Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

On-line version ISSN 2413-9467

Print version ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.5 n.2 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.supp.2019.v5n2.a15

ARTICLES

Preaching as "Commercialised Pavement Spirituality". Towards a Streetwise Ecclesiology of "Spaza Faith" (mens-kerk)

Louw, Daniël

North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa dil@sun.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The Africanisation of Christianity is indeed a challenging endeavour. It is difficult to pin point what is exactly meant by an African version of the Christian faith. Many attempts to make Christianity "indigenous" are merely a European version with an African flavour. The article probes into the informal life settings of township spirituality. Unemployment and poverty demarcate the structural conditions of township life. The phenomenon of spaza entrepreneurship is investigated, specifically how naming of informal street businesses, often reflects a kind of internalised Christian spirituality. Spaza is the Zulu word for camouflage. With "spaza" piety is meant: Faith in Cognito; faith operating within the disguise of faithful businesses where poor and unemployed people try to survive the hardships of poverty and unemployment. "Spaza spirituality" is rendered as a kind of streetwise "sermon". At stake within the discipline of homiletics is the following questions: When the context becomes the text, what is meant by "contextual preaching" within township life? Can the Christian faith indeed beautify township life so that practical theology implies more than ethical endeavours but includes an aesthetic ecclesiology: Fides quaerens beatitudinem (faith seeking the beautification of life).

Keywords: Practical theology as fides quaerens beatitudinem; spaza spirituality; informal streetwise wisdom; township life; informal ecclesiology of faithful life

1. Introduction

I want to honour Johan Cilliers' contribution to the discipline of practical Theology at the faculty of Theology, University of Stellenbosch by acknowledging his attempts to promote homiletics as an aesthetics endeavour within homiletic modes of sheer "foolishness": Preaching Fools. The Gospel as a Rhetoric of Folly (2012). Yes, it could be indeed an existential fact that to preach at the streets of poor townships, with the message that God is good and beautiful, seems to be ridiculous foolishness; sheer folly! But, perhaps, cognitive foolishness could become in fact a mode of streetwise spirituality and township wisdom.

In 2008 Cilliers published an article with the title: "Worshipping in the Townships", pointing out that township life introduces the preacher to the challenge of liminal liturgy. His aesthetic vision was to promote the liturgical dance of life with a "beautified Deity" despite the paradox of ugliness (see Cilliers 2012: Dancing with Deity. Re-Imagining the Beauty of Worship).

To my mind, Johan Cilliers' legacy to the science and discipline of homiletics can be captured by the following theses: Preaching is the art of playful enjoyment; it is about the celebration of gratitude within the liturgy of life; the human being as homo ludens playing the joyful tune of grace within the existential rhythm of life, often with a smile, knowing that "gossiping the gospel" is a kind of streetwise piety (festivity) challenged by irony, comedy and painful paradoxes - "a feast of fools" (Cox 1969). Thus, the reason why the preacher's seriousness is disguised in the foolishness of the gospel; the preacher as a pious fool. In fact, the gathering of the congregation and their sheer foolish innocence and visionary blindness, without any imagination (fides quaerens imaginem) is the reason for many denominational and synodal stupidities.1

To think outside the boundaries of official prescriptions, is the miracle of preaching; i.e. to imagine the unseen realm of life. Thus, Johan's persistent homiletic endeavour to beautify life (fides quaerens beatitudinem).2

The beautification of life is indeed a very challenging endeavour in practical theology. However, when one probe into the critical area of public life in Southern Africa, very specifically township life and the threat of poverty and unemployment, how is it possible to beautify life when desperate people try to survive on the streets of informal settlements in Africa? Is beautification not a luxury while ethical issues like crime, corruption and gangsterism dictate the informal scenario?

With reference to his book: A Space for Grace (Cilliers 2016), it is indeed a burning question what is meant by an "aesthetics of preaching" when the space is ugly. How on earth can the barren space of township life become beautiful?

In fact, the real challenge to "dance with Deity" is not in the cathedrals of glass stained spaces filled with wealthy congregants, but in the informal structures of dirty pavements where people strive to survive. Thus, the focus of the article on the informal sector within the townships of Africa, embedded in the burgeoning microenterprise of informal undertakings; activities that can be rendered as "hidden", a kind of subterranean economy within what I want to call a "spaza mentality" as mode of surving extreme living conditions.

Can township life under worse conditions become a place and space for fides quaerens beatitudinem: faith seeking beauty (the beautification of life)?

