Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Academica

On-line version ISSN 2415-0479

Print version ISSN 0587-2405

Acta acad. (Bloemfontein, Online) vol.51 n.2 Bloemfontein 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150479/aa51i2.4

ARTICLES

Re-framing the gallery: South African exhibition spaces as case studies

Wanda Odendaal (née Verster)

Department of the Built Environment: Faculty of Engineering, Built Environmnent and Information Technology, Central University of Technology, Free State; Email: wodendaal@cut.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In South Africa, both the public art museum and commercial art gallery, as distinct spatial building types, have a level of framed separation from the urban context. By drawing general comparisons between local examples, and a direct comparison with two commercial galleries as case studies, I argue that it may be valuable to re-frame the place of the art gallery and the image of the gallery within the city. I propose a contextual reading of galleries as significant material sites in the contemporary urban landscape. This paper explores the thresholds between exhibition space and city, depiction and reality and interior and exterior space. Edward Casey's definition of boundary as pliable and porous, as distinct from the restrictive edge of a border, establishes a basis for the theoretical investigation. Both these definitions require consideration when viewing urban thresholds related to museum and gallery interventions. I refer to Werner Wolf and Joan Ramon Resina and the terms frame and framing as a conceptual tool to clarify the role of the building as a framing device and image in the city. This article builds on previous published research (2014, 2016, 2018) and aims to address the subtle border between an art institution and its immediate urban environment, and the relevance of architecture in this act of situating and framing.

The interactions with the urban environment if it is viewed as a gallery and buildings as architectural works within it extends this aim.

Keywords: gallery, threshold, framing, South Africa, architecture

Introduction

The act of framing a picture or a work of art can be read in various ways. The meaning of the word itself has widespread use in diverse disciplines, and the interpretations may vary widely. The frame could function as described by Wolf (2006: 5) as "culturally formed metaconcepts" and "basic orientational aids", that enable the interpretation of specific artefacts, but also as reality and aspects linked to "perception, experience and communication". As a physical element in visual art, the frame acts as one aspect among many that influences the interpretation of the work. Wolf (2006: 5) sees interpretative frames as similar to the frames in visual art, frames "help to select (or construct) phenomena as forming a meaningful whole and therefore create coherent areas in our mental maps".

An image or work of art can gain added significance or may be read in a different context due to its physical frame, and this physical frame can itself be a reference to the perceptions, ideologies and interpretation of a specific context. In other instances, thus, the frame could represent institutions, ideologies or narratives that may also change the associated meaning of the particular work.

Of course, works themselves can also challenge their frames, in all the various forms, from the physical to the ideological. If we extend the metaphor to buildings, art museums and art galleries are not only means of framing artworks, but they also embody the image of the public art museum, or the private gallery, as institutions for the display of art. This image, in turn, is framed by its context in a certain area of a city. The context or environment is also then in turn framed and re-framed by the object, or in this case the building, placed within it.

This article focuses on the architectural work or artefact (comparable to an artwork) of the private commercial art gallery building, specifically in South Africa; it builds on previous work (Verster 2014) linked to South African art spaces. The borders and boundaries between the building, institution and its environment are linked to the relevant design, its siting and its context. The definitions of border and boundary are based on Casey's, where a boundary is porous and a border is distinct. This paper explores these relationships by referencing public art museums to engage with the exhibition space in its private and public form. The proposition is that cities frame art galleries in the same way that art galleries frame the artworks in their interiors. The gallery building may play a part in creating a profile of a city as cultured, while also engaging with its unique site-specific environment.

The focus is the comparison of two specific case studies of privately-owned commercial exhibition spaces. Circa (a component of the Everard Read Gallery) in Johannesburg is compared and analysed in contrast to Gallery on Leviseur in Bloemfontein. The comparison is viewed through the lens of Edward Casey's (2008, 2017) definitions of border and boundary, but also those of Bernard Cache (1995) and Werner Wolf (2006). The methodology of Till Boettger (2014) is useful to refine the comparison of threshold spaces. This is a focused analysis based on the architectural and spatial meanings associated with framing, edges, boundaries and the threshold rather than a broader examination of the ideological positioning of these galleries.

I argue that the gallery as a building in the urban landscape may play an important part in profiling cities as cultured destinations to national but also international audiences. It can fulfil this role by simultaneously staging a site-specific public quality, centred in the local context, and by becoming a striking sculptural presence linked to the international stage.

The gallery as an iconic work in South African cities has not reached the level of international recognition, as in the case of the Guggenheim museums globally, but on a local level may perform a role that is relatively similar and more contextually sensitive. More importantly, the complexity and cultural diversity of South African art contexts require distinct interactions with the frame and edge of the building, the space of exhibition and the city as 'container' for these relationships. The art gallery in South Africa is a shifting and movable frame that through interpretation and engagement has changed its role in relation to artists and their work. However, the complexity of the historic narrative and the inertia of the aesthetic image of the architectural work needs to be read sensitively. The act of exclusion and inclusion in South Africa carries so much weight that art institutions are included in this narrative.

The specific urban context associated with a particular exhibition space acts as a conceptual and physical frame. Casey (2004: 146) suggests why the understanding of edges is necessary when artworks, their frames and settings are analysed:

Understanding edges in their inherent bivalency allows us to appreciate more fully certain features of artworks. One of thesefeatures is the frame that acts as an edge for every work of art. Not only the outer frame that surrounds a given painting and serves to separate it from the wall, or the proscenium that comes between a theatrical production and its listeners, but the many sorts of inner frames found in artworks with a certain complexity of composition.

The complexity of composition, as a type of framing, that Casey mentions here may be extended to also describe the building as exhibition space and the immediate context of the city. The interior spaces of an exhibition space form framing instances, as does the contextual position of the architectural work within the city. The composition of the architecture introduces thresholds between spaces, experiences and interpretation.

A threshold may be read as a physical space that functions as a spatial mediator, like a door or portico for example, which ranges between open and closed and has an intrinsic ambiguity (Boettger 2014: 13). The ambiguity of the transitional space is echoed by Casey's (2008: 6) definition of the boundary as an element that does not call for linear representation, and that has a quality of porosity, that allows for physical movement, but also the flow of ideas and interpretations. To read the case study examples in light of these terms, a brief overview of the threshold as a conceptual term and the architectural typology of art spaces follows.

The threshold in exhibition spaces

Casey's (2007: 508) definition of boundary, as distinct from the border, provides an entrance into the reading the gallery as an artefact that contains the inherent duality of frames as edges. Casey defines boundary as pliable, porous and allowing two-way transmission versus the restrictive edge or separating agent of a border. Additionally, Bernard Leupen (2002: 3) also reads buildings as layers that form the defining whole. The layers are also read in his view as separate and unique frames with varying functions and again supports what Wolf (2006: 30) describes as the bridging role of frames.

