Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2413-9467

versão impressa ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.6 no.2 Stellenbosch 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2020.v6n2.a14

ARTICLES

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2020.v6n2.a14

Towards the aesthetics of self-termination (suicide). The spiritual interlude between death (shadow) and life (light)

Daniël Louw

University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa. djl@sun.ac.za

ABSTRACT

To end one's life (suicide) creates a lot of questions concerning the identity and eventual emotional and spiritual condition of the person. Within a more religious context, the intriguing question surfaces: When a committed believer commits suicide, will such a person still go to heaven? The ethical dilemma evolves around questions regarding right (good/liberation) and wrong (evil/damnation), heaven or hell. Instead of a moral approach, the article opts for an aesthetic approach within the framework of a tragic hermeneutics of self-termination. Instead of applying the notions of "suicide" or "self-killing," the concept of self-termination is proposed. A theology of dereliction is designed to explain the basic assumption: In a Christian spiritual assessment of "suicide," the question is not about the how of death and dying but on the being quality of the sufferer. In his forsakenness, the suffocating Christ reframed the ugliness of death into the beauty of dying and termination: Resurrection hope! Several portraits are described from the viewpoint of literature, philosophical and poetic reflections regarding the complexity of the phenomenon of self-termination and its connection to the existential disposition of dreadful anguish; i.e., the ontic and tragic disposition of apathetic unhope (inespoir)1.

Keywords: Self-termination; suicide; a theology of forsakenness; Soly Sombra; pastoral hermeneutics of apathetic self-termination; unhope (inespoir)

Introduction: A dream became true - HospiVision

Andre De La Porte (my friend, doctoral student and co-researcher in the struggle to establish pastoral care as "soul care") is dead. For nearly 20 years we have served together on the board for hospital care: HospiVision. His life dream to establish pastoral caregiving as a professional service within a hospital setting, became a reality with the establishment of hospital and spiritual care as a professional service working together with other professions in the realm of healing, helping, and human well-being.

In a nutshell: "Hospivision is a compassionate friend who can comfort and counsel you, your family and caregivers as you undertake your journey through illness" (HospiVision Online 2020). André dedicated his life, all of his spiritual energy, in pursuing and achieving the following pastoral, ministerial, and life goal: "At HospiVision we assist people to regain as much of their humanity and dignity and integrity as possible, despite their health struggles. Illness impacts both on the individual and those around them. That is why we want to help people get their lives back. The cancer, the heart attack, the operation, the trauma becomes a smaller and smaller part of how we think about ourselves and we recover our capacity to focus on the things that are of value to us - family, friends, play, the community, spirituality, artistic expression, work ... to live with HOPE!" (HospiVision Online 2020).

Andre's life commitment and vocation can be summarised by the following phrase: To be "a compassionate friend" who can comfort and counsel suffocating people, people in distress, their family members as they undertake their journey through illness and loss. HospiVision does this by providing spiritual, emotional, social, and physical care to patients in hospital, while at the same time empowering people through skills development. His life and professional career displayed the paracletic dimension of cura animarum: The comfort and support of suffering families and children, people infected or affected by AIDS or any other ailment.

And now André is dead. He decided to terminate his life. Perhaps, I should reframe my remark: His condition of being overwhelmed by powerlessness, dread, and sheer anxiety (an ontic state of apathetic non-hope), terminated his life. The shadow side of life disempowered him, stripped him of dignity. The burden of a lockdown was too dreadful. For him, death has become the liberating peep hole into the "sunshine of eternity."

"Think that dream is turning into nightmare, and when nightmare has reached its most agonising point, you will awake. That will be the experience which today you call death" (Marcel 1965:153).

Searching for sunshine

And it so happened that I received the following personal email (21/06/2020) from his wife Annette: "Andre, you woke up with these words one morning: 'Searching for sunshine'. It became the title of your course on depression that you wrote for HospiVision. The darkness inside you yearned for the light. Your commitment to the pastoral care of the sick was limitless. Isaiah 61 was the trading floor for the currency of your pain. 'Heal the broken hearted, set the captives free.' Yet, you could not escape the captivity or despair of your own broken heart. I had to go out for an errand. I was focused on the debriefing of the nurses in the week ahead. I was speaking on the topic of how we need to shield our souls against all the pain of the pandemic. On my way home, your face flashed before me and I cried out in anguish for what I saw. Oh no God, do not tell me that the sword of Damocles has fallen on us today - the constant threat of death, lurking in the corner. When I arrived home, I found you exactly as I saw you in my flash vision. God has shielded my heart by showing and preparing me beforehand."

His unexpected death challenges his wife, family, friends, and colleagues with the reality of grief and mourning. In the words of R.S. Sullender (1985:96): "In summary, all losses, no matter how distant are eschatological occurrences in the sense that they remind us of the shortness of time. All eschatology involves an element of judgement. Losses are catalysts, forcing us to reflect on the value of life, on the value of what is lost and on ourselves. In all of these ways, the original loss has been a catalyst to spiritual growth via the dynamic of self-judgement." Without any doubt, the loss of a loved one pierces into the very fibre of one's existence and soul (Louw 2008:548-549). In fact, it enters the delicate interplay between attachment and detachment. In this regard, B. Raphael's remark (1984:54) captures the very essence of bereavement as the attempt to cope with both loss and grief as a function of the attachment of the bereaved to that which is lost. "Bereavement will affect the family system in many ways. The death of a member means the system is irrevocably changed. Interlocking roles, relationships, interactions, communications, and psychopathology and needs can no longer be fulfilled in the same way as before death. The family unit as it was before dying, and a new family system must be constituted. The death will be a crisis for the family unit as well as for each individual member and each component subsystem." E.H. Friedman perceives death as the most drastic happening in a family system. Death creates processes which vary from close affiliation to resistance, anger and even forms of hatred. It stirs several questions. In the case of self-termination, loved ones start to wrestle with the question of the deceased and his/her condition in afterlife.

In the case of André, his loved ones were immediately confronted with the puzzle of a suicidal death. But where is André now? What will happen to his soul? To commit suicide, the ethical and spiritual question surfaces: Is the termination of life an act of self-condemnation or humane liberation? The result of a merely "destructive character"? (Martin 2018:1).

In a mode of irony: A destructive character and attempt of redemption?

In his 1931 essay, The Destructive Character, Walter Benjamin sums his life struggle within Hitler Germany up in this way: "The destructive character lives from the feeling not that life is worth living, but that suicide is not worth the trouble" (Martin 2018:2). These were among the last words written by Walter Benjamin, months before his suicide in 1940. "In fact, these words are engraved on his tombstone. Even more oddly, and perhaps profoundly befitting his somewhat scattered career, this German-Jewish atheist who died by suicide was allowed burial in consecrated Catholic soil in Spain" (Martin 2018:2). Walter Benjamin, a very influential philosopher and critic of "Hollywood capitalism," was one of the founding fathers of the so-called Frankfurt School of Philosophy in the 1920s and 1930s, which included Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Erich Fromm, Hannah Arendt, and Herbert Marcuse. "The members were German neo-Marxists and psychoanalytically influenced scholars who were openly critical of the German people who allowed the National Socialists to come into power" (Martin 2018:1).

