Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

On-line version ISSN 2413-9467

Print version ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.5 n.2 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.supp.2019.v5n2.a25

ARTICLES

The voice of the congregation – a significant voice to listen to

Schoeman, Kobus

University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa SchoemanW@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The voice of the congregation is one of the four constituting elements of preaching. Preaching is directed at the congregation but also originates from the congregational context and reflects on the theological framework of the congregation. The lived religion and theological understanding of the congregation is an important marker in this regard.

The attender survey of the National Church Life Survey (NCLS) was done in 2014 in the Dutch Reformed Church and provides, from an empirical perspective, useful and relevant information to the preaching event. The NCLS identifies vital and nurturing worship as an important core quality in congregation life, and this is used to listen in a reliable way to the voice of the congregation.

Keywords: Preaching; congregation; National Church Life Survey; lived religion, context

A sermon without an address is a sermon that could have been delivered at any address in any place at any time. This is a sermon without a congregation. Careful preachers will listen closely to the text, read themselves and understand the congregation in which they will preach (Farris 2008:266).

Cilliers (2004:23-24) in the development of his theoretical framework identifies four basic elements or voices of preaching. The first and probably the constitutive voice is the Gospel as an act of the triune God with the crucified and resurrected Christ in the centre. The Bible as the Word of God used by the preacher as a witness to the presence of the living God is the second voice and the voice of the congregation within a specific context and the preacher communicating to them in in their language and a conceptual sphere is identified as the third voice. The preacher, as the fourth voice, points towards and witnesses about Christ in the formation of a sermon.

The four voices inform the following definition of preaching: "The wonder of preaching takes place when, through an act of the Spirit, these elements converge to become so related that God reveals Himself to a congregation through the Bible and the preacher" (Cilliers 2004:24). The aim of this article is to explore, in reflection on the work of Cilliers, the voice of the congregation as an element in the wonder and process of preaching.

This article focusses on the theoretical and the empirical aspects of the analysis of the congregational voice, to explain the role of the congregation as a third voice in the preaching process. From a theoretical perspective, preaching is directed at the congregation but also originates from the congregational context. Preaching is a congregational and contextual event (Cilliers 2004:135). The voice of the gospel creates a liminal space where new perspectives are possible, where preacher and congregation learn to look and speak (Campbell and Cilliers 2012:102). The voice of the congregation should, from a theoretical perceptive, be taken seriously in the process of preaching.

The second focus of this article is to listen to the voice of the congregation from an empirical perspective. The attender survey of the National Church Life Survey (NCLS) was done in 2014 in South Africa and provided, from an empirical perspective, useful and relevant information from an attender perspective to inform the preaching event1. Is the preacher preaching to fools or what is their experience of the sermon and worship service? The NCLS identifies vital and nurturing worship as an important core quality in congregation life,2 and this is used to listen in a reliable way to the voice of the congregation.

1. The voice of the congregation - a theoretical reflection

The voice of the congregation is an important voice for the preacher as the sermon doesn't belong to the preacher, but to the congregation, the communio sanctorum constitutes the place where the sermon is heard and acted upon (Cilliers 2004:36). Preachers should learn to listen to the congregational voice and ask themselves if their own voice hasn't become the only audible and exclusive voice. "In the light of a congregation's many voices, preachers need to examine themselves and find their place playfully in the bigger picture, with the prayer and hope that the truth of the Gospel will indeed be heard and obeyed in the congregation's many voices." (Cilliers 2004:37). The preacher can't ignore the voice of the congregation and should listen carefully to it.

The voice of the congregation, amongst the four voices, is an important voice. The focus on the congregation and its context imply that the preaching attains a relevant and unique character (Cilliers 2004:144). If this voice is not heard the message becomes irrelevant. If the people are not met within their context and struggles, they are not met at all. The voice of the congregation is about their context and about the theological framework the members work with. The context and theological framework of the members are an essential part of worship and preaching and not an optional extra.

