Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Academica

On-line version ISSN 2415-0479

Print version ISSN 0587-2405

Acta acad. (Bloemfontein, Online) vol.51 n.1 Bloemfontein 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150479/aa51i1.2

ARTICLES

From Pacific to traffic islands: challenging Australia's colonial use of the ocean through creative protest

Nadine El-EnanyI; Sarah KeenanII

ISchool of Law, Birkbeck College, University of London, E-mail: n.el-enany@bbk.ac.uk

IISchool of Law, Birkbeck College, University of London, E-mail: s.keenan@bbk.ac.uk

ABSTRACT

The Australian High Commission in London, located in an imposing, heritage-listed building known as Australia House, works to project a positive national image in its colonial motherland. Australia House has been the subject of a number of creative protests which utilise the building's location on a traffic island to draw attention to Australia's colonial use of the ocean as part of its ongoing mission to reign supreme as a white island in the otherwise racialised south Pacific. The protests draw attention to the violence Australia seeks to conceal in the distant island refugee prison camps on Manus and Nauru, and use the place of Australia House in the heart of London to "bring home" the historical colonial dimensions of Australia as a place today. Reading the protests through the lens of critical geography and legal history, we argue that the protests work to disrupt the business of the Australian High Commission by maneuvering the physical space of and around Australia House such that they memorialize, expose and interrupt the racist violence which the High Commission seeks to hide.

Keywords: Australia House, protest, Manus, Nauru, space

Introduction

The Australian High Commission in London is located in an imposing, heritage-listed building known as Australia House. A stone's throw away from the Royal Courts of Justice, Australia House sits on a traffic island at a busy intersection in central London. Its imperial architecture and navy blue flags are peppered with mini Union Jacks marking out the diplomatic territory of one of Britain's most devoted former colonies. The commission proudly boasts that Australia House is the longest continuously occupied foreign mission in London (Australian High Commission United Kingdom [AHCUK] n.d.). Inside the building's sandstone walls, the Australian High Commission works alongside Tourism Australia and The Britain Australia Society to perform the day-to-day work of representing the Australian state in the heart of the colonial motherland.

As is the case for all embassies and high commissions, Australia House works to project a positive national image. For Australia House, this work means minimising and obscuring from public view the structural violence of the Australian state, particularly against Indigenous people and against refugees. A recent wave of protests has creatively used the physical space which outlines and surrounds Australia House in London to re-position the High Commission building such that it becomes, temporarily, a memorial to the racist violence it seeks to hide. The protests utilise the spatiality of the Australia House building, in particular its location on a traffic island, to visualise, simulate and make audible the violence of Australia's policy of punishing and deterring people who travel via boat to seek asylum in Australia.

Taking inspiration from these protests, in this article we offer an analysis of Australia which highlights the violent policies it uses to maintain itself as a white island nation in the South Pacific. Examining Australia's brutal policy of deterring migrant boat arrivals, we argue that Australia's attempts to keep the oceans that surround it empty of migrants can be seen as an aquatic post-script to its founding racist fiction that the land was empty (terra nullius) when British colonisers arrived. In particular, the small islands which surround the Australian island-continent have long been used as sites for the isolation and punishment of racialised people whose existence is perceived as a threat to white Australian sovereignty, from Aboriginal 'half-castes' to Muslim refugees. In the final section we discuss three of the recent creative protests at Australia House, each of which memorialise Australia's recent violence levelled against racialised bodies on these islands and in the waters that surround them. The protests turned the High Commission building into a cinema screen showing portraits of the dead; manoeuvred High Commission security guards into publicly simulating Australia's "stop the boats" policy; and used the extended pavement around the High Commission entrance as a theatre hosting a reading of leaked incident reports detailing abuse and other horrors which have occurred in one of Australia's Pacific island refugee prisons. Through their creative use of the physical space of Australia House, these protests interrupt and challenge both the High Commission and the ongoing colonial process that is 'Australia'.

Place as process: Australia from "empty land" to emptied seas

Only a meta-historical and transhistorical approach can unpack the peculiarities associated with the issue of Manus and Nauru. Only a rigorous analysis of a colonial presence in Australia and its tactics in the region can disclose the reality of violence in these island prisons. This issue must be understood as the annihilation of human beings, the incarceration of human beings within the history of modern Australia; it is a long history, a comprehensive history, it is intertwined with its colonial history. This form of affliction, inflicted on people in similarly vulnerable situations, has always existed in the history of modern Australia (Behrouz Bouchani 2017).

Writing from Manus Island, where he has been imprisoned for over five years, Iranian journalist and refugee Behrouz Bouchani has emerged as one of the most insightful cultural commentators writing on Australia today. The incarceration and attempted annihilation of human beings has indeed always been part of Australia; it is the basis of its existence. To understand the place that is Australia today, we must understand its colonial foundations and its relationship with its South Pacific island neighbours.

The land and waters now known as Australia have a history which pre-dates the Australian nation-state by at least 60 000 years. The British founded Australia in 1770 on the basis that this long history did not exist. They did so using the legal fiction that the land was terra nullius or 'empty' and belonging to no-one (Mabo v The State of Queensland 1992 175 CLR 1 [Mabo 1992]). Aboriginal people were regarded as "too low on the scale of civilisation" to count as properly human. Established as a penal colony, from 1788 fleets of ships carrying British prisoners arrived on the island-continent, with the British authorities assuming there was no need to seek permission from or negotiate land rights with the native population.

Upon federation as a nation in 1901, the new Australian nation immediately passed the Immigration Restriction Act 1901, also known as the White Australia Policy. Cait Storr argues that both federation and the early 20th century establishment of Australia as a sovereign subject of international law, were driven by attempts to formalise an Australian "sub-empire" in the Pacific (2018).

