Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

On-line version ISSN 2413-9467

Print version ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.4 n.2 Stellenbosch 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2018.v4n2.a24

GENERAL ARTICLES

A practical theology of bereavement care: Re-ritualization within a paradigm of "comforting presence"

L GibsonI; DJ LouwII

IStellenbosch University, South Africa 18086373@sun.ac.za

IIStellenbosch University, South Africa djl@sun.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The investigation focuses on a concern for the marginalization of bereaved human beings in the context of cultural shifts now shaping twenty-first century pastoral care. The article advocates for a practical theology of bereavement to aid in nurturing care and eudaimonic well-being (including both vocational pastors and funeral directors) within the paradigmatic framework of a theopaschitic understanding of compassion (oiktirmos). The investigation examines the growing threat of deritualization - a public openness to revise, replace, minimize the significance of, and even eliminate or avoid long-held funerary rituals to assist in the adaptation of loss. The notion of re-ritualization is operationalized as an intentional act of restoring and re-engaging in creative and meaningful ritual forms that give symbolic expression to significant thoughts and feelings of the bereaved within a social ethos that is no longer committed to a conventional or fixed approach to ritualization. In order to facilitate a process of re-ritualization, bereavement care is linked to the notion of "comforting presence".

Key words: Grief and mourning in pastoral caregiving; funeral directors; deritualization; resilience; re-ritualization, comforting presence; practical theology of bereavement; theology of compassion; theopaschitic thinking

1. Introduction

The bourgeoning field of practical theology often locates its pastoral identity through interdisciplinary conversations of concern for the marginalized in life (Cahalan & Mikoski 2014; Miller-McLemore 2014). Indeed, there are now vibrant conversations ongoing in academia that are developing highly differentiated practical theologies of race, gender, nationality, sexual orientation, economic status, and mental health, to name just a few (Reddie 2009; Radford 2017; Lartey 2013; Fegan 2017; Atherton 2015; Pierce 2007). The current investigation focuses on a concern for the marginalization of bereaved human beings in the context of cultural shifts now shaping twenty-first century pastoral care. For many, the estrangement of bereavement leaves one feeling lost, alone, and fearful, in a wilderness of grief (Wolfelt 2007). Certainly the weight of existential woundedness from the internalization of loss, makes bereavement a compelling form of marginalization for practitioners of practical theology today.1

The aim of the current article is to advance a constructive dialogue regarding the normative human experience of searching for meaning and hope in the sacred realm of death, grief, and mourning. This article will initially engage in a descriptive task of practical theology (i.e. "what is going on"), before moving to a pragmatic task (i.e. "how might we respond") (Osmer 2008). To be sensitive to both the spiritual dimension of meaning and the anthropological dimension of human dignity (Louw 2014), the current investigation suggests that a practical theology of bereavement could improve the understanding and enhance the skills of professionals committed to nurturing care. Bereavement caregiving occurs across a continuum of pastoral care. Traditionally, pastors in local faith communities are tasked with the responsibilities of bereavement caregiving, and to a lesser extent, the involvement of funeral directors in supportive roles are considered. While both of these caregiving professions have historically worked together in a mutual collaboration of care for bereaved families and individuals (i.e. a team approach), in this article, the role of funeral directors will be emphasized to highlight their meaningful work in the processes of nurturing care (Beardsley 2009:239; Bregman 2010; Gibson 2005).

Two essential concepts that frame the investigation will be examined to establish a better understanding of the current context of bereavement care: (1) the growing threat of deritualization and (2) the promising shift from resilience theory to re-ritualization. A new theological paradigm for bereavement caregiving, hereinafter referred to as a comforting presence, will be proposed with deference to a meta-theoretical framework for compassion (oiktirmos) (Louw 2015a; Davies 2001; Farley 1983). In short, the article will advocate for a practical theology of bereavement within a narrative approach to nurturing care and eudaimonic well-being (Sedikides et al 2016).2

2. First key concept: The growing threat of deritualization

Deritualization is contributing to potential distress in processes of grieving. As a key term for the current investigation, deritualization broadly denotes the growing trend of a public openness to revise, replace, minimize the significance of, and even eliminate or avoid long-held funerary rituals to assist in the adaptation of loss (Gibson 2016). In a description of high impact issues facing professional funeral service, Long and Lynch (2013:157) describe "the curious downsizing of funeral rituals" and "the increasing number of people who specify "no service" to mark their deaths". If these tendencies reported by funeral professionals proliferate and point to less formal modes of "saying goodbye", how will vocational pastors respond if the use of traditional religious rituals are increasingly becoming outdated? Moreover, if funeral caretaking implies more than being a business (i.e. merely performing a service for monetary compensation), how can it support a "spirituality of death and dying" and cooperate with local communities of faith with their bereavement liturgies in order to foster wholeness and spiritual healing in processes of mourning (Louw 2015a; Hoy 2013)?

Many bereavement caregivers are alarmed by a growing trend towards deritualizing death (Irion 1991; Wolfelt 2005; Taylor 2011a). Increasingly, many people are choosing to have their deceased loved ones removed from the place of their death and cremated with minimal or no ceremonies, or buried without any traditional funeral services that accompany the dead. Taylor opines: "the elimination of the funeral by more Americans every day suggests that public confidence in their efficacy is lacking" (2011b:3). In fact, the National Funeral Directors Association (NFDA) recently reported that only 39.5% of respondents feel that having a religious component in a service is very important to cope with death (Gillespie & Defort 2017), marking a steady 10% decline just in the past five (5) years alone (see Figure 1).

This decline is not surprising given the growing percentage of Americans who do not identify with any specific sectarian tradition. The Pew Research Centre reported that over 22.8% of Americans no longer identify with a specific religious tradition (2012; 2015). However, this demographic is not limited to nonbelievers, as most people without a specific religious affiliation still embrace various views of God. Nevertheless, the religiously unaffiliated represent a growing segment of people who are less observant of common religious traditions in the United States. Over the past ten years, a majority of the religiously unaffiliated (78%) report leaving their traditional religious identity in adulthood (Lipka 2016). Subsequently, the perceptions of this demographic regarding the value of traditional funerary rituals are being greatly diminished.

The cultural trend away from meaningful religious ceremonies as a means to cope with loss is a growing concern for bereavement caregivers typically provided by a team of funeral directors and vocational pastors. Some may interpret deritualization as a negative shift in how people today perceive the value of human life. At minimum, what is clear is that the deritualization trend is symptomatic of changing attitudes towards the effectiveness of traditional religious funeral rituals to bring about real comfort and eudaimonic well-being to the bereaved in times of loss.

