Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2413-9467

versão impressa ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.2 no.2 Stellenbosch 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2016.v2n2.a22

ARTICLES

Some thoughts around developing missional South African congregations based upon the church rediscovering its identity in the grace of God

Tucker, Roger

University of the Free State. roger@tuckerza.com

ABSTRACT

The UPCSA have established the development of missional congregations as the overarching goal of the denomination. The UPCSA is a reformed church and as such attaches great importance to theology, especially that which originates in the character and nature of God. It is therefore suggested that a contextual practical theology based upon the perfection of the grace of God may enable missional congregations to be developed, as they rediscover their identity in that grace. This then will be the basis for building congregations that are truly missional at heart and not just superficially so. The study will be contextualized to the South African scene and applied to local congregations in order to try to help them rediscover their true identify in Christ, and to provide a basis for understanding "missional" and thus what transformation may entail.

Key words: Missional; grace; identity; perfections of God; paradigm

1. Introduction

As a result of one of the decisions of the General Assembly, the decisionmaking body of the UPCSA (Uniting Presbyterian Church in Southern Africa), the General Secretary recently sent out an official letter stating that, "After a process of wide consultation with Presbyteries, congregations, Church Associations.... the 2012 General Assembly (decided that)... the overarching priority of the UPCSA is the supporting and development of missional congregations" (Pillay 2014:1, 4).

The central hypothesis of this article is that for this "overarching priority" to be in any way achieved, UPCSA local congregations must rediscover their identity in Christ, in the grace of God, since mission is an ontological attribute of the church. I would suggest therefore that it is only as congregations rediscover their identity in Christ through integrating an existential, heart-experience of God founded on a theology of grace, within a contextual, missional framework, and will truly missional congregations be formed. Thus, I consider how experiencing such grace, as a total dependence upon God, flowing through worship, relational discipleship, corporate missional prayer, and Trinitarian experience may lead a congregation to rediscovering this true missional identity.

2. What does contextual to South Africa mean?

A South African Practical Theological contextual study has to take account of three factors. These are, 1) the sheer ever enlarging predominance of the SAAD (South Africans of African Descent) population, 2) the progressive cultural Africanization of many South African churches and 3) the growing influence of Charismatic and Pentecostal worship, both in theology and praxis, in congregations of all cultures and races in South Africa. I support these assumptions in the next paragraph.

Statistics South Africa (2014:3,9) predicts that by 2040, 88% of the South African population will class themselves as "black", as compared to 80% in 2014. Secondly according to a CDE (The Centre for Development and Enterprise) 2008 report no.8, there has been an "explosive growth in Pentecostal churches in post-apartheid South Africa" (CDE 2008:5). The report comments that, "Most reasonably well-informed people are probably aware that there has been a dramatic growth in the number of people belonging to churches outside the mainstream Christian denominations such as the Anglican Church, the Roman Catholic Church, and the various long-established reformed churches inspired by Martin Luther and John Calvin" (ibid 6).

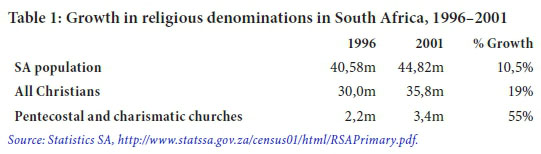

The CBD (2008: 25) report reproduces the table below:

It is concluded that in 2001, 12,5 million South Africans, around one third of all Christians were members of "Pentecostal" or "charismatic" non-mainstream churches, and their numbers are growing fast, while those of the mainstream churches remain static. Moreover the figures for the Pentecostal churches may still be underestimated because the 2001 census also records 3.2 million "other Christians", many who could be members of smaller Pentecostal community churches (ibid 5,15,16). If the rate of growth reflected in table 1 is sustained, then South African Pentecostals (excluding members of the Apostolic churches) will number almost 10 million by 2011, which is almost one fifth of the population (ibid 17). Whether this prediction was validated in 2011 is uncertain, at the moment. However, there is much anecdotal evidence to suggest that the growth trend of Pentecostal churches is continuing.

Thirdly, Schlemmer (2008:17) reports that the popularity of Charismatic and Pentecostal worship and praxis has also influenced many mainline congregations.

3. What is a missional congregation?

The "missional" idea is not a simple one to define and perhaps never will be; yet how we imagine it for ourselves is of vital importance. Various diverging ideas about what it means have emerged over the last fifteen years, since Guder published his seminal book, "Missional Church" (1998). I am unable, in this article to critique all these ideas, so I simply provide an overview to indicate the great divergence of meanings, and I direct the reader to Van Gelder & Zscheile's (2011:67f) book for further study. They categorize the various meanings of missional, using a study of the extant literature, under 4 headings; Discovering, Utilizing, Engaging and Extending (Van Gelder & Zscheile 2011:67ff). The authors suggest that in their opinion those in the first category of literature are "still discovering the meaning of missional" (ibid 71). Those in this category interpret being missional as primarily either what the church does out of obedience to the great commission, or as following Christ's example, or as incarnational ministry, or as the church as the location of God's ministry in the world (ibid 71,72). The second category of literature focuses around utilizing "God's agency, as the sending God, is the key to understanding the role of human agency" (ibid 75). The problem with this utilization of the concept, again in their opinion, is that tends to return to stressing human responsibility and not the grace or action of God. The third category of literature engages the missional concept in order to understand missional as some aspect of church life (ibid 84). This category tends to concentrate on the "how to", without much biblical or theological foundation (ibid 90). The fourth category seeks to extend the missional argument by underpinning it with a much deeper theological understanding and competent and thorough scholarly biblical exegesis, such as beginning with the Trinity or the kingdom of God and then expanding these concepts contextually (ibid 90ff), in which I would see myself.

I would concur with Niemandt (2010:1) who defines a missional church as, "a reproducing community created by the Spirit, who calls, gathers and sends the church into the world to participate in God's mission".

Yet because the term, "missional" can arguably be considered a metaphor (Guder 2000:54), it cannot be adequately described propositionally but only imagined. Following this line of thought I imperfectly imagine or picture a missional congregation as one,

in which the consensus1 of the worshipping community finds a heartfelt, affective identity in the grace of God, whom they passionately believe has sent His people, to be partners with him in his mission in the world. The Holy Spirit continually creates this consensus as the congregation responds to their experience of the triune God's grace, reign, redeeming work, presence, and love. It is actualized in praxis, by the congregation sharing the gospel of Jesus, being involved in the community, and being concerned for justice, in a contextual manner.