The voice of the congregation involves, in the first place, from a theoretical perspective, the context of the congregation. What is the role of the context in understanding the voice of the congregation? Cilliers (2004:146-149) identifies three contours of contextualizing the congregational voice: language, form, and hermeneutical skills. The message of the Word should be formulated in a language relevant for the present context. The Scripture has a message for this context preached and explained in understandable words. The congregation should hear and understand the message as speaking and informing them in their world with its unique challenges.

Although the text is decisive for the form of the sermon it may not always be the same. The context asks and sometimes demands that the form may vary in creative and innovative ways. Communication and rhetorical strategies need to acknowledge current innovations and developments. Social media and technology are changing the way in which we communicate, the difference between the Gutenberg and Google generations illustrates the point (see Sweet 2012 [Kindle]).

The hermeneutical skills of both the preacher and the congregation help them to contextualize the message of the Word. This a discourse between text and context for both the preacher and the congregation. The task for preacher and congregation is, in the space of the sermon and beyond, to "... reinterpret repeatedly the spirit of the times in the light of God's Kingdom, to distinguish what truly is important." (Cilliers 2004:149). The critical question is: Are both the preacher and the congregation working with the same hermeneutical skills?

The voice of the congregation is, in the second place, informed and formed by a theological framework. The congregation is a social construction and organization but has also a theological identity and may be defined by a core theological understanding (Farris 2008:267). The preacher should also look from a theological perspective at the congregation, they constituted in their gathering and communion as God's people. The preacher should see the people in the pews "... as gifts of God, rather as religious clients whose interests must be dealt with as well as possible." (Cilliers 2004:133). They should be seen, from the perspective of the preacher, in the first-place as believers and not only religious consumers.

The theological framework and understanding of the attenders are therefore important. "In a congregation, there are people with different views of God, which they built up over the years, inter alia by reading the Bible and hearing sermons about the Bible. These congregational perceptions are a reality which we, in preaching, cannot or may not disregard" (Cilliers 2004:136). Theology is expressed and lived in ordinary communities and coexist or in contradiction with institutional or formal theology. The congregation and the minister may adhere to the formal or official theology but the individual members may have a whole range of different personal theologies that they live their lives by (Ward 2017:56). Every congregation through its members have a vibrant lived theology that is articulated in different ways.

The theological voice reflects not only in the lived religion of the membership but also through a tradition of interpretation, the church has worked with the text in the history, what Cilliers (2004:132) calls the "hermeneutics of ecumenicity". The reading of a text is not an isolated and private practice of the preacher, but the history and tradition of interpretation protect the preacher against arrogance and a singlemindedness. The ecumenical tradition of interpretation is an integral part of the theological voice that must be heard by the preacher and also resonating in the voice of the congregation.

The preacher should have an openness to listen before the sermon to the voice of the lived religion of the congregation and the ecumenical tradition. An empirical voice may help in this regard. During the sermon, the congregation should have the experience of being listened to and being involved with and in the sermon as they reflect on their contextual questions and challenges. After the sermon, they go and live and do it and the congregation become the preachers and witnesses of the Word. Their theological and contextual frameworks should be heard and respected through the whole process of preaching. The next step is to explore the possibilities of an empirical voice.

2. Listening to the congregation - an empirical voice

The empirical perspective gives a voice to the congregation about their experience of the sermon and worship service. This information should be relevant and reliable to inform the preacher in the process of preparing, conducting and reflecting on the preaching process. The National Church Life Survey (NCLS) is in this instance used an empirical tool.

The NCLS was developed in 1991 in Australia to evaluate congregational life (see Kaldor, Castle and Dixon 2002). In 2001 the survey was expanded to include churches from Australia, New Zealand, UK, and USA (see Bruce and Woolever 2010). The Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) became part of this research project in 2006 and the survey was done in 2006 (see Schoeman 2010), 2010 (see Schoeman 2015) and in 2014. The main empirical focus in this article is on the 2014 survey and results from 2006 and 2010 are used, where needed and available, to describe certain changes in the responses.

