Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

On-line version ISSN 2413-9467

Print version ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.5 n.2 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.supp.2019.v5n2.a19

ARTICLES

The naked liturgist – Church without a building for people without a house

Mostert, Martin

Methodist Church, Cape Town, South Africa martinjohnmostert@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The concept of "public" (as used in the term "public worship) is interrogated in the light of Paul's understanding of nakedness/clothedness in 2 Corinthians 5:1-11. The conclusion drawn is that Christian liturgy is actually "private", and the resulting dissonance between precept and practice is untenable. A more appropriate approach to public-ness is developed with reference to John Wesley: liturgical events should and could intentionally be convened outside Christian premises - with the liturgists stripped of privilege. This is then illustrated by reference to field notes of an actual instance of such a "naked liturgy" that takes place weekly on the streets of Cape Town.

Keywords: Liturgy; homelessness; Wesley; preaching; nakedness

"Preaching fools have discerned that facing the crucified Other always involves facing others outside the gate. For the Other never comes without those others" (Campbell & Cilliers 2012:178).

"... the space that is opened up through the interaction between these four voices [preacher, text, congregation and Spirit] never becomes a fixed space constructed between stone walls. It is always in flux, liminal and transformative" (Cilliers 2016:65).

"... preaching fools may push an idea to its extreme so we can perceive its consequences" (Campbell & Cilliers 2012:196).

I want to persuade respectable ministers to spend a lot of their time preaching outdoors to people who would never enter their churches; which seems like a silly enough topic to honour such an exponent of foolishness!

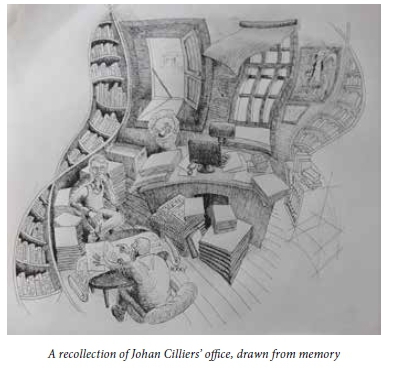

As an artist-puppeteer-theologian, I have an inerasable visual memory of Johan Cilliers' office. He shepherded me through a homiletics module of my MTh, and then patiently pastored me through perplexity and panic over the five years that it took me to complete my PhD. Let me draw you the picture ... piles of ring-bound papers, shelves of books, a sinister life-size clown-head sculpture fresh from some ghastly guillotine ... and, of late, a print of Picasso's disturbing Crucifixion, not in the least bit tamed by its prim frame. But of all the images that distracted my solemn search for academic probity, one stands out - one which Johan himself had painted: an interior view of an exterior scene, an open door with a handy stick, leading out into a hot Karoo landscape. Like a Pratchett Wizard he has now walked out through that door at last (Pratchett 1998:60-75). But by his counsel and intervention and encouragement, he has also set before me an "open door which no one can shut" . By who he is, what he does, and what he writes, this man has given me the broad freedom of a vista of aesthetic praxis.

Let us begin where that inscape/outscape begins, with the art of architecture. When Paul talks about "longing to be clothed with a heavenly dwelling"1 he references a peculiar sense of insufficiency; no fabric in this life - physical or material or psychological or ecclesial or socio-political -adequately covers us. Only what we will receive will finally secure us from the potential shame of nakedness. As we live this life, we live it in a tent, not a building.2 If life as a Christian involves inadequate tented housing, any street-dweller or refugee would know that we run the risk of uncomfortable exposure, whether by the theft of our cardboard, or by the intrusive beam of the policeman's torch.3 Such flimsy covering threatens our privacy and potentially allows others to observe, critique, expose, and abuse us, as Bernstein notes in the context of transparency and management (2017:3-4).4 My argument has two main points - firstly, as a contemporary church we have set ourselves up to avoid and eliminate as much of this visibility/ nakedness as possible; and secondly, that a missional calling to liturgical openness can be followed if we work against our inclination towards privacy under the tutelage of those who sleep on the streets.

1. Private (andfully clothed) public worship: What we do

We know in our theological bones that we should be open to scrutiny by the watching world (cf. Col 4:5; 1 Thess 4:12; 1 Tim 3:7). Perhaps that is why we call our Sunday liturgy "public" worship.5 However, what we actually do is to drive into electronically protected and security-guard-patrolled grounds, ascend stone steps, and pass through heavy doors into mysterious secrecy. This institutionalised private-publicness leads to important unintended consequences.

1.1 We disguise our real intentions

We perpetuate an institutional lie about what we are doing in worship: it is not "public"; it is "private". Strangers are welcome (or rather, "not unwelcome"), but they are not necessary to what we do. They are indeed allowed to witness our secret life, since "The liturgy is the activity in which the life and mission of the church are paradigmatically and centrally expressed" (Senn 1997:4). We might have an "open secret," as Newbigin would say (1978). But our "public" worship will generally continue without any sense of lack if there is no public present.6 In David Bosch's terms we are a lopsided ellipse, bobbling wildly on our centripetal spindle, with our centrifugal spindle not carrying any balancing tension (1991:385).

