Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

On-line version ISSN 2413-9467

Print version ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.7 n.1 Stellenbosch 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2021.v7n1.a25

GENERAL ARTICLES

"Now Deborah, a prophetess, a fiery woman..." A gendered reading of Judges 4:4

Ntozakhe Simon Cezula

Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa. cezulans@sun.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article is inspired by an article published by Reverend Bongani Finca of the Uniting Presbyterian Church in Southern Africa (UPCSA) in 1994. Rev. Finca's article is an adaptation of an address he gave on gender inequality at a Decade conference in East London, South Africa. Specifically, this article is challenged by his remark that he knows a number of men who struggle with the gender exclusivity in the language of the Church, especially in the reading of the liturgy. He then continues to say; "how many of us are working seriously at finding alternatives and revising the liturgy itself to be more gender sensitive". It is this remark that prompts this article to swing into action. For that reason, this article responds to Rev. Finca's challenge from the biblical point of view. This article thus intends to read Judges 4:4 alternatively. It intends to dispute the designation of Deborah as the wife of Lappidoth, arguing that it legitimises patriarchy.

Keywords: fiery woman; ideology of patriarchy; naming of married women; Vulgate; wife of Lappidoth

Introduction

The years 1988-1998 were declared by the World Council of Churches (WCC) as the WCC's Decade of the Churches in Solidarity with Women. At a Decade conference in East London, South Africa, Rev. Bongani Blessing Finca addressed the audience on gender equality. Among many remarks he made, he said:

I know a number of men who are struggling with the exclusivity in our language, especially in our reading of the liturgy, with its one-sidedly male image of God - the "Almighty Father, King, Lord and Master of mankind" sort of language. But how many of us are working seriously at finding alternatives and revising the liturgy itself to be more gender sensitive" (1994:192).

The remark that he knows men who struggle with the exclusivity in "our language, especially in our reading of the liturgy, with its one-sidedly male image of God", I view as just information. But that "...how many of us are working seriously at finding alternatives and revising the liturgy itself to be more gender sensitive", I view as definite mobilisation. This article thus enlists itself to help find alternatives. As a little contribution to the discourse on gender inequality in the Church, the article intends to engage in an alternative reading of the characterisation of Deborah in Judges 4:4. Specifically, the article contests the designation of Deborah as the wife of Lappidoth. The article thus hypothesises that this designation "corrects" what it deems a perverse characterisation of Deborah in the Hebrew text to conform to the reigning ideology of patriarchy, and thus puts a woman in her place. By this perspective, the article hopes to be rising to the occasion that Rev. Finca has decried as inaction against the exclusion of women. As the discussion unfolds, a brief presentation of Rev. Finca's article will start the conversation. Because Finca highlighted the collaboration between African tradition and Christian tradition in the exclusion of women, it might be helpful to briefly demonstrate how Xhosa tradition contributes by the naming of married women. This might help in placing the naming of Deborah as Lappidoth's wife into perspective. Further, since Deborah's designation as Lappidoth's wife has been hypothesised as a "correction" of a "perverse" characterisation, a description of perversion as understood in this article will be presented. Thereafter, an alternative reading of Judges 4:4 will follow. Bringing the discussion to a close, remarks concerning the contribution of this article to the discourse that Rev. Finca kick-started will be made.

Rev. Finca's article

Rev. Bongani Finca's "article is adapted from an address he gave at a Decade conference in East London, South Africa" (1994:191). An informative background to this article is provided by Busi Mbatha when she says:

Worldwide evaluations by churches towards the end of the 1980s showed that most churches had failed to abide by the United Nations Decade for Women (1975-1985). No progress had been made in what was perceived to be the Biblical call for justice and the building of a genuine community between women and men. For this reason, the World Council of Churches (WCC) General Committee on Women met in Geneva in January 1987 and declared the Ecumenical Decade of Churches in Solidarity with Women over the period 1988-1998. The Decade offered a second opportunity for churches to achieve the principles of justice and genuine community ... The SACC [South African Council of Churches], at the request of the WCC and in conjunction with Women's Ministry, coordinated the launch of the Decade in South Africa (1995:51) ... Male church leaders resisted the change in existing male-female relationships that the Decade promised. A handful of "progressive" ministers and their wives were usually outvoted by more conservative elements. Save for the Western Council of Churches, other regional councils were negative towards the Decade (1995:53).

These are the circumstances out of which Finca's article arose. He introduces his article by indicating that he was borne "in an ashamedly patriarchal society". He was:

... socialized from childhood into a system which does not just discriminate against women and treat them as second-class human beings but goes further than that and appropriates to men the right to define and determine the entire social order, the right to decide what is normal and what is abnormal, the right to set up acceptable standards of behaviour - and to do all this from a man's point of view. In such a society when you challenge the sexist stereotypes, you are deemed to be unwell, abnormal, in need of help. This is not only how men see and judge you, but how the entire society, including women, sees and judges (1994:191).