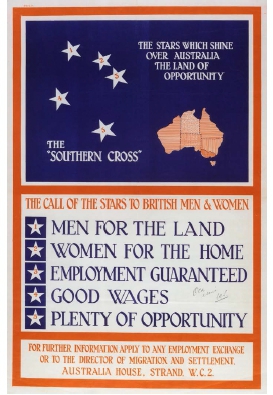

Australian sub-imperialism drew explicitly on the Monroe Doctrine (that European powers would cease colonising the American continents, in recognition of the US as an ally with a future monopoly on colonisation in that area), and posited a self-evident right of the Australian colonies to regional supremacy in the Western Pacific (Storr 2018: 336). Both ideologically and practically derived from British imperialism, Australian imperialism in the Pacific also furthered the project of white British supremacy. Following World War I, Australia sought to boost its population by offering free passage and land grants to British immigrants. As the poster below shows, Australia was advertised as an implicitly empty "land of opportunity" for white Britons, who were encouraged to seek information about migrating to Australia by visiting Australia House in London.

The foundational racist fiction that the land was 'empty' remains crucial to the way in which Australia produces itself as a place today. While Australian courts have recognised that terra nullius was factually false, the sovereign nation based upon that falsity has been upheld (Mabo 1992), and with it the myth that the land was taken by peaceful 'settlement' rather than violent conquest. As Justice Brennan put it, questioning Australian sovereignty and the myth of settlement would "fracture the skeleton of principle which gives the body of our law its shape and internal consistency" (Mabo 1992: para 29). Yet ongoing production of Australia as a white nation continues to require extreme levels of violence levelled against racialised people, who are constructed as dangerous and inferior.

While 'place' tends to be understood as locatable, permanent and definite, places have different meanings to different people, and change over time. Tim Cresswell argues that place must be understood as "an embodied relationship with the world", and therefore never 'finished' but constantly being performed, like any relationship (Cresswell 2004: 34). Doreen Massey also insists on the unfinished nature of place. For Massey, place is a process, "an articulated moment in networks of social relations and understandings", which will necessarily change over time, as moments pass, and which will be experienced differently depending on how you are located within that moment (Massey 1993: 66). Arguing against parochial, insular understandings of place, Massey writes that "what gives place its specificity is not some long internalised history but the fact that it is constructed out of a particular constellation of relations, articulated together at a particular locus" (ibid). Place is thus still definite and material, but it gains its definition and materiality through its location within networks of relations, which are not fixed in time. The place that is Australia today is defined by its embodied relationship with the world, which as we discuss below, involves an aggressive defensiveness of the land and waters it currently comprises, and the retention of close diplomatic ties with Britain. The performance this involves - of imprisoning on small, remote islands anyone seeking asylum who travels by boat into Australian waters, while also maintaining an international image as a safe and peaceful nation - is both violent and extreme. However, it remains consistent with Australia's long history of white supremacist violence and racialised assertions of territorial and maritime sovereignty. Australia signifies a moment within British and world history, a colonial history in which Australia continues to reproduce itself as a locus for white people in the South Pacific.

While there is a rich scholarship analysing Australia through the critical lens of terra nullius and the ongoing racist theft of land, there is much to be gained from analysing Australia's relationship with the sea. Renisa Mawani has encouraged scholars to consider "how oceans may reorient studies of law and settler colonialism by expanding the sites and surfaces of colonial legal power" (Mawani 2016: 109). According to Australia's current Migration Act, people who arrive irregularly by boat are referred to as "unauthorised maritime arrivals" (formerly "offshore entry persons"). Created as a legal category in 2013, being an "unauthorised maritime arrival" means being subject to forced transfer by the Australian government to one of its "offshore processing centres" on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea, or Nauru (Migration Act 1958: Ss5AA). The Australian government uses posters featuring a small boat in a menacing sea to deter irregular migrants from attempting to reach Australia by boat. This outward-facing government messaging is mirrored by incessant domestic messaging from both major Australian political parties that they can be trusted to "stop the boats" (Fleay et al. 2016).

Australia's aversion to sea-arrivals and its attempts to keep the oceans that surround it empty of migrants can be seen as an aquatic postscript to its founding racist fiction that the land was empty when the British arrived. As Mawani points out, British colonial explorations and seizure of lands has always relied on control of the sea (Mawani 2018). Those who travel irregularly by sea today are for the most part racialised people from poor southern countries with histories of colonisation, neoliberal exploitation in the form of debt, land-grabbing, and calamity-inducing International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank-imposed structural adjustment programmes and of military intervention by northern countries, and are disproportionately suffering the effects of climate change (El-Enany 2017). Enormous expense and military force is called upon to empty the waters around Australia of racialised migrants, an ongoing and impossible process which has also involved Australia's exertion of control over its small island neighbours. The racist and lethal project that is Australia thus extends beyond structural invasion of Aboriginal land (Wolfe 2006) to the enactment of violence against racialised groups through control of the sea.

A network of relations: islands in the South Pacific

The map below shows several islands in the southern Pacific Ocean: Australia; Christmas Island, Australia; Palm Island, Australia; Manus Island, Papua New Guinea (PNG); the Republic of Nauru. While this cartographic representation visualises important dimensions of these South Pacific islands, to understand each marked place requires examining their histories and relations with each other and the world. As discussed above, Australian federation and sovereignty were intimately connected to attempts to formalise an Australian sub-empire in the Pacific in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. Historically, the drive to establish Australia as a white nation in the otherwise black and brown South Pacific was evident not only in the legal denial of Indigenous existence on Australian territory and in Australia's racially exclusive immigration policies but also in Australia's colonial relations with its Pacific neighbours. These relations continue today. In particular, the small islands which surround the Australian island-continent have been positioned as sites for the isolation and punishment of racialised people whose very existence on the continent threatens the fragile skeleton of white Australian sovereignty. Although physically located in the South Pacific, Australia's political institutions and dominant culture strongly identify as Western European, and retain a particular connection with Britain. Aside from the union jack still emblazoned on the Australian flag, the retention of the Queen of England as head of state, and preferential visa requirements for British migrants, Britain is still one of Australia's favourite travel destinations, and many Australians aspire to live and work in London.1 Australia House regularly hosts events encouraging British tourism and migration to Australia, and fostering cultural and economic ties between the two states.2

