; Orthofer 2016; Piketty 2015; World Inequality Database 2018), and will also continue to increase until our institutions start engaging in genuinely effective interventions (Piketty 2014, 2015). Understandably, then, Field (2017) argues that inequality and perceptions of (relative) deprivation are powerful drivers of xenophobic sentiment, especially in South Africa's low-income areas. Similarly, Tella and Ogunnubi (2014) contend that economic and political instability create favourable conditions for a 'frustration scapegoat' mentality.

When discussing xenophobia, however, researchers usually adopt theoretical approaches that are most immediately useful to their own disciplines, and therefore tend to ignore alternative explanations. In this respect, thematic approaches to xenophobia have included discussion of 'false belief accounts', xenophobia as a 'new racism', 'sociobiological explanations' and "xenophobia as an effect of capitalist globalisation", according to Peterie and Neil (2019) within the context of their wider appeal for a more inclusive and interdisciplinary discourse on xenophobia. To these four explanatory models, operating on a reinforcing plane, we now add two more: the 'Just World' hypothesis (Lerner 1980), and the notion of 'state crimes' (Cohen 2013). In the former case, the popular (and societally foundational) belief in a 'Just World' has traditionally been used to justify systemic 'victim-blaming', such as the veritable criminalisation of poverty (Lerner and Montada 1998). We ourselves argue that this particular worldview not only reinforces the four theoretical models presented by Peterie and Neil (2019), but may also be a basic assumption of these other models attempting to explain xenophobia in the many diaspora communities within the Western world. As for the concept of 'state crimes', this will be considered in order to further our aforementioned explanation.

In this article, we apply all six models to our analysis of xenophobic violence in post-apartheid South Africa, particularly after 2008, in order to draw out its triggers and drivers within 'Africa's oasis'. We do so in the spirit of conflict transformation, as a deeper, more thorough effort to treat xenophobia, which we see as a part of a broader resurgence of social conflict in the country. Our thinking is informed by the notion that xenophobia in South Africa is a largely preventable social phenomenon which finds fertile ground in post-apartheid South Africa's 'perfect storm of political and socio-economic fault-lines'.

South Africa, now the continent's second largest economy after Nigeria, and considered politically stable if not exactly peaceful, is also a 'popular' destination for economic and political refugees, drawing in migrants from all over Africa, South Asia and even China (Maina et al. 2011: 1). We therefore propose, based on a dynamical systems theoretical (DST) approach, some politically unpalatable public policy suggestions, even while being fully aware that policy in this country is largely driven by vested interests.

This article is inspired by the conflict transformation movement within the broader conflict management field. Since the earliest days of the conflict management field, a distinction has been made between two levels of conflict mitigation. So, for instance, Park and Burgess (1932) distinguished between accommodation and assimilation. Whereas much conflict management concentrates on the shallower form of accommodation, which we might also call settlement, and which is typically the result of successful distributive negotiation, some of the literature more ambitiously addresses the deeper, underlying aspects of social conflict, and attempts a more thorough, integrative reconciliation, or assimilation. The goal is not necessarily the end of conflict, but rather its conversion (transformation) into less destructive forms. Conflict transformation represents a further development of the conflict resolution school with which it shares much, and is similar to John Burton's notion of conflict 'prevention'. It recognises conflict as a phenomenon that is always present in society, but is amenable to efforts at amelioration, and therefore envisages conflict transformation attempts as properly long-term, and multi-level programmes, such as John-Paul Lederach's invocation of engagement at top-, middle-, and grass-roots level engagements, where relationship-building may take place through a variety of different approaches including conflict resolution training and problem-solving workshops (Lederach 1997; 43-57).

Problem statement

Despite the fact that South Africa's relatively young democracy started out on a philosophical bedrock of non-racialism and general inclusivity, its recent history has featured all too frequent episodes of racist and xenophobic violence. It is 'racism' since, in our estimation, xenophobia in South Africa is not a general xenophobia against all foreigners, but specifically directed at particular ethnic groups (Harris 2002; 169; Human Sciences Research Council [HSRC] 2008; Masikane, Hewitt and Toendepi 2020; 3). Consequently, the Rainbow Nation now seems but a dim recollection in the face of a much more sordid reality. Meanwhile, these tragic occurrences are frequently denied by most of South Africa's political leaders, who generally ignore the rather horrid extent of the nationwide violence. As we seek an explanation for such violence, we consider six theories, drawn from a range of social science disciplines, which we attempt to apply to the South African experience of primarily 'black-on-black' xenophobia (both Tshishonga [2015] and Masenya [2017] suggest the useful term 'Afrophobia'). In particular, even though we proceed from the assumption that all these theories cross-fertilise and reinforce one another, we especially emphasise the pertinence of the notion of state crimes (Cohen 1973; 624; 2000; 2013) for this discussion. Subsequently, the central argument developed in this paper is that xenophobic violence in South Africa is partially a crime of the state, in the same way that, to give two other examples, the Marikana massacre in 2012, and the political inability and/or unwillingness to eradicate poverty, inequality and unemployment, are also state crimes.

Methodology and theoretical framework

South Africa's unique form of xenophobic violence, as well as the dire economic situation of most of its citizens, is intellectually 'helpful' for explaining the appeal of poststructuralism (Lacan, Derrida and Rancière being representative of this movement or school) as a methodology to explore the complex phenomenon of xenophobia in post-apartheid South Africa. This methodology/tradition's insights will be employed within the context of conflict transformation as our theoretical framework, in order to examine government's denials and incitements of xenophobic violence for political gain, for the purposes of diverting attention away from, not only its many failed socioeconomic projects and atrocious lack of service delivery (Masikane, Hewitt and Toendepi 2020: 9; Odiaka 2017), but also from a phenomenon known in radical criminology as the 'crimes of the state'. Poststructuralism is also eminently suitable for our topic because of its other features, which Andrea Hurst (2004: 42) identifies as "...a common attempt to think in a way that differs fundamentally from the 'either/or' logic that has until recently, governed Western theory... to do justice to the cultural diversity and differences in the world without sacrificing our ability to think".

Therefore, because of the tendency of social issues to present themselves as exceptionally complex phenomena (Hurst 2004: 7, 9-10), Bert Olivier (2015) argues that poststructuralism's "linguistic turn", methodologically speaking, greatly contributed to its considerable advantage over the traditional 'either/or' approach bequeathed to us by Aristotle.

Olivier (2015: 349-350), thus favours poststructuralism's more inclusive 'neither/nor' (or alternatively, 'both/and') approach to theory appropriation. Poststructuralism provides certain profound "ontological registers from the complex intertwinement of which human subjectivity (or 'being' for that matter) can be understood" (Olivier 2015: 349).