He continues to tell that at an early age he became a Christian. His faith in Jesus Christ helped him to recognise the many abnormalities in our social and political life. Very early in his life he recognised racism as evil and as contrary to the Christian way of life, and he enlisted himself in the struggle against it. Very early in his life he recognised classism and the class stratification of society as evil and as contrary to the Christian way of life, and he enlisted himself in the struggle for an egalitarian society. He rejected very strongly all forms of discrimination between people which our sick society was attempting to socialise us into accepting as a normal way of life - what was then called the South African way of life. But there was one notable exception: He remained a patriarch. Instead of challenging how African tradition defined the status of women, he found himself jumping to the defence of the status quo, blaming the colonial and missionary interpretation for misreading African tradition and culture. He then makes a profound statement saying:

The Judaeo-Christian tradition, which had helped me so well to deal with other prejudices in my life, failed desperately to liberate me from my patriarchal biases. The Bible that I read did nothing to challenge me to repent. The community of the church did not socialize me into a new redemptive and liberative lifestyle. It followed itself the prototype of the old Israel: it was maledominated, gender-insensitive, perpetuating the stereotypes of the subordination of women. And it went even further than the non-Christian world in equating patriarchy with the will of God (1994:191).

Evocative is the statement that "the Bible that I read did nothing to challenge me to repent. The community of the church did not socialize me into a new redemptive and liberative lifestyle. It followed itself the prototype of the old Israel: it was male-dominated, gender-insensitive, perpetuating the stereotypes of the subordination of women." I have two questions concerning this statement. The first one is, did the Bible really fail him or did the interpretations he received fail him? Secondly, is Judges 4:4 part of "the old Israel" as he describes as "male-dominated, gender-insensitive, perpetuating the stereotypes of the subordination of women"? These two questions will be answered later in the concluding remarks. The straw that broke the camel's back is the question "how many of us are working seriously at finding alternatives and revising ... to be more gender sensitive". That is the reason why this article enlists itself against gender inequality in the church. Finca's query against the Bible is corroborated by Mbatha when she comments on the successful intimidation of women from participating in the Decade. She says: "The patriarchal status quo in the church was further entrenched by Biblical rationale - a useful cultural weapon in the hands of ministers bent on keeping women submissive. For example, they referred to Paul 3:1-71 which exhorts women to respect men, respect government, respect the law and so on" (1995:53). The point is reinforcing Rev. Finca's charge that the Bible did not help him to abandon male chauvinism. Mbatha argues that the Bible has been an active culprit in the oppression of women. This article would like to argue that maybe not in all instances. Sometimes it might be the translations and not the Hebrew Bible, in the case of the so-called Old Testament. It is in this light that this article will be reading Judges 4:4. However, before we read Judges 4:4, let us pay attention to another factor that Rev. Finca brought forward; our traditions. He contends that "we have to face the reality that women are discriminated against within the church and within the African tradition" (1994:192). This illuminates the collaboration that takes place between our traditions and the reading of the Bible. To demonstrate this point the discussion will start by examining Xhosa culture in naming married women in the next section, and then the naming of Deborah as Lappidoth's wife in the section on Judges 4:4.

Naming of married women in Xhosa tradition

In a doctoral dissertation, Sakhiwo Bongela examines the custom of isihlonipho (respect) among amaXhosa. Underpinning the custom of respect among the traditional Xhosa people, he says:

It goes without saying that the cultural fabric of the Xhosa society is interwoven with cultural aspects, one of which is hlonipha. From time immemorial, it was a most valuable asset on which the moral and social survival of the nation depended. Every member of society was made to feel obliged to honour the hlonipha custom. Because of this commitment the moral fibre of society was always good. The teachings and rules that compelled and encouraged adherence to this hlonipha practice, were as good as a code of ethics or a constitution of the country. The sanctions, the penalties, and all retributory measures that were applied upon failure to comply with these rules, were accepted and obeyed. This made the Xhosa nation culturally one of the most stable nations in the Southern African region (2001:18).

One of the aspects of respect he identifies is how married women were called. It was and still is disrespectful to call a married woman by her maiden name. She has to be called in a respectful manner. Describing the naming of a newly married woman, he states as follows:

This new status which carries a mark of respectability, is widely recognised and the community members also address her as uMamJwarha, umkaThobile - (MamJwarha, Thobile's wife), or uMaNkilane, umolokazana kaDumile - (MaNkilane, Dumile's daughter-in-law) (2001:46).

The lady here is referred to in two names. The first one is her clan-name and the second one is her husband's name. Alternatively, the first name is her clan-name and the second one is her father-in-law's name. So, to respectfully refer to a married woman, one first mentions her clan-name and secondly her husband's name or her father-in-law's name. She is thus, so-and-so's wife or so-and-so's daughter-in-law. The first name, which is the clan-name, is the same name that her father is called by; it is just prefixed with a feminine prefix. In fact, clan names are officially derived from the paternal line of the offspring. Explaining the calling of a woman by clan name, Bongela, says: "To a married woman the use of isiduko (clan name) is very important for it carries a mark of dignity and respect. It remains permanent until the woman reaches the very old woman's stage" (2001:47). The two names by which she is referred to, the clan-name and her husband's name or her father-in-law's name, are names that carry male connotations. Her names invoke the men in her background. Any community member who is not her family who refers to her by her maiden name and does not call her in the prescribed manner, is liable of retribution. Concluding their discussion, Bonisiwe Zungu and Nomvula Maphini remark as follows concerning the naming of newly married women:

In Xhosa culture it is evident that naming affects individual identity and behaviours. One is expected to live up to his/her name ...

Newly married brides in the Xhosa societies believe that re-naming changes their individuality, they have to try please their new family. They have to behave according to their new names to meet the expectations of the name givers. New brides are expected to neutralise the situation within the family. They are expected to bring peace where there is chaos and give love and respect to everybody within the family. They have to be beautiful people inside and out. They have to bear children that will carry down the family name. These expectations must be met at all costs. This puts unnecessary pressure on the women (2020:75).

