Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

On-line version ISSN 2413-9467

Print version ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.5 n.2 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.supp.2019.v5n2.a10

ARTICLES

Images Preaching – The Significance of Aesthetic Experiences with Artworks for the Art of Preaching1

Grab, Wilhelm

Theologische Fakultät der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. wilhelm.graeb@rz.hu-berlin.de

ABSTRACT

Art confronts us with seeing our seeing as well as with the ambiguity of the meaning of what we see. This is the double transcendence of art whereby it acquires its theologically productive function. In this article I want to show that images of art can preach and how they do so, using as illustrations stained-glass windows by Johannes Schreiter in the Jakobi-Kirche in Göttingen, and a work of art that was shown at dOCUMENTA 13 (2012) in Kassel.

Works of art can irritate our eyes. There is also the beauty of humour and folly that works of art can bring to preaching. If you have a sense of humour, you can see many things - especially those that are obviously distressing and oppressive - quite differently, and even give the negative a positive interpretation. Artworks can express such humour or motivate us to perceive it. I demonstrate at the end of this article how a contemporary painting conveying a disturbing picture of the crucified Christ can inspire preaching.

Keywords: Aesthetics; artworks; images; religious experiences; transformation

Works of art are not just intended as entertainment. They have the power to show us things differently from what we expect to get. They shift our view of reality. They open up new perspectives. They compound our experience of them with new experiences. When we engage with artworks and look into them, they change us. For this reason, Johan Cilliers has consistently not only referred to artworks, but has made the central theme of his homiletics the aesthetic-theological experience in and with space and time as intensified by images of art. For him the task of preaching is to reframe our images of God in the light of our images of reality (Cilliers 2012b, 2016). Preaching therefore gains its greatest potential for inspiration through artworks, because they change our view of reality. Artworks and the aesthetic-religious experiences they evoke in us are the best way to learn how to preach. This article will explore the question of the relationship between art and religion, aesthetic and religious experience. Its intention is to follow in the footsteps that Johan Cilliers has laid out in his attempts to visualize the theological potential of images and to highlight the significance of aesthetic experiences for the art of proclaiming "the gospel as a rhetoric of folly" (Campbell, Cilliers 2012c)

1. Images as religiously inspiring and theologically significant signs

Things and events brought into being by artistic creation become works of art by transcending the fields of meaning within which we practise our everyday lives. They make things manifest that do not fit into any of our practical and functional contexts. The production and reception of art are always accompanied by the question of what use it is at all, but it is also true that admirers as well as despisers of these works of art find themselves attracted to them.

A work of art that has value in itself rejects the question of its utility anyway. Or it defines itself in such a way that its purpose lies in its uselessness. Yet, of course, it inevitably raises questions about its utility. Art has developed into a social operating system of its own. Art is being traded. Infrequently the price of an object determines that it could be classified as a work of art, or at least something that is considered or recognized as desirable art or not. Art is a function of social distinctions. It serves as a status differentiator (Bourdieu 1982).

Art can also enter into religious and ecclesiastical contexts - and it has always done this excellently, right down to the modern age. In this case we speak of ecclesiastical art or of Christian art or even - but then, disparagingly - of religious craftsmanship. Explicitly religious art no longer has a good reputation today. Anyone who considers himself to be art-savvy usually does not attach much importance to the artistic value of religious art, at best respecting the artist's craftsmanship.

Religious craftsmanship, placed on church and private altars, that has nothing new to show and is not exciting to think about theologically is rightly not the object of particular attention, either for aesthetic or theological reasons. Yet it is not the religious motifs that prompt criticism of such art, but rather the fact that it is obviously a matter of bad art that has become clichéd - something that is just as possible with non-religious motifs as it is with religious ones.

