Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.9 no.3 Cape Town Set./Dez. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.14426/ahmr.v9i3.1168

ARTICLES

Protection of the Rights of Ethiopian and DRC Refugees and Asylum Seekers: Examining the Role of South African NGOs (2005-2017)

Meron Okbandrias

School of Government, University of the Western Cape, South Africa. mokbandrias@uwc.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The South African asylum system has gone through a dynamic change over the last twenty years and NGOs have been a permanent feature of the system starting from the crafting of the Refugees Act. Over the last decade, the flow of asylum seekers has slowed, but the country still hosts a significant number of African and Asian asylum seekers and refugees. As a result of the many factors, asylum seekers and refugees face a multitude of challenges. Some of the challenges include inefficient public service, a corrupt system, xenophobia, and other challenges. NGOs have championed the rights of asylum seekers and refugees. This paper looks at the work that has been done by NGOs working in the protection of the rights of asylum seekers and refugees from 2005 to 2017, utilizing the case study of the 40 Ethiopian and 37 Democratic Republic of the Congo nationals residing in Johannesburg and Durban through interviews. The researcher collected additional primary data from selected NGOs and analyzed both data sets through descriptive statistics. The findings indicate that NGOs have their areas of speciality, and their roles has changed over the course of the 12 years from being cooperative with state actors to mostly a combative role to ensure and protect the rights of asylum seekers and refugees. Their effectiveness has also been impacted as a result, and litigation has not always been effective. Asylum seekers and refugees find NGOs effective to a certain extent, but a significant number of them are not aware of NGOs or the work they do.

Keywords: Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, refugees, asylum seekers, NGOs, South Africa, rights

INTRODUCTION

There is no doubt that the issues surrounding asylum seekers and refugees in a twenty-first-century context (more especially within South Africa) are extremely relevant considering the dynamic nature of this area in international relations and the steady flow of migrants into the country. In the last 25 years, and in particular after the country's democratic transition, this field has seen major legislative changes and faced many challenges. Of particular concern are the continuous incidences of xenophobia in their covert and overt forms, especially the 2008 and 2015 xenophobic attacks. The Department of Home Affairs (DHA), plagued by chronic corruption, is mismanaging the process of implementing the country's Refugees Act (No. 130 of 1998), with some asylum seekers stuck in the process for over 10 years.

Despite the constitutional and legislative protection guaranteeing the rights of asylum seekers and refugees, government assurance, a robust judicial system, and civil society activism, it remains a hugely challenging environment. For instance, the South African government's Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) control efforts, which included a national lockdown, exacerbated the country's systemic discrimination against asylum seekers and refugees. It is well-demonstrated in the South African government's failure to include this disadvantaged group in economic-, poverty-, and hunger-reduction programs, which caused these individuals to develop poor coping mechanisms, resulting in mental health disorders and secondary-health problems (Mukumbang et al., 2020). These challenges can be explained and articulated on many levels. On the one hand, there is the continuing challenge to the universally guaranteed rights of refugees and asylum seekers, especially in South Africa (United Nations, 2011; Kavuro, 2016). On the other hand, there are structural socio-economic factors that become real or perceived reasons for begrudging migrants, especially those from the rest of Africa (Ngwenya et al., 2018; UNCTAD, 2018; Bjarnesen and Turner, 2020).

The question of why one should focus on the rights of refugees and asylum seekers in a study, when there are many other marginalized sectors of South African society, is a critical one. After all, South Africans suffer with similar problems like accessing social services and other problems. However, it becomes necessary to engage in a study around this community given that the ability of refugees and asylum seekers to claim substantive rights while residing in South Africa is limited, despite the national legislative framework granting them certain rights (Kavuro, 2016; Nicholson and Kumin, 2017; Mukumbang et al., 2020; Moyo and Botha, 2022; Rugunanan and Xulu-Gama, 2022). This state of affairs poses a unique challenge for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) advocating for their rights and monitoring the implementation of policies and processes that are meant to benefit them.

This research explores whether NGOs in the refugee sector assist refugees and asylum seekers in South Africa to claim their rights in a substantive manner. Furthermore, it examines how effective the NGOs are in accessing their rights according to South African and international law.

ROLE OF NGOS IN PROTECTING THE RIGHTS OF REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS

According to Cameron (2000), NGOs as civil-society institutions negotiate with market and state agents to ensure their sustainability and in so doing, increase the certainty of livelihoods for the most vulnerable. In this instance, the most vulnerable are refugees and asylum seekers. NGOs undertake three roles: as implementers, catalysts, and partners (Lewis, 2006). In South Africa, the civic-state engagement can be categorized in three ways (Handmaker, 2009):

• Participatory engagement: Civic societies, such as Lawyers for Human Rights (LHR), participated in the government-driven process of drafting refugee policy. This (sometimes confrontational) cooperation occurred from 1996 to 1998 and culminated in the drafting of the 1998 Refugees Act. It was a two-track process in which civil society discussions fed into the government-led process. The LHR brought its legal and civic expertise in human rights protection to the discussion and the drafting of the legislation.

• Cooperative interaction: There are instances when international and local civil society engage with the South African government; for example, in efforts to regularize the residential status of Mozambican refugees. South Africa hosted hundreds of thousands of Mozambican refugees, some of whom were repatriated with the help of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), while others were deported or remained in the country without legal documentation. During 1999 and 2000, civil society made a significant contribution to legalizing their stay.

• Confrontational engagement: Civic advocacy holds the state accountable by taking legal action to challenge the state's decisions and to ensure that the government complies with constitutional and administrative law. The state has previously been challenged by many NGOs on refugees and asylum seekers' access to social services, fair procedure in status determination, and unfair detention and deportation. Confrontational civic advocacy has also been directed at non-state actors. A case in point was the confrontational advocacy against financial institutions regarding refugees and asylum seekers' access to banking.

Since the establishment of the UNHCR in 1950, there has been an acute awareness and focus on the rights of refugees as a specific category of vulnerable people. However, there is no historical evidence of the presence of NGOs specifically dealing with refugees, before the existence of the UNHCR and its predecessor, the International Refugee Organization (IRO). The international protection of the majority of the world's refugees has traditionally been in the domain of the UNHCR. Since the 1980s, NGOs with a refugee protection and assistance mandate started to emerge. That was partly because of their dissatisfaction with the role of the UNHCR, which was magnified in the mid-1990s during the genocide in Zaire, Tanzania, and Rwanda. According to Van Mierop (2004):

Humanitarian NGOs publicly questioned how UNHCR could execute its mandate in such a situation. Several of them published reports or made public statements in which they denounced violations of the rights of Rwandan refugees, and there were even a few NGOs that left the camps in Tanzania and Zaire.