The last remark that the expectations raised by the naming of the bride put "unnecessary pressure on the women" does not evince good gender relations. With the advent of Modernity, the clan names were replaced with surnames for official identification. But still, the woman takes the husband's surname after marriage. Writing on this issue of surnames, Matsatsi Grace Makhubedu says:

Democracy in South Africa has also brought in some changes, especially among women. Today, some married women prefer to retain their maiden names: something which did not exist among African women in the past. Such women use double-barrelled surnames because they don't want to lose their identity. For example, Dr Manto Tshabalala Msimang, (the present Minister of Health in South Africa) (2009:10).

The fact that "they don't want to lose their identity" hints to a resistance of some sort to custom. However, the general state of affairs seems to be expressed by Zungu and Maphini when they say, "the re-naming of Xhosa brides has not been affected by cultural evolution, modernity and changes which come with time" (2020:68). While the naming focuses on the Xhosa tradition, it is true that in some cultures as well women take the surnames of their husbands while the husbands will not include the wives' surnames in their identity. This statement confirms the role of culture in the unequal treatment of men and women. Just as the naming of women as discussed above is viewed as patriarchist, so is the naming of Deborah as Lappidoth's wife. Having made this assertion, let us now move on and examine this articles' use of the concept perversion.

Perversion

According to The Encyclopedia of World Problems and Human Potential "Perversion is a type of human behaviour that deviates from that which is understood to be orthodox or normal. Although the term perversion can refer to a variety of forms of deviation, it is most often used to describe sexual behaviours that are considered particularly abnormal, repulsive or obsessive" (Online 1994). This article is not focusing on "sexual behaviours that are considered particularly abnormal, repulsive or obsessive." Rather, the article hovers over a deviation from "orthodox or normal". To make this articles' use of perversion apprehensible, let us refer to the activities of the Inquisition as an example. The Inquisition was "a special ecclesiastical tribunal for tracking down, examining, and punishing heretics ... and fed on the conviction that heresy, as a threat to social order, had to be suppressed" (1991:121). It is important to note that heresy is viewed as "a threat to social order". For that reason, it needs to be suppressed. A telling example of a heresy is the case of Galileo Galilei. The Inquisition investigated Galileo Galilei's writing on the sun being in the centre and the earth moving around it, against "deeply held principles of biblical interpretation, as well as the traditional cosmological opinions of the church fathers" (2003:3360). According to Tamar M. Rudavsky, Galileo held controversial views that threatened the ideological fabric of his religious institution and thus "Galileo was accused of heresy" (2001:611-631). If we remember, above perversion was described as "human behaviour that deviates from that which is understood to be orthodox or normal". Of great significance is how Pope Urban VIII viewed this "heresy". He instructed a special commission he appointed to investigate Galileo's book that it must "weigh 'every smallest detail, word for word, since one is dealing with the most perverse subject one could ever come across.'" In a similar vein, Pope Urban VIII is captured by Sarah Bonechi saying, "Galileo 'had dared to enter where he should not'; . proclaiming a 'doctrine . perverse in the highest degree,' occupying himself indeed with the 'most perverse material that one could ever have in one's hands'" (2008:88). As far as the Pope was concerned, Galileo's ideas were perversion. He deviated from that which was understood to be orthodox or normal and thus challenged the status quo. This is the kind of perversion this article refers to when it hypothesises that Deborah's naming as Lappidoth's wife was a "correction" of a "perverse" characterisation.

However, it needs to be clarified that the article does not argue that the translation theory of the translator intentionally imposed patriarchy on the translation, since there is no documentary evidence thereof. Instead, he could have been unconsciously influenced by his patriarchal culture which would view an independent woman as "perverse" behaviour. This will be made clear when we read Judges 4:4. Let us now proceed to read the text.

An alternative reading of Judges 4:4

Judges 4:1-3 describes the situation of the Israelites after the death of Ehud, the previous judge who delivered Israel from Eglon, king of Moab. The Israelites, again, did what was evil in the eyes of the Lord. The Lord therefore allowed a king of Canaan to oppress them. They cried to the Lord. Deborah, as the judge at the time, led the deliverance of Israel from the Canaanites. Judges 4:4 then, our focus text, introduces Deborah. However, before we read Judges 4:4 I would like us to take heed from a statement by Sharon H. Ringe in a chapter in the Women's Bible Commentary: Expanded Edition. Ringe says:

It is important also to recognize that no modern interpreter comes to the Bible directly. Rather, she or he is influenced (often without being aware of it) by centuries of interpretation whose results become nearly indistinguishable from text itself. If women are to be able to arrive at a fresh hearing of the biblical traditions as they relate to women, an important part of the task is to be aware of that history of interpretation (1998:6).

Ringe says modern readers of the Bible do not come directly to the Bible. They come via centuries of interpretation whose results become nearly indistinguishable from the text itself. I would like to add that they also come via their own traditions and customs, which sometimes also become synonymous to the text. For this reason, it might be proper to read Judges 4:4 backwards, that is, start with our own translations backwards to the Hebrew text, starting by reading a Xhosa Bible;2 a Protestant Bible, to be specific. After a Xhosa Bible we will read an Afrikaans Bible, the 1956 translation. We will then move backwards to an English Bible; the 1611 King James Version. From an English Bible we will move still backwards to a Latin Bible; the Vulgate.3 From the Vulgate we will move even more backwards to the Greek Bible; the Septuagint.4 The Greek translation is the first translation of the Hebrew Bible into another language. And, finally, we will move beyond the Septuagint to the Hebrew Bible, the originator.