The NCLS is quantitative survey completed by the membership of congregations. All attenders (fifteen years and older) of a worship service are requested to complete a hard copy of the questionnaire (Pepper, Sterland and Powell 2015:9). The result of the survey gives a voice to the congregational members (Erwich 2012:73). The voice isn't representative of all the members of the congregation, but it is an important voice to listen to as it provides reliable information about congregational life from an attender perspective (Hermans and Schoeman, 2015:60). This survey is a helpful tool to articulate the voice of the congregation as part of the preaching process.

The NCLS questionnaire was used in the DRC surveys.3 In 2010 and 2014, a simple random sample of 10% was selected from the DRC congregations. The response rate was 75% in 2010 (12 286 questionnaires from 85 congregations) and 82% in 2014 (16 808 questionnaires from 106 congregations).

The sample population for the 2010 and 2014 surveys has the following characteristics:

• Age: In 2010 the average age was 53 years and 4 months and in 2014 52 years and 11 months.

• Gender: In 2010 58% were female and 42% male and in 2014 57% female and 43% male.

• Marital status: First marriage - 60% (2010 - 61%), never married -15% (2010 - 11%), widowed - 10% (2010 - 12%).

• Education: 55% have a tertiary education (52% in 2010).

• The majority of the members (55%) are employed (47% in 2010. In 2014 29% were retired and in 2010 265).

Faith practices of the attenders

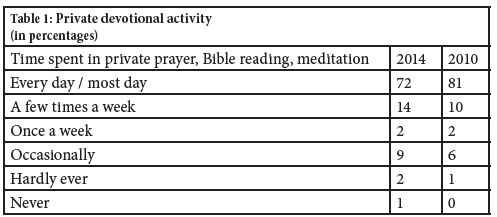

The faith practices and rituals of the attenders are an important part of the fostering of their relationship with God. They practice private devotional activities like Bible reading, prayer, and meditation, but also through public activities as attending worship services and listening to sermons. Table 1 gives an indication of the role of private devotional activities of the attenders. It is evident from Table 1 that frequent participation in activities like Bible reading and prayer are a significant part of the private religious life of attenders.

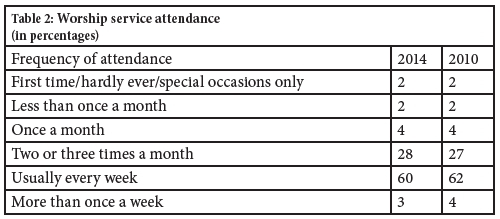

The attendance of worship services (Table 2) is an important faith practice to the attenders as 60% attends the services usually on a weekly basis. If the changes over time between 2010 and 2014 are compared for both tables, there was a slight decrease in the frequency in both faith practices.

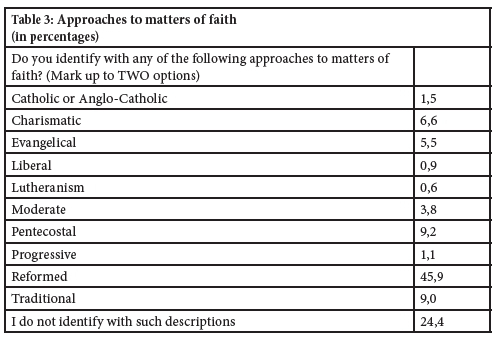

The conclusion may be made that both faith practices (private and public) play an important role in the religious life the DRC attenders. The voice of the congregation in this regard is a devoted voice that is serious about private devotion and worship attendance. This is, however, not a homogeneous voice (see Table 3). The majority of attenders, as could be expected form DRC members, identify with a reformed approach to matters of faith, but there are also other approaches that need to be respected in listening to the congregation. This may be an indication of the diversity within that are present amongst the lived theology of the attenders?