When these views are compared to the embodied reaction a viewer has to a specific work, the dialogue that exists between viewer and artwork can then be seen as a form of boundary (Esrock 2010; Pallasmaa 2011). Often in urban spaces, borders are established through physical elements, but also through implied edges. The art gallery as a separated building is removed from the urban fabric and bordered (in terms of Casey's definition) by its physical characteristics, such as parks or street edges. But it is also framed as the implied place of the art, the elite institution, to which only some may gain access (whether or not physical barriers are limiting this access).

Casey (2008: 2) describes the importance of edges and the in-between spaces in painting, but the concept can be broadened to include urban interventions:

So we are here in-between two sorts of edge, mental and visual - and not just between two (or more) physical edges, as we tend all too reductively to think. ... This shows in turn that, first, edges themselves come in a plurality of types; second, that the between itself is not univocal but is very much a function of the edges that we negotiate in painting - and doubtless in other areas of life. In short, when we are in the midst of any activity, we are in-between edges.

The plurality of types of edges may be extended to types of frames. The various types of framing and attempts made in establishing edges are aimed at guiding and enabling interpenetration. Frames, in the cognitive sense, have a certain stability, even if modified and if new frames are introduced. These frames can be seen as culturally formed meta-concepts that enable the interpretation of reality, artefacts and other experiences related to communication and in so doing act as orientation points, route markers on the roads of the experiential environment (Wolf and Bernhart 2006: 3-5; Casey 2008: 2).

The relationship between the framed image and its expanding boundary can further be compared to the expanding metropolis and the problems associated with urban sprawl. Previously, cities could be measured by pedestrians and viewed as a total entity, as depicted by the veduta when the artist moved outside the urban limits. The expanding metropolis has transcended these conceptual frames, the inclusive images of the 19th century are no longer available (Resina 2003: 5), and it would be impossible for a pedestrian to navigate a city such as London or Johannesburg in its entirety. In this expanding context, the art gallery (public or private) paradoxically becomes an artefact and image to conceptually 'contain' the image of the city.

Public art museums

As architectural spaces, public art museums, and to some degree, commercial gallery typologies have been primarily based on earlier temple and palace types. The art museum typology evolved in the West in the 19th century when buildings were developed for the authoritative canonisation of a national cultural heritage. This is preceded by a development of earlier types of exhibition spaces, usually of a more private nature. The development of the art museum as a canonisation of heritage was done by collecting, exhibiting and studying various kinds of artworks (Brawne 1965: 8), as well as by developing an imposing building design. From its inception, the art museum becomes a framed object within its city - the 19th-century museum type is a typical reminder of how the art object, and museum as an institution, were viewed then: "...the art museum removes work of art from their context and strip them of their original or religious function. When presented in a museum, art is reduced more to a specific function as art." (Langfeld 2018: 5) Although private commercial galleries have a different function and mandate and do not house permanent collections, they are in many ways closely linked to the art museum as a specific architectural type and design model and do have similar effects on the works they display and sell.

The public art museum may be compared to a cathedral or temple typology, but may also be linked to the modernisation of urban space, especially concerning movement and the changing gaze of the pedestrian. It is simultaneously a symbol of art as institution, by being itself a designed (sometimes even sculptural) object, but also the spatial background and frame for artworks. Peri Bader (2018: 1) describes the complexity inherent in a display space such as the art museum in the city: "This tension between the image of a 'temple of human culture' and its architectural and functional complexity is a fascinating feature of this particular architectural creation, regardless of its type or content."

The contemporary art gallery is linked to the typological development of display spaces like art museums, cinemas and shopping centres and the spatial quality of these buildings have a complexity based on the development of spaces for the act of viewing. The private commercial gallery may play a similar role in the city as a cultural node. Peri Bader (2018: 2) describes ".the way in which the museum is perceived in the city as a place and an unusual experience (festive, monumental, and sometimes even alien or estranged), along with its organic presence as an immanent part of everyday urban life."

Contemporary private galleries are continuing to develop a certain image, both as commercial properties, but also as sculptural objects in the city, remaining linked to the public art museum.

Due to the perceived importance of the art museum, the building historically gained the connotation of being a personal, national or civic palace, and one would expect these buildings to embody the superior qualities expected of palatial settings (Verster 2018: 172). Moreover, these monumental buildings do not simply fade into the urban fabric (Brawne 1965: 8). Instead, as is the case with other palaces or temples, the separation from the immediate context is almost a necessity to establish the hierarchical importance of the building (Verster 2018: 172). Security, as an argument linked to keeping valuable works safe, also adds to the justification of adding additional thresholds, such as gates, fences and paid access. These additions may further underscore the hierarchical importance of a building.

This is not to say that museums and galleries, as institutions, do not engage the public. There are a huge variety of programmes aimed at engaging with the public, from the physical to the virtual. The typological language, the urban context of a gallery or public art museum and its relationship, along with security concerns, may, however, detract from the engagement sought through such institutional programmes.

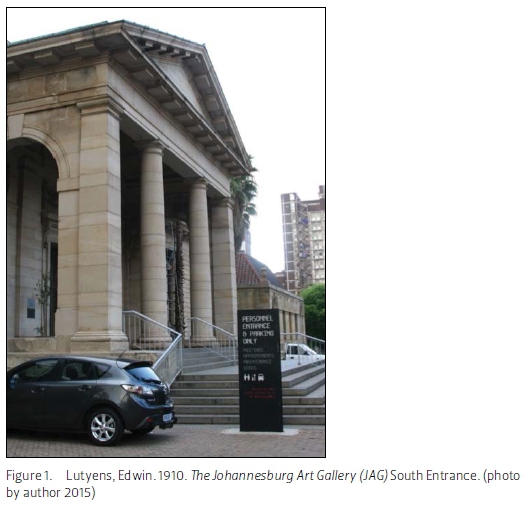

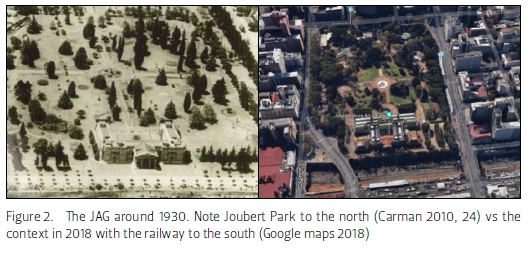

The hierarchical palatial typology is ubiquitous internationally; the British Museum in London is a typical example, and locally in South Africa, the Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG) (as a public art museum) easily fits within this typology (Fig. 1). Designed in 1911 and finally opened in 1915, the art gallery displays the classically inspired pediment and columns that immediately make the stately, temple-like connection clear through the recognisable importance of neoclassical elements. This typical 'colonial' design by Edwin Lutyens introduces edges, boundaries, and thresholds on several levels, hierarchically separating itself from the surrounding context (Chipkin 1993: 49). Of course, the building's setting in the centre of Johannesburg adjacent to Joubert Park provides its own set of borders and edges and thus presents a duality of connection and separation from its present context (Verster 2018: 168).

