Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

On-line version ISSN 2413-9467

Print version ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.4 n.1 Stellenbosch 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2018.v4n1.a11

ARTICLES

Christianising Edgar Chagwa Lungu: The Christian nation, social media presidential photography and 2016 election campaign

Kaunda Chammah J

University of South Africa. pastorchammah@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This article investigates how the declaration of Zambia as a Christian nation (hereafter the Declaration), presidential photography and social media intersected during Edgar Lungu's political campaign in the general election of 2016. It is framed within a missio-political theory to analyse qualitative material collected from January 2016 to February 2017 in Zambia. The missio-ethnography approach as an empirical missiological research which sought to analyse how the Declaration discourse has developed into a political ideology used to legitimized Lungu's political power and moral authority among some Pentecostal-Charismatic religious sector.

Key words: Declaration discourse; Presidential candidate photographic self-representation; missio-ethnography; missio-political; Christianising Lungu Edgar Chagwa; social media; Zambia

1. Introduction

Political representation and discourses in social media are redefining political campaigns in the world increasingly constructed around visual representations. Scholars are arguing that visual communication has taken primacy over words and texts. In many parts of the world, scholars are demonstrating that presidential elections are being won and lost on the account of how adequately the presidential candidate was authentically represented through social media platforms. The public media spaces such as Facebook, Google images, Instagram, and Twitter, play a crucial role in presidential candidates' self-representations during campaigns.

Presidential photography are being deployed on social media spaces to either legitimate or delegitimize political candidates. In religiously influenced contexts such as Zambia, social media presidential candidates' photographs seek to represent the candidate within the ambience of particular religious-cultural "significance in which symbols, objects, sentiments and practices are experienced as expressions of a normative, absolute reality." The article investigates the interplay among the Declaration of Zambia as a Christian nation (hereafter the Declaration), Edgar Chagwa Lungu's social media presidential photography in various places of worship and political campaign in the general election of 2016. It argues that Lungu's social media presidential photography functioned as subliminal texts underlying the Declaration as a religious-political state apparatus for political legitimization.

2. On missio-political theory and missio-ethnographic approach

It is important to highlight that social media presidential photos are represented in relation to the popular religious discourses within the nation. In the case of Zambia, the Christian nation (hereafter, the Declaration) discourse was used as an ideological state tool through which social media presidential candidate's photographs were reproduced, affirmed, embodied and epitomised as actualising the Declaration. In order to place the question of politics and religious abuse at the centre of concern, missio-political critique takes a disruptive approach to the commonly held views of religion as an instrument that can neutrally shape socio-political attitudes and reorient the state towards the common good. It responds to the neo-colonial religious-political trappings to which some African religious imaginations succumb easily. The neo-colonial politics have continued to reframe religious beliefs and practices into ideological state apparatus to manipulate and control religious citizens to think and approach politics in ways that are beneficial to the interests of those in power. It exposes selective construct of reality through uncritical religious claims by representing political leaders in media as a devout Christians and thereby manipulate the consciousness of the masses. Missio-political thinking argues that social media presidential photography is anything but neutral and does not mirror reality. Too often they mask hidden ideologies. The social media presidential photos conceal political messages which carries far more meaning than the masses often realize. Missio-political critique the dominant religious-political ideology based the logic of subjugation, manipulation, and exploitation through abuse of religious systems to brainwash the minds of the masses and mislead them into believing that religion and religious politicians are the answer to Africa's challenges. Therefore, missio-political is decolonial theoretical tool for unmasking, and disrupting hidden agenda and deep message behind political manifesto include social media presidential photography.

Based on Stuart Hall argued that "representation is a very different notion from that of reflection". It implies the active work of selecting and presenting, of structuring and shaping; not merely the transmitting of an already-existing meaning, but the more active labour of making things mean," a missio-ethnographic approach was utilised to gather data in order to critique Lungu's social media presidential photography as clandestine appealing the Declaration to legitimize his candidacy among some religious voters who blindly support anyone who declare themselves as a Christian president. Data was collected between January 2016 and February 2017 in Zambia. The missio-ethnography is an empirical mission-political research that seeks to analyse the church's capacity to take participate in God's mission of justice against human exploitation and oppression. The church is perceived as accompanying God in missional struggle against death-dealing forces through redefining and reconstructing political arrangements for the common good.

It seeks to interrogate how the church understands its missional responsibility in its accompaniment of God in national politics. The engagement with Pentecostal-Charismatics in this article is a deliberate one as they are known by some as the architect and custodian of the Declaration and presidential candidates appears to be aware. For instance, Chiluba's side-lined other mainline churches and religious traditions in favour of Pentecostal-Charismatics and Lungu appears to have a preferential option for them in his political approach. In what follows I begin analysing how the Declaration, social media presidential photography in various ecclesiastical space intersected with Lungu's political campaign in the general election of 2016.

3. The social media presidential photographs as religious-political scripts

The social media photography has become a powerful political tool for representation of presidential candidates during campaigns. Scholars have argued that social media photographic representation is the reproduction and manipulation of socially constructed meaning through visual image portrayal or symbolisms. It is grounded in the views that every day cultural practices, choices, and decisions of people are inseparable from the practices of representations. Too often, the social media representations of presidential candidates seeks to mediate the candidate across to voters as authentic within the socially constructed and culturally acceptable perspective of authenticity. Social media presidential photographic representations are deeply entrenched with "ideological meanings, serving to legitimate the status quo and the interest" of those seeking political power.

Thus, social medial presidential photography is utilised as strategic tool to legitimise presidential candidate's political authority as embedded within a particular social consciousness. Roland Barthes in Mythologies, argues that through social media photographs, presidential "candidate establishes a personal link between him and the voters; the candidate does not only offer a programme for judgment, he suggests a physical climate, a set of daily choices expressed in a morphology, a way of dressing, a posture." Barthes further argues;

"Electoral photography is therefore above all the acknowledgment of something deep and irrational co-extensive with politics. What is transmitted through the photograph of the candidate are not his plans, but his deep motives, all his family, mental, even erotic circumstances, all this style of life of which he is at once the product, the example and the bait. It is obvious that what most of our candidates offer us through their likeness is a type of social setting, the spectacular comfort of family, legal and religious norms, the suggestion of innately owning such items of bourgeois property as Sunday Mass, xenophobia, steak and chips, cuckold jokes, in short, what we call an ideology. Needless to say the use of electoral photography presupposes a kind of complicity: a photograph is a mirror, what we are asked to read is the familiar, the known; it offers to the voter his own likeness, but clarified, exalted, superbly elevated into a type. This glorification is in fact the very definition of the photogenic: the voter is at once expressed and 'heroized', he is invited to elect himself, to weigh the mandate which he is about to give with a veritable physical transference: he is delegating his 'race'."

