Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

On-line version ISSN 2413-9467

Print version ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.2 n.2 Stellenbosch 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2016.v2n2.a07

ARTIKELS

Accessing Yahweh's presence: Ethical implications of the entrance liturgy of Psalm 15

Boloje Blessing OnoriodeI, 1; Groenewald AlphonsoII

IUniversity of Pretoria pstbobson@yahoo.co.uk

IIUniversity of Pretoria alphonso.groenewald@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article is an examination of the theological foundation that lies at the core of the expression of Israelite piety; that is, the foundational and defining characteristic reflexes in Israelite religious experience of human access to Yahweh. The article is rightfully anchored on the premise that individuals and communities have the privilege of access to Yahweh. However, Psalm 15 presents certain ethical preconditions of continuous experience of access and intimacy with Yahweh. These ethical preconditions constitute Israel's practice of pilgrimage with Yahweh, a practice that witness to the passionately penetrating symbolism of the requirements of a consistency of life direction. Psalm 15 insists that those who approach Yahweh for divine help or worship may do so having their internal and external condition in harmony with Yahweh. They must do so from hearts and lives of integrity. This article thus focuses on the context, content and concludes by reflecting on the ethical implications of Psalm 15 for both individual and corporate experience of worship.

Keywords: Entrance liturgy; prayer; ethics; Psalm 15; Yahweh's presence; worship

1. Introduction

A biblical theology of access to Yahweh's presence focuses attention on human speech that Israelite community expressed to God. This dynamic modality of divine-human interchange (Balentine 1993:38f) is observed in the form of petitions, requests, dialogues, questioning, praise and thanksgiving that Israel offers to God. Thus in several texts arising out of a myriad of diverse situations, the Old Testament (OT) portrays God as deciding to make himself accessible to humanity through hearing human speech (Kessler 2013:383). With this medium of speech, Israel as well as non-Israelites could enter into the presence of God and express their life experiences to Yahweh. These speeches (requests, petitions, dialogues, questioning, praise and thanksgiving) were mostly rendered in poetry as could be seen in the psalms. Yahweh remained open to human interaction and was willing to receive the prayers of Israel. While the act of prayer lies at the heart of the theology of access to Yahweh's presence, the primary relational response in this stream of tradition is rooted in the human neediness and dependence upon Yahweh.

Fundamental to the theology of access to Yahweh's presence is the underlying assumption that, to address Yahweh, "one must first enter into the presence of God" (Kessler 2013:385). Yahweh's manifest presence is documented and experienced in the OT. In the OT "Yahweh's presence" expressed with the Hebrew  (literally translated "face") is generally given a spatial connotation (Murphy 2000:38-40). In this regard, one can

(literally translated "face") is generally given a spatial connotation (Murphy 2000:38-40). In this regard, one can  "come into, enter" (Ps 66:13; cf. Ex 22:9) or

"come into, enter" (Ps 66:13; cf. Ex 22:9) or  "draw near to, approach" (cf. Lev 9:5; Ezek 44:15; Ps 119:169) Yahweh's presence. On the other hand, one may seek to flee from it (Jonah 1:10) or reside far from it (Gen 4:16). Yahweh's presence is however limitless and unavoidable (Ps 139:7-12; cf. Jonah 1:10).

"draw near to, approach" (cf. Lev 9:5; Ezek 44:15; Ps 119:169) Yahweh's presence. On the other hand, one may seek to flee from it (Jonah 1:10) or reside far from it (Gen 4:16). Yahweh's presence is however limitless and unavoidable (Ps 139:7-12; cf. Jonah 1:10).

Although the OT contains a rich and diverse vocabulary and theme of Yahweh's presence (Berkovic 2009:51-72),2 the ability of an individual or group to enter into Yahweh's presence, and various forms of speech for accessing Yahweh's presence (Miller 1994:46-49), the primary concern of this article is to examine such necessary preconditions of access to Yahweh's presence. This investigation of access to Yahweh's presence is undertaken through the textual window of Psalm 15. In spite of the fact that individuals in the psalms could affirm their being in Yahweh's presence continually, the great privilege of speaking to Yahweh is indicated by a sense of awe and approach to the divine in various ways (Kessler 2013:398). This is especially evident in the text of Psalm 15 that stresses that access to Yahweh requires certain moral and character attributes or qualifications.

The article focuses more on the synchronic dimensions of psalm 15, and less on the diachronic perspectives. The literary analysis though combined with a historical embeddedness of the psalm, does not postulate a reconstruction of the cultic context of the psalm or re-categorize the psalm. The article is undertaken simply to articulate the psalm's divine and didactic qualities, which are singled out for emulation. It holds that there is a vital connection between Yahweh's worship (cult) and the way individuals relate with one another in a covenant community (ethics) (Maloney 2003:157). These connections which are ethical in nature constitute Israel's practice of pilgrimage with Yahweh, a practice that witness to the passionately penetrating symbolism of the requirements of a consistency of life direction. In the following sections, the article gives attention to the context and content of the Psalm 15, and then reflects on the ethical implications of Psalm 15 for both individual and corporate experience of worship.

2. Context and content of Psalm 15

The significance of the psalms in the worship and life of both Jewish and Christian tradition is beyond dispute. While it is not possible to define Jewish and Christian approaches to psalms in general, on account of the broad diversity of ways that both religious traditions have practiced biblical scholarship, biblical research on psalms is an area of Jewish and Christian cooperation (Grohmann & Zakovitch 2009:7). The Psalter3 has had an all-embarrassing presence in the synagogue and the Christian church. Such an enduring and widespread power of survival may be claimed for no other book of poetry and song (Terrien 1952:vii; Weiser 1962:21). Sals (2009:96) aptly notes, "Indeed, no other book seems to be read so decisively as Jewish by Jews and Christian by Christian." Its position in the Hebrew canon however, presents a perplexing picture in the various areas of text tradition (Kraus 1993:12). Quotations from the Psalms are numerous in the New Testament (see Mark 12:32-37; Acts 1:16; 2:25-28; Romans 11:910; Hebrews 2:12; 3:7; 4:7; 10:5), and they have influenced the liturgies of all branches of Christianity (Blaising 2012:51f). Perowne (1976:40), a Christian commentator declared, "The history of the Psalms is the history of the church, and the history of every heart in which has burned the love of God." Life's varied melodies are all presented in the psalms. This humanness, honesty and faith have touched responsive chords in countless lives (Wood 1984:3; Witvliet 2012:7).

Each psalm was composed within what is called a "life setting" or "cultural context." The context could be social, political, geographical, or provincial (Kafang 2002:25). Considering the vital elements, which prepared the origin of the Psalter and oriented its distinctive development, Terrien (1952:19-32) analysed the dominant motifs under deliverance, warfare, and the cultic presence of God, thanksgiving for harvest, holy history and personal communion with the divine. Psalm 15 is believed to have been compiled autonomously for usage in a particular cultic situation. According to Gunkel (1998:72),

Psalm 15 most clearly presupposes a specific worship service. The priest communicates an answer for the laity to the question of their condition if they wish entry onto the holy mountain. However, the text does not offer a single word regarding which festival would have included this kind of question and answer.