We also argue that an eclectic approach (as the situation demands), rather than a monochromatic theoretical lens, would be particularly appropriate for our poststructuralist (methodological) project. This decision was made in the hopes of facilitating greater methodological pragmatism over (unexamined) dogmatism in this article.

Our methodology must also meaningfully complement our chosen theoretical framework of conflict transformation, which has produced much recent scholarship emphasising the multiplicity of the many different causal factors surrounding protracted social conflict (Bradshaw 2008: 18-20), with the understanding that these different causes then require different, or overlapping, approaches to finding possible solutions. For instance, John Burton's (1984) insistence that deep-rooted social conflict is completely distinct (since, for example, unresolved disputes over minor issues could well develop into protracted conflict) from their resultant disputes, and that they therefore require a radically different management approach, is a case in point. We move now to consider a number of divergent theories which attempt to explain racism posing as xenophobia.

Theoretical explanations

Xenophobia may be understood in many different ways. The term itself is Ancient Greek in origin, literally meaning a 'fear and/or hatred of strangers', though it has, in contemporary parlance, come to mostly denote actions or policies directed against the interests of migrants, immigrant communities and/or similar groups. Additionally, Kollapen (1999) and Harris (2002: 170) are of the view that the definition of xenophobia goes beyond mere fear or hatred and must also include acts of violence causing injury and/or property damage. Maina et al. (2011: 2) specify that these acts of violence must also be targeted at someone because of their specific national identity. Clearly, all three elements are present in South Africa's version of xenophobia (Maina et al. op cit.). In addition, communal xenophobia, which usually escalates into mob violence, is also very much a feature of contemporary South African xenophobia (Field 2017). Peterie and Neil (2019) have also helpfully summarised the four main theories concerning the origins of this phenomenon (xenophobia as a global problem): 'false belief accounts', xenophobia as a 'new racism', 'sociobiological explanations' and 'xenophobia as an effect of capitalist globalisation'.

False beliefs seem to be a prerequisite for xenophobia, as migrant communities are negatively associated with various local problems. They may, for instance, be considered disproportionately prone to criminality, or their stated purposes for migration, such as fleeing from gang violence or war, may be disbelieved for less urgent (or even more sinister) motives to seek a more comfortable existence elsewhere. Consequently, they may be seen as 'stealing' jobs or various other scarce resources, as well as being serial rapists. These overwhelmingly false stereotypes are indeed believed to be true by many South Africans (Field 2017). Peterie and Neil (2019) also cite numerous authors who explain how these negative tropes regarding asylum seekers often originate in statements by the government, political leaders and the mass media. This feature of xenophobia in our view also has a strong presence within the South African context.

In addition, many forms of xenophobia are actually symptomatic of a 'new' justification for racism, which prejudges, based not on supposed biological difference but on cultural distinctions. These negative sentiments towards the cultures, religions and languages of the newcomers' other national identities may have resulted mainly from the societal unacceptability of overt racial bias in the contemporary world. In South Africa, this manifests as, for example, the use by locals of terms such as Amakwerekwere (Field 2017), referring to those who speak apparently strange-sounding languages, which is also very similar to the origin of the term 'barbarian'.

A third explanation for xenophobia cited by Peterie and Neil is the sociobiological perspective. Observations in this vein, proposed by scholars such as EO Wilson, emphasise the epistemological influence of the human desire to protect one's own close kin groups (Shaw and Wong 1989). For example, Haidt and Haidt (2012) describe how the evolutionary value of in-group cohesion, as well as of general hostility towards the out-group, for human development partially illuminates the xenophobic mindset. Though often criticised in the sociological literature, such explanations have survived, though usually in modified form, as they are generally considered more relevant to conditions of great environmental stress. Even among animals, territoriality becomes more intense under conditions of food scarcity. Similarly, as South Africa becomes more unequal, and more people become even poorer, an understandable temptation to reject the needs of outsiders, who instead are increasingly seen as a threat, develops, and this perspective becomes more important.

The fourth theory examined by Peterie and Neil is that concerning the relationship between global capitalism and xenophobia. This theoretical consideration pertains to the ways in which the global systems of extraction restructure whole societies across the world. As for government's propensity for catering its agenda to most optimally benefit 'big business', Colin Crouch (2004; 4) explains that in an era of so-called "post-democracy", policy is by design crafted and implemented in violation of the electoral mandate; "Behind this spectacle of the electoral game, politics is really shaped in private by interaction between elected governments and elites that overwhelmingly represent business interests."

To this end, it is worth noting that Angela Davis (2003; 25), John Braithwaite (1995; 289-294) and Naomi Klein (2015; 6-7) all agree that major social paradigm shifts (such as the abolition of slavery and the dismantling of apartheid) ultimately result from individual sacrifice and networking, rather than from government intervention. On the other hand, one cannot but agree with Stiglitz (2019) that "[t] he neoliberal fantasy that unfettered markets will deliver prosperity to everyone should be put to rest".

Unfettered capitalism is also the very historical force that causes the majority of global inequality and resource insecurity (and war?) today (Standing 2014). Therefore, both the global presence of refugees and the increasing economic deprivation of most citizens within contemporary nation-states - these two factors fulfilling the basic material conditions for xenophobia to flourish - are the direct result of free market principles being put into action.

Consequently, as mentioned above, we suggest that the peculiar phenomenon of mostly 'black-on-black' xenophobic (or 'Afrophobic') violence in postapartheid (particularly after 2008) South Africa might be more fruitfully analysed through a further two theoretical lenses, namely Mervin Lerner's (1980) 'Just World' hypothesis and the relationship between the notion of state crimes (Cohen 2000; 2013) and xenophobia.

Lerner's (1980) study of 'Just World' thinking demonstrates, through a range of studies, that most people believe that everyone gets what they deserve, whether good or bad. Lerner (1980) further argues that such people also uncritically value this conviction in a safe, stable and orderly world. The supposed 'contract', which each of us apparently has in place with the world, dictates that good deeds will be rewarded with their just deserts, while the unfortunate must necessarily have done something bad or evil to deserve their current station in life. This approach may be thought of as a special case of the false beliefs theory mentioned by Peterie and Neil (2019) above. When 'bad things' happen, we console ourselves with the thought that 'what goes around comes around' or, in the face of some calamity, that 'this is all part of God's plan'. This very popular belief in a 'Just World' often also functions to justify (especially economic) victim-blaming (Lerner and Montada 1998). Yet Furnham (1993) points out that inhabitants of the Global South, because of their perceived lack of power to meaningfully influence their reality, generally display weaker attachments to any ideas which suggest that the world is essentially fair and predictable. In any case, studies have found that respondents with mostly right-wing authoritarian political views (Lambert, Burroughs and Nguyen 1999), strong work ethics (Furnham and Procter 1989) and/or religiously fundamentalist beliefs (Begue 2002; Kurst, Bjorck and Tan 2000), were more likely to adhere to this 'Just World' perspective. Therefore, since South Africa is known to have a fairly conservative and (often fundamentalist) Christian national culture (with at least 70% of South Africans identifying with some form of Christianity [Government of South Africa 2012; 12]), the prevalence of certain uncritical 'Just World' assumptions are almost a foregone conclusion. Additionally, the existence of this "self-serving bias" (Linden and Maercker 2011) as well as Frank's (1991) well-known argument that less development for the Global South means more for the Global North, help to illuminate the tendencies of other forms of structural violence directed against marginalised groups.