Palm Island, part of Australian territory, has long been used by Australia as a place for the punishment and isolation of 'dangerous' non-whites. From 1914 to the late 1930s Palm Island was an island prison for Aboriginal people from the mainland who colonists considered dangerous (Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody [Aborginal Deaths Commission] 1991). Those considered dangerous included all "half-castes", who were regarded as a biological threat to the white race - the Queensland government saw Palm Island as a particularly attractive location in which to place indigenous people because it effectively isolated them from white people (Aboriginal Deaths Commision 1991). Aboriginal people from at least 57 different language groups were sent to Palm Island during its life as a penal colony (McDougall et al. 2006: 27). The state government finally permitted Palm Island to form its own local council in 1986,3 but this small grant of autonomy was accompanied by a withdrawal of infrastructure from the island. As the residents on Palm Island are overwhelmingly the descendants of former reserve inmates who were given little or no remuneration for the work they were made to do on the island, there is also no economic base upon which to begin local industry. As such, Palm Island today is a place of poverty. Houses are overcrowded (averaging 17 people per house) and run-down. Unemployment on the island is over 90% (McDougall et al. 2006: 35). Suicide and domestic violence rates are disproportionately high (Boe 2005: 5). The island was in the news following the 2004 killing in custody of an Aboriginal man, Cameron Doomadgee by a white police officer, Chris Hurley. After years of delay and prevarication by the authorities, Hurley stood trial for manslaughter and assault and was quickly acquitted of both charges by an all-white jury (Keenan 2008).

The other small Australian island marked on the map is Christmas Island. Previously a British colony, the British government transferred sovereignty over Christmas Island to Australia in 1958. In 2001 Australian Prime Minister John Howard implemented a series of jurisdictionally complicated measures known as "The Pacific Solution". The perceived 'problem' which the 'solution' was addressing was the arrival of migrant boats, mainly carrying Muslim refugees, into Australian waters. Although seeking asylum by any vessel is explicitly permitted according to the 1951 Refugee Convention to which Australia is a party, Howard captured popular white nationalist sentiment when he declared that "we will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come" (Howard 2001). The arrival of refugees by boat was constructed as a threat to national security, with Muslim refugees presented as potential terrorists in line with pervasive anti-Muslim racism (Dunn, Klocker, and Salabay 2007). One aspect of the Pacific Solution was to excise Christmas Island from the Australian Migration Zone. Under the Migration Amendment (Excision from Migration Zone) Act 2001, migrants who land on Christmas Island are categorised as "offshore entry persons" and thus treated as if they are outside Australian territory.4 The creation of this category meant that in the relatively rare instances in which irregular migrants managed to navigate through waters to physically land on Christmas Island, they would be denied legal recourse to seek asylum in Australian (Morris 2003). As Leanne Weber explains, this scheme places "offshore entry persons" in a perpetual state of non-arrival, and turns Christmas Island into a jurisdictionally confusing zone of Australian sovereignty but without Australian juridical responsibility (2006: 28). A detention centre on Christmas Island is used as a processing point from which refugees are usually either deported or transferred to one of Australia's "offshore detention centres".

Offshore detention on Manus Island, PNG, or Nauru, is the other key element of the "Pacific Solution". Pursuant to agreements with the Papua New Guinean and Nauruan governments, the Australian government essentially rents land on these islands to build and maintain secure "processing centres" for the detention of "offshore entry persons" (since 2013 they are "unauthorised maritime arrivals") (Migration Amendment Act 35 of 2013). At the time of writing there were 800 men on Manus and more than 500 men, women and children on Nauru. Most have been there for over five years. Since July 2013, even after their asylum claims have been decided, any refugee who arrived by boat is disqualified from resettlement in Australia. Instead, refugees are offered resettlement in "third countries" with a significantly lower standard of living and where they are likely to be subjected to further violence and persecution, such as PNG, Nauru or Cambodia (Pearson 2014). The explicit motivation behind the "Pacific Solution" and the third country resettlement scheme is to subject refugees to such dire conditions that others will be deterred from attempting the journey. It is a spectacular performance of cruelty through which Australia asserts and defines itself, both in relation to the region and the world.

While the Pacific Solution was introduced in 2001, Australia's structural racism has long materialised beyond the legal boundaries of its territorial waters, extending to Australia's relations with its South Pacific neighbours. In the mid-1800s, around 60 000 men, women and children from South Western Pacific Islands, including Papua New Guinea, were brought to Australia as bonded labourers for a period of at least three years in the growing sugar industry of the then British colony of Queensland (Banivanua-Mar 2007: 1). As Tracey Banivanua-Mar has observed, "[i]n the aftermath of the abolition of slavery, these labourers provided the essential, cost-neutral, coercible and coloured labour that was deemed essential to the economic viability of white settlement in the tropical belt of Britain's Australian colonies" (2007: 1). To this end, trade in bonded labour continued for 40 years or so "until, at the turn of the twentieth century, amidst the determined and defensive efforts of the Australian colonies to federate as a white nation, the trade was abolished. From 1906 the majority of the then thousand Islanders resident in Queensland were deported" (2007: 1). Within the Papua New Guinean archipelago, Manus Island has long been strategically exploited - during World War II, both Australia and Japan established military bases there. When the Australian government approached the Papua New Guinean government to participate in the "Pacific Solution" in 2001, the decision was made to build the refugee detention centre inside the Manus Island naval base (Green 2004).

