Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

On-line version ISSN 2413-9467

Print version ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.7 n.1 Stellenbosch 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2021.v7n1.a19

GENERAL ARTICLES

The African principle of reciprocity: Examining the "golden rule" in light of the ubuntu philosophy of life

Elia Shabani Mligo

Teofilo Kisanji University, Mbeya, Tanzania, eshamm2015@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The aspect of reciprocity is highly enshrined in the African culture. It is part and parcel of communal life of African people despite their various life predicaments. However, reciprocity is not only found in African culture; it is also a universal aspect found in other cultures and religions of the world. The universality of reciprocity is evident in the universal golden rule. Through surveying the golden rule in the various religious traditions and examining the tenets of the African philosophy of Ubuntu, this article argues that although reciprocity is a universal aspect, it can hardly be fully realized in Africa without considering the African philosophy of Ubuntu. The philosophy of Ubuntu stands not only as a cornerstone for African reciprocal relationships, but also as a distinction between the African and other ways of life.

Keywords: Reciprocity; ubuntu; golden rule; world religions

1. Introduction

In the beginning of his article "African Ubuntu philosophy" Lutz (2009:1) writes:

One of the most striking features of the cultures of sub-Saharan Africa is their non-individualistic character: Although African cultures display awesome diversity, they also show remarkable similarities. Community is the cornerstone in African thought and life. An African is not a rugged individual, but a person within a community. (...). People are not individuals, living in a state of independence, but part of a community, living in relationships and interdependence.

Lutz's statement above clarifies the concept of Ubuntu as an African philosophy of life. It also highlights the meaning of reciprocity in Ubuntu philosophy.

The concept of reciprocity is articulated further in the proverb of Bena people of Njombe Region in Tanzania. The Bena people say: "hawoho bite, hawoho wuye" (Literal meaning: the hand goes, the hand comes back). In Swahili, the language spoken by most countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the proverb goes: "mkono nenda, mkono rudi". In this proverb, the Bena people and Swahili language speakers use the "hand" metaphorically to explain what happens during the relationship between people. The hand that goes does not go empty. It carries with it something; it carries with it favours. Likewise, the hand does not go anywhere, to a vacuum; rather it goes to somebody, whether intended or not. The hand which goes to someone is expected to come back, not the same hand; rather, it is the hand from the other person. The person who received the hand is expected to return a similar or a rather different hand from the one received depending on the kindness of the one receiving the hand. Therefore, the proverb indicates the unending reciprocal relationship of kindness among the Bena, and probably among Africans as a whole. The relationship of kindness entails giving favours to someone and returning back the favours received; moreover, it has to do with aiding one another in various issues of life.

Etymologically, the notion of reciprocity originates from the Latin reciprocus, which means "going back and forth" or "giving and receiving back." According to Bruni, Gilli and Pelligra (2008:2), reciprocity has to do with "mutual exchange, not logically equivalent to the notion of equal give and take." Following this understanding, reciprocity is a human behaviour of evaluating the behaviour of other human beings regarding the kindness received or provided to them. Therefore, "a reciprocal action is modelled as the behavioural response to an action that is perceived as either kind or unkind" (Falk & Fischbacher 2008:293).

Scholars, however, have differentiated reciprocity from "reciprocal altruism," I give so that you will give to me in return. According to scholars, a "reciprocal altruist is only willing to reciprocate if there are future rewards arising from reciprocal actions" (Falk & Fischbacher 2008:293 note 1). The true reciprocity is not based on expected rewards; rather, it is based on intentional kindness. It is people's responses to perceived kindness they receive from other people. Therefore, reciprocity is exercised as a norm through the guidance of the golden rule in various religious traditions.

This article argues that though reciprocity is exercised as the norm in the form of the golden rule in various world religious traditions, it can hardly be realized in African context in isolation without considering the Ubuntu philosophy of community life. In order to justify the efficacy of Ubuntu philosophy as the core of reciprocity in the African context, the discussion commences with the portrayal of the golden rule in the world religious traditions, then the sense of community in African perspective, and ends with the practice of reciprocity in Africa on the basis of the existing African philosophy of life.

