Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Academica

On-line version ISSN 2415-0479

Print version ISSN 0587-2405

Acta acad. (Bloemfontein, Online) vol.54 n.1 Bloemfontein 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150479/aa54i1/6

ARTICLES

The middle remains missing: class exclusion from the urban rental market in suburban Johannesburg

McKayI; Nomfundo FakudzeII; Ashley GunterIII

IDepartment of Environmental Science, University of South Africa. E-mail: mckaytjm@unisa.ac.za

IIGordon Institute of Business Studies, University of Pretoria. E-mail: kudzaiishe.vanyoro@wits; ndfakudze@gmail.com

IIIDepartment of Geography, University of South Africa. E-mail: gunteaw@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

There is a huge demand for housing in Johannesburg, South Africa, due to significant in-migration as well as the legacy of apartheid. Rental housing supply in Johannesburg is particularly constrained. Despite this, little is known about the formal rental market in terms of middle income access. Thus, this explorative qualitative study seeks to partially address this research gap. Results show that specific legislative constraints, namely the National Credit Act and the Prevention of Illegal Eviction and Unlawful Occupation of Land Act, have created an imbalance between the rights and responsibilities of landlords and tenants, driving onerous credit checks and documentary demands, all of which are inadvertently excluding individuals from the formal rental market. Thus, while race previously excluded many from the suburbs under study, class now seems to be a significant factor in terms of who can access rental property. As such, rental housing supply is to some degree artificially constrained.

Keywords: Middle income, rental housing, Johannesburg, National Credit Act, PIE Act, South Africa

Introduction

The lack of affordable rental housing is a crisis for many urban areas the world over, especially so in cities with constrained housing markets. The global south is particularly affected (Gilbert et al. 1997; Watson & McCarthy 1998; Collinson 2011; Baranoff 2016). Part of the problem is that, since the 1970s, state provision of affordable housing has declined due to lack of capacity. Thus there is not enough housing stock - especially in the light of massive urbanisation and global population growth - leaving most housing development to the private sector (Roux 2013). As a result, most rental accommodation in the global south is privately provided and subject to market forces. This has resulted in a supply and demand mismatch, especially for rental accommodation for the emerging middle class, who generally find renting more flexible and affordable than home ownership.

South African cities have not escaped this problem, especially as they are experiencing some of the highest population growth rates in the world, due to both internal migration and immigration (McKay et al. 2017). Currently around 65 percent of South African residents are urbanised, creating an acute demand for accommodation (McKay 2020). This has placed upward pressure on house prices, negatively affecting affordability (Lee 2009). Rental properties are also in high demand, with resultant increases in rental costs. The high cost of accommodation, combined with irregular and low incomes, are significant barriers to accessing affordable accommodation in South Africa (Gunter 2014). Gunter and Massey (2017) note that one of the consequences is a massive rise in informal housing and backyard rentals. However, a less well documented consequence is the impact on the formal rental housing market. That is, the emerging middle class faces a critical shortage of affordable accommodation. As such, this group must make difficult spending trade-offs such as skimping on some necessities, accepting substandard housing or residing in ever increasing numbers on the urban periphery (Badger 2016; Crankshaw 2022). As a result, the quality of life of such households is negatively affected. Thus, the provision and availability of affordable urban rental housing is a critical element in sustaining the middle class.

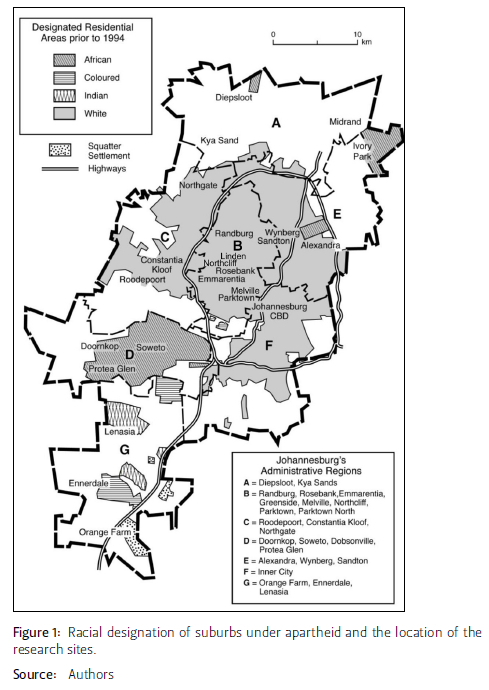

Within this context, South Africa's largest, wealthiest city, Johannesburg, faces significant accommodation challenges. At the same time, Johannesburg is one of the most unequal cities worldwide (Leibbrandt et al. 2010). In the context of urban housing, much of the problem can be attributed to former racial discriminatory practices, such as: The Land Act (No 27 of 1913); The Native (Urban Areas) Act (No 21 of 1923); The Natives Urban Areas Consolidation Act (No 25 of 1945); and the Group Areas Act (Act No 41 of 1950). These acts forced people of colour to live in peripheral, geographically marginalised communities (Rex et al. 2014; McKay 2015). Furthermore, insufficient housing was built to accommodate people of colour. Additionally, post-1994, as with most other cities in South Africa, Johannesburg's population has grown rapidly. People from all over the country, region, continent (and world) are moving to Johannesburg, so demand for accommodation is great (StatsSA 2012). For example, the Housing Development Agency maintains that the city has a backlog of one million housing units. As low incomes place home ownership beyond the reach of most households, most (88%) of Johannesburg's residents live in rented units (HAD 2012). Overall, demand for affordable accommodation outstrips supply, pushing up prices and forcing many to reside on the urban fringe in 'township' settlements first planned by the apartheid government. In particular, accommodation for the emerging middle class, in geographically sought-after areas close to the city centre, amenities and places of work, is severely limited. These limits have significant consequences in post-apartheid South Africa. It is posited here that limited accommodation and high demand may be having a prohibitive effect on where South Africa's emerging multi-racial middle class can live. Exclusion or barriers to entry into living in affordable geographically central spaces may be perpetuating an uneven surface of economic and social opportunity (Morton 1998). Within this context, this study explores the complexities of the rental market within selected former 'whites only' suburbs of north-central Johannesburg. Data was collected using qualitative interviews with real estate agents who operate in these spaces to obtain an understanding of nature of the market in the study location.