I have cited him at length since most of the issues I am discussing are threaded through this statement. Indeed, Lungu himself argued during campaign "I want Zambians to begin seeing the president as one of them. The only difference is 'one of them' is privileged to be at the helm ..." Affirming John Dunn's argument that what is politically possible depends in part on how well and accurately the political candidate is able to reproduce social imaginations of the majority citizens. Scholars have highlighted how social media is used as a powerful tool for self-representation among African Pentecostal-Charismatic religious leaders. They know the opportunities that the internet and social media offer for evangelisation, dissemination of their message and self-representation of ministry. Through uncritically exposing their members to internet and social media, most Pentecostal-Charismatics are increasingly becoming highly susceptible to social media religious deception.

Thus, presidential candidates in such highly social media use context, situating themselves within socially acceptable rituals in order to insert and justify their own political authority and agenda using conservative religious ideas. Scholars have observed that political candidates appropriate legitimacy from socially acceptable rituals which are strategically nurtured and covertly redirected to personal political interests. For instance, Anthony Mukwita, a senior diplomat and deputy ambassador for Zambia to Sweden, while over supporting, mistakenly writes: Lungu's ascendancy to presidency demonstrated that if you have a great appeal to the masses and you know them well, you could win their hearts and votes with little or no money. As demonstrated below, strategic politicians know how to incorporate socially acceptable principles of legitimation to generate and legitimise their political power by appealing to strongest conservative worldview of societies and integrate its familiar beliefs and practices to popularise their hidden agenda. Various scholars have indicated that effective application of acceptable religious beliefs, such as the Declaration in Zambia, has potential to increase the status and legitimize political authority, including the leader's control of critical resources and dominate the citizens. Lisa Lucero noted that political association with religious-socially acceptable religious based values could result in sacralisation and uncritical acceptance of political powers because subjects believe that they have been appointed by the Supernatural Being.

Thus, in a Zambian Pentecostal-Charismatic context of social media era presidential candidate photographic self-representation often seek to portray the candidate as epitomizes collective experiences, reliable and authentic representation of the Declaration, which enshrines normative claims over the meanings and moral ideals of the majority of Zambian people. In the 2016 presidential campaigns, social media presidential photography became one of the primary structures for constructing and representing Lungu as ideal presidential candidate, epitomizing the Declaration. The authenticity of Lungu's presidential candidate is to be found at the intersection of social media photographic mediation processes, between the constructed representations of Lungu, and social media consumers, some who were forced into devotion. As Barthes argues social media photography are "an ellipse of language and a condensation of an 'ineffable' social whole, it constitutes an anti-intellectual weapon."

Before, analysing social media presidential photographic self-representation, it is important appreciate why political candidates in Zambia openly side with Christian faith by demonstrating how the Declaration has become a conservative religious instrument in through which public discussions are oriented among the majority of Zambia people.

"That is who we are": The Declaration as a religio-political Ideology

We made the Declaration, in turn the Declaration made us. We can't just shake it off. It is part of us, part of our culture. Even non-believes believe in the Declaration. We cannot just wake up and say 'we're no more a Christian nation' because that is who we are.

This was the response that came from Richard Kasonde. What does he means by the phrase "in turn the Declaration made us ... that is who we are"? It appears that Kasonde believes that the very idea of the Declaration is embodied, or represented in some shorthand form, the idea of "Zambianness" - the national character and culture. It is what Zambians are, what they share in common, and what makes them distinctive. It is the socio-political context of Zambian uniqueness. The preponderance of Zambian Pentecostal-Charismatic and even some scholars hold to this perspective. For instance Rev Charles Kachikoti, former ChiefPolicy Analyst for Press and Public Relations at State House, argues that the Declaration is a "view of the future" and "national character". The Northmead Assembly of God argues that it "is a vision statement and values statement all rolled into one." Rev Elias Munshya, a Pentecostal Theologian and Lawyer, asserts that the "Declaration is a powerful statement of intent and faith which has become the life-force of the nation." Rev Derek Mutungu, a former lecturer at Kaniki Bible College (now Kaniki Bible University College, known as Kaniki) stresses "Zambia is one of two tiny African nations with a mandate to catalyse an alliance of nations under Christ." Mutungu further argues that "Zambia has no choice. We have a mandate from heaven as a nation to play catalyst and prototype in bringing forth Africa's new day. Unless Zambia rises to her calling before God, Africa cannot see her ascendency."

Rev Dr. Nevers Mumba, the first Zambian televangelist and former Vice President of the nation, narrated this powerfully when he addressed clergy at the Ndola Ministers Christian Fellowship. He revealed:

I answered a phone one night. For some time no one spoke. No one introduced themselves. But I could hear the sounds. I could tell people were praying. It was a large prayer gathering. After a little while, my friend Dr. Duncan William of Ghana spoke up. He greeted me ... 'Can you hear what is going on? It's our church. We're praying!' Dr Williams said. 'The Lord has tasked us to pray for Zambia. We pray every day from midnight to 05h00. The church in Zambia is sleeping. You people don't know what you carry. You have not understood the call of God on you. He has raised you to drive the rising of the new Africa. Africa will not go anywhere if you don't come into God's purpose and plan for you. This is why he has aroused as to pray - to push you into your calling.'

While on the surface these arguments appear to refer to the concept of the Declaration as a faith category or a way of life, in essence, it has become a national ideology being used to define and distinguish Zambia from other African nations in significant ways. For instance, the Northmead Assembly of God argues "that God's purpose for Zambia is that of being a tithe to the African continent."The emphasis on Zambia as "Africa's tithe" is covert discourse to promote national holiness or the set apartness of the nation to God out of all African nations. The nation is unlike any other African nation. It "is a modern state which acknowledges the supremacy of God Almighty" Liya Mutale stresses "we are God's nation, a Christian nation, the only nation in the world that has openly declared itself one." It is argued "Zambia as Africa's tithe has to give back to God a part of what she has been blessed with - [peace]". There appears to be a Pentecostal-Charismatic struggle with the general identity and representations of African nations in global society. Most of these Pentecostal-Charismatics are not necessarily ashamed of Africa and their Africanness but seek to ideologically redesign their national representation in defiance of a grand narrative, which has produced an essentialist representation of Africa as homogeneous continent characterized by disease, strife, and backward political, economic, and social conditions. They are basically saying Africa is not homogeneous and each national state has the right to represent itself in ways perceived appropriate by its citizens or some citizens However, Pentecostal-Charismatic national representation is entrenched with a weakness as they seek to distance the nation from wider African problems by telling the world, "see we are better than other African nations, we are Christians." The discourse of Zambia as Africa's tithe makes Pentecostal-Charismatic juxtapose the dichotomy of afro-optimism/afro-pessimism in which Pentecostal-Charismatic is perceived as exceptional nation with authentic spirituality to liberate other African nations from misfortunes, existential struggles and failure to embrace that spirituality is tantamount perpetual suffering. Interestingly, in this discourse, Zambia is portrayed as a solution to the whole continent. How? Only Pentecostal-Charismatics can answer that question?

