Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

On-line version ISSN 2413-9467

Print version ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.5 n.1 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2019.v5n1.a11

GENERAL ARTICLES

Human displacement as challenge to pastoral caregiving. Towards a hermeneutical design for an existential and diagnostic approach to ecclesial welcoming

DJ Louw

Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa djl@sun.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The current refugee and migrant crisis are closely connected to a kind of global fear and paranoia: The fear for the outsider and stranger (xenophobia). The basic dilemma of displacement and the quest for home, fuel the spiritual question of the meaning and significance of life. It is argued that an existential approach to the predicament of displacement can help to understand the complexity of the crisis. The article is an attempt to design a diagnostic model for a hermeneutical approach that deals with the importance of place and space. In this regard, the notion of hospitality should be introduced as a basic pastoral category in the attempt to address the threat of xenophobia. A diagnostic chart is designed as hermeneutical tool for a practical ecclesiology of home and compassionate understanding of the crisis of displacement and dislocation.

Keywords: Displacement; diagnostic approach; hermeneutics of life; philosophy of space and place; hospitality; ecclesial welcoming

1. Introduction

One can state emphatically that migration has become a feature of human life in the global village. In fact, migration, and therefore also the phenomenon of displacement, have become existential realities in post modernity (Polak 2018:19-25). The pace of illegal migration from the Southern Americas north has picked up dramatically over the past decade, propelled in part by the lingering aftermath of the 1970s and '80s civil wars in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. In depictions of this modern Latin American migration into the United States, illegal migration and fleeing refugees have become a human tsunami sweeping over borders (Gorney 2008).

As a matter of policy, the US government's immigration policy brings anew the crisis of human displacement under our attention. According to news reports, this policy is separating families who seek asylum in the US by crossing the border illegally. In fact, dozens of parents are being split from their children each day while the children are sent to government custody or foster care. Due to their official policy, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, announced on the 17th of September that the Trump administration will sharply reduce the number of refugees in the United States from 45,000 to 30,000 in the next fiscal year (News Ticker 2018:9).

The philosopher and sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, (2016:125) calls the position of the illegal immigrant and fleeing refugee, the phantom at the borders of human existence. Bauman's fear is that, due to the risk of safety, the refugee dilemma becomes isolated from a global, moral responsibility. The crisis is then becoming dehumanised; it becomes objectified without any connection to compassion and solidarity.

The refugee dilemma boils down to suspicion and distrust (Bauman 2016:125). People don't trust one another. Enmity, suspicion and xenophobia separate people and undermines a basic sense of belongingness. Thus, the crisis of displacement.

Emmanuel Lartey (2018: ix) refers to this human predicament of displacement: "Humans are locational beings, constituted, formed, framed, and shaped by geographical, societal, political, economic, and physical environment." Thus, the reason for his argument that spirituality is deeply understood as rooted in the land of one's birth.

Displacement is about disorientation and the existential pain of transition. In the migrant and refugee crisis people have been forced out of their "natural habitat" and have become strangers in a strange land in which the social and political codes are difficult to read (Walton 2018:171). The predicament of displacement arises the question: Where am I? (Walton 2018:174). Thus, the research project of the Society for Intercultural Pastoral Care and Counselling (ICPPC): Where are we? Pastoral Environments and Care for Migrants (Schipani, Walton and Lootens 2018).

I partook in this research project and intends to respond to this quest for space and place by attending to the existential dimension of a pastoral hermeneutics, and its impact on the reframing of ecclesial thinking. Very specifically to the challenge of relocation within the parameters of an ecclesiology of home, space and place.

What are the basic directives and spiritual and theological indicators for a pastorate of hospitable relocation and an ecclesial approach to home and a habitus of welcoming?

2. Problem identification: The quest for home and enjoyment (jouir)

According to Bauman the migrant crisis and refugee dilemma desperately need:

(a) Hermeneutics of understanding that is based on the notion of dialogue. Dialogue then in the deeper sense of dia logos: The ability to probe beyond achievement into the flow of meaning and the economy of means (Jaworski 1996:13).

(b) The second challenge is solidarity; i.e. the challenge to embrace the other as partner for dialogue and to invite him/her to an encounter through which one can better understand the intention behind the other's behaviour.

The basic assumption is that in the centre of the crisis features the existential phenomena of dread and un-hope (inespoir). The refugee crisis, together with a global paranoia stirred by terrorist's attacks all over the globe, are fuelling a habitual crisis of fear (Shuster 2016). The tension between insiders and outsiders confronts not only governments all over the globe with the question how to deal with xenophobia (prejudice and fear of the stranger), but specifically communities of faith and religious institutions. It also stirs the question regarding the sincerity of a habitus of care.