Residing in a destructive character, suicide is described in terms of an insoluble paradox. "It is the one 'way' out that, by its very inauthenticity, remains inaccessible (Martin 2018:3). In other words, suicide is inauthentic. The redemption sought through suicide is illusory."

The nineteen century philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer formulated the paradox and irony of suicide as follows: "The only cogent argument against suicide is that it is opposed to the achievement of the highest moral goal, in as much as it substitutes for a true redemption of this world of misery a merely apparent one" (in Martin 2018:3). The implication is that even suicide could be interpreted as a constructive act in our human's quest and search for meaning despite its association with the absurd.

Damnation or liberation: The moral and spiritual-religious discourse?

In a brief diocese writing, Father Jason Signalness (2019) poses the religious question: If someone commits suicide will they still go to heaven? "When someone dies as a result of suicide, it is a tragedy that can devastate a family and community. In such times, people often look to the Church for consolation and guidance, and rightly so. When we consider death, judgement, hell, and heaven, though, we must be careful. The truth here is nuanced. 'If someone commits suicide, will they still go to heaven' is a question that does not have, for us here and now, a yes or no answer" (Signalness 2019:1).

Within the Catholic tradition, after death, one enters into a state of purgatory "Wherein our flaws are 'purged' in an unpleasant, but hopeful process that always leads to heaven. In fact, our prayers can hasten the process of purification for these souls. That is why we pray for the dead at every Mass and ask priests to offer Masses for the deceased" (Signalness 2019:1). The point is that suicide resides under the category of a "mortal sin." Due to the Catechism, suicide is sinful because "We are stewards, not owners, of the life God has entrusted to us. It is not ours to dispose of" (Signalness 2019:1). But then the Catechism has an exemption clause: "Grave psychological disturbances, anguish, or grave fear of hardship, suffering, or torture can diminish the responsibility of the one committing suicide. We should not despair of the eternal salvation of persons who have taken their own lives. By ways known to Him alone, God can provide the opportunity for salutary repentance. The Church prays for persons who have taken their own lives" (Signalness 2019:1). According to Signalness: Only God knows the answer.

Matthew Schmalz (2018:1) points out that many of the world's religions have traditionally condemned suicide because, as they believe, human life fundamentally belongs to God. The argument in the Jewish tradition is that suicide is prohibited. The tradition links this prohibition to Genesis 9:5, which says: "And for your lifeblood I will require a reckoning." This means that humans are accountable to God for the choices they make. From this perspective, life belongs to God and is not yours to take.

According to St. Augustine of Hippo, he who kills himself is a homicide. In fact, according the Catechism of St. Pius X, an early 20th-century compendium of Catholic beliefs, someone who died by suicide should be denied Christian burial - a prohibition that is no longer observed (Schmalz 2018:1). The Italian poet Dante Aligheri, in The Inferno, placed those who had committed the sin of suicide on the seventh level of hell, where they exist in the form of trees that painfully bleed when cut or pruned (In Schmalz 2018:1).

In the sixth century AD, suicide became a secular crime and in Christian circles began to be viewed as sinful. In 1533, those who died by suicide while accused of a crime were denied a Christian burial. In 1562, all suicides were punished in this way. In 1693, even attempted suicide became an ecclesiastical crime, which could be punished by excommunication, with civil consequences following. "In the 13th century, Thomas Aquinas denounced suicide as an act against God and as a sin for which one could not repent. Civil and criminal laws were enacted to discourage suicide, and as well as degrading the body rather than permitting a normal burial, property and possessions of the suicides and their families were confiscated" (Wikipedia 2020).

In the Muslim tradition, suicide is totally rejected and falls under the category of condemnation. Therefore, according to traditional Islamic understandings, the fate of those who die by suicide is similarly dreadful. "Hadiths, or sayings, attributed to the Prophet Muhammad warn Muslims against committing suicide. The hadiths say that those who kill themselves suffer hellfire. And in hell, they will continue to inflict pain on themselves, according to the method of their suicide" (Schmalz 2018:1).

In Hinduism, suicide is referred to by the Sanskrit word "atmahatya," literally meaning "soul-murder." "Soul-murder," therefore, prevents the soul in the attempt to reach karma. It is said to produce a string of karmic reactions that prevent the soul from obtaining liberation. "Buddhism also prohibits suicide, or aiding and abetting the act, because such self-harm causes more suffering rather than alleviating it. And most basically, suicide violates a fundamental Buddhist moral precept: to abstain from taking life" (Schmalz 2018:1).

In Christianity, most of the ethical stances are derived from the command in Exodus 20:13: "You shall not murder." Although the text is an exposition on the liberation act of the Exodus 20:2, and points to unlawful acts of deliberate unjustified killing by robbing a human being from parting in this covenantal act of liberation, many theologians argued that suicide is a sin against one's calling to be a steward rather than a destructor of life.

From a more humanistic and social perspective, the argument is that in the decision to take one's life, this responsibility could serve a "common good of self-service." In his classic work On Suicide, French sociologist Emile Durkheim used the term "altruistic suicide" to describe the act of killing oneself in the service of a higher principle or the greater community. "And consciously sacrificing one's life for God, or for other religious ends, has historically been the most prominent form of 'altruistic suicide'" (Schmalz 2018:1). The notion of death as a kind of "common good" or "higher goal" also appears in some religious traditions. For example, the jihad in Islamic fanaticism. Al-Qaeda defines jihad as an "individual duty" incumbent on all Muslims (Devji 2005). In Hinduism there is the tradition of ascetics fasting to death after they gained enlightenment. In political nationalism and patriotism, soldiers are motived to die for their country and fatherland.

My viewpoint

Albeit, a final solution on the mystery of self-termination (suicide) is impossible. To my mind, most of the viewpoints, even ethical stances, are built on mere speculation without substantial credibility. Religious theories on afterlife and God's view on suicide are most of times hypothetical. We do not know the answer on the position of a person who committed suicide. My personal position is qualitative, namely that in terms of a Christian paradigm, God is not interested in how we die but who we are when we die (qualitative stance); i.e. the quality of our position before God and our identity in Christ. Life should not be assessed in terms of quantification but in terms of qualification. Our ontic reality in Christ determines the value of life, not the sum total of our "good works" or "multiple trespasses," even "wrong choices". Grace determine actions and not vice versa.

