Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

On-line version ISSN 2413-9467

Print version ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.8 n.1 Stellenbosch 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2022.v8n1.af3

SPECIAL COLLECTION (WE ARE FAMILY CONFERENCE)

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2022.v8n1.af3

Mary of Nazareth as leader? A feminist exploration of Early Christian art

Ninnaku Oberholzer

University of Pretoria, South Africa. ninnakuo@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Traditionally women are valued for their ability to bear children and often regarded as mere vessels for reproduction. This patriarchal view of women is notably encountered in the portrayal of the Virgin Mary, who throughout history has been regarded as a "vessel" for God's message and therefore portrayed as a perpetual virgin, shrouded in servanthood and suffering. The aim of this article is to distinguish Mary from this tradition and the way the early church perpetuated the patriarchal custom of equating womanhood with motherhood. Instead, an exploration of Mary as occupying a leadership role is offered. This exploration will take place by way of a consideration of early Christian art that depicts Mary as a figurehead of the early church - which indicates that this depiction predates Mary's assigned role as pious mother and the "vessel" of God. Ultimately, this contribution critiques the manner in which womanhood and motherhood are equated with one another and highlights the embeddedness of patriarchal influences in Christianity's traditions.

Keywords: Early Christian art; Mariology; feminist interpretation; motherhood; womanhood

1. "There's something about Mary ..." - but what is it?

The traditional image of the "Virgin Mary" as mother is well known in Christianity. Images and symbolism surrounding Mary as the "one who gave birth to God" influenced Christian doctrine about Jesus Christ (Van der Kooi & Van den Brink 2017:408; cf. McGrath 2011:39-40). The symbolism surrounding the "Virgin Mary" has also had an influence on the perception of women in society. As such, in Christianity, Mary is often depicted as a symbol that represents women. She is known as the Virgin Mother, Second Eve, as Theotokos (mother of God), Immaculate (based on her own immaculate conception), and Semper Virgo (perpetual virgin) (Price 2007:62; Warner 2016:242). In Catholic theology Mary's role has been significant for centuries - she is the human mother of Jesus, a perpetual virgin who rectified the sins of Eve and at the same time is exempt from sin. In Protestant theology, Mary has occupied a more minor position, however, the remnants of her pious and submissive representations are still found within Protestant church culture and ideas surrounding women. Mary is a symbol of what a woman should be - a good mother.

This article, however, explores a different Mary - one which is more hidden and who is often ignored by tradition today based on her limited appearance in New Testament scripture (Malina 2002:97). Outside of the New Testament canon can be found a world of early Christian art which reflected societal views and practices not directly addressed in text. In this world of early Christian art, Mary of Nazareth1 is celebrated as the first disciple, she is portrayed as a high priest and bishop, and she is viewed as a leader of the early Christian movement. Increasingly, contemporary scholarship in the fields of art history and Mariology have started to highlight these other roles of Mary. It is argued that Mary's role as leader, at least via an artistic lens, is uncontested. This evidence separates her from her traditional role as mother. Instead, Mary as a leader, as depicted in early Christian art, introduces her as a symbol of a different type of womanhood, one which was hidden and discouraged. Unearthing (and unhiding) depictions of Mary that portray her and her influence in all of its diversity, is necessary and one could even say, a matter of justice.

In this contribution, the interpretation of Mary's roles and the possible expansion thereof will be considered by a proverbial "excavation" of early Christian art which depicts Mary in a variety of ways. The contribution will specifically juxtapose the so-called "traditional" role of Mary as mother, with Mary as leader. This relates specifically to how Mary is depicted in early Christian art2 wearing different types of clothes, her body posture, gestures, and facial expressions. The history of interpretation surrounding these depictions will be explored and deconstructed, in order to suggest their possible contribution to feminist scholarship, specifically related to the role of religious symbolism in the construction and justification of gender roles. For many scholars working in the field of feminism, such as Johnson (Johnson 1984; 1985a; 1985b), Ruether (1977; 1981; 1983; 1985), Schussler Fiorenza (1979; 1994), Daly (1985a; 1985b), and Warner (2016), Mary has been a point of departure for scholars and offers the opportunity for women to reclaim and reflect on the female subject whilst speaking about the body in the context of women's lives (Maeckelberghe 1991:73, 75).