Since the end of the 1990s, the role of NGOs in South Africa has increased from participation in the drafting of the Refugees Act of 1998 to litigation on behalf of asylum seekers and refugees (Nicholson and Kumin, 2017). The role of NGOs has never been more magnified than during the xenophobic attacks of 2008 and 2015 (Maharaj, 2009; Robins, 2009; Mantzaris and Ngcamu, 2021). To understand the dynamics of xenophobia in South Africa, we need to consider the economic and social processes that result in uneven capital accumulation patterns within and between the local Black populations and African immigrants, as outlined in Amisi et al. (2011). Xenophobia arises under conditions of economic stresses (Amisi et al., 2011). South Africa has been experiencing some of the world's worst economic disorders and inequality since the end of apartheid and is currently ranked as the world's most unequal country (Chutel and Kopf, 2018; Beaubien, 2019;). This was brought about by rising inequality, measured by the country's increasing Gini coefficients (from .66 in 1994 to .70 in 2008), resulting in far higher unemployment (from 16% in 1994 to 20% in 2010) and worsening urban poverty (Frye et al., 2011). During those severe economic periods, the locals struggled to sell their products within a strong competitive environment; thus, they jealously protected production processes. In 2008 and in 2015, the world watched in horror as South Africans turned against immigrants from other parts of the continent, killing, raping, and leaving tens of thousands homeless (Everatt, 2011; Nwakunor and Nwanne, 2018; Mantzaris and Ngcamu, 2021).

In response to the xenophobic violence, civil society organizations (CSOs) played a critical role in organizing resources and influencing public opinion, while state agencies seemed unable to respond to this crisis, either at scale or at appropriate speed. According to Everatt (2011), civil society appeared with flexible, innovative, and creative structures to reinforce social justice networks for immigrants. The immediate response from various NGOs when the violence began in May 2008 was their call for more civic "education," usually about human rights, the plight of refugees, and the role that neighboring societies played in hosting South African exiles during the apartheid era (Amit, 2011). There is an absence of more considerable government and political enthusiasm in relation to the protection of refugees' rights in the South African landscape. Nevertheless, there has been a high degree of civil society empathy for the conditions refugees find themselves in, within the context of social rights in South Africa (Misago et al., 2015).

The South African government has chosen to deny reality to avoid dealing with an uncomfortable truth. According to Crush (2008), the South African constitution has been extensively praised as being among the most progressive and inclusive in the world in protecting citizens' rights. However, it is clear that these rights do not extend to everyone living in the boundaries of the nation-state. Two sets of rights are deliberately reserved for South African citizens: (a) the right to vote; (b) the right to engage in freedom of trade, occupation, and profession (Crush, 2001); the latter has been successfully challenged in court. One thus assumes that all other rights should be extended to "all persons" in the country.

For that reason, the role of civil society organizations in relation to refugee rights has been substantial. Noteworthy are the UNHCR and other donors who sponsored national NGOs that acted as a lobby groups for refugees, supported each individual case, and attempted to oppose xenophobia through various channels (Amisi et al., 2011). Civil society also supported a variety of NGOs and service providers with temporary accommodation and basic food supplies for refugees, to protect their right to dignity. The constitution also states that all persons in the country have the right to shelter and access to food. However, there were challenges in attempts to bring together service providers and refugee communities, especially as this related to the power of South African-dominated NGOs, which did not serve the interests of refugees' rights.

The Refugees Act of 1998 states that refugees are allowed to seek employment and to have access to education. However, in this piece of legislation, nothing is explicitly said about refugees' rights to access other basic services such as housing, water, sanitation, and safety (Palmary, 2002; Solomon and Haigh, 2009). This resulted in many of these rights being met through service delivery by civil society. The role of civil society in protecting refugees' rights is not adequately acknowledged either by the Refugees Act or in any policy documents. Nevertheless, civil society continues to play a major role in protecting, lobbying and advocating for refugees' rights (Milner and Klassen, 2020). The refugee regime in South Africa has undergone significant changes in the last six years, notably its transition in terms of the different legislation that govern the regime, and the public and political elites' focus on this regime. As a result, the extent and nature of NGOs that work actively in this area, have also changed.

The focus and urgency that gripped this sector after the 2008 and 2015 xenophobic attacks have subsided but were replaced by a degree of apathy, despite the occasional flare-ups of xenophobic attacks. Recently, the activities of the vigilante group, Operation Dudula and the provocative utterances by politicians exacerbated xenophobic feelings (Myeni, 2022). In the prevailing environment, the UNHCR continues to be a funder and agenda setter, working in conjunction with those NGOs that assist asylum seekers and refugees (Nicholson and Kumin, 2017).

METHODOLOGY

The researcher employed a qualitative research method to gather data from the two principal sources - refugees and asylum seekers, and NGOs. In the case of the former, this study focused on Ethiopians and Congolese in three cities in South Africa -Johannesburg, Durban, and Cape Town. The researcher conducted structured in-depth interviews with 40 asylum seekers and refugees from Ethiopia and 37 from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to gain a holistic view of their challenges and their interactions with refugee-related NGOs. The study used the snowball sampling technique for all participants.

The researcher derived the second set of data from the interviews conducted with three managers of the NGOs identified for this study - Lawyers for Human Rights (LHR), Refugee Social Services (RSS), and Scalabrini Centre (SC). The researcher identified the three NGOs because of their focus on specific aspects of refugee protection. LHR focuses on advocacy and engagement and serves as a last-resort litigation to protect refugee rights; it has a track record in establishing jurisprudence in refugee law in South Africa. The RSS works on social assistance in the form of material assistance, specifically in access to shelter, education, health, and skills development. The SC plays a similar role in Cape Town and has provided interpretation services for the DHA for about three years; it has also provided refugees with paralegal experience in helping their respective communities in different cities.

The researcher used a case study approach. Zainal (2007) points out that case studies help researchers to access a population where it is difficult to get an adequate sample and analyze data at a micro level in examining social issues. However, a case study can lend itself to generalizing on the basis of concluding from a small sample. This concern might apply to both data sources - refugees and asylum seekers, and NGOs. The two nationalities identified, despite the small sample size, constitute two of the nationalities with the highest number of refugees and asylum seekers in South Africa. The three NGOs are comparatively well known for operating in the refugee sector.

The researcher deemed it fitting that the experiences of asylum seekers, refugees and refugee-related NGOs and their perceptions of the relevant human rights issues can best be recorded and understood, by using a qualitative research methodology. The researcher used the triangulation method by gathering data from different stakeholders from the refugee human rights regime. Regarding asylum seekers and refugees, the data analysis considers to what extent they interact with refugee-related NGOs in their respective cities.

RESULTS

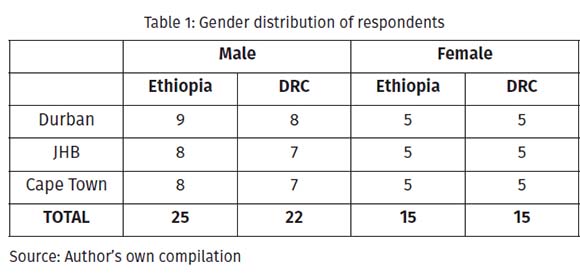

The researcher strove to access respondents with different vocational backgrounds and endeavored to attain a balanced gender (see Table 1) and age mix. Almost 50% of respondents from both countries were asylum seekers, and 50% were refugees. Most of the Ethiopians were self-employed traders; their main livelihood was selling bedding and clothing to township inhabitants. Some were street hawkers, while others owned small business establishments like clothing and spaza shops. A few Ethiopian participants were students. On the other hand, the data indicates that Congolese participants worked primarily in car guarding, while some worked in security services. There were also participants who were studying and working in other areas.