This art space, founded a century ago, now inhabits a vibrant contemporary African city and has undergone a dramatic change in its context. It finds itself surrounded by an entirely different environment from when it was first built, and even from when it was later expanded in the 1940s and again in 1987 (Fig. 2). The museum thus has to reposition itself within a context that is perceived as inaccessible by some. It also has to engage with the residents of the immediate area that have not engaged with the space that is right on their doorstep (Fenn and Hobbs 2013: 5, 6).

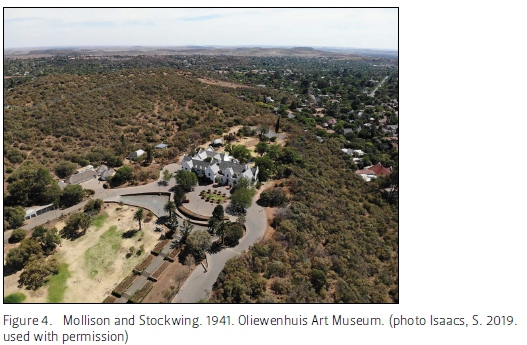

Similarly, in Bloemfontein1, the public art gallery, Oliewenhuis2, also fits the 'palatial' sense of the 19th century museum. The fact that the museum was initially designed as a presidential residence fits the ideal of the gallery as palace. Although it was only converted to its current function in the 1980s (Haasbroek 2014: 50), sitting elevated on Grant Hill overlooking the city, surrounded by gardens, and fenced in by Harry Smith Street, it can still be viewed as the same general architectural typology as the JAG. Both buildings have references to European stylistic influences (Cape Dutch and neo-classical), both have symmetrical plans and the elevations as single facades rather than experientially engaging features to invite interaction. In Bloemfontein, the surrounding roads, the adjacent park and fences act as frames, but also reflect an ideological framing which sets Oliewenhuis apart from its environment. The context is distinctly different from that of central Johannesburg. There is no informal trade in this semi-suburban area of Bloemfontein, and the surrounding sites (Oranje Meisieskool, the residence of the premier of the Free State, Happy Valley and high-end residences) mean intermittent to very few pedestrians enter Oliewenhuis from the street edge. Most visitors arrive by car and park on the premises.

Oliewenhuis is physically separated from the urban grid and is not the typical modernist white cube, but does have some of these qualities.

The art gallery generally, as venerated white box within an extended green space, has been questioned by interventions by artists such as Santiago Sierra, Gordon Matta-Clark and Robert Barry (Davidts 2006: online), as it creates an edge between the exhibition space and urban space, and in turn between the viewer and the building, and the works it contains. Not only does this suggest a separation regarding physical thresholds, but also discursively regarding the place of art in society and the access to exhibition spaces in South Africa. The site itself would seem to embody two regular characteristics of gallery spaces, i.e. the typical palatial setting, and (with the addition of the reservoir gallery3 to the north), the underground exhibition space. The Neo-Cape Dutch elements further add to these elements of a civic palace and the nationalism that is associated with it in the context of the pre-Apartheid 1940s. The permanent collection of Oliewenhuis is focused mainly on local artists and includes works by early artists such as Thomas Baines, JH Pierneef and Willem Coetzer. The collection is still expanding with the acquisition of contemporary works by local artists. In this sense, the edge between the museum and its local context is somewhat blurred when describing the institutional place of the collection in Bloemfontein and is not bordered but experienced as a boundary. The palatial typology is therefore tempered in idiosyncratic ways through the use of the gardens as a community space4. To the south of the building works of sculpture and mosaic allow for engagement and interaction.

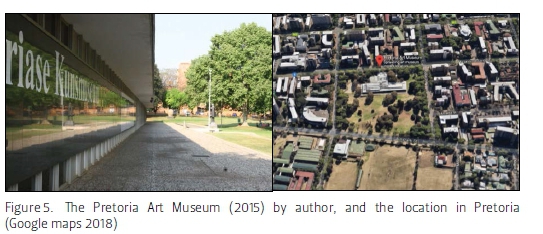

In comparison, as an icon, the Pretoria Art Museum would seem to be unique in its setting in Pretoria, by subverting the palatial typology as a modernist pavilion5. Designed by Burg Doherty Bryant and Partners in 1967, it is unassuming in its park setting and functions as a sculptural pavilion. Peri Bader (2018) and Friedberg (1993) connect the art museum to the emergence of urban modernity and the development of the gallery space to that of modern typologies such as the railway station. Peri Bader (2018: 1) reiterates the complexity of the art museum, and this may be extended to contemporary galleries, in that it contains within its architectural example the tension between the functional and the representational. The architectural type has inherent complexity but also refers to the image of the cultural temple.

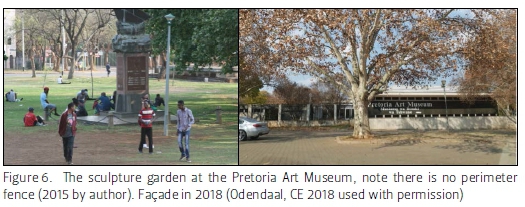

The surrounding park, however, remains a feature of the public art museums mentioned here, although not of all public art museums in South Africa. The Pretoria Art Museum has a blurred edge or a frame that allows movement, more so than the JAG or Oliewenhuis examples, where the parks and the museum itself are fenced. It is a boundary, rather than a border, according to Casey's definition, but also provides an extension of the exhibition space. This space is unique in the sense that its sculpture park remains open to the public, with no fencing to restrict access. Both JAG and Oliewenhuis do not restrict access to the sculpture gardens, but the introduction of a more definitive threshold through the use of fences and gates does play a role in the way the building is viewed. Pretoria Art Museum remains framed by the park and distanced from the remaining urban grid, but the accessibility of the park is open at many points.

"If boundaries are open to traversal at many points, borders actively discourage or refuse such traversal." (Casey 2004: 147)

The building itself has a more definitive edge; the exterior walls form a distinct border that keeps the collection hidden and preserved within its protective walls. The reflective nature of the faςade mirrors the park (Fig. 5) that puts an additional focus on the exterior rather than on the interior that houses the collection.