2. Reciprocity in world religious traditions

In Christianity, reciprocity is based on what is generally called the Golden Rule. The Golden Rule requires one person to stand in the shoes of another person. It requires people to act to others in the way that such actions could also be delightful to them. It is true that one can hardly please everyone in terms of actions. Also, it is sometimes hard to know whether a certain action pleases the recipient or the affected (person to whom action is done), although such action may seem pleasing to the doer (person doing the action). However, one of the more vivid outcomes of the golden rule is the creation of awareness upon individuals on the way people are affected by the actions one does to others. Hence, as Rakhshani (2017:468) says, "Instead of imposing answers on us, this rule focuses on our argument, fights with our selfishness and makes use of ideals such as fairness and concern for others in a tangible and concrete way."

In Christianity, the golden rule is found in Matthew and Luke. In Matthew 7:12 it reads, "So whatever you wish that men would do to you, do so to them; for this is the law and the prophets." The golden rule goes simultaneously with the commandment of love which reads, "You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with your entire mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it, You shall love your neighbour as yourself." (Mt 22:37-39).

Moreover, within Christianity, the golden rule is clearly notable in the life and practice of faith of Christians of the early church. Christians of the early church lived a life of solidarity and sharing of possessions, each according to his/her needs. In the book of Acts, it is written: "Now the whole group of those who believed were of one heart and soul, and no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common. There was not a needy person among them, for as many as owned lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds of what was sold. They laid it at the apostles' feet, and it was distributed to each as any had need" (Acts 4:32-35). Following the same view, Mligo (2020:227) concludes: "being of 'one heart and soul' indicates the sense of mutuality and solidarity in terms of human value which depended sorely on what they were, not on what they did. It is a mutuality and solidarity that preserves life instead of destroying it."

The golden rule is not only a Christian rule of human relationship; rather, it is accepted by various religious and secular traditions as a foundation of teachings which govern human relationships. Rakhshani (2017:468) states that:

Different religions and cultures of the world have abundantly confirmed the golden rule. Jesus, Confucius, and Rabbi Hillel regarded the rule as a summary of their teachings in general. Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Zoroastrianism, and the cult Dao as well as secular thinkers in different cultures have confirmed this rule, and many of them consider the rule as the core of ethical thinking. Hence, the golden rule has become an almost global principle, i.e., a rule common to all people in all times and places.

Rakhshani illustrates the above point by stating how other religious traditions conceive the golden rule. According to her, the golden rule is found in the three sets of Buddha's teachings: Dhammapada, Udana and Sutta-Nipata. In Dhammapada it reads, "He who seeks his own happiness by oppressing others, who also desires to have happiness, will not find happiness in his next existence" (Dhammapada 1985:131). In Udana it reads, "There is nothing dearer to man than himself; therefore, as it is the same thing that is dear to you and to others, hurt not others with what that pains you" (Udanavarga 5:18). In Sutta-Nipata it reads, "As I am, so are these. As are these, so am I. Drawing the parallel to yourself, neither kill nor get others to kill" (Sutta-Nipata 1947:705). Therefore, in Buddhist teachings one finds the needed "I-We" as contrary to "I-Thou" relationship of Martin Buber mostly emphasized in the Western thought.

In Confucianism, Rakhshani (2017:469) presents it as it reads in the Analects, Zigong asked: "Is there a single word that can serve as a guide to conduct throughout one's life?" Confucius said: "Perhaps the word 'shu', 'reciprocity': 'Do not do to others what you would not want others to do to you' (Analects 15:24)." With these words, the Analects of Confucianism also teaches about the reciprocal relationship between people as a single rule to guide human life.

In Hinduism, Rakhshani (2017:469) presents two statements, both the negative and the positive statements of the golden rule: The negative statement reads: "One should never do that to another which one regards as injurious to one's own self." The positive statement reads: "That man who regards all creatures as his own self and behaves towards them as towards his own self succeeds in attaining to happiness" (Mahabharata: Anusasana Parva, Section CXIII:240).

In Zoroastrianism, the golden rule is found in the Gathas which are the oldest teachings of Zoroaster. According to these teachings, the happiness of an individual does not belong to him/her alone, it also belongs to other people and one can achieve happiness through making other people happy. Rakhshani (2017:470) quotes from the Gathas: "Mazda, God's absolute commander decreed that: 'The fortunate person is one who makes others happy'. The doctrine is connected to the golden rule in that the happiness is achievable when the person, first, thinks of others and secondly, does everything to make other people happy" (Gharamaleki 2014:86).