Conversely, yet closely related to the trend of religious ritualistic downsizing, is the growing preference toward simple cremation with no ceremony rather than traditional burial with ceremony. In a recent report compiled by the NFDA, the cremation rate finally eclipsed the burial rate for the first time in the history of the United States (NFDA 2017). According to the report, the cremation rate in 2015 was 47.9% and the burial rate was 45.2%, with the trend expecting to continue through 2035 with cremation rates exceeding 78.0% (see Figure 2).

The current investigation noted, however, that just because a family chooses cremation does not mean that they cannot receive comfort and support through meaningful rituals (Starks 2014). Some families who choose cremation still have the deceased body of their loved one embalmed and prepared for a private farewell viewing before being cremated. Moreover, some families who choose cremation schedule a time for receiving friends to mobilize their community of support. Further, families who choose cremation may also decide to have a traditional funeral ceremony with the deceased body present before going to the crematory, or even a memorial service without the deceased body present.3 There are certainly a variety of final disposition options for cremated human remains, including being interred in the burial grounds of a cemetery (just like traditional caskets/ coffins), being entombed in an above ground mausoleum or columbarium niche, and even being scattered with a ceremony in a cemetery's nature garden or other meaningful location.4 What is clear is that cremation does not preclude traditional religious funerals or burial rituals (Beck & Metrick 2009).

Regardless of the numerous options available for families choosing cremation, the fact is that many are increasingly choosing to opt for a simple or direct cremation with minimal or no funeral ritual at all.5 How are these families receiving adequate support to process their grieving? A direct cremation typically includes a funeral establishment picking up the deceased body from a nursing home, hospital, or personal residence, attaining the necessary documentation and authorizations, taking the body to a crematory in a rigid cardboard container, completing the cremation, and shipping the cremated remains to the family - often without body preparation, ceremony, and possibly even without the participation of clergy. In 2015, the NFDA reported that a direct cremation (i.e. cremation without a final viewing of the deceased and without formal ceremonies) had grown to account for 32% of all cremations in the U.S., with no signs of decline (NFDA 2017).6

Given the growing preference today for the bereaved to go through the grief experience without traditional religious ceremonies for support, pastoral care providers are increasingly concerned with the potential lack of nurturing care (Gibson & Troyer 2017a). This unprecedented trend toward deritualization stands in sharp contrast to the ubiquitous practice of funeral ceremony and ritualistic burial occurring throughout antiquity. What appears problematic about the current trend toward deritualization is that every culture throughout human history up to the present time has attended to the care and disposition of their deceased, which included funerary ritual and burial ceremony with the support from a local faith community (Laderman 2003:xvi). Despite the variety of particular funerary practices and religious beliefs in early human societies, the connection between humanity, death rituals, and faith have been solid throughout a very long and complex history (Pettitt 2011; Van Gennep 1960).

Funeral ritual and ceremony are an intrinsically human phenomenon designed as an essential means to care for the bereaved. That people possess a symbolic capacity, such as the ability to perform ornamental funeral and burial rituals, is a defining characteristic of humanity. Yet, if final ceremonies reveal a great deal about human society, what does a dearth of final ceremonies signify? That is, what happens if a preponderance of human beings decide that death rituals are no longer valued for bereavement care and spiritual well-being? There appears to be a paucity of research on the anthropological and spiritual consequences of the deritualization of death. Kastenbaum (2004:5-6) offers some insights into the seriousness of this recent trend:

The spiritual health of a society can be evaluated by the vigour with which it continues to perform its obligations to the dead. Something crucial to the survival of a society is endangered when the living are unwilling or unable to continue customs and rituals intended to regulate relationships with the dead.

3. Second key concept: The promising shift from resilience to re-ritualization

Deritualization proposes a significant issue for caregivers concerned with the marginalization of the bereaved who may not receive the comfort they need. At the same time, there are reasons to believe that all hope is not lost for care-seekers needing support in times of grief. In his landmark text, The other side of sadness: What the new science of bereavement tells us about life after loss, George A. Bonanno argued that most people are naturally resilient when it comes to loss. Though this may seem counterintuitive, Bonanno explained that resilience is a fact of human anthropology (2009:24):

Most bereaved people get better on their own, without any kind of professional help. They may be deeply saddened, they may feel adrift for some time, but their life eventually finds its way again, often more easily than they thought possible. This is the nature of grief. This is human nature.

According to empirical findings, only 10 to 15% of bereaved people are likely to struggle with prolonged grief (Bonanno 2009:96). This number, while surprising to some, has been regularly regarded by other clinicians and counsellors as well. For example, Alan D. Wolfelt, the Director of the Centre for Loss and Life Transition, explained: "In my experience, a small percentage - fewer than ten percent - of grievers suffer from what I call 'complicated mourning' " (Wolfelt 2006:24). According to one study, "doing well after a loss is not necessarily a cause for concern, but rather a normal response" (Boemer, Wortman, and Bonanno 2005:72).7

Contemporary bereavement research maintains that resilience is the norm, not the exception for grieving individuals and families (Bonanno 2009:47). In fact, resilience theory is not described as a particular style of normative grieving, but simply the way most people, with or without the help of pastors and funeral directors, adapt to loss. In this way, resilience theory seems to imply that regardless of how little outside care and support one receives following a loss, there is an internal floor mechanism built in to the human mind that helps individuals cope with loss. Empirical studies suggest that most people, when faced with a significant loss of a loved one, do whatever can be done to get by and adapt to the new context without the loved one. Bonanno called this "whatever it takes" approach, coping ugly (2009:78-79). "Coping ugly" is an insightful phrase that describes what others refer to as pragmatic coping - "when bad things happen, people often find the strength to do whatever is necessary to get back on track" (Bonanno 2009:79).

In sharp contrast to the standard model of mourning that argues for necessary stages for grief resolution with a looming threat of pathology if grief is not adequately worked through (Kelley 2010), the contemporary concept of resilience explains that although grief is not a one-dimensional or uniform experience, people are largely equipped to deal with their grief and adapt to their own loss. Bonanno contended: "the good news is that for most of us, grief is not overwhelming or unending. As frightening as the pain of loss can be, most of us are resilient" (Bonanno 2009:7). In short, as a basic human response to loss, grief "is something we are wired for, and it is certainly not meant to overwhelm us" (Bonanno 2009:7).8

To be clear, resilience theory, as an advanced concept in contemporary bereavement psychology, does not diminish or ignore the real pain and suffering that often marginalize the bereaved following a significant loss. Instead, resilience theory provides a hopeful message for many bereaved people, recognizing that 85-90% of all people can adapt to loss without lingering problems.9 Despite the early theories of bereavement that emphasized a series of predictable and necessary stages of grief (KüblerRoss 1969), in truth, the bereaved actually "cope well with loss because we are equipped - wired, if you will - with a set of in-born psychological processes that help us do the job ... our experience of the emotion comes and goes. It oscillates. Over time the cycle widens, and gradually we return to a state of equilibrium" (Bonanno 2009:198).