The key ideas I add are, "heartfelt", "affective", "identity", "passionately", and "grace". I add these ideas because in my opinion only a radical, inner, deep, miraculous transformation, by grace, of what the bible calls "heart"2will change a congregation so that it not just superficially missional, but affectively truly and deeply so. The mind needs to be impelled, as a gracious act of God, by the heart, for a person to fully embrace the missional concept. As Pascal (1671:100) commented, "Le coeur a ses raisons que la raison ne connait point" ("The heart has its reasons that reason does not know"). The impulse for true missionality flows from the heart and then motivates the mind. Thus a truly missional congregation's identity is found in their sense of "heart being" because they know the indwelling Christ by the power of the Holy Spirit, and by the amazing grace of God. Foremost in this is an awareness of being "in Christ", not just as a status, which is to be accepted intellectually and cognitively, but an identity which is experienced affectively as a daily reality.

Using this definition, the indications of a pilot scheme using the National Congregational Life Survey, administered by the author in 2015, to eight Johannesburg/Tshwane area congregations, are that are that most UPCSA will not be found to be missional at heart. The survey questions concerning the value placed on, firstly reaching those who do not attend church, and secondly on wider community care or social justice, revealed that only 7% and 9% respectively, of the 1200 worshippers surveyed, considered these aspects as an important core value. I interpret this to mean that their hearts have not been touched by God's grace in a way that passionately propelled them into the missio Dei.

4. Why identity?

As I have previously written (Tucker 2015:379ff) the existentialist philosopher Heidegger characterized the modern world as rooted in a "forgetfulness of being" (Manheim 1959: vii). This lack of reflection he calls "spiritual decline". But he saw an even greater problem than this. Thus he writes, "The spiritual decline of the earth is so far advanced that the nations are in danger of losing the last bit of spiritual energy that makes it possible to see decline" (Heidegger 1959:38). My contention is that this "forgetfulness of being" (as a synonym for "forgetfulness of identity") applies also to the UPCSA in South Africa today (and in many other main line churches) which means that they are either not missional, or see no need to be so.

As a result, I consider that rediscovering "being", which I equate with identity, is the first step to becoming a missional congregation. With this numerous ecclesiological scholars would agree, such as Van Gelder (2000), Hendriks (2004), Dick3 (2007:17), and Nel (2009). They may differ as to how this may be achieved but all concur with Zscheile (2012:1), "At the heart of the missional church conversation lies a challenge: to recover and deepen the church's Christian identity in a post-Christendom world..."

The question is, will rediscovering identity achieve this? The idea of identity, per se, has for long been an implied idea in Christian theology tradition. It can arguably be traced back to Augustine, Anselm (Bosch 1993:215f), Luther and then the Pietistic movement (Heitink 1999:29). Then in 1892, Deissman4 first connected the concept of identity with the "in Christ" formula that Paul used to describe a Christian's faith union with Christ. In contemporary language this may be described as a discovery that Paul found his identity "in Christ", thus highlighting the concept of "identity" for theology. Building upon this other scholars emphasized the collective emphasis of the formula and that it is practically equivalent to being in the church5. As Nel (2015:26) rightly comments it is possibly "the core metaphor" for the church's understanding of its own identity. It is interesting to note that Stewart (1935:viii) pointed out that this was an idea, "hammered out on the mission-field".

But is there a theological justification that will it lead to congregational transformation? It would seem so, because on numerous occasions Paul (Ladd 1974:524,525) appeals to the identity6 (Hawthorne & Wallis 2008: NIV heading, 1845-1853, 1802) of the Christian community, on several occasions, to encourage the congregations to which he wrote to live "missional" lives. I believe that Paul, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, would never have taken this approach unless it led to effective congregational transformation. We see this for instance in 2 Corinthians 5:17, which describes the identity of a Christian as a new creation7 and therefore as a result, "Believers (are to) embody the new creation of the new covenant by living for the sake of others" (Scott 2008, 2011: 2 Cor 5:17). The context of this scripture is that of the New Testament ministry of reconciliation (2 Cor 5:11-6:2). Thus Paul appeals to the "indicative" in Christ to make the imperative exhortation that the Corinthians strive to be missional, because that is the true reality about their identity. This illustrates the concept on which the transformative impact of the discovery of the missional identity is founded.

5. The implications of "missional" being a metaphor

The first implication of this is that because the church is described by many other metaphors and models, missional is only emphasizing one aspect of the reality of the multifaceted mystery of the church. It thus does not communicate the whole truth about the church (Dulles 1987:28). Thus, those who rightly desire to develop local missional congregations must be careful that this one aspect is not pursued alone or becomes the only integrating principle used for all the ministries.

Unless this caveat is heeded then the missional concept will become a paradigm (Dulles 1987:29). "Paradigm" theory is found in that broad branch of knowledge called "perception theory"8. Perception theories have entered theological discourse through the application of Kuhn's (1970) "paradigm theory" found in his "Structure of Scientific Revolutions". Theologians such as Küng (1988, 1989), Tracey (1989) and Moltmann (1989, 2010) have credibly applied this theory to theological discourse.

A paradigm in the theological sense is an unconscious, unquestioned way of perceiving reality, and more specifically what we consider to be right and wrong and/or the right way to do things and /or what is necessary to do and/or to be or not to be! The problem that this highlights with the "missional congregation" concept is that it could soon become the received wisdom, which must not be questioned. Thus the nature of the church is distorted and future creativity is dangerously curtailed.

6. The pre-eminence of grace in God's perfections

I consider that a congregation will only be able to develop towards becoming a missional congregation when its identity is found in the perfection of grace of God, since only then will it truly be reflecting the image of the God of all grace (1 Pet 5:10).

Barth's conceptualization of the God's being is the event and being of God in the person and work of Christ which reveals Him as "the One who loves in freedom" (Titus 2010:206). This is the "being" in Christ which the church needs to rediscover, because although God is differentiated from us, in him we find our being, as his creatures and his community of the church created in his image (Grenz 1994:179,180). How do we begin this rediscovery?