These galleries reframe the context of the museum, the edges between museum and city and the image of the city itself. The reframing of the museum as a place in South African cities has not been attempted on the scale of the Guggenheims internationally, but there are examples where the edges, boundaries, and thresholds have been kept in mind and have led to reframing on a micro-scale.

Framing and reframing are firstly related to the visual arts; in essence, the frame functions as an element that focuses the gaze, as described by Carter (1990: 73):

The frame is a much later development and usually acts like a window frame, enclosing and focusing the viewer's gaze onto the scene which unfolds within its boundaries. Such a device places the frame within the space of the viewer and marks the point where 'real space' ends and represented space begins.

In the same vein, the interaction of the spectator with the artwork can be extended to the gallery space in the urban context. The building can be viewed as an artwork and the city as its containing gallery. Therefore, on this level of interaction, not far removed from that between artwork and spectator, contemporary gallery design can be considered as a type of framing. Both the JAG and Oliewenhuis are framed very directly, whereas the Pretoria Art Museum's frame is slightly more subtle (Fig. 6).

In their acts of display the contemporary case study examples are not far removed from the older temple or palatial forms as a means of displaying cultural authority and power in the 19th century urban environment. During the 20thcentury, the modernist and later the contemporary architecture of the commercial world superseded this authority - hence new forms of urban engagement appear in the recent extensions of these buildings from previous eras. For example, the installation works by artists such as Urs Fischer (2007) or even Gustaf H Wolff and Giorgio Morandi (1955) are the links between the artworks in the interior museum space and the city as an exterior gallery (Maak, Klonk and Demand 2011: online).

What role does the deliberate act of drawing an edge in glass (or reflective materials such as polished granite) play within the urban environment? The discourse on museum architecture as artwork or public sculpture versus functional structures to house art, as well as the influence of commercial window display, is essential when viewing art museums and commercial galleries as a form of public sculpture. Resina (2003: 6) suggests that the way cities are viewed is linked to works of architecture:

The perceptual change does not mean simply that a previously dominant architectural image has been displaced by a more abstract aviator's view. A downward-looking, remote perspective has not taken the place of an upward-looking, more absorbed one. The mutation, rather, is that architecture has become absolute as the sole or even primary medium for visualising the city.

Architecture, as the dominating visualising element of the city, is the inevitable result of the 'starchitects' intervention. The imagined and conceptualised image of the city of Bilbao, Spain, is framed in light of Frank Gehry's design of the Guggenheim as sculpture, rather than the image of the museum being informed by the city. Perhaps in viewing the city as the gallery space and buildings as artworks, our interactions with this environment also change. In essence, crossing a mental edge, and activating the imagination, as a physical frame would (Casey 2008).

Framing acts as a metaconcept here; it allows the presumption needed to analyse a gallery or art museum as a space of legitimisation of art, but also as a space that creates thresholds but simultaneously can function as an icon of itself and a city. Wolf describes the contextual role of aesthetic works as referential artefacts but also works that challenge and create frames: "...aesthetic works (as well as their production and reception) not only refer to existing frames but ... create new, or at least more or less modified ones." (Wolf 2006: 14, emphasis in original)

The art gallery as a frame can be read as an aesthetic work in Wolf's description. His statement on how frames function as linking and mediating devices thus establishes the building as both artefact and frame.

"Framings frequently not only mark the inside/outside border between artefact and context (notably in pictorial framings and in the initial and terminal framings of temporal artefacts) but also help to interpret an artefact by creating a 'bridge' between its inside and its outside or context." (Wolf 2006: 30) The frame can be seen as a type of threshold or mediating device, and the exhibition space is thus dual-frame.

The two contemporary South African case studies serve to explore the introduction of a building which may act to reframe the artefact of the gallery space, but also engage as mediating device in the context of the city. Circa on Jellicoe in Johannesburg by StudioMAS (2009) and Gallery on Leviseur in Bloemfontein by SN architects (2013) are interventions and ways of reframing the gallery in subtle ways, with varying success. These two buildings were selected as comparable because, as small-scale designs for the express purpose of housing art, conceptually both aim to be beacons in the respective cities, in effect creating new frames of reference in the environment. The buildings also have both received recognition in the form of awards.6 The award serves as a frame that establishes the gallery space as a significant architectural artefact in the frame of their cities, an object that speaks to the image of their cities, but also as significant artefacts within the frame of the architectural profession.

Case studies

CIRCA on Jellicoe, Johannesburg, South Africa, StudioMAS, 2009

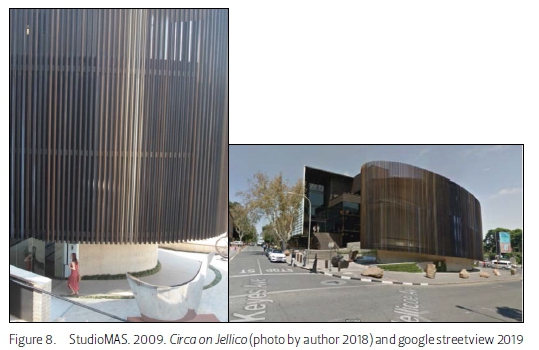

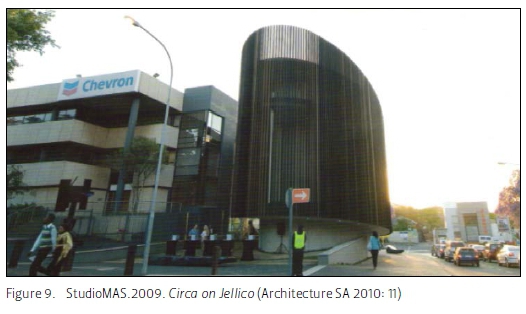

Circa on Jellicoe in Johannesburg explicitly addresses various aspects of threshold, edge, and boundary in the urban space. Designed by StudioMAS in 2009, it is described by Raman (2010: 9) as a building that encapsulates several contemporary concerns in architecture, urbanism and the housing of art. It is situated in Rosebank and now (2019) forms part of a developing Keyes Art Mile art precinct.

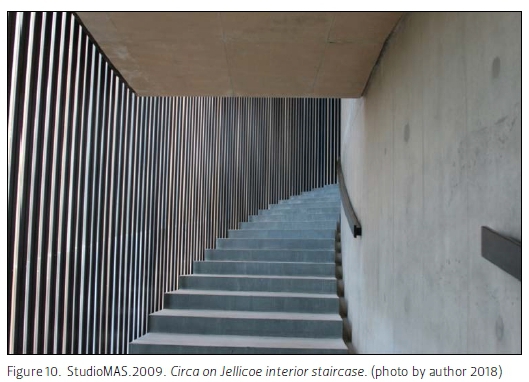

The design is a simple ellipse on plan (Fig. 7), extruded to form three levels. Circulation is handled with a ramp on the outside edge. A screen of fins clads the exterior but remains open to the elements. The main exhibition space is located on the first floor, accessible by a curved ramp from the ground floor. Additional circulation and an escape route are housed in a steel structure that acts as scaffolding for a green surface.