In Judaism, the golden rule is found first in the book of Exodus. The texts read, "You shall not wrong a stranger or oppress him, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt" (Ex 22:21). "You shall not oppress a stranger; you know the heart of a stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt" (Ex 23:9). The commandment of love found in Leviticus 19:18 is also another complementary of the golden rule. It reads, "You shall not take vengeance or bear any grudge against the sons of your own people, but you shall love your neighbours as yourself: I am the LORD." Here the golden rule stipulates the practicability of the commandment of love (Rakhshani 2017:470). Second, the golden rule is found in the rabbinic teachings. In the Talmud, it is written: "What is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbour: that is the whole of the Torah; all the rest of it is commentary." (Talmud, Shabbat, 31a) Third, it is found in some Old Testament Deuterocanonical books. In the books of Tobit and Sirach, the golden rule is stated: "Do to no one what you yourself dislike." (Tobit 4:15) "Recognize that your neighbour feels as you do, and keep in mind your own dislikes." (Sirach 31:15) Hence, the commandment of love of neighbour and the golden rule described in Judaism compel people who would like their neighbours to do good acts to them to do likewise.

In Islam, the golden rule is found in several verses of the Holy Qur'an and the collected oral and written sayings and teachings of Prophet Muhammad. Two of such Qur'anic texts are the following: A verse from Surah Al-Mutaffifin reads, "Woe to the diminishers, who, when people measure for them, take full measure but when they measure or weigh for others, they reduce!" (Mutaffifin 1-3) And a verse from Surah al Baqarah reads, "Believers, spend of the good you have earned and of that which We have brought out of the earth for you. And do not intend the bad of it for your spending; while you would never take it yourselves, except you closed an eye on it. Know that Allah is Rich, the Praised" (Al Baqarah 267). In one of the collections of the teachings and sayings of the Prophet, it is written: "A Bedouin came to the prophet, grabbed the stirrup of his camel and said: O the messenger of God! Teach me something to go to heaven with it. The prophet said: 'As you would have people do to you, do to them; and what you dislike being done to you, don't do to them. Now let the stirrup go! [This maxim is enough for you; go and act in accordance with it!]'" (Kitab al-Kafi, Vol.2: 146)

In the above illustrations of the way the golden rule is articulated in various world religious traditions the golden rule indicates a reciprocal relationship between people. The way one would like others to treat him/ her that person should treat others likewise. In African religious tradition, the life of reciprocity in the form of Golden Rule is based on the African philosophy of Ubuntu.

3. The African philosophy of Ubuntu

The philosophy of Ubuntu, as an African way of life, is discussed by many people in various fields of studies (Lutz, 2009; Manganyi & Buitendag, 2017; Msengana, 2006; Dolamo, 2013; Mandova & Chingombe, 2013; Gathogo, 2008 & Chibvongodze, 2016). However, according to Dolamo (2013), the concept of Ubuntu originates from two sets of languages: the Sesotho languages which include the Sepedi, Setswana and (Southern) Sesotho languages. In these languages, the concept of Ubuntu is known as Botho. Another set of languages in which the term Ubuntu is found is the Nguni languages including isiZulu, isiXhosa, isiNdebele, isiSwati and some other languages from sub-Saharan Africa (cf. Mligo 2020:225227 & Van Norren, 2014:256). There are other languages having words with derivatives from the concept of Ubuntu, such as the word "Mtu" in Swahili (Tanzania), "Munhu" in Shona (Zimbabwe) and "Mundu" in Kikuyu (Kenya) (Mandova & Chingombe, 2013; Mligo, 2020:226-227 & Nnamunga, 2013:128 note 323). Therefore, all the above depictions of the concept of Ubuntu, as an expression of African way of life speak about "humanness" or "person-hood" in African point of view. Ubuntu expresses the African people's life of compassion, hospitality, reciprocity, mutuality, and dignity which make them live a life of collectivity and relatedness.

In order to justify the above notions of Ubuntu, the mentioned tribes or ethnic groups have proverbs which guide life. Nnamunga (2013:127) has written:

Human being only discovers full personality and human wholeness in a group of relationships because in relationship there is "both an end and an entity". Relatedness promotes tolerance and integral human flourishing. A much-quoted South African proverb: Motho ke motho ka batho ka bang, which means "I am because we are, and since we are therefore I am," epitomizes essential personhood for Africans. This proverb affirms the understanding that identity arises out of inter-subjective interactions between persons. It articulates the conviction that each one becomes a human being only in fellowship with others.