Australia's racialised place-making also extends to its relationship with the tiny South Pacific Island Republic of Nauru. Nauru is just over 13 miles long and has a population of 10 000. Australian troops occupied Nauru in 1914, seizing control from German forces. Naomi Klein, in her exposition of the climate crisis has alluded to the connection between imperialism and wealth-driven environmental destruction and human exploitation. In its relationship with the world, Nauru has been a locus of this destruction and exploitation. Klein writes that "Nauru's successive wave of colonizers - whose economic emissaries ground up [Nauru's] phosphate rock into fine dust, then shipped it on ocean liners to fertilize soil in Australia and New Zealand - had a simple plan for the island country: they would keep mining phosphate until the island was an empty shell" (Klein 2014: 163). Nauruans fought hard for their independence and for control of the phosphate industry, eventually winning both battles. In 1967, the British Phosphate Commissioners (BPC) sold the phosphate industry to the Nauruan government for $Aus21 million, and in 1968 Nauru became an independent constitutional republic (Anghie 1993). By this stage, approximately 1/3 of the island had already been mined out (Anghie 1993). In 1989 Nauru launched an action against Australia in the International Court of Justice, the first ever case by a former dependent territory against its colonial authority for abuse of power. The case settled in 1993 with Australia agreeing to pay Nauru $Aus107 million (Australian Treaty Series 1993).

The racialised and majority Muslim refugees who attempt to come by boat to Australia are from Iran, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Iraq and Somalia. On Manus and Nauru, refugees are regularly subjected to abuse, violence, sexual assault and rape. Self-harm and suicide attempts are common (Amnesty 2016). In December 2017 an Australian Federal Court judge made an emergency order that a girl detained on Nauru be medically evacuated to a specialist child psychiatric facility in Australia due to her extreme suicide risk. The judge noted that the girl, who is "not yet a teenager", had already attempted suicide and was possibly developing a psychotic depressive illness rare in a child of her age (FRX17 as litigation representative for FRM17 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection 2018). Since then, following sustained legal and political action, several more children have been evacuated from Nauru, with 17 remaining on the island at the time of writing (Asylum Seeker Resource Centre [ASRC] 2018). The camps have seen riots, hunger strikes and several deaths. Seven refugees have died, including one on Christmas Island. As discussed, Australia maintains its offshore detention policy through exploitative relations with these smaller Pacific islands. This exploitation enables Australia's ongoing performance of cruelty against those constructed as racially inferior and dangerous. Australia thus defines itself as a locus of white power in the South Pacific, where the racist ideals comprising its foundations continue to materialise, though today under its own flag rather than Britain's. Returning to the theories of Creswell and Massey, the place that is Australia is produced through the nation's embodied relationship with its Pacific island neighbours, with the refugees who navigate its waters, and through its ongoing cultural identification with its colonial motherland. This embodied relationship with the world is only possible through the maintenance of complex geopolitical, social, cultural and legal networks which make the South Pacific into the space that it is today.

Resistance at the heart of empire: Guerrilla art and activism at Australia House

Since 2013 there have been a number of creative protests against Australia's harsh offshore detention regime at Australia House in London. Below we discuss three of these protests, which used objects and actions to manoeuvre the space around Australia House such that it temporarily became a memorial to the violence of this regime, which its usual mission is to conceal. The protests can be understood as what Margry and Sanchez-Carretero define as grassroots memorialisation, that is "the process by which groups of people, imagined communities, or specific individuals bring grievances into action by creating an improvised and temporary memorial with the aim of changing or ameliorating a particular situation" (2011: 2). While each of the protests below clearly required a degree of planning, they also necessarily involved improvisation because they were unsanctioned and public. These grassroots memorialisations brought grievances into action at Australia House with the aim of disrupting Australia's public image in London, and ultimately of trying to bring about a shift in the ongoing process that is 'Australia'.

Projecting images of the dead

Australia House is part of Australia, both in the diplomatic sense that the High Commission is practically recognised as Australian territory,5 and symbolically in the public relations work of Australia House, essential for maintaining 'Australia' as a particular locus of social meaning. Explaining the history of the building, the Australian High Commission website offers a narration with notable resonances with the colonial history of Australia's island continent.

Victoria House had been built in 1907 on the corner of an island site, bounded on the south and east by the Strand, on the north-east by Aldwych and on the west by Melbourne Place. A massive demolition scheme many years before had left this vacant triangle of land, which had been empty so long that wild flowers bloomed there and the Daily Graphic called it "a garden of wild flowers in the heart of London... this rustic spot in urban surrounding (AHCUK n.d.).

The Australian government purchased the empty urban island in 1912 and began construction the following year. Due to delays as a result of World War I, Australia House was not in operation until 1918 when King George V officially opened the building. The building's striking architectural façade features two stone sculptures which represent Australia as a brave and victorious British colonial story in which a wild, empty island has been civilised and made productive. In the first statue, 'Prosperity of Australia', a woman holds a dove to her breast while her other hand is outstretched with her palm up, symbolising peace and generosity. She sits above two men, one holding a ram's head and the other a bale of wheat to represent the bounties of British agricultural practices on Australian land. In the second, Awakening of Australia', a woman rises from sleep as if to present the birth of a new era for this island continent. She also sits above two statues of a man. In the first he reads from what looks like a map, and in the second, he appears weak and tired. All figures in the statues are white. Deborah Cherry notes that these sculptures were erected within the context of an early 19th century "statue mania" in Britain and the colonies, with central London littered with statues memorialising events which Londoners themselves are unlikely to have experienced (Cherry 2006: 684). Such statues evoke particular narratives of empire. The Australia House statues are no exception. They serve to erase the continent's Aboriginal history and present, along with the genocidal violence of the colonial powers. The building facade thus accords with the diplomatic work done within it, positioning Australia as a respectable place with a proud history and prosperous future.

