Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

On-line version ISSN 2413-9467

Print version ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.3 n.2 Stellenbosch 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2017.v3n2.a20

ARTICLES

Eucharistic symbols: Other emerging meanings in the Anglican Church of Kenya

Kiarie George

University of South Africa Karatina University, Kenya. kiariegeorge77@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This article is set to argue that for a long time Eucharistie symbols have been interpreted in different contexts, with a universal understanding as the body and blood of Jesus Christ. However, recent studies in the Anglican Church of Kenya, diocese of Thika, reveal other emerging meanings of these symbols among Christians. Such meanings include foreign food product, prohibited product, symbol of modernity and finally symbol of neo-colonialism. This article is informed by qualitative data obtained from adherents in the diocese of Thika between 2013 and 2014.

Key words: Anglican Church; bread; Eucharistie symbols; Kenya; missionary and wine

1. Introduction

The Eucharistic symbols in the Anglican tradition are so central in her sacramental life. This unique Anglican identity was transferred in the Anglican Church of Kenya (ACK) when the English missionaries (that is the Church Mission Society - CMS) introduced the Christian faith in 1844. This was possible because there was stubborn reluctance among the English missionaries to establish independent dioceses overseas, far removed from direct allegiance to the crown.1 As such, the ACK became a carbon copy of the Church of England in terms of her liturgical and ecclesiological life, despite these two Churches being from two different contexts. Therefore, the two critical questions that this article raises are: How were these Eucharistie symbols understood in the Kenyan context? Which meanings were these Eucharistic symbols given because they were foreign religious symbols in a new context? In the subsequent sections of this article, I will attempt to answer the above questions.

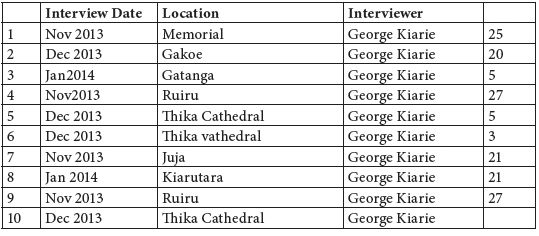

This article relied on raw data that was generated from both empirical and non-empirical methods. The raw data was collected from twenty-five parishes, where the respondents comprised of both the ordained and laity in the ACK diocese of Thika. Semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions and questionnaires were used in data collection. Sixty-seven respondents were engaged in this study and were purposively sampled. The researcher picked sixty-seven respondents from the diocese of Thika that were well-versed in and had a deeper knowledge of the Eucharistic symbols.2 The collected data was analysed qualitatively.3

2. The theological understanding of the Eucharistic symbols in the ACK

The Eucharistic symbols in the ACK are the bread (also referred to as wafers) and wine. These symbols were instituted by Christ as the visible signs of invisible realities that point beyond themselves as they bring the transcendent within the range of human understanding.4 C. S. Meyer then could not hesitate to note that:

Our saviour Christ called the material bread which he broke, his body, and the wine, which was the fruit of the vine, his blood. And yet he spake not this to the intent that men should think that the material bread is his very body, or that his very body is material bread; neither that wine made of grapes. But to signify unto us, as St. Paul saith, that the cup is a communion of Christ's blood that was shed for us, and the bread is a communion of his flesh that was crucified for us.5

Certainly, these Eucharistie symbols represent the body and blood of Christ that nourishes believers both physically and spiritually. For through celebration of the Eucharistic meal using these two symbols in the church, the Anglican reformer Thomas Cranmer observed as every human being is carnally fed and nourished in his or her body by meat and drink, even so is every good Christian spiritually fed and nourished in his or her soul by the flesh and blood of our saviour Christ.6 It then becomes certain that these Eucharistic symbols are celebrated in a local ecclesiastical context to communicate spiritual strength to believers in their Christian faith.