When we talk about the theological interpretation, it depends on the concept of art that the works of art enables or even evokes. I apply the concept of art to such artefacts that give us a new look at reality, provide new experiences within our everyday experiences, surprising thoughts and unimaginable feelings. It is clear that this binds the concept of art to the aesthetic experience (Bubner 1973). But this means that contemporary art can also be recognized as art, even if it works with traditional religious motifs. It is art as well as religious art, insofar as it gives a representation of traditional religious pictorial signs, which direct the viewers' attention entirely to the depiction and leads them to decode its meaning.

Religious art becomes art by opening up a new perspective on traditional religious motifs. On the other hand, conventional religious art has neither aesthetic force nor religious significance, not because of it has religious content, but because it does not evoke meaningful religious interpretations, nor does it prompt deeper thoughts or poignant feelings in its observers. The religious significance of visual art does not depend on the content of the image, but on whether or not it gives us an aesthetic experience that pushes us towards theological interpretation.

Images, installations and performances of art without religious allusions, insofar as they are aesthetically stimulating - that is, they demand interpretation and not merely the expression of a craft that is produced to order - lead to aesthetic experiences. They touch us emotionally, on a pre-linguistic level. But they also encourage us to elevate into a linguistically articulated interpretation of what we feel when we encounter them. They get us thinking and they move us emotionally. They touch and change us (Fischer-Lichte 2003).

For images, installations, performances, if they are art or become art, it has not always been obvious what they mean, what they want to tell us, what they do to us. They not only let us see familiar things and ideas in new and different ways. They do not just move us. They even make it evident that the meaning of things always depends on the point of view from which we observe them (Gräb 1998).

Art confronts us with seeing our seeing, as well as with the ambiguity of the meaning of what we see. This is the double transcendence of art, whereby it acquires its theologically productive function (Seel 2012). The power of transcendence, and thus the religiously productive function, manifests in the images, installations and performances of art because they stimulate us to perceive the nature of our perception. Therein also lies their potential for theological stimulation.

2. Theology explaining the religious sense of art

Images and installations that have the potential to become art by virtue of the aesthetic experience that they trigger can always achieve this effect through their own power. They initiate new perspectives. They also challenge stereotypical religious beliefs and attitudes. They are in the first place a living and productive mechanism of aesthetic expression. This makes art exciting, productive and lively for theology, especially when it stages biblical motifs and at the same time produces their interpretation, but by no means only then.

First of all, I want to show that contemporary art can proclaim God and how it can do so even without resorting to traditional religious imagery. This can be seen at dOCUMENTA 13 (2012) in Kassel, and in Johannes Schreiter's abstract church windows in the Jakobi-Kirche in Göttingen.

dOCUMENTA 13 - Lara Favaretto, Two-part project: Momentary Monument IV

Car scrap, parts of machinery, battered drainpipes, the sidewall of a container, the axle of a tractor and wheels - this landfill is located on the northern outskirts of the "Kulturbahnhof" in Kassel. Presumably the material will be removed from the site of the "Kulturbahnhof" - at the latest after the end of dOCUMENTA (13) - and sent to a nearby recycling facility. The city of Kassel will not buy it after the end of dOCUMENTA (13), as it did with the "Himmelsstürmer" by Jonathan Borofsky after Documenta 9. Borofsky's "Man walking to the sky" is now on the square in front of the "Kulturbahnhof". Lara Favaretto must have anticipated the very different fate of her artwork on the abandoned track behind the "Kulturbahnhof", because she gave it the title "Momentary Monument".

But those who have only seen the landfill did not properly perceive the "monument" erected for the dOCUMENTA (13). Thoughtlessly they walked past the exhibition space designed as a museum, which was located about 30 meters in front of the scrap heap in a warehouse in the north wing of the "Kulturbahnhof". There the artist showed nine metal objects that she had taken from the scrap heap, quite obviously because of the power of their own forms. She presented each of these sculptural objects on a white pedestal and remodelled the warehouse into a room of a museum, lit in bright white lighting. Thus, the most valuable pieces of the scrap heap were transformed by the aesthetically sophisticated staging. They had become Ready-mades in the White Cube setting of a gallery.

