Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2413-9467

versão impressa ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.6 no.2 Stellenbosch 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2020.v6n2.a17

ARTICLES

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2020.v6n2.a17

The lion-king in Nahum 2:11-13 [Hebrew 2:12-14]

Fanie (S.D.) Snyman

University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. snymansd@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This contribution investigates the lion metaphor in Nahum 2:11-14 [Hebrew 2:12-14]. Informed by the general theoretical considerations on the working of metaphors, two questions are asked in this contribution: The first question put to the text is to ask whether the portrayal oflion behaviour in the text is correct. The investigation revealed that the description of lion behaviour in the text of Nahum 2:11-13 [Hebrew 2:12-14] differs from what is known about lions. The answer to the first question prompted a second question. The second question is to ask whether the king is portrayed as a lion or is it perhaps the other way around: is the lion seen as a king? Finally, the implications this interpretation will have in understanding this passage will be discussed.

Keywords: metaphor; lion imagery; Nahum

1. Introduction

The film The Lion-King was released on 19th July 2019 as a remake of the original 1994 movie and tells the story of a lion family somewhere in Africa that had to face obstacles of all sorts but in the end prevailed. The story is all about the lion-king Mufasa and his queen, Sarabi with their son, Simba. Scar, the younger brother of Mufasa is the villain who wants to be king, lures Simba into exploring a forbidden elephant graveyard. Mufasa dies but manages to save his son, Simba, the future lion-king. Scar is eventually killed by hyenas and so, in the end, Simba became the new king with Nala the lioness, as his queen.

Lions do not only feature in animated films; they are also mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. In the book of Judges, it is Samson's encounter with a lion that comes to mind (Judges 14) and in the book of Daniel, the story of Daniel in the den of lions (Daniel 6) is one of the most well-known stories in the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible. According to David's own testimony he also killed lions when they threatened the safety of his father's flock of sheep (I Sam 17:34-36). Lesser known but worth mentioning is the story of David's mighty men where one of them by the name of Benaiah is said to have killed a lion (II Sam 23:20; I Chr 11:22). The only human beings in the Hebrew Bible who killed a lion were Samson, David and Benaiah. In I Kings 13 the story is related about a man of God who was killed by a lion (I Kings 13:24-27). A similar incident is reported in I Kings 20:35-36 where a prophet was killed by a lion because of his disobedience. According to II Kings 17:24-26, the new inhabitants of Samaria were killed by lions sent by the Lord because they did not worship him.

It is especially the metaphor of a foreign king portrayed as a lion that is found in the Hebrew Bible. In Ezekiel 32:2 the Egyptian pharaoh is likened to a lion among the nations and in Jeremiah 50:17 the king of Assyria and the king of Babylon are compared to lions that devoured and crushed Israel. Isaiah 5:29 compares the Assyrians to lions that roar and "growl as they seize their prey and carry it off with no one to rescue" (NIV). In Zechariah 11:3 the listeners to the prophecy are admonished to listen to the roar of the lions. The context of the verse makes it clear that it is foreign ruler(s) who are meant by the roaring lions. In Nahum 2:11-14 [Hebrew 2:12-14], lion imagery is used to describe the eventual fate of the Assyrian king.

2. Methodological considerations and the problem investigated

In Nahum 2:11-13 [Hebrew 2:12-14] the readers of the text are confronted with a lion-king. The aim of this article is to explore the metaphorical relationship between the figure of the king and a lion in Nahum 2:11-13 [Hebrew 2:12-14]. Wessels (2014:715) in this regard remarked that the lion metaphor is of great value for the exposition and determination of the meaning of this particular pericope. The literary device of metaphor is an interesting field of study. A basic point of departure is to recognize that there are two elements at work in a metaphor: the tenor or meaning of a metaphor and the vehicle or the figure of a metaphor. Meaning is produced by the interaction between these two elements of a metaphor. For the purpose of this investigation, it is important to note that the secondary subject of the metaphor is also affected by its relationship to primary subject (Strawn 2005:8). For example, in the well-known metaphor 'The Lord is my shepherd,' the Lord is not only likened to a shepherd, a shepherd is also likened to the Lord. In other words, part of the secondary subject is transferred to the primary subject. In this sense, the secondary subject of the metaphor is also affected by its relationship to the primary subject (Strawn 2005:8). In other words, metaphors work simultaneously with similarities and dissimilarities. To get back to the example: The Lord is a shepherd, but the Lord is not only a shepherd. Likewise, a shepherd is likened to the Lord, but a shepherd is not the Lord. Informed by the general theoretical considerations on the working of metaphors, two questions are asked in this contribution: The first question put to the text is to ask whether the portrayal of lion behaviour in the text is correct. The answer to the first question prompted a second question. The second question is to ask whether the king is portrayed as a lion or is it perhaps the other way around: is the lion seen as a king? Finally, the implications this interpretation will have in understanding this passage will be discussed.