Besides spiritual nourishment and strength, these Eucharistic symbols saturate the believer's life with God's grace because they point beyond them and convey the grace of God. Welchman states that Christ did not only become a badge of tokens to the Christian but rather certain sure witnesses and effectual signs of grace in God's goodwill toward humanity.7 Through these Eucharistic symbols, God's redemptive work is evident in the life of humanity, such that they not only quicken but also strengthen and confirm believer's faith in God. This implies that the conveyed grace is God's gift to humanity that strengthens and makes humanity inclined toward God. This grace of God, according to Stephen Neil, should be exercised for the good of the church, not for self-edification.8

Consequently, these Eucharistic symbols unite believers both vertically and horizontally. This gesture of sharing one bread and one cup becomes a sign of their unity and affirms their oneness with one another, because despite being many they are one body, for they all share one bread.9 While believers are united with one another, they also encounter God when these Eucharistic symbols are celebrated in a meal, since the self-emptying God (Kenosis) and self-surrendering humanity meet one another. As G. W. H. Lampe argues, this unique encounter between God and believers in the Lord's Table culminates in "individual union with God, and both God and man [sic], in whom the self-giving of God and the self-surrender of man [sic] meet."10 Furthermore, it is worth noting that this encounter with the self-emptying God not only unites believers with God but also guarantees eternal life to believers. Cranmer was persuaded that "touching this meat and drink of the body and blood of Christ, it is true, both he eateth and drinketh them, hath everlasting life, and also he that eateth and drinketh them not, hath not everlasting life."11

While Cranmer focuses on the vertical dimension of salvation conveyed by the Eucharistic symbols through forgiveness of sins, scholars such as H. Davies and Francis Moloney provide the horizontal dimension of salvation.12They perceive that these Eucharistic symbols should communicate socioeconomic and political liberation to those living in a world characterised by inequality, ethnic tensions that divide our countries along tribal lines between 'us' and 'them', and corruption, among other social evils in our societies. Thus these Eucharistic symbols communicate the liberative salvation that Jesse Mugambi perceives as the restoration of hope and human dignity to the young people, children and discriminated women with no social status in our patriarchal societies that do not speak life that Christ brought to humanity.13

This dimension of salvation in the Eucharistic symbols brings true communion with God and the abolition of all injustice and exploitation. This signifies that liberative salvation in the Eucharistic symbols ensures that believers are not only nourished spiritually, but also physically. Hence, among thousands starving and dying of hunger, the symbols condemn and challenge all the unjust structures and powers that threaten life in abundance because Christ the bread of life came for all to have life in totality. For as assured in the Lord's Prayer where we pray for 'our daily bread,' it means God provides enough bread for all humanity in the globe; it is only our unjust systems that make some sleep hungry while others have more than enough and run to waste out of human selfishness.14 In this note, it is right to say that the Eucharistic symbols should communicate life to the dying, peace to those in war-torn countries and equality to those discriminated against on account of their race, gender, age or religion. In addition, Bénézet Bujo is convinced that these Eucharistic symbols should communicate physical nourishment to the hungry lest celebration of these symbols in our vast cathedrals become sweet poison rather than a wellspring of life to our communicants.15

Finally, the Eucharistic symbols point towards eschaton and William Crockett rightly posits that the Eucharistic meal is an anticipation of the eschatological meal of the Messiah where the communicants look towards the future.16 In this anticipation, believers are assured of full communion with Christ and one another. Thus believers will be privileged to eternally dine with Christ as their host and them as Christ's guest. In honour and remembrance of the eschatological anticipation, the ACK continues to celebrate these Eucharistic symbols in imitation of what Jesus did, in remembrance of Him until He comes again. As John Mbiti perceives, regular celebration of these Eucharistic symbols in a meal becomes a rich experience of the eschatological bliss, where any disappointment over the delay of Christ's coming is again neutralized.17 Moreover, eschatology gives us hope in God for the creation of the world, where God will destroy the present condition and out of the old world create a new world whose nature is imperishable.18 This means that in our society characterized by corruption, ethnic cleansing, inequality, discrimination and environmental degradation, the Eucharistic symbols give us hope of God's creation of a new world that is an egalitarian society. In this society, men and women will dine at the same table as equals without cultural bias; everyone in the society will have enough to feed on because the Eucharistic meal communicates and provides abundance and hospitality to the human race.19It communicates healing and reconciliation of our broken society amidst the HIV and AIDS pandemic, ethnic cleansing, xenophobic attacks, greed for power and corruption.

Therefore, it is true to say that the Eucharistic symbols communicate the message of God's grace, unity among the believers, spiritual nourishment, salvation, equality of all humankind, plenty to the hungry, stewardship of mother earth and anticipation of the coming kingdom of God on earth as it is in heaven.