Translations

The first translation to read is the new Xhosa Bible translation of 1996. This translation presents Judges 4:4 as follows:4Ke kaloku umshumayelikazi uDibhora umkaLapidoti waba yinkokheli kwaSirayeli ngelo thuba (It so happened that a woman preacher, Deborah, the wife of Lappidoth, became a leader in Israel at that time). This is almost a literal translation of this verse. In this verse, Deborah is presented as a preacher and not a prophetess. This is, however, different from the 1859 Xhosa translation which refers to Deborah as a prophetess. By omitting the title of prophetess, the 1996 translation, already, takes something away from the status of Deborah. Never mind, future references to a Xhosa translation will be referring to the 1859 translation. It then continues and describes her as the wife of Lappidoth, which is the main interest of this article. Since Xhosa married women are named after their husbands, this translation is a normal designation of a married woman to a Xhosa reader. This means there is nothing suspicious about this translation. It is hand and glove with Xhosa culture. It goes down smoothly to a Xhosa reader. In this sense, the text confirms the reader's culture to refer to a woman in terms of her husband and, thus, gives the impression that the identity of a married woman is "a shadow of her husband's identity".

The next translation is the 1953 Afrikaans translation. In this translation, Judges 4:4 states: "En Debora, 'n profetes, die vrou van Láppidot, het in dié tyd Israel gerig" (And Deborah, a prophetess, the wife of Lappidoth, judged Israel in this time). The 1953 Afrikaans translation agrees with the 1859 Xhosa translation that Deborah was a prophetess and the wife of Lappidoth. Although the author of this article is not well-versed with Afrikaner culture, a comment by Carli Coetzee about Antjie Krog, an Afrikaans poet, hints on patriarchal traces in the naming of Afrikaner married women. Describing Krog's book, Coetzee says:

The book, as is well known, is based on the reports done for the South African Broadcasting Service, where Krog worked under the name Antjie Samuel - her married name. The copyright of the book is in the name of Antjie Samuel; the biographical note on the back describes Antjie Krog, who it says reported 'as Antjie Samuel'. This divided identity, this double signature, is more than a case of a married woman making a choice to publish under her maiden name (which is, of course, always still her father's name) (2001:686).

Coetzee argues that Krog's "divided identity" is more than a choice of a married woman to publish by her maiden name. Despite that, I would like to stick to this case of a married woman's choice. She calls Krog's identity a divided one and a double signature. It is the surname of the husband and her maiden name, "which is, of course, always still her father's name". Her surnames invoke the men in her background. On this basis, this article feels justified to say the naming of Deborah after Lappidoth may not raise eyebrows for an Afrikaner reader. The translation agrees with the Afrikaner custom of naming married women.

The next translation is an English translation; the King James Version (KJV: Authorised). According to the KJV, Judges 4:4 says: "And Deborah a prophetesse (sic), the wife of Lapidoth, thee judged Israel at that time". The KJV agrees with the previous translations in both presenting Deborah as the prophetess and wife of Lappidoth. Again, the author is not well-versed with the English culture. However, Julia C. Lamber does inform in this regard when she says:

... the proposition so positively stated in legal encyclopedias that a woman upon marriage takes her husband's surname actually reflects one more "unknowing" or "unintended" discriminatory practice which perpetuates male dominance solely by the fact of maleness ... (1973:779) Indeed, "in England, custom has long since ordained that a married woman takes her husband's name ..." (1973:783).

If Lamber's statements are anything to go by, this article feels justified to state that this translation and the English custom of naming married women are a hand and a glove. For that reason, this translation can be read by an English reader without further ado.

The next translation to read is the Vulgate. According to the Vulgate: "erat autem Debbora prophetis uxor Lapidoth quae iudicabat populum in illo tempore (And there was at that time Debbora, a prophetess, the wife of Lapidoth, who judged the people)." The Vulgate refers to Deborah as uxor Lapidoth (wife of Lappidoth). There is not much I will say except to say the Vulgate confirms the previous translations and is the oldest so far. Reference to the Vulgate will be made soon here below. Let us then proceed to the Septuagint. According to the Septuagint, Judges 4:4 is as follows: "Και Δεββωρα γυνη προφητις γυνη Λαφιδωθ, αυτη εκρινεν τον Ισραελ εντω καιρω εικενω" (And Debbora, a prophetess, the woman of Lapidoth, she judged Israel at that time). The Septuagint also describes Deborah as a prophetess (γυνη προφητις; gene prophêtis). It agrees with all the previous translations except the 1996 Xhosa translation which describes her as a woman preacher. The γυνη (gene) in γυνη προφητις (gene prophêtis) is translated as "a woman" and thus a woman prophet. Our interest in this verse is Lappidoth. For that reason we will focus on the phrase that includes Lappidoth. The phrase is γυνη Λαφιδωθ (genê Laphidóth). Γυνη (Genê) in the previous phrase has been translated as "a woman". If it is translated in the same manner in the latter, it will read as "a woman of Lappidoth". However, as we have seen in all the previous translations, it is translated as "wife of Lappidoth" instead of "woman of Lappidoth".