Christina Landman (2009:2), in her research on "township spirituality", very aptly points out: In the townships, religion has been reclaimed by people in search of the healing of their bodies and circumstances. This has given birth to religious discourses on healing which are unique to these areas, and largely foreign to the "outside world". In this sense, "spaza spirituality" could be seen as the unique outcome of the interplay between unemployment, poverty, economic survival and the disposition of people that integrated their religious understanding of faith (belief system) with their immediate living conditions. In many parts of Africa and in poor rural areas, one will find small shops, even shacks, embroidered with concepts derived from the Christian faith tradition like: Grace, goodness and even beauty. The concepts then refer to a kind of healing of life.3 When one is really engaged in township spiritualities, one can concur and say that in township spiritualities, Africa has taken Christianity back from the West (Landman 2009:272). That is then more or less what the notion of "spaza spirituality" implies.

In general, spirituality is understood as the attempt to link the human quest for meaning to values, virtues, life views, religious traditions and the transcendent realm of God-images, to daily existential conditions that determine the quality of life. AS Geri Miller (2003:6) pointed out: Spirituality is that tendency which moves people toward knowledge, love, meaning, peace, hope, transcendence, connectedness, compassion, wellness, a value system and wholeness in such a way that their immediate environment is affected and even transformed.

In the light of the previous introduction and exposition, the following research question: Can a plaza spirituality beautify the ugliness of poor people within the informal spaces of township life?

2. Preaching merely an official event for ordained clergy?

In the tradition of many mainline churches, "preaching" has been the prerogative of clergy. Preaching was the task of ordained ministers, exclusively reserved for "special offices". Lay people could minister only on a non-official basis and was labelled as "informal".

In the North-Western part of South Africa, and in many rural areas of the Karoo, a sermon delivered by an elder was possible only as a "reading lesson" (leesdiens); mostly sermons designed and written by ministers and published in special editions for formal sermons (preekbundels). A sermon delivered by lay people was called a "man-service" (mens-kerk); it was unofficial and rendered as being informal and of less value and official status. One does not listen to uneducated people because they will harm the official confessions of the church, running the danger of "theological blasphemy".

Ecclesiology was framed by ecclesial structures, dogmatic formulations, denominational convictions and confessional formulations that opted as prescriptive regulations for piety. Denominational confessions were about "pure truth", therefore the task of church councils to defend the pulpit against unbiblical teaching (fallacy). Any secular or worldly or unbiblical teaching should be abolished. Other religious perspectives or spiritual practices were rendered as dangerous running the risk of making the gospel a cultural and human enterprise. In my theological education at faculty we coined in Missiology a technical term for the infiltration of pure faith by daily existential modes of living, cultural traditions and secular thinking, namely the threat of syncretism.

But, if the context become the text for the sermon of life, does such a transition necessarily implies dogmatic fallacy and syncretistic derailment?

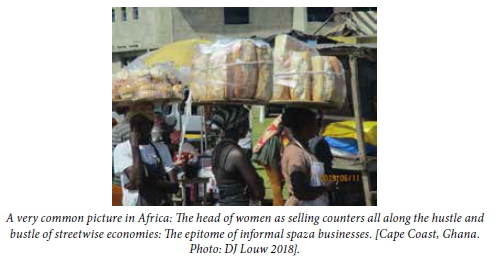

The past fifteen years I had the opportunity to start, together with the faculty of theology at Pietermaritzburg, several M.Th courses in Clinical Pastoral Care, HIV & AIDS, all along the Eastern coast of Africa. Exposed to many townships and rural areas in Africa (Uganda, Kenia, Tanzania), I became aware of a totally different understanding of being the church. All over Africa one will find informal structures on pavements or beside busy, damaged streets, where poor people set up informal trades, trying to sell products. It could be for example a small grocery store. Often it is a woman selling only matches or pots for cooking utensils.

The fascinating aspect is that this kind of informal business is often connected to names and concepts stemming from the Bible and the Christian faith. For example: My God is Beautiful Hair Salon.

The point is, lived religion and Christian piety became the neighbourhood, and cathedrals, merely mud structures within informal townships. Within the informal sector of life, Christianity is shaped by the infiltration of daily attempts to survive. Poor people must face the battle of poverty despite unemployment.