The current investigation suggests that a word of caution is necessary when considering the impact of resilience on bereavement care (Gibson & Troyer 2017a; Gibson 2016; Doka 2013; Hoy 2013).10 However accurate resilience theory may be in terms of the bereaved making it through a significant loss with or without the aid of traditional religious ritual forms, it seems inadequate to fully address the human proclivity to be comforted and search for meaning and hope during a loss (i.e. eudaimonic well-being). To be fair, most resilience advocates are not suggesting that death rituals have no existential value for the bereaved. In fact, resilience still allows space for the on-going transformative power of rituals to change people.11 What is needed therefore is not a return to tired rituals people no longer find meaningful, but perhaps a new and relatable way to look at death rituals to facilitate eudaimonic well-being (Ryan and Deci 2001).

The current investigation suggests that there is a real opportunity for practical theology to demonstrate how the bereaved can continue to benefit from nurturing care, despite the changing perceptions in the value of funeral rituals. To be sure, practical theology recognizes that there is a profound difference between merely getting on with life after grief and truly addressing emotional wounds to foster human wholeness. There is a qualitative spiritual dimension often overlooked in bereavement care that can drive human resilience. What is needed is for bereavement caregivers, including funeral directors and vocational pastors, to begin reframing their approach. The point is not to advocate for a return to an outdated mode of ritualization. Instead, perhaps now is the time for bereavement care providers to rethink how death rituals of old can be reshaped into something of new relevance and meaning for the bereaved.

For the current study, it may be helpful to note that bereavement caregiving within a traditional clerical paradigm often maintained a fairly-static and linear process. Funeral homes and local churches throughout much of the twentieth century maintained such a high degree of cultural authority that funerals were largely standardized occasions. The chief assumptions were that there was both a necessary sequence of ritual events and a prescribed hierarchy of services that delivered the appropriate care to the bereaved (Irion 1966). When a death occurred, families automatically called their local pastor and their local funeral director, as both caregivers knew just what to do to assist a family "in the right way." Funerary care was largely standardized in terms of embalming and dressing the deceased body, viewing the deceased body, visiting with friends and family, meeting together for a funeral service, processing to a cemetery, offering a brief committal ceremony and prayer, and ending with a final burial - what Garces-Foley referred to as the "embalm-and-bury model" (2010:17).

In the past, vocational pastors and funeral directors placed the highest measure of effective care on the funeral sermon. This is evident as early as 1954, when Irion stated that the two (2) main functions of a funeral were: 1) to engage in a therapeutic process of mourning, and 2) to present the Christian faith (1954:8). For many decades, a kerygmatic proclamation, above all else, was paramount in pastoral bereavement care (Thesnaar 2012; Louw 1998). This type of sequence and hierarchy is illustrated in Figure 3 below.

In terms of a traditional mode of ecclesiology, funeral directors and clergy worked side by side, each doing clearly delineated roles that were steeped and widely accepted into the consciousness of society. Yet, as Taylor reported (2011b), by the end of the twentieth century, the cultural authority of the funeral industry as well as the religious authority of faith communities had largely been diminished. As a result, the prescribed sequence and hierarchy of care are now both being challenged.

As evidenced by deritualization, the current investigation argues that the use of a traditional hierarchy of funeral rituals is on the decline. As secularism grows and impacts the perceptions of traditional modes of leave-taking, care-providers must reengage care-seekers through more relatable and supportive ritual forms - a process referred to in the current investigation as re-ritualization. Re-ritualization is operationalized as an intentional act of restoring and reengaging in creative and meaningful ritual forms that give symbolic expression to significant thoughts and feelings of the bereaved within a social ethos that is no longer committed to a conventional or fixed approach to ritualization. Components of ritualization are no longer fixed or predefined, as in traditional approaches, but represent various modes that provide a means by which families can meaningfully share the story of one's life across a spectrum of pastoral care initiatives. Fortunately, the current article contends that the field of practical theology holds much promise to solidify what it means to appropriate re-ritualization in effective modes of contemporary bereavement care.

4. A paradigm of comforting presence

Moving out of a descriptive task of practical theology that described "what is going on" in bereavement care, the current investigation moves into a pragmatic task that proffers "how we might respond." In specific terms, a practical theology of bereavement care will be developed out of a theopaschitic approach and a theology of compassion (Louw 2015a-b). From this basis, a paradigm of comforting presence will be proposed to improve the interplay between caregivers and care-seekers to facilitate a process of re-ritualization. Finally, an informed practical theology of bereavement will be demonstrated through three (3) key moments of re-ritualization within a meta-theoretical narrative framework of care (i.e. before a death, at the time of death, and after a death occurs).

Theopaschitic thinking and a theology of compassion

A practical theology of bereavement care necessary for re-ritualization is fundamentally rooted in the compassion of God (ta splanchna) (Louw 2011; Davies 2001). Within the "chaosmos of life", the theodicy question inevitably arises (Louw 2015a:163).12 Care-seekers often wrestle with how the power of God seems to contradict the goodness of God. The bereaved may ponder questions like: "If God is all-powerful and all-good, why did he let my loved one die? Why would God cause this death? Does he even care about me?" In a practical theology of bereavement, if the theodicy question is left unanswered, care-seekers are often robbed of meaning and hope. Louw explains the impact on caregivers as well: "in the attempt to comfort people, caregivers are challenged by the question "why?" within the reality of painful, existential paradoxes" (2015b:2).

A significant pastoral challenge in bereavement care is to reintroduce the theodicy question through God-images of comfort when one is confronted with death, loss, and grief. Fortunately, theopaschitic theology can play a decisive role in reframing seemingly static God-images that may express God in stoic and apathetic terms. To be sure, theopaschitic theology asks: Is it possible to shift our thinking from common omni-categories of God to more compassionate categories of pathos thinking? God is often imagined in terms of omnipotence (without any weakness), omniscience (without ignorance or uncertainty), omnipresence (without constraints of time or space), and even immutability (without any vulnerability). As such, Christian theological reflection on God images are often more influenced by an imperialistic interpretation of God as pantokrator (i.e. almighty and all-powerful) than by a compassionate interpretation of a vulnerable and suffering God (Louw 2015). To be clear, while a pantokrator image of God certainly depicts common orthodox views, these concepts often do not do justice to the haunted world bereaved human beings experience in the solitude of their grief. The current investigation suggests that theology proper should be further nuanced through theopaschitic thinking to enhance a caregiver's posture for addressing the practical concerns of bereaved persons in the wake of significant grief and loss. In other words, if one really wants to "experience" God in bereavement, one must encounter him first in a warm embrace before one defines him in a cold doctrine (Cox 1969:28).