In fact, there is no real reference in scripture to an ethical assessment on the how of dying. The reference to king Saul who took his life, as well as his armour-bearer (1 Sam. 31:4-5), is not helpful. Saul took his life after he consulted the Witch of Endor and acted in total disobedience. The hanging of Judas in Matthew 27:1-10 took place within the context of the betrayal of Christ. The act in itself is not assessed ethically. The contours for making a spiritual and Christian evaluation, should take another route. The question at stake, is who we are in Christ when we die. According to 2 Corinthians 5:17: "If anyone is in Christ, he/she is a new being." Death cannot destroy our new identity in Christ. This is more or less the argument of Paul in 1 Corinthians 15:54: "Death has been swallowed in victory." The mode or means of dying does not determine our Christian spirituality when we die. The sting of death had been conquered irrespective of the event of our death.

When all forms of death within a Christian paradigm are fundamentally determined by Paul's eschatological verdict on death and dying, the challenge is to revisit the phenomenon of "suicide" in order to find terminology that addresses this critical and fatal intervention in one's life in an appropriate manner. Is it possible to move from a moral assessment to a more spiritual and aesthetic assessment? Can death be rendered as "beautiful"?

In search of terminology: Suicide, self-kill, self-initiated euthanasia or self-termination?

Naming the event of dying, and the contribution of any form of human intervention, are intrinsically part of what one can call a spiritual perspective on human life and wholeness, spiritual well-being. In this respect, the discourse on euthanasia applies.

Euthanasia means a "good" or "soft" death. The option of euthanasia comes into play when death is approaching and existent in terms of a terminal situation, which is irrevocable, and medically speaking, inevitable and unavoidable (Clark 1996). Can one intervene in this regard?

There are various forms of euthanasia. Besides the notion of passive euthanasia (to withdraw or to withhold assistance and medication) (Drane 1994:86), active euthanasia refers to actively initiate a process that will take the patient's life; acting to bring about death by introducing the cause of the death rather than stepping back and letting an already existing legal condition proceed (Louw 2008:516-525). Within the euthanasia debate this is the most difficult one: The direct administration of a death-dealing substance to shorten the life of the dying patient. Some refer to this procedure as physician-executed killing, death with dignity or managed death. Managing death, means keeping control in the sense that death occurs when the patient wishes. It implies not merely pain control, but the control of suffering and psychological distress.

In the search for appropriate terminology, the notion of self-initiated euthanasia, could be considered: Where the patient him/herself takes the initiative to end life. In this regard, one can speak of suicide or self-killing. The question at stake is: Who can decide when this should occur and what about the capacity of the patient to take such a decision? And in most cases, the person who commits suicide, is not necessarily on the brink of dying due to an acute medical and clinical condition classified as "the terminal stage" of death and dying. In many cases of euthanasia, medical or psychiatric reasons are at stake, which is not always the case in general suicide. However, there are so many causative factors or possible triggers that it become very difficult to distinguish between suicide and euthanasia. For the person who commits suicide, the perspective of self-initiated euthanasia could indeed be a proper category: The deep longing and urge for a peaceful death. Its aim is mercy and not malice. But even this term is problematic because the act of ending one's life could for somebody in a state of dreadful anguish neither be "good" (eu) nor bad (malice) because the condition is about a state of sheer nothingness, beyond any definable category. That is the same with the category "voluntary death" because in dread every act and decision could become involuntary.

That is for example the case where, in his book Slot van die dag (2017), the South African author Karel Schoeman revealed his intention to end his life and described in detail the paradigmatic framework for his final decision. He refers to the predicament of being totally on one's own: Solitariness (alleenheid) which is not for him loneliness (eensaamheid) (Schoeman 2017:177). In fact, he repeats that he is full of gratitude and his life is fulfilled (2017:151,153). He describes his decision to end his life as a sober-minded decision, deliberately and responsibly taken, and executed with a sense of responsibility; not in a state of anxiety but in sincere gratitude for the option to end his life (2017:144 (an act of free will - a voluntary, gratuitous death; 2017:125). Schoeman refers to the words of N.P. Van Wyk Louw: Life is beautiful and so death is beautiful as well (Schoeman 2017:121). Dying should, therefore, become reframed within the paradigm of self-determination. It is within this kind of aesthetic reframing of death and dying, as well as its mysterious and unfathomed depths, that the term of self-termination becomes more appropriate in naming the act of ending one's life (suicide).

In pastoral care we need to face the reality that to define death is indeed very complicated. If death is a personal process, embedded in a mystery, then death is more than organ death or brain death. Death is ultimately a spiritual, moral, and aesthetic issue. Nelson et al. (1984) are convinced that somewhere along the line, we have to be willing to say that we are no longer dealing with a human person and that death is more than a biological event. Be that as it may, when is a living human being less human and less personal? However, while struggling to come to terms with the option of self-termination or not, our pastoral challenge is not to end life, but to assist and support suffocating human beings in terms of warmth, and comfort : Life care as hope care (Louw 2016).

Even "self-termination" from a pastoral perspective on comfort, could in specific circumstances be viewed as a "therapeutic" intervention, a form of consolation for both the person struggling with a "death wish" as well as for relatives, families and the social community in their attempt to come to terms with the tragedy of "suicide." In this sense, the act of ending one's life is a mode of comforting; it is in itself "good" (eu-thanasia), an "unctuous soulfulness" and form of "unctuous rectitude"; the "best" or "good" alternative and exit for the acting person exposed to the tempest of suffocation.

Rather than to become entangled in different forms of formulation, and the attempt of identifying language and terminology to articulate the event of ending one's life, an alternative route, is to describe the phenomenon in terms of language used by philosophers and poets in literature. Thus, the following literature approach in what can be called tragic hermeneutics of self-termination because the event in itself is generally speaking about a personal tragedy. In tragic hermeneutics of self-termination, the description is only to a certain extent internal (from the perspective of the sufferer). In the last instance, the description is always "external" and afterwards (a posteriori) because the moment of the act, incidence and event, cannot be described by the self-terminating victim. Reflection and analyses are therefore always backwards and, thus, exposed to misinterpretation and speculation. On the other hand, even this hypothetical backwards analysis, can, despite its relativity, be soothing and therapeutic for the people personally infected/affected by the suicidal act.

Describing the phenomenon of self-termination (personal portraiture); Towards tragic hermeneutics of self-termination.