I was fascinated by this kind of streetwise, commercialised piety and started to wonder what kind of Christian spirituality lurks in these names. Or are the Christian names merely a kind of secularised faith manipulating God into a prosperity cult of the poor and unemployed people, hoping that their faith will help them to survive the pain and suffering of poverty?

And now the burning homiletical question: What happens when the text for preaching becomes the business of a poor widow trying to earn money in order to buy bread for her children? When the sermon is merely a wooden structure on the pavement? When the church is a pavement business and attempt to survive, living on the brim of the so-called "bread line"? When liturgy has become an attempt to link the "goodness of God" to an "ecclesiology of spaza faith"? When the text and the sermon is a waiter sharing his lunch with a handicapped person in his wheelchair on the pavement?

3. The African scenario

There are indeed many kinds of spiritualities unfolding all through Africa. Africa itself became for me a kaleidoscope of surprising landscapes. I was overwhelmed by diversity and the practical theological challenge how to contextualise Christian piety and faith. Piety is not anymore, a sophisticated choice prescribed by official confessions, but an existential mode of living; a disposition demonstrating the passio Dei.

I have always struggled with the Africanisation of practical theology within an African context. I even devoted a whole chapter to this topic in my book: Cura Vitae. Illness and the Healing of Life (2008:146-192). Although very difficult to merge the different perspectives, it seems that in the more non-analytical thinking of African people, their approach is much more community oriented and inclusive than individual with the focus on private needs.

In general, one can say that Africans understand their identity in terms of dynamic spiritual and communal forces that determine life. Daily life should, therefore, be experienced not in terms of individualisation, fragmentation and materialistic exploitation, but in terms of mutual respect for people and values, which in turn reflects a spiritual destination rather than secular survival (Mtetwa 1996). To a certain extent, the plea for an African Renaissance is an attempt by politicians to home in on the notion of an African spirituality, and to advocate social change and transformation at the same time. It is a philosophical endeavour to empower Africans to move from deprivation and suffering to recognition (identity) and significance (dignity).

I therefore totally concur with Kenneth Kaunda's statement: "Let the West have its technology and Asia its mysticism! Africa's gift to world culture must be in the realm of human relationships" (19672: 22); human relationships as shaped by the ubuntu philosophy of human interconnectedness and humanity as shaped by a communal sense of belongingness. The spirit of Ubuntu - that profound African sense that we are human only through the humanity of other human beings - is not a parochial phenomenon but has added globally to our common search for a better world (Mandela 2005:82). This why Kahiga (2005:190) asserts that traditional African epistemology cannot be isolated from life events.

The African paradigm is therefore about life and human events of interconnectedness and interrelatedness. Their spirituality is exercised everywhere by means of gestures, singing and dancing. Even within the structures and names of their businesses and shops. Thus, the focus on the features of spaza spirituality in the article.

4. Church as informal "gossiping the gospel": The features of spaza piety in Africa

With "spaza" piety is meant: Faith in Cognito; faith operating within the disguise of faithful businesses where poor and unemployed people try to earn something despite external hinderances and governmental regulations.

Spaza is the Zulu word for camouflage, probably originating from the negative state attitudes and legislation specifically during the previous political dispensation of apartheid in South Africa (Van Zyl, S.J.J., A. A. Ligthelm 1998:3). The meaning of "spaza" as "being hidden" refers to the fact that business opportunities for black entrepreneurs were very strict and regulated in South Africa (Chatman, Petersen and Piper 2012:48). As indicated by Van Zyl & Ligthelm (1998:3), spazas/tuck shops are defined as grocery stores in a section of an occupied dwelling or in any other structure on a stand where people live permanently.

The business practice of spazas entails ordinary retailing. The practice implies the buying of consumer goods from manufacturers, wholesalers etc. and the selling of goods to clients over the counter, self-service or on demand. Although it seems as if spazas are survivalist enterprises operating at bread line of bare survival, it could be rendered as a new way of commercialisation on local levels (glocalisation) within the manipulating super powers of huge global enterprises.

Spaza shops includes for example in Addis Ababa, informal activities like petty traders, street vendors, home-based workers, waste pickers, coolies and porters, small artisans, barbers, shoe shine boys and personal servants (Sibhat 2014:1). The activities and income are partially or fully outside government regulation, taxation and observation, and thus to be rendered as "hidden", a kind of subterranean economy (Sibhat 2014:4).