Nnamunga (2013:127 n. 318) adds,

Another version of the same proverb says: umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu which means "a person is a person through other persons." By this proverb, Mbiti speaks of the traditional African view of the human being. It means: "Whatever happens to an individual, happens to the whole group and whatever happens to the whole group, happens to the individual." It resonates with the holistic understanding of the human being. It is also a critique of Descartes' cogito ergo sum, "I think therefore I am." Descartes puts the emphasis on "I" whereas the proverb's emphasis is on "We".

Nnamunga's words indicate that as an African philosophy, the life characterized by Ubuntu centres on the notion that a person is a person because of other people. Without dependence on other people's presence, there is no life in its full sense. This philosophy is shared by all tribes of Western, Southern, Eastern and Central Africa whose people have a Bantu origin. African people do not believe in the autonomy of an individual; rather, they believe in group solidarity and the power of communal life. To Africans, what entails by Ubuntu is that life is lived in community characterized by sharing and caring for one another. The brotherly and sisterly concern to one another is the one which makes Africans suppress most pressing atrocities, such as hunger, poverty, isolation, or any other deprivations in life. In this case, Ubuntu as a philosophy of life does not only favour a life lived in community, but also a humanist way of viewing and relating to another person.

Despite its well-stipulated tenets, the philosophy of Ubuntu has not been without criticisms. Lutz (2009:2) states that "One of the criticisms of the concept of ubuntu is that it is vague: 'The trouble is that Ubuntu seems to mean almost anything one chooses.' Other criticisms have also been posed to Ubuntu philosophy: it is limited to Africa and has no relevance to other parts of the world; it has no relevance for the contemporary world, it is only relevant to ancient village life in the African context; it is not homogeneous among Africans themselves because of their varied ethnic groups; Ubuntu hinders development due to its overemphasis on communalism; ubuntu is anti-communist in the Marxist sense because it hardly takes into account the existing "class struggles" within communities, having no significant role in empowering people to encounter their life predicaments; Ubuntu stresses communism without being compatible with western theoretical perspectives on development; and Ubuntu is not a unique philosophy because it deals with humanistic issues of caring and compassion which are also prominent in the tradition of western thought (see Van Norren, 2014:257-259; Magutu, 2018:7-10; Enslin & Horsthemke, 2004 & Curle, 2015).

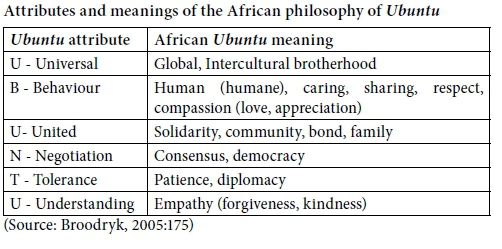

These and similar criticisms are mostly posed by western or western-oriented scholars who hardly understand the African network of human relationships in the "insider" point of view. For such scholars, community life and interdependence among people are unimaginable aspects. However, Lutz (2009:2), quoting from Tutu, further clarifies that "Ubuntu is very difficult to render into a Western language. It speaks of the very essence of being human" (Cf. Letseka, 2012). In that sense, it is difficult to understand Ubuntu philosophy as a way of life from outside Africans themselves and the way they live life in community. The table below summarizes the meaning of the concept of Ubuntu based on the attributes deduced from the word Ubuntu itself.

4. Reciprocity and the African sense of community

The concept of "community," as distinguished from "society" has been clearly articulated by Agulanna (2010) in his article "Community and human well-being in an African culture." In this article, Agulanna (2010) sees the concept of community as one that philosophers, sociologists, anthropologists, ethnologists, and other existing fields of studies have deeply endeavoured to discuss. While there are various conceptions within the various fields of studies regarding the concept of community, the concept stands as the major distinguishing aspect between the life of a person as an individual, and the life of a person in relation to other people. To emphasize the importance of the individual in individualist societies, Agulanna (2010:285) quotes the statement from the ancient philosopher, Protagoras, saying: "Man is the measure of all things, of things that are they are, of things that are not that they are not." What Agulanna (2010:285) conceives of this statement is that "it is human beings that give meaning to reality - to things, events and objects we have in the world." Quoting from Glicksberg, Agulanna (2010:285) summarizes that "man creates his own world of meaning, composes his own dream of significance and of course, charts the course of his own life."