But the building manages to move beyond the sculptural, beyond the functional space and reframes a moment in the Johannesburg grid. This building, simply and through careful design, introduces several layers to the distinctive experience of the art gallery. It is also a sculptural piece that encapsulates the experience of the blurred edge. It activates the boundary, and it does so subtly. Boettger (2014: 13) states that "a threshold space is strongly determined not only by tension-building counterbalances but also by the sequence in which space is experienced".

This sequence of experiential space is designed with great care in this building. Although the screened ellipse is seemingly impenetrable, the reed-like faςade has a level of transparency. The building itself becomes a boundary in contrast to the established borders. On the physical level, the gallery is effective in addressing the pedestrian movement through the innovative solution to its internal circulation.

"Pedestrian movement from Jan Smuts Avenue swirls round, and the sidewalk gently becomes the entry court. From there the movement trickles into the ground-floor gallery and ascends the ramp on to the first-floor gallery." (Raman 2010: 11).

By solving the circulation in this way, it addresses both the practical concerns regarding movement but also creates a unique threshold space, not only in the physical or visual sense but in terms of a liminal experience. The fins create an edge between interior and exterior, but also allow glimpses of the exterior surroundings. In being between the two edges of the building, the screen that separates it from the city and the wall that contains the main gallery the visitor experiences the potency of the moment, both in moving through it and in imagining the interior space as one simultaneously glimpses fragments of Johannesburg. The gaze is drawn outward toward the city, not inward as in the case with Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim in New York (Raman 2010: 11). In this way, the intervention involves crossing the edge between the external world of the city and the internal world of the gallery. The most striking element of the building is the fins that screen it. The edge between public and private is also crossed through the visual interactions provided by the fins that enclose but also reveal (Fig. 9). "When read together obliquely, they form a solid surface, but when viewed face-on, they become transparent. ... but through the semi-transparent faςade rather displays the visitors to passing motorists." (Freschi 2010: 79) But it goes beyond the blurring of public and private.

Beyond the structure and the physical lines, the idea of the gallery is extended further, crossing another edge. A small piazza is created where larger sculptural works can be exhibited and where the beginning and end of the gallery proper is blurred (Freschi and Lowe 2010: 77).

The gallery in the public realm, as a separate entity, edged and contained, is in some way also questioned through the seeming permeability of the finned facade, which seems to draw pedestrians in and intrigues passing motorists. This example becomes a piece of sculpture in the museum of Johannesburg and softens the edge between the container for art and the experience of artworks. The Darwin room at the apex of the building is the setting for private functions and ironically tops the building that was described by Swanepoel (in Eicker 2009: 15) as "a new architectural landmark...[with]... the feel of an accessible community centre". The large open deck provides a view over Johannesburg; the space is accessible through the gallery but access is limited when it is being used for specific functions or meetings.

The work exhibited at Circa is by recognised and established artists and the exhibition space here is an extension of the Everard Read gallery, that sees itself as dedicated to exhibiting works by established and critically acclaimed modern and contemporary South African artists (Everard Read 2018: online).

The Free State example initially had a similar vision, but the gallery has shifted focus and with new owners has since hosted a wide variety of exhibitions, mainly focused on the work of local amateur artists. The curatorial control and access control is thus lessened and speaks to the fine line a contemporary art gallery curator or owner faces. By controlling the work exhibited, and the quality of the work, there is a necessary judgement and separation. The work of specific artists is included while amateurs, or those deemed of lesser quality, are excluded. The gallery as a framing device and space of legitimisation is linked to the role of the curator, not only the architectural space.

Gallery on Leviseur, Bloemfontein, South Africa SN Architects 2013

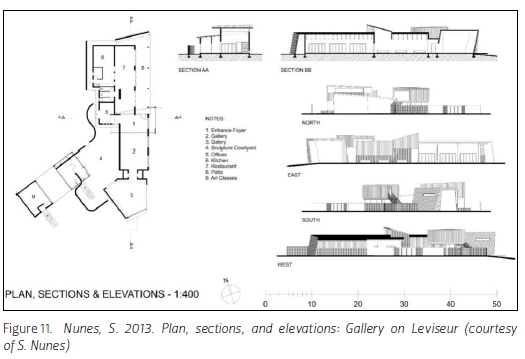

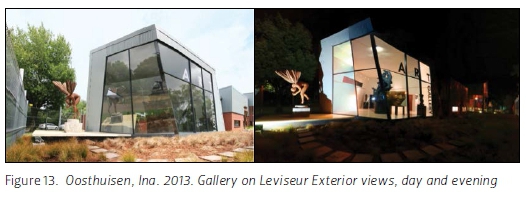

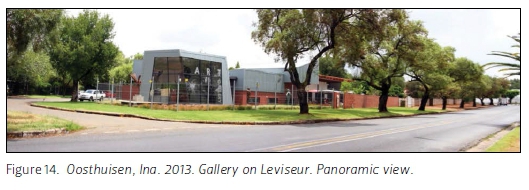

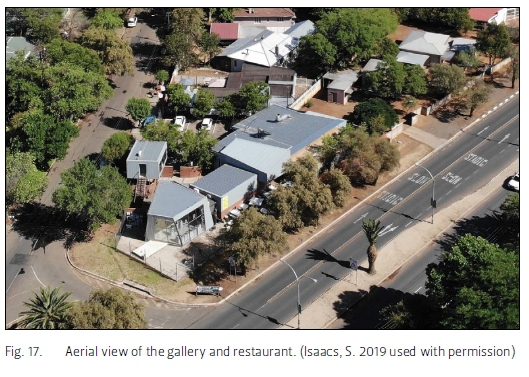

Situated in a semi-suburban, light commercial area, Gallery on Leviseur7 is a design by Bloemfontein practice SN Architects. The building is located on what used to be a corner residential erf. The design is an assemblage of several spatial volumes, with the core of the design, the large glazed exhibition space (named the bubble by the original owners) on the southern corner of the site. (Fig. 10 no. 3) Additional spaces are linked to the core, such as the restaurant and an administrative office that was added as a separate hermitage. The context here, in contrast to the dense urban quality of Rosebank, is that of a suburb transitioning into a commercial area.

As is the case with Circa, the design of this gallery in Bloemfontein centred on a unique spatial composition. But where Circa is defined as single form, and the threshold and in-between spatial qualities embraced through its reed-like screen, the use of glass and complex spatial composition is the focus at Leviseur. Vertical elements are juxtaposed and create an interesting elevation, and the composition combines various dynamic forms in a coherent whole, while still referencing the Free State vernacular (Nunes in Leading Architecture and Design 2014: 18).