Housing in the Global South

Affordable housing has different definitions, but usually it is linked to earning potential, with a common definition being "a measure of expenditure to the income of a particular household" (Gopalan & Venkataraman 2015:132). Thus, there is an affordable housing continuum, where different market segments and categories of accommodation exist based on ability to pay (Ram & Needham 2016). Therefore, low-income households are the most likely to struggle to secure accommodation. Although most countries of the global south have policies and instruments to deal with housing shortages, the private sector provides the bulk of the available accommodation (Joshi et al. 2012). Unfortunately, private provision of housing is woefully inadequate (Echeverry et al. 2007). When accommodation is provided by the private sector, it usually means access is strongly linked to income, leaving households vulnerable to profiteering and above inflationary prices for inadequate stock. For example, in Latin America, there is a shortage of housing units, a lack of proper services, overcrowding and many informal settlements (Ahmad 2015). When the state does build housing, the units are usually far away from job opportunities and facilities (Gilbert 2011). In Africa, despite the presence of noble sounding housing policies and strategies, there has been a singular failure to deliver sufficient accommodation (Mafukidze & Hoosen 2009). This is rather different to Asia, where a majority of working and middle class have become homeowners due to a combination of state-driven social and economic policies (Ronald & Doling 2010). This is in part due to Asian governments viewing housing as a signifier of proper welfare provision. For example, Hong Kong and Singapore have enjoyed massive state intervention through public housing programmes that created a "tenure-secure, low-rent safety net for many families" (Rapelang 2013:47).

In terms of income, macro-economic factors come into play, which then influence ability to pay for accommodation (Watson 2011; Gilbert 2014). These factors include the inflation rate, level of employment/unemployment, interest rates, exchange rates and real gross domestic product (GDP) (Gunter 2014). High interest rates tend to dampen house demand, reduce home ownership and even cause house prices to fall. Lower interest rates allow households to borrow more, which tends to increase home ownership but, again, may push up house prices, and rental costs as well (Gunter 2013). Therefore, interest rates can exclude households from home ownership, forcing them into rental accommodation. Growth in GDP is usually associated with rising real incomes and improved purchasing power of households. While this can increase access to accommodation, in a situation where demand outstrips supply, it can also increase accommodation costs. A good example are the steps taken in February 2022 against Russia due to its invasion of Ukraine, which has resulted in a collapsed Russian rouble, increased interest rates and thus the strong possibility of ordinary Russians losing their accommodation due to an inability to pay. A falling GDP may lead to a decline in household incomes dampening demand and lead to price stagnation (or even deflation). So, home ownership may decline while demand for rental accommodation increases (Gerxhani 2004). Large fluctuations in the exchange rates also affect house prices and affordability levels (Beall 2002). Government policies can influence household incomes and savings and so have a direct impact on housing demand and affordability (Forrest 2011), for example providing tax relief on mortgage payments (Ahmad 2015). In addition, government policies concerning infrastructure development, land and housing supply policies also influence housing supply and house prices (Obeng-Odoom & Amedzro 2011; Todes 2012; Roux 2013). The same is true for planning regulations such as zoning rules, building codes, subdivision and density regulations, property taxation and other fiscal policies by both national and local government (Sabal 2005; Gunter 2013). Strict and unresponsive planning authorities reduce supply, causing housing prices to rise (Massey 2013). High building standards and strict building codes also increase the cost of housing. Development regulations can prolong the time taken to obtain building approvals, discouraging developers. Environmental rules and regulations also influence housing costs and supply (Autor et al. 2014; Desmond 2015). These issues have been particularly noted in South Africa's Western Cape province as ones that constrain housing supply (Zille 2017).

Affordable rental housing

Metrics to determine rental affordability were first used in the United States of America (USA). Consequently, 30 percent of one's income was deemed the maximum proportion one should pay for accommodation (Desmond 2015; Gopalan & Venkataraman 2015). For rental purposes, the 30 percent includes the utility bills, whereas in the case of bank financing a home loan, the amount would include mortgage repayments, taxes, property insurance, utility bills, refurbishments and maintenance. In Australia, housing is deemed affordable by determining if households in the lowest 40 percent of the disposable income bracket are paying 30 percent or less of their income on housing (Iwata & Yamaga 2008). Nevertheless, affordability should also take transport costs into consideration. That is, affordable housing is usually a trade-off between location and transportation costs, where housing stock far from economic nodes is usually more affordable but transportation costs are often high (Shrestha 2010; Gopalan & Venkataraman 2015).