The word γυνή is a feminine, singular, and nominative noun. According to the Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament, γυνη (genê) means "an adult female person of marriageable age - woman" (1996:107). Λαφιδωθ (Laphidóth), on the other hand, is a masculine, singular and genitive noun meaning "of Lappidoth". The translation can either be "a woman of Lappidoth" or "a wife of Lappidoth". Joy A. Schroeder interprets the translation "with the possibility that the translator regarded "Lappidoth" as a place name" (2014:5). For the first time, since we started looking at different translations, there is ambiguity concerning Lappidoth. Schroeder then remarks that most Christian translations follow the understanding of the phrase as found in the Vulgate. Schroeder thus, implies that the Vulgate distorted the original meaning of the phrase. My observation, also, is that the Vulgate is the last translation that unambiguously translates as "wife of Lappidoth". If we move from back forwards, the Vulgate is the first translation to unambiguously translate as "wife of Lappidoth". For this reason and the sake of the discussion, this translation may also be referred to as the Vulgate translation. However, even if Schroeder introduces this ambiguity, the readers of the previous translations are highly likely to opt for the popular translation because it agrees with their customs' presuppositions. In such a situation, Schroeder's interpretation does not have persuasive power thus far. In this case, the popular translation stands. Let us now go to the original language of this text, Biblical Hebrew.

The Hebrew text

The previous section introduced the discussion by giving the background to Judges 4:4; outlining Judges 4:1-3. This introduction ended by stating that Judges 4:4 introduces Deborah.

Judges 4:4 in the Hebrew Bible is expressed as follow:

שׁפְֹטָה אֶת־יֹשְׂרָאֶל בָּעֵת הַהִיא וּדְבוֹרָה אִשָּׁה נְבִיאָ֔ה אֵשֶׁת לַפִּיד֑וֹת הִיא

The first phrase has five words which all refer to Deborah. The first word is l (ve meaning "and"). It is a conjunction introducing the sentence. The second word is Deborah, which is her name. It is introduced by a conjunction l (and) and thus reads "And Deborah". Deborah is a proper noun which is feminine singular. This morphological structure corresponds with the grammatical rules of Hebrew since she is a woman, and she is one. The third word is אשִָּׁה (ishah), meaning a woman. This word is a common noun which is feminine singular. Because this word describes Deborah who is a woman and singular, its morphological structure corresponds with Biblical Hebrew (BH) grammar. The phrase thus reads, "And Deborah, a woman". The next word is נבְיִאָ֔ה (nebiah), meaning a prophetess. It is a common noun which is feminine singular. Because it also describes Deborah who is feminine and singular, its morphological structure corresponds with BH grammar. The phrase thus reads, "And Deborah, a woman, a prophetess". The next word is אשֵֶׁת לפַּיִד֑וֹת (êshet lappidoth). According to the previous translations, it means the wife of Lappidoth. Êshet is a feminine singular construct, corresponding to the gender and number of Deborah. The next word is Lappidoth and, according to Logos Bible Software, is a masculine singular noun. For the first time, we encounter a masculine singular word that describes Deborah. Both BH dictionaries which were consulted describe the word as a proper noun masculine singular, like Logos, and explain it as "the husband of Deborah" (CHALOT; BDB). In terms of this information, the phrase will thus read, "And Deborah, a woman, a prophetess, the wife of Lappidoth". However, the explanation of Lappidoth is not unambiguous. Before we get into that, let us translate the rest of the sentence which says: הִיא שׁפְֹטָה אֶת־יֹשְׂרָאֶל בָּעֵת הַהִיא (hi' shoftah et-israel baët hahi'). It can be translated as "she was judging Israel at that time". The whole verse, in terms of the explanation of Lappidoth that we have thus far, reads: "And Deborah, a woman, a prophetess, the wife of Lappidoth, she was judging Israel at that time". Let us now revisit the explanation of Lappidoth. I will now change the spelling of Lappidoth to lappidoth because we now start from a clean slate.5

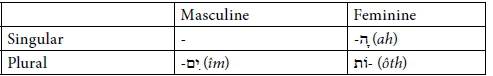

Before we engage with lappidoth, let us look at the grammatical features of BH nouns. According to Van der Merwe et al., nouns are marked in terms of gender, i.e. masculine or feminine, and number, i.e. singular, plural or dual (1999:§24) (Dual nouns are not included here below). The gender and number of nouns may be recognised by the following endings:

Masculine singular nouns form the root noun. If we look at this table, the word lappidoth corresponds with feminine plural. Deborah's name is feminine singular in form and refers to one woman. From a Biblical Hebrew morphological point of view, lappidoth is a feminine plural form.

It is lappïd + 6th. However, according to the lexicons it is a masculine singular personal name. This is the primary reason why this article senses an anomaly about láppïdoth. Nevertheless, an examination of the use אשֵֶׁת in the OT and some BH grammatical explanations for the gender of nouns might provide useful knowledge.

אשֵֶׁת in OT and the gender of לַפִּידוֹת

Firstly, let us examine the use of אשֵֶׁת in the OT. BDB translates אשִָׁה (ishäh) as "woman" or "wife". Ëshet is a singular construct state of ishäh. In the MT there are ninety-eight instances of the ëshet form. Of these ninety-eight instances, ten, excluding Judges 4:4, are translated as "woman of" instead of "wife of". Without demonstrating all ten instances, a few may illustrate the point. Deuteronomy 21:11 refers to אשֵֶׁת יפְתַ־תּאַֹר (ëshet yefat-to'ar). This expression can be translated as "a woman of beautiful appearance". Two times, 1 Samuel 28:7 refers to אשֵֶׁת בַּעלֲתַ־אבֹ (ëshet ba'alat-öv) which can be translated as "a woman of the spirit of the dead" or "a woman who is a medium". Jeremiah 13:21 refers to אשֵֶׁת ל דֵָה (ëshet ledäh) which can be translated as "a woman of giving birth" or "a woman in labour". Lastly, Psalm 58:9 refers to נפֵֶל אשֵֶׁת (nëfel ëshet). Nëfel means miscarriage and the expression can be translated as "miscarriage of a woman". Now, considering that approximately 90% of instances are translated as "wife of", one may conclude that this can be used to justify the translation of Judges 4:4 as "wife of Lappidoth". However, it can also be argued that the total of approximately 10% cannot be perceived as mere exceptions which can be ignored. On this basis, this is not an adequate argument to justify the translation of Judges 4:4 as "wife of Lappidoth".

