Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

On-line version ISSN 2413-9467

Print version ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.8 n.1 Stellenbosch 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/sti.2022.v8n1.a7

GENERAL ARTICLES (ARTICLES FROM ALL THEOLOGICAL DISCIPLINES)

Between cathedral and monastery: Creating balance between a pastor's personal faith and public role Part 2: The munus triplex and the pastoral function

Peter David Langerman

Stellenbosch University, South Africa plangerman@sun.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The ordained ministry has a public component which links the ordained person to Christ as prophet, priest, and king. So, the ordained person has a prophetic role, a priestly role and a royal servant role that is defined incarnationally: the ordained person is a disciple who is called to incarnate hope in their prophetic role, incarnate love in their priestly role and incarnate faith in their royal servant role. In order to not neglect their own spiritual formation, ordained persons should use prayer, scripture, and spiritual direction as a means by which to maintain balance between their own personal faith and their public role.

Keywords: Ministry; vocation; office; prophet; priest; royal Servant; incarnational hope; incarnational faith; incarnational love; prayer; scripture; spiritual direction

Introduction

In the first part of this two-part paper we have seen that the journey to ordination begins with justification, in which the Christian disciple experiences faith, hope and love in the midst of the Triune God. What follows is a process by which the Christian disciple learns what it means to be conformed to the likeness of Christ, who is prophet, priest, and king. We have seen further that Christ's on-going ministry has relevance to the church because in Christ's exaltation and Christ's spiritual presence in the church, Christ continues to lead the church as king, priest, and prophet. The church is called to live out the real presence of Christ in its midst and the ordained leader has a significant role to play in helping the church to do this and it is to this that I will turn in this article.

In this essay I shall connect to munus triplex to the ordained ministry. Following that I shall distinguish the public role of the ordained person from personal faith and then suggest how to keep the two in alignment, using the scripture, prayer, and spiritual direction as a guide.

Ordained ministry and the Munus Triplex

Bartlett quotes the document, Baptism, Eucharist, and Ministry of the WCC, where the following statements are made regarding ordained ministry:

In the celebration of the Eucharist, Christ gathers teaches and nourishes the Church. It is Christ who invites to the meal and who presides at it. He is the shepherd who leads the people of God, the prophet who announces the word of God, the priest who celebrates the mysteries of God. In most churches, this presidency is signified by the ordained minister.1

The call to ordained ministry

In his book, Callings: Twenty Centuries of Christian Wisdom on Vocation, William Placher addresses the way in which Christians have approached this notion of call through the centuries. In answering the question as to how we are to discern such a call, Placher answers, "Most people figure out, usually as part of a community, how God is calling them through prayer and meditation inward reflection on their own abilities and desires and looking out at the world around them and its needs."2 He quotes Frederick Buechner, who wrote, "The place God calls you is the place where your deep gladness and the worlds deep hunger meet."3 Whatever it is called and however it is explained, certain people in their discipleship journey following Christ as prophet, priest and king, sense a call to ordained ministry and begin to explore this call through the processes set up in their own ecclesiological settings. Jones and Armstrong describe this process by quoting H. Richard Niebuhr, who

identifies four basic elements in the call: 1. The call to be a Christian, that is, "the call to discipleship of Jesus Christ, to hearing and doing the Word of God, to repentance and faith," 2. The secret call, "that inner persuasion or experience whereby a person feels himself [or herself] directly summoned or invited by God to take up the work of the ministry," 3. The providential call, "that invitation and command to assume the work of the ministry which comes through the equipment of a person with the talents necessary for the exercise of the office and through the divine guidance of his life by all its circumstances," 4. The ecclesiastical call, "the summons and invitation extended to a man [or woman] by some community or institution of the Church to engage in the work of the ministry."4

Thus the call to ordained ministry is discerned both individually and corporately, both existentially and ecclesiastically. Further, I would argue, once the call has been so discerned and validated it is meant to be lived incarnationally within a Christian community.

