Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Stellenbosch Theological Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2413-9467

versión impresa ISSN 2413-9459

STJ vol.1 no.2 Stellenbosch 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/STJ.2015.V1N2.A22

ARTICLES

Mission driven by fear and despair: The case of Kranspoort - the first Dutch Reformed Church mission station outside the Cape Colony

Kgatla, ST

University of Pretoria. Thias.kgatla@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article surveys the Dutch Reformed Church Mission Policy and the close collaboration of mission and politics. The 1948 Nationalist Party election victory brought about a host of laws designed to bring total control and dominance over black people's lives and their destiny. The Dutch Reformed Church was drawn into the government agenda to the extent that they lost their prophetic voice. The use of government instruments such as the forced removal of 'excess' and unwanted people from white farms was employed by the church. Black Christians that held a different political view were declared "no longer Christians" and forcefully removed from the mission stations. The pious outlook of mission did not help the church to realise that its social and political interests were against the love of Christ and thus the love of the neighbour.

Keywords: Squatters, mission policy, apartheid, separateness, military force, resistance, forced removals

In 1948, the Nationalist Part came to power in South Africa and in 1950 it came with a host of laws to reinforce and consolidate their policy of separate development and racial dominance. Driven by the fear of what influence the Communist Party could have on the natives and fear of racial mixing and the native majority's increasing protests, the white government promulgated laws that would ensure their dominance and total control of native affairs (Afrikaner fears and politics of despair: South African history online, accessed: 20/6/2015). Examples of some of the Acts that were enacted for the purpose of promoting white exclusive interests are:

- The Group Areas Act, No. 41 of 1950, with the primary objective of curbing the movements and influx of blacks into the cities and keeping them away from all the land reserved for the whites;

- The Population Registration Act, No. 30 of 1950, with the purpose of classifying people into three categories: white, black or coloured based on their appearance, social standing and descent (Afrikaner fear and politics of despair: South African History. [Online] [Accessed on 2/6/2015];

- The Bantu Authorities Act, No. 68 of 1951, with the aim of keeping the South African citizens apart along racial lines and pushing blacks out of the areas where they were not wanted;

- The Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act, No. 52 of 1951, with the aim of forcefully removing 'surplus' people from their landowners, local authorities and government places through evictions and demolishing their houses without compensation;

- The Natives Act, No. 67 of 1952, with the aim of introducing reference books, employment records, and tax payments. Black people had to carry their reference books with them day and night otherwise they would be charged criminally;

- The Natives Labour Act of 1953 with the aim of prohibiting Africans from striking and denying Africans with any right of a trade union;

- The Public Safety Act of 1953 with the aim of prohibiting the African National Congress from staging civil disobedience campaigns;

- The Criminal Amendment Act, No. 8 of 1953, with the aim of presuming any person associated with a guilty person as also guilty;

- The Bantu Education Act, No. 47 of 1953, with the aim of providing separate and inferior education;

- The Reservation of Separate Amenities Act, No. 49 of 1953, with the aim of providing separate recreational facilities for different races;

- The Natives Resettlement Act, No. 19 of 1954, with the aim of removing black people from any designated area for the convenience of white people;

- The Natives Act, No. 64 of 1956, with the aim of depriving Africans of the right to court protection against apartheid laws; and

- The Riotous Assemblies Act, No. 17 of 1956, with the aim of prohibiting all gatherings if the Minister of Justice has not given expressed permission (The Riotous Assemblies Act Commences: SAHO accessed 20/6/2015).

Included in this arsenal of regimes was The Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act, No.52 of 1951, which prevented illegal squatting and cleaned up the existing squatting (Changuion & Steenkamp 2012:1940).

These draconian laws would not have come at the right time for the Kranspoort mission solutions in 1955-1964. As the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) Mission Policy and apartheid policy shared the same objectives and destination, these laws were intensively used in promoting the mission agenda of the church. As Morris (1990:36) correctly puts it: "If Christian righteousness was ever the inspiration of national piety, it was surely suspended in 1950". Both the Nationalist Government and the Dutch Reformed Church went all out to create and enforce the laws that would effectively consolidate white dominance and rule over black people (Worden 2012:108).

The 1950s are also known for their vibrant black resistance and protests against the apartheid government. It is also known for the most brutal force from the government (Black Resistance of 1990: SAHO accessed 20/6/2015). The direct victims of these Acts included Albert Luthuli, Moses Kotane, Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo, Walter Sisulu and Joe Slovo as some of them were leaders within the ANC. In this decade, a number of ANC defiance and protest campaigns were held including the Defiance Campaign of 1952, the 1956 ANC Women's March to the Union Buildings, and the 1955 Kliptown Congress of the People. These defiance and protest campaigns possibly provoked the amount of brutality the apartheid regime had. The regime was poised to ensure the uncompromised implementation of the policy of separate development. Bodily pain was used to induce forced compliance on the part of black people. Moreover, massive forced removals of Africans were undertaken at a large scale during this period (Badat 2012; The SPP Reports Series Vol. 1-4).