Just by not excluding attendance of the other-than-Christian, we are not necessarily creating a public liturgy7. We protect ourselves with our buildings, with door stewards and drop-safes for the collection, with the music we sing (and even the fact that we sing), with the culture of unchallengeable oratory, with our strange sacred book, with the rituals we celebrate, with the verbal and non-verbal shibboleths8 that expose and isolate any newcomer, and with the demographic profile of those who attend. Our micro-cultural doors are firmly closed to outsiders,9 a closure which sometimes amounts to hostile discrimination10.

From a cultural-anthropological viewpoint11 it is important to establish that it is not pathological to need and crave privacy and security; as Keifert points out, "... the stranger can and does do us harm" (1992:59 - emphasis added). Control of our personal space is a primal need, the basis of a sense of well-being.12 They used to sing about this around the campfire, how when Adam and Eve emerged into their dubious adulthood they hid from God and made themselves a leaf-camouflaged cover, and how God then subsequently clothed them with the durable privacy of animal skins (Gen 3:21). Humans apparently need to curate their accessibility, within the general confines of their culture, to tell a certain sort of story about themselves to others (Kraft 1996:157), to hide as much as we reveal. We should openly acknowledge our intention to seek private "Christian-time", since, as Bernstein argues, "The needs for transparency and for privacy are not mutually exclusive; rather, they are a pair of human necessities that need to be balanced" (2017:73).

Private liturgical rituals are therefore not somehow sub-Christian. As Keifert notes, "Human beings need to have some distance from close observation by others in order to feel safe enough to converse and interact" (1992:109). The Mask reveals (amongst other things) the true intention of the worshipper, and the appearance he/she decides to project.13 We also need to clothe our cosmic nudity, the frightening truth that we enter and leave this life naked (Job 1:21); Hughes would explain this as a need to delimit and defend our biospheres of meaningfulness (2003:68). Keifert says, "Ritual builds the social barriers necessary for effective interaction. It provides the sense of cover that allows most people to feel safe enough to participate in expressions of religious value" (1992:110). Private ritual is good for us.

1.2 We feel guilty about our need for privacy

And yet we are regularly - typically - berated for our closedness to others in Sunday sermons. This is unrealistic and counterproductive. The preacher might tell the flock to be Christ's representative in its community, but the flock does not intend to do so. There are hidden intentions at work. But such passive resistance cannot be held by Christians without internal discomfort. "Leave your comfort zone" (the classic cliche) is an instruction likely to engender a sense of anxiety and guilt, because as the Christian community we are deeply in favour of truth telling, since Jesus, our founder, was the archetypical opponent of hypocrisy (Mt 6:2, 16; 7:5; 15:7; 23:27-28): and here we are, loving our comfort and living a lie about our lifestyles. As a result, when I raise the subject of public liturgy, I often get either aggressive defensiveness or apologetic excuses as to why so very few are involved in meaningfully exposed ministry amongst those with the alternatively faith.14 The untold truth is, the church models defensive privacy, and we live our lives outside of church according to that same model.

So then, if we know that we should be open to the watching world, and if we falsely say that we are, whilst being closed to outsiders, and if we feel guilty about our privacy, whilst having no real intention of "deprivatising", then we seem to be stuck in a sorry cycle.

The establishment of intentional, "normal naked liturgy" might well break this impasse - through ordinary liturgical principles. Senn and other liturgists argue that liturgy encapsulates and communicates the entire cosmos of Christian meaning in itself, "a pattern of behaviour that expresses and forms a way of life consistent with the community's beliefs and values" (Senn 1997:3). So, naked liturgy merely requires an adjustment to the "pattern of behaviour" to include concrete liturgical connectivity between Christian and other-than-Christian. This would not involve liturgical innovation, but rather liturgical intentionality to the centrifugal pole of Bosch's conception of church (1991:385). At times - set times, in the same way that internal liturgy is celebrated at set times - the church would enact "normally naked" liturgy in spaces other than its sacred buildings, "expressing and forming" the value of openness-to-the-other in a concrete, unambiguous way.

But then, what would truly "public" or "naked" liturgy look like?

2. A framework for a "Naked liturgy": What we could do

As a Methodist theologian a key point of reference for me is John Wesley15, one of the foremost practitioners of "naked liturgy" in his day. What is particularly relevant is his praxis16, delineated most clearly in that unique (and largely disregarded) work, his journal (Mostert 2018b:50). His journal offers his life as an open book to be read by anybody who might care to look (1827-1: preface), and in it he quotes Saint Jerome's precept, "nudi nudum Christum"17 as something of a life-principle (Wesley, 1827-1, pp. 1736-0306). The pursuit of a spirituality that lacked guile, pretence, exaggeration, or manipulation consumed him (1827-1: 1738-03-02). We misinterpret Wesley if we do not grasp his passion for vulnerable openness and for "naked liturgy" that was its logical consequence.18