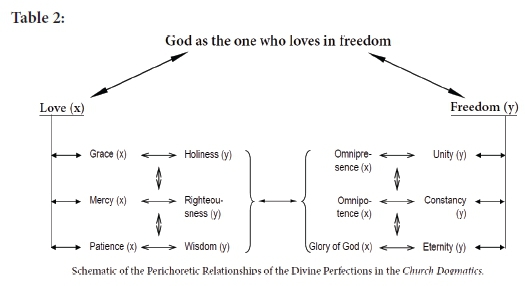

I suggest that Barth's (1957:322ff) schema of the perfections9 of God is the ideal starting point for this rediscovery of grace. As Holmes (2008:206) comments about it, "If the doctrine (of God) is to perform the salutary theological work for which it is capable, it would be to its advantage to describe as does Barth, God's attributes in terms of a series of short-hand descriptions which agree with God's enacted identity...". Titus (2010:212) represents Barth's schema of the perfections of God as the dyadic system presented below in table 2:

As will be obvious the schema, even in Barth's work, is an abbreviated attempt to somewhat apprehend an infinite mystery that cannot ever be fully comprehended. Yet the church and the world experiencing the perfections of God is contingent upon one primary perfection, and that is grace, which is the implication of what loving in freedom means (Titus 2010:213ff). God's freely loving and choosing the church is nothing else than an unconditional, sovereign act of continual grace mediated through the atonement. God's love overflowing into the church, through all his perfections, and through it to the world is by grace, and grace alone (Barth 1957 II/2:353).

Grace in all its actualizations is vast, yet I would presume to suggest that, although there may be many more actualizations, forming a missional congregation is fore mostly a work of God's grace as actualized in praxis by dependence upon God, worship, relational discipleship, corporate missional prayer and an experience of the trinity.

7. Grace - experienced in the heart as and by total dependence upon God

Grace is one of the foundational doctrines of the Reformed church (McGrath 1994:381 ff). It is an act of grace by which God, in love, freely chooses and calls out his people (Gen 12:1-3, Deut. 7:7-810, 1 Pet 2:9, 10) for their missional purpose in the world. The Christian life begins with this gift of grace (Eph 2:10, 11), and then "the entire living of the Christian life can be seen as the continual result from God's continual bestowal of grace" (Grudem 1994:200, 201). Thus Van Gelder (2000:146) can make the extremely pertinent observation that, "church life is grace-based." This suggests that it is the experience of God's grace, and the congregation finding its identity in that grace that forms the primary inspiration, inner impetus and empowering for being missional by freely revealing and communicating God's love and perfections to those who are in Christ.

Grace is more than a doctrine to be preached, an adornment of character, and more than an impersonal spiritual power or force. "Ultimately NT grace comes in a person, Jesus Christ, and is bound up with him (Jn 1:1-14, 16-17; Rom 5:21; 1 Cor 1:4)" (Kearsley 1988:280). It is more than an attitude or disposition. "In Paul ...χαρις is never merely an attitude or disposition of God (God's character as gracious); consistently it denotes something much more dynamic - the wholly generous act of God. Like "Spirit," with which it overlaps in meaning (cf., e.g., [Rom] 6:14 and Gal 5:18), it denotes effective divine power in the experience of men" (Dunn 1988:17). Unless grace is experienced as a experiential power as we relate to the risen Christ it is not the full, life changing grace that produces a missional congregation.

As Marais (1939/1960: 2:1351), a former Professor of Theology and the first chancellor of the newly designated Stellenbosch University, commented, "In the work of grace... the heart occupies a position almost unique." Grace must be heartfelt and flow into the heart to produce a missional congregation. Grace alone, by existentially revealing God's love to the undeserving, has the power to deeply influence the heart, mind, will and emotions to form a truly missional congregation for the glory of God. Why? Because grace comes to the creature, "as absolute miracle, and with absolute power and certainty. It can be recovered by the creature only where there is a recognition of utter weakness and unworthiness, an utter confidence in its might and dignity and an utter renunciation of wilful self-despair" (Barth 1957 II/2:19). Those who respond to God's grace have it written into their hearts and minds so that its effusive, sharing outgoing, generous character, reaches out to others to bless them, and becomes an overflowing outpouring from them, however unworthy they are. Thus an ecclesiology of grace must begin with heart's deeply touched by grace and not just with a cognitive understanding of its meaning, although this is also necessary, as Romans 12:2 indicates.

Those who have been truly touched by grace are totally dependent upon God because they realise that all local congregational transformation, development and effective activity is something that only God can do. Thus they desire to dependently wait on him in missional prayer (see below). As Psalm 127: 1-3 (NET version) reads,

If the LORD does not build a house, then those who build it work in vain. If the LORD does not guard a city, then the watchman stands guard in vain. It is vain for you to rise early, come home late, and work so hard for your food. Yes, he can provide for those whom he loves even when they sleep.

It is good that we want to develop missional congregations. Builders need to have the intention to build, vision, a plan and be prepared to work. Yet a congregation which tries to become missional but has not existentially experienced the transforming grace of God, may preach Jesus, effectively proselytize, even be involved in the community, but it will not be a truly missional congregation. It is not finding its identity in grace but in works! Without a heartfelt and conscious work of grace it is impossible for any congregation to cooperate and become fruitful in the missio Dei. As van Gelder (2000:19) comments, "Local congregations are complex creations of the Spirit..." They are beyond full human understanding; therefore any leadership or intervention must be originated, enlightened and empowered by his grace to achieve transformation in accordance with his purpose.

8. Worship

Miyamoto (2008:161) emphasizes the transforming power of worship in creating a missional congregation, "Worship occupies and must occupy the central place in Christian mission as well as mission theology." Worship exalts the "mighty triumphant grace of God in the atonement" (Barth IV/1:69). Thus it should be no surprise then that the public worship of the local congregation becomes the prime channel by which God's grace flows into the congregation touching their hearts and reinforcing their identity as his people who have been saved by grace. There is nothing more powerful, influential or corporately and individually transformative than a whole congregation being amazed and infilled by the grace of God as they worship.

Yet there usually needs to be a desire and expectation that God's grace will be poured out for this to happen, encouraged by worship that is contextual and exalts the Trinity. The hermeneutic foundation for this statement may be found in the people of God metaphor as reflected in the Exodus event. Here we see grace preceding worship (Deut 7:7-8). When Moses stands before Pharaoh and says, "Let my people go!" (Ex 5:1) he is referring to a group of people that have been chosen by the grace of God to be the unique grace-experiencing people of God. God is calling his chosen people out of Egypt to make covenant with them as they gather to experience and worship Him in joyful assembly on the mountain. It was as they go out and worship that they find their identity as his people and are consecrated by God to be a kingdom of missional priests who would be a channel of his grace to the nations (Ex 19:4-6). Brueggemann (1997:498) comments that this picks up the missiological blessing theme conferred on Abraham's descendants in Genesis 12:3.