1.Colonial conquest and capture of land under African occupation

The colonial conquest and the right of banishment of black people from their land was concluded in South Africa towards the first half of 19th century and the patches of land occupied by black people had to be appropriated in terms of the policy of separate development (The SPP Reports:31). "Native reserves" had become a convenient dumping place for "unwanted people" in order to facilitate domination, both economic and political, over the 'conquered' black people (Ibid). Changuion and Steenkamp (2012:101) intimate that by 1900 there were 45 reserves in the Transvaal to which blacks were relegated to. The policies for both the DRC and the white government were shaped by these different histories of resistance and conquest; the different needs of white people; the size of the African population and the degree of resistance against white rule (Ibid). For the policy to be implemented, an amount of force had to be used including forced removals and banishments of those who proved more influential in leading the resistance. Sometimes the settlers did not necessarily need the land occupied by blacks, but they wanted to exert their authority over those areas (Changuion & Steenkamp 2012:108).

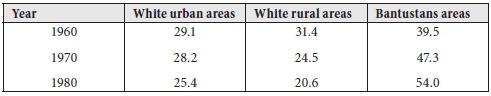

After the historic Afrikaner election in 1948, a host of laws systematically introduced demographic control over where various races could settle in the country. These included the ones that led to the creation of black homelands (Bantustans) between 1948 and 1959 (The SPP Reports Vol.2). According to The SPP Reports Vol.2, the demographic distribution of the African population was divided into three types: white urban areas, white rural areas, and Bantustan areas (Ibid). The table below gives some idea of the plan in percentages (The SPP Reports Vol. 2).

Demographic control was the result of political control that was designed to crush any black resistance violently or passively but with unwavering determination (Van Aswegen 1990:283). A plethora of legislations was introduced to enable the State to use any means necessary to restrict the activities of individuals or groups. According to The SPP Reports (Vol. 4:9), the policy of the forced removal and banishment of people was backed by the policy of the Bantustans where some chiefs were lured into accepting a 'false' dream of independence within a state.

By the second half of 1970, the communities that suffered banishment and forced removals were found all over South Africa. According to Badat (2012), these communities were found in the Eastern Cape (Ciskei, Transkei, Mpodoland, and Thembuland), the Free State (Witzieshoek), the Northern Province (Sekhukhuneland, Matlala, and Malebogo), the North West Province and many other parts of the country. As Dumisa Ntsebeza and Terry Bell (in Badat 2012: vii) argue, South Africans will never know how many people were banished and what happened to them. People who were forcefully removed or banished had no trial in court; they were provided no opportunity to defend themselves and yet they were denied their liberty (Ibid: vii). The only crime of those who were banished was that they either resisted apartheid policies or they were staying on land that the State wanted to take without compensation.

Kgatla (2013:9) has listed some of the reasons for the forced removal and banishment of black people. These include the following:

- Ethnic purity: The removal of people of colour from white designated areas was a purposeful policy designed by the government to remove, by violent and terror-inspiring means, black people from certain geographic areas for white exclusive use. The policy was a planned deliberate removal of black people from a specific territory by force or intimidation, in order to render that area homogenous and ethnically white.

- Military bases: Some black land would make very good military bases, especially those on open plains and on mountain ranges along the Spelonken. Black people living in those areas had to be removed peacefully, sometimes without compensation, or forcibly if they resisted.

- Exclusive self-interest: Although the 1913 and 1936 segregation laws were in operation, there were still fertile patches of land occupied by black people. The government had to find a way to acquire such prime land for white agricultural farmers and government projects, including military bases.

- Homeland policy: Homelands were established to achieve the grand policy of apartheid and some of them were situated in small areas. Ways had to be found to remove people from one area to another to make room for the homelands. Further forced removals were an essential tool of the government to strip all black people of any political rights as well as their citizenship.

- Implementation of the Group Areas Act: The Group Areas Act mandated residential segregation and black people were forcibly removed to make room for the new dispensation. Many 'surplus' black people were removed from towns and dumped in reserves where they would provide cheap labour (Kgatla 2013:9).