2.1 Wesley: Introspective legalism to public grace

A key moment in Wesley's ministry was his transition from rubric-bound privacy to serendipitous openness (Outler 1971:18-20), signalled by his taking up Whitefield's challenge to "field preaching" (Wesley, 1827-1, pp. 1739-04-02). This willingness to be vulnerable - to theological ridicule, eggs, vegetables, stones, and violent assault - became the hallmark of Wesleyan praxis. And it was exposure as a liturgist performing liturgy -Outler notes that "Wesley was quite unwilling to separate evangelism from liturgy" (1971:55). Openness meant being the church in the world of the outsider, exposed to their diseases and living conditions and deepest hungers. Traditional intuition assumes that the "proper sphere" of liturgy is the parish, consisting of "... a group of Christs' faithful, who are regularly brought together" (Ojemen, 2013, p. 50). John Wesley completely disrupted that settled reality with his challenging concept of the world being his parish (1827-1: 1739-06-11), intentionally echoing Jesus' "insane" openness-to-others (cf. Mark 3:20-25). As van Busskirk puts it, "Wesley's turn to the poor ... was not simply service of the poor, but ... life with the poor" (2012:5). But this element of praxis was already under threat during Wesley's lifetime - even newly converted Methodists quickly (instantly?) became reluctant to spend time outside of church buildings interacting with those who did not yet share their faith.19 It has long since ceased to be the hallmark of the Methodists.

2.2 A historical selection of Christian outsiders

All through history - and across all Christian traditions - some people have willingly embraced this vulnerability of Jesus. As Bonhoeffer noted, the crucifixion was not a result of a breach of Jesus' defences, but a consequence of his chosen path of defenceless vulnerability (1937/1963:95104); and Bonhoeffer was hanged, naked, just as Jesus was (Muggeridge, 2019). Francis of Assisi stripped himself of his inherited privilege and walk out naked into a public ministry of preaching and promoting the humanity of the poor (Schnieper 1981:63-65). Bunyan spent years in prison for unauthorised preaching, outdoors and indoors (Brock c.1870:xv-xviii). The early Methodists were viciously maligned by the established church for their way of publicly harping on about faith - the Canon of St. Paul's, writing in the early 1800s, called them "...nasty and noisome vermin" (cited in Rogers 1881:546). With similar exasperation, early Zulu Methodist preachers were nicknamed "nontlevu" (those who speak too much) (Etherington 1997:100) - but these talkative Christians communicated a choice for faith in Jesus (in public) to many who took it (Etherington 1997:99). At about the same time in 'sGravenhage, a retired Java missionary was recording his frustrations with the church's closedness to outsiders and the street preaching he was doing to reach them20. He experienced the churches to be ".... mostly as useless, unfriendly and rude as possible" (Esser 1886:1, my translation) and in effect "locked, as it were with seven locks" against outsiders (1886:1). Hoekendijk was another Nederlander who later would agitate to turn the church "inside out" (1964). And contemporary Africa is full of those who practice some or other form of "naked liturgy" - preaching, praying, singing and dancing on trains and busses and in streets.21 But these liturgists typically do liturgy, without giving academia the benefit of written theorising: much remains to be unlocked.

2.3 In search of a theory of privacy

This fragmentary survey highlights a strand of opposition to the practice of institutional privacy. However, it appears that, contrariwise, few privacy-exponents construct any theological defence of their position.22 The theory that supports the preference for private liturgy seems to be largely ad hoc and incoherent.23 The result is that the memory of "private church" seems to have been perpetuated in its private rituals: and the church does not remember the "forgottenness" of the outsider down the aeons (McClure 2001:44).

2.4 Dimensions of a theory of "Naked liturgy"

However, some contemporary theorists follow in the steps of earlier advocates for truly public liturgy; authors like Saunders and Campbell (2000) and John McClure (2001)24 in the United States, and some from Europe. Klomp & Hoondert report on a public contemporary passion festival that it had been ". a spatial practice that had turned the market square into . a holy place" (2012:220, my translation). Martin Stringer, writing from the streets of Birmingham, offers a definition of "public ritual" that corresponds to my idea of "naked liturgy": ". those rituals that a specific religious, or other, community chooses to perform in public, that is [sic] beyond the confines of their own building or compound, and more specifically to perform with the intention of attracting an audience beyond their own particular community" (2015:45)

Stringer (a liturgist-anthropologist) describes these rituals as ". complex, multi-valent and often creative activities" (2015:47). For them to constitute valid Christian liturgy in Hughes' terms they would need to have elements such as an opening rite, the service of the Word, a sacramental rite and a sending rite (2003:168; cf. Cilliers 2016:41, footnote 44), analogous to institutionalised Christian "home liturgy". John Wesley's Journal illustrates this repeatedly "About eight I went down to a convenient spot on the beach and began giving out a hymn. A woman and two little children joined us immediately. Before the hymn was ended, we had a tolerable congregation..." (1827-4: 1787-0816). "[T]he Downs I found, but no congregation, - neither man, woman, nor child. But by that I had put on my gown and cassock (sic), about a hundred gathered themselves together, whom I earnestly called "to repent and believe the Gospel"" (1827-1: 1743-09-09). Naked Liturgy is normal liturgy - except that the liturgist has shed her/his building, and with it a large portion of her/his privilege and power.