However, the scrap heap itself now lacked some its most impressive pieces. The artist obviously did not want to accept that. That's why at the very places from where the objet trouvé were taken to be set in the museum, she placed substitutes made of raw cement.

Art is here the designed form. The nature of things strives for this designed form. The formative force goes further than our aesthetic creativity. Ultimately, we can only imitate what we find in nature. The human hand touched and shaped every form that humans have found in nature. But not only shaped, also exploited, consumed - we have destroyed nature. Whatever we destroyed, we have to rebuild. We are capable of doing this as humans. Nothing is lost. Monuments of art are commemorating the people who forget - even temporary ones that arise and disappear.

Lara Favaretto's project for dOCUMENTA (13) consists of two parts. The other part of Momentary Monument was, or may still be, in Kabul -according to the statement of the artist in the catalogue. But who is already traveling to Kabul to see if that is true? Yet the artist obviously intends to evoke the motto of dOCUMENTA (13), "Collapse and Recovery", with parallels between Kassel and Kabul in mind. From a distance, the scrap heap resembled the ruins of cities destroyed by war bombs - Kassel was heavily bombed during World War II.

According to the catalogue and the panels at dOCUMENTA (13), the artist recalls the history of the Afghan city of Kabul, which has been battered by decades of war. She collected oral traditions and judged their value. She questioned Kabul citizens about the places most important to them, historically, socially and personally. From the places that were named, she chose the six most important ones. There she took soil samples in the form of cylindrical soil layers. In Kabul she collected not pieces of scrap metal but fragments of the earth, each cut into three pieces of one meter in length, which became the "Momentary Monument". In Bagh-e-Babur, Kabul's oldest historical garden, the artist presented these sculpted cylindrical drill cores in an exhibition room, along with the questionnaires that Kabul's citizens had filled in with information about the most important places in their city for them.

Nothing is lost, nobody is lost. Finally, the art keeps the archaeological traditions present. This does the work of remembrance, exposing what is still there, but would have been overlooked if it had not been given an aesthetic form. Art also keeps the lost and the forgotten present. It manifests the "meaning and taste for the infinite" (Schleiermacher) in the midst of fleeting and needy times.

The Window Cycle by Johannes Schreiter in St. Jakobi, Göttingen

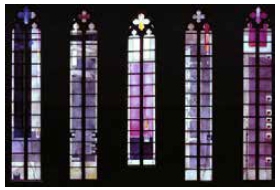

In the northern aisle of St. Jakobi in Göttingen, there have been five coloured glass windows since 1997, designed by the artist Johannes Schreiter.

Johannes Schreiter, one of the most important German glass artists of the 20th century, in 1997/98 designed a whole cycle of windows for the St. Jacobi-Kirche in Göttingen (Besser 2009). Schreiter paints unidentifiable stories but interprets a biblical text, Psalm 22. Jesus, hanging on the cross, prayed this psalm saying: "Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?" that is, "My God, my God, why have You forsaken me?" (Matthew 27:46). The psalm has five parts and is about abandonment, death, prayer, church, resurrection. Johannes Schreiter did not depict these five "stanzas" or "acts" (if you read the psalm as a drama) but translated them into his own language: colours and shapes, lines and light. Thus, he created a work of art that makes the psalm new. But you do not have to know the psalm, so the images speak of light, shapes and colours. The artwork works without words; only colours and shapes, lines and surfaces express its symbolic significance.

These colours and shapes, these lines and surfaces have their effect; they are an aesthetic programme also quite independent of the psalm Johannes Schreiter had in mind when he designed these windows.

The background is the same in all windows: a colour like wet sand. And against this background - that's how it works - hang "cloths" in different colours, as they do in Lutheran churches in front of the altar and from the pulpit, and different "cloths" hang there depending on the liturgical order.