Whilst the complexity of Mary as a Christian figure is acknowledged and admittedly there is a difficulty of only focusing on certain aspects of her symbolism, the focus for this contribution remains on the core feminist argument for a re-evaluation of Mary - exploring her oppressive virginal image and her liberating leadership nature.3 Therefore, this article will explore the juxtaposition of Mary in terms of her motherhood role and leadership role by firstly focusing on her representations as the Second Eve and a vessel for the Triune God whilst secondly bringing forth the images of her in history where she is represented as a Church leader in early Christian art. This aims to establish how Mary as a mother replaced the understanding of Mary as a leader through the help of early Christian art, tracking and highlighting the changes in her popular image through art which in turn greatly influenced the popular understanding of Mary.

2. Mary as mother

The most popularly known symbol of Mary throughout history is the virgin mother of Jesus - in art represented as the well-known "Madonna and child" image. This motherly Mary with an infant Jesus on her lap is often the topic of scholarship and has led to many cross-disciplinary investigations. In anthropology the mother Mary as the "hidden goddess of Christianity" becomes a popular theme based on her likeness to fertility goddesses (Mulack 1985; Carroll 1986). In other disciplines, like psychology, Freudian and Jungian scholars interpret the popular mother image as a human "longing for a mother" or a step in "development of self-awareness" (Kassel 1983; Rancour-Laferriere 2018). Whilst there is no scarcity in the study of Mary in broad scholarship, these studies have a primary focus on motherhood, the relation between mother and son, by extension Mary's virginhood, and the influence early fertility cults had on her portrayal in early Christianity.

From a theological standpoint the interest in Mary has most often not been different from the focus themes of other study disciplines, with the importance of her motherhood not being understated in terms of the development of Christology and the understanding of redemption.4 Mary as mother in Christianity has a long history of interpretation which stretches to the Old Testament writings. It is through interpretation of Old Testament prophecies and writings that church fathers and early theologians used the symbolism of the day to reappropriate certain ideas to Mary and her motherhood in order to create images of her which symbolizes her role in Christology. However, although "motherhood" is the main way in which Mary is portrayed, this "motherhood" is accompanied and inherently linked to ideas surrounding the female body, its function and use, and its sexuality. In order to effectively explain this link, two main points of departure will be used, namely, discussing Mary as the New Eve in order to understand her sexuality, submission, and obedience as a "good woman", and secondly viewing instances of Mary where she is considered important purely because of her role as "vessel" and valued because of her womb.

2.1 Mary the "Second Eve"

Marian theological interpretation, which influenced artistic representation of the later ages and in turn influenced popular thought, heavily rests on previous centuries' interpretations of Lukan scripture. Focus is placed on the interpretations of Luke 2:19 (But Mary treasured up all these things and pondered them in her heart) and Luke 2:51 (... But his mother treasured all these things in her heart), as well as John 2:1-11, their respective parallels with Genesis 3, and interpretations of these scriptures made by early Church Fathers - especially Irenaeus.

Firstly, the Annunciation scene in Luke is often noted to be the only instance in the Gospels where Mary plays a role in her own pregnancy and, most notably, is seen as accepting the will of God and proclaiming to be his servant - a translation to be contested later on. According to Maunder (2019:55) these two verses in Luke where Mary "ponders" and "keeps these things in her heart" have been taken in early theological interpretation to represent two main arguments regarding Mary's autonomy. Firstly, Mary's acceptance of the will of God and her willingness to conceive, give birth to, and raise Jesus, and secondly, to be by his side at his crucifixion (Gaventa 1995:54). Through Mary's "yes" to receiving the Spirit, it is accepted that she is faithful to God whilst simultaneously fulfilling the oracle found in Genesis 3:14-15. In these verses God speaks directly to the snake and curses it for its influence on Eve and Adam, promising that their descendants will crush the head of the snake with their heel. In both Jewish and Christian interpretation, Jesus is the one who enters the cosmic battle with the devil (interpreted as the snake) and ultimately defeats it through his death and resurrection (Pitre 2018:21). Through Mary's "yes" and her obedience to God, she fulfils the curse directed to the snake in Genesis 3:14-15 and solidifies the events to come.

Mary's motherhood role also appears strongly in the narrative of the Wedding of Cana found in John 2:1-11. Being the only instance in John where Mary appears, the narrative of the Wedding of Cana is important in the establishment of Mary's role as mediator and functions as a further link with Eve featured in Genesis 3. This is based on two arguments primarily. Firstly, Crossan (1967:57) argues that Jesus uses the term gynê (woman) to refer to his mother - a term which some scholars interpret as defiance - whilst the same term is used to reference Eve in Genesis before she is officially named, and (2) Mary's insistence of Jesus to perform his first miracle before his time in parallel with Eve's insistence of Adam to eat the fruit (Crossan 1967:57; Brown 1970:109; Pitre 2018:27).