A good rental housing system provides a variety of housing options at affordable prices and grants residents ease of access to amenities and facilities (Badger 2016). For example, in the United Kingdom (UK), affordable rental housing is known as 'social rented housing'. Eligibility for such housing is given to those who cannot afford to rent on the open market. There is also Intermediate Housing, targeting households earning above the social rented housing threshold but unable to afford open market rental housing. Additionally, there is the Affordable Homes Programme (AHP) where 20 percent of the rent is paid by the state (Mulliner & Maliene 2013). Although affordability is the most common reason why people opt to rent, there are others (Autor et al. 2014). For example, those with irregular incomes may opt to rent. Others want to set aside resources for long-term investments (such as education, vehicles) or need to support their extended family (Marais et al. 2010). Some rent as their job requires them to be on the move (Watson & McCarthy 1998; Rust 2006). Furthermore, what amount people are prepared to pay in rent is also driven by several factors, such as (i) the quality of the accommodation, (ii) access to basic infrastructure and services, and (iii) access to public services and the 'neighbourhood' in general. It follows that popular neighbourhoods are usually close to places of work. Homes in such neighbourhoods get higher rents and houses are worth more.

Rental housing in the South African context

In South Africa, insufficient attention has been paid to issues of rental accommodation (Scheba & Turok 2020). The Reconstruction and Development Programme Housing Programme, the National Housing Finance Corporation (NHFC) and Rural Housing Loan Fund all focus on enabling people with a low income to own a house, rather than assisting people to rent (Tissington 2011). Furthermore, those caught between earning 'too much' to be eligible for state subsidies, but too little to purchase a home on the open market (for households earning between R3 501 to R15 000 per month), can access the Finance Linked Individual Subsidy Programme (FLISP) whereby they can receive a once off capital contribution of between R87 000 to R100 000 towards their mortgage bond (Moss 2012; Rust 2013). Despite this, homeownership remains low. For the most part, most South Africans earn too little to own a home and few manage to save up the large deposits that the banks are now demanding (at least 10 percent). Also, house price growth has outstripped income growth, also negatively affecting homeownership. In view of this, many in South Africa cannot afford to buy a home and so rent.

In that regard, important pieces of legislation have an impact on the South African rental landscape. One is the National Credit Act (NCA) No 35 of 2005. The NCA serves to protect consumers in the credit market by prohibiting reckless lending and establishing recourse for unfair credit practices (Haupt et al. 2007). Its relevance for rental accommodation lies in its stipulated loan application procedures and sections prohibiting irresponsible lending (de Stadler n.d.). The act requires credit providers to do comprehensive credit checks to ensure consumers can afford the loan. All loans need to be recorded to prevent consumers becoming over-indebted. Failure to do this will be viewed as contravention of the NCA and the credit provider could be found guilty of reckless lending. Another act is the Rental Housing Act (No 50 of 1999) (Legwaila 2001). The act has been amended several times: see the Rental Housing Amendment Act 35 of 2014 (Sections 1-7, 9-10, 13-17) and Rental Housing Amendment Act 43 of 2007 (Sections 1, 4-5, 9-10, 13, 15-16, 19). This act regulates rental housing and the relationship between landlords and tenants. Lastly, there is the Prevention of Illegal Eviction from and Unlawful Occupation of Land Act (PIE), Act No 19 of 1998, which provides legal protection for tenants from eviction. This act protects the rights of unlawful occupiers of land from being unilaterally evicted by the landowners (Strauss and Liebenberg 2014).

Methodology

This study sought to fill the gap in terms of how the middle income rental market (those paying between R5 000 and R10 000 per month for accommodation) is served (SALGA 2011; Gunter and Manuel 2016). This rental range was selected on basis that the average nett monthly income (used by rental agents to determine affordability) of those in formal employment was R14 385 in 2019 (Businesstech 2019). Thus, an individual earning this is likely to qualify for a rental of R5000 per month. If two people are living together, their joint income could qualify them for a rental of R10 000 per month (Tuphome, pers comm 2017). Zizzamia et al (2019) estimate around 50% of the South African population are chronically poor, 25% are transient and vulnerable, 21% are solidly middle class, and 4% are elite. This 21% middle income group is racially mixed - consisting of roughly 66% Black African, 20% white, 9% Coloured and 5% Indian. Other characteristics of this group are that the households are small with few children. Income is derived mainly from the labour market, they are mostly urban-based, and most reside in Gauteng and the Western Cape. Thirty seven percent have a tertiary qualification of some sort.

Purposive sampling was utilised to select centrally located middle-income Johannesburg suburbs, namely Rosebank, Melville, Linden and Randburg. The study then sought to explore the rental market within these suburbs. These suburbs are close to the economic heart of Johannesburg (Sandton and the Central Business District), where a significant number of Johannesburg residents work. While there are no longer any racial segregation laws in South Africa, and the post-apartheid government has pushed for racial integration, there are clearly racial groupings in suburban Johannesburg. For example, in 2011 whites made up 48%1; 55%2; 67%3 and 46%4 of the population of Rosebank, Melville, Linden and Randburg respectively. Thus, the racial makeup of these areas does not represent the demographics of Johannesburg as a whole, as only 12% of the total population of Johannesburg are white5. The suburbs and the racialised spatial nature of these suburbs under apartheid is visible in Figure 1.