A re-conceptualizing of God as an intimate co-suffer in loss offers much promise for a theology of bereavement caregiving within the current postmodern ethos of deritualization. Rather than thinking of God only in terms of immutable categories, Old Testament studies assert that the Jewish and Christian God is more verb- than noun-like. This idea is nothing new. Some biblical scholars "translate God's answer to Moses' request for God's name in Exodus 3:14, YHWH, as 'I am who I am becoming' rather than the etymology of YHWH, 'I am who I am.' " (Miller-McLemore 2014:8; Artson 2016).13 The point is, in either case, YHWH is a "verbal form" and indicates the sustainable presence of an on-going intervention and promise of God, rather than a metaphysical entity interpreted in terms of immutable categories.14 Within God's capacity as "a Being for us," God discloses himself as being involved in the suffering of humankind (including the pain of grief in death and loss), and "thus he becomes a suffering God for suffering human beings in a dynamic act of revelation. In these events of God-being-for-us, God's mode of being is still in the process of becoming; it is a kind of infinitive (continuous happenstance)" (Louw 2015b:9). In this way, God may be conceived as more than an all-powerful being who stands distantly removed from one's grief and pain; indeed, God is a co-suffering divine companion.

Compassion-images emerge early in the Old Testament and are linked to the Hebrew meaning of the name of God as expressed in the continuous tense of the verb to be: haja (Louw 2015a) The name of God has thus future, hopeful implications for the quality of life emanating from the vivid presence of the Lord (YHWH): "I am who I am becoming." In this name, his El Shaddai, his all-encompassing presence, will be displayed as a co-suffering source of encouragement and hope. The suggestion of the future tense in the promise to Moses yields processes of hoping for the bereaved, namely that the significance of the name of God will always be revealed in his faithfulness to his promises, and gradually (infinitive tense) through his unfolding actions of comfort and care (the praxis of God), people may discover that even in the complexity and sadness of unpredicted events such as death and loss, God does not necessarily explain what is happening, but he displays his mercy (deseh) as a response to the outcry of bereaved human beings in great anguish and despair. This continuous tense of God's ongoing care provides great support for the dynamic concept of re-ritualization in terms of a commitment to unfolding new and creative forms of ritual support to the bereaved, even outside traditional paradigms.

One can conclude that the name of God refers more to a verb in the continuous tense than a fixed substance in the past tense - from the omniscience of God to what can be described as the "infiniscience" of God (Louw 2015 a): The ongoing modes of divine interventions through and by the indwelling Spirit of God within the functions of the church as expressions of God's presence in the world. In this way, the infiniscience of God indicates that his power is less about a causative threat-power and more about a compassionate comfort-empowerment; infiniscience displays sustainable and on-going faithfulness and grace, even in the face of loss in death. God is the living God within the covenantal infiniscience: the God of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob. The fact is that the hesed of God (mercy and loving-kindness) and the oiktirmos of God (compassion and pity) have implications for both the naming of God in the praxis of bereavement caregiving, as well as for a Christian anthropology. Hesed and oiktirmos define God as a Compassionate Companion and Intimate Partner for spiritual wholeness and eudaimonic well-being in life; these ancient terms define human beings as agents and beacons of hope and wounded healers of life despite the zig zag patterns of suffering the deep pains of loss.

As a practical theological gerund, the "verbing of God" (Louw 2015a) culminates most clearly in the Passion of Jesus (paschö). In the account on Christ's narrative of suffering, paschö demarcates the identity of Christ's mediatorial work and further substantiates the connection with suffering and death: pathêma tou thanatou (Heb. 2:9). Christ's vicarious suffering means for believers not deliverance from earthly suffering, but deliverance for earthly suffering and the creation of courageous resilience. The hope emanating from a theology of the cross (the divine paradox of the forsakenness of the dying Son of God) resides in the fact that due to his vicarious suffering, Christ is able to comfort the bereaved through his compassion; suffering defines Christ as a high priest who sympathizes (sympathêsai) with our weakness in death and loss (Heb.4:15).

Theopaschitic thinking certainly derives a unique identity from ta splanchna, the compassion of God. In terms of pastoral care, a key question is: How can human beings who are suffering in grief be introduced to God's active presence as a Compassionate Companion and Intimate Partner? Instead of emphasizing only the omni-categories of God, ta splanchna summons bereavement caregivers to a lifestyle of hospitable being-with and suffering-with those marginalized by grief in life (Louw 2015a). A significant implication for the current investigation is that caregivers (i.e. pastors and funeral directors) should be characterized chiefly by their compassion and hospitality, aligning "our own 'being' with God's 'being', and thus, performatively, to participate in the ecstatic ground of the Holy Trinity itself" (Davies 2001:252). What needs to be demonstrated however is how re-ritualization provides a means for caregivers to connect deeply with the bereaved from a position of compassion and hospitality. As such, the current investigation will now establish in specific terms how theopaschitic thinking augments a practical theology of bereavement caregiving.

A paradigm of comforting presence

Based upon the parameters of theopaschitic thinking and a theology of compassion described above, bereavement caregivers have a profound basis to respond to the threat of deritualization with a more dynamic and compassionate posture of nurturing care than ever before. Given the current decline of people's perceptions regarding the effectiveness of traditional funeral rituals to meet their needs, an improved posture of professional readiness capable of moving care-seekers toward more effective nurturing care is warranted. Re-ritualization is the intentional act of restoring and reengaging in creative and meaningful ritual forms that give symbolic expression to significant thoughts and feelings. To that end, the current investigation introduces a paradigm of comforting presence that describes the dynamic interplay needed between caregivers and care-seekers.

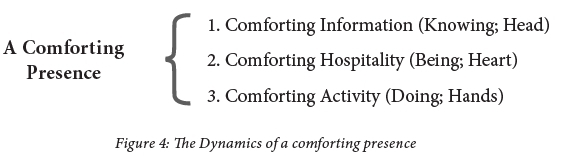

A comforting presence represents a posture of professional readiness rooted in theopaschitic thinking and personified by caregivers welladept at the essential practices utilized in nurturing care (Gibson and Troyer 2017b).15 The paradigm is developed in terms of ongoing modes of comforting information (i.e. knowing), comforting hospitality (i.e. being), and comforting activity (i.e. doing) where God may be encountered and genuine healing may occur. In this way, a paradigm of comforting presence is a multidimensional theopaschitic concept rooted in the infiniscience of God that engages the spheres of head, heart, and hands in bereavement care (see Figure 4 below).

Each of the three (3) essential functions are briefly described below to explain how the internal dynamics of a Comforting presence shape the professional readiness needed for today's nurturing care of the bereaved.