For example, in his historical analysis of the victims of the witch trials during mediaeval and post-mediaeval England (the so-called 'Great Witch-Craze'), for example, Andrew Sanders (1995) explains that the vast majority of accused women occupied a low social and economic status, usually being elderly and often widowed. He also notes, significantly in our opinion, that accusations of witchcraft were often simply pretexts for 'settling' unrelated disputes (Sanders 1995: 118). The same observation has been made concerning the Jewish victims of the Holocaust in Germany and Eastern Europe, where the latter more often than not functioned as a pretence for looting and even simple theft (Chesnoff 2001). As for the South African context, it should come as no surprise that most victims of xenophobic violence are migrants of low social and economic standing (often waiters, delivery men, car guards and the like) and, for those unfortunate enough to be undocumented, also extremely vulnerable to the whims of their tormentors (or employers?) in their host country. In fact, in the insightful words of Bronwyn Harris (2002: 180),

Despite the pervasiveness of South Africa's culture of violence, it is ironic that xenophobia has been represented as something abnormal or pathological. Xenophobia is a form of violence and violence is the norm in South Africa. Violence is an integral part of the social fabric, even although the 'New South African' discourse belies this.

We agree fully with Harris's view that xenophobia is not a pathology but rather an integral part of the South African "social fabric". It reflects a conflict transformationalist understanding that episodes of conflict (such as South Africa's history of apartheid), "leave in their wake traumas, fears, hurts and hatreds" that constitute serious conflict in their own right (Botes 2003). This is an important argument, since a correct diagnosis is essential for an accurate and helpful prognosis that will benefit the wounded.

The sixth theory offered regarding the causes of xenophobia is that concerning so-called 'crimes of the state', a notion advanced by radical, conflict and critical criminologists in the West, particularly Stanley Cohen (1973; 2013) and the Venezuelan investigative journalist Moisés Naím (2013). Examples of such 'crimes' include international climate crime (being the result of world governments' failures to regulate the world's largely unfettered corporate markets), the massacre at Marikana in 2012, and the various incidents of state capture during former President Jacob Zuma's time in office. In this vein, the Oxford historian RW Johnson (2015: 45-49) has no reservations in declaring the wholesale "criminalization of the [South African] state". Yet this hyperbole is an excellent example of the kind of dogmatism that our paper's 'both/and' methodological approach is intended to problematise. Importantly, it is also worth heeding the words of Eugene McLaughlin (2010; 167), namely that "the blindspot [sic] of conventional criminology retains its steadfast refusal to research victimization by the powerful, not least because the state does not recognize nor fund such research". As for this paper, the crime we wish to discuss, committed with impunity by the state, is the incitement of xenophobic violence by a number of South Africa's political leaders - most notably during elections (Maina et al. 2011; 2). Disturbingly enough, Field (2017) even refers to this manifestation of xenophobia as 'institutional'. According to a statement released in 2010 by the Consortium of Refugees and Migrants in South Africa (CORMSA 2010; 2), the trigger for xenophobia lies in leaders' instigating violence in the form of evictions, assault and theft against foreigners in order to strengthen their own power base in the community.

The idea of crimes of the state as explained above informs this paper's rationale, both our somewhat reserved consideration of progressive capitalism (namely its proposed ability [and inclination] to fix the devastation caused by extractive and inadequately regulated markets) and our criticism of government's complicity with 'Big Business' which obviously compromises its ability to intervene in these same markets, and are based in part on our academic respect for the critical tradition within criminology.

In addition, this notion of 'state crimes' is widely accepted within the broader Critical Criminology movement, which comprises many disciplines that scrutinise government's ongoing collusion with 'Big Business.' Subsequently, in the apt words of the Dutch criminologist Willem De Haan (1991; 208), "[w]hat we need is not a better theory of crime, but a more powerful critique of [what kind of behaviour should be defined as] crime". In this same spirit, we suggest that xenophobic violence in South Africa, having come to be encouraged both by leaders in government and by structures within, is at least partially a crime of the state. Concurrently, what feeds into the notion of xenophobia as a crime of the state is a parallel crime of the government's inability, or neglect, to provide basic services to the community, and the obscene levels of inequality and joblessness that result.

Needless to say, these six theories enumerated above neither constitute a numerus clausus (Maina et al. 2011; 5-6) nor are mutually exclusive (Harris 2002; 170-171). Other theories have also been suggested to explain the scourge of xenophobic violence, and concerning the South African context in particular, the so-called 'isolation hypothesis' has been proposed. According to Morris (1998), as well as Masikane, Hewitt and Toendepi (2020; 3), this theory holds that due to the fascist legacy of apartheid, South Africa's national culture suffers from a subtle kind of 'tunnel-vision', so that all outsiders are perceived as potential enemies.

South Africans also expect to be prioritised for opportunities made scarce because of apartheid, and so migrants are seen as a collective material threat (Crush 2008: 2; Field 2017). Additionally, Grosfoguel, Oso and Christou (2013: 11) note that apartheid spacial notions of geographic otherisation are still present in South African racial discourse today and have consequently shaped both local xenophobia itself and the public response to it.

Blatant denial of the existence of xenophobia on South African soil by leadership (former Presidents Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma being cases in point) is also common (Fabricius 2017; Masikane, Hewitt and Toendepi 2020: 6, 8). As with any social phenomenon, single-factor explanations rarely manage to comprehensively illuminate the problem. Thus, our choice of methodology, poststructuralism, was chosen to better facilitate an eclectic approach to theory appropriation (as the occasion might require). We therefore argue that understanding contemporary xenophobia in South Africa requires an approach that utilises all six perspectives, in order to more effectively (and with varying degrees of complexity) explore the numerous factors surrounding these tragically violent occurrences, if only in part at times, and cumulatively in others.