Once the government had decided that people should move from a particular spot to another, nothing would stop them from realising the goal (Mohlamme nd: 1). Methods used by the government to remove 'unwanted people' included persuasion through incentives, intimidation and the appointment of collaborators. Should incentives fail to persuade people to move voluntarily, then coercive methods such as threatening people, denying people grazing rights or detaining leaders were used to instil fear in people (Mohlamme nd:15). On the one hand, a special branch police (known for their secretive methods and torture) may be employed to do this, on the other hand, chiefs or collaborators are appointed to exert pressure on people to leave. If all of the above fails, brutal force may be applied to compel forced compliance.

2.The flip side of the same coin

As already stated at the beginning of this paper, lethal apartheid laws would not have come at the better times for a missionary solution of black resistance at Kranspoort Mission Station. A similar situation which required the same laws such as the Group Areas Act was brewing in Bethesda Mission Station, some 100 km west of Kranspoort (Moeng 2015). The black Christians who constituted the Christian community at "Stasie" had become "no longer Christians" and warranted forced removals. The Group Areas Act was forcefully applied in 1955 after black Christians who lived on the farm for the whole of their lives were denied permits in terms of section 14(1) of the Act to stay on the farm in Kranspoort. The families who were vocal and resisted the white rule were declared excess families and were ordered to leave the farm with immediate effect (Land Claim Commission Report No 201/1997:3). Families who were compliant with the missionary rules were issued with permits that would expire after two years. It was during this time that the provisions of the Native Trust and Land Act (No. 18 of 1936) were evoked to declare people who lived on the Kranspoort Mission Station as squatters (Ibid).

Squatters were black people who lived on white farms without permits and were unemployed. A farmer would conveniently dismiss black workers from work and deny them permits in order to render them squatters and effectively make them liable for arrest in terms of the Squatter Act of 1952 (No. 52 of 1951). In terms of section 32 of the same Act, all squatters who continuously lived on the land since 31 August 1936 should have been registered and a license fee for each squatter should have been paid by the owner. If the farm owner stopped paying the required license fee, the squatters were declared illegal and they had to leave the farm. The same procedure was followed with regards to the church members of Kranspoort in 1955. However, there were other circumstances where squatters were not effectively dealt with and fell through the cracks. Consequently, Proclamation No. 244 of 1957 was promulgated whereby the payment of license fees was suspended in respect of any black person residing on any land held by a missionary society (Ibid). It was finally decided in 1960, as a general policy, that people on the mission stations in "white areas" were no longer allowed to remain on farms in the so-called white areas but would be resettled in black reserves (Ibid).

Correspondence between the DRC mission authorities and government officials on the matter of forced removals during the period 1954-1960 at Kranspoort reveals unprecedented church and state collusion (DIV 2407). Letters from missionaries and responses from the state officials reveal a common purpose and agenda between the two groups. The DRC missionaries needed the state to help them to remove excess people who were initially recruited to join the Christian faith and had then become "no longer Christians" because of their political hostility. As the black resistance against separate development intensified in the country, it spilled onto the mission stations. The letter written by Rev JHM Stofberg on 8 March 1954 to the Secretary of Natives Affairs and the response of the Secretary of the Natives Affairs sheds more light on the collusion the church and state had on the question of squatters. Squatters received no sympathy either from the church or the state. In the letter, Rev. Stofberg raised four questions concerning the forced removals of squatters from the Kranspoort farm. These questions are discussed next.

a) In the first question Rev Stofberg expressed doubt as to whether the church had the right to evict squatters because, according to him, the Squatters Act No. 21 of 1895 (first passed in the Free State Republic) (DIV 2408) stated that no person other than the state could do so. The Secretary of Natives Affairs responded by reassuring the church that the 1895 Act specifies that the farm owner was entitled to give only five families Permission To Occupy (PTO) and such squatters should be in his employment (Letter dated 8/3/1954 DIV 2408). Natives could only live at places approved by the government, such as reserves, and an application to the Volksraad (Parliament) should be made if natives wanted to live in another area. As the Kranspoort wanted to get rid of excess people, they could do so without hesitation, according to the Secretary of Native Affairs (Ibid).

b) The second question concerned the legality of action against black people who had stayed on the two farms of Kranspoort and Bethesda for a very long period without permits. According to the church, it would not be reasonable to remove them after staying there for so long a time. The answer from the Secretary of Natives Affairs was that legislations that came after 1950 had overriding effect over the practices which occurred there before (DIV 2407).