Based primarily on these four textual instances influential early Church Fathers who, through interpretations of the abovementioned texts and their own theological teachings, established concretely the connection between Mary and Eve. Irenaeus writes in Against Heresies referring to Mary:

What is joined together could not otherwise be put asunder than by inversion of the process by which these bonds of union had arisen; so that the former ties be cancelled by the latter ... It was that the knot of Eve's disobedience was loosed by the obedience of Mary. For what the virgin Eve had bound fast through unbelief, this did the virgin Mary set free through faith. (Against Heresies, III.22.4, A.D. 180)

For just as [Eve] was led astray by the word of an angel, so that she fled from God when she had transgressed His word; so did [Mary], by an angelic communication, receive the glad tidings that she should sustain God, being obedient to His word. And if the former did disobey God, yet the latter was persuaded to be obedient to God, in order that the Virgin Mary might become the patroness of the virgin Eve. (Against Heresies, V.19.1, A.D. 180)

Irenaeus draws a strong parallel between Mary and Eve, using the one woman as a symbol of disobedience towards God and the other as a perfect example of obedience, recapitulating the wrongs of Eve through accepting her position as ultimate mother of the redeemer, or new Adam. This sentiment was shared by other writers of the time as well, such as Justin Martyr (Dialogue with Trypho 100), Epiphanius of Salamis (Panarion 78.1719), and Theodotus of Ancyra (On the Mother of God and on Nativity), and continued well into 5th century interpretations (Miller 2005:291-295; Pitre 2018:32). Therefore, both Shoemaker (2016:44, 167) and Pitre (2018:32) argue that for Christians in antiquity it was well understood that whilst Eve through disobedience and sin is the mother of the old life, Mary, through obedience and immaculate conception, is sin free and the mother of the new life.

The symbolism of Mary as a "new" or "second" Eve was discussed and understood by early Fathers, however, McHugh (1982:17) quite rightly points out that the term "Second Eve" or "New Eve" was never actually written or used by these early authors. Whilst this is most surely an important point for discussion,5 this nevertheless does not change the fact that the theological motive has been repeated throughout centuries of theological discussion and has been imbedded in popular memory through the portrayals of Mary in Christian art. Most notably Mary as the new Eve is presented popularly by Paolo di Giovanni Fei's 14th century Madonna and Child Enthroned (Figure 1). Here Mary is understood and represented as the second Eve in the form of a mother cradling a breastfeeding Jesus seated above Eve and a snake (Gaventa 1995:80, Saylors 2007:132, Pitre 2018:32). From Fei's work the contrast between Mary and Eve seems clear - where Mary is dressed "appropriately" with head covering and seated with baby Jesus who is breastfeeding, head tilted and eyes averted from the viewer in what is often described as a demeanour of submission, Eve is shown in the opposite light with robes that are see-through and appearing naked, a reclined posture which is often associated with her sinfulness and seduction of Adam, and facing the viewer directly.6This juxtaposition of Mary and Eve's bodies as a theme within Christian art can be found throughout centuries with varying adaptions, however, according to Williamson (1998:125) the pairing is understood to remind the viewer of Mary as the Second Eve and, through the presence of Jesus breastfeeding and the often noticeable differences between the portrayals of each woman's breasts, places importance on the redemption of Eve's sins through Mary's motherhood. Therefore, Mary as a sin free and obedient woman gave the chance for not only all of humanity to be redeemed, but all women, through her motherhood.

2.2 Mary as a vessel

Whilst Mary's portrayal as the "Second Eve" brings forth notions of obedience, submission, and redemption of Eve through motherhood, this motherhood also has a second layer of understanding in reference to Mary's sexuality, body, and virginity. What makes Mary such an interesting figure to study is also what makes her so perplexing and contradicting - she is understood and portrayed as a mother, but at the same time she is hailed for her virginity. The emphasis on an "obedient sin free" mother echoed what 1st century Syriac Christians believed regarding the emphasis on virginity above all virtues and chastity as the way to combat sin (Rubin 2009:23, 34-36). In turn, this greatly influenced early Christian thought surrounding Jesus' conception, with Syriac authors preferring the idea that the spirit entered Mary herself rather than her body - that is to say, conception took place through Mary's ear rather than her body. Whilst this ideological formation took place during the 1st century, this greatly influenced ideas surrounding Mary's virginity and women's sexual purity, giving rise to the interesting depictions, appearing in mosaics from the period after the council of Nicea (325 C.E.), of Mary conceiving through the Holy Spirit entering her ear (Figure 2). Rubin (2009:36) notes that this is a further link cementing Christian ideas of Mary as the new "pure" Eve - for as Eve had listened to the serpent and sinned, Mary received Jesus through her ear but remained "pure".