To emphasize the importance of community, Agulanna (2010) provides distinguishing definitions of both community and society. According to him:

Society in general is the totality of peoples that have existed in history. A particular society is a given population living in a certain region whose members cooperate over a period of time for the attainment of certain goals or ends. It is in the first sense above that we can talk of "the human society" as a whole. In the second sense, we may talk of say, the Nigerian society, the American society, Fulani society, or the Yoruba society, etc. (Agulana 2010:286)

Here, the concept of society entails a people and its way of life, its culture. One significant feature of society is social dissociation between one individual and another and rare intimate interaction among people. Each individual is autonomous, and life is fully realized when the individual thinks on how to manage his/her own living. In other words, there is little interdependence in society. It is the life in society that was, and is, favoured by western individualism where there is rare interaction and the individuals are dependent on their own decisions and wills in order to make life possible.

In defining community, Agulanna (2010:287) says, "By 'community' on the other hand, we usually have in mind a sub-society whose members (1) are in personal contact, (2) are concerned for one another's welfare, (3) are committed to common purposes and procedures, (4) share responsibility for joint actions, and (5) value membership in the community as an end worth pursuing (...)."

With this definition, community entails a smaller part within society where there is more social cohesion and interdependence. People live in dependence of one another in order to make life possible. Contrary to western individualism, Africans are in favour of community life. It is in community where life is realized. A person is dependent on other people to make the meaning of life clearer. Moreover, there is intimate cohesion between one person and another and that makes the common purposes of community become true. The following part of this article examines the way in which the sense of solidarity is realized within the African context and its application and relationship with the golden rule.

5. Reciprocity and the African solidarity in community

The definition of community by Agulanna (2010), as presented in the previous paragraph points to the African sense of solidarity. It is within community where the golden rule is practiced. It is within community where everyone needs another person's participation in enhancing life; it is within the community where the Bena proverb of "hawoho bite, hawoho wuye" is clearly realized. It is within the community where the Swahili proverb "mkono nenda, mkono rudi" is realized. The person provides to another person for the sake of contributing to the well-being of the receiving person. A similar contribution is expected to be made to him/her in his/her time of need.

However, the overemphasis on community provided in this section should not be taken as a denial of the individual autonomy within a particular community; rather, as Onyedinma and Kanayo (2013:62) put it, "The autonomy and rights of the individual person are enjoyed in relationship." Lutz (2009:1) has further emphasized: "The communal character of African culture does not mean, however, that the good of the individual person is subordinated to that of the group, as is the case with Marxist collectivism. In a true community, the individual does not pursue the common good instead of his or her own good, but rather pursues his or her own good by pursuing the common good." Lutz (2009:4) adds:

Ubuntu (...) asserts that the common ground of our humanity is greater and more enduring than the differences that divide us. It is so, and it must be so, because we share the same fateful human condition. We are creatures of blood and bone, idealism and suffering. Though we differ across cultures and faiths, and though history has divided rich from poor, free from unfree, powerful from powerless and race from race, we are still all branches on the same tree of humanity.

Therefore, the sense of solidarity within the African community is reflected in the concept of Ubuntu as Broodryk, quoted in Dolamo (2013:2), defines it: "Ubuntu is a comprehensive ancient African world-view based on the values of intense humanness, caring, sharing, respect, compassion and associated values, ensuring a happy and qualitative community life in the spirit of family."

5.1 Reciprocity and human life processes

In African life, reciprocity is clearly noted in various events: when the child is born, people go with something to pay greetings to the newly born child; when the youths get married, people gather for celebration together with the family of the couples getting married. The people do not go to the wedding ceremony empty-handed; they go with something with them in their hands. They go with things such as money, pieces of clothes, tins of rice, to mention but a few, as their contributions to the event. Others contribute in preparing the place where the event is going to take place, the car that will carry the bride and the groom, and so forth. All these participations are clear indications of African solidarity to make the wedding event successful.

As Nnamunga (2013:136) rightly conceives it, "Marriage does not only involve interpersonal relations, but also inter-community relations. Marriage unites families, clans, communities, and cements alliances. Marriage always establishes very strong bonds between the individuals belonging to different families and clans, particularly when children are born." Mbiti (1969:133) further adds: "For African peoples, marriage is the focus of existence. It is the point where all the members of a given community meet: the departed, the living and those yet unborn. All the dimensions of time meet here, and the whole drama of history is repeated, renewed, and revitalized. Marriage is a drama in which everyone becomes an actor or actress and not just a spectator" (Cf. Ebun, 2014; Letseli, 2007:2; Kyalo, 2012:213). The two quotations from Nnamunga and Mbiti demonstrate that marriage is a communal activity which requires the participation of all members of society; it is not an event of an individual person or family.