The second issue to explore are the BH explanations for noun gender. According to Van der Merwe et al., "when the gender of a noun is described in BH, the level of description must be indicated, namely morphological, syntactic or semantic". The morphological level indicates gender by an ending. The syntactic level indicates gender by means of correspondence with other words such as adjectives and verbs. These levels are grammatical. The semantic level relates to the actual sex in real life and thus not grammatical (1999:§24.2.). This level operates in an extra-lingual reality (Kroetze 1994:146). It does not appeal to grammar to determine gender but to real life conditions. Concerning לַפּדוֹת (lappidoth), dictionaries say "name of a person (masculine)" (CHALOT), proper name masculine, husband of Deborah (DBD). The masculine gender indicated by these lexicons cannot be explained grammatically. This means morphological and syntactic explanations cannot explain the masculine gender of Lappidoth as indicated by the lexicons. That leaves one option, semantic explanation. For example, father in BH is אַב (av) and woman is אשִָׁה (ishäh). Their plural forms are אָב ֹ וֹת (ävöt) and אנָשִָׁים (änäshim), respectively. אַב (av) is masculine singular and אָב ֹ וֹת (ävöt) is feminine plural. אשִָׁה (ishäh) is feminine singular and אנָשִָׁים (änäshim) is masculine plural. These are morphological explanations. However, in the plural form these morphological explanations do not correspond with the real-life sex of fathers and women. In this situation, one appeals to the semantic level to explain the masculine gender of ävöt despite the feminine ending. The same with änäshim, one appeals to the semantic level to explain the feminine gender of änäshim despite the masculine ending. Accordingly, one can argue that this is similar to the case of lappidoth. However, what is similar is not the same. In the case of ävöt and änäshim, they are plural forms of words which are established as referring to "father" and "woman", so the opposite genders in grammar necessitate their overlooking and appeal to a real-life situation. However, in the case of lappidoth there is no prior knowledge that Deborah had a husband which can prompt the disregard of the grammatical information on the gender, and even the number, of the word lappidoth in Judges 4:4.

Additional factors

The use of אשֵֶׁת in the OT and the appeal to a semantic explanation are not adequate to justify the translation of אשֵֶׁת as "wife of" in Judges 4:4. Maybe looking at a few commentaries might provide us with the picture of the discourse. F. Delitizsch and S. F. Keil represent a category which does not even mention the name Lappidoth (1973:301). For them, thus, there is no exegetical dispute in Judges 4:4. Arthur Cundall takes the marital status of Deborah for granted and thus just defends the fact that "Deborah's husband" appears nowhere else. According to him, "Deborah's husband" is not the only man that is outshone by a woman, pointing to Barak who is second after Deborah in the narrative (1968:82-83). For Athena Gorospe, in the culture of Deborah's time, "being the 'wife of' somebody would define a woman's identity and role". She takes for granted the marital status of Deborah. For her, the issue is that, despite the mention of Deborah's domestic role, Deborah's identity is cast in very different terms, for her role in the community is given prominence" (2016:60). For some, the exegetical issue in Judges 4:4 is whether Lappidoth is also Barak or not (Soggin 1987:64; Cundall 1968:83; ABD). Robert Boling suggests that Lappidoth is probably a nickname for Deborah's husband who tradition knew mainly as Baraq and hence the name Lappidoth does not appear again in the narrative. According to him, the name means roughly "Flasher" with an abstract (not feminine plural) ending (1969:95). The abstract ending appears again in the ABD: "it probably is a feminine abstract form [Heb-ót] of lappïd, meaning "torch" or "lightning". Considering that lightning can be seen, and that abstract relates to things that cannot be perceived by any of the sense organs, namely, eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and skin (Van der Merwe et al. 1999:§23), this explanation is not convincing. Susan Niditch, while acknowledging the possibility of translating êshet lappidoth as "wife of Lappidoth", she also asserts that "the common translation 'wife of Lappidoth', while possible, seems to miss the point concerning Deborah's charisma (2008:64). The few that we have examined take Deborah's marital status for granted or do not unreservedly dispute Lappidoth as the husband of Deborah. Let us now take the argument further on Lappidoth.

Above it was clearly stated that lappidoth is feminine plural. This article argues that the gender of lappidoth can adequately be explained by morphological and syntactic levels. Morphologically, the form speaks for itself. Syntactically, the word agrees with Deborah and אשֵֶׁתwhich are female. Daniel and Cathy Skidmore-Hess remark as follows concerning Lappidoth:

. the name given to Deborah's presumed husband, lappidot, is anomalous, for if it is indeed a proper name, it is one that appears nowhere else in the Bible, and it is a feminine noun meaning "torches" (2012:3).