A narrow "cloth" in dark blue in the first window, a grey-black in the second and in the fourth, a red in the third (in the glassworks this colour is called "golden rose"), and in the fifth window a "cloth" whose colour could perhaps best be described by imagining that the glass of the third window (gold-pink) has been placed on that of the fourth (grey-black).

In all windows (lead)lines appear like cracks. Likewise, in all windows there are geometric shapes: angular, edgy and pointed; round, soft - underlined by the hue - only in the crossings (in all windows at the top). Some shapes are repeated: squares in all windows, but in different colours! In windows 1 to 4 there are brackets: one on the bottom in first window, four in the second; one again in the third and the fourth, many in the fifths window -but the brackets changes their place, their form and direction.

This is non-representational painting. Abstract art, yes, but the artist works with signs. Those who are interested in interpreting these signs, following this composition of surfaces and colours, lines and light, and thus perceiving the theological programme behind the aesthetic, should read Psalm 22. The five stanzas or acts of Psalm 22 can stimulate and support a theological interpretation of the aesthetic impression conveyed by the composition of colours, shapes and signs of the windows. Finally, as one can see, Psalm 22 has also influenced the artist's choice of colours, shapes and signs.

The artist's image programme inspired by Psalm 22 makes no identifiable references to the iconographic traditions of Christian art. Precisely because of this abstract nature of the art, it stimulates the religious imagination of the viewer, who is motivated by the visual language of the psalm. Unlike traditional Christian art, which is tied to the iconographic repertoire of forms, this biblically inspired abstract art is religious insofar as it is much more open to interpretation. Rather than representational painting, this abstract art corresponds, so to speak, to the non-objective reality of God, on the one hand, and the productive imagination of the creative human being, on the other hand.

The glass paintings by Johannes Schreiter show in a special way that the religious content of the depiction depends on the religious imaginary of the viewer and at the end the theological interpretation that it invites. At the same time, theologically speaking, they acknowledge the prohibition of images. Schreiter's glass paintings do not show God, nor do they show the people calling for him. They do not create an image of God and do not convey an image of humankind. But they can initiate an experience of transcendence through reading the colours and signs in the light which is shining through. Nevertheless, a theological interpretation of the glass pictures initiated by this aesthetic experience also needs some support from the verses of Psalm 22. But there are also clues in the ambiguous references that can be recognized in the forms, colours and signs.

Without the theological interest of the observers in seeking to grasp the meaning of the signs of this abstract art, its religious content does not emerge. An interplay between the aesthetic experience and the theological interpretation of this experience has to be activated. Then, I would say, this abstract art realizes the theologically fundamental idea that the transcendence of the divine reality becomes present through the immanence of signs colours and light.

Taking up the suggestions of Psalm 22 in the following sections, I undertake my interpretation of the Schreiter window cycle in St. Jakobi, emphasizing the theological references emerging in my interpretation.

Window 1

"My God, I cry out by day, but you do not answer, by night, but I find no rest." (Psalm 22:2)

The viewer encounters the first window when he enters the church from the west through the main portal. At first, the darkness overwhelms the light of the day. The night blue dominates in the "cloth" falling down in the first window. The contrast between light and dark, day and night is clear. Bottom left we see a bracket pointing upwards. Calling in vain in the light of the day and in the darkness of the night, waiting. This bracket represents the ego of the praying human being. No meeting, anywhere. Put in the clamp, lying on the floor, hiding itself. Lonely, without anybody else, in vain all shouting. There is no one who hears. In the lower middle section of the window we see on the right side a bracket falling down from above. But this bracket is closed at the bottom. It seems that a correspondence with the other, lonely bracket lying on the ground does not occur.