This observation is however contrary to Mowinckel's (1962:1-41) position who built upon the foundations of Gunkel. Mowinckel's rigorous and extensive pursuit led him to conclude that the psalms are totally cultic both in origin and intention. In his cult-historical methodology, he argues strongly that every psalm in the Psalter has a cultic origin and it is this cultic origin of the psalms that must provide the framework for the interpretation of each of the psalms. He contends that Psalm 15 is associated with the annual festival of Yahweh's enthronement that served as the original context of the classical enthronement psalms celebrating Yahweh's kingship (Clifford 2014:333).

Although, the concept of access to the deity involving prayer and praise has been observed as a stock constituent of ancient Near Eastern context, that is Israel's neighbours' religions (Westermann 1981:36-43; Buccellati 2000:1685), there is however, no clear portrayal of the worship records of the temple in Israel (Clements 1999:83). Israel's three great annual festivals4were celebrated at the sanctuary on Mount Zion, and as 1 Kings 9:25 shows, their major feature was the great offering of sacrifices. The psalms were said to be suited to the above hypothetical festivals or to the biblical festivals. However, the evidence from the OT itself for such festivals is deficient (Collins 2012:23). A trace of all this can hardly be found in the psalms with the exception of Psalm 81:3-4. The titles of the psalms provide no adequate and authentic information. This indicates how little interest the psalmists took in all the calendars, dates, seasons, and even the rituals (Kraus 1992:85).

The psalm is arranged as part of the larger literary and compositional unit of Psalms 15-24 (Groenewald 2009:428), with Psalms 15 and 24 frequently described by scholars as "entrance liturgies" (Westermann 1980:103; Day 1999:60; Vos 2004:253; Broyles 2005:248ff; Hunter 2007:187ff; Sumpter 2013:186). These psalms (15 and 24) probably circulated along with similar temple liturgical psalms like 18, 48, 65, and 87 and may have been recited by worshippers coming to the Jerusalem temple in question-and-answer dialogue with attending priests and Levites who guarded the point of access to it (Kessler 2013:399). The theology of the temple as it well in Jerusalem was closely linked with the ideas of moral principles and customs which, most probably were initiated by Yahweh as the sovereign king. Thus Psalms 15 and other related Psalms truly display the ethical components of the temple theology of access to Yahweh's presence in Jerusalem (Groenewald 2009:426).

In its canonical context, Psalm 15 is viewed as a wisdom-influenced psalm with an essentially didactic orientation; its emphasis is to instruct those who seek access to Yahweh on the ethical demands of godliness (VanGemeren 1991:148; Kraus 1993:227; Davidson 1998:56; Wilson 2002:296; Grogan 2008:61). Jews hardly pray long without meditating on Yahweh's Torah (Pss 1; 19; 119). Yahweh's Torah stands at the centre of Jewish spirituality. Israel's preoccupation with Yahweh's Torah is an uncompromising and practical realism about the given norms of their life, the ethical context of their faith and public character of true religion. It reminds them of the primal mode of faithfulness and knowing Yahweh is compliance to his Torah (Brueggemann 2007:50). Sumpter (2013:196) commenting on Psalm 15 as Torah-wisdom influenced psalms notes:

Psalm 15 is not just a "Torah psalm;" it is a "Torah entrance psalm." In other words, the law is subordinated to one of Israel's key institutions: the sacred sanctuary in Zion. In this context, "Torah" functions as a means of access to this special place, understood to be the locus of the blessing that obedience may bring. The law is a means to which the reality in the temple is its end. It is this reality that is the desired destination of the psalmist, the place where he can enjoy the "stability" he yearns for (v. 5; cf. Ps 24:1-2).

The superscription ascribes the psalm to David. In light of the fact that David, according to the later biblical tradition, is considered as responsible for the composition of many hymns and the organization of the temple liturgy (cf. I Chron 25:1ff; Wendland 1998:23), it might be inferred that the psalm was most likely composed for communal worship in the temple at Jerusalem. In this regard, its instructional purpose of guiding a congregation of Yahweh's seekers about what is required of living in a community directed by wisdom and integrity of life cannot be overlooked (Mays 1994:85; Goldingay 2006: 219). What is clear in Psalm 15 is that there is an agreement in the liturgical concerns raised in the opening question and the answer proposed in the ethical descriptions and/or instruction. The following analysis of the content of Psalm 15 would indicate that to gain access to Yahweh's presence and obtain a hearing, the internal and external condition of the seeker has to be in harmony with Yahweh whose aid is being sought.

1 The psalms' title indicates that it is a song.

(mostly translated psalm) means a song or melody sung with musical complement (Brown, Driver & Briggs 1997:274).

The psalm opens with questions regarding access to the reality within Yahweh's dwelling place. The specific questions are addressed by worshippers to Yahweh, thus making it unusual in comparison with unnamed addresses in similar passages (cf. Ps 24:3; Isa 33:14-16; Mic 6:6-8; and Zech 7) (Gerstenberger 1988:15). Day (1999:60) notes that Torah-entrance psalms have three principal parts: question about who may be allowed access to Yahweh's dwelling place; answer, setting out the ethical requirements; and word of blessing with regards to those who are qualified to enter Yahweh's dwelling place. The questions in verse 1 are set in close parallel. The terms  [tent] and

[tent] and  [Holy Mountain] refer to the temple in Jerusalem, with

[Holy Mountain] refer to the temple in Jerusalem, with  emanating from the tabernacle traditions. The late rabbinic word for divine presence, shekinah, also assumes advantage of pitching a tent elsewhere. In the psalms, the distinctive description of the Jerusalem sanctuary, however, is the name Zion. It is found predominantly in the form

emanating from the tabernacle traditions. The late rabbinic word for divine presence, shekinah, also assumes advantage of pitching a tent elsewhere. In the psalms, the distinctive description of the Jerusalem sanctuary, however, is the name Zion. It is found predominantly in the form  Mount Zion] (Pss 48:2, 11; 72:2; 78:68; 125:1). Yahweh dwells here or is enthroned (Pss 9:11; 76:2; 99:2). From Zion Yahweh shines forth, his theophany is manifest, help comes for the oppressed (Pss 14:7; 20:2; 53:6), and Yahweh's blessing goes forth (Pss 128:5; 134:3). On Zion, the songs of Israel's praise ring out (Pss 65:1; 147:12). As the

Mount Zion] (Pss 48:2, 11; 72:2; 78:68; 125:1). Yahweh dwells here or is enthroned (Pss 9:11; 76:2; 99:2). From Zion Yahweh shines forth, his theophany is manifest, help comes for the oppressed (Pss 14:7; 20:2; 53:6), and Yahweh's blessing goes forth (Pss 128:5; 134:3). On Zion, the songs of Israel's praise ring out (Pss 65:1; 147:12). As the  [Mount of Yahweh], Zion is the LORD's holy mountain (Pss 2:6; 3:5; 15:1; 43:3; 48:1), the "holy place" of the holy God [

[Mount of Yahweh], Zion is the LORD's holy mountain (Pss 2:6; 3:5; 15:1; 43:3; 48:1), the "holy place" of the holy God [ Ps 24:3], where he is present and where he has his holy habitation (Pss 68:5; 76:2) (Kraus 1992:73-74).