Billings, in broad agreement with Costas about incarnational ministry, argues that

the missiological implications for this understanding of the Incarnation, [are] clear that what drives it is a strong impulse to develop a norm for the missionary to not simply do things for people, but to be with them. The pattern of the Incarnation is to be a model for the church, and the climax of the Incarnation is that "Jesus died as a rejected criminal, suffering not only for but with humanity in the lowest and most horrible form of death" ... There is no doubt that-with Bonk, Perkins, and other advocates of incarnational ministry-Costas is calling missionaries to leave the compounds, leave their affluent, colonial methods of ministering "for" the poor, and become "immersed" in the situation of oppression. The Incarnation of the Word was an Incarnation to oppressed humanity, and that is what the church must also do.5

With respect, I would contend that this statement, which is meant for those involved in foreign missions, is just as true for those who are involved in the work of ministry in missional contexts in local congregations.

Can the munus triplex, which was meant to describe the work of Christ in salvation, have implications for those who find themselves called to pastor and minister in Christ's name, specifically those called to the ministry of word and sacrament? Taking the threefold office of Christ as normative and descriptive for the ministry of the pastor and arguing that the essential shape of that ministry is incarnational, the role of the pastor, who has experienced hope, faith, and love in a personal way through the administration of the grace of God by the Holy Spirit, now becomes, through ordination, the person who is called to incarnate love, faith, and hope within the Christian community. This does not mean that the pastor becomes the only one responsible for incarnating these qualities within the Christian community, but that the pastor cannot minister from a distance, from outside the community of faith. The pastor must, like Christ, be among people to model, to incarnate, love, faith, and hope within the faith community.

The pastor as prophet: Incarnational hope

The role of the pastor as prophet is that he/she has to do with the presence of the Living God present in the life of the congregation and the world. In a world dominated by powerful interests and shaped by materialistic self-interest, the prophetic role of the pastor means that the pastor points people to an alternative reality. This reality is rooted in the present, but also points to an alternative future, a reality based on the presence of the rule and reign of God in their midst. The pastor's prophetic function is to encourage people to see this largely hidden reality through the exercise of prophetic imagination. The primary place where the pastor presents the people with a vision of this alternative present and future is the pastor's preaching ministry. Leith, writing about the Reformed understanding of preaching, says that there are four distinct emphases:

1) Preaching is proclamation of the gospel - what God has done in creation judgment and redemption. 2) Human life ... has cosmic significance and the gospel must be applied to it. 3) All this is done in the light of a biblical and theological vision of reality. 4) Preaching is the means by which God's grace is mediated to the church and the church as a community is established.6

Wainwright writes, "The church ... lives from the faith that Christ is present in the midst of those gathered together in his name (Mat 18:20) and accompanies them on mission."7 The prophet seeks to keep people focused on God's will for the person, the community, and the world through spiritual discernment. Burger writes, "Learning and growth in faith take place as people hear the stories of Jesus over and over again and reflect on those accounts and see and learn all that they can from them."8 The role of the prophet is to incarnate hope; to speak with prophetic imagination and to point to God's preferred future for the individual and the community which is centred on the good news of the coming of the Kingdom of God, the rule and reign of God. Burger writes, "This is good news, because it points to new possibilities and new life for all those who are struggling and those who have given up hope."9 This means that the prophetic role of the pastor is primarily incarnational hope. Burger quotes Edmund Schlink who asked what the first task of the church should be after the ascension. Schlink's answer was that "the first task of the church should be to proclaim over and over again the merciful, life-giving rule of Christ over the whole world as a call that invites us to a new life." This is principally realized in the pastor's preaching ministry where he / she will try to answer four basic questions: 1) Who is God? 2) What does God expect of us? 3) What is God's ultimate plan for our lives? And 4) What is God up to? The prophetic role is to keep people focused on what God is doing in the world today through discernment, prophetic imagination, and preaching the Word.