Levinas refers to this challenge of dealing with the stranger, as the responsibility to face the Other - the predicament of countenance (Levinas 1963:48). The establishment of this kind of responsibility correlates with what Levinas calls a "metaphysical yearning". It is about a longing that coincides with a commitment to the investiture; it represents a mode of entrustment that eventually implies hospitality, diaconic outreach and liturgy. For Levinas the predicament of the other as stranger, is a spiritual and religious matter that needs urgent attention. Thus, his argument that hospitality resides in the right of the guest that appeals to one's generosity (Abraham receiving three strangers); the plea of Abraham in the Old Testament to step in on behalf of the Other and to spare Sodom and Gomorrah.

The world is a givenness and to receive all its gifts gracefully, contributes to human well-being. Thus, Levinas' emphasis on enjoyment (jouir means to enjoy). We bathe ourselves in the wind, the rain, the water and the sun. All daily activities and bodily functions like breathing, eating, walking, working, reading or making music, are embodied expressions of sheer joy. Human beings should be welcomed in the existential space of life: Life as a hospitable place of home (Heimat).

Being at home (chez soi), is about a kind of interiority wherein the inner being is a safe space for being independent and differentiated from the smothering whole of totality (Levinas 1963). Here one is "saved" from the non-personal threat of massification and global collectivism (Levinas 1963). Being at home, creates a sense of belongingness wherein one can become wholly connected to oneself; saved from just "being there" amongst things without being acknowledged as a unique, human being. The interiority of inner enjoyment, and the sense of "I-am-at-home", become a hospitable space for becoming engaged in the exteriority of the world.

The human quest for being at home and to find a space and place for meaningful existence, should be viewed as one of the most fundamental human rights. The right to be dignified and to experience trust and safety within the existential frameworks for significant daily living. Without any doubt, human displacement challenges the praxis of caregiving and should be viewed by practical theology as a fundamental ecclesial and spiritual matter.

3. Existential thinking1 as paradigmatic framework for the understanding of human displacement

Displacement is in the first place an ontic and fundamental existential problem. According to Paul Tillich (1988: 193-195): Space and place are ontological matters. It touches the how of "to be". Meaningful living implies to have space; every human being needs physical and social space, a place within a structure of values and meanings. Existence means space and place. Not to have space is not to be - striving for space is an ontic feature of significant existence.

With the raise and upcoming of existentialism in the middle of the twentieth century, exponents of existential philosophy made us aware of nothingness and disgust (nausea) (Jean-Paul Sartre 1943, 1968); the limitations of death (Martin Heidegger 1963); and the reality of despair within the awareness of the absurd (Albert Camus 1942, 1965). Due to the contribution of S0ren Aabye Kierkegaard2 (1967) on the interplay between faith and doubt, it became crystal clear, especially during World War II, that the concepts of dread and guilt play a decisive role in the quality of daily living and the human quest for meaning.

Nihilism became a kind of existential repositioning amid an overall conviction that life, due to the factor of negation. is meaningless. Behind radical and total resignation, and the conviction that everything is in vain, lurk specific views that shape expectations about the outcome and quality of life. Existential dread stems from an unarticulated disposition, determined by the despondency of non-hope (apelpizõ): the existential resignation before the threat of nothingness. The antipode of hope is therefore not merely despair, but hopelessness as the disposition of indifferentism, sloth and hopelessness (Bollnow 1955:110). The French philosopher Gabriel Marcel called this desperate situation of dread without a meaningful sense of future anticipation, un-hope (inespoir). The latter is linked to the eventual threat of destructive resignation: désespoir (Marcel 1935:106).

Existential thinking entails more than merely analyses and description of life-threatening structures and tragic events. It articulates the fundamental importance of care (Sorge) (Heidegger 1963: 191-195). Care is an indication of the existential need for direction and purposefulness despite the threat of anguish (Heidegger 1963:194-195).3

Furthermore, the metaphysics of everyday life in existential thinking refers to the fact that life is exposed to an experience of Unheimlichkeit (life is not automatically homely), the total strangeness of beings. "In this unhomely, unfamiliar moment, the mood of anxiety opens up the first questioning movement of philosophy - particularly that big question, which forms the climax of Heidegger's lecture: "Why are there beings at all, and why not rather nothing?" (Blakewell 2016:73). The experience of displacement creates an awareness of not being at home in this world (Unheimlichkeit, Un-zuhause, Heidegger 1963:188-189).4

An ontology of being is concerned about the quality of space (Räumlichkeit); space as an ontological structure of life and the articulation of an existential sense of belongingness (Gehörigkeit) (Heidegger 1963: 110-111). Being is embedded in space and place and oscillates within a dynamic bipolarity of distance (Ent-fernung) and nearness (Näherung) (Heidegger 1963:104105).