Vital and nurturing worship as a core quality

The NCLS research identified, over more than 20 years of their research, nine core qualities4 that are important to congregational life (Powell et al. 2012:7). Vital and nurturing worship is one of these core qualities and is the focus of this section. The following are, regardless of the form of worship, the empirical indicators used to describe vital and nurturing worship as a core quality:

The experience of inspiration, joy, God's presence, understanding of God, challenges to act during a worship service are asked about. The helpfulness of the preaching towards the life of the attender. The role of music and singing are playing as an important part of the worship (Powell et al. 2012:22).

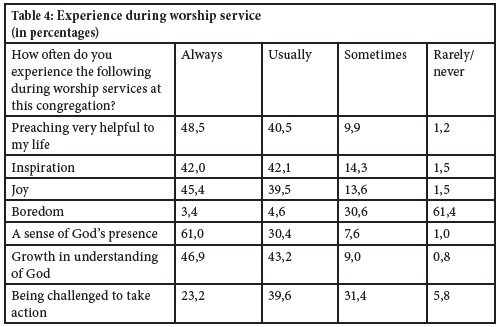

Table 4 reports on the experience of the attenders during the worship service. The most prominent experience of the service is a sense of God's presence (61% always), "... at the heart of worship is an encounter with the living God, and true worship involves human beings falling down before God's presence" (Long 2001:19). The attenders also experience inspiration and joy during the worship service and rarely or never boredom (61,4%). Congregations where ". higher percentages of attenders always feel inspired are also more likely to be growing churches." (Powell et al., 2012). In comparing the responses of the attenders who always or usually find the worship inspiring (see Figure 1) it can be seen that there was an improvement from 2010 to 2014.

Attenders find the preaching very helpful to their life (always/usually 89%) but they are not always being challenged to act as a result of the service (always 23,2%). This may be that they feel that they are not challenged to act or that the sermon has not a clear contextual relevance? Their experience of growth in the understanding of God may, therefore, be relevant to their personal devotional life (see Table 1) and not as part of a broader social engagement.

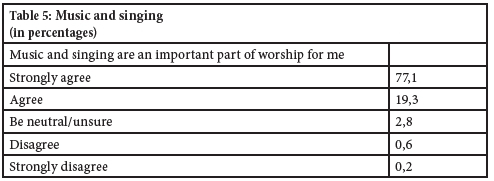

Music and singing are an important and significant component of the worship service. Long (2001:64) emphasizes the importance of song and music: "The congregation sings and plays musical instruments, and music holds the service together from beginning to end. The music is selected out of alertness to the moment in worship - a vigorous hymn of praise here, a reflective lament or a hopeful chorus there." Table 5 indicates that the attenders have a strong positive experience of music and singing in the worship service.

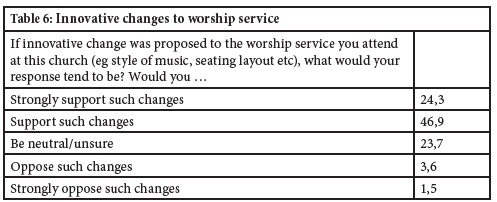

Should changes and innovation be implemented in the worship service or should the format of the sermon and the liturgy always stay the same? There may be a perception that attenders are not in favour of change and innovation, but Table 6 indicates that this is not the case and that the attenders are positive about innovation and change to the worship service.

The core elements are an important part of the congregational voice as the different elements have a cumulative effect, "... on its own has only a small impact, but together their effect is substantial" (Powell et al. 2012).

The preacher should reflect on all the different core aspects and be open to innovation and change.