Whilst these images of Mary conceiving through her ear in order to retain her virginity removes her from any notions of sexual acts, the separation of Mary's body from her individual personhood can be taken one step further when viewing ritual containers in the shape of Mary's body which represent her as mother. Much like the idea that Mary as the New Eve comes from Old Testament interpretations, so did the idea of Mary where she is understood as a vessel for Jesus - through her pregnancy and motherhood she becomes the "house of God", the "second tabernacle", the "blessed chalice", and the "golden jar of manna" to name a few (Rancour-Laferriere 2018:46). These containers which started to appear in the Byzantine period were used in the West to contain the consecrated eucharistic host and formed part of the priest's transubstantiation ritual (Rancour-Laferriere 2018:46; Evangelatou 2019:79-80).

... the case (capsa) in which the consecrated hosts are preserved signifies the body of the glorious Virgin (corpus Virginis gloriose), about whom is spoken in the Psalm, Ascend, O Lord, to your rest, You and the ark of your sanctification (Ps 131:8). The case is sometimes made of wood; sometimes of white ivory; sometimes of silver; sometimes of gold; sometimes of crystal; and according to these diverse varieties and properties the different graces of the Body of Christ (corporis Christi) itself are expressed (Durand 2007:39).

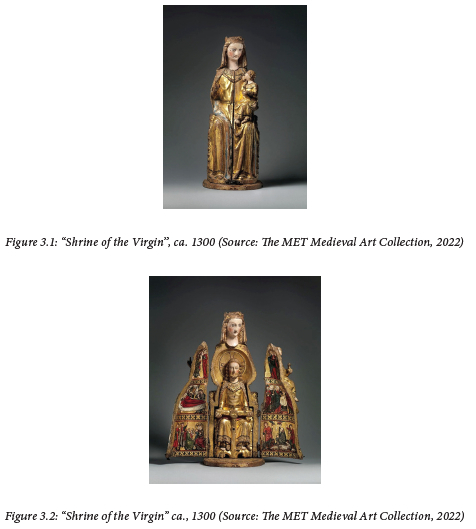

Whilst this case which preserves the consecrated host came in different formats and developed over time, the late twelfth century brough sculptural containers of Mary. These vessels, an example known as the "Shrine of the Virgin" (Figure 3.1 and 3.2), takes the form of a seated Mary breastfeeding Jesus and once Mary's body is opened, reveals the Mercy-Seat Trinity - a sculptural representation of the Trinity wherein God the Father holds the crucified Son (now removed) and the Spirit hovers nearby in the form of a dove. Whilst this image contains a host of theological issues7, the Shrine of the Virgin represents the theological idea of God's predestined actions to save humanity and Mary's role in redemption as mother.

From scripture and accepted scriptural interpretation of Luke's Annunciation, Mary's role in Christological and Salvation development is understood. However, it is because of strong Syriac influences, cultural patriarchal focus on purity, and a historical aversion to the female body that we find sculptures such as the Shrine of the Virgin where Mary is reduced to an "untarnished vessel of virginity" (Saylors 2007:120, Rubin 2009:44). An image which feminist scholars have long since argued is an unhealthy feminine ideal of obedience and self-sacrifice (Saylors 2007:109, Kateusz 2019:1).

3. Mary as leader

Looking at the brief overview of Mary's imagery and the way in which she has been primarily represented, great emphasis was placed on her body, virginity, obedience, and submission to God to strengthen the symbol of her as the ideal mother, reversal of Eve's sin, and vessel of Christ, however, this was not the only image, nor the most popular, of Mary. Whilst some of these images have disappeared, there still exists in art a glimpse of a different image of Mary known as a leader of the early Christian movement and the first disciple - an image which is not of a mother and cannot be altered by interpretations of texts.