As Table 1 indicates, females constituted 40%-45% of respondents, and there is almost equal distribution of respondents across the three cities.

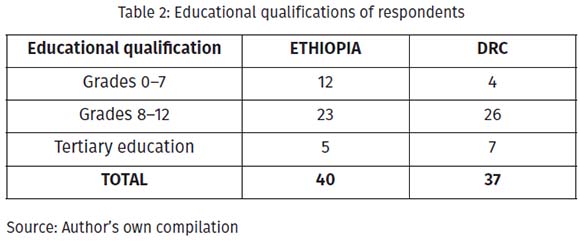

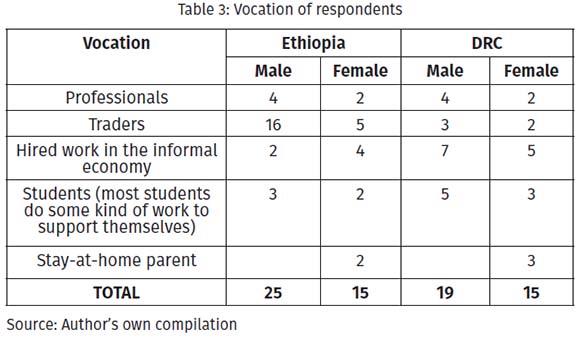

Table 2 indicates that about 21% of respondents attained a school qualification up to Grade 7, about 64% attained a high school qualification, and nearly 16% had tertiary educational qualifications. The DRC respondents had higher academic qualifications compared to the Ethiopians. As depicted in Table 3, most Ethiopians (over 50%) were traders, while only 27% of the DRC respondents were traders. Interestingly, the DRC respondents' vocations were almost evenly spread in all categories. Nearly 30% of respondents indicated that they had a second income source.

The structured interview for the refugees and asylum contained 25 questions. Apart from the demographic information, only three questions were relevant to the topic of this study. These questions were:

• Did you have any difficulty accessing documents like permits, social and financial services (health, social welfare, education, and banking services)?

• To what extent are you familiar with NGOs that assist refugees and their services?

• What services have you received from NGOs (if any)?

DISCUSSION

Asylum seekers and refugees in international law

The last 400 years saw a greater awareness of human rights in Western countries and the world. In the previous 100 years, there was an effort to internalize international liberal rights instruments within the nation-state, as it is the building block of the global system and law. In addition, there was a move to ensure the rights of other nationalities within the nation-state. Ultimately, the liberal rights theories gave rise to the recognition of their rights outside their nation-states. However, this discourse needs to consider the ideas regarding sovereignty and citizenship in nation-states, the subjective interpretation of rights, administrative justice, and political and social forces that determine the implementation of refugee systems. Even NGOs' work in protecting refugees and asylum seekers is located in this context.

Rights cannot be considered outside the context of their implementation. "A State is a legal and political organization with the power to require obedience and loyalty from its citizens" (Seton-Watson, 1977: 36) whereas a nation is a "named human population sharing a historic territory, common myths and historical memories, public culture, a common economy and legal rights and duties for all members" (Smith, 1991: 41). The idea of sovereignty is based on international law. By virtue of sovereignty and their obligations to their subjects, nation-states abide by local and international laws. Nation-states negotiate and sign treaties based on the legitimacy of their sovereignty. Refugees and asylum seekers, therefore, present a problematic reality that the nation-state cannot ignore.

Sovereignty presupposes a solid concept of self-determination with a clear distinction between those who belong and those who do not. It has, however, both a civic foundation, originating from people's self-rule as citizens, and a universal foundation - the universal recognition of people's right to sovereignty. In respect of refugees, however, these two concepts collide because stateless people reveal, qua their existence, the fiction of the right to sovereignty. For a state, this means, on the one hand, that it has an obligation to recognize the refugees' universal right to sovereignty, because the state itself is based on this recognition; but on the other, it can do so only under its sovereign powers, which by definition are limited to citizens. With regard to refugees, a state has to be both a sovereign and a non-sovereign power at the same time, thereby undermining its legitimacy.

The somewhat unique situation of refugees, and especially asylum seekers, creates a problem for the law, since laws are an expression of a nation's will through its elected officials. What is politically unacceptable, despite liberal human right principles, becomes a problem to execute judicially. The current flood of asylum seekers in Europe, and the perception that it has increased incidents of terrorism, creates a unique situation in which politics cannot be reconciled with European laws. NGOs have to operate in such an environment.

In the case of South Africa, the lack of political and public support for large populations of asylum seekers and refugees manifested in xenophobic violence, challenges in accessing social services, and the ruling party's move toward restricting asylum-seeker rights by closing Refugee Reception Offices (RROs) and changing regulations to restrict access to documentation. What used to be a cooperative state where NGOs had a say, became a move toward restricting refugees and asylum seekers.

This raises the issue of the obligation of the state to refugees, and its practical application of obligations. Though the refugee mourns the destruction of the family home, the disintegration of cultural practices, and the loss of communal ties, there is one loss that, according to Hannah Arendt (1973), remains unrecognized: that, as a political being, in a practical sense the refugee ultimately loses the right to have rights. The right to have rights is not so much concerned with substantive rights, such as the abovementioned basic needs, but rather the assumption "that no law exists for [the refugee] ... that nobody wants to ever oppress them" (Arendt, 1973). The refugee becomes existentially transparent. As a political being, the refugee ultimately loses the right to have rights.

There are two reasons why migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers lose the right to have rights. Firstly, by virtue of being the "other," they will not be considered "fit" to have rights. This is reflected not only in laws but also in attitudes, behavior, and practice of people in general. Arendt (1973) points out how Jews, by being a separate unit that formed the "other," became targets. Secondly, Arendt explains that migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers are seen as present without function. In fact, they are seen as parasitic. This perception is partially true in Scandinavian countries, because of their welfare systems. Some citizens are also dependent on social power but unlike the refugees, they have political rights. Arendt (1973) argues that the Jews in Western Europe at the beginning of the twentieth century lost the power they had,1 and wealth without political power was seen as useless and contemptible. Ultimately, presence without function is perceived as useless and parasitic. The reality reveals itself in the case of migrants and refugees whose contribution in economic terms to host countries is tremendous. However, the contribution of the "other" is perceived as not so significant in the political arena, in comparison with that of citizens.