The main gallery space (bubble) is glazed to the south and forms the hierarchical point of the design. By using the twisted geometry in contrast to the linear simplicity of the secondary gallery space and the restaurant, an edge is created between the elements. The conceptual interaction of threshold and edge is evident in several instances. If the building is analysed from the inside out, the two gallery spaces reveal the first edges. When approached from the western entrance, the experience is related firstly to the glazed space, uniquely suited to the exhibition of sculptural works. This main space echoes the idea of the city as museum, as a protective element of its artwork.

The space of 'the bubble' was initially intended and designed to house sculpture. As Nunes (2018: interview) mentions:

I paid quite a lot of attention to how one would experience moving through the spaces. Between the primary (dynamic) corner exhibition space (known as "the bubble") which was initially intended to house primarily sculptures, and the more formal linear space meant to house primarily pictures/paintings, there is a narrower transition zone which acts as a threshold.

The curating here is somewhat haphazard, but with a focus on local artists and contemporary works. Both the 'bubble' and linear addition are often used as a function venue, and artists' workshops have also been hosted here. The spatial morphology, as a recognisable space from the street, unfortunately creates difficulty for exhibitors. The pragmatics of a curated exhibition demands large spaces and the space here quickly becomes cluttered. Smaller works need to be selected with care to contend with the scale and presence of this part of the gallery. The large glazed surfaces also present challenges and limit the hanging of larger works. As indicated by Nunes, the space is effective for sculpture, but other works require a level of curatorial skill not always seen here.

As one moves from the interior outward, the courtyard spaces are enclosed by the perimeter wall and fence, and are well connected to the main exhibition space visually. The main entrance gate is defined boldly by the elevated office and workshop space (9) (Fig. 10), separated from the main composition. The definition of this edge at the entrance reinforces the border between outside and inside the gallery site, rather than softening it to form a boundary. The raised office gains a guardhouse-like connotation as when crossing between controlled spaces. The embodied character of this entrance is significant, and the demarcated edge gains a ceremonious quality. The edge between the surrounding context and gallery site is explicit and places this building more in line with the earlier palatial typologies than effectively challenging this notion.

On plan (Fig. 10), the articulated threshold between the main exhibition space (3) and secondary gallery (2) is evident and provides an interesting experience in moving from the main space to the smaller end towards the restaurant. However, the possibility of moving from north to south to cross from the narrow space into the main exhibition space is lost. If the experience could be choreographed in this opposite direction leading up to the lantern (bubble), the connection of moving from the 'traditional' white box to the slightly deconstructed protective dome could have been striking. In this sense, the gallery could have questioned the existing typology, known in Bloemfontein in general only in the form of Oliewenhuis. Disappointingly the interesting and dynamic spatial composition does not deliver on its promises and the potential of the threshold is not fully realised, especially now (2019) as the new owners have adapted the building.

"The threshold then is not only a potential site of suspension as well as interruption, but also a place of rigour and work - the threshold between body and mind is also one between poetry and its reader, painting and its observer, music and its audience." (Mukherji 2013:xxiii) As a space for rigour and work, the spatial opportunity of Leviseur is not clear. The main space does offer a somewhat ambiguous statement to the visitor and the passing motorist. The use of glass reveal s this added layer of complexity. Beer (2013: 3) describes the window as a potent element regarding the conceptualising of the threshold:

"The window registers connection and difference between interior and exterior. It allows us to be in two scenes at once. It affirms the presence of other ways of being, other patterns of objects, just beyond the concentrated space of the observer."

The use of the glazed exhibition space creates a view into the gallery from the street edge, blurring the edge between the protected museum interior and street. Especially at night when the space is lit, it transforms into a lantern that can display its role as space for art and opens the white box to the public. But, the exhibition needs to be curated to play this role.

".windows are such an eloquent threshold, indeed embodiment of some of those essential qualities and associations that make the threshold a site of poetics. Like glass the threshold itself, though not a material medium, has nevertheless that combination of porosity and resistance that creates pressures between which the imagination thrives." (Mukherji 2013:xxi).

However, as Beer (2013: 3) observes, a glazed surface not only functions as a connecting element but also asserts exclusion.

This reflective edge teamed with the physical border of the perimeter wall, the somewhat inaccessible sculpture garden that has been replaced by paving (2018-2019) and the definite line of General Dan Pienaar Road reinforce the edges that the lantern-like space tries to cross in the first place. The ambiguity is further established since the design simultaneously breaks the edge by opening up the main exhibition space to the public realm but also redraws the edges in physical boundaries through the use of the perimeter fence (even though it does not create a visual barrier), curved wall toward the west and the shielding of the building through the use of corrugated iron elements.

The opportunity was missed to question the predominance of the line. Ultimately the dynamic spatial compositions are fenced in by a municipally determined site boundary. This negates both the drawing in of the pedestrian and the breaking of the edge in the security-fenced suburb. Of course, practical considerations form an essential part of the architect's dilemma, but it remains unfortunate that the dynamism of Circa could not be achieved in this instance. The budget, client and site restrictions played a marked role here, but for this analysis, I look at the completed work, rather than at the influencing factors such as budget or time restrictions.

Nonetheless, the attempt to reframe the Bloemfontein contemporary gallery context is ambitious. Nunes makes new morphological gestures and attempted a spatial composition aimed purely at sculptural exhibition. However, as an inconic art space, it is ultimately unsuccessful. Not only in the aesthetic and compositional instance is the sculptural quality of Circa clear, but also in the way in which Circa attempts to draw the pedestrian closer and 'give back' to the street, even if this is largely symbolic. The engagement with the street is not perfectly solved but is more open and engaging than the relationship Leviseur has to its immediate street frontage. Unfortunately, Leviseur does not achieve either the compositional simplicity or the pragmatic urbanism of Circa. Mukerji (2013:xxi) echoes Casey in stating the importance of the gap as a boundary space, or a type of threshold:

"Like glass, the threshold itself, though not a material medium, has nevertheless that combination of porosity and resistance that creates pressures between which the imagination thrives ...That gap is a type of threshold, both physically and metaphorically, embodying the enticement of what lies just out of reach, the reality of the barrier as well as the possibility of stepping across, the permeable but inalienable difference between inside and outside."

The design at Leviseur is ambiguous by both inviting the crossing of the threshold between art gallery and urban environment, but also by establishing new edges, enclosed and defined by the road and the concerns around existing edges and security (Fig. 13).