3. Nahum 2:11-13 [Hebrew 2:12-14] in the book of Nahum

The book of Nahum is known for its literary qualities. Spronk (1997:6) remarks: "On at least one point all scholars who have studied the book of Nahum agree: the author was a gifted poet." He goes on to quote Jerome who remarked that the Hebrew text of Nahum 3:1-4 is so beautiful that no translation can match it (Spronk 1997:6). Han (2011:9) refers to Nahum as "the poet laureate" of the so-called Minor Prophets. McConville (2002:208) speaks of the "artistic literary qualities of the text" and "its effective use of poetry and metaphor." Zenger (2008:559) noted the powerful poetic images used in the book. Tuell (2016:11) echoes this conviction when he says that from a poetical point of view, Nahum is nothing else but a masterpiece -even in an English translation its vivid imagery and striking use of language and rhythm come through.

The book of Nahum consists of only three relatively brief chapters and can be divided into the following parts:

1:1 The superscription to the book

1:2-8 A semi-acrostic poem cum psalm

1:9-2:2 God is both judge and Saviour

2:3-13 Nineveh's demise

3:1-19 Prophecies announcing doom upon the Assyrian empire, the city of Nineveh and the king of Assyria.

When narrowing the focus down to Nahum 2, Nahum 2:3-13 can be divided in the following segments: In Nahum 2:3-10 a vivid description is given of a vision Nahum saw. An oncoming army is described with the aim of installing fear in the Assyrian army. To the people of God, the army that will destroy the Assyrian army will be instrumental in their own eventual liberation. It is interesting to note that Nineveh is mentioned for the first time only in verse 9. In verse 10 the outcome of the upcoming siege of Nineveh is described: The city "is pillaged, plundered, stripped. Hearts melt, knees give way, bodies tremble, every face grows pale" (NIV).

This is followed by Nahum 2:11-13 [Hebrew 2:12-14] where the metaphor of lions is introduced to illustrate once more that Assyria awaits total destruction. In contrast to a wealth of images and literary devices used in Nahum 2:3-10 [Hebrew 2:3-11], there is now only one image used (Jeremias 2019:147). Nahum 2:11-13 [Hebrew 2:12-14] is then found in the second last part of the book and concluding the prophesy on the demise of Nineveh as the capital of the Assyrian Empire. Nahum 2:11-13 [Hebrew 2:12-14] forms the conclusion to a prophetic oracle that started in 2:3. Nahum 3:1 starts off with theהוי (hoj) particle - a clear indication of the beginning of a new unit in the book.

4. The text of Nahum 2:11-13 [Hebrew 2:12-14]

The Hebrew text of Nahum 2:11-13 [Hebrew 2:12-14]

פָארוּר׃בּוּקָה וּמְבוּקָה וּמְבֻלָּקָה וְלֵב נָמֵס וּפִק בִּרְכַּיִם וְחַלְחָלָה בְּכָל־מָתְנַיִם וּפְנֵי כֻלָּם קִבְּצוּ

12 וְאֵין מַחֲרִיד׃אַיֵּה מְעוֹן אֲרָיוֹת וּמִרְעֶה הוּא לַכְּפִרִים אֲשֶׁר הָלַךְ אַרְיֵה לָבִיא שָׁם גּוּר אַרְיֵה

13 אַרְיֵה טֹרֵף בְּדֵי גֹרוֹתָיו וּמְחַנֵּק לְלִבְאֹתָיו וַיְמַלֵּא־טֶרֶף חֹרָיו וּמְעֹנֹתָיו טְרֵפָה׃

14 וְהִכְרַתִּי מֵאֶרֶץ טַרְפֵּךְ וְלאֹ־יִשָּׁמַע עוֹד קוֹל מַלְאָכֵכֵה׃1הִנְנִי אֵלַיִךְ נְאֻם יהוה צְבָאוֹת וְהִבְעַרְתִּי בֶעָשָׁן רִכְבָּהּ וּכְפִירַיִךְ תֹּאכַל חָרֶב

It is a good practice to consult more than one translation and therefore the Revised Standard Version and the New International Version are given here.