To conclude: Displacement is in fact an existential phenomenon framed by the possible threat of a nihilistic outlook on future propositions; an indication of transitional despair and un-hope. It is about the threat of an unhomely disposition; one is dislocated without space and place. Thus, the question: Where are we?

4. Space as dwelling place in the human quest for home

Caregiving to the predicament of displacement has in the first place to get clarity on what is meant by space and place in an existential approach As Tinker (in Lartey 2018: ix) aptly remarked: The primary metaphor for existence is spatial not psychological or temporal. A surprising fact is that the Greeks had already discovered the importance of space and place for our being human. The ancient Greek term chora means space or place.

Bollnow (2011:28) refers to Aristotle who examined in detail the problem of space as linked to place (topos) and time (chronos). What is important for our reflection on the connection between space and meaning is the fact that the value of space depend on position (Bollnow 2011:29). Both place (topos) and space (chora) are interrelated. The Aristotelian concept of space therefore indicates place (topos), location, and position. Everything in space has its natural place. Stemming from the verb "choreo", space as an existential category means primarily to give room, more generally, to give way., to shrink back, and particular to vessels: To hold something, to have room to receive something (Bollnow 2011:30).5

Space is indeed a many-layered concept. Due to the fact that I want to connect a system understanding of the value and meaning of our being human to space as a category of position, orientation and the soulfulness of life, I will thus concentrate on space as dwelling place in our spiritual search and quest for meaning; space then as an existential category, i.e. "experienced space" (Bollnow 2011:216).

In an existential orientation, it is important that space should refer to the intimacy of dwelling. As a human being, we dwell in this world. Dwelling then refers to a form of "trusting-understanding bond" (Bollnow 2011:261).

In space, we should be protected. Bachelard (in Bollnow 2011:281) says: "Space, vast space, is the friend of being."6

5. Displacement and the quest for a hospitable space and place

The following remark of Zygmunt Bauman in Life in Fragments - Essays in Postmodern Morality (1995) is most challenging: Our world is not anymore about my house, city or land (nation), and has become a threatening global entity, is most challenging. Even time encompasses much more than my individual life. However, what is indeed new and unique, is that individualisation, and the fact of global displacement, should become opportunities for personal responsibility.

At stake for pastoral caregiving, is the phenomenon of indifference and the gradual inflation of compassion. Especially when the other does not belong to my family of exclusive circle. In a plural, multi-cultural society, the other has become exposed to the predicament of vulnerability: The facelessness of the staring face without context (crisis of displacement).

Zygmunt Bauman thus proposed: "... the breaking up of certain hopes and ambitions, and the fading of illusions in which they wrapped social processes and the conduct of individual lives alike, allow us to see the true nature of moral phenomena more clearly than ever. What they enable us to see is, above all, the primal status of morality ..." (Bauman 1995:1).

According to Emmanuel Levinas, what should be restored, is the respect for the foreigner in terms of owning hospitality to the foreign outsider (Levinas 1968:61). Violation of "the sacred right of hospitality", is in a sense unforgiveable. The foreigner is rendered as the prototype for a human being without context.

The basic challenge is that life should be reclaimed and reframed as a place and space for the nurturing of human beings. Life should be viewed as a hospitable chora and topos.7

When applied to the discourse on healing in pastoral care, chora shifts the debate from performance and production to care and nurturing in order to support, surround, protect, incubate and to give birth to life. The feminine and mothering dimension strengthens the notion of the fostering of life and the promotion of human identity: Chora is the condition for the genesis of things and being.

The event of giving birth to life, is captured by the old testament's understanding of hospitality. In a pastoral sense, space determines the quality of place, and therefore of our experience of meaning and dignity. To be healed, we need to change the space so that we can live in a very specific place. We can do this even if that place is a hospital, a frail-care unit, or a family home. With reference to a qualitative understanding of space, and the fact that caregiving should represent a space of hospitality, one can argue that the civil society and citizens in local communities should create such an intimate space of inclusivity in order to support people who are to be healed and helped to discover meaning in their topos (where they are located).

Spaces within the settings of civil society, should be created not according to political agendas fuelled by power and control, but by a spirituality of hospitality. The spirituality of space is about meaningful places where people, irrespective of cultural, racial, gender, philosophical and religious differences, can develop a sense of home. Thus, the emphasis on the notion of hospitality as exemplification and exhibition of xenophilia. The pastoral challenge is to replace xenophobia with xenophilia.

Instead of xenophobia, the metaphors of host and hospitality in pastoral caregiving (as exponents of a compassion), should exchange fear for the stranger into philoxenia: The mutuality of "brotherly" love. The theological assumption is that the praxis and pastoral ministry of hope presuppose the praxis of marturia (witnessing presence) and paraclesis (comfort and advocacy). These concepts are intrinsically linked to the virtue of hospitality and the caring outreach of diakonia. Christian hospitality counteracts the social stratification of the larger society by providing an alternative basis for a sense of belongingness, namely the inclusive spiritual principle of koinonia.