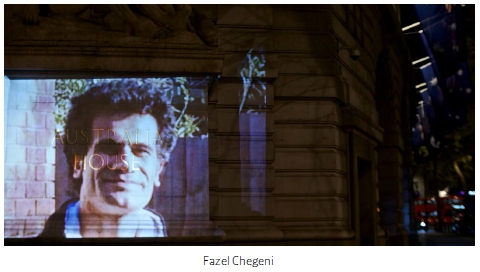

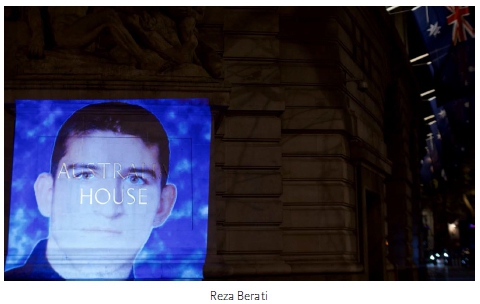

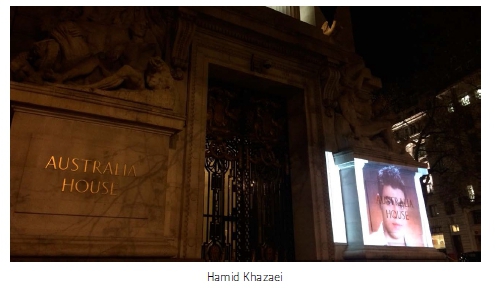

On April 22 2016 guerrilla projectionists lit up Australia House with the faces of three recently deceased young men, each of them refugees who died while under the 'care' of the Australian government on Christmas Island, Manus Island and Nauru. All three refugees were Kurds fleeing persecution in Iran. Their portraits appeared directly below the Awakening of Australia statue, their life-filled faces covering in vivid colour the sandstone plinth on which the statue sits. The projection was unannounced and unsanctioned, with the images and video appearing in media and social media the following morning (London remembered refugees... 2016).

Fazel Chegeni, a 34-year-old refugee, was found dead at the bottom of a cliff on Christmas Island last November. Chegeni, who had spent all but a few months of his four years in Australia confined to immigration detention, was suffering from severe mental health problems and had made a desperate attempt to escape the previous day. Chegeni arrived in Australia by boat in 2011 and was declared a refugee in March 2012, but was not granted a visa allowing him to be released from detention until April 2013. After being free for eight months, Chegeni was charged with assault in relation to a one-minute 'fight' that had taken place in detention two years earlier. Following legal advice, Chegeni pled guilty and was convicted. The then immigration minister, Scott Morrison, revoked his right to live in the community and he was returned to detention (Doherty 2015). For Chegeni, as a stateless refugee with no safe country to return to, Morrison's decision to revoke his visa meant a sentence of life imprisonment in immigration detention. It is still unclear exactly how Chegeni died. Having suffered rape, torture and imprisonment in Iran, Chegeni's ongoing detention exacerbated his trauma and led to a severe deterioration in his mental health. He had attempted suicide by hanging. It is possible that Chegeni took his own life, though detainees reported Chegeni's death as being "very, very suspicious" and stated that "Serco officers did something to him" (Powell, Ryan and Donald 2015). Chegeni's death triggered a riot in the Christmas Island centre and was met with outpourings of grief from his friends. "Fazel is free now," one detainee said, "God gave him a visa" (Powell, Ryan and Donald 2015).

Reza Berati was 24 when he was beaten to death inside Manus Island detention centre in February 2014. Berati had arrived in Australia by boat in July 2013 before being transferred to Manus Island. Berati was killed during a wave of attacks that occurred when locals broke into the centre. An Australian Senate committee report described the violence as "eminently foreseeable" in light of the inhumane and uncertain conditions in the centre, the growing tensions between detainees and locals, and the inexperienced and inadequately trained private security staff. In 2016 two PNG men received 10-year jail sentences for murdering Berati by repeatedly hitting him with a piece of wood and dropping a large rock on his head (Tlozek 2016). The sentencing judge noted that other parties not before the court were involved in Berati's murder, reportedly including former guards from Australia and New Zealand (Doherty and Davidson 2016). These guards were flown out of Manus after Berati's death and Australia refused to repatriate them to stand trial in PNG.

Hamid Khazaei was 24 when he died in a Brisbane hospital in September 2014 after a blister on his leg became infected and turned septic while he was detained on Manus Island. Australian authorities' bureaucratic neglect and malfunction led to lethal delays and failures in his treatment. Prominent medical doctors have risked criminal charges by speaking out about his case (Doherty and Davidson 2016). Khazaei arrived by boat in Australia in August 2013 and was transferred to Manus Island. He was evacuated to Brisbane in August 2014, where he was declared brain-dead (Laughland 2014). Doctors claimed that the cramped, tropical and unhygienic conditions in the Manus Island centre contributed to Khazaei's initial infection, which involved a bacteria found in tropical and subtropical climates (Laughland and Nissi 2014; Om 2014). According to more than one doctor, Khazaei's death was entirely preventable. His life could have been saved by "cheap and available" drugs, which were not in stock at the centre. Doctors also noted that Khazaei might have survived were it not for needless delays in his emergency transfer to Brisbane caused in part by Australian bureaucrats who questioned the judgement of doctors (Four Corners 2016). The Khazaei family's wish that their son's organs be donated to Australian patients was not able to be fulfilled due to septicaemia having infected his whole body so severely (Atfield 2014).