Chatman, Petersen and Piper (2012:47) point out that small home-based grocery stores, known as spaza shops, are ubiquitous thought out the township areas in Southern Africa. They constitute an important business within the informal economy. However, due to the influx of many illegal migrants from the African continent, very specifically from Somalia, spaza shops create a lot of tension and conflict within local communities. They even contribute to new forms of anti-cultural campaigns and xenophobia.

Foreigners become intruders, robbing unemployed people within local communities from job opportunities. That is specifically the case in the Delft township near to Cape Town. The Somali business model has rapidly outcompeted local shop owners, bringing spaza prices down and forcing many locals to rent out their shop space to foreign shop keepers. The rise of the Somali shopkeepers thus represents a transformation of business practice in the spaza sector from survivalist to entrepreneurial modes (Chatman, Petersen and Piper 2019:47).

The climate of large-scale unemployment and high levels of poverty have resulted in a burgeoning microenterprise of informal undertakings within the economy of Southern African enterprises (Van Zyl, S.J.J., A. A. Ligthelm 1998:1). The proliferation of small enterprises, called spaza shops, is a direct result of relatively slow growth in the formal economy and the corresponding erosion of its labour-absorbing capacity.

Besides the threat of global economic enterprises and their impact on local economies, another threat endangers the impact of African spiritualities on the quality of survival strategies, namely the threat of colonialism in Africa. When dealing with the impact of Christianity on African spiritualities and the daily living of African people, the threat of colonialization (colonialism) always emerges in discourses on the Africanisation of the Christian faith.

Very surprisingly, at the southern coast of Ghana at the castle where the slaves with captured in dungeons before they were shipped to the Americas and sold like animals on a street market, I found the following remarkable inscription in the little museum at Cape Coast about both the disadvantages and advantages of the colonial period.

What I found is that in, for example, the Ghanaian public life, Christianity is still most influential and renders a vital component of survival strategies and ally in the attempt to combat poverty. One can call it an osmotic spirituality wherein the Christian faith contributes to the enrichment of daily survival strategies. The following photo was from an advertisement outside a church centre, advertising fun games, cooking competitions and health education.

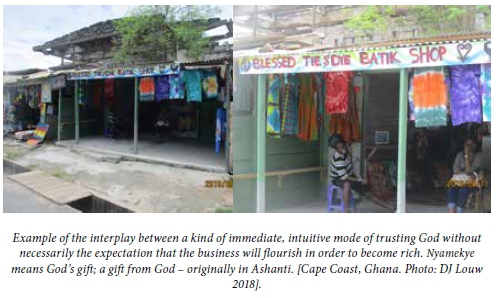

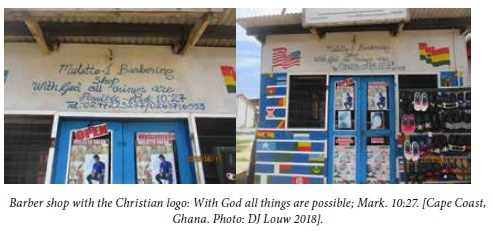

It was quite fascinating to walk along the streets in Accra Ghana and to read the different religious inscriptions on the sign boards of informal businesses. I found the following: "Divine 7 Enterprise"; "Blessed Driving School"; "My God is Able Shop"; "Exodus 2 Tyre Shop"; "With God All Things Possible"; "Perfect God Fashion"; "God First Industrial Company". Immediately I started to toy with the idea of a kind of commercialised or industrialised Christian piety; a mode of Christian spirituality that enables poor, often unemployed people, to survive despite very poor conditions. The Christian slogans and names become sermons right on the pavement of poor township spaces.

To be frank, I was immediately sceptic and wondered whether people want to merely manipulate their God-image into a kind of prosperity cult for the poor. My fear was that such a mode of piety, can lead eventually to disillusionment and existential fatalism; specifically, in cases when God is not going to bless the grocery store by selling more products. The idea that "with-God-all-things-are-possible" can contribute to spiritual pathology when the problem of unemployment and poverty is not solved instantly, constantly entered my mind: The spiritual pathology that faith and hope are like a pie in the sky and expose believers to painful disappointment; faith is only a fading mirage.

Another option is, that the slogan "with-God-all-things-are-possible" could be interpreted in a rather constructive way, namely as faith exhibited within the rhythm of daily attempts to survive and to fuel a courage to be. Could the pavement and the street spazas become sources of hope in order to survive? In order to keep on and not to surrender to their poor environment, could faith become indeed a source for resilience and the courage to be?