Window 2

"My mouth is dried up like a potsherd, and my tongue sticks to the roof of my mouth; you lay me in the dust of death." (Psalm 22:15)

In the second window the signs of increasing despair multiply. The bracket at the bottom representing the buffered ego tries to assert itself. But the cries of buffered ego do not reach the wall of silence. Many brackets spring up with their white tips - they represent the horns of the wild bulls, the dogs and the gangs of the wicked, who press the desperate worshiper from all sides. The lonely bracket representing the buffered ego screams hoarsely. The grey-black band now fills the whole window, surrounded by death's dust. The grey-black night of death is impenetrable. The association suggests that Jesus' cry of distress on the cross was already that heard in Ps 22: "My God, my God, why have You forsaken me?" (Matthew 27:46)

Window 3

"You have answered me!" (Psalm 22:20b)

The change, the turn towards the relief occurs in the third window. The darkness is dwindling. A long, red, brightening band of light now fills the centre of the picture. The light reaches up to the top. Glowing white, the buffered ego also stands out of the darkness. It winds its way into the warm red, into this deep red, which lightens upwards. Like a stream of heat, the red band of light creates the connection between the light coming from above and the threatening darkness from which the buffered ego is just emerging. One could also say that the warming red takes into itself the buffered, lonely ego, hidden from itself, excluded from the others and threatened in its right to live. Clarity spreads that enlightens everything. The buffered ego, still drawn into the dark, at the same time imagines the feeling of being included in a stream of warmth and light. The lost, hostile, desperate ego of the praying human being draws new hope. The caller finds a counterpart, hears the answer. Silent only, the calling I corresponds to a bright yellow, falling from top to bottom, still a closed bracket.

Window 4

"In the midst of the assembly I will praise You." (Psalm 22:22b)

In the 4th window, on the top right, we see the previously closed bracket that falls down from above, but now it opens downward. The encounter with forces from whom help could come takes place. The closed bracket representing the buffered ego opens itself finding access to the community of the church. One can see that because the artist located in the falling "cloth" from top to bottom, changing from a black-blue to a reddish band of light, the floor plan of the ceiling vault of Jakobi-Kirche. The night-time experiences are still vivid. The rather dirty blue-grey is still spreading: but now a hot stream of love envelops the desperate night-time experiences. From above, the now open, self-reliant and community-oriented ego finds the freedom to search the church.

Window 5

"All who go down to the dust will kneel before him." Ps 22:29a)

In the fifth and last window, the brightly warm red, which comes from above, condenses. Its heat flow spreads out over the whole window. The red colour overlays the dark black and blue. But it also displaces the pure, cold white. The former lonely, closed bracket is not only opened now, it is now multiplied on the left side a countless number of times. On the right side, we see seven open brackets into which the warm red flows into the dark surface. The former closed egos are no longer lonely, not buffered, but open to each other and lifted in the assembled church. Even beyond death. On the left, the multiplicity of little brackets lines up to infinity. Nobody is lost. No one lives in vain. As if strung together on a chain, the infinite number of the egos, open and related to one another, rises from the bottom to the top and falls from the top to the bottom. Love keeps the memory of each individual alive.

The glass paintings by Johannes Schreiter convey more than words can say. They basically show more than pictures can show. Their translucency makes the forms, colours and signs a reference to another, transcendent reality that bears all life and yet one which no living human being has ever seen. They do not give us God to see but make the immanent reality transparent to the presence of the transcendent all-encompassing divine in it.

3. How Schreiter's glass paintings proclaim God

Theologically, Schreiter's glass paintings expresses God's presence in the world. They do this in such a way that they respect the limit set by the biblical prohibition of images in order to avoid the objectification of God. No one who seeks God in Schreiter's stained glass finds him in something that would be conceivable as a finite object. Rather, the word "God" becomes an interplay of signs, forms and colours. This indicates that the word of God wants to be understood in the sense that encompasses the whole of reality.

Of course, only those who are open to the word of God and disposed to associate the meaning of this word with the sense of the whole of reality will find God in the interplay between the abstract forms, colours and signs of these glass images. Their discovery will be supported by the inspiration given by the church building with its references to the glass paintings and by the meaningful references to Psalm 22. The theological interpretation of these glass paintings thus unfolds in the correspondences between the abstract pictorial symbols, their allusions to Psalm 22, on the one hand, and the viewer's willingness to reflect on the religious meaning of the symbols, on the other.