Within the intercultural framework of community care, the challenge to caregiving (Sorge) and helping is to provide "hospitals" (xenodochia), safe havens (monasteries of hope, places of refuge) where threatened people can become whole again. "To be moral is to be hospitable to the stranger" (Ogletree 1985:1).

One should acknowledge that it is difficult to translate a spirituality of hospitality into terminology of our contemporary society wherein hospitality is often identified with the civic services and domestic spheres of social welfare. Hospitality is often robbed from its spiritual character of caritas and has become diminished to, mostly, an ordinary secularised expression of human wellbeing. However, Derrida (2001:16-17) asserts: "Hospitality is culture itself and not simply one ethic among others. Insofar as it has to do with the ethos, that is, the residence, one's at home, the familiar place of dwelling, as much as the manner of being there, the manner in which we relate to ourselves and to others, to others as our own or as foreigners, ethics is hospitality; ethics is entirely coextensive with the experience of hospitality, whichever way one expands or limits that". To a certain extent, hospitality reintroduces a kind of social paradox: Unconditional loves becomes conditional; it focuses conditionally on the outsider in order to make outsiders insiders even beyond the categories of juridical equality; it functions outside of right, above what is juridical (Derrida 2001).

6. Displacement within a practical theology as "life science"

Moltmann (2015) in a sermon on joy, makes the following bold statement: Religion should not thrive on the misfortune of people, religion as the sigh of the oppressed creature, an opium of suffering and desperate people (Karl Marx). Religion should rather be "necessary" and life-inspiring. "In truth, religion is the feast of life, useless but joyful" (Moltmann 2015:4).

In fact, one could argue that the concept of life has even become a kind of keystone concept to describe the praxis implications of theology in contemporary society. Practical theology should rediscover itself as fides quaerens vivendi - faith seeking meaningful structures/modes for humane living; life as explication of hospitality; practical theology as a life-bringing source (Kumlehn 2011:4) for installing a vivid hope and sense of meaning. In an introductory article on the edition of practical theology as a kind of life science. Thus, my basic conviction that practical theology and caregiving are fundamentally engaged in life events with the view of healing and wholeness: cura animarum as cura vitae (Louw 2008).

In order to reframe the ecclesial praxis of ministry to displaced people, the first step is the thorough hermeneutics of contextual and cultural understanding. Before one starts with engagement, intervention and counselling, one needs to get clarity on the categories at stake. Hermeneutics describe a sensitivity that helps caregivers to understand the complexity of displacement. It should prevent an approach that pretend to come up with easy solutions. Just to be there with them (the art of pastoral presenting8), with displaced people wrestling with the question "Where are we?", helps one to start building trustful relationships. Just to do this, caregivers needs existential and theological language and grammar to interpret complexities. And this is what a diagnostic approach is about.

7. Towards a hermeneutical design for a diagnostic chart: Spiritual healing and the seeing of the bigger picture in a theologia practica

One should accept the fact that there exists no easy answer or instant solution to the predicament of displacement. The graphic design, thus, does not feature as a kind of solution. What I am proposing is an understanding of the systemic existential dynamics at stake. The logic behind a hermeneutical approach is that an understanding of complexities helps one to consider different options within concrete existential and local settings. To start seeing the bigger picture, is a form of healing and hoping.