This missiological purpose, conferred on Israel as they worshipped in assembly, is now extended to the New Testament church who are the new people of God (Romans 9:25, Galatians 1:13) (Clowney 1987:31; Dunn 1993:124,125), especially when they worship in assembly, as 1 Peter 2:4-5 indicates. Thus Guder (2000:154,154) can write, "Every time we gather for public worship... we are invited anew to God's (missional) call in Christ." Furthermore, as Israel's worship was in response to their experience of God's grace in delivering them from Egypt, so the church's worship is in response to God's grace in delivering Christians from sin and death. This is why in today's world the reformation of a congregation in rediscovering their identity as a missional people is directly informed by what happens in the worship service (Nel 2015:125).

It is often as we worship that God chooses to remove, by an act of pure grace, those things that prevent us from finding our identity in his grace and thus becoming missional, such legalism, emotional and social bondages, and evil spiritual powers. As we worship God speaks saying to everything that binds us, "Let my people go!" so that he might form a people who find their identity in his grace who overflow by being missional. This is often an inexplicable inner, hidden mysterious work of God deep within our hearts and minds, which may or may not manifest outwardly.

This is crucial because we are such foreigners to grace and so easily fall back into legalism, as did the Galatians that we need to be constantly reminded of it, experience it and be transformed by it through relating to God and others. The missional metaphor can be distorted into a new legalism that puts the congregation into bondage. Therefore being missional needs to be continually fuelled by the grace of God constantly experienced and repeatedly exalted in corporate worship. Thus in worship, "the continuing conversion of the church happens" (Guder 2000:159).

As the presence Jesus is experienced in worship with hearts overwhelmed by grace then he is able to deliver his people not from a physical bondage in Egypt, but from the emotional, social and spiritual bondages by which they have been enslaved in today's world. This is very necessary in today's world in South Africa and without the church cannot become missional. Many in this country are oppressed by fear, hatred and guilt. They have lost their identity as beings made in the image of God who have self-worth and hope. The history of God's people in South Africa has been framed by slavery to apartheid, institutionalized economic inequality11, prejudice and the struggle with all its evil collateral damage. AIDS, poverty, corruption, greed, immorality, entitlement, white guilt, political correctness, self-interest and the unhealthy aspects of urbanism, pluralism, and moral relativism. The future is, in addition, clouded by the prospect of joblessness, debt, economic and political insecurity, corruption, globalization, and environmental degradation.

At the same time in worship God is also given the opportunity to say. "Let my people go!" to the spiritual powers that enslave them, counter the grace of God and destroy a sense of identity as one of God's loved creatures and hinder them becoming missional. This would come within the category of what van Gelder (2000:135) calls a "power encounter" between God and the forces of evil. Many in the black African12 cultures have been taught to fear and respect the malevolence and unpredictability of the spirit world, often revealed in the entities they call "ancestors" (Taylor 2001:131; Nürnberger, K., 2007:45,209). These forces are perceived and experienced as spirit beings of power and authority (Hendriks 2004: 97). Worshippers are seeking to escape from a powerful all invasive spirit-world and so need to experience the signs and wonders that the Old Testament church saw in Egypt and experience in their pilgrimage. This often begins with meeting the living God, as mediated by the Word of God, in the redeeming person of the risen Lord Jesus Christ existentially through the power of the Holy Spirit in communal worship. As a result resisting demons and casting out demons in now a regular part of many church services in Africa (McCain 2000:112).

Such worship requires the gift of discernment on the part of congregational leaders. It may need a willingness to depart from being structured, although God's grace can flow through structure, to becoming unstructured spontaneous. It may involve the congregation ministering to each other, as in 1 Corinthians 12-14, through the manifestation of the grace gifts (χαρίσματα, "grace-gifts") that mysteriously, yet powerfully, connect us with the living God.

Yet a heartfelt response to the call is required, facilitated by those who direct worship and share the Word, reminding the congregation of their need of God's grace to stir up cold hearts in continual conversion, healing and deliverance from the powers of darkness both within and without. Time is also of the essence; it can happen within an hour but may require sacrificing much more time than this in waiting on God. It is also helpful if emotions are allowed to be stirred up by contextual worship which the congregation can identify as their "kind of music" in which they able to praise God freely.

"Music, singing and dancing reach deep into the innermost parts of African peoples, and many things come to the surface under musical inspiration, which otherwise might not be readily revealed" (Mbiti 1988:67). As in ancient Israel (see Ex 15:20, Ps 149etc.) black African worship is often joyous, boisterous, dancing worship and full of loud emotional praise. As Lebaka (2014:7) concludes from his study of ancient Israelite worship although, "music is often noted for its emotional affect... the use of music in praise also tends to focus attention away from oneself to the nature and acts of God, thus functioning to transport one's thoughts to another realm." It has precisely the same effect in black African churches where such worship seems to help the congregation break through to hope by realizing the presence of Christ and thus become an avenue for the experience of God's grace and of their true identity in Christ (McCain 2000:112,113), and that propels them into mission.

Whilst there are undoubtedly many culturally defined ways to worship God in spirit and in truth, it would seem that in Africa joyous, boisterous celebrations are going to prevail since the black African church is a church of young people (McCain 2000:108), in a continent where youth is demographically exploding in numbers. Moreover, "The entire African church is becoming much more African. The singing of Eurocentric hymns is being replaced by singing African choruses. Africans are expressing their worship of God in much more African ways. Churches . are much more open to physical and emotional expressions than a generation ago" (McCain 2000:112,113). I believe that those churches with European traditions will inevitably be increasingly influenced by this trend, as many have already been. Then, as this happens, congregations will increasingly find their identity in the grace of God and will become more contextually missional.

9. Relational discipleship

"Cheap grace is the deadly enemy of our church" (Bonhoeffer 1964:35). Bonhoeffer (1964:35ff) summarizes this as the preaching of forgiveness without requiring the transformation of the sinner. It must be admitted that this might be a charge that could be levelled against many in Africa. Thus Asamang (2016:1), a Ghanaian African, has recently written of the current, "moral recession in African Churches." There often seems to be a disconnect between the worship experience of many believers, particularly in Africa, and daily moral, attitudinal, and relational actions, goals, choices and motivational drives. Many appear to experience the reality of Jesus' presence but then, like the people of Israel, seem to forget about the command to, "be holy for I am holy" (McCain 2000:117).