Viewers see that the windows light up, that they have their own light. They feel that the windows offer more to see than what appears in front of their eyes. You may also experience the church building and the space it opens up differently, in the refractions of the light falling through the windows. In addition, if the viewers open up Psalm 22 and meditate on the play of shapes and colours in the windows, they can also engage in the dramatic search for meaning, belonging and community of a desperate, lonely, self-absorbed, alienated, god-forsaken human being. They might find a clarification of their existence, the liberation to themselves through their access to the community of the Church, but then possibly also the traces of the presence of the invisible God. They can realize that God is there without being an object in this world, that he carries us and the entire world, and fills us with light that makes us, and the world see. Then the glass paintings open up to those who are meditatively immersing themselves in them, as the last verse of another psalm says: "For with you is the fountain of life; in your light we see light" (Ps 36:09).

The glass paintings by Johannes Schreiter do not show anything that could be connected to the traditional symbolism of Christian art. Not the biblical story of salvation. Not the faces, not the bodies of human beings, not their misery, not their happiness. None of the forms and signs depicted on the windows are part to the traditional imaginary of the Christian church. And yet, in the interplay of forms, signs and colours, a comprehensible theological interpretation can be built up. Anyone who is religiously open-minded can be involved in the drama of a divine encounter through the glass pictures. Inspired by the words of Psalm 22, these glass pictures lead to the search of a human being for community with others and with God as well as God's closeness to this human being and his presence in the church. Finally, they announce salvation to the congregation assembled for the praise of God.

Not only the work of Lara Favaretto, but also the non-representational glass paintings by Johannes Schreiter allow themselves, like all works of contemporary art, to be perceived and judged purely aesthetically, whether as a performative staging of a rubbish heap, or as a dramatic colour composition in the sequence of abstract signs and forms.

But also like all contemporary artworks, the windows by Johannes Schreiter in the Jakobi-Kirche in Göttingen do not want to become cult images. Nor do they place themselves directly at the service of the church's proclamation. They are artworks, originating in human creativity, the expression of human imagination. They build their own reality from interpretive signs, forms and colours to give us something new to see. At the same time, they proclaim God through the aesthetic experience that their images generate. The aesthetic experience establishes the relationship to the divine - the artwork irritates and we decode its religious meaning.

4. The humour, the comic and the folly of art in the church

Images of art, they irritate our eyes. One can also see in this effect the effect of a kind of humour peculiar to art. Humour is the ability to register a surprisingly different, distancing, oblique view of things. If you have a sense of humour, you can see many things, especially those that are obviously distressing and oppressive, quite differently, and even give the negative a positive interpretation. Often artworks also instil a sense of humour. Nevertheless, this humour of artworks is often not understood, especially in the church because of the strange perspective that art adopts. I want to conclude with a brief account of a conflict that the 'foolishness of art' provoked as soon as it entered the Church. Of course, this can hardly be done without referring to Johan Cilliers' talk of the foolishness of a sermon preaching the death of God on the cross as the grounds of Christian hope (Campbell/Cilliers 2012c).

"The comic," says sociologist Peter L. Berger, who has dedicated a particularly stimulating study to the religious dimension of humour, "presents us in its most intense forms, such as folly, with a counter-world, an inverted world. This counter-world is revealed as something hidden behind or under the world we usually know" (Berger 2014, 197).

The perversion of the world on the cross of Christ is depicted in a painting by Georg Baselitz, which he entitled "Dance around the Cross" (Baselitz 1992). He dedicated this painting in 1992 to the Annenkirche Luttrum (near Hildesheim, where Baselitz lived that time) (Zick 2003, 164-170). The title refers to the fierce arguments triggered in the congregation by the donation of this painting (Mertin 1994). There was even a split in the community.