In an interview with people living in Accra,4 I was told that these Christian slogans should not be interpreted as a kind of syncretistic manipulation of God. In general (there are indeed exceptions), the presupposition in informal spaza spirituality is that faith is an integral part of daily living; trusting God is a mode of life and a vital ingredient of the struggle to survive. With the "fortogenetics of spaza faith" is meant a piety that renders life as a gift of God (Nyamekye).5Faith enables one to cope with the demands of life because the basic premise is: God is good (Ashanti slogan).

5. In conclusion

From an ecclesiological perspective one can interpret the spaza of informal, Christian businesses as modes of contextualised spirituality within the predicament of poverty and unemployment. It helps one to understand faith, hope and love as features of inhabitational Christian spirituality and streetwise preaching that witness the gospel as a way of life; streetwise liturgies of a vivid and living hope; an inspiring force; i.e. piety as a mode of constructive resilience (inner strength), anticipating something new and the persistence of caring and compassionate love. This kind of informal piety can be called a kind of informal ecclesiology (mens-kerk) of living one's faith within structures that reflect the fact that life is indeed a gift of God (See the meaning of nyameke, note 5).

To my mind the impact of the notion that life is indeed a gift of God, can be summoned up in the following three components of what can be called a "spirituality of streetwise being" and a "disposition of beautifying existence": Public resilience, sustainable being as the courage to be and parrhesia as indication of a boldness of being, emanating from the gospel of cross and resurrection. The three could be rendered as the basic spiritual pillars for a Christian understanding of an ecclesiology of spaza faith. Spaza faith is about trust exhibited and incarnated in the structure of streetwise businesses reflecting something of the faithfulness of God despite severe living conditions such as structural poverty and the desperate position of unemployment.

Homiletics within the framework of a community approach to praxis thinking and practical theological reflection, should align along the following spiritual indicators for contextual preaching within poor communities and spaza enterprises.

• Faith as public resilience -preaching as the art of bouncing back (the inner strength to bounce back). The emphasis on strength or boldness is intended to encourage a move away from the paradigm of pathogenic thinking and the attempt to link health to a sense of coherence, personality hardness, inner potency, stamina or learned resourcefulness (Strümpher 1995:83). In this regard, the mode of resilience comes into play; resilience (from the Latin resilire = rebound). It refers to the capacity of the will not to be hampered by the external barriers, pressure, not to be cast down, but to bounce back with inner strength and constructive, positive energy.

• Hope as an existential courage to be - preaching as fostering sustainable being. Hope not as wishful thinking, but as a new mode of being and thinking, anticipating in terms of trust, the faithfulness of God as source for visionary, imaginative thinking (fides quaerens imaginem) despite worse living conditions and the factuality of weakness and frailty (Louw 2016:451-473).

• Love as persistingparrhêsia - boldness of speech and disposition. According to Hahn (1976:736), parrhêsia in the gospels of John and Paul, characterizes effective preaching of the mysteries of God (Eph. 6:19), and the honouring of Christ in life and death (Phil. 1:20). "Since perseverance, perhaps in prison, is demanded of the disciple (cf. Eph. 6;20), parrhesia has here also the sense of boldness and courage".

With reference to Johan Cilliers' major research topic: Dancing with Deity. Re-Imagining the Beauty of Worship, the spaza piety of commercialised faith, disguised in informal business structures, makes the informal shops of spaza spirituality, beautiful cathedrals of how poor, unemployed people can dance with God in the streets of poor townships throughout Africa. The slogans on informal spaza structures "God-is-good", "With-God-all-things-are-possible", are indeed very powerful sermons; expositions of streetwise homiletics wherein the spazas become texts and preaching (gossiping the gospel) the message of God's providence despite poverty and unemployment. In terms of my understanding of aesthetics, the spaza slogans beautify the worse conditions of township life: fides quaerens beatitudinem despite the paradox of ugliness! This kind of foolishness is divine: In forsakenness by God, the Spirit whispers the coram-Deo-presence of divine absence.

Bibliography

Bohren, R. 1975. Das Gott schön werde: Praktische Theologie als theologische Ästethik. München: Kaiser Verlag. [ Links ]

Campbell C. and J. Cilliers. 2012. Preaching Fools. The Gospel as a Rhetoric of Folly. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press, 2012. Cillers, J. 2008. Worshipping in the Townships - A Case Study for Liminal Liturgy? In: Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 132, 72-85.