The Declaration is indeed an ideology. As Ashis Nandy argues, it is a "... subnational, national or cross-national identifier of populations contesting for or protecting non-religious, usually political or socio-economic interests." The Declaration as ideology is usually linked with political and economic texts rather than the ways of life for the community of faith. In actual fact, The Declaration as ideology tendencies to obscure religious diversity even within Christian traditions and represses dissent groups within the marginalised who perceive the politics organised around The Declaration as disproportionally profiting Pentecostal-Charismatic elites and political bourgeoisie at the expense of the masses.

However, the Declaration as Kasonde argues is deeply rooted in the ordinary people's understanding of Zambia as a nation. For instance, the Under 20 National Soccer team is called Bola Na Lesa [soccer with God]. There have been some traditional leaders who have renounced their traditional customs and declare their respective kingdoms as Christian kingdoms. Many of them profess being Christians and strongly support the Declaration as socio-cultural foundation of the nation. Key proponents of the Declaration are Chief Chipepo of the Tonga people of Gweembe district in Southern Province and Chief is Ngabwe of the Lamba, Lenje and Lima speaking people of the Central Province. This seems to suggest that the Declaration has contributed to the spread of Christianity among traditional leaders in contemporary Zambia. It has functioned as a religious apparatus for resisting secularisation, homosexuality, and abortion, especially within Pentecostal-Charismatic circles. Some respondents also feel the Declaration has helped the massed respond to pressures, and uncertainties wrought by modernity, especially in a multi-poverty context - leadership, governance, economic, democratic and so on. In this confusing world of global misrepresentations and local threats, the Declaration has functioned as protective social shield against such insecurities. It also appears to offer some form of hope (maybe false hope?) to the people on the margins.

The Declaration is at the heart of formation of collective Zambian consciousness among the majority of Pentecostal-Charismatics. Scholars confirm that Zambia's political psychic is deeply entrenched with the Declaration within Pentecostal-Charismatic moral sensibilities and theo-political imaginations which greatly influence public discourses and defines national identity. Pastor Haggai Haaciite Mweene of Northmead Assembly of God believes that:

In Zambia today, if you are to go and ask people if they believe in Jesus. You will be very shock, it will probably be 100% or 99 or 95% they will tell you they believe in Jesus and that Jesus is their Lord. It is not as if they are living that, but even in their drunkard state, they will still tell you praises to God. Because that's a culture, Christianity has become some sort of a culture for Zambians.

Mweene's argument is interesting because he is actually saying that the Declaration has not necessarily transformed Zambian cultures rather has been adopted as one core national cultural value. This means that the Declaration has made Christianity like other national values such as 'One Zambia, One Nation', to become a nation religious value without necessarily changing socio-political attitudes. For instance, the Declaration has neither resulted in a corruption free society nor reduced corruption and abuse of public offices. However, even Muslims and other religious traditions affirm that Zambia is a Christian nation. Mweene explains, "Even Muslims accept and declare Zambia as a Christian Nation". Frazer Katanga of Northmead Assembly of God elaborates:

In Zambia Christian nation is by practice a national value. So now when you get into those, then you are now getting into the place I said many things because values are dynamic. Values continue to be impacted by activities practices and beliefs. So the values you have today, maybe impacted by things that come tomorrow. So with that, you have things, when you are given, circumstances for tomorrow, things changed like we have changed in our country, from one party group to multi parties, many things have changed. So some values that we had in our parties stayed still true today, certain values yes and certain values no. And so when you talk about Christian nation, you talk of the value, because of dynamism of life, when you talk of beliefs many things because in beliefs what you believe today will be impacted by tomorrow stuff that come on, so how does your beliefs that you have today survive tomorrow's factors and things that arise, it is also how you define it, how you think it affects your life, so it is the beliefs, the cultural practices, it is the values that you hold which should remain true and reflect on how you will respond to the things that comes to you tomorrow when you begin others values, when you begin to receive for instance, teaching of other culture, when it comes into your cultures, are you going to abandon your culture, or not. So in that sense Christian nation has many things to be handled, that is why today you get people to say, 'oh we are not really a Christian nation, if we are what about all these vices, the alcoholism, the corruption, why all these things, you are Christian?' Remember not all are Christians but have accepted Christian nation as their worldview, value . So are we Christian nation? Yes we are, yes we are.

I have cited this passage at some length because it demonstrates awareness of the ambivalence of cultural transformation that the Declaration has promoted. Nevers Mumba stresses:

It doesn't matter where you go in Zambia today, mention the name of God, you are at home. It was not like this before, so you guys may not know that, Zambia was not as Christian as it is. Almost everyone claims Christianity.

Perhaps, even more important, the Declaration has made tremendous influence on people's political imaginations more than moral and social change. For instance, Mumba highlights;

Zambia was not declared a Christian nation ... faith in God, Christianity and being born again was not a precursor for somebody to run for presidency. But today, even non-believers, even a drunk if he wants to become president, he has to somehow confess that 'me I am a child of God, I am born again' because he knows that if he doesn't say that, he is not going to win the election.

Mumba confirms Bishop Joseph Imakando's observation that: "It has become fashionable to be 'born again'. If you want to become president of Zambia, you must be 'born again'. I hear one president of some opposition political party has become 'born again'." Dr Danny Pule, the former minister in Chiluba's government and president for Christian Democratic, agreed:

All the major political leaders would say we want, because they know they need the support of Christians, we want The Declaration of Christian nation to remain in the constitution, the MMD did the same, the PF did the same although Michael Sata was from the catholic background, the Catholics have publicly opposed that, all he could come and say was that we will rule on the basis of the ten commandments and when it came for the support for declaration to be in the constitution, he had to support it.