Some of its members no longer went to the service; because they could not bear this image in their church; indeed, some saw it as blasphemy. They found the upside-down Christ a provocation.

Georg Baselitz is one of the contemporary painters who not only turns all of his motifs upside down, but also repeatedly draws on the iconographic traditions of Christianity. The inversion of the motif has, of course, become the path towards a new invention for Baselitz.

He imagines an inverted world, a counter-world, supported by the expectation that the perversion of the perverse world, in which so many people are cheated of their fortunes on a daily basis, could possibly become transformed. But the crazy thing about this image is that it turns everything upside down, the crucified Christ as well as the trees all around. What evokes the humorous reception of this comical picture is at the same time what makes it into a religious artwork. It sets before us a sign that disturbs, provokes by presenting a different view of reality. In a theological interpretation, this sign shows that God is making the wrong world dance, and that his power is powerful even in the weak (Cilliers 2012a).

References

Baselitz, Georg 1992. Dance around the Cross, Annenkirche Luttrum. [Online]. Available: https://www.google.de/search?q=Annenkirche+Luttrum+Tanz+ums+Kreuz.

Berger, Peter L. 2014. Erlösendes Lachen. Das Komische in der menschlichen Erfahrung. Berlin /Boston 22014.

Besser, Yvonne 2009. Religiöse Bildsprache der nicht-figurativen Moderne. Der Fensterzyklus zu Psalm 22 von Johannes Schreiter in der Jakobikirche Göttingen. Frankfurt am Main.

Bourdieu, Pierre 1982. Die feinen Unterschiede. Kritik der gesellschaftlichen Urteilskraft. Frankfurt am Main.

Bubner, Rüdiger. Über einige Bedingungen gegenwärtiger Ästhetik, in: Neue Hefte für Philosophie 5, 1973, 38-73.

Cilliers, Johan 2012a. Dancing with Deity. Re-Imagining the Beauty of Worship. Wellington: Bible Media. [ Links ]

Cilliers, Johan 2012b. "The optics of homiletics: Preaching as reframing of perspective." Inaugural lecture delivered on 21 February 2012.

Campbell, Charles L. and Cilliers, Johan H. 2012c. Preaching Fools. The Gospel as a Rhetoric of Folly. Baylor University Press. [ Links ]

Cilliers, Johan 2016. A Space for Grace. Towards an Aesthetics of Preaching. Stellenbosch: Sun Press. [Online]. Available: http://scholar.sun.ac.za/handle/10019.1/86796 [ Links ]

Favaretto, Lara 2012. Two Part Project: Momentary Monument IV. Photo: Wilhelm Grab © dOCUMENTA (13).

Fischer-Lichte, Erika 2003. Ästhetik des Performativen. Frankfurt am Main.

Grab, Willem 1998: Kunst und Religion in der Moderne. Thesen zum Verhältnis von ästhetischer und religiöser Erfahrung, in: J. Herrmann, A. Mertin, E. Valtink (Hg.), Die Gegenwart der Kunst. Ästhetische und religiöse Erfahrung heute. München. 57-72.

Mertin, Andreas 1994. Perspektivenwechsel. Der Streit um die Kunst in Luttrum, in: Kunst und Kirche 4 S. 226-228.

Schreiter, Johannes 1997, 1998. Windows in St. Jakobi Göttingen. [Online]. Avaulable: http://www.evlka.e-msz.de/extern/goettingen/st-jacobi/Jakobi/diekirche.html

Seel, Martin 2012. Transzendenzen der Kunst, in: Der religiöse Charme der Kunst, hg. von Thomas Erne/Peter Schütz. Paderborn: S. 37-52.

Zick, Markus 2003. Theologische Bildhermeneutik. Ein kritischer Entwurf zu Gegenwartskunst und Kirche. Münster.

1 This article refers to parts of my book: Grab, Wilhelm 2018. Vom Menschsein und der Religion. Eine Praktische Kulturtheologie. Tübingen. 263-280.