In his thought-provoking and provocative article, Liston describes the parameters of the reality of the alternate reality, the presence of the rule and reign of God within the Christian community living in the presence of the Spirit. Although the author presents these under the broad heading of the kingly role of Christ, I believe they are just as relevant in a discussion of the prophetic office:

First, the qualities of truth, life, justice, and love that characterize the kingdom do so because of Christ's kingship. It is only because Christ is king that his character is reflected so perfectly in the coming kingdom. Second, through the Spirit, these kingdom characteristics are brought back to be a part of our ecclesial reality now. Their occurrence among us can be attributed to Christ's genuine presence with us as king. In other words, Christ dwells among us as king by his Spirit, and so our communities are places of truth, life, justice, and love. Of course, our ecclesial reality is not completely characterized by these qualities, because the fullness of the kingdom is still coming and has not yet arrived.10

The pastor as priest: Incarnational love

Wainwright quotes from Baptism, Eucharist, and Ministry: "But [ordained ministers] may appropriately be called priests because they fulfil a particular priestly service by strengthening and building up the royal and prophetic priesthood of the faithful through word and sacraments, through their prayers of intercession and through their pastoral guidance of the community."11 Accordingly, when we talk about the pastor's priestly role, we are talking about his/her responsibility to be among the people, to live with them, to experience life alongside them, to teach them what it means to follow Christ, to see their pain and suffering and to respond with empathetic love: that is, to be a pastor to the people. This means that the pastor's priestly role is primarily incarnational love. It is the task of the pastor, as the priest, to demonstrate Christ's presence among the people, especially in the sharing of Christ's love. This love is grounded in the very centre of the gospel, in God's love for people.

Bartlett writes, "God gives us the gospel, and then the church, and then the church's ministers. Put the other way around, ministers serve the church, the church serves the gospel."12 The priestly role has a community focus - the pastor as priest is responsible for helping to build and foster a sense of community. The role of the pastor as priest has a specific focus on the worship service and the sharing of the Lord's Supper and it is the pastor's function to see that the worship service is well thought through, planned and that people's participation in that event has meaning and that they leave with a sense of having been in God's presence. Welker quotes Christoph Schwöbel, who wrote, "According to Luther's own Torgau formula, worship is nothing other than that 'our dear Lord himself may speak to us through his holy word and we should respond to him through prayer and praise.'"13 Prayer and liturgical awareness are central functions in this priestly role during the worship service and this means that the pastor must take seriously the tradition of the congregation, their symbols, rituals, stories, and language.

The pastor as royal servant: Incarnational faith

What must always be remembered is that when we talk about Christ as king, that Christ is always a servant king. Just as the kingship of Christ is revealed through sacrifice and surrender to the will of the Father, so the role of the royal servant, the one who serves Christ is marked by sacrifice and surrender. Although Christ now rules as king in his exaltation, those who minister in his name must always remember that they do not rule as earthly rulers do, but that they are called to imitate the one "who came not to be served, but to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many." In his/her role as royal servant, the pastor is a servant leader of the local community, one who is called to incarnate and live out faith in the faithfulness of God who will fulfil the promises that God has made to God's people. The servant leader is also a manager in the community and has the responsibility to ensure that the congregational resources are all marshalled in a strategic and systematic process to ensure that the congregation reaches God's preferred future. This does means that in congregational ministry, prophetic vision, discernment, and imagination are not enough - the vision must be translated into action and it is the pastor's role to ensure that the processes within the congregation are geared towards this. The pastor functioning as royal servant incarnates faith within the community. It is not enough for the pastor to incarnate the empathetic love of God and to present the congregation with prophetic imagination, but the pastor needs to incarnate faith that the God who loves and God who has a preferred future for that congregation will also do what God has promised to do within the community.14

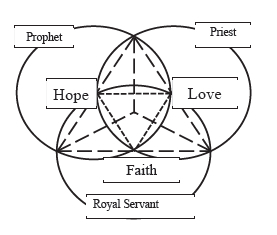

The pastor fulfils an incarnational role, incarnating faith, hope and love in the midst of the faith community. As a prophet, the pastor is helping the congregation become aware of God's action in their midst through spiritual discernment. The pastor also helps the congregation to anticipate God's preferred future for them in the eschatological in-breaking of the rule and reign of God by preaching and expounding on God's word. As a priest, the pastor is showing the empathetic love of God for the world, for the congregation and for the individual. In that demonstration of God's empathetic love, the pastor is helping people to be aware of Christ's presence that builds up the faith community. In this role as builder of community, the pastor helps to release others to participate actively in the work of ministry in the congregation. The pastor helps the congregation to experience empathetic love and Christ's presence in the services of worship, and especially in the sacrament of the Lord's Supper. As a servant leader and faithful and faith-filled servant within the congregation, the pastor serves both Christ and the congregation. The pastor incarnates and models faith for the congregation which includes both a deep-rooted trust in God and a belief that God is at work in the congregation. Through this modelling and incarnating of trust and faith, providing both leadership and management, embracing processes that encompass both vision and support, focusing on both effectiveness and efficiency, the congregation is helped to be both salt and light in the world.