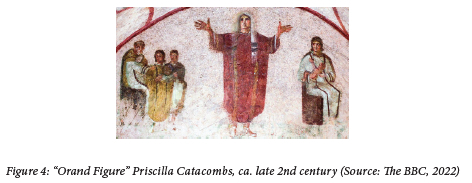

In trying to piece together an altogether different Mary than previously discussed, once again we turn to interpretations of Mary which originate from the Old Testament. The most popular and perhaps most well-known images depicting a woman in early Christian art (dating between 200 C.E. and 600 C.E.) shows a woman in a liturgical position known as the orant woman (Figure 4). This gesture, with arms outstretched, can be traced back to the Old Testament prototype of the Eucharist - the daily offerings of the Evening Sacrifice in the Jerusalem temple, and was also associated in art with leaders of Israel such as Moses and Abraham (Kateusz 2019:70). Whilst some may argue that the pose is simply one of prayer, there are numerous textual evidence pointing to the pose as being one of liturgical service where the priest raises their arms. Psalm 141:2 explains; "Let the raising of my hands be as the evening sacrifice", whilst Kateusz (2019:70) also notes that in the 4th century, Chrysostom similarly wrote, "I am raising up my hands as the Evening Sacrifice". Kateusz (2019:71) argues that with the combined textual and artefactual evidence across both Jewish scripture and early Christian liturgy, the meaning behind the pose does not only reference prayer, but also a position of leadership for the figure involved. This is also supported by scholars such as Shoemaker (2016) and Pelikan (1996; 2005) who have extensively studied the veneration of Mary outside of early orthodox practices. This greatly impacts how we understand depictions of Mary with her arms raised in early Christian thought and the subsequent altering of her body position and physical use of her body as containers in years to come.

Whilst there are an abundance of solo images portraying women in this liturgical position, it is depictions we find in the Rabbula Gospels (Figure 5) that gives a glimpse into Mary as an early symbol of leadership. Here we find a scene of Mary amongst the twelve male apostles which portray her as the focal point with her arms raised once again. Kateusz (2019:80) notes that the fact she is portrayed with a powerful posture, direct gaze, and slightly taller than her counterparts on either side signify her headship. Furthermore, she is spiritually elevated by the fact she is flanked by archangels and, apart from them and Jesus, she is the only one with a halo. This depiction of Mary, as a leader of the disciples, became increasingly popular very early on and spread throughout the Mediterranean, with Kateusz (2019:74) noting 6th and 7th century artifacts throughout the region depicting the image. Keeping in mind the same texts as earlier, many scholars have argued for Mary's discipleship on the grounds of Luke's Annunciation narrative. Firstly, Gaventa (1995:54) turns to Luke 1:28 where the angel greets Mary with "you have found favour with God" in order to showcase Mary's importance to God and underscores this fact with Mary's consent (including reference to the previously discussed Luke 2:19, 51) and the self-appointed title doulë kyriou (slave of the Lord) in Luke 1:38. Although translators most often opt for a translation of "servant" rather than "slave" in this case, Gaventa (1995:54) argues strongly that to translate "servant" is to misrepresent the fact that Mary was chosen by God to serve Him, rather than someone who chooses to serve. The final part of Luke 1:38 ties in with this, with Mary agreeing genoito moi kata to rhëma so (let it be done to me according to your word), referring to the fact she has been chosen by God and, much like other later apostles, she has not chosen her own role but does consent to it. With this, Mary's compliance does not become a model for how women should accept motherhood, but she becomes a model that all discipleship is based on (Gaventa 1995:55; Maunder 2019:54-55).

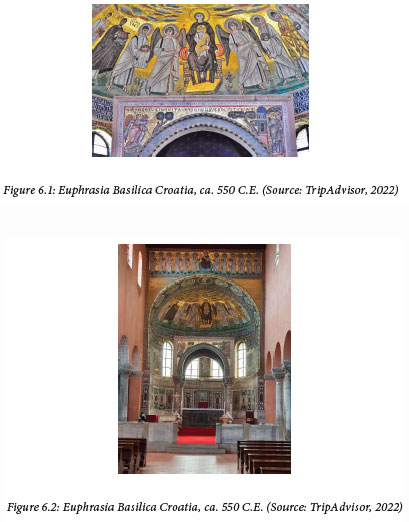

Another suggestion of Mary's leadership which is rooted in art can be seen in early basilica's where Mary is portrayed as wearing the episcopal pallium. These images are as old as any of the portrayals of men wearing the garment, dating to the mid-6th century. Most notably there are two instances of Mary in prominent positions shown with these garments. Firstly, in the Euphrasia Basilica (Figure 6.1 and 6.2) Mary is placed directly above the episcopal throne behind the altar, in the middle of the altar apse (Kateusz 2019:83). Here the episcopal pallium with the cross is seen hanging just below the hem of her maphorion. She is also flanked by 12 women, identified as Thecla, Perpetua, Susanna, Justina, Eugenia, Euphemia, Agatha, Valeria, Felicitas, Cecilia, and Basilissa, all who are still recognized today as female leaders in the early church movement and appear in letters by Paul.