When a person dies, the mourning is not just individual. The mourning is communal and is done by every individual within the respective community. The death of a person, in African context, is a ceremony. It is a time when people gather together to console one another following the loss of one member in the community. As it is in the wedding ceremony, the gathering is accompanied by eating and drinking. Onyedinma and Kanayo (2013:65) emphasize that "African sense of solidarity is also evident in the people's action when someone dies in a community or village. In most cases, people forego their personal businesses, in solidarity, not by sanction, to condone with the bereaved family and to assist in burial arrangements and funeral of the dead person. In this way, the entire community gets involved in the mourning rituals." (Cf. Ghansah, 2012; Mbiti, 2002:99-101; Mbiti, 2002b). Not only do people participate in the mourning ritual, the contributions are also made by every individual member of the community to facilitate the mourning for the departed individual. In that case, the event is not of the intimate nuclear family alone; rather, it is the event of the whole community. Every person within the community feels the obligation to participate in the facilitation of the event in order for it to be conducted in the required order.

The sense of solidarity in the African Ubuntu life is not only seen in specific events as the ones highlighted above; it is visible in almost the whole life of people within a particular community, even for smaller and things considered negligible. For example, Onyedinma and Kanayo (2013:64) explain what happens when the family builds a hut for the old individual or a person that is not well-to-do:

In a typical African community, building of a hut or a house for a kinsman especially of someone that is old or a person that is not well to do in the material sense of it, is often seen as a collective responsibility that calls for the contributions of many. More so, the whole community or kinsmen as the case may be, can mobilize a workforce to the farm of a dead relative or someone who is bereaved to help out in maintaining the farm and keep the bereaved family going. When such a job is to be done, the whole community turns out en masse with their supplies and music and proceeds to sing and dance their way through to the successful conclusion of each particular job. In this way, work is converted into a pleasurable productive pastime. Such type of solidarity is such a vital value that Africans cannot but work hard to sustain.

The participation of a person in church provisions counts for the way he/she will be treated in case of his own encounter with an event that requires the participation of other people. In this case, what the individual would like others to treat him/her when he/she faces an event requiring participation of others, he/she is required to treat others likewise. This is the binding principle of ubuntu lifestyle and the golden rule of African traditional religion.

5.2 Reciprocity and African hospitality

One important aspect that reflects the African reciprocity is that of notorious hospitality. Hospitality is paid to any stranger in the notion that an individual will one day become a stranger. The way in which an individual likes to be treated when they are a stranger, he/she does the same when strangers encounter him/her. Onyedinma and Kanayo (2013:66) amplify this concept of hospitality in the African saying: "The African sense of hospitality is one of the African basic elements of human relations that still persist today. Africans have symbolic ways of expressing welcome. These are in forms of presentation of kola nuts, traditional gin, native chalk, and so on. The Africans easily incorporate strangers into their own communities and often give them lands to settle. All these are given to visitors to show that they are welcomed and safe."

Among the Bena of Njombe in Tanzania, the practice of hospitality to guests is clearly noted in their saying "Umugenzi hilyo" (literal meaning: the guest is food). The same notion is found in the Swahili proverb that goes: "Mgeni njoo, mwenyeji apone" (literal meaning: the coming of a guest enhances the survival of household natives). This notion means that although the household members may have nothing to eat at the time when the guest arrives at their household, the coming of the guest will require the people in that household to strive hard and make sure that they get something for the guest to eat. This effort of getting something for the guest will also make people in that household have something to eat. In that case, people of the Bena ethnic group and Swahili speaking communities believe that the guest is not someone to hate, but to love and hail. Considering the example of the Bena ethnic group and Swahili speaking communities, one notes that the African sense of hospitality to strangers is done with the heart of sensitivity that one day the individual will need to be hosted by other people.

5.3 Reciprocity and respect for elderly people

Msengana (2006:90) writes:

In Africa, the older a person is, the more he or she is respected. However, people should recognize that Africans respect more the wisdom of an individual than his or her chronological age as such. For Africans, there is a strong correlation between age and wisdom. As African culture dominated by oral tradition, the elders are perceived as those who have the knowledge and accumulated a lot of experience. Age is the observable referent. Respect for elders implies a reciprocal relationship. As the younger respects the elder, the latter must, in return, take care of the former, provide him with advice and help him realize his full potential.