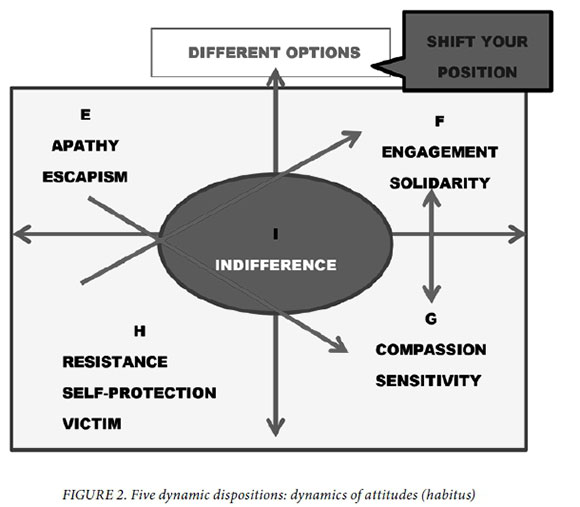

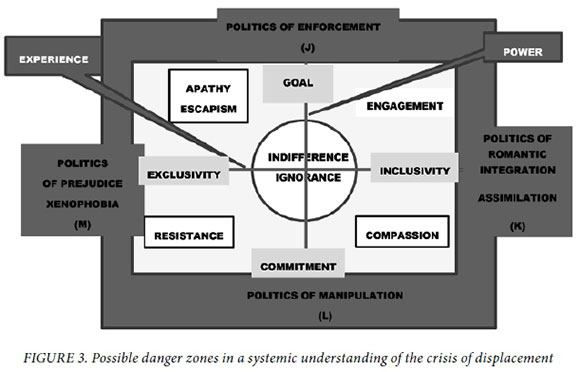

It should be made clear that a diagnostic chart is not about classification as in many medical, psychiatric and psychological models. It is merely about gaining a balanced perspective. It helps to depict the dynamics of a wholistic approach. In this regard, all the different bipolar tensions (See below figure 1: A, B, C, D) and possible positions (E, F, G, H, I) (figure 2) describe a kind of theologia practica wherein human habitus/disposition refers to the interplay between action, intention, motivation, paradigmatic framework of thinking and ethos (enfleshment of morality and convictions/ belief systems).

The rationale in the first figure is that the notion of a homely space and place is framed by four bipolarities that constitutes directives for coping with the predicament of displacement. To move from un-hope into meaningful options, the following directives should be explored:

A: Decision-making and goal setting. Displacement implies limitations. What cannot be changed should be accepted. However, decision-making should be taken seriously. The first step is then to set new goals and to explore different options for discovering alternatives.

B: Re-connection. Displacement is about disconnection. Therefore, the following question: How and where can I be reconnected so that one can regain a sense of belongingness? Where do I belong? These questions express the need for trustworthy relationships.

C: New commitments. Displacement brings about confusing disorientation, stagnation and passivity. Displaced human beings should start to make new commitments so that they could become motivated and challenged to act in new, appropriate ways.

D: Reframing of identity (differentiation). Displacement brings about an identity crisis: Who am I? Where am I?

The spaces within the four quadrants, represent four possible positions (attitudinal options).9 Right in the middle is a fifth option. (See the 5 basic options, attitudes or positions possible - E, F, G, H, I) (figure 2).

Options should not be considered in terms of moral issues, namely whether a specific position is right or wrong. Options are more about the aesthetic question, namely whether they are appropriate or not. They just describe existential realities regarding our being human. Thus, the following options: E: apathy and a kind of denial, withdrawal; F: solidarity (identifying with the other), engagement and the taking of actions in terms of goals and values, philosophies of life; G: compassion due to sensitivity and outreach; H: resistance and confusion, a kind of disorientation and attempt to maintain oneself and to protect what is dear to oneself. Eventually one runs the danger of becoming a victim of displacement. When the condition develops into a kind of catch-22 situation, it leads easily to indifference and the neutral stance of ignorance (I).

The advantage of the chart is that it shows the dynamics of different positions (habitus). And healing is about movement and change. The chart, thus, opens options for movement so that when one becomes stuck, fixed positions can become unlocked. In general, the movement of position/ habitus starts in one quadrant and then moves into the opposite direction. For example: From H into F and then down into G; from E into G and then up into F (see figure 2). The reason is that position F (engagement and solidarity) could be viewed eventually as the healing of H (victim, resistance and self-protection). G (compassion and sensitivity) can opt as the healing of E (apathy and escapism/withdrawal). Nevertheless, all the positions should always be interconnected at the same time and not be viewed as separated and isolated from one another (seeing the bigger picture). I (indifference) needs both F and G to move from a neutral stance into constructive repositioning. F and G are supplementary to one another and represents constructive options. E and H feeds one another in a destructive manner and contribute to further disorientation and experiences of helplessness and hopelessness.

One must consider different possible danger zones (J, K, L, M) (figure 3) as well. The function of the chart is to reveal the complexity of the phenomenon of displacement. The fact is, life is never straightforward. Goal setting and values contribute to motivation and possible action. But at the same time, goal setting and decision-making can easily develop into the power play of enforcement and violent oppression (J). Inclusive re-connection runs the danger of an underestimation of cultural complexities.

It can create a very romantic sense of belongingness, but in the meantime attempts of integration is merely a subtle way of cultural assimilation or a smothering inculturation (K). Commitment can derail into the politics of manipulation and emotional stress and pressure (L); while the necessity of differentiation can lead to discriminatory exclusivity based on prejudice and xenophobia (M).

The dynamics of positioning and repositioning (dynamics of habitus), opens options for change. People operating from the position of resistance should be motivated to move into the opposite quadrant, namely to a position of active engagement. When this position is established, one should move down to the supplementary position of compassion to understand what a pastoral sustainability is about. People operating from a position of apathy and escapism, should move into a position of compassion and then into a position of engagement, because compassion without engagement becomes easily implausible, untrustworthy and artificial. The most problematic position is one of indifference: The position of resisting any form of decision-making, commitment, sense of belongingness or acknowledgement of improper and irresponsible behaviour.