While we have developed an understanding of the pastor's public role based on the munus triplex, what we have not yet done is to establish a link between the pastor's public role and the pastor's role as a disciple of Christ. Even though the pastor has a public role, it must never be forgotten that the pastor is still a disciple of Christ, experiencing faith, hope, and love, and still committed to ongoing spiritual formation. The pastor's own spiritual life is bordered by faith, hope, and love while the pastor's public role as priest, prophet, and royal servant is identified as incarnational faith, incarnational hope, and incarnational love. There are dynamic connections between the pastor's spiritual life as disciple and the pastor's public role as prophet, priest, and royal servant. When a pastor is functioning out of a healthy place, that inter-relationship will be healthy and there will be a symbiotic connection between the two parts of a pastor's life. The pastor's development as a disciple will feed into his/her public witness, and the pastor's public witness will feed into his/her ongoing development and growth as a disciple.

Misalignment between personal faith and public role

What happens when the pastor's personal faith and public role moves out of alignment? What happens when a pastor who continues to function in his/her public role begins to have a crisis of faith? An unexpected event, a pastoral catastrophe, physical or psychological illness, burnout, or a myriad of other possible crises can cause a pastor's own person faith development to stall while he/she continues to function in his/her public capacity. The pastor may still be able to function as a prophet, priest, and royal servant as described earlier, but at a personal level there is a serious disconnect. If this disconnect becomes too pronounced, the pastor may be heading for some sort of a breakdown. That breakdown might be a health issue, or a moral one, or an emotional or psychological breakdown, but it is virtually assured that a breakdown will take place at some point or another. The question is whether it is possible to keep these in alignment, and I shall argue that it is, that the tools are available to do so.

Maintaining a correlation between Sunday and weekday

A person who has written extensively and insightfully on this topic is Eugene Peterson. In several of his books he addresses the crisis that is taking place among Christian pastors, and he suggests ways in which these might be addressed. Jones and Armstrong write: "We believe that diverse pathologies afflicting contemporary ministry need to be addressed ... Even so, we are convinced that underlying the particular pathologies that beset contemporary pastoral leadership is a crisis of confidence that Christian life in general, and pastoral leadership, in particular, has a telos, a direction and purpose."15 What then, we might well ask, is the telos, the direction and purpose of ministry? Peterson argues, "The pastor's responsibility is to keep the community attentive to God."16 Peterson claims that in centuries gone past there was a correlation between the work which a pastor did on Sundays and the work that was done during the week that served to keep the community attentive to God. "The manner changed: instead of proclamation, there was conversation. But the work was the same: discovering the meaning of Scripture, developing a life of prayer, guiding growth into maturity."17 To describe this he employs an older term, the "cure of souls," which he uses to explain the pastor's primary function both on Sundays and during the days in between. He describes it this way: "The cure of souls, then, is the Scripture-directed, prayer-shaped care that is devoted to persons singly or in groups, in settings sacred and profane. It is a determination to work at the centre, to concentrate on the essential."18The question that follows quite naturally from this is: "How should a pastor keep a community attentive to God without losing his/her faith in the process?" Peterson suggests three pastoral acts that should give shape, form, and function to the pastoral enterprise, namely prayer, reading Scripture, and spiritual direction. He explains:

The three areas constitute acts of attention: prayer is an act in which I bring myself to attention before God; reading Scripture is an act of attending to God in his speech and action across two millennia in Israel and Christ; spiritual direction is an act of giving attention to what God is doing in the person who happens to be before me at any given moment.19

We shall explore these together and suggest how they function in keeping balance between a pastor's personal faith and his/her public role.