The Myth of South African Exceptionalism

South Africa's political transition to democracy in 1994 was hailed in the academic literature throughout the world as a unique event (Sparks 2003: Preface). To grossly oversimplify, a minority ruling bloc gave up power in a negotiated transition and then the incoming challenger bloc chose reconciliation over vengeance. Historically speaking, this was an extremely unusual outcome (Byrne 2001) resulting in South Africa's relatively bloodless revolution. Yet although South Africa has been widely lauded as an outlying example of such successful conflict management, with terms of praise such as 'miracle', 'Rainbow Nation', etc. being liberally bestowed, a closer examination of the situation raises some doubts as to exactly how effective the 'transformation' in question really was (Sparks 2003; Johnson 2015). South Africa would seem to form part of what the literature terms 'post-conflict' societies (often in reference to countries in the Global South emerging from civil war [Collier 2000]).

After nearly three decades of democracy, however, it has experienced low economic growth, extremely high levels of unemployment and even 'boasts' the most extreme inequality on earth (Bax 2019; Orthofer 2016; Piketty 2015; World Inequality Database 2018). Materially speaking, therefore, the majority of the population has clearly benefited very little from the many promises of liberal democracy. The 'land issue' is also very far from being resolved. Dishearteningly, the rampant corruption of the political class has even led to a veritable 'hollowing out of democracy' (Mair 2013). These and many other serious problems have converged to bring about very frequent protest activity, often accompanied by violence, as well as shockingly high levels of crime, which is also often very violent.

Consequently, to describe South Africa as a post-conflict society would not only be a form of denialism, but would also show a misunderstanding of the very nature of deep-rooted social conflict. If we were to categorise conflicts, as some do (Doyle and Sambanis 2000), according to the number of violent deaths per year, then South Africa is currently in the grip of a low-level 'civil war', and is somehow still as dangerous a country as it ever was during apartheid (Business Tech 2021; Institute for Economics and Peace 2018). Additionally, racial tensions now run as high, or perhaps even higher, than they ever did then (Institute for Economics and Peace 2018).

Yet it is quite irrational, regardless of geographical context, to expect social conflict, being a reality of life, to simply disappear. From a Marxist perspective, low-level conflict might even be productive as, among other things, it highlights issues which need addressing (Coser 1956). Years of research into social conflict (Bradshaw 2008) similarly indicate that it is a normal, and indeed a necessary, consequence of living in a society. It is important, however, to know how to properly manage it, especially deep-rooted social conflict, which is, by definition, even less likely to disappear. Therefore, belief in the historical existence of any 'post-conflict society' is always deeply flawed, and that is even more true of a country suffering from as much deep-rooted (unresolved) social conflict as South Africa. In addition, uncritically, describing South Africa as the product of a 'miracle', a 'Rainbow Nation' or indeed a post-conflict society invariably affects the way that its citizens and their leaders think about the importance of conflict management. South Africans tend to mistakenly assume that the national conflict resolution process is already complete, or that it should be left up to the established political institutions to accomplish. Yet for all the aforementioned reasons, Bronwyn Harris (2002) is right to caution against the conceptualisation of xenophobia as a pathology, rather than an 'normalised' integral feature, of the South African nation-building discourse, the latter being compromised from the start by its brutally violent past, and then, we will add, further encouraged to fester by the cynical politics of a supposedly 'post-apartheid' South Africa.

Current South African politics is replete with examples of service delivery protests and student demonstrations, which have later turned violent to a greater or lesser extent (Ekambaram 2018; Nomarwayi 2019). The immense magnitude of these events, together with the frequent incidents of xenophobic violence, also result in an enormous financial cost to South Africa's economy, in terms of both the damage to its own infrastructure as well as to international perceptions of the country as an investment destination. As for their impact on nation-building, they profoundly threaten the already tenuous sense of social cohesion. Occasional lip-service aside, there is also no collective, nor authoritative, official response from government, except for piecemeal attempts to deal with some of the issues on an ad hoc basis.

In addition, the instrumental role that government structures have played in fuelling both anti-foreigner sentiment and xenophobic violence, highlighted earlier in this paper, has impressed upon us the value of ideological critique. An earlier study (Lötter 2018; 62-63) suggests that ideology essentially creates the illusion that societal relations are fixed and ahistorical. Yet how would such an exercise in unmasking particular or group interests that masquerade as general interests be successfully undertaken? Thompson's (1990; 7) understanding of ideology as "meaning in the service of power" is certainly a fructuous definition of the term. Meanwhile, in its assessment of the discontinuity between reality and mere conjecture, critical theory employs the procedure known as immanent criticism. Horkheimer (1974; 182) envisages a confrontation between immanent criticism and "the existent, in its historical context, with the claim of its conceptual principles, in order to criticize the relationship between the two and thus transcend them". We aim to accomplish these same objectives through our own deconstruction of the inherent violence within South African racism (masquerading as straightforward xenophobia, as we argue) as a social phenomenon.

It is our contention, as shown above, that the challenges facing South Africa after its democratic transition in 1994 include the many failures to attend to the outstanding issues of economic strategy, land ownership, extreme poverty, endemic unemployment, deepening inequality, and the national identity crisis since 1994. South Africa is also, we argue, not a post-conflict society - if indeed there is such a thing. Certainly, conflict transformation as a theoretical school finds little historical basis for such a notion of a society, somehow beyond social conflict. To the extent that it does use the term 'post-conflict' it understands that "...conflict and post-conflict are relative terms as well, and subject to nuance. Post-conflict rarely means that violence and strife have ceased at a given moment in all corners of a country's territory." (Brinkerhoff 2007) Fiedler and Mross (2017; 1) warn that although chances for peace exist, ".policymakers need to be aware of - and prepared for - the high risk of renewed conflict". Leatherman et al. (1999; 8) argue that conflict interventions need "...a rehabilitative dimension oriented to the past, a resolutive dimension oriented to the present, and a preventive dimension oriented to both the present and future." These remedial elements are entirely lacking in the public policy realm in South Africa, despite initial good intentions and efforts. Additionally, these failures of policy to deal with the outstanding issues of South Africa's democratic transition have resulted in huge areas of widespread dissatisfaction that has only worsened with the numerous economic challenges facing the country since 2010.

With all this in mind, we argue that there is no reasonable doubt that Afrophobia hurts the broader project of national cohesion in South Africa. In this regard, Walker, Veary and Maple (2021) have also convincingly shown that excluding migrants from the COVID-19 vaccine roll-out is bound to backfire, since the virus can only hope to be contained if everybody, regardless of their national origin, is inoculated. Whereas, experience shows that migrants are more likely than not to be healthier in general than the local population upon their arrival, this advantage soon falls away as the former encounter discrimination, diminished employment opportunities and 'other' forms of xenophobic violence. Walker, Veary and Maple (2021) indicate that everyone in the country should be vaccinated to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

By analogy, we contend that xenophobia must also hurt the practical application of social cohesion in South Africa, as this and any other form of structural violence also has an impact on our own self-worth and well-being in complicated ways. By the same token, Allister Sparks (2003) argues that the Global North's so-called culture of contentment will always sit uneasy unless the concerns and needs of the Global South are both acknowledged and met. In fact, we are not alone in our thinking in this regard. The ALPS Resilience research group (2019: 92) similarly suggests that their "project [dialogue between communities] has not only helped foreign nationals but South African's [sic] as well to address xenophobia and the importance of community cohesion" (our emphasis). We are of course in full agreement with this sensible approach to strengthening national cohesion.