Perhaps one reason for this is that grace is not linked with discovering their identity in the holiness of God for the worshippers? According to Barth (1957 II/1:353,396) divine grace is in tandem with holiness in his dyad because grace "stands directly confronted with and controlled and purified by the concept of divine holiness." By his grace, God does not leave us in the sinful state in which he called us but wants to change us. The God of grace is one of constant newness, innovation and transformation. He is a dynamic being that is event, becoming and motion (Leupp 2008:39, 41), ever the God of the novum.

Holiness is produced in true worshippers because God "distinguishes and maintains his own will against every other will. He condemns, excludes and annihilates all contradiction and resistance to it" (Barth 1957 II/1:359). It involves both pain and joy because it, paradoxically, produces a growing reverence and awe of the Godhead but which at the same time is accompanied by blessing, help, and restoration (Barth 1936 I/1:370, 1957 II/1:361). As a result those who enjoy fellowship with the Trinity have been summoned to a dynamic transforming friendship with God that leads to an ever greater sharing in the triune life (Leupp 2008:103), and a perfecting of the divine image within them and increasing awareness of their identity in Christ.

Although it happens as matter of course in both the unwilling and willing Christian, yet God prefers it to be intentional and a journey with others who are also in the Body of Christ. When that is so, it is sometimes called "spiritual formation" or "discipleship". Spiritual formation and/or discipleship can be defined as "our continuing intentional response to the process of God's grace shaping us into the likeness or image of Jesus Christ (as defined by Trinitarian relationships), through the work of the Holy Spirit, in the community of faith for the sake of the world" (Doornenbal 2012:211: Osmer 2012:7). I would add that discipleship/spiritual formation may also be seen as a journey towards discovering a Christian's identity in God's perfection of holiness because he/she is ontologically in Christ. Thus as Light (2012:177) comments, "...the importance of discipleship from the beginning is vital if the full moral strength of Christianity is to be witnessed in Africa."

Since grace overflows in relationships (1 Peter 4:10), a "being" church is one where all share in being on the discipleship journey to discovering their true identity As we live with others we learn and change others by example and being an example, rebuke and rebuking, being helped and helping, teaching and being taught, being comforted and comforting, being encouraged and encouraging. It is not just a matter of being in a small group once a week and a worship service on a Sunday but of being informally in constant caring, contact with individuals and households in the congregation. This is a very contextually relevant idea in South Africa. The idea of community is, perhaps, the most prominent characteristic of black African culture and religion and has seemingly been so from the depths of time. Individuals gain their sense of identity from belonging to a community of persons, as emphasized by the Zulu saying, "umunti ngumuntu ngabantu" (a person is a person through other persons).

10. Corporate missional prayer

Zscheile (2007:59) comments that, "the Spirit decisively shapes and reshapes the Christian community's imagination for its identity, purpose, and calling through a dynamic process (which)... must be constantly discerned under the prayerful direction of the Spirit." I would add that those who are finding their identity in the grace of God are not only continually seeking the prayerful direction of the Spirit, but as a missional community are also desperately dependent on prayer. Without the practice of corporate prayer the congregation will never existentially experience their identity in the grace of God, and thus they will not become truly missional. Yes, prayers are beneficially offered in the worship service but the bible has examples of many times of protracted corporate praying, where praying together is the main component (such as Acts 1:14; 2:42; 6:4; 12:5; 13:3; 20:36 etc).

Yet an idea of the impoverished state of corporate prayer in some mainline churches is beginning to be discovered, although much more research needs to be done. The Congregational Life Survey in 2006 survey discovered only 7% of those in the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa, saw prayer as one of the top three values in their congregation (Schoeman 2010:118). If these figures are representative of all main line denominations (which there is good reason to believe that they are) then the contemporary empirical church is falling far short of the praxis of the church as defined and portrayed in the New Testament. This is not a recent development. As far back as 1912 Andrew Murray, along with 200 other ministers, reflecting on the lack of conversions, declining membership and lack of spiritual vitality of the church in South Africa attributed it to "the sin of prayerlessness" (Choy 1983:7-9). Perhaps, still today, church leaders in many congregations will confirm this from their own experience.

On the other hand for many congregations, where a non-European culture is in the majority, corporate prayer is regularly practiced with participation by many of the church members Their praying may be described as showing freedom, commitment, zeal and fervency, much as it is modelled in Acts 4:23-30. As Sundkler (1961:185,193) records of a Christian Zion Sabbath Apostolic Church prayer meeting in Kwa-Zulu Natal, "All kneel in prayer. After a few seconds the room... is filled with the most astounding volume of sound. All are praying at the same time." Although this is a record of a prayer meeting in the 1950s it is still typical of most African Initiated Churches and many main line churches who have a predominantly black membership. I have been a participant in several such prayer meetings in a mainly black African congregation in Clarens since 2014. Perhaps we should not be surprised that this is an actively growing congregation, with many new converts, that has planted out several other churches in South Africa and Lesotho! Perhaps remarkably, it is linked with a reformed church movement that is planting churches in Europe, India, Pakistan, Philippines and Malaysia.

When strong leadership is exercised using an "African" or "newer church" style of prayer and the praying is sensitively guided with prepared topics, allowing deviations as the Spirit leads, it can for most of the meeting be kingdom directed, and thus missional. A strong leadership can thus use such meetings to share the vision God has given to the congregation and what is needed to implement it. Surely this is a much better way of communicating vision and motivating its enactment than just with a lecture, planning session or discussion (although these processes are necessary and useful if they are seen as only a minor part of actualizing vision).

There are numerous other advantages to such prayer meetings. They allow God to speak to the participants through the gifts of the Spirit, as may have happened in Acts 13:1-3. They encourage a sense that, because all may and do participate, that the prayers of all contribute to God responding, and are thus responsible for whatever blessings result and the work of grace that may lead to the achievement of the vision. It must be admitted that it is easy to pretend deep emotion in such a situation to impress others or to believe that it is the emotion that causes the prayer to be effective, and this is undoubtedly the case for some. Yet for those who are "being" in Christ as disciples praying all at the same time arouses passion, fervency, pleading, faith and thus a resultant deep commitment to the vision.