Charman, A., L. Petersen, L. Piper. 2012. From Local Survivalism to Foreign Entrepreneurship: The Transformation of the Spaza Sector in Delft Cape Town. University of the Western Cape. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236825866_From_local_survivalism_to_foreign_entr. [Accessed: 12 March 2019].

Cilliers, J. 2012. Dancing with Deity. Re-Imagining the Beauty of Worship. Wellington: Bible Media. [ Links ]

Cilliers, J. 2016. A Space for Grace. Towards an Aesthetics of Preaching. Stellenbosch: Sun Media. [ Links ]

Cox, H. 1969. The Feast of Fools. A Theological Essay on Festivity and Fantasy. New York: Harper & Row Publishers. [ Links ]

Hahn, H. C. 1976. Parrhêsia. In C Brown (ed.), The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology Vol. 2. Exeter: Paternoster Press, pp. 734-737. [ Links ]

Kahiga, J K. 2005a. Epistemology and Praxis in African Cultural Context. In: African Ecclesial Review. AFER. September, Vol. 47, No. 3, 184198. [ Links ]

Landman, Christina 2009..Township spiritualities and counselling. Pretoria: Research Institute for Theology and Religion, Unisa. [ Links ]

Kaunda, K. 19672. A Humanist in Africa. Letters to Colin Morris. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Louw, D. J. 2008. Cura Vitae. Illness' and the Healing of Life. Cape Town: Lux Verbi. [ Links ]

Mandela, N. 2005. In the Words of Nelson Mandela. London: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Miller, G. 2003. Incorporating Spirituality in Counselling and Psychotherapy. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons. [ Links ]

Mtetwa, S. 1996. African Spirituality in the Context of Modernity. Bulletin for Contextual Theology in Southern Africa and Africa 3/2, 21-25. [ Links ]

Sibhat, E. E. 2014. Cause and effect of Informal Sector: The Case of Street Vendors in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Univeriter 1 Nordoland Handelshogskolen i Bodo, HBB. [Online]. Available: https://brage.bibsys.no/xmlui/handle/11250/225025. [Accessed: 12 March 2019].

Van Zyl, S.J.J., A. A. Ligthhelm. 1998. Profile Study of Spaza Retailers in Tembisa. Bureau of Market Research, Research Report no. 249. Pretoria: UNISA. [ Links ]

1 In 2015, the church took a decision to allow individual church councils to recognise same-sex marriages and also scrapped a rule that gay ministers of the church had to be celibate. A year later in 2016, the church adopted a new policy, going back on the 2015 decision outlawing the acceptance of same-sex unions. The court found that it was unfair to exclude members of the church from the full and equal enjoyment of all rights and freedoms that the church offers because our being human does not reside in our religious or denominational affiliation but in our constitutional right, freedom and dignity. The judge in the court case about the 2015 decision of the general synod of the Dutch Reformed Church on homosexuality (same-sex marriages) had to warn the church that the 2016-decision was, according to my interpretation, in fact unlawful, foolish and stupid. Our being human and our dignity is not determined by our religious affiliations, but by our being functions beyond racial and gender and sexualised categories; i.e. by our affirmation by God as an act of creation (ontic identity).

2 This is in line with his tutor in homiletics in Heidelberg, Germany: Rudolf Bohren with his emphasis on the beautification of God (Das Gott schön werden 1975).

3 Landman (2009:2-3) refers to this aspect of healing in her definition of "township spiritualities": "This immediately calls for a definition of township spiritualities. Here "township spiritualities" is seen as a combination of (Western) diaconal healing, (African) ritual healing, (Pentecostal) faith healing, and human rights. As such, township spiritualities - although they have internalised aspects of Western spiritual views on healing - are in constant dialogue with Western medicine as practiced by state hospitals, and western counselling as practiced widely in South Africa".

4 The interview was with some of the Ghanaian delegates to the following conference I attended in 2018: AAPSC (African Association for Pastoral Studies and Counselling). The 7 African Congress. Venue: Presbyterian Women's Centre, ABOKOBI, Accra, Ghana, September 17-21, 2018.

5 Nyamekye means; God's gift; a gift from God (Originally in Ashanti). It was explained to me by delegates to the mentioned conference that this Ghanaian concept is used to reflect a kind of common existential experience of the fact that God cares and provides. In the first place it is used not to manipulate God but merely as an expression of trust and life is essentially a gift of God because is "good".