Pa rt of the aesthetic and political power of the projection was that the images of Fazel Chegeni, Reza Berati and Hamid Khazaei appeared like ghosts on the walls of Australia House - at the literal physical border of Australian diplomatic territory - never to be permitted entry, just as in their short lives. In their appearance directly under the 'Awakening' and 'Prosperity' statutes, they interrupt the narrative of Australia conveyed by the building's architecture. Instead, the haunting projections of the victims of the Australian government's policies memorialised the reality of the country's past and ongoing racist violence, preserving and publicising the memories of these men.

Unstoppable Boat

On June 20 2016, UN World Refugee Day, two women carried a rubber boat into Australia House. The two women approached the Australia House traffic island flanked by a large group of supporters. On reaching the building's main entrance, clasping the boat on either side, they opened the doors and entered the foyer. There they were met by security. Supporters flocked in behind the boat, spontaneously occupying the foyer. Demanding that the boat be granted entry and that Australia end its regime of offshore detention, the activists and supporters remained in occupation of the Australia House foyer until security called in armed police.

This action was a simulation of the Australian government's "stop the boats" policy in the border region of its diplomatic territory in London. By calling the police following the peaceful arrival of a small rubber boat, the Australian High Commission symbolically re-enacted Australia's violent refugee policy. As security guards stopped the boat from continuing into the main body of the building, Australia House was momentarily turned into a replica of Australia's "stop the boats" policy, memorialising the fortress practices the Australian government enforces in the South Pacific. By seeking entry to Australian diplomatic territory, the action also challenged the narrative propagated by the Australian government that the offshore detention policy has been successful in stopping the boats. In fact refugee boats have not stopped attempting to reach Australia. Such boats are met with military force and are towed out of Australian territorial waters by the navy, or returned under the cover of night to places where the refugees face arrest, detention, persecution and violence.

In carrying a boat uninvited onto Australian diplomatic territory, the activists were careful to avoid simulating in any way the violent and disastrous arrival by boat of British settlers on Aboriginal land. The video of the action produced by the activists begins by acknowledging the sovereignty of Aboriginal people over the land and waters now known as Australia.6 Unlike British settler ships, this small rubber boat symbolised refugee boats coming to Australian territory, not as colonisers seeking to claim land through conquest, but in search of a place of safety. The protest happened to coincide with the first day of pre-poll voting in the 2016 Australian federal election. The boat arrived on the traffic island about 50 metres away from political party members handing out how-to-vote cards for the two white Australian men running to be Prime Minister. Since both major parties support the "stop the boats" policy, the election offered no hope for an end to offshore detention. The protest thus ensured the visibility of both the violence of offshore refugee detention and the reality of opposition to it.

Nauru Files Reading

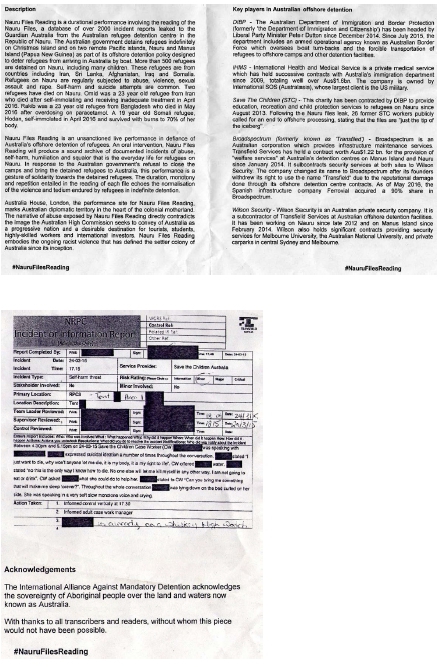

In late August 2016, activists carried out a durational performance involving the reading of the Nauru files, a database of more than 2 000 incident reports leaked from the Australian refugee detention centre on Nauru.7 The performance took place directly in front of the main entrance to Australia House, and has since been mirrored in several cities across Australia (see Loves Makes a Way 2016). A group of seven women transcribed the Nauru files, while more than 30 anti-racist activists partici pated in the reading. Many more attended the performance, which lasted into the night and for more than 10 hours, providing support and sustenance. A crowd consisting of both passers-by and supporters who had heard about the event on social media gathered to listen to the incident reports. Taking their seats on the pavement, this area in front of Australia House was temporarily turned into a theatre, with readers creating a live memorial to the ongoing abuse and daily suffering of those detained on Nauru. More than 300 programmes which gave a brief description of the performance and explained the 'cast' of key players were distributed in the course of the performance.

The re ading produced a sound archive of documented incidents of abuse, self-harm, humiliation and squalor that is everyday life for refugees on Nauru. The performance was a gesture of solidarity with detained refugees, the local anti-racist activists who read out the files extending their political work beyond their immediate realm to those surviving racist violence with roots in the heart of the former British Empire. The duration, monotony and repetition entailed in the reading of each file echoed the normalisation of the violence and tedium endured by refugees in indefinite detention. A snapshot of their daily lives was brought to life in central London, at the border of Australian diplomatic territory. As one of the participants stated after reading on the day, "we want to send a message of solidarity from London to Nauru, and we also want to expose the relations between Australia, Nauru and Britain, which are far apart but also intimately connected".8 A short film of the performance draws from the 10 hours of footage and sound recorded on the day (El-Enany 2016). Published in a major international newspaper, the film has carried the performance and its exposure of the Australian state's racist violence to audiences in Britain, Australia and beyond.