The presidential candidates are under pressure to demonstrate authenticity of their affirmation of the Declaration through their self-representation. This pressure emerges from both religious and traditional leadership sectors. For example, the traditional Chief Chipepo called on Zambians during the 2016 presidential elections to "choose Godly people." He argued that "this country is a Christian nation, it is not a satanic nation ... we don't want somebody who killed people to go to Parliament because they are just going to take the spirit of death into Parliament." While the general society perceives affirmation of the Declaration as precursor to presidential run, the politicians have in turn utilised it as a powerful state apparatus for both legitimizing political authority and political control.

4. Mediating Lungu - "the Man of God"

Lungu, who is the 6th Republican President of Zambia since January 2015, started his political career with United Party for National Development (UPND) under the leadership of Anderson Mazoka. He later moved to the Patriotic Front (PF) led by national party founder Michael Chilufya Sata. Lungu served under Sata as Deputy Minister in the Vice President's office, Minister of Home Affairs and later as Minister of Defence and Justice. Lungu would succeed Sata after death in the office on 28 October 2014 to complete the remaining term until elections in August 2016. Sata did not groom a successor and after his death political faction and rivalry broke out over who should lead the party into presidential elections of January 2015. Lungu was finally adopted as the candidate of PF. The political satire singer known as Pilato (Chama Fimba) has released controversial songs which critiques Lungu as irresponsible drunk. He argues that Lungu does not want to take responsibility over national challenges, rather blames God. When Pilato sung satirical piece "Alungu anabwela" [Lungu is back] was sent to jail for a night, but later set free due to lack of evidence. All these political satirical songs moralizes Lungu as a drunk. Some Pentecostal-Charismatics such as Mumba believes that Lungu "nicakolwa" [is a drunk]. This had potential to discredit him in a Pentecostal-Charismatised political context.

The Zambian religious-political discourse hangs around morality. Political discourse is geared around the exposure of transgression for the path towards national developed enshrined in moral leadership. It appears Lungu's campaign team was aware of Lungu's questionable social moral standing and they sought to reposition him in ways that would be socially acceptable in order to win the 2016 presidential election. This is how Christianity has a dominant ideology which has transformed; made radical imprints on human psyche, character and consciousness of social institutions. Mukwita argues that Lungu won elections by merely playing a clever role as a political novice who appeared to know little about politics.

In addition to personal moral issues Lungu's few months in the office immediately after taking over from Sata, were also rattled with overwhelming economic challenges. The copper prices on which the nation's 70 percent of export earnings is derived declined and the currency plunged down to over 45 percent against United States Dollar. The nation was experiencing falling water levels at hydropower plants which triggered severe load shedding. Alarmed, Lungu resolved to seek God's intervention in the economic crisis. He declared 18th October 2015, a public holiday for national day of prayer and fasting which included prayers for national repentance, forgiveness and reconciliation. He also gazetted 18th October as a public holiday for Annual National Day of Prayer for prayer and thanksgiving in 2016. On same day, he re-affirmed President Chiluba's Declaration and claimed "Zambia set free from the dark forces of evil." He also embarked on constructing the National House of Prayer Tabernacle and appointing Bishop Dr Joshua Banda of Northmead Assembly of God Church as the Chairperson of the Advisory Board heading the construction. The argument is that these instruments are intended to strengthen the Declaration. Lungu knows how the Declaration over the last two decades has played an instrumental role in reinforcing a system of thought in which religion and politics intertwine and interpenetrate each other. The reaffirmation of the Declaration even in a symbolic way was essential for some Pentecostal-Charismatics to acceptance his presidential candidacy.

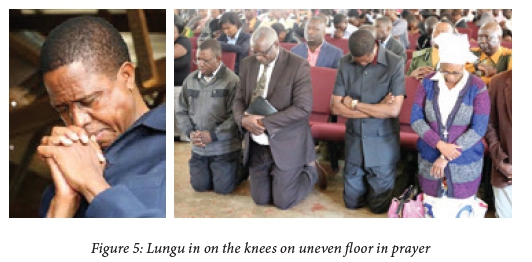

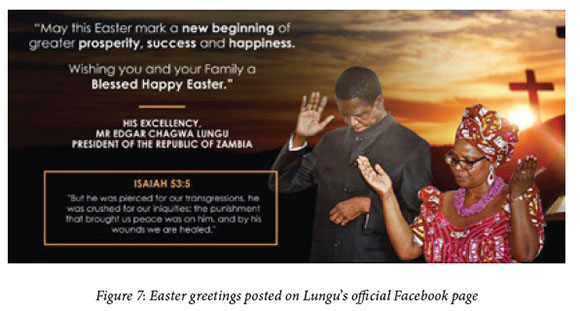

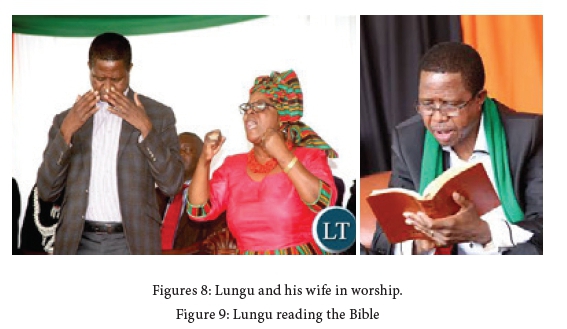

Thus during the 2016 presidential campaign Lungu negotiated his public negative image by being portrayed in the social media photography as a devout Christian. The presidential photos of Lungu participating in church services, which were constantly uploaded on social media such as Facebook and Google Images, Instagram etc., played an important role in Christianization of Lungu in the consciousness of some Zambian Pentecostal-Charismatics people.

During 2016 campaign, Lungu constantly posted on his Facebook every church service he attended. For instance, he posted the following message below;

Today we have attended a Church Service at St. Regina Catholic Parish in Chawama. Today has been designated as Children's Sunday and the young lady that preached led a message and theme of choosing good over evil. She urged citizens to help choose good leaders over evil one. "Let us choose between God fearing leaders, a God fearing President over one that practices dark religion!" she preached. "Ask yourselves congregation are we for Light or Darkness? Even you Mr. President?" She asked me. "Are you for Light or Darkness", she asked strongly? I did not waste time to declare where I stand. I proudly applauded the young preacher in the affirmative that I was for Light and not Darkness, and that I submitted to the Lordship of Jesus Christ.