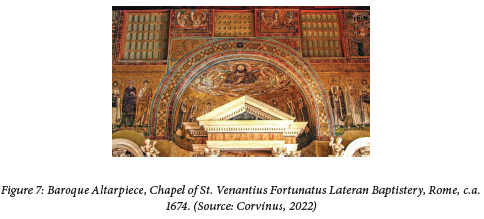

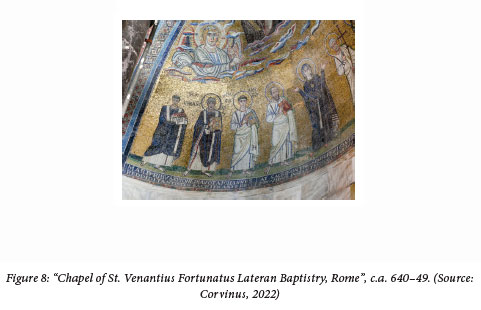

The second image (Figure 7) of Mary is found in the mosaic altar apse of the Lateran Baptistery Chapel in Rome, the oldest baptistery in the world completed by Pope Theodore I between 642-649 C.E. Situated right above the altar, Kateusz (2019:86) argues that Mary would have been seen as the Eucharistic leader of the sixteen men. Here once again Mary is seen wearing the episcopal pallium with the red cross. This clothing, along with Mary's liturgical outstretched arms, the subordinate position of the men, and her position as mediator right beneath Jesus, all suggest that early congregants would have understood Mary as the chief officiant of the Eucharist.

4. Feminist considerations

It is the controversy surrounding this last image of Mary which is fitting for the demonstration of the analyses today. When visiting the Lateran Baptistery today, this mosaic of Mary as liturgical leader is completely hidden behind a huge baroque altar piece (figure 8). Whilst it still features Mary in the centre of the altar, the image is now one of Madonna and child. Kateusz (2019:74-75) argues that just as some texts have been redacted to reduce the role of Mary and other women as leaders within the early Christian movement, so to have artists slowly altered Mary throughout the centuries to the symbol of motherhood she is today. Kateusz (2019:75) argues that instead of continuing the portrayal of Mary with liturgical outstretched arms, episcopal pallium, and an erect posture and strong gaze, artists began to depict her semi-profile from the side, with lowered hands, seated the majority of the time, and with a down casted gaze.

To be clear, the issue surrounding Mary is not that she is a mother, but rather the framing of motherhood as a submissive role and using her body to serve a system where she is relinquished from her liturgical role and leader of the early church. She is merely transformed into a symbol which needed to redeem the sins of Eve and be submissive and obedient to the will of God. These prescriptions and definitions of "woman" belong to the historical essence of what it meant to be a woman.

Referring to micro-structures of power it can be witnessed through art how Mary was physically altered by the dominating male hierarchy of the time -her leadership icons replaced by motherhood images, not being featured alone but always with Jesus or a male counterpart, her arms systematically lowered to her sides, head bowed in submission, and eyes averted to the ground (Figures 4, 7, and 9) - as suggested by just a few examples. According to Botha (2000:2) these gender related micro-structures of power in history have contemporary influences and still promote traditional gender roles and social behaviour.

5. A foundation for further excavation about Mary

From the discussed overview of Mary in early Christian art it is clear that the goal is not to argue what Mary is or was, a pawn of the later church to show how women should be virtuous and submissive or a true leader of the earliest Christian movements. It is quite clear that she was a symbol of both. Her changing symbolism and portrayal allow a line of questioning relating to what Mary might mean for an understanding of womanhood in today's context and what implications this might have for dying patriarchal religious communities. Can she be separated from her patriarchal images as an "untarnished vessel", a mere body which was used to house Christ, and a symbol of historical contextual rejection of sexuality, and become a symbol in today's context which features her historically hidden nature of leadership - becoming a re-analysed, positive feminist and alternative symbol within the church which shows room for more inclusion and equality. Mary of Nazareth and the symbols she portrays is a reminder that it is "my"8 responsibility as woman to change the rules of discourse that have been, until now, responsible for the continued determination of what a woman can be - either a mother or a leader - one or the other. Quoting from Braidotti (1989:69); "I have paid in my very body for all the metaphors and images that our culture has deemed fit to produce of woman".