In my view it was a critical fault of Wesley's that he was not able to articulate a clear theological rationale for field preaching,25 and that he did not structurally incorporate field-preaching into the shape of Christian discipleship, as he did with small-group accountability. Perhaps as a result, people tend to disregard Wesley's spatial choices. But they are very significant for formulating truly public contemporary liturgy.

3. Naked liturgy in action: How we might do it - among the houseless in Claremont (Cape Town)

3.1 Historical privacy of a Methodist Church

My church has always been respectably cloaked with lockable gates in formidably spiked iron railings, steep granite stairs, heavy oaken doors with chunky iron rivets, and a narrow, defensible narthex leading into a dim interior, where a minister, speaking from the crenelations of a ceremonial castle, was presided over by the twelve apostles of the hammer beams. Rowdy children were ejected. The only serious challenge to the sacred hush was the occasional invasion by houseless persons, who seemed to treat this building as if it was as open to them as the public library. I was deeply impressed.

3.2 The houseless as a prophetic sign

Over the decades the houseless have constituted an ongoing prophetic challenge to the ecclesial fable of our "public worship"26. A small section of the Church community has been actively hostile towards such persons, but others have defended their right to enter. Over the years a few have even taken the contact further, notably under the leadership of the late Mary Bryant, envisioning and establishing a night shelter (still in existence), and a daily soup kitchen and skills development centre (sadly now defunct). She modelled what Kosuke Koyama would later spell out for me, that "... our sense of the presence of God will be distorted if we fail to see God's reality in terms of our neighbour's reality" (1974:91).

3.3 When you give a feast ...

The current state of play - and learning - is this: we have a cadre of members who serve a monthly "community meal" shared by those who are "housed" members of the church and those who are members of the wider Claremont "houseless"27 community. In my mind the theological basis for this is crystallised in one of Jesus "when you" commands - "when you give a feast, do not only invite those who might invite you back" (Lk 14:13). The hosts serve a good28 free meal, once a month before the Sunday evening worship service. The objective is simply to have a celebratory meal together. No pressure is put on people to attend the service afterwards, and most of the 70 to 80 people do not.

This initiative has generated several different reactions amongst the housed part of our congregation. The majority decline to join this aspect of community. About twelve housed church members are involved in the cooking, serving and cleaning, along with a few of the houseless. Some housed members eat and talk with the incomers. One member has started a follow-up Wednesday evening "pavement chapel" in an area where many of the Sunday night gathering sleep.

3.4 Pavement chapel: Case study of "naked liturgy"

I am that church member. As part of my post-doctoral lifestyle I am convening some approximation of "naked liturgy" on the streets. Susan Willhauk shows that "the street" "...is not a monolithic culture" (2013:94; McClure 2001:48); accordingly, I am there to learn what I can from the particular people I meet whilst performing public liturgy (Mostert 2018a).

I am there by invitation. A street dweller once complained to me how some Christians turn up with a boot-load of sandwiches, and then preach a gospel of "getting off the streets". As a deeply convinced and converted Christian, she was indignant - she could afford a room, but only in dangerous Hanover Park. It was actually safer to sleep outside Claremont Police Station.29 That conversation, and several other invitations, prompted me to begin praying and painting there.

This turns out to be a topsy-turvy sort of undertaking in every way. I would have assumed that the houseless would have been consumed with issues of food and shelter, but it turns out these houseless people have those concerns covered (they have a weekly/monthly schedule of church-based meals and soup kitchens: they know where to get food every day). But what they did turn out to want was human recognition, prayer and metaphysical conversation.

The "order of service" (as we Methodists call our liturgy) is rearranged/ deranged. It flows out of the shared meal in sacred premises. Then comes a general dispersal, after which I enjoy the hospitality of the houseless in reverse. This experience is deeply liminal: the shops have closed their doors, and their doorways become the shelter of the houseless. I cross an invisible threshold to enter their doorway-world. All those who wish to attend coalesce around the emerging painting of a parable30; without inviting or calling or cajoling anyone. I simply sit and paint. People come and ask questions, or just sit and watch and listen. I tell the story, which forms the basis of an interaction around the Word of God, where two or three interpret (1 Corinthians 14:27 perhaps), and the Word is applied to every person. People suggest colours and elements to include in the painting, and joke about who is represented by which character. I pray for any who want prayer, and sometimes ask for prayer for myself. And then I process on foot through an imaginary narthex, walking to my house a kilometre away. The "oddness" of this inside-outsideness is well described in poetic terms by Cilliers: "in the liminal space",31 he says, "one experiences both the fullness and emptiness of presence and absence" (2008:81).

3.5 Reflection on pavement chapel as naked liturgy

It might be easy to dismiss this little enterprise as a sentimental gesture. But I offer it as an example of "foolish, disruptive preaching" (Campbell & Cilliers 2012:153) and truly public liturgy, a snapshot of "a strange unsettling land beyond the comforts afforded by patriarchy, capital, media, 'the system' and the private realm" (McClure 2001:134).