3. The meaning of the Eucharistic symbols in the ACK

The body and blood of Christ

According to scholars such as Peter Berger, Thomas Luckmann and Robert Pazmino, the meaning of a particular thing is socially constructed in society by human beings because they are meaning-making beings.20When the Eucharistic symbols were introduced in the ACK, the Christians gave meaning to these symbols. It is right to say that they were convinced that these symbols represent the body and blood of Jesus Christ. This was clearly articulated that:

These are symbolic instruments used to signify what Jesus did during the last supper. Within that time, it was the normal bread used for the dinner. But this time he gives it a new meaning and the wine, which was used to be taken by the Jewish also, gave a new meaning during that time yes.21

Another respondent 02#, shared similar thoughts with respondent 01# and she argued that bread and wine "symbolize the body and blood of Christ as we commemorate the last supper."22 In light of these responses, it is crystal clear that ACK Christians have internalized the meaning of the Eucharistic symbols in their own context, in the way Martin Ott perceives that the role and task of theology is to re-interpret classical questions in different contexts to establish their relevance.23 From the ACK Christians we deduce that these symbols were initiated by Christ who gave them new meaning from the Passover meal. John W. Howe and Sam C. Pascoe demonstrate this and argue that they symbolized Israel's deliverance from the corruption of Egypt. However, Christ gave them new meaning to signify his body and blood broken and poured out to liberate humanity from the corruption of sin.24 This affirms that these Eucharistic symbols are layered with meaning and change with time, but to the ACK Christians "these are commemorative meal's bread and wine, representing the invisible and divine presence of the body and blood of Christ."25 For as Gerald Arbuckle observed, symbol is more than just a sign, because signs only point to the object signified but a symbol by its very dynamism represents the object.26 This means that when ACK Christians see Eucharistic symbols, these symbols not only point to Jesus, but represent the body and blood of Christ, because symbols have power within them.

In light of this socially constructed meaning of the Eucharistic symbols, the ACK Christians affirm that they share the universal meaning of these symbols as the body and blood of Christ with other Christians in the body of Christ. Therefore, Bernard Cooke and Gary Macy postulate that some symbols like the Eucharistic symbols in this case seem to be universal.27

However, the big question remains: why then did they have other meanings, as explained below?

4. Other emerging meanings of the Eucharistie symbols in the ACK

Sociologist Nijole Benokraitis introduces this section by arguing that the nature of symbols (including religious symbols like bread and wine) changes over time.28 He observed this is as a result of symbols potentiality to communicate different meanings in different contexts and therefore change over time. With this in mind, this justifies the rationale of other emerging meanings of the Eucharistic symbols in the ACK. Hence, the following are the other emerging meanings of the Eucharistic symbols in the ACK.

Foreign Products

One of the emerging meanings of the Eucharistic symbols in the ACK is that these symbols are foreign food products. To understand this phenomenon of emerging meanings of symbols, philosopher Rose Aden observed that religious symbols do not have permanent meaning.29 The ripple effect is that besides Eucharistic symbols understood as symbols that represent the body and blood of Christ, the ACK Christians also view them as 'foreign' food products since they are imported into Kenya. While wine is exclusively imported from Cyprus and bread manufactured locally, bread still has a 'foreign' connotation. This is because its translation as mugate in Gikuyu language, for instance, bears a foreign connotation, since this word mugate for bread was borrowed from the Swahili word mkate. Philip Tovey could not hesitate to say "the language used illustrates some of the problems and the use of loan words and imported materials help to foster the foreignness of the Holy Communion."30

This perception of Eucharistic symbols as 'foreign' products was evident in ACK Christians. For instance, respondent 04# maintained for I believe even the wine and bread were just brought .. .'31 This means as imported food products in the ACK '.. ..it has no major significance .. .'32 to the Christians. Following the same line of thought, one Archdeacon in the ACK said:

In Palestine, these elements were very significant to locals there. When the gospel was disseminated in other parts of the world they did not contextualize the gospel, such that when they came here in Africa they found no grapes, but we had oranges, they borrowed directly from Palestine, thus wheat was a Palestine product with significance.33