Ps 24:3], where he is present and where he has his holy habitation (Pss 68:5; 76:2) (Kraus 1992:73-74).

The two verbs:  [stay or abide] and

[stay or abide] and  [dwell] indicate temporary settlement in the temple. Thus the extraordinary issue about Psalm 15 is the democratizing of the idea of residence on the holy mountain. Here, what was a priestly prerogative now becomes the right of everyone who mirror the character of Yahweh (Crenshaw 2001:161; Brueggemann & Bellinger 2014:83). What this implies is precisely spelt out as the answer to the question(s):

[dwell] indicate temporary settlement in the temple. Thus the extraordinary issue about Psalm 15 is the democratizing of the idea of residence on the holy mountain. Here, what was a priestly prerogative now becomes the right of everyone who mirror the character of Yahweh (Crenshaw 2001:161; Brueggemann & Bellinger 2014:83). What this implies is precisely spelt out as the answer to the question(s):  [LORD, who may sojourn in your tent?]/

[LORD, who may sojourn in your tent?]/

[who may dwell on your holy mountain?]. Underlying these questions is the appreciation that the temple/sanctuary is a place of Yahweh's presence (Boloje & Groenewald 2014a:354-381) that is both a threat as well as promises life. It presumes that Yahweh is holy and accessible. To enter the holy place is both risky and life-giving. The question(s) is thus about who might receive the favours of hospitality from this powerful, life-giving present reality (Brueggemann & Bellinger 2014:82-83). The interrogative

[who may dwell on your holy mountain?]. Underlying these questions is the appreciation that the temple/sanctuary is a place of Yahweh's presence (Boloje & Groenewald 2014a:354-381) that is both a threat as well as promises life. It presumes that Yahweh is holy and accessible. To enter the holy place is both risky and life-giving. The question(s) is thus about who might receive the favours of hospitality from this powerful, life-giving present reality (Brueggemann & Bellinger 2014:82-83). The interrogative  [who?] indicates that the question being asked is about issues of identity. The identity issues reaches back to Psalm 1 where the faithful are described as those who follow not the counsel of the wicked but Yahweh's Torah. The response in verses 2-5a focuses on general descriptions, followed by specific actions and attitudes, reminiscent of Yahweh's Torah (Kessler 2013:400; Brueggemann & Bellinger 2014:83).

[who?] indicates that the question being asked is about issues of identity. The identity issues reaches back to Psalm 1 where the faithful are described as those who follow not the counsel of the wicked but Yahweh's Torah. The response in verses 2-5a focuses on general descriptions, followed by specific actions and attitudes, reminiscent of Yahweh's Torah (Kessler 2013:400; Brueggemann & Bellinger 2014:83).

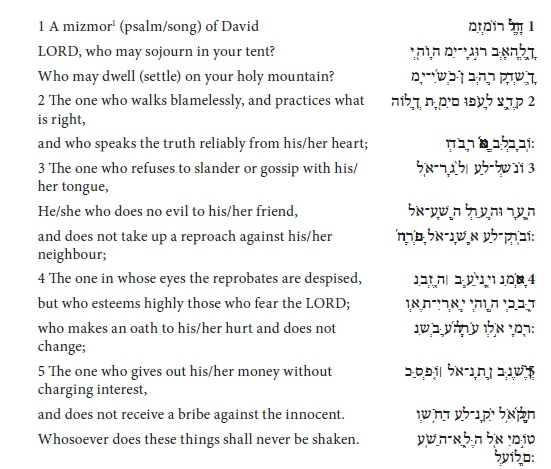

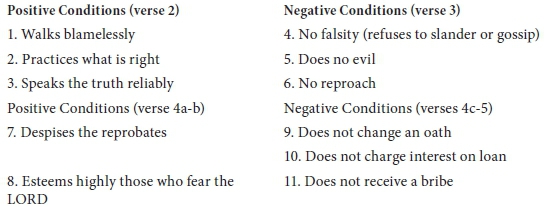

The responses provided by to the questions are mostly stated in the negative. In verse 2, the psalm employs participial verb forms, denoting customary or habitual lifestyle, to articulate a response. The psalm presents 10 entrance conditions which have been considered as part of the Decalogue tradition in the Pentateuch (Davidson 1988:56; Knight 2001:70-71; Brueggemann & Bellinger 2014:82). However, an 11 fold structure can be noticed in light of the three conditions presented in verse 4. Craigie's (2004:150-151) 10 structural portrayals of the moral conditions of the faithful that comply with Yahweh's Torah, in addition with the 11th observable condition and some other modifications are shown below:

Those who are eligible to access Yahweh's dwelling place for divine help or worship are those whose lives are characterized by  [walking blamelessly],

[walking blamelessly],  [practicing what is right], and

[practicing what is right], and  [speaking the truth reliably from their heart] (v. 2). The parts of life confirm harmoniously, including speech. To walk blamelessly implies an ethical way of life, wholeheartedly dedicated to the ways of Yahweh (cf. Gen. 6:9; 17:1; Ps. 119:1). The verb

[speaking the truth reliably from their heart] (v. 2). The parts of life confirm harmoniously, including speech. To walk blamelessly implies an ethical way of life, wholeheartedly dedicated to the ways of Yahweh (cf. Gen. 6:9; 17:1; Ps. 119:1). The verb  [blameless] carries the idea of integrity. While the idea of "walking blamelessly" does not imply a life of "sinless perfection," the emphasis however lies on the determination of the will to do what is right. It implies a consistency in attempting to carry out that determination in the difficult realities of life (Kessler 2013:400). The idea of integrity, manifested in ethical conducts

[blameless] carries the idea of integrity. While the idea of "walking blamelessly" does not imply a life of "sinless perfection," the emphasis however lies on the determination of the will to do what is right. It implies a consistency in attempting to carry out that determination in the difficult realities of life (Kessler 2013:400). The idea of integrity, manifested in ethical conducts  is an essential and distinguishing mark of those who are in good standing with Yahweh and will find his acceptance. The idea is also set as an ethical standard of living, especially in terms of human interpersonal relationship in several passages in the psalms and other wisdom literature (e.g., Pss 18:24; 101:2; 119:1; Job 12:4; 36:4; 37:16; Prov. 11:5; 28:18). This idea is reiterated in the phrase

is an essential and distinguishing mark of those who are in good standing with Yahweh and will find his acceptance. The idea is also set as an ethical standard of living, especially in terms of human interpersonal relationship in several passages in the psalms and other wisdom literature (e.g., Pss 18:24; 101:2; 119:1; Job 12:4; 36:4; 37:16; Prov. 11:5; 28:18). This idea is reiterated in the phrase  [who practices what is right]. The Hebrew verb

[who practices what is right]. The Hebrew verb  [right, justice, righteous] basically denotes that which is fair and just and complies with Yahweh's precepts (Reimer 1998:746). It implies "conformity to an ethical or moral standard" (Harris, Archer & Waltke 1980:1879). The ethical dimension of