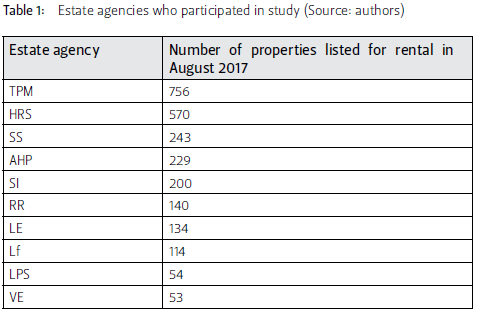

In order to investigate the rental landscape of Johannesburg, with a specific reference to middle-income households, this study utilised in-depth, semi-structured interviews with real estate agents, based on an online search for agencies advertising residential units to let. As such 20 estate agencies, ranging from large global branded agencies to smaller local agencies, were found to be operating in the rental business in the areas under study. Of these, 10 companies were selected to participate in the study, based on market dominance (see Table 1). Face-to-face interviews were held in 2017 between the researchers and representatives from each office. The interviews lasted approximately one hour and data was transcribed and then coded using thematic analysis.

This is an explorative study and so the results are not generalisable. It is also limited to the views of the estate agents. Thus, we recommend further studies with a focus on tenants, landlords and city authorities. However, the qualitative nature of the study allows for a first investigation into this important segment of the market. The study obtained ethical clearance from the University of Pretoria.

The supply side nature of the rental market in Johannesburg

A key emerging theme was that affordability is viewed by estate agents as a function of income and credit records. Most respondents said that "credit ratings and/or records and income" was the major challenge facing the sector. Respondent J said tenants were struggling to source affordable accommodation within their income bracket, "At the moment it is difficult for people in the middle income range to find anything they can afford as we demand three times the rental as an income. R10 000 does not give one much scope. So affordability is a problem." Respondent 6 emphasised that creditworthiness is a key factor in accessing rental units. Respondent 5 mentioned that: "An assessment of the credit record and application process is a hurdle. There are many applications but most fail to meet the income threshold as required for becoming a tenant." Respondent 4 confirmed, "We are seeing affordability challenges and unsuccessful applications based on poor credit history and bad references." In terms of income levels, there was a consensus that lower-income earners are not catered for in the area under study. Respondent 1 had this to say concerning the income levels of their would-be tenants, "Due to the fears we have that tenants will be unable to pay well and consistently, we have resorted to having a credit check as well as a salary check to see in which bracket the applicant falls. If the applicant earns below the poverty datum line, then they do not qualify for rental." In this regard, estate agents use a 'Tenant Profile' to both assess and screen applicants. This is a rigorous screening process that entails credit and income checking, which favours higher earners. Emerging segments of the rental market, those who were disadvantaged under apartheid, are the least likely to meet the stringent criteria (they are especially unlikely to have a long credit history, for example) and, thus, may be excluded from the rental market.

While there is a disincentive for agents to rent to perceived 'risky' tenants, there is also a mismatch in the market where some types of properties are in over supply. This is contradictory to the literature that points to huge demand for rental property in the global south (Echeverry 2007). Within the rental market in Johannesburg there is a glut of some rental unit types, such as two-bedroomed rental units. Respondent 2 said, "The market is oversupplied, that's the biggest challenge ... there is low demand for two bedroomed units". Respondent 1 stated, "The most challenging thing above rental cost is a flooded market." Respondent 2 noted: "There are some areas that are actually overpriced, the most interesting fact is that landlords have a ridiculous expectation in terms of rentals; we have to price-educate them." This was a third theme, namely that landlord expectations are not in sync with market trends. Landlords wanted rental income directly aligned to property valuations, instead of prevailing rental market trends. Thus, there is a gap between what landlords expect and what the market will or can pay. The respondents felt this was a major challenge. Respondent I said, "It shows in the current market, when I advertise rentals at R9 500, people will come back with offers between R8 500 and R9 000. The landlords are greedy." Respondent 10 supported this, saying, "Basically to convince landlords of current market conditions and that unless they take a certain rental, sometimes lower than expectations, they will not get tenants as affordability is a problem. The challenge is getting landlords to accept what the market can pay." Landlords expecting more causes vacancy rates to rise. In addition, respondents felt that not all landlords maintain their properties. Thus, some landlords lost good tenants, either though not maintaining the property or by demanding unrealistic rental escalations. Respondent 9 stated that: "Landlords want to increase at 7% or 8%. I feel the increase should be fixed at 6.5%. I think the rental amount and escalation must be controlled. If the escalation is at 10%, by the time five years is over that tenant will find a new development at half the price." Landlords fail to recognise that they face competition in the form of new property developments, where tenants may find cheaper accommodation (although these are most likely to be located on the periphery). While this shows that there is scope for new entrants into the market, the unwillingness of owners to drop their rent does indicate a potential short-term barrier to entry.

Government legislation has also had a bearing on the rental market. The PIE Act (Prevention of Illegal Eviction from and Unlawful Occupation of Land. Act No 19 of 1998) is a hindrance to rental housing provision. Some respondents felt that this act was financially detrimental to landlords and estate agents, as the act had unintended consequences such as enabling tenants to occupy a property without paying rent. Respondent 7 said, "A lot still needs to be changed in terms of policies. In most cases the policies favour the tenant. Tenants can stay six months not paying and you cannot evict them ... this must change." Respondent 10 said, "Laws protect tenants more than landlords. The Rental Housing Act is good. But the PIE act allows tenants to squat. Tenants are becoming more aware of it (and so exploit it)." Respondent 2 said, "The laws are very much biased towards tenants, especially when it comes to evictions."The respondents also said some tenants vandalise the rental property or steal things when their leases expire. Respondent 9 said, "The challenge is people with bad habits and bad behaviours, this included tenants who have an excellent credit record. Behaviour is shocking." Vandalism, theft and abuse of the PIE Act were identified by most respondents as impediments to the supply of rental housing, further limiting the risk appetite of landlords.