Then, in light of these ACK Christians' argument it is true to affirm that these symbols carry with them foreign connotations or meanings since discourses like 'just brought', 'imported' and 'borrowed' all depict foreignness and hence with 'no major significant role' in their lives. This implies that when used for celebrating Eucharistic meals they alienate people from their own context because they do not communicate to the ACK Christians' hearts, minds and souls. The reason is the significance of symbols is more attached to their place of origin than in other contexts and when transferred into another context they end up being insignificant in the life of the people in that new context. Towards this end, this clearly affirms that symbols are cultural and communicate adequately to the people in their own context. Aden, in support of this idea, continues to say "even if "outsiders" are told what the symbols represent, they still do not know what they mean. For those who are not immersed in the cultural context of the symbol, the relationship between the symbol and what it stands for may seem quite arbitrary."34 With this understanding, it helps us answer's Mercy Oduyoye's quagmire of why the African traditional oaths and covenants, especially the use of kola nuts is more abiding than Eucharistic symbols.35

A possible reason is the symbol of kola nuts identifies more with natives in West Africa and communicates to their inner senses than Eucharistic symbols that are foreign food products.

Therefore, it is right to concur with Paul Gibson on this debate at Anglican Communion level that these Eucharistic symbols in some local cultures carry different meanings because they are 'foreign' imports.36 As foreign food products with a different meaning in Kenya, the ACK Christians are thus persuaded that these Eucharistic symbols are foreign symbols 'with significance to their place of origin' and there is a need to inculturate them in the ACK context in order to communicate deeply to the Christians in their cultural milieu. John Gatu, former moderator of General Assembly in the Presbyterian Church in East Africa does support the idea of foreignness of the Eucharistic symbols. He argues that these symbols do not convey the idea of sacrificial offering which is so central in the Kikuyu religious life where bulls, cows, sheep or goats were normally killed to provide this.37Gatu suggests we use meat to substitute bread since the symbol of meat communicates and invokes the Kikuyu sacrificial worldview more than bread. As foreign products imported into Kenya these Eucharistic symbols are very expensive to the Christians and what ultimately transpires is that it is an occasional meal in the ACK rather than the regular meal that Christ commanded his followers to be taking in remembrance of him. This phenomenon in most Churches in Kenya affects the pastoral implication that these Eucharistic symbols should produce and in return they have become insignificant to them. This forms a good basis for theological debate of whether Eucharistic symbols should be substituted with locally available food products in the ACK.

Prohibited products

Another emerging meaning of the Eucharistic symbols in the ACK is that these are prohibited food products, only to be partaken or encountered at Communion. This meaning is expressed by respondent 06# who argued, "If you go to Cyprus wine is available in every meal but in our place here we do not use wine in all situations, only in the Church."38 As such wine in Cyprus is part of their menu in their ordinary meals, as well as in their ecclesiastical settings. This is totally different in the ACK, where wine is perceived as a sacred product exclusively for use in the Church and not elsewhere, the way CMS missionaries socially conditioned Anglican Christians in Kenya when they introduced these symbols. Gatu clearly articulates this and states that "if one is found drinking this same wine in a restaurant or a pub this would amount to being in a state of inebriety, punishable by excommunication or temporary suspension from the Lord's Table."39 Due to this prohibition, the ACK Christians socially reconstructed meaning around these Eucharistic symbols as prohibited food products only to be encountered at Communion. Signifying that the Eucharistic symbols reveal the nature of symbols that, "man does not live by symbols alone, but man orders and interprets his reality by his symbols, and reconstructs it."40

While Christ invites all to partake in these Eucharistic symbols in his meal, of late these symbols are prohibited to polygamous, single mothers and other men who have not solemnised their marriage in the visible Church of Christ.41 Despite all these groups being baptised and confirmed in the Anglican Church, they do not qualify to partake of these Eucharistic symbols. So, these symbols become sacred food products for a few chosen people in the body of Christ, in spite of the visible Church being for all who are repentant and desiring to partake of these symbols in remembrance of the death of Christ. With this in mind, the ACK Christians could not hesitate to refer to these Eucharistic symbols as outlawed products. In this line of thought, Tovey brings to our attention that a similar meaning of the Eucharistic symbols as prohibited product is shared by the Anglicans in the Islamic states.42 Though similar to the meaning in the Kenyan context, the diverging point is the reason behind their ban. While in Kenya it is an issue of Christians' spiritual integrity, in the other parts of the world it is more to do with a political system that restricts imports of all alcoholic products into the country.