The Word and the congregation

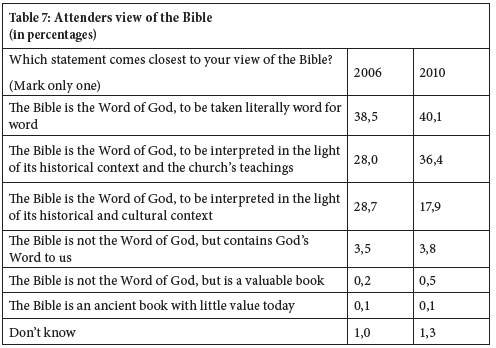

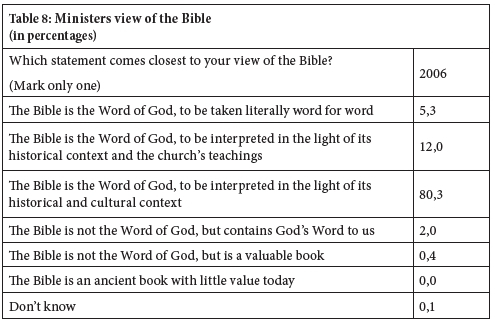

The voice of the Word is an important part of the preaching process and both the preacher and the congregation interpret this voice as part of a hermeneutical and exegetical process. The question is: how do the preacher and the congregation read and understand the Word? Attenders and minsters were asked about their view of the Bible (see Table 7 for the attenders5 and Table 8 for the ministers6).

The attenders read the Bible as the Word of God, to be taken literally word for word (40,1% in 2010) or the Bible as the Word of God, to be interpreted in the light of its historical context and the church's teachings (36,4% in 2010). The majority of the ministers (80,3%) view the Bible as the Word of God, to interpret in the light of its historical and cultural context. Both the attenders and the minister see the Bible as the Word of God, but from there on the difference is important. The attenders either interpret it literally word for word or in the light of its historical context and the church's teaching. The ministers read and interpret the Bible in light of its historical and cultural context.

The result of this difference of interpretation is that members in the pew prefer and want to listen to a more literal interpretation and the preacher construct the sermon around a historical and contextual interpretation of the Word. The congregation may not hear the voice of the preacher and this may lead to a misunderstanding of the voice of the Word. The relevant question is not who is right and who is wrong, but the empirical findings illustrate that a serious misinterpretation is possible in listening to the different voices in the preaching event. The preacher should take the voice of the congregation, as part of their lived religion, in this instance serious in order the be heard. This discrepancy has significant implications for the process of preaching. The preacher may create spaces where he or she may listen to the voice of the attender in the in the congregation, may be in small group discussions?

Worship and preaching in the congregation

The worship service remains a very important element in congregational life and in the religious lives of its members. The NCLS 2014 survey enquired about the aspects of the congregation that the attenders most valued and that should be preserved or strengthened. Their responses in order of importance are the following:

1. Sermons, preaching or Bible teaching

2. Sharing in Holy Communion/the Eucharist/Lord's Supper

3. Wider community care or social justice emphasis

4. Practical care for one another in times of need

Sermons and preaching are the most valued by the attenders and they affirm that this is an important aspect of congregational life. The Holy Communion is valued as the second most important aspect of the congregation. The voice of the congregation is that they value the meeting and worship on a Sunday.

The NCLS 2014 survey also asked the attenders to select the aspects of the congregational life they would most like to see given greater attention in the next 12 months. Their responses in order of importance are the following:

1. Worship services that are nurturing to people's faith

2. Spiritual growth (eg spiritual direction, prayer groups)

3. Encouraging the people here to discover/use their gifts here

4. Building a strong sense of community within the congregation

The attenders again indicated the importance of the worship service, but it is also important for them that it should a significant part of the congregational ministry in the coming twelve months. The congregation and her leadership should reflect on the role of the worship service in nurturing their faith and foster spiritual growth (the second aspect in need of attention) as a strategy for the future.

The attenders value the worship service, preaching and the Holy Communion as the most important aspect of the congregational ministry, but they also indicate that it should receive more attention in the ministry of the congregation in the next twelve months. These empirical findings underline the importance of the voice of the congregation as part of preaching and worship. The empirical findings emphasise that the congregational voice as an important voice to be heard the preaching process.