The RSV-translation of the text

11 Where is the lions' den,

the cave of the young lions,

where the lion brought his prey,

where his cubs were, with none to disturb?

12 The lion tore enough for his whelps

and strangled prey for his lionesses;

he filled his caves with prey

and his dens with torn flesh.

13 Behold, I am against you, says the Lord of hosts, and I will burn your chariots in smoke, and the sword shall devour your young lions; I will cut off your prey from the earth, and the voice of your messengers shall no more be heard. 2

The NIV-translation of the text

Where now is the lions' den,

the place where they fed their young,

where the lion and lioness went,

and the cubs, with nothing to fear?

12 The lion killed enough for his cubs

and strangled the prey for his mate,

filling his lairs with the kill

and his dens with the prey.

13 "I am against you,"

declares the Lord Almighty.

"I will burn up your chariots in smoke,

and the sword will devour your young lions.

I will leave you no prey on the earth.

The voices of your messengers

will no longer be heard." 3

The variety of terms used to describe lions is noteworthy. No less than four different terms are used to describe lions: male lions (אריה), a lioness (לביא), young lions (כפר) and the lion cubs (גור). Verse 13 starts with "look" or "behold" (הננו) as translated by the RSV but ignored by the NIV, indicating a turn in the point the prophet wishes to make. That verse 13 indeed marks a turning point becomes clear in the use of the well-known formula "says/ declares the Lord Almighty" (נאם יהוה צבאות) used for the first time in this pericope (Cf. also Nahum 3:5). Verse 13 revealed that the lions mentioned in verses 11 and 12 are meant to be understood as the royal family of the Assyrian empire. While the royal family had according to verses 11-12 more than enough to eat feasting on the prey (טרף) the male lion brought to their den, there will now be no prey (טרף) on earth left to them (Cf. verse 13). Total defeat awaits them as their chariots will be burnt and there will be no future for the dynasty as the future kings (the young lions) will be devoured by the sword. The vocabulary used in verse 13 creates a clear metaphorical relationship between the image of the lions mentioned in verses 11-12 and the royal family indicated in verse 13.

5. The historical background of the book of Nahum

The time of Nahum's prophecies can be dated to the reign of the Assyrian empire. Although the kingdom of Judah managed to keep its independence, it became for all practical purposes an Assyrian administered territory. The Assyrian empire exercised a terrifying presence in the ancient Near East (Timmer 2012:80). It was during Ashurbanipal's rule that he had to act against Tanutamun of Egypt. He did so decisively when he marched up the River Nile as far as No Amon (Thebes) where he invaded the city and effectively destroyed it in 663BC. Nahum refers to this incident in his prophecy in 3:8. Since the Nahum text refers to this incident, it is assumed that the book originated after 663BC. During the later years of the reign of Ashurbanipal he was faced with increased pressure and even outright rebellion from the Babylonians, Egypt, and various Indo-Aryan peoples. It was especially the threat coming from his brother in Babylon who was appointed king of Babylon by their father. All of these skirmishes left the once mighty Assyrian empire weakened. After his death he was succeeded by two of his sons and it was during the reign of his second son, Sin-shar-ishkun (629-612BC), that the Assyrian empire collapsed under the onslaught of Nabopolasser the founder of the Neo-Babylonian empire with the help of the Medes under the command of Cyaxares. The book of Nahum can thus be dated after 663BC but before the final collapse of the Assyrian empire in 612BC. To try to arrive at a closer date become speculative. Did Nahum utter his prophecies at the height of Ashurbanipal's reign or during the reign of his second son when the empire was on the decline? Both options are possible making it difficult to come to a more precise dating of this book.