Defenders of refugees and asylum seekers against exclusionary policies mostly invoke liberal universalist arguments to defend refugee rights. Liberal universalist theories are those that give equal moral weight to the welfare of all individuals, regardless of nationality (Boswell, 2017). Liberal universalism provides an accessible and cogent grounding for theories of duties to non-nationals. Liberal universalism's assumptions about the moral equality of human beings pervade moral and political discourse in liberal democratic societies. It is, therefore, not surprising that theories of liberal universalism hold a virtual monopoly in arguments for admitting greater numbers of refugees, and more generally, for the recognition of moral duties beyond borders (Boswell, 2017).

However, as social and economic challenges grow, liberal ideas are tested. In addition, as asylum seekers and refugees consistently interact cheek by jowl with locals in poverty-stricken areas, tensions grow.

Refugees' and asylum seekers' experience with NGOs

The data shows that almost 85% of the respondents had heard of NGOs assisting refugees, either during a particular crisis - such as xenophobia - or in accessing services. Of all respondents, 60% identified the NGOs clearly and only 40% had interacted with the three NGOs that participated in this study. One of the Congolese respondents asserted:

I know a lot about RSS. Because of my work, we send a lot of refugees to RSS to get assistance in housing, education, and skills. They are very helpful. I also know of LHR. They help refugees who have a problem with their papers. They used to be active. Sometimes they help but most times they don't. I don't know of other NGOs. There are also churches that help refugees.

There is a significant difference in the extent to which the DRC and Ethiopian refugees and asylum seekers interacted with NGOs. Only 30% of Ethiopian participants interacted with the NGOs in any meaningful way. They were more likely to depend on familial and community resources. This trend is supported by the data extracted from the NGOs, which indicated that Ethiopian refugees constituted a minority of the communities they serve.

Conversely, almost 70% of the DRC refugees and asylum seekers reported receiving some kind of assistance, including humanitarian assistance, access to documentation, and access to social services like education, health, and banking. The humanitarian services are limited in scope: support in times of crisis; three months' financial support to newcomers; and limited language and skills training. However, during the study period, NGOs frequently provided help in accessing documentation. In addition, access to social services is a fairly common service provided by the three NGOs under study. Among the DRC respondents, 38% reported that they received NGO assistance when they had challenges in enrolling their children in school or were refused services in banks and health facilities. However, 15% of DRC respondents were frustrated because they could not get help from NGOs.

On the other hand, only 20% of Ethiopian respondents reported receiving assistance from NGOs. These services were restricted to seeking assistance to access documentation. This service notwithstanding, they expressed their negative perceptions of NGOs' ability to solve their problems. One Ethiopian asylum seeker lamented:

I don't seek help from NGOs often. I went to LHR because I was told they help people with documentation problems. I have been told I can't renew my asylum-seeker permit because it has been renewed 10 times. It is not my fault that they have not finalized my case in the appeal board. LHR wrote me a letter. The officer in DHA saw it and just put it away. It is really frustrating that the NGOs don't have influence.

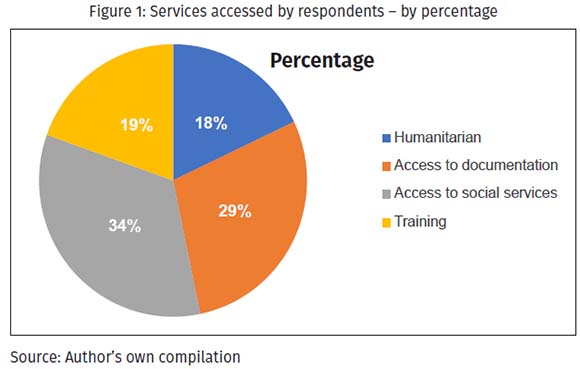

Figure 1 indicates the kind of services refugees and asylum seekers accessed. It is important to some respondents to access multiple services.

It is evident that NGOs in the study (and others) are visible and refugees and asylum seekers know they are accessible. According to the respondents, the NGOs' effectiveness is limited in helping them access services and documentation at an individual level, despite their efforts.

Assessment of the effectiveness of NGOs in the advocacy and protection agenda

The contribution of NGOs in advocating for and protecting refugees and asylum seekers has had a varied history in South Africa. NGOs such as the LHR contributed to the formulation of the Refugees Act (Masuku and Rama, 2020). Considering their comprehensive protection of the rights of refugees and asylum seekers, their contribution to the process has been stellar. However, since circumstances have changed significantly, it warrants a comprehensive analysis of this contribution. The past 15 years have witnessed several developments:

• a significant increase in the numbers of asylum seekers in South Africa (Moyo et al., 2021 et. al);

• the increasingly combative relationship between the DHA and NGOs;

• the closure of three Refugee Reception Offices (RROs) (Majola, 2022); and

• the occurrence of major xenophobic attacks (Dahir, 2019; HRW, 2020).

What makes the NGOs' work of advocacy and protection more important is the absence of the UNHCR. In other countries, in the absence of a policy for the integration of refugees into the local population, the UNHCR steps in to provide advocacy and protection. In South Africa, the role of the UNHCR is that of an enabler - it lobbies for better legislation and implementation of the country's Refugees Act. The UNHCR collaborates with South African NGOs to engage with asylum seekers and refugees, as protection is more productive when one works at the grassroots level and in close liaison with those who need it.

The data and the literature have shown that NGOs have been effective in some respects. They have made it possible for refugees to access social grants (Fajth et al., 2019). The RSS director indicated that her organization was instrumental in enabling refugees to access social grants:

We didn't take that one up to court. We were the ones that were instrumental in taking up the case, why refugee pensioners, those in pensionable age, are not allowed to get a pension. When the case was about to go to court, then the regulation changed.

A combination of litigation and consultation with different stakeholders has brought about certain results. Asylum seekers' right to access employment is an example of this achievement. The three NGOs cited the case studies that they used to negotiate the access of refugees and asylum seekers to education, health services, and other social services. Besides, they constantly work in realizing access to documentation; because a document is a key to other services. Despite these gains, refugee- and asylum-seeker protection is on the back foot. Their rights and ease of access to services are generally worsening, especially when it comes to the DHA, as is the case worldwide (WHO, 2022).

In addition to the DHA's closure of RROs, it has drafted a bill to complicate asylum seekers' entry into and stay in South Africa (Polzer Ngwato, 2010; 2013). Refugees and asylum seekers are also restricted to accessing financial services at only one bank (First National Bank) despite a court decision to the contrary and the existence of an online verification system (Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, 2020). Moreover, the access is erratic and depends on the validity of their asylum permit (sometimes granted for a month) or refugee permit. Ultimately, advocacy and protection have become confrontational. In reality, NGOs are in a peripheral niche that gives them a place to make an input but they have relatively little power to push through the protection agenda.

NGOs are much more effective when they deal with cooperative actors. The three participating NGOs explained that their relationship is largely cooperative and it only works if there is cooperation. However, the relationship is not always cooperative. The LHR's head of Refugee and Migrant Rights Programme explained:

The relationship with the Department of Home Affairs is both good and bad. There is a part of Home Affairs that is willing to cooperate. It is a body which is made up of a number of people. There are certain people within Home Affairs that we have a very, very productive working relationship with. We can refer cases for easy dispute resolution and that sort of thing. At other times, we are forced to litigate against Home Affairs because they would be sort of unwavering on a point, which we thought was not negotiable. The relationship with Home Affairs is complicated. It is generally ... one where we prefer to be engaging, mediating, and negotiating with them. And that is the first port of call. But our second port of call would be to litigate if it becomes necessary.