Tragedy (from the Greek: τραγωδία, tragöidia) is a form of drama based on human suffering that invokes an accompanying catharsis or an inescapable, inevitable kind of irreparable loss. Aristotle linked tragedy with the tragic hero>s hamartia, which is often translated as either a character flaw, or as a mistake (since the original Greek etymology traces back to hamartanein, a sporting term that refers to an archer or spear-thrower missing his/her target). According to Aristotle, «The misfortune is brought about not by [general] vice or depravity, but by some [particular] error or frailty. The reversal is the inevitable but unforeseen result of some action taken by the hero. It is also a misconception that this reversal can be brought about by a higher power (e.g. the law, the gods, fate, or society)" (Wikipedia 2020 Online). The eventual outcome of life events is therefore 'unhappy' and a loss for the sufferer, even a disfigurement of the sufferer due to personal inability to cope further. In this sense, the tragedy is not about a specific 'choice' but an accidental fate (Heering 1964); the disempowered person is exposed to external powers and circumstances that makes it impossible to further bounce back and to continue the human struggle for survival.

I will therefore continue to describe several kinds of thoughts and descriptions on the tragedy and pain of self-termination and its connections to life events, existential conditions, and different mood swings (personal portraiture). Due to complexity and the multi-dimensionality of self-termination, the phenomenon of ending one's life, should be assessed from different perspectives (the advantage of multi-perspectivism). • The mood swing of a major depression (DSM-5) (the psychiatric portrait)

The clinical and technical definition of depression in terms of DSM-5 is that it is located in the affective as a mood swing : "Depression, otherwise known as major depressive disorder or clinical depression, is a common and serious mood disorder. Those who suffer from depression experience persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness and lose interest in activities they once enjoyed. Aside from the emotional problems caused by depression, individuals can also present with a physical symptom such as chronic pain or digestive issues. To be diagnosed with depression, symptoms must be present for at least two weeks" (DSM-5 2020). Some of the major diagnostic criteria are: a slowing down of thought and a reduction of physical movement (observable by others, not merely subjective feelings of restlessness or being slowed down); fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day; feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt nearly every day.

• The ambiguity of joy in the mode of anguish and pain (Nietzsche) (the paradoxical portrait).

For Nietzsche (Guess 1999:21) tragedy refers to a two-fold mood whereby pain awakens pleasure while rejoicing wrings cries of agony from the breast. "From highest joy there comes a cry of horror or a yearning lament at some irredeemable loss. In those Greek festivals there erupts what one might call a sentimental tendency in nature, as if it had cause to sigh over its dismemberment into individuals." The exclamation mark is accompanied by a painful question mark. The sufferer is encapsulated by two apparent opposites and becomes a victim without any power (lack of a will to power).

• The sickness unto death: Sympathetic antipathy (Kierkegaard) (The portrait of soulless apathy)

Within a more philosophical and existential approach depression is more than a mood swing. On an ontic level, one can argue that depression is not only a state of mind, but a state of being engulfed by dread, anguish and forsakenness; a condition of non-hope (inespoir) and being constantly exposed to the absurd and sheer nothingness. Every aspect of life is in fact in vain. Life in itself has become a cul de sac - no exit, vulgar and merely nausea (Sartre 1943).

Existential realities determine the realm and quality of spirituality (the human quest for meaning); they infiltrate the significance of daily living and can cause, what Kierkegaard (1967) calls, dread as the 'sickness' or 'pathology' of the human soul. In this regard, dreadful life experiences and tragedy operate like spiritual viruses, determining the health of a human being. They are causing a kind of existential threat that can 'kill' the very 'soul' of human beings in their quest for meaning, hope, dignity. Thus, S0ren Kierkegaard's emphasis on dread as an expression of soulless apathy. Encapsulated between fear and trembling (Kierkegaard 1954), apathy leads to "the sickness in the inner being of the spirit" (Kierkegaard 1954:146); it creates a kind of despair that tries to neutralise the fear of death, but, unfortunately, all attempts are in vain.

For Kierkegaard, dread can be described as the strange phenomenon of sympathetic antipathy; one fears dread and develops in anger an antipathy, but at the same time, what one fears, one desires (Kierkegaard1967:xii). Without a spiritual dimension, and bounded to merely dread, as determined by an experience of bottomless void, life becomes empty, exposed to fear and trembling. Human beings become captives of emptiness and destructive anger (Kierkegaard 1954:30). Lurking under expressions of acute anger and aggression, are the needs for life fulfilment and a secure space of unconditional love.

• The irony of irrational spiritual toughness: The absurd (Camus) (The portrait of a madman with absolute discomfort)

In his The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus (1965) pointed out the relationship between hoping and the absurd. "It's 'absurd' means it's impossible but also: 'It's contradictory" (Camus 1965: 30). For Camus to hope means to try to escape the reality of the absurd and awareness of irrationality. The 'absurd human person' simply knows that in that alert awareness "there is no further place for hope" (Camus 1965: 35). Not to hope is not despairing (Camus 1965: 75), but a kind of ironic spiritual toughness how to accept the absurd; it becomes a virtue within the awareness of the absurd, because hope implies the invariable game of eluding. "The typical act of eluding, the fatal evasion that constitutes the third theme of this essay is hope" (Camus 1965: 14).

To live is to face the absurd: "that denseness and that strangeness of the world is the absurd" (Camus 1965:19). When one faces one's mortality with the awareness of nausea (Sartre 1943), the absurd becomes the reality.

Camus describes the absurd reality as discomfort in the face of man's own inhumanity, this incalculable tumble before the image of what we are (Camus 1965: 19). What is absurd is the confrontation with the irrational (Camus 1965:24).

The leap of hope is an escape, in the alert awareness of paradox, irrationality, ambiguity, anguish and impotence (see Louw 2016). Absurd reasoning admits the irrational, simply knowing that in that alert awareness "there is no further place for hope" (Camus 1965:35). The total absence of hope has nothing to do with despair (Camus 1965: 25); it is about the courage to live the absurd even to the brave exit point of suicide; suicide settles the absurd (Camus 1965:48). Living an experience, a particular fate, is accepting it fully, thus the theme of permanent revolution. "Living is keeping the absurd alive" (Camus 1965:47). "One of the only coherent philosophical positions is thus revolt" (Camus 1965:47).

To hope is vanity, to accept imperfection is the wisdom of a mad soul. "This madman is a great wise man. But men who live on hope do not thrive in this universe where kindness yields to generosity, affection to virile silence, and communion to solitary courage" (Camus 1965: 60 -61). Futility is therefore the virtue of the madman without hope and the courage to return to hopeless labour, thus the metaphor and myth of Sisyphus, the absurd hero. "His scorn of the gods, his hatred of death, and his passion for life won him that unspeakable penalty in which the whole being is exerted towards accomplishing nothing" (Camus: 1965:97); one must imagine Sisyphus happy (Camus 1965:99).