[right, justice, righteous] basically denotes that which is fair and just and complies with Yahweh's precepts (Reimer 1998:746). It implies "conformity to an ethical or moral standard" (Harris, Archer & Waltke 1980:1879). The ethical dimension of  encompasses such conducts of love, mercy, truth, expressions of loyalty and mercy that characterize human interpersonal relationships in community of humanity. This however, is demonstrated only through compliance to Yahweh's standards that are set out in his word. The one who does what is right [

encompasses such conducts of love, mercy, truth, expressions of loyalty and mercy that characterize human interpersonal relationships in community of humanity. This however, is demonstrated only through compliance to Yahweh's standards that are set out in his word. The one who does what is right [ ] lives in clear contrast to the doers of evil [

] lives in clear contrast to the doers of evil [ ] , the shared characterization of the enemies in the Psalter (Pss 5:5; 6:8; 14:4). Discussion on the ethical requirements of

] , the shared characterization of the enemies in the Psalter (Pss 5:5; 6:8; 14:4). Discussion on the ethical requirements of  illuminates the message of the prophets, whose call for justice and righteousness manifest throughout various contexts of their ministry (cf. Amos 5:15, 23-23; Jer. 22:1-4).

illuminates the message of the prophets, whose call for justice and righteousness manifest throughout various contexts of their ministry (cf. Amos 5:15, 23-23; Jer. 22:1-4).

Speaking and doing are intimately connected in verses 2 and 3. The psalm stresses integrity of speech. Those who are prepared for worship act must "speak the truth reliably from their heart" [ ]. A faithful lifestyle must be characterized by speech. That which is uttered must be a genuine representation of what the person truly is, thinks and feels with every sense of honesty, transparency and sincerity (Kessler 2013:401). The psalm characterized the Yahweh's seeker as someone "who refuses to slander or gossip with his/her tongue"

]. A faithful lifestyle must be characterized by speech. That which is uttered must be a genuine representation of what the person truly is, thinks and feels with every sense of honesty, transparency and sincerity (Kessler 2013:401). The psalm characterized the Yahweh's seeker as someone "who refuses to slander or gossip with his/her tongue"  (v 3a). Here, the psalmist employs a vivid imagery in the description of Yahweh's guest. The Hebrew verb

(v 3a). Here, the psalmist employs a vivid imagery in the description of Yahweh's guest. The Hebrew verb  [to slander, gossip] is used as a denominative of

[to slander, gossip] is used as a denominative of  [foot] translated as "go on foot, spy, go about (maliciously, as slanderer)" (Brown et al. 1997:920; Harris et al. 1980:2113). The inappropriateness as well as the dangers associated with the wrong use of the tongue in human community and especially for Yahweh's guest, receives attention in key OT literary genres, such as prophetic (Jer 6:28; 18:18; Ezek 22:9) and wisdom (Prov 10:31; 11:13; 12:19; 18:21; 21:6; 26:28; Pss 10:7; 12:3; 78:36; ) texts.

[foot] translated as "go on foot, spy, go about (maliciously, as slanderer)" (Brown et al. 1997:920; Harris et al. 1980:2113). The inappropriateness as well as the dangers associated with the wrong use of the tongue in human community and especially for Yahweh's guest, receives attention in key OT literary genres, such as prophetic (Jer 6:28; 18:18; Ezek 22:9) and wisdom (Prov 10:31; 11:13; 12:19; 18:21; 21:6; 26:28; Pss 10:7; 12:3; 78:36; ) texts.

From this point onward, the psalm moves to a sequence of behaviours that are mostly social and relational in nature. The one who is prepared to enter Yahweh's presence as his guest for worship understands that there are two contrasting groups of individuals in the world: the faithful and the wicked. This contrast between the two groups underpins the psalm (Brueggemann & Bellinger 2014:83). The one who enters the temple to seek Yahweh is one who does not maliciously slander others, nor commits evil against a friend, nor take up a reproach (illegitimately) against his/her neighbour (verse 3). The relational contexts of the term  [neighbour, friend, companion] (Harris et al. 1980:2186) is well known especially in the psalms and in Sinai Covenant and Priestly Theology. The term refers to a fellow member of the covenant community (Ex 20:17; Lev 19:17-18) (Kessler 2013:401) and the statements requires that the true Yahweh's worshipper should not fabricate a reproach against his/her neighbour under no circumstance.

[neighbour, friend, companion] (Harris et al. 1980:2186) is well known especially in the psalms and in Sinai Covenant and Priestly Theology. The term refers to a fellow member of the covenant community (Ex 20:17; Lev 19:17-18) (Kessler 2013:401) and the statements requires that the true Yahweh's worshipper should not fabricate a reproach against his/her neighbour under no circumstance.

The summit of the literary structure of Psalm 15 in relation to social and relational behaviours is seen in the statements in verses 4a-5. The person's behaviour to the righteousness of Yahweh results to a profound estrangement from the values and ways of those who reject Yahweh and to a high esteem of those who fear the LORD. In the expression:

[in his eyes the reprobate is despised], the verb

[in his eyes the reprobate is despised], the verb  translated "reprobate" is a Nipha'l participle of a root

translated "reprobate" is a Nipha'l participle of a root  that means "to reject, or refuse" (Harris et al. 1980:1139). The term is used theologically to describe all categories of persons who rejects the LORD and his Torah (Num 11:20; 1 Sam 8:7; 10:19; Hos 4:6; Amos 2:4; Isa 5:24; Jer. 6:19) and by implication rejected by Yahweh (Hos 9:17). To be "despised in one's eyes" suggests looking upon something as immaterial or useless and to disrespect it (2 Sam 12:9; Esth 1:17). Here, the psalm emphasis is not upon disassociation from the wicked but an inner disengagement from their values. The psalm thus echoes wisdom motif by encouraging Yahweh's worshipers to esteem highly those who fear the LORD. The contrast between the

that means "to reject, or refuse" (Harris et al. 1980:1139). The term is used theologically to describe all categories of persons who rejects the LORD and his Torah (Num 11:20; 1 Sam 8:7; 10:19; Hos 4:6; Amos 2:4; Isa 5:24; Jer. 6:19) and by implication rejected by Yahweh (Hos 9:17). To be "despised in one's eyes" suggests looking upon something as immaterial or useless and to disrespect it (2 Sam 12:9; Esth 1:17). Here, the psalm emphasis is not upon disassociation from the wicked but an inner disengagement from their values. The psalm thus echoes wisdom motif by encouraging Yahweh's worshipers to esteem highly those who fear the LORD. The contrast between the  [righteous, Yahweh's fearer] and

[righteous, Yahweh's fearer] and  [the wicked] is clear in Psalm 1 (cf. Mal 3:13-21 [MT]). While disengagement from the values of the wicked is encouraged, esteeming highly those who fear the LORD and establishing a vital relationship of communion with them highlights ethical behaviours expected of Yahweh's seekers in a community of humanity.

[the wicked] is clear in Psalm 1 (cf. Mal 3:13-21 [MT]). While disengagement from the values of the wicked is encouraged, esteeming highly those who fear the LORD and establishing a vital relationship of communion with them highlights ethical behaviours expected of Yahweh's seekers in a community of humanity.