c) The third question was whether the missionary society had the right to hire natives who lived on the mission farm. This question had far-reaching implications for the church, hence it had an elaborate answer. Article one of the Land Act No. 27 of 1913 was quoted by the Secretary of the Natives Affairs as prohibiting the appointment of natives by a white person on the white land without expressed permission from the Governor-General. But this condition did not include missionary societies who occupied land for the purposes of education and missionary work (Letter dated 8/3/1954 DIV 2407). The Governor-General had given exemption to missionary societies on 8 April 1915. But according to the Secretary of Native Affairs, the people living on mission ground had rental contracts that expired in 1924. For Kranspoort and Bethesda, the natives who were living there for the period 1924 to 1955 (a period of 31 years), even if the provision of the Land Act of 1936 was not observed, were there without the permission of the Governor-General and thus lived there illegally. The situation was further drastically changed with the introduction of the Group Areas Act, No. 41 of 1950, which became effective from 30 March 1951 (DIV 2407). From 30 March 1951, the permit system was introduced and it affected all natives who were on white ground, including mission stations. The status of the inhabitants of Kranspoort had changed and they could be treated as squatters living on other white farmers' land.

d) The fourth question was whether the church (mission) had the right to remove the natives from the farm who disobeyed the bylaws drawn by the church. The answer to this question was that the church had the right to cancel the contract which was subject to obedience to the bylaws after the expiry date. But in the case of Bethesda and Kranspoort, the natives that refused to vacate the land after the expiry of their contract could be removed through court order. It was also possible that the Governor-General might make proclamation in terms of article (2) of the Act of 1951, Act No. 52 of 1951, to remove them. The church had the same rights as ordinary white farmers to remove excess people by obtaining a court order from the civil court. Furthermore, the natives that refused to vacate the land after the expiry of their permission might be prosecuted in terms of the provisions of the Group Areas Act, No. 41 of 1950. This advice from the government was accepted by the DRC and implemented ruthlessly.

On 22 September 1955, the local missionary at Kranspoort wrote a letter to the Chief Natives Affairs Commissioner reporting that inhabitants of 157 families had taken up a serious riotous attitude and that they should be ordered to make their own arrangements for resettlement outside the mission area to black areas (Letter dated 22/9/1954 in DIV 2407). This was taking place although the Mission Secretary Rev. J.H.M Stofberg had earlier written a letter to the Secretary of Natives Affairs expressing doubt as to whether they, as a church, could take steps to remove about 200 squatters (157 families) from the Kranspoort farm (Ibid). Rev. Lukas van der Merwe, the local missionary, wrote another letter to the Chief Natives Affairs Commissioner dated 9 September 1955, in which he complained about the "natives" on the farm of Kranspoort who refused to leave the area even though their "trekpas" was expiring on 13 September 1955 (Letter dated 9/9/1955 in DIV 2407). He further warned the government that if drastic steps were not taken against the "squatters" in terms of the Squatter Act of 1952 (Act No. 52 of 1951), then a wrong precedent would not only be created for Kranspoort but also for other mission stations elsewhere (Ibid).

Of the two, the Mission Secretary Rev. Stofberg and local missionary Rev Van der Merwe, Rev Van der Merwe seemed more forceful in his actions. He wrote straight to the government officials, ignoring his mission secretary. On 9 September 1954, the Secretary of Native Affairs wrote to the Native Affairs Commissioner of the Northern Transvaal informing him about the letter received from the local missionary Rev. van der Merwe as well as a telephonic conversation he had had with van der Merwe. In the letter, the Secretary of Natives Affairs further informs the Native Affairs Commissioner that legal steps were instituted against the squatters who were refusing to leave the Kranspoort mission station.

Later, Rev Stofberg wrote to both the Natives Affairs Commissioner and the Secretary for Natives Affairs enquiring about the legality of the contemplated action, as was the case in his letters of 25 April 1955 and 8 March 1954 (DIV 2408), as he was the last line of communication between himself and the church. In his letter of 25 April 1955, Rev Stofberg enquired (on behalf of the Mission Commission) from the Secretary of Natives Affairs whether 200 squatters who were not issued with permits should be given notices to leave the area. He further requested the Department of Natives Affairs to act urgently. He also suggested that it was only the Department of Natives Affairs, through the Chief Natives Commissioner, that could remove squatters to trust grounds, reserves or native townships. Rev. Stofberg further indicated that the situation at Kranspoort was intolerable and earnestly requested the department to remove the excess people immediately (Ibid).