• The yearning for transcendence: Mystical desire (désir métaphysique) (Levinas) (The portrait of an 'I' without an 'other'/ l'autre)

From a technical point of view and in terms of a psychic or psychiatric perspective, depression as mood swing could perhaps be treated. But, unfortunately, from an existential and ontic point of view, the dread of soulless apathy is to a large extent insoluble. From an existential viewpoint, 'soulless apathy,' the tempest in our very being, is difficult to cure, perhaps the only route for caregiving is to assist and help people how to live in the shadow side of life.

With this remark I do not mean that treatment and counselling cannot address the intriguing problem of 'suicide' and its link with 'depression.'

Treatment and counselling bring about a kind of alleviation, relief, and comfort. But when one probes into the deeper levels of anguish, therapy and comfort in caregiving is to provide a forum wherein the anguish finds words and language that articulate the suffocation in such a way that the dread is transferred into an external entity that corresponds with the internal existential predicament. In this way, a relationship of co-burdening is established. A transfer takes place as a kind of substitution that creates space for the expression of the anguish without feeling guilty or being judged or be exposed to therapy sessions or severe treatment (medication). Emmanuel Levinas calls this desire for 'space and place' a metaphysical desire (désir métaphysique); the significant and relational quest for the real of the 'humane other.'

Désir métaphysique

A metaphysical relation is about a relationship with an external being outside my own framework of reference, and, thus, exterior. In this respect, one should again remember Levinas' Jewish background. In Judaism, the ethical relationship is an exceptional relationship. Without compromising our human sovereignty, the contact with an external being is an advantage: It is both a connection with a source that institutes and invests (Levinas

1963:31).

Levinas sometimes writes 'the other' (l'autre) with a capital: Other (L'autre). In other cases, he uses only other (without the capital). The implication is that even Other (L'autre) can be translated as 'the other' or an 'other.' Sometimes he even uses the older form of 'others' (autrui). Others then means, specifically, the other human being (the other person), or fellow human being (Van Rhijn and Meulink-Korf 2019: 100-130))

The further implication, is, as in the case of other/Other, even the notion of 'transcendent' has many layers of meaning (Levinas 1978:192-207). In the first place, 'transcendent' refers to a relation with an end term (an ultimate entity) that cannot be reduced to the inner dynamics, the playful dynamics of interiority (jeu intérieur). Transcendent does not refer to the inner realm of human mindfulness. Furthermore, it cannot be reduced to any kind of representation within the realm of observational facticity. The metaphysical movement represents a yearning, longing, and desire for something invisible. In other words, it is about a yearning and urge that are not the result of a mere theory, thesis, or hypothesis. It is also not a mere regressive longing for a birthplace or fatherland. It is about a metaphysical desire for 'invisiblity.' The yearning for something invisible describes a metaphysical movement towards what is indeed transcendent and outside the grasp of mere intellectuality. The transcendent as longing is an inadequacy (the insufficient ability of reason), and, thus, essentially and necessarily a transcendence (désir métaphysique) (Van Rhijn and Meulink-Korf 2019). The existential unrest, the fact that I am addressed by the visage and challenged not to present carelessness, creates a humane condition (condition humaine) par excellence. The deficiency of being is about being addressed and directed by the relation with the other. It constitutes the alterity of being (metaphysical relationship). The suffocating human being then finds an external point of justice that safeguards human dignity, a non-judgemental space of 'home' - the intimacy of grace and unconditional love; a space for forgiveness and reconciliation, re-connectedness in the sense of belonginess. In terms of Levinas, fellowship, intimacy and a sense of belongingness is to become aware of a metaphysical trace - the peculiar trace of the Other. The challenge is not to try and track the footprints, because in themselves they are not signs. One should rather reach out to all the Others that reside in the footprint of 'illeity' (phenomenology of impersonal being; a sign or trace in the empirical sphere that refers to transcendence: He is there) (Levinas 1990:99).

• The insoluble, mysterious inexplicable problem: 'Inespoir' (unhope) -destructive resignation (désespoir; Bollnow, Marcel) (The portrait of the dark night of the soul)

The concept of depression is complex and many-layered. Anguish as an expression of a total absence and lack of hope is to my mind a more appropriate description of the dreadful disposition contributing to the decision to end one's life. Dread describes our fear for loss, our fear for rejection; i.e., anxiety as anguish regarding the meaning of life; a condition of hopelessness; anxiety as a condition of soulless darkness - apelpizö (nonhope. Anguish as the tempest between life and death; being exposed to the ambiguity of the quest for light within the shadow and "dark night of the human soul".

"In an obscure night; Fevered with love's anxiety; (O hapless, happy plight!); I went, none seeing me; Forth from my house, where all things quiet be" ( St John of the Cross).

Existential dread stems from an unarticulated disposition determined by the despondency of non-hope (apelpizö): The existential resignation before the threat of nothingness. The antipode of hope is therefore not merely despair, but hopelessness as the disposition of indifferentism, sloth, and hopelessness (Bollnow 1955:110). The French philosopher Gabriel Marcel called this desperate situation of dread without a meaningful sense of future anticipation, unhope (inespoir) with the eventual threat of destructive resignation: désespoir (Marcel 1935:106). • The spiritual interlude: Between hopelessness (non-hope of dreadful resignation) and hoping (yearning for 'geborgenheid' and soulful wholeness -being at home) (Portrait of a displaced human being)

E. Brunner (1953:7) captured the philosophical disposition after World War II: hope destroyed by anxiety and the threat of annihilation. For Brunner anxiety is the negative mode of hoping and expectation. Edmaier (1968:49) asserts that the need for hope surfaces within the experience of loss, dread, and the threat of destructive annihilation. The affective mode of hope, hope as a mood swing, is thus linked to the dynamics between threat/anxiety and expectation (see Louw 2016).

According to Heering (1964:17-20), the root of the connection hope-anxiety can be traced down to the metaphysical pattern of thinking in Greek philosophy. When tragedy is the overarching philosophical paradigm for the interpretation of the meaning of life, as in the case of classic Hellenism, fate (moira) becomes the dominating paradigm of interpretation. A philosophy of life, constructed by a fatalistic schema of interpretation and a nihilistic metaphysics, is manifested in a mood of dread, anxiety, and guilt. Hope could then be rendered rather as a vice (as in the Pandora legend), or a bad affect (the scepticism of Stoic philosophy) than a positive virtue. Hope therefore causes disillusionment and disappointment and thus should be avoided (Louw 2016).

Dread is always embedded in cultural contexts. While facing existential dread and the fear for death, it is the emphasis on the cult of self-realisation in a market driven economy (achievement ethics) that often triggers an absolute form of despair: The fear to be oneself and the awareness of not being oneself (Kierkegaard 1953). The imperative of self-actualisation and self-maintenance within a life-view fed by psychological optimism, leads inevitably to severe doubt and the notion of fear and trembling. "The hopelessness in this case is that even the last hope, death, is not available" (Kierkegaard 1953:151). Without a sound foundation of trust and faith, despair, hopelessness (apelpizo) sets in (Kittel 1935:530). The result is a life of resignation without the prospect of something new and different. Thus, the inescapable tragedy of an interlude between life (the urge for light, meaning) and shadow (the suction power of a death wish).