The houseless, I have found, are often fiercely independent and adamantly unique: they desire neither houses nor kitchens, jobs nor salaries; their social structure is extremely loose - an intriguing mixture of competitiveness and cooperation. But it seems from my observation that they share a common desire for respect, which takes varied forms: for some it means being left alone; others want a listening ear; for others it entails an opportunity to reflect on the meaning of the Gospel alongside the meaningfulness of their lives. The naked liturgy of Pavement Chapel can respectfully exist in the world of the houseless at all those levels. People are glad to receive the gift of the Church, the place where Jesus is mediated by the gathering of two or three in his name (Matthew 18:20; Volf 1998:136).32 This is liturgy where the stranger is completely necessary.

With regard to the preacher, these "other bodies" helpfully deconstruct the role and function of the preacher, through an ".encounter with the infinity of others for which no totality can take account" (McClure 2001:66). There is no pulpit-protection: anybody can interrupt. An artist can even lose control of his brush - a surprisingly poignant loss! The preacher is not in control of interpretation, either: the houseless come to sit at McClure's "table of exegesis" (2001:101).33 Somebody who has heard the story joins in telling it to yet another, in a sort of democratic kerygma. The pavement becomes a real place to exit to from the houses of scripture, tradition, experience and reason, in McClure's formulation (2001).

In a context where ". denominations and churches are contented with the comfortable homiletic world of emotional and sentimental reflection on purely subjective values" (McClure 2001:131), the pavement chapel serves as a salutary intersection of the closed world of the church with an-other world. Firstly, the houseless physically and emotionally disrupt the sense of security and religion of the housed. They illustrate the truth that buildings are transitory, and our power of control is limited. Secondly, housed Christians have much to learn from them, new vistas for kindness and respect of the Other in every avenue of life. Thirdly, naked liturgy gives actual content to the concept of "the world": real smells; real tastes; real feelings; real sounds; and real faces. Where else would a wealthy Christian with a status car learn to feel embarrassed about their vehicle? Where else would the housed learn the importance of having more publicly accessible toilets? Where else would the issue of justice for the psychiatrically challenged become a normal concern of the church? If liturgy is there to school us into the values of the Christian faith, as Senn suggests, then it has to be at least partially situated outside of our usual buildings; as Saunders and Campbell argue, "...where we learn shapes what we learn, and where we read shapes how we read" (2000:89).

4. Naked liturgy is possible

I would like to make this one point: it is possible and necessary in the twenty-first century to have a gentle, respectful, Gospel-filled liturgy that is truly public; i.e. in the open, outside Christian spaces. Just as John Wesley realised that "outdoors-ness" was a hallmark of Jesus' ministry in the Gospel records,34 so too, with a little imagination, it seems that it would be possible to replicate that "nakedness" in almost any urban setting in the world. This case study of a public liturgy amongst the houseless is only a fingerpost to a multiplicity of such "other-wise" liturgical possibilities (McClure 2001:xi).

Practicing naked liturgy offers liturgy as a "means of grace" as Wesley envisioned it (Wesley 1787, sermon 16), a place where God meets with people and satisfies their deepest needs, outside buildings. Naked liturgy deliberately gives away the church's costliest treasures for free. It is the reckless raiding of Francis' father's cloth-store to richly clothe the poor in the finest silks. It establishes a normal space for the church to be careless about itself and gleefully inappropriate with its most sacred elements.35 And perhaps as we experience the Spirit of God hovering over the chaos of the street and bringing forth wonders through public liturgy, our appreciation of the God of Wonders in our private, inside liturgy might grow stronger.

Persuading business-as-usual liturgists to expand their concept of liturgy to include liturgy on the streets as a new/renewed "normal" element for churches takes up a lot of my time. Through foolish preaching, idiotic painting, and silly puppetry, I try to set before the churches the vista of their own their own inside/outside, front/back doors, and show them the landscape onto which those doors open . trusting that no one will close their eyes to that burning vision of the world beyond, inhabited by the dangerous-gracious Other, that so dominates the imagination of Johan Cilliers.

Works cited

Bernstein, E., 2017. Making Transparency Transparent: The Evolution of Observation in Management Theory. Boston: Harvard Business School. [ Links ]

Blythe, S., 2018. Open Air Preaching: a Long and Diverse Tradition. Perichoresis, 16(1):61-80. [ Links ]

Bonhoeffer, D., 1937/1963. The Cost of Discipleship. New York: MacMillan. [ Links ]

Bosch, D., 1991. Transforming Mission - Paradigm Shifts in the Theology of Mission. Maryknoll, USA: Orbis. [ Links ]

Brock, W., c.1870. Life of Bunyan. In: The Pilgrim's Progress and The Holy War. London: Cassell Petter & Galpin, pp. iii-xxxiv. [ Links ]

Campbell, 2010. "Preacher as Ridiculous Person: Naked Street Preaching and Homiletical Foolishness. In: R. Reid, ed. Slow of Speech and Unclean Lips: Contemporary Images of Preaching Identity. Oregon: Cascade, pp. 89-108. [ Links ]

Campbell, C. & Cilliers, J., 2012. Preaching Fools - the Gospel as a Rhetoric of Folly. Waco: Baylor University Press. [ Links ]