While the exclusion of individuals through financial criteria and low risk appetites have limited the number of rental units available to emerging middle class tenants, there is growing demand for rental stock in desirable suburbs close to amenities. The proximity to work, school, transport routes and shopping malls were crucial factors influencing where tenants want to live. Most of the respondents were of the view that tenants chose accommodation based on where their children went to school or where they worked, followed by proximity to amenities. Other issues, in order of importance, were (l) access to transport routes, (2) how secure the unit was, and, lastly (3) the quality of the unit. Respondent 2 noted: "Generally people want to be near a school as well as workplace." Respondent 8 reiterated, "For tenants with children; school is the priority. They look for the school first and the property choice is driven by that." Respondent 4 said that in her experience tenants look for locations near work, schools, amenities and transport routes: "Location is key in terms of characteristics - close to place of work, schools for children, shopping centres and mobility in terms of transport routes." Respondent 1 added, "Few were afforded the opportunity to be discerning about the condition of the property they are getting, security, etcetera." Nevertheless, the condition of the home, configuration and size of residential unit did influence some tenants, as Respondent 6 noted, "There were instances where I would have over 15 applicants on a rental unit in Linden but the physical set-up of the complex was not favourable. As such it is important to ensure that physically the place is conducive." The study found that the type and quantity of other houses around the unit on offer, the drainage system, refuse disposal system, electricity, water supply, security and socio-cultural background of the people living in the area also matter to tenants. Security remains a critical factor in South Africa. One respondent emphasised security as a key determining factor for tenants.

The quality of the suburbs, the level of amenities in the area and location means the suburbs covered by the case study are in high demand. To an extent, legislation and a weak economy makes it a tenant's market. That is, the general view was government policies favour the tenant. Noteworthy is the contribution of Respondent 2: "The government needs to look at the way they crafted the laws so that they balance between the lessor and lessee." Respondent 3 agreed, saying: "There are challenges with regards the law and (lack of) protection of landlords ... there is too much protection of the tenant." Additionally, affordable housing processes were overly bureaucratic, resulting in a glacial pace of response. Respondent 5 felt that, "There are a number of subsidy programmes through the Social Housing Regulatory Authority, but they are very bureaucratic, slow and tedious and they tend to select registered social housing providers and thus the private developers tend to avoid it."The respondents believed there was no commitment or support from government for private developers and landlords in terms of policy and legislative frameworks.

Discussion

The suburbs under study represent sought-after locations, close to jobs, schools and many services and amenities, thus meeting many of the needs of the middle income market: accessibility to place of work, schools, shops, transport nodes and quality of housing. That said, security was a critical factor, with most tenants concerned about security issues. In general, there was strong demand for rental property in these suburbs, though there was a strong association between income and the ability to secure rental accommodation. Thus, a lack of affordability is a characteristic of the Johannesburg private rental housing market in the suburbs under study, with many of the rental units beyond the reach even of middle-income tenants. Oddly, there is a simultaneous shortage of affordable housing and a surplus of unaffordable housing. Part of the problem is that landlords' rental expectations were too high, with demands for unattainable 10 percent annual increases. This problem is such that estate agents hold special sessions to educate the landlords on pricing. The problem may lie in the switch of rental housing from accommodation provision to being that of an 'asset class', where landlords have invested in the buy-to-let or build-to-let market and are expecting specific returns on their investments or need them to cover their bond and municipal rates and taxes (Aalbers 2019; Todes and Robinson 2019).

But this structural mismatch may also be related to restrictive legislation concerning landlords, namely the PIE Act, an act that affords tenants extraordinary protection from eviction. Due to high levels of eviction and exploitation under apartheid, the PIE act is strongly in favour of the tenant in housing disputes, placing the burden on the landlord to prove non-compliance. In particular, the PIE Act makes the eviction of a tenant difficult and costly. But some tenants abuse this by not paying their rent. Although evictions can eventually be secured, usually landlords are considerably out of pocket for both rental and eviction costs. Furthermore, bad behaviour, theft and vandalism also deter landlords from signing up tenants. Some landlords even take their property off the rental market. Challenges like these lead to landlord fatigue, resulting in prospective tenants being subjected to heavy screening. Sometimes landlords are so concerned about the legal consequences of the PIE Act that they would rather exclude tenants deemed 'too risky' and leave their units vacant. It seems the PIE Act is partially hindering the access of emerging middle class tenants to these desirable suburbs. Thus, in terms of government policy, for the respondents, the legislative framework has been a serious inhibitor of the private rental market. Respondents felt insufficient attention has been paid by South African lawmakers to the needs of the rental market. This focus on income, and other critical measures such as cre dit checks, could limit who is able to access the rental space; landlords use these checks to screen out tenants who might be more unstable in paying. However, the history of South Africa means people of colour are among those who are most likely to have an unstable income. Under apartheid the suburbs under study were classified as 'white', and, while the post-apartheid government scrapped all apartheid spatial legislation, they still have a very high proportion of white people. Thus, onerous credit checks could result in exclusion tactics to limit the access of the emerging black middle class to these areas. In that regard, respondents felt that the provisions of the NCA exacerbated the problem as only those who earned three times the monthly rent could qualify as tenants. Thus, although the NCA was designed to protect consumers from exploitation by credit providers, it may be disadvantaging tenants who have patchy credit records, who do not have large deposits on hand, or who are prepared to pay more than one third of their income in rent in order to secure a property that is in a desirable location and can potentially reduce their monthly transport costs. It is highly likely that such demands handicap previously disadvantaged people of colour, as well as immigrants, who may not have credit records, collateral or the guarantee required to secure a lease, for example.