Self-termination: The aesthetics of ugliness and dereliction (a theological perspective) (Portrait of a forsaken God)

Within the ambiguity, paradox, of the "toughness of the human soul" (the despair as futile bouncing back), and "soulless apathy" (anguish and dread), what should be a theological response within the framework of a Christian paradigm?

My hunch is, in order to address the desperate condition of inespoir from the perspective of pastoral theology, the following Christian spiritual proposition could instil a kind of consolation in pastoral caregiving, linking the sufferer to a 'suffering God' (the theopaschitic perspective) and establishing connection between the human pain and a divine mode of identification: The divine suffocating cry without an answer (dereliction): "My God, my God, why hast do forsaken me? And forsakenness is about the ugliness of dread and dying as articulated by the suffocating, dying Son of God.

I, therefore, want to address the problem of self-termination from the perspective of dereliction (Moltmann 1966): Forsakenness as the desperate cry without any answer. From the perspective of sheer ugliness, but framed by grace and hope. Such an effort recognizes that God especially loves those who suffer in the darkness of depression. "Suicide then is not an act that calls for divine punishment, but an all-too-common threat that calls us to reaffirm hope in life as a precious gift given by God" (Schmalz 2018:2).

The following remark of the young Benedictine novice in the monastery of Melk summarizes it all: "But we see now through a glass darkly, and the truth, before it is revealed to all, face to face, we see in fragments (alas, how illegible) in the error of the world, so we spell out its faithful signals even when they seem obscure to us and as if amalgamated with a will wholly bent on evil" (Umberto Eco: 1980:11).

According to Umberto Eco, all the synonyms for 'ugly' contain a reaction of disgust if not violent repulsion, horror or fear (Eco 2007: 16): "In truth, in the course of our history, we ought to distinguish between manifestations of ugliness in itself (excrement, decomposing carrion, or someone covered with the sores who gives off a nauseating stench) from those of formal ugliness, understood as lack of equilibrium in the organic relationship between the parts of a whole" (Eco 2007: 19).

With reference to spirituality, spiritual ugliness resides in the disorientation and disintegration of ethos: The qualitative disposition of a human being's being functions. Spiritual ugliness is related to disintegration within the realm of meaning and significance. As a threat to human dignity, spiritual ugliness can be related to inhumane experiences of discrimination and stigmatisation, perceptions of stereotyping and prejudice; dispositions of rejection, failure, disappointment; immoral behaviour or corruption, fraud, rape and violence. Spiritual ugliness creates the nausea of insignificance due to the loss of wholeness. The organic relationship between the parts of the whole has been destroyed and fragmented in a chaotic way (to produce non-sense). The disturbance in wholeness leads to inhumane experiences of being robbed of human dignity because of the abuse of power.

Instead of theodicy as a rational attempt to explain suffering and to 'save' the omnipotence and benevolence of God, a theology of the cross describes an agapêdisee: forsakenness (derelictio) as the proof of Gods faithfulness and kenotic love, and, thus, the foundation of all modes of hope that are engaged in dread as the sickness onto death.

Moltmann's intention (1972:30) is to make theology relevant to the question of suffering. He sees the cross as the definitive point of identity for a Christian theology, which attempts to bring pastoral comfort and liberation. The theology of the cross is a critically liberating theology of God, whose attention is focused on the distress of suffering and human existence in the world. Theology, in the light of the crucified Christ, becomes liberating and practical, thereby transforming the inhuman schisms and discrepancies that exist between people in praxis. The theology of the cross once again emphasizes the solidarity of God in the midst of the history of suffering.

Moltmann's theology of suffering should not be confused with the mysticism of the medieval times. Moltmann does not regard suffering as a medium through which human beings arrive at some inner mystical communion with Christ. Rather, suffering expresses the following pastoral truth: Suffering can only be overcome by suffering (Moltmann 1972:49). Only a suffering God can help. Via the cross, suffering becomes God's active participation in the suffering of lonely humanity. In Christ, suffering becomes Messianic and liberates humankind from suffering. A theology of the cross becomes a theology of hope because Christ suffered victoriously on the cross. As such, it offers a way to cope with suffering through Christ's active resistance towards all suffering. God's identification with suffering is active resistance and a demonstration against suffering (Louw 2016: Chapter VII).

By this premise, Moltmann breaks away from Aristotle's metaphysical and theistic view of God as being immovable, apathetic and unchanging. A theology of the cross means a radical change in Western Christianity's concept of God. The God-concept inspired by the Greeks is one of apathy, with immutability as a static-ontic category. In contrast, a theology of the cross is a 'pathetic theology' in which God's pathos, not his apatheia, is emphasized. It is in pathos that God reveals Himself in such a way that He becomes involved in loving solidarity with human suffering. An apathetic God moulds a human being into a homo apatheticus; a pathetic God moulds a human being into a homo sympatheticus.

In Jesus' resurrection, God is the God in action; in the crucifixion, He is the God in passion. The latter is not a static God, but a dynamic God, who is actively involved in the God-forsaken cry/lament of Christ on the cross: "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" Jesus' cry from the cross (derelictio) outlines a Trinitarian theology of the cross. This cry defines God's 'how?' in suffering: Divine compassionate being-with.

I want to end this exposition with a very strange conclusion: The portrait of a lonely, forsaken Son of God displays a prospect and vista of comfort without an answer; the void, lonely space of a cry; the urge for 'sunshine' within the desperate pit of dark shadows; the voiceless voice of divine forsakenness as the poetry of a suffocating soul. Nothing can prevent human beings to live in the inescapable interlude between death and life; the only route within the dark night of the soul is to turn to 'divine forsakenness' as mirror of one's own soul and source of spiritual comfort: Accepted by unconditional, sacrificial love and grace.

The inescapable interlude between light and shadow: Encapsulated by divine forsakenness

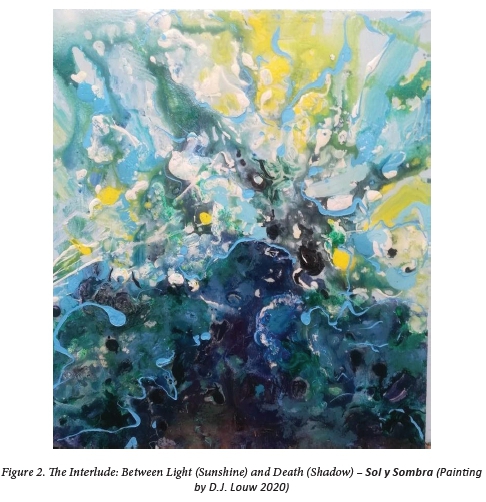

In reflecting on his journey through life, I want to dedicate the painting (figure 1) to Andre's life dream; i.e. to establish hospital care as a pastoral and spiritual endeavour of compassionate being-with the other in his/ her struggle between health and sickness; between healing and weakness; between the urge for well-being (meaningful living) and the unescapable and unavoidable factuality of death and dying. Within this rather paradoxical struggle, I call this painting: Interlude - the struggle between life (light) and death (shadow, darkness). In terms of the poet Uys Krige (2020 Online), the ambivalence of life oscillates between light (with sun as the symbol) and destruction - the shadow side of life (Sol y Sombra).