Prayer

Peterson defines prayer as a decision to "deliberately interrupt our preoccupation with ourselves and attend to God, place ourselves selves intentionally in sacred space, in sacred time, in the holy presence - and wait. We become silent and still in order to listen and respond to what is other than us."20 Peterson argues that "[f]or the majority of the Christian centuries most pastors have been convinced that prayer is the central and essential act for maintaining the essential shape of the ministry to which they were ordained."21 Prayer is a relational word and the discipline of prayer, as well as the various patterns of prayer, provides a means by which Christians can be attentive to the actions of the Triune God during the course of the day. Adele Ahlberg Calhoun quotes Henri Nouwen, who said,

To pray is to descend with the mind into the heart, and there stand before the face of the Lord, ever-present, all seeing, within you ... Prayer is the way to both the heart of God and the heart of the world-precisely because they have been joined through the suffering of Jesus Christ ... Praying is letting one's own heart become the place where the tears of God's children merge and become tears of hope. 22

Peterson argues that "[p]rayer is our way of being attentively present to God who is present to us in the Holy Spirit."23 Peterson argues that prayer, which both speaks to God and which hears God speaking, takes place in the middle voice. It is not wholly active nor passive, but "the complex participation of God and the human, his will and our wills ... We neither manipulate God (active voice) nor are manipulated by God (passive voice). We are involved in the action and participate in its results but do not control or define it (middle voice)."24In order to be involved in this middle voice activity, Peterson argues for keeping Sabbath which he links very closely to prayer. To keep Sabbath is to pray and to pray is to keep Sabbath: "We must stop running around long enough to see what he has done and is doing. We must shut up long enough to hear what he has said and is saying. All our ancestors agree that without silence and stillness there is no spirituality, no God-attentive, God-responsive life."25He argues that "prayer is never the first word; it is always the second word. God has the first word. Prayer is answering speech; it is not primarily 'address' but 'response.'"26 And where do we learn how to speak to God in prayer and hear God's response? Peterson answers simply, the Psalms:

The great and sprawling university that Hebrews and Christians have attended to learn to answer God, to learn to pray, has been the Psalms. More people have learned to pray by matriculating in the Psalms than any other way. The Psalms were the prayer book of Israel; they were the prayer book of Jesus; they are the prayer book of the church.27

So, for Peterson, prayer and keeping Sabbath are vitally important, even essential pastoral activities that help pastors to remain attentive to God and involved in what God is doing in the world. Prayer and Sabbath keeping are means by which we guard against either an over-inflated ego or descend into passivity.

Scripture

By Scripture, Peterson is referring to the living word of God, the primary place where, and the primary means by which, God communicates to human beings. Peterson argues for what he calls "contemplative exegesis in which the pastor's chief concern is not to argue for one theological position over another, but to present 'the unbroken consensus of Israel and church in regard to Scripture': that a living God speaks a living word and that the Holy Scriptures are the written representation of that word."28Douglas suggests that we regard Scripture as authoritative because it is a kind of two-way communication: "Human words that point to the Lord and God's word being transformed by that Lord."29Douglas asks whether the scripture is important and powerful. He answers an emphatic, if qualified, affirmative answer to both questions: the importance of Scripture cannot be separated from the community that is given shape by it and the power of scripture cannot be reduced to some sort of magic formula. If its importance and power for the Christian community is to be realized, the scripture must be exegeted. This might well be some of what Peterson intends by "contemplative exegesis." In explaining the term, Peterson references Annie Dillard's Pulitzer prize winning work published in 1974, Pilgrim at Tinker's Creek. Peterson describes Dillard's task as "contemplative exegesis, receiving and offering, wondering and praying."30

Calhoun, who addresses the practice that Peterson advocates as "devotional reading," or lectio divina, writes there have been, classically, five movements to this:

12. Silencio: the quiet preparation of the heart before God.

13. Lectio: reading the passage slowly and out loud while being attentive to what God might be saying. When a word or phrase strikes one, stop reading and attend to what God might be saying in that moment. The key is to wait and to listen.

14. Meditatio: reading the passage out loud a second time, being attentive to what God might be saying and like Mary, storing up the words in one's heart.