As I have stated there are many models for prayer in the bible. The model I am suggesting is probably more a "crisis" model (see the crisis in Acts 4:23-31). Yet it may be more contextual in our postmodern society than any other model since the church is continually in crisis. As a result miraculous acts have become perceived by many as the most persuasive way of authenticating the reality of the living God. Whilst this has its dangers, if handled correctly in a discipleship atmosphere, it is surely an appropriate re-emergence of the emotions, fervency and dependency upon God's grace found in many prayers recorded in both the Old and New Testaments that will bring the "being" church increasingly into existence in all its missional dimensions in the South African context. Let us heed Barth's (1956 IV/1:711) warning concerning prayer, "As the true Church it would always die and perish... if it did no hear His voice, summoning it to watch and pray: to watch over its being in all its dimensions..." (My italics).

11. A Trinitarian experience of God

How are all these things to happen? Becoming a "being" church that is truly missional, as described above, perhaps seems, and probably is, an impossible ideal. It needs something supernatural happening in the hearts and minds of God' people at a corporate and individual level. A reading of the Old and New Testaments would seem to indicate that what is needed is the full Trinitarian experience of God as God the Father, Christ the Son and the Holy Spirit in the local congregation. Perhaps this full experience does not seem to occur very frequently because of the neglect of the person of the Spirit upon which the very life of the church depends (Marshall 2013:12). It is through the Holy Spirit that Christians primarily experience Christ and, through him, God the Father (Calvin Institutes III, ch.1, 1). Neglect of the role of the Spirit in divine sending contributes to an overly functional, mechanistic, less organic view of the church and its mission (van Gelder & Zscheile 2011: xvii). Becoming missional can only be accomplished by the sovereign grace of God through the ministry of the Holy Spirit ministering the grace of God. As Niemandt (2012:2) comments, "Mission begins in the heart of the Triune God and the love that binds together the Holy Trinity, overflows to all humanity and creation..."

Yahweh promises in Zechariah 12:10, "... I will pour out on the house of David and the inhabitants of Jerusalem the Spirit13 of grace and supplication." The Hebrew text reveals that in Zechariah 12:10 Yahweh is promising that the society of Judah will have poured upon it, "the ruah of ḥēn and taḥănûnı̂m." I prefer the interpretation of ruah as "Spirit" to "spirit", since the "pouring out" of the spirit elsewhere in the OT always indicates the pouring out of God's Spirit, as in earlier passages such as Isa 44:3; Ezek 39:29; Joel 2:28-3:1 (Duguid 2008: loc.228917-229871). The Spirit of grace, then, is the Spirit that YHWH pours out upon His people though they little deserve it (Merrill 2003:308). Both ḥēn and taḥănûnı̂m are derived from the same root, ḥānan, which means "grace" and "pleadings for grace". This implies that the former must be imparted before the latter occurs (Leupold 1956:236). Thus the author may be suggesting that the grace of God motivates those upon whom the Spirit is poured to seek his grace through prayers. YHWH thus extends His grace to enable His people to seek it. Without the Spirit having moved them, they would never have sought the face of YHWH in prayer (Merrill 2003: 308).

Thus in conjunction with Ezekiel 37:29 this pericope suggests that this outpouring will affect a permanent inward change and be transformative, and implant God's spirit, God's heart and desires into those upon whom the Spirit is poured. This resultant complete change of heart is in fact a conversion experience, either the initial experience of regeneration or of the continuing conversion a recalcitrant people of God always seem to need.

How does this apply to today's church? The author of John's gospel sees this promise as fulfilled in the person of Jesus when he was crucified (Smith 1984:277,278). Although not all commentators agree, it can legitimately be taken as a Messianic promise, as it was interpreted in early Jewish tradition and in NT Christology. The whole pericope may thus be seen as indicating how the Spirit is an instrument of the continuous grace of God in the church age for regeneration and continuous conversion both for the Old Israel and for the New Israel, which is today's church.

My contention is that only the frequently experienced fulfilment of the promise of Ezek 36:26, 2714 will produce a missional church. Only God's Spirit is able to implant a missional DNA into a believer or a congregation. Only his Spirit is able to give the desire and empowerment for imperative to become indicative. Only his Spirit will enable a rediscovery of "being" a new creation in Christ Jesus. No amount of teaching, equipping, conferences, latest fashions, persuasion, or modelling, and even prayer can achieve this. It is noteworthy that Exodus 35:21; Haggai 1:1 and Ezra 1:1,5 all make a connection between the action of man's spirit being stirred up by God and the mobilization of people who willingly want to build up the tabernacle or the temple (Welker 1994:102ff). It is not just renewal or reformation that is needed but something similar to reconversion so that we exchange driven, performance based "doing" for compelling, passionate "being" out of which God pleasing, grace-filled, transformative doing wells up because we have rediscovered our true identity.

12. Conclusion, using the insight provided by paradigm theory

If the above is true, then the process of many congregations becoming truly missional will usually need a paradigm shift. Paradigm shifts, which are the shorthand for moving from being influenced by one paradigm to being influenced by another, are not easy. When paradigms change many people often find themselves confused, insecure and at a loss to understand the new paradigm. They interpret teaching about the new paradigm either in terms of the old (hearing but not hearing!) or else intuitively oppose it (Dulles 1987:31,32). Moving from one paradigm to another requires a new understanding of reality and undercuts what is automatically considered culturally and naturally right. This means that proponents of the old paradigm just cannot understand the arguments of those who advocate the new.

In fact the shift from one to the other is so difficult and intuitive that Kuhn even uses the term "conversion" to describe the change from the mind-set of one paradigm to that of another (Kuhn 1970:151). The basis for this to happen in local congregations will certainly be the teaching and preaching of the Word of God and an acceptance of its authority in all areas of faith and conduct. Yet I believe it will only happen if that teaching and preaching emphasizes a prayerful seeking and a profoundly theological, miraculous, Spirit wrought, grace dependence, life transforming "continuing conversion of the church" in the hearts of his people as we worship and intimately relate to each other in our journey together. Only then will we begin, by God's grace, to become truly missional in praxis, because it is already the church's identity in Christ.

Bibliography

Asamang, A., 2016, Moral Formation of Christian Leaders in Africa: Lessons from the Literature and the Pastoral Epistles, lecture notes, SATS Academic Retreat, 21/22 April 2016.

Barth, Karl, 1936, Church Dogmatics, 1/1, The Doctrine of the Word of God, T & T Clark, Edinburgh.