A follow-up to this value system is the individual's commitment to honour promises sworn in Yahweh's name, even if doing so will result to his/her personal disadvantage:  [he who makes an oath to his/ her hurt and does not change] (verse 4c). There are other passages that stress the significance of keeping one's vows and oaths (Lev 5:4; 2 Chron 15:15; Num 30:11; 1 Kg 2:43; Neh 6:18). While the conclusion of this Hebrew verse is obscure, Kessler (2013:401) notes "the reference might be to honouring a promise to sell a certain good at a given price, even if a higher price could be obtained by breaking one's word. This economic context may be inferred by the reference to loaning money at interest in the following phrase." The rendering "He swears to [his] neighbour and does not change," suggest integrity of speech (Brueggemann & Bellinger 2014:83).

[he who makes an oath to his/ her hurt and does not change] (verse 4c). There are other passages that stress the significance of keeping one's vows and oaths (Lev 5:4; 2 Chron 15:15; Num 30:11; 1 Kg 2:43; Neh 6:18). While the conclusion of this Hebrew verse is obscure, Kessler (2013:401) notes "the reference might be to honouring a promise to sell a certain good at a given price, even if a higher price could be obtained by breaking one's word. This economic context may be inferred by the reference to loaning money at interest in the following phrase." The rendering "He swears to [his] neighbour and does not change," suggest integrity of speech (Brueggemann & Bellinger 2014:83).

The last verse presents two statements that focus on the individual's behaviour with respect to financial matter. The one who seeks Yahweh's aid does not exploit others through the exacting of interest on a loan

(verse 5a). The practice of usury or lending money in ancient Near Eastern society with all associated problems is well known. The OT law allowed for the lending of money to outsiders but forbade demanding interest from fellow Israelites (Ex 22:25-27; Lev 25:35-38; Deut 16:19-20). Although scholars debate whether this was an absolute prohibition on all interest or whether in the case of commercial or business circumstances interest may be permitted (Buch 2005:13-22; Kessler 2013:401), the positive ideals that can be deduced from this are the concern for justice and mercy which are required for entrance into Yahweh's holy place for worship. The other statement in the verse affirms that the faithful Yahweh seeker "does not receive a bribe against the innocent"

(verse 5a). The practice of usury or lending money in ancient Near Eastern society with all associated problems is well known. The OT law allowed for the lending of money to outsiders but forbade demanding interest from fellow Israelites (Ex 22:25-27; Lev 25:35-38; Deut 16:19-20). Although scholars debate whether this was an absolute prohibition on all interest or whether in the case of commercial or business circumstances interest may be permitted (Buch 2005:13-22; Kessler 2013:401), the positive ideals that can be deduced from this are the concern for justice and mercy which are required for entrance into Yahweh's holy place for worship. The other statement in the verse affirms that the faithful Yahweh seeker "does not receive a bribe against the innocent"  to pervert the course of justice. The OT speaks in many instances against bribery since it subverts the course of justice, ruins human relationships, and destroys the fabric of human society (Ex 23:8; Deut 10:17; Prov 21:14; Isa 5:23; Ezek 22:12; Mic 3:11).

to pervert the course of justice. The OT speaks in many instances against bribery since it subverts the course of justice, ruins human relationships, and destroys the fabric of human society (Ex 23:8; Deut 10:17; Prov 21:14; Isa 5:23; Ezek 22:12; Mic 3:11).

The closing statement of the psalm is a word of blessing with regards to those who are qualified to enter Yahweh's dwelling place. The first section of the statement:  [whosoever does these things] speaks of the descriptive requirements of verse 2 and in addition, to the more specific behaviours expected of all seekers of Yahweh. The other part of the statement which is a blessing:

[whosoever does these things] speaks of the descriptive requirements of verse 2 and in addition, to the more specific behaviours expected of all seekers of Yahweh. The other part of the statement which is a blessing:  [shall not be shaken] serves as an appropriation of the opening questions:

[shall not be shaken] serves as an appropriation of the opening questions:  [who may stay around as a sojourner in your tent?]

[who may stay around as a sojourner in your tent?]  [who may dwell on your holy mountain?]. Such a person whose life direction is consistent with Yahweh's Torah is promised that his/her stability will never ultimately be shaken and moved like Mount Zion (Ps 125:1). Thus what Yahweh's dwelling place is at the beginning of the psalm, the faithful Yahweh seeker is at the end. Entering Yahweh's presence, for the faithful brings security, for the venue of the divine presence is the secure place of the rock. The divine presence provides protection and stability and this portrait of Yahweh's holy place, where the life-giving God is encountered, vitalizes the hope ancient Israel as a community (Brueggemann & Bellinger 2014:84).

[who may dwell on your holy mountain?]. Such a person whose life direction is consistent with Yahweh's Torah is promised that his/her stability will never ultimately be shaken and moved like Mount Zion (Ps 125:1). Thus what Yahweh's dwelling place is at the beginning of the psalm, the faithful Yahweh seeker is at the end. Entering Yahweh's presence, for the faithful brings security, for the venue of the divine presence is the secure place of the rock. The divine presence provides protection and stability and this portrait of Yahweh's holy place, where the life-giving God is encountered, vitalizes the hope ancient Israel as a community (Brueggemann & Bellinger 2014:84).

3. Ethical implications of Psalm 15 for worship

Ethics of the OT/Hebrew Bible is understood to be a kind of stepmother in OT scholarship which has proved to be a most difficult one to handle coupled with the fact that the literature related to it has been amazingly scanty (Otto 2012:3; Barton 2014:15). Majority of questions relate to the essential issues in the quest for understanding ethics of the ancient Hebrew mind and the problem of how to contextualise them in contemporary contexts (Human 2012:vii). Much scholarly research on OT ethics has been within the limits of academic discipline, where it is not uncommon to treat it "without faith or ecclesia commitments" (Carroll 2012a:210). While sources of ethics can be explored from several literary genre of the OT (Barton 2014:14f), the psalms are neglected sources in work on ancient Israelite ethics. The psalms advance important proposals on the nature and value of life, of life lived in a community of humanity, behaviours towards neighbours and enemies, and the objectives of human behaviour (Barton 2014:16). They are concerned with social ethics, not with matters of ritual purity (cf. Pss 15, 24, 71, 101), and of Torah spirituality (Pss 19 and 119). They are important sources for considering "the ends of life," and of information about what were believed to be the character of Yahweh (Barton 2014:36-38).

Psalm 15 is an important psalm for the Psalter's emphasis on ethics and worship. The psalm understands Yahweh to be both holy and available, and to be the one who provides guidance in preparing for worship and in living in Israel's covenant community (Brueggemann & Bellinger 2014:84). The psalm is a description of those living within the limits of Yahweh's covenant grace. Yahweh's Torah proved to be the foremost visible instrument of unification. Thus forming their identity as a people of the revealed word of Yahweh (Sinai event), the emerging Jewish community adhered to that very foundation of their faith. One of the most powerful theological metaphors was Yahweh's covenant with them (Gerstenberger 2014:343). Everyone who is able to understand is visualized to listen to the stipulations of that covenant, and Yahweh in person is understood to proclaim to them (through the liturgical speaker). Individual correctness  righteousness) and corporate obedience (cultic orthodoxy) were the goals of the community's aspiration (Gerstenberger 2014:343-344). In this regard, reflection on Psalm 15 offers the following ethical implications for both individual and corporate experience of worship.

righteousness) and corporate obedience (cultic orthodoxy) were the goals of the community's aspiration (Gerstenberger 2014:343-344). In this regard, reflection on Psalm 15 offers the following ethical implications for both individual and corporate experience of worship.