15. Oratio: reading the passage a third time and then responding in prayer in prayer. One is attendant to the feelings that the reading has evoked in one's heart and where there might be resistance or the tendency to push back or where one has been invited into a deeper walk with God.

16. Contemplatio: one rests and waits in the presence of God whole allowing the word to sink deeply into one's soul. One yields and surrenders oneself to God.31

Spiritual direction

In Peterson's definition, spiritual direction happens when:

Two people agree to give their full attention to what God is doing in one (or both) of their lives and seek to respond in faith [and] three convictions underpin these meetings: 1) God is always doing something: an active grace is shaping this life into a mature salvation; 2) responding to God is not sheer guesswork: the Christian community has acquired wisdom through the centuries that provides guidance; 3) each soul is unique: no wisdom can simply be applied without discerning the particulars of this life, this situation.32

Naidoo references the definition of spiritual direction provided by Barry and Connolly as "help given by one Christian to another which enables the person to pay attention to God's personal communication to him or her, to respond to this personally communicating God, to grow in intimacy with God and to live out the consequences of the relationship."33Peterson suggests three prerequisites for those who seek to be good directors of others. First, he says, they must cultivate an attitude of awe, wonder, and marvel at the person whom they have the privilege of directing, for "[t]his face before me, its loveliness scored with stress, is in the image of God."34Second the director must acknowledge his/her own ignorance since, if they are to be of assistance to the one seeking direction, they must admit that there is so much that they do not know. Third, the director needs to foster and encourage a predisposition to prayer since the person being directed, in some way, needs to learn how to connect with God in some meaningful way. Because spiritual direction means paying close attention to what God is doing in the life of a person, it is natural to expect certain things to happen in the life of both director and directee because of this relationship. It is not so much that the practice of direction causes certain outcomes, but that intentionally paying attention to what the Spirit is doing in the life of a person does bear fruit in that person's life. Naidoo points out that as the process of spiritual direction begins to bear fruit in the life of the person under direction, certain things begin to take shape: "(a) the person begins to awaken to her true identity with God's grace, dethrones the false self; (b) conversation and communion with God increase and deepen into a sense of spiritual union; (c) the various dimensions of the person become united by the presence and love of the indwelling Christ."35 How, then, do prayer, scripture, and spiritual direction help to provide balance between the pastor's personal experience of justification and sanctification and the pastor's public role as prophet, priest, and royal servant?

Prayer, Scripture, and spiritual direction, and on-going spiritual formation

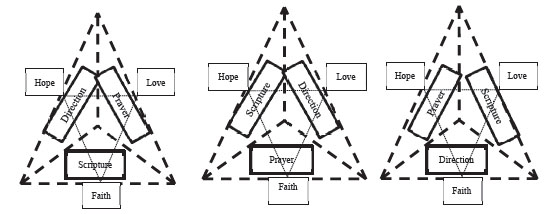

If we begin with the link between the pastor's experience of faith, hope, and love and the practices of prayer, Scripture, and spiritual direction, the three diagrams that follow are helpful. In these diagrams, we see illustrated the interconnectedness between prayer, Scripture, and spiritual direction and the pastor's journey of faith, hope, and love in terms of justification and sanctification. Because spiritual direction is a conscious decision to be attentive to what God is doing in the life of another person, a deliberate awareness of the presence of the gracious and loving God in another, spiritual direction nurtures hope, love, and faith in both director and the directed. In the devotional reading of Scripture, by allowing space for God to speak and the person make the commitment to listen, the person becomes attentive to what God is saying. During this sacred time and in this sacred space the voice of the living God speaks to a living person in the present, and this dynamic relationship between the God who speaks and the person who listens and responds similarly nurtures faith, hope, and love. Because prayer is a conscious decision to be in sacred space and within sacred time and to be silent in the presence of the living God, the pastor funds him/herself in "middle voice" space where the pastor is both addressee and participant in God's cosmic drama. This "middle voice" interactionbuild s and nourishes faith, hope, and love.

The pastor's personal faith and public role nurtured by prayer, Scripture, and spiritual direction

In the following diagram we have a picture of how these coincide and cooperate with one another, how the pastor's personal experience of faith, hope, and love, nurtured by prayer, scripture and spiritual direction relate to his/her public witness as prophet, priest, and royal servant.