Symbol of modernity

The other meaning of the Eucharistic symbols in the ACK is the perception that these symbols are vehicles of modernity. This is clear from the discourses such as comparison between the use of indigenous symbols of nourishment or food with bread and wine in the Eucharistic meal. The respondent 07# illustrated here that:

Nduma and ngwaci [translation for arrow roots and sweet potatoes] these are very local products so to one who is taking the modern wine and bread they may see others as inferior and in fact they may also feel inferior those taking nduma because these are things that they have been brought up with from childhood to this level.43

What can be deduced from this response is that these Eucharistic symbols are viewed as symbols of modernity to the ACK Christians. This is conspicuous in their discourses such as 'modern wine and bread'. To the local food products such as nduma or ngwaci, these are thought to be inferior or primitive, disclosing that the ACK Christians identify most with these Eucharistic symbols in the form they were first introduced into Kenya by English missionaries. This confirms that with time the ACK Christians fell in love with these symbols not necessarily because they communicate to them spiritually, but for cultural and religious identity.44 According to David Gitari and Elijah Mbonigaba, this is a result of the ACK desire to identify with the acquired 'western' civilization that is envied by many in African societies.45

The implication of this phenomenon and meaning of the Eucharistic symbols in the ACK is stratification of different Churches in the different contexts between the 'haves' and 'have nots' In this study, the article discovered that if a Church can afford to use these imported Eucharistic symbols it is perceived as a modern or civilized Church and vice versa. This finds support in the words echoed by respondent 08# who attempts to answer why their Church uses bread and wine. She retorted because 'we are in a modern world.'46 As such, this article attests that symbols do divide; the way it is experienced in the ACK between the lucrative congregations that can afford these imported foreign symbols and the poor congregations that struggle to make ends meet.

While these Eucharistic symbols are referred to as symbols of modernity or luxurious items to the ACK Christians, this is very ironical because this Church falls in a context where most people live on less than one dollar a day. However, Michael F. Nabofa's argument challenges why there is this discrepancy, when he postulates that the nature of symbols is to mirror social and religious reality and the reality in the ACK is that bread and wine are attached to modernity or civilization.47 Hence, the Christians in the ACK identify most with these symbols because they are linked with modernity that is envied by many.

Symbol of neo-colonialism

The final meaning of the Eucharistic symbols is the perception that these are symbols of neo-colonialism. This meaning emerged as a result of the ACK Christians reflecting more on these symbols in relation to their realities in life. According to Theo Sundermeier, symbols make one think and articulate life around one's world.48 In support of this argument this article cites respondent 09# who could not fathom why more emphasis is put on bread and wine while some of these symbols are not readily available in some parts of the country? She therefore posed: "we need to ask ourselves if universalism means colonialism or is part of neo-colonialism."49 Her quagmire is a result of theological debates that overemphasize the unity of the universal Church of Christ while the perpetual use of bread and wine in different ecclesiastical contexts according to Eugene Uzukwu is a matter of discipline and not dogma.50 Thus the incessant use of these Eucharistic symbols in the ACK depicts the level of neo-colonialism among its adherents and particularly the colonialism of mind. This prompted respondent 010# not to bury his head in the sand; rather, he maintained:

... those who brought good news first had a hidden agenda, so even when bread was introduced they knew they had to convince this person that anything else is not good and that (is) why when we peruse what else to use (it) become(s) difficult as our minds have assimilated bread and wine. But if we may be taught and convinced that arrow root in Holy Communion is the best and the people appreciate that we can move away from multitude of problems.51

From this response then, one notes the aspect of colonialism is palpable in the respondent's conviction that the missionaries who introduced these symbols had a 'hidden agenda' because they emphatically asserted 'anything else is not good.' This means ACK Christians were cognitively conditioned that nothing else can represent the body and blood of Christ apart from the imported European food products perceived as orthodoxy. For Bujo, these Eucharistic symbols serve the commercial interests of Europeans,52 who capitalise on the African theological ignorance for betterment of their life. Then the ACK Christians are persuaded that the missionaries succeeded to convince them because according to Solomon Oduma-Aboh one of the crucial roles of symbols in the community is a powerful instrument to indoctrinate people with the prime goal of maintaining order and harmony.53 Therefore, respondent 010# proposes the need to decolonize such a mind-set among the ACK Christians because this will enable them to "move away from multitude of problems."