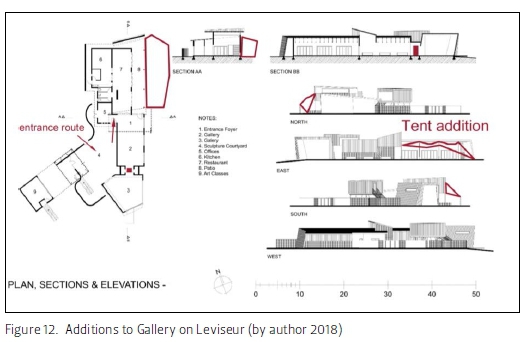

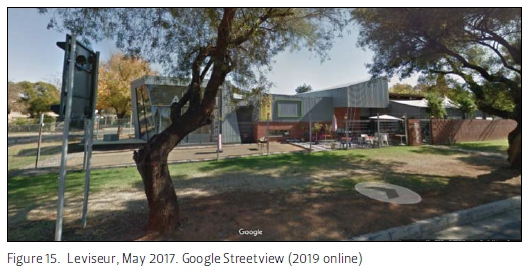

The building has been slowly adapted (Figs. 14,15) as an event space, with the eastern edge extending with temporary structures. Canvas tents have been added to the east, extending the restaurant space along the edge of the site. As mentioned, the exterior garden seen in Fig.12 has also been replaced by paving as part of the restaurant expansion (Fig. 15).

Adaptation of a design

In the case of Leviseur, several changes have been made by the users, and these adaptations have engaged the context in different (if not architectural) ways. The restaurant expansion with the use of canvas tents up to the edge of the boundary wall has created a larger space for seating and presumably increases the economic viability of the restaurant.

The gallery is now an additional function of 59 Café Plenty that has replaced the gallery as the primary functional focus of the building. The additions have detracted from the morphological statement of the design of the building. The sculptural quality, although never as striking as Circa, was an attempt at a re-framing of the gallery in Bloemfontein. The sculptural quality is now lost through the additions, that blurred the edge but established a new frame - that of the restaurant, rather than art space.

It is evident from the adaptations that the original design did not adequately address the current spatial needs. The change in function is commercially driven, and with the shift of focus from gallery to restaurant or function venue, the conceptual depth and role of the building as a physical framing device becomes unclear; again the curatorial role is also a factor to consider. The layers of thresholds and spatial transitions have become blurred and ineffective. The problem of the focus of the space and function is addressed by Nunes (2018) himself in an interview five years after its opening:

Initially the building was to serve as a Gallery space with a small Café component, which in my opinion was never going to be commercially successful right from the start. The result is that the building is being used primarily as a restaurant/function venue with a gallery component but was never designed to be used as such.

Most - if not all the changes to the building were made in an attempt to generate the financial returns which the gallery never could, and I somehow feel that the building should from the start have been designed as a Restaurant and function venue with a gallery component - not the other way around.

As a space for developing artists, and where contemporary art that falls outside Oliewenhuis's mandate can be exhibited, Leviseur has the opportunity to create a gateway, a softer boundary for new artists. However, if the threshold is blurred to such an extent that it neither functions as gallery nor a community exhibition space, it is difficult to see its impact as architectural and exhibition space. The frame however skewed, remains a relevant factor for exhibition spaces, both as architectural works and as institutions.

Thresholds and urban interactions

Both the contemporary architectural experiments are an effective way of reframing the gallery, but in terms of crossing the threshold, further morphological and spatial experiments may need to be developed. Crossing thresholds but simultaneously creating new edges is problematic, and not unique to Leviseur. At the end here, the restaurant as a social space has become a more successful function than the gallery.

The remaining borders in South African cities, in all their different guises, are addressed by these types of interventions, and it reframes the connotation of these spaces, as with Circa. The need for creative approaches to the edges between galleries and cities is not only related to the physical nature of cities but also to the experience of art and the viability of these buildings as art works. Where the difference between inside and outside and the city and gallery becomes more subtle, the interactions with both may change.

"Such an imperceptible transition may make the apparent separate realities of outside and inside less divergent; may also make possible a cross-reference between painting and street so that the first may become more real, the second less squalid" (Brawne 1965: 9).

Bo th these small-scale architectural experiments can be seen as attempts at reframing the museum concept in the South African city. Although neither break the bonds completely nor address the threshold as the crux of the design, the spatial experiments and the resultant experience and redefinition of a context are important in South African cities. As artworks in their respective cities, both Circa and Leviseur as sculptural works are welcome and needed additions to the urban collections. Regarding the re-framing of Rosebank or the north of Bloemfontein, Circa opens the discussion on South African museum architecture, while Leviseur, on the other hand, has been redrawn by those inhabiting it. Leviseur provides other lessons in what is possible in secondary cities.

Both these buildings are products of their cities. Johannesburg, the sprawling metropolis, as a gallery, houses different works and invites different experiences to Bloemfontein, a semi-rural city with a smaller market for commercial gallery space.

The most challenging task is perhaps not only in dealing with the threshold, the borders and boundaries related to exhibition space, but with the building as icon within its unique contextual space. The notion of the city as a container for relationships may inform the production of spaces in South African cities, especially secondary cities. Although viewing space as a container is not typically associated with ideas of relational space, the containing boundary as an indistinct edge, directs this idea away from the abstracted container and towards the more ambiguous relationships of the built environment.

This relationship can create threshold spaces where the embodied experience is authentic, where both the visualised building and the experienced space address its context and the need for new interactions.

Bibliography

Anon. 2014. A sense of dynamism. Leading Architecture and Design. March/April 2014: 16-20. [ Links ]

Beer G. 2013. Windows: Looking in, looking out, breaking through. In: Mukherji S (ed). Thinking on thresholds: the poetics of transitive spaces. London: Anthem Press. [ Links ]

Boettger T. 2014. Threshold Spaces: transitions in architecture analysis and design tools. Basel: Birkhäuser. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783038214007 [ Links ]

Bravvne M. 1965. The new museum: architecture and display. New York: Praeger. [ Links ]

Cache B. 1995. Earth moves: the furnishing of territories. Cambridge: MIT Press [ Links ]

Casey E. 2002. Representing place: landscape painting and maps. London: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Casey E. 2004. Keeping art to its edge. Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities. 9(2): 145-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969725042000272799 [ Links ]

Casey E. 2008. Edges and the in-between. PhaenEX. 3(2). Available at: http://www.groundsite.org/Casey_EdgesAndTheInBetween.pdf [accessed on March 9 2019].https://doi.org/10.22329/p.v3i2.643 [ Links ]

Carter M. 1990. Framing art: Introducing theory and the visual image. Sydney: Hale and Iremonger. [ Links ]

Carman J. 2006. Uplifting the colonialphilistine: Florence Phillips and the making of the Johannesburg Art Gallery. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