Conclusion

Australia was founded upon the racist fiction that the land was empty and awaiting peaceful white settlement. This fiction remains fundamental to Australian sovereignty, which violently exerts control over racialised bodies attempting to reach safety on its shores via the sea. We have argued that along with its theft and control of land, Australia's use of the ocean to colonial ends also warrants attention. The London protests analysed in the paper serve to draw attention to the oceanic dimensions of Australia as an ongoing colonial project. The protests discussed took place on the traffic island that serves as the foundation for Australia House in London, powerfully symbolic of Australia's position as the largest of a conglomeration of islands in the Pacific Ocean. Australia's historic attempts to establish a sub-empire of the British Empire in the Pacific have elicited ongoing colonial projects which continue to produce Australia as the place that it is today: a white island nation, reigning supreme in a brown region. From the carrying of a boat into the diplomatic territorial waters of Australia, to the projection of the faces of refugees who have died in offshore detention onto the walls of Australia House, to the amplified reading of the litany of horrific everyday incidents of abuse on Nauru, the actions both capture and subvert Australia's colonial deployment of the ocean. The protests draw attention to the violence Australia seeks to conceal in the distant islands of Manus and Nauru, and use the place of Australia House in the heart of London to "bring home" the historical colonial dimensions of Australia as a place today. As the colonial power's base in Britain, Australia House is of symbolic and strategic importance to the Australian national project. The protests discussed work to disrupt the business of the Australian High Commission by manoeuvring the physical space of and around Australia House such that it memorialises the racist violence those working inside seek to hide. In so doing, they also interrupt, if fleetingly, the place that is 'Australia' today.

Bibliography

Four Corners. 2016. Bad blood [Video file]. ABC News. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/4corners/bad-blood-promo/7346396 [accessed on April 9 2019]. [ Links ]

Anghie A. 1993. 'The heart of my home': colonialism, environmental damage, and the Nauru Case. Harvard International Law Journal 34(2): 445-506. [ Links ]

Asylum Seeker Resource Centre. 2018. Five more children evacuated off Nauru,seventeen remain. 19 November. Available at: https://www.asrc.org.au/2018/11/19/children-off-nauru/ [accessed on April 9 2019]. [ Links ]

Atfield C. 2014. Asylum seeker death: Family's organ donation wish unable to be granted. The Sidney Morning Herald. 6 September. Availabel at: https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/asylum-seeker-death-familys-organ-donation-wish-unable-to-be-granted-20140906-10dfc3.html [accessed onApril 9 2019]. [ Links ]

Australian Bureau of Statistics n.d. Australian expatriates in OECD countries. Available at: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@ nsf/7d12b0f6763 c78caca257061001cc588/3cf3335edc1a3f7fca2571b0000ea963!OpenDo cument#1%20Hugo%2C%20G%2C%20Rudd%2C%20D%20and%20Harris%2C%20K%2C [accessed on October 31 2018]. [ Links ]

Australian High Commission United Kingdom. n.d. The history of Australia House. Available at: http://uk.embassy.gov.au/lhlh/History.html [accessed on March 14 2018]. [ Links ]

Australian Nexus. n.d. Discover Australia in the UK. Availble at: http://www.ausnexus.co.uk/events/ [last accessed October 31 2018]. [ Links ]

Australian Treaty Series 1993 No 26. 1993. Agreement between Australia and the Republic of Nauru for the Settlement of the Case in the International Court of Justice concerning Certain Phosphate Lands in Nauru. Nauru, 10 August 1993. Department Of Foreign Affairs And Trade Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. [ Links ]

Banivanua-Mar T. 2007. Violence and colonial dialogue: the Australian-Pacific indentured labor trade. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [ Links ]

Boe A. 2005. Palm Island - Something is very wrong. Australian National University Public Lecture Series. 28 September. [ Links ]

BouCHANi B. 2017. I write from Manus Island as a duty to history. The Guardian. 5 December. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/dec/06/i-write-from-manus-island-as-a-duty-to-history [accessed on March 14 2018]. [ Links ]

Cherry D. 2006. Statues in the square: hauntings at the heart of empire. Art History 29 (4): 660-97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.2006.00519.x [ Links ]

Cressvvell T. 2004. Place: a short introduction. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Community Services (Aborigines) Act 1984 (Qld). [ Links ]

Doherty B. 2015. How Australia's immigration detention regime crushed Fazel Chegeni. The Guardian. 20 December. Availabel at: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2015/dec/21/how-australias-immigration-detention-regime-crushed-fazel-chegeni [accessed on March 14 2018]. [ Links ]

Doherty B and Davidson H. 2016. Reza Barati: men convicted of asylum seeker's murder to be free in less than four years. The Guardian. 19 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/apr/19/reza-barati-men-convicted-of-asylum-seekers-to-be-free-in-less-than-four-years [accessed on April 9 2019]. [ Links ]

Dunn KM, Klocker N and Salabay T. 2007. Contemporary racism and islamaphobia in Australia: racializing religion. Ethnicities 7 (4): 564-89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796807084017 [ Links ]

El-Enany N. 2017. Exclusion by default or design: asylum in the context of immigration control. In: Stevens D & O'Sullivan M (eds). Fortresses and fairness: states, the law and refugee protection. London: Hart. [ Links ]

El-Enany S. 2016. Nauru files reading [Video file]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/video/2016/dec/29/activists-read-the-nauru-files-outside-australia-house-in-london-video [accessed on April 9 2019]. [ Links ]

Fleay C, Cokley J, Dodd A, Briskman L and Schwartz L. 2016. Missing the boat: Australia and asylum seeker deterrence messaging. International Migration 54(4): 60-73. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12241 [ Links ]

FRX17 as litigation representative for FRM17 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection. 2018. FCA 63. [ Links ]

Green L. 2004. Bordering on the inconceivable: the Pacific solution, the migration zone, and 'Australia's 9/11'. Australian Journal of Communication 2004 31(1): 19-36. [ Links ]

Howard J. 2001. Australian federal election campaign launch speech by John Howard. Sydney, 28 October 2001. Available at: https://electionspeeches.moadoph.gov.au/speeches/2001-john-howard [accessed on April 9 2019]. [ Links ]