In fact, the three NGOs have the same kind of relationship with the DHA. However, in general terms, the South African government's approach to refugees and asylum seekers has been rather negative. Handmaker (2009: 156) states that the ability of civil society to hold the government accountable is "structurally conditioned" and "actively informed by specific historical events." This indicates the potential of legal and other forms of civic advocacy to hold states accountable through cooperatives or confrontational interactions within the framework of both national and international institutions. They are especially effective when they have wide public support or when their particular agenda has strong public support.

To put this in perspective, one has to revisit the civic and state environment just after the democratic transition in 1994. With the drafting of the constitution and the dispensation of rights during the mid-1990s, there was an explosion of human rights awareness. In the post-apartheid South African era of identity-based and individual rights, the issue of refugee rights found great sympathy. In such an environment, where civil society was acknowledged as a partner in the anti-apartheid struggle, the civic-state relationship was very good (Gumede, 2018; Levy et al., 2021; FreedomHouse, 2022). As a result, civil society was instrumental in translating the international human rights instruments to local ones in the form of legislation - not only in South Africa, but across the globe (Viljoen, 2009).

Increasingly, however, in the sphere of policymaking, CSOs that could be co-opted, participated, while others were sidelined. As Schneider (2002) and Jansen (2002) critically outline, in the hollow cooperative policymaking processes in the spheres of macroeconomics, AIDS and education, the ANC-led government has increasingly become hawkish at the expense of public and civil-society participation. Therefore, the transition from a cooperative to a combative relationship between government and civil society was inevitable. Although there was cooperation among civic and state actors in some areas, we have seen a multitude of court challenges on the grounds of individual and group rights and administrative-justice issues.

According to the University of Cape Town (UCT) Refugee Case Law Reader, 96 cases were brought against the DHA from 1996 to 2013 with some cases featuring in the three upper courts (UCT, 2013). This number could come down to almost 75 cases in the High Court. As a result, the legal expenditure of the DHA mushroomed to R46.3 million in the 2011/12 financial year, double the previous year's expenditure. To put this into perspective:

Of the R1.34 billion in pending legal claims against it [DHA] (as of March 2013), claims against Immigration Affairs amounted to R503.3 million, which is 37.5 per cent of the total. The majority of the claims arose from "unlawful" arrests and detention of illegal foreigners as well as damages (Mthembu-Salter et al., 2014).

With the increase in litigation, the defiance of the DHA has increased. There is no goodwill on the part of the DHA to abide by the decisions of the courts, as was seen in the RRO closure cases. Therefore, litigation as an advocacy and protection tool has to be questioned.

Effectiveness of litigation

There is no doubt that litigation and other advocacy and protection tools have served NGOs well, as judgments in 90% of the cases mentioned above were in favor of NGOs and those they represented. As mentioned above, civil society gets frustrated trying to effect change either through consultation or other forms of advocacy. Society therefore turns to public-interest lawyers to hold government accountable. However, since rights are contested in most cases and are situated in a complex set of social and political environments, they need to be realized in cooperation with all stakeholders. It is clear from the interviews conducted with the three participating NGOs that they do not relish the partly adversarial relationship with the DHA. However, they feel that, in some cases, it is effective, as indicated in the quote above. The head of advocacy of Scalabrini Centre, elaborates their experience of litigation and its results:

You know, in our refugee office closure case, the Supreme Court of Appeal found it unlawful, based on consultation. So, they didn't consult with us people who are directly affected. Home Affairs said, "Well, we can't consult with asylum seekers because they are not in the country," and the Supreme Court said, "Well, obviously the NGOs and you consulted with them on certain things before anyway." So, it is an odd reason ... We tried to bring everybody in. SCMS or Wits University was there. UCT, ourselves [SC], LRC, and a multitude of other smaller organizations and everybody who was there was against the closure of the office . in the judgment you can easily see the DHA's approach to kind of duck and weave through the whole consultation process. These closure cases are based a lot on technical grounds.

The above quote is an indication of the difficult relationship that NGOs have with the DHA. As a result, NGOs need to assess if litigation, in the long run, is productive. In light of weak public support and lack of political will, litigation is rather counterproductive. This particular issue predates the adversarial nature of the relationship between the DHA and civil society. Amit (2011: 17) argues:

Many of the legislative and constitutional protections for asylum seekers and refugees have not been implemented because they are embedded in an environment of weak political and public support, combined with bureaucratic mismanagement and inefficiency.

This mindset of many South Africans and their representatives in government means that international and national migrant rights, obligations, and the values associated with them, are not even on the list of priorities. NGOs operate in an environment that, even if it is not hateful, is characterized by a sense of disinterest or frustration on the part of government and the wider public. Though the courts have proven their independence and mettle, they cannot effectively force government to comply with its constitutional mandate. NGOs therefore need to seek socio-political networks that support their advocacy and protection agenda (Abanyam and Mnorom, 2020; Abiddin et al., 2022). This is problematic, as the rights of asylum seekers increasingly come under attack (Masuku, 2020; Mukumbang et al., 2020).

Effectiveness of facilitating access to social services and humanitarian assistance

The NGOs, the RSS and the SC provide numerous social services: the RSS provides counseling, language lessons, and other potential income-generating skills training. It provides limited humanitarian assistance in cases of people who could not afford to pay rent or their children's school fees for a few months. The SC engages in similar activities but reaches more people and has a wider application. The SC cooperates with the Department of Education (DoE) and the Department of Health (DoH) to find employment for refugee teachers and nurses, respectively. However, the LHR offers limited social welfare assistance.

As previously discussed, NGOs addressed this problem by approaching these departments, or in extreme cases, by litigating in terms of access to services. NGOs have made significant gains but with one exception: they have been unable to make significant progress with regard to asylum seekers, and sometimes refugees, being unable to open bank accounts at most major banks (International Development Association, 2021). LHR has attempted to address this issue through litigation, with limited success.

In the sphere of humanitarian assistance, faith-based organizations and churches have shouldered these responsibilities, with only limited help from the government in times of crisis. The Central Methodist Church in Johannesburg opened its doors to Zimbabweans and other asylum seekers and refugees during the 2008 and subsequent violent xenophobic attacks (Andrews, 2009; Bompani, 2013; Joseph, 2015; Makunike, 2021). The church was a place of refuge and humanitarian assistance (Pausigere, 2013). The UNHCR (2014) underlines this role in its 2014 report. Even though the SC and the RSS have faith-based origins, they have not contributed much. The NGOs' personnel repeatedly stress that they are resource constrained as far as being able to provide humanitarian relief is concerned (UNHCR, 2014).