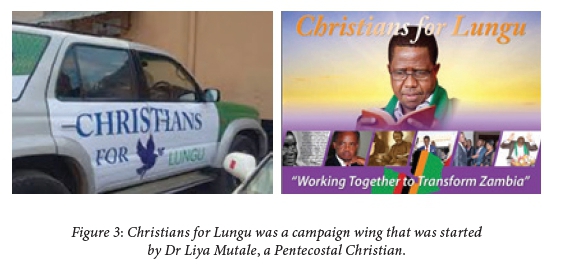

In 2016 campaign the two main presidential candidates - Lungu and the opposition leader, Hakainde Hichilema of the United Party for National Development (UPND) were increasingly categorised in terms of the struggle between good and evil respectively. Hichilema was classified as a Satanist. This already made him an agent of darkness that Pentecostal-Charismatics have to fight against to secure Lungu's winning who was seen as an angel of light. Some Pentecostal-Charismatics formed even a Christian campaign wing called Christians for Lungu (vote for Edgar Lungu). The chairperson for the movement, Dr Liya Mutale argued that Lungu is a "God ordained leader" for Zambia. She emphatically argued that 11 August 2016 presidential election was,

... A spiritual election, a battle for the soul of Zambia. So we have to ensure that Zambian Christian heritage is sustained, it's secured. And to keep it secure, we keep the man that God has called for the season. And we believe that Edgar Chagwa Lungu is that man, so as far as we are concerned he is winning the election anyway.

What was at stake here was to navigate the negative past by controlling how Lungu was portrayed in social media. As Katrien Pype argues, "The particular politics of visualization reveals the state's ocular intrusion." The following presidential photos depict Lungu in various ecclesiastical places during 2016 presidential campaign.

One interest aspact is that most of social media pictures of Present Lungu in various ecclesiastical spaces were taken in the mainline churches (especailly, UCZ and the Roman Catholic Church). This shows that while Pentecostal-Charismatics overtly affirm the Declaration, it is from either the ambiguousts (UCZ) or the rejectionists (Roman Catholic) of the official Declaration from whom Lungu sought to appear in creating his social media image for public approval.

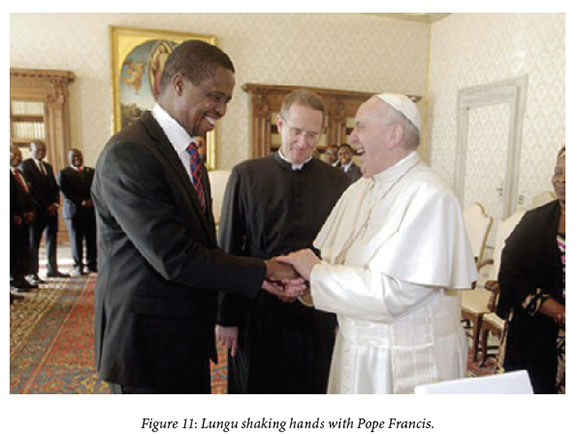

In period of presidntial compaign Lungu was always depicted in particular religious postures - with lifted hands, on the knees praying, or dancing in the church as in the pictures. Sometimes reading the Bible or paying homage to some clergy as in figure 10 and 11. Lungu always gave a morning verse and updated his Facebook profile after every church service or christian ceremony he attended.

In figure 10, Lungu is kneeling like a good Catholic before the newly consecrated Bishop of Mpika Diocese, Justine Mulenga. Lungu's kneeling is a power symbol of demonstrating his loyalty and submission to religious authority. Lungu's is playing politics of religious piety as means to derive power and moral authority from the church. Through the use of social media, the public preoccupation of Lungu's past lifestyle was essentially curtailed as he was constant portrayed as a saintly presidential candidate in opposition to HH who lacked a creative strategy to shake off Satanism accusations, a ghost that haunts him to this day. In actual fact, even Nerves Mumba is perceived with suspicion since he went into political alliance with HH. One Bishop told me that:

Things have substantially changed in [Mumba's] posture, his views about the church . He chose to go with HH, now that path spiritually has some issues, people will tell you that they are background issues of the Masonic involvement, but he has just brushed that aside and he has made public statements that if this individual was involved in the Masonic, by now demons would have manifested because "I am a man of God" ... I do not know where his views now stand as to what he considers to be the role of the church in politics.1

Lungu managed to navigate the Declaration by overcoming permeability between ecclesiastical engagement and social media representation. This political tactic was suited to appeal to most Zambian Pentecostal-Charismatics whose worldview is entrenched with the Declaration consciousness. Lungu would argue that "Zambians know the kind of leader that I am, and that I am a man of faith that walks with God ... I live my life and lead this country with Christian values."2

The case of Lungu highlights the precarious role of the churches in Zambia's politics since independence. Scholars have demonstrated how the first and second presidents of Zambia, Kenneth Kaunda, and Frederick Chiluba respectively used the platform of Christianity to advance their political positions.3 This history has meant that most politicians are constantly under pressure to adopt Christian posture so as to be accepted by most religious leaders. The constant arguments that make Christian faith appear infallible and imbued with supernatural power to shape sociopolitical attitudes and be a model for the state to command unquestionable allegiance and energy that demonstrated during liberation period and just after political decolonisation4 appears to have rendered Christian faith vulnerable to political abuse and weak to promote any just causes in postcolonial Zambia.

Too often Christian beliefs have been put in places where a sound and life-giving public policies should inform political intervention in society. However, Lungu's re-enacted the Declaration in social media spaces through presidential photos taken in places of worship has had the unintended consequences of giving a clear basis on which to judge his political leadership and governance. For instance, in the pastoral letter, "If You Want Peace, Work for Justice (Paul VI)," the Roman Catholic Bishops of Zambia denounced Christian politics of Lungu which they described as characterized by injustice, corruption, uncaring, manipulation, patronage, and intimidation of perceived government opponents.5 They argued, "Our democratic credentials which have not been much to go by at best of times have all but vanished in this nation that loudly claims to be 'God-fearing,' 'peace-loving' and 'Christian.'"6 They concluded that "people who inflict pain and suffering to their fellow human beings cannot claim to know God, let alone be 'Christian!'"7

While the focus of this article is on social media representation of Lungu as a devout Christian, it is also important to note that the process of Christianisation of Lungu has happened in a wider context of political struggle for some individuals who hoped to make political mileage out of their support for Lungu, in part, because some of them had fallen out of favour with the powerful establishment of Sata's government months before his death. Others were a faction from later former President Chiluba's Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD). For example, Lungu received enormous support from his tribesman, the former President of Zambia and MMD, Rupiah Banda. Banda provided substantial resources during campaign, including "four helicopters chartered in South Africa and numerous vehicles, in return for special considerations."8 Lungu also received support from former MMD ministers such as Felix C Mutati who was a faction President elect for MMD at the time of campaign,9 Given Lubinda and Rev Danny Pule and many other politicians who worked closely with Chiluba. In fact Pule was among religious politicians who popularised the discourse that "The main opposition wants to allow public worship of Satan and other satanic practices but God will not allow that."10These politicians were most likely to be also at the heart of Lungu's social media representation (or Christianisation).