Keenan S. 2008. Australian legal geography and the search for postcolonial space in Chloe Hooper's The tall man: death and life on Palm Island. Australian Feminist Law Journal 30 (2009): 173-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/13200968.2009.10854423 [ Links ]

Klein N. 2014. This changes everything. London: Penguin. [ Links ]

Laughland O. 2014. Asylum seeker declared 'brain dead' after leaving Manus Island. The Guardian. 3 September. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/03/asylum-seeker-declared-brain-dead-medical-evacuation-manus-island [accessed on April 9 2019]. https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691161051.003.0007 [ Links ]

Laughland O and Nissi D. 2014. Asylum seeker's family mourn 'sensitive, lovable' son declared brain dead. The Guardian. 4 September. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/04/asylum-seekers-family-mourn-son-declared-brain-dead [accessed on April 9 2019]. https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691161051.003.0007 [ Links ]

London remembered refugees who've died in inhuman Australian detention. 2016 . Huck. 22 April. Availale at: http://www.huckmagazine.com/perspectives/activism-2/london-remembered-refugees-whove-died-inhumane-australian-detention-last-night/ [accessed on April 9 2019]. [ Links ]

Love Makes a Way. 2016. lovemakesaway.org.au/event/naurufiles-reading-vigils/ [accessed om March 14 2018]. [ Links ]

Mabo v The State of Queensland (No 2) (1992) 1 CLR 175. [ Links ]

Massey D. 1993. Power-geometry and a progressive sense of place. In: Curtis B, Bird J, Putnam T, Robertson G and Lisa Tickner (eds). Mapping the futures: local cultures, global change. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Margry PJ and Sanchez-Carretero C. 2011. Grassroots memorials: the politics of memorializing traumatic death. Oxford: Berghahn Books. [ Links ]

Mawani R. 2016. Law, settler colonialism, and the forgotten space of maritime worlds. Annual Review of Law and Social Science 12(1): 107-131. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102612-134005 [ Links ]

McDougall S, Queensland, Department of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Policy, Palm Island Aboriginal Shire Council and Caxton Legal Centre. 2006. Palm Island: future directions: resource officer report. Brisbane. Department. of Communities. Available at: http://nla.gov.au/nla.arc-68762 [accessed on April 9 2019]. [ Links ]

Migration Act 62 of 1958 (Cth). 1958. Federal Register of Legislation. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Series/C1958A00062/Amendments [accessed on April 9 2019]. [ Links ]

Migration Amendment (Unauthorised Maritime Arrivals and Other Measures) Act 35 of 2013 (Cth). 2013. Federal Register of Legislation. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Series/C1958A00062/Amendments [accessed on April 9 2019]. [ Links ]

Morris J. 2003. The spaces in between: American and Australian interdiction policies and their implications for the refugee protection regime. Refuge 21(4): 51-62. [ Links ]

Om J. 2014. Hamid Khazaei: Rare bacterial infection killed Iranian asylum seeker detained on Manus Island. ABC News. 3 October. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-10-04/iranian-asylum-seeker-died-of-rare-infection/5790364 [accessed on April 9 2019]. [ Links ]

Parkin I. 2016. World Refugee Day Protest, Austalia House [Video file]. 22 June. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3AZJd3stk9o [accessed onApril 9 2019]. [ Links ]

Pearson E. 2014. Cambodia is not safe for refugees. Human Rights Watch. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/05/22/cambodia-not-safe-refugees (accessed on November 20 2018). [ Links ]

Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. 1991. Regional report of inquiry into Queensland, Appendix 1(a): The aboriginals in colonial society 1840-1897. Available at: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/other/IndigLRes/rciadic/regional/qld/ch5.html#Heading22 [accessed on October 31 2018]. [ Links ]

Powell G, Ryan B and Donald P. 2015. Christmas Island detention centre 'calm' after 'stand-off' with authorities following refugee's death: Immigration Department. ABC News. 12 November. www.abc.net.au/news/2015-11-09/christmas-island-calm-after-stand-off-immigration-department/6922866 [accessed on March 14 2018]. [ Links ]

Storr C. 2018. 'Imperium in imperio': Sub-imperialism and the formation of Australia as a subject of international law. Melbourne Journal of International Law 19(1): 335-368. [ Links ]

Taylor S. 2005. The Pacific solution or a Pacific nightmare? The difference between burden shifting and responsibility sharing. Asian-Pacific Law and Policy Journal 6(1): 1-43. [ Links ]

Tlozek E. 2016. Reza Barati death: Two men jailed over 2014 murder of asylum seeker at Manus Island detention centre. ABC News. 19 April. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-04-19/reza-barati-death-two-men-sentenced-to-10-years-over-murder/7338928 [accessed on April 9 2019]. [ Links ]

WOLFEP.2006.Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide Research 8(4): 387-409. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240 [ Links ]

First submission: 31 January 2018

Acceptance: 10 January 2019

1 Between 1999 and 2003, 33.4% of the Australian diaspora lived in the UK, more than any other OECD country (Australian Bureau of Statistics n.d.).

2 See Australian Nexus: discover Australia in the UK. Availble at: http://www.ausnexus.co.uk/events/ [last accessed 31 October 2018].

3 See Community Services (Aborigines) Act 1984 (Qld).

4 Christmas Island is an "excised offshore place" pursuant to the Migration Amendment (Excision from Migration Zone) Act 2001. So although still part of Australia, any non-citizen without a visa who arrives there will be taken to have not reached Australia for the purposes of migration law, and instead removed to Manus or Nauru. See Taylor 2005.

5 For full details on the status of foreign missions, see the 1962 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations.

6 The video is available to watch online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3AZJd3stk9o

7 See note 1 above.

8 Authors' interview with participant, August 2016.