During World War II, Krige was a war correspondent with the South African Army during the North African Campaign. Captured at the Battle of Tobruk in 1941, he was sent to a POW camp in Fascist Italy from which he escaped two years later. He returned to South Africa after learning to speak fluent Italian. Afterthe ultra-nationalist and White Supremacist National Party took power over South Africa in 1948, Krige actively campaigned against the efforts of the new government to disenfranchise Coloured vote rs (Krige 2020 Online).

In his later life, Krige served as a mentor to fellow Afrikaner poet Ingrid Jonker and played a major role in her transformation from the dutiful daughter of a ruling Party MP into a vocal critic of the ruling National Party and its policies of both literary censorship and apartheid. When Jonker committed suicide by drowning in 1965, Krige spoke at her secular funeral (Krige 2020 Online).

In 1994, Uys Krige's granddaughter, Lida Orffer was murdered with her family at their home in Stellenbosch. The murderer was found to be a Black South African drifter whom the Orffer family had given his first real job. The murder of the Orffer family, which came within weeks of the free elections that toppled the ruling National Party and ended apartheid, horrified the town of Stellenbosch and made many local residents question whether Nelson Mandela's promise of a "rainbow nation" was truly possible (Krige 2020 Online).

We live indeed every day in the inescapable paradox of Sol y Sombra (see figure 2).

The spirituality of 'Deep River': Transcendent longing (the urge for liberation) within the irony of 'Jack of Spades'

In 1936, deprived of morphine for some days, the South African poet Eugène Marais, borrowed a shotgun on the pretext of killing a snake and shot himself in the chest. The wound was not fatal, and Marais therefore put the gun barrel in his mouth and pulled the trigger. He did so on the farm Pelindaba, belonging to his friend Gustav Preller. For those who are familiar with the dark moods of certain of Marais' poems, there is a black irony here; in Zulu, Pelindaba means 'the end of the business' - although the more common interpretation is 'Place of great gatherings' (Eugène Marais 2020 Online).

Eugène Marais articulates the desperate pain of suffocating as follows (translation by author):

"Oh, Deep River, Oh Dark Stream; How long did I wait, how long did I dream, The blade of love stirring in my heart? - In your embrace all my sorrow ends".

On March 29, 1936, a sad and rainy day, Marais could no longer; he found himself on the brim of despair. For more than a mile he wandered through the rain to a neighbour, Lood Pretorius, and asked to borrow a bullet gun. A short distance from Pretorius's house, Marais shot himself in the head (Eugéne Marais 2020 Online).

The experience of existential dread (the tragedy of an irreversible fate) is captured in his poet: SKOPPENSBOER (Jack of spades) (translation by the author).

"A drop of bile is in the sweetest wine; a tear is on each 'merry' string, in every laugh a sigh of pain, a dull leaf in each rose. The one lurking through the night; watching while we have fun; but laughing last, is Skoppensboer (Jack of Spades)".

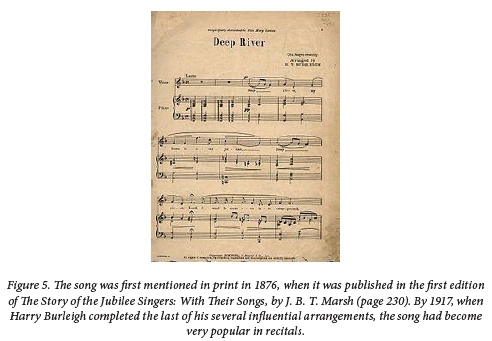

Deep River

It has been called "perhaps the best known and best-loved spiritual" (Deep River Wikipedia 2020 Online). The song articulates the deep undertone of anguish as well as a yearning for coming home (connectedness and a sense of belongingness, acknowledgement, and identity.

Deep river, My home is over Jordan. Deep river, Lord, I want to cross over into campground.

A last tribute (the end)

André died in the void, suffocating space of the forsakenness of the dying Christ with the yearning (désir métaphysique) for 'sunshine.' He wrote as preface in the book Hold onto Him by his wife, Annette De la Porte (2018:1): "Depression is also ... smaller than you. Always, it is smaller than you, even when it feels vast. It operates within you; you do not operate within it. It may be a dark cloud passing across the sky, but - if that is the metaphor -you are the sky. You were there before it. And the cloud can't exist without the sky, but the sky can exist without the cloud."

We who are in mourning, honour your indeliberate choiceless act. We do not have a song to sing yet, therefore we lament and pray. May the sky and transcendent realm of a divine space of resurrection light illuminates your being-with ... May we all be comforted by the divine anguish expressed in the suffering Christ: "He [Jesus] offered up prayers and petitions with loud cries and tears to the one who could save him from death" (Heb. 5:7).

The point is: Both the resurrection perspective, as well as the notion of comfort, do not deal with the act of dying or the how of death. Rather than to moralise on issues regarding 'afterlife' and the disposition of the deceased, death had been reframed by the dereliction of Christ. In his cry of forsakenness, He captured our human anguish, desolation, and absolute expression of meaninglessness - from a human point of view everything can indeed be rendered as in vain. But, from the vintage point of divine victory over death, even our struggle with an 'unbearable toil' culminating into self-termination, can become meaningful, and, in this sense, an expression of hope - the aesthetics of resurrection faith! In this sense, the forsakenness of a dying Christ, becomes a source of comfort expressing the compassion of a living God!

Dostoyevsky concurred with the assumption that without compassion life, becomes an unbearable toil. Compassion makes life bearable. "Compassion would teach even Rogozhin, give a meaning to his life. Compassion was the chief and, perhaps, the only law of human existence" (Dostoyevsky 1973: 263). "God's rejoicing in man, like a father rejoicing in his own child" is to Dostoyevsky the fundamental idea of Christianity (1973:253).