Barth, Karl, 1956, Church Dogmatics, IV/1, The Doctrine of Reconciliation, T & T Clark, Edinburgh.

Barth, Karl; 1957, Church Dogmatics, II/2, The Doctrine of God, T & T Clark, Edinburgh.

Bosch, D., 1991, Transforming Mission, Orbis Books, New York.

Bonhoeffer, D., 1963, The Cost of Discipleship, New York, Macmillan.

Brueggemann, W., 1997, Theology of the Old Testament, Fortress Press, Minneapolis.

Calvin, J., 1970, Institutes, MacDonald Publishing Company, Florida.

CDE, 2008, Under the Radar, Informing South African Policy Pentecostalism in South Africa and its potential social and economic role, CDE In Depth no 8, Centre for Development and Enterprise, Johannesburg.

Choy, L., 1983, Preface in State of the Church, Murray (author), Christian Literature Crusade, Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, 7-10.

Clowney, E., 1987, The Biblical Theology of the Church, in Carson D. (ed.) The Church in the Bible and the World, The Paternoster Press, Exeter, 13 - 87.

Dames, G., 2010, The dilemma of traditional and 21st Century pastoral ministry: Ministering to families and communities faced with socio-economic pathologies, HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies, 66(2). [Online]. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v66i2.8. [Accessed 22 June 2014). [ Links ]

Dick, D.R., 2007, Vital signs: A pathway to congregational wholeness, Discipleship Resources, Nashville.

Doornenbal, R. (2012) Crossroads: An Exploration of the Emerging Missional Conversation with a Special Focus on 'Missional Leadership and its Challenge for Theological Education, Eburon Academic Publisher, Delft.

Duguid, I., 2008, Zechariah, in Lane D., Grudem W., Collins C., (eds.), ESV Study Bible, Kindle Version, loc 228917 - 229871, (Study notes loc 230693 - 231711), Crossway, Wheaton. [ Links ]

Dulles, A., 1987, Models of the Church, Doubleday, New York.

Dunn, J., 1988, Romans 1-8, Word Biblical Commentary, Volume 38A, R. Martin (ed.), Word Books, Dallas, Texas.

Dunn, J., 1993, The Theology of Paul's Letter to the Galatians, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Grenz, S., 1994, Theology for the Community of God, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, Cambridge, U.K.

Grudem, W., 1994, Systematic Theology, Inter-Varsity Press, Leicester.

Guder, D., 1998, Missional Church: A Vision for the Sending of the Church in North America, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Guder, D., 2000, The Continuing Conversion of the Church, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Heidegger, M., 1959, An Introduction to Metaphysics, Yale University Press Inc., New Haven.

Hawthorne, G., & Wallis, W., 2008, Colossians, NIV heading, 1845- 1853, 1802.

Heitink, G., 1999, Practical Theology. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., (translation of Praktische Theologie, Kok-Kampen, 1993). [ Links ]

Hendriks, J., 2004, Studying Congregations in Africa, Lux Verbi BM, Wellington, South Africa.

Holmes, C., 2008, The theological function of the doctrine of the divine attributes and the divine glory, with special reference to Karl Barth and his reading of the Protestant Orthodox, Scottish Journal of Theology Ltd, 61(2), 206-223. [ Links ]

Hunsinger, G., 2000, Disruptive Grace, Studies in the Theology of Karl Barth, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Kearsley, R., 1988, Grace, in B. Ferguson (ed.), New Dictionary of Theology, Inter-Varsity Press, Leicester.

Kittel, G., & Gerhard F., 1985, kardía/καρδία [heart], Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, Abridged in One Volume, the Word 2010 version, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Kuhn, T., 1970, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Chicago, University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Küng, H., 1988, Theology for the Third Millennium, (Trans Heinegg P.), Doubleday, New York. [ Links ]

Küng, 1989, Paradigm change in theology: A proposal for discussion, in D. Tracey & H. Küng (eds.) Paradigm Change in Theology, Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark Ltd., 3-33. [ Links ]

Ladd, G., 1974, A Theology of the New Testament, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Lebaka, M.E.K., 2014, Music, singing and dancing in relation to the use of the harp and the ram's horn or shofar in the Bible: What do we know about this?, HTS Teologiese Studies/ Theological Studies 70(3), Art. #2664, 7 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v70i3.2664 [ Links ]

Leupold, H., 1956, Exposition of Zechariah, Baker Book House, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Leupp, R., 2008, The Renewal of Trinitarian Theology, IVP Academic, Downer's Grove, Illinois.

Light, V., 2012, Transforming the Church in Africa, South African Theological Seminary Press, AuthorHouse, Bloomington, Indiana.

Manheim, R., Translators note, in Heidegger, M., 1959, An Introduction to Metaphysics, Yale University Press, New Haven, vii-x.

Marais, J., 1939, 1960, The International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia, E. Orr (ed.), Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids.

Marshall, G., 2013, A Missional Ecclesiology for the 21st Century, Journal of European Baptist Studies, 13 (2), 5-21. [ Links ]

Mbiti, J., 1989, African Religions and Philosophy, 2nd Ed, Heinemann Publishers, Oxford.

McCain, D., 2000, The Church in Africa In the Twenty First Century: Characteristics, Challenges and Opportunities, Africa Journal of Evangelical Theology, 19 (2), 105- 130. [ Links ]

McGrath, A., 1994, Christian Theology: An Introduction, Blackwell Publishers, Oxford, UK.

Merrill, E., 2003, An Exegetical Commentary Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi, Biblical Studies Press, L.L.C, www.bible.org, viewed 1 June 2011.

Miyamoto, K., 2008, Worship is nothing but mission: A reflection on some Japanese experiences, in A. Walls & C. Ross (eds.) Mission in the 21st century: Exploring the five marks of global mission, Darton, Longman and Todd, London, 157-164. [ Links ]

Moltmann, J., 1989, Theology in transition - to what?, in Moltmann J. & Tracey D. (eds.), Paradigm change in theology, Edinburgh: T&T Clark Ltd, 220-225. [ Links ]

Moltmann, J., 2010, Sun of Righteousness, Arise! God's future for Humanity and the Earth, Fortress Press, Minneapolis.

Nel, M., 2009, Congregational analysis revisited: Empirical approaches, HTS Teologiese/'Theological Studies 65(1), Art. #187, 13 pages. DOI: 10.4102/hts.mv65i1.187 [ Links ]

Nel, M., 2015, Identity-Driven Churches, Biblecor, Wellington, SA.