The result is a shortage of affordable rental accommodation, in part due to legislation that places too much risk on the landlord. However, bad tenants also cause landlords to be hesitant to let their property without substantial deposits and credit checks. Furthermore, overpriced accommodation is also a problem. While the demand for rental housing in desirable locations by the emerging middle class is significant, both legislation and affordability have become the barriers that exclude individuals. As a result, structural exclusion from resources, such as affordable housing, may be entrenching intergenerational inequality (see Nattrass and Seekings 2001; Seekings and Nattrass 2002; Bond 2003, 2004; Louw 2004). There may be scope for rental subsidies, which could enable households to better access rental housing in the areas under study. Another principal finding is that the policy framework does not adequately protect either the tenant or the landlord. Weak policy and poorly crafted legislation can result in financial losses for the landlord. At the same time, tenants encounter difficulties in accessing rental housing due to high rents, tedious application processes, onerous credit checks, deposits of three months rent, demands that tenants maintain properties and other vetting processes. Individuals, who under apartheid were excluded from residing in these desirable suburbs due to their race, are now being excluded by restrictive legislation and high costs. Thus, class segregation could be replacing race segregation in these suburbs.

Conclusion

Although there is a great need for affordable middle income rental housing in Johannesburg, the state is mostly focused on promoting home ownership for very low to low income groups. Therefore, we suggest a collaborative effort between the private sector and government could improve the efficiency of the private rental market in Johannesburg. However, this will need to go together with provisions to grow investor confidence by protecting investors/landlords and tenants. Currently, it appears that class-based forms of exclusion are inhibiting the central suburbs of Johannesburg from becoming inclusive. That is, legislation designed to protect the eviction of vulnerable people is placing unintended exclusionary pressures on new entrants who wish to access desirable suburban spaces. Where once race-based legislation excluded people, now financial exclusion, alongside legislation not truly 'fit-for-purpose' and landlord risk aversion, may be limiting who can access middle income rental homes. Thus, regulatory and fiscal support is required to create an enabling environment for viable and sustainable market-based solutions for the supply of rental accommodation. This includes fine-tuning the National Credit Act, which may be preventing people with legitimate, yet non-regular, sources of income, or credit records deemed 'inadequate', from accessing rental units; it may also be pushing up rental costs. In addition, the state, through relevant multi-stakeholder consultations, needs to review the PIE Act to balance the needs of business, investors and tenants in the buy-to-let market. That is, legislation designed to protect the eviction of vulnerable people, is placing unintended exclusionary pressures on new rental accommodation entrants.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the respondents who participated in the study, especially Joy Tupholme for clarifying tenancy issues with us and assisting us to gain access to these estate agents. Thanks to Wendy Job and Ingrid Booysen for the cartographic material.

Dedication

This paper is dedicated to the late Dr Ian James McKay, paleontologist, science educator, mentor, supervisor, husband and dedicated father. A bright star of the University of Witwatersrand Evolutionary Studies Institute (ESI) left us too soon. Enjoy traveling through time Ian!

References

Aalbers MB. 2019. Financial geography II: Financial geographies of housing and real estate. Progress in Human Geography 43(2): 376-387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518819503 [ Links ]

Ahmad S. 2015. Housing poverty and inequality in Urban India. In: A Heshmati, E Maasoumi and G Wan (eds). Poverty Reduction Policies and Practices in Developing Asia. Springer: Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-420-7_6 [ Links ]

Autor D, Palmer C and Pathak P. 2014. Housing Market Spillovers: evidence from the end of rent control in Cambridge MA. Journal of Political Economy 122(3): 661-717. https://doi.org/10.1086/675536 [ Links ]

Badger E. 2016. The next big fight over housing could happen, literally, in your back yard. Washington Post. 7 August: 4. [ Links ]

Beall J. 2002. Living in the present, investing in the future - household security among the urban poor. In: C Rakodi and T Lloyd-Jones (eds). Urban livelihoods: a people-centred approach to reducing poverty. London: Earthscan. [ Links ]

Bond P. 2003. The degeneration of urban policy after apartheid. In: Harrison P, Huchzermeyer M and Mayekiso M (eds). Confronting fragmentation: housing and urban development in a democratising society. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press. [ Links ]

Bond P. 2004. From racial to class apartheid: South Africa's frustrating decade of freedom. Monthly Review 55(10). Available at: www.monthlyreview.org/0304bond.htm. [Accessed on 8 October 2019]. https://doi.org/10.14452/MR-055-10-2004-03_3 [ Links ]

Businesstech 2019. This is the average salary in South Africa right now. Businesstech. 26 September. Available at: https://businesstech.co.za/news/finance/343191/this-is-the-average-salary-in-south-africa-right-now-2/ [Accessed on 7 October 2019]. [ Links ]

Crankshaw O. 2022. Urban inequality: theory, evidence and method in Johannesburg. United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350237032 [ Links ]

De Stadler E. n.d. Lease and the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008: let's set the record straight. Esselaar Attorneys. Available at: http://www.esselaar.co.za/legal-articles/lease-and-consumer-protection-act-68-2008-lets-set-record-straight [Accessed on 7 April 2021]. [ Links ]