4. Correspondence between words and heart

As noted earlier in this article, the theology of access to Yahweh's presence focuses on words (speech) as the means that vitalize the divine-human interchange. The prerequisite of acceptable worship is the correlation between speech and heart. Psalm 15 challenges worshippers of Yahweh that neither a demanding journey nor physical presence at a sacred venue is in and of itself adequate to provide access to Yahweh's presence and gain a hearing. Instead, the internal condition of the worshipper has to be in harmony with his/her words (speech) as the vehicles of access to Yahweh's presence. Words (speech) and deeds must correspond. The intimacy between speech and heart is what animates the descriptions of Psalm 15 in verses 2 and 3. The participial expressions "walking, doing, and speaking" point to sustained or habitual integrity, just dealings, and authenticity. They singled out a person of integrity, and imply wholeness, a sense of unity in which mind and body join together to produce dependable person. The walking is complemented by action of an appropriate manner; acts flowing from righteousness.

Psalm 15 stresses integrity of speech. Those who are prepared for worship act must "speak the truth reliably from their heart" [ ]. Since the psalmist knows that appearing before Yahweh is a risky endeavour, especially if an individual's inner condition and outward conduct lack integrity, the moral fervour is matched by the demands imposed on anyone who contemplates access to Yahweh's presence (Crenshaw 2001:158). The centre of human life is the heart [

]. Since the psalmist knows that appearing before Yahweh is a risky endeavour, especially if an individual's inner condition and outward conduct lack integrity, the moral fervour is matched by the demands imposed on anyone who contemplates access to Yahweh's presence (Crenshaw 2001:158). The centre of human life is the heart [ ]. It is the site of all thought, planning, reflection, explanation, and ambition (Pss 4:4; 10:6; 15:2; 20:4; 33:11, 22). It is the place where the whole person experiences or suffers the full weight of joy (Pss 4:7; 19:8; 33:21; 64:6; 105:3), sorrow, anxiety, and fear (Pss 25:17; 55:4; 61:2), bitterness (Ps 73:21), and hope (Pss 28:7; 112:7). The entire process, of reflection, planning, and deciding takes place in hidden depths of the heart. The heart can be described as

]. It is the site of all thought, planning, reflection, explanation, and ambition (Pss 4:4; 10:6; 15:2; 20:4; 33:11, 22). It is the place where the whole person experiences or suffers the full weight of joy (Pss 4:7; 19:8; 33:21; 64:6; 105:3), sorrow, anxiety, and fear (Pss 25:17; 55:4; 61:2), bitterness (Ps 73:21), and hope (Pss 28:7; 112:7). The entire process, of reflection, planning, and deciding takes place in hidden depths of the heart. The heart can be described as  [perverse, Ps 101:4]. In the psalms several statements describe the heart. Human petitions, divine promises, and divine renewal involve the

[perverse, Ps 101:4]. In the psalms several statements describe the heart. Human petitions, divine promises, and divine renewal involve the  [pure heart, Pss 24:4; 51:10; 73:1]. Yahweh can persuade the human heart to good (Pss 119:36; 112; 141:4), such that Yahweh's Torah may dwell in the heart (Pss 37:31; 40:8), and so that it becomes possible to speak of those who are

[pure heart, Pss 24:4; 51:10; 73:1]. Yahweh can persuade the human heart to good (Pss 119:36; 112; 141:4), such that Yahweh's Torah may dwell in the heart (Pss 37:31; 40:8), and so that it becomes possible to speak of those who are  [upright in heart, Pss 7:10; 64:10; 94:15; 125:4] (Kraus 1992:145).

[upright in heart, Pss 7:10; 64:10; 94:15; 125:4] (Kraus 1992:145).

Crenshaw (2001:162) remarks, "Those who hope to dwell in Yahweh's presence must avoid three specifics: they must not "tread on their tongues," inflict injury on neighbours, or bring shame on acquaintances." These conditions call to mind the Decalogue prohibition: "You shall not bear false witness against your neighbour" (Ex 20:6). In the entire framework of Book I, it is clear that anyone who uses his/her tongue in this manner acts in stark contrast to Yahweh's righteousness and is treated like the psalmists' enemies who speaks treacherously (Ps 10:7; 12:3;4-5; 14:1 ). Words uttered to Yahweh thus must reflect both the personhood of God and the personhood of the worshipper. Since access to Yahweh's presence for worship and/ or divine aid implies true dialogue in a personal relationship, Psalm 15 challenges the faithful Yahweh-seekers to assume responsibility for the words spoken. In the community in which Yahweh dwells, the values of honesty, justice and righteousness must be embodied. Truly, the sacrifice that is pleasing and/or acceptable to Yahweh is a broken spirit; "a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise" (Ps 51:17, NASB).

5. Solidarity in the context of relationships

The Psalms (15 and 24) that seek to monitor access to Yahweh's dwelling place have parallels in OT texts (Deut 23:1-9; Isa 33:15-16; Mic 6:6-8). While the author of Deuteronomy concentrates on instances of ritual purity or ethnic membership, the prophetic texts are concerned with ethical conduct and proper reverence. The prophetic text has righteousness rather than integrity but includes bribery and other acts of greed and dishonesty:

He who walks righteously, and speaks with sincerity, he who rejects unjust gain, and shakes his hands so that they hold no bribe; he who stops his ears from hearing about bloodshed, and shuts his eyes from looking upon evil; he will dwell on the heights; his refuge will be the impregnable rock; his bread will be given him; his water will be sure (Isa 33:15-16, NASB).

In Micah, the prophet reflects on the fundamental question: what does Yahweh require of mortals? Having rejected various options like burnt offerings, calves of a year old, rams, rivers oil, sacrificing one's firstborn (Mic 6:6-7), he concedes that the answer has already been provided: "He has told you, O man, what is good; and what does the LORD require of you but to do justice, to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God" (Mic 6:8). In the face of heightened ethical sensitivity, Micah cast his lot with those who opted for justice, kindness, and a humble walk with Yahweh (Crenshaw 2001:165).

Psalm 15 implies that Yahweh-seekers lay under demanding moral imperatives. Access to Yahweh's presence parallel solidarity in the context of relationships: solidarity with Yahweh and relationship with humans. Just as Yahweh's reputation rests upon acts of justice and tender mercies, so those who wish to access Yahweh's dwelling place for worship or divine aid must embody these attributes. Standing in solidarity with Yahweh implies a stand against evil. Psalm 15 holds that those who practice evil, oppression, and deceit will not have access to Yahweh's presence, boldly expecting their needs to be met (cf. Ps 50:16-22; Kessler 2013:439). Yahweh's concerns for humanity in general and his people in particular is that they deal with injustice and oppression in whatever shape and form and that their economic structure be reputed for justice and social accountability (Friedman 2011:299; Boloje & Groenewald 2014b:7).