In Bantu culture, it is derogatory and humiliating to call a man by a feminine name. This might be another reason for interest in this verse. In Judges 15:4, לפַּיִדִים (lappïdïm) is used as a masculine plural of לפִַּיד (lappïd meaning lightning), agreeing with Samson who is masculine. The same argument we make in Judges 4:4. Interestingly, BDB translates láppïd as "torch". It describes it in many ways: simile of conquering power of chiefs of Judah; simile of eyes of angel in vision; simile of flashes reflected from darting chariots. Would symbols like conquering power and darting chariots not be compatible with the character of Deborah as a military leader?

The Rabbinic tradition offers a thought-provoking translation. Writing about seven prophetesses, the Babylonian Talmud - Mas. Megilah 14a writes as follows:

"Seven prophetesses". Who were these? - Sarah, Miriam, Deborah, Hannah, Abigail, Hulda and Esther . "Deborah", as it is written, Now Deborah a prophetess, the wife of Lapidoth.23 What is meant by a woman of flames 23? [She was so called] because she used to make wicks for the Sanctuary.

In footnote 23 which explains the two footnoted statements in the quotation it writes "Jud. IV,4" for the first statement and "'Lapidoth' means literally 'flames'" for the second statement. So, the Babylonian Talmud translates this phrase as "woman of flames" because "'Lapidoth' means literally 'flames'". Moreover, Deborah "used to make wicks for the Sanctuary". The Babylonian Talmud now renders the Vulgate translation debatable.

Another interesting element in Judges 4:4 is the name of Deborah herself. According to Karla Bohmbach:

When Shakespeare asserted that "a rose by any other name would smell as sweet" (Romeo and Juliet II.ii.43) he was emphatically not expressing an idea that had any warrant in the biblical world -or anywhere else in the ancient Near East. In the ancient world generally, a name was not merely a convenient collocation of sounds by which a person, place, or thing could be identified; rather, a name expressed something of the very essence of that which was being named. Hence, to know the name was to know something of the fundamental traits, nature, or destiny of that to which the name belonged (2000:944).

Deborah is a Hebrew word meaning "a bee" (BDB). According to the Eerdmans Bible Dictionary: "Bees are known for their propensity to get angry and sting when stirred up. The bee is a symbol of pursuit of Israel by the Amorites (Deut. 1:44), of the psalmist by his enemies (Ps. 118:12), and of God's people by God (Isa. 7:18)". If Deborah, that is the bee, is associated with pursuit in a war situation and láppïd is associated with conquering power and flashes and darting chariots, it is not unreasonable to associate Deborah with lightning or flames rather than wife.

Taking the above associations and other factors that were mentioned into consideration, it makes more sense to translate ëshet lappïd6th with "woman of lightnings or woman of flames" than "wife of Lappidoth". This sentiment is concurred by Carol Myers saying:

The need to have a woman identified in relation to a man, rather than the acknowledgement that a woman's identity could in some instances stand alone, apparently influenced virtually all modern and ancient translations. Yet the several roles Deborah plays as an autonomous woman in national life would warrant her name appearing with the epithet "fiery woman" and without reference to a man (2000:331).

As Myers indicates, in Judges 4:4 the real issue is not Deborah's familial relations and the baggage that they carry but the status of Deborah as a warrior. However, the Vulgate translation misdirects the focus. An alternative reading advocated by this article is that Deborah is a woman, a prophetess, a judge, a fiery woman. To bring this discussion to a close, let us now make concluding remarks.

Conclusion

To provide a meaningful introduction to the concluding remarks to be made, remarks by Schroeder are in order. Schroeder posits that during the fourth and early fifth centuries there was a trend towards "domestication", especially among the Christian writings. Deborah was portrayed as mother or wife, she continues. Women were told to emulate Deborah by men, she asserts. That meant women should exhibit conventional feminine virtues like "modesty, obedience, frugality and confinement to the domestic sphere (2014:5). These remarks are important in the sense that the history of interpretation is very much important in making sense of a written piece of work. This background makes Schroeder's other remarks intelligible. Earlier, she charged that the story of Deborah has a disruptive potential. An account of a female judge, prophet and war-leader frequently disturbed traditional cultural assumptions and expectations about women's roles through the centuries, both in the Bible and the world of the interpreter. She then quotes an Israeli historian, Tal Ilan saying, "anomalous women have been treated as textual mistakes which need to be eliminated or manipulated or interpreted so as to fit into the reader's limited concept of what women could and did achieve in history". Lastly, she remembers Mieke Bal who referred to sentiments which downplayed Deborah's role in the war between the Israelites and the Canaanites saying, "'Deborah poses a problem' especially in 'her capacity as a military leader'" (2014:3).

These remarks reinforce this article's hypothesis that, the Vulgate translation "corrects" a perverse characterisation of the woman Deborah. On the other hand, this article rises to the occasion that Rev. Finca decried the absence of alternatives in the face of exclusion of women in the Church's processes. It therefore enlists itself to the alternative reading of Judges 4:4 as "And Deborah, a prophetess, the woman of lightnings/ flames, judged Israel in this time". In fact, this article does not promote the manipulation of biblical texts to conform to supported ideas. Rather, it is wise to accept that the Bible contains literature that is diverse in ideological thinking. The readers do not have the mandate to reorientate the biblical message. Instead, readers need to accept that the Bible represents different theological representations. Their role as readers is to make conscious and responsible choices. They also have a responsibility to account for ethical responsibility to the communities they serve. Judges 4:4 presents a woman who is totally unhooked from the tentacles of patriarchy. It's either a reader associates him/herself or distances him/self from the text, depending on whether the reader is for or against gender equality. Whatever choice, the reader has also to take ethical responsibility for his or her choice. This is a response to Rev. Finca's question: "how many of us are working seriously at finding alternatives and revising the liturgy itself to be more gender sensitive". From the biblical side, this is the little contribution the author makes in finding alternatives and revising Bible reading itself, in order to be more gender sensitive. Finally, in the introduction we promised to answer two questions. The first one is, did the Bible really fail Rev. Finca or the interpretations he received failed him? He was failed by the translations. Secondly, is Judges 4:4 part of "the old Israel" as he describes as "male-dominated, gender-insensitive, perpetuating the stereotypes of the subordination of women"? No, Judges 4:4 deviates from that which is understood to be orthodox or normal.