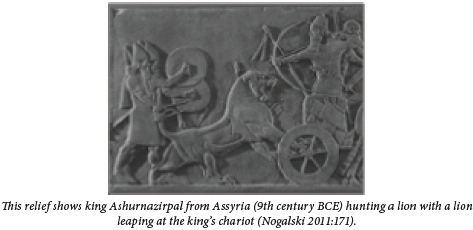

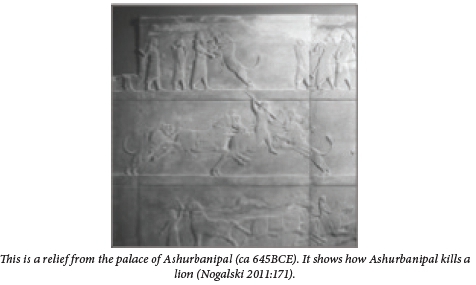

6. The king is a lion

Kings are often related to lions. Roberts (1991:67) remarks in this regard that the lion is a traditional symbol for kingship throughout the Near East. Jeremias (2019:148) stated that when a lion is used as a symbol to express the power of a human being, the lion symbol was reserved only for the king. The king's irresistible power is depicted as a lion that overpowers a human (Strawn 2005:84). Because of the ferocity of a lion, the monarch or mighty one became the lion (Strawn 2005:153). It is especially true of the kings of Nineveh where they compare themselves with the typical characteristics associated with lions. Both Adadnirari II and Ashurnasirpal declared: "I am lion-brave" and Sennacherib said: "Like a lion I raged" (Robertson 1990:95). Of Sargon II (722-706BC) and Asarhaddon (681-668BC) it is said that they became angry 'like a lion' at the beginning of a campaign and it is little wonder then that the enemy is often described as a lion (Prinsloo 1999:344). According to Dietrich (2016:67), "Assyrian kings loved to depict themselves hunting lions; they had a penchant for having themselves portrayed undertaking this royal activity." It is done to symbolize the extraordinary daring of the monarch and his ability to wrestle successfully with dangerous opponents (Dietrich 2016:67). Not only do we have reliefs picturing a king hunting lions, kings are also seen as lions. Assyrian kings were seen as lions and their politics as lions hunting for prey (Berlejung 2006:334).

It is attested in reliefs that the king in the ancient Near East is often related to a lion.

Assyrian kings often presented themselves in terms that resembles the behaviour of lions. Lions are predators and as such were seen as mighty, brave, fierce and aggressive amounting to an ideal symbol of an enemy (Strawn 2005:134). In Proverbs 30:30, a lion is described as "mighty among beasts, who retreats before nothing" (NIV). Lions were the embodiment of the power and dominion of especially Assyrian kings (Jeremias 2019:148). Ishtar, the Assyrian goddess, was often represented as a lioness or as mounted on a lion's back (Baily 1999).

7. The king is not a lion

After a lengthy description of the siege and fall of Nineveh, this part of the book of Nahum comes to an end with a final word of doom making use of the imagery of a pride of ferocious lions (Robertson 1990:95). In Nahum 2:11-13 [Hebrew 2:12-14], lions are seen as predators that have a den where the cubs or younger lions stay with the adult (presumably male) lions, who bring the prey they caught to the den. The text also informs the reader that the male lion catches enough to feed both the young ones, and even for the lioness that is waiting in the den for the male lion to return to with prey. Having a den implies safety and security for both the male lion as well as the lioness and the cubs. Lastly, it is said that male lions fill their caves with the prey they killed so that there will be ample provision for food for the lion family.

The image of a lion is used to create a metaphorical relationship with an actual king, in this case the Assyrian king. The key to the metaphorical relationship between a male lion and the Assyrian king is given in the last verse of the passage. The chariots of the king will be burnt and his children (referred to as young lions) will be devoured by the sword. With this saying the image of the king as a lion and the reality of the king in real life becomes blurred. Image and reality become one. The provision of food (prey according to the image of the lion) will be put to a stop. The message of the metaphor is clear: the lions' den is nothing else but the palace of the king. The young who stay at the den (palace) refer to the children of the king and the lioness is the queen, the wife of the king. The king cares for his family by providing food and the safety of a palace as the male lion cares for his off-spring and female lion in the den. The (Assyrian) king acts as a mighty male lion acts in the wild.

This is the line of thought followed in some commentaries. Nogalski (2011:171) for instance says "... the den is the place where the lion goes for safety." In a few sentences further on he commented that the purpose the den served is to be "the home where the lion took its prey" (Nogalski 2011:171). Robertson (1990:96) is of the opinion that "even a ferocious beast like a lion treasures its moments of calm and safety. It too likes to relax in its den, to stride about oblivious to dangers." Roberts (1991:67) sees the lion in this metaphor as a creature who preys for his den. Baily (1999) is of the opinion that the ferocity of the lion filled his lair with food for the lioness and the cubs. He continues: "Thus the image here is one of brutality." It is highly unlikely that a lion will kill prey "by placing both paws on their victim's throat" as Longman (1993:810) claims. Wessels (2014:712) says: "We can learn a great deal about lions and the lion family by simply analysing what is at hand in verses 12 and 13."