The OT fully articulates the apprehension that exists in ancient Israelite community over relationships between Yahweh's worship and the actions of those who worship him in relation to their neighbours. Although the tension is hardly resolve, a strong concern can be seen in the prophetic literature where Yahweh's worshippers (i.e., the Israelites) are motivated to look beyond legalistic cultic rituals and comply wholeheartedly with Yahweh's Torah and concerns for justice and social responsibility (Boloje & Groenewald 2015:7). The prophets are clamorous in their criticisms of worship as it relates to social and virtues ethics (Amos 4:4-5; 5:21-23; Mic 6:6-8; Isa 1:11-14) (Barton 2007:111-120; Carroll 2009:42-45). In order to replace concerns for ritual purity, therefore, Psalm 15 summons Yahweh's seekers and worshippers to a celebration of Yahweh's ordained reality within a context that exhibits moral coherence (experienced as obedience) and makes a radical difference to the keeping of Yahweh's promises. The concerns of the psalmist therefore is to create such remarkable and dependable model of moral behaviours that will make Israel as well as Yahweh's worshippers as an ideal portrait of the community in which Yahweh dwells.

6. Conclusion

At the outset, it was stated that the primary concern of this article is to examine such necessary preconditions of access to Yahweh's presence through the textual window of Psalm 15. The exploration truly reveals that Psalm 15 constitute occasions for summing up ethical norms for acceptance in the religious community. It articulates the psalm's divine and didactic qualities, which must be singled out for emulation. The instructions in Psalm 15 are devoted mainly to social obligations rather than to specific religious actions. Psalm 15 skilfully brings together the experience of spiritual union with Yahweh (15:1) with solidarity in the context of relationships (15:25). Thus an attitude akin to prophetic proclamation by Amos, Isaiah, and Micah can be detected in the psalm. Access to Yahweh's presence as spelt out in Psalm 15 is ethical in nature. The psalm articulates goals for faithful and effervescent living not only in the covenant community of humanity in Israel but also faith communities in the 21st century.

There is truly a rhythm to life and worship in Psalm 15. Life lived in correspondence with word and heart and in line with Yahweh's covenant instruction prepares the faithful pilgrims for worship and encounter with the life-giving God and powerful worship vitalizes by such wonderful encounter with the life-giving God sustains viable covenant community living. The psalm thus invites the 21st century readers and Yahweh-seekers to contemplate on its anticipations. Indeed, individuals and communities who truly embody the ethical stipulations of Psalm 15 will experience the favours of hospitality from this powerful, life-giving present reality in worship. The wicked shall be shaken (Ps 10:6), but those who are honest and just in their interpersonal relationship "shall not be moved or shaken"  because Yahweh and his dwelling place are stable. Psalm 15 reveals that covenant communities that live out ethical ideals of justice and social responsibility in accordance with Yahweh's instruction are themselves Yahweh's dwelling places.

because Yahweh and his dwelling place are stable. Psalm 15 reveals that covenant communities that live out ethical ideals of justice and social responsibility in accordance with Yahweh's instruction are themselves Yahweh's dwelling places.

Bibliography

Anderson, Arthur A 1983. The Book of Psalms: Psalms 1-72 (The New Century Bible Commentary).Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Balentine, Samuel 1993. Prayer in the Hebrew Bible: The Drama of Divine- Human Dialogue. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Barton, John 2007. The Prophets and the Cult. In: Day, John (ed.) Temple and Worship in Biblical Israel (Proceedings of the Oxford Old Testament Seminar). New York: T&T Clark, 111-122. [ Links ]

Barton, John 2014. Ethics in Ancient Israel. Oxford: University Press. [ Links ]

Berkovic, Danijel 2009. Aspects and Modalities of God's Presence in the Old Testament. In: KAIROS - Evangelical Journal of Theology III (1):51-72. [ Links ]

Blaising, Craig 2012. Prepared for Prayer: The Psalms in Early Christian Worship. In: Wells, Richard & Neste, Ray Van (eds.) Forgetting Songs: Reclaiming the Psalms for Christian Worship. Nashville, Tennessee: B &H Publishing Group, 51-64. [ Links ]

Boloje, Blessing Onoriode & Groenewald, Alphonso 2014a. Malachi's Vision of the Temple: An Emblem of Eschatological Hope (Malachi 3:1-5) and an Economic Centre of the Community (Malachi 3:10-12). Journal for Semitics 23(2i): 354-381. [ Links ]

Boloje, Blessing Onoriode & Groenewald, Alphonso 2014b. Malachi's Concern for Social Justice: Malachi 2:17 and 3:5 and its Ethical Imperatives for Faith Communities. HTS Teologiese Studies/ Theological Studies 70(1), Art. #2072, 9 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v70i1.2072. [ Links ]

Boloje, Blessing Onoriode & Groenewald, Alphonso 2015. Malachi's Concept of a Torah-Compliant Community (Ml 3:22 [MT]) and its Associated Implications. HTS Teologiese Studies/ Theological Studies 71(3), Art. #2990, 9 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v71i3.2990 [ Links ]

Brown, Francis, Driver, R S and Briggs, C A (eds.) 1997. Hebrew and English lexicon of the Old Testament. Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers. [ Links ]

Broyles, Craig C 2005. Psalms Concerning the Liturgies of the Temple Entry. In: Flint, Peter et al. (eds.) The Book of Psalms: Composition and Reception (VT Sup 99). Leiden: Brill, 248-287. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, Walter & Bellinger, William H 2014. Psalms (New Cambridge Bible Commentary). New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, Walter 2007. Praying the Psalms: Engaging Scripture and the Life of the Spirit. Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers. [ Links ]

Buccellati, Giorgio 2000. Ethics and Piety in the Ancient Near East. In: Sasson, Jack (ed.) Civilization of the Ancient Near East. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 3:1685-1696. [ Links ]

Buch, Joshua 2005. Neshekh and Tarbit: Usury from Bible to Modern Finance. Jewish Bible Quarterly 33(1):13-22. [ Links ]

Carroll, Daniel RM 2009. Failing the Vulnerable: The Prophet and Social Care. In: Grant, Jamie A and Hughes, Dewl A (eds.) Transforming the World?: The Gospel and Social Responsibility. Grand Rapids: IVP, 33-47. [ Links ]

Carroll, Daniel RM 2012. Ethics and Old Testament Interpretation. In: Bartholomew, Craig G and Beldman, David GH (eds.) Hearing the Old Testament: Listening for God's Address. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 204-227. [ Links ]

Clements, Ronald E 1999. Worship and Ethics: A Re-Examination of Psalm 15. In: Graham, Matt Patrick Marrs, Rick R. & McKenzie, Steven (eds.) Worship and the Hebrew Bible: Essays in Honour of John T. Willis (JSOT Supplement Series 284). Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 78-94. [ Links ]