5. Conclusion

This article has elucidated the fundamental role of the Eucharistic symbols in the life of ACK Christians since these symbols were introduced in Kenya. The article established that these symbols not only touch the spiritual aspect of the Christians, but the totality of the Christians' life because they have vertical and horizontal dimensions. This means they communicate eternal life and meet the daily needs of the Christians in their unique contexts. Thus these Eucharistic symbols play a holistic role in the society. The article also contends that symbols when transferred to a new context are deemed to be interpreted differently and ultimately attract diverse meanings. Therefore, this article concludes that it is imperative to inculturate these Eucharistic symbols when moved to a new context with the ultimate goal of communicating to the indigenous people in their own cultural milieu.

Bibliography

Published works

Aden, Rose 2013. Religion Today: A Critical Thinking Approach to Religious Studies. Plymouth: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. [ Links ]

Arbuckle, Gerald A 2001. Earthing the Gospel: An Inculturation Handbook for Pastoral Workers. West Broadway: Wipf & Stock Publishers. [ Links ]

Benokraitis, Nijole 2015. Introduction to Sociology: Student Handbook 4. Stampford: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

Berger, Peter. L and Luckmann, Thomas 1966. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Boyatzis, Richard E. 1998. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Bujo, Bénézet 1992. African Theology in its Social Context. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Cooke, Bernard and Gary, Macy 2005. Christian Symbols and Ritual: An Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Creswell, John W and Clark, Vicki L Plano 2007. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Crocket, William R 1989. Eucharist: Symbol of Transformation. New York: Pueblo. [ Links ]

Firth, Raymond 1973. Symbols: Public and Private. Abingdon: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. [ Links ]

Gathogo, Julius 2011. Christ's Hospitality from an African Theological Perspective: Lessons from Christ's Ideal Hospitality for Africa. Saarbrucken: Lap Lambert Academic Publishing. [ Links ]

Gatu, John 2006. Joyfully Christian, Truly African. Nairobi: Acton Publishers. [ Links ]

Gitari, David (ed.) 1994. Anglican Liturgical Inculturation in Africa: The Kanamai Statement 'African Culture and Anglican Liturgy' with Introduction Papers Read at Kanamai and a First Response. Bramcote, Nottingham: Groove Books Ltd. [ Links ]

Howe, John W and Sam C Pascoe 2010. Our Anglican Heritage: Can an Ancient Church be a Church of the Future? Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers. [ Links ]

Kiarie, George and Joshua Muoki. 'The Changing Understanding of Eucharistic Meal among the Kikuyu Communicants of Thika Diocese in the Anglican Church of Kenya' in Stellenbosch Theological Journal, vol. 2, no. 2, (2016): 295-320. [ Links ]

Kiarie, George and Joshua Muoki. 'Factors inhibiting inculturation of the Holy Communion symbols in the Anglican Church in Kenya: A case study of the diocese of Thika,' Missionalia Journal vol. 44, no. 3 (2016): 301-320. [ Links ]

Mbiti, John Samuel 1971. New Testament Eschatology in an African Background: A Story of the Encounter between New Testament Theology and African Tradition Concepts. London: SPCK. [ Links ]

Mbonigaba, Elisha G 1994. "The Indigenization," in David Gitari (ed.), Anglican Liturgical Inculturation in Africa: The Kanamai Statement 'African Culture and Anglican Liturgy' with Introduction Papers Read at Kanamai and a First Response, edited by,, Bramcote, Nottingham: Groove Books Ltd, pp. 20-32. [ Links ]

Meyer, Carl S 1961. Cranmers Selected Writings. London: SPCK. [ Links ]

Moltmann, Jürgen 1996. The Coming of God, trans. Margaret Kohl. London: SCM Press Ltd. [ Links ]

Mugambi, Jesse (ed.) 1997. The Church and Reconstruction of Africa: Theological Considerations. Nairobi: All African Conferences of Churches. [ Links ]

Oduyoye, Mercy Amba, "The Values of African Religious Beliefs and Practices for Christian Theology," in Kofi Appiah-Kubi and Sergio Torres (eds.), African Theology en Route: A Paper from the Pan African Conference of Third World Theologians December 17- 23, 1977 (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1979), pp. 109-116.