Thus, the Christian nation religious ideology was implicated in Lungu's multi-patron coalition consisting individuals with various strategic interests such as business, politic position and religious who favoured policies that were more market-friendly to their particular needs than those previously advanced by Sata and his "leftist" coalition."11

Lungu drew power for political legitimization, moral authority and presidential worth by appealing to Pentecostal-Charismatic desire for a Christian president over Zambia. Lungu through social media photography covertly refashioned himself into 'the man of God' that Pentecostal-Charismatics desire to rule the nation. Rev Godfridah Sumaili, Minister of National Guidance and Religious Affairs summarises this well: "he [Lungu] is a man of God, he hears God, he has been obedient to God to create the Ministry [of Religious Affairs and National Guidance]."12 If this is a political consciousness that Pentecostal-Charismatics wish to continue modelling themselves around, they will easily lose their social credibility.

Already there is an outcry from the opposition through Nevers Mumba that "some Evangelical Pastors are failing to condemn the brutality taking place in Zambia because they have so compromised by their close relationship with the PF government." He further argues, "Zambians are expecting more from us but we are failing to call our political leaders to account. We have chosen silence when our people are being oppressed every day."13

This decry cannot be dismissed as mere political rhetoric, rather should be perceived as a call to Pentecostal-Charismatics to account for their political involvement. The church loses its authenticity when its missio-political consciousness becomes compromised and at worse reduced to an instrument for perpetuating the reigning political ideology, at that stage, the church remains a mere extension of the government institutions. In the context where Pentecostal-Charismatics are vulnerable to religious manipulation for political agenda, a pertinent question to ask is: How can Pentecostal-Charismatics become political formation spaces for alternative missio-political consciousness for their members?

5. Conclusion

This article examines the interactions of the Declaration, Lungu's social media presidential photography in various places of worship and 2016 presidential campaign. It demonstrates how Lungu was portrayed as a saintly presidential candidate through uploading photos on social media which taken of him in various ecclesiastical spaces. The article argues that Lungu's social media photography representation had nothing to do with actualisation of the Declaration by overcoming political corruption and nepotism, rather was a way of creating a religious-political ideology socially accepted in a so-called Christian nation. The Christian public image of Lungu was constructed as way of relating to religious political actors. These social media presidential photography functioned as subliminal texts underlying the Declaration as a religious-political state apparatus for political legitimization.

Bibliography

Primary

Richard Kasonde, interview with the Author, Chingola, 3 December 2016.

Pastor Haggai H. Mweene, interview with the author, youth pastor's office Northmead Assembly of God, 9 April 2016.

Rev Frazer Katanga, interview with the author, pastor's office Northmead Assembly of God, 9 April 2016.

Dr Danny Pule, Interview with the author, residential house in Lusaka 11th June 2016.

Dr Nevers Mumba, interview with the author, 23 Middle Way Street, Kabulonga, 30th November 2016.

Dr Liya Mutale Interview with the author, Twin Palm Street, Lusaka, 30 May 2016.

Secondary

Adogame, Afe (ed.), The Public Face of African New Religious Movements in Diaspora: Imagining the Religious "Other", (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2014). [ Links ]

Africa Arise - Zambia Chapter Beza International Ministries, Embracing Our Destiny: Redeeming Zambia in Religiousness - Africa's Tithe (Nairobi: Asaph Office Publications, 2016). [ Links ]

Ansari, Khalid Anis, "Pluralism, Civil Society and Subaltern Counterpublics: Reflecting on Contemporary Challenges in India through the Case-Study of the Pasmanda Movement", Pluralism Working Paper no 9 2011): 1-38, 31, [Online]. Available: www.pluralism.in [Accessed: 18 May 2017].

Barthes, Roland, "The Photographic Message", in Image-Music-Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Noonday Press, 1977 [1961]), 15-31.

Barthes, Roland, Mythologies, selected and translated from the French by Annette Lavers (The Noonday Press - New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1991). [ Links ]

Bourdieu, Pierre, Outline of a Theory of Practice, trans. Richard Nice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977). [ Links ]

Bourdieu, Pierre, The Logic of Practice, trans. Richard Nice (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990). [ Links ]

Bruns, Axel, Gunn Enli, Eli Skogerbo, Anders Olof Larsson, and Christian Christensen, The Routledge Companion to Social Media and Politics (New York: Routledge, 2016). [ Links ]

Chan, Stephen, "Presidentialism and Vice Presidentialism in a Commonwealth Country: A Cameo in Zambia," The Round Table 102: 5 (2013): 431-444.

Cheyeka, Austin, Church, State and Political Ethics in a Post-Colonial State: The Case of Zambia (Zomba: Kachere Series, 2008). [ Links ]

Christians for Lungu, "Vote for Edgar C. Lungu". [Online]. Available: http://www.christiansforlungu.org/ [Accessed: 28 October 16].

Cohen, Abner, Two-dimensional Man: An Essay on the Anthropology of Power and Symbolism in Complex Society (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974). [ Links ]

Davis, Christopher, "Seeing Africa as exceptional underestimates common experience of globalization," The Guardian (Monday, June 13, 2005). [Online]. Available: http://www.antropologi.info/anthropology/index.php?id=42ad66df4b750 [Accessed: 29 June 2018].

Dunn, John, Political Obligation in its Historical Context: Essays in Political Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1980). [ Links ]

Edwards, Janis L., "Visual Literacy and Visual Politics: Photojournalism and the 2004 Presidential Debates," Communication Quarterly 60, Issue 5 (2012): 681-697.

Flannery, Kent V., "The Cultural Evolution of Civilizations," Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 3 (1972): 399-426.

Freston, Paul, Evangelicals and Politics in Asia, Africa and Latin America (Cambridge: Cambridge University press, 2001). [ Links ]

Geertz, Clifford, Negara: The Theatre state in Nineteenth-century Bali (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980). [ Links ]

General Kanene Feat Chester, "Ulemu Kwa Alungu (Reply to Pilato)" [Online]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8GHxr1OAHZw [Accessed: 30 October 16].