What the diagram suggests is that it is possible to cultivate an inherently stable interrelationship between the pastor's personal faith experience and the pastor's public witness using the disciplines of prayer, Scripture, and spiritual direction. With only the pastor's personal faith experience of faith, hope, and love and the pastor's public role as prophet, priest and royal servant, there are always the possibilities of distortions occurring. In the diagram below, which I would suggest, happens frequently in mainline denominations where pastoral ministry is regarded as primarily pastoral, there can be an overemphesis on the pastoeal function, the incarnation of love, to the detrimentof theprophetic and reyal servant roles of the pastor in the congregstion. If wo reier back to the previous diagram, it can be seen that the diecipllnes of psayer, Scripture, and epirituai direction help to maintain thebrlanee berween the pastor's public role anttpersonal faith and will help So poevent rhe kind ofdistortlonillustrated in the following diagram fro happening. In these circumstances, it is clear that the possibilities of this type of distortion are far less likely which would mean that the pastor is in a much healthier place and the congregation is being much better served.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in this article it has been contended that in order to help clergy remain in ministry and faithfulto their call, there needs to be balance between the pastor's personal faith(the pastor'sexperience of faith, hope, andlovefromtheTriuneGod)andthepastor'spublicrole as prophet,priest,androyalservant(the incarnation offaith,hope,andlove inthemidst of afaithcommunity) followingChristasprophet,priest, and king.Despitethecriticismsthathave arisen,ithas beencontendedthatthe incarnational model, whereby the pastor doesn't just do things for others, particularly the poorand oppressed, but with them, isin conformitywith thenatureof Christ's ownministry.In this participation with,thepastor, aspart ofthecommunityishelpingtomakethefour-fold values oftherule and reign of God, namely truth, life, justice, and love become part of the Christian community's present reality.

Ithasbeen established thatthe Christianpastorbeginsas a disciple who iscalled, andthen licensed into ordained ministry as prophet, priest, and royal servant to follow Christ, our prophet, priest, and king. It has been demonstratedthat thereshouldbeavitallinkbetween the pastor's journey of justification andsanctification as a disciple of Christ and the pastor's public role,and it hasbeen arguedthat when there is tension between a pastor's ownspiritual journey andthepastor's public role, apastormight wellbeheadingtowards abreakdown of some sort. It has been shown that the dynamicinterrelationship of prayer, Scripture,andspiritual direction are available means by which pastors keep the balance between their personal faith and their public role so as to be faithful to their call.

Bibliography

Bartlett, David L 1993. Ministry in the New Testament. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Billings, J 2004. Incarnational Ministry and Christology: A Reappropriation of the Way of Lowliness. Missiology, 32(2):187-201. [ Links ]

Burger, Coenie 2011. Waar is Jesus nou? Translated by Peter Langerman. Vereeniging, ZA: Christelike Uitgewers Maatskappy. [ Links ]

Calhoun, Adele Ahlberg 2005. Spiritual Disciplines Handbook: Practices That Transform Us. Kindle. Downers Grove, IL: Inter VarsityPress. [ Links ]

Douglas, Mark 2005. Confessing Christ in the Twenty-First Century. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [ Links ]

Jones, L. Gregory and Kevin R. Armstrong 2006. Resurrecting Excellence: Shaping Faithful Christian Ministry. Kindle. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Leith, John H 1990. From Generation to Generation: The Renewal of the Church According to Its Own Theology and Practice. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Liston, Gregory John. Eschatology and the Munus Triplex: The Threefold Anointing of the Spirit in Time. Journal of reformed theology 14(4):323-343.