Transforming Xenophobic Violence in South Africa

It is a somewhat sobering observation that any possible remedy for this culture of xenophobia in South Africa would need to simultaneously address all major local and national issues in their entirety, which would require a conflict transformational effort that would take into account the great complexity of each problem and the situation (system) as a whole. In this regard, the goals of conflict transformation sit comfortably with the useful tradition of Dynamical Systems Theory (DST), to incorporate an understanding of the various drivers of conflict, as well as of those factors that work towards a more prosperous and peaceful society (Vallacher et al. 2010).

If one were to focus on a single manifestation of conflict in South Africa, such as the recurring instances of violent xenophobic outbursts, we could identify various attractors that have collectively formed a 'basin of attraction' for such destructive behaviour, such as a perceived shortage of gainful employment, pervasive poverty, jealousy, perceptions or a reality of others successfully living 'beyond the law', and so forth. Other elements particularly relating to the behaviour of South African political leadership, would also be found, including statements that encouraged animosity towards foreigners, assertions that the latter are especially responsible for the high crime rate, or even dark hints at 'the enemy within'. Likewise, we may add the lack of political will to address this xenophobia (Masikane, Hewitt and Toendepi 2020: 10), which legitimises the violence by blaming it on other foreign nationals (Fabricius 2017) or by condoning the former through inaction (Gordon 2014). Also, the heavy-handed and often brutal approach to the policing of migrants by the South African Police Service (SAPS) communicates to marginalised South Africans that it is indeed (African and Asian) foreigners who are wrongdoers and a constant source of hardship in their lives (Habib 2021; Masenya 2017; Minga 2015). By contrast, a more transformational approach would be to find ways to work against such factors, so as to limit the attractive forces at play therein. In addition, such a strategy could build upon those attractors in South Africa that discourage xenophobic violence, such as a widespread belief in a common African identity, a shared history of struggle against colonialism, and a legacy of explicit support given from several African countries to the South African liberation movements during their exiles in Africa.

Be that as it may, intervention aimed at strengthening these more positive elements might greatly improve South Africans' opinions of foreigners, which would invariably result in more constructive relationships between them and locals. Similarly, in his later works, Burton (2001) called for the broad-based institutionalisation of conflict resolution in society. He had thus moved beyond the promotion of problem-solving workshops and their episodic style of conflict management, in favour of a more proactive, permanent and institutionalised systematic response that therefore takes a more continuous approach towards the management of conflict, or what he called 'prevention'. Burton (2001: np) also wrote that:

The ultimate challenge is the establishment of social and political institutions that are problem solving, and not adversarial or confrontational. If street violence or ethnic conflict is to be avoided, then party political and ideological approaches must give place to interactive analysis, even at a political level.

Indeed, Burton's (2001) statement that "[pa]rliaments, courts, industrial relations, ethnic relations, and every aspect of contemporary societies remain interest driven and adversarial." is especially applicable to post-apartheid South Africa. The day-to-day politics,race relations, and statemets and actions emanating frorm leadership are usuually extremely adversarial, often insens i tive, and frequently accusatoryi In the language of DST, they create attractors for" destructive conflict behaviour. Tshishonga (2015), for example, among other" commentator's, argues that it is common tn owledge that govemmen t does not put in sufficient effort to forestall xenophobic violence against foreign Africans and their property. In particular, we wish to draw attention to the conclusion reached by Maina, Mathonsi,McConnell and Williams (2011:6), namely that l:[t] he response from ieaVets and government departments [...] has thee influence to either encourage or discourage xenophobia. Government has the mandate and the a bility to provide safety and protection for those within its borders, and this includes non-citizens". We of course cannot agree more.

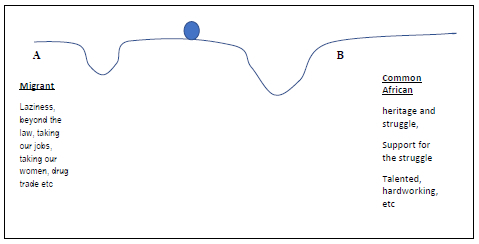

The mechanics of attraction in DST can be represented by hollows in a piain, as in the figure below. The phenomenon, represented by a ball (in our case antimigrant xenophobia) can be attracted towards these hollows, whichever is wider and/or deeper.

Thinking in DST terms, the 'catchment area' of the attractors for a more 'positive favourable view' of migrants could tie much broadmed, and deepened (as in B in figure reproduced above) by government: and civil society,as well as through ongoing and targeted nonfliat intervention s over time - wtich should see a movement away from and/or amelioration of xenophobic episodes, towards a more harmonious and cohesive society. It is also important to note that the application of DST to the xenophobic outbursts is simply one of any number of possible applications to South African fault-lines. For instance, a similar approach could be taken to addressing any one of South Africa's numerous national social ills, such as the conflict over land and the violent protests over the government's various failures at service delivery, among other grievances. As for the topic of this article, such a broadening and deepening of this anti-xenophobic 'catchment area' might include, for instance, the following actions by government and civil society.

Firstly, there needs to be an acknowledgement that xeno/Afropbobia is a real issue. More convincing government statements must be made regarding the value of migrants, their rights, the importance of peace as a prerequisite for development, and the emphasis on more inclusive notions of who South Africans are, instead of the cryptic references to 'our people', or 'especially' this, or that group, which seem designed to drive wedges between South Africa's different communities. There should be a clamp down on individuals and organisations that indulge in scapegoating and/or hate speech. A culture should be fostered, whereby incidents of xenophobic hate speech are routinely reported to the South African Human Rights Commission.

A greater commitment to the promotion of peace, support for values such as tolerance and inclusivity, and the importance of cooperation and collaboration in our education should be made. Educational initiatives, such as peace education and conflict management in schools, which received early and enthusiastic attention after 1994, should now also be more readily funded. There is therefore also a need for a revitalisation of peace and conflict transformation programmes in South African universities, the former of which have largely been allowed to run down, after a golden decade of ground-breaking research since 1994. Such an investment in effort and resources would likely also bear fruit in respect of addressing other fault lines across the country.

Government also has an obvious responsibility to improve the economy by broadening trade relationships, stimulating local industry, relaxing bureaucracy and labour legislation and promoting greater inclusivity by de-emphasising race, all of which would ease the burdens on South Africans across the board.