Bibliography

Bollnow, O. F. 1955. Neue Geborgenheit. Das Problem der Überwindung des Exsistentialismus. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. [ Links ]

Brunner, E. 1953. Das Ewige als Zukunft und Gegenwart. Zürich: Zwingli Verlag. [ Links ]

Camus, A. 1942. Le Mythe de Sisyphe. Essay sur L'absurde. Paris: Gallimard. [ Links ]

Camus, A. 1965. The Myth of Sisyphus. London: Hamish Hamilton. [ Links ]

Clark D K. 1996.' Euthenasia.' In D K Clark, R V Rakestraw (eds), Readings in Christian Ethics, Vol. 2. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 95102.

Dark Night of the Soul. 2020. Wikipedia. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dark_Night_of_the_Soul. [Accessed: 07/06/2020].

De la Porte, A. E. 1988. Pastoraat aan die pasiënt met brandwonde. Die problematiek van liggaamskending in teologiese perspektief. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Faculty of Theology, University of Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Deep River (song). Wikipedia. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deep_River_(song). [Accessed: 06/06/2020].

De la Porte. A. 2018. Hold onto Him. Email address author: annettedlporte@gmail.com. Belville.

Devji, F. 2005. Landscapes of the Jihad: Militancy, Morality, Modernity. London: Londres, Hurst & Company Ltd. [ Links ]

DSM-5. 2020. What is depression? Diagnostic Criteria. [Online]. Available: https://www.psycom.net/depression-definition-dsm-5-diagnostic-criteria/ [Accessed: 07/06/2020].

Dostoyevski, F. 1973. The Idiot. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Edmaier, A. 1968. Horizonte der Zukunft. Eine philosophische Studie. Regensburs: Verlag Friedrich Pustet. [ Links ]

Eco, U. 1980. The Name of the Rose. London: Secker & Warburg. [ Links ]

Eco, U. 2007. On Ugliness. London: Harvill Secker. [ Links ]

Eugéne Marais. 2020. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eug%C3%A8ne_Marais [Accessed: 06/06/2020].

Etymology of suicide. 2020. Suicide. In Merriam Webster Dictionary. [Online]. Available: www.merriam-webster.com.Assessed;07/06/2020

Friedman, E. H. 1985. Generation to Generation. Family Process in Church and Synagogue. New York: Guilford. [ Links ]

Geuss, R. 1999. 'Tragedy'. In Ronald Speirs (ed.), The Birth of Tragedy and Other Writings, Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. [ Links ]

Guinness, O. 1973. The Dust of Death. Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press. [ Links ]

Heering, H. J. 1964. Tragiek. Van Aeschylus tot Sartre. 's-Gravengage: Boekencentrum. [ Links ]

HospiVision 2020. Touching Lives and Giving Hope. [Online]. Available: https://www.google.com/search?q=hospivision&rlz=1C1GCEU_enZA873ZA873&oq=HospiVisio&aqs=chrome.1.69i57j0l7.38141j0j15&sour ceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 [Accessed: 07/06/2020].

Kierkegaard, S. 1954. Fear and Trembling and the Sickness onto Death. New York: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Kierkegaard, S. 1967. The Concept of Dread. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Kittel, G. 1935. Elpis (Hoffnung). Theologisch Wörterbuch zum Neuen Testament, Band 2, Stuttgart Kohammer Verlag.

Krige U. 1948. Soly Sombra. [Online]. Available: https://www.google.com/search?q=Sol+y+Sombra+Uys+Krige&rlz=1C1GCEU_enZA873ZA873&oq=Sol+y+Sombra+Uys+Krige&aqs=chrome..69i57.19644j0j15&sourceid=chro [Accessed: 05/06/2020]. First published in Pretoria: Volkspers Bpk.

Krige, U. 2020. Uys Krige. Wikipedia. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uys_Krige [Accessed: 05/06/2020].

Levinas, E. 1963. Difficile liberté, Essais sur le judaisme. Paris: Editions Albin Michel. [ Links ]

Levinson, E. 1978 (4). Het menselijk gelaat. Baarn: Ambo

Levinas, E. 1990. Humanisme van de andere mens. Kampen: Kok. [ Links ]

Louw, D. J. 2008. Cura Vitae. Illness and the Healing of Life. Wellington: Lux Verbi. [ Links ]

Louw. D.J. 2016. Wholeness in Hope Care. On Nurturing the Beauty of the Human Soul in Spiritual Healing. Berlin: Lit Verlag. [ Links ]

Marcel, G. 1935. Être et Avoir. Montaigne: Ferned Aubier. [ Links ]

Migliore, D. L. 2004. Faith Seeking Understanding. An Introduction to Christian Theology. (Second Edition). Grand Rapids/Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Martin, E. B. 2018. 'A Historical Perspective on Suicide'. Psychiatric Times, vol.35, issue 7, 27th July 2018: 1-4. [ Links ]

Moltmann, J. 1972. Der gekreuzigte Gott. München: Kaiser. [ Links ]

Nelson, J B. 1984. Human Medicine. Ethical Perspectives on Today' s Medical Issues. Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House. [ Links ]

Raphael, B. 1984. The Anatomy of Bereavement. A Handbook for the Caring Professions. London: Hutchinson. [ Links ]

Sartre, J-P. 1943. L'Être et le Néante. Paris: Gallimard. [ Links ]

Schmalz, M. 2018. Why religions of the world condemn suicide. [Online]. Available: https://theconversation.com/why-religions-of-the-world-condemn-suicide-98067 [Accessed: 06/06/2020.

Schoeman, K. 2017. Slot van die dag. Pretoria: Protea Boekhuis. [ Links ]

Signalness, J. 2019. If Someone Commits Suicide will They Still Go to Heaven? [Online]. Available: https://bismarckdiocese.com/news/if-someone-commits-suicide-will-they-still-go-to-heaven [Accessed: 06/06/2020].

Sullender, R. S. 1985. Grief and Growth. Pastoral Resources for Emotional and Spiritual Growth. New York: Paulist. [ Links ]

Wikipedia. 2020. Tragedy. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tragedy#cite_note-FOOTNOTENietzsche199921%C2%A72-4 [Accessed: 07/06/2020].

Van Rhijn, M.A. and J. N. Meulink-Korf. 2019. Appealing Spaces, the Ethics of Humane Networking. The Interplay Between Justice and Relational Healing in Caregiving, transl., D. J. Louw. Wellington: Bybelkor.

Wikipedia. 2020. Christian Views on Suicide. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_views_on_suicide [Accessed: 06/06/2020].

1 The article is a tribute to the late chaplain and "compassionate friend" in his desperate yearning for "sunshine": André De la Porte. André obtained his doctoral degree under my supervision in 1988 on hospital care, with special focus on patients suffering from burns and corporeal, bodily harms (disfigurement) and impairments: A. E. De la Porte, Pastoraat aan die pasiënt met brandwonde. Die problematiek van liggaamskending in teologiese perspektief (Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Stellenbosch, 1988). After many years of struggling with depression, he terminated (took) his life on 30th of May 2020.