The affected residents of Kranspoort tried to take the matter to court through their attorneys (Letter from Bernard Melman & Co DIV 2408), but because of the Natives Act, No. 64 of 1956, which deprived Africans of the right to court protection against apartheid laws, they could not. As they could not approach civil courts for protection, their lawyers pleaded with the Native Affairs Commissioner that they be settled in native reserves at Mara, Senthumule location or Molebo (DIV 2407) as they refused to be settled on white farms as labourers. For many black people, to be stationed on white farms as labourers was a worse denigration than they could imagine. According to the Chief Natives Commissioner (Letter to the Secretary of Natives Affairs dated 3rd June 1955 DIV 2407), the excess people from Kranspoort could be sent to Senthumule and Khotama Townships, although the farmers in the Levubu area were prepared to take them all as squatters. The residents were not prepared to go to white farmers as squatters because that would mean further humiliation. Finally, they were chased from Kranspoort by the police. Some fled to their relatives in Gauteng while others went to the neighbouring township in the current Limpopo Province.

After the dispersion of black Christians who were regarded as 'no longer Christians' because of their political convictions from the "Stasie", the black people who were regarded as 'heathens' and were residing on the sections of Kranspoort called "Oorkant" and "Patmos" were invited to come and settle in the "Stasie" because they were politically 'correct' according to Serumula. In 1964, the rest of the people who came to settle at the 'Stasie' were removed in terms of the Group Areas Act of 1950. Unlike their predecessors, their houses were evaluated and compensated for by the government.

3.Observation and summary

The removal of black Christians from Kranspoort in 1957 dealt a severe blow to the credibility of the Mission Policy of the DRC in the Northern Transvaal of that time. There was no basis for the 157 families to be declared squatters after staying on the farm as "converts of the DRC" for more than one hundred years unless the Mission Policy was highly diabolical. Dr JP Theron made an overview history of missionary work at Kranspoort in February 1990 in which he indicated that from January to April 1877 about 90 black people came to repentance in the area. In the following year, 1878, 62 adults and 52 children were baptised adding up to 244 adults and 195 children baptised (Theron 1990:73-104 in DIV 2408).

One can thus conclude that the mission policy served two purposes for the DRC and the Afrikaner government. For the DRC, the troublemakers were removed from the 'Stasie' and replaced with law-abiding 'squatters' and for the government the ideal of the Group Areas Act of 1950 was implemented when those 'black spots' within the white areas were removed. The ambivalence arises from the fact that the DRC had abandoned the original purpose for which the land was acquired - for exclusive missionary work for political expediency. On 27 April 1955, the mission secretary of the Northern Transvaal wrote to the Secretary of Native Affairs about 157 families on the mission farm in Kranspoort who did not have permits. The mission secretary wanted the families to be removed even though they had stayed on the farm since 1863 as Christians when the mission station was started. The government was in agreement with the DRC that blacks living on mission stations within the white areas had to be removed to the black reserves. The greatest problem they faced was removing the squatters, placing them and supporting them in their new localities (DIV 2407). Where there was resistance on the part of black people to comply with desired white decision, force had to be used.

4.Confrontation of 1953-1957 at Kranspoort Mission Station: A case study

The swelling anger that led to the real confrontation between the residents of Kranspoort and the missionary station came forth in 1953. Ramphele (2013:49) puts it as follows: "The high-handedness of this man eventually led to a mass expulsion of two-thirds of the mission villagers between 1955 and 1956". The episode was the product of local and national grievances of mass resistance movements in the 1950s. Although these events should have made the DRC realise that its mission policy was not palatable with political developments in the country, the church stood side by side with the government to implement apartheid. The mission policy eventually led to an open rebellion at Kranspoort. The Defiance Campaign of the 1950s, the Kliptown Congress of the People in 1955, the anti-pass campaign of the 1950s, the ANC women's march of 1956 to the Union Buildings, and James "Sofasonke" Mpanza and many other's protests in the country were 'mushrooming' everywhere and helped to ignite the open confrontation at the DRC Mission Station (Ramphele 2013:49).

The grievances about the allocation of pieces of land, irrigation water, burial rights within the mission station and the suppression of African traditional practices were some of the causes of the conflict. According to Malunga (1986:50), Ramphele (2013:49), Malan (1973:79-81) and Serumula (an informant), the open confrontation started with the death of a woman called Thibego Leshiba. The woman was the mother-in-law of Joseph Matseba who was residing at Kranspoort and working at Messina. When Joseph Matseba let his mother-in-law, Leshiba, come and stay with his family at Kranspoort, he did not comply with the regulation that all strangers coming to the mission station should be reported to the church council (Malunga 1986:50). Thibego Leshiba was coming from a neighbouring farm and her body could not be returned to the farm of her origin because the road was impassable, steep and rocky (Segooa in Malan 1973:79).