Bibliography

Botha, P.J.J. 2000. Submission and Violence: exploring gender relations in the first-century world. Neotestamentica, 34(1). [ Links ]

Braidotti, R. 1989, The Politics of Ontological Difference. In T. Brennan (ed.). Between Feminism and Psychoanalysis. Routledge, London: New York. 62-72.

Brown, R.E. 1970. The Gospel according to John. New York: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Carroll, M.P. 1986. The cult of the Virgin Mary: psychological origins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Crossan, J.D. 1967. The Gospel of Eternal Life: Reflections on the Theology of St. John. Milwaukee: The Bruce. [ Links ]

Daly, M. 1985a. Beyond God the Father: toward a philosophy of women's liberation. Boston: Beacon Press. [ Links ]

Daly, M. 1985b. The church and the second sex. Boston: Beacon Press. [ Links ]

Durand, G. 2007. The Rationale Divinorum Officiorum of William Durand of Mende: A New Translation of the Prologue and Book One. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Evangelatou, M. 2019. Krater of Nectar and Altar of the Bread of Life: The Theotokos as Provider of the Eucharist in Byzantine Culture. In T. Arentzen & M. Cunningham (eds.). The reception of the Virgin in Byzantium: Marian narratives in texts and images. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 77-119. [ Links ]

Gaventa, B.R. 1995. Mary: glimpses of the mother of Jesus. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. [ Links ]

Jensen, R.M. 2000. Understanding Early Christian Art. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Johnson, E.A. 1984. Mary and Contemporary Christology: Rahner and Schillebeeckx. Eglise et Theologie, 15:155-182. [ Links ]

Johnson, E.A. 1985. The Marian Tradition and the Reality of Women. Horizons, 12(1):116-135. [ Links ]

Johnson, E.A. 1985a. The Symbolic Character of Theological Statements about Mary. Journal of Ecumenical Studies, 22(2):312-335. [ Links ]

Kassel, M. 1983. Mary and the Human Psyche Considered in the Light of Depth Psychology. Concilium, 160:74 -82. [ Links ]

Kateusz, A. 2019. Mary and early Christian women: hidden leadership. Cham, Switzeland: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Kooi, C. van der & Brink, G. van den 2017. Christian dogmatics: an introduction. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Letherby, G. 2020. Gender-Sensitive Method/Ologies. In D. Richardson & V. Robinson (eds.). Introducing gender and women's studies, Fifth edition. London: Macmillan international Higher Education. 58-75. [ Links ]

Malina, B.J. 2002. The Social World of Jesus and the Gospels. London; New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Maunder, C. 2019. Mary and the Gospel Narratives. The Oxford handbook of Mary, Oxford handbooks, First edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 110-126. [ Links ]

McGrath, A.E. 2011. Christian Theology: An Introduction, 5th edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

McHugh, 1982 The Second Eve: Newman and Irenaeus. Way Supplement, 45:13-21. [ Links ]

Miller, P.C. 2005. Women in Early Christianity: Translations from Greek Texts. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press. [ Links ]

Mulack, C. 1985. Maria. Die Geheime Gottin im Christentum. Stuttgart: Kreuz Verlag. [ Links ]

Nichols, A. 2015. There is no rose: the Mariology of the Catholic Church. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Pelikan, J. 1996. Mary through the centuries: her place in the history of culture. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Pelikan, J., Flusser, D. & Lang, J. 2005. Mary: images of the mother of Jesus in Jewish and Christian perspective. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Pitre, B.J. 2018. Jesus and the Jewish roots of Mary: Unveiling the Mother of the Messiah. New York: Image. [ Links ]

Price, R. 2007. Theotokos: The Title and its Significance in Doctrine and Devotion. In T. Beattie & S.J. Boss (eds.). Mary: The Complete Resource, 1. London: Continuum. 56-73. [ Links ]

Rancour-Laferriere, D. 2018. Imagining Mary: a psychoanalytic perspective on devotion to the Virgin Mother of God. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

Rubin, M. 2009. Mother of God: a history of the Virgin Mary. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Ruether, R.R. 1977. Mary, the feminine face of the Church, 1st edition. Philadelphia: Westminster Press. [ Links ]

Ruether, R.R. 1981. To change the world: Christology and cultural criticism. London: SCM Press Ltd. [ Links ]

Ruether, R.R. 1983. Sexism and God-talk: toward a feminist theology. Boston: Beacon Press. [ Links ]

Ruether, R.R. (ed.) 1985. Womanguides: readings toward a feminist theology. Boston: Beacon Press. [ Links ]

Saylors, D.C. 2007. The Virgin Mary: A Paradoxical Model for Roman Catholic Immigrant Women of the Nineteenth Century. Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council, Spring.