Desmond M. 2015. Evicted: poverty and profit in the American city. New York: Crown Publishers. [ Links ]

Echeverry D, Majana E and Acevedo F. 2007. Affordable housing in Latin America: improved role of the academic sector in the case of Colombia. Journal of Construction Engineering Management 133(9): 609-722. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(2007)133:9(684) [ Links ]

Forrest R. 2011. Globalization and the housing asset rich geographies, demographies and policy convoys. Global Social Policy. 8(2): 167-187. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468018108090637 [ Links ]

Gerxhani K. 2004. The informal sector in developed and less developed countries: a literature survey. Public choice 120(3-4): 267-300. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:PUCH.0000044287.88147.5e [ Links ]

Gilbert A. 2011. Ten myths undermining Latin American housing policy. Revista de Ingeniería, (35): 79-87. https://doi.org/10.16924/revinge.35.12 [ Links ]

Gilbert A. 2014. Housing the urban poor. In: Desai V and Potter RB (eds). The companion to development studies, 3rd edition. [ Links ]

Gilbert A, Mabin A, McCarthy M and Watson V. 1997. Low-income rental housing: are South African cities different? Environment and Urbanization 9(1): 133-148. https://doi.org/10.1177/095624789700900111 [ Links ]

Gopalan K and Venkataraman M. 2015. Affordable housing: policy and practice in India. IIMB Management Review 27(2): 129-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iimb.2015.03.003 [ Links ]

Gunter A. 2014. Renting shacks: landlords and tenants in the informal housing sector in Johannesburg South Africa. Urbani izziv 25: S96-S107. https://doi.org/10.5379/urbani-izziv-en-2014-25-supplement-007 [ Links ]

Gunter A. 2013. Creating co-sovereigns through the provision of low cost housing: the case of Johannesburg, South Africa. Habitat International 39: 278-283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2012.10.015 [ Links ]

Gunter A and Manuel K. 2016. A role for housing in development: using housing as a catalyst for development in South Africa. Local Economy 31(1-2): 312-321. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094215624352 [ Links ]

Gunter A and Massey R. 2017. Renting shacks: tenancy in the informal housing sector of the Gauteng Province, South Africa. Bulletin of Geography. Socioeconomic Series 37: 25-34. https://doi.org/10.1515/bog-2017-0022 [ Links ]

Haupt F, Roestoff M and Renke S. 2007. The National Credit Act: new parameters for the granting of credit in South Africa. Obiter 28(2): 229-270. [ Links ]

Housing Development Agency (HAD). 2012. Gauteng: informal settlement status. Johannesburg: HAD Publishing. [ Links ]

Iwata S and Yamaga H. 2008. Rental externality, tenure security, and housing quality. Journal of Housing Economics17(3): 201-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2008.06.002 [ Links ]

Lee L. 2009. "Housing price volatility and its determinants", International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis 2(3): 293-308. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538270910977572. [ Links ]

Legwaila T. 2001. An introduction to the Rental Housing Act 50 of 1999. Stellenbosch Law Review. 12: 277. [ Links ]

Leibbrandt M, Woolard I, Finn A and Argent J. 2010. Trends in South African income distribution and poverty since the fall of apartheid. OECD social, employment and migration working papers, No. 101. OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/5kmms0t7p1ms-en. [ Links ]

Louw P. 2004. The rise, fall and legacy of apartheid. USA: Praeger. [ Links ]

Mafukidze K and Hoosen F. 2009. Housing shortages in South Africa: a discussion of the after-effects of community participation in housing provision in Diepkloof. Urban Forum 20: 379-396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-009-9068-7 [ Links ]

Marais L, Cloete J, Matebesi Z, Sigenu K and Van Rooyen D. 2010. Low-cost housing policy in practice in arid and semi-arid South Africa. Journal of Arid Environments 74: 1340-1344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.03.010 [ Links ]

Massey R. 2013. Competing rationalities and informal settlement upgrading in Cape Town, South Africa: a recipe for failure. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 28(4): 605-613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-013-9346-5 [ Links ]

McKay TJM. 2015. Schooling, the underclass and intergenerational mobility: a dual education system dilemma. Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa 11(1): 98-112. https://doi.org/10.4102/td.v11i1.34 [ Links ]

McKay T: 2020: South Africa's key urban transport challenges. In: Gunter A and Massey R (eds). Urban geography in South Africa - perspectives and theory. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25369-1_12 [ Links ]

McKay T, Simpson Z and Patel N. 2017. Spatial politics and infrastructure development: analysis of historical transportation data in Gauteng (1975 - 2003) Miscellanea Geographica: Regional Studies on Development 21(1): 35-43. https://doi.org/10.1515/mgrsd-2017-0003 [ Links ]

Morton T. 1998. A profile of urban poverty in post-apartheid Hillbrow: comparing South African and American inner cities. Unpublished MA thesis.Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Moss V. 2003. Understanding the reasons to the causes of defaults in the social housing Sector of South Africa. Housing Finance International 18(1): 20-26. [ Links ]

Mulliner E and Maliene V. 2013. Austerity and reform to affordable housing policy. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 28(2): 397-407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-012-9305-6 [ Links ]

Nattrass N and Seekings J. 2001. "Two nations"? Race and economic inequality in South Africa today. Daedalus 130(1): 45-70. [ Links ]

Obeng-Odoom F and Amedzro L. 2011. Inadequate housing in Ghana. Urban! Izziv 22(1): 127-137. https://doi.org/10.5379/urbani-izziv-en-2011-22-01-004 [ Links ]