The point in this hermeneutical approach is that habitus is a "mixture phenomenon" (complexification): Not one position is so to speak "pure" and, thus, without the impact of the bipolar dynamics of the other (A, B, C, D as networking entities). A human disposition is always a mixture of many submersed positions due to the dynamic networking complexity of habitus (E, F, G, H, I).

The chart reveals that the challenge to welcome strangers and migrants into communities and congregations are without any doubt difficult and complex (Jacobs 2018: 195-210)10. For example, the Angela Merkel's Willkommenskultur ("welcome culture" to the incoming refugees) (Vick 2015), is framed and determined by all five positions simultaneously. Sometimes it will be necessary to move into the direction of D with a mixture of E and H (the cold and shadow side of habitus) to address the violent behaviour of perpetrators; demarcation and differentiation then becomes obligatory. However, one should always bear in mind that the constructive direction is determined by choices about F and G (the warm and sunny side of habitus). In some cases, it becomes paramount to avoid violence and to move temporarily into apathy (E) to gain perspective and to debrief.

It is important to note that F (engagement) is never without its shadow side: E (apathy). Even compassion (G), never operates without the existence of the shadow side of H (resistance). Human behaviour within the dynamics of repositioning is always in flux and never fixed. Its dynamics reflects the complexity of paradox. Human positions and attitudes within relational networking are compiled by the complexity of different nuances of dispositions.

Taking the outline of the previous charts into consideration, the intriguing question surfaces: How do one connect these charts with a spiritual and theological interpretation that can contribute to compassionate healing and the diagnostic, ecclesial hermeneutics of welcoming and hospitable homecoming. The eventual challenge is how to connect the above described existential categories to a systemic and hermeneutical mode of pastoral diagnostics.

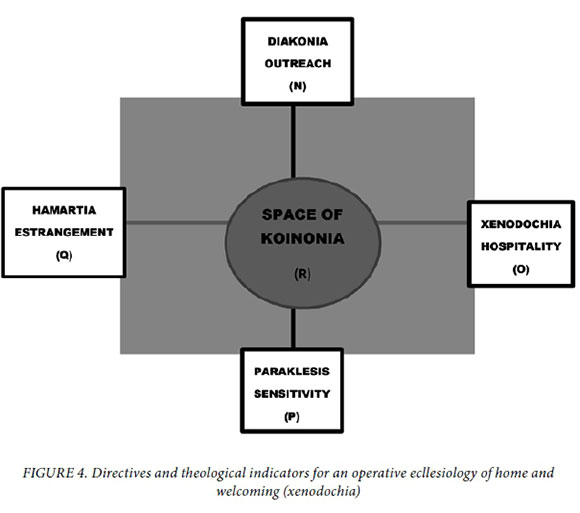

8. Spiritual indicators for a theology and ecclesiology of home (ecclesial welcoming)

With reference to pastoral theology and caregiving within an operative approach to the function of communities of faith (operative ecclesiology), the following practical theological directives and spiritual indicators for a theology of home can be identified: Diakonia as unconditional love and outreach to the plight of the refuges; xenodochia as an embodiment of hospitality and the creation of a safe space of belongingness; paraclesis as the enactment and embodiment of comfort and the challenge to advocate for people in disadvantaged positions; xenophobia as the natural fear for the stranger (estrangement). In this regard, the theological concept of hamartia comes into play, namely sinfulness as an indication that human beings don't live life according to their destiny and calling, namely to love God and fellow human beings, unconditionally. The notion of sin in this context literally means to miss the mark or target (failure and estrangement).

All these 4 pointers (diakonia, xenodochia, paraclesis, hamartia) are exponents of the cohesive factor in an operative ecclesiology of home, namely a mutual sense of fellowship and belongingness as determined and created by koinonia. From a practical theological and Christian spiritual point of view, one can say that human beings are therefore not connected to one another due to race, culture or gender, but due to our corporative sense of belongingness to Christ (amazing grace and the faithfulness of a covenantal God).

Diakonia, xenodochia, paraclesis, hamartia (see figure 4 - N, O, P, and Q) could be viewed as dynamic, practical theological indicators for an operative ecclesiology of home and hospitable space. Homely welcoming implies all four directives. The central factor in such an ecclesial space and place is koinonia (R) as the core coherence factor for ministerial actions of involvement and engagement. Koinonia creates a fellowship that is inclusive; it operates from the ethos of sacrificial and unconditional love. Koinonia is about the ecclesial space and liturgical celebration wherein a sense of belongingness is created that makes hospitality to the stranger a sacramental event of concrete welcoming.