3. Conclusion

Preaching is a dynamic process where the voice of God becomes audible through a dialogue between preacher, text and congregation and finally in dialogue with Him (Cilliers 2004:32). The voice of the congregation is an essential partner in this dialogue, and it helps to contextualize the sermon, but it is also a diverse theological voice due to the differences in the lived religion of the membership. This puts each sermon to a unique challenge. "The preaching, indeed, does not begin and end with the preaching moment, the congregation precedes and follows it up with an Amen!" (Cilliers 2004:133). The voice of the congregation from a theological and empirical perspective, is in the process of preaching, an important and significant voice to listen to.

References

Bruce, D. and Woolever, C. 2010. A Field Guide to Presbyterian Congregations. Kentucky: Research Services Presbyterian Church (U.S.A. [ Links ])

Campbell, C. L. and Cilliers, J.H. 2012. Preaching fools. The Gospel as a Rhetoric of Folly. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press. [ Links ]

Cilliers, J. 2004. The living voice of the gospel. Revisiting the basic principles of preaching. Stellenbosch: Sun Press. [ Links ]

Erwich, R. 2012. "Between ecclesiality and contextuality: Church Life Survey and the (re)vitalisation of Christian communities in the Netherlands", International journal for the Study of the Christian Church, 12(1):71-85. Doi: 10.1080/1474225X.2012.655020. [ Links ]

Farris, S. 2008. "Exegesis of the congregation, denomination", in Wilson, P.S. (ed.) The New Interpreter's Handbook of Preaching. Nashville: Abingdon Press. 266-267. [ Links ]

Hermans, C. and Schoeman, W.J. 2015. "Survey research in practical theology and congregational studies", Acta Theologica, Supplementum 22, 45-63.

Kaldor, P., Castle, K. and Dixon, P. 2002. Connections for life. Core qualities to foster in your church. Sydney: Openbook Publishers. [ Links ]

Long, T.G. 2001. Beyond the worship wars. Building vital and faithful worship. The Alban Institute.

Pepper, M., Sterland, S. and Powell, R. 2015. "Methodological overview of the study of well-being through the Australian National Church Life Survey." Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 18(1), pp. 8-19. Doi: 10.1080/13674676.2015.10 0 9717. [ Links ]

Powell, R. et al. 2012. Enriching church life. A guide to results from the National Church Life Surveys for local churches. 2nd edition. Australia: Mirrabooka Press & NCLS Research. [ Links ]

Schoeman, W.J. 2010. "The Congregational Life Survey in the Dutch Reformed Church: Identifying strong and weak connections", NGTT, 51(3&4):114-124. [ Links ]

Schoeman, W.J. 2015. "Identity and community in South African congregations", Acta Theologica, Supplementum 22, 103-123.

Sweet, L. 2012. Viral. How social networking is poised to ignite revival. Colorado Springs, Colorado: WaterBrook Multnomah Press. (Kindle edition). [ Links ]

Ward, P. 2017. Introducing practical theology. Mission, Ministry and the Life of the Church. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic. [ Links ]

1 See Hermans and Schoeman, 2015:60 for a discussion on the value of the attenders as a key informants on congregational life.

2 See Powell et al. 2012 for a discussion on the nine core qualities identified by NCLS.

3 The questionnaire enquires about a wide variety of the congregational life but the focus is here on the questions that relate to vital and nurturing worship as a core quality.

4 1 Alive and growing faith, 2 Vital and nurturing worship, 3 Strong and growing belonging, 4 Clear and owned vision, 5 Inspiring and empowering leadership, 6 Imaginative and flexible innovation, 7 Practical and diverse service, 8 Willing and effective faith-sharing, 9 Intentional and welcoming inclusion.

5 This question wasn't asked in the 2014 survey.

6 This is from a survey amongst DRC minister in 2006.