Clifford, Richard 2014. Psalms of the Temple. In: Brown, William (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of the Psalms. Oxford: University Press, 326337. [ Links ]

Collins, John J 2012. Always Alleluia: Reclaiming the True Purpose of the Psalms in the Old Testament Context. In: Wells, Richard & Neste, Ray Van (eds.) Forgetting Songs: Reclaiming the Psalms for Christian Worship. Nashville, Tennessee: B &H Publishing Group, 17-34. [ Links ]

Craigie, Peter C 2004. Psalms 1-50 (Word Biblical Commentary, vol. 19). Waco; Texas: Word Books Publishers. [ Links ]

Crenshaw, James L 2001. The Psalms: An Introduction. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Davidson, Robert 1998. The Vitality of Worship: A Commentary on the Book of Psalms. Grand Rapids, Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Day, John 1999. Psalms. London: T&T Clark. [ Links ]

Friedman, Hershey H 2011. Messages from the Ancient Prophets: Lessons for Today. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 1(20): 297-305. [ Links ]

Gerstenberger, Erhard 1988. Psalms Part 1: With an Introduction to Cultic Poetry (The Forms of the Old Testament Literature 14). Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Gerstenberger, Erhard S 2014. Non-Temple Psalms: The Cultic Setting Revisited. In: Brown, William P (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of the Psalms. Oxford: University Press, 338-349. [ Links ]

Goldingay, John 2006. Psalms: Baker Commentary on the Old Testament Wisdom and Psalms, 3 volumes. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [ Links ]

Groenewald, Alphonso 2009. Ethics of the Psalms: Psalm 16 within the context of psalms 15-24. Journal for Semitics 18(2): 421-433. [ Links ]

Grogan, Geoffrey W 2008. Psalms: The Two Horizons Old Testament Commentary. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Grohmann, Marianne & Zakovitch, Yair (eds.) 2009. Jewish and Christian Approaches to Psalms (Herders Biblische Studien 57). New York: Herder. [ Links ]

Gunkel, Hermann 1998. An Introduction to the Psalms: The Genres of the Religious Lyric of Israel. Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press. [ Links ]

Harris, Laird R, Archer, gl & Waltke, BK (eds.) 1980. Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament. Chicago: Moody Press. [ Links ]

Human, Dirk J (ed.) 2012. Psalmody and Poetry in Old Testament Ethics Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 572). New York: T & T Clark. [ Links ]

Hunter, Alastair G 2007. 'The Righteous Generation': The Use of DOR in Psalms 14 and 24. In: Rezetko, Robert et al. (eds.) Reflection and Refraction: Studies in Biblical Historiography in Honour of A. Graeme (VT Sup 113). Leiden: Brill, 187-206. [ Links ]

Kafang, Zamani B 2002. The Psalms: An Introduction to their Poetry. Kaduna: Baraka Press. [ Links ]

Kessler, John 2013. Old Testament Theology: Divine call and Human Response. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press. [ Links ]

Knight, George 2001. Psalms: Volume 1 (The Daily Study Bible series). Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Kraus, Hans-Joachim 1992. Theology of the Psalms. Translated by Keith Crim. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Kraus, Hans-Joachim 1993. Psalms1-59: A Continental Commentary. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Maloney, Les 2003. A Portrait of the Righteous Person. In: Restoration Quarterly 45(3): 151-164. [ Links ]

Mays, James Luther 1994. Psalms. Louisville, KY: John Knox. [ Links ]

Miller, Patrick D 1994. They Cried to the Lord: The Form and Theology of Biblical Prayer. Minneapolis: Augsburg Press. [ Links ]

Mowinckel, Sigmund 1962. The Psalms in Israel's Worship. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [ Links ]

Murphy, Roland E 2000. The Gift of the Psalms. Peabody, Mass: Hendrickson. [ Links ]

Otto, Eckart 2012. Hebrew Ethics in Old Testament Scholarship. In: Human, Dirk J (ed.). Psalmody and Poetry in Old Testament Ethics (Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 572). New York: T & T Clark, 3-13. [ Links ]

Perowne, Stewart 1976. The Book of Psalms. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House. [ Links ]

Reimer, David J 1998. קדצ. In: VanGemeren, Willem A (ed.) New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology & Exegesis (Volume 3). Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Sals, Ulrike 2009. Of Worms and Worlds: Psalm 22:7, 90:4; 85:11 in Light of Jewish-Christian Contacts in the Middle Ages. In: Grohmann, Marianne & Zakovitch, Yair (eds.) Jewish and Christian Approaches to Psalms (HBS 57). New York: Herder, 95-111. [ Links ]

Sumpter, Philip 2013. The Coherence of Psalms 15-24. Biblica 94(2): 186209. [ Links ]

Terrien, Samuel 1952. The Psalms and their Meaning Today. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merill Publishers. [ Links ]

VanGemeren, Willem 1991. Psalms (The Expositor's Bible Commentary). Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Vos, Cas JA 2004. Theopoetical and Liturgical Patterns of the Psalms with Reference to Psalm 19. In: Human, Dirk J and Vos, Cas JA (eds.) Psalms and Liturgy (JSOT Supplement Series 410). London: T. & T. Clark International, 251-289. [ Links ]

Weiser, Arthur 1962. The Psalms: A Commentary. Bloomsbury: SCM Press. [ Links ]

Wendland, Ernst 1998. Analyzing the Psalms. Dallas, Texas: Summer Institute of Linguistic. [ Links ]

Westermann, Claus1980. The Psalms: Structure, Content and Message. Augsburg: Minneapolis. [ Links ]

Westermann, Claus 1981. The Praise of God in the Psalms. Atlanta: John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Wilson, Gerald H 2002. Psalms (The NIV Application Commentary). Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Witvliet, John 2012. Words to Grow Into: The Psalms as Formative Speech. In: Wells, Richard & Neste, Ray Van (eds.) Forgetting Songs: Reclaiming the Psalms for Christian Worship. Nashville, Tennessee: B &H Publishing Group, 7-16. [ Links ]

Wood, Fred 1984. Psalms: Songs from Life. Nashville: Convention Press. [ Links ]

1 Lecturer at the Baptist Theological Seminary, Eku, Nigeria and Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Old Testament Studies, Faculty of Theology, University of Pretoria, with Prof. Alphonso Groenewald as research leader.

2 For varieties of themes of Yahweh's presence and details regarding aspects and modalities of God's presence in the Old Testament, see Berkovic (2009:51-72); Kessler (2013:386-393).

3 The name "Psalter" derives from the Greek word Salterion meaning "Stringed instrument," originally, later came to mean a 'collection of songs', and the word was used in the Codex Alexandrinus as the title of the Book of Psalms. In the Masoretic Text (the traditional text of the Hebrew Old Testament established by Hebrew scholars during the eighth and ninth centuries A.D.) the entire book is called Tehillim meaning "hymns" (Anderson 1983:23). While the word "psalm" refers to individual poems in the book, in this article, "Psalter" or "Psalms" will be used interchangeably and when fitted.

4 On Israel's cultic calendar (Ex 23:10-19; 34:18-26; Deut 16:1-17; Lev 23:4-44; Num 28-29).