9. Conclusion: On seeing the bigger picture in the refugee and migrant crisis

The basic argument is that a practical theology of compassionate caregiving,11with the assistance of a hermeneutical and diagnostic tool to understand the crisis and dilemma of homelessness and displacement, should come up, not with a solution but with an operative approach and hermeneutical engagement that challenges pastoral caregivers to become kinds of "in-between persons": moving between pity and fear, interpenetrating the paradoxical position between helplessness/hopelessness and healing/hope by means of the perichoresis of compassion - making room (home) for the homeless (xenodochia).

Instead of xenophobia, the metaphors of host and hospitality in pastoral caregiving (as exponents of a theology of compassion), exchange fear for the stranger into philoxenia: The mutuality of "brotherly" love. The praxis and ministry of hope presupposes the praxis of marturia (witnessing presence) and paraclesis (comfort and advocacy). It is intrinsically linked to the virtue of hospitality and the caregiving outreach of diakonia. Christian hospitality counteracts the social stratification of the larger society by providing an alternative basis for a sense of belongingness, namely the inclusive spiritual principle of koinonia.

Compassion displays the hope of unconditional love and pity. Compassion in Christian spirituality is not about a fleeting emotion of empathy; it is about a new state of being and ethos of sacrificial love; it displays the mindset of Christ's vicarious suffering on behalf of the other. As an expression of koinonia, compassion exemplifies a hospitable place and space for displaced human beings - even for dislocated perpetrators.

Bibliography

Baudrillard, J 1994. Simulacra and Simulation. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. [ Links ]

Bauman, Z 1995. Life in Fragments - Essays in Postmodern Morality. Oxford/Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers. [ Links ]

Bauman, Z 2016. Nationalismus ist ein Ersatz. Spiegel-Gespräch. In: Der Spiegel, Nr. 36/3.9.2016, 122-125.

Blakewell, Sarah 2016. At the Existentialist Café. Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails. New York: Other Press. [ Links ]

Bollnow, OF 1955. Neue Geborgenheit. Das Problem der Überwindung des Exsistentialismus. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. [ Links ]

Bollnow, OF 2011. Human Space. London: Hyphen Press. [ Links ]

Camus, A 1942. Le Mythe de Sisyphe. Essay sur Labsurde. Paris: Gallimard. [ Links ]

Camus, A 1965. The Myth of Sisyphus. London: Hamish Hamilton. [ Links ]

Derrida, J 2001. On Cosmopolitanism and Forgiveness. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Gorney, C 2008. Mexico's Other Border. [Online] http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2008/02/mexicos-southern-border/cynthia-gorney-text [Accessed: 16/11/2015].

Haacker, K 1978. Samaritan. In: C Brown (Ed.) The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, Vol. 1. Exeter: Paternoster Press, 449-466. [ Links ]

Heidegger, M 1963. Sein und Zeit. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag. [ Links ]

Jacobs, RM 2018. Congregational Welcome of Migrants. In: D Schipani, M Walton & D Dominiek (eds.), Where are We? Pastoral Environments and Care for Migrants. Düsseldorf: Society for Intercultural Pastoral Care and Counselling (SIPCC), pp.195-210. [ Links ]

Jaworski, J 1996. Synchronicity. The Inner Path of Leadership. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. [ Links ]

Kempen, Martin 2015. Coaching als abduktiver Prozess vor dem bleibenden Geheimnis. Die Theorie U aus pastoralpsychologischer Perspektive. Doctoral Dissertation. Frankfurt am Main Philosophisch - Theologische Hochschule, Sankt Georgen, Institut fur Pastoralpsychologie und Spiritualität. [ Links ]

Kierkegaard, S 1967. The Concept of Dread. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Kumlehn, M 2011. Einleitung: Praktische Theologie als Lebenswissenschaft?! In: T Klie, M Kumlehn, R Kunz, T Schlag (hrsg.), Lebenswissenchaft Praktische Theologie?! Praktische Theologie im Wissenschaftsdiskurs. Band 9. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter, pp. 1-8. [ Links ]

Lartey, E 2018. Foreword. In: D Schipani, M Walton & D Dominiek (eds.), Where are We? Pastoral Environments and Care for Migrants. Düsseldorf: Society for Intercultural Pastoral Care and Counseling (SIPCC), pp. ix-xi. [ Links ]

Levinas, E 1963. Difficile Liberte, Essais sur le Judaisme, Paris Albin Michel. [ Links ]

Levinas, E 1968. Quatre lectures talmudiques, Paris: Les Editions de Minuit. [ Links ]

Louw, DJ 2008. Cura Vitae. Illness and the Healing of Life. Wellington: Lux Verbi. [ Links ]

Marcel, G 1935. Être et Avoir. Montaigne: Ferned Aubier. [ Links ]

Marcel, G 1962. Homo Viator. Introduction to Metaphysics of Hope. London/Chicago: Harper &Row. [ Links ]

Moltmann, J 2015. Christianity: A Religion of Joy. Tübingen: Pamphlet by author. [ Links ]

News Ticker 2018. US to Slash Refugee Numbers. In: Time, October 1, p.9.