What the lion does in Nahum 2:12-14 [Hebrew 2:12-14] however, is not typical lion behaviour. First of all, lions do not have a den. Lions roam around a marked territory of several square kilometres constantly in search of prey. There are other predators like hyenas and wild dogs who do have temporary dens where they hide their young ones and in the case of wild dogs they will bring food to the den by vomiting the meat of a freshly caught animal so that the puppies may feed from the meat vomited by the mother.

Secondly, lions do not feed their young ones in a den. Lionesses will stow their cubs away after they have been born, from the rest of the pride, and will then introduce the cubs to the rest of the pride at an appropriate time. From a very early age cubs join in the feasting on a carcass after the adult and especially the male lion or lions have had their share of the meat. Because lions do not have dens, they do not store up prey in the dens.

Male lions do not kill prey for the lionesses and the cubs. In a report on lion behaviour it was found lionesses do the hunting in 80-85% of the hunts. Male lions will trail behind and once an animal is killed, they will move in and snatch the "lion's share" (Estes, 1997:372-373). According to an article published recently in National Geographic4a lion pride is all females all the time. Lionesses are responsible for catching the vast majority of food and they are in actual fact the heart and soul of the pride. Male lions come and go.

Since lions do not have dens, they do not fill their caves with prey. Lions, after they have killed an animal, will devour the animal right at the spot where it was killed. In the case of a smaller antelope like an impala and depending on how many lions are part of the pride, the animal will be devoured in total in less than ten minutes. Were they fortunate enough to bring down a bigger animal like a buffalo or a giraffe, they will feast for several days on the carcass until they have had enough and then simply leave the carcass to other carnivores like hyenas, jackals, and vultures to finish off the carcass5.

It is clear that there is a major discrepancy between what is said of lion behaviour in the text of Nahum and what the facts are about lion behaviour as was observed by game rangers as well as scientists.

8. The lion is the king

If the behaviour of the lion described in Nahum does not match with what we know of typical lion behaviour. What then should we make of the metaphor where the king is compared to a lion? Or, to put it in other words: what would the implications be of the results of the investigation? What Nahum did was not to present us with an accurate description of lion behaviour. The point he wants to make was that the lion in the metaphor is the king. What the lion does, is what the king does or ought to do and therefore the lion is the king. The metaphor does not intend to convey knowledge of lion behaviour and apply it to the king. The metaphor works rather the other way around. In terms of metaphor theory, the secondary subject is transferred to the primary subject. The image of a lion is used to convey knowledge of the king. The king (and not the lion) is the one who feeds the young (verse 12). It is the king (and not the lion) who has the responsibility to provide for his family (verse 13). It is the king (and not the lion) who has to fill his palace with wealth and riches to secure the wellbeing of the queen and their children. All this is done by making use of the figure of the mighty lion. Lions were conceived of as a threat, dangerous and aggressive (Strawn 2005:134) and this was Judah's experience of Assyrian rule. The comparison between the Assyrian king and a lion remains an extremely apt comparison to underline the strength and power of the Assyrian empire.

The reversal of the metaphor serves another about turn of events. The lion as hunter will become the hunted. Up to verse 13 there was only mention of the chariots of the enemy. In this last verse the war chariots of the king are mentioned that will go up in smoke. While the chariots of an invading army flash and storm through the streets of Nineveh (2:3-4), the Assyrian chariots will be burnt and will go up in smoke (verse 13). Instead of the young lions feasting of prey (verses 11-12) they will be devoured by sword. The king who is supposed to provide food for his sons and daughters will no longer be in a position to do so anymore. Likewise, the palace will no longer be a safe place for the king, the queen and their children (verse 11). The variety of words used for lion is an indication of the total collapse of the Assyrian Empire in the sense that neither the king nor the queen or their children will survive the final downfall (Jeremias 2019:149). All this will happen not because the military power of Judah, it will happen because "I am against you, declares the Lord Almighty" (verse 13). The last verse of the chapter forms the climax of the entire pericope. Jeremias (2019:150) remarks in this regard: ". der Vers besliesst stattdessen eine vorausgehen-de literarische Grosseinheit mit der Funktion, rüchblickend ein zuvor ausführlich geschilderten Geschehen von einem Wort Gottes her zu deuten."