Ott, Martin 2000. African Theology in Images. Blantyre: Christian Literature Association in Malawi. [ Links ]

Pazmino, Robert W 1999. Foundational Issues in Christian Education: An Introduction in Evangelical Perspective Second Edition. Grand Rapids: Bakers Books. [ Links ]

Tovey, Philip 2004. Inculturation of Christian Worship: Exploring the Eucharist. Hants, England: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. [ Links ]

Internet sources

Paul Gibson. 2005. "Eucharistic Food and Drink: A Report of the Inter-Anglican Liturgical Commission to the Anglican Consultative Council." [Online] Available: http://www.anglicancommunion.org/resources/liturgy/docs/appendix%205.pdf [Accessed 29/11/2017].

Tovey, Phillip on "Inculturation: The Bread and Wine at the Eucharist" [Online] Available: https://ism.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/Inculturation%20the%20Bread.pdf [Accessed 29/11/2017].

World Food Programme. [Online] Available: https://www.wfp.org/content/factsheet-food-security-analysis [Accessed 20/07/2017].

Oral Interviews

1 FW Dillistone, The Power of Symbols (London: SCM Press Ltd, 1986), p. 209.

2 John W. Creswell and Vicki L. Plano Clark, Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2007), p. 112.

3 Richard E, Boyatzis, Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 1998), p. vi.

4 John Macquarrie, A Guide to the Sacraments (London: SCM Press, 1997), p. 31.

5 C. S. Meyer, Cranmers Selected Writings (London: SPCK, 1961), 31.

6 Thomas Cranmer, Cranmer on the Lord's Supper: A Defence of the True and Catholic Doctrine of Sacrament (Kent: Focused Christian Ministries and Harrison Trust, 1987), p. 16.

7 Welchman, The Thirty Nine Articles of the Church of England (London: Oxford Theatre, MDCCLVII), p. 61.

8 Stephen Neil, "Holy Communion in the Anglican Church", in Martin Hugh, ed., The Holy Communion (London: SCM Press Ltd, 1947), p. 62.

9 Anglican Church of Kenya, Our Modern Service (Nairobi: Uzima Press, 2002), p. 82.

10 G.W.H Lampe, Doctrine in the Church of England (London: SPCK, 1982), p. 165.

11 Thomas Cranmer, Cranmer on the Lord s Supper, p. 4.

12 H. Davies, Bread of Life and Cup of Joy (Grand Rapid, Michigan: William B Eerdmans 1993), 180 and Francis J. Moloney, A Body Broken for a Broken People, Eucharist in the New Testament. Revised Edition (Burwood. Victoria: Collins Dove, 1997), p. 156.

13 Jesse Mugambi (ed.) The Church and Reconstruction of Africa: Theological Considerations (Nairobi: All African Conferences of Churches, 1997), p. 74.

14 See https://www.wfp.org/content/factsheet-food-security-analysis [Accessed on 20/07/2017].

15 Bénézet Bujo, African Theology in its Social Context (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1992), p. 100.

16 William R Crocket, Eucharist: Symbol of Transformation (New York: Pueblo Publishing Company, 1989), p. 276.

17 John. S Mbiti, New Testament Eschatology in an African Background: A Story of the Encounter between New Testament Theology and African Tradition Concepts (London: SPCK, 1971), p. 102.

18 Jürgen Moltmann (translated by Margaret Kohl), The Coming of God (London: SCM Press Ltd, 1996), p. 270.

19 Julius Gathogo, Christ's Hospitality from an African Theological Perspective: Lessons from Christ's Ideal Hospitality for Africa (Saarbrucken: Lambert Academic Publishing, 2011), pp. 158-159.

20 Peter L Berger and Thomas Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1966), p. 1; Robert W Pazmino, Foundational Issues in Christian Education: An Introduction in Evangelical Perspective, Second Edition (Grand Rapids: Bakers Books, 1999), p. 161.

21 Interview with respondent, Field Notes 01# (Memorial Parish, 25 November 2013).

22 Interview with respondent, Field Notes 02# (Gakoe Parish, 20 December 2013).

23 See Martin Ott, African Theology in Images (Blantyre: Christian Literature Association

in Malawi, 2000).

24 John W Howe and Sam C Pascoe, Our Anglican Heritage: Can an Ancient Church be a Church? (Eugene OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2010), p. 81.