Cilliers, J., 2008. Worshipping in the Townships - a Case Study for Liminal Liturgy. Journal of Theology for Southern Africa, Volume 132, pp. 72-85. [ Links ]

Cilliers, J., 2016. A Space for Grace - Towards an Aesthetics of Preaching. Stellenbosch: Sun Press. [ Links ]

Clarke, W. & Harris, C., 1950. Liturgy and Worship - a Companion to the Prayer Books of the Anglican Communion. London: SPCK. [ Links ]

Dueck, A. & Reimer, K., 2009. A Peaceable Psychology - Christian Therapy in a World of Many Cultures. Grand Rapids: Brazos. [ Links ]

Esser, J., 1886. Straatprediking - Nagelatene Bladzijden uit Zijnen Evangelie-Arbeid. Nijmegen: P.J. Milborn. [ Links ]

Etherington, N., 1997. Kingdoms of this World and the Next: Christian Beginnings among Zulu and Swazi. In: R. Elphick & R. Davenport, eds. Christianity in South Africa - a Political, Social & Cultural History. Cape Town: David Philip. pp. 89-106. [ Links ]

Freire, P., 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. St. Ives: Penguin. [ Links ]

Harris, M., 2005. The New International Greek Testament Commentary -The Second Epistle to the Corinthians. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Hoekendijk, J., 1964. De Kerk Binnenste Buiten. Amsterdam: W. ten Have. [ Links ]

Hughes, G., 2003. Worship as Meaning - a Liturgical Theology for Late Modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Jerome, 1892. The Principal Works of Jerome. New York: Christian Literature Publishing. [ Links ]

Keifert, P., 1992. Welcoming the Stranger - a Public Theology of Worship & Evangelism. Minneapolis: Fortress. [ Links ]

Klomp, M. & Hoondert, M., 2012. "De Straten van Gouda zijn ons Jeruzalem" - een Populaire Passie op het Marktplein. Jaarbooek Voor Liturgie-onderzoek, Volume 28, pp. 207-221. [ Links ]

Koyama, K., 1974. Waterbuffalo Theology. London: SCM. [ Links ]

Kraft, C., 1996. Anthropology for Christian Witness. Maryknoll: Orbis. [ Links ]

Letsosa, R., 2008. The Healing Power of Worship in a Liturgically Deprived African Community in South Africa. Praktiese Teologie in Suid-Afrika, 23(2):85-102. [ Links ]

Martin, S., 2011. Christianity and the Transformation of Tradition in South Africa. Journal of Theology for Southern Africa, Volume 139, pp. 2-6. [ Links ]

Mbiti, J., 1986. Bible and Theology in African Christianity. Nairobi: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

McClure, J., 2001. Other-wise Preaching - a Postmodern Ethic for Homiletics. St. Louis: Chalice Press. [ Links ]

Mostert, M., 2018 b. Wesley's Journal: Missing Element in the Formation of Methodist Clergy?. Grace & Truth, 35(1):47-58. [ Links ]

Mostert, M., 2018a. The Liturgy of Conversion: Evangelism Praxis in the Methodist Churches of Cape Town (Unpublished PhD thesis). s.l.:Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Muggeridge, M., 2019. A Man of Conscience - Dietrich Bonhoeffer. [Online] Available at: https://www.plough.com/en/topics/faith/witness/dietrich-bonhoeffer-man-of-conscience [Accessed 26 05 2019].

Newbigin, L., 1978. The Open Secret - an Introduction to the Theology of Mission. 2 ed. Michigan: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Ojemen, C. A., 2013. The Parish as the Primary Place for the Mission of the Church in Africa. African Ecclesial Review, 55(1):47-76. [ Links ]

Okonkwo, I., 2010. The Sacrament of the Eucharist (as Koinonia) and African Sense of Communalism: Towards a Synthesis. journal of Theology for Southern Africa, Volume 137, pp. 88-103. [ Links ]

Okumu-Bigambo, W., 2006. Selective Communication: Innovation and Performance for the Church in Africa. African Ecclesial Review, 48(4):267-288. [ Links ]

Outler, A., 1971. Evangelism in the Wesleyan Spirit. Nashville: Tidings. [ Links ]

Pratchett, T., 1998. The Last Continent. Corgi, 1999 ed. London: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Reynolds, E., 2013. "Away from the Body and at Home with the Lord" - 2 Corinthians 5:1-10 in Context. Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 24/2 (2013):137-152, Volume 24(2):137-152. [ Links ]

Rogers, J., 1881. The Church Systems of England in the Nineteenth Century. London: Hodder & Stoughton. [ Links ]

Saunders, S. & Campbell, C., 2000. The Word on the Street: Performing Scriptures in the Urban Context. Eugene: Wipf & Stock. [ Links ]

Saunders, S. & Campbell, C., 2000. The Word on the Street: Performing Scriptures in the Urban Context. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Schnieper, X., 1981. Saint Francis of Assisi. London: Frederick Muller. [ Links ]