Bibliography

Bohmbach, Karla G. 2000. "Names and Naming". In Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. (Eds. DN Freedman, AC Myers, & AB Beck). 944.

Bonechi, Sarah. 2008. How They Make Me Suffer... A Short Biography of Galileo Galilei. Florence: Institute and Museum of the History of Science. 88. [ Links ]

Bongela, K.Sakhiwo. 2001. Isihlonipho among amaXhosa.Doctoral dissertation, University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Brown, Dennis. 2003. Jerome and the Vulgate. In A History of Biblical Interpretation, 1:355-379. [ Links ]

Coetzee, Carli. 2001. "They Never Wept, the Men of my Race": AntjieKrog's Country of my Skull and the White South African Signature. In Journal of Southern African Studies, 27(4):685-696, DOI: 10.1080/03057070120090682 [ Links ]

Cundall, AE & Morris, L. 1968. Judges and Ruth an Introduction and Commentary Vol. 7. Leicester: InterVarsity Press. [ Links ]

Delitizsch, F. and Keil S. F. 1973. Commentary on the Old Testament in Ten Volumes. Vol 2. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Finca, Bongani Blessing. 1994. The Decade: A Man's View. In The Ecumenical Review 46(2):191-193. [ Links ]

Gorospe, Athena E & Ringma, Charles R. 2016. Judges: A Pastoral and Contextual Commentary. Carlisle: Langham Partnership. [ Links ]

Holladay, Whitaker L & Köhler, Ludwig. 2000. A Concise Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament. In Logos Bible Software 8. [ Links ]

Kroeze, Jan H. 1994. A Three-Dimensional Approach to the Gender/Sex of Nouns in Biblical Hebrew. In Literator 15(3):139-153. [ Links ]

Lamber, Julia C. 1973. A Married Woman's Surname: Is Custom Law. In Wash. ULQ. 779-819. [ Links ]

Louw, Johannes P & Nida, Eugene A. 1996. Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament: Based on Semantic Domains, Second Edition, Volume One. New York: United Bible Societies. [ Links ]

Makhubedu, Matsatsi G. 2009. The Significance of Traditional Names among the Northern Sotho Speaking People Residing within the Greater Baphalaborwa Municipality in the Limpopo Province. Masters thesis, University of Limpopo. [ Links ]

Mbatha, Busi. 1995. Decade of Solidarity. In Agenda, 11(25):51-54. [ Links ]

McLay, Tim. 2000. Septuagint. In Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. DN Freedman, AC Myers & AB Beck (eds.). 1185.

Niditch, Susan. 2008. Judges. Commentary. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Pierce, Ronald W. 2018. Deborah: Troublesome Woman or Woman of Valor? In Priscilla Papers, 32(2):3. [ Links ]

Ringe, Sharon H. 1998. Women's Bible Commentary. Newsom, CA and Ringe, SH. (eds.). Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. 1-9.

Rudavsky, Tamar M. 2001. Galileo and Spinoza: Heroes, Heretics, and Hermeneutics. In Journal of the History of Ideas 62(4):611-631. [ Links ]

Schroeder, Joy A. 2014. Deborah's Daughters: Gender Politics and Biblical Interpretation. Oxford New York: University Press. [ Links ]

Skidmore-Hess, Daniel & Skidmore-Hess, Cathy. 2012. Dousing the Fiery Woman: The Diminishing of the Prophetess Deborah. In Shofar 31(1):1-17. [ Links ]

Soggin, John A. 1987. Judges: A Commentary. Second Edition. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

The Encyclopedia of World Problems and Human Potential. 1994. Union of International Associations: Brussels. [Online]. Available: http://encyclopedia.uia.org/en/problem/143930. [Accessed: 02/12/2020].

Whitaker, Richard et al. 1906. The Abridged Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew-English Lexicon of the Old Testament by Francis Brown, SR Driver and Charles Briggs, based on the lexicon of Wilhelm Gesenius. In Logos Bible Software 8. [ Links ]

Zungu, E Bonisiwe and Maphini, Nomvula. 2020. Out with Old, in with the New: Negotiating Identity in Re-Naming a Xhosa Umtshakazi. In LALIGENS: An International Journal of Language, Literature and Gender Studies 9(1):66-76. [ Links ]

1 I am not sure which book is Paul 3:1-7. However, I guess it might be reference to texts like 1 Peter 2:13 - 3:1-7, for example.

2 This article's assumption is that the Xhosa reading also represents other Bantu language speakers in South Africa and maybe some parts of Africa.

3 According to Dennis Brown, the Vulgate was completed early in 406 AD (2003:362). However, the version used in this article is Anon (1969).

4 The Septuagint "texts are believed to have been produced from the 3rd to the 2nd or 1st centuries b.c.e" (McLay 2000: 1185). The version used here, however, is Anon (1996).

5 From now on, when I refer to the person I will use Lappidoth and when referring to the word as in the text läppidöth.