CARMANJ(Ed). 2010. 1910-2010 One hundred years of collecting:The Johannesburg Art Gallery. Pretoria: Design>Magazine [ Links ]

Chipkin CM. 1993. Johannesburg style: Architecture and society 1880s-1960s. Cape Town: David Philip. [ Links ]

Davidts W. 2006. Why Bother (about) architecture: contemporary art, architecture and the museum. In: Graafland A and Kavanaugh LJ (Eds). Crossover: architecture, urbanism, technology. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers. Available at: https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/352573 [accessed on March 25 2019]. [ Links ]

Dovey K. 1999. Framing places: mediating power in built form. 2nd ed. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203267639 [ Links ]

Eicker K. 2009. Iconic yet accessible. ARCHI-Technology. December 2009: 7-15. [ Links ]

Esrock EJ. 2010. Embodying art: the spectator and the inner body. Poetics Today 2(31): 217-249. https://doi.org/10.1215/03335372-2009-019 [ Links ]

Everard Read Gallery. 2018. About us. Available at: https://www.everard-read.co.za/gallery [accessed on October 10 2018]. [ Links ]

Fenn T and Hobbs J. 2013. Preparing undergraduate design students for complexity: a case study of the Johannesburg art gallery project. Gaborone International Design Conference 2013: Design Future: Creativity, Innovation and Development. Available at: < http://www.fennhobbs.com/papers/preparing_undergraduate_design_students_for_complexity.pdf> [accessed on March 26 2019]. [ Links ]

Francis RL. 2006. The explosion of museum architecture - Global Province. Available at http://www.globalprovince.com/museumarchitecture.htm [accessed on March 9 2015]. [ Links ]

Freschi Frederico and Lowe N. 2010. Collecting and curating. Circa on Jellicoe: blurring the boundaries between public and private. In De Arte 82: 76-82. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043389.2010.11877133 [ Links ]

Friedburg A. 1993. Window Shopping: cinema and the postmodern. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Gallery on Leviseur. 2018. Website homepage. Available at: http://www.galleryonleviseur.co.za [accessed on October 30 2018]. [ Links ]

Haasbroek H. 2014. Die ontstaan van die unike ondergrondse Reservoir-galery (2002) by Oliewenhuis-kunsmuseum in Bloemfontein. (The origin of the unique underground Reservoir Gallery (2002) at Oliewenhuis Art Museum in Bloemfontein) Navors. Nas. Mus., Bloemfontein 30(4): 47-70. [ Links ]

Langfeld G. 2018. The canon in art history: concepts and approaches. Journal of Art Historiography 19 (December): 1-18. [ Links ]

Leupen B. 2002. The Frame and the Generic Space, A New Way Of Looking To Flexibility. Summary. Available at: https://www.irbnet.de/daten/iconda/CIB12026.pdf accessed 2018-06-19. [ Links ]

Based on Leupen B. 2002. Kader en generike ruimte: een onderzoek naar de veranderbare woning op basis van het permanente. PhD thesis. Technische Universiteit Delft. [ Links ]

McClellan A. 2008. The art museum from Boullee to Bilbao. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Maak N, Klonk C and Demand T. 2011. The white cube and beyond. Tate etc 21(spring). Available at: http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/articles/white-cube-and-beyond. [accessed on March 8 2015]. [ Links ]

Mukherji, Subha (Ed.). 2013. Thinking on thresholds: the poetics of transitive spaces. 1st ed. London: Anthem Press. [ Links ]

Nunes S. 2014. Gallery on Leviseur. Available at: http://www.snarchitects.co.za/#!projects/cwzm [accessed on March 3 2015]. [ Links ]

Nunes S. 2018. SN Architects structured interview. Email interview by Odendaal (née Verster). W. [ Links ]

Pallasmaa, J. 2005. The eyes of the skin: architecture and the senses. Chichester: Wiley Academy. [ Links ]

Pallasmaa J. 2011. The embodied image: imagination and image in architecture. Chichester: Wiley. [ Links ]

Peri Bader A. 2018. Museums and urban life in the cinema: on the ordinary and extraordinary architectural experiences. Emotion, Space and Society 29: 22- 31 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2018.07.011 [ Links ]

Resina JR and Ingenschay D (Eds). 2003. After-Images of the city. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Raman PG. 2010. Architecture of city sense, Circa Gallery, Johannesburg. Architecture SA, March/April: 8-13. [ Links ]

Verster W. 2014. Observing the city: imagining through faceless figures. South African Journal of Art History 29(1): 101-118. [ Links ]

Verster W. 2018. Framing the gallery: crossing the threshold in the South African urban context. Conference of the International Journal of Arts and Science IJAS 2018 24-28 June, Florence, Italy. [ Links ]

Verster W. 2016. Domestic space in the contemporary art gallery: Sven-Harrys Art Museum, Stockholm and Circa on Jellicoe, Johannesburg. South African Journal of Art History 31(2): 49-62. [ Links ]

Wolf W and Bernhart W (Eds). 2006. Framing borders in literature and other media. Amsterdam: Rodopi. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789401205214 [ Links ]

Wolf W. 2006. Introduction: Frames, framing and framing borders. In: Wolf W and Bernhart W (Eds). Framing borders in literature and other media. Amsterdam: Rodopi. [ Links ]

First submission: 27 March 2019

Acceptance: 6 November 2019

Published: 9 December 2019

1 The relevance of Bloemfontein as a secondary city is in its examples of art spaces that rival those of other metropolitan centres. The type of urban space can also be analysed in contrast to the examples of Johannesburg and Pretoria and expand on the spatial engagement in secondary cities in central South Africa.

2 The building was designed in 1935 by William Mollison and John Stockwing Cleland as architects of the department of public works and opened in 1941. In 1985 President PW Botha released the residence to the National Museum for the purposes of an art museum. Oliewenhuis opened in 1989 (Haasbroek 2014: 51).

3 The reservoir gallery is a converted water reservoir that now serves as a gallery space one story below ground level. (Haasbroek 2014)

4 Such as hosting an open air film screening event. The public are also encouraged to use the gardens for picnics.

5 The Unisa Art Gallery is worth mentioning, as it also claims direct public access, however it does not have the same green space as a surrounding frame, and it may be argued that the proximity of the institutional border of the UNISA campus overshadows the public engagement. The gallery could be investigated in future papers.

6 Studio MAS received the South African Institute of Architects Award for Excellence 2012 for the design of CIRCA. SN Architects received the South African Institute of Architects (Free State) excellence award for architecture in 2015.

7 The building also houses a restaurant and is often interchangeably referred to as Leviseur or 59 Plenty. I use the name Gallery on Leviseur rather than the reference to the restaurant 59 Plenty.