• Knowing functions of care include not only a caregiver's knowledge of funeral products and services, ceremony staging, and mortuary law, but also refer to a caregiver's ability to share comforting information with bereaved people who need to be well-informed about their grief. Professionally-ready caregivers must have an advanced understanding of the contexts of loss so that they are able to anchor the bereaved against the forces of grief. Caregivers must be committed to ongoing interdisciplinary learning from diverse fields such as funeral service as an applied business discipline, bereavement psychology as a social science, and practical theology as a field of theological inquiry. In a paradigm of comforting presence, bereavement care providers stand ready to offer true comforting information to bereaved families and individuals in the wake of acute loss.

• Being functions refer to a caregiver's ability to provide comforting hospitality to the bereaved (Louw 2015 a). Bereavement caregiving is commonly approached in terms of specialized knowledge and activity by professionals, placing emphasis on communicating both right words and right actions to care for the bereaved. While both knowledge and action are helpful pastoral functions for both funeral directors and vocational pastors, what is often missed is a key function caregivers provide by their simple physical presence with the bereaved. Henri Nouwen describes this hospitable there-ness so beautifully: "Hospitality means primarily the creation of free space where the stranger can enter and become a friend ... hospitality is not to change people, but to offer them space where change can take place" (Nouwen 1985:55). Capretto suggested that "one can speak volumes and empathize little; one can empathize profoundly and offer few words" (Capretto 2015:349). Particularly in cases of traumatic loss where caregivers often search for the right words, a ministry of silent presence and hospitality is helpful. Capretto explained: "The effects of silence begin with the fact that in silently relating to a griever in her or his loss, the caregiver makes the decision to work with the inability of empathic language as opposed to trying ambitiously to overcome or surmount it" (Capretto 2015:352). Professionally-ready bereavement care providers possess the alterity to be open to the pain of others, the fortitude to wrestle with the mystery of death, and the skills to listen empathically without feeling the need to resolve existential crises with empty platitudes (e.g. "she's in a better place," or "God doesn't give you more than you can handle").

• Doing functions in a paradigm of comforting presence refer to a caregiver's ability to design and facilitate comforting activity for the bereaved in the wake of acute loss. As bereaved families entrust caregivers with their sacred stories, caregivers are uniquely positioned to facilitate meaningful opportunities that honor personal narratives through shared experiences with family and friends. Re-ritualized events should provide both an accurate reflection of one's life and legacy as well as support for those who have experienced the death of a loved one. Thomas Lynch referred to this doing function as "to get the dead where they need to go and the living where they need to be" (Long & Lynch 2013:xii). Professionally-ready caregivers stand prepared to suggest creative and relevant activities that support bereavement care.16

Three moments of re-ritualization

Given these essential functions of a comforting presence (i.e. knowing, being, and doing), the current investigation suggests that a broad and flexible framework for bereavement care can be developed to better understand real-life scenarios with those seeking professional assistance with loss. In terms of funerary support, a paradigm of comforting presence can be demonstrated practically through a meta-theoretical framework of care that emphasizes the role of funeral directors. In simplest terms, despite the threat of deritualization on processes of grieving, funeral caregivers have a unique opportunity to participate significantly in the lives of families through the realms of education, service, and support. A chief contention of the current investigation is that these three (3) realms are best expressed as moments of re-ritualization in a narrative approach to bereavement care.

While many may think of funeral directors as working primarily with families dealing with acute loss, the current article defines the role of funeral service practitioners more broadly, in terms of the three common activities of creative re-ritualization: 1) professional assistance before a death occurs (Education), 2) professional assistance when a death occurs (Service), and 3) professional assistance months and even years after a death has occurred (Support). A narrative approach to bereavement care builds upon a foundation in practical theology and the infiniscience of God that recognizes the ongoing fundamental need of finding comfort, meaning, and hope amid the existential realities of life. By focusing upon the human dignity of one's life story, these three distinct moments of re-ritualization (Education, Service, Support) can be observed. Each of these moments will be described below from a narrative approach to bereavement care (see Figure 5).

Moment 1: Education (Preparing a bereavement plan):

As a regular function of their daily work, funeral directors are often asked by people of their community for assistance in the advance planning of a funeral before a death occurs. Funeral directors should make the most of these opportunities to help families develop a bereavement plan. Some families may be experiencing anticipatory grief as they expect a death to soon occur in the days, weeks, and months ahead. Other families plan far in advance of an anticipated death. In most cases, however, people who seek the professional assistance of funeral directors to create an advanced plan for their own death, do so to garner peace of mind that their final wishes will be known at the time of need.

Using the dynamics of a comforting presence (knowing, being, doing), funeral directors assist in the planning process by educating individuals on the importance of providing nurturing care for their surviving loved ones.17A practical theology of bereavement care helps funeral directors attend to one's personal narrative in order to plan effective care (and ecclesial support) before a death occurs. In funeral service vernacular, "pre-need planning" is not merely about selecting and paying for a casket in advance or securing insurance to pay for a funeral bill; instead, for individuals who have the time and opportunity to do so, writing their story becomes a means to think through the care their family will need if and when a loss occurs. A significant outcome of re-ritualization through activities of education is that advance planning is no longer thought of in terms of what someone wants for one's self after death, but what kind of care and support one wants his/her family to receive when death occurs.

Moment 2: Service (Sharing through memorialization):

A second moment for re-ritualization occurs when a family experiences a meaningful changed reality through the death of a loved one. Using the dynamics of a comforting presence, funeral directors should pursue understanding a family's specific needs in order to provide meaningful caregiving opportunities that will facilitate the internalization of loss. In lieu of the traditional hierarchal view of funeral services discussed above, a more balanced approach to care would be to help bereaved families conceptualize various components of a meaningful service for their loved ones based upon their actual needs, rather than any prescribed formulas or tired rituals. In this way, a bereaved family is directed to choose among services they perceive to be most helpful to them, including dressing their deceased and/or having a final private viewing, scheduling a public opportunity for family, friends, and community to receive condolences and support, organizing a special event or ceremony to express meaning through story-telling and religious expression, attending to a sacred place for final disposition, and sharing time together in a more relaxed setting, such as a reception or private gathering with food and drink.

The funeral profession refers to this core activity of service as "at-need work" - the short-hand for the types of care provided to the bereaved who are suffering acute grief. At-need bereavement care at this level typically involves the sharing of the deceased's life story among friends and family as a means to initiate meaning-reframing - that is, to consider what life will look like without the deceased present. A significant outcome of re-ritualization through activities of service is not to impose a rigid script for funeral rituals, but to be present to the bereaved in authentic and compassionate ways, and to help create truly meaningful experiences where the bereaved may find comfort, meaning, and hope.