Conclusion

Unlike the story told in the Lion King film, the lion-king in the book of Nahum does not prevail. In the Lion King film, the story has a good ending. After the death of a king, his son became king, married and "lived happily ever-after." In the book of Nahum, the lion-king does not have a future as his off-spring will be devoured by sword and he will be left with no prey. Strange as it may seem, the bad news for the lion-king of Assyria is good news for Judah. The tyranny of the Assyrian Empire will come to an end. It will happen even if the king can for now be compared to a lion. The surprising element in this metaphor is that it turns out that the lion is in actual fact compared to the king. The king unlike lions in real life will not be victorious but will suffer defeat and humiliation. The metaphor worked the other way around this time. Although it seems to be the case, the image of a lion does not function as the source domain for the metaphor. It worked rather the other way around: attributes of the king were projected unto the lion and by doing that the king became the source domain of the metaphor so that the lion acted like the king. Instead of being fearful for a mighty lion-king the people of God can look forward to the downfall of a king. This will happen through the action the Lord will take.

Bibliography

Barker, K.L. & W. Baily 1999. Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, New American Commentary Vol 20 (Nashville: Broadman & Holman).

Berlejung, A. 2006. „Erinnerungen an Assyrien in Nahum 2,4-3,19," in Lux, R & Waschke, E-J (eds), Die unwiderstehliche Wahrheit: Studien zur Alttestamentlichen Proohetie: Festschrift für Arndt Meinhold. Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt (Arbeiten zur Bibel und ihrer Geschichte 23), 323-356.

Coggins, R.J. and J.H. Han (2011), Six Minor Prophets through the Centuries: Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi, Blackwell Bible Commentaries (Malden, MA: Wiley- Blackwell).

Dietrich, W. 2016. Nahum Habakkuk Zephaniah. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. (International Exegetical Commentary on the Old Testament). [ Links ]

Estes, R.D. 1997. The Behaviour Guide to African Mammals. Halfway House: Russel Friedman Books CC. [ Links ]

Jeremias, J. 2019. Nahum. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. (Biblischer Kommentar Altes Testament Band XIV/5,1). [ Links ]

Longman, T. 1993. "Nahum," in McComiskey, T E (ed). The Minor Prophets - An Exegetical and Expository Commentary (Vol 2). Grand Rapids: Baker Books. [ Links ]

McConville, J 2002. Exploring the Old Testament: A Guide to the Prophets. Downers Grove Ill:Inter-Varsity Press. Nationalgeographic.com/animals/2019/07/lion-pride-family-dynamics-females. [ Links ]

Nogalski, J.D. 2011. The Book of the Twelve: Micah-Malachi, SHBC (Macon, G.A.: Smyth & Helwys).

Prinsloo, G.T.M. 1999. 'Lions and vines: The imagery of Ezekiel 19 in the light of Ancient Near-Eastern descriptions and depictions.' Old Testament Essays 12(2), 339-359. [ Links ]

Roberts, J.J.M. 1991. Nahum, Habakkuk and Zephaniah. A Commentary. Louisville: Westminster/John Knox. (Old Testament Library). [ Links ]

Robertson, O.P. 1990. The Books of Nahum, Habakkuk and Zephaniah. Grand Rapids: Wm B. Eerdmans. (New International Commentary on the Old Testament). [ Links ]

Spronk, K. 1997. Nahum. Kampen: Kok Pharos. (Historical Commentary on the Old Testament). [ Links ]

Strawn, B.A. 2005. What is stronger than a lion? Leonine Image and Metaphor in the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. (Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 212). [ Links ]

Timmer, D. 2012, "Nahum, Prophet of God Who Avenges Injustice," in H.G.L. Peels and S. D. Snyman (eds.), The Lion Has Roared: Theological Themes in the Prophetic Literature of the Old Testament. Eugene: Pickwick, pp. 79-86. [ Links ]

Tuell, S 2016. Reading Nahum - Malachi. A Literary and Theological Commentary. Macon: Smyth & Helwys. [ Links ]

Wessels, Wilhelm J. 2014. "Subversion of Power: Exploring the Lion metaphor in Nahum 2:12-14." Old Testament Essays 27(2), 703-721. [ Links ]

Zenger, E. (ed.) (2008), Einleitung in das Alte Testament, Kohlhammer Studienbücher Theologie 1.1. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. [ Links ]

2 Na 2:11-13; The Revised Standard Version. (1971).

3 Na 2:11-13; The Holy Bible: New International Version. (1984).

4 nationalgeographic.com/animals/2019/07/lion-pride-family-dynamics-females

5 This information is based upon a personal interview I had with Mr Hannes Kruger, manager at the Madikwe Hills Game Lodge in the Madikwe Game Reserve, Northwest Province, South Africa during July 2019.