Naidoo, Marilyn 2006. The Healing Power of Spiritual Direction. Practical Theology in South Africa, 21(3):139-154. [ Links ]

Peterson, Eugene H 2005. Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places: A Conversation in Pastoral Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. Kindle. [ Links ]

Peterson, Eugene H 1989. The Contemplative Pastor: Returning to the Art of Spiritual Direction. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. Kindle. [ Links ]

Peterson, Eugene H 1992. Under the Unpredictable Plant: An Exploration in Vocational Holiness. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Peterson, Eugene H 1987. Working the Angles: The Shape of Pastoral Integrity. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. Kindle. [ Links ]

Placher, William C. (ed.) 2005. Callings: Twenty Centuries of Christian Wisdom on Vocation. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Wainwright, Geoffrey 1997. For Our Salvation: Two Approaches to the Work of Christ. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Welker, Michael 2013. God the Revealed: Christology. Translated by Douglas W Stott. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

1 David L. Bartlett, Ministry in the New Testament (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1993), 186.

2 William C. Placher, ed., Callings: Twenty Centuries of Christian Wisdom on Vocation (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co, 2005), 3.

3 Ibid.

4 L. Gregory Jones and Kevin R. Armstrong. Resurrecting Excellence: Shaping Faithful Christian Ministry. Kindle. (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company Publishing Company, 2006), Kindle location 83.

5 J. Billings, "Incarnational Ministry and Christology: A Reappropriation of the Way of Lowliness." Missiology 32, no. 2 (April 2004):190.

6 John H. Leith, From Generation to Generation: The Renewal of the Church According t Its Own Theology and Practice (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1990), 93

7 Geoffrey Wainwright, For Our Salvation: Two Approaches to the Work of Christ. (Gram Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1997), 132.

8 Coenie Burger, Waar Is Jesus Nou? trans. Peter Langerman (Vereeniging, SZ: Christelik Uitgewers Maatskappy, 2011), 196.

9 Ibid, 197.

10 Gregory John, Liston. "Eschatology and the Munus Triplex: The threefold anointing of the Spirit in time." Journal of Reformed Theology, 14, no. 4 (2020):341.

11 Wainwright, For Our Salvation, 146.

12 Bartlett, Ministry in the New Testament, 185.

13 Michael Welker, God the Revealed: Christology. Translated by Douglas W Stott (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2013), 278.

14 This contains aspects of both leadership and management, of both effectiveness and efficiency. It is in this role that pastors need to understand the inner processes within their congregations as well as to understand the way in which the Spirit is working in the congregation. The purpose of this aspect of the pastor's task is to ensure that the congregation understands what it means to be the light of the world and the salt of the earth. To this end, processes and programs and structures are necessary, but no such processes, structures and programs last forever. It is the pastor's task here to be able to suggest that those processes, structures, and programmes that do not serve the task of the congregation as salt and light should be ended and others initiated.

15 Jones and Armstrong, Resurrecting Excellence, 26.

16 Eugene H. Peterson, Working the Angles: The Shape of Pastoral Integrity (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1987), Kindle location 2.

17 Eugene H. Peterson, The Contemplative Pastor: Returning to the Art of Spiritual Direction (Grand Rapids, MI.: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1989), Kindle location 488.

18 Ibid., 492.

19 Peterson, Working the Angles, Kindle location 2.

20 Eugene H. Peterson, Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places: A Conversation in Pastoral Theology (Grand Rapids, MI/Cambridge, UK: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2005), Kindle location 41.

21 Peterson, Working the Angles, Kindle location 26

22 Adele Ahlberg Calhoun, Spiritual Disciplines Handbook: Practices That Transform Us (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2005), Kindle location 203.

23 Peterson, Christ Plays, Kindle location 272.

24 Peterson, The Contemplative Pastor, Kindle location 933.

25 Peterson, Christ Plays, Kindle location 117

26 Peterson, Working the Angles, Kindle location 45.

27 Ibid., 50.

28 Peterson, Working the Angles, Kindle location 113.

29 Douglas, Confessing Christ in the Twenty-First Century (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005), 153.

30 Peterson, The Contemplative Pastor, Kindle location 631.

31 Calhoun, Spiritual Discipline, Kindle location 2003-2011.

32 Peterson, Working the Angles, Kindle Location 150.

33 Marilyn Naidoo, The Healing Power of Spiritual Direction, Practical Theology in South Africa, 21, no. 3 (2006):141.

34 Peterson, Working the Angles, Kindle Location 188.

35 Naidoo, "The Healing Power of Spiritual Direction," 142.