Schussler Fiorenza, E. 1979. Feminist Spirituality, Christian Identity, and Catholic Vision. In C.P. Christ & J. Plaskow (eds.). Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion. New York: Harper & Row. 136-148, [ Links ]

Schüssler Fiorenza, E. 1994. In memory of her: a feminist theological reconstruction of Christian origins. 10th anniversary edition. New York: Crossroad. [ Links ]

Shoemaker, S.J. 2016. Mary in early Christian faith and devotion. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Warner, M. 2016. Alone of all her Sex: The Myth and Cult of the Virgin Mary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Artworks

di Buoninsegna, D. ca. 1290-1300, Madonna and Child. [Tempera and gold on wood]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. [Online]. Available: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/438754 [Accessed: 2022, March 23].

di Giovanni Fei, P. ca. 1385-90, Madonna and Child Enthroned. [Tempera on wood, gold ground]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. [Online]. Available: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/458963 [Accessed: 2022, March 23].

Torriti, J. 1295, Annunciation to Mary. [Mosaic]. Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome. [Online]. Available: https://www.wga.hu/html_m/t/torriti/mosaic/5scene1.html [Accessed: 2022, March 23].

Unknown, ca. 360-350, The Orans Figure. [Relief]. Santa Priscilla

Catacombs, Rome. [Online]. Available: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20150224-the-secrets-of-the-catacombs [Accessed: 2022, March 23].

Unknown, ca. 550, Mary with Episcopal Pallium and Jesus. [Mosaic]. The Euphrasia Basilica, Croatia. [Online]. Available: https://www.tripadvisor.com/Attraction_Review-g303829-d319594-Reviews-Euphrasius_Basilica-Porec_Istria.html [Accessed: 2022, March 23].

Unknown, 586, Ascension from the Rabbula Gospels. [Manuscript Illustration]. Florence, Italy. [Online]. Available: https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=53846 [Accessed: 2022, March 23].

Unknown, ca. 650, Mary with Episcopal Pallium. [Mosaic]. The Chapel of Saint Venantius Lateran Baptistery, Rome. [Online]. Available: https://corvinus.nl/2018/01/29/rome-san-giovanni-in-fonte/ [Accessed: 2022, March 23].

Unknown, ca. 1300, Shrine of the Virgin. [Oak, linen covering, polychrome, gilding, gesso]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. [Online]. Available: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/464142 [Accessed: 2022, March 23].

1 Important to note is that throughout this article there is a deliberate change in the use of language to not refer to Mary as "the mother of Jesus" or as "the Virgin Mary", but to also include the title "Mary of Nazareth". In doing so an effort is undertaken to separate Mary from traditional images and introduce a focus on her identity as an individual figure.

2 The term "early Christian art" within the context of this article is not resigned to referring to a specific period of Christian art, but rather refers to the broad artistic, namely paintings, frescoes, and mosaics, and physical religious elements which span over a number of centuries and are found in a variety of geographical locations. The selection found here serves as examples of themes relating to Mary. For a complete understanding of the term "early Christian art" related to a period of time see Jensen (2000).

3 This forms part of my broader Master's work where I analyse Mary using Christian art in terms of the patriarchal images surrounding her sexuality, virginity, and the use of her body in theology.

4 See Nichols (2015:23-44, 67-88, 111-130) and Pitre (2018:98-115). Alternatively see Rancour Laferriere (2018:286-289) for an introductory discussion on Mary as co-redeemer alongside Christ.

5 This point of discussion can be followed further in McHugh (1982).

6 These models of representation, both for Mary and Eve, which include posture and clothing, are set within the artistic tradition of the 13 century and are quite ordinary depictions which follow the trend of the time and constantly repeated by other artists. A greater discussion of the topic of representation of both Mary and Eve can be found in Williamson (1998).

7 For a discussion on theological issues see Rancour-Laferriere (2018:46-50).

8 The use of personal language refers to the author's positionality within the framework of the research having been conducted and reflecting on the personal responsibility which lies within the argumentations. The need for such a personal reflection and inclusion derives from current models in research methodologies where the research process produces "first person" accounts and considers the authors personal position regarding the research (Letherby 2020:69). This positionality and identification of the author's responsibility becomes important within the feminist framework for the reason that (1) it reveals the voices of women within a context where the patriarchal symbolism of a female figure is discussed, and (2) it challenges the "malestream" practise of scholarship where traditional objectivity and neutrality is valued (Letherby 2020:69-70).

Addendum