As discussed above, the effectiveness of the three participating NGOs differs when measured across different criteria. For instance, advocacy was much more successful in the past. Changes in effectiveness reflect the changing role of these NGOs. Despite playing a role in drafting refugee policy in the 1990s and 2000s, NGOs have become confrontational, since they have lost their voice in influencing policy. NGOs have been effective in monitoring implementation and access to documentation. However, as a result of increasingly restrictive government policy, they are now not as effective in this regard. NGOs have been largely successful in facilitating access to social services, as discussed above. In summary, their effectiveness is declining overall, and their role is changing. This is partly a result of the context they are operating in.

This study reiterates that the South African Refugees Act and the Constitution are not based on a normative belief in the fundamental human rights of the wider society. Race and ethnicity-based politics, together with political mobilization, are clear indications of this. Therefore, rights are based on membership of a national group. Within the national group, there is further apportioning of rights based on race and ethnicity. For instance, Black South Africans claim more rights based on historical injustice. Affirmative action is an example of this. This is not to say it is wrong, but it reflects the national psyche. Civil society does not have enough traction to effectively advocate for and protect the rights of asylum seekers and refugees because there is no widespread public support. As a result, the government, taking its cue from the sentiments of the wider public, has increasingly tightened the asylum system. This reflects a wider international trend regarding asylum seekers and refugees. South Africa is hardly an exception in this regard.

The analysis of both data sources and the literature indicates that access to RROs has been severely curtailed by the DHA's closure of three RROs. In many court submissions, the DHA claimed that asylum seekers do not have rights. This is contrary to the word and the spirit of the Refugees Act. In a court case that challenged the DHA's argument of the absence of rights for asylum seekers, Judge Dennis Davis expressed his concern when a state advocate said: "These people have no rights," and the judge said the closure of RROs violated the rights of a particularly vulnerable group of people.2

Furthermore, the socio-economic conditions that gave rise to the huge wealth gap in South Africa make it difficult for asylum seekers and refugees to claim socioeconomic rights. As data sources indicate, asylum seekers and refugees encounter xenophobic attitudes when they live and work closer to where there is competition for resources (Maharaj, 2009; Desai, 2010; White and Rispel, 2021). Their spaza shops were targeted during xenophobic attacks and service delivery protests, partly as a result of migrant workers being perceived as having taken over the spaza shop trade in informal settlements and in peri-urban areas where the poor live (IOM, 2013; Monson, 2015). The perception of the local poor that migrants are doing better than the locals translates into a loss of public support for asylum seekers and migrants.

Besides the many stereotypes, there are, however, criticisms of the asylum system that should be taken seriously. There is a belief that most asylum seekers are economic migrants (Crawley and Skleparis, 2017; Castelli, 2018; d'Albis et al., 2018; Maxmen, 2018). In addition, there are fraudulent asylum applications like the cases of the Consortium for Refugees and Migrants in South Africa (CoRMSA) v the President of the Republic;3 of (known criminal) Radovan Krejcir; and of Lukombo v Minister of Home Affairs and Others.4 However, it is the implementation of the Refugees Act and related immigration policies of the country that is responsible for creating the gaps that allow for the system to be abused. Both data sources confirm that corruption has severely affected the effectiveness of the institution of the DHA and compromises the rights of asylum seekers and refugees.

CONCLUSION

All in all, civil societies and NGOs play a significant role in advocating for and protecting the rights of refugees and asylum seekers. In other countries - in the absence of a local refugee policy - the UNHCR steps in to advocate for and protect refugees and asylum seekers. In fact, most African countries do not consider this their responsibility, despite ratifying the 1951 Refugee Convention. They leave it to the UNHCR to administer the asylum system in their countries.

In South Africa, there is a very liberal refugee policy and legislation. Therefore, the UNHCR is effectively on the periphery and has only diplomatic status. Despite the NGOs advocating for and protecting refugees and asylum seekers, they cannot fill the vacuum that is left by shortfalls in the implementation of the Refugees Act. That is the primary responsibility of the government. Thus, the limited capacity of NGOs should be recognized.

Despite their limited capacity, either through cooperation, consultation, or litigation, NGOs have made important gains. Some of their achievements are: the liberal elements within the Refugees Act; the right of asylum seekers to work and study; access to social grants; access to health; access to education and banking; and access to documentation. These achievements were made despite the government's continuing unwillingness to improve access to documentation, xenophobia, corruption, an inefficient public service, and a lack of political will. These challenges persist. The tactics and strategies employed by NGOs have been fruitful to some existent. However, the continued use of litigation as a tool is proving to be problematic.

In addition, there seems to be a disconnection between what refugees and asylum seekers perceive and the actual work that NGOs do. NGOs lack visibility on the ground and some refugee- and asylum-seeker communities do not know about them. What refugees know about the NGOs is acquired through their networks. It is unfair to expect NGOs to advertise their services, as this adds to their operating costs. However, they can work with migrant community-based organizations to better inform communities of their work.

REFERENCES

Abanyam, N.L. and Mnorom, K. 2020. Non-governmental organizations and sustainable development in developing countries. Zamfara Journal of Politics and Development, 1(1): 1-17. Available at: https://zjpd.com.ng/index.php/zjpd/article/view/3. Accessed on 26 July 2022. [ Links ]

Abiddin, N.Z., Ibrahim, I. and Abdul Aziz, S.A. 2022. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and their part towards sustainable community development. Sustainability, 14(8), p.4386. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084386. [ Links ]

Amisi, B., Bond, P., Cele, N. and Ngwane, T. 2011. Xenophobia and civil society: Durban's structured social divisions. Politikon, 38(1): 59-83. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589346.2011.548671. [ Links ]

Amit, R. 2011. Winning isn't everything: Courts, context, and the barriers to effecting change through public interest litigation. South African Journal on Human Rights, 27(1): 8-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/19962126.2011.11865003. [ Links ]

Andrews, A. 2009. No refuge, access denied: Medical and humanitarian needs of Zimbabweans in South Africa. Doctors Without Borders - USA. Available at: https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/latest/no-refuge-access-denied-medical-and-humanitarian-needs-zimbabweans-south-africa Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Arendt, H. [1951] 1973. The origins of totalitarianism. New York: The World Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Beaubien, J. 2019. The country with the world's worst inequality is ... NPR Choice page. Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2018/04/02/598864666/the-country-with-the-worlds-worst-inequality-is. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Bjarnesen, J. and Turner, S. (eds.), 2020. Invisibility in African displacements: From structural marginalization to strategies of avoidance. London: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Bompani, B. 2013. "It is not a shelter, it is a church!" Religious organisations, the public sphere and xenophobia in South Africa. In: Hopkins, P., Kong, L., Olson, E. (eds.), Religion and place. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4685-58. [ Links ]

Boswell, C. 2017. The ethics of refugee policy. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. 2020. Country reports on human rights practices for 2020 - South Africa. United States Department of State. Available at: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/SOUTH-AFRICA-2020-HUMAN-RIGHTS-REPORT.pdf. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Cameron, J. 2000. Development economics, the new institutional economics and NGOs. Third World Quarterly, 21(4), 627-635. https://doi.org/10.1080/713701070. [ Links ]