Msengana's (2006) statement capitalizes the fact that the relationship between people in Africa is mainly based on age. People who are older need to be respected irrespective of the tribes and clans they belong to. Respect for elderly people is not restricted to people of the same ethnic group; rather, it extends to the whole African society irrespective of country of origin or ethnic group. Despite the reciprocity of younger people respecting elders and elders providing wisdom to the young as suggested by Msengana (2006), young people also respect the elders in anticipation of being respected when they become elders. As they would prefer to be treated when they are in the elderly ages, they are supposed to treat their elderly people likewise when they are young. Therefore, this kind of reciprocity becomes a life-lived process that continues throughout the African people's lives and is handled from one generation to the other.

5.4 Reciprocity and the care for the extended family

In an African point of view, a family can be categorized into two groups, namely the nuclear family (the father, mother, and children) and the extended family (the grandparents, uncles, aunts, and other relatives of both sides). Children born in the nuclear family belong to both the nuclear family and the extended family. Regardless of the various social changes facing Africa, such as migrations from villages to cities, industrialization, inculturation, to mention but a few, the sense of family as comprising both the nuclear and the extended family has not been totally lost among Africans. In that regard, in African society, the concept of reciprocity can be understood from the family perspective before extending to other areas.

Magezi, Sichula and De Clerk (2010) assert that extended families in the Old Testament times are similar to contemporary African extended families. They state:

In both instances, the family combines all the benefits of a fully-fledged social security system without any bewildering red tape. The family is the refuge and the only institution providing some form of social security. All who belong to the bet 'ab or extended family share a history of a common biological figure. Their blood, their names and to a large extent their culture can all be traced back to a common ancestor or a set of ancestors (...). The extended family gives identity and a strong sense of family or clan solidarity. The relationships between members result, not only in words of affirmation, but especially in deeds of solidarity that include many of the attributes of a fully functioning social security system. Furthermore, there is a strong social support structure to meet the needs of the members at all times (...) (Magezi, Sichula & De Clerk, 2010:192-193).

The similarity between the Old Testament and contemporary African treatment of extended families indicates that apart from the respect for elderly people discussed previously, the extended family system is also reciprocal in nature within the African context. It does not matter whether one is well-off or not for him/her to bear the responsibilities of caring for others who are not part of the nuclear family. As Onyedinma and Kanayo (2013:66) note: "In traditional African culture, the weak and the aged, the incurable, the helpless, [and] the sick are affectionately taken care of in the comforting family atmosphere."

As Onyedinma and Kanayo have just pointed out, caring for people outside the nuclear family is an obligation that an individual is happy to perform. The individual cares in hope that he/she needs a similar care should something similar happens to him/her. Africans believe that being aged, being weak in whatever way, acquiring incurable diseases, being a widow, being an orphan, etc., are not aspects which one would like to have in his/ her own will. Rather, they are emergent aspects in one's life. In that case, every member of the community is likely to encounter such situations and eventually need the attention of other people. The vulnerability of every member of the community makes the African person feel the responsibility to care for others in a similar manner to one would like things to be done to him/her.

Conclusion

This article has demonstrated that to be an African is to belong to a particular community within the African society. It is in such belonging where the humanness of an individual becomes visible. A person is a person in relationship with other people. Personhood is reciprocal in the sense that what one wants other African people to do to him/her, he/she should do likewise to them. This way of acting demonstrates the golden rule embraced by most world religions and cultural traditions. According to African point of view, personhood is attainable only through Ubuntu, the African philosophy of life. This article has argued for Ubuntu philosophy being the cornerstone for African reciprocity despite its manifestation in other religious and cultural traditions worldwide. Although Christianity has been in Africa for hundreds of years, and its golden rule being taught in churches, it has hardly been the foundation of reciprocity. Hence, in the African context, Ubuntu philosophy should be seen as the foundation of reciprocity and the way of living in general.