Moment 3: Support (Integrating a continuing bond):

A third moment of re-ritualization occurs when the bereaved seek support many weeks, months, or even years after a loss has occurred. Despite the contemporary science of resilience, people still benefit from effective care that assists in reframing a new meaningful reality after the death of a loved one. This is not surprising because grief remains an irreducible phenomenological mystery - a construct beyond full rationalistic investigation and understanding (Wolfelt 2011). Funeral professionals are especially well-positioned to provide ongoing support to people wrestling with the phenomenology of grief. Though the idea of providing "after-care support" has not always been accepted by funeral directors and the public, much has changed where people now have less ties to faith communities and nearby family members for ongoing support.

In terms of after-care, funeral directors often have opportunities for continued support of families through the first anniversary of loss. Within a narrative approach to bereavement caregiving, support should involve funeral directors assisting families in remembering one's story through creative ritual forms that help integrate the loss into a newly reframed life without the loved one - that is, to continue the bonds (Valentine 2008; Klugman 2006). Some examples of after-care include social support groups for widows and widowers, grief booklets with helpful rituals of remembrance, website memorials and virtual cemeteries, memory gardens with favourite flowers, and holiday and anniversary services, to name just a few ideas. Of course, after-care support is not only about providing support groups or grief materials to bereaved families, it also creates opportunities to build relationships with community partners (e.g. hospice, mental health professionals, and local places of worship).

One exciting new development for after-care support is coming out of the field of nostalgia research (Sedikides & Wildschut 2016a). Though nostalgia has been mostly relegated as a harmful or even undesirable emotion, recent research has found that nostalgia is not a pathology to avoid, but as a fundamentally social emotion, provides significant benefits advantageous to psychological well-being. Defined in terms of normative sentimental longing, nostalgia provides social benefits by boosting feelings of being loved and connected to others, personal benefits by improving moods and increasing one's self-esteem, and existential benefits by reassuring one that life is truly meaningful (Sedikides & Wildschut 2016b). To be sure, nostalgic acts of remembering often drive the human capacity for resilience, the experience of joy, and a sense of purpose in life. For example, as means to help bereaved individuals transition from passive mourning to active remembering, Allison Gilbert (2016) encourages the hosting of a "Memory Bash" - a celebratory party to drink, eat, and celebrate loved ones who have passed. Though there is still much to uncover in the research of nostalgia, funeral directors should utilize the findings of this important research to develop appealing new community programs that encourage people to engage in rituals of nostalgic reverie.

A significant outcome of re-ritualization through after-care support is that funeral directors have significant opportunities as they practice a comforting presence to design and promote creative community initiatives for the bereaved to continue the bonds with their deceased, remember the important stories from people who have shaped their lives profoundly, and honour their own re-framed stories as a means to protect self-continuity and aid in eudaimonic well-being (Sedikides et al. 2016).

5. Conclusion

Practical theology provides much insight into issues relating to the marginalized in life. Indeed, practical theology often focuses pastoral practice on individuals as "living human documents" (Gerkin 1984) or on social contexts as "living human webs" (Miller-McLemore 1996). In the current investigation, however, a practical theology of bereavement care may be more accurately presented as caregiving through "living human instruments" (Stevenson-Moessner 2016), accenting not only human agency, but also human creativity through re-ritualization in pastoral care. Bereaved human beings are often marginalized as they seek comfort and meaning in the wake of acute loss. This marginalization is frustrated by a growing trend of deritualization, where the bereaved minimize or even eliminate important funerary rituals to help cope with loss. Bereavement caregivers today need a more creative process of re-ritualization to provide effective nurturing care. In this way, a practical theology for bereavement caregivers (i.e. funeral directors and vocational pastors) can be characterized as an overture that represents a kind of creative energy of God. In this sense, funeral directors are becoming in fact God's living human instruments (Stevenson-Moessner 2016). The current investigation presented this overture of practical theology as a paradigm of comforting presence rooted in theopaschitic thinking, where caregivers meet care-seekers in a dynamic interplay of education, service, and support - indeed as variations on a theme of eudaimonic well-being. The latter refers to a wholistic approach in pastoral caregiving wherein the theological paradigm of the Passio Dei, and the God-concept of divine compassionate being-with (infiniscience of Jahwe), provide a Christian spiritual framework for the interdisciplinary and professional interplay between pastoral caregiver and funeral director.

Bibliography

American Psychiatric Association 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: 5th edition.

Artson BS 2016. God of becoming and relationship: The dynamic nature of process theology. Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights Publishing. [ Links ]

Atherton J 2015 (21 April). Walking with the poor. Principles and practices of transformational development: A Review. Practical Theology 6(1): 113-114. [ Links ]

Beardsley C 2009. When the glow fades: The chaplain's role in non-religious spiritual rites for the bereaved. Practical Theology 2(2): 231-240. [ Links ]

Boerner K, Wortman CB, & Bonanno G 2005. Resilient or at risk? A four-year study of older adults who initially showed high or low distress following conjugal loss. Journal of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 60(B): 67-73. [ Links ]

Bonanno GA 2004. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist 59(1): 20-28. [ Links ]

Bonanno GA 2009. The other side of sadness: what the new science of bereavement tells us about life after loss. New York, NY: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Bregman L 2010. Religion, death, and dying. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Publishers. [ Links ]

Beck R & Metrick SB 2009. The art of ritual: Creating and performing ceremonies for growth and change. Berkeley, CA: The Apocryphile Press. [ Links ]

Cahalan KA & Mikoski GS (eds) 2014. Opening the field of practical theology: An introduction. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ]

CANA 2011. Annual Cremation Association of North America statistics report. CANA Statistics Group.

CANA 2016. Annual Cremation Association of North America statistics report. CANA Statistics Group.

Cann CK 2014. Virtual Afterlives: Grieving the Dead in the Twenty-First Century. Louisville: University of Kentucky Press. [ Links ]

Capretto P 2015. Empathy and silence in pastoral care for traumatic grief and loss. Journal of Religion and Health (54): 339-357.

Cobb AG 1892. Earth-burial and cremation: The history of earth-burial with its attendant evils, and the advantages offered by cremation. New York, NY: The Knickerbocker Press. [ Links ]

Cox H 1969. The feast of fools: A theological essay of festivity and fantasy. New York, NY: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Davis O 2001. A theology of compassion: Metaphysics of difference and the renewal of tradition. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Doka KJ 2013 (29 July). Grief and the DSM: A brief Q&A. Huff Post. [Online]. Available: http://www.huffingtonpost.com [Accessed: 2017-09-16].