After convincing the missionary that the deceased woman should be buried at Kranspoort because of the difficulties of taking her body to her farm of origin, the argument started with the church council that her host, Joseph Matseba, was in arrear with his church contributions (Malan 1973:79). Because her host was not in good standing with the church, she could not be buried at the station. Open confrontation ensued where the residents of Kranspoort defied the by-laws of the station and buried the deceased in the designated area for Christians and missionaries (Segooa in Malan 1973:81). The mob issued a warning that the village council chairperson Nathaniel Sebat, Evangelist Walther Segooa and the missionary Lukas van der Merwe should not come to the graveside as they would be killed. The missionaries felt humiliated by the defiance and called the police (Serumula- informant). The police came but they could not arrest anybody as there was no incident of crime. The crowd shouted "take van der Merwe, Segooa and Sebati away [and] peace would be restored" (Segooa in Malan 1973:83).

Shortly after the burial of Leshiba there was another death case (Segooa in Malan 1973:80). When the church council heard about the death they went to the family to comfort them, but the people who were in the house refused their prayers. The relations were so poor that the residents called Lukas van der Merwe 'Satan' and said that they did not want to be prayed for by "Satan" (DIV2406:102-110). Eventually, the whole group started shouting the earlier demands made at the previous burial: "Away with Van der Merwe, Segooa and Sebati" (Segooa in Malan 1973:81).

After the two death cases, the residents of Kranspoort issued a petition to the DRC Mission Secretary, Rev JBC Stofberg, in which they complained about Van der Merwe, Segooa and Sebati. Two commissions of enquiry were appointed and the church council was suspended and reinstated after the enquiry. The commission tried to bring reconciliation but the residents would not accept the "trio" back. Court cases ensued where Van der Merwe and Segooa were summoned by the court (Serumula informant). The complaints of Kranspoort were handled in court but the white magistrate who was handling the case was biased towards Rev. van der Merwe and his camp. At the third sitting, the magistrate ordered that the complainants (aggrieved party) should leave the mission station as they were no longer Christians (Segooa in Malan 1973:87). According to the magistrate, the mission station was meant for Christians. These were early warnings that the Group Areas Act of 1950 would be evoked and would declare the area white and remove the blacks from it. Such moves also revealed what the DRC Mission Policy stood for. Those who resisted the policy because of its evil agenda were labelled 'not Christians' and they would not be tolerated on the "Stasie". Subsequently, the Ba-Sofasonke group was forcefully removed from the mission station because they were "no longer Christians".

The 75 families who were not removed from the Kranspoort mission station in 1957 were said to be loyal to the authorities and did not take part in the riots of 1955-1957. According to memorandum 4/447(2) submitted to the Department of the Natives Affairs by the squatters controlling officer at Kranspoort, they had built a new church building at the Khutama location outside Louis Trichardt (DIV 2407) for excess people on Kranspoort.

5.Mission in a different gear

After the closure of the Kranspoort 'Stasie' and relocation of the last group which remained after the forced removals of 1957, new "mission stations" were established in black areas. According to the report submitted to the mission secretary on 22 March 1965 (DIV 83), the following congregations that formed the Presbytery of Kranspoort were established: Tshilidzini, the next white area in Levubu; Nthume near the current town of Sibase; Messina, in the black township of Nancefield; Bethesda; Soekmekaar; Turfloop; Letaba; Nkhensani; Lebone; Meetse-a-bophelo; Pietersburg and Kranspoort (Ibid). The Nationalist Government and the DRC dovetailed closely to develop and support a mission policy that would completely restructure South Africa to be totally under the tutelage of "grand" apartheid where various ethnic groups would have their own homelands. The same policy of separateness heavily influenced the Mission Board in 1963 when the Mission Church (black) had to get a new name. The meeting decided to divide it into ethnic groups and name them Xhosa, Zulu or Sotho Dutch Reformed Churches to mirror the principles of the grand apartheid (Minutes of Mission Board SIN 2503 & SIN 733). The name "Dutch Reformed Church in Africa" was eventually adopted by black delegates when they became an autonomous church in 1963 (Ibid). The white DRC had so much power over the black autonomous church that when the "mother church" made decisions, these decisions were forced on the "daughter church" (SIN 2503).

The Dutch Reformed Church Mission work in the current Limpopo was not always coordinated and controlled from one central office. As the government was also a party to missionary work among black people for the purposes of introducing black homelands and separate development, it had a separate agenda from that of the official church (Smith 1994: np). The forced removals of 157 families from Kranspoort in 1957 did not have direct bearing on the developments of the late 1950s when other mission stations were established in Vendaland and the Lowveld of the Transvaal of the time.