Giddens, Anthony, Central Problems in Social Theory: Action, Structure, and Contradiction in Social Analysis (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979). [ Links ]

Giddens, Anthony, The Constitution of Society: Outline of a Theory of Structuration (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984). [ Links ]

Gifford, Paul, African Christianity: Its Public Role (London: Hurst & Company, 1998). [ Links ]

Grabe, Maria Elizabeth and Erik Page Bucy, Image bite politics: News and the visual framing of elections (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009). [ Links ]

Hall, Stuart, "The Work of Representation," in Stuart Hall (ed.), Representation, Cultural Representation and Signifying Practices (London: Thousand Oaks; New Delhi: Saga, 1997), 13-73.

Hall, Stuart, The Rediscovery of "Ideology": Return of the repressed in media studies, in Culture, society and the media (London: Methuen, 1982). [ Links ]

House of Chiefs, "On Religion and Leadership". [Online]. Available: http://www.houseofchiefs.com/2009/08/on-religion-and-leadership.html [Accessed: 26 July 2016].

Ihonvbere, Julius O., "The crisis of democratic consolidation in Zambia", Civilizations (1996): 83-09.

Kachikoti, Charles, "One Nation under God". [Online]. Available: http://www.zambian-economist.com/2010/03/one-nation-under-god.html [Accessed: 20 January 2017].

Kashoka, Ignatius (Chief Ngabwe), "The Ngabwe Covenant Made By Ignatius Mawala Kashoka, Chief Ngabwe the 6th, Mukutuma Mfumu the 2nd, On Tuesday 8 April 2014 At An Altar Of 5 Stones Raised At His Temporary Palace" (unpublished paper).

Kaunda, Chammah J and Mutale M Kaunda, " '. An Announcement of a New Spiritual Dispensation .' Pentecostalism and Nationalisation of Prayer in Zambia," forthcoming Journal of Theology for Southern Africa (2018).

Kaunda, Chammah J, "On the Road to Emmaus Together towards Life as Conversation Partner in Missiological Research," International Review of Mission 106, no, 1 (2017): 34-50.

Kaunda, Chammah J., 'The Altars Are Holding the Nation in Captivity': Zambian Pentecostalism, Nationality, and African Religio-Political Heritage," Religions 9, no., 5 (2018) 145; doi:10.3390/rel9050145.

Kaunda, Chammah J., "'From Fools for Christ to Fools for Politicians': A Critique of Zambian Pentecostal Theopolitical Imagination," International Bulletin of Mission Research, 41 (4): 296-311.

Kaunda, Chammah J., "Denial of African Agency: A Decolonial Theological Turn," Black Theology: An International Journal 13 (2015): 1-23.

Kertzer, David I., Ritual, Politics, and Power (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988). [ Links ]

Koenig-Visagie, Leandar, "The Representation of Gender in the Afrikaans Corporate Church: Fundamental Difference," in Sacred Selves: Essays on Gender, Religion and Popular Culture edited by Juliana Claassens and Stella Viljoen (Cape Town: Griffel Publishing, 2012), 159-186.

Lucero, Lisa J., "The Politics of Ritual," Current Anthropology 44.4 (2003): 523-558.

Lungu, Edgar, "President Edgar Lungu speaks at the Day of prayer & Fasting," [Online]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UDEw7zTM2rU, [Accessed: 18 October 2016].

Lusakatimes.com, "Catholic Bishops condemn HH arrest, say Zambia is now a dictatorship," (23 April 2017), [Online]. Available: https://www.lusakatimes.com/2017/04/23/catholic-bishops-condemn-hh-arrest-say-zambia-is-now-a-dictatorship/ [Accessed: 29 June 2018].

Lusakatimes.com, "HH's name appears on the register of the Freemasons, Bishop Chomba tells court," [Online]. Available: https://www.lusakatimes.com/2015/01/09/hhs-name-appears-register-freemasons-bishop-chomba-tells-court/ [Accessed: 30 October 2016].

Lusakatimes.com, "HH's name appears on the register of the Freemasons, Bishop Chomba tells court," [Online]. Available: https://www.lusakatimes.com/2015/01/09/hhs-name-appears-register-freemasons-bishop-chomba-tells-court/ [Accessed: 30 October 2016].

Lusakatimes.com, "I'm not a drunk-Edgar Lungu", [Online]. Available: https://www.lusakatimes.com/2014/11/19/im-drunk-edgar-lungu/ [Accessed: 17 April 2017].

Lynch, Gordon, The Sacred in the Modern World: A Cultural Sociological Approach (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012). [ Links ]

Machingura, Francis, Lovemore Togarasei and Ezra Chitando (eds.), Pentecostalism and Human Rights in Contemporary Zimbabwe (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars, 2018). [ Links ]

Mitchell, W.J.T., Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994). [ Links ]

Mukwita, Anthony, Against All Odds: Zambia's President Edgar Chagwa Lungu's Rough Journey to State House (Johannesburg: Partridge Africa Publishing, 2017). [ Links ]

Munshya, Elias, "The Referendum and Zambia's Christian nation declaration," [Online]. Available: https://lusakavoice.com/2016/07/08/the-referendum-and-zambias-christian-nation-declaration/ [Accessed: 20 January 2017].

Musonda, Charles, "Satanist Cannot Win Elections", New Vision, no. 1027 (6 June 2016): 4

Mutale, Liya, Transform to Transform Zambia (Lusaka: Self-Published, 2012). [ Links ]

Mutungu, Derek, "The Issachar Challenge", (unpublished 2015).

Mutungu, Derek, "Cathedral of Prayer for Nation" (unpublished PowerPoint, undated).

Mwenya, George, "Pres Lungu Back to His Chawama Roots," (4 January 2016) [Online]. Available: http://zambiareports.com/2016/01/04/preslungubacktohischawamaroots/ [Accessed: 2 June 2017].

Nandy, Ashis, "The Politics of Secularism and the Recovery of Religious Tolerance" in Secularism and Its Critics, edited by Rajeev Bhargava (Delhi: Oxford University Press: 1998): 321-344, 322.

Nandy, Ashis, Time Warps: The Insistent Politics of Silent and Evasive Pasts (New Delhi: Permanent Black, 2002), 62-63. [ Links ]

Phiri, Isabel A., "President Frederick J. T. Chiluba of Zambia: The Christian Nation and Democracy," Journal of Religion in Africa 33, no. 4 (2003): 401-28.

Pilato, "A Lungu Anabwela [Lungu is back with beers]", [Online]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n219562zvzk [Accessed: 2 June 2017].