Simple listening, and greater responsiveness to constituents by political representatives will also help vulnerable South Africans feel less alienated from their own government.

Police need to be sensitised to treating migrants in a professional manner, while brutality towards migrants should be strongly disincentivised and punished.

Although civil society organisations, such as ALPS and Zoë-Life, are doing exceptional work to fight against xenophobia, their efforts have limited reach compared to what government could do were it to prioritise this issue.

Conclusion

Because South Africa's national culture is a complex mosaic of conflict, it is governed by the laws of complexity, one of which being that relatively small system inputs sometimes produce surprisingly large outputs (Byrne 2001). This holds out some hope for action, notably in the form of targeted interventions from a conflict management or transformational (community) perspective, as well as ongoing provention-oriented policies implemented by the South African government.

It is, however, important to sound a note of caution, here. Although the general principles alluded to above are sound, there is still much to be proven, and much research to be done on the real causes of xenophobic conflictual violence in South Africa. These tragic incidents (usually poor people targeting other poor people) are also peculiar in their being almost exclusively 'black-on-black' cases, although Chinese, Pakistani and Bangladeshi traders in townships have also often been attacked and robbed. We argue that it is partially high levels of socioeconomic discontent and misfortune (poverty, unemployment, inequality, crime, etc. [Gordon 2015: 8]) which has laid most of the foundation for this xenophobia (or Afrophobia), with foreigners acting as very convenient scapegoats to divert attention away from the state's many failures and crimes, as certain authority figures see fit to scapegoat foreigners for all manner of social ills, and thereby add fuel to the flames of xenophobic violence (Habib 2021; Masenya 2017; Minga 2015). For example, Ekambaram (2018) contends that rather than inciting public sentiment on xenophobic hatred based on the number of spaza shops owned by foreigners, as the then Minister in the Presidency, Jeff Radebe, infamously has, government should do more to empower local communities to build sustainable business ventures. This trend is very worrisome and demands urgent intervention.

Clearly, the much-flaunted values of equity and national unity supposedly embedded in South Africa's identity as a so-called 'Rainbow Nation' are virtually nothing but a pipedream in the face of the harsh realities of xenophobic violence. Certainly, these narratives fail the test of ideology critique. To argue otherwise merely encourages what Habermas (1970) refers to as 'communicative distortions', and thereby complicates the vital task of ideological critique. As the ALPS Resilience research group (2019) demonstrates, effective intervention to combat xenophobia must necessarily also improve the prospects of social cohesion for all South Africans.

Similarly, inaction and/or denial of the existence of this xenophobia will not help these foreign Africans either. Indeed, as part of our reconceptualisation of local xenophobia (or Afrophobia), it is especially valuable to understand it as part-and-parcel of our relatively 'new normal' post-apartheid nation-building discourse (drawing on a legacy of brutal violence and the urgent need for quick solutions to South Africans' many dire problems). That racism is so deeply entrenched in South Africa's social fabric is indeed disturbing. Moreover, it would also appear as if the prefix 'post-apartheid' in the title of our contribution is perhaps somewhat misplaced as South Africans have not broken with their apartheid past and that continuity in this sense is still perceptible in the present. We disagree with Minga's (2015) view that xenophobia is a reclamation of spacial apartheid, but we argue that it is rather a continuation and perpetuation of a social fabric that did not leave us with the dawn of the so-called 'Rainbow-nation' in 1994. We are therefore living in a dystopia of harsh realities with a myopic and compromised vision, rather than the much-vaunted 'Rainbow Nation' utopia - or at least not from the perspectives of the great many migrants in our country.

It is our contention, though, that an appreciation of the various complexities within South Africa's national culture of social conflict, far from instilling a sense of hopelessness, could enable both a greater popular understanding of these dynamics and enable conflict management as a discipline to approach transformation in a more nuanced and multi-layered manner, in order to benefit from the numerous lessons that DST has to offer. The broader field of conflict management is also a comparatively young scholarly enterprise. Yet recent investigations into its own inherent complexity have led, from the work of John Burton to that from scholars such as Miall (2004) and Lederach (1997), to associate their respective projects with the term 'conflict transformation'. As such, the transformation approach represents the culmination of a collective academic search for a more comprehensive methodology for conflict management. It is also not to be confused with the more general usage of the term in South African political discourse. Using our definition of the term, South Africa is by no means transformed, though improvement - in the sense of conflict transformation - to an extent at least, is possible and certainly achievable. But for this to be a feasible proposition, our leaders must realise that scapegoating vulnerable foreigners and fellow Africans in order to distract from their own failures and crimes, is counterproductive and hurts the South African body politic in complicated ways. Yet history, assuming the more likely outcome, will not judge them kindly for their betrayal of human decency.

References

ALPS Resilience (ALPS) research group. 2019. P2P Synthesis report: people to people dialogues: fostering social cohesion in South Africa through conversation. Available at: https://3bc3d90b-3b34-48f1-82d2-3fed86731588.filesusr.com/ugd/ae1dfd_2f802284b8484630a633d8394b882fdd.pdf [accessed on 18 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Bax P. 2019. Picking Trash for $1.20 an Hour in the World's Most Unequal Nation. Bloomberg, May 12: Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2019-05-12/picking-trash-for-1-20-an-hour-in-the-world-s-most-unequal-nation [accessed on 12 May 2021]. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0262-1762(21)00137-1 [ Links ]

Begue L. 2002. Beliefs in justice and faith in people: just world, religiosity and interpersonal trust. Personality and Individual Differences 32(3): 375-382. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00224-5 [ Links ]

Botes J. 2003. Conflict transformation: a debate over semantics or a crucial shift in the theory and practice of peace and conflict Studies. International Journal of Peace Studies 8(2): 1-27. [ Links ]

Braithwaite J. 1995. Inequality and Republican criminology. In: Hagan J and Peterson R (eds). Crime and inequality. Stanford: Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503615557-014 [ Links ]

Brinkerhoff D (ed). 2007. Governance in post conflict societies: rebuilding fragile states. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203965122 [ Links ]

Burton JW. 2001. Conflict provention as a political system. International Journal of Peace Studies 6(1). [ Links ]

Burton JW. 1984. Global conflict: the domestic sources of international crisis. Brighton: Wheatsheaf Books. [ Links ]

Byrne D. 2001. Complexity theory and the social sciences. Taylor and Francis e-Library. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203003916 [ Links ]

Business Tech. 2021. South Africa's crime stats for the first three months of 2021 - everything you need to know. 14 May. Available at: https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/490627/south-africas-crime-stats-for-the-first-three-months-of-2021-everything-you-need-to-know/ [Accessed on 3 September 2021]. [ Links ]

Carlen P. 2005. In praise of critical criminology. Outlines 2: 83-90. https://doi.org/10.7146/ocps.v7i2.2105 [ Links ]