Ram P and Needham B. 2016. The provision of affordable housing in India: are commercial developers interested? Habitat International 55: 100-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.03.002 [ Links ]

Rapelang T. 2014. An evaluation of the right to "Access to adequate housing" in Joe Morolong Local Municipality, South Africa. Unpublished MA Thesis. Bloemfontein: University of Free State. [ Links ]

Rex R, Campbell M and Visser G. 2014. The on-going desegregation of residential property ownership in South Africa: the case of Bloemfontein. Urban! Izziv 25: 5-25. https://doi.org/10.5379/urbani-izziv-en-2014-25-supplement-001 [ Links ]

Ronald R and Doling J. 2010. Shifting East Asian approaches to home ownership and the housing welfare pillar. International Journal of Housing Policy 10(3): 233-254. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2010.506740 [ Links ]

Roux LM. 2013. Land registration use: sales in a state-subsidised housing estate in South Africa. PhD Thesis. Calgary: University of Calgary. [ Links ]

Rust K. 2006. Analysis of South Africa's housing sector performance. Johannesburg: FinMark Trust. [ Links ]

Sabal J 2005. The determinants of housing prices: the case of Spain. Available at: http://www.sabalonline.com/website/uploads/RE5:pdf [accessed on 13 July 2017]. [ Links ]

Scheba A and Turok I. 2020. Informal rental housing in the South: dynamic but neglected. Environment and Urbanization 32(1): 109-132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247819895958 [ Links ]

Seekings J and Nattrass N. 2002. Class, distribution and redistribution in post-apartheid South Africa, Transformation 50: 1-30. https://doi.org/10.1353/trn.2003.0014 [ Links ]

South African Local Government Association (SALGA). 2011. Toolkit developing a municipal social housing policy. Available at: https://www.salga.org.za/Municipalities%20F%20MGOSARH.html [accessed on 23 September 2019. [ Links ])

Shrestha BK. 2010. Housing provision in the Kathmandu Valley: public agency and private sector initiation. Urbani Izziv 21(2): 85-95. https://doi.org/10.5379/urbani-izziv-en-2010-21-02-002 [ Links ]

StatsSA. 2012. Census 2011 Municipal fact sheet. Available at: www.statssa.co.za [accessed on 15 September 2017]. [ Links ]

Strauss M and Liebenberg S. 2014. Contested spaces: housing rights and evictions law in post-apartheid South Africa. Planning Theory 13(4): 428-448. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095214525150 [ Links ]

Tissington K. 2011. A resource guide to housing in South Africa 1994-2010: legislation, policy, programmes and practice. Available at: http://www.serisa.org/images/stories/SERIHousing_Resources_Guide_Feb11.pdf [accessed on 17 June 2017]. [ Links ]

Todes A. 2012. Urban growth and strategic spatial planning in Johannesburg, South Africa. Cities 29(3): 158-165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2011.08.004 [ Links ]

Todes A and Robinson J. 2019. Re-directing developers: new models of rental housing development to re-shape the post-apartheid city? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 0308518X19871069. [ Links ]

Tupholme, Joy. 2018. Real estate broker for Office Space Online, personal communication 8 August 2018. [ Links ]

Watson V and McCarthy M. 1998. Rental housing policy and the role of the household rental sector: evidence from South Africa. Cape Town: University of Cape Town. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-3975(97)00023-4 [ Links ]

Watson V. 2011. Changing planning law in Africa: an introduction to the issue. Urban Forum 22(3): 203-219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-011-9118-9 [ Links ]

Zille H. 2017. Helen Zille responds to Sheila Madikane's open letter. GroundUp. 22 May. Available at: https://www.groundup.org.za/article/helen-zille-responds-sheila-madikane/ [accessed on 1 March 2022]. [ Links ]

Zizzamia R, Schotte S and Leibbrandt M. 2019. Snakes and ladders and loaded dice: poverty dynamics and inequality in South Africa between 2008-2017. [ Links ]

WIDER Working Paper 2019/25. United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research. Available at: https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/Publications/Working-paper/PDF/wp-2019-25.pdf [accessed on 7 October 2019). https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2019/659-3 [ Links ]

First submission: 3 May 2021

Acceptance: 5 April 2022

Published: 31 July 2022

1 http://cityfutures.co.za/sites/default/files/SA%20City%20Future%20-%20Rosebank%20dashboard.pdf Accessed 9 October 2019.

2 https://census2011.adrianfrith.com/place/798015091 Accessed on 9 October 2019.

3 https://census2011.adrianfrith.com/place/798016055 Accessed on 9 October 2019.

4 http://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=4286&id=11307 Accessed on 9 October 2019.

5 https://census2011.adrianfrith.com/place/798 Accessed on 9 October 2019.

Appendix 1: Interview Schedule

1. In your opinion (as an estate agent) are rentals in your area affordable? Please elaborate.

2. What challenges do you as an estate agent face in terms of renting out properties?

3. To what extent is rental accommodation demand driven by people needing/ wishing to be located close to their place of work?

4. To what extent is rental accommodation demand driven by people needing/ wishing to be located near to their children's school?

5. To what extent is does the transport network (access to major roads, taxi ranks etc) drive demand for rental accommodation in your area?

6. In your opinion, how could government policies pertaining to rental housing be changed/improved?

7. What recommendations can you make to about how tenants should be protected and managed?

8. What recommendations can you make about how landlords can be protected and managed, especially in terms of managing rentals as an investment/ income generating strategy?