Pilato, "Bashi Tasila [father of Tasila]," [Online]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ngsHowxrqyE [Accessed: 2 June 2017].

Pilato, "Tabalanda Sana Boyi - don't say too much" (argues that there is not freedom of speech in Lungu's presidency], [Online]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cjoHx-5dhlQ [Accessed: 2 June 2017].

Pilato, "Tata Ba Lungu [our father Lungu)", [Online]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dWRTpneMzlo [Accessed: 2 June 2017].

Pomaranski, Marcin, "'God Bless America': Prayer as a political ritual in the USA," Annales UMCS, Sectio K (Politologia) vol. 20, no, 1 (2013): 139-150.

Pype, Katrien, "Political billboards as contact zones: reflections on Urban Space, the Visual and Political Affect in Kabila's Kinshasa," Reflections on Urban Space, the Visual & Political Affect in Kabila's Kinshasa,' in Photography in Africa: Ethnographic Perspectives, edited by Richard Vokes Woodbridge (Suffok: Boydell & Brewer, 2012):187-204, 193.

Rappaport, Roy A., "Ritual, Sanctity, and Cybernetics," American Anthropologist 73 (1971): 59-76.

Rappaport, Roy A., Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999). [ Links ]

Schill, Dan, "The Visual Image and the Political Image: A Review of Visual Communication Research in the Field of Political Communication", Review of Communication, vol. 12, no, 2 (2012): 118-142.

Siachiwena, Hangala "Social policy reform in Zambia under President Lungu, 2015-2017," Centre For Social Science Research (CSSR) Working Paper No. 403 (April 2017). [Online]. Available: http://www.cssr.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/256/News/WP%20403%20 Siachiwena.pdf [Accessed: 29 June 2018].

Simbao, Ruth, "Cosmological Efficacy and the Politics of Sacred Place: Soli Rainmaking in Contemporary Zambia", African arts 47 no. 3 (2014): 40-57.

The High Commission of the Republic of Zambia New Delhi, India, "Bio of H.E. Edgar Chagwa Lungu - 6th Republican President of Zambia," [Online]. Available: http://www.zambiahighcomdelhi.org/news_detail.php?newsid=15 [Accessed: 2 June 2017].

Tresphor, Mutale C. Zambian Democracy Betrayed: Patrimonial Corruption in Zambia (Ndola, Zambia: Mutale. C. Tresphor, 2008). [ Links ]

Tsikerdekis, Michail and Sherali Zeadally, "Online deception in social media," Communications of the ACM 57.9 (2014): 72-80.

Van der Spuy, Anri, "Mirror, mirror upon the wall-is reality reflected at all?" Global Media Journal-African Edition 2, no. 1 (2008): 96-105.

Van Klinken, Adriaan, "Homosexuality, politics and Pentecostal nationalism in Zambia," Studies in World Christianity 20, no. 3 (2014): 259-81.

Van Leeuwen, Theo, "Semiotics and Iconography," in Handbook of Visual Analysis, edited by Theo Van Leeuwen and Carey Jewitt (London, Thousand Oaks, CA. and New Delhi: Sage, 2001), 92-118.

Wasserman, Herman, Media & Society: news media, representation and power. [Course notes]. (Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch, 2007). [ Links ]

Weber, Max, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, transl. by Talcott Parsons (London and New York: Routledge Classics, 1930 [2001]).

Webster, David L., "On Theocracies," American Anthropologist 78 (1976): 812-28.

Wolf, Eric R., Envisioning Power: Ideologies of Dominance and Crisis (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999). [ Links ]

Zambia Eye, "I am a man of faith that walks with God ... Lungu chides the nation on violence," [Online]. Available: http://zambianeye.com/i-am-a-man-of-faith-that-walks-with-god-lungu-chides-the-nation-on-violence/ [Accessed: 2 June 2017].

Zambia Reports, "HH Struggling to Shed off Satanist Tag," [Online]. Available: https://zambiareports.com/2015/01/09/hh-struggling-shed-satanist-tag/ [Accessed: 17 April 2017].

1 Bishop Anonymous, telephone conversation with the author, 8 December 2016.

2 Zambia Eye, "I am a man of faith that walks with God ... Lungu chides the nation on violence" [Online]. Available: http://zambianeye.com/i-am-a-man-of-faith-that-walks-with-god-lungu-chides-the-nation-on-violence/ [Accessed: 2 June 2017].

3 Phiri, "President Frederick J. T. Chiluba of Zambia," p. 401.

4 Christopher Davis, "Seeing Africa as exceptional underestimates common experience of globalization," The Guardian (Monday, June 13, 2005). [Online]. Available: http://www.antropologi.info/anthropology/index.php?id=42ad66df4b750 [Accessed: June 29, 2018].

5 Lusakatimes.com, "Catholic Bishops condemn HH arrest, say Zambia is now a dictatorship," (April 23, 2017). [Online]. Available: https://www.lusakatimes.com/2017/04/23/catholic-bishops-condemn-hh-arrest-say-zambia-is-now-a-dictatorship/ [Accessed: June 29, 2018].

6 Lusakatimes.com, "Catholic Bishops condemn HH arrest."

7 Lusakatimes.com, "Catholic Bishops condemn HH arrest."

8 Hangala Siachiwena, "Social policy reform in Zambia under President Lungu, 20152017," Centre For Social Science Research (CSSR) Working Paper No. 403 (April 2017) [Online]. Available: http://www.cssr.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/256/News/WP%2040 %20Siachiwena.pdf [Accessed: June 29, 2018].

9 Lusakatimes.com, "Mutati led MMD Faction resolves to form an alliance with PF," (May 23, 2016). [Online]. Available: https://www.lusakatimes.com/2016/05/23/mutatis-mmd-faction-resolves-form-alliance-pf/ [Accessed: June 29, 2018].

10 Danny Pule, "Zambia's Main Opposition Leader Will Die Before 2021- Dan Pule," Zambian Observer (May 21, 2018). [Online]. Available: https://www.zambianobserver.com/zambias-main-opposition-leader-will-die-before-2021-dan-pule/ [Accessed: June 29, 2018].

11 Siachiwena, "Social policy reform in Zambia under President Lungu, 2015-2017," 10.

12 Rev Godfridah Sumaili, "A Christian Nation", TV 3 Christian Channel (10 December 2016).

13 Lusaka.com, "Pentecostals are an embarrassment - Nevers Mumba", (April 26, 2017). [Online]. Available: https://www.lusakatimes.com/2017/04/26/pentecostalsembarrassmentneversmumba/ ([Accessed: June 2, 2017].