Polak, R 2018. Practical-Theological Reflections on the Migrant Crisis in Europe. In: D Schipani, M Walton & D Dominiek (eds.), Where are We? Pastoral Environments and Care for Migrants. Düsseldorf: Society for Intercultural Pastoral Care and Counseling (SIPCC), pp. 19-52. [ Links ]

Sartre, J-P 1943. L'Être et le Néante. Paris: Gallimard. [ Links ]

Sartre, J-P 1968. Being and Nothingness. New York: Citadel Press. [ Links ]

Schipani, D, M Walton, D Lootens 2018. Where are We? Pastoral Environments and Care for Migrants. Düsseldorf: Society for Intercultural Pastoral Care and Counseling (SIPCC) [ Links ]

Shuster, S 2016. Fear and Loathing. In: Time, vol. 187, n0 3, pp. 28-33. [ Links ]

Tillich, P 1988. Systematic Theology, Vol. 1. Chicago: University Press. [ Links ]

Vick, K 2015. Angela Merkel. Chancellor of the Free World. In: Time, vol. 186, no. 25-26, pp. 26-51. [ Links ]

Walton, M 2018. Recovering Context. Parameters of Pastoral Care with Migrants. In: D Schipani, M Walton & D Dominiek (eds.), Where are We? Pastoral Environments and Care for Migrants. Düsseldorf: Society for Intercultural Pastoral Care and Counseling (SIPCC), pp. 171-182. [ Links ]

Wilson, Colin 1966. Introduction to the New Existentialism. London: Hutchinson & Co. [ Links ]

1 According to Wilson, the "new existentialism" goes further than Sartre and Heidegger. "It deals with the most immediate problem we can experience, with our actual living response to everyday existence: a territory that has so far been regarded as the concern of the novelist or poet" (Wilson 1966:160). What should be explored is the capacity for imagination within the parameters of freedom (Wilson 1966:165). "The use of imagination and intellect brought man his greatest vision: of the idea lived at a level of intensity and purpose that is impossible for the mere animal" (Wilson 1966:164).

2 Much of Kierkegaard's philosophical work deals with the issues of how one lives as a "single individual", giving priority to concrete human reality over abstract thinking, and highlighting the importance of personal choice and commitment. Within the quest for authenticity in Christian spirituality he deals with the art of Christian love. He was extremely critical of the practice of Christianity as a state religion, primarily that of the Church of Denmark. His psychological work explored the emotions and feelings of individuals when faced with severe life choices.

3 "Dagegen ist der Drang "zu leben" ein "Hin-zu", das von ihm selbst her den Antrieb mitbringt" Heidegger 1963:195).

4 "Dagegen ist der Drang "zu leben" ein "Hin-zu", das von ihm selbst her den Antrieb mitbringt" Heidegger 1963:195).

5 Choreo is a verbal derivative of choros or chora, indicating an open space or land. As an intransitive, it means, "to give room." In an extended and metaphorical sense, it can refer to the intellectual and spiritual capacity of being able "to understand." In this sense, space functions as a container of meaning. Used in this way chora becomes an indication of how humans fill space with values, perceptions and associations in order to create a dynamic relational environment and systemic network of interaction where language, symbol and metaphor shape the meaning and discourses of our life.

6 In his book, Simulacra and Simulation, Baudrillard (1994:3) refers to the space of simulation within the social media.

7 According to the Platonic understanding, chora is a nourishing and maternal receptacle, and is related to topos, a, definable place of human encounter. Topos can also be linked to what one might call "a theology of omnipresence which goes hand in hand with the sublimation of cultic observance" (Haacker 1978:461).

8 "Presencing is a blended word combining sensing (feeling the future possibility) and presence (the state of being in the present moment) (Kempen 2015:140)

9 They could help one to understand that, the refugee crisis should not be viewed as a checkmate situation that leads to despair. The different options open different perspectives and options.

10 See the following remark on the practice of welcoming (Jacobs 2018:199): "Two dominant culture congregational members emphasized the importance of being willing to be uncomfortable or the capacity to tolerate differences as a key component in welcoming the other."

11 Compassion as way of life, and new state of being and mind (ethos), is about a habitus of caregiving, hope-providing and comfort; it happens in human encounters as a spontaneous infiltration of mhr (in close connection to the root nnh) into systemic events; it embodies the passion (êhtap) of Christ within the dynamics of human relationships.