In his monograph first written in 1963 and revised in 1994, Nico Smith illustrates another path the DRC mission took in Venda that was ideologically related to the events at Kranspoort, even though the role players were not often aware of each other's intentions and presence in the area. Smith, who became a pioneering missionary to Venda in 1956, states in his monograph that although he was sent to Venda under the direct assistance by Verwoerd, Rev. Lukas van der Merwe of Kranspoort (some 60 km west of where Smith was stationed) did not welcome Smith in the area (Smith 1994:np). Van der Merwe was very angry with Smith's coming into the area and regarded it as transgression onto his terrain without previous consultation. The two worked for the same ideology but the right hand did not know what the left hand was doing.

Moved by the ideology of separateness and directly inspired by the Tomlinson Commission Report of 1956, many white missionaries gave their lives for mission work to remote areas of the country (Saayman 2008:47). The Tomlinson Commission was appointed by the National Party government to investigate all aspects of Bantu homelands with a view of developing them to form their own homelands for the various ethnic groups (Smith 1994: np). The commission came up with startling statistics, especially on the status of Christianity in South Africa. According to the commission's report, only 10% of homeland inhabitants were Christianised (Smith 1994: np). The report further indicated skewed mission statistics of the DRC, Roman Catholic Church and other Protestant churches. The DRC was not doing well when compared with other churches (Saayman 2008:23). At a meeting in June 1956 in Bloemfontein to discuss the Tomlinson Report, the DRC decided to accept the challenges posed by the commission to send as many missionaries as possible to homelands to go and evangelise black people, the results of which held favour for the white Afrikaners on the questions of having favour with God to fulfil their calling as the "chosen" nation of Africa (Minutes of Mission Board 1939-1973 in SIN 220).

By 1960, the DRC had established the following mission stations in Venda and the Lowveld: Tshilidzini (Nico Smith 1956), Nthume (Willem Louw 1958), and Sibasa (Mauritz van den Heever 1959) in Smith 1963).

Further south-east of Sibasa (Venda), in the area of the Shangaans, the DRC sent missionaries to fulfil the demands raised by the Tomlinson Report and the church to establish homelands among various ethnic groups in South Africa (Smith 1994:np; Kgatla 1988:46). In 1956, Rev DCS van der Merwe was inducted in Giyani as the first missionary in the area (Crafford 1982:349). In May 1959, E Bruwer was inducted in the vicinity of Giyani called Nkhensani. Other outposts which were looked after by black evangelists included Makhuva and Shingwedzi. Further down south, CWH Boshoff, the son-in-law of Dr HF Verwoerd established himself in Bushbuckridge in August 1956. In this period, the mission work of the DRC spread to the west in the area of Polokwane (Pietersburg), Mokopane (Potgietersrus) and south to Sekhukhuneland (Lydenburg). The DRC mission strategy included building hospitals. From 1939 to 1960 ten hospitals were built in the area (Kgatla 1988:51).

6.Concluding summary

The problem of the Kranspoort residents became a serious nightmare for the DRC mission strategists. They never expected that there would be black people who would resist their mission policy of denial of black rights, oppression and that which perpetuated white dominance over black people. By definition, black people who resisted the policy of apartheid could not be said to be Christian. Christianity was defined in terms of total surrender of black people to white rule and direction. This is evident from the correspondence the mission authorities had with their counterparts in government. Correspondence between the Mission Secretary of the time, Rev JHM Stofberg and Rev Lukas van der Merwe, and the Regional Liaison Commissioner and Secretary of Native Affairs shows the collusion and convergence of the policies of the DRC and the government. The forced compliance with the apartheid policy on the side of the black people was not negotiable.

Apartheid as an ideology of self-interest and white protection was entrenched in the DRC to the extent that the DRC could not separate what was purely evil from Christian love. The church could not read the signs of time and remove brutal elements from its mission policy. Smith (1994) alludes that the pious outlook to mission within the DRC leadership at the time was a dose that blinded the Afrikaner missionaries. The zeal to convert the "heathens" undergirded by a condescending attitude shaped the DRC mission policy without realising that the ideology of apartheid had a firm grip on their minds. Part of the missionary outreach was to convince black people that the policy of separate development was designed to serve their interest whereas the main objective was to safeguard exclusive white interest. When African National Congress Leaders such as Dr Xuma warned that there was no way that one nation could work in the best interest of another without involving it. Dr Alfred Xuma in SAHO. [Accessed: 23/3/2015] They were simply ignored.

The challenges posed by the Kranspoort black Christians revealed the weakness of the DRC Mission Policy and their motives for mission. One could hardly differentiate between church mission policy and government agenda. The apartheid policy, with its strong religious underpinnings, succeeded in motivating its people to interpret it as God's calling (Smith 1994: np). Missionary programmes such as health, religious education and economic development were invariably subsidised by the government, an indication that they were part of the government agenda for the development of homeland policies (Ibid).