References

Agulanna, C. 2010. Community and human well-being in an African culture, Trames 14(3):282-298. [ Links ]

Broodryk, J. 2005. Ubuntu management philosophy. Randburg: Knowres. [ Links ]

Bruni, L.; Gilli, M. & Pelligra, V. 2008. Reciprocity: Theory and facts. International Review of Economics 55:1-11. [ Links ]

Chibvongodze, D.T. 2016. Ubuntu is not only about the human! An analysis of the role of African philosophy and ethics in environment management. Journal of Human Ecology 53(2) [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2016.11906968. [ Links ]

Curle, N. 2015. A Christian Theological Critique of uBuntu in Swaziland. Conspectus 20:2-42. [ Links ]

Dolamo, R. 2013. Botho/Ubuntu: The heart of African ethics. Scriptura 112(1):1-10. [ Links ]

Ebun, O.D. 2014. Reflection on an African traditional marriage system. Journal of Social Sciences and Public Affairs 4(1):94-104. [ Links ]

Enslin, P. & Horsthemke, K. 2004. Can Ubuntu provide a Model for Citizenship Education in African Democracies? Comparative Education, 40(4):545-558 Available: DOI: 10.1080/0305006042000284538. [ Links ]

Falk, A. & Fischbacher, U. 2006. A Theory of Reciprocity. Games and Economic Behaviour, 54:293-315. [ Links ]

Gathogo, J. 2008. African philosophy as expressed in the concepts of hospitality and Ubuntu. Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 130:39-53. [ Links ]

Ghansah, W. E. 2012. Encounters between Christianity and African traditional religion in Fante funeral practices: A critical discussion of the funeral practices of the Fantes in Ghana. M. Phil in Intercontextual Theology, University of Oslo, Oslo Norway.

Kyalo, P. 2012. A Reflection on the African traditional values of marriage and sexuality. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development 1(2):211-219. [ Links ]

Letseka, M. 2012. In defense of Ubuntu. Studies in Philosophy Education 31:47-60. DOI: 10.1007/s11217-011-9267-2. [ Links ]

Letseli, T. 2007. African & biblical marriage and family. Namibian Bible Conference Gross Barmen Resort, Namibia, 23-27 September 2007.

Lutz, D.W. 2009. African Ubuntu philosophy and philosophy of global management. Journal of Business Ethics 1-12. DOI: 10.1007/s10551-009-0204-z.

Magezi, V., Sichula, O. & De Clerk, B. 2010. Communalism and hospitality in African urban congregations: Pastoral care challenges and possible responses. Practical Theology in South Africa 24(2):180-198. [ Links ]

Maqutu,T. M. (2018) African philosophy and Ubuntu: Concepts lost in Translation. Master of Law Thesis, University of Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

Mandova, E. & Chingombe, A. (2013) The Shona proverb as an expression of unhu/ubuntu. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development 2(1):100-108. [ Links ]

Manganyi, J. S. & Buitendag, J. 2017. Perichoresis and Ubuntu within the African Christian context. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 73(3): a4372. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i3.4372. [ Links ]

Mbiti, J.S. 2002. "A person who eats alone dies alone": Death as a point of dialogue between African religion and Christianity. In Mwakabana, H.A.O.(ed.). Crises of Life in African Religion and Christianity. LWF Studies 2, Geneva: Lutheran World Federation, 83-106. [ Links ]

______________. (b). 2002. Death in African Proverbs as an Area of Interreligious Dialogue. In Mwakabana, H.A.O. (ed.). Crises of Life in African Religion and Christianity. LWF Studies 2, Geneva: Lutheran World Federation, 107-126. [ Links ]

______________. 1969. African religions and philosophy. London, Heinemann. [ Links ]

Mligo, E.S. 2020. Rediscovering Jesus in our places: Contextual theology and its relevance in contemporary Africa. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock/Resource. [ Links ]

Msengana, N.W. 2006. The significance of the concept "Ubuntu" for educational management and leadership during democratic transformation in South Africa. PhD Thesis, University of Stellenbosch, South Africa. [ Links ]

Nnamunga, G.M. 2013. The theological anthropology underlying Libermann's understanding of the "evangelization of the blacks" in dialogue with the theological anthropologies of the East African context: Implications for the contemporary East African Catholic Church. PhD Thesis, McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts, Duquesne University.

Onyedinma, E.E. & Kanayo, N.L. 2013. Understanding human relations in African traditional religious context in the face of globalization: Nigerian perspectives. American International Journal of Contemporary Research 3(2):61-70. [ Links ]

Rakhshani, Z. 2017. The golden rule and its consequences: A practical and effective solution for world peace. Journal of History Culture and Art Research 6(1):465-473. [Online]. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.7596/taksad.v6i1.754. [ Links ]

Van Norren, D.E. 2014. The nexus between Ubuntu and global public goods: Its relevance for the post 2015 development agenda. Development Studies Research 1(1):255-266. [Online]. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21665095.2014.929974 [ Links ]