Senn, F., 1997. Christian Liturgy - Catholic & Evangelical. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Snyman, G., 2015. Responding to the Decolonial Turn: Epistemic Vulnerability. Missionalia, 43(3):266 - 291. [ Links ]

Stringer, M., 2015. The Future of Public Religious Ritual in an Urban Context. Jaarboek voor Liturgieonderzoek, Volume 31, pp. 45-59. [ Links ]

Turnbull, G., 2011. Trauma: From Lockerbie to 7/7: How Trauma Affects our Minds and How We Fight Back. London: Bantam. [ Links ]

van Beek, W., 2011. Ritueel als Arena: Dogon-maskers en hun Strijd. Jaarboek voor Liturgie-onderzoek, Volume 27, pp. 223-241. [ Links ]

van Braak, J., 2016. Hosting Transcendence in Immanence - a Postmodern Theological Construction of a Dialogue between Site-specific Contemporary Visual Art and a Monumental Church Building. Jaarboek voor Liturgieonderzoek, Volume 32, pp. 41-66. [ Links ]

van Buskirk, G., 2012. John Wesley's Practical Eschatology. Boston: s.n.

Volf, M., 1998. After Our Likeness: The Church as the Image of the Trinity. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Walker, A. C., 2012. Practical Theology for the Privileged: a Starting Point for Pedagogies of Conversion. The Journal of Theology for Southern Africa, 16(2):243-259. [ Links ]

Wepener, C., 2011. Liminality: Recent Avatars of this Notion in a South African Context. Jaarboek voor Liturgie-onderzoek, Volume 27, pp. 189-208. [ Links ]

Wesley, J., 1787. Sermons on Several Occasions (44 Sermons). 1944 ed. London: Epworth Press. [ Links ]

Wesley, J., 1827-1. The Journal of the Rev. John Wesley A.M. Volume 1. 1922 ed. London: J.M.Dent. [ Links ]

1 2 Corinthians 5:1-11. Edwin Reynolds gives a good summary of ancient and recent interpretations of this passage. He comes to the conclusion that "although the passage is not primarily about either anthropology or eschatology, it does lend insight into both anthropology and eschatology" (2013, p. 151) - and anthropology is an underlying interest of mine in this paper.

2 The 'επιγειος ο'ικια του σκηνους (2 Cor 5:1; cf. Harris 2005:370) is destructible, causes us groaning, and is a burden, and somehow exposes us to the threat of naked shame - for Paul our current state of being is not one of honour, permanence and security (5:1-5). One aspect of this concept of painful openness is evocatively expounded by Gerrie Snyman as he develops a "hermeneutic of vulnerability" for the perpetrators of colonialisation as they emerge into post-colonial realities (2015:279-287) - and before you read further you must consider whether or not I (as a former SADF conscript soldier under apartheid) have your permission to speak. I do not take it for granted.

3 Harris points out that the "groaning" expresses for Christians "their profound dissatisfaction or frustration with the limits and disabilities of bodily existence on earth when compared to the glories of the new age" (2005, p. 388). Elsewhere Paul refers to "nakedness" as one of the hardships he has had to face (Romans 8:35; 2 Corinthians 11:27).

4 I discover - deep into my research - that Campbell has beaten me to the punch with his article "The Preacher as Ridiculous Person: Naked Street Preaching and Homiletical Foolishness" (2010). I envisage more than just preaching, but then, so does he.

5 In their classic work on liturgy, Clarke and Harris do not ever consider the topic of why the liturgy is referred to as "public" (1950:29-37); they assume that the only two parties are the Christian Community and God. Mbiti likewise defines liturgy as ""the worshipping expression of the people of God" (1986, p. 92). Keifert makes some headway towards a theory of openness - he at least acknowledges the right of the stranger to make herself present (1992:93). I have argued elsewhere against the conceptual exclusion of the Outsider from the consciousness of the Liturgist (Mostert, 2018a:34-35).

6 Senn never deals specifically with the presence of the "other-than-Christian" even though he refers to the "effective communication of the gospel and edification of the fellowship in the gospel" (1997:44) in his Christian Liturgy - Catholic and Evangelical. He has a strange myopia about the state of the faiths of the world outside Christian circles.

7 Stephen Martin does an excellent job of interrogating the concept of "public" in his editorial for the 2011 JTSA (2011:2-6).

8 The reference is to Judges 12:6; have you noticed, for instance, the strange Protestant "click" used in prayer?

9 These tendencies are not only the cultural tendency of Westernised congregations. In the Xhosa incarnation of Methodism, a door steward, "the man who closes the door and guards it during prayer", is a thing. And Okonkwo observes that there is a tendency even amongst African Christians to "exhibit an exclusive communalism that most often favours a selected few" (2010:103)

10 Wilphredian Okumu-Bigambo observes that "Whereas Jesus chose to go to both believers and non-believers, the rich and poor, some pastoral agents these days discriminatively dispense their spiritual services..." (2006:281).

11 Senn helpfully notes that "Liturgy is a human activity, and its execution can be evaluated by helpful recourse to anthropological research, ritual studies, communication theory, and other behavioural sciences" (1997:43).