Niemandt, C., 2010, Acts for today's missional church, HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 66(1), Art. #336, 8 pages. DOI: 10.4102/hts.v66i1.336 [ Links ]

Niemandt, C.J.P., 2012, Trends in missional ecclesiology, HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 68(1), Art. #1198, 9 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v68i1.1198 [ Links ]

Nürnberger, K., 2007, The living dead and the living God, Cluster Publications, Pietermaritzburg.

Osmer, R. (2012) Formation of the missional church: Building deep connections between ministries of upbuilding and sending, in D. Zscheile (ed.), Cultivating sent communities: Missional spiritual formation, Wm B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI, 29-55.

Pascal, B., 1671, Pensees, sur la religion et sur quelques autres sujets, Troisième edition. Ä Paris. Ebook par Samizdat 2010 [Online]. Available: http://www.samizdat.qc.ca/arts/lit/Pascal/Pensees_1671_ancien.pdf. [Accessed 21 July, 2014.)

Pillay, J., 2014, Reflections on the biblical and theological background to the Vision and Mission Priorities of the UPCSA, On Behalf of the General Assembly Priorities and Resources Committee.

Schlemmer, L., 2008, Dormant Capital. The Pentecostal movement in South Africa and its potential social and economic role, Centre for Development and Enterprise, Johannesburg.

Schoeman, W. (2010) The Congregational Life Survey in the Dutch Reformed Church: Identifying strong and weak connections. Nederduitse Gereformeerde Teologiese Tydskrif, 51 (3 & 4): 114 - 124. [ Links ]

Scott, J., 2008, 2011, 2 Corinthians, NT ed. Thomas R. Schreiner, ESV Study Bible, Crossway, Wheaton, Illinois, viewed at www.crossway.org, 29 August 2014, note on 2 Cor 5:17.

Searle, J., 1992, The Rediscovery of the Mind, MIT Press, London, England.

Smith, R., 1984, Micah to Malachi, in Hubbard D., Baker, G., (eds.), Word Biblical Commentary, Word Books, Waco, Texas, 165-293.

Statistics South Africa, 2014, National and provincial labour market: Youth, Statistical release P0211.4.2, [Online]. Available: http://beta2.statssa.gov.za/publications/P02114.2/P02114.22014.pdf. [Accessed 15 July, 2015.)

Stewart, J., 1935, A Man in Christ, Hodder and Stoughton Limited, London.

Sundkler, B., 1961, Bantu Prophets in South Africa, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, London.

Titus, E. J., 2010, The Perfections of God in the Theology of Karl Barth, KAIROS - Evangelical Journal of Theology, Vol. IV. No. 2 (2010), 203222. [ Links ]

Taylor, J., 2001, Christian presence amid African religion, Action Publishers, Nairobi.

Tracy, D., 1989, Paradigm change in theology, in H. Küng & D. Tracey (eds.), Hermeneutical Reflections in the new paradigm, T&T Clark Ltd, Edinburgh, 34-62.

Tucker, A., 2015, Discovering the Church's forgotten identity - a key to developing missional congregations, in Nel, M., Identity-Driven Churches, Biblecor, Wellington, SA, 372-384.

Van Gelder C., 2000, The Essence of the Church, Baker Books, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Van Gelder, C. & Zscheile D., 2011, The Missional Church in Perspective, Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids. Michigan.

Welker, M., 1994, God the Spirit, Fortress Press, Minneapolis.

Zscheile, D., 2007, The trinity, leadership, and power, Journal of Religious Leadership, Vol. 6, No. 2, Fall 2007, 43-63. [ Links ]

Zscheile, D., 2012, Cultivating sent communities: Missional spiritual formation. Zscheile (ed.) Wm B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI, 1-28.

1 It might be possible to assess this consensus through using the National congregational Life Survey.

2 I use the word "heart" in the New Testament sense as the seat of feelings, desires, and passions (e.g., joy, pain, love, desire, and lust; cf. Acts 2:26; Jn. 16:6; 2 Cor. 7:3; Rom. 10:1; 1:24) (Kittel & Gerhard,1985, kardía/καρδία [heart]).

3 Dick does not use the word, "missional" as such, but it is obvious that his term, "vital" includes the idea of being missional (Dick 2007: 93).

4 Deissmann, Die neutestamentliche Formel, "in Christo", quoted in Stewart, p 155f.

5 See Dodd, C., 1932, Romans, p 87ff, quoted in Ladd, 1974, A Theology of the New Testament, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, MI.

6 See also Bosch, D., 1991, 143, 394, 426. (See for instance Romans 6: 1-14, 12: 1-15, 2 Cor 6:12-20, Phil 2: 12-13, Gal 5:25, Col 3:1-10).

7 See in particular Barth's numerous exegeses of 2 Co 5:17, in Barth, Karl; 1956, Church Dogmatics. Volume 4.1, The Doctrine of Reconciliation. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, p 49, 73, 256, 295, 321, 749.

8 One of the ideas of perception theory is that errors often occur between what we actually see and what we think we see. These errors are usually produced by "misplaced assumptions or knowledge" (Gregory, R., 1981, Mind in Science, London, Weidenfield and Nicholson, 395). This category of error occurs because our normal perceptions are always structured. We read patterns and meaning into the text depending on what we want to see or have been taught to see so that we can easily assimilate knowledge (Searle, J.,1992, The Rediscovery of the Mind. London. England: MIT Press, 133ff.).

9 "Perfections" (Vollkommenheiten) is the term Barth prefers to use when speaking of God's attributes (for more see, Barth 1957 II/2:322ff, Titus 2010:203, Hunsinger 2000: 193,194).

10 Deuteronomy 7:7-8 (NIV2). The LORD did not set his affection on you and choose you because you were more numerous than other peoples, for you were the fewest of all peoples. But it was because the LORD loved you and kept the oath he swore to your ancestors that he brought you out with a mighty hand and redeemed you from the land of slavery, from the power of Pharaoh King of Egypt.

11 For further insights I recommend, Dames, G 2010.

12 I apologize if this description is rather inaccurate and may offend some, but I cannot see any plausible alternative description.

13 Alternative reading in NIV footnote.

14 "I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit in you; I will remove from you your heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh. And I will put my Spirit in you and move you to follow my decrees and be careful to keep my laws."