Castelli, F. 2018. Drivers of migration: Why do people move? Journal of Travel Medicine, 25(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/tay040. [ Links ]

Chutel, L. and Kopf, D. 2018. South Africa's inequality is getting worse as it struggles to create jobs after apartheid. Quartz Africa. Available at: https://qz.com/africa/1273676/south-africas-inequality-is-getting-worse-as-it-struggle-to-create-jobs-after-apartheid/. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Crawley, H. and Skleparis, D. 2017. Refugees, migrants, neither, both: Categorical fetishism and the politics of bounding in Europe's "migration crisis". Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(1): 48-64. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1348224. [ Links ]

Crush, J. 2001. The dark side of democracy: Migration, xenophobia and human rights in South Africa. International Migration, 38(6): 103-133. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00145. [ Links ]

Crush, J. 2008. South Africa: Policy in the face of xenophobia. Migration Policy Institute (MPI). Available at: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/south-africa-policy-face-xenophobia. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

d'Albis, H., Boubtane, E. and Coulibaly, D. 2018. Macroeconomic evidence suggests that asylum seekers are not a "burden" for Western European countries. Science Advances, 4(6): p.eaaq0883. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaq0883. [ Links ]

Dahir, A.L. 2019. What is behind South Africa's xenophobic attacks on foreigners? Quartz Africa. Available at: https://qz.com/africa/1708814/what-is-behind-south-africas-xenophobic-attacks-on-foreigners/. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Desai, A. 2010. Xenophobia and the place of the refugee in the rainbow nation of human rights. African Sociological Review/Revue Africaine de Sociologie, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.4314/asr.v12i2.49834. [ Links ]

Everatt, D. 2011. Xenophobia, state and society in South Africa, 2008-2010. Politikon, 38(1): 7-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589346.2011.548662 [ Links ]

Fajth, V., Bilgili, Ö., Loschmann, C., and Siegel, M. 2019. How do refugees affect social life in host communities? The case of Congolese refugees in Rwanda. Comparative Migration Studies, 7(1): 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0139-1 [ Links ]

FreedomHouse 2022. South Africa: Freedom in the world - 2022 Country Report. Freedom House. Available at: https://freedomhouse.org/country/south-africa/freedom-world/2022. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Frye, I., Farred, G. and Nojekwa, L. 2011. Inequality in South Africa. In: Jauch, H. and Muchena, D. (eds.), Tearing us apart: Inequalities in southern Africa. Johannesburg, South Africa: Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA). [ Links ]

Gumede, W. 2018. 25 years later, South African civil society still battling government in people's interests. Civicus. Available at: https://www.civicus.org/index.php/media-resources/news/civicus-at-25/3531-25-years-later-south-african-civil-society-still-battling-government-in-people-s-interests. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Handmaker, J. 2009. Advocating for accountability: Civic-state interactions to protect refugees in South Africa. Antwerp: Oxford Press. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/1765/21497. Accessed on 30 June 2022. [ Links ]

Human Rights Watch (HRW). 2020. South Africa: Widespread xenophobic violence. Human Rights Watch. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/09/17/south-africa-widespread-xenophobic-violence. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

International Development Association (IDA). 2021. IDA19 mid-term refugee policy review. Development Finance, Corporate IDA and IBRD (DFCII), World Bank Group. Available at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/826851636575674627/pdf/IDA19-Mid-Term-Refugee-Policy-Review.pdf. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2013. The well-being of economic migrants in South Africa: Health, gender and development. Working paper for the World Migration Report 2013. Available at: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/migrated_files/What-We-Do/wmr2013/en/Working-Paper_SouthAfrica.pdf. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Jansen, J.D. 2002. Political symbolism as policy craft: Explaining non-reform in South African education after apartheid. Journal of Education Policy, 17(2): 199-215. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930110116534. [ Links ]

Joseph, N. 2015. Sheltering against resentment: End of the line for the Johannesburg church that provides sanctuary for those fleeing xenophobia. Index on Censorship, 44(1): 60-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306422015571517. [ Links ]

Kavuro, C. 2016. Refugees and asylum seekers: Barriers to accessing South Africa's labour market. Law, Democracy and Development, 19(1): 232. https://doi.org/10.4314/ldd.v19i1.12. [ Links ]

Lewis, D. 2006. The management of non-governmental development organizations. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Maharaj, B. 2009. Migrants and urban rights: Politics of xenophobia in South African cities. L'Espace Politique. Revue en ligne degéographie politique et degéopolitique, (8). Available at: https://journals.openedition.org/espacepolitique/1402. Accessed on 1 November 2023. [ Links ]

Majola, N. 2022. Immigrants question continued closure of reception offices while all other Home Affairs facilities are open for service. Daily Maverick. Available at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-02-15-immigrants-question-continued-closure-of-reception-offices-while-all-other-home-affairs-facilities-are-open-for-service/. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Makunike, A.T. 2021. Church takes on xenophobia in South Africa. United Methodist News Service. Available at: https://www.umnews.org/en/news/church-takes-on-xenophobia-in-south-africa. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Mantzaris, E. and Ngcamu, B.S. 2021. Dissecting shelter for the displaced immigrants' operations and challenges in the 2015 xenophobic violence in Durban. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1875579. [ Links ]

Masuku, S. 2020. How South Africa is denying refugees their rights: What needs to change. The Conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/how-south-africa-is-denying-refugees-their-rights-what-needs-to-change-135692. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Masuku, S. and Rama, S. 2020. A case study of government and civil societies' collaboration and challenges in securing the rights of Congolese refugees living in Pietermaritzburg, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. South African Journal of Science, 116(3-4): 1-6. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2020/6210. [ Links ]

Maxmen, A. 2018. Migrants and refugees are good for economies. Nature. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05507-0. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Milner, J. and Klassen, A. 2020. Civil society and the politics of the global refugee regime. Reference paper for the 70th anniversary of the 1951 Refugee Convention. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/people-forced-to-flee-book/wp-content/uploads/sites/137/2021/10/James-Milner-and-Amanda-Klassen-Civil-Society-and-the-Politics-of-the-Global-Refugee-Regime.pdf. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Minister of Home Affairs & Others v Scalabrini. Centre, Cape Town & Others [2013] ZASCA 134 (27. September 2013)

Misago, J., Freemantle, I., Landau, L. and Oatway, J. 2015. Protection from xenophobia: An evaluation of UNHCR's Regional Office for Southern Africa's xenophobia-related programmes. African Centre for Migration and Society, University of the Witwatersrand. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/55cb153f9.pdf. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Monson, T. 2015. Citizenship, "xenophobia" and collective mobilization in a South African settlement: The politics of exclusion at the threshold of the state. Unpublished PhD thesis, London School of Economics and Political Science. Available at: https://etheses.lse.ac.uk/3404/1/Monsoncitizenshipxenophobia.pdf. Accessed on 26 July 2022. [ Links ]