12 Gordon Turnbull isolates the restoration of "a sense of control" (how much they reveal/conceal) as key to the recovery of hostage victims and other sufferers of PTSD (2011:254).

13 Wouter van Beek has written a very helpful article on the way masks feature in Dogon death rituals to both hide and represent (2011). He shows how the Dogon masks represent spiritual realities to the Dogon themselves, whilst hiding securely from the gaze of outsiders - in this case, tourists.

14 I describe the hostility and defensiveness towards the idea of intentional public liturgy in Mostert, 2018a:144.

15 I examine the imperatives and dangers of referencing Wesley's thought in contemporary praxis in an article published in Grace & Truth (Mostert 2018b)

16 Freire 1970:106; McClure 2001:98.

17 (Jerome 1892:486) "nakedly follow the naked Christ". Wesley quotes Jerome in reflection on his first sermon in America (Journal 1736-03-07); he later quotes a letter (in approval) in which the same sentiment is expressed (Journal, 1739-11-1). His search for communicable godliness led to Wesley de-emphasizing even his beloved Early Church Fathers (including Jerome) in pursuit of his vision of a stripped-down simplicity of interactive obedience.

18 Wesley describes this turn-to-the-outsider: "I could scarce reconcile myself at first to this strange way of preaching in the fields, ...; having been all my life (till very lately) so tenacious of every point relating to decency and order, that I should have thought the saving of souls almost a sin, if it had not been done in a church" (1827-1: 1739-03-31).

19 Wesley frequently had to defend field preaching: "The want of field preaching has been one cause of deadness here. I do not find any great increase of the work of God without it. If ever this is laid aside, I expect the whole work will gradually die away" (1827-1: 1763-09-24).

20 One reason street preachers have not been treated with the academic attention they deserve is perhaps that they are and have been men and women (and children) so busy with the oral aspect of their communication that they have neglected the written side of recording their experiences. Stuart Blythe recently did research into street preaching for his PhD and found that "[o]pen-air preaching ... is not simply a practice which is neglected in academic study but which is often treated with some suspicion" (2018:63)

21 Against this Prof Letsosa argues that black communities are "liturgically deprived" (2008:86), and should be encouraged to "remove the fear" felt by people who practice ancient birth and death rituals alongside Christian liturgy (2008:87). But he seems to deal with the Western-dominated liturgy ("cultural garment" - 2008:90) that is limited to Christian spaces (2008:99). I agree that there must be more to liturgy than that!

22 This makes it difficult for me to establish a proper scholarly argument for a radically public liturgy; no Christian academic actually publishes a contrarian view.

23 My research has shown that the two reasons for privacy most commonly advanced by Methodist ministers are a radical respect for the privacy and autonomy of others, and an aversion to judging them (Mostert 2018a:144-148).

24 Although McClure, frustratingly, only envisions actual preaching happening from a pulpit on a Sunday Morning in a Church building (2001:30,51,148,151,152), with only passing allusion to outside preaching (2001:134,146).

25 None of his sermons cover the spatial theology of field preaching, and its relationship to preaching in church buildings.

26 My favourite memory is of one houseless man staggering down the aisle from side to side, and bursting into loud tears when he realised, I was preaching on John 3:16 (It must have been the second Sunday in Lent of year A, or the fourth Sunday in Lent or Trinity Sunday of year B of the Revised Common Lectionary.)

27 The eulogies at the funeral of a houseless woman in Kalk Bay taught me that a person without a house is not necessarily a person without a home. This woman was memorialised by her fellow street dwellers for never having allowed arrests by the police or efforts by social workers to move her off "her spot". She always came back; she always defended her home.

28 So good that some of the houseless come from Simonstown, 36 km away, and have to rush off to catch the final train home.

29 Bearing in mind Enriquez' proposed indigenous research methodology of Pakikipagkuwentuban - reliance on storytelling and informal conversations (Dueck & Reimer 2009:196), I have made informal notes, questions and observations from which I draw insights.

30 Which establishes a first-space-fourth-space continuum, following Cilliers' thought (2016:10-12). Van Braak notes that "In attempting to discern divine presence in everyday reality, I call to mind that the connection between art, dialogue and religion is their capacity to disclose our embodiment in the visible and everyday reality" (2016:65). She was dealing with art displayed in a cathedral; I had to once dispose of a decomposing rat - we both feel very embedded in first-space!

31 Cas Wepener delivers a bracing call to move through liminality to a new identity, forged in action-after-learning (2011:208); I agree in principle, but at the moment I am still loitering with the loiterers on the threshold, and am involved in learning-in-action.

32 It is important to note here that the houseless are frequently devout Christians.

33 A street dweller can place himself in the place of the longing father in the parable, heartsore over the theft of pension money by a son needing to buy drugs - I would never have thought of drawing that parallel!

34 Wesley launched into his Field Preaching career on the back of an insight into the Sermon on the Mount being "... one pretty remarkable precedent of field-preaching" (1827-1, p. April 1 1739)

35 I am not "empowered" by the Methodist Church to give out communion - otherwise I would normally (and deeply reverently) administer this sacrament on the pavement. If liturgy is public, then everything is public.