25 Interview with respondent, Field Notes 03# (Gatanga Parish, 15 January 2014).

26 Gerald A. Arbuckle, Earthing the Gospel: An Inculturation Handbook for Pastoral Workers (West Broadway: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2001), p. 29.

27 Bernard Cooke and Macy Gary, Christian Symbols and Ritual: An Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 11.

28 Nijole Benokraitis, Introduction to Sociology: Student Handbook 4 (Stampford: Cengage Learning, 2015), p. 41.

29 Rose Aden, Religion Today: A Critical Thinking Approach to Religious Studies (Plymouth: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2013), p. 144.

30 Philip Tovey, Inculturation of Christian Worship: Exploring the Eucharist (Hants,

England: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2004), p. 46.

31 Interview with respondent, Field Notes 04# (Ruiru Parish, 27 November 2013).

32 Interview with respondent, Field Notes 01# (Memorial Parish, 25 November 2013).

33 Interview with respondent, Field Notes 05# (Thika Cathedral, 5 December 2013).

34 Rose Aden, Religion Today, pp. 145.

35 Mercy Amba Oduyoye, "The Values of African Religious Beliefs and Practices for Christian Theology," in Kofi Appiah-Kubi and Sergio Torres (eds.), African Theology en Route: A Paper from the Pan African Conference of Third World Theologians December 17- 23, 1977 (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1979), pp. 109-116. Here: p. 113.

36 Paul Gibson, 2005. "Eucharistic Food and Drink: A Report of the Inter-Anglican Liturgical Commission to the Anglican Consultative Council." [Online]. Available: http://www.anglicancommunion.org/resources/liturgy/docs/appendix%205.pdf [Accessed 29/11/2017].

37 John Gatu, Joyfully Christian, Truly African (Nairobi: Acton Publishers, 2006), p. 30.

38 Interview with respondent, Field Notes 06# (Thika Cathedral, 3 December 2013).

39 Gatu, Joyfully Christian, p. 29.

40 Raymond Firth, Symbols: Public and Private (Abingdon: George Allen and Unwin Ltd,

1973), p. 20.

41 George Kiarie and Joshua Muoki, "The Changing Understanding of Eucharistic Meal among the Kikuyu Communicants of Thika Diocese in the Anglican Church of Kenya" in Stellenbosch Theological Journal, Vol 2, No 2, 295-320 (2016), 303.

42 Tovey on "Inculturation: The Bread and Wine at the Eucharist" [Online] Available: https://ism.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/Inculturation%20the%20Bread.pdf [Accessed 29/11/2017].

43 Interview with respondent, Field Notes 07# (Juja Parish, 21 November 2013).

44 See George Kiarie, "Factors inhibiting inculturation of the Holy Communion symbols in the Anglican Church in Kenya: A case study of the diocese of Thika," Missionalia Journal, vol. 44, no. 3 (2016): 301-320.

45 David Gitari (ed.), Anglican Liturgical Inculturation in Africa: The Kanamai Statement 'African Culture and Anglican Liturgy' with Introduction Papers Read at Kanamai and a First Response (Bramcote, Nottingham: Groove Books Ltd, 1994), p. 37. Elisha G. Mbonigaba, "The Indigenization," in David Gitari (ed.), Anglican Liturgical Inculturation in Africa, p. 23.

46 Interview with respondent, Field Notes 08# (Kiarutara Parish, 21 January 2014).

47 Micheal Y. Nabofa, Symbolism in African Traditional Religion (Ibadan: Paperback Publishers, 1994), p. 45.

48 Theo Sundermeier, The Individual and Community in African Traditional Religions (Hamburg: Lit Verlag, 1998), p. 40.

49 Interview with respondent, Field Notes 09# (Ruiru Parish, 27 November 2013).

50 Eugene Uzukwu, "Foods and Drink in Africa and the Christian Eucharist", African Ecclesial Review, vol. 22, no. 6 (1980):370-385. Here: p. 381.

51 Interview with respondent, Field Notes 010# (Thika Cathedral, 3 December 2013).

52 Bénézet Bujo, Foundations of an African Ethics: Beyond the Universal Claims of Western Morality (New York: Crossroad, 2001).

53 Solomon Ochepa Oduma-Aboh, 201, "Religio-Cultural Expressions of Number Symbolism among Idoma People of Nigeria," Iloria Journal of Religious Studies, vol., 4 no. 1 (2014), 140.