Bibliography

Badat, S 2012. Political banishment under the forgotten people. Auckland: Jacana. [ Links ]

Changuion, L & Steenkamp, B 2012. Disputed land: The historical development of the South African Land Issue, 1652-2011. Pretoria: Protea. [ Links ]

Cousins, B & Walker, C (Eds). 2015. Land divided, land restored, land reform in South Africa for the 21st century. Auckland: Jacana. [ Links ]

Crafford, D 1982. Aan God die dank. Deel 1. Pretoria: NG Kerk boekhandel. [ Links ]

Giliomee, H 2003. The Afrikaners' biography of people. Cape Town: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Giliomee, H 2012. Die laaste Afrikanerleiers: 'n Opperste toets van mag. Pretoria: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Horner, D. 2011. When missions shape the mission. You and your church can reach the world. Nashville, TN: B&H. [ Links ]

Johnson, WR 1994. Dismantling apartheid: A South African town in transition. London: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Kgatla, ST 1988. Dutch Reformed Church Mission in the Northern Transvaal, 1865-1964: A critical evaluation of motives, goals and methods. Unpublished M.TH Dissertation submitted to UNISA. [ Links ]

Kgatla, ST 2013. Forced removals and migration: a theology of resistance and liberation in South Africa. Missionalia, 41(2) 2013. [ Links ]

Letter from Bernard Melman & Co in DIV 2408 DRC Archives Stellenbosch.

Malan, FS 1973. "Die lewe en werk van evangelis Walther Ramokone Segooa van Kranspoort". Stofberg Teologiese Skool, 3(1):62-95. [ Links ]

Malunga, WF 1986. A Century of the Dutch Reformed Church Missionary Enterprise in Soutpansberg Area - the story of Kranspoort: M.A. dissertation submitted at the University of the North. [ Links ]

Mbali, Z 1987. The churches and racism: Black South African missionaries. Pretoria: Protea. [ Links ]

Minutes of Mission Board, SIN 220 1939-1973. DRC Archives Stellenbosch.

Moeng, MW 2015. The History of RITA-Noemnoemdraai - Bethesda. UNPUBLISHED PAPER Read on 13 May 2015 Limpopo Province.

Mohlamme, A nd. In The SPP Reports. Forced removals in South Africa, Vol. 1, 2, 3, 4. Theology of Mission. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis.

Morris, M 1990. Apartheid: An illustrated history. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball. [ Links ]

Murray, C & O'Regan, C 1986. 'No place to rest: forced removals and the law in South Africa'. Journal of South African Studies 19(3), 539-541. [ Links ]

Ramphele, M 2013. A passion for freedom. Cape Town: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Saayman, WA 2008. Being missionary being human: An overview of Dutch Reformed Ministry. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. [ Links ]

Smith, NJ 1994. Tshilidzini: Christian missionary work in an apartheid context. Unpublished autography of Dr. Nico Smith.

The SPP and AFRA. 1984. Removals and the law: The missionary history of South Africa. Pretoria University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

The SPP and AFRA. 1984. Removals and the law: the South African Land Issue, 1652-2011. Pretoria: Protea. [ Links ]

The SPP Reports. Forced removals in South Africa, Vol. 1, 2, 3, 4. Theology of Mission. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis. [ Links ]

Van Aswegen, H.F 1990. History of South Africa to 1854. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Van Donk, M 1994. Land and the church: The case of the Dutch Reformed Churches. Cape Town: Western Province Council of Churches. [ Links ]

Worden, G 2012. The making of modern South Africa. Western Sussex: Southern Gate. [ Links ]

Files from Dutch Reformed Church Mission Archives at the University of Stellenbosch:

DIV 39 DRC Anniversary Report

DIV 55 Kranspoort Diverse Collections

DIV 83 General Correspondence

DIV 84 Correspondence between Hofmeyr's and DRC

DIV 85 Diverse Correspondence

DIV 86 Heirs of Stephanus Hofmeyr

DIV 552 Minutes of Presbytery of Kranspoort

DIV 1910 Correspondence between Hofmeyr's and DRC

DIV 2405 Correspondence and Court Judgments

DIV 2406 Court Records

DIV 2407 DRC and Government Correspondence

DIV 2408 Court Papers: Hofmeyr Farm School Afrikaner fears and Politics of Despair: South African History. [Online] www.sahistory.org.za [Accessed: 2/6/2015]

The Afrikaner Rebellion: South African History.[Online] www.sahistory.org.za [Accessed 1/5/2015]