Chesnoff RZ. 2001. Pack of thieves. London: Phoenix. [ Links ]

Cohen S. 2013 [1993]. Human rights and crimes of the state: the culture of denial. In: McLaughlin E and Munchie T (eds). Criminological perspectives: essential readings (3rd ed.). London: Sage. [ Links ]

Cohen S. 2000. States of denial: knowing about suffering and atrocities. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Cohen S. 1973. Folk devils and moral panics. MacGibbon and Kee: London. [ Links ]

Collier P. 2000. Policy for post-conflict societies: reducing the risks of renewed conflict. New York: World Bank. [ Links ]

Consortium of Refugees and Migrants in South Africa [CoRMSA]. 2010. Migration issue brief 3. Xenophobia: violence against foreign nationals and other outsiders in contemporary South Africa. June. Available at: http://www.cormsa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2009/07/fmsp-migration-issue-brief-3-xenophobia-june-2010-1.pdf> [ accessed on 18 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Coser L. 1956. The functions of social conflict. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Crouch C. 2004. Post-Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Crush JJ. 2008. South Africa: Policy in the face of xenophobia. Migration information source. Available at: www.migrationinformation.org/Profiles/print.cfm?ID=689 [accessed on 27 October 2008]. [ Links ]

Davis AY. 2003. Are prisons obsolete? New York: Seven Stories Press. [ Links ]

De Haan W. 1991. Abolitionism and crime control: a contradiction in terms. In: Stenson K and Cowell D (eds). The politics of crime control. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Doyle M and Sambanis N. 2000. International peacebuilding: a theoretical and quantitative analysis. American Political Science Review 94(4): 779-801. https://doi.org/10.2307/2586208 [ Links ]

Ekambaram S. 2018. Can we truly celebrate Africa month? The Star. 26 May, p. 2. [ Links ]

El-Affendi A. 2016. Genocidal nightmares: narratives of insecurity and the logic of mass atrocities. New York: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Fabricius P. 2017. Xenophobia once again jeopardises South Africa's interests in Africa. ISS Today. Available at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/arcle/2017-03-02-iss-today-xenophobia-once-again-jeopardises-south-africas-interests-in-africa/# [accessed on 21 July 2017]. [ Links ]

Fiedler C and Mross K. 2017. Post-conflict societies: chances for peace and types of international support. Briefing Paper 4. Bonn: German Development Institute. [ Links ]

Field DN. 2017. God's Makwerekwere: re-imagining the church in the context of migration and xenophobia. Verbum et Ecclesia 38(1): 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v38i1.1676. [ Links ]

Frank AG. 1991. Underdevelopment of development. Available at: file:///C:/Users/Lenovo/Downloads/druckversion.studien-von-zeitfragen.net-The%20Underdevelopment%20of%20Development%20(1).pdf. [accessed on 12 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Furnham A. 1993. Just world beliefs in twelve societies. Journal of Social Psychology 133(3): 317-329. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1993.9712149 [ Links ]

FuRNHAM A and Procter E. 1989. Belief in a just world: review and critique of the individual difference literature. British Journal of Social Psychology 28(4): 365-384. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1989.tb00880.x [ Links ]

Gordon S. 2014. Xenophobia across the class divide: South African attitudes towards foreigners 2003-2015. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 33(4): 494-509. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2015.1122870 [ Links ]

Gordon S. 2015. The relationship between national well-being and xenophobia in a divided society. The Case of South Africa. African Review of Economics and Finance 17(1): 80-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2015.1122870. [ Links ]

Government of South Africa. 2012. South Africa's people: pocket guide to South Africa. Available at: https://www.gcis.gov.za/sites/www.gcis.gov.za/files/docs/resourcecentre/pocketguide/004_saspeople.pdf [accessed on 12 September 2021]. [ Links ]

Grosfoguel R Oso L and Christou A. 2017. Racism, intersectionality and migration studies: framing some theoretical reflection. In: Oso L, Grosfoguel R and Anastasia C (eds). Interrogating intersectionalities, gendering mobilities, racializing transnationalism. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315226491-1 [ Links ]

Habermas J. 1970. On systematically distorted communication. Inquiry 13(1-4): 205-218. https://doi.org/10.1080/00201747008601590 [ Links ]

Habib A. 2021. Interview on SABC News. July 26: Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PXUWzMn64lg [accessed on 28 July 2021]. [ Links ]

Haidt J and Haidt J. 2012. The righteous mind: why good people are divided by politics and religion. New York: Pantheon Books. [ Links ]

Harris B. 2002. Xenophobia: a new pathology for a new South Africa? In: Hook D and Eagle G (eds). Psychopathology and social prejudice. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press. [ Links ]

Horkheimer M. 1974 [1947]. Eclipse of reason. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Human Sciences Research Council [HSRC]. 2008. Citizenship, violence and xenophobia in South Africa. Pretoria: HSRC. [ Links ]

Hurst AM 2004. Thinking about research: methodology and hermeneutics in the social sciences. Port Elizabeth: PE Technikon. [ Links ]

Institute for Economics and Peace. 2018. Global peace index. Available at: https://www.hsdl.org/c/from-the-institute-for-economics-and-peace-2018-global-peace-index/ [accessed on 16 December 2020. [ Links ])

Johnson RW. 2015. How long will South Africa survive? The looming crisis. (1st ed). Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball. [ Links ]

Klein N. 2015. This changes everything: capitalism vs. the climate. London Penguin. [ Links ]

Kollapen J. 1999. Xenophobia in South Africa: the challenge to forced migration. Unpublished seminar. 7 October. Johannesburg: Graduate School, University of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Kurst J, Bjorck J and Tan S. 2000. Causal attributions for uncontrollable negative events. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 19(1): 47-60. [ Links ]

Lambert AJ, Burroughs T and Nguyen T. 1999. Perceptions of risk and the buffering hypothesis: the role of just world beliefs and right-wing authoritarianism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 25(6): 643-656. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167299025006001 [ Links ]

Leatherman J, Vàyrynen R, Demars W and Gaffney P. 1999. Breaking cycles of violence: conflict prevention in intrastate crises. Politics Faculty Book and Media Gallery, no. 2. Available at https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/politics-books/2 [accessed on 3 June 2022. [ Links ])

Lederach J-P. 1997. Building peace: sustainable reconciliation in divided societies. Washington DC: United States Institute of Peace. [ Links ]

Lerner MJ. 1980. The belief in a just world: a fundamental delusion. New York: Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0448-5 [ Links ]

Lerner MJ and Montada L. 1998. An overview: advances in belief in a just world theory and methods. In: Montada L and Lerner MJ (eds). Responses to victimizations and belief in a just world. New York: Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-6418-5 [ Links ]