Moyo, K. and Botha, C. 2022. Refugee policy as infrastructure: The gulf between policy intent and implementation for refugees and asylum seekers in South Africa. In: Rugunanan, P. and Xulu-Gama, N. (eds.), Migration in Southern Africa. IMISCOE Research Series. Cham: Springer: pp. 77-89. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92114-96. [ Links ]

Moyo, K., Sebba, K. R., and Zanker, F. 2021. Who is watching? Refugee protection during a pandemic-responses from Uganda and South Africa. Comparative Migration Studies, 9(1): 1-19. Available at: https://comparativemigrationstudies.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40878-021-00243-3. Accessed on 1 November 2023. [ Links ]

Mthembu-Salter, G., Amit, R., Gould, C. and Landau, L. 2014. Counting the cost of securitising South Africa's immigration regime. Working Paper 20. Institute for Security Studies and the African Centre for Migration and Society, University of the Witwatersrand. Available at: http://www.migratingoutofpoverty.org/files/file.php?name=wp20-mthembu-salter-et-al-2014-counting-the-cost.pdf&site=354. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Mukumbang, F.C., Ambe, A.N. and Adebiyi, B.O. 2020. Unspoken inequality: How COVID-19 has exacerbated existing vulnerabilities of asylum seekers, refugees, and undocumented migrants in South Africa. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01259-4. [ Links ]

Myeni, T. 2022. What is Operation Dudula, South Africa's anti-migration vigilante? www.aljazeera.com. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2022/4/8/what-is-operation-dudula-s-africas-anti-immigration-vigilante. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Ngwenya, N., Gumede, D., Shahmanesh, M., McGrath, N., Grant, A. and Seeley, J. 2018. Community perceptions of the socio-economic structural context influencing HIV and TB risk, prevention and treatment in a high-prevalence area in the era of antiretroviral therapy. African Journal of AIDS Research, 17(1): 72-81. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2017.1415214. [ Links ]

Nicholson, F. and Kumin, J. 2017. A guide to international refugee protection and building state asylum systems: Handbook for Parliamentarians No 27. Inter-Parliamentary Union and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/3d4aba564.pdf.

Nwakunor, G.A. and Nwanne, C. 2018. Why South Africans attack Nigerians. The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News. Available at: https://guardian.ng/features/why-south-africans-attack-nigerians/ Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Levy, B., Hirsch, A., Naidoo, V. and Nxele, M. 2021.. South Africa: When strong institutions and massive inequalities collide. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/03/18/south-africa-when-strong-institutions-and-massive-inequalities-collide-pub-84063. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Palmary, I. 2002. Refugees, safety and xenophobia in South African cities: The role of local government. Johannesburg: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. Available at: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/104945/refugeessafteyand.pdf Accessed 02 November 2023.

Pausigere, P. 2013. Education and training initiatives at the Central Methodist Church Refugee House in Johannesburg. Perspectives in Education, 31(2): 4253. Available at: https://journals.ufs.ac.za/index.php/pie/article/view/1804. [ Links ]

Polzer Ngwato, T. 2010. Population movements in and to South Africa. Migration Fact Sheet # 1, profile - South Africa. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/296416/Migration_Fact_Sheet_1_Population_Movements_in_and_to_South_Africa. Accessed on 05 March 2015. Accessed on 05 March 2015.

Polzer Ngwato, T. 2013. Policy shifts in the South African asylum system: Evidence and implications. African Centre for Migration Studies and Lawyers for Human Rights Report.

Rugunanan, P. and Xulu-Gama, N. (eds.) 2022. Migration in Southern Africa. IMISCOE Regional Readers, IMISCOE Research Series.

Scalabrini Centre Cape Town v Minister of Home Affairs and Others (11681/2012) [2012] ZAWCHC 147; (25 July 2012).

Schneider, H. 2002. On the fault-line: The politics of AIDS policy in contemporary South Africa. African Studies, 61(1): 145-167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020180220140118. [ Links ]

Seton-Watson, H. 1977. Nations and states: An enquiry into the origins of nations and the politics of nationalism. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Smith, A.D. 1991. National identity. North Virginia: University of Nevada Press. [ Links ]

Solomon, H. and Haigh, L. 2009. Xenophobia in South Africa: Origins, trajectory and recommendations. Africa Review, 1(2): 111-131. https://doi.org/10.1080/09744053.2009.10597284. [ Links ]

United Nations (UN). 2011. Are human rights universal? United Nations. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/are-human-rights-universal. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2018. Annual Report. Available at: https://unctad.org/annualreport/2018/Pages/index.html. Accessed on 31 October 2023.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2014. On faith-based organizations, local faith communities and faith leaders. Switzerland: UNHCR. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/539ef28b9.pdf. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

University of Cape Town. (2013). Refugee case law reader. UCT. Available at: https://law.uct.ac.za/refugee-rights/clinics/case-law-reader.

Van Mierop, E.S. 2004. UNHCR and NGOs: Competitors or companions in refugee protection? Available at: http://www.migrationinformation.org/Feature/display.cfm?ID=200. Accessed on 10 May 2023.

Viljoen, F. 2009. International human rights law: A short history. United Nations. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/international-human-rights-law-short-history. Accessed on 26 July 2022.

White, J.A. and Rispel, L.C. 2021. Policy exclusion or confusion? Perspectives on universal health coverage for migrants and refugees in South Africa. Health Policy and Planning, 36(8): 1292-1306. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czab038. [ Links ]

World Health Organization (WHO). 2022. Refugee and migrant health. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/refugee-and-migrant-health Accessed on 26 July 2022.

Zainal, Z. 2007. Case study as a research method. Jurnal Kemanusiaan, 5(1). Available at https://jurnalkemanusiaan.utm.my/index.php/kemanusiaan/article/view/165 Accessed on 25 July 2022. [ Links ]

Received 22 September 2022

Accepted 04 August 2023

Published December 2023

1 For centuries, Jews were moneylenders as well as advisors later on, to kings and governments. The rise of the nation-state and the subsequent dependence on tax and credit from the nobility without political clout rendered most Jews powerless. In addition, their lack of strong nationality to any sovereignty contributed to their lack of political clout. Few Jewish families, like the Rothschilds, managed to acquire political power.

2 Scalabrini Centre Cape Town v Minister of Home Affairs and Others (11681/2012) [2012] ZAWCHC 147; (25 July 2012).

3 CoRMSA v the President of the Republic of South Africa and Others, Case No. 30123/11. CoRMSA argued that the Rwandan general, Faustin Kayumba Nyamwasa does not deserve refugee status. However, CoRMSA lost this case; subsequent attempts to overturn the decision to give him a refugee status by the DHA were unsuccessful. Mr. Nyamwasa is wanted for war crimes in Spain and France. He also survived an assassination attempt, allegedly by the Rwandan government while he was in South Africa.

4 Lukombo v Minister of Home Affairs and Others (2013/13552) [2013] ZAGPJHC 142 (13 June 2013). Mr. Lukombo applied for asylum three times, under different names.