Eassie W 1875. Cremation of the dead. London: Smith, Elder, and Company. [ Links ]

Farley E 1983. Theologia: The fragmentation and unity of theological education. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Fegan CJ 2017 (26 June). Don't ask, don't tell: Silence in Northern Ireland Christian churches regarding issues of sexuality. Practical Theology 10(3): 291-303. [ Links ]

Garces-Foley 2010. Funerals and mourning rituals in America: Historical and cultural overview. In: T Bregman (ed.). Religion, Death, and Dying: Bereavement and Death Rituals. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Publishers. [ Links ]

Gerkin CV 1984. The living human document: Re-visioningpastoral counselling in a hermeneutical mode. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press. [ Links ]

Gibson CL 2005. Religiosity and work in the lives of mortuary college students. Boca Raton, FL: Dissertation.com. [ Links ]

Gibson CL 2016. The deritualization of death: Toward a practical theology of caregiving for the bereaved (Dissertation). Stellenbosch University: Stellenbosch, South Africa. [ Links ]

Gibson CL and Troyer J 2017a (April). "Providing Nurturing Care: A Compelling New Vision." The Director 89(4): 46-48. [ Links ]

Gibson CL and Troyer J 2017b (August). Providing Nurturing Care: A comforting presence. The Director 89(8): 38-44. [ Links ]

Gilbert A 2016. Passed and present: keeping memories of loved ones alive. Berkeley, CA: Seal Press. [ Links ]

Gillespie D & Defort EJ 2017 (September). How consumers shop for funeral services: Inside the numbers of the 2017 NFDA Consumer Awareness and Preferences Survey. The Director 89(9): 36-54. [ Links ]

Hoy WG 2013. Do funerals matter? The purposes and practices of death rituals in global perspective. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

International Cremation Statistics 2011 (Winter). Pharos International, 27-25.

Irion PE 1954. The funeral and the mourners: pastoral care of the bereaved. Nashville, TN: Parthenon Press. [ Links ]

Irion PE 1966. The funeral: Vestige or value? Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press. [ Links ]

Irion PE 1991. Changing patterns of ritual responses to death. journal of Death and Dying (22):159-172.

Kastenbaum R 2004 (Summer). Why funerals? Generations, 5-10.

Kelley MM 2010. Grief: Contemporary theory and practice of ministry. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Klugman CM 2006. Death men talking: Evidence of post-death contact and continuing bonds. Omega 53(3):249-262. [ Links ]

Kübler-Ross E 1969. On death and dying. New York, NY: Scribner. [ Links ]

Laderman G 2003. Rest in peace: a cultural history of death and the funeral home in twentieth-century America. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Lartey EY 2013. Postcolonializing God: An African practical theology. London: SCM Press. [ Links ]

Laqueur TW 2015. The work of the dead: A cultural history of mortal remains. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Lipka M 2016 (24 August). Why America's "nones" left religion behind. Pew Research Centre. [Online]. Available: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/08/24/why-americas-nones-left-religion-behind [Accessed: 2017-9-5].

Long TG and Lynch T 2013. The good funeral: Death, grief, and the community of care. Louisville, KY: John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Louw DJ 1998. A pastoral hermeneutics of care and encounter: A theological design for a basic theory, anthropology, method and therapy. Heerengracht, Cape Town: Lux Verbi. [ Links ]

Louw DJ 2011 (4 November). Ta splanchna: A theopaschitic approach to a hermeneutics of God's praxis. From zombie categories to passion categories in theory formation for a practical theology of the intestines. HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 67(3):13 pages. [ Links ]

Louw DJ 2014. Interculturality and wholeness in African spiritualties and cosmologies. The need for communality (Ubuntu philosophy) and compassionate co-humanity (utugi-hospitality) in the realm of pastoral caregiving. In: Reflective Practice Formation and Supervision in Ministry. (34):23-38.

Louw DJ 2015a. Wholeness in hope care: On nurturing the beauty of the human soul in spiritual healing. London: LIT Verlag. [ Links ]

Louw DJ 2015b. On facing the God-question in a pastoral theology of compassion: From imperialistic omni-categories to theopaschitic pathos-categories. In die Skriflig 49(1), Art. #1996, 15 pages. Accessed from: http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ids.v49i1.1996, 2017-9-16. [ Links ]

Miller-McLemore BJ 1996. The living human web: Pastoral theology at the turn of the century. In Stevenson-Moessner (Ed.) Through the eyes of women: Insights for pastoral care. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress: 9-26. [ Links ]

Miller-McLemore BJ (ed) 2014. The Wiley-Blackwell companion to practical theology. Sussex, UK: Blackwell Publishing Limited. [ Links ]

NFDA 2014 (September). The 2014 NFDA cremation report: Research, statistics and projections. National Funeral Directors Association. Brookfield, WI.

NFDA 2017 (July). The 2017 NFDA cremation and burial report: Research, statistics and projections. National Funeral Directors Association. Brookfield, WI.

Nouwen H 1985. Reaching out: the three movements of the spiritual life. New York: NY: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Osmer R 2008. Practical Theology: An Introduction. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Pierce PE 2007. A practical theology of mental health: a critical conversation between theology, psychology, pastoral care and the voice of the witness. Doctoral thesis, Australian Catholic University. [Online]. Available: http://researchbank.acu.edu.au/theses/201 [Accessed: 2017-9-16]. [ Links ]

Pettitt P 2011. The paleolithic origins of human burial. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Pew Research Center 2012 (9 October). "Nones" on the rise: One-in-five adults have no religious affiliation. The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life.

Pew Research Centre 2015 (12 May). America's Changing Religious Landscape: Christians decline sharply as share of population; Unaffiliated and other faiths continue to grow.

Radford CL 2017 (22 March). Meaning in the margins: Postcolonial feminist methodologies in practical theology. Practical Theology 10(2):118-132. [ Links ]

Reddie AG 2009. Re-imagining Black Biblical Hermeneutics in Britain: A Participative Approach. Journal of Adult Theological Education 5(2):158-177. [ Links ]

Ryan RM and Deci EL 2001. On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annual Review of Psychology (52):141-166.

Sedikides C, Wildschut T, Cheung, WY, Routledge C, Hepper EG, Arndt J, Vingerhoets, A 2016. Nostalgia fosters self-continuity: Uncovering the mechanism (social connectedness) and consequence (eudaimonic well-being). Emotion 16(4):524-539. [ Links ]

Sedikides C and Wildschut T 2016a. Nostalgia: A bittersweet emotion that confers psychological health benefits. In: Wood AM and Johnson J (Eds.). The Wiley handbook of positive clinical psychology. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: 125-136. [ Links ]

Sedikides C and Wildschut T 2016b (May). Past forward: Nostalgia as a motivational force. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 20(5):319-321. [ Links ]

Starks J 2014 (October). How to properly manage remains before, during & after cremation. ICCFA Magazine, 24-29.

Stevenson-Moessner J 2016. Overture to practical theology: The music of religious inquiry. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers. [ Links ]

Taylor JS 2011a (April 2). Who killed the funeral? The really inconvenient truth. Presentation to National Funeral Directors Association Professional Women's Conference.