Linden MJ and Maercker A. 2011. Embitterment: societal, psychological, and clinical perspectives. Vienna: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-211-99741-3 [ Links ]

Lötter C. 2018. The Reintegration of ex-offenders in South Africa based on the contemporary Chinese model: an interdisciplinary study. Unpublished PhD thesis. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State. [ Links ]

Lötter C. 2021. Atlanta killings illustrate the intersection of xenophobia and misogyny. Mail and Guardian Thoughtleader. March 24: Available at: https://thoughtleader.co.za/atlanta-killings-illustrate-the-intersection-of-xenophobia-and-misogyny/ [accessed on 4 September 2021]. [ Links ]

Maina G, Mathonsi N, McConnell C and Williams G. 2011. It's not just xenophobia: factors that lead to violent attacks on foreigners in South Africa and the role of the government. Umhlanga Rocks, Durban: The African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD). [ Links ]

Mair P. 2013. Ruling the void: the hollowing out of Western democracy. London: Verso. [ Links ]

Masenya MJ. 2017. Afrophobia in South Africa: a general perspective of xenophobia. Bangladesh Journal of Sociology 14(1): 81-88. [ Links ]

Masikane CM, Hewitt ML and Toendepi J. 2020. Dynamics informing xenophobia and leadership response in South Africa. Acta Commercii - independent Research Journal in the Management Sciences 20(1): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v20i1.704 [ Links ]

Matshiqi A. 2017. The enemy within is the biggest threat to the ANC and country. Business Live Premium. 14 December. Available at: https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/politics/2017-12-14-the-enemy-within-is-the-biggest-threat-to-the-anc-and-country/ [accessed on 3 June 2021]. [ Links ]

McLaughlin E. 2010. Critical Criminology. In: E McLaughlin and T Newburn (eds). The Sage Handbook of Criminological Theory. London: Sage, pp. 153-174. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446200926.n9 [ Links ]

Miall H. 2004. Conflict transformation: a multi-dimensional task. Berlin: Berghof Centre for Constructive Conflict Management. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-663-05642-3_4 [ Links ]

Minga KJ. 2015. Xenophobia in literature and film as a re-claim of space and re-make of apartheid. Global Media Journal, Africa Edition 9(2): 268-297. [ Links ]

Morris A. 1998. 'Our fellow Africans make our lives hell': the lives of Congolese and Nigerians living in Johannesburg. Ethnic and Racial Studies 21(6): 1116-1136. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419879808565655 [ Links ]

Myeni T. 2022. What is Operation Dudula, South Africa's anti-migration vigilante? Al Jazeera News. 8 April. Available at https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2022/4/8/what-is-operation-dudula-s-africas-anti-immigration-vigilante [accessed on 3 June 2022]. [ Links ]

Nai'm M. 2013. The drug trade: the politicization of criminals and the criminalization of politicians. In: McLaughlin E and Munchie T (eds). Criminological perspectives: essential readings (3rd ed.) London: Sage. [ Links ]

Nomarwayi T. 2019. The anatomy of violent service delivery protests with a specific reference to Walmer Township, Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality, Eastern Cape (2012-2015). Unpublished DPhil thesis. Gqeberha: Nelson Mandela University. [ Links ]

Odiaka N. 2017. The face of violence: rethinking the concept of xenophobia, immigration laws and the rights of non-citizens in South Africa. Brics Law Journal 4(2): 40-70. DOI: 10.21684/2412-2343-2017-4-2-40-70. [ Links ]

Olivier B. 2015. The tacit influences on one's ways of teaching and doing research. Alternation Special Edition 16: 346-371. [ Links ]

Orthofer A. 2016. Wealth inequality in South Africa: insights from survey and tax data. REDI3x3 Working Paper 3, June: Available at: http://www.redi3x3.org/sites/default/files/Orthofer%202016%20REDI3x3%20Working%20Paper%2015%20-%20Wealth%20inequality.pdf [accessed on 12 May 2021]. [ Links ]

Peterie M and Neil D. 2019. Xenophobia towards asylum seekers: A survey of social theories. Journal of Sociology 56(1): 23-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783319882526 [ Links ]

Piketty T. 2014. Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge, MA: BelknapPress. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674369542 [ Links ]

Piketty T. 2015. Transcript of Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture. Available at: https://www.nelsonmandela.org/news/entry/transcript-of-nelson-mandela-annual-lecture-2015 [accessed on 2 June 2020]. [ Links ]

Sanders A. 1995. A dead without a name. The witch in society and history. Oxford: Berg. [ Links ]

Schabas W. 2000. Hate speech in Rwanda: the road to genocide. McGill Law Journal 46: 141-171. [ Links ]

Shaw P and Wong Y. 1989. Genetic seeds of warfare: evolution, nationalism, and patriotism. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Snodgrass L. 2016. South Africa's politicians must guard against killer narratives. The Conversation Africa. 20 July. Available at: https://theconversation.com/south-africas-politicians-must-guard-against-killer-narratives-62562 [accessed on 17 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Sparks A. 2003. Beyond the miracle: inside the new South Africa. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball. [ Links ]

Stiglitz JE. 2019. Progressive capitalism is not an oxymoron. The New York Times. 19 April. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/19/opinion/sunday/progressive-capitalism.html [accessed on 14 February 2021]. [ Links ]

Tella O and Ogunnubi O. 2014. Hegemony or survival: South Africa's soft power and the challenge of xenophobia. Africa Insight 44(3): 145-163. [ Links ]

The New York Times. 2021. Census updates: survey shows which cities gained and lost population. August 13: Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/live/2021/08/12/us/census-results-data#census-demographics-asian-hispanic [accessed on 18 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Thompson JB. 1990. Ideology and modern culture. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Tirrell L. 2012. Genocidal language games. In: Maitra I and McGowan MK (eds). Speech and harm: controversies over free speech. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Tshishonga N. 2015. The impact of xenophobia-Afrophobia on the informal economy in Durban CBS, South Africa. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa 11(4): 163-179. https://doi.org/10.4102/td.v11i4.52 [ Links ]

Vallacher R, Coleman P, Nowak A and Bui-Wrzosinska L. 2010. Rethinking intractable conflict: the perspective of dynamical systems. American Psychologist 65(4): 262-278. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019290 [ Links ]

Walker R, Veary J and Maple N. 2021. Excluding migrants undermines the success of COVID-19 vaccine rollouts. The Conversation Africa. July 28. Available at: https://theconversation.com/excluding-migrants-undermines-the-success-of-covid-19-vaccine-rollouts-164509 [accessed on 18 August 2021]. [ Links ]

World Inequality Database. 2018. World inequality report. Available at: https://wid.world/ [accessed on 12 May 2021]. [ Links ]

First submission: 18 October 2021

Acceptance: 29 August 2022

Published: 28 November 2022