Taylor JS 2011b. Unfinished business: A study of leadership and adaptive challenges in the professionalization of funeral directors. Union Institute & University; Cincinnati, OH: UMI Dissertation Services. [ Links ]

Thesnaar CH 2012. A pastoral hermeneutical approach to reconciliation and healing: A South African perspective. In M Leiner and S Flamig (eds) Latin America between conflict and reconciliation. Bristol, CT: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: 215-230. [ Links ]

Valentine C 2008. Bereavement narratives: Continuing bonds in the twenty-first century. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Van Gennep A 1960. The rites of passage. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago. [ Links ]

Wolfelt AD 2005 (March-April). Why is the funeral ritual so important? American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy: Family Therapy Magazine, 12-17.

Wolfelt AD 2006. Companioning the bereaved: A soulful guide for caregivers. Fort Collins, CO: Companion Press. [ Links ]

Wolfelt AD 2007. The wilderness of grief: Finding your way. Fort Collins, CO: Companion Press. [ Links ]

1 Wolfelt suggests that in a state of bereavement, suffering from loss affects physical, emotional, cognitive, social, and even spiritual domains of human functioning (2006).

2 Eudaimonic well-being is a helpful term that should be distinguish from a hedonic approach that frames happiness in terms of pleasure attainment and pain avoidance. A eudaimonic approach focuses on meaning and self-realization, and frames well-being in terms of full human functioning (i.e. flourishing).

3 In funeral service vernacular, a memorial service is regarded as a ceremony without a deceased body present. Some families who opt for cremation also choose to ritualize with a memorial service or "celebration of life" ceremony (with or without clergy) in order to honour their deceased loved ones.

4 A columbarium is a term that describes an above ground physical structure with recessed chambers, called niches, designed especially to house cremated remains. In addition to simply retaining cremated remains in urns or other keepsakes at one's home, some families choose scattering options by sea or by air (e.g. using boats, balloons, aircraft, and even pyrotechnic displays). Cremated remains are also being made into jewellery keepsakes, trees, or structures that create marine water reefs.

5 As another option for cremation, alkaline hydrolysis is an ongoing debatable issue regarding a water and chemical based process in lieu of the traditional fire-based method. Some argue that alkaline hydrolysis (also known as Resomation* or biocremation) uses less energy and creates less pollutants than traditional fire-based cremation. Currently, alkaline hydrolysis has not been approved by all U.S. states.

6 The rapid growth in preferences toward direct "no-frills" cremations without funeral or burial services may surprise many pastors and funeral directors, though this trend appears to be consistent with what is happening in the United Kingdom and Canada (Cann 2014:133). For example, the cremation rate in Canada was 62.1% in 2010 and 68.8% in 2015; similarly, the cremation rate in the United Kingdom was already at 73% by 2010 (CANA 2016; CANA 2011:13, 20). Though cremation was first discussed in America in the late 19th century (Eassie 1875; Cobb 1892), as late as 1965, the US Cremation Rate was still less than 4%. Currently, some countries have much higher cremation rates than the United States, such as Japan (99.9%), Hong Kong (89.9%), and Sweden (78.6%) (NFDA 2014). Other countries still have very low cremation rates, such as South Africa (3-6%) (International Cremation Statistics 2011).

7 A recent study that looked at resiliency in older adults found that most elders who showed high distress initially, remained in this pattern even after four years (Boemer, Wortman, and Bonanno 2005).

8 From the perspective of practical theology, human resilience may represent a mechanism that demonstrates the very grace of God to care for all people, in any context, who are faced with the marginalization of loss and grief.

9 Even in cases of traumatic loss, resilience may be more common than often believed (Bonanno 2004).

10 One significant finding in the review was how the most recent Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (2013) (i.e. the essential guide for diagnosis and treatment of mental illnesses) seemed somewhat inconsistent with resilience theory. The current DSM5 reversed a decision made in prior versions and thereby removed the bereavement exclusion from both depression and adjustment disorders. Doka (2013) explained: "What this means in simplest terms is that a person who is grieving a loss potentially may be diagnosed with depression or an adjustment disorder." A very practical concern was that bereaved individuals may have a greater likelihood of being prescribed antidepressants to resolve grief. This medicalization or pathologizing of grief seemed contrary to current resilient theory that advances normal grief processing over the course of six months to a year.

11 This was evident in Bonanno's personal use and exploration in the value of Chinese bereavement rituals that were used to honor his father's life (Bonanno 2009:169-193).

12 The "chaosmos of life" is a helpful phrase to describe how ordinary life in the world is not simply constructed by order and design, but partly by disorder and chaos as well.

13 Though the current investigation is not an argument for process theology, Louw explains: "Process theology is a type of theology that was developed from Alfred North Whitehead's (1861-1947) process philosophy, and most notably developed by Charles Hartshorne (1897-2000) and John B. Cobb (b. 1925). For both Whitehead and Hartshorne, it is an essential attribute of God to affect and be affected by temporal processes, contrary to the forms of theism that hold God to be in all respects nontemporal (eternal), unchanging (immutable), and unaffected by the world (impassable). Process theology does not deny that God is in some respects eternal (will never die), immutable (in the sense that God is unchangingly good), and impassable (in the sense that God's eternal aspect is unaffected by actuality), but it contradicts the classical view by insisting that God is in some respects temporal, mutable, and passible" (2015b).

14 In English, "gerunds are words that end with -ing and look like verbs but function as nouns. That is, they are nouns (words that name persons, places, ideas, etc.) that contain action; they are verbs used as nouns" (Miller-McLemore 2014:8).

15 Just as theopaschitic thinking challenges powerful omni-categories of God (e.g. omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent) to include a powerful pathos category of God's compassion as an active and ongoing comforting presence (i.e. God is being-there, being-with, and being-for human beings), similarly, a practical theology of bereavement care challenges common funeral director images (e.g. embalming, livery, merchandising, insurance, event planning, disposition) to embrace a compassionate posture of a comforting presence (i.e. funeral directors being-there, being-with, and being-for bereaved care-seekers).

16 Consistent with the aims of re-ritualization, even a direct disposition such an immediate burial or a simple cremation without ceremonies is a significant, if not essential, funeral rite. Throughout antiquity, families who experienced a loss have reached out for assistance with their dead - to dispose of a deceased human body with respect and great care (Laqueur 2015). Bereavement caregivers are implored therefore never to minimize the significance of the activity connected to disposing humanely of a deceased human being. Funeral practitioners should no longer refer to some families as needing "just a cremation." Instead, they must recognize the significant opportunity they have been given to care for a given family and the dignity of a deceased human body.

17 Educational components of a Comforting Presence are not limited to funeral service establishments of course, but